pulmonary renal syndrome, refers to diffuse alveolar hemorrhage in combination with rap-idly progressive glomerulonephritis and is an emergent condition. If not recognized and managed properly, it can cause fatal pulmo-nary hemorrhage [3]. Patients usually pres-ent with dyspnea and cough, together with de-creased oxygen saturation levels. The main clue for pulmonary hemorrhage is hemopty-sis, but it may not be present in all cases.

Chest radiography and CT reveal a dif-fuse alveolar filling process, a term used for bleeding directly into the airspaces be-cause of pulmonary capillaritis. Appropri-ate interpretation of the imaging findings is paramount. In general, the typical feature on chest radiographs (during an acute dif-fuse alveolar hemorrhage) is a difdif-fuse infil-trative opacification pattern, whereby peri-hilar regions of the middle and lower zones are predominantly involved, with some api-cal and costophrenic angle sparing [4–6]. However, either positive or negative chest x-rays do not exclude pulmonary hemorrhage. CT can reveal mostly lobular or lobar areas of ground-glass opacities, which are gener-ated by subtotal alveolar filling with blood (Fig. 1). When alveolar infiltrative opacifica-tion is accompanied with interlobular septal thickening and reticular pattern, it is called crazy paving. This is a characteristic but not pathognomonic term for alveolar hemor-rhage, but it can also be seen in acute respi-ratory distress syndrome or acute interstitial pneumonia [5]. The rheumatologic

differen-Imaging Findings of Pediatric

Rheumatologic Emergencies

O. Melih Topcuoglu

1H. Nursun Ozcan

1Erhan Akpinar

1E. Dilara Topcuoglu

2Berna Oguz

1Mithat Haliloglu

1Topcuoglu OM, Ozcan HN, Akpinar E, Topcuoglu ED, Oguz B, Haliloglu M

1Department of Radiology, Division of Pediatric Radiology, Hacettepe University School of Medicine, Sihhiye 06100, Ankara, Turkey. Address correspondence to M. Haliloglu (mithath@hacettepe.edu.tr).

2Department of Radiology, Ufuk University School of Medicine, Ankara, Turkey.

AJR 2015; 204:428–439 0361–803X/15/2042–428 © American Roentgen Ray Society

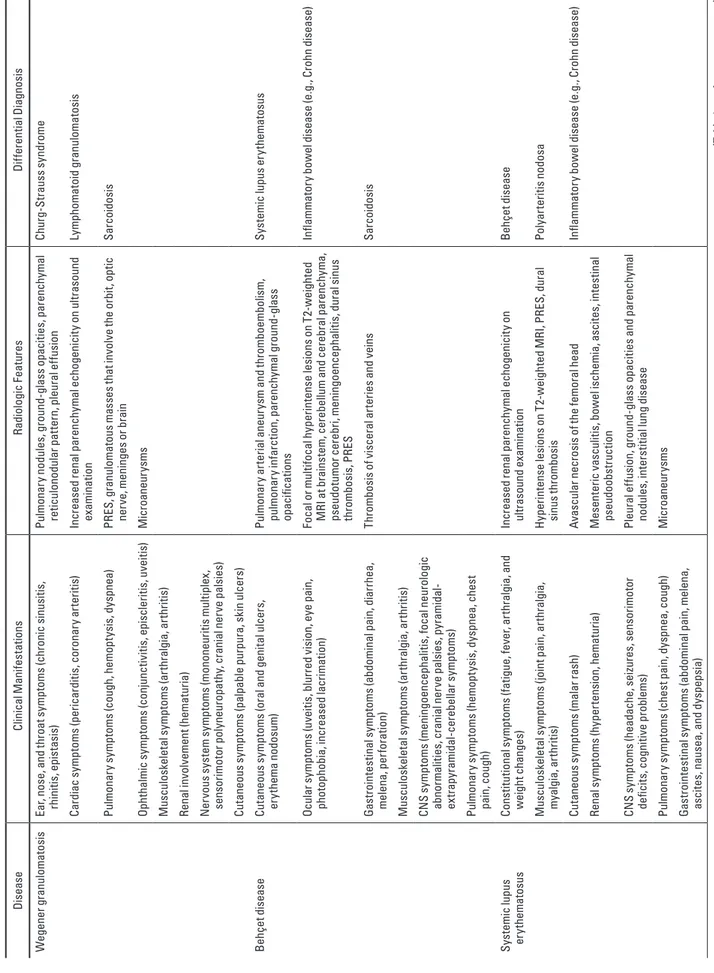

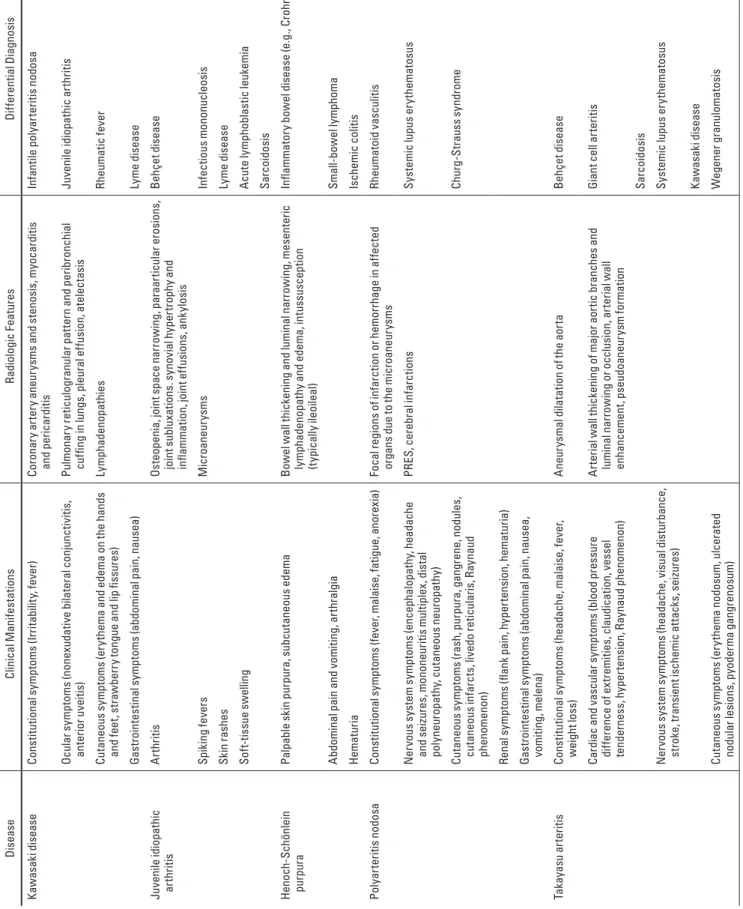

I

n the developed world, the me-dian annual referral rate to a pediatric rheumatology center is approximately 26 cases per 100,000 children at risk. The most frequent diagnoses are chronic arthritides (23.3%), connective tissue diseases (6.5%), and vas-culitides (6.1%) [2]. All types of radiologic imaging tools can be used in the emergency department, but the most commonly used ones are chest radiography for chest pain and dyspnea; chest CT and CT angiography (CTA) for diffuse lung diseases and the pul-monary and coronary vasculature; echo-cardiography for pericardial tamponade; ab-dominal sonography and CT for abab-dominal pain; radiographs, ultrasound, and MRI for acute arthritis; and cranial CT and MRI for CNS symptoms (e.g., seizure, focal neuro-logic deficits, and loss of consciousness).Here we discuss the radiologic findings of various pediatric rheumatologic emergen-cies categorized according to various clini-cal scenarios. These pediatric rheumatologic emergencies are summarized along with their general clinical manifestations, radiologic features, and differential diagnosis in Table 1. Children With Respiratory

Complications

Pulmonary renal syndrome, Wegener gran-ulomatosis, and Behçet disease (BD) are the main diseases associated with respiratory complications. The concomitance of respi-ratory distress and renal failure, also called

Keywords: children, emergency, radiology,

rheumatologic disease DOI:10.2214/AJR.14.13092

Received May 1, 2014; accepted after revision July 21, 2014.

OBJECTIVE. Pediatric rheumatologic diseases can present with a wide spectrum of clin-ical features, affecting any organ in the body and causing significant morbidity and mortality. The aim of this review is to emphasize the diagnostic imaging findings of pediatric rheuma-tologic emergencies and to discuss their pertinent complications.

CONCLUSION. Because of their multiorgan and multisystem involvement, pediatric rheumatologic diseases comprise a wide spectrum of differential diagnosis. Although the di-agnosis may generally not be time critical, for a few conditions, prompt recognition is crucial to preserving organ function or the patient’s life [1].

Topcuoglu et al.

Imaging of Pediatric Rheumatologic Emergencies Pediatric Imaging

Review

T A B LE 1 : G en er al C lin ic al M an ife st at io ns , R ad io lo gi c F ea tu re s, a nd D iff er en ti al D ia gn os es o f P ed ia tr ic R he um at ol og ic E m er ge nc ie s Dise ase Cl in ic al Ma ni fe st at ions Ra di ol ogi c F ea tur es Di ffer en tia l D ia gn os is W eg ener g ra nu lo ma to si s Ea r, n os e, a nd t hr oa t s ym pt om s ( ch ro ni c s in us iti s, rhini tis , e pis ta sis ) Pu lm on ar y n od ul es , g ro un d-gl as s opa ci tie s, pa ren ch yma l re tic ul ono dul ar p at te rn , p le ur al e ffu sion Chur g-St ra us s s yn dr om e Ca rd iac s ym pt om s ( pe ric ar di tis , c or on ar y a rt er iti s) Inc rea se d r en al p ar enc hy m al e ch og en ic ity o n u ltr as ou nd ex am in at ion Ly m ph om at oi d g ra nu lom at os is Pu lm on ar y s ym pt om s ( co ug h, h em op ty si s, d ys pn ea ) PR ES , g ra nu lo m at ou s m as se s t ha t i nv ol ve t he o rb it, o pt ic ne rv e, m enin ge s o r b ra in Sa rc oi do sis Op ht ha lm ic s ym pt om s ( co nj un ct iv itis , e pis cl er itis , u ve iti s) M ic roa ne ur ys m s M us cu lo sk ele ta l s ymp to m s ( ar th ra lg ia , a rt hr iti s) Ren al in vo lv em en t (he ma tu ria ) N er vous s ys tem s ymp to m s ( m on on eu rit is m ul tip lex , sen so rim ot or p ol yne ur opa th y, c ra ni al ner ve pa ls ie s) Cu ta neous s ymp to m s ( pa lp ab le pu rpu ra , s ki n u lc er s) Be hç et d ise ase Cu ta ne ou s s ym pt om s ( or al a nd g en ita l u lc er s, er yt he ma n odo su m ) Pu lm on ar y a rt er ia l a ne ur ys m a nd t hr om bo em bo lis m , pu lm on ar y i nf ar ct io n, pa ren ch yma l g ro un d-gl as s op ac ific at ions Sy st em ic lu pus e ry th em at os us Oc ul ar s ym pt om s ( uv ei tis , b lu rr ed v is io n, e ye p ai n, pho to pho bi a, in cr ea se d l ac rim at ion ) Fo ca l o r mul tif oc al h yp er in te ns e l es ions on T 2-w ei gh te d M RI a t b ra in st em , c er eb el lu m a nd c er eb ra l p ar en ch ym a, pse ud ot um or c er eb ri, m enin go en ce ph ali tis , d ur al s in us th ro m bo sis , P RE S In fla m m at or y bo w el d ise ase (e .g ., C ro hn d ise ase ) Ga st roin te st in al s ym pt om s ( ab do m in al p ain , d ia rr he a, mel en a, p er fo ra tion ) Th ro m bo si s o f v is ce ra l a rt er ie s a nd v ei ns Sa rc oi do sis M us cu lo sk ele ta l s ymp to m s ( ar th ra lg ia , a rt hr iti s) CN S s ym pt oms (m en in go en ce ph al iti s, fo ca l n eu ro lo gi c ab no rma lit ie s, c ra ni al ner ve pa ls ie s, p yr am id al - ex tr ap yr am id al -c er ebe lla r s ymp to m s) Pu lmo na ry s ym pt oms (h emo pt ys is , d ys pn ea , c hes t pai n, co ug h) Sy st em ic lu pus er yt he ma to su s Co ns tit ut io na l s ym pt om s ( fa tig ue , f ev er , a rt hr al gi a, a nd w eigh t c ha ng es ) Inc rea se d r en al p ar enc hy m al e ch og en ic ity o n ul tr as oun d ex am in at io n Be hç et d ise ase M us cu lo sk el et al s ym pt oms (j oi nt p ai n, a rt hr al gi a, m ya lgi a, a rt hr iti s) H yp er in te ns e l es io ns o n T 2-w ei gh te d M RI , P RE S, d ur al sin us th ro m bo sis Po ly ar te rit is n od os a Cu ta neous s ymp to m s ( m al ar ra sh ) Av as cu la r n ec ro si s o f t he f em or al h ea d In fla m m at or y bo w el d ise ase (e .g ., C ro hn d ise ase ) Ren al s ym pt om s (h yp er ten si on , he ma tu ria ) M es en ter ic v asc ul iti s, b ow el isc he m ia , a sc ite s, in te st in al ps eu do ob st ru ct io n CN S s ym pt oms (h ea da ch e, s ei zu res , s en so rimo to r de fic its , c og ni tive p ro blem s) Pl eu ra l e ffu si on , g ro un d-gl as s opa ci tie s a nd pa ren ch yma l nod ul es , in te rs tit ia l l un g d ise ase Pu lm on ar y s ym pt om s ( ch es t p ai n, d ys pn ea , c ou gh ) M ic roa ne ur ys m s Ga st roin te st in al s ym pt om s ( ab do m in al p ain , m el en a, as ci te s, n au se a, a nd d ys pe ps ia ) (T ab le 1 c on tinue s on ne xt p ag e)

T A B LE 1 : G en er al C lin ic al M an ife st at io ns , R ad io lo gi c F ea tu re s, a nd D iff er en ti al D ia gn os es o f P ed ia tr ic R he um at ol og ic E m er ge nc ie s ( co nt in ue d) Dise ase Cl in ic al Ma ni fe st at ions Ra di ol ogi c F ea tur es Di ffer en tia l D ia gn os is Ka w as ak i d is eas e Cons tit ut ion al s ym pt om s ( Irr ita bi lit y, f ev er ) Co ro na ry a rt er y a ne ur ys m s a nd s te no si s, m yo ca rd iti s and p er ic ar di tis In fa nt ile po ly ar te rit is n od os a Oc ul ar s ymp to m s ( no nex ud at ive b ila te ra l c on jun ct iv iti s, an te rior u ve iti s) Pul m on ar y r et ic ul og ra nul ar p at te rn a nd p er ibr on ch ia l cu ffi ng i n l un gs , p le ur al e ffu si on , a te le ct as is Ju ven ile id iopa th ic a rt hr iti s Cu ta ne ou s s ym pt om s (e ry th em a a nd e de m a o n t he h an ds an d f ee t, s tr aw be rr y t on gu e a nd l ip fi ss ur es ) Ly m ph ad en opa th ie s Rhe uma tic fe ver Ga st roin te st in al s ym pt om s ( ab do m in al p ain , n au se a) Ly m e d ise ase Ju ven ile id iopa th ic ar th rit is A rt hr iti s Os te op en ia , j oi nt s pac e n ar ro w in g, p ar aa rt ic ul ar e ro si on s, jo in t s ub lu xa tions . s yno vi al h yp er tr op hy a nd in fla m m at ion , jo in t e ffu sions , a nk yl os is Be hç et d ise ase Spi kin g f ev er s M ic roa ne ur ys m s In fe ct ious m on on uc leo si s Sk in r as he s Ly m e d ise ase So ft-tis su e s w ellin g Ac ut e l ymp ho bl as tic le uk em ia Sa rc oi do sis He no ch -S chön le in pur pur a Pa lp ab le s ki n pu rpu ra , s ub cu ta neous ed em a Bo w el w all thi ck enin g a nd lum in al n ar ro w in g, m ese nt er ic ly m ph ad en opa th y a nd e de ma , i nt us su sc ep tio n (ty pic al ly il eo ileal ) In fla m m at or y bo w el d ise ase (e .g ., C ro hn d ise ase ) A bd om in al p ain a nd vo m itin g, a rt hr al gi a Sma ll-bo w el ly m ph oma He m at ur ia Isc he m ic c ol iti s Po ly ar te rit is n od os a Co ns tit ut io na l s ym pt om s ( fe ve r, m al ai se , f at ig ue , a no re xi a) Fo ca l r eg io ns o f i nf ar ct io n o r h em or rh ag e i n a ffe ct ed or ga ns d ue t o t he m ic ro an eu ry sm s Rhe uma to id v asc ul iti s N er vo us s ys te m s ym pt om s ( en ce ph al opa th y, he ad ac he an d s ei zu re s, m onon eu rit is mul tip le x, d is ta l po ly ne ur opa th y, c ut ane ou s ne ur opa th y) PR ES , c er ebr al in fa rc tions Sy st em ic lu pus e ry th em at os us Cu ta neous s ymp to m s ( ra sh , pu rpu ra , g an gr en e, n od ule s, cu ta neous in fa rc ts , l ived o r et ic ul ar is , R ay na ud ph eno me non ) Chur g-St ra us s s yn dr om e Ren al s ym pt om s ( fla nk pa in , h yp er ten si on , he ma tu ria ) Ga st roin te st in al s ym pt om s ( ab do m in al p ain , n au se a, vo m iti ng , mel en a) Tak ay as u a rt er iti s Co ns tit ut io na l s ym pt om s (he ad ac he , ma la is e, fe ver , w eigh t l os s) A ne ur ys m al d ila ta tio n o f t he a or ta Be hç et d ise ase Ca rd iac a nd v as cu la r s ym pt om s ( bl oo d p re ss ur e di ffe re nc e o f e xt re m iti es , c la ud ic at io n, v es se l ten der ne ss , h yp er ten si on , R ay na ud p hen om en on ) A rt er ia l w al l t hi ck en in g o f m aj or a or tic b ra nc he s a nd lu m in al n ar ro w in g o r o cc lu si on , a rt er ia l w al l en ha nc em en t, p se udoa ne ur ys m fo rma tio n Gi an t c el l a rt er iti s Sa rc oi do sis Ne rvo us s ys te m s ym pt om s ( he ad ac he, v is ua l d is tu rb an ce, st ro ke , t ra ns ie nt i sc he m ic a tt ac ks , s ei zu re s) Sy st em ic lu pus e ry th em at os us Ka w as ak i d is eas e Cu ta ne ou s s ym pt om s ( er yt he ma n odo su m , u lc er at ed no dul ar le sions , p yo de rm a g an gr eno su m ) W eg ener g ra nu lo ma to si s N ot e— PR ES = p os ter io r r ev er sib le en ce ph al opa th y s yn dr om e.

tial diagnosis of pulmonary renal syndrome in children includes antineutrophil cytoplas-mic antibody–associated vasculitis (cytoplas-micro- (micro-scopic polyangiitis or Wegener granuloma-tosis), Goodpasture syndrome, and systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) [7].

Wegener granulomatosis is a chronic sys-temic vasculitis. Upper and lower respiratory tract inflammation with renal disease is the classic triad of Wegener granulomatosis. The clinical picture includes hemoptysis, short-ness of breath, chronic cough, and subglot-tic stenosis. The diagnosis should be made by a supportive clinical history and laborato-ry findings, including anemia. In a child pre-senting with hemoptysis, if a nodular pattern is dominant over ground-glass opacities on CT, Wegener granulomatosis should be kept in mind. Cavitation, pleural effusion, and pneumothoraces may also occur.

BD is another rheumatologic disease lead-ing to severe pulmonary symptoms via affect-ing both the pulmonary arteries and veins. BD, a chronic relapsing vasculitis and multisystem inflammatory disease with unknown origin, was first reported by a Turkish dermatologist, Hulusi Behçet, in 1937 [8]. BD is most com-mon in Japan, Turkey, and other parts of the Middle East. The highest prevalence was re-ported from Turkey and is less than 10 cas-es per 100,000 children [8]. BD usually prcas-es- pres-ents after puberty, but because of clinical and radiologic awareness, the incidence of juve-nile onset is increasing gradually. The clinical findings of juvenile-onset BD are similar to those for adult-onset BD, and severe organ in-volvement has a variable frequency [9]. Vas-cular involvement is the key imaging finding of BD, and either deep or superficial throm-boses are seen in approximately 30% of the cases (most commonly in the pulmonary ar-teries) [10]. Thrombosis occurs because of the thickening of vessel walls and perivascu-lar soft tissues because of intense inflamma-tion (Fig. 2). Venous involvement, generally in the form of thrombosis and thrombophlebi-tis, is more common than arterial involvement [11]. Aneurysm formation, luminal dilatation, and occlusions are the arterial manifestations of BD, affecting most commonly the thoracic aorta and the pulmonary arteries. These large arterial involvements, along with the inferior or superior vena cava thrombosis, are the im-portant causes of mortality in children with BD [12]. In the emergency setting, evalua-tion of the patient should include not only the symptomatic sites but also the venous and ar-terial structures to uncover the extent of

in-volvement. In children with BD, saccular or fusiform pulmonary arterial aneurysms are common and typically bilateral and they af-fect the lower lobe or main pulmonary arter-ies. Subpleural parenchymal infiltrates and wedge-shaped or round ground-glass opaci-ties representing focal vasculitis and throm-bosis usually end up with infarction, hemor-rhage, and focal atelectasis [13].

Children With Fever and Hematologic Complications

The presence of fever and pancytopenia in a child usually suggests sepsis, myelodysplas-tic syndromes, and malignancy. However, less commonly, macrophage activation syndrome (MAS), viral or bacterial infections, and inva-sive aspergillosis should also be considered.

MAS, which is a life-threatening com-plication of rheumatologic diseases, may present with fever, pancytopenia, hepato-splenomegaly, lymphadenopathy, and liv-er dysfunction and frequently is associated with Epstein-Barr virus [14–16]. MAS is a kind of immunosuppressive condition lead-ing to opportunistic infections. It is closely related to hemophagocytic syndrome, which also shows macrophage activation and pro-liferation with leukocytopenia. Therefore, MAS triggered by rheumatologic diseases should be kept in mind in a child with fever and pancytopenia, and the lungs should first be evaluated for atypical infections. The most common diseases that may induce MAS are systemic juvenile idiopathic arthritis, juve-nile SLE, Kawasaki disease (KD), and oc-casionally Wegener granulomatosis. The dif-ferential diagnosis of MAS includes Reye syndrome, thrombotic thrombocytopenic purpura, and malignant histiocytic disorders.

Cytomegalovirus infection is one of the likely diagnoses when dealing with children with leukocytopenia. CT may show patchy or diffuse consolidation, ground-glass opac-ities, small centrilobular nodules, bronchi-al wbronchi-all thickening, a combination of these, and pleural effusion [17] (Fig. 3). However, not all CT findings are specific, and they can also be seen in bacterial infections. Ground-glass nodules and opacities, centrilobular nodules, and bronchial wall thickening may be found in both bacterial and viral infec-tions [18]. Coincidental occurrence of viral and bacterial infections should also be kept in mind because they are not rare in immu-nocompromised children. Invasive asper-gillosis usually affects immunosuppressed children and may display ground-glass

opac-ities, ill-defined nodules, and consolidation on chest CT [19]. Nodules are usually sur-rounded by ground-glass densities repsenting hemorrhage and necrosis and are re-ferred to as the halo sign [20]. The halo sign is not pathognomonic to invasive Aspergil-lus species infection and may be detected in other infections, malignant lesions, and We-gener granulomatosis [21]. Chest CT helps to confirm the diagnosis by showing mainly ground-glass opacities and, to a lesser extent, micronodules (nodules < 3 mm) representing nonspecific infectious pattern (Fig. 3). Children With Cardiovascular Complications

SLE, juvenile idiopathic arthritis, and KD are generally associated with cardiovascu-lar complications. Pericardial tamponade is triggered by rheumatologic disorders and has an incidence of 13–30% in children [22, 23]. Because of the impaired cardiac output, it is a rare but fatal complication of pediatric rheu-matologic diseases. Pericardial tamponade, which is caused by the accumulation of flu-id, pus, blood, gas, or neoplastic tissue within the pericardial cavity, is a compressive state on the myocardium. The most common rheu-matologic diseases causing pericarditis with hemorrhagic effusion are SLE and juvenile idiopathic arthritis [24, 25]. Clinical symp-toms in a child with pericardial tamponade are dyspnea, tachypnea, and chest pain. Chest radiograph usually shows mild to significant-ly increased cardiothoracic ratio, depending on the amount of effusion. Lungs are usually normal. At least 200 mL of pericardial fluid accumulation is necessary for a visible car-diac silhouette enlargement on chest radio-graphs [26]. Immediate echocardiography should be performed in all cases of suspected pericardial tamponade. However, in equivo-cal cases or when echocardiography is not available, CT or MRI can be contributory by distinguishing the content of the effusion and showing the related abnormalities in the mediastinum, lungs, and nearby structures. CT reveals pericardial effusion, thickening, and enhancement; it also gives information about the nature of the collection based on the attenuation measurements (Fig. 4). In-creased attenuation values compared with water suggest hemorrhage, purulent materi-al, exudative fluids of inflammatory disease, and malignancies [27]. Pericardial thicking (particularly on the anterior side), en-hancement after contrast agent administra-tion, and high attenuation values in a child

with rheumatologic disease should indisput-ably alert radiologists for cardiac tamponade. KD, a self-limiting medium-sized-vessel vasculitis, is the primary cause of acquired pediatric heart disease worldwide. The inci-dence of KD is highest in Japan, with an an-nual incidence of approximately 112 cases per 100,000 children younger than 5 years old [28]. Fever, conjunctivitis, changes in the lips and oral mucosa, lymphadenopathy, and skin changes are the most consistent manifesta-tions of KD. Its major complicamanifesta-tions are ste-nosis and aneurysm formation (Fig. 5). Steno-sis is present in 25% of untreated and in 4% of treated cases [28]. KD has a 1–2% acute mortality rate due to myocardial infarction and, less often, rupture [29]. The right coro-nary artery is frequently involved (62% of coronary artery aneurysms) followed by the left main coronary artery. Chest radiograph is usually normal. CTA and MR angiography (MRA) are useful for detecting these changes and for follow-up. MRI also reveals myocar-dial perfusion in addition to wall thickening or thinning, luminal ectasia, and narrowing. In the emergency department, coronary CTA is crucial for children with KD, to detect the hallmark lesions of KD (i.e., aneurysm or ste-nosis). The differential diagnosis for KD in-cludes poststreptococcal scarlet fever, toxic shock syndrome, drug reactions, and system-ic-onset juvenile idiopathic arthritis. Children With Abdominal Complications

Henoch-Schönlein purpura (HSP), poly-arteritis nodosa (PAN), Wegener granulo-matosis, SLE, and juvenile idiopathic arthri-tis are generally associated with abdominal complications. Abdominal pain is a very common complaint of children in the emer-gency department. Abdominal pain trig-gered by rheumatologic disorders mainly stems from the gastrointestinal system and the abdominal vasculature. Bowel ischemia or edema is the leading cause of acute ab-domen in children diagnosed with vasculitis. Diagnostic workup should include all seri-ous complications, such as intestinal infarc-tion and perforainfarc-tion, and milder ones, such as intramural hemorrhage and intussuscep-tion. Sonography should be the first modality to evaluate abdominal pain because a nega-tive examination would not eliminate acute gastrointestinal system abnormalities. Thus, CT is generally needed for definitive diag-nosis, especially for assessment of the pa-tency of the abdominal vasculature.

Bowel-wall changes (e.g., edema, thickening, and enhancement) support the diagnosis of in-tramural bleeding and bowel ischemia (Fig. 6). The small intestine is the most commonly affected part of the gastrointestinal system, followed by the mesentery and colon. Gas-trointestinal system hemorrhage, bowel per-foration, and bowel infarction are not rare presentations [30, 31] (Fig. 7).

HSP is a special type of rheumatolog-ic disease generally affecting children 3–10 years old. HSP is the most common form of acute vasculitis and has typical clinical symptoms, such as abdominal pain, vomit-ing, gastrointestinal bleedvomit-ing, and hematu-ria [32]. Gastrointestinal hemorrhage mostly involves the mucosa and submucosa. Trans-mural necrosis and intestinal perforation are rare. Therefore, most gastrointestinal mani-festations are self-limited and only 3–5% of children develop bowel infarction, perfora-tion, or irreducible intussusception [33]. In-tussusception is typically ileoileal in HSP. CT may show bowel-wall thickening, mes-enteric edema, lymphadenopathy, and lumi-nal narrowing [34].

SLE is a chronic autoimmune disease in-volving any organ that may be manifest as abdominal symptoms. Childhood-onset SLE is rare and has an incidence of approximately 0.3–0.9 cases per 100,000 children [35]. The most serious complication of SLE in children is gastrointestinal system involvement. SLE enteritis is characterized by mesenteric vas-culitis that causes bowel ischemia. CT find-ings are generally very useful for detecting signs of mesenteric vasculitis, including non-specific focal or diffuse intestinal wall thick-ening, bowel-wall enhancement, mesenteric vascular engorgement, intestinal pseudoob-struction, irregularities in the mesenteric ar-teries, mesenteric edema, and ascites [36].

PAN, also called microscopic polyangi-itis and cutaneous polyarterpolyangi-itis, is a type of necrotizing polyarteritis affecting small- and medium-sized vessels. It is rare in childhood and the epidemiology is poorly defined in the literature. In general, the skin and the mus-culoskeletal and gastrointestinal systems are involved. To a lesser extent, but significantly, a high percentage of children with PAN have renal and CNS involvement as well [37]. Pa-tients with renal involvement can have pro-teinuria or hematuria. In the emergency de-partment, gastrointestinal and genitourinary complaints constitute most of the admissions.

Microaneurysm formation is one of the diagnostic criteria for PAN, but it is not

pathognomonic and can also be seen in oth-er vasculitides, including Wegenoth-er granulo-matosis, SLE, and juvenile idiopathic arthri-tis. Microaneurysms are typically 2–3 mm in size but can be up to 1 cm and cause bleeding due to focal rupture. In the kidneys, micro-aneurysms characteristically involve inter-lobar and arcuate arteries. Angiography is a far more sensitive modality for small-vessel alterations; however, CTA is also a method of choice for revealing microaneurysms and changes in the lumen and wall.

Children With Musculoskeletal Complications

Juvenile idiopathic arthritis and SLE are generally associated with musculoskeletal complications. Juvenile idiopathic arthritis is the most common rheumatic disease of childhood. The prevalence of juvenile idio-pathic arthritis is reported as 0.07–4.01 per 1000 children. Annual incidence is report-ed as 0.008–0.226 per 1000 children [38]. Juvenile idiopathic arthritis is the most common cause of acute joint swelling. Dif-fuse osteopenia, ankylosis, and paraarticu-lar erosions can also be seen. Other more urgent and severe causes of joint swelling, such as septic arthritis, should be excluded. Radiographs give basic information about joint space and paraarticular alterations. Synovitis and eventually pannus cause joint destruction. MRI and sonography can de-tect subclinical disease by revealing syno-vial hyperplasia and inflammation that can-not be seen with conventional radiography (Fig. 8). In the acute setting, MRI also has the advantage of revealing bone marrow changes that can be seen in both tumors and infections. Major complications of ju-venile idiopathic arthritis are subluxations, deformities, and ankylosis resulting in loss of function. Accordingly, prompt imaging is very important for early diagnosis and ap-propriate management.

Because the imaging findings are similar to those for joint effusion, synovial inflam-mation, joint-space narrowing, and paraar-ticular erosions, patients with juvenile id-iopathic arthritis may erroneously receive a diagnosis of septic arthritis. In some cas-es, differentiation between an acute exac-erbation of juvenile idiopathic arthritis and septic arthritis can be made only on the ba-sis of clinical manifestations and laborato-ry analysis of joint fluid [39]. Fundamental MRI findings of septic arthritis can be sum-marized as joint effusion, excessive synovial

enhancement, thickened synovium, and sy-novial defects [40]. Moreover, osteomyelitis usually accompanies septic arthritis via di-rect extension from the joint space to sub-chondral bone, causing low signal intensity on T1-weighted images; high signal intensi-ty on T2 fat-suppressed images in the corti-cal and medullary parts of the bone, which is consistent with bone marrow edema plus periosteal reaction; soft-tissue swelling and edema; and enhancement after contrast agent administration in the bone [41]. Children With Acute

Neurologic Complications

Rheumatologic disorders with likely neu-rologic complications in children are SLE, BD, PAN, Takayasu arteritis (TA), PAN, and Wegener granulomatosis. Clinical fea-tures and imaging findings depend on the underlying disease and anatomic location of the abnormality. Neuroemergent condi-tions associated with rheumatologic diseases are posterior reversible encephalopathy syn-drome (PRES), cerebral vasculitis, thrombo-sis of the main cerebral vascular structures, and intracranial hemorrhage.

PRES is a neurotoxic state with unique CT and MRI findings, such as symmetric focal brain edema at the watershed zones (Fig. 9). The lesions are almost always found in the parietal and occipital cortex and are best seen on FLAIR images. It occurs secondary to the inability of mainly the posterior circulation to autoregulate in response to acute changes in blood pressure. Although it is called pos-terior, it is not limited to the posterior circu-lation and can affect generally the watershed zones, including frontal, inferior temporal, cerebellar, and brainstem regions. Both cor-tical and subcorcor-tical areas are involved [42, 43]. Diffusion-weighted imaging is essential in revealing vasogenic edema (Fig. 9), which is usually completely reversible [44]. Cere-bral or cerebellar infarction or hemorrhage can be seen in the course of PRES in approx-imately 15% of the cases and is associated with poor prognosis [45]. Lesions can show a subcortical gyral enhancement pattern, in-dicating damage to the blood-brain barrier. Rheumatologic disorders with the potential for developing PRES in children are SLE, BD, PAN, and Wegener granulomatosis.

Thrombosis of the main cerebral arteries and veins can be seen in the course of TA, PAN, SLE, and BD. BD with brain involve-ment is usually manifest by tiny hyperin-tense areas on T2-weighted images and iso-

or hypointense areas on T1-weighted images. Shapes of the lesions vary; they can be lin-ear, circular, crescentic, and bizarre. Pons, cerebral peduncles, basal ganglia, and thal-amus are the typical locations for neuro-Be-hçet involvement [46, 47].

TA is responsible for thrombosis of the ce-rebral vasculature, resulting in acute neuro-logic symptoms. TA is a worldwide disease predominantly affecting large vessels, and it is the third most common vasculitis of child-hood [48]. TA usually affects the aorta, its major branches, and the pulmonary arteries. The most common artery affected by TA is the subclavian artery [49]. Although digital subtraction angiography, used to guide endo-vascular procedures such as stenting and an-gioplasty, is still the reference standard for pediatric onset TA, MRA is an emerging di-agnostic tool especially for revealing arterial wall inflammation, in addition to showing lu-minal flow–related abnormalities [50]. MRA and digital subtraction angiography have the ability to show the most common vascu-lar problems during the course of TA, such as stenosis, dilatation, occlusion, and aneu-rysms (Fig. 10). Arterial wall thickening and enhancement in acute phase, occlusion, an-eurysmatic dilatation, pseudoaneurysm of the major aortic branches, and narrowing of the arterial lumen in the late phase are the classic imaging findings on MRA [51].

CNS effects of SLE are characterized mainly by angiopathic involvement. Large vessel disease including thrombosis is more commonly seen in patients with antiphospho-lipid syndrome, which is a state of hyperco-agulability seen in children with SLE. Small-vessel angiitis is characterized by significant endothelial hyperplasia and intimal fibrosis in the small vessels of the brain, leading to occlusion. Thus, multiple small foci of sub-cortical infarctions and occasional hemor-rhages are the typical MRI findings in chil-dren with SLE and other types of vasculitis. Because of endothelial damage, blood-brain barrier disruption, hypertension, and cyto-toxic materials, PRES can be seen in children with SLE [52, 53]. The exact mechanism is not well understood. MRI findings are simi-lar to those observed in other disorders caus-ing PRES, includcaus-ing increased diffusion val-ues, extended T2 relaxation time, increased FLAIR signal levels, and varied amount of enhancement. Although it is less common-ly observed, CNS involvement in PAN (e.g., peripheral cerebral infarctions) [54] is also a reason for emergency department admissions.

Conclusion

Rheumatologic diseases in the pediatric population can involve many systems. Con-sidering the list of other diseases in the dif-ferential diagnosis, diligent assessment of the radiologic findings is paramount, and more than one imaging method may be required. References

1. Akikusa JD. Rheumatologic emergencies in new-borns, children, and adolescents. Pediatr Clin

North Am 2012; 59:285–299

2. Malleson PN, Fung MY, Rosenberg AM. The in-cidence of pediatric rheumatic diseases: results from the Canadian Pediatric Rheumatology As-sociation Disease Registry. J Rheumatol 1996; 23:1981–1987

3. Williamson SR, Phillips CL, Andreoli SP, Nai-lescu C. A 25-year experience with pediatric anti-glomerular basement membrane disease. Pediatr

Nephrol 2011; 26:85–91

4. Marten K, Schnyder P, Schirg E, Prokop M, Rum-meny EJ, Engelke C. Pattern-based differential diagnosis in pulmonary vasculitis using volumet-ric CT. AJR 2005; 184:720–733

5. Cortese G, Nicaji R, Placido R, Gariazzo G, Anro P. Radiological aspects of diffuse alveolar haem-orrhage. Radiol Med (Torino) 2008; 113:16–28 6. Primack SL, Miller RR, Muller NL. Diffuse

pul-monary hemorrhage: clinical, pathologic, and im-aging features. AJR 1995; 164:295–300 7. von Vigier RO, Trummler SA, Laux-End R,

Sau-vain MJ, Truttmann AC, Bianchetti MG. Pulmo-nary renal syndrome in childhood: a report of twenty-one cases and a review of the literature.

Pediatr Pulmonol 2000; 29:382–388

8. Ozen S, Petty RE. Behçet disease. In: Cassidy JT, Petty RE, Laxer RM, Lindsley CB, eds. Textbook

of pediatric rheumatology, 6th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier& Saunders, 2011:552–558

9. Krause I, Uziel Y, Guedj D, et al. Childhood Be-hçet’s disease: clinical features and comparison with adult-onset disease. Rheumatology 1999; 38:457–462

10. Ceylan N, Bayraktaroglu S, Erturk SM, Savas R, Alper H. Pulmonary and vascular manifestations of Behçet disease: imaging findings. AJR 2010; 194:[web]W158–W164

11. Kabbaj N, Benjelloun G, Gueddari FZ, Dafiri R, Imani F. Vascular involvements in Behçet dis-ease: based on 40 patient records (in French). J

Radiol 1993; 74:649–656

12. Gandía Herrero M, Andreo Martínez JA, Urbieta JB, Llanos Llanos R, Herrero Huerta F. Behçet disease with vascular involvement (in Spanish).

Med Clin (Barc) 2009; 133:159

13. Hiller N, Lieberman S, Chajek-Shaul T, Bar-Ziv J, Shaham D. Thoracic manifestations of Behçet

disease at CT. RadioGraphics 2004; 24:801–808 14. Avcin T, Tse SML, Schneider R, Ngan B, Silver-man ED. Macrophage activation syndrome as the presenting manifestation of rheumatic diseases in childhood. J Pediatr 2006; 148:683–686 15. Latino GA, Manlhiot C, Yeung RSM, Chahal N,

McCrindle BW. Macrophage activation syndrome in the acute phase of Kawasaki disease. J Pediatr

Hematol Oncol 2010; 32:527–531

16. Parodi A, Davi S, Pringe AB, et al. Macrophage activation syndrome in juvenile systemic lupus erythematosus: a multinational multicenter study of thirty-eight patients. Arthritis Rheum 2009; 60:3388–3399

17. Webb WR, Muller NL, Naidich DP. High

resolu-tion CT of the lung, 3rd ed. Philadelphia, PA: Lip-pincott Williams and Wilkins, 2001:403–405 18. Demirkazik FB, Akin A, Uzun O, Akpinar MG,

Ariyurek MO. CT findings in immunocompro-mised patients with pulmonary infections. Diagn

Interv Radiol 2008; 14:75–82

19. Heussel CP, Kauczor HU, Heussel GE, et al. Pneumonia in febrile neutropenic patients and in bone marrow and blood stem-cell transplant re-cipients: use of high-resolution computed tomog-raphy. J Clin Oncol 1999; 17:796–805

20. Gotway MB, Dawn SK, Caoili EM, Reddy GP, Araoz PA, Webb WR. The radiologic spectrum of pulmonary Aspergillus infections. J Comput

As-sist Tomogr 2002; 26:159–173

21. Caillot D, Casasnovas O, Bernard A, et al. Im-proved management of invasive pulmonary asper-gillosis in neutropenic patients using early tho-racic computed tomographic scan and surgery. J

Clin Oncol 1997; 15:139–147

22. Mok GC, Menahem S. Large pericardial effusions of inflammatory origin in childhood. Cardiol

Young 2003; 13:131–136

23. Roodpeyma S, Sadeghian N. Acute pericarditis in childhood: a 10-year experience. Pediatr Cardiol 2000; 21:363–367

24. Goldenberg J, Pessoa AP, Roizenblatt S, et al. Cardiac-tamponade in juvenile chronic arthritis: report of 2 cases and review of publications. Ann

Rheum Dis 1990; 49:549–553

25. Rosenbaum E, Krebs E, Cohen M, Tiliakos A, Derk CT. The spectrum of clinical manifesta-tions, outcome and treatment of pericardial tam-ponade in patients with systemic lupus erythema-tosus: a retrospective study and literature review.

Lupus 2009; 18:608–612

26. Spodick DH. Acute cardiac tamponade. N Engl J

Med 2003; 349:684–690

27. Restrepo CS, Lemos DF, Lemos JA, et al. Imag-ing findImag-ings in cardiac tamponade with emphasis on CT. RadioGraphics 2007; 27:1595–1610 28. Newburger JW, Takahashi M, Gerber MA, et al.

Diagnosis, treatment, and long-term management of Kawasaki disease: a statement for health profes-sionals from the Committee on Rheumatic Fever, Endocarditis, and Kawasaki Disease, Council on Cardiovascular Disease in the Young, American Heart Association. Pediatrics 2004; 114:1708–1733 29. Kato H, Sugimura T, Akagi T, et al. Long-term

consequences of Kawasaki disease: a 10- to 21-year follow-up study of 594 patients. Circulation 1996; 94:1379–1385

30. Ha HK, Lee SH, Rha SE, et al. Radiologic fea-tures of vasculitis involving the gastrointestinal tract. RadioGraphics 2000; 20:779–794 31. Travers RL, Allison DJ, Brettle RP, Hughes GR.

Polyarteritis nodosa: a clinical and angiographic analysis of 17 cases. Semin Arthritis Rheum 1979; 8:184–199

32. Mills JA, Michel BA, Bloch DA, et al. The Amer-ican College of Rheumatology 1990 criteria for the classification of Henoch-Sch

ö

nlein purpura.Arthritis Rheum 1990; 33:1114–1121

33. Martinez-Frontanilla LA, Haase GM, Ernster JA, Bailey WC. Surgical complications in Henoch-Schönlein purpura. J Pediatr Surg 1984; 19:434–436 34. Johnson PT, Horton KM, Fishman EK. Case 127:

Henoch-Schönlein purpura. Radiology 2007; 245:909–913

35. Kamphuis S, Silverman ED. Prevalence and bur-den of pediatric-onset systemic lupus erythemato-sus. Nat Rev Rheumatol 2010; 6:538–546 36. Taourel PG, Deneuville M, Pradel JA, Regent D,

Bruel JM. Acute mesenteric ischemia: diagnosis with contrast-enhanced CT. Radiology 1996; 199:632–636

37. Dedeoglu F, Sundel RP. Vasculitis in children.

Rheum Dis Clin North Am 2007; 33:555–583

38. Manners PJ, Bower C. Worldwide prevalence of juvenile arthritis why does it vary so much? J

Rheumatol 2002; 29:1520–1530

39. Lin HM, Learch TJ, White EA, Gottsegen CJ. Emergency joint aspiration: a guide for radiolo-gists on call. RadioGraphics 2009; 29:1139–1158 40. Graif M, Schweitzer ME, Deely D, Matteucci T.

The septic versus nonseptic inflamed joint: MRI characteristics. Skeletal Radiol 1999; 28:616–620

41. Donovan A, Schweitzer ME. Use of MR imaging in diagnosing diabetes-related pedal osteomyeli-tis. RadioGraphics 2010; 30:723–736

42. Bartynski WS. Posterior reversible encephalopa-thy syndrome. Part 2. Controversies surrounding pathophysiology of vasogenic edema. AJNR 2008; 29:1043–1049

43. Bartynski WS. Posterior reversible encephalopa-thy syndrome. Part 1. Fundamental imaging and clinical features. AJNR 2008; 29:1036–1042 44. Covarrubias DJ, Luetmer PH, Campeau NG.

Pos-terior reversible encephalopathy syndrome: prog-nostic utility of quantitative diffusion-weighted MR images. AJNR 2002; 23:1038–1048 45. McKinney AM, Short J, Truwit CL, et al.

Poste-rior reversible encephalopathy syndrome: inci-dence of atypical regions of involvement and im-aging findings. AJR 2007; 189:904–912 46. Borhani Haghighi A, Pourmand R, Nikseresht

AR. Neuro-Behçet disease: a review. Neurologist 2005; 11:80–89

47. Chae EJ, Do KH, Seo JB, et al. Radiologic and clinical findings of Behçet disease: comprehen-sive review of multisystemic involvement.

Radio-Graphics 2008; 28:e31

48. Brogan PA, Dillon MJ. Vasculitis from the pediatric perspective. Curr Rheumatol Rep 2000; 2:411–416 49. Maksimowicz-McKinnon K, Clark TM, Hoffman

GS. Limitations of therapy and a guarded progno-sis in an American cohort of Takayasu arteritis patients. Arthritis Rheum 2007; 56:1000–1009 50. Tso E, Flamm SD, White RD, Schvartzman PR,

Mascha E, Hoffman GS. Takayasu arteritis: utili-ty and limitations of magnetic resonance imaging in diagnosis and treatment. Arthritis Rheum 2002; 46:1634–1642

51. Sueyoshi E, Sakamoto I, Uetani M. MRI of Takayasu’s arteritis: typical appearances and complications. AJR 2006; 187:[web]W569–W575 52. Baizabal-Carvallo JF, Barragan-Campos HM,

Padilla-Aranda HJ, et al. Posterior reversible en-cephalopathy syndrome as a complication of acute lupus activity. Clin Neurol Neurosurg 2009; 111:359–363

53. Muscal E, Traipe E, de Guzman MM, Myones BL, Brey RL, Hunter JV. MR imaging findings suggestive of posterior reversible encephalopathy syndrome in adolescents with systemic lupus ery-thematosus. Pediatr Radiol 2010; 40:1241–1245 54. Provenzale JM, Allen NB. Neuroradiologic findings

in polyarteritis nodosa. AJNR 1996; 17:1119–1126

(Figures start on next page)

A

Fig. 1—17-year-old girl with Wegener granulomatosis

who presented with respiratory distress and hemoptysis.

A, Posteroanterior chest radiograph shows opacities

(arrows) within both lungs, mainly in right upper and middle zones.

B and C, Coronal reformatted (B) and axial plane

(C) chest CT images show nodular ground-glass opacities substantially on right lung and air-space consolidation on right upper lobe (arrows, B) representing alveolar hemorrhage.

B

C

A

Fig. 2—15-year-old boy with Behçet disease admitted for hemoptysis. A, Axial CT image shows ground-glass opacities in right lower lobe due to

pulmonary hemorrhage.

(Fig. 2 continues on next page)

B C

Fig. 2 (continued)—

15-year-old boy with Behçet disease admitted for hemoptysis.

B and C, Axial (B) and

coronal (C) reformatted contrast-enhanced CT images show arterial wall thickening (arrow, B) secondary to vasculitis. Note also that left lower lobe pulmonary artery is occluded (arrow, C).

A

Fig. 3—7-year-old

girl with Wegener granulomatosis and macrophage activation syndrome admitted for fever and pancytopenia.

A, Anteroposterior

chest radiograph shows patchy asymmetric ground-glass opacities and consolidations (arrows) predominantly at bases of lungs. B, Axial chest CT

image shows patchy consolidation (arrows) at periphery of lungs with 2- to 3-mm micronodules (arrowhead) and bronchial wall thickening. Cytomegalovirus pneumonia was diagnosed after polymerase chain reaction of bronchoalveolar lavage. B A

Fig. 4—11-year-old boy

with juvenile idiopathic arthritis admitted for severe chest pain and acute dyspnea. A, Posteroanterior radiograph shows enlargement of cardiac silhouette. B, Contrast-enhanced axial CT image shows bilateral pleural (stars) and pericardial (arrowhead) effusion. Hemorrhagic pericarditis was diagnosed after tube pericardiostomy. B

A

Fig. 5—9-year-old boy with Kawasaki disease.

A and B, Volume-rendered coronary CT angiography images obtained at spin and tilt angles of 65° and 95° (A) and 61° and −19° (B), respectively,

show aneurysmatic dilatation (arrows) of right and left coronary arteries. Note also stenoses (arrowheads) at distal part of right coronary artery and middle segment of left anterior descending coronary artery.

C, Maximum-intensity-projection image reveals calcification (arrow) on wall of left coronary artery.

C B

Fig. 6—9-year-old boy with Henoch-Schönlein purpura and new onset of acute

abdominal pain. Contrast-enhanced axial CT image reveals thickening of duodenal wall (white arrow), which is consistent with hemorrhage in intestinal wall. There is also free fluid and fat stranding (black arrow) adjacent to affected duodenal segment.

C

Fig. 7—8-year-old boy with polyarteritis nodosa.

A, Coronal reformatted maximum-intensity-projection CT angiogram shows

microaneurysms (arrows) in branches of hepatic artery. Three months later, child presented with severe abdominal pain, nausea, and vomiting.

B and C, Contrast-enhanced axial CT images show free air (arrows, B) consistent

with gastrointestinal perforation. Also note fluid (arrowhead, C), contrast enhancement, and bowel wall thickening (arrow, C) consistent with ileitis.

A B

A

Fig. 8—9-year-old girl with juvenile idiopathic arthritis and joint swelling. A and B, Coronal (A) and axial (B) T2-weighted turbo spin-echo and spectral

presaturation inversion recovery images show joint effusions (arrows) and signal changes secondary to synovial inflammation at third metacarpophalangeal and proximal interphalangeal joints.

B

A

Fig. 9—7-year-old girl with juvenile idiopathic arthritis and status epilepticus.

A–C, FLAIR (A and B) and diffusion-weighted (C) MR images show symmetric extensive interstitial-vasogenic edema (arrows, A–C) and narrowing of cerebral sulci

(arrowheads, A and B) in parietal, frontal, and occipital lobes, consistent with posterior reversible encephalopathy syndrome.

C B

A

Fig. 10—9-year-old girl with Takayasu arteritis and

new onset of syncope.

A and B, Digital subtraction angiography images

obtained of selective left (A) and right (B) common carotid artery injections show occlusion of left internal carotid artery (arrow, A) and reconstruction of left cerebral circulation via right internal carotid artery (arrowhead, B).

B