i

THE EFFECT OF

LANGUAGE LEARNING STRATEGY TRAINING ON LEARNER AUTONOMY AND

FOREIGN LANGUAGE ACHIEVEMENT

NURAY OKUMUŞ CEYLAN

PhD THESIS

FOREIGN LANGUAGE EDUCATION

GAZI UNIVERSITY

INSTITUTE OF EDUCATIONAL SCIENCES

ii

TELİF HAKKI ve TEZ FOTOKOPİ İZİN FORMU

Bu tezin tüm hakları saklıdır. Kaynak göstermek koşuluyla tezin teslim tarihinden itibaren 12 ay sonra tezden fotokopi çekilebilir.

YAZARIN Adı: NURAY

Soyadı: OKUMUŞ CEYLAN Bölümü: İNGİLİZ DİLİ EĞİTİMİ İmza:

Teslim tarihi:

TEZİN

Türkçe Adı: Dil öğrenme stratejileri eğitiminin öğrenci özerkliği ve dil öğrenme başarısına etkisi

İngilizce Adı: The effect of language learning strategy training on learner autonomy and language learning achievement

iii

ETİK İLKELERE UYGUNLUK BEYANI

Tez yazma sürecinde bilimsel ve etik ilkelere uyduğumu, yararlandığım tüm kaynakları kaynak gösterme ilkelerine uygun olarak kaynakçada belirttiğimi ve bu bölümler dışındaki tüm

ifadelerin şahsıma ait olduğunu beyan ederim.

Yazar Adı Soyadı: NURAY OKUMUŞ CEYLAN İmza: ………

iv

Jüri onay sayfası

Nuray OKUMUŞ CEYLAN tarafından hazırlanan “The Effect of Language Learning Strategy Training on Learner Autonomy and Foreign Language Achievement” adlı tez

çalışması aşağıdaki jüri tarafından oy birliği ile Gazi Üniversitesi Eğitim Bilimleri Enstitüsü Yabancı Diller Anabilim Dalı’nda Doktora tezi olarak kabul edilmiştir.

Danışman: Yrd. Doç. Dr. Abdullah ERTAŞ

(İngiliz Dili Eğitimi, Atılım Üniversitesi) ………

Başkan: Doç. Dr. Arif SARIÇOBAN

(İngiliz Dili Eğitimi, Hacettepe Üniversitesi) ………

Üye: Yrd. Doç. Dr. Cemal ÇAKIR

(İngiliz Dili Eğitimi, Gazi Üniversitesi) ………

Üye: Yrd. Doç. Dr. Gültekin BORAN

(İngiliz Dili Eğitimi, Gazi Üniversitesi) ………

Üye: Yrd. Doç. Dr. Hüseyin ÖZ

(İngiliz Dili Eğitimi, Hacettepe Üniversitesi) ………

Tez Savunma Tarihi: 11.07.2014

Bu tezin Yabancı Diller Eğitimi Anabilim Dalı’nda Doktora tezi olması için şartları yerine getirdiğini onaylıyorum.

v

vi

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

First of all, I would like to thank my thesis advisor, Assist. Prof. Abdullah Ertaş for his invaluable guidance and support throughout my study.

I would also thank Assoc. Prof. Arif Sarıçoban and Assist. Prof. Cemal Çakır for their help and support.

I owe much to my colleague and my sincere friend Evren Köse Yuca who supported me with her help and invaluable friendship in this study.

I also would like to thank to my husband, Sezai Ceylan and my dear daughter, Defne, without their love, support and patience; this thesis could not have been written.

I would also thank my family for their invaluable love and support.

vii

DİL ÖĞRENME STRATEJİLERİ EĞİTİMİNİN ÖĞRENCİ

ÖZERKLİĞİ VE YABANCI DİL ÖĞRENME BAŞARISINA ETKİSİ

(Doktora Tezi)

Nuray OKUMUŞ CEYLAN

GAZİ ÜNİVERSİTESİ

EĞİTİM BİLİMLERİ ENSTİTÜSÜ

Temmuz, 2014

ÖZ

Bu çalışmanın amacı yabancı dil öğrencilerine özerklik seviyelerini artırmak için dil öğrenme stratejileri eğitimi vermenin yabancı dil öğrenme başarıları üzerine olumlu bir etkisi olup olmadığını bulmaktır. Çalışma 2013- 2014 eğitim- öğretim yılı Kocaeli Üniversitesi Yabancı Diller Yüksekokulu İngilizce Hazırlık öğrencileriyle gerçekleştirilmiştir. Deney ve kontrol gruplarının yer aldığı deneysel bir çalışmadır. Çalışmada rastgele seçilmiş dört B (başlangıç seviyesi) ve dört A (orta seviye) sınıfları yer almıştır. Öğrencilerin dil seviyeleri 2013- 2014 eğitim öğretim yılı başında yapılan seviye tespit sınavıyla belirlenmiş ve öğrenciler seviyelerine ait sınıflara yerleştirilmiştir. Sınıfların İngilizce seviyeleri birbirine denktir. Güz dönemi başında deney ve kontrol gruplarına dil öğrenme stratejileri ve öğrenci özerkliği anketleri ön-testleri uygulanmıştır. Sonrasında, deney grupları belirlenen sure boyunca dil öğrenme stratejileri eğitimi almış ve dönem sonuna kadar dil öğrenme stratejileri kullanımlarıyla ilgili gözlemlenmiştir. Dönem sonunda dil öğrenme stratejileri ve öğrenci özerkliği anketleri son-testleri uygulanmıştır. Veri analizinde ön-test sonuçlarıyla her iki grubun öğrenci özerkliği seviyeleri ve dil öğrenme stratejileri kullanımı tespit edilmiştir. Ön-test ve son-test sonuçlarının kıyaslanmasıyla dil öğrenme strateji eğitiminin etkisi araştırılmıştır. Araştırmanın sonucunda deney grubu öğrencilerinin dil öğrenme stratejileri ön-test ve son-test sonuçları arasında önemli bir fark oluşmuştur. Dil öğrenme stratejileri eğitimi alan özellikle başlangıç seviyesi öğrencilerinin yabancı dil başarıları artmıştır. Bu çalışma, öğrencileri dil öğrenme stratejileri konusunda eğitmenin öğrenci özerkliği seviyelerini artırdığını, bunun da yabancı dil öğrenme başarısını artırdığını göstermiştir.

Bilim Kodu: İngiliz Dili Eğitimi

Anahtar Kelimeler: öğrenci özerkliği, dil öğrenme stratejileri Sayfa Adedi: 151

viii

THE EFFECT OF LANGUAGE LEARNING STRATEGY TRAINING

ON LEARNER AUTONOMY AND FOREIGN LANGUAGE

ACHIEVEMENT

(Ph.D Thesis)

Nuray OKUMUŞ CEYLAN

GAZI UNIVERSITY

INSTITUTE OF EDUCATIONAL SCIENCES

July, 2014

ABSTRACT

In this study, the population is Kocaeli University 2013- 2014 education year Foreign Languages School students. This study is an experimental study in which experimental and control classes are chosen to take part in the study. There are eight classes randomly chosen, four B (beginner/ elementary) level classes and four A (pre-intermediate/ intermediate) level classes take part in the study. The level of the classes is identified by the placement test conducted at the beginning of 2013- 2014 education year. The students are assigned to the classes based on their placement test results. At the beginning of the fall term, language learning strategies and learner autonomy surveys were conducted as pre- tests. Then, the experimental classes were trained on language learning strategies for the defined period of time and observed until the end of the first term on their use of the language learning strategies. The control groups did not receive the training. At the end of the first term, language learning strategies and learner autonomy surveys were conducted again as post- tests. The significant difference between the overall averages of the first term grades of beginner/ elementary level control and experimental groups shows that training students on language learning strategies may lead to better foreign language proficiency, particularly in lower levels. We might conclude that the more strategies the students employ or more frequently more autonomous they become by starting to shoulder the responsibility of their own learning process. Thus, their language learning proficiency increases.

Science Code: English Language Teaching

Key Words: learner autonomy, language learning strategies Page Number: 151

ix

TABLE OF CONTENTS

ÖZ ………..…….v ABSTRACT ………..vi TABLESINTRODUCTION

..…………...………..……...1Statement of the Problem ………...……….3

Aim of the study ………..…….……….……...…....5

Significance of the Study ………..………...…..……...6

Premises ……….…….……….…...……..6

Limitations ……….………..………....7

Definitions ………..………....…...7

REVIEW OF LITERATURE

……….…….…………...………..………...…..9Learner Autonomy ……….…...9

Teacher’s Role in Learner Autonomy ………...…..10

Research on Learner Autonomy in Language Teaching ………..……….…....11

Language Learning Strategies ………...…………...…….12

Language Learning Strategies Studies Conducted in Turkey ……….…...26

Training Learners on Language Learning Strategies ……...……...…....28

Research on Learner Training ……...……….…………...……...31

Fostering Learner Autonomy ………...……...…36

METHODOLOGY

…………...…………...……….………...…39Research Design ………..………..…….………...…...39

Population and Sample ………...………..…………...40

Strategy Training ………...…………41

Reading Strategies ………..……….. 43

Listening Strategies ………..….43

x

Vocabulary Strategies ………..…….…44

Writing Strategies ………...………...45

Indirect Strategies ……….…...45

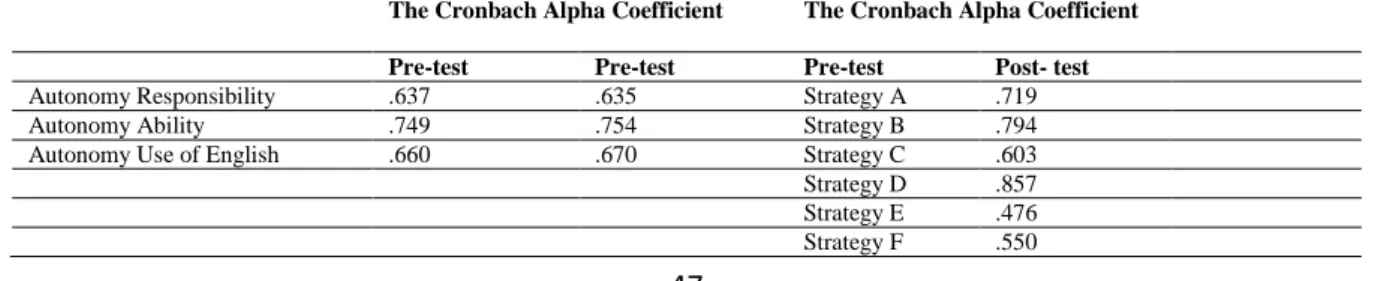

Instruments ………...………..……..…..………...46

Reliability and Validity …………...………...……..…………..…...47

DATA ANALYSIS

...…….………...………...……..49What is Kocaeli University Preparatory School (KOUPS) students’ level of learner autonomy? ………...49

The role of the teacher ………...50

Learner Autonomy………..…...51

About High School Education……….…..52

Responsibility………..………....54

Abilities………..……….…...57

Use of English……….…...58

What sort of language learning strategies do KOUPS’ students employ?...60

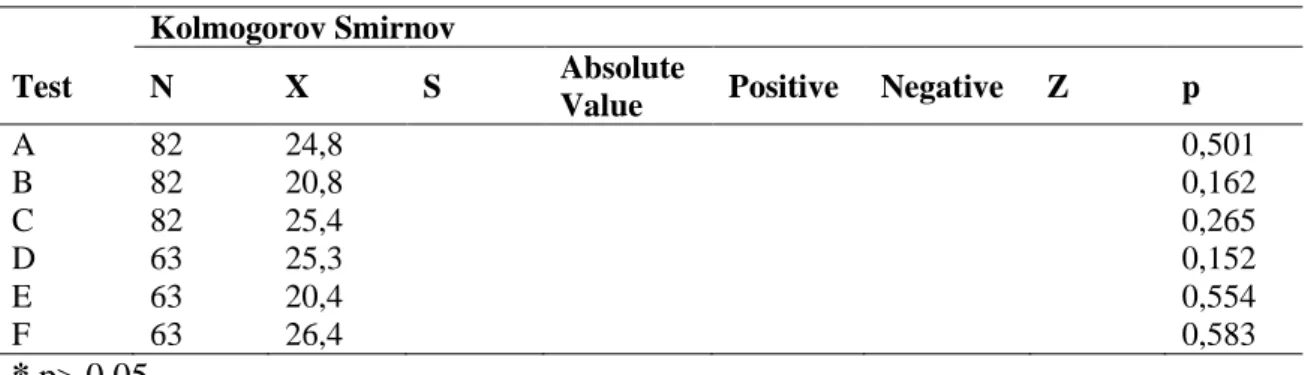

In the pre-test prior to the study, do the experimental groups significantly differ from control groups in terms of a. learner autonomy and b. language learning strategies? ………...………….66

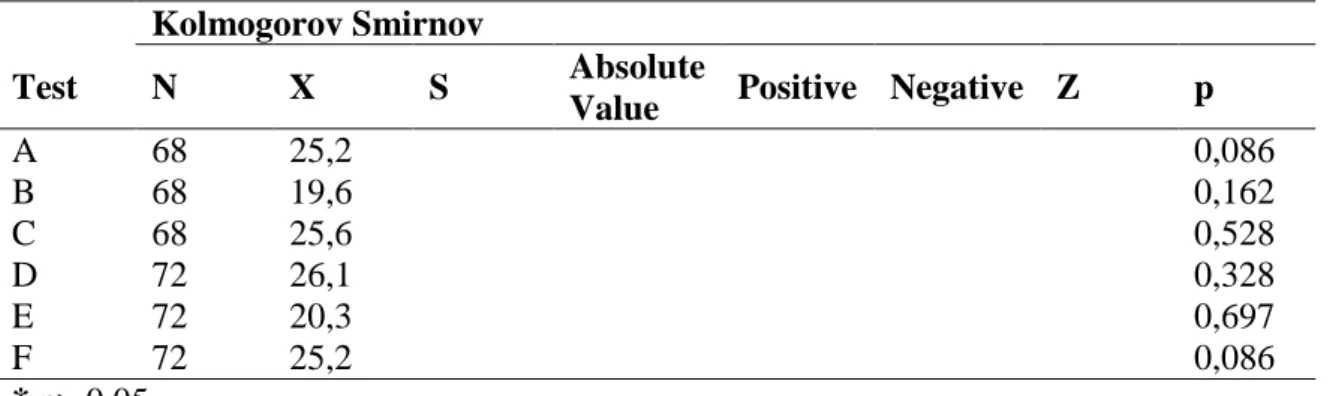

In the post-test after the study, do the experimental groups significantly differ from control groups in terms of a. learner autonomy and b. language learning strategies? ………...……….67

Is there any statistically significant difference between the pre- and post-test scores of the control groups in terms of a. learner autonomy and b. language learning strategies? ………...……….…69

Is there any statistically significant difference between the pre- and post-test scores of the experimental groups in terms of a. learner autonomy and b. language learning strategies? ………...….……….…71

xi

Does training students on language learning strategies have an effect on

learner autonomy and foreign language achievement? ………...72

Does any correlation exist between learner autonomy and language learning strategies? ………..……….…...…..73

FINDINGS AND DISCUSSION

..…...……….………...…………....77Autonomy Questionnaire .…………..……….…...………...77

Strategy Questionnaire .…………...………...………...80

The Effect of Language Learning Strategy Training on Learner Autonomy...81

CONCLUSION AND SUGGESTIONS

..…………..………..………….85Implications for further research ………...…...89

APPENDICES ….

………..….101xii

LIST OF TABLES

Table 1. Wenden’s Taxonomy of Language Learning Strategies (1998)…………...16

Table 2. Rubin’s Taxonomy of Language Learning Strategies (1981) ………...17

Table 3. Naiman et. al.’s Taxonomy of Language Learning Strategies (1978) ....…...18

Table 4. Stern’s Taxonomy of Language Learning Strategies (1992: 262- 266) ……...19

Table 5. O’Malley & Chamot’s Taxonomy of Language Learning Strategies (1990) ….20 Table 6. Oxford’s Taxonomy of Direct Language Learning Strategies (1990) …...…21-23 Table 7. Oxford’s Taxonomy of Indirect Language Learning Strategies (1990) …….….24

Table 8. Participants ……….………..………...…..41

Table 9. Reading strategies and activities covered in the training ……….……….……..43

Table 10. The Cronbach Alpha Coefficient of the Surveys …….………...47

Table 11. Autonomy Survey Analysis of the Control Groups ……….…...49

Table 12. Autonomy Survey Analysis of the Experimental Groups …….…...……...…....50

Table 13. The role of the teacher (Control groups) ………..………...50

Table 14. The role of the teacher (Experimental groups) ………..………..51

Table 15. Learner autonomy (Control groups) ………..…………...……...51

Table 16. Learner autonomy (Experimental groups) ………..……...…………...51

Table 17. Criteria for the Mean Scores of “About High School Education” …………..…52

Table 18. About High School Education (Control groups) ………...………....53

Table 19. About High School Education (Experimental groups) ……..………….…...….54

Table 20. Responsibilities (Control groups) ……….……...…………...55

Table 21. Responsibilities (Experimental groups) ……….………..……...56

Table 22. Abilities (Control groups) ……….………...….57

Table 23. Abilities (Experimental groups) ………….………..…...58

Table 24. Activities (Control groups) ………….………...…...59

Table 25. Activities (Experimental groups) ………..……...……...59

xiii

Table 27. Analysis of Pre and Post Strategy Surveys of Experimental Groups …...….61 Table 28. Key to SILL Averages (Oxford, 1990) ………..………...61 Table 29. The Result of the Strategy Pre-Survey of Control Groups ……..……....…..62-63 Table 30. The Result of the Strategy Pre-Survey of Experimental Group …..………..64-65 Table 31. Independent T-test results of Control and Experimental Groups Autonomy

Pre- Test Responsibility Section ………...………...66 Table 32. Independent T-test results of Control and Experimental Groups Autonomy

Pre- Test Ability Section ……….………...…..…...66 Table 33. Independent T-test results of Control and Experimental Groups Autonomy

Pre- Test Use of English Section ………...…..…………...67 Table 34. Independent T-test results of Control and Experimental Groups Strategy

Pre- Test ……….…………...67 Table 35. Independent T-test results of Control and Experimental Groups Autonomy

Post- Test Responsibility Section ………...………...67 Table 36. Independent T-test results of Control and Experimental Groups Autonomy

Post- Test Ability Section ………...……….…....68 Table 37. Independent T-test results of Control and Experimental Groups Autonomy

Post- Test Use of English Section ………..………...…...………...68 Table 38. Independent T-test results of Control and Experimental Groups Strategy

Post-Test………...……….…...68 Table 39. Paired Samples T- test Results of the Control Group Pre- and Post- Autonomy

Survey Responsibility Section ………...…….………...69 Table 40. Paired Samples T- test Results of the Control Group Pre and Post Autonomy

Survey Ability Section ………...………….…………...70 Table 41. Paired Samples T- test Results of the Control Group Pre- and Post- Autonomy

Survey Use of English Section ………...…….……...….70 Table 42. Paired Samples T- test Results of the Control Group Pre- and Post- Strategy

Surveys………...……….………....…..70 Table 43. Paired Samples T- test Results of the Experimental Group Pre- and

Post- Autonomy Survey Responsibility Section……..………....………71 Table 44. Paired Samples T- test Results of the Experimental Group Pre- and

xiv

Table 45. Paired Samples T- test Results of the Experimental Group Pre and Post

Autonomy Survey Use of English Section ………...…………...……....72 Table 46. Paired Samples T- test Results of the Experimental Group Pre- and

Post- Strategy Surveys ..………...……….…...…72 Table 47. The overall averages of control and experimental groups ……...……….72 Table 48. Correlation Analysis of Parts of Strategy Survey and Autonomy Survey of

Experimental Groups ……….…………...…...75 Table 49. The Results of the Multiple Regression Analysis of the Responsibility, Ability

xv

ABBREVIATIONS

KOUPS Kocaeli University Preparatory School SILL Strategy Inventory for Language Learning

EFL English as a Foreign Language

ELT English Language Teaching

CALL Computer Assisted Language Learning

LCSI Listening Comprehension Strategy Inventory TOEFL Test of English as a Foreign Language

ASRA Adult Survey of Reading Attitude

1

CHAPTER I

INTRODUCTION

Learner autonomy or self-direction give learners the opportunity to reclaim responsibility for and control over their own education, of taking greater control of their learning, of autonomy as a right learners have. Learning how to apply language learning strategies and how to improve their skills may be beneficial to them when they must cope with a vast amount of information for specific tasks in their professional lives. With learning training, teachers aim to help students to improve their language skills so that they will become more successful or effective as learners. Becoming independent learners may make students more competent persons (Kohonen, 1991). As Sinclair (2000: 66) states learner training may help them, “Learner training aims to help learners consider the factors that affect their learning and discover the learning strategies that suit them best and which are appropriate to their learning context, so that they may become more effective learners and take on more responsibility for their own learning” As the literature on the relationship between learner autonomy and language achievement (Ablard& Lipschultz, 1998, Corno& Mandinach, 1983, Zimmerman& Risenberg, 1997, Zhang& Li, 2004, Dafei, 2007) suggests fostering learner autonomy may result in better language achievement.

Holec (1981: 3) defines learner autonomy as follows: “to take charge of one’s own learning is to have, and to hold, the responsibility for all the decisions concerning all aspects of this learning”. Holec (1981) defines these aspects of learning as:

determining the objectives;

defining the contents and progressions; selecting methods and techniques to be used;

2

evaluating what has been acquired

According to Benson (2001: 50), “an adequate description of autonomy in language learning should include three levels at which learner control may be exercised: learning management, cognitive processes and learning content”. His explanation is: “effective learning management depends upon control of the cognitive processes involved in learning, while control of cognitive processes necessarily has consequences for the self-management of learning. Benson states that autonomy requires that the learner self directs his/ her metacognitive and cognitive processes which also requires taking decisions on the content to be learned.

Littlewood (1996) classifies autonomy as proactive and reactive autonomy. In proactive autonomy, the learner determines objectives, selects methods and evaluates what he has learned. In reactive autonomy, the learner organizes resources autonomously to reach his goal in an initiated direction. Benson (2001) explains proactive autonomy as control over content and reactive autonomy as control over method. This study focuses on learner autonomy in a school context where the students proceed through already defined content; therefore, what we refer to as autonomy should better be regarded as reactive autonomy. As Benson (2001) states, “Learner control of the cognitive processes involved in language learning is a crucial factor in what is learned.” Since as Nunan (1996) states, “learners tend to follow their own agendas rather than those of their teachers” (195b: 135). Dakin (1973: 16) supports this statement with his following argument, “though the teacher may control the experiences the learner is exposed to, it is the learner who selects what is learnt from them”.

The literature on the relationship between learner autonomy and language achievement (Ablard& Lipschultz, 1998, Corno& Mandinach, 1983, Zimmerman& Risenberg, 1997, Zhang& Li, 2004, Dafei, 2007) initially proposed that learner autonomy could help to improve the language achievement of learners and concluded that autonomous learners were the learners of high language achievement. According to the study of Zimmerman& Risenberg (1997), a high degree of learner autonomy among the high-achieving students would achieve high scores and the learner with low degrees of learner autonomy was likely to risk achieving the low scores if learner autonomy could augment the academic scores.

3

Zhang& Li (2004) concluded that learner autonomy was closely related with the language levels.

According to the results of Dafei (2007), learners’ English proficiency increases with their learner autonomy and vice versa. He states that by fostering students’ learner autonomy in second or foreign language teaching and learning may help improve their proficiency in English; the more autonomous the learner becomes the more likely s/he achieves high language proficiency. In his study, the teachers who were interviewed agreed that high proficiency students were more autonomous than low-proficient students. Moreover, high-proficient students had a high capacity to manage the processes of their own learning and the latter group had a low degree to do so.

The Statement of the Problem

“Human knowledge is developed, transmitted and maintained in social situations” (Berger& Luckman, 1967 cited in Wenden& Rubin (1987) and that in these social situations language has the central role. “Language is the main channel through which the patterns of living are transmitted to the child, through which the child learns to act as a member of society and, …to adopt its culture, modes of thought, … its belief and values” (Halliday, 1978: 9). For the learner, then language is both a subject of study and a means of receiving a meaningful world from others and is at the same time a means of re-interpreting the world to his own ends” (Barnes, 1976). Since knowledge of language cannot be defined or even understood without taking into account of the goals and purposes of a person who is attempting to gain this knowledge successful language teaching must therefore start from the learner rather than the language and the language learners must be made aware of the fact that they are the most important element in the learning process. In this way, they learn how to learn for the purposes they design for themselves.

As Dickinson (1987: 9) points out, “the key to understanding this is the concept of responsibility for learning.” The act of learning is, of course, personal and individual. Learners have the final responsibility of knowing whether or not they know, whatever type

4

of “knowing” that might be, when in real-life situations which are “actively symbolized” by language (Halliday, 1978: 3). But in order to reach this level of being able to use language to “create meanings of a social kind” and to “participate in verbal contest and verbal display” (Halliday, 1978), the learner has to learn the process of learning and to be able to manage the complex learning network of learning goals, materials, sequencing of the materials, deciding how materials shall be used, deciding on tasks to be done, keeping records and making evaluations.

This organization of learning material and mapping pathways through it has been traditionally the responsibility of the teacher. Through the work of educationalists such as Biggs (1991), Hounsell (1997), and Entwistle (1981) in learning strategies and learning outcomes, our understanding of the learning process itself has become clearer. Our definition of what a good learner is has been modified to include those who are “good thinkers and problem solvers whose cognitive strategies enable them to exercise control over their own learning” (Gagné, 1977).

This metacognitive awareness means that the learner can no longer be regarded as a container into which information is crammed by an autocratic disseminator of knowledge. The learner must be a “participant in the learning process” as (Harri- Augstein& Thomas, 1979) puts it where “meaning is a product of social interaction”. Learners must be enticed to accept responsibility not just for their learning but for the process involved in it. They must be ready to make decisions about how to manage all the complexities involved. Under the statements mentioned above, the problem might be defined in question form as:

1. What is Kocaeli University Preparatory School (KOUPS) students’ level of learner autonomy?

2. What sort of language learning strategies do KOUPS’ students employ?

3. In the pre-test prior to the study, do the experimental groups significantly differ from control groups in terms of

a. learner autonomy and

5

4. In the post-test after the study, do the experimental groups significantly differ from control groups in terms of

a. learner autonomy and

b. language learning strategies?

5. Is there any statistically significant difference between the pre- and post-test scores of the control groups in terms of

a. learner autonomy and

b. language learning strategies?

6. Is there any statistically significant difference between the pre- and post-test scores of the experimental groups in terms of

a. learner autonomy and

b. language learning strategies?

7. Does training students on language learning strategies have an effect on learner autonomy and foreign language achievement?

8. Does any correlation exist between learner autonomy and language learning strategies?

Aim of the Study

This study aims to provide students with the awareness that the responsibility of learning is their responsibility, not the teachers. Okumuş (2009) shows that “though students in Zonguldak Karaelmas prep school seem to shoulder the responsibility of learning, most students need guidance of their teachers to set goals for their learning process”. The fact that they want to be guided by their teacher is a sign of low autonomy. Taking Turkish education system into consideration, we may regard this as a natural consequence of the education they have gotten since the early years of their school life where the teacher is in the center of the curriculum as the source of the information. This shows that they may be willing to shoulder the responsibility, but as a result of a teacher dependent education system for at least 11 years, they may not know how to do it taking into consideration the possible effects of Turkish education system on students at prep schools of state

6

universities. This study aims to find out whether learner training may result in better language achievement or not by training foreign language learners on language learning strategies to become more autonomous.

Significance of the Study

Since there are many options today for language learners outside the classroom context, providing students with essential research strategies has become much more important than making them learn limited amount of knowledge merely in the classroom from the language teacher. In such a learning environment, the role of the teacher is changing from the status of a “genius” who knows all to a “guide” who shows where and how to access knowledge and how to adapt or adopt it. We cannot expect learners to make the leap from total domination in the school classroom to full autonomy in the university. According to Holec (1985) learner training should prepare students to direct their own learning so that they may gradually move from a state of dependence on a teacher to the greatest degree of independence or autonomy. Learning training is seen as taking learners “further along the road to full autonomy” (Voller, Martyn& Pickard, 1999). Thus, self-directed learning is the realization of a learner’s potential for autonomy. Therefore, emphasis should be focused on providing them with skills and raising an awareness for language learning strategies to teach how to learn languages.

Premises

Many researchers have explicitly stressed the importance of learner training for learner autonomy (e.g. Holec, 1981; Huttunen, 1986; Cotterall, 1995; Dickinson, 1995; Dam 1995; Oxford, 1990; Wenden, 1991). Benson (2001: 146) states that “there is good evidence that learner development programs can be effective in improving language learning performance. As Logan& Moore (2003: 1) states we can not assume that learners know how to learn. As Holec (1979: 27) points out, “few adults are capable of assuming responsibility for their learning... for the simplest reason that they have never had the

7

occasion to use this ability”. Thus, as Tudor (1996: 34) states, “the knowledge and personal qualities that learner involvement requires can not be taken for granted and need to be developed over time”. The researcher hypothesizes that there might be a difference in students’ learner autonomy by training them on language learning strategies that may assist them in their language learning process.

Limitations

The fact that the study was conducted in eight classes (four experimental and four control classes) which are chosen among the prep school students in Kocaeli University is a limitation. Another limitation is that the students were trained for a short period of time based on the prep school syllabus of the 2013- 2014 academic year.

Definitions

Learner autonomy: to take responsibility of one’s own learning by giving all the decisions related to the learning process.

Proactive autonomy: the learner determines objectives, selects methods and evaluates what he has learned.

Reactive autonomy: the learner organizes resources autonomously to reach his goal in an initiated direction.

9

CHAPTER II

REVIEW OF LITERATURE

The focus of much research in education is on defining how learners can take charge of their own learning and how teachers can help students to become more autonomous (Wenden& Rubin, 1987). Holec (1981) describes an autonomous learner in various aspects. An autonomous learner is capable of

• determining the objectives

• defining the contents and progressions • selecting methods and techniques to be used

• monitoring the procedure of acquisition properly speaking (rhythm, time, place, etc) • evaluating what has been acquired

Autonomous learners have the capacity to determine realistic and reachable goals, select appropriate methods and techniques to be used, monitor their own learning process, and evaluate the progress of their own learning (Little, 1991). According to Dam (1990), an autonomous learner is an active participant in the social processes of learning and an active interpreter of new information in terms of what she/he already and uniquely knows. Autonomous people are intrinsically-motivated, perceive themselves to be in control of their decision-making, take responsibility for the outcomes of their actions and have confidence in themselves (Deci& Ryan, 1985; Bandura, 1989; Doyal& Gough, 1991). Candy (1991) extends the features by adding several crucial aspects related to autonomy. Autonomous learners:

• are methodical and disciplined • are logical and analytical

10

• are reflective and self-aware • demonstrate curiosity • are flexible

• are persistent and responsible • are venturesome and creative

• show confidence and have a positive self-concept • are independent and self-sufficient

• have developed information seeking and retrieval skills • have knowledge about, and skill at, learning experiences • develop and use criteria for evaluating

Dickinson (1995) underlines the importance of learner autonomy while giving five features of autonomous learners. Autonomous learners:

1. understand what is being taught, i.e. they have sufficient understanding of language learning to understand the purpose of pedagogical choices

2. are able to formulate their own learning objectives

3. are able to select and make use of appropriate learning strategies 4. are able to monitor their use of strategies

5. are able to self-assess, or monitor their own learning

Teacher’s Role in Learner Autonomy

Tudor (1993) suggests that the main role of the teacher in the traditional modes of teaching is the supplier of knowledge. That is, the teacher is the figure of authority as a source of knowledge, deciding on what will be learned and how will that be learned. Additionally, organizing is another role the teacher takes in setting up the activities, motivating the students and providing authoritative feedback on students’ performance. However, in many language programs promoting learner autonomy teachers need to change their role from supplier of information to counselor so as to help learners to take significant responsibility by setting their own goals, planning practice opportunities, or assessing their progress. The programs of most language courses, which aim to promote learner autonomy, involve transferring responsibility from the teacher to the learner for the language learning process.

11

Also as Gremmo and Riley (1995) states, a teacher can take the role of counseling. Firstly, he or she is supposed to assist learners to establish set of values, ideas and techniques in the language learning process. In other words, the teacher as a counselor is able to raise the awareness of his or her language learning. Secondly, the teacher can establish and manage the resource center or self-access center, which can be described as the role of staff in self- access centers. The task here involves providing information and answers about the available materials in the self-access center.

Research on Learner Autonomy in Language Teaching

The research conducted on learner autonomy in Turkey focuses on the attitudes of the learners and the teachers towards learner autonomy and how to encourage the learners to become more autonomous. Kennedy (2002) conducted a case study with 23 students at the Institute of Business Administration. The study aimed to see to what extent learner autonomy can be encouraged among a group of Turkish students. Firstly, the researcher carried out some practical activities to foster independence among students. These activities involved diary writing, use of monolingual dictionary, use of grammar reference books with answer keys, joke telling, writing summaries and conducting research. After seven months, the researcher asked 23 students to write a detailed evaluation of the course. Students’ main criticism focused on more grammar practice although some expressed their enthusiasm in writing diaries. The researcher has concluded that it is not surprising that learner autonomy has much importance to the students. He adds that promoting learner autonomy in the EFL classroom in Turkey is not an easy struggle and it would be a mistake to expect too much too soon from Turkish learners who have traditional experiences prior to entering English language classrooms.

In her study, Yumuk (2002) aimed to design and evaluate a program to promote a change in students’ attitudes from a traditional, recitation-based view of learning to a more autonomous view of learning. As part of the program, the students were encouraged to use Internet for selection, analysis, evaluation and application of relevant information so that they could improve the accuracy of their translations. The researcher stated that the use of searching and application of Internet-based information helped students to think and reflect

12

critically on their learning. The evaluation of the program was conducted with pre and postcourse questionnaires, post-course interviews and information recorded weekly in a diary by the teacher as a researcher. The results revealed that the program promoted a change in the view of learning towards more autonomy. The researcher concluded that the majority of the students reported that the translation process required more responsibility from them, and they also viewed learning more meaningfully.

Çoban (2002) conducted a comparative study to investigate the attitudes towards learner autonomy in Gazi University and Yıldız Technical University. The researcher designed a-26-item questionnaire, which has three dimensions: teacher-learner roles, definitions of autonomy, and ways of developing learner autonomy. The questionnaire was employed to 35 English language teachers, 16 were from Gazi University and 19 were from Yıldız Technical University Modern Languages Department. The study revealed that language teachers in both institutions tended to favor encouraging learners to take active roles in the language learning process. However, they seemed to be unwilling to let students make some decisions concerning the lesson, e.g. selecting the content of the course or choosing methods and techniques. Another finding drawn from the study was that language teachers in Yıldız Teknik University were more likely to support ways of developing learner autonomy, particularly in giving choice to learners, self-monitoring and self-evaluation. Kucuroğlu (2000) aimed to assess the role of a learner-centered approach in language teaching in the development of learner autonomy by means of examining the principles and design features of a freshman year English course, namely English-2 offered at Doğuş University. In her study, the researcher discussed the design of the model course which has five main features: assessment of learners’ needs, allowing learners’ choices in learning, authenticity of textual materials, learners in change and the roles of teachers. The researcher argued that this course with the characteristics mentioned above could take students through the stages of conducting academic research and helps them increase their confidence in working on their own as well as learning to take the responsibility for their own learning. Finally, the researcher concluded that the model course promoted learner autonomy as it was designed with the principles of communicative language teaching and learner-centeredness in language education.

13

Yıldırım (2005) conducted a study to find out ELT learners’ perceptions and behaviour with regard to learner autonomy both as learners of English and as future English teachers. It was also intended to seek whether ELT education brings about any changes in learners’ perceptions of autonomy. For this reason, one group of first year and one group of fourth year ELT students were selected as the subjects of the study in Anadolu University with the purpose of making a comparison between their perceptions. Questionnaires and interviews were used as the data collecting instruments of the study. The results showed that participants as learners of English appeared to be ready for autonomous learning in some areas while they needed to be guided and backed up in other aspects of learning. As future teachers of English, they had positive attitudes towards learner autonomy. Another result of the study was that there were no notable differences between first and fourth year students’ perceptions of learner autonomy.

Özdere’s (2005) study intended to discover English instructors’ attitudes towards learner autonomy. 72 English instructors working in six different state-supported provincial universities in Turkey participated in this study. The main data collecting instrument of the study was a questionnaire including Likert-scale statements. In addition, 10 participants were interviewed. The results indicated that participants’ attitudes towards learner autonomy varied from neutral to mildly positive depending on the facilities and opportunities provided by their universities for their instructional environments. In addition, it was emphasized that the promotion of learner autonomy in those universities could be backed up through inservice training and systematic adaptations in the curricula (Özdere, 2005).

The review of literature indicates that autonomous learning is indispensable for effective language learning which will enable language learners to develop more responsibilities for their own learning. Therefore, most of the relevant research studies highlight the importance of promoting learner autonomy in language classrooms. The question of how to foster learner autonomy generally finds an answer in learner training in the literature. Learners are trained on language learning strategies to foster their autonomy level.

14

Language Learning Strategies

The literature on learning strategies in second language acquisition emerged from a concern for identifying the characteristics of effective learners. Wenden (1991: 5) states that “successful or intelligent learners acquire the learning and the attitudes that enable them to use their skills and knowledge confidently, flexibly and appropriately”. They find a style of learning that suits them, are actively involved in language learning process, try to figure out how language works, and know that language is used to communicate. They are also like good detectives, always looking for clues to understand better. They learn to think in the language and realize that it is not easy, are aware of the close relationship between language and culture and have a long term commitment to learning. Similarly, Oxford (1990) defines successful learners as the ones who have insight into their own learning, language learning styles, and preferences as well as the task. Successful learners take an active approach to learning tasks. They are willing to take risks, are good guessers of context, situation, explanation, error or translation and are prepared to attend to form as well as to content. They attempt to develop the target language into a separate reference system and try to think in the target language. They generally have a tolerant and outgoing approach to the target language.

Since successful learners are conscious learners who take responsibility for their learning by having control over it, they are also called self-regulated learners. The learners who are identified as self- regulated or successful learners in literature may also be defined as autonomous learners since the features used to label both concepts seem to overlap. Self-regulated language learners know how to engage themselves actively in their language learning process by using language learning strategies. Oxford& Ehrman (1990) define strategies as “behaviors or actions which learners use to make language learning more successful, self-directed and enjoyable” (p. 1). If a learner wants to be successful, he or she takes the responsibility for his or her learning process and employs language learning strategies.

The literature on learning strategies have focused on universal language processing strategies, such as overgeneralization, transfer and simplification and one cause of learner

15

errors and the changing nature of the learners’ interlanguage system was considered to be the operation of these strategies (Taylor, 1975; Richards, 1975; cited in Wenden& Rubin, 1987). Analysis of learner language has also yielded information on communication strategies learners use when faced with a gap between communicative need and linguistic repertoire (Faerch& Kasper, 1983). These studies on universal language processing strategies and communication strategies focus on the cognitive processes involved in second language acquisition.

How learners approach the task of learning a second language is the subject of cognitive science defined as “a systematic inquiry into our thinking selves… a discipline devoted to exploring how our minds work (Hunt, 1982; 17 cited in Wenden& Rubin, 1987). The understanding of the workings of the mind is expressed in a variety of questions (Hunt, 1982; 29 cited in Wenden& Rubin, 1987), these questions are;

Do we learn what we learn primarily as a result of mere repetition- or of comprehension- or of the linkage of new material to previously known material? By what methods do we locate, in our memories, whatever we want to remember? Has what is forgotten merely faded out, or been erased or merely misfiled?

Does the human mind spontaneously come to reason along the lines of formal logic or does it, instead, have a quite different natural logic of its own?

What do we do that enables us to see, at some point, that certain things can be grouped into a coherent category, or that a general rule can be extracted from a series of experiences?

Do we learn to imitate grammatical speech as we grow up ora re grammatical structures genetically prewired in the brain’s language area?

What are the processes we use consciously or unconsciously when solving problems both great and small and can the individual’s problem solving ability be improved by training?

What do highly creative people do that ordinary people don’t do?

What kinds of thinking go on unconsciously, as contrasted to those kinds that are conscious?

16

How is our thinking affected or skewed by our sex, age, personality, and background?

Cognitive science bases its assumptions on these questions. Information comes in through our sense receptors. At this time selected items of information are attended to, identified, and, then, moved into the short-term or working memory. In short-term memory a series of mental operations are applied to this information. Then, the changed or modified product is stored in long-term memory to be retrieved when it is needed. The mental operations that encoded incoming information are referred to as processes. The changes brought about by these processes are referred to as organizations of knowledge or knowledge structures. The techniques actually used to manipulate the incoming information and, later, to retrieve what has been stored are referred to as cognitive strategies (Wenden& Rubin, 1987).

Research focusing on the “good language learner” (Naiman et. al. 1978; Rubin, 1975; cited in Wenden& Rubin, 1987) had identified strategies reported by students or observed in the language learning situations that appear to contribute to learning. Ellis (1994) depicts language learning strategies as both general approaches and specific actions or techniques used to learn a second language. Strategies are problem oriented and learners are generally aware of them. They involve both linguistic and non-linguistic behaviors. They can be performed both in one’s native language and second language. Some strategies are behavioral and directly observable, while others are mental and not directly observable. They contribute directly or indirectly to learning. Strategy use varies in response to task type and individual learner preferences.

Language learners employ strategies; however, they vary in their choice of strategies. Ellis (1994) defines some factors that affect the strategy choice of learners. Learners’ beliefs about language learning affect strategy choice. Ellis (1994) states that learners who emphasize the importance of learning tend to use cognitive strategies (direct strategies), while the ones who emphasize the importance of using the language rely on communication strategies (indirect strategies). Learner factors such as age, aptitude, motivation, personal background, and gender also affect strategy choice. Ellis (1994) states that young children employ strategies in task-specific manners, while older children and

17

adults make use of generalized strategies. Aptitude, related to learning styles, also affects strategy choice.

Oxford and Ehrman (1990) suggest that introverts, intuitives, feelers, and perceivers have advantages in classroom contexts because they have more aptitude for language learning and use more strategies. Ellis (1994) suggests that highly motivated students use more strategies related to formal practice, functional practice, general study, conversation, and input elicitation than poorly motivated students. Learning experiences also affect strategy choice; students with at least five years of study use more functional-practice strategies than students with fewer years of experiences (Ellis, 1994). The nature and range of the instructional task affect strategy choice and use as well. Learning languages that are totally different from learners’ native language may result in greater use of strategies than learning similar ones (Ellis, 1994).

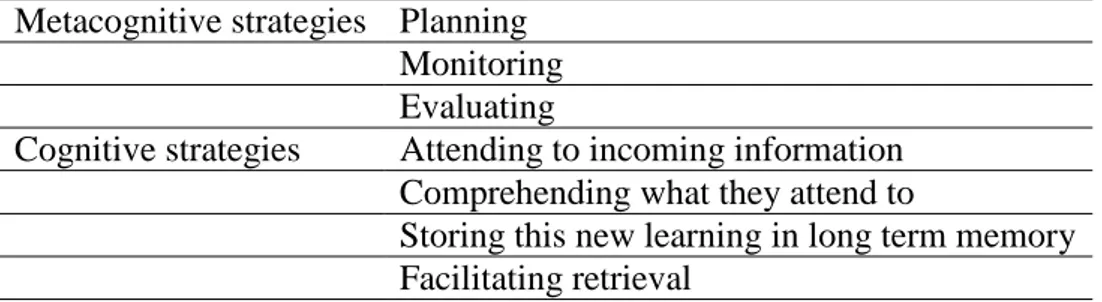

The literature showed that students do apply strategies while learning a second language and that these strategies can be described and classified. Rubin (1981: cited in Wenden& Rubin, 1987) was the first researcher to classify learning strategies in second language acquisition. The taxonomies of language learning strategies in literature are given as follows starting with Wenden (1991):

Table 1 Wenden’s Taxonomy of Language Learning Strategies (1998) Metacognitive strategies Planning

Monitoring Evaluating

Cognitive strategies Attending to incoming information Comprehending what they attend to

Storing this new learning in long term memory Facilitating retrieval

18

Rubin classifies the strategies based on direct or indirect effect on learning: Table 2 Rubin’s Taxonomy of Language Learning Strategies (1981)

Strategies that

directly affect

learning

Clarification/ verification

Asks for an example of how to use a word or expression, repeats words to confirm understanding

Monitoring Corrects errors in own/ other’s

pronunciation, vocabulary, spelling, grammar, style

Memorization Takes notes of new items, pronounces out loud, finds a mnemonic, writes items repeatedly

Guessing/ inductive inferencing

Guesses meaning from key words,

structures, pictures, context, etc.

Deductive reasoning Compares native/ other language to target language

Groups words

Looks for rules of co-occurrence

Practice Experiments with new sounds

Repeats sentences until pronounced easily Listens carefully and tries to imitate Processes that contribute indirectly to learning Creates opportunities for practice

Creates situation with native speaker

Initiates conversation with fellow students Spends time in language lab, listening to TV, etc.

Production tricks Uses circumlocutions, synınyms, or cognates

Uses formulaic interaction

19

Naiman et. al (1978) classifies language learning strategies into four parts: Table 3 Naiman et. al.’s Taxonomy of Language Learning Strategies (1978) Active task approach Responds positively to

learning opportunity or seeks and exploits learning environments

Student acknowledges need for a structured learning environment and takes a course prior to immersing him/ herself in target language

Adds related language learning activities to regular classroom program

Reads additional items

Listens to tapes

Practices Writes down words to memorize

Looks at speakers’ mouth and repeats

Analyzes individual problems

Reads alone to hear sounds Makes use of fact that

language is a system

Relates new dictionary words to others in same category

Realization of language as a means of

communication and interaction

Emphasizes fluency over accuracy

Does not hesitate to speak

Uses circumlocutions Seeks communicative

situations with L2 speakers

Communicates whenever possible Establishes close personal contact with L2 native speakers

Writes to pen pals

Finds sociocultural

meanings

Memorizes courtesies and phrases Management of

affective demands

Copes with affective

demands in learning

Overcomes inhibition to speak Is able to laugh at own mistakes Is prepared for difficulties

Monitoring L2

performance

Constantly revises L2

system by testing

inferences and asking L2

native speakers for

feedback

Generates sentences and looks for reactions

Looks for ways to improve so as not to repeat mistakes

20

Stern (1992) has taxonomy similar to Naiman et. al. (1978):

Table 4 Stern’s Taxonomy of Language Learning Strategies (1992: 262- 266)

Management and

Planning Strategies

Related with the learner's intention to direct his own learning

Decide what commitment to make to language learning

Set oneself reasonable goals

Decide on an appropriate

methodology, select appropriate resources, and

monitor progress

Evaluate one’s achievement in the light of previously determined goals and

expectations Cognitive Strategies Steps or operations used in

learning or problem

solving that require direct analysis, transformation, or

synthesis of learning

materials

Clarification / verification

Guessing / inductive inferencing Deductive reasoning Practice Memorization Monitoring Communicative -Experiential Strategies

avoid interrupting the flow of communication

Circumlocution

Gesturing

Paraphrase or asking for repetition Explanation

Interpersonal Strategies

Monitor their own

development and

evaluate their own

performance

Contact with native speakers and cooperate with them. Learners must become acquainted with the target culture

Become acquainted with the target culture

21

O’Malley and Chamot (1990) classify language learning strategies into three types as shown below:

Table 5 O’Malley & Chamot’s Taxonomy of Language Learning Strategies (1990) Generic strategy classification Representative Strategies Definitions Metacognitive strategies

Selective attention Focusing on special aspects of learning tasks, as in planning to listen for key words or phrases Planning Planning or the organization of either written or

spoken discourse

Monitoring Reviewing attention to a task, comprehension of information that should be remembered, or production while it is occurring

Evaluation Checking comprehension after completion of a receptive language activity, or evaluating language production after it has taken place Cognitive

strategies

Rehearsal Repeating the names of items or objects to be remembered

Organization Grouping and classifying words, terminology or concepts according to their semantic or syntactic attributes

Inferencing Using information in text to guess meanings of new linguistic items, predict outcomes, or complete missing parts

Summarizing Intermittently synthesizing what one has heard to ensure the information has been retained

Deducing Applying rules to the understanding of language

Imagery Using visual images to understand and remember

new verbal information

Transfer Using known linguistic information to facilitate a new learning task

Elaboration Linking ideas contained in new information or integrating new ideas with known information Social/ affective

strategies

Cooperation Working with peers to solve a problem, pool information, check notes or get feedback on a learning activity

Questioning for clarification

Eliciting from a teacher or peer additional explanation, rephrasing or examples

Self- talk Using mental redirection of thinking to assure oneself that a learning activity will be successful or reduce anxiety about a task

22

Oxford (1990) classifies language learning strategies into two types: direct and indirect language learning strategies, depending on the direct or indirect use of language.

Table 6 Oxford’s Taxonomy of Direct Language Learning Strategies (1990) I. Memory strategies A. Creating mental

images

1.Grouping: classifying or

reclassifying what is heard or said into meaningful groups to reduce the number of unrelated elements such as pronouns, adjectives, etc.

2. Associating/ elaborating:

associating new language

information with familiar concepts already in memory.

3. Placing new words into a context: placing new words or expressions that have been heard or read into a meaningful context, such as a spoken or written sentence to remember. B. Applying images and

sounds

1. Using imagery: creating a mental image.

2. Semantic mapping: arranging concepts and relationships in which the key concepts are highlighted and linked with related concepts.

3. Using keywords: combining sounds and images so that learners can more easily remember what they hear or read in the new language. 4. Representing sounds in memory: remember what you hear by making

auditory rather than visual

representations of sounds.

C. Reviewing well 1. Structured reviewing: reviewing at different intervals.

D. Employing action 1.Using physical response or

sensation: acting out a new expression that has been heard physically.

2. Using mechanical techniques: contextualizing a new expression and get writing practice.

23

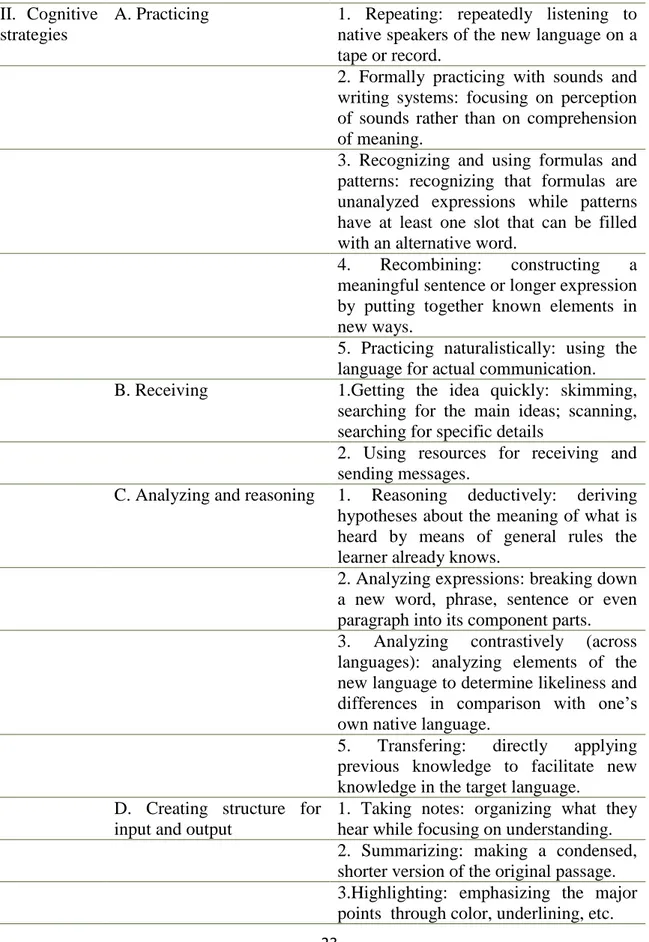

Table 6 Oxford’s Taxonomy of Direct Language Learning Strategies (1990) (continued) II. Cognitive

strategies

A. Practicing 1. Repeating: repeatedly listening to

native speakers of the new language on a tape or record.

2. Formally practicing with sounds and writing systems: focusing on perception of sounds rather than on comprehension of meaning.

3. Recognizing and using formulas and patterns: recognizing that formulas are unanalyzed expressions while patterns have at least one slot that can be filled with an alternative word.

4. Recombining: constructing a

meaningful sentence or longer expression by putting together known elements in new ways.

5. Practicing naturalistically: using the language for actual communication.

B. Receiving 1.Getting the idea quickly: skimming,

searching for the main ideas; scanning, searching for specific details

2. Using resources for receiving and sending messages.

C. Analyzing and reasoning 1. Reasoning deductively: deriving hypotheses about the meaning of what is heard by means of general rules the learner already knows.

2. Analyzing expressions: breaking down a new word, phrase, sentence or even paragraph into its component parts. 3. Analyzing contrastively (across languages): analyzing elements of the new language to determine likeliness and differences in comparison with one’s own native language.

5. Transfering: directly applying previous knowledge to facilitate new knowledge in the target language.

D. Creating structure for input and output

1. Taking notes: organizing what they hear while focusing on understanding. 2. Summarizing: making a condensed, shorter version of the original passage. 3.Highlighting: emphasizing the major points through color, underlining, etc.

24

Table 6 Oxford’s Taxonomy of Direct Language Learning Strategies (1990) (continued) III. Compensation

strategies

A. Guessing intelligently 1. Using linguistic clues: using linguistic clues provided by gained knowledge of target language, the learners’ own language.

2. Using other clues: such as forms of address, audible or visual clues, general background knowledge.

B. Overcoming

limitations in speaking and writing

1. Switching to the mother tongue: using the mother tongue for an expression without translating it. 2. Getting help: asking someone for help in a conversation by hesitating or explicitly asking for the missing expression.

3. Using mime or gesture: in place of an expression during a conversation to indicate the meaning.

4. Avoiding communication partially or totally: when difficulties are anticipated or encountered.

5. Selecting the topic: choosing the topic of interest or the topic for which they have the required vocabulary and structures.

6. Adjusting or approximating the message: altering the message by omitting some items of information. 7. Coining words: making up new words to communicate a concept for which the learner doesn’t have the right vocabulary.

8. Using a circumlocution or synonym: using a circumlocution/ a roundabout expression involving several words to describe or a synonym to convey the intended meaning.

25

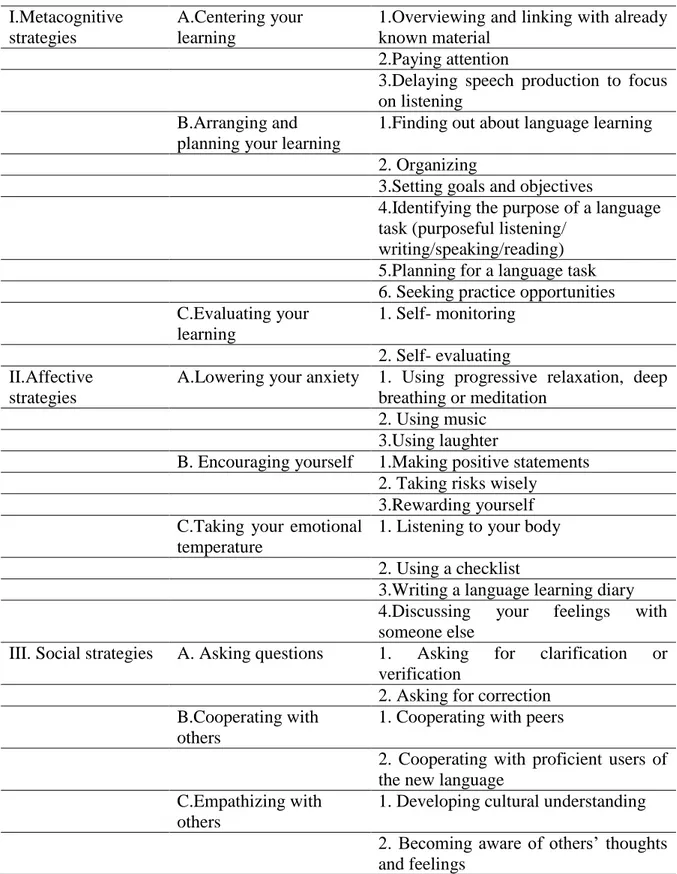

Table 7 Oxford’s Taxonomy of Indirect Language Learning Strategies (1990) I.Metacognitive

strategies

A.Centering your learning

1.Overviewing and linking with already known material

2.Paying attention

3.Delaying speech production to focus on listening

B.Arranging and planning your learning

1.Finding out about language learning 2. Organizing

3.Setting goals and objectives

4.Identifying the purpose of a language task (purposeful listening/

writing/speaking/reading) 5.Planning for a language task 6. Seeking practice opportunities C.Evaluating your learning 1. Self- monitoring 2. Self- evaluating II.Affective strategies

A.Lowering your anxiety 1. Using progressive relaxation, deep breathing or meditation

2. Using music 3.Using laughter

B. Encouraging yourself 1.Making positive statements 2. Taking risks wisely

3.Rewarding yourself C.Taking your emotional

temperature

1. Listening to your body 2. Using a checklist

3.Writing a language learning diary 4.Discussing your feelings with someone else

III. Social strategies A. Asking questions 1. Asking for clarification or verification

2. Asking for correction B.Cooperating with

others

1. Cooperating with peers

2. Cooperating with proficient users of the new language

C.Empathizing with others

1. Developing cultural understanding 2. Becoming aware of others’ thoughts and feelings

26

Language Learning Strategies Studies Conducted in Turkey

One of the first studies that concentrated on the relationship between language learning strategy use and EFL proficiency was carried out by Aslan (2009) who investigated the link between strategy use and success levels, the difference in strategy use between genders and its influence on their achievement in English. According to the findings of the study, the use of language learning strategies were positively related to success in English, females were significantly more successful than males in terms of achievement tests and they used more language learning strategies in learning English. According to the statistical results, it was concluded that there is a significant connection between gender, language learning strategies and achievement in English.

Karatay (2006) conducted a study so as to find the language learning strategies that are most frequently used by adult Turkish students. Three strategies which are a) I try to find out how to be a better learner of English b) If I do not understand something in English, I ask the other person to slow down or say it again and c) I pay attention when someone is speaking English were found to be the most frequently used by the adult Turkish students within the scope of the study.

Algan (2006) explored language learning strategies employed by adult Turkish university preparation class students and their instructors‘awareness of the strategy use of these learners. It was found that all the six universities which participated in the study had average scores of strategy use which indicated a ―medium level of (between 2.5 and 3.4) usage. Almost all students reported using compensation and metacognitive strategies more than memory and affective strategies. The results also revealed that the level of awareness of the participating English language instructors on the usage of language learning strategies by their EFL students was low, since the general awareness of the teachers on the topic of language learning strategies was not high.

Aydemir (2007) aimed to find out the effect of training students on vocabulary learning strategies. In his study, he had control and experimental groups. He found the level of the students with pre-tests and found out that there was no significant difference between the

27

groups. After the training process, he conducted the test again to see whether any significant difference has occurred or not. The results showed that the group who had the training was statistically successful; therefore, he concluded that training students on vocabulary strategies had a positive impact on the vocabulary knowledge of students. Gökgöz (2008) studied language learning strategy use of preparatory school students at Istanbul Technical University. In order to explore students‘language learning strategy use, an adapted version of the English Language Learning Strategy Inventory (Griffiths, 2003) was used. Also, with the purpose of gaining a more precise picture of learning strategy use among the students, email interviews were conducted. By considering the need for understanding the role of strategies in English language learning and its relation to students‘success, the study aimed to investigate the frequency with which students use language learning strategies and how it is related to students’ achievement at school using the results of the questionnaire, email interviews and proficiency test scores.

Firstly, the overall language learning strategy use of preparatory students at Istanbul Technical University was found to be at medium level (average=2.9, as defined by Oxford, 1990). The most frequently used strategies were ―I use a dictionary to check the meanings of words, ―I watch movies in English and ―I listen to songs in English with an overall average rate of 4.2. Secondly, no significant correlation between language learning strategy use and students‘proficiency level was found. Students at elementary and intermediate group reported equal frequency of overall language learning strategy use with a rate of 2.9 which was very slightly higher than the frequency of strategy use of pre-intermediate group which was 2.8. Thirdly, the study could not find a significant relation between average overall language learning strategy use and overall achievement of students. However, according to the results, a group of four strategies had a significant positive correlation with successful exam results, accounting for nearly 10% of the variance.

Cesur (2008) explored the relationship between university prep class students’ language learning strategies, and language academic success. The results demonstrated that the Turkish university preparatory students use compensation strategies and then metacognitive strategies most frequently, followed by memory, cognitive, social and affective strategies. It was also found that females used strategies significantly more than