COHERENCE AND EFFECTIVENESS OF EU FOREIGN

POLICY: THE CASES OF BOSNIA AND

HERZEGOVINA, AND KOSOVO

A Ph.D. Dissertation

by

DENİZ MUTLUER

Department of

International Relations

İhsan Doğramacı Bilkent University

Ankara

November 2018

DE NI Z M UT L UE R CO H E RE N CE A N D E FF E CT IV EN ES S OF E U F O R E IG N P O L IC Y B ilke nt U ni ve rsi ty 2018COHERENCE AND EFFECTIVENESS OF EU FOREIGN POLICY:

THE CASES OF BOSNIA AND HERZEGOVINA, AND KOSOVO

The Graduate School of Economics and Social Sciences

of

İhsan Doğramacı Bilkent University

by

DENİZ MUTLUER

In Partial Fulfilment of the Requirements for the Degree of

DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY

in

THE DEPARTMENT OF

INTERNATIONAL RELATIONS

İHSAN DOĞRAMACI BILKENT UNIVERSITY

ANKARA

ABSTRACT

COHERENCE AND EFFECTIVENESS OF EU FOREIGN POLICY:

THE CASES OF BOSNIA AND HERZEGOVINA, AND KOSOVO

Mutluer, Deniz

Ph.D. Department of International Relations

Supervisor: Assoc. Prof. Dr. Dimitris Tsarouhas

November 2018

This thesis aims to analyse the coherence and effectiveness of the European Union (EU) foreign policy by focusing on two crucial cases that shaped the emergence of the Common Foreign and Security Policy (CFSP) of the Union: Bosnia and Herzegovina, and Kosovo. Has the EU foreign policy been coherent and effective in Bosnia and Kosovo? The concept of “coherence” has high explanatory power to analyse the relationship between the EU institutions, the EU member states, and the EU foreign policy instruments. Accordingly, this research examines the coherence of EU foreign policy instruments used in Bosnia and Kosovo by developing a new analytical concept: “perceived coherence” which focuses on the degree of receptivity amongst local agents regarding the coherence of EU policy instruments applied in their country, namely the EU accession process, the CSDP missions and mediation. After analysing the coherence of the EU foreign policy in Bosnia and Kosovo, this study focuses on the factors that come into play between coherence and effectiveness.

Keywords: EU foreign policy, policy coherence, policy effectiveness, Bosnia and Herzegovina, Kosovo.

ÖZET

AVRUPA BIRLİĞİ DIŞ POLİTİKASININ TUTARLILIĞI VE

ETKİNLİĞİ: BOSNA HERSEK VE KOSOVA VAKA

INCELEMELERİ

Mutluer, Deniz

Doktora, Uluslararası İlişkiler Bölümü

Tez Yöneticisi: Doç. Dr. Dimitris Tsarouhas

Kasım 2018

Bu tez, Avrupa Birliği’nin (AB) dış politikasının tutarlılığını ve etkinliğini, AB’nin Ortak Dış ve Güvenlik Politikası’nın (ODGP) doğmasında kritik bir rol oynayan, Bosna Hersek ve Kosova vakalarını ele alarak incelemektedir. AB dış politikası, Bosna Hersek ve Kosova'da tutarlı ve etkili oldu mu? “Tutarlılık” kavramı, AB kurumları, AB üye ülkeleri ve AB dış politika araçları arasındaki ilişkiyi incelemek için en uygun kavramların başında gelmektedir. Bu araştırma, Bosna Hersek ile Kosova'da kullanılan AB dış politika araçlarını, yeni bir kavram olan “algılanan tutarlılık” kavramını kullanarak analiz etmektedir. Algılanan tutarlılık kavramı, AB’nin üçüncü ülkelerde uyguladığı dış politika araçlarını, yerel aktörlerin bakış acısıyla ele almaktadır. Bu tez ayrıca, tutarlılık ve etkinlik arasında “doğrusal” bir ilişki olup olmadığını inceleyerek, tutarlılık ve etkinlik süreci arasında ortaya çıkan faktörler üzerine odaklanmaktadır.

Anahtar Kelimeler: AB dış politikası, politika tutarlılığı, politika etkinliği, Bosna Hersek, Kosova.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

I would like to start by expressing my deepest gratitude to my supervisor Assoc. Prof. Dr. Dimitris Tsarouhas for guiding me patiently during the whole writing process of this research. I will never forget his incredibly valuable support and encouragement. I would also like to express my sincere gratitude to my thesis committee members Assoc. Prof. Dr. Sevilay Kahraman, Assist. Prof Dr. Onur Işçi, Assist. Prof Dr. Berk Esen and Assoc. Prof. Dr. Zeynep Arkan.

I also would like to thank Prof. Dr. Jan Orbie from Ghent University for his help during the research period I spent in Belgium. I also want to express my sincere gratitude to Krenar Gashi, for putting me in contact with numerous civil society members in the Western Balkan region.

Finally, I would like to thank all of my friends and mostly my parents, my sister and my dear wife Julia for their never-ending support, patience, and love. There are no words to describe my gratefulness for their support.

TABLE OF CONTENTS

ABSTRACT ... III ÖZET ... IV ACKNOWLEDGMENTS ... IV TABLE OF CONTENTS ... VI LIST OF TABLES... IX LIST OF FIGURES ... XI CHAPTER I: INTRODUCTION ... 1 1.1THEORETICAL FRAMEWORK... 2 1.1.1 Defining coherence ... 2 1.1.2 Types of coherence... 3 1.1.3 Degrees of coherence ... 6 1.1.4 Coherence-effectiveness relationship ... 71.1.5 How to define and measure effectiveness of the EU’s Foreign Policy? ... 8

1.1.6 Contribution to the existing literature ... 10

1.2METHODOLOGY ... 12

1.2.1 Research Questions ... 12

1.2.2 Usage of the comparative case study method ... 12

1.2.3 Reasons for case selection ... 13

1.2.4 Methods and sources to be used ... 16

1.2.5 Limitations of the study ... 17

CHAPTER II: ANALYSING EUROPEAN FOREIGN POLICY: A LITERATURE REVIEW ... 18

2.1INTRODUCTION ... 18

2.2LITERATURE ON THE FORMAL GOVERNANCE IN THE EUFOREIGN POLICY ... 20

2.2.1 Literature on the Evolution of European Foreign Policy ... 21

2.2.2 The Emergence of the Common Foreign and Security Policy ... 24

2.2.3 “What Type of Power the EU is?” ... 26

2.2.4 Strategic Culture and the European Foreign Policy ... 29

2.2.5 The Concept of “Actorness” and the EU Foreign Policy ... 31

2.2.6 Emerging new European Foreign Policy actors: the EEAS and the HR/VP ... 33

2.2.6.1 Principal-Agent Theory and the EEAS and the HR/VP ... 40

2.2.6.2 Literature on the impact of the EEAS and the HR/VP on improving the coherence of the Union’s external action ... 41

2.2.6.3 Literature on the Record of the EEAS in International Crises ... 44

2.3LITERATURE ON INFORMAL GOVERNANCE IN EUFOREIGN POLICY ... 46

2.3.1 Literature on the Relationship between the EU and Local Actors ... 51

CHAPTER III: EU FOREIGN POLICY COHERENCE AND EFFECTIVENESS IN BOSNIA ... 53

3.1THE EMERGENCE OF EUFOREIGN POLICY IN BOSNIA ... 54

3.1.1 War in Bosnia: EU’s first major foreign policy test ... 55

3.1.2 Dayton Agreement and its impact on the EU foreign policy in Bosnia .... 56

3.1.3 EU-Bosnia relations after Dayton: first steps towards Europeanization ... 59

3.1.4 Stabilization and Association Process (SAP) ... 60

3.2EUCONDITIONALITY AS FOREIGN POLICY IN BOSNIA ... 61

3.2.1 Conditionality Process in Bosnia ... 61

3.2.2 EU actors’ role in the EU Foreign Policy in Bosnia ... 65

3.2.3 Coherence of the Union during the EU Police Mission (EUPM) in Bosnia ... 67

3.2.3.1 Background of the initiation and the evolution of the EUPM ... 68

3.2.3.2 Institutional coherence of the EU during the EUPM... 71

3.2.3.3 Horizontal coherence of the EU during the EUPM ... 75

3.2.3.4 Vertical Coherence of the EU during the EUPM ... 76

3.2.3.5 Perceived coherence during the EUPM ... 77

3.2.4 Constitutional reform: a vague, abandoned “so-called precondition” for EU integration of Bosnia ... 80

3.2.4.1 Background and Failure of the Constitutional Reform ... 81

3.2.4.2 Institutional Coherence of the EU during the Constitutional Reform 86 3.2.4.3 Horizontal coherence during the constitutional reform ... 88

3.2.4.4 Vertical coherence of the EU during the constitutional reform ... 91

3.2.4.5 Perceived coherence of the EU during constitutional reform ... 93

3.2.5 Evaluation of the EU Conditionality Process in Bosnia ... 95

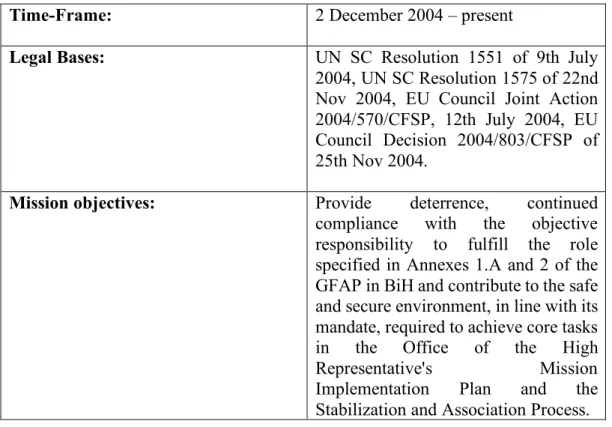

3.3EUMILITARY MISSION AS FOREIGN POLICY:EUFORALTHEA ... 102

3.3.1 Background and the initiation of the mission EUFOR Althea ... 102

3.3.2 Institutional coherence during EUFOR Althea ... 105

3.3.3 Horizontal coherence during EUFOR Althea ... 111

3.3.4 Vertical coherence during EUFOR Althea ... 112

3.3.5 Perceived coherence and EUFOR Althea ... 115

3.4THE IMPACT OF THE CREATION OF THE HR/VP AND THE EEAS ON THE EU’S FOREIGN POLICY COHERENCE IN BOSNIA... 116

3.5EFFECTIVENESS OF EUFOREIGN POLICY IN BOSNIA ... 121

3.5.1 Effectiveness of EUPM ... 121

3.5.2 Effectiveness of constitutional reform ... 125

3.6THE REFORM AGENDA:2015-2018, A NEW IMPETUS FOR EU-BOSNIA

RELATIONS ... 129

3.6.1 The Background and the adoption of the Reform Agenda ... 129

3.6.2 Evaluating the Reform Agenda ... 132

3.7CONCLUDING REMARKS ... 137

CHAPTER IV: EU FOREIGN POLICY COHERENCE AND EFFECTIVENESS IN KOSOVO ... 138

4.1THE EMERGENCE OF EUFOREIGN POLICY IN KOSOVO ... 139

4.1.1 Background to the Kosovo problem... 139

4.1.2 EU becoming a foreign policy actor in Kosovo... 142

4.1.3 Road to the unilaterally declared independence of Kosovo ... 144

4.2.INTRODUCING THE EU FOREIGN POLICY INSTRUMENTS IN KOSOVO ... 145

4.2.1 EU actors’ role in the EU Foreign Policy in Kosovo ... 148

4.3EUACCESSION AS FOREIGN POLICY IN KOSOVO ... 150

4.3.1 Institutional Coherence of the EU regarding the EU accession process of Kosovo ... 150

4.3.1.1 The Stabilization and Association Process and the Visa Liberalization ... 152

4.3.2 Horizontal Coherence of the EU regarding the EU accession process of Kosovo ... 157

4.3.3 Vertical Coherence of the EU regarding the EU accession process of Kosovo ... 158

4.3.4 Perceived coherence regarding the EU Accession Process of Kosovo ... 161

4.4COHERENCE OF THE EU AND EULEX: THE CSDPRULE OF LAW MISSION ... 166

4.4.1 Background and the initiation of EULEX Kosovo ... 166

4.4.2 EULEX and institutional coherence of the EU ... 169

4.4.3 EULEX and Horizontal Coherence of the EU ... 171

4.4.4 EULEX and vertical coherence of the EU ... 172

4.4.5 EULEX and perceived coherence of the Union ... 174

4.5BELGRADE-PRISTINA DIALOGUE:TESTING THE IMPACT OF THE HR/VP AND THE EEAS ON THE EUFOREIGN POLICY COHERENCE ... 177

4.5.1 Background to Belgrade-Pristina dialogue ... 178

4.5.2 Belgrade-Pristina Dialogue and the Institutional Coherence of the EU .. 181

4.5.3 Belgrade-Pristina Dialogue and Horizontal Coherence of the EU ... 183

4.5.4 Belgrade-Pristina Dialogue and Vertical Coherence of the EU... 185

4.5.5 Perceived Coherence During the Belgrade-Pristina Dialogue ... 186

4.6EFFECTIVENESS OF EUFOREIGN POLICY IN KOSOVO ... 189

4.6.1 EU foreign policy effectiveness regarding the EU accession process of Kosovo ... 189

4.6.2 EULEX and the effectiveness of the EU ... 192

4.6.3 Effectiveness of Belgrade-Pristina Dialogue ... 197

4.7CONCLUDING REMARKS ... 199

5.1COHERENCE OF EUFOREIGN IN BOSNIA AND KOSOVO ... 202

5.1.1 Institutional coherence Bosnia and Kosovo ... 204

5.1.2 Horizontal Coherence in Bosnia and Kosovo ... 206

5.1.3 Vertical Coherence in Bosnia and Kosovo ... 208

5.1.4 Perceived Coherence of the EUFP in Bosnia and Kosovo ... 209

5.2EFFECTIVENESS OF EUFOREIGN POLICY IN BOSNIA AND KOSOVO ... 212

5.3.THE RELATIONSHIP BETWEEN COHERENCE AND EFFECTIVENESS REGARDING THE EUFOREIGN POLICY IN BOSNIA AND KOSOVO ... 217

5.3.1 The trade-off between coherence and effectiveness ... 218

5.3.1.1 Internal coherence, perceived coherence and effectiveness ... 219

CHAPTER VI: CONCLUSION ... 226

6.1THESIS STATEMENT AND HYPOTHESIS ... 226

6.2EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ... 227

6.3MAIN FINDINGS ... 228

6.4THE STATE OF PLAY ... 232

6.5POLICY RECOMMENDATIONS ... 236

6.6IMPLICATIONS FOR FUTURE RESEARCH ... 239

REFERENCES ... 240

APPENDICES ... 283

APPENDIX A:MAP OF BOSNIA AND HERZEGOVINA ... 283

APPENDIX B:PEOPLE AND SOCIETY IN BOSNIA AND HERZEGOVINA ... 284

APPENDIX C:KOSOVO FACTS: ... 285

ANNEX D:INFORMATION ON LOCAL GOVERNANCE:NATIONS IN TRANSIT RATINGS AND AVERAGED SCORES FOR KOSOVO ... 286

LIST OF TABLES

TABLE 1 FRAMEWORK FOR ANALYSING EU FOREIGN POLICY

COHERENCE ... 7

TABLE 2 MISSION OVERVIEW – EUFOR ALTHEA EUFOR ALTHEA (IN BOSNIA AND HERZEGOVINA) ... 108

TABLE 3 EU FOREIGN POLICY COHERENCE IN BOSNIA ... 203

TABLE 4 EU FOREIGN POLICY COHERENCE IN KOSOVO ... 204

TABLE 5 EU FOREIGN POLICY EFFECTIVENESS IN KOSOVO... 212

LIST OF FIGURES

CHAPTER I

INTRODUCTION

From its inception onwards, European Foreign Policy (EFP) has been shaped by institutional reforms aiming to improve the coherence and effectiveness of the Union’s external policies. Notably, the Treaty on the European Union (TEU) states that “the Union shall have an institutional framework which shall […] ensure the consistency, effectiveness and continuity of its policies and actions”.1 With the changes of the Lisbon Treaty and the creation of new institutional actors such as the External Action Service (EEAS) and the appointment of the High Representative and Vice President (HR/VP), the EU decision and policy makers aimed to transform the Union into a more coherent and effective foreign policy actor.2 This dissertation seeks to analyse the

coherence and effectiveness of the EU foreign policy by focusing on two crucial cases that shaped the emergence of a Common Foreign and Security Policy of the Union: Bosnia and Herzegovina (hereafter Bosnia or BiH), and Kosovo. Has the EU foreign policy been coherent and effective in Bosnia and Kosovo?

By developing the new analytical concept of “perceived coherence”, which focuses on the degree receptivity amongst local agents regarding the coherence of EU foreign policy instruments applied in their country, this thesis analyses the link between the

1See Treaty on the European Union (TEU, Art. 13(1)) 2SeeTreaty on the European Union (TEU Art. 27)

internal3 and perceived coherence of the Union’s foreign policy in Bosnia and Kosovo.

After having analysed the impact of the internal coherence of the EU on the perceived coherence of local actors in Bosnia and Kosovo, this study will focus on the effectiveness of the EU foreign policy in these two cases, by analysing the factors that come into play between coherence and effectiveness. While analysing the internal and perceived coherence of the EU, this research will also focus on whether the “new” EU institutional actors introduced with the Lisbon Treaty, such as the European External Action Service (EEAS) and the High Representative and Vice President of the Commission (HR/VP) have improved the foreign policy coherence of the Union in its relations with Bosnia and Kosovo.

This thesis argues that the EU foreign policy instruments of the EU used in Bosnia Kosovo, has been perceived as incoherent by the local agents, namely by the local political elites and civil society organizations. As a consequence, the EU foreign policy remains ineffective. This research contends that the EU should focus more on the local dynamics affecting the effective implementation of its foreign policy instruments rather than focusing solely on improving its own institutional architecture.

The first section of this introductory chapter will focus on the theoretical framework that is used to analyse the foreign policy coherence and effectiveness of the EU foreign policy in Bosnia and Kosovo. The second part will focus on the methodology by denoting the research questions, the methods and sources used, and the limitations of the study.

1.1 Theoretical framework

1.1.1 Defining coherence

How can we define “coherence”? How can coherence be evaluated? What is the relationship between coherence and effectiveness? The first part of this chapter focuses on these questions.

3 Internal coherence denotes the coherence between the EU institutions, EU policies and EU member states.

Coherence is an ambiguous concept to analyse. Abellan and Medina (2002: 3) defined coherence as the act of staying together and remaining united in ideas. In a similar fashion Antonio Missiroli (2001: 182) contended that coherence is the degree of synergy for an actor. Legal EU scholars such as Hillion (2008: 17) defined the concept as the lack of legal contradictions between various policies and the “quest for synergy” between the EU policies. Bretherton and Vogler (2006: 30) defined coherence as “the level of internal coordination of EU policies” and consistency as “the degree of congruence between the external policies of the Member States and of the EU”. The definition of coherence of Bretherton and Vogler (2006) remains limited to explain the complexities of the Union’s foreign policy architecture and the involvement of third-party actors. The definition of coherence by Marangoni (2012) is the closest one in the literature covering all the aspects of the dynamics of EU foreign policy. Marangoni (2012: 5) defines coherence as “the perceived absence of contradictions between policies, instruments, institutions and levels of decision”. Based on the definition of Marangoni (2012), this research, defines coherence as the level of congruence and consistency between the EU actors and EU member states, between the EU institutions, between the EU foreign policy instruments and between the EU and the local stakeholders in Bosnia and Kosovo.

The concept of coherence serves multiple purposes for this study. First of all, this concept will constitute a framework to analyse the relations between all the main foreign policy actors, policies used in the external relations of the Union. Secondly, by using the concept of coherence, this study investigates the operationalisation of the EU foreign policy in Bosnia and Kosovo. By focusing on the EU foreign policy instruments of enlargement and the CSDP missions by the EU in Bosnia and Kosovo, this research depicts the coherence level between the EU institutions and actors both in Brussels and in the third countries, between EU policy instruments, between EU member states and EU, and finally between the EU agents and the local stakeholders which are the “receivers” and “implementers” of the EU accession reforms.

1.1.2 Types of coherence

To examine the coherence of the Union’s foreign policy, it is necessary to define different “types” of coherence. There are several frameworks in the existing literature

to analyse coherence. Gebhard (2011; 107) defined four types of coherence: vertical, horizontal, internal and external coherence. Vertical coherence focuses on the degree of “consensus” and complementarity between the EU and EU member states level (Gebhard, 2011: 107). Horizontal coherence is related with the concertation between “the CFSP and the [other]4 external policies” of the Union (Gebhard, 2011: 107).

Finally, external coherence refers to the coherence between the Union and third-party actors and it focuses on the external representation of the EU as an actor (Gebhard, 2011: 107).

Similarly, Nuttall (2005) also suggests four layers of coherence being horizontal, vertical, institutional and external. Horizontal coherence focuses on the coherence between different Union policies and focuses on the consistency between different EU policies such as the external trade policy, the ENP, enlargement, and the CSDP. Vertical coherence focuses on the coherence between member states and the Union and focuses on the levels of complementarity between the foreign policies of Union and the EU member states. (Nuttall, 2005). Institutional coherence analyses the coherence between the EU institutions, and finally “external coherence is related to the way the EU presents itself to third par- ties or within a multilateral system” (Gebhard 2017: 112).

Elgström and Chaban (2015), in addition to Nuttall’ s and Gebhard’s four dimensions of coherence, add the “chronological coherence” focusing on the consistency of the policies and “implementation coherence” based on the coherence “between words and deeds”. On the other hand, Mayer (2013) suggests five types of coherence. Like Nuttall (2005), Mayer’s first two types are vertical and horizontal coherence. The third dimension of Mayer (2013) is the “narrative coherence” which contains similarities with the implementation coherence of Elgström and Chaban (2015). The fourth type is strategic coherence states that “general direction and purpose of all EU external policies must be free of contradictions” (Mayer, 2013). The fifth dimension is the “external engagement coherence” and this type of coherence is about conducting consistent external policies with international partners (Mayer, 2013).

In order to analyse the coherence level of peace operations of the UN, the EU and NATO, De Coning and Friis (2011) defined four levels of coherence: “intra-agency coherence” focusing on the “consistency among the policies and actions of an individual agency”. The “whole of government coherence” focuses on the “consistency among the policies and actions of the different government agencies of a country”, “inter-agency-coherence” which denotes “the consistency among the policies pursued by the various international actors in a given country context” and finally the “international-local coherence” analysing the “consistency between and among the policies of the internal and external actors”. It can be argued that the categorizations made by De Coning and Friis (2011) and Mayer (2013) focus on the external-local dimension of coherence. However, these works fail to analyse how the internal coherence of an international actor (EU, NATO, or the UN) shapes the perceived coherence of the local agents that play a crucial role in in the implementation of the policies/reforms.

In light of the existing literature, to analyse the types of coherence of the Union’s external action in Bosnia and Kosovo, we will use the framework proposed by Simon Nuttall (2005) which is composed of four dimensions/types of coherence: horizontal, vertical, institutional and external. However instead of analysing the concept of “external coherence”, which adopts a top-down approach and overlooks the local dimension, we will introduce the concept of “perceived coherence”. The latter analyses the degree of coherence perceived by the local stakeholders “receiving” the EU foreign policy applied in their country. The way political elites perceive the coherence of the foreign policy instruments and the institutional actors of the EU will be a determining factor shaping the effectiveness of the EU in Bosnia and Kosovo. In other words, the implementation of the EU’s foreign policy instruments such as the EU accession process in Bosnia and Kosovo does not only depend on the internal coherence of EU (institutional, vertical, horizontal) but also on the perceived coherence of the local agents.

Non-state actors such as the civil society organisations have a determining impact on the implementation of the Union’s foreign policy. Non-state actors have become “agents of foreign policy” (Böttger & Falkenhain, 2011: 10). There is a two-way process between the EU and the “receivers” of its foreign policy tools. In the cases of

the EU’s relations with Bosnia and Kosovo, the Union’s relationship with Bosnian and Kosovar civil society and NGOs will play an important part in this research. The “perceived coherence” of the EUFP will be the fourth testing criterion of the foreign policy coherence of the Union in this research. Accordingly, we will focus on the perceived coherence and the “image” of the Union’s external action in Bosnia and Kosovo with the help of semi-structured interviews conducted with influential civil society organizations and NGO in these two countries considered.

In Bosnia, Kosovo and other states and regions of the World, the EU interacts not only with local governments and administrations but also NGOs, media, civil society, and other interest groups. As Lucarelli and Fioramonti (2010: 1) argue, “if the EU wants to have a chance to implement efficient policies, it cannot avoid taking into serious consideration expectations, images and perceptions in the rest of the world”. Accordingly, in our analysis, we will focus on all of these actors the EU interacts in its foreign policy.

Perceived coherence is also related to the concept of “legitimacy”. The latter can be defined as: “a broad degree of acceptance by those directly affected by governance” (Armstrong & Gilson, 2011: 3). Perceived coherence and the legitimacy of the Union’s foreign policy in the eyes of local governments and civil society will be decisive for the success of EU’s policies in the region considered (Elgström and Chaban, 2015). The image of the Union can be positive, such as a “family as something that can provide people with a higher ideal, something to be ‘proud of’; and negative, like ambivalence and confusion” (Panighello, 2010: 100). This perceived image would, in turn, impact the perceived coherence of the EU’s foreign policy applied in third parties.

1.1.3 Degrees of coherence

In addition to the types of coherence, we also need to define a framework to examine the degree of coherence within these types. This framework will measure the operationalization of the EU foreign policy coherence based on three measurement scale: low coherence, partial coherence and high coherence. Accordingly, in this research, we will focus on how the interaction between the EU institutions and the EU member states shape both the EU foreign policy and national foreign policies of

member states. Low coherence denotes that there are high levels of contradictions and inconsistencies between the foreign policy actors and instruments of the EU. Medium coherence means that despite some problems of cohesion and discrepancy regarding the operationalization of the EU foreign policy, the EU manages to operationalize it foreign policy instruments relatively coherently and consistently. Finally, high coherence denotes that the EU actors have managed to assure being fully coherent by assuring the “symbiosis” between its foreign policy instruments.

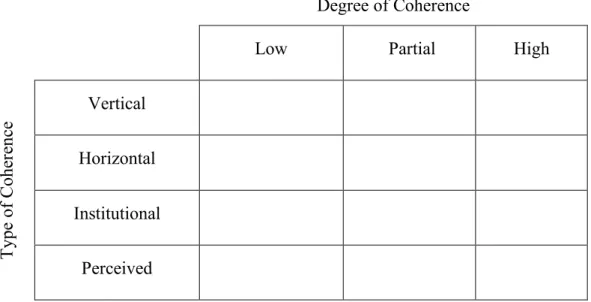

The following Table 1 demonstrates the framework that will be applied to examine the foreign policy coherence of the EU in Bosnia and Kosovo.

Degree of Coherence

Low Partial High

T ype of C ohe re nc e Vertical Horizontal Institutional Perceived

Table 1 Framework for analysing EU Foreign Policy Coherence

1.1.4 Coherence-effectiveness relationship

One of the most critical discussions in the literature on the concept of coherence is the latter’s relationship with the concept of “effectiveness” (Gauttier, 2004; Bertea, 2005; Nuttall, 2005; Gebhard 2011; Thomas, 2012). State actors, international institutions and non-formal actors perceive the achievement of coherence as a key element to become an effective international actor. Accordingly, states, international organisations created “a range of concepts, models and tools aimed at enhancing overall coherence” (De Coning & Friis, 2011: 246). Increasing coherence is generally accepted as a factor in increasing the effectiveness of the Union’s policies (De Coning

& Friis, 2011: 253). Many scholars argue that there is a positive correlation between coherence and effectiveness (Gauttier, 2004; Bertea, 2005; Nuttall: 2005; De Baere, 2008; Thaler, 2015: 6). Proponents of this view argue that achieving coherence is a “requirement towards more effectiveness in EU foreign policy” (Thaler, 2015: 29). According to Gauttier (2004: 36) “coherence and the absence of contradiction are crucial to effectiveness” De Baere (2008) contends that the effectiveness of the Union’s foreign policy depends on its coherence.

On the other hand, another wave of EU scholars argued that there is no proven positive relationship between coherence and effectiveness (Thomas, 2012; Elsig, 2013; Niemann & Bretherton 2013; Müller & Falkner, 2014). According to Neumann and Bretherton (2013: 267) when we evaluate effectiveness, we cannot prove” a linear relationship between increased coherence and greater effectiveness in terms of goal attainment”. Similarly, Carbone (2013) argued that aiming to increase coherence can lead to third-party resistance and have a negative impact on reduced effectiveness. According to Novak (2014: 68) “the obsession with consensus” in not necessarily a beneficial strategy.

By adopting the view that there is no direct correlation between coherence and effectiveness, this research argues that there are intervening factors between the internal coherence of the Union and the effectiveness of the EU foreign policy.

1.1.5 How to define and measure effectiveness of the EU’s Foreign Policy? It is not easy to analyse the effectiveness of the Union’s foreign policy in general, let alone in the cases of Bosnia and Kosovo. As Niemann & Bretherton (2013: 267) stated, “effectiveness is notoriously difficult to investigate and assess”. Most of the literature on effectiveness analyses the latter as an actor’s ability to reach the objectives set about a specific issue (Laatikainen & Smith, 2006; Thomas, 2012; Niemann & Bretherton 2013, Van Schaik, 2013). Thomas (2012: 460) defined effectiveness as “the Union’s ability to shape world affairs following the objectives it adopts on particular issues”. To examine the relationship between coherence and effectiveness, we will first need to define how we should evaluate foreign policy effectiveness, more specifically how

we will qualify the EU to be effective or not in the cases of Bosnia and Kosovo. In order to analyse the effectiveness of the EU foreign policy in Bosnia and Kosovo, we will focus on the issue of “progress” and “improvement” rather than achieving a specific goal. Bosnia and Kosovo are both potential candidate countries. Our analysis or more specific measurement of effectiveness should not be based on the end results but on the improvement made during the process. For instance, in our cases of Bosnia and Kosovo, the main foreign policy instrument used by the EU is the EU accession process. In other words, the “ultimate end” is the accession of these two states into the EU. However, as we cannot expect Bosnia and Kosovo to be an EU member in the near future, it would be irrelevant to measure the effectiveness of the EU’s policy in these two countries considered on the base of their EU accession.

By analysing the effectiveness of the cases analysed, being constitutional and police reforms and Operation Althea for Bosnia and EULEX and Belgrade-Kosovo dialogue in the case of Kosovo, we will measure the progress made. As this aim is a long process, we will analyse the effectiveness of the EU in Bosnia and Kosovo by using a “measurement of progress”. In other words, we will not focus on “goal achievement” but on the improving made regarding achieving the considered goal. In order to do this, we will use the framework of Gordon Crawford (1997) In order to make an accurate analysis of the EU’s foreign policy, Crawford (1997) has used a “four- point scale to measure the improvement levels towards effectiveness. These levels are: 0- no improvement or negative trend, 1 - possible improvement but unclear, 2 -modest improvement 3 - significant improvement

By modifying the scale used by Crawford (1997), I will analyse the effectiveness of the EU in Bosnia and Kosovo according to a “3 level effectiveness scale”, which is:

0- No (low) improvement or negative trend would be considered as “no effectiveness where none of the objectives are realized.

1- Medium improvement would medium level effectiveness where and finally 2- Significant (high) improvement would be total effectiveness.

After having made the quantitative analyses of the effectiveness of the EU’s foreign policy in Bosnia, we will use the measurement scale to visualize the degrees of effectiveness of the Union’s foreign policy in Bosnia.

1.1.6 Contribution to the existing literature

There is also a growing literature on the foreign policy coherence of the EU (Gauttier, 2004; Nuttall, 2005; Hillion 2008; Portela & Raube, 2012, Mayer, 2013: Kostanyan, 2014; Oproi, 2015). Coherence has generally been argued as a crucial element for the success of EU’s external policies by most of the academics. The concept became a prominent one to analyse the EU’s external policies “not because of its successes, more due to the impact of its failures” (Quinn, 2012: 45 as cited in Mahncke & Gstöhl, 2012 Eds.). As Portela and Raube (2009: 2) argued, “few notions in European foreign policy are characterised by such a high degree of complexity as the concept of coherence”. Coherence has been used to analyse different types of policies of the Union such as development, climate and security. (De Jong & Schunz, 2012; Thomas, 2012; Furness & Ganzle, 2017). De Jong and Schunz (2012) analysed the impact of the Lisbon Treaty on the coherence of energy and climate policies of the Union. By using “a systematic analysis of EU and Member State actions in the areas of EU external energy and climate policies, both prior and immediately after the Treaty’s arrival”, De Jong and Schutz (2012: 195) evaluated “whether Lisbon is able to live up to the initial expectations”. De Jong and Schutz (2012: 195) argued that coherence of the Union’s action in the fields of energy and climate remained limited after the institutional changes were made with the Treaty of Lisbon. Similarly, Furness and Ganzle (2015) focused on the relationship between development and security policies of the Union outside of the Union. and argued that “the coherence of security and development policies remains challenged” after the creation of the EEAS.

The studies mentioned above on the foreign policy coherence of the Union, focus on either the legal or the political science perspective (Oproiu, 2015: 845). The legal perspectives focus on the place of coherence in the EU Treaties. (Tietje, 1997; Wessel, 2000) On the other hand, political science-based studies use case studies to test mainly these three dimensions of coherence or generally the “incoherence” of the Union. (Carbone, 2012; Portela & Raube, 2012) Unfortunately, scholars have overlooked the sociological dimension of the coherence. Existing scholarly works fail to cover some of the major dimensions defining or shaping the coherence of the Union’s foreign

policy being namely: the interaction between different actors involved in the process and the ways the local agents perceive the Union’s policies, actors and member states. One of the purposes of this study is to analyse the “local” dimension to the study of coherence, which is the “perceived coherence” of the Union by the parties concerned which would be Bosnia and Kosovo for our case. By focusing on the relationship between the governing elites, the civil society and the EU in Bosnia and Kosovo, this research contributes to the existing literature on the role of the local stakeholders/actors regarding the operationalization of the EU foreign policy in third countries.

The perception of locals will be a decisive factor for the success of EU policies in Bosnia and Kosovo. The perception of the political elites and the civil society is one of the most crucial factors regarding the implementation of the EU accession process. The perceived coherence analyses if the political elites and the CSOs perceive the EU foreign policy instruments as coherent or not. This research depicts the intervening variables that come into play between the internal coherence (institutional, horizontal, vertical) of the Union and the perceived coherence and the effective operationalisation of EU foreign policy instruments applied in Bosnia and Kosovo. In other words, one of the main contributions of this research would be to analyse the coherence of the Union’s foreign policy by focusing on the interaction of the EU with third parties (both state and non-state actors) and the way the latter reacts the Union’s external action. The “perceived coherence” of the Union and its foreign policy is an important coherence dimension to analyse and “the failure to investigate external images not only results in a gap in the literature that deserves to be filled but might also have/have had important practical repercussions” (Lucarelli & Fioramonti, 2010: 3).

Apart from the theoretical contributions to the existing academic works, this research aims to contribute to the empirical literature on the EU foreign policy in Bosnia and Kosovo. Academic literature focusing on the EU foreign policy in Bosnia or Kosovo usually focuses mostly on only one of these cases rather than making a comparative analysis (Juncos, 2007; Shepherd, 2009; Brljavac, 2011; Greiçevci, 2011). Accordingly, this research aims to contribute to the existing research on the EU foreign policy on Bosnia and Kosovo by making a comparative analysis of these two cases. By using the comparative case study method, this study aims to compare the coherence

and effectiveness of the EU foreign policy instruments used in Bosnia and Kosovo by tracing the similarities and differences of the EU foreign policy coherence in two potential candidate countries of the Western Balkan region.

1.2 Methodology

1.2.1 Research Questions

According to the framework of analysis described above, research questions of this study will be as follows:

1) How coherent have the EU foreign policy instruments of enlargement, CSDP missions and diplomacy been in Bosnia and Kosovo?

2) How effective has the EUFP been in Bosnia and Kosovo?

3) How have the changes made after the Lisbon Treaty, more specifically appointment of the HR/VP and the creation of for the EEAS impacted the foreign policy coherence of the EU in its action over Bosnia and Kosovo? 4) Has there a trade-off between coherence and effectiveness in EU foreign policy

domain in the cases of Bosnia and Kosovo?

5) Under what circumstances is such a trade-off manifested?

1.2.2 Usage of the comparative case study method

In order to study the EU foreign policy coherence and effectiveness in Bosnia and Kosovo, we will use comparative case study method. Cases studies can be qualitative or quantitative (Kaarbo & Beasley, 1999: 373). Case studies can serve multiple purposes. Case studies can be used to develop or build new theories, refine theories or to test existing theories (Kaarbo & Beasley, 1999). A single case study can be defined as "an in-depth, multifaceted investigation, using qualitative research methods, of a single social phenomenon" (Orum, Feagin & Sjoberg, Eds. 1991: 2). Rather than focusing on one case, comparative case studies focus on the question “how much we

might achieve through comparison?” (Bartlett & Vavrus, 2017: 6). According to Goodrick (2014: 1) “comparative case studies involve the analysis and synthesis of the similarities, differences and patterns across two or more cases that share a common focus or goal” (Goodrick, 2014: 1). Tellis (1997, as cited in Zainal, 2007: 5) argues that “a common criticism of case study method is its dependency on a single case exploration making it difficult to reach a generalizing conclusion”. Therefore, in order to overcome this disadvantage of single case studies, we will apply a comparative case study method to analyse the coherence and effectiveness of EU foreign policy in Bosnia and Kosovo.

In this research, we will adopt the comparative case study research method of Alexander George (1979), defined as a “method of structured, focused comparison”. George’s (1979; 61-62, as cited in Kaarbo & Beasley, 1999: 377) method is "focused because it deals selectively with only certain aspects of the historical case [. . .] and structured because it employs general questions to guide the data collection analysis in that historical case". While studying the coherence and effectiveness of the EU foreign policy in Bosnia and Kosovo, we will focus on the enlargement and CFSP dimensions of the Union’s foreign policy by focusing on a similar set of research questions to collect information. By adding the new analytical concept of “perceived coherence” to the existing frameworks analysing the EU foreign policy coherence in the literature, this research aims to refine the analysis of coherence of the Union and also contribute to the literature based on the EU foreign policy in Kosovo and Bosnia.

1.2.3 Reasons for case selection

The EU’s “experience” in foreign policy issues and more specifically in security and defence related policies were limited until the emergence of the crisis in the Balkans in the early 1990s and the signing of the Maastricht Treaty in 1992. The changing dynamics of the international system after the end of the Cold War and the changing structure of the Union with the adoption pillar system with the introduction of the CFSP pillar gave the necessary incentive and needed for the EU to become a foreign policy actor in Bosnia from the early 1990s. It was the famous “hour of Europe” as Jacques Poos, the former head of the Union’s Foreign Affairs Council and the former

foreign minister of Luxembourg had argued.5 However, the EU has generally seen to

be too divided to act and play a role in a peace plan after the conflict in former Yugoslavia (Burg & Shoup, 1999). Scholars have generally seen the crisis in the former Yugoslavia as “the first test for the embryonic CFSP” (Juncos, 2005: 88). With cases of Bosnia and Kosovo “the EU reinforced its military and political presence in the Balkans due to the strategic importance of the region and its geographical proximity with the EU” (Juncos, 2005: 88). The cases of Bosnia and Kosovo have been a catalyst “for the EU decision-makers to create the ESDP and to appoint for the first time the High representative of the CFSP” (Greiçevci, 2011: 300).

The cases of Bosnia and Kosovo are ideal to make a comparative case study analysis to examine the coherence of EU policies, institutions, member states. The EU’s foreign policy in Kosovo and Bosnia is multinational and “it has ranged from strict conditionality” to peacekeeping and police missions and “bolstering the rule of law and border security” (Kirchner, 2013: 43). Bosnia and Kosovo are potential EU candidates and two CSDP missions. EUFOR Althea in Bosnia and EULEX the rule of mission in Kosovo are still operational. Apart from the historical importance of the cases of Bosnia and Kosovo for the emergence of EU as a foreign policy actor, in January 2018, the Western Balkans has been announced as one of the priorities of the European Council of the Bulgarian Presidency. The increasing importance of the Western Balkan region for the EU and in turn of the relations of the EU with Bosnia and Kosovo, make these two cases ideal for analysing the coherence and the effectiveness of the foreign policy instruments of enlargement and the CFSP.

Regarding the horizontal coherence there is on the one hand the European Commission controlled enlargement instruments and on the other the CSDP tools based on “high politics” controlled by the Council and implemented by the delegation and member states. Concerning the institutional coherence, the European Commission in Brussels, the delegation in Bosnia under the EEAS are all involved in the EU’s enlargement process. In a similar vein, the CSDP which is an intergovernmental policy of the Council supports the technical accession process controlled by the European Commission.

These two cases are comparable/similar but also different in many ways. To be more specific, the cases are similar because:

• Bosnia and Kosovo are both potential candidate countries.

• Both countries are “post-conflict” zones and are subjected to ongoing state-building experience.

• Both countries are composed of multi-ethnic societies.

• Both countries have hosted or still hosting CSDP missions (EU Police Mission and military mission EUFOR Althea in Bosnia, and EU rule of law mission EULEX in Kosovo).

However, the non-recognition of Kosovo by five EU member states constitutes a crucial difference between these two cases analysed. The contested independence/statehood6 of Kosovo does not only impact the vertical coherence

between the EU and its member states but also the coherence between the EU institutions and different policy instruments. Accordingly, comparing the cases of Bosnia and Kosovo would be fruitful to see if the how the vertical coherence between the EU and the member states affects the institutional and horizontal coherence of the EU. Kosovo is also an ideal case to analyse the impact of the creation of the European External Action Service (EEAS) and the High Representative and Vice President of the Commission (HR/VP) as the latter acted as the mediator of the normalization process between Kosovo and Serbia.

The “time range” of the relations of Brussels with Bosnia and Kosovo coincides perfectly with the apparition and the evolution of the CFSP. The analysis of post-Lisbon coherence in the EU foreign policy is crucial to understand “how EU instruments and policies with an external dimension are coordinated in order to enhance dialogue with third countries, apply conditionality and foster transformation in candidate and potential candidate countries” (Oproiu, 2015: 845). Accordingly, the two cases chosen are ideal for studying the coordination pre- and post-Lisbon coherence of the EU foreign policy as it involves all of the actors and institutions of EU foreign policy architecture.

1.2.4 Methods and sources to be used

This research uses the triangulation method which can be defined as the usage of “multiple methods […] in studying the same phenomenon for the purpose of increasing study credibility” (Hussein, 2009: 2). Accordingly, this research combines different qualitative research methods such as “document analysis” and interviews for data collection and for analysing the four types of coherence described previously. Document analysis is “a systematic procedure for reviewing or evaluating documents, both printed and electronic (computer-based and internet-transmitted) material” (Bowen, 2009: 27). The method of “document analysis requires that data be examined and interpreted in order to elicit meaning, gain understanding, and develop empirical knowledge” (Strauss & Corbin, 2008 as cited in Bowen, 2009: 27).

During the analysis, both primary sources (formal documents and reports of the European Council, the European Commission, the EEAS, and the EU Parliament) and secondary sources (academic journals and books) have been used in this research. For the analysis of the vertical, horizontal and institutional coherence of the Union, the relationships between the EU institutions namely the European Commission, the European Parliament and the EU Council has been an important focal point for this study. Accordingly, European Commission and Parliament reports and the European Council declarations on the cases of Bosnia and Kosovo constituted the main primary sources of this research.

Apart from primary sources such as the official EU documents and secondary academic literature, semi-structured interviews have been of crucial importance for this research. Accordingly, around 40 semi-structured interviews have been conducted with EU officers, Kosovar and Bosnian politicians and diplomats, Kosovar and Bosnian civil society organization members, policy experts and scholars. Interviews were conducted both in Brussels and the Western Balkan region. Interviews provided different angles of analysis for this study. Secondly, by relying on multiple sources of analysis, interviews have reduced the impact of biases and aimed to increase the credibility of the research. In order to minimize the biased views as much as possible, interviews from both “within” and “outside” of the EU, being the EU officials from

the Commission, the EEAS, the Council and the EP and local administration and civil society members in Bosnia and Kosovo have been conducted. Some of the interviewees have been left as anonymous at their request.

1.2.5 Limitations of the study

Case study method has also some disadvantages and limitations to be considered. Case studies have been criticized for failing to provide “scientific generalization” (Zainal, 2008). Notably, Yin (1994: 21) asks the question “How can you generalise from a single case?” In Bosnia and Kosovo, the Union uses similar foreign policy instruments which are enlargement and CSDP missions. Both countries suffer from ethnic nationalism and weak state institutions. At the same time, the cases have unique characteristics that shape the coherence and the effectiveness of the Union’s foreign policy. For instance, the non-recognition of Kosovo’s independence by five EU member states, make Kosovo a peculiar case to analyse. By choosing “comparable but also different” cases, such as Kosovo and Bosnia, this thesis aims to contribute to both the theoretical aspect of the literature of the “coherence” concept but also create a framework which is useable in future studies focusing on the EU foreign policy instruments of enlargement and CSDP missions.

One of the essential factors to be considered in this study has been the Bosnian and Kosovar public opinion, however because of the language barriers and the problems to access Bosnian and Kosovar resources, limitations occurred to make a comprehensive examination of the perceived coherence of the EU foreign policy in these two states. To overcome language barriers, the help of Bosnian and Kosovar colleagues and experts has been used for interviews as needed.

CHAPTER II

ANALYSING EUROPEAN FOREIGN POLICY: A LITERATURE

REVIEW

2.1 Introduction

Before focusing on the empirical analysis of the cases and the coherence and effectiveness of the EU foreign policy in the considered cases of Bosnia and Kosovo, we need to analyse the evolution of the European foreign policy by focusing on the literature regarding the EFP by focusing both on formal and informal actors and processes of the EFP. Accordingly, this chapter will provide a comprehensive review of the literature on EU foreign policy.

The EFP is a complex process. The main reason of the complexity of the EFP structure can be explained with the involvement of multiple actors in the policy-making process such as the member states, the EU institutions and the actors shaping the informal governance of the EU such as the civil society organizations (CSOs) and non-governmental organizations (NGOs). There has been a long debate concerning the question “who runs the Common Foreign and Security Policy (CFSP) of the Union?”. Some EU scholars argue that EU is an international organization run by the member states (Merlingen, 2012: 41). On the other hand, other scholars contend that the EU is a sui generis form of organization that is run by a system of networks rather than inter-state politics. Before focusing on the empirical analysis of the cases, we need to analyse the evolution of the European Foreign Policy (EFP) by focusing on the

literature regarding the EFP by focusing both on formal and informal actors and processes of the EFP. In order analyse the foreign policy coherence in Bosnia and Kosovo, we need to grasp the dynamics between the EU institutional actors and the local agents taking part in the operationalization of the EU policy. Accordingly, the analysis of the literature on formal and governance will play a guiding role for the future chapters of this study.

Certainly, national governments and the Union’s institutions are the main actors determining the guidance and the functioning of foreign, security and defence issues (Merlingen, 2012: 41). However, the main actors “need agents who deal with day to day management issues” (Merlingen, 2012: 41). Accordingly, the foreign and security policy of the Union is a “multiactor and multilevel policy system” that comprises national governments, EU institutions and non-governmental actors (Merlingen, 2012: 41). Domestic public opinion, NGOs and “epistemic communities” (Haas, 1992) involving transnational networks of professional experts are all parts of the general EU foreign policy system and should be taken into consideration when we analyse the foreign policy coherence of the Union. According to Smith, (2009: 5) approaches to the study of the European foreign policy should be diversified and it is impossible to define such a complex process involving EU member states, EU institutions and numerous “policy problems or issues areas” by a “single rigid definition”. “Monolithic theoretical approaches” based on tradition foreign policy studies are not suitable to analyse the complexities of the European foreign policy (Smith, 2009: 5).

By considering the above-mentioned complexity of the operationalization of the EFP, this chapter will be divided into two main parts to analyse the existing literature on EU foreign policy. Accordingly, in the first section I will focus on the formal governance of the EFP and review the existing literature and different waves of EFP studies and investigate how EU scholars have seen the Union becoming a global foreign policy actor and how they have studied the main constituents of EFP, which are namely: the issues, formal actors and processes of EFP. In the second part of this chapter, I will focus on the literature concerning the informal governance of the Union and study the interactions between EU’s institutional and private actors such as the CSOs.

2.2 Literature on the Formal Governance in the EU Foreign Policy

Studies focusing on the EFP “present a number of challenges and opportunities to political scientists” (Smith, 2009: 1.) The literature on EU foreign policy generally uses the term “European foreign policy” as it is almost impossible to “distinguish EU foreign policy from European foreign policy” (Smith, 2009: 1). EFP can be defined as “European policies that is directed at the external environment aiming to influence that environment and the behaviour of other international actors within it” (Keukeleire & Delreux, 2014: 1). In this part, I will focus on the literature analysing the EU as a global actor and will scrutinise how EU scholars have studied the evolution, issues, actors and processes of EU foreign policy.

When we analyse the literature of the EFP, we can see that the issues discussed by the scholars are not independent of the chronology of the main foreign policy developments within the Union. In other words, the main subjects of analysis of the EU academics have been the developments taking place in the EFP structure. Every major reform of the EFP has been a source of analysis for the scholars. According to Michael E. Smith (2009: 6) we can categorize European foreign policy research field into three periods. The first period is between the 1950s and 1960s and is based on “traditional International Relations/Foreign Policy Analysis speculating regarding the potential for European Foreign Policy” (Smith, 2009: 6). The second period comprises the 1970s and early 1980s and focuses on the creation of the European Political Cooperation (EPC) (Smith, 2009: 6). The last period starts with the Single European Act (SEA) in 1987 and ends with the inception of the formal European Foreign Policy with the Treaty on the European Union (1992). In addition to these three periods, the fourth period analysis of the EFP should “logically” start with the impact of the Lisbon Treaty on the institutional structure of the Union’s foreign policy and notably the creation of new institutional bodies such as the European External Action Service (EEAS) and the High Representative and Vice President of the Commission (HR/VP).

2.2.1 Literature on the Evolution of European Foreign Policy

Early periods of the EFP have generally been analysed with a focus on integration theories studying “the foreign policy implications stemming from European economic integration” (Smith, 2009: 7). During this period, Ernst Haas (1958; 1961; 1964) focused on regional integration with his theory of neo-functionalism and the concept of “spillover”. Haas (1958: 16) focused mainly on the economic dimension of integration and the latter’s impact on the foreign policy of the Union by suggesting that integration leads to different types of spillovers by bringing “loyalties, expectations and political activities toward a new centre, whose institutions possess or demand jurisdiction over the pre-existing national states”. Accordingly, neo-functionalism explained the process of integration with the concepts of “functional spillover” between issue areas and “political spillover” involving the supranational actor” (Caporaso, Cowles & Risse-Kaplan, 2001). On the other hand, scholars coming from the realist background were not optimistic about the potential emergence of a common EFP (Smith, 2009: 8). Hoffman (1965) stated that European states were not keen to delegate their sovereignty to a supranational body and did not foresee the emergence of a common EFP. Therefore, EU member states would keep their independence and would rely on North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO) for their security and foreign policy related issues.

One of the most important attempts to act as a united voice in foreign policy issues was the Hague Summit of 1969. The summit coincided with the détente period of the Cold War and the end of the Charles de Gaulle’s rule that meant the removal an obstacle to the formation of new European initiative (Keukeleire & Delreux, 2014: 43). As a result of the Hague Summit, the Luxembourg Report was signed, and the EPC has begun. The EPC had two objectives:

To ensure greater mutual understanding with respect to the major issues of international politics, by exchanging information and consulting regularly 2) to increase their solidarity by working for a harmonization of views, concertation of attitudes and joint action when it appears feasible and desirable (Davignon Report, 1970: 3).

The Hague Summit was a crucial step for the EFP as it has created for the first time, regular meetings between the foreign ministers of the EC’s member states and regular

consultations concerning foreign policy issues (Bindi, 2010: 19). In the 1970s with the creation of the European Political Cooperation (EPC) in 1970, EU scholars became more optimistic about the possibility of a common foreign policy for the European Community (EC). The EPC was an important development for the EC to act as a common voice in foreign policy issues and became a “tool” to improve the coherence of the EC’s foreign relations.

The Copenhagen Report of 1973 indicated that the EPC created an institutional framework which focuses on the problems of international politics. The report defined the main quasi-institutional bodies of the EFP such as the Political Committee preparing the ministerial meetings, the Group of Correspondents, the system of European Telex (COREU) and the subcommittees and working groups dealing with the Commission on Security and Cooperation in Europe and geographic regions such as the Middle East, Asia and the Mediterranean (Bindi, 2010: 19). The EPC aimed to support the actions of “the institutions of the Community which are based on the juridical commitments undertaken by the member states in the Treaty of Rome”.7 The

EPC arrangement remained totally intergovernmental and no transfer of competences to EC institutions took place however, “interaction between EPC and the EC in both institutional and policy matters was unavoidable” as the EPC relied on the EC concerning its declarations and main initiatives (Keukeleire & Delreux, 2014: 44). It is possible to argue that the institutionalization of EFP has started with the creation of the EPC in 1970. The security policy of the Union has remained intergovernmental however the Commission has created its external relations in many fields such as trade, development and humanitarian affairs (Keukeleire & Delreux, 2014: 46).

Since the 1970s and the creation of the EPC, there have been constant efforts on the to link the EFP process to the main institutions of the EC (Nuttall, 1992 as cited in Tonra & Christiansen, 2004: 5). During this period, EPC practitioners were also the ones studying the EFP by focusing on the issues of “social networking” and “soft law” (Von der Gablents, 1979; de Schotheete de Tervarent, 1980 as cited in Smith, 2009: 10). One of the important issues discussed at the 1970s has been the “coordination reflex” or the habit of the member states to consult each other concerning the foreign policy

issue before making their own foreign policy decisions (de Schoutheere de Tervarent, 1980). The academic works studying the tendency of the member states consulting each other on foreign policy issues became the basis for future works focusing on socialization and institutionalization of EFP (Smith, 2004a).

The coordination of the EU member states in international organizations was another subject of analysis during the 1970s. A series of studies have been conducted concerning the voting behaviour of EU member states in the UN General Assembly (Hurwitz, 1975, 1976; Lindemann, 1976). These works concluded that EU member states voted as a bloc around 60 percent of the time. Scholars have also focused on regional issues such as the role of the Union in the Middle-East peace process (Allen & Pijpers, 1984) and in the Euro-Arab Dialogue (Allen, 1978). Allen and Pijpers (1984) argued that the limited institutional structure of the EFP at that time managed to produce common views but the EC lacked an institutional leadership and policy instruments. The record of the EPC has not been very positive as it remained ineffective to formulate concrete policy issues in the cases of Middle-East, Afghanistan and Poland (Allen & Pijpers, 1984: 46).

In the early 1980s, academics have continued to study the impacts of the EPC on national foreign policies of member states. In his book entitled National Foreign Policies and European Political Cooperation, Christopher Hill (1983) focused on the relationship between national foreign policies and the EPC. Another important work investigating the EPC procedures and policies is the book European Political Cooperation: Towards a Foreign Policy for Western Europe written by Allen, Rummel and Wessels (1982). During this period, the main works focusing on European integration, such as the periodic editions of “Policy-making in the European Community” containing chapters on EPC/European Foreign Policy in a regular manner (Wallace, 1983; Lodge, 1989 as cited in Smith, 2009: 15). One of the main contributions of the EFP literature in the 1980s has been the study of the role of the EC institutions such as the role of the Commission (Nuttall, 1988) and the role of the Presidency (de Schoutheere de Tervarent, 1988) in EFP.

2.2.2 The Emergence of the Common Foreign and Security Policy

Structural developments in the international system after the 1990s such as the war in Yugoslavia, the emergence of a multipolar world have forced the EU to speak with a common voice. According to Tonra and Christiansen (2004: 2), after the 1990s, a rapid expansion has occurred “in the policy-scope and institutional capacity of EU foreign policy-making and a consequent raising of expectations” regarding what the EU would be capable to accomplish in the Common Foreign and Security Policy (CSFP). Wars in Bosnia and Kosovo have been analysed as perfect examples of this phenomenon (Lucarelli, 2000; Papadimitriou, 2001). One of the most cited works on EFP after the Maastricht Treaty has been Christopher Hill’s (1993) article entitled “The Capability-Expectations Gap, or Conceptualizing Europe’s International Role” in which he analysed the gap between the aims and the resources of the Union in foreign policy issues. Hill (1993) emphasized in his “famous” work that the EU had lacked the necessary capabilities to become a decisive international actor. Hill (1993) argued that the relationship between the means and ends of the Union’s foreign policy was problematic and that the Union lacked a clear strategy in its external action. Hill (1993: 23) defined the “capability-expectation gap” by using three determinants: “the ability to agree, resource availability and the available instruments of the EC” and argued that the capability expectation gap is problematic for the Union to achieve its foreign policy objectives because “it could lead to debates over false possibilities both within the EU and between the Union and external supplicants”, and it would “likely to produce a disproportionate degree of disillusion and resentment when hopes were inevitably dashed”. He contended that if the Union aims to close the gap considered, its foreign policy should be based on actions rather than aspirations (Hill, 1993: 23). Accordingly, the EU would need to install the necessary institutional and decision-making mechanisms to realize its foreign policy goals (Hill, 1993: 23).

Another important EFP subject analysed by the scholars after the 1990s has been the decision-making process within the area of the CFSP (Regelsberger, de Schoutheete & Wessels, 1997; Holland, 1997, Lewis, 2000). These studies were important for the EFP studies because they have provided an analytical insight “to the way in which business is conducted within CFSP and how the process has developed” (Tonra &

Christiansen, 2004: 3). As the EU decision-making process is determined between the axis of intergovernmentalism and supranationalism, the EU foreign policy studies are also divided between these intergovernmental/supranational views (Tonra & Christiansen, 2004: 3). The literature based on supranationalism argues that the Union influences the national foreign policy decision-making of member states (Sandholtz & Sweet, 1998; Hooghe & Marks 2008; Dougan, 2008). On the other hand, research based on intergovernmentalism focus on the bargaining process between the EU member states aiming to preserve the national interests of the latter (Putnam, 1988; Koenig-Archibugi, 2004). Intergovernmentalist studies being similar to neo-realist ones, argue that EFP regime is a power-based one and that the “rules and purpose of the game are established by the most powerful states” such as France and Germany (Tonra & Christiansen, 2004: 7). A considerable portion of the works in the EFP research field argued that national interests of EU member states have impeded the creation of foreign policy institutions for the EU (Hill, 1993; Jupille, 1999; Smith, 2004a).

Andrew Moravscik (1998: 75) with his theory of liberal intergovernmentalism (LI), suggested that the main source of integration is based the national interests of member states the latter’s “relative power they each bring to Brussels”. Moravscik’s (1998) model of LI is based on the Stanley Hoffmann’s (1966) concept of “intergovernmentalism”. Moravscik (1998: 4: 9) posits that “a tripartite explanation of integration – economic interests, relative power, credible commitments – accounts for the form, substance, and timing of major steps toward European integration”. Moravscik (1998: 3) also argues that the European integration is based on a three-stage process: the first stage is the emergence of national preferences, the second one is the intergovernmental bargaining and the bargaining power of states and finally the third one is the institutional choice based on the desire to “enhance the credibility of interstate commitments”. LI has been criticized for its failure to consider “the endogeneity of the integration process”, i.e. for how integration decisions at one point in time are shaped and constrained by the effects of earlier integration decisions” (Schimmelfennig, 2015: 178).