Downloaded from http://journals.lww.com/jonmd by ilvk+8seBd3ibuRJ+VK1SFWuJlpIsxQW1cjwkJdbNemEi4XR7r3mCe2biCtLFx4WGlaUUYaO/PmOgcnqJscl7JCksdd4y9psqFF8FajXMXA= on 07/30/2019 Downloadedfrom http://journals.lww.com/jonmdby ilvk+8seBd3ibuRJ+VK1SFWuJlpIsxQW1cjwkJdbNemEi4XR7r3mCe2biCtLFx4WGlaUUYaO/PmOgcnqJscl7JCksdd4y9psqFF8FajXMXA=on 07/30/2019

Association of Psychache and Alexithymia With Suicide in Patients

With Schizophrenia

Mehmet Emin Demirkol, MD,* Lut Tamam, MD,* Zeynep Naml

ı, MD,†

Mahmut Onur Karaytu

ğ, MD,‡ and Kerim Uğur, MD§

Abstract:Suicide is a leading cause of death in patients with schizophrenia.

Previous studies have mostly investigated the association between suicide and sociodemographics, positive and negative symptoms, and depressive symptoms. This study evaluated psychache and alexithymia in patients with schizophrenia, which have both been associated with suicide attempts and thoughts in patients with other psychiatric disorders. Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale (PANSS), Psychache Scale (PAS), Beck Scale for Suicidal Ideation (BSSI), Calgary Depres-sion Scale for Schizophrenia (CDSS), and Toronto Alexithymia Scale (TAS) scores were obtained in 113 patients with schizophrenia, including 50 with suicide at-tempts. PANSS positive symptoms and general psychopathology subscale, CDSS, BSSI, TAS, and PAS scores were significantly higher in patients with suicide at-tempts. In multivariate logistic regression analysis, only the PAS score was an inde-pendent predictor of attempted suicide. Mediation analysis demonstrated that psychache (both directly and indirectly) and alexithymia (indirectly) might be asso-ciated with the risk of suicide in these patients.

Key Words: Alexithymia, psychache, depression, suicide, schizophrenia

(J Nerv Ment Dis 2019;207: 668–674)

T

he life span of patients with schizophrenia is shorter than that of thegeneral population (Saha et al., 2007). Forty percent of early deaths in these patients have nonnatural causes, including suicide, accidents, and violence (Bushe et al., 2010; Hor and Taylor, 2010). Although the lifetime risk of suicide in patients with schizophrenia cannot be de-termined for methodological reasons, some studies have reported that the lifetime mortality rate attributable to suicide is 4.9% in patients with schizophrenia (Hor and Taylor, 2010; Palmer et al., 2005).

Known risk factors for suicide in patients with schizophrenia in-clude young age, male sex, being single, being unemployed, living in the countryside, disease onset at a late age, concomitant physical ill-ness, depressive symptoms, positive symptoms such as delusions and auditory hallucinations, insight, and a family psychiatric history. Hope-lessness, anxiety, low self-esteem, thoughts of guilt, and posttraumatic stress disorder are also considered to be significant risk factors for sui-cide (Hor and Taylor, 2010). Completed suisui-cides in patients with schizophrenia have been found to be related to previous suicide at-tempts and to remote and recent suicidal thoughts (Fialko et al., 2006; Hawton et al., 2005). Several risk factors for suicide in patients with psychiatric disorders have been proposed, and the association between psychache and suicidal behavior has been emphasized in recent years (Verrocchio et al., 2016). Psychache has been proposed to account for the relationship between depression and suicidal thoughts, preparation for suicide, and previous suicide attempts (Campos and Holden,

2016; Patterson and Holden, 2012). Psychological pain was first

de-scribed by Shneidman (1996) as“psychache,” then by Orbach et al.

(2003) as“mental pain,” then by Mee et al. (2006) as “psychological

pain,” and later by other authors as “emotional pain” or “psychic pain”

(van Heeringen et al., 2010). According to Shneidman, psychache re-fers to intense emotions, such as sorrow, shame, guilt, fear, worry, and loneliness, rather than physical pain. Psychache is believed to emerge when a person's needs are not met or acknowledged or when the person is frustrated. Shneidman hypothesizes that the risk of suicide increases when an individual has unbearable psychache. One of the most notable aspects of Shneidman's theory is the proposal that suicide will not occur in the absence of psychache (Mee et al., 2006; Shneidman, 1999; Stanley et al., 2016). In a recent meta-analysis of 20 studies, the in-tensity of psychological pain was found to be higher in subjects with a lifetime history of suicide attempts and suicidal ideation (Ducasse et al., 2018). Psychological pain was associated with suicide even when the de-pression levels were not different between subjects.

Although alexithymia was proposed to explain conditions associ-ated with psychosomatic symptoms, it may also be seen in patients with other mental disorders and even in healthy individuals. Alexithymia man-ifests as problems with emotional processes and interpersonal relation-ships (Blanchard et al., 1981; Yurt 2006). Individuals with alexithymic features are described as having difficulty expressing emotions, being aware of emotions, and differentiating emotions (Motan and Gençöz, 2007). Many studies have reported that individuals with alexithymia have higher levels of stress and develop more intense somatic symptoms and more severe anxiety and depression than those without alexithymia (Bankier et al., 2001; De Berardis et al., 2017).

Research in the general population and in subjects with various psychiatric disorders and medical conditions has demonstrated that alexithymia increases the risk of suicide (De Berardis et al., 2017). A study that assessed the association between alexithymia and the risk of suicide in patients with a diagnosis of schizophrenia demonstrated that those with alexithymia had persistent suicidal thoughts and more severe depressive symptoms independent of negative and positive symp-toms of schizophrenia (De Berardis et al., 2017; Marasco et al., 2011).

Psychache and alexithymia have been investigated in several psychiatric disorders, particularly depression, and have been confirmed to be risk factors for suicide; however, they have not been evaluated ad-equately in patients with schizophrenia and a history of suicide at-tempts. The aim of this study was to demonstrate the association of psychache and alexithymia with suicide in patients with schizophrenia. This study also investigated whether psychache and alexithymia were associated with other psychological factors.

METHODS Sample Population

This study included 130 patients who were admitted to the Psychiatry Department of Cukurova University Medical School with a diagnosis of schizophrenia according to the Diagnostic and Statis-tical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fifth Edition, criteria (American

*Department of Psychiatry, Çukurova University Medical School, Adana;†Şanlıurfa

Mehmet Akifİnan State Hospital, Şanlıurfa; ‡Dr Ekrem Tok Hospital for Mental

and Nervous Disease, Adana; and §Malatya Training and Research Hospital, Malatya, Turkey.

Send reprint requests to Lut Tamam, MD, Department of Psychiatry, Çukurova

University Medical School, Balcalı Hospital, Mithat Ozsan St, 01330 Sarıçam,

Adana, Turkey. E‐mail: ltamam@gmail.com.

Copyright © 2019 Wolters Kluwer Health, Inc. All rights reserved.

ISSN: 0022-3018/19/20708–0668

Psychiatric Association, 2013). All patients had had a diagnosis of schizophrenia for at least a year and had been treated on an inpatient or outpatient basis between October 15, 2018, and December 1, 2018. The study participants were grouped according to whether they had or had not attempted suicide in the past. Any actions intended to end life were accepted as suicide attempts. The suicide attempts were not separated according to whether they were violent or nonviolent. The same psychiatrist performed all the psychiatric interviews. Three patients who were illiterate, nine who refused to complete the study questionnaires, three who were intellectually disabled, and two with a cognitive deficit were excluded, leaving data for 113 patients available for analysis.

Power Analysis

We could not identify a study similar to ours in the literature, so we performed a pilot study with 10 subjects in each group. We calcu-lated statistics for the model in which the effect of psychache on suicide was assessed with depression as a mediator. We then tried to predict the sample size. In the power analysis, based on the findings of the pilot study, we calculated that a sample size of 18 subjects would be needed for 80% power and a 5% type I error rate. We performed a power anal-ysis using R version 3.5.2 for Windows (R Foundation for Statistical

Computing, Vienna, Austria) with the“powerMediation” package

de-veloped by Qiu and Qiu (2018). Using the same package, we repeated the power analysis in which descriptive statistics for coefficients and variables obtained in our study were used to test the role of depression as a mediator in the relationship between psychache and suicide. We in-cluded 113 patients in our study, and the Vittinghoff power result for the regression-based mediation test was 0.96 (Vittinghoff et al., 2009). These findings confirmed that our sample size had adequate power for this study. The study protocol was approved by the Noninvasive Clinical Research Ethics Committee of Cukurova University Medical School. All study participants provided written informed consent before partic-ipating in the study.

Measurements

All study participants completed the Psychache Scale (PAS), Beck Scale for Suicidal Ideation (BSSI), Calgary Depression Scale for Schizophrenia (CDSS), Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale

(PANSS), and Toronto Alexithymia Scale–20 (TAS), as well as a

socio-demographic data form that was prepared by the investigators. The sub-jects were allowed 30 minutes to complete the questionnaires, and any points that were not understood were explained by the interviewer.

Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale

This scale was developed to assess the positive and negative symptoms and general psychopathology and to measure the severity of symptoms in patients with schizophrenia and other psychotic disor-ders. It includes 30 items, each with a 7-point severity assessment. It is completed by the examiner (Kay et al., 1987). The safety and reliability

of the Turkish version have been confirmed (Kostakoğlu et al., 1999).

Calgary Depression Scale for Schizophrenia

The CDSS was developed to evaluate depression in patients with schizophrenia or other psychotic disorders and to measure the level and change in depressive symptoms. It consists of nine items each with four Likert-type choices (Addington et al., 1993). The validity and reliability of the Turkish version of the CDSS were investigated, and a cutoff point of 11 to 12 was recommended (Aydemir et al., 2000). In our study, a cutoff point of 11 was chosen.

Beck Scale for Suicidal Ideation

The BSSI was developed by Beck et al. (1979) and consists of five parts. The validity and reliability of the Turkish version have been confirmed (Hisli, 1988).

Toronto Alexithymia Scale–20

The TAS is a 20-item Likert-type questionnaire, and each item is scored from 1 to 5 (Bagby et al., 1994). The Turkish adaptation was de-veloped by Sayar et al. (2001). Alexithymia is thought to be absent in patients with a total score less than 51. Patients with scores in the range of 52 to 60 are accepted as possibly having alexithymia, and those with scores of 61 or higher are considered to have alexithymia (Sayar et al., 2001).

Psychache Scale

The PAS is a 13-item self-report scale developed by Holden et al. (2001). It is structured according to Shneidman's definition, that is, chronic, free-floating, context-independent psychache, which emerges in response to unmet vital mental needs. In this five-choice

Likert-type questionnaire, the answers range from“I definitely do not agree”

to“I definitely agree.” The PAS was found to differentiate between

pa-tients who did and did not commit suicide (Holden et al., 2001). The va-lidity and reliability of the Turkish version of the PAS have been confirmed (Demirkol et al., 2018).

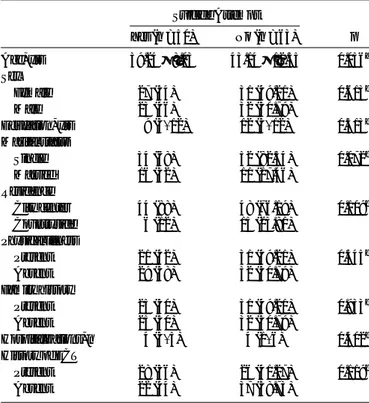

TABLE 1. Relationship Between Attempted Suicide and Demographic and Clinical Characteristics in Patients With Schizophrenia

Suicide Attempt Yes (n = 50) No (n = 63) p Age, yrs 39.24 ± 8.03 43.14 ± 12.35 0.056a Sex Female 27 (54) 31 (49.21) 0.613b Male 23 (46) 32 (50.79) Education, yrs 9 (5–12) 12 (5–12) 0.513c Marital status Single 34 (68) 52 (82.54) 0.072b Married 16 (32) 11 (17.46) Residence City center 44 (88) 48 (76.19) 0.109b Countryside 6 (12) 15 (23.81) Physical illness Present 21 (42) 31 (49.21) 0.445b Absent 29 (58) 32 (50.79) Family history Present 25 (50) 31 (49.21) 0.933b Absent 25 (50) 32 (50.79) Hospitalizations, n 4 (3–5) 4 (1–6) 0.402c History of ECT Present 28 (56) 26 (41.27) 0.119b Absent 22 (44) 37 (58.73)

ECT indicates electroconvulsive therapy.

aIndependent samples t-test (data shown as mean ± standard deviation).

b

Chi-square test; data shown as frequency (percentage).cMann-Whitney U-test;

Statistical Analysis

The study data are shown as the mean ± standard deviation or median and interquartile range depending on the distribution of the data. Categorical variables related to suicide attempts were summarized as the frequency and percentage and compared between the groups using the chi-square test. The independent samples t-test was used to compare the continuous variables when they were normally distributed, and the Mann-Whitney U-test was used when they were not normally distributed. The Pearson's correlation test was used to assess the rela-tionship between the scale scores obtained in the patients with schizo-phrenia when the data were normally distributed, and the Spearman's rho correlation coefficient was used when the data were not normally distributed. Univariate and multivariate logistic regression models were used to evaluate the risk factors for suicide. In these analyses, the effects of alexithymia, psychache, depression, and positive symptoms of schizo-phrenia on the likelihood of a suicide attempt (the dependent variable) were investigated. The effects of psychache and alexithymia on the risk of suicide in patients with depression were tested by mediation analysis. The bootstrap method (bootstrap 1000) was chosen, and the weighted least squares mean-variance adjusted parameter prediction method was used. Mediation analysis was performed to detect whether the external variable is a significant predictor of the internal variable without inclusion of the mediator variable in the analysis. The mediator was then added to the model, and the direct and indirect effects were assessed. Suicide was a cat-egorical variable, and the external variables and mediators were continu-ous variables in the analyses. The dependent variable, that is, suicide, consisted of two categories with similar rates. A critical p value of 0.05 was used to evaluate the pathway coefficients for all models. The statistical analyses were performed using the jamovi version 0.9 (jamovi project, 2018; https://www.jamovi.org) and MPLUS 7.4 programs. A value of p < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

RESULTS

The demographic features of patients with schizophrenia ac-cording to whether they had a history of attempted suicide are shown in Table 1. There was no significant between-group difference in age, sex, years of education, marital status, location of residence, medical history, family psychiatric history, number of hospital admissions, or history of electroconvulsive therapy (p > 0.05 for each variable).

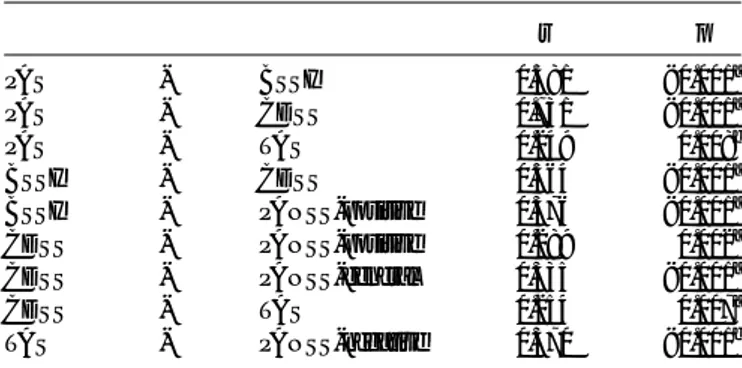

The PAS, BSSI, CDSS, PANSS, and TAS scores are compared according to whether there was a history of attempted suicide in Table 2. The mean PAS score was higher in the patients with schizophrenia and a history of attempted suicide than in their counterparts who had not attempted suicide (p < 0.001). Similarly, the median BSSI and CDSS scores were higher in patients with schizophrenia who had attempted suicide than in those who had not attempted suicide (both p < 0.001). The mean positive PANSS score was also higher in patients with schizo-phrenia who had attempted suicide than in those who had not (p = 0.038); no between-group difference in the mean negative PANSS score was found (p = 0.898). The mean TAS score was higher in the patients with schizophrenia who had attempted suicide than in those who had not (p = 0.045); however, when the TAS scores were categorized as absent, probable, or present and compared according to suicide attempts, the dif-ference between the mean values was statistically significant (p = 0.011). Alexithymia was more common (66%) in the group of patients with schizophrenia and a history of attempted suicide than in their counter-parts without a history of attempted suicide.

Table 3 shows the relationships between the scale scores ob-tained in the study subjects. There were moderately positive correla-tions in the same direction between the PAS and BSSI scores and between the PAS and CDSS scores (p < 0.001 for each analysis). In contrast, there was a weak positive but statistically significant correla-tion between the PAS total score and the TAS total score (p = 0.008). There was also a significant moderately positive correlation between the BSSI and CDSS scores and a significant weakly positive correlation between the BSSI and PANSS positive scores (both p < 0.001). There were also significant weakly positive correlations between the CDSS and PANSS positive, PANSS negative, PANSS general psychopathology, TABLE 2. Comparison of PAS, BSSI, CDSS, PANSS, and TAS Scores

According to Suicide Attempts in Patients With Schizophrenia

Score Attempted Suicide Yes (n = 50) No (n = 63) p PAS 37.6 ± 14.28 23.17 ± 10.64 <0.001a BSSI (total) 14 (7–19) 1 (1–2) <0.001b CDSS (total) 13 (7–14) 3 (0–7) <0.001b PANSS-positive 20.22 ± 7.42 17.27 ± 7.44 0.038a PANSS-negative 21.20 ± 7.48 20.95 ± 11.86 0.898a PANSS-general psychopathology 45.72 ± 15.93 38.46 ± 15.52 0.016a TAS 62.38 ± 9.52 57.89 ± 13.15 0.045a TAS (categorical) Absent 6 (12) 20 (31.7) 0.011c Probable 11 (22) 18 (28.6) Present 33 (66) 25 (39.7)

p values in bold are statistically significant.

aIndependent samples t-test (data shown as mean ± standard deviation).b

Mann-Whitney U-test; data shown as median (interquartile range).cChi-square test; data

shown as frequency (percentage).

TABLE 3. Relationship Between Scale Scores in Patients With Schizophrenia r p PAS - BSSI 0.581 <0.001a PAS - CDSS 0.731 <0.001a PAS - TAS 0.249 0.008b BSSI - CDSS 0.564 <0.001a BSSI - PANSS-positive 0.376 <0.001a CDSS - PANSS-positive 0.289 0.002a CDSS - PANSS-general 0.335 <0.001a CDSS - TAS 0.254 0.007a TAS - PANSS-negative 0.370 <0.001b

p values in bold are statistically significant.

a

Spearman's rho correlation coefficient.bPearson's correlation coefficient.

TABLE 4. Univariate and Multivariate Logistic Regression Analysis of Factors Affecting the Risk of Attempted Suicide

Univariate LR Model Multiple LR Model

Predictor OR (%95 CI) p OR (% 95 CI) p

PAS 1.086 (1.051–1.123) <0.001 1.048 (1.000–1.097) 0.049 CDSS 1.213 (1.122–1.311) <0.001 1.112 (0.999–1.237) 0.053 PANSS-positive 1.055 (1.002–1.111) 0.042 1.014 (0.954–1.079) 0.647

TAS 1.035 (1.000–1.070) 0.049 1.013 (0.975–1.052) 0.508

Dependent variable: suicide attempt. p values in bold are statistically significant. CI indicates confidence interval; LR, logistic regression; OR, odds ratio.

and TAS scores (p = 0.002, p < 0.001, and p = 0.007, respectively). There was a significant weakly positive correlation between the TAS and PANSS negative scale scores (p = 0.003 and p < 0.001, respectively).

Table 4 shows the results of the evaluation of risk factors for sui-cide in the univariate and multivariate logistic regression models. Sig-nificant effects of PAS, CDSS, PANSS positive, and TAS scores on the risk of a suicide attempt were seen in the univariate logistic regres-sion model (p < 0.001, p < 0.001, p = 0.042, and p = 0.049, respec-tively). However, multivariate logistic regression analysis revealed that only the PAS score was a significant independent predictor of a suicide attempt (p = 0.049), whereas the CDSS, PANSS positive, and TAS scores were not (p = 0.053, p = 0.647, and p = 0.508, respectively).

In the mediation analysis, we initially evaluated the mediating role of depression in the relationship between psychache and attempted suicide. In the analysis performed before the addition of depression to the model, psychache was found to have a significant positive effect

on the risk of suicide (β = 0.59; p < 0.001; R2= 0.34). Figure 1 is a path

diagram that demonstrates the mediating effect of depression on psychache and suicide, including standardized path coefficients and standard error values. The statistical data are shown in Table 5. Figure 1 shows that there was a significant positive relationship between the risk of a suicide attempt and the presence of psychache or depression. The effect in the pathway of psychache, depression, and suicide was positive

and significant (β = 0.23; p = 0.041). Furthermore, the relationship

be-tween psychache and suicide was significant (β = 0.36; p = 0.010). This

model explained 38% of the variance in suicide and 58% of the variance in depression.

In conclusion, there was a significant relationship between psychache and suicide before the addition of depression to the model (p < 0.001); however, after inclusion of depression (mediator), the

relationship was significant both directly (p = 0.010) and indirectly (p = 0.041). Therefore, depression was detected to have a partial medi-ating role in the relationship between psychache and suicide.

We also investigated whether depression mediated the relation-ship between alexithymia and suicide. Before the inclusion of depres-sion in the model, alexithymia was observed to have a significant

positive effect on suicide (β = 0.24; p = 0.039; R2= 0.06). The path

di-agram in Figure 2 demonstrates the mediating effect of depression on alexithymia and suicide and includes standardized path coefficients and standard errors. The statistical data are shown in Table 6. According to Figure 2, significant relationships were found between alexithymia and depression and between depression and attempted suicide; how-ever, there was no significant relationship between alexithymia and attempted suicide. This finding indicates that there were positive rela-tionships between alexithymia and depression, alexithymia and suicide, and suicide and depression. The indirect relationship between alexithymia, depression, and suicide was significant and followed a positive direction

(β = 0.12; p = 0.040). However, the direct effect of alexithymia on suicide

was not significant (β = 0.12; p = 0.274). The constructed model explains

35% of the variance in suicide and 4% of the variance in depression. In conclusion, we detected a significant relationship between alexithymia and suicide (p = 0.039) before inclusion of depression; however, after the addition of depression (as a mediator), this relation-ship was not significant directly (p = 0.274) but was significant indi-rectly (p = 0.040). Therefore, depression was identified to be a strong mediator in the relationship between alexithymia and suicide.

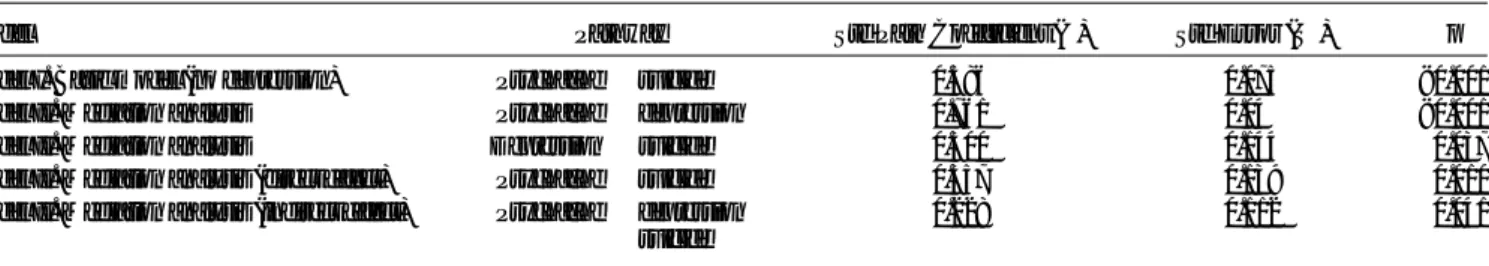

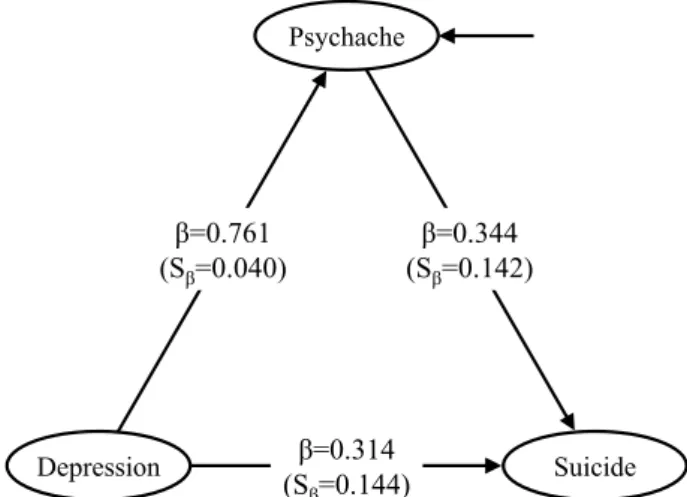

Next, we evaluated psychache as a mediator in the relationship between depression and suicide. The path diagram demonstrating this effect, including standardized path coefficients and standard errors, is shown in Figure 3. The corresponding statistical data are shown in TABLE 5. Mediating Effect of Depression on the Relationship Between Psychache and Suicide

Model Pathway Std Path Coefficient (β) Std Error (Sβ) p

Model I. Basic model (no depression) Psychache→ suicide 0.586 0.075 <0.001

Model II. Mediation analysis Psychache→ depression 0.761 0.04 <0.001

Model II. Mediation analysis Depression→ suicide 0.300 0.144 0.037

Model II. Mediation analysis (direct effect) Psychache→ suicide 0.357 0.139 0.010

Model II. Mediation analysis (indirect effect) Psychache→ depression

→ suicide 0.228 0.112 0.041

p values in bold are statistically significant.

FIGURE 1. Mediating effect of depression on the relationship between

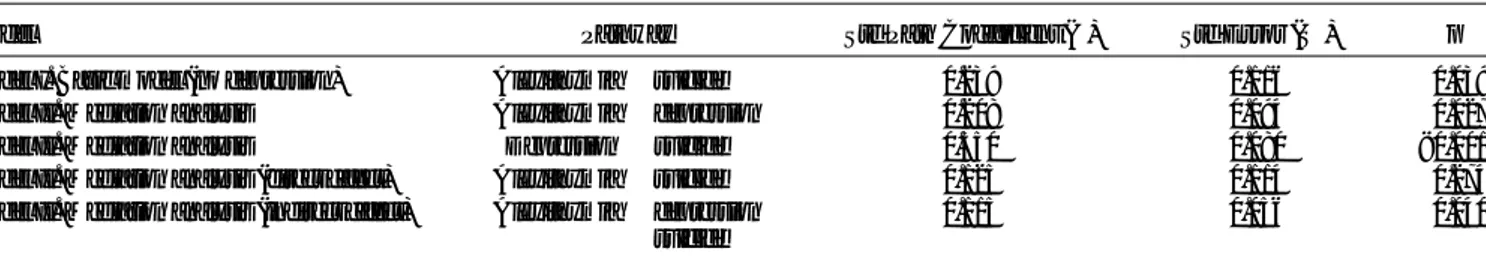

Table 7. The indirect effect in the pathway of depression, psychache,

and suicide was positive and significant (β = 0.26; p = 0.018), and

the direct effect between depression and suicide was significant

(β = 0.31; p = 0.029). This model explained 38% of the variance in

sui-cide and 58% of the variance in psychache.

In conclusion, there was a significant relationship between de-pression and suicide before the addition of psychache to the model (p < 0.001); however, after inclusion of psychache (as a mediator), both the direct (p = 0.029) and indirect (p = 0.018) relationships were signif-icant. Therefore, psychache was shown to be a partial mediator in the relationship between depression and suicide.

Finally, we found that alexithymia was not a mediator of the re-lationship between depression and suicide (data not shown).

DISCUSSION

The most important finding of this study was the association be-tween psychache and suicide in patients with schizophrenia. To the best of our knowledge, the concept of psychache has not been evaluated pre-viously in such patients. Shneidman (1993), who made important con-tributions to the concept of psychache, reviewed many suicide notes and reported that no suicide thoughts or attempts would be made with-out psychache. It was reported that persons who attempted suicide had high levels of psychache and could not tolerate this pain (Shneidman, 1993). In other studies, psychache was found to be strongly associated with suicide and with mood disorders and to be the result of unmet psy-chological needs (Verrocchio et al., 2016).

The association between psychache and depression has been demonstrated in other groups, including the homeless (Patterson and Holden, 2012). Psychache was also reported to be an independent risk factor for youth suicide (Levinger et al., 2015). In the validity and reli-ability study of the Turkish version of the PAS performed by our team, the mean PAS score in patients with a diagnosis of depression was 43.98 ± 11.43 (Demirkol et al., 2018). In the present study, the mean PAS score was 37.6 ± 14.28 in patients with schizophrenia who had attempted suicide and 23.17 ± 10.64 in their counterparts who had not. These data indicate that the PAS score can successfully differentiate

patients with schizophrenia into those who are likely to attempt suicide and those who are not.

Furthermore, there were positive correlations between the PAS, TAS, and CDSS scores, suggesting that psychache is associated with depression and alexithymia in patients with schizophrenia. We per-formed a mediation analysis based on a possible association between psychache, depression, and suicide in which we questioned whether psychache was a risk factor for suicide according to whether or not de-pression was present. According to our data, before the mediator (de-pression) was added to the model, there was a significant positive relationship between psychache and suicide. After the addition of de-pression, both direct and indirect effects were significant, indicating that depression had a partial mediating effect in the relationship be-tween psychache and suicide. Furthermore, multivariate logistic regres-sion analysis revealed that only the PAS score was independently associated with attempted suicide, which is consistent with the report by Shneidman (1993). Psychache also had a partial mediating effect in the relationship between depression and suicide and was also found to be a predictor of suicidal ideation in a recent 4-year follow-up study (Montemarano et al., 2018). That study concluded that psychache was the most prominent psychological concept for suicidal behavior and that other psychological factors were important in suicide only through their relationship with psychache (Montemarano et al., 2018).

The second important component of our study is the evaluation of the alexithymia concept in patients with schizophrenia. In a study that evaluated the relationship between alexithymia and suicide in these patients, the presence of alexithymia was found to lead to suicidal thoughts (De Berardis et al., 2017). However, in our country, Yurt (2006) could not find a difference between a group with alexithymia and a group without. In our study, alexithymia scores were significantly higher in the group that had attempted suicide. Alexithymia is fre-quently associated with depression. Van der Meer et al. (2009) reported that patients with schizophrenia had difficulty in identifying their emo-tions and that this was positively correlated with depression (Fogley et al., 2014). In a mediation analysis based on the hypothesis that alexithymia is associated with depression and suicide in patients with schizophrenia and the hypothesis that depression may mediate the TABLE 6. Mediating Effect of Depression on the Relationship Between Alexithymia and Suicide

Model Pathway Std Path Coefficient (β) Std Error (Sβ) p

Model I. Basic model (no depression) Alexithymia→ suicide 0.239 0.116 0.039

Model II. Mediation analysis Alexithymia→ depression 0.208 0.094 0.027

Model II. Mediation analysis Depression→ suicide 0.550 0.080 <0.001

Model II. Mediation analysis (direct effect) Alexithymia→ suicide 0.125 0.114 0.274

Model II. Mediation analysis (indirect effect) Alexithymia→ depression

→ suicide 0.115 0.056 0.040

p values in bold are statistically significant.

TABLE 7. Mediating Effect of Psychache on the Relationship Between Depression and Suicide

Model Pathway Std Path Coefficient (β) Std Error (Sβ) p

Model I. Basic model (no psychache) Depression→ suicide 0.575 0.077 <0.001

Model II. Mediation analysis Depression→ psychache 0.761 0.04 <0.001

Model II. Mediation analysis Psychache→ suicide 0.344 0.142 0.016

Model II. Mediation analysis (direct effect) Depression→ suicide 0.314 0.144 0.029

Model II. Mediation analysis (indirect effect) Depression→ psychache

→ suicide 0.261 0.110 0.018

association between alexithymia and suicide, it has been found that alexithymia was associated with depression and suicide and that de-pression may have a full mediator role in the relationship between alexithymia and suicide.

Anhedonia, loss of interest in social and physical activities, blunting of affect, and alogia are common features of the negative symptoms of schizophrenia and alexithymia. Therefore, it has been suggested that there is an association between alexithymia and the neg-ative symptoms of schizophrenia (Todarello et al., 2005). However, studies that have investigated this association have yielded conflicting results. In some studies, the total alexithymia score was found to in-crease in patients with schizophrenia and negative symptoms. More-over, patients with schizophrenia and deficit features were observed to be more alexithymic than those without deficit features (Nkam et al., 1997). In contrast, Todarello et al. (2005) concluded that alexithymia was not related to negative symptoms of schizophrenia and was an independent phenomenon. Maggini et al. (2002) reported that alexithymia was not related to the positive or negative dimensions of schizophrenia but was instead related to its depressive dimension. In our study, there was a positive correlation between alexithymia and the PANSS negative symptoms subscale score. Our data support the hy-pothesis that alexithymia and negative symptoms of schizophrenia are associated. This may be explained by the common symptomatology be-tween alexithymia and negative symptoms.

Risk factors identified in previous studies, that is, young age, male sex, being single, a high level of educational achievement, rural residence, presence of physical illness, and family history of suicide (Hor and Taylor, 2010), were also assessed in our study, but no signif-icant association was found between suicide attempts and these risk fac-tors. The absence of any association between the above-mentioned risk factors and suicide in our study may be explained by the fact that psy-chological factors such as psychache and alexithymia should be taken into account over and above sociodemographic data when assessing the risk of suicide in patients with schizophrenia.

A predominance of positive symptoms, such as delusions and auditory hallucinations, were found to be important risk factors in many studies of the association of disorder characteristics with the risk of sui-cide in schizophrenia (Hor and Taylor, 2010). However, some studies could not detect a relationship between positive and negative symptoms and suicide (Hawton et al., 2005). Comparison of patients who did and did not attempt suicide in our study showed that the mean Positive Syn-drome and the General Psychopathology subscale scores on the PANSS were higher in the group with previous suicide attempts. However, there was no significant difference between the groups in terms of negative

symptoms, which is consistent with the previous studies. We did not evaluate the types of delusions and hallucinations separately, and each one was accepted to be a positive symptom. Future studies that will evaluate the relationship between different types of delusions and sui-cide and between different types of hallucinations and suisui-cide sepa-rately may shed further light on this topic.

According to the hypothesis put forward by Fialko et al. (2006), positive symptoms alone did not predict suicide in patients with psy-choses. An affective response to delusions and hallucinations, depres-sive symptoms, and negative thoughts are other risk factors (Fialko et al., 2006). In the first episode in patients with psychosis, suicidal thoughts and plans, previous suicide attempts, and depressive symp-toms were the strongest determinants of suicide tendency (Bertelsen et al., 2007). Another study that evaluated the relationship between de-pression and suicide in patients with schizophrenia reported that the sui-cide risk increased with higher scores in depression scales (Fialko et al., 2006; Hor and Taylor, 2010). In our study, the mean CDSS score was significantly higher in those who attempted suicide and was above the cutoff point. Furthermore, the mean total BSSI score was higher in pa-tients with suicide attempts. The presence of a correlation between CDSS and PAS, BSSI, PANSS positive symptoms, and TAS suggests that depression may be closely related to other psychological factors in the pathway leading to suicide. These data demonstrate that in schizophrenia, attention must be paid to depressive symptoms, in addi-tion to psychotic symptoms, to predict and prevent suicide.

The limitations of this study are as follows. First, the categoriza-tion of suicide attempts as violent and nonviolent was absent, and con-sequently, the severity of suicide attempts could not be evaluated. Second, delusions and hallucinations were accepted as positive symp-toms, and their relationship with suicidal thoughts and previous suicide attempts was not evaluated separately. Third, although psychache, alexithymia, and negative symptoms of schizophrenia were found to be associated with each other, these findings were not supported by neuroimaging methods or tests for biological markers. Fourth, the cross-sectional design of this study may have produced bias in evaluat-ing mediation, which is a longitudinal process (Maxwell and Cole, 2007). We obtained data from measurements at a single time point and therefore performed cross-sectional analyses; the validity of our model was assessed by testing alternative models.

In the future, to shed further light on this subject, studies with larger sample sizes that separate cases with suicide as acute and chronic, evaluate the severity of suicide attempts, assess the relationships of de-lusion and hallucination types with suicidal thoughts and previous sui-cide attempts separately, and use neuroimaging methods and tests for biological markers will be required.

CONCLUSIONS

Suicide is an important cause of mortality in schizophrenia, and the concerning lack of a decrease in suicide rates during recent years de-spite increasing treatment options warrants novel perspectives for eval-uation of suicide cases. This study evaluated psychache in patients with schizophrenia and demonstrated that psychache might be associated with suicide attempts and current suicidal thoughts. In addition, this study showed that alexithymia might be associated with depression, sui-cide, and negative symptoms of schizophrenia. The findings herein suggest that psychache and alexithymia should be taken into consider-ation in evaluating the risk of suicide in patients with schizophrenia.

DISCLOSURE The authors declare no conflict of interest.

REFERENCES

Addington D, Addington J, Maticka-Tyndale E (1993) Assessing depression in

schizo-phrenia: The Calgary Depression Scale. Br J Psychiatry. 163:39–44.

FIGURE 3. Mediating effect of psychache on the relationship between depression and suicide.

American Psychiatric Association (2013) Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (DSM-5). Arlington, VA: American Psychiatric Association.

Aydemir Ö, Esen Danacı A, Deveci A, İçelli İ (2000) Reliability and validity of the

Turkish version of Calgary Depression Scale for schizophrenia [in Turkish].

Nöropsikiyatri Arş. 37:82–86.

Bagby RM, Parker JD, Taylor GJ (1994) The twenty-item Toronto Alexithymia Scale–I.

Item selection and cross-validation of the factor structure. J Psychosom Res. 38:23–32.

Bankier B, Aigner M, Bach M (2001) Alexithymia in DSM-IV disorder: Comparative evaluation of somatoform disorder, panic disorder, obsessive-compulsive disorder

and depression. Psychosomatics. 42:235–240.

Beck AT, Kovacs M, Weissman A (1979) Assessment of suicidal intention: The Scale

for Suicide Ideation. J Consult Clin Psychol. 47:343–352.

Bertelsen M, Jeppesen P, Petersen L, Thorup A, Øhlenschlaeger J, Le Quach P, Christensen TØ, Krarup G, Jørgensen P, Nordentoft M (2007) Suicidal behaviour and mortality in

first-episode psychosis: The OPUS trial. Br J Psychiatry Suppl. 51:s140–s146.

Blanchard EB, Arena JG, Pallmeyer TP (1981) Psychometric properties of a scale to

measure alexithymia. Psychother Psychosom. 35:64–71.

Bushe CJ, Taylor M, Haukka J (2010) Mortality in schizophrenia: A measurable

clin-ical endpoint. J Psychopharmacol. 24:17–25.

Campos RC, Holden RR (2016) Testing a theory-based model of suicidality in a

com-munity sample. OMEGA-J Death Dying. 74:119–137.

De Berardis D, Fornaro M, Orsolini L, Valchera A, Carano A, Vellante F, Perna G, Serafini G, Gonda X, Pompili M, Martinotti G, Di Giannantonio M (2017) Alexithymia and suicide risk in psychiatric disorders: A mini-review. Front Psychiatry. 8:148.

Demirkol ME, Güleç H, Çakmak S, Namlı Z, Güleç M, Güçlü N, Tamam L (2018)

Reliability and validity study of the Turkish version of the Psychache Scale [in

Turkish]. Anatolian J Psychiatry. 19:14–20.

Ducasse D, Holden RR, Boyer L, Artero SS, Calati R, Guillaume S, Courtet P, Olie E (2018) Psychological pain in suicidality: A meta-analysis. J Clin Psychiatry. 79: doi: 10.4088/JCP.16r10732.

Fialko L, Freeman D, Bebbington PE, Kuipers E, Garety PA, Dunn G, Fowler D (2006) Understanding suicidal ideation in psychosis: Findings from the psychological

pre-vention of relapse in psychosis (PRP) trial. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 114:177–186.

Fogley R, Warman D, Lysaker PH (2014) Alexithymia in schizophrenia: Associations

with neurocognition and emotional distress. Psychiatry Res. 218:1–6.

Hawton K, Sutton L, Haw C, Sinclair J, Deeks JJ (2005) Schizophrenia and suicide:

Systematic review of risk factors. Br J Psychiatry. 187:9–20.

Hisli N (1988) A study of the validity of the Beck Depression Inventory [in Turkish].

Psikol Derg. 6:118–122.

Holden RR, Mehta K, Cunningham EJ, McLeod LD (2001) Development and

prelim-inary validation of a scale of psychache. Can J Behav Sci. 33:224–232.

Hor K, Taylor M (2010) Suicide and schizophrenia: A systematic review of rates and

risk factors. J Psychopharmacol. 24:81–90.

Kay SR, Fiszbein A, Opler LA (1987) The Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale

(PANSS) for schizophrenia. Schizophr Bull. 13:261–276.

Kostakoğlu E, Batur S, Tiryaki A, Göğüs A (1999) The validity and reliability of

the Turkish version of the Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale (PANSS) [in

Turkish]. Türk Psikol Derg. 14:23–32.

Levinger S, Somer E, Holden RR (2015) The importance of mental pain and physical

dissociation in youth suicidality. J Trauma Dissociation. 16:322–339.

Maggini C, Raballo A, Salvatore P (2002) Depersonalization and basic symptoms in

schizophrenia. Psychopathology. 35:17–24.

Marasco V, De Berardis D, Serroni N, Campanella D, Acciavatti T, Caltabiano M, Olivieri L, Rapini G, Cicconetti A, Carano A, La Rovere R, Di Iorio G, Moschetta FS, Di Giannantonio M (2011) Alexithymia and suicide risk among patients with schizophrenia: Preliminary findings of a cross-sectional study [in

Italian]. Riv Psichiatr. 46:31–37.

Maxwell SE, Cole DA (2007) Bias in cross-sectional analyses of longitudinal

media-tion. Psychol Methods. 12:23–44.

Mee S, Bunney BG, Reist C, Potkin SG, Bunney WE (2006) Psychological pain: A

re-view of evidence. J Psychiatr Res. 40:680–690.

Montemarano V, Troister T, Lambert CE, Holden RR (2018) A four-year longitudinal study examining psychache and suicide ideation in elevated-risk undergraduates:

A test of Shneidman's model of suicidal behavior. J Clin Psychol. 74:1820–1832.

Motanİ, Gençöz T (2007) The relationship between the dimensions of alexithymia

and the intensity of depression and anxiety [in Turkish]. Turk Psikiyatri Derg.

18:333–343.

Nkam I, Langlois-Thery S, Dollfus S, Petit M (1997) Alexithymia in negative symptom and

non-negative symptom schizophrenia [in French]. Encephale. 23:358–363.

Orbach I, Mikulincer M, Sirota P, Gilboa-Schechtman E (2003) Mental pain: A

multidi-mensional operationalization and definition. Suicide Life Threat Behav. 33:219–230.

Palmer BA, Pankratz VS, Bostwick JM (2005) The lifetime risk of suicide in

schizo-phrenia: A reexamination. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 62:247–253.

Patterson AA, Holden RR (2012) Psychache and suicide ideation among men who are

homeless: A test of Shneidman's model. Suicide Life Threat Behav. 42:147–156.

Qiu W, Qiu MW (2018) Package‘powerMediation’. R Foundation for Statistical Computing.

Available at: https://cran.r-project.org/web/packages/powerMediation/powerMediation. pdf. Accessed December 20, 2018.

Saha S, Chant D, McGrath J (2007) A systematic review of mortality in schizophrenia: Is the differential mortality gap worsening over time? Arch Gen Psychiatry. 64:

1123–1131.

Sayar K, Güleç H, Ak I (2001) The validity and reliability of 20-item Toronto Alexithymia Scale. In 37th Turkish National Congress Book. Istanbul: Psychiatric Association of Turkey. In Turkish.

Shneidman ES (1993) Suicide as psychache. J Nerv Ment Dis. 181:147–149.

Shneidman ES (1996) The suicidal mind. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press. Shneidman ES (1999) The psychological pain assessment scale. Suicide Life Threat

Behav. 29:287–294.

Stanley IH, Hom MA, Rogers ML, Hagan CR, Joiner TE Jr. (2016) Understanding suicide among older adults: A review of psychological and sociological theories

of suicide. Aging Ment Health. 20:113–122.

Todarello O, Porcelli P, Grilletti F, Bellomo A (2005) Is alexithymia related to negative

symptoms of schizophrenia? Psychopathology. 38:310–314.

van der Meer L, van't Wout M, Aleman A (2009) Emotion regulation strategies in

pa-tients with schizophrenia. Psychiatry Res. 170:108–113.

van Heeringen K, Van den Abbeele D, Vervaet M, Soenen L, Audenaert K (2010) The

functional neuroanatomy of mental pain in depression. Psychiatry Res. 181:141–144.

Verrocchio MC, Carrozzino D, Marchetti D, Andreasson K, Fulcheri M, Bech P (2016) Mental pain and suicide: A systematic review of the literature. Front Psychiatry. 7:108. Vittinghoff E, Sen S, McCulloch CE (2009) Sample size calculations for evaluating

mediation. Stat Med. 28:541–557.

Yurt E (2006) [Alexithymia in schizophrenia patients: Negative symptoms, drug side

effects, relationship with depression and insight]. Dissertation. Bakırköy Mental

Health and Neurological Diseases Training and Research Hospital,İstanbul,