REPUBLIC OF TURKEY

SELÇUK UNIVERSITY

INSTITUTE OF SOCIAL SCIENCES

DEPARTMENT OF INTERNATIONAL RELATIONS

INTERNATIONAL RELATIONS

INDONESIA AND REGIONALISM IN SOUTHEAST ASIA:

ASEAN AND INDONESIAN FOREIGN POLICY

LUTHFY RAMIZ

MASTER’S THESIS

Supervisor

Dr. Öğr. Üy. Demet Şefika Mangır

ACKNOWLEDGEMENT

I owe gratitude to many people who have helped me and supported me thus far. Firstly, I wish to thank the Almighty God. It’s His guidance that has helped me to go through my academic life since day one and to finish this thesis paper. Secondly, I would like to thank my mother, Moelyanti S. Oemar; my father, Lambang Patria; and my sister, Nadhira Ramiz. If their support and belief were not exist, I would not be here and finish this thesis.

Üçüncüsü, Sayın Dr. Ögr. Üy. Demet Şefika Mangır hocama, tüm akademik ve tez hazırlanması sürecinde bana verdiği yardım ve destek için teşekkür etmeyi bir borç bilirim. Dördüncüsü, bana gösterdiği arkadaşlık için benim kardeşim Furkan Has'a teşekkür etmek istiyorum. Herkese teşekkürler.

Lastly, I would like to thank my family in Konya. Ade Sumiahadi, Faqiih Muhsin, Shah Firizqi Azmi, Adli Hazmi, Enes Pucurica, Mawaddah, Saras Alfiasari, Tsabita Siti Rahmah, Gesta Nurbiansyah, Afina Sholihat, Farhan Ismail, Haryono, Sonia Dwita, Dara Nazura Darus, Qori Ananda, and Firkrihawaary. Thank you for your push and supports. Words can not express my gratitude.

Luthfy Ramiz 17 June 2019 Konya, Turkey

T. C.

SELÇUK ÜNİVERSİTESİ Sosyal Bilimler Enstitüsü Müdürlüğü

ÖZET

Güneydoğu Asya'da bölgeselcilik ve bölgeselleşme sürecinde Endonezya'nın rolü konusundaki araştırmalar, çağdaş bölgeselci örgütlenmenin ortaya çıkmasından önce bile Güneydoğu Asya'daki entegrasyon sürecinin değerlendirilmesiyle sonuçlanmaktadır. Bu çalışmadaki araştırma, sömürge öncesi, sömürgecilik ve ASEAN dönemlerinde Güneydoğu Asya'da bölgesel entegrasyon sürecini kapsamaktadır. Ayrıca, diğer Güneydoğu Asya ülkeleri arasındaki önemli göreceli gücü göz önüne alındığında, Endonezya'nın dış politikaları ve bölgesel entegrasyon sürecine katkısı önemli bulunmuştur. Araştırma, literatürlerin değerlendirilmesi, uzmanların yorumları ve araştırma konularıyla ilgili anlaşma ve protokollerin değerlendirilmesi yoluyla nitel araştırma yöntemi kullanılarak gerçekleştirilmektedir. Araştırma dört önemli sonuç çıkarmaktadır; Güneydoğu Asya'da bölgeselcilik dinamikleri, Güneydoğu Asya kimliğinin teorik yapısı, Güneydoğu Asya'da bölgeselciliğin teorik değerlendirmeleri ve Güneydoğu Asya'da bölgeselleşmeye yönelik Endonezya dış politikasının teorik değerlendirmeleri.

Anahtar Terimleri: Bölgeselcilik, ASEAN ve Endonezya.

Ö ğr en ci ni n

Adı Soyadı Luthfy RAMIZ

Numarası 144229001021

Anabilim/Bilim Dalı Uluslararası İlişkiler Programı Tezli Yüksek Lisans

Tez Danışmanı Dr. Öğr. Üy. Demet Şefika Mangır

Tezin Adı Endonezya ve Güneydoğu Asya Bölgeselciliği: ASEAN ve Endonezya Dış Politikası

T. C.

SELÇUK ÜNİVERSİTESİ Sosyal Bilimler Enstitüsü Müdürlüğü

ABSTRACT

The research towards the regionalism in Southeast Asia and Indonesian role within the regionalism process is concluded through the assessment of integration process in Southeast Asia even prior to the emergence of the contemporary regionalist organization. The research in this paper covers regional integration process in Southeast Asia during the pre-colonial, decolonization and ASEAN periods. Moreover, foreign policies and contribution of Indonesia towards the regional integration process is found important, considering its significant relative power among the other Southeast Asian states. Research is conducted using the qualitative research method through the assessment of literatures, commentaries from the experts, and the agreements and protocols relevant to the research topics. The research concludes four important results; the dynamics of the regionalism in Southeast Asia, the theoretical construction of Southeast Asian Identity, theoretical assessments of regionalism in Southeast Asia and Indonesian foreign policy towards regionalism in Southeast Asia.

Key terms: Region, Regionalism, ASEAN and Indonesia.

Ö ğr en ci ni n

Adı Soyadı Luthfy RAMIZ

Numarası 144229001021

Anabilim/Bilim Dalı Uluslararası İlişkiler Programı Tezli Yüksek Lisans

Tez Danışmanı Dr. Öğr. Üy. Demet Şefika Mangır Tezin İngilizce Adı

Indonesıa and Regıonalısm in Southeast Asia: ASEAN and Indonesian Foreign Policy

ABBREVIATIONS

AANZFTA ASEAN-Australia and New Zealand Free Trade Area

ACFTA ASEAN-China Free Trade Area

ACI ASEAN Committee in Islamabad

ACIA ASEAN Comprehensive Investment Agreement

ACP African, Caribbean and Pacific

ACCT ASEAN Convention on Counter Terrorism

ADMM ASEAN Defense Minister Meeting

AEC ASEAN Economic Community

AEM ASEAN Economic Ministers

AFAS ASEAN Framework Agreement on Services

AFAVE ASEAN Framework Agreement on Visa Exemption

AFTA ASEAN Free Trade Area

AGDPC ASEAN-Germany Development Partnership Cooperation

AHRD ASEAN Human Rights Declaration

AICHR ASEAN Intergovernmental Commission on Human Rights

AICO ASEAN Industrial Cooperation

AIFTA ASEAN-India Free Trade Area

AJCEP ASEAN-Japan Comprehensive Economic Partnership

AKFTA ASEAN-Korea Free Trade Area

ANJSCC ASEAN-Norway Joint Sectoral Cooperation Committee

APEC Asia-Pacific Economic Cooperation

APJSCC ASEAN-Pakistan Joint Sectoral Cooperation Committee

APSC ASEAN Political-Security Community

APT ASEAN Plus Three

ARISE ASEAN Regional Integration Support from EU

ASA Association of Southeast Asia

ASCC ASEAN Socio-Cultural Community

ASEAN Association of Southeast Asian Nations

ATJSCC ASEAN-Turkey Joint Sectoral Cooperation Committee

CBM Confidence Building Measure

CCI Coordinating Committee on Investment

CER Closer Economic Relations

CPB Communist Party of Burma

E-READI Enhanced Regional EU-ASEAN Dialogue Instrument

EU European Union

FDI Foreign Direct Investment

HUKBALAHAP Hukbo ng Bayan Laban sa Hapon (People’s Army Against the

Japanese)

ICP Indonesian Communist Party

MCP Malayan Communist Party

MNP Movement of Natural Person

MRA Mutual Recognition Arrangements

NAM Non-Aligned Movement

NARIP Norway-ASEAN Regional Integration Programme

NATO North Atlantic Treaty Organization

NEFOS New Emerging Forces

OEEC Organization for European Economic Cooperation

OLDEFOS Old Established Forces

PDFP People’s Democratic Front Party

SEATO Southeast Asia Treaty Organization

TAC Treaty of Amity and Cooperation

UNCLOS United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea

UNDP United Nations Development Programme

USAFFE United States Army Force in the Far East

LIST OF TABLES

Table 1: Dialogue Partners of ASEAN 61

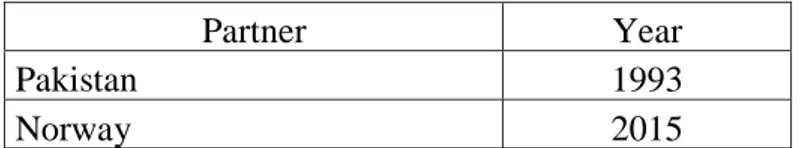

Table 2: Sectoral Dialogue and Development Partners of ASEAN 66

Table 3: ASEAN Trade with Selected ASEAN Interregional Partners 74

LIST OF ANNEXES Annex 1: Southeast Asia Collective Defence Treaty 1954 Annex 2: Manila Accord 1963

Annex 3: Manila Declaration 1963 Annex 4: Bangkok Declaration 1967

Table of Contents

Bilimsel Etik Sayfası i

Tez Kabul Formu ii

Acknowledgement iii

Özet iv

Abstract v

Abbreviations vi

List of Tables viii

List of Annexes ix

Chapter 1: Theoretical and Conceptual Framework 1

1.1 Background 1 1.2 Aims 3 1.3 Importance 3 1.4 Research Method 4 1.5 Research Questions 4 1.6 Theoretical Framework 5

1.7 Key Concept and Literature Review 8

1.7.1 Concept of Region 8

1.7.2 Concept of Regionalism 9

1.7.3 Concept of Interregionalism 10

1.8 Conclusion 12

Chapter 2: Regionalism of Southeast Asia and Indonesia: Earlier Periods 13

2.1 Earlier Southeast Asia 13

2.1.1 State Relations in Pre-colonial Period 13

2.1.2 Decolonization Period and Cold War 14

2.2 Earlier Southeast Asian Regional Institutions 19

2.2.1 SEATO 19

2.2.2 ASA 22

2.2.3 MAPHILINDO 25

2.3 Earlier Indonesia 27

2.3.2 Post-Independence Period: The ‘Bebas-Aktif’ Policy 28 2.3.3 Post-Independence Period 2.0: The Confrontation Policy 30 2.3.4 Post-Independence Period 3.0: ‘New Order’ Era – Now 31

2.4 Conclusion 33

Chapter 3: ASEAN and Contemporary Regionalism in Southeast Asia 35

3.1 ASEAN Basic Information 35

3.1.1 ASEAN Establishment 35

3.1.2 ASEAN Membership and Expansion 35

3.1.3 Machinery and Organs of ASEAN 36

3.2 ASEAN Way 39

3.2.1 ASEAN Way: An approach to regionalism 39

3.3 ASEAN Regionalist Policy 41

3.3.1 ASEAN Community 41

3.3.2 ASEAN Political-Security Policy 42

3.3.3 ASEAN Socio-Economic Policy 48

3.4 ASEAN Inter-regional Policy 55

3.4.1 ASEAN Regional Forum 55

3.4.2 ASEAN+3 56

3.4.3 East Asian Summit 57

3.4.4 Free Trade Areas 58

3.4.5 Dialogue Partnerships 61 3.4.5.1 ASEAN-UNDP 62 3.4.5.2 ASEAN-Japan 62 3.4.5.3 ASEAN-ANZ 62 3.4.5.4 ASEAN-EU 63 3.4.5.5 ASEAN-Canada 63 3.4.5.6 ASEAN-United States 64 3.4.5.7 ASEAN-South Korea 64 3.4.5.8 ASEAN-India 65 3.4.5.9 ASEAN-China 65 3.4.5.10 ASEAN-Russia 66

3.4.6.1 ASEAN-Pakistan 67 3.4.6.2 ASEAN-Norway 67 3.4.6.3 ASEAN-Switzerland 68 3.4.6.4 ASEAN-Turkey 68 3.4.6.5 ASEAN-Germany 69 3.5 Conclusion 69 Chapter 4: Discussions 71

4.1 Discussion 1: The “Southeast Asian Identities” 71

4.2 Discussion 2: Theoretical understanding of ASEAN Regionalism 72 4.3 Discussion 3: Theoretical understanding of Indonesia’s policy towards

regionalism in Southeast Asia 76

4.4 Conclusion 78

Conclusion 80

CHAPTER 1

THEORETICAL AND CONCEPTUAL FRAMEWORK 1.1. Background

Historical research towards the concept of regionalism has found that the world has witnessed the emergence of regionalism concept since the late of 19th century. Some of the initial remarks of the emergence of regionalism in the international politics stage were the pan-Americanism and pan-Arabism. The emergence of the idea of regionalism during the pan-Americanism period had pushed through the ideas of sovereignty and freedom of the region from the colonialism (Fawcett 2012: 8). Pan-Arabism was initially a consequence of the awakening of Arab identity and their history during the Ottoman Empire period (Danielson, 2007: 20).

Regionalism eventually developed even further during the late 19th century to the 20th

century. In the 19th century, of which took place within the case of pan-Americanism, the idea of regional sovereignty had proceeded to the international treaties in the years of 1856 and 1899. Meanwhile, the 20th century is believed to be the beginning of the contemporary regionalism study. The establishment of international institutions which led to the newly established parameters of regional and multilateral relationship and the post-colonialism period are the factors responsible to the significant development of regionalism concept in the 20th century (Fawcett 2012: 8).

Considering the fact that regionalism has gone through significant development these days, the topic is brought up to be assessed deeply in this research. Research is carried out in a manner of assessing the development of regionalism to specific region, which is Southeast Asia. The research also assesses the role of big power in Southeast Asia within the process of regional integration in the region, in which Indonesia as single regional power in Southeast Asia is assessed in this research.

Regionalism has taken place globally. It had arisen not only in America, Europe and Middle East but also in formerly long colonised regions, such as Southeast Asia. Regionalism in Southeast Asia had arisen after the most of the important actors in Southeast Asia were freed from colonialism.

Regionalism in Southeast Asia was initially rooted from the Cold War occurence (Weber, 2009: 4). The fierce ideological rivalry between liberalism and communism during the Cold War was the significant player when it comes to the motive of the growth of regionalism in Southeast Asia. This ideological rivalry had moved the United States to tackle

the growth of communism through establishing regional organization, which at the same time this establishment policy also promoted regionalism in Southeast Asia. Eventually, Southeast Asia Treaty Organization [hereafter: SEATO] was established in the year 1954. However, SEATO was disbanded in the year 1977.

Regionalism has grown in Southeast Asia unanimously with the establishment of Association of Southeast Asia [hereafter: ASA], MAPHILINDO and Association of Southeast Asian Nations [hereafter: ASEAN] in the 1960’s. ASA was established in the year 1961 and three years after the establishment of ASA, MAPHILINDO was established in the year 1963. Meanwhile, ASEAN was established in the year 1967.

ASEAN has grown to be one of the most contributive instruments for Southeast Asia in shaping regionalism in the area, if not the most significant instrument. For this hypothesis to be proven, it is obligatory for us to see that Southeast Asian states have consolidated its regional political maneuvers through ASEAN policies since the first inception of organization. Some of them include the Bangkok Declaration 1967, Declaration of Zone of Peace, Freedom and Neutrality 1971 [hereafter: ZOPFAN Declaration], Treaty of Amity and Cooperation in Southeast Asia 1976, ASEAN Concord 1976, ASEAN Free Trade Area 1992 [hereafter: AFTA], Southeast Asian Nuclear Weapon Free Zone Treaty 1995 [herafter: Bangkok Treaty 1995], Declaration on Joint Action to Counter Terrorism 2001 [hereafter: Bandar Seri Begawan Declaration 2001] and Charter of Association of Southeast Asian Nations 2007 [hereafter: ASEAN Charter].

It is indeed presumable that the root of regionalism in Southeast Asia is attributed to the existence of regional organization such as ASEAN, or the regional cooperation of such kind existed before ASEAN. However, each of single state in Southeast Asia is also attributable to the birth of regionalism in this region. As it is written in the ASEAN Charter on the Article (2), Paragraph (2) and Letter (b), each member subjects to collective responsibility to enhance security and prosperity in the region.

The role of the regional power in Southeast Asia in the formation and development of regionalism in the region is assessed through examining the foreign policy of Indonesia. First of all, regional powers’ significant role in the process of regional integration is visible in numbers of regionalism scheme, such as the roles of United States and Brazil in the formation of regional integration in the Americas and Germany in the European Union. Both United States and Brazil have had strong economic integration policy during the consolidation of the Free Trade Area of the Americas (Toru, 2004: 2-4) and Germany played significant role in the formation of European Economic and Monetary Union (Bulmer, 2015: 14-18).

Historically, Indonesia has taken quite significant position in the diplomatic world in Asia. Indonesia was one of the organizers of the Bandung Summit in the year 1955, more specifically in Southeast Asia Indonesia was part of MAPHILINDO and is one of the founding states of ASEAN in 1967.

Indonesia tops the rank among other ASEAN members in regards of area and population. Security wise, Indonesia possesses the largest military power in the region (Normala, 2018). Meanwhile economic wise, Indonesia is ranked first in GDP among whole ASEAN members and has taken its position as the second most attractive location for transnational company in ASEAN and the second biggest in terms of foreign direct investment flow in the region, while the first one being Singapore in both category (Artner, 2018: 20). If the term regional power is defined to have high influence in regional affairs (Neumann, 1992: 12), Indonesia is indeed a regional power in the region.

1.2 Aims

The aims of the research are to assess the regionalism in Southeast Asia and to assess the role of Indonesia as the regional power in shaping the regional integration in Southeast Asia. Assessment of regionalism in Southeast Asia is important to observe regional integration process from the initial formation process to the current state of regional integration in the region. Moreover, assessment of the role of Indonesia as the regional power in Southeast Asia is important to determine the influence of bigger power in the region within the regional integration process. The research is furtherly aimed to provide certain bases to the conduction of the similar researches in regionalism in the future.

1.3 Importance

The importance of the research on the regionalism is visible on the juxtaposition of the theoretical framework of regionalism and the regionalism process. Regionalism in Southeast Asia is considered unique for its distinctive elements which construct the regional integration process. These distinctive elements are comprised of the unique identities, mechanism, et

cetera, which might not be found in other regional integration processes in other region. The

assessment in a manner of juxtaposing the theoretical framework to the Southeast Asian regionalism process and its unique elements is important to draw ideas on the variety of regional integration process in the field of international relations.

1.4. Research Method

Qualitative research method is used to analyze “Regionalism in Southeast Asia and Policy in Indonesia and ASEAN”. The research relies on the scientific literatures on this topic. The source includes books, academic articles, journals, scientific reports, periodicals and policy briefs, published by think tanks and other policy institutions. Furthermore, the commentary of experts, politicians, academicians, diplomats, news sources and the protocols and agreements relevant to this matter are also utilized.

In general, the research assesses the theoretical and conceptual framework regarding the regionalism, and the policies of regional integration in Southeast Asia and Indonesia. Moreover, it discusses the application of the theoretic frameworks in the policies within the process of regional integration in Southeast Asia and Indonesia.

The research is divided into five parts. Firstly, assessment of the theoretical and conceptual framework of regionalism, afterwards General framework of regionalism in Southeast Asia and Indonesia is assessed, and on the third part the regionalism process in Southeast Asia through the framework of ASEAN is assessed and it is followed by the discussion towards the research questions on the fourth part before the research is concluded.

1.5 Research Questions

In order to assess the regionalism in Southeast Asia and to assess the role of Indonesia as the regional power in shaping the regional integration in Southeast Asia, there are four research questions. The questions are:

1. How does regionalism in Southeast Asia develop? 2. What are the “Southeast Asian Identities”?

3. How do we assess the theoretical understanding of ASEAN Regionalism?

4. How do we assess the theoretical understanding of Indonesia’s policy towards regionalism in Southeast Asia?

1.6 Theoretical Framework

In order to construct theoretical framework, it is important to divide the emergence of integration and the integration mechanism. Constructivism and realism theories are used in order to analyze the emergence of regionalism in Southeast Asia

In order to analyze the occurrence of regionalism process, constructivism theory takes consideration of identity, social conventions and behaviors of states. Thus this theory is seen as the suitable approach as it emphasizes the motives of the formation of regionalism (Börzel, 2016: 43-44).

Constructivism Theory in international relations has emerged since the end of the Cold War. Alexander Wendt and Peter Katzenstein are deemed to be the pioneers in popularizing this theory. Generally, constructivist sees the importance of the states’ identity and interests in constructing the system in which states’ action takes place (Wendt, 1994: 385).

Three significant elements in constructivism are norms, identity, and interest. The compatibility of identity of a state and its action is guided by norms. Thus norm holds important position on the eye of constructivists. Constructivists define norms as the standards in guiding the action of a state and its identity (Katzenstein, 1996: 5). Moreover, the corelation between norms, identity, policies, and international communities are elaborated as: internal and external norms shape identity of a state, which identity shapes normative structure of a state, and composition of identities shapes the international community (Jepperson, et al., 1996; Katzenstein et. al., 1996: 52-53; Cho, 2009; 81).

Realism-intergovernmentalism and institutionalism approaches are taken into account when explaining the regionalism of Southeast Asia. Intergovernmentalism theory has its root from the realism school of thought. While realism school of thought can be traced back to its first emergence in the late 1500s through Hugo Grotius.

Realism theory features six important pointers. These pointers are: 1) Political laws are originated from human nature; 2) Main idea of realism is interests that are defined in terms of power that depends to the political and cultural context and includes anything that maintains control over human; 3) Rational alternatives are to be preferred when finding resolutions in the actual circumstances; 4) The ethics in politics judge action by the consequences; 5) The rejection to the idea that mentions the moral law governs the universe and 6) Political realists maintain the autonomy of political sphere (Morgenthau, 2006; Chen, 2011: 27).

Realism theory comprises three important feature; anarchy, state, and rational decision making (Antunes & Camisao, 2017; 15). Anarchism represents the absence of supreme role in

international politics. Moreover, state represents its sole power as the actor of international politics. Through the necessity to achieve their interest, state carries out action. States have necessity for security in response to the anarchic structure and to the unbalanced power (Williams, et. Al, 2006; Chen 2011: 27-28). Thirdly, rational decision making is carried out by the state to minimize harm to the interest.

Research towards the role of Indonesia as regional power in shaping regional integration in Southeast Asia can be based on the realists’ view in the formation of international cooperation. Realists see the importance of the existence of a bigger power in order to establish international cooperation with stable norms, rules and procedures (Cho, 2009; 78). In connecting the state and its interests, the norms, rules and procedures are the products of the adjustment to the hegemonic state’s interests.

Neo-realism eventually gives more elaborated explanation of power balance in the integration process. The proper combination of international politics is the existence of balance of two big powers (Bell & Duignan, 2017). Moreover, the facts that states have capability in security aspect, big power could be a threat to security at any time and anarchism has given states no guarantee of security have pushed the states seek power in order to protect. This led to a formation of cooperation, which is deemed as the solution (Ngan, 2016: 2-3).

Intergovernmentalism is a sub-theory of realism theory that is used in analyzing the regionalism in Southeast Asia. Intergovernmentalism theory first emerged in the 1960s with Stanley Hoffman as one of the initiators of the early thoughts of the theory. The idea which Hoffman conveyed was that instead of political sector, economics sector could be one success story within European integration process (Hoffmann, 1966; Obydenkova, 2011: 90).

Prominent feature of intergovernmentalism is that it sees regionalism as the integration and bargaining process between national governments in particular region (Moravcsik, 1991; Yoshimatsu, 2008: 63). Intergovernmentalism sees integration process as the feature where governments of the member state are authorized to determine the processes of the integration; such as the substance and speed of integration (Schimmelfenning & Rittberger, 2006: 77-78). Process of bargaining towards integration in intergovernmentalism theory is based on the state preferences. State preferences are seen distinct between liberal intergovernmentalism and realist intergovernmentalism. Liberal intergovernmentalism, or neofunctionalism, sees the state preference to be sector-specific (Schimmelfenning & Rittberger, 2006: 77-78). In this case, the preferences are mostly in economic sector and domestic preference based on internal demands (Coşkun, 2015: 388). On the other hand, realist intergovernmentalism sees the state

preference to be based on the concern of their own autonomy and influence (Schimmelfenning & Rittberger, 2006: 78).

The element of supranationalism, that mostly presents in neofunctionalism theory, is absent in this theory (Rosamond, 2000: 141). Contrary to the importance of institution in upholding integration process in supranationalism, the role of institution in intergovernmentalism theory holds fewer importance. Although it may also be existing within the integration process. The role of institution in the regional integration process according to intergovernmentalism theory is to bind the member states through international agreements (Sweet & Sandholtz, 1997: 301). Moreover, the role supranational institution is limited in supervising the regional interaction and the daily affairs of the region (Yang, 2014: 7).

Intergovernmentalism emphasizes the relative power of states and power of largest states in the region (Yoshimatsu, 2008: 64). Each state in any particular regions has different relative power. States with smaller power might possess less influential position whilst bigger powers possess more influential position. Emphasis of power exists in this theory is correlated to the bargaining process as the key variable to this theory. Interaction between member states depends on the relative power of states and states with biggest power might have the most significant influence to the outcome of the bargaining among other states (Eliassen & Arnadottir, 2016; Telo, 2014: 243).

Institutionalism theory is rather extensive, as it has evolved to neo-institutionalism and neo-liberalist institutionalism. Instutionalism features five prominent characters; these characters are legalist, structuralist, holicist, historicist, and normative (Peter, 1999: 7-11). The view on institutionalism as legalist is attributable to centrality of law in the carrying out the governing function (Peter, 1999: 7). Then, the theory is considered structuralist as it is formal, or is based on constitutional arrangement (Peter, 1999: 8). Consideration of holism of institutional theory is attributable to its holistic analysis of the systems, and it refrains from analyzing particular system partially (Peter, 1999: 9). Moreover, historicist character of this theory is visible through the history-based analysis that most of institutionalists carry out. Institutionalists see how the contemporary system is presence in the history, and in the status

quo of political, socioeconomic and cultural aspects (Peter, 1999: 10). Finally, institutionalism

theory’s emphasis on the norms and values has shown the source of the normative side of institutionalism theory (Peter, 1999: 11).

Evolvement of institutionalist view is known to be neo-institutionalism. Institution plays significant role in conceiving order, and the robust foundation to the individuals and surroundings (Olsen, 2007: 3). Institution is central in providing the ideational norms and

resources to individuals (Bell, 2002: 3). Furthermore, foundation of a robust regional community is a strong institution, as institution plays its role as the game’s ruler and it connects the members of the community and their action (Rattanasevee, 2014: 1). Rule is followed for its proper “guide” and “validity” (Bell, 2002: 3).

Neoliberal approach of neo-institutionalism theory is used when evaluating the establishment of institution. Neoliberal institutionalism sees institution is established to accommodate states’ interdependence and interaction towards each other in acting for its interest and achieving maximal utility (Jonsson & Tallberg, 2001: 5). This is supported by the view that sees the formation of institution is a way-out in solving the coordination, collaboration and governance cost problems of states (Stein, 2008: 208-209).

1.7 Key Concept and Literature Reviews 1.7.1 Concept of Region

There is no consensual definition of regionalism (Mansfield & Stolingen, 2010: 146). Moreover, to understand the root of the absence of consensus in the definition of regionalism is to understand that there is no agreement on what variables constituting region are (Mansfield & Stolingen, 2010; Mansfield & Milner, 1997: 3).

Although no agreement is reached when elaborating the variables of a region, scholars had previously explained their views. One of the most important variables in the concept of region is geography (Palmer, 1991: 6). Indeed geographical proximity is the most general variable in elaborating the concept of region. As we can see this fact that current most classifications of region are based on their geographical proximity, such as Europe, North America, Central America, East Asia and Southeast Asia. However, some argued that region is not only about geographical feature but also the dynamics of political practices and institutions (Katzenstein, 2005: 12). Furthermore, Volgy and Rhamey in their work (Volgy & Rhamey, 2014: 6) have adopted the concept of region as the group of states with the geographical proximity whose political, economic and cultural interaction patterns are similar.

Other understandings of region interconnect natural and social elements. Haggett in his work (Haggett, 2001) have explained that concept of region is a result of relationship between natural and social elements. Moreover, assumption of region as socially made classification is made clear by some of the view that sees interconnection between states in a region in the regards of economy (Deutsch, ed., 1957; Mansfield & Stolingen, 2010: 6), culture (Paul, 2012: 4), and communal identities of states of a region (Mansfield & Stolingen, 2010; Buzan & Waever, 2003: 48) as the other variables.

Defining the concept of region from the cultural perspective, community and their social and cultural elements play important role in drawing a region. Socio-cultural perspective sees region as a space formed by the socio-culture aspect and particular community (Hubik, 2002: 94). These views had seemed to be the examples of the shift of the assumption that sees region is a naturally made classification to socially made classification.

1.7.2 Concept of Regionalism

Historically, the term regionalism had been used to describe the opposition movement in particular region against the power of hegemony. The terms ‘Regionalismo’ and ‘Regionalisme’ were used in Italy and France in 19th century, respectively. The term

‘Regionalismo’ was frequently used to describe the attempt of opposition of Piedmont centralism to preserve the variety of autonomous provincial government from centralization policy imposed during the Italian unification period and the another term was used to represent the attempt to turn over the central French government hegemony by French writers and poets in Southern France (Hebbert, 1987: 240).

The term regionalism often appears in studies related to regions and regional integration nevertheless the term keeps developing therefore regionalism has no consensual definition. The definition of regionalism may vary based on the point of view of the expertation. Regionalism is essentially defined as cooperative projects, intergovernmental dialogues and treaties (Breslin & Higgott, 2000; Ganesan & Amer, 2010: 13). Meanwhile Nye in his work (Nye, 1968: vii) has defined defines regionalism as formation of and policies pursued by inter-state groups based around regions. In short, regionalism is seen as a process of cooperation among States, with additional elaboration on the aim of the cooperation, which is to pursue national interest based on particular geographical proximity. Some other experts also view regionalism as a process undertaken by states of the close geographical proximity to pursue their interests, as Joseph Nye did (Alagappa, 1995: 362; Hidetaka & Yoshimatsu, 2008: 7).

Regionalism has also defined as an institutionalized political coalition process. Vayrynen in his work (Vayrynen, 2004: 6; Tavares, 2004: 6) has defined regionalism as an institutionalized intergovernmental coalition that control access to a region. Political wise, regionalism is understood as manifestation of regional administrative planning and prioritization of regional interest above national interest (Juliao, 2018). Therefore, the regional institution is deemed to have implications to each single state in the region (Tostes, 2013: 395). Moreover Pempel, Barry and Keith in their work (Pempel, 2005: 19-20; Barry &

Keith, 1999: 3) have specified the aim of the coalition, which is claimed to be pursuing trade benefits. This view is somehow accepted, and regionalism as a tool of trade benefits process is commonly seen as regionalism’s definition in the economical point of view.

Regionalism is also defined from the point of economical expertation. Mattli in his work (Mattli, 1999: 42), has seen that one of the most important variables of regional integration is a foreseeable economic gain. Therefore, regionalism is a tool to achieve economic gain. Moreover Bhagwati in his work (Bhagwati, 1992; Melo & Panagariya, 1993: 43) has elaborated that, regardless of geographical proximity, regionalism is a policy that is designed to lift trade barriers between subset states. Finally, Munakata in her work (Munakata, 2006; Katzenstein Shiraishi, 2006: 130) has added that regionalism is institutional framework set by government as a tool to economic integration with its arrangements entail different commitments from the members. Moreover it is also mentioned that free trade agreement is the solid form of regionalism. In short, the economic perspective sees regionalism as economic gain is an important variable of the regional integration. The economic gain is achieved through the institutional framework of trade, including the uplifting of inter state trade barriers or free trade agreement.

Economic integration, as previously mentioned, is somehow accepted as the analogy of regionalism. Fishlow and Haggard in their work (Fishlow & Haggard, 1992; Tavares, 2004: 19) have seen regionalism as political process, which is characterized as economic policy cooperation and coordination between the states. Meanwhile Bowles in his work (Bowles, 2000; Liu & Reigner, 2003: 6) has defined regionalism as economic policy choice of governments in the form of regional economic integration schemes.

1.7.3 Concept of Interregionalism

Interregionalism theory defines the relations between one region with actors outside of its region. Therefore, interregionalism is strongly influenced by the external influences. The existence of “external cogency” concept is critical in determining the formation of interregionalism.

External cogency is divided into positive external cogency and negative external cogency (Zimmerling, 1991; Doidge, 2011: 37). Positive external cogency pushes the interregionalism process based on the potentials and benefits expected to the integration. Whereas negative external cogency pushes the interregionalism process based on the existence of external power and threat, of which the interregional integration is expected to counter this power and threats.

Apart from the external cogency, it is also argued that interregionalism process can also be resulted from the concept of “extra-regional echoing”. The concept of extra-regional echoing is defined as imitation of behaviour in integrational process carried out by the other regional actors. Furthermore, studies have further exemplified European Union as the main example in elaborating the extra-regional echoing concept. European Union is deemed as having distinctive integration process. It is said to be established on the security matter, and eventually contributed economic benefits to its member countries (Doidge, 2011:37). Moreover, the success of integrational process of European Union is deemed to be the example of integrational process for other regions in carrying out such cooperative integration effort.

Interregionalism comprises three distinct compositions. The compositions of interregionalism are: 1) integration between regional organizations, 2) transregional integration, and 3) integration between regional organization and single powers (Hanggi, 2000:3).

Integration between regional organizations is closely relatable to the New Regionalism Theory, in which two non-state actors establish cooperation. In the case interregionalism, two regional organizations might establish relations in any kinds of form (Hanggi, 2000:4). The examples of this type of interregionalism are EU-Rio Group and EU-Mercosur.

Transregional integration is an interregional cooperation established between countries regardless the regional grouping scheme. The prominent examples of this type of interregional cooperation are Rio Summit 1999 and Cotonou Agreement 2000. Cotonou Agreement 2000 is an interregional economic partnership agreement established between European Union and African, Caribbean and Pacific countries [hereafter: ACP]. The agreement covers the reciprocal trade preferences between EU and ACP (Gathii, 2013: 259). Meanwhile, Rio Summit 1999 is an interregional strategic partnership between EU and Latin American and Caribbean countries. The partnership covers development of political, economic and cultural cooperation between two regions (Santander, 2013; Telo, 2013: 418).

Interregionalism composed of regional organizations and single powers is defined as the cooperation established by one regional organization with one country, whose power is rather dominant in its own region. Hanggi in his work (Hanggi, 2000: 7) has stated that EU-USA high profiled cooperation takes place as the example of interregionalism of this type. Moreover, other examples of this interregionalism type are EU-Indonesia, EU-Canada, and EU-China (Hanggi, et. al., 2005: 44-45).

1.8 Conclusion

In this part, theoretical and conceptual framework of the research is assessed. Theoretical framework of regionalism involves number of theories to construct the understanding of regional integration process. In constructing the understanding of regional integration process, constructivism and realism/neorealism theories are suitable bases. First of all, constructivism theory takes consideration of identity, social conventions and behaviors of states, while realism/neorealism theories consider the world’s anarchy, state, rational decision making by states and power balancing concept.

In order to construct the understanding of regional integration mechanism, intergovernmentalism and institutionalism/neoliberal institutionalism theories are suitable bases. Intergovernmentalism theory considers bargaining process and state preferences as important element within the mechanism of regional integration. Meanwhile neoliberal institutionalism considers the significant role of institution as the tool of regional integration to accommodate states’ interdependence and interaction for its interest.

Conceptual frameworks of the research are comprised of the concepts of region, regionalism and interregionalism. The concept of region is multi variable. It is proven through the variables of geography, and other ideational variables that make the region interconnected such as dynamics of political practices and political institutions, economic interconnection, cultural interconnection, and shared communal identities.

The concept of regionalism has three important variables. The variables that may constitute the regionalism concept are: 1) Cooperation policy between states in particular region, 2) Institutionalized form of cooperation, and 3) Cooperation embodying political and/or economical motives.

The concept of interregionalism is constructed of two variables. These variables include the external cogency and regional interest. Interregional process comprises three distinct compositions. The compositions of interregionalism are: 1) integration between regional organizations, 2) transregional integration, and 3) integration between regional organization and single powers.

CHAPTER 2

REGIONALISM OF SOUTHEAST ASIA AND INDONESIA: EARLIER PERIODS

2.1 Earlier Southeast Asia

2.1.1 States Relations in Pre-colonial Period

When regionalism is simply defined as cooperation between states in particular region, then the process of regionalism has existed in Southeast Asia since even before the colonization period. Dellios and Ferguson in their work (Dellios & Ferguson, 2015: 14) have noticed that the common character Southeast Asian civilization had during pre-colonial period was the polycentricity of political domain. Because of its polycentric characters in pre-colonial period, the existence of inter-state relations of pre-pre-colonial period in both Maritime and Indochina Regions of Southeast Asia is proven through the existence of three kinds of inter-state relations. Inter-state relations during pre-colonial period were comprised by the “Negara”, “Chakravarta”, and “Mandala” (Sundararaman, 2014: 5).

The first inter-state relation was the “Negara”. The term Negara is a term developed by Geertz to refer the relations between micro states in Bali Island, Indonesia (Acharya, 2000: 20). These states were Denpasar, Karangasem, Klungkung, Badung and Tabanan (Acharya, 2000: 22; Sundararaman, 2014: 5). Moreover, the states did not exercise their hegemony over the other states (Acharya 2000: 22).

The second inter-state relation was the Chakravartra. The term Chakravartra was coined by Stanley Tambiah (Tambiah, 1985: 324; Acharya, 2000: 22) to describe the relation between states in Indochina area. These states comprise of Pagan and Pegu in nowadays Myanmar; Sukhothai, Ayutthaya, and Chiangmai in nowadays Thailand; Cambodia and Laos. The relation of states within the scope of this term was established on the autonomous mechanism. In which the mechanism allowed the designation of a king whose function to supervise the autonomous lesser kings under its power. Furthermore, central authority within the Chakravartra term was rather loose (Sundararaman, 2014: 7).

The third inter-state relation was the Mandala. The term Mandala was coined to describe the state relations in particular kingdoms and areas across Southeast Asia. These included Angkor (nowadays Cambodia), Ayutthaya (nowadays Thailand), Srivijaya (nowadays Indonesia and Western Malaysia), Majapahit (nowadays Indonesia and Western Malaysia), and Mindoro (nowadays in The Philippines).

The system of Mandala had allowed a “universal” king to exercise its hegemony over other rulers in its territorial domain (Wolters, 1999: 27). During its period, the territorial area

of a Mandala was extensive. Even if it is compared to the current Southeast Asian geopolitical border, a Mandala could cover one extensive territory of which territories belong to different states nowadays, such as Srivijaya rulers exercised its hegemony in its mandala area located in Sumatera (Indonesia) and Malay Peninsula (Malaysia) (Wolters, 1999: 28). Furthermore, although hierarchical structure existed within the Mandala system, the relation on this particular period was rather unique. Wolter in his work has noted that informal approach was used within this system. Moreover, in order to cover the minimum bureaucratic procedures during this period, the mechanisms of consultation and discussion were preferred (Wolters, 1999: 30).

Aside from its practice during the pre-colonial period, Mandala mechanism was also practiced during the colonial times in The Philippines (Wolters, 1999: 33). This was proven through the testimony made by Francisco Colin, who was a missionary in the seventeenth century in the archipelago. Jocano in his work (Jocano, 1975: 175-176) has mentioned that Colin testified that there existed a mechanism where number of chiefs in particular territories carried out its authority to the lesser chiefs.

Southeast Asia was also robust in trade cooperation during the pre-colonial period. This was rather an impact of Southeast Asia being on the meeting point of three trading “hotspots” during the pre-colonial period. These trading hotspots included Southeast Asia and Persian Gulf, Southeast Asia and China, and Middle East and Africa (Qin & Xiang, 2011: 11). Moreover, the existence of Malacca Strait was politically vital, as it was akin to trade center for two of trading hotspots during the period (Dellios & Ferguson, 2015: 14).

Other than trade network and informality culture, pre-colonial interstate relations in Southeast Asia were also equipped with the diplomatic relations akin to alliance. Ooi in his work (Ooi, 2004: 823) has mentioned that the establishment of relations between Majapahit and Champa, Syangka, Ayutthaya, Cambodia, was some of the alliance-like relations during the pre-colonial period in the region. While Manggala in his work (Manggala, 2013: 7), has assessed that Majapahit’s relations with Champa and Syangka were sorts of power balancing efforts against the Mongol and Chola empires respectively.

2.1.2 Decolonization Period and Cold War

Tribute to the ideological confrontations within it, Cold War is deemed to be the important root of the emergence of regional integration in Southeast Asia. However, decolonization in Asia has opened the door to the ideological war in Southeast Asia. Decolonization period in Asia symbolized the acquisition of freedom from western imperial

power in Asia through the birth of independent nations across the continent, especially in its southeastern part. Although Thailand has never been colonized by western imperial power, more than half of Southeast Asian independent nations were born during this period. The Philippines, although was actually declared in 1898, got their full independence in 1949, Indonesia and Vietnam declared independence in 1945, while Myanmar declared independence in 1948, Cambodia and Laos declared independence in 1953, Malaysia declared independence in 1957 and Singapore declared independence in 1963.

Decolonization period has set the earliest stage for the spread of influence between the East and the West blocs in Southeast Asia as the national political movements played its importance in shaping the political directions in each newborn nation in the region. In fact, Southeast Asia transformed into a battlefield for the confrontation of both the communism and liberal democracy during that time.

First of all, the spread of communism in the region was foreseen in Soviet’s foreign policy. According to George F. Kennan’s infamous “long telegram” in 1946, Soviet was planning to expand their influence towards the said “colonial areas” (Leffler, 2006: 2). Soviet Union was not the only one that was responsible for the growth of communism in Southeast Asia, as China has also played its part in it.

Soviet educated Ho Chi Minh was the most remarkable figure of the growth of communism in Southeast Asia’s Indochina region. Ho Chi Minh revived the communist Viet

Minh Independence Movement and proclaimed the independence of Democratic Republic of

Vietnam in 1945. This independence was later recognized by Soviet and China in Moscow in 1950 (Goscha, 2006; Westad & Quinn-Judge, 2006: 152). At this point, communism influence in Vietnam alone was inevitable.

Zagoria in his work (Zagoria, 1967: 99) has mentioned that for both Allied force and the Eastern bloc, Indochina was far from being top priority when it comes to post Second World War looming problems. Communism indeed has turned the table and this was attributable to Viet Minh for resurrecting the growth of the ideology in the region which it led to the Indochina War in 1955. Meanwhile, communism in Laos and Cambodia has grown steadily a little late than in Vietnam. Laotian Prince Souphanouvong, who once joined Indochinese movement and was the leader of communist political movement Pathet Lao, was the main motor of the growth of communism in Laos. During the Laotian Civil War took place in 1959-1975, Pathet Lao supported by had successfully defeated the national Laotian army. In Cambodia, the figures such as Pol Pot, Ieng Sary, Nuon Chea, Son Sen and Khieu Samphan were the prominent figure of the growth of communism.

The growth of communist activities in Southeast Asia during the Cold War period also included the communist insurgencies in several areas, such as Indonesia, Malaysia, Burma and the Philippines (Weatherbee, 2015: 63). Communist insurgency in Indonesia took place on 30 September 1965 and it was plotted by Indonesian Communist Party [hereafter: ICP]. The “coup attempt” was conducted sporadically by the executives and the caders of the ICP, dissident Indonesian Army members and more than two thousand members of ICP women and youth group (van der Kroef, 1976: 117). During that time, ICP claimed to be having three million members and the party was deemed to be a strong force to reckon with. However, the insurgency movement practically failed and eventually the government countered back the insurgency movement.

Malaysia had also dealt with the communist insurgency which started in 1968. The insurgency was plotted by Malayan Communist Party [hereafter: MCP] and started on 17 June 1968. This insurgency was just another manifestation of the Soviet plan in expanding their influence in the area deemed as “colonial areas” for Soviet Union together with China backed up this insurgency (Buszynski, 2013: 78-85). However, the support the MCP received from both Soviet Union and China ended in 1974. The insurgency has ended through the signing of Peace Agreement of Hat Yai on 2 December 1989.

Growth of communism in Burma was attributable to the revolts of several Burmese communities against the British authorities and the influx of Marxist literature to Burma (Linter, 1990: 3-4). But it was not until 15 August 1939 that the Communist Party of Burma [hereafter: CPB] declared its establishment. The first congress of CPB took place on January 1944 and on August 1944 CPB, together with Socialist Party and Burma National Army formed Anti-Fascist Organization to fight the British colonial administration.

CPB backed the revolt led by All Burma Trade Union, which this was the earliest stage of the communist insurgency in Burma in February 1948. Communist insurgency in Burma started on April 1948 and was mostly occurred in the form of rural guerrilla movement, as CPB dubbed Burma as “semi-colonial and semi-feudal” state that was not prepared for proletarian revolution (Linter, 1990: 14).

People’s Army against the Japanese [hereafter: HUKBALAHAP] led the communist insurgency in the Philippines. The root of the insurgency was the Japanese invasion to the Philippines which had begun on December 1941. Although the United States through the United States Army Force in the Far East [hereafter: USAFFE] had backed national resistance against Japan, the peasant communities tended to form their own force to conduct guerrilla

movement against Japanese invasion which afterwards HUKBALAHAP was formed by three hundred leaders of these peasant communities on March 1942 (Lachica, 1971).

Injustice and maltreatment that the HUKBALAHAP members received from the USAFFE members and Philippine authorities during the periods after the Japanese invasion had started the insurgency from the HUKBALAHAP members against Philippine government. HUKBALAHAP members had allied with Communist Party of the Philippines for some years before the alliance was eventually broken. In linking the Soviet influence to the insurgency in the Philippines, Stephen Morris in his writing has explained that although the Soviet Union had never supported the insurgency in the form of weaponry, however they had supported the insurgency in the form of propaganda support (Morris, 1994:77-93). At the end, insurgency led by the HUKBALAHAP members ended in 1954. HUKBALAHAP communist insurgency was finally settled down through the numbers of reformations and military pursuit (Goodwin, 2001: 119). The Philippine Army was utilized through the military offensives to pursue HUKBALAHAP members in mountainous areas in central Luzon (Lachica, 1971).

The role of United States in confronting the influence of Soviet Union and the growth of communism during the Cold War was prominent. The words regarding communism and Soviet expansionism in Kennan’s “long telegram” were taken as the root to establish the Containment Policy to restrain the Soviet Union expansionism and communism. In Europe, Truman doctrine was the earliest program of Containment Policy (Pilliter, 1969: 2). Truman doctrine was later followed by the existence of other prominent programs within the Containment Policy scheme. These programs consisted of Marshall Plan and the establishment of North Atlantic Treaty Organization [hereafter: NATO] and eventually, Organization for European Economic Cooperation [hereafter: OEEC] was also established in support of the Marshall Plan (Pilliter, 1969: 9).

When Containment Policy was first designed, it was indeed expected to spread liberal democracy and to dispel the communist influences through fortification of economic and security aspects in Europe. In economic aspect, American administration assumed that the wake of communist movement in Europe was a result of horrible situation among the working classes after the World War (Pilliter, 1969: 10). After the war, these European nations were deemed to be inable to rebuild their economies therefore economic assistance such as Marshall Plan was designed to fortify the economy through American assistance. At the end, Marshall Plan was proven to be a well-executed plan. Firstly, it has led to the establishment of

OEEC. Secondly, it had accelerated production rate up to twenty five percents compared to its pre-war production rate (Spanier, 1960: 23).

NATO was another program of Containment policy during the Cold War. It was not until the coup took place in Czechslovakia that security aspect was seen as an urgent need. The Soviet Union was deemed to engineer the coup in Czechslovakia in 1948 which has eventually resulted the communism to grow in the state (Pilliter, 1969: 15-16). After the coup, both United States and European states felt the urgency of the fortification in security aspect in the region. The signatory of the Brussels Pact by France, Great Britain, Belgium, the Netherlands and Luxembourg in 1948 has led to the initiation of the collective security alliance between the United States, some European states and Canada. Afterwards the NATO was signed on 4 April 1949 in Washington, DC.

Containment Policy in Asia during Cold War was remarkably similar with the one that was applied in Europe. Nevertheless one distinct strategy that was not actually run in Europe was the “model state” strategy. At this point, the Philippines were regarded as United States’ “model state” in Southeast Asia.

United States used the Philippines, which was its former colony, to exhibit the success of its liberal democracy ideology in Southeast Asia (Randall, 2010: 21). The Philippines was set as an example to other Southeast Asian nations that democracy could build up a nation’s success and capitalist economy could bring prosperity to a nation. The aim of the “model state” strategy was obviously to encourage Southeast Asian nations to follow the ideology and the growth of communism could be overcome.

United States had applied the similar Containment Policy instruments of economic assistance and initiation of security alliance as in Europe in overcoming the expansion of Soviet Union and communism in Southeast Asia. Economic assistance given to Asia was divided into two parts, which are military assistance and economic assistance (Pilliter, 1969: 107). Up to 1963, Burma, Cambodia, Indonesia, Laos, Malaysia, Philippines, Thailand and Vietnam were the receiver of the United States assistance which the aid counted up to 390 million US Dollars (Sawyer & Peel, 1963: 867).

Safe to say that initiation of security alliance by the United States in Southeast Asia was the door to the birth of regionalism in Southeast Asia. Just like what had happened in Europe, United States felt the need to form some sort of security alliance just as similar as NATO in Southeast Asia. For this reason, SEATO was initiated by the United States after the series of negotiations and consent from Thailand, The Philippines, United Kingdom, France, Australia, New Zealand and Pakistan. Corresponding to the background of the regional

integration as has been explained earlier, participation of Thailand and the Philippines in the alliance was mostly based on the growth of communism and China after the Korean War (Pilliter, 1969: 83).

2.2 Earlier Southeast Asian Regional Institutions

2.2.1 SEATO: The Beginning of Regionalism in Southeast Asia

Soviet expansionism policy, Chinese threat, ongoing Vietnam War and the growth of communism in Southeast Asia during the Cold War had triggered the Western bloc to expand its liberal democratic ideology. Therefore, an establishment of a NATO-like security alliance in the region was felt to be a necessity at that time. United States initiated the establishment of SEATO, of which the idea was finalized in 1954.

The establishment of SEATO was preceded by the negotiations, in which was mostly done by the United States. Eventually, Thailand and the Philippines approved the establishment of the security alliance. The approval was based on the reasons that have been mentioned earlier, which were the growth of communist ideology and the emergence of China as new threat to the region.

On the other hand, Indonesia and Burma opposed the idea. The opposition might be rooted from the disagreement of these states towards the defense mechanism of SEATO, in which it gave authority SEATO to defend the “protocol” states, namely Laos, Cambodia and South Vietnam, in the event of subversion by the communist force to these states (SarDesai, 2016: 317). Furthermore, Indonesia greatly criticized the intervention of non-Asian nations in maintaining the security in the region (Pilliter, 1969: 85-86).

The negotiation led to the Manila Conference in 1954 and produced the Southeast Asia Collective Defence Treaty 1954 [hereafter: Manila Pact 1954] as the basic of the establishment of SEATO. The signatory parties to the treaty were Thailand, The Philippines, United Kingdom, France, Australia, New Zealand and Pakistan (included East Pakistan or nowadays Bangladesh). Eventually, headquarter of SEATO was established in Bangkok, Thailand.

Structure of SEATO was comprised of several working bodies. Governing body of SEATO was comprised of The Council of Ministers. Council of Ministers supervised Council Representatives, The Permanent Working Group, The Budget Sub-Committee, Expert Studies and Secretariat bodies. Moreover, Council of Ministers also had authority over the Military Advisers and Military Planning Office (SEATO Headquarter, 1972: 7-12).

The treaty’s emphasis on the security function was robust. It is proven by the existence of its military advisory committee and also the fact that most of the provision of the eleven articles in Manila Pact 1954 referred to security function. Furthermore the provision of the use of force against communist aggression in Southeast Asia was visible in Article IV Paragraph (1) of Manila Pact 19541. The provision in this article stated that in the event aggression occurred in the territory of any member state and the designated states according to the treaty, the member states agreed to take action. However, the Paragraph (3) of the same article furthermore requires the consent of the related government if the action is about to be taken in the designated states related to the communist aggression2.

There was no provision in this article which directly refers to communist aggression indeed. However, within the additional provision it was elaborated that the clause of aggression in this article was refered to “communist aggression” by the United States3.

Similarity between SEATO and NATO is visible in its collective security function. Article VI paragraph (1) of Manila Pact 1954 possessed similar provision on colective countermeasure against aggression set in the Article V of the North Atlantic Treaty 1949. However, provisional difference from both alliance is that security countermeasure provision in Manila Pact 1954 was applicable beyond the member states’ territory. Whereas security countermeasure provision in North Atlantic Treaty 1949 is limited within the territory of the member states.

Within the same provision in Article VI paragraph (1) of Manila Pact 1954, SEATO also embodied the nature of liberal peace theory in applying its security function. It was stated within the paragraph (1) that each member states should refrain to be involved in aggression against each other. Moreover, as SEATO did, NATO also embodies this nature in its application of security function.

Despite of the emphasis of collective security countermeasure by the members towards aggression which was stated in the first paragraph of Article IV, SEATO was not robust in the

1 Article IV, Paragraph (1) of Southeast Asia Collective Defence Treaty 1954: “(1) Each party recognizes that

aggression by means of armed attack in the treaty area against any of the parties or against any state or territory which the parties by unanimous agreement may hereafter designate, would endanger its own peace and safety, and agrees that it will in that event act to meet the common danger in accordance with its constitutional processes…”

2 Article IV, Paragraph (3) of Southeast Asia Collective Defence Treaty 1954: “(3) It is understood that no

action on the territory of any State designated by unanimous agreement under paragraph 1 of this Article or on any territory so designated shall be taken except at the invitation or with the consent of the government concerned.”.

3 Understanding of the United States of America of Southeast Asia Collective Defence Treaty 1954: “The United

States of America in executing the present Treaty does so with the understanding that its recognition of the effect of aggression and armed attack and its agreement with reference thereto in Article IV, paragraph 1, apply only to communist aggression..”.

case of countermeasure action against indirect aggression. Article IV, Paragraph (2) of Manila Pact 1954 limited the action of countemeasure against indirect aggression4. The paragraph stated in the case of indirect aggression taking place in the territory of any member states or of the “protocol” states, it is a mandatory for member states to consult for approval from the government prior taking countermeasure.

The shortcoming of the provision for countermeasure against indirect aggression in Manila Pact 1954 was proven in the Laotian Civil War in 1959. During that period of time, Laotian military affair was heavily under French power. As Laos was regarded as “protocol” state, SEATO had authority to take countermeasure against the indirect aggression which was conducted by North Vietnamese belligerents through the Pathet Lao. Nevertheless, French authority did not approve the military countermeasure from SEATO (Greencille & Wasserstein, 2001: 366). Eventually, the civil war was won by the Pathet Lao.

In addition to its legislation, security function of SEATO was applied through its joint military exercise program. Military exercise program of SEATO was divided into four categories. The categories are maritime exercise, air-land exercise, sea-land exercise and logistics operation exercise (SEATO Headquarter, 1972: 13). Military exercise had been carried out for ten years from 1956 to 1966 (SEATO Headquarter, 1972: 36).

Other than security function, SEATO had also embodied other functions. The functions which had been embodied in SEATO were economic and social function, cultural function and scientific function. This implementation is compatible to its Article (3) of Manila Pact 19545. In carrying out its economic, social and cultural functions, SEATO had conducted several community development projects which were held from 1959 to 1962 in Philippines and Thailand. SEATO had also conducted several commisions and conferencs in the field of education which were held from 1960 to 1963 in Thailand, Philippines and Pakistan. Moreover, 366 scholarships, 39 lectureships were also awarded from the year 1957 to 1964 (SEATO Headquarter, 1972: 37).

SEATO had carried out scientific function during its existing period. In 1960 SEATO conducted Conference in Cholera Research while inaugurated a cholera research laboratory in

4 Article IV, Paragraph (2) of Southeast Asia Collective Defence Treaty 1954: “If, in the opinion of any of the

Parties, the inviolability or the integrity of the territory or the sovereignty or political independence of any Party in the treaty area or of any other State or territory to which the provisions of paragraph 1 of this Article from time to time apply is threatened in any way other than by armed attack or is affected or threatened by any fact or situation which might endanger the peace of the area, the Parties shall consult immediately in order to agree on the measures…”.

5 Article (3) of Southeast Asia Collective Defence Treaty 1954: “The Parties undertake to strengthen their free

institutions and to cooperate with one another in the further development of economic measures, including technical assistance, designed both to promote economic progress and social well-being…”.