PTSD AND OTHER PSYCHOLOGICAL CONSEQUENCES OF TORTURE IN THE EX-CONVICTS OF DIYARBAKIR PRISON

(1980 - 1984)

ZEYNEP GÜNEY 111629012

İSTANBUL BİLGİ ÜNİVERSİTESİ SOSYAL BİLİMLER ENSTİTÜSÜ

KLİNİK PSİKOLOJİ YÜKSEK LİSANS PROGRAMI

YRD. DOÇ. DR. MURAT PAKER 2016

iii Abstract

This study aims to investigate the psychological profiles of ex-convicts of Diyarbakır Prison, who have served and been tortured between the years of 1980 and 1984. Content analysis was used to analyze 50 interviews that were done by the members of Commission for Truth and Justice on the Reality of Diyarbakır Prison (1980 - 1984). All psychological problems, including post traumatic symptoms, that were told by the participants were categorized and revealed. Although 30 years were passed after Diyarbakır Prison experience and there was not a systematic inquiry of symptoms, it is observed that many participants still displayed Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD) symptoms. Some participants were found to be able to be diagnosed with PTSD and more participants with subtreshold PTSD. Other symptoms specified by the participants were psychological problems they had while in prison, psychological and relational problems they experienced after release, negative mood and memory problems. Another significant finding that was observed in all participants was that when they were telling their traumatic experiences; they preferred to use first or third plural, or second singular pronouns instead of first singular pronoun. The results are discussed through trauma and torture literature.

iv Özet

Bu çalışma, Diyarbakır Cezaevi'nde 1980 ve 1984 yılları arasında kalmış ve işkence görmüş olan eski mahkumların psikolojik profillerini incelemeyi amaçlamaktadır. Bu amaçla, Diyarbakır Cezaevi Gerçeğini Araştırma ve Adalet Komisyonu (1980-1984) üyelerinin yapmış olduğu görüşmeler arasından seçilen 50 görüşme, içerik analizi ile incelenmiştir. Katılımcıların anlattığı tüm psikolojik problemler ve travma sonrası stres semptomları tek tek incelenmiş ve kategorize edilmiştir. Elde edilen sonuca göre, Diyarbakır Cezaevi deneyiminin üzerinden 30 yıl geçmiş olmasına ve katılımcılara sistematik bir şekilde semptomlar sorulmamasına rağmen, katılımcıların Travma Sonrası Stres Bozukluğu (TSSB) semptomlarının bir çoğunu gösterdikleri bulunmuştur. Katılımcıların bir kısmının TSSB tanısı, daha büyük bir kısmının ise eşik-altı düzeyde TSSB tanısı alabileceği

görülmüştür. Katılımcılar tarafından belirtilen diğer problemler;

cezaevindeyken yaşadıkları psikolojik problemler, cezaevinden çıktıktan sonra yaşadıkları psikolojik ve ilişkisel problemler, olumsuz duygudurum ve hafıza problemleridir. Katılımcıların tamamında gözlemlenen belirgin bir bulgu ise yaşadıkları travmatik deneyimi anlatırken birinci tekil şahıs zamirlerini kullanmaktan kaçındıkları ve bunun yerine birinci ya da ikinci çoğul şahsı ya da ikinci tekil şahsı kullandıkları olmuştur. Çalışmanın sonuçları travma ve işkence literatürü bağlamında tartışılmaktadır.

v Acknowledgements

First and foremost I offer my sincerest gratitude to my thesis advisor, Asst. Prof. Dr. Murat Paker, who led the way for me to study in such an area that I work with such passion. His support and never lasting patience enabled me to complete this thesis.

I would like to thank Assoc. Prof. Dr. Ayten Zara and Asst. Prof. Dr. Hilal Eyüpoğlu for their support and substantial contributions. They were both there whenever I needed their existence.

I would like to express my infinite thanks to my uncle Can Murat Bozdoğan and my grandfather Rasim Bozdoğan for they have been there for me and genuinely showed support in a time that I would need it the most. I owe my infinite thanks to my mother for believing in me and supporting me

whatever may come. She has been my number one supporter in all my life and I would not be here if it wasn't for her.

I want to thank my friends Dicle, Aylin, Ecem, Tuğçe, Merve and Aslı for being with me throughout this challenging period, opening the way for me and help me cope with my worries and harsh times. I would also thank Cemal for his support and encouragement, as I know this thesis also means much to him. I would like to thank Binali and Seyit Aziz, as their existence provided me an enthusiastic support that they may not be aware of.

I would like to express my very great appreciation to Bora Aydıntuğ. Though he joined this process later than anyone else, he has become a very important part of it with his interminable support and help. I would never forget his valuable and constructive insight during challenging times of writing this thesis.

Finally, I would like to express my deep gratitude to my analyst, for he guided me patiently through deep ways of discovering myself and helped me come forth from obscurity again and again throughout this period.

vi Table of Contents Introduction ... 1 1.1.Definition of Torture ... 2 1.2. History of Torture ... 4 1.3. Targets of Torture ... 7 1.4. Techniques of Torture ... 9

1.5. The Practice of Torture in Turkey ... 18

1.6. Worldwide Torture Prevalence ... 21

1.7. The History of Kurdish Problem ... 22

1.8. The Development of PKK... 25

1.9. 1980 Military Coup D'etat... 26

1.10. Diyarbakır Prison and Torture ... 28

1.11. Psychotraumatology ... 30

1.12. History of Psychotraumatology ... 31

1.13. The Evolution of PTSD as Diagnostic Criteria ... 34

1.14. Traumatic Events and Trauma ... 36

1.15. Consequences of Trauma ... 38

1.16. Post-traumatic Stress Disorder ... 39

1.17. Epidemiology of PTSD ... 40

1.18. Trauma Studies ... 41

1.19. PTSD and Other Psychological Outcomes of Captivity and Imprisonment ... 44

1.20. Current Study ... 46

2. Method ... 49

2.1. Participants ... 49

vii

2.2.1. The Work of the Comission ... 49

2.2.2. Current Study ... 51

3. Results ... 54

3.1. Demographic Characteristics of the Interviewees ... 54

3.2. The Psychological Profiles of Participants ... 56

3.2.1. PTSD Symptom Cluster B ... 59

3.2.2. PTSD Symptom Cluster C ... 66

3.2.3. PTSD Symptom Cluster D ... 73

3.2.4. Other Psychological Problems ... 75

4. Discussion ... 86

4.1. Limitations and Future Research ... 111

Appendix ... 115

References ... 140

viii List of Tables

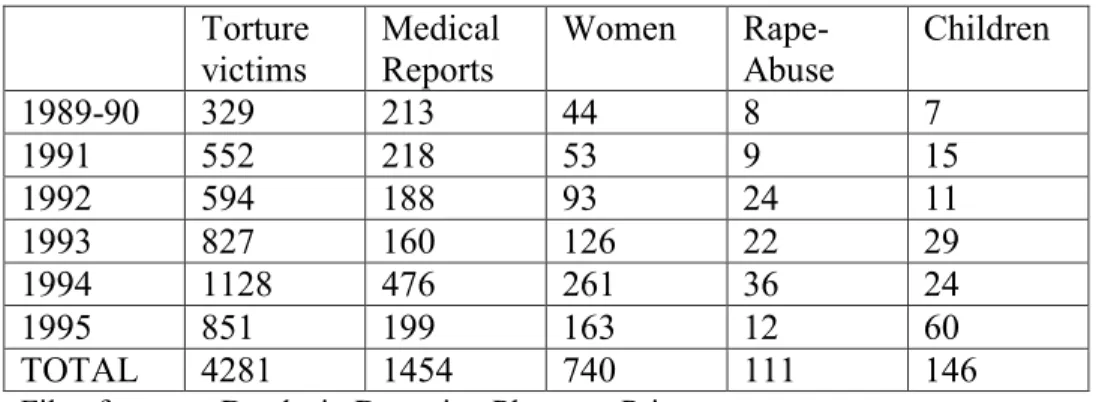

Table 1 Torture Cases Between 1989 and 1995 ... 19

Table 2 Human Rights Violation Rates Between the Years of 1999 and 2010 Based on the Applications to the Human Rights Association of Turkey ... 20

Table 3 Distribution of Turkish Geographic Regions in which torture incidents (between 1991 and 2012) occurred and victims were born ... 21

Table 4 Overall Consequences of 1980 Military Coup D’êtat ... 27

Table 5 Number of Deaths between 1984 – 1995 ... 30

Table 6 The Percentages of Educational Level of Interviewees... 54

Table 7 The Frequencies and Percentages of Torture Methods ... 55

Table 8 Frequencies and Percentages of the Psychological Symptoms Based on DSM-IV Diagnostic Criteria of Post Traumatic Stress Disorder Reported by Ex-Convicted Survivors ... 58

Table 9 Frequencies and Percentages of number of the Ex-convicted Survivors Reporting Other Psychological Problems ... 75

1 1. Introduction

Torture has been a major problem throughout history and though it is legally restricted in many countries, it is still frequently applied and it has many negative consequences on mental health. Torture involves complicated interpersonal relationships between the strong and the weak, so it is also a political issue. Thus, the effects and consequences of torture should also be investigated with an emphasis on the sensitive political nature.

This study aims to investigate the psychological consequences of torture that has been applied on ex-convicts of Diyarbakır Military Prison between the years of 1980 and 1984. In order to do this, the interviews made with ex-convicts as a part of the work of Commission for Truth and Justice on the Reality of Diyarbakır Prison are used. In these interviews, the ex-convicted torture survivors reported their experiences during detention and imprisonment, tell their memories about these times in their own narratives. They also tell about their lives before imprisonment and after release. The psychological profiles of the survivors are investigated with content analysis in terms of Post Traumatic Stress Disorder and other psychological disturbances such as somatic complaints, language use, memory deficits and so on.

The issue of torture in Diyarbakır Prison is also very political, as this period can be viewed as a part of the war between Turkey and PKK, which still has severe negative consequences for both companies psychologically and sociologically.

2 1.1.Definition of Torture

Torture is one of the most extreme forms of trauma that is applied by one human on another. It is considered as an assault on mind as well as body, an interpersonal violence and the most serious violation of a person’s fundamental right to personal integrity.

The definition of torture is often problematic for a number of reasons. First, there are many different situations related to human induced physical and psychological suffering. Second, besides psychological and physical pain on the individual, torture is a kind of a group victimization that also effect families and communities. Third, torture is closely related with both social and political factors which complicate the definition, prevention and treatment of torture.

In Turkish Law Dictionary torture is defined as “An act of applying physical calvary to someone with any aim, or hurt, torment suspects in order to make them confess their crimes” which is an obviously limited definition of torture (Önok, 2006). There are also many international attempts working on the issue of torture. It is known that European Commission on Human Rights, in its extensive report on the Greek Case in 1969, defined torture as consisting of three pillars; severity of the pain, intention and the presence of a specific purpose. Here, the Commission sets the severity of the pain as the main criteria. Additionally, the report suggested that causing pain in the psyche can also be accepted as torture, with the condition that the pain resulted from torture is strong enough, and that physical damage is not

3 required. In the Greek Case, a definition is suggested for nonphysical torture as “beyond physical assault, causing mental suffering by creating a situation of anxiety and stress” (Önok, 2006).

On the other hand, more recent studies use the elements of intention and purpose to distinguish torture from other prohibited behaviors. The following definition of torture was accepted by The United Nations, in Convention Against Torture and Other Cruel, Inhuman or Degrading Treatment or Punishment (CAT, 1984), which is the first instrument to provide a satisfactory definition of torture:

“Torture means any act by which severe pain or suffering, whether physical or mental, is intentionally inflicted on a person for such purpose as obtaining from him or a third person information or a confession, punishing him for an act he or a third person has committed, or is suspected of having committed, or intimidating or coercing him or a third person, or for any reason based on discrimination of any kind, when such pain or suffering is inflicted by, or at the instigation of, or with the consent or acquiescence of, a public official or other person acting in an official capacity. It does not include pain or suffering arising only from, inherent in, or incidental to lawful sanctions.”

146 countries that have ratified the Convention accepted this definition of torture. It should be noted that the emphasis here is on the intention and purpose, not the severity of the pain. Rodley (2002) suggests that the convention has three key pillars for defining torture and other forms of ill-treatment:

4 1. The relative intensity of pain or suffering: besides being severe, the pain also must be a form of already prohibited cruel, inhuman or degrading treatment or punishment.

2. The purpose: confession, obtaining information, etc.

3. The perpetrator: the infliction of the pain or suffering must be inflicted or instigated or incited by a public official.

In summary, torture is a political act made by a public official, with the intention and purpose of getting information or confession, punishment, discrimination, forcing or threat.

1.2.History of Torture

Torture has existed throughout human history and torture practices do not seem to be unique to any political system, regime, culture, religion or geographical region. Unfortunately these practices are applied in all times but in order to refer to torture in technical meaning, the presence of state regulations is a must. Torture has almost always been a part of power relations.

Torture existed in old Chinese, Japanese and Egyptian societies as they had hierarchical organizations. Moreover, China has been one of the places to use the weirdest and cruelest torture methods, which also explains the Turkish saying “Chinese torture”. Long before these societies, even philosophers like Plato and Aristotle defended the practice of torture as legitimate and beneficial (Önok, 2006).

5 Extensive use of torture practices was prevalent all over the world. For instance, use of torture as an interrogation technique seems probable in old India, as it is known that impalement, cutting of lips or tongue, burning or inserting hot iron in the throat was used as punishment. Torture as a punishment was also prevalent in India. Underlying belief was that innocent people would carry out these tests successfully with the help of God; thereby the survivors prove their innocence. Conversely, as the guiltiness of those who fail the tests reveals, their sufferings would become their punishment.

Önok (2006) suggested that there are three main historical periods of torture in its technical meaning; the period that torture was freely applied, prohibited and punished.

In the West, specifically in ancient Greek, as slaves were not considered as a legal entity, it was possible to torture them. The purpose of torture was to investigate and to test the validity of something or honesty of a person. In Rome, statement of slaves considered as true only if it was reinforced by torture, as it was believed that unlike free people, slaves do not have the capacity to think and that they can only express themselves through their bodies. On the other hand, it was prohibited to torture free people and Rome citizens, which law was relaxed in time to involve all who commit crimes against the state.

The church was against torture until 13th century when the proceedings of Roman law were accepted by spiritual court and torture

6 became legal to extort a confession in crimes within jurisdiction of spiritual courts. Henceforth the prevalence of torture rose and even new techniques of torture were discovered. Together with this transition, the common law has changed to bring out the search for the material evidence as fundamental goal. The suspect was expected to obey the state authority at all points. As it was not seen possible to reach the truth only by indication, confessing was the essential proof and all ways were legitimate to reach the confession, including torture.

Consequently, torture has gained an official and systematic quality in Middle Age and all countries in Continental Europe adopted torture as part of judgment procedures by the 17th century. On the other hand, England was the only country to oppose torture continuously.

Other countries increasingly reacted against torture in the course of time, natural law became effective and torture practices gradually decreased. Sensitivity on human rights have risen with contributions of Enlightenment intellectuals, declarations on the issue highlighted respect on human dignity and charged the state to this effect. The system of confession supersede by a new contract in which the suspects are recognized as subjects and given their rights as right to remain silent. Torture was profoundly banned in the mid-19th century.

Lastly, after statements given under duress were classed as crime, countries eventually accepted torture as a crime and prohibition of torture began to take place in international instruments. II. World War incited the

7 reactions against torture and gave way to new regulations on both domestic and international law. Many international human rights documents featured prohibition of torture after 1960s (Doğru, 2006).

1.3.Targets of Torture

There are many targets of torture but the main objects are retaining social control, protecting ruling regimes and to suppress and punish political opponents and criminals. It can be suggested that the aim is to terrorize not only the person but whole population, as the population knows that they can be the next victim. Torturing innocent people also has part in torture’s purpose as by this way people begin to feel that there is nothing that can be done to avoid getting tortured because the selection of victims seems completely arbitrary (Loo, 2009). Even though generally torture does not have an overt place in social agenda, the community still has information about ongoing torture and thus torture achieves its purpose to break the will to resist, the individual’s and also the collective will (Klein, 2005).

The reemergence of torture in the 20th century is thought to be related to the nature of the modern state; as the modern state is vulnerable to state enemies and has its vast power. Torture being a state policy results from the authorities’ perception of a threat to the security of the state from inside and outside and therefore using its extensive power to counter that threat, on groups that are defined as enemies of or potential threats to the state.

Kelman (2005) suggests three important points that provide basis for a policy of torture; the purpose and justification of torture, perpetrators of

8 torture and targets of torture. First, the main justification of torture is the protection of the state from internal and external threats. State’s legitimization doctrine (maintaining stability, or the rule of people embodied by the state, or the rule of God, or the integrity of national institutions) also constitutes justification of torture. Second, the state recruits the perpetrators of torture, who perform an organized profession that is owned by the state, works within the state’s internal security lines and devoted to the service and protection of the state. Third, the targets of torture are those who are seen as threats to the state’s security and survival. Thus targets are placed outside the protection of the state as they are seen as enemies of the state besides other reasons like their ethnicity or ideology. The targets are treated as they do not have the rights of citizenship which makes them a “non-person vulnerable to arbitrary treatment, to torture, and ultimately to extermination” (Kelman, 2005).

In explaining the aim of torture, Suedfeld (1990) presented five goals:

Information:

The aim of the torturer is to gain information regarding criminal, political or military issues.

Incrimination:

The aim is to make torture victims to identify other individuals who were thought to be involved in prohibited activities.

9 Indoctrination:

The torturer aims to make the victim abandon previously held political views, beliefs and change loyalties so that the victim would internalize the torturer’s.

Intimidation:

Torture is used to frighten potential victims by making torture and its consequences publicly known. It also includes torture as a punishment, when it is legally applied by police or prison authorities.

Isolation:

The isolation practices make the victim believe that s/he does not have anything in common with the torturer, other victims or even the rest of society. It leads the victim feel impotent and helpless as s/he sees the torturer’s omnipotence.

All the targets addressed above can be said to be aimed in Diyarbakır Prison. The main goal was to prevent a new Kurdish identity to emerge though the result was reverse. In contrast with common belief the main target of torture is not to gain information or take confession, but silence and suppress the victims (Paker, 2007).

1.4.Techniques of Torture

The main purpose of the torturer is to destroy the self-esteem and personal integrity of the person by using methods that cause maximum

10 physical and mental pain. Common torture techniques are universal, even though some special methods change from country to country and era to era.

On the other hand, torture methods that avoid leaving marks on the body or at least cause easily healed physical injuries are preferred in the countries or during periods that public awareness against torture undergoes a rise. Instead, psychological torture edged ahead which is a difficult term to define. The definition of torture includes “severe pain and suffering” which refers to mental and physical aspects together. Both physical and psychological torture produces mental and physical suffering which makes it difficult to define psychological torture as a separate entity. Even though psychological torture can be simply defined as “severe mental pain or suffering caused by the threat of, or actual, administration of procedures calculated to disrupt profoundly the senses or personality” (Reyes, 2007)

Many studies working on psychological torture use Biderman’s categories of “basic communist techniques of coercive interrogation” (Tarakçıoğlu, 1990; Ojeda, 2008). The eight categories of Biderman were as follows:

Isolation

Isolation can be in the forms of complete solitary confinement, complete isolation, semi-isolation or group isolation. The aim is to fight down resistance by breaking its main source, close relationships. Isolation leads the victims to return into their own and to be caught in close relations with interrogator.

11 Monopolization of Attention

Physical isolation (keeping the victim in small, windowless cells or sometimes in complete darkness), by restricting sensory stimulation (deprivation of sensations or movement, keeping the victim in a fixed posture, making him hear sounds of torture on others),prolonged interrogation and forcing the victim to write as instructed. The technique keeps the attention on the moment and shifts the victim’s mental occupation to himself and detention conditions, thus cuts out any movement that falls out obedient behavior.

Induced Debilitation and Exhaustion

Semi-starvation; exposure (intense cold or heat, wetness); usage of wounds and chronic illness as an instrument; sleep deprivation (making the victim sleep in uncomfortable positions, on hard surfaces or waking up for interrogation); long periods ofstrain (forced sitting, standing at attention or in other forced positions; forced stay in a box or hole; bonding the victim in painful or unnatural postures); prolonged interrogation and forced writing.

Cultivation of Anxiety and Despair

Threats of death (verbal threats, grave digging, fake executions); threats of non-repatriation; threats on punishing the victim as a war criminal; threats of perpetual isolation or torture; threats against prisoner's loved ones; groundless changes of treatment, place of captivity, in questioning style or interrogators.

12 Alternating Punishments and Rewards

Presenting occasional favors (to make the victim believe that interrogators are good people, to make the victim remember pleasant things), changes in the attitudes towards the victim (good cop/bad cop scenario), proposing improved conditions or other rewards in return for cooperation or displaying others who acquired those rewards, tormenting (offering cigarettes with no matches).

Demonstrating Omnipotence

The aim is to give an impression that it is normal to cooperate with the interrogator, to request cooperation, making the victim feel that his fate depends on the interrogator and there is no use of resistance. The interrogators cultivate an image that they already have all the information about the victim and the process is only a test of cooperativeness and that the victim’s fellows have already yielded.

Degradation

Preventing personal hygiene (keeping the victim deprived of combs or shaving equipment, shower or even holding him in his own feces), dirty or sickening surroundings, insulting punishments (slapping, ear-twisting, and other degrading punishments); indignity, intervention on privacy.

Enforcing Trivial and Absurd Demands

Forced writing (forcing the person to write and rewrite to answer interrogator’s question until his answer its acceptable), making the victim

13 obey to meaningless orders or weird rules. The aim is to gain ground for obedience in daily activities.

Despite the fact that psychological and physical torture cannot be distinguished, it would still be useful to specify physical torture methods. İstanbul Protocol, the first set of international guidelines for documentation of torture and its consequences, discusses the special torture methods under eight titles which are; beating and other forms of blunt trauma, beating of the feet (falanga), suspension, other positional tortures, electrical shock torture, tooth torture, asphyxiation, rape and sexual torture (HRFT, 2003). Based on the İstanbul Protocol, The Atlas of Torture presents almost all of the torture methods that took place in the protocol, with an emphasis on those more frequently encountered in Turkey, including their prevalence (HRFT, 2010). These are:

Beating

It is known that torture survivors are mostly subjected to different kinds of beating which include slapping, kicking, punching, continuously beating with hard objects, throwing against the wall or over the floor, throwing down from high places or stairs, hitting the same part of the body continuously, hitting the head against the wall or over the floor. 87.3% - 90.1% of torture survivors who applied to Human Rights Foundation of Turkey in recent years reported a history of beating (HRFT 2005, 2006, 2007).

14 Falanga

Falanga is defined as “repeated application of blunt trauma to the feet (or more rarely to the hands or hips), usually applied with a truncheon, a length of pipe or similar weapon” (Istanbul Protocol paragraph 203). Human Rights Foundation of Turkey reports that torture survivors were subjected to falanga with a rate of 3.8% - 14.7% (HRFT 2005, 2006, 2007), which was 19.8% – 20.7% ten years ago (HRFT 1995, 1996, 1997). It is reported that falanga as a torture method decreased in terms of frequency due to scientific studies which can detect bone injuries due to falanga even after a long period.

Suspension

It’s a common form of torture that can cause extreme pain while leaving little or no visible evidence. 7 – 33.7% of torture survivors who applied to Human Rights Foundation of Turkey in recent years reported being subjected to different suspension types (HRFT 2005, 2006, 2007).

Other positional torture

Positional torture ties or restrains the victim in contorted, hyperextended or other unnatural positions. It causes severe pain, injures the ligaments, tendons, nerves and blood vessels and leaves few external marks or other medical evidence. 15% - 26.9% of the torture survivors who applied to Human Rights Foundation of Turkey in recent years stated that they were subjected to various positional tortures other than suspension (HRFT 2005, 2006, 2007).

15 Electric shock

In this method electrodes are placed on a part of the body which lets electric current to transmit through. The most common areas for these electrodes are hands, feet, fingers, toes, ears, nipples, mouth, lips and genital area. The torture survivors who applied to the Human Rights Foundation of Turkey in recent years reported being subjected to electric shock torture with a rate of 8.6% - 40.1% (HRFT 2005, 2006, 2007).

Asphyxiation

Asphyxiation by suffocation is a very common torture method and it usually leaves no mark. Respiration of the victim can be prevented through methods as covering the head, closure of the mouth and nose or forced aspiration of dust or other things. Another common method is forcing the victim’s head in water, often contaminated with urine, feces and it may result in near drowning or drowning.

According to Human Rights Foundation of Turkey, most frequently used methods in Turkey seems to be immersing head into water or soiled water, preventing to breath by a wet towel or similar materials, suffocation by putting the victim’s head inside a plastic bag or similar things. Asphyxiation torture was reported by torture victims who applied to Human Rights Foundation of Turkey with a rate of 4.5%-5.1% (HRFT 2005, 2006, 2007)

16 Rape and sexual torture

Istanbul Protocol defines sexual torture as follows (Istanbul Protocol 215-216):

Sexual torture begins with forced nudity, which in many countries is a constant factor in torture situations. An individual is never as vulnerable as when naked and helpless. Nudity enhances the psychological terror of every aspect of torture, as there is always the background of potential abuse, rape or sodomy. Furthermore, verbal sexual threats, abuse or mocking are also part of sexual torture, as they enhance the humiliation and its degrading aspects, all part and parcel of the procedure. The groping of women is traumatic in all cases and is considered to be torture.

There are some differences between sexual torture of men and sexual torture of women, but several issues apply to both. (…) In most cases, there will be a lewd sexual component, and in other cases torture is targeted at the genitals. Electricity and blows are generally targeted on the genitals in men, with or without additional anal torture. The resulting physical trauma is enhanced by verbal abuse. There are often threats of loss of masculinity to men and consequent loss of respect in society. Prisoners may be placed naked in cells with family members, friends or total strangers, breaking cultural taboos. This can be made worse by the absence of privacy when using toilet facilities. Additionally, prisoners may be forced to abuse each other sexually, which can be particularly difficult to cope with emotionally. The fear of potential rape among women, given profound cultural stigma associated with rape, can add to the trauma. Not to be neglected is the trauma of potential pregnancy, which males, obviously, do not experience, the fear of losing virginity and the fear of not being able to have children (even if the rape can be hidden from a potential husband and the rest of society).

17 Among the torture survivors who applied to Human Rights Foundation of Turkey in recent years, 1.3%-4.2% reported rape incidents and 15.6%-31.5% reported sexual harassment. Wringing of the scrotum had a range of 6.4%-34% (HRFT 2005, 2006, 2007).

Exposure to cold

Exposure to cold is one of the most frequent torture methods. It can be applied such as keeping in a cold environment, keeping naked and/or wet for a long time, using compressed cold water, forcing to lie on ice, forcing to walk barefoot on ice or snow. It is stated that there has been an increase in methods like keeping on ice or using compressed cold water, as it leaves less external marks on the victim when compared to other methods (HRFT, 2010). Among the torture survivors who applied to Human Rights Foundation of Turkey in recent years, 29.9%-39.5% reported being kept in a cold environment and compressed cold water torture (HRFT 2005, 2006, 2007).

Burning and cigarette burns

Applying hot objects on the skin is a worldwide torture method. The method can include flames, acids or caustic liquids, hot metallic bars, irons or electric heaters, candles or melting rubbers. Burning with a cigarette is a common torture method in Turkey and worldwide. Torture survivors who applied to Human Rights Foundation of Turkey recently have reported 1.4%-2.4% rate of being subjected to cigarette burns (HRFT 2005, 2006, 2007).

18 Using animals for torture

Torture practices can include dogs, cats, mice, rats, snakes and scorpions. The method is especially used in isolation cells which are located in basement floors or underground where rats are common. Torture with animals is not well presented in recent HRFT reports as it’s not a common method in Turkey. The method was more frequently used in the detention centers in the 80s and in the first half of the 90s (HRFT, 2010); as it can be seen from Diyarbakır Prison victims’ experiences.

1.5.The Practice of Torture in Turkey

Torture had a legal ground neither in Turkish state nor in Ottoman Empire. The main reason for this in Ottoman Empire was that Islamic law invalidates any confession under duress (Önok, 2006). Even so, it is known that torture had its place in practice by both governments to suppress its opponents.

Besides the period after 1971 coup by memorandum in Turkey, rise of nationwide and systematic torture practices have its roots in 1980 coup d’êtat. Whereas the targets of torture were communists, unionists and Kurdish community in search for national demands, after 1980, torture headed towards anyone who opposes the vision of National Security Council. Tarakçıoğlu (1990) states that in Turkey, as in other countries, institutionalized, intense, systematic and prevalent torture practices as a political instrument after 1980 aimed:

19 1. To counteract and destroy active opponents of regime and the organization structure that represents their social and political positions 2. To suppress national consciousness and destroy national identity

3. To suppress possible opponents of the regime and the communities that active opponents emerged

4. To threaten the whole populace.

It is claimed that tens of thousands of people were tortured and fourteen thousand people died (460 during torture) in fifteen years following coup d’êtat. In general it is stated that one million people were tortured since 1980 until present. The table below shows torture incidents that have been detected by Human Rights Foundation of Turkey between 1989 and 1995 (HRFT, 1996).

Table 1: Torture Cases between 1989 and 1995

Torture victims Medical Reports Women Rape- Abuse Children 1989-90 329 213 44 8 7 1991 552 218 53 9 15 1992 594 188 93 24 11 1993 827 160 126 22 29 1994 1128 476 261 36 24 1995 851 199 163 12 60 TOTAL 4281 1454 740 111 146

File of torture: Deaths in Detention Places or Prisons

Table 2 shows the prevalence of human rights violation rates in Turkey between the years of 1999 and 2010 (HRA, 2011).

20 Table 2: Human Rights Violation Rates between 1999 and 2010 detected from the applications to Human Rights Association of Turkey

Year Doubtful deaths/deaths in custody because of extra judicial execution,torture or by village

guards

Torture and ill-treatment 1999 205 594 2000 173 594 2001 55 862 2002 40 876 2003 44 1202 2004 47 1040 2005 89 825 2006 130 708 2007 66 687 2008 65 1546 2009 108 1835 2010 100 1349 Total 1122 12118

By the Documentation Unit of Headquarters

Human Rights Foundation of Turkey (2015) revealed statistics of their work with torture victims in 22 years. Depending on the victim’s statement; 72% of torture incidents occurred in official custody (police headquarters, police stations, gendarmerie headquarters, military guard), 24 % in nonofficial custody (in vehicles, street/open space, victim’s own place or home) and 4% in prisons. The reason for last custody seems to be 91.40% political, 8% forensic cases, 3% sexual identity and orientation and 3% refugees. Table 3 shows the rates of geographic regions in Turkey as reported torture incidents occurred and as birthplaces of torture victims (HRFT, 2015).

21 Table 3: Distribution of Turkish Geographic Regions in which torture incidents (between 1991 and 2012) occurred and victims were born

Birthplace % Torture incidents %

Mediterranean 10 19.14 Southeastern Anatolia 34 18.36 Aegean 9 16.26 Eastern Anatolia 20 4.79 Black Sea 5 0.87 Central Anatolia 8 9.44 Marmara 7 29.60 Abroad 2 - Unclear 9 -

22 Years of Torture in Turkey

It is stated that it’s not possible to present any quantitative assessment regarding ethnicity of torture victims, as interview files did not include any question regarding ethnicity. However the distribution of birthplaces of torture victims shows that majority of victims are from Eastern and Southeastern Anatolia, where Kurdish ethnicity is prevalent.

1.6. Worldwide Torture Prevalence

When reviewed worldwide, the most striking example of torture is the holocaust because of its severe consequences. In 1939, with the World War II, implementation of systematic torture began in concentration camps. Approximately six million Jews were targeted and methodically killed by Hitler’s regime and its collaborators between 1941 and 1945. It is also estimated that five million more Non-Jewish victims (Gypsies, Poles, communists, homosexuals and mentally and physically disabled) were involved in the holocaust, which brings the total to 11 million, one million

22 of whom were Jewish children. These people died as a result of starvation, irrational and inhuman experiments, being kept in gas chambers, being shot and so on. As the history of torture is very old, this striking and well-known example of torture is not the first or the last.

As estimated, reliable rates of torture practices are either suppressed or denied by governments because of the politically sensitive nature of torture, which emphasizes the interest in the work of independent organizations.

Even after the Convention against Torture and Other Cruel, Inhuman or Degrading Treatment or Punishment, Amnesty International states that they have reported torture in at least three quarters of the world (141 countries) over the last five years. In a global survey of more than 21.000 people in 21 countries, AI observed that 44% of people fear torture if taken into custody, more than 80% want new law regulations to protect them from torture and more than one third of people believe that torture can be justified (AI, 2015). In 2012, it is suggested that 112 countries tortured or otherwise ill-treated their citizens and 80 countries conducted unfair trials (AI, 2013). In 2013, 82% of the countries (131 out of 160) that AI worked with tortured or otherwise ill-treated people (AI, 2014). When it comes to 2014, AI reported 131 countries (82%) in which torture and ill-treatment were conducted and at least 93 countries (58%) where unfair trials took place (AI, 2014/15).

1.7.The History of Kurdish Problem

Besides having a definition problem, Kurdish problem needs to be understood in the context of radical transition from Ottoman Empire that

23 held national, ethnic, religious and linguistic multiplicity to Turkish state. After World War I, Turkish Republic was found as a modern nation-state, grounded on homogeneous nation unity instead of religion based nation system of Ottoman Empire (Okutan, 2004). After the war, Kurdish people became citizens of four separate nation-states (Turkey, Syria, Iraq and Iran) which led each country to have a “Kurdish problem” and the Kurdish problem to gain a supra-state quality (Şahin, 2011).

Turkification politics and resistance against these politics in the first years of the Republic have played an important role in structuring Kurdish national identity, Kurdish nationalism and Kurdish politics. It can be claimed that Kurdish problem is regenerated, instead of being solved, in republic period by denying the existence of Kurds or using maximum military methods when needed.

As in other examples, Turkish nation-state created a single and homogeneous Turkishness while “others”, who resisted homogenization efforts, were perceived as threats and the major threat were Kurds. What made Kurds “others” were their tribal structure that did not match the objects of the modernity project. Removal of the Caliphate and election of Turkishness as the upper identity of different ethnicities paved the way for marginalization, assimilation of and repressive denial politics on Kurdish community. Assimilation of Kurds was performed through education and language, military and resettling politics.

24 In 1924, the law on unification of education was accepted which has an important role in Turkification and homogenization politics. According to the law, all Kurdish schools, institutions and publications, sects and dervish lodges were closed. Hassanpour (1997) defines the effects of the practices unifying language and education on Kurdish language and culture as “linguistic genocide” and suggests that prohibition of mother tongue is a kind of symbolic violence.

All these new arrangements directly targeting Kurdish society led to mass rebellions in Eastern Turkey. The state proclaimed martial law in 1925 and people who breaches the order started to be tried in Independence Courts. New reform plans were made in an effort to assimilation, using Kurdish language was prohibited and counterinsurgents from not only military forces but also civilian population were protected with laws.

Soon after the rebellions, aiming at long term effective solutions, reforms were planned to change the demographic structure of Kurdish regions. The settlement law intended the disintegration of villages that Turkish was not the mother tongue. Non-Turkish Muslims, Arabs and Kurds who were known or suspected to be involved in the rebellions were to be settled in regions of Turkish mother tongue. Kurdish speaking population was going to be distributed as not exceeding five percent of the whole population of settlement (Şahin, 2005). All these reforms and interventions played an important role in Kurdish politics and the establishment of PKK.

25 1.8.The Development of PKK

Kurdish community started to be organized politically after the mutiny acts and use of armed forces. Including as a result of industrialization, developing communication technology and presence of Kurdish university students in Western cities, more oppositional Kurdish politics emerged in 1960s.

Kurdish politics adopted the thought that their problems would be solved not in the context of class conflict and economic exploitation problems but as being accepted as Kurds; which led them to resolve from Turkish leftists. PKK (Partiya Karkerên Kurdistan, Kurdistan Workers' Party) was established by one of these groups, led by Abdullah Öcalan, as a Marxist – Leninist organization in 1974. PKK’s aim was to establish an independent and united Kurdistan which legitimized use of violence and armed struggle in order to actualize a Kurdish revolution. PKK has been the most important actor in shaping Kurdish politics in Turkey.

In this context, it can be suggested that Diyarbakır Prison was a pivotal experience in Kurdish problem. Diyarbakır Prison was a plan to assimilate, silence or destroy Kurdish movement and PKK’s guerilla warfare aroused significantly after 1984, which coincides with main releases from Diyarbakır Prison. It is even suggested that suppressive politics in Eastern Turkey, 1980 Military Coup D’êtat and Diyarbakır Prison have played a more important role in strengthening Kurdish national consciousness than

26 PKK’s propaganda (Şahin, 2005). In this sense, these processes need further consideration.

1.9.1980 Military Coup D’êtat

In 12th September 1980, a right-wing military junta took state power. Following coup d’êtat, martial law was established, political parties, trade unions and also democratic rights were abolished. This coup was a response to social and political conflicts, where rightists and leftists resorted to murder and other forms of violence, that the government seemed powerless to remedy. There was repression against working class and left wing opponents of the regime. The army took over government, perceived all opposing political attitudes as danger and adopted a denial, suppression and intimidation policy. It can be suggested that political activists and Kurdish citizens were the groups that were affected most.

The regime favored Turkish Nationalism which led to two important developments on Kurdish problem; the legal prohibition of using Kurdish language and rising pressure on Kurdish identity. The ongoing chaos in the country was tried to be controlled by using practices that excessively violate human rights. Military period lasted 3 years followed by similar practices of repression and consequences of the coup are still present today. Table 4 shows overall consequences of 1980 Military Coup D’êtat. It must be known that the statistics are obtained from official state reports, which may not present the actual data.

27 Table 4: Overall Consequences of 1980 Military Coup D’êtat

The number of people who were detained for political

reasons 650.000

The number of people who were blacklisted 1.683.000

The number of people who were tried by court marital 210.000 The number of people for whom penalty of death was

proposed 7.000

The number of death penalties that have been sentenced 517

The number of people executed 50

The number of people tried for being member of an

organization 98.404

The number of people who were banned from receiving

passport 388.000

The number of people who were fired because of being

suspected 14.000

The number of people who went abroad as political refugees 30.000

The number of people died suspiciously 300.000

The number of people reported to die due to torture 171

The number of movies that have been banned 937

The number of organizations that have been closed 23.677

The amount of newspaper and journals destroyed 39.000 kg

The amount of penalty of imprisonment proposed for

accused journalists 4000 years

The total amount of penalty of imprisonment sent up for

Journalists 3.115 years

The number of people who have lost their lives in prison 299 The number of people who were dead due to hunger strike 14 The number of people who were shot while escaping 16

The number of people died in shootouts 95

The number of people who were reported as “normal death

record” 73

The number of people who were reported as being

committed suicide 43

28 1.10. Diyarbakır Prison and Torture

Diyarbakır Prison is built in 1980 as an E-type prison by Turkish Ministry of Justice. Diyarbakır is in the Southeastern Turkey, where mostly Kurdish population lives. The prison was transferred to military administration after 1980 Coup D’êtat and became a Martial Law Military Prison which led to extremely cruel torture practices and placed the prison into “The ten most notorious jails in the world” (Hines, 2008).

Almost all of the detainees were Kurdish citizens and they were mostly members or sympathizers of armed leftist organizations including PKK. The prison was used as a concentration camp, in which Kurdish citizens and PKK members were tortured and killed. There were also people who were not political activists, members or sympathizers of any group and they were also subjected to the same treatment as others.

The main purpose of torture practices in Diyarbakır Prison was to destroy Kurdish identity by imposing an Anti-Kurd doctrine. Kurdish detainees were tortured, humiliated and trained in military methods. Militarism led the most prevalent torture methods; people were forced to join military training, give oral report, line – or even sleep –in attention position, stand guard, memorize a variety Turkish National Anthems even if they did not know a word of Turkish, painting Atatürk portraits or maps of Turkey and so forth. Detainees who disagree or fail to perform these tasks were tortured as punishment. Prisoners were being subjected these Turkish national symbols in parallel to the state’s assimilation policies. Kurdish

29 language was banned not only for the prisoners but also for their visitors many of whom did not speak Turkish. The prisoners were facing more torture if the they or their visitors spoke any word of Kurdish. All these practices intended to make the Kurdish prisoners quit their identities and accept Turkish superiority. Contrary to expectations, all these interventions caused Kurdish identity to strengthen and Kurdish militarism to rise. After releases from Diyarbakır Prison in 1984, many prisoners chose, or were forced, to join Kurdish armed forces and PKK has strengthened its armed structure; which intensified the struggle between Turkey and PKK.

The conflict cost many lives from both sides in years. The Committee on Human Rights Inquiry (2013) presented statistics on the consequences of warfare between 1984 and 2012. According to their report; 7.918 government officials and 22.101 PKK members were killed, unsolved deaths are predicted as between 2.000 and 17.000. Not only armed groups have lost their lives in this war, also 5.557 civilians were killed. Except death cases that were not reported in statistical data, 35.576 people were killed due to the struggle between Turkey and PKK. Table 5 shows consequences of the struggle between 1984 and 1995.

Diyarbakır Prison was not the only example in Turkey; torture was prevalent in all country. HRFT reported that 419 people died in detention places and prisons in the following 15 years after 1980 Coup D’êtat and that 190 out of 460 death cases were recorded during three years junta period. Additionally, 15 people died during hunger strikes, 26 people died due to illnesses that were caused by torture or ill-treatment (File of Torture, 1996).

30 Table 5: Number of Deaths between 1984 – 1995

Year PKK Members Civilian Soldier Police Village Guard

1984 11 20 24 - - 1985 100 82 67 - - 1986 64 74 40 - - 1987 107 237 49 3 10 1988 103 81 36 6 7 1989 165 136 111 8 34 1990 350 178 92 11 56 1991 356 170 213 20 41 1992 1055 761 444 144 167 1993 1699 1218 487 28 156 1994 4114 1082 794 43 265 1995 2292 1085 450 47 87

Adopted from the Report of Federation of American Scientists 1.11. Psychotraumatology

Psychotraumatology is the field that studies psychological trauma by investigating factors that are related to preceding to, in the course of and following to psychological traumatization. Among the preceding determinants of psychological traumatization are premorbid psychological functioning, personal and familial history and behavioral risk factors. Traumatogenetic environmental, biological and interpersonal factors are related to concomitant factors of psychological trauma. A traumatic event has subsequent factors like physiologic and behavioral consequences, responses to trauma and sociological atmosphere (Everly, 1995).

Individuals experience trauma in a range of situations which contains collective events like combat, war, terrorism and natural disasters; and personal experiences like rape, accidents, sudden loss of a loved one, witnessing homicide (Fodor et. al., 2014). Many people experience these

31 traumatic events and most of them generally adapt to the situation, adjust to the aftereffects and not develop traumatic disorders. On the other hand, some people are damaged psychologically, biologically and sociologically after experiencing trauma (van der Kolk and McFarlane, 1996).

1.12 History of Psychotraumatology

Studying with patients who were affected by the events and wars of The French Revolution, Pinel wrote about war neuroses and acute post-traumatic states. The study of psychotraumatology in modern psychiatry has started with The Industrial Revolution as it introduced steam machinery that led to the first civilian human-made disasters and Post Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD) cases outside the battlefield. Railway disasters has led to a shock in public and physicians were unable to understand the psychological symptoms of the survivors. These symptoms were explained by organic theory as lesions of the spine or brain and named as "railway spine" (Crocq and Crocq, 2000). Emerging research suggesting these symptoms were hysterical and the main cause was emotional shock has led to controversial discussion until World War I.

In this period, the term "traumatic neurosis" was proposed by Oppenheim for the first time (1988; as cited in Weisæth, 2002). Charcot criticized this new diagnosis who thought these symptoms were only forms of hysteria. In association with Charcot's lectures, traumatic hysteria were discovered by Janet and Freud with its characteristics of dissociation,

32 forgotten memories and cathartic treatment; which later formed the understanding of unconscious (Crocq and Crocq, 2000).

Over time body and mind relationship became the focus of attention rather than physical explanations (Weisæth, 2002). Janet presented a cognitive model for trauma based on mental schemas that are formed of memories. These mental schemas are stores in subconscious and help individuals relate to their environment. When overwhelming feelings cause a difficulty integrating them into mental schemas, traumatized individuals dissociate them from consciousness. Failure in categorizing and synthesizing leads the individual to an inability to develop new cognitive schemas that would help their coping with new challenges (1904; van der Kolk, Weisæth & van der Hart, 1996).

Then Freud developed "unbearable situation" and "unacceptable impulse" models on trauma. The unbearable situation model suggests that vehement emotions such as fear or dread can have an overwhelming and devastating effect on ego which might cause traumatic neurosis. Then Freud abandoned this theory and rather than the traumatic event itself, he focused on the role of unacceptable sexual and aggressive drives which threaten the ego and disrupt the function of defense mechanisms. With this new model, psychic reality and subjective meaning of trauma came into prominence (Weisæth, 2002).

As being the first modern war including massive industrial means, World War I has led scientific psychiatry coincide with modern warfare and

33 gave way to diagnostic definitions as we use them today. It advanced the knowledge of psychotraumatology in European psychiatry (Crocq and Crocq, 2000).

Cardiac symptoms such as rapid pulse and respiratory problems were observed in soldiers during the war and these symptoms were named as "soldiers' heart" or "irritable heart". At first, an organic explanation was used suggesting that an overstimulation in specific nerve centers are responsible for these symptoms (Weisæth, 2002). This explanation was rejected by Myers who observed that soldiers who were not exposed to direct gunfire also suffer from same symptoms and an emotional explanation was proposed. These developments supported the progress of the studies of mind and body relationship and a new understanding of post traumatic responses (1940; van der Kolk, Weisæth, & van der Hart, 1996).

Unconscious intrapsychic conflicts remained focus while real life events lost their significance on explaining trauma related symptoms between World Wars. An integrative explanation was developed on post traumatic symptoms with the work of Kardiner (Weisæth, 2002).

World War II can be described as a "total war"; with systematic targeting of civillians as Holocaust, air strikes on cities and atomic bombs used in Hiroshima and Nagasaki. Many psychiatric illnesses emerged once again and the armies were unprepared even with the experience of World War I (Crocq and Crocq, 2000).

34 Based on Kardiner's view of trauma, many therapeutic techniques were developed for the treatment of post traumatic symptoms. Studies on Holocaust and other war traumas led to a specific area of research. 'Concentration camp syndrome' was investigated to reach a deeper understanding of symptoms that grew into current PTSD symptoms. War related studies provided base for investigation of long-lasting effects of trauma (van der Kolk, Weisæth, & van der Hart, 1996).

These studies and war experiences facilitated the treatment of psychiatric symptoms during Vietnam War; yet veterans suffered from alcoholism, drug abuse and delayed post traumatic disorders. Almost one quarter of soldiers sent to Vietnam from 1964 to 1973 needed a form of psychological help. In the seventies veterans were increasingly diagnosed with post-Vietnam syndrome which led to the adaptation of Post Traumatic Stress Disorder as a diagnostic category in DSM-III in 1980 (Crocq and Crocq, 2000). Historical evaluation of PTSD would help to gain a deeper understanding of recent developments in trauma studies.

1.13. The Evolution of PTSD as Diagnostic Criteria

Before the term PTSD was used in DSM-III; shell shock, soldiers' heart, irritable heart, war neurosis, gross stress reaction, traumatic neurosis were used to define trauma related symptoms (Everly, 1995).

Historical evolution of PTSD was summarized by Wilson (1995) as follows:

35 DSM-I included Gross Stress Reaction which defined post trauma symptoms through narration. Responses to trauma were described as acute reactions and thought to disappear in a short time. The person should only be diagnosed if the reactions are prolonged and persistent. The healing process was accepted to occur with a quick and efficient intervention, regardless of the trauma (APA, 1952).

DSM-II included PTSD as Adjustment Reaction of Adult Life and involved only three cases without enough description and explanation (APA, 1968).

In DSM-III, PTSD was accepted under anxiety disorders; with three symptom clusters and 12 symptoms in total. Patients demonstrating at least four symptoms among these clusters were diagnosed with PTSD. In DSM-III, PTSD was seen as a normal reaction to an abnormal situation and traumatic responses as normative (APA, 1980).

The number of symptoms raised to 17 in DSM-III-R and patients with six symptoms among three clusters with a duration of at least 1 month were diagnosed with PTSD. Trauma responses that lasts less than 1 month were accepted as normative. In "A" criterion, events that cause PTSD were described with 5 examples. How the trauma is reexperienced by patients was described in "B" criterion. "C" criterion explains how the patients moderate the feelings caused by the trauma and "D" criterion contains physiological hyper arousal symptoms (APA, 1987).

36 In DSM-IV, 17 symptoms of PTSD was categorized in three distinct symptom sets; re-experiencing, emotional numbing and hyperarousal. The definition of traumatic event changed, death encounter and fear related emotions became compulsory. Also in DSM-IV, the emphasis on premorbid functioning and objective severity of traumatic event were integrated and both were accepted as responsible. Subjective emotions of the patient were also emphasized and it is suggested that severest trauma would not result in PTSD if the person do not feel fear, horror or helplessness during the event (APA, 1994).

1.14. Traumatic Events and Trauma

Traumatic events and trauma are not interchangeable terms. Traumatic event can be described as an event that threat the physical or psychological integrity of a person. Trauma, on the other hand, is a unique experience of a person that overwhelms the ability to cope and results in feelings of terror and dread.

A traumatic event often involves a life threat but any event that leads the person to feel overwhelmed can have a traumatizing effect. The subjective emotional experience related to trauma determines whether an event is traumatic on the base of fright and helplessness it evokes on the person. Examining studies on trauma conducted after DSM-IV was released, Breslau et. al. (1998) found that lifetime prevalence of traumatic events ranged from 40% to 69% in the general population. On the other hand it is suggested that around 10% of the population have a history of PTSD. While

37 the majority of the population reports experiencing at least one traumatic event, only 10% to 15% of them experience PTSD.

Six factors were proposed to affect the duration and severity of the trauma response: severity of the stressor, genetic predisposition, developmental phase, social support system, prior traumatization and preexisting personality (van der Kolk, 1987). Type of trauma is also found to be related to trauma response, with the highest risk of PTSD in assaultive violence, followed by rape, sexual violence other than rape and having badly beaten up (Breslau, 1998).

Traumatic events can be divided into two main categories: human-made traumas and natural disasters. Earthquake, windstorm, floods are accepted as natural disasters, while torture, rape, severe physical harm constitutes human-made trauma.

Eight categories of trauma were suggested by Green (1993): life threat, severe physical harm, receipt of intentional harm, exposure to grotesque, sudden loss of a loved one, witnessing or learning of violence to a loved one, learning of exposure to a noxious agent, causing death or severe harm to another.

McFarlane & Girolamo (1996) categorized traumatic experiences based on their process into three categories. First one includes events that are acute like rape, in which the trauma is unexpected and highly intense. The second one has cumulative effect over time; as working in emergency

38 services. The third category is long-lasting exposure which causes feelings of powerlessness and uncertainty; as in captivity or war.

The subject matter of this dissertation is torture, which is one of the most extreme forms of trauma and accepted as an assault on both mind and body of the victim. Torture is human-made trauma and has long-lasting exposure characteristic.

1.15. Consequences of Trauma

The human mind functions on implicit assumptions and personal theories which enables setting goals, planning activities and order everyday life. The traumatic event force the victim to recognize, objectify and examine these basic assumptions. As it evokes stress and anxiety, this new experience cannot be readily assimilated and already existing assumptions remain incapable. Response to trauma can be described as shattering the victims' assumptions on their beliefs in personal invulnerability, in a meaningful world and in their positive self-perceptions (Janoff-Bulman, 1985).

Thus victimization leads to a disequilibrium and the victim needs to reestablish a conceptual system to adapt the situation and function effectively. Reestablishing an understanding of the world as meaningful and regaining positive self-image is crucial for coping. Trauma victims are faced with intrusive and repetitive thoughts about the traumatic event. From a functional perspective, Horowitz suggested that humans have a completion tendency that integrates reality with their schemas. The information

39 regarding the trauma is integrated and stored in active memory until the completion. Then the traumatic experience becomes part of long-term models which leads the repetitions and intrusions to disappear (1980; as cited in Janoff-Bulman, 1985).

When the person is not able to integrate traumatic experiences, they may cause many psychiatric disorders; mainly PTSD, depression and anxiety disorders (Raghavan, Rasmussen, Rosenfeld and Keller, 2013). PTSD is generally associated with comorbid disorders; it is suggested that around 90% of individuals with PTSD meet the diagnostic criteria for also another disorder, which is often viewed as 'secondary to PTSD' (Shalev and Yehuda, 1998).

Comorbid major depressive disorder (MDD) has always been linked with PTSD and trauma survivors frequently report depressive symptoms (Shalev and Yehuda, 1998). Furthermore, the presence of comorbid depression is observed to predict the chronicity of PTSD (Breslau et. al., 1991). Trauma victims are also observed to have substance use disorders and personality impairment (Brady, Killeen, Brewerton and Lucerini, 2000). Changes in personality is clinically observed in victims of trauma (Shalev and Yehuda, 1998)

1.16. Post-traumatic Stress Disorder

When victims are not able to integrate the trauma experience, they can suffer from reexperiencing symptoms. These symptoms can be emotionally so overwhelming that they may lead the victim to emotional

40 numbing or behavioral avoidance in order to cope with the effects of post-trauma. Further to that, repressed memories and feelings of trauma victims can cause hyperarousal. As a result of these reexperiencing, numbing of responsiveness, avoidance and hyperarousal symptoms; some victims develop PTSD.

A traumatic event has many consequences in the victims' psychological, sociological and physiological world; and PTSD seems to be the most common result. The concept of PTSD seems to be successfully applied to both the assessment and clinical treatment of the consequences of traumatic experiences (Johnson and Thompson, 2008). The epidemiologic studies on these applications will give a deeper understanding.

1.17. Epidemiology of PTSD

Experiencing a traumatic event is so common among the community. Yehuda et. al. suggested that almost 90% of the population will experience a traumatic event in their lives (1998; as cited in Stein, Tran, Lund, Haji, Dashevsky & Baker, 2005). However only less than 10% of trauma victims have PTSD (Breslau, 2009). PTSD rates seem to be surprisingly low; different studies give a range from 5% to 35% (McKeever & Huff, 2003).

Breslau (1998) examined different epidemiological studies of the general population and found different rates in estimates of lifetime exposure to traumatic events and PTSD. Studies following DSM-IV found life time prevalence of exposure to traumatic events ranged from 40% to

41 69%, whereas in studies using single-question to determine exposure lower estimates were found. Lifetime prevalence seems to be higher in males than females.

Estimates of the risk of developing PTSD seems to vary considerably across studies, but they do not exceed one quarter of those exposed (Breslau, 1998). Also the type of trauma has an impact on the risk of PTSD. The highest risk seems to be related with types of assaultive violence which are rape, sexual assault other than rape and having badly beaten up. The lowest risk of PTSD is related to learning about traumatic events experienced by a loved one. It is suggested that females have a higher risk of developing PTSD (Zlotnick, Johnson, Kohn, Vicente, Rioseco & Saldivia, 2006). Breslau (2009) states that there is no direct evidence on the sex difference and greater vulnerability to PTSD in females needs further research.

1.18. Trauma Studies

Psychological consequences of torture is observed as short-term effects as well chronic symptoms even after years. The psychological consequences remain consistent after physical signs of torture alleviate. Nadler and Ben-Shushan (1989) found that survivors of the Holocaust who were prisoners in the concentration camp for at least 12 months were still experiencing psychological problems such as depression even after 40 years. Moreover, a study on Israeli veterans who were held in captivity