INSTITUTE OF EDUCATIONAL SCIENCES

DEPARTMENT OF ENGLISH LANGUAGE TEACHING

DETERMINING THE LEVEL OF PRAGMATIC AWARENESS OF

TURKISH ELT TEACHER TRAINEES: A CASE STUDY ON

REFUSALS OF REQUESTS

MA THESIS

By

Sinem HERGÜNER

INSTITUTE OF EDUCATIONAL SCIENCES

DEPARTMENT OF ENGLISH LANGUAGE TEACHING

DETERMINING THE LEVEL OF PRAGMATIC AWARENESS OF

TURKISH ELT TEACHER TRAINEES: A CASE STUDY ON

REFUSALS OF REQUESTS

MA THESIS

By

Sinem HERGÜNER

Supervisor

Prof. Dr. Abdulvahit ÇAKIR

i

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

I must express my deepest gratitude to my supervisor Prof. Dr. Abdulvahit ÇAKIR for his guidance, feedback and encouragement throughout this study.

I am grateful to Asst. Prof. Dr. Cemal Çakır for his useful suggestions about the study. I’m also grateful to Prof. Dr. Şükriye RUHİ and from whom I have received vast amount of help in clarifying my ideas. I would like to thank them for their assistance and being so generous with their time.

I offer sincere thanks to my dear teacher Dr. Neslihan ÖZKAN, Res. Asst. Sinan ÖZMEN and Res. Asst. Cem BALÇIKANLI who always helped me at each and every stage of my study for their suggestions, encouragement and understanding for this study.

I also want to thank Asst. Prof. Dr. Bülent ALTUNKAYNAK and Res. Asst. Mustafa ALTUNSOY for the statistic part of my thesis.

I really want to thank my dear friend Ece ÇİTFÇİ who helped me collect the data.

My special thanks go to my beloved friend Sinan DEMİRBAŞ, who helped me to collect the data and made this research possible, for his invaluable support, encouragement and patience throughout every moment of my life and this thesis.

Finally, my most heartfelt gratitude goes to all my family members whose endless love and faith I feel in me and who were always there when I needed and granted me every support I needed.

ii ÖZET

TÜRK İNGİLİZCE ÖĞRETMEN ADAYLARININ EDİMBİLİMSEL FARKINDALIK DÜZEYLERİNİN BELİRLENMESİ: RİCALARIN REDDİ

ÜZERİNE BİR ARAŞTIRMA Hergüner, Sinem

Yüksek Lisans, İngiliz Dili Eğitimi ABD Tez Danışmanı: Prof. Dr. Abdulvahit ÇAKIR

Mayıs , 2009

Bu araştırmada İngilizce öğretmen adaylarının edim bilimsel farkındalıkları değerlendirilmiştir. Çalışmada İngilizce öğretmen adaylarının reddetme strateji seçimleri değerlendirilmiştir. Bulgular istatiksel olarak analiz edilmiştir. Veriler semantik bir çözümleme şemasına göre ele alınmıştır. Çalışma öğretmen adaylarının on sekiz farklı durumdaki reddetme stratejilerinin doğrudanlık ve dolaylılık açısından değerlendirilmelerini esas almaktadır. Her durum 3 değişkene dayanmaktadır. Bunlar cinsiyet (aynı-farklı), sosyal statü (düşük-eşit-yüksek) ve sosyal yakınlıktır (yakın-tanıdık-yabancı). Her durum farklı bir üçlü birleşimden oluşur.

Beş bölümden oluşan çalışmanın birinci bölümü çalışmanın kuramsal çerçevesini sunmaktadır. Ayrıca, bu bölümde çalışmanın amacı, kapsamı ve çalışmada kullanılan veri toplama ve değerlendirme yöntemleri ele alınmaktadır. Çalışmanın ikinci bölümü, konuyla ilgili kaynak ve veri taramasını içermektedir. Bu bölüm genel olarak Pragmatizm üzerinde durarak dayandığı yaklaşımları açıklamaktadır. Üçüncü bölüm, çalışmanın metodunu açıklamaktadır. Dördüncü bölümde toplanan verilerin analizine yer verilmektedir. Son olarak beşinci bölümde ise çalışmanın kısa bir özeti yapılarak çeşitli öneriler sunulmaktadır.

Çalışma sonucunda elde edilen bulgular göstermektedir ki; İngilizce öğretmen adayları açısından “reddetme ifadeleri” bazı problemlere yol açmaktadır. Bu çalışma ile Türk İngilizce öğretmen adaylarının belirli bağlamlarda “reddetme stratejileri” açısından edim bilimsel farkındalıklarının yükseltilmesi gerekliliği ortaya konmaktadır.

iii ABSTRACT

DETERMINING THE LEVEL OF PRAGMATIC AWARENESS OF ELT TEACHER TRAINEES: A CASE STUDY ON REFUSALS OF REQUESTS

HERGÜNER, Sinem

MA, English Language Teaching Department Supervisor: Prof. Dr. Abdulvahit ÇAKIR

May, 2009

In this thesis, pragmatic awareness of Turkish English Language Teaching (ELT) teacher trainees has been assessed. Turkish ELT teacher trainees were assessed from the aspect of the choice of refusal strategies for requests in terms of directness and indirectness. The findings were analyzed statistically and interpreted. The data were analyzed according to a semantic formula. The study elicited judgments of various refusal formulations of the trainees in eighteen different situations in terms of directness and indirectness. The context of each situation was based on three variables with different levels. These were gender (same-opposite), social status (low-equal-high), and social distance (intimate-acquaintance-stranger). Each of the eighteen situations had a different triplet of these variables.

This study comprises five chapters. The first chapter offers the background to the study as well as the aim, the scope of the study and the methods. In the second chapter, the literature review is presented. In general, the chapter focuses on Pragmatic features and language functions. The third chapter presents the research methodology of the study. In the fourth chapter the data analysis and the interpretation of the results are presented. Finally, in the fifth chapter, a brief summary of the study is covered and implications of the study are mentioned.

The findings of this study indicate that some aspects of refusals may cause difficulties for ELT teacher trainees. This study suggests the need to raise the pragmatic awareness of Turkish ELT teacher trainees regarding the use of refusal strategies in particular contexts.

iv Eğitim Bilimleri Enstitüsü Müdürlüğü’ne;

Sinem HERGÜNER’E ait DETERMINING THE LEVEL OF PRAGMATIC

AWARENESS OF TUKISH ELT TEACHER TRAINEES: A CASE STUDY ON REFUSALS OF REQUESTS başlıklı tezi jürimiz tarafından İngiliz Dili Eğitimi Anabilim Dalı Yüksek Lisans Tezi olarak kabul edilmiştir.

Adı Soyadı İmza

Üye (Tez Danışmanı): ... ...

Üye : ... ...

v

TABLE OF CONTENTS

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS ……… ...i

ÖZET ………. ii

ABSTRACT ………..iii

SIGNITURE PAGE OF THE JURY ……….iv

TABLE OF CONTENTS ………...v

LIST OF TABLES ………... viii

LIST OF FIGURES………ix LIST OF ABBREVIATIONS……….x CHAPTER I ... 1 INTRODUCTION ... 1 1.0. Presentation ... 1

1.1. Background to the Study ... 1

1.2. Problem of the Study ... 2

1.3. Aim of the Study ... 3

1.4. Importance of the Study ... 4

1.5.Scope of the study ... 6

CHAPTER II ... 7

REVIEW OF LITERATURE ... 7

2.0.Presentation ... 7

2.1. Discourse Analysis ... 7

2.1.1 Speech Acts ... 9

2.1.2. Classification of Speech Acts ... 10

2.1.3. The Speech Act Set ... 13

2.1.4. The Speech Act Set of Refusals ... 13

2.1.5. The State of Universality ... 17

2.2. Politeness Theory ………...………...18

2.2.1 The notion of face ... 19

2.2.2 Face-threatening Act ... 20

2.2.3 The principle of Cooperation ... 22

2.2.4. Directness versus Indirectness ... 23

2.2.5. Factors affecting directness and indirectness ... 26

vi

2.2.7. Pedagogical Implications ... 29

2.2.8. Transfer from L1 to L2 in the use of Speech Acts ... 31

2.3. Culture in Comunication ... 35

2.4. Culture in the EFL setting ... 36

2.5. Pragmatics ... 37

2.5.1. Pragmatic Competence... 38

2.5.2. Why to help students to acquire pragmatic competence ... 39

2.5.3.Relevance Theory... 40 2.5.4.Inappropriateness ... 41 CHAPTER III ... 44 METHOD ... 44 3.0 Presentation ... 44 3.1 Introduction ... 44 3.2. Subjects ... 44

3.3. Concept and Limitations ... 45

3.4. The Instruments and Data Collection ... 45

CHAPTER IV ... 48 DATA ANALYSIS ... 48 4.0. Presentation ... 48 4.1. Pilot Study ... 48 4.2. Data Interpretation ... 48 4.2.1 Preliminary results ... 49

4.2.2. Data by social status of Universities ... 64

4.2.3 Data for Social Distance of Universities ... 81

4.2.3. Data for Gender of Universities ... 97

CHAPTER V ... 114

CONCLUSION ... 114

5.0. Presentation ... 114

5.1. General discussion ... 114

5.2 Discussion of social status ... 115

5.3 Discussion of social distance ... 116

vii

5.5 Conclusion ... 117

5.6. Recommendations for future research ... 118

5.7. Implications on ELT ... 119

REFERENCES ……… 122

APPENDICES Appendix A Discourse Completion Task for Female Trainees …………..…..134

Appendix B Discourse Completion Task for Male Trainees………. 137

Appendix C Classification of SARs Used in the Data Analysis ………….…...140

viii

LIST OF TABLES

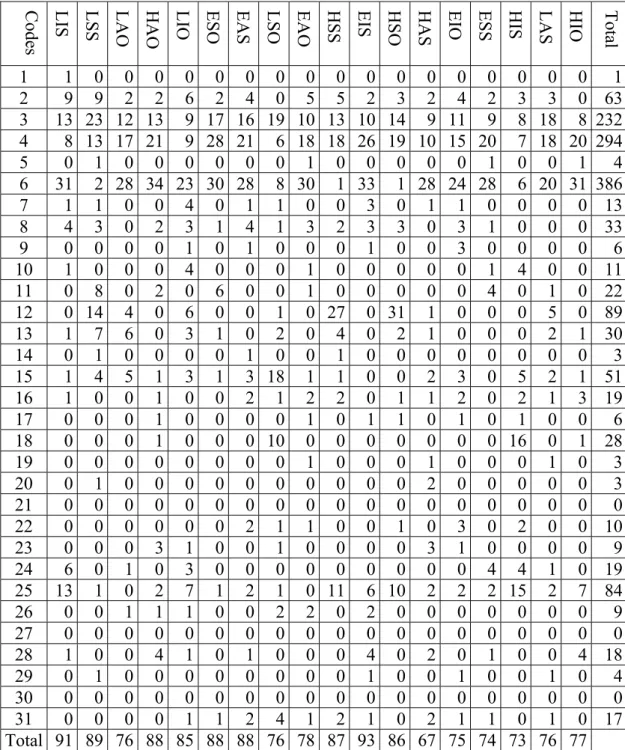

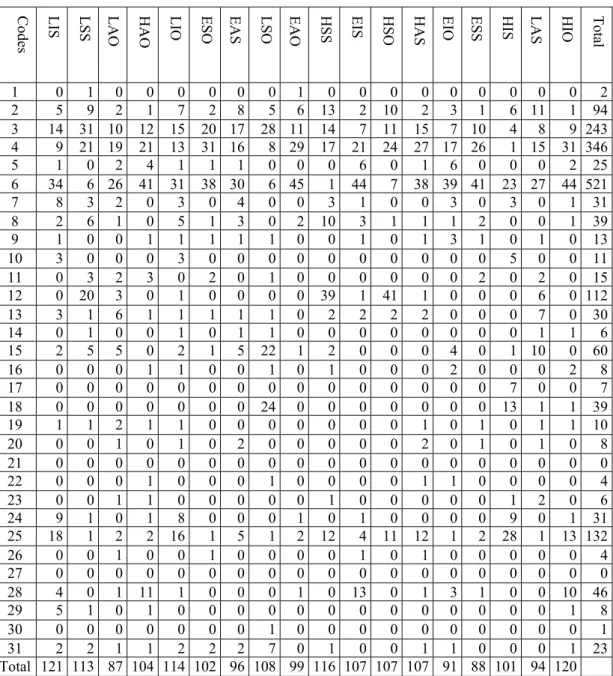

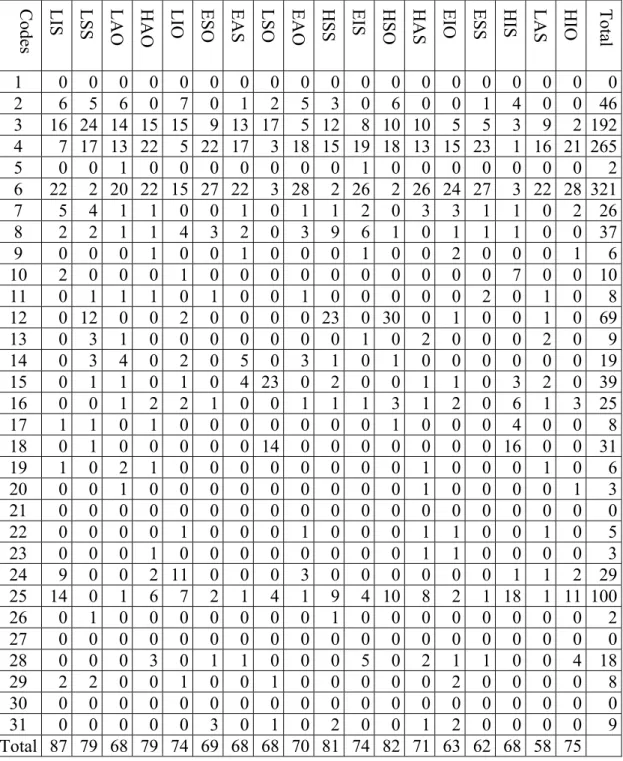

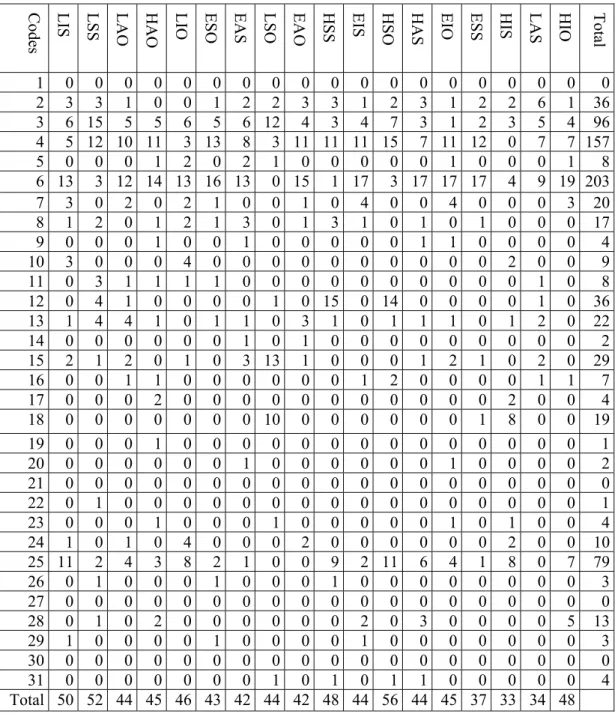

Table 1. Summary: Use of SARs by trainees of Başkent University………50

Table 2. Summary: Use of SARs by trainees of Gazi University………..52

Table 3. Summary: Use of SARs by trainees of Middle East Technical University.55 Table 4. Summary: Use of SARs by trainees of Hacettepe University…………...58

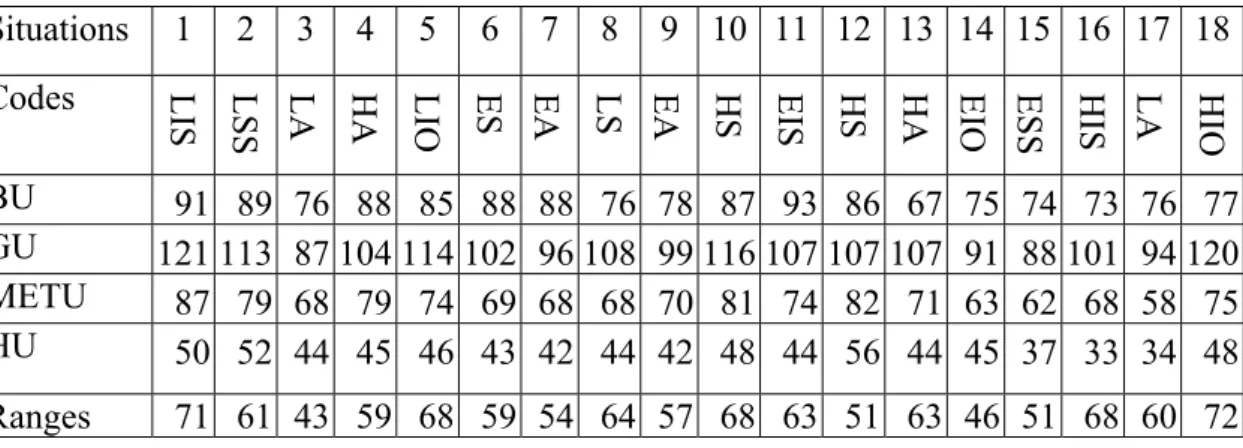

Table 5. Ranges of Universities in terms of the number of SARs……….60

Table 6. Comparisons of SARs by Universities………....62

Table 7. Başkent University by social status (by SARs)………...65

Table 8. Gazi University by social status (by SARs)………68

Table 9. METU by social status (by SARs)………..71

Table 10. Hacettepe University by social status (by SARs)………..74

Table 11. Universities by social status (by interlocutors)……….….76

Table 12. Universities by social status (by SARs)………....78

Table 13. Başkent University by social distance (by SARs)………...82

Table 14. Gazi University by social distance (by SARs)………...85

Table 15. METU by social distance (by SARs)……….……88

Table 16. Hacettepe University by social distance (by SARs)………..91

Table 17. Universities by social distance (by interlocutors)……….….93

Table 18. Universities by social distance (by SARs)……….…95

Table 19. Başkent University by gender (by SARs)………..99

Table 20. Gazi University by gender (by SARs)………...102

Table 21. METU by gender (by SARs)………...105

Table 22. Hacettepe University by gender (by SARs)………108

Table 23. Universities by gender (by interlocutors)………110

ix

LIST OF FIGURES

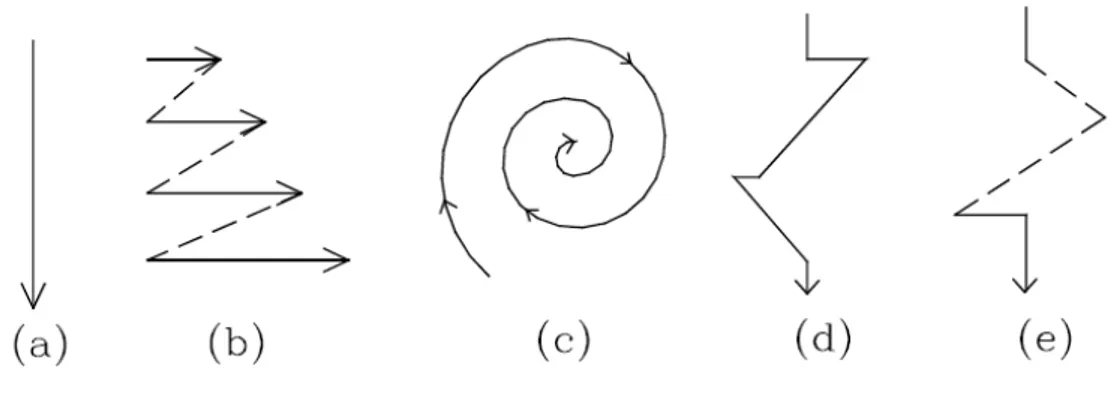

Figure 1. Types of Kaplan’s diagrams……….…..24

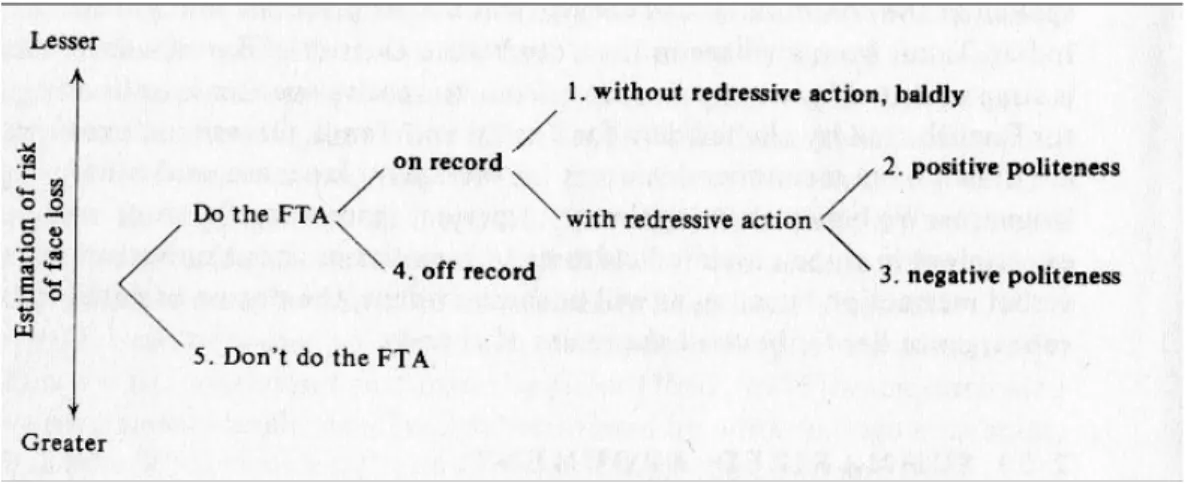

Figure 2. Selection of strategies following an FTA……….…..25

Figure 3. Leech’s indirectness scale ………....26

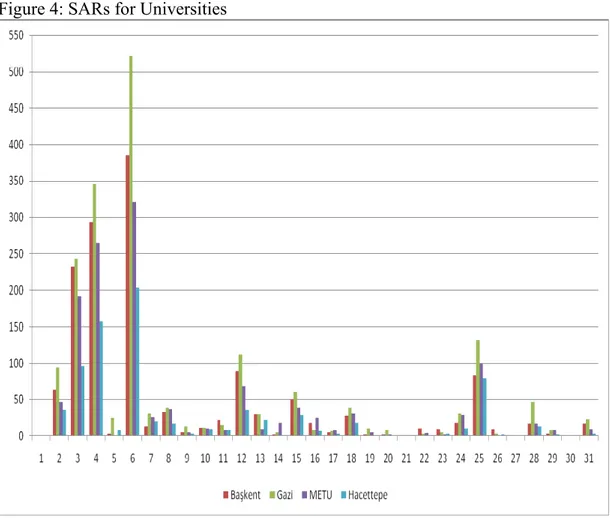

Figure 4. SARs for Universities………...61

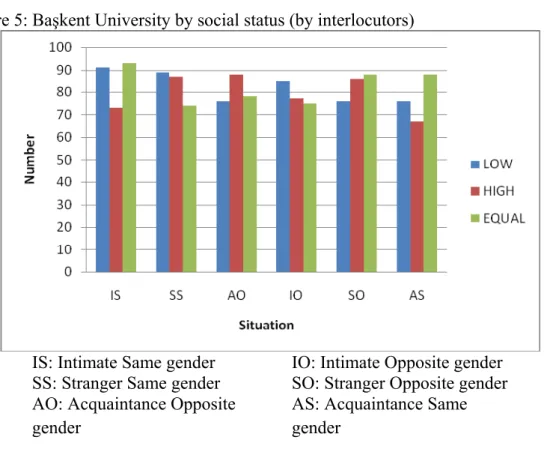

Figure 5. Başkent University by social status (by interlocutors)………...64

Figure 6. Gazi University by social status (by interlocutors)………....67

Figure 7. METU by social status (by interlocutors)………..70

Figure 8. Hacettepe University by social status (by interlocutors)………73

Figure 9. Başkent University by social distance (by interlocutors)………...81

Figure 10. Gazi University by social distance (by interlocutors)………...84

Figure 11. METU by social distance (by interlocutors)………87

Figure 12. Hacettepe University by social distance (by interlocutors)………..90

Figure 13. Başkent University by gender (by interlocutors)………..97

Figure 14. Gazi University by gender (by interlocutors)……….100

Figure 15. METU by gender (by interlocutors)………...104

x

LIST OF ABBREVIATIONS

DCT Discourse Complation Task ELT English Language Teaching ESL English as a Second Language EFL English as a Foreign Language

TEFL Teachers of English as a Foreign Language L1 First Language

L2 Second Language BU Başkent University GU Gazi University HU Hacettepe University

CHAPTER ONE

INTRODUCTION

1.0. Presentation

In this chapter, first a pertinent background of the present study is given. Next, the problem of the study, the aim of the study, importance of the study and scope of the study are presented. Finally the method and hypotheses which guided the research are stated.

1.1. Background to the Study

Thomas defines pragmatic competence as ‘the ability to use language effectively in order to achieve a specific purpose and to understand language in context’ (Thomas, 1983: 94) and she distinguishes between pragmalinguistic and socio-pragmatic competence. Pragmalinguistic competence refers to the use of appropriate language to accomplish a speech act, whereas socio-pragmatic competence refers to the appropriateness of a speech act in a particular context.

This study is an example of a pragmalinguistic area.

Refusing, a central issue in intercultural communication is potentially risky and generates tension in intercultural interactions. The more intercultural exchanges, such as travel, globalization and international interactions grow, the bigger the potential for intercultural miscommunication through misinterpreted refusals is. However, such a misunderstanding maybe interpreted as impoliteness.

As stated in Nguyen’s (2006) study to enhance understanding across cultures as well as language teaching and learning, there is a real need for specific study in the field of applied linguistics.

Refusals have been chosen as the topic of the present study. Refusals are important to everday communication due to their communicatively central place.

Besides, it is often difficult to reject requests. What is much harder is to reject them in a foreign language without risking offending the interlocutor because this involves both linguistic knowledge and pragmatic knowledge. One can have a wide range of vocabulary and a sound knowledge of grammar, but misunderstandings can still arise if the pragmatic competence cannot be applied appropriately (Nguyen, 2006).

As the advancement of the linguistic theories does not provide enough information in terms of the development of pragmatic competence it is a need to take into account the social cultural aspects of learning a foreign language in order to ensure successful and effective communicating in the target language. Furthermore, students need to be competent both in understanding and producing utterances that are appropriate to the various contexts.

In the process of teaching and learning a foreign language, in addition to the questions of 1) Is this grammatically correct? 2) Is the pronunciation acceptable? We should also add the question: Is this pragmatically appropriate to the particular context? (Bai, September 2003).

There are also important applications of this research in terms of training and teaching, which are of great strategic importance to Turkish policies in foreign language education, and especially English-language teaching.

Refusals are considered to be a face-threatening act (FTA) among the speech acts. The positive or negative face of the speaker or listener is risked when a refusal is called for or carried out. Consequently, refusals, as sensitive and high- risk, can provide much insight into one’s pragmatics, so “to perform refusals is highly indicative of one’s nonnative pragmatic competence”. (Al-Kahtani, 2006: 35)

1.2. Problem of the Study

Teaching a foreign language specifically in an EFL setting surely requires more than a conscious focus on the grammatical aspects of language, which can be

defined as learning about language. However, it is a mere fact that achieving a communication can only be attained when the attention of the learners is directed to social and pragmatic use of the language, which can be defined as learning language. To this end, teaching speech acts may be a great supporter in a process through which learners are led to develop their pragmatic competence. As one of the aspects of speech acts, refusal strategies are to be taught to EFL students for various reasons. No doubt that teaching refusal strategies, specifically ‘refusals of requests’, will provide ELF students with the golden opportunity of being and becoming as appropriate as possible in authentic communication contexts. In this respect, measuring the refusal strategies employed by the teacher trainees gain great importance on the grounds that they will be the representatives and most alive resources of the language for the language learners in the future.

Therefore, it is widely accepted that EFL learners should be directed to the pragmatic aspects of the language throughout their learning experience. The actors and actresses of the target language, the EFL teachers, are surely the most important sources of both language and the effective ways and means of learning it. Hence, most of the burden still remains on the shoulders of the pre-service education. Pre-service education is considered to be the most important step in a teacher’s professional life, in which most of the beliefs, strategies, dispositions and skills of teaching a foreign language is acquired. This fact leads us to the problem that the knowledge and language competencies of the teacher trainees on pragmatic competence, specifically refusals of request, identified as the research variable of this study, should first be measured so as to decide on a possible remedy in the further research studies.

1.3. Aim of the Study

The goal of the present study is to find out the level of pragmatic awareness of English Language Teaching teacher trainees (henceforth ELT) in terms of directness and indirectness by implementing a Discourse Completion Task to

investigate three variables which the literature has identified in other intracultural and intercultural communication acts - social status, social distance and gender.

This study specifically aims to assess Turkish ELT teacher trainees’ competency in using speech acts set of refusals in terms of directness from the aspect of pragmalinguistics in a Turkish context. To achieve this main goal, this study is supposed to answer the following questions:

• Do strategies of refusals of requests employed by teacher trainees reflect social status difference?

• Do strategies of refusals of requests employed by teacher trainees reflect social distance difference?

• Do strategies of refusals of requests employed by teacher trainees reflect gender difference?

• Does social statue display divergence in terms of directness? • Does gender display divergence in terms of directness?

• Does social distance display divergence in terms of directness? • Do they mostly use direct or indirect strategies?

Hypothesis

1. Interlocutor status, especially higher status, has a greater effect on refusal strategies.

1. Refusals towards different genders utilize different strategies. 2. Interlocutors use more refusal strategies for intimates.

3. ELT teacher trainees from Turkish context use mostly indirect refusal strategies.

1.4. Importance of the Study

First, the speech act of refusal has not been of interest to researchers sufficiently as much as other speech acts such as requests, apologies. Nevertheless, a few studies on refusal strategies (Bebee, Takahashi and Uliss-Weltz, 1990; Chen,

1995; Murphy and Neu, 1996; Olshtain and Weinbach, 1993) have appeared in the literature. However, the speech act of refusing of requests has not been studied in terms of directness and indirectness of Turkish teacher trainees of English. Second, although there have been a number studies conducted on the speech act refusals in different countries, there are fewer studies (Bulut, 2000; Demir, 2003; Tekyıldız, 2006) carried out in the Turkish context. Therefore, it is necessary to conduct similar studies on refusal strategies used by Turkish teacher trainees of English in order to contribute to the literature.

As Çakır (2006: 154) pointed that “communicating internationally inevitably involves communicating interculturally as well, which probably leads us to encounter factors of cultural differences”. He also adds that such kind of differences exist in every language such as the place of silence, tone of voice, appropriate topic of conversation, and expressions as speech act functions (e.g. apologies, suggestions, complains, refusals, etc.).

To teach a language we should raise students’ pragmatic awareness by drawing their attention to the use of the language rather than only dealing with grammar structures. The situations in which misunderstandings occur due to lack of communicative competence are supposed to be weird and annoying rather than grammatical ones (Akıncı-Akkurt, 2007: 16).

Furthermore, according to Alptekin (2002), EFL educators need to consider the implications of the international status of English in terms of appropriate pedagogies and instructional materials that enable learners become successful bilingual and intercultural individuals who are able to function well in both local and international settings. Thus, what is essential to achieve a native-like competency in target language is to form a communicative atmosphere and provide a proper classroom setting.

1.5. Scope of the study

In this study the subjects are 133 ELT teacher trainees (100 female, 33 Male), who are fourth-year students of Education Faculty of ELT Department at four different universities, Gazi University (GU), Başkent University (BU), Middle East Technical University (METU), Hacettepe University (HU). The randomly chosen participants were observed to be representative of teacher trainees in Turkey in terms of the variables such as socioeconomic demography and language learning history and competencies.

CHAPTER TWO

REVIEW OF LITERATURE

2.0. Presentation

This chapter focuses on the literature which is relevant to the present study. First it examines discourse analysis, speech acts in the literature. Next, it dwells on politeness theory, the notion of face and directness and indirectness. Then, it puts emphasis on culture and pragmatic awareness.

2.1. Discourse Analysis

McCarthey (2000:5) identifies discourse analysis as “concerned with the study of the relationship between language and the contexts in which it is used, and he adds that discourse analysts study language in use: written texts of all kinds, and spoken data, from conversation to highly institutionalized forms of talk.”

McCarthey (2000) also contends that:

“most of us in a typical week will observe or take part in a wide range of different types of spoken interaction: phone calls, buying things in shops, perhaps an interview for a job, or with a doctor, or with an employer, talking formally at meetings or in classrooms, informally in cafés or on buses, or intimately with our friends and loved ones. These situations will have their own formulae and conventions which we follow; they will have different ways of opening and closing the encounter, different role relationships, different purposes and different settings. Discourse analysis is interested in all these different factors and tries to account for them in a rigorous fashion with a separate set of descriptive labels from those used by conventional grammarians. The first fundamental distinction we have noted is between language forms and discourse functions; once we have made this distinction a lot of other conclusions can follow (p.8)”

There are different indicators of function such as, grammatical and phonological forms. According to McCarthy (2000), if grammatical and

phonological forms are examined separately they function as unreliable indicators of function, however when they are taken together, and looked at in context, it is possible to come to some decision about function. So decisions about communicative function cannot solely be the domain of grammar or phonology. Discourse analysis is not entirely separate from the study of grammar and phonology. Together with their contextual use, the grammatical and phonologic elements of the structures are essential in discourse analysis.

Besides different languages, there are different ‘social languages’ in each language, as well. Gee (2001: 86) says: “what is important to discourse analysis are social languages”. He gives the example of example of physicists engaged in experiments and not speaking or writing like street-gang members engaged in initiating a new member, and neither of these speak or write like ‘new capitalist’ entrepreneurs engaged in ‘empowering front-line workers’.

Gee also says (2001: 86) “besides, each social language uses somewhat different and characteristic grammatical resources. All of us control many different social languages and switch among them in different contexts. ‘In that sense, no one is monolingual’”. He also explains that all of us fail to have mastery of some social languages that use the grammatical resources of our ‘native language’ (2001). In that sense as Gee (2001) pointed even we, native speakers, are not ‘native speakers’ of whole social languages which compose ‘our’ language.

As Gee (2001: 87) explained “it is sometimes quite hard to know whether it is best to say whether someone is switching from one social language to another (‘code switching’)”.

When the language classroom is thought to be a small world and life on its own, there is a need of many social languages there, as well. Then the teachers of English, having a model function in language teaching, should be competent at switching among these languages so as to be a good model for the learners. That’s why this kind of knowledge cannot be gained only by learning the rules. Rather one

is to be exposed to the language and then explore the structures and rules by explicit teaching of these aspects.

It’s another domain of linguistics to analyze the speech. There are many scholars who made a lot for this field.

McCarthey (2000:6) claims that “conversation analysis so called within the American tradition can also be included under the general heading of discourse analysis.” What is emphasized in conversational analysis is building structural models but the close observation of the behavior of participants in talk and on patterns recurring over a wide range of natural data.

The American saying ‘different strokes for different folks’ is really suitable to explain what is now a well-established fact in cross-cultural pragmatics-namely, that different speech communities differ in their use of language. “Apart from more traditional areas of competence, such as grammatical competence, pragmatic competence is thus also an important area to be addressed in the foreign language classroom (Bachman, 1990: 84)”. Leech (1983: 11) clarifies it stating that “to become pragmatically competent, learners confront the challenge of acquiring pragmalinguistic and socio-pragmatic competence.” Rose (1997) says the former relating to knowledge of the relevant pragmatic system (of the range of individual options available for performing various speech acts); the later referring to knowledge of the appropriate use of the pragmatic system (how to select the appropriate choice given a particular goal in a particular setting). Pragmatic aspects are, however, only addressed to a rather narrow extent in foreign language classrooms despite recent research findings which point to the teachability of many pragmatic phenomena. (Baron and Bonn, 2000: 1-2)

2.1.1 Speech Acts

Austin (1962), Searle (1969) and Grice (1975) have been influential in the study of language as social action, reflected in speech-act theory and the formulation

of conversational maxims, alongside the emergence of pragmatics, which is the study of meaning in context (Levinson, 1983; Leech, 1983).

According to Austin's theory (1962), what we say has three kinds of meaning: 1. propositional (locutionary) meaning - the literal meaning of what is said

It's hot in here.

2. illocutionary meaning - the social function of what is said 'It's hot in here' could be:

- an indirect request for someone to open the window

- an indirect refusal to close the window because someone is cold

- a complaint implying that someone should know better than to keep the windows closed (expressed emphatically)

3. perlocutionary meaning - the effect of what is said

'It's hot in here' could result in someone opening the windows

When we say that a particular bit of speech or writing is a request or an instruction or an exemplification we are mainly concentrating on what that piece of language is doing, or how the listener or reader is supposed to react; for this reason, such entities are often also called speech acts (Austin 1962 and Searle 1969).

In that sense what is mentioned about is 'functions' which means what people are doing with language is as much concerned as what they are saying.

When achieving native-like competency in target language is concerned as one of the most important aims of learning and teaching a foreign language, the importance of pragmatics and teaching and learning speech acts become clearer.

2.1.2. Classification of Speech Acts

The classification of speech acts has been handled differently by different scholars, and this resulted with many debates. Mey (1993: 131) suggests two separate criteria: the traditional syntactic classification of verbal mood (as

indicatives, subjunctive, imperatives, optative, etc), or semantic distinctions which rely on the meaning of utterances rather than their syntactic or grammatical form. According to Schmidt and Richard (1980: 332), speech acts are in essence acts and we cannot evaluate them on the basis of syntactic criteria. Thus, speech acts cannot be equated with sentences or utterances as we may perform more than one act (e.g., inform and request) with a single utterance "I'm hungry". Searle (1977: 34-38), proposed his widely accepted five-part classification. For the classification of speech acts he developed a set of criteria. Mey (1993: 152-162) enumerates Searle's (1979: 2-8) twelve different dimensions along which speech acts can be different:

1. Illocutionary point: Searle takes great care to distinguish "illocutionary point" from both "illocutionary act" (the general concept of speech act) and "illocutionary force". For the latter distinction, we can compare the difference between an "order" and a "request'”: these are different speech acts having the same point; however they are distinguished by a difference in illocutionary force. The illocutionary point for both "order" and "request” is "to get someone to do something".

2. Direction of "fit": it conceptualizes a relation between the "word" (language) and the "world” (reality), and it can be construed either from language to reality, or from reality to language: we either "word the world” or "world the word".

3. Expressed psychological state: A state of mind, such as a "belief can be expressed in a number of different ways, using different speech acts:

“If one tries to do a classification of illocutionary acts based entirely on differently expressed psychological states,... one can get quite a long way. Thus, belief collects not only statements, assertions, remarks, and explanations, but also reports, claims, deductions, and arguments” (Searle l977: 29).

It is not possible to express a psychological state using a speech act without being in that particular psychological state. Whatever the speech act is whether an assertion, a deduction, an argument etc, and the performance of it by the speaker means that the speaker himself believes what he utters.

4. Force: This can be explained as the speaker's involvement in what is uttered. For example in the sentences,

“I suggest that we go home" "I insist that we go home"

The difference is the illocutionary force (Mey, 1993: 156). In both sentences the act to be carried out is the same, but the degree of involvement on the part of the speaker is different in two sentences.

5. Social status: Any utterance has to be situated within the context of the speaker’s and the hearer’s status in the society in order to be properly understood.

6. Interests: In any speech situation, the interlocutors have different interests, and worries about different things. The speech acts that are being used in any situation should reflect these interests and worries, as a preparatory condition.

Searle’s five-way classification of illocutionary acts (1975)

• representatives: these speech acts constitute assertions carrying true or false values (e.g. assertions, claims, statements, reports);

• directives: in these speech acts, there is an effort on the part of the speaker to have the hearer do something (e.g. requests, advice, suggestions, commands); • commissives: speech acts of this kind create an obligation on the part of the

speaker; that is, they commit the speaker to doing something (e.g. promises, threats, offers);

• expressives: these speech acts express an attitude or an inner state of the speaker which says nothing about the world (e.g. apologies, congratulations, complaints, thanks, compliments);

• declarations: speech acts in which declarative statements are successfully performed and no psychological state is expressed (e.g. an excommunication, decrees, declarations).

Downgraders often occur as the speaker attempts to lessen the imposition of a particular request on the hearer and provide him/her with as much freedom of will as possible. In other words, downgraders soften the impact of the request on the addressee, and so increase the relative level of indirectness, and thus also of politeness (Anne Baron, 2000: 8).

2.1.3. The Speech Act Set

A speech act set is a combination of individual speech acts that, when produced together, comprise a complete speech act (Murphy and Neu, 1996). Often more than one discrete speech act is necessary for a speaker to develop illocutionary force. To illustrate, in the case of a refusal, one might appropriately produce three separate speech acts: (1) an expression of regret, “I’m so sorry,” followed by (2) a direct refusal, “I can’t come to your graduation,” followed by (3) an excuse, “I will be out of town on business” (Chen, 1996).

2.1.4. The Speech Act Set of Refusals

“Refusals have been called a "major cross-cultural ‘sticking point' for many nonnative speakers" (Beebe, Takahashi & Uliss-Weltz, 1990: 56). “Due to their inherently face threatening nature, refusals are of an especially sensitive nature, and a pragmatic breakdown in this act may easily lead to unintended offense and/or breakdowns in communication” (Sadler and Eröz.: 53).

In addition to this, “their form and content tends to vary depending on the type of speech act that elicits them (request, offer, etc.), and they usually vary in

degree of directness depending on the status of the participants” (Beebe et al., 1990: 56).

The speech act of refusal occurs when a speaker directly or indirectly says no to a request or invitation. Refusal is a FTA to the listener/requestor/inviter, because it contradicts his or her expectations, and is often realized through indirect strategies. Thus, it requires a high level of pragmatic competence (Chen, 1996).

“‘Refusal’ means the speech act of saying ‘no’, expressing the addressee’s non-acceptance, declining of or disagreeing with a request, invitation, suggestion or offer. More clearly, ‘refusing means, essentially, saying ‘no, I will not do it’ in response to someone else’s utterance, in which he has conveyed to us that s/he wants us to do something and that s/he expects us to do it.” (Wierzbicka, 1987: 94)

As Brown and Levinson (1987) stated refusing can challenge the pragmatic presuppositions of the preceding utterance. “This FTA leads to a tendency on the part of the speakers to make use of certain strategies such as indirectness and polite expressions in order to avoid conflict.” (Brown and Levinson, 1987: 68).

Conversation Analysts say that there is a relation between acts, and that conversation contains frequently occurring patterns, in pairs of utterances known as ‘adjacency pairs’. They say that the utterance of one speaker makes a certain response of the next speaker very likely. The acts are ordered with a first part and a second part, and categorized as question-answer, offer-accept, blame-deny and so on, with each first part creating an expectation of a particular second part. This is known as preference structure: each first part has a preferred and a dispreferred response. (John Cutting, 2000)

“The most common adjacency pairs are greeting-greeting, thanking-response, request-refusal/acceptance, apology-acceptance, and question-answer. In terms of pragmatics, requests and refusals are automatic sequences in the structure of the conversation which are called “adjacency pairs”. (Nguyen, 2006)

Schegloff and Sacks (1973: 298) also says:

“Managing adjacency pairs successfully is part of ‘conversational competence’. By producing an adjacently positioned second part, speakers can show that they can understand what the first speakers aim at and that they are willing to go along with that. The interlocutors can also assert their failure to understand, or disagreement. Otherwise, the first speakers may think that they misunderstand”

In this study the adjacency pair of request-refusal is on the focus. This is an important adjacency pair in that refusing is an FTA, and therefore demands special attention from the speakers so that the message can be conveyed in a socially acceptable manner.

As Nguyen (2006: 17) pointed in her study, “requests are pre-event acts whereas refusals are post-event acts. In everyday life, it is not easy to refuse. A flat refusal may be interpreted as more than just the refusal itself. In contrast, it can create a feeling of discomfort both on the part of the requester and requestee.”

Classification of Refusals by Beebe & Takahashi (1990: 72-73) I. Direct:

A. Performative

B. Non-performative statement 1.“No”

2.Negative willingness ability II. Indirect

A. Statement of regret B. Wish

C. Excuse/reason/explanation D. Statement of alternative 1.I can do X instead of Y

2.Why don’t you do X instead of Y

E. Set condition for future or past acceptance F. Promise of future acceptance

G. Statement of principle H. Statement of philosophy I. Attempt to dissuade interlocutor

1.Threat/statement of negative consequences to the requester 2.Guilt trip

3.Criticize the request/requester, etc.

4.Request for help, empathy, and assistance by dropping or holding the request. 5.Let interlocutor off the hook

6.Self defense

J. Acceptance that functions as a refusal 1.Unspecific or indefinite reply

2.Lack of enthusiasm K. Avoidance 1.Nonverbal 2.Verbal a. Topic switch b. Joke

c. Repetition of part of request, etc. d. Postponement

e. Hedging f. Ellipsis g. Hint

Adjuncts to Refusals

1. Statement of positive opinion/feeling or agreement 2. Statement of empathy

3. Gratitude/appreciation

In this study one more strategy, Rhetorical Question, which often occurred in the data and was pointed in Nguyen’s (2006) study as well, is added as the 31st strategy to the Semantic Formula to analyze the data.

2.1.5. The State of Universality

While Austin (1962), Searle (1969, 1975) and Brown & Levinson (1987) have argued that speech acts are operated by universal pragmatic principles, others have shown them to vary in conceptualization and verbalization across cultures and languages (Wong, 1994; Wierzbicka, 1985). “Only for the last fifteen years there has been a remarkable shift from an intuitively based approach to an empirically based one, which has focused on the perception and production of speech acts by learners of a foreign language at varying stages of language proficiency and in different social interactions” (Cohen, 1996: 385). Blum Kulka et. all., (1989) argue that there is a strong need to complement theoretical studies of speech acts with empirical studies, based on speech acts produced by native speakers of individual languages in strictly defined contexts.

The illocutionary choices embraced by individual languages reflect what Gumperz (1982) calls “cultural logic”.

“The fact that two speakers whose sentences are quite grammatical can differ radically in their interpretation of each other’s verbal strategies indicates that conversational management does rest on linguistic knowledge. But to find out what that knowledge is we must abandon the existing views of communication which draw a basic distinction between cultural or social knowledge on the one hand and linguistic signaling processes on the other (Gumperz, 1982: 185-186).

Differences in “cultural logic” embodied in individual languages involve the implementation of various linguistic mechanisms. As numerous studies have shown, these mechanisms are rather culture-specific and may cause breakdowns in inter-ethnic communication. Such communication breakdowns are largely due to a language transfer at the socio-cultural level where cultural differences play a part in selecting among the potential strategies for realizing a given speech act. Hence there is a need to make the instruction of speech acts an instrumental component of every ESL/EFL curriculum.

2.2 Politeness Theory

In pragmatics, when we talk of ‘politeness’, we do not refer to the social rules related to behavior such as opening the door for others, or leaving your place for old people on the bus.

Early work on politeness by Goffman (1967: 77) describes politeness as “the appreciation an individual shows to another through avoidance or presentation of rituals” Lakoff (1973) suggests that if one wants to succeed in communication, the message must be conveyed in a clear manner. Fraser and Nolan (1981) define politeness as a set of constraints of verbal behavior while Leech (1983) sees it as forms of behavior aimed at creating and maintaining harmonious interaction. He also considers the Politeness Principle as part of the principles for interpersonal rhetoric. He presents six maxims for the Politeness Principle:

• Tact maxim: Minimize cost to other. Maximize benefit to other. • Generosity maxim: Minimize benefit to self. Maximize cost to self.

• Approbation maxim: Minimize dispraise of other. Maximize dispraise of self. • Modesty maxim: Minimize praise of self. Maximize praise of other.

• Agreement maxim: Minimize disagreement between self and other. Maximize agreement between self and other.

• Sympathy maxim: Minimize antipathy between self and other. Maximize sympathy between self and other. (Leech 1983: 132-139)

According to Brown and Levinson (1987), politeness, as a form of behavior, allows communication to take place between potentially aggressive partners.

What is common in Lakoff’s (1975), Leech’s (1983), and Brown and Levinson’s (1978, 1987) approaches is that they all claim, explicitly or implicitly, the universality of their principles for linguistic politeness. The general idea is to understand various strategies for interactive behaviors based on the fact that people engage in rational behaviors to achieve the satisfaction of certain wants.

2.2.1 The notion of face

Mills contends that politeness is the expression of the speaker’s intention to mitigate face threats carried by certain FTAs (Mills, 2003: 6). It was Erving Goffman publishing the article "On Face Work" where he first created the term “face” in 1963. He discusses face in reference to how people present themselves in social situations and that our entire reality is constructed through our social interactions. This leads into Goffman 'Face is a mask that changes depending on the audience and the social interaction (Goffman, 1967). Face is also described by Brown and Levinson (1987) as the public self image or reputation, self-esteem of a person. Brown and Levinson (1987: 66) identified face as something “that is emotionally invested, and that can be lost, maintained, or enhanced, and must be constantly attended to in interaction.” Face is maintained by the audience, not by the speaker. We strive to maintain the face we have created in social situations. Face is broken down by Goffman into two different categories. Positive face is the desire of being seen as a good human being and negative face is the desire to remain autonomous. Brown and Levinson (1987) also defined the former as related to the want to be approved of by other people, which is associated with one’s desire for approval on the other hand the latter as the want to interact without being impeded by others which represents the desire for autonomy.

Ritual constraints on communication include not only ways of presenting ‘self’ but also the ways in which we give face to others. In everyday discourse, we often defer to interlocutors by avoiding subtle and personal topics, we reassure our partners, and we avoid open disagreement. If we realize there is a misunderstanding on the part of the listeners, we clarify important items and remark background information. When we do not understand others, we give verbal or non-threatening feedback to that effect. By doing so, we are taking the ‘face’ of both ourselves and of the hearers into account.

According to Goffman (1967), there may be several reasons why people want to save their face. They may have become attached to the value on which this face

has been built, they may be enjoying the results and the power that their face has created, or they may be nursing higher social aspirations for which they will need this face. Goffman also defines ‘face work’, “the way in which people maintain their face. This is done by presenting a consistent image to other people.” Her additionally states that one can gain or lose face by improving or spoiling this image. That’s the better that image; the more likely one will be appreciated. People also have to make sure that in the efforts to keep their own face; they do not in any way damage the others’ face. (Nguyen, 2006: 8-9)

2.2.2 Face-threatening Act

Regarding the notion of face in the categorization of speech acts some are listed under the heading of Face-threatening Acts. Acts like promises, apologies, expressing thanks, even non-verbal acts such as stumbling, falling down, are considered to threaten primarily the speaker’s face, whereas warnings, criticisms, orders, requests, etc. are viewed to threaten primarily the hearer’s face.

In daily communication, people may give a threat to another individual’s self-image, or create a ‘face-threatening act’. These acts impede the freedom of actions (negative face), and the wish that one’s wants be desired by others (positive face) – by either the speaker, or the addressee, or both. “Requests potentially threaten the addressee’s face because they may restrict the addressee’s freedom to act according to his/her will” (Holtgraves, 2002: 40). Refusals, on the other hand, may threaten the addressee’s positive face because they may imply that what he/she says is not favoured by the speaker. “In an attempt to avoid FTAs, interlocutors use specific strategies to minimize the threat according to a rational assessment of the face risk to participants” (Nguyen, 2006: 9).

Goffman (1967) argues that there is a limited amount of strategies to maintain face. A threat to a person’s face has been termed a face threatening act or FTA. Brown and Levinson (1987) argue that a FTA often requires a mitigating statement

or some sort of politeness, or the line of communication will break. With this understanding of face, a definition of politeness can be understood in relation to face.

Brown and Levinson extended this idea from Goffman’s (1967) concept of Face. Since it is seen of mutual interest to save, maintain, or support each other’s face, FTAs are either avoided (if possible) or different strategies are employed to counteract or soften the FTAs. Brown and Levinson (1987) outlined four main types of politeness strategies: bald on record, negative politeness, positive politeness, and off-the-record or indirect strategy.

These different strategies are presented in the form of five superstrategies for performing FTAs:

• 1. Bald-on record: FTA performed bald-on-record, in a direct and concise way without redressive action.

e.g. imperative form without any redress: ‘Wash your hands’

• 2. Positive Politeness: FTA is performed with redressive action. Strategies oriented towards positive face of the hearer.

e.g. strategies seeking common ground or co-operation, such as in jokes or offers: ‘Wash your hands, honey’

• 3. Negative Politeness: FTA is performed with redressive action. Strategies oriented towards negative face of the hearer.

e.g. indirect formulation: ‘Would you mind washing your hands?’

• 4. Off-record: FTA is performed off-record. Strategies that might allow the act to have more than one interpretation.

• e.g. off-record strategies, which consist of all types of hints, metaphors, tautologies, etc. `Gardening makes your hands dirty`.

4. Avoidance: FTA is not performed.

“Speaking in a polite manner involves being aware of the effect a particular illocutionary force has on one’s addressee, and aggravating or mitigating this force by applying a suitable degree of modification” (Barron and Bonn, 2000: 4-5). Thus, what is essential to have a successful communication is to utilize the right level of politeness, and strategies of politeness.

2.2.3 The principle of Cooperation

Means of communication are exploited to keep the conversation progressing smoothly. In any speech act, the conversants have to follow many principles, one of which is “cooperation”. Conversation proceeds on the basis that participants are expected to deal considerately with each other. In considering the suitability of participants’ moves in conversation, Grice (1975) formulates a broad general principle, the Cooperative Principle:

“Make your conversational contribution such as is required, at the stage at which it occurs, by the accepted purpose or direction of the talk exchange in which you are engaged.” (Nguyen, 2006: 7). Thus, it is essential to cooperate as much as needed, not much or less.

Grice (1975) enumerates the four following maxims, which characterize the Cooperative Principle:

• Maxim of Quantity, or to be brief, which means that you should make your contributions as informative as is required and no more.

• Maxim of Quality, or to be true, which requires you not to say what you believe to be false or for which you lack adequate evidence. Therefore, lying is an obvious violation of the Cooperative Principle.

• Maxim of Relation, or to be relevant to the context and to what has been said previously, people who change the subject abruptly are usually considered rude or uncooperative.

• Maxim of Manner, or to be clear, which requires you to avoid ambiguity and obscurity.

“It is difficult to express a refusal without violating these principles” (Nguyen, 2006: 8). Rather than direct refusal in their daily relationships, people often utilize negotiation more subtle strategies may be required if the speaker is to convey the intended refusal without hurting the other’s feelings.

2.2.4. Directness versus Indirectness

Kaplan (1972) proposes 4 discourse structures that contrast with English hierarchy (Figure a). He concentrates mainly on writing and restricts his study to paragraphs in order to find out what he calls “cultural thought patterns”:

1- Parallel constructions, with the first idea completed in the second part (Figure b), 2- Circularity, with the topic looked at from different tangents (Figure c),

3- Freedom to digress and to introduce “extraneous” material (Figure d),

4- Similar to (3), but with different lengths, and parenthetical amplifications of subordinate elements (Figure e),

They are respectively illustrated by the following diagrams: (as cited in Nguyen, 2006)

Figure 1: Types of Kaplan’s diagrams

Each diagram represents a certain language or a group of languages. Kaplan identifies his discourse types with genetic language types, respectively.

In his diagrams, people from English-speaking countries often use direct expressions and thought patterns, and Oriental people in general and Turks in particular, seem to prefer roundabout and indirect patterns. We will examine the semantic formulae in terms of the directness-indirectness continuum employed by Turkish speakers of English. Although Kaplan himself does not now subscribe narrowly to his model, it remains influential in the second language teaching and learning environment.

This difference between languages is supposed to have an effect on the pragmatic awareness of foreign languages. Regarding the pragmatic awareness of Turkish speakers of English is highly affected by this different thought patterns.

Ide (1989: 225) points out nicely: “politeness is a neutral term. Just as ‘height’ does not refer to the state of bring ‘high’, ‘politeness’ is not the state of being ‘polite’.”

As Martı (2000) states the first super strategy (bald-on-record) is ranked as the most direct strategy. However, bald-on-record covers strategies usually using the imperative form without any redress, and is employed when face threat is minimal. On the other hand, the last strategy (avoidance), at the other end of the continuum, is

considered as the most indirect super strategy and is employed when there is maximum face-threat.

According to Brown and Levinson (1987), the lower the number preceding the strategies, the higher chance of face threat.

Figure 2: Selection of strategies following an FTA

For example, in terms of refusal speech acts:

1. Without redressive action: means direct refusals, such as “I refuse”.

2. On record (with redressive action): means to refuse explicitly with or without politeness strategy.

3. Off record: means not to refuse explicitly but give a listener a hint so that he or she can infer that the speaker means a refusal.

4. Don’t do the FTA: means giving up refusing. (Nguyen, 2006: 10) Leech’s Scales of politeness is as follows;

Leech (1983) proposed scales of politeness in order to determine politeness. One of them is the indirectness scale. Leech (1983: 108) claims that, when propositional content is kept constant, the use of more and more indirect illocutions will generally result in more politeness.

One reason for this is, according to him, the increase of optionality given to the hearer. The other reason is “the more indirect an illocution is, the more diminished and tentative its force tends to be” (Leech, 1983: 108). The indirectness scale is illustrated below:

Figure 3: Leech’s indirectness scale.

indirectness less polite Answer the phone.

I want you to answer the phone. Will you answer the phone? Can you answer the phone?

Would you mind answering the phone?

Could you possibly answer the phone? etc.

more polite

Leech’s (1983: 108) indirectness scale.

2.2.5. Factors affecting directness and indirectness

There are many socio-cultural factors affecting the directness-indirectness of utterances. Nguyen (1998) proposes 12 factors that, in his view, may affect the choice of directness and indirectness in communication:

1- Age: the old tend to be more indirect than the young. 2- Sex: females prefer indirect expression.

3- Residence: the rural population tends to use more indirectness than the urban. 4- Mood: while angry, people tend to use more indirectness.

5- Occupation: those who study social sciences tend to use more indirectness than those who study natural sciences.

6- Personality: the extroverted tend to use more directness than the introverted. 7- Topic: while referring to a sensitive topic, a taboo, people usually opt for indirectness.

8- Place: when at home, people tend to use more directness than when they are elsewhere.

9- Communicative environment/setting: when in an informal climate, people tend to express themselves in a direct way.

10- Social distance: those who have closer relations tend to talk in a more direct way.

11- Time pressure: when in a hurry, people are likely to use direct expressions. 12- Position: when in a superior position, people tend to use more directness to their inferiors. (As cited in Nguyen, 2006: 13-14)

These factors help to determine the strategies as well as the number of semantic formulae used when speakers perform the act of refusing. A semantic formula may consist of a word, a phrase, or a sentence which meets a given semantic criterion or strategy (Fraser 1981). A semantic formula is described as “ the means by which a particular speech act is accomplished, in terms of the primary content of an utterance, such as a reason, an explanation, or an alternative” (Bardovi-Harlig and Hartford ,1991: 48).

Thus, which linguistic realization we choose for making an apology or a request in any language might depend on the social status of the speaker or hearer, and on age, sex, or any other social factor.

2.2.6. Social Distance, Social Status, and Gender

Social distance is one of the factors that determine politeness behaviors (Leech, 1983; Brown and Levinson, 1987). The notion of social distance refers to the consideration of the roles people are taking in relation to one another in a particular situation as well as how well they know each other, which means the degree of intimacy between interlocutors (Brown and Levinson, 1987). They also claimed that politeness increases with social distance. On the other hand, Wolfson (1988) states that there is only a little solidarity establishing speech behavior among strangers and intimates because of the relative pre-existing familiarity of their relationship, whereas the negotiation of relationships is more likely to happen among friends.

In order to communicate effectively we need to use utterances appropriately in accordance with the kind of relationship or the kind of relationship that we want to maintain between the addresser and addressee. It might be interesting if one tries and observes how two people talk to each other at different phases of their relationship such as getting acquainted, becoming close, and breaking up. (Bai, 2003)

The role of social status in communication involves the ability to recognize each other’s social position (Leech, 1983; Brown and Levinson, 1987; Holmes, 1995). Holmes (1995) claimed that people with high social status are more prone to receive deferential behavior, including linguistic deference and negative politeness. Thus those with lower social status are inclined to avoid offending those with higher status and show more respect to them.

Gender and speech behavior are also seen as two interwoven, interrelated variables (Lakoff, 1975; Tannen, 1990; Boxer, 1993; Holmes, 1995). In other words, on the gender relationship between interlocutors speech behaviors depend. Thus it is a need to use different linguistic patterns while refusing people of either the same or the opposite gender.

The discussion of the proceeding sections illustrates that communication, getting-the-meaning across, is a complex process. As Bai (2003) states grice's theory of implicature helps us understand that our utterances often contain conversational meanings- specific to the particular context- only known to the people who are aware of the contextual force upon the utterance. In that sense, successful communication requires that both the sender and the receiver of the message be aware of the implicature, or the implied meanings, of the message.

Cooperative Principle and Theory of Implicature (Grice, 1975) are also important in helping us understand how a hearer/reader comprehend the precise meaning of a message. As previously stated the Cooperative Principle consists of four conversational maxims: quantity (enough information), quality (truthful

information), relation (relevant information) and manner (clearly stated information). When these maxims are violated an implicature arises.

An implicature can be understood only if the addresser and the addresee share the common understanding of the contextual forces. Grice (1975) distinguishes two different sorts of implicature: conventional and conversational implicature. Conversational Implicature refers to the nonconventional meaning, a particular meaning in a particular context of utterance. In other words the same utterance can have different meanings in different contexts. When we hear the word context we often regard it as textual context, which means what occurs immediately before or after the particular linguistic form in question. Context, within the framework of pragmatics, is defined as “any background knowledge assumed to be shared by addresser and addressee and which contributes to addressee’s interpretation of what addresser means by a given utterance” (Leech, 1983: 13). In other words, people who know each other well are supposed to be more successful in communication with one another thanks to the background knowledge they share. At this point social distance gains importance in the choice of linguistic strategies applied by individuals. The present study will focus on selected factors that govern the way people undertake the act of refusing in their daily conversations. These include social distance (intimate, acquaintance, stranger); social status (low, high, equal); and gender (same gender, opposite gender). It begins with the working hypothesis, based on the literature on communication and speech acts that these variables play central roles in the choice of strategies used by Turkish TEFL.

2.2.7. Pedagogical Implications

Research indicates that a level of linguistic competence is a prerequisite to pragmatic competence (Hoffman-Hicks, 1992). We cannot de-emphasize the importance of developing a solid foundation of linguistic competence. However, the discussion thus far clearly shows that the successful communication, understanding and being understood effectively by others, requires that learners of English as a

foreign language develop pragmatic competence. Research findings from the various areas of pragmatics can help us make informed decisions to maximize effective learning and teaching such as the following four phases of the Turkish curriculum:

1) Materials selection and development.

2) Presentation and explanation of the selected materials.

3) The design and implementation of learning activities that engage our students in developing strategies and tactics of interacting with Turkish culture, and

4) Out-come based assessment of how well students can interact with aspects of English culture appropriately.

For the first phase, material selection and development, we should try to include materials that are meaningful and informative and useful for the students to comprehend the language and to develop productive language competencies that are pragmatically appropriate.

For the second phase, presentation and explanation of the materials, we should examine whether or not pragmatic information and cultural contexts are utilized appropriately for making the new materials more clear and more meaningful to the students in terms of what is appropriate to say to whom and when and where, both socially and culturally. When we present new materials such as new vocabulary or grammatical patterns or discourse structures to our students, in addition to explaining the linguistic information and restrictions upon the new content, we should also provide pragmatic information to help clarify meaning. At the presentation/teaching level we should provide notes that aim at enhancing accuracy in terms of pragmatic competence for various levels.

For the third phase of our curriculum, the design and implementation of learning activities, we need to remember that fact that the development of pragmatic competence is a cognitive process. We need to examine whether or not aspects of pragmatic competence are considered. For instance;

• Are scenarios created for students to practice interacting with people in a culturally appropriate manner?

• Are students provided with opportunity of developing cultural awareness of various kinds of discourse and narrative structures?

Various media such as multimedia stimuli are helpful for this purpose. As discussed in Bai’s research (2003) learners develop communicative and pragmatic competencies as a result of communicating (not merely knowing about the culture) with others in a rich cultural environment. Students need sufficient function-based and process-oriented instruction in order to develop the necessary pragmatic competence. There is a continuum from controlled to automatic processing stage in terms of performing appropriately pragmatically. We have to take into consideration of the pragmatic component when we implement the principle of recycling or spiraling in our curriculum.

For the final phase, it should be considered whether the questions raised above are considered in assessing students’ achievement. Pragmatic component should be integrated in the process of out-come based assessment. (Bai, 2003)

2.2.8. Transfer from L1 to L2 in the use of Speech Acts

As it is not possible to separate a language from its own culture and it is impossible for speakers to depart from their native cultural values, speech styles, inferences and interpretations, what is inevitable for second language learners is to have difficulties in using their second language (L2) in linguistically and socially appropriate ways. Because of this challenge, L2 learners have a tendency to transfer speech act strategies of their first language (L1) to L2 situations while communicating. The transfer of modes of speech acts of one speech community to another community cause pragmatic failure. As Nelson et al. (2002: 171) states, “While native speakers often forgive the phonological, syntactic and lexical errors made by L2 speakers, they are less likely to forgive pragmatic errors”. Thus, a pragmatic failure results in speaker’s being regarded as rude, tackles arrogant,

impatient, and so forth. And she adds that “Furthermore, pragmatic errors can lead to a listener’s being unable to assign a confident interpretation to a learner’s utterance.” (Nelson et al. 2002: 171)

The issue of pragmatic transfer, as discussed by Beebe et al. (1990) is also of interest. While Dulay and Burt's (1974) study seemed to discredit the role of language transfer in learning an L2, this study suggests the opposite for refusals: that language transfer at the pragmatic level does exist, specifically in the form of native, discourse level socio-cultural competence.

Sadler and Eröz carried out a research and explained that based on the results of a 12 item written role-play questionnaire which required a refusal, subject responses (subjects were Japanese speaking Japanese (n=20), Japanese speaking English (n=20), and Americans speaking English (n=20) were coded using a 33 category classification system and analyzed for evidence of language transfer. The authors found evidence of negative transfer from Japanese in three areas: order of semantic formulas, the frequency of semantic formulas, and the content of semantic formulas. As it is clear in Sadler and Eröz’s study, the linguistic and pragmatic knowledge of L1 may hinder the success in L2 in terms of same aspects. However, sometimes it may be useful for the speaker.

As widely known; "Sapir and Whorf strongly advocated this interrelationship and the uniqueness and distinctiveness of each language on which the real world or culture is built (Sifianou, 1992: 44)”. It has also been claimed that “there is a large amount of variation across cultures not only at form and meaning levels, but also at the level of strategies used by speakers in verbal interaction.”(Escandelle-Vidal, 1996: 631), and Wierzbicka (1991: 25) says “the claim of universality was an illusion due to Anglo-centrically biased research, and the conventions of it have been mistakenly generalized to ‘human behavior’ in general. In her research, Wierzbicka discovered that Slavic languages, such as Polish and Russian, present severe restrictions on the use of interrogatives with an intended illocutionary force different from that of a question (1991). According to Wierzbicka (1991: 62), “in those languages a formula like ‘Can you pass the salt?’ would be understood as a genuine

question and not as a polite request, as it would be in English or Spanish”. Goffman states (1976: 266), “there is a distinction between ‘system constraints’ (constraints required for any communication system) and ‘ritual constraints’ (the ways each person is expected to handle himself with respect to others)”. He also adds that ‘system constrains’ are pancultural, whereas the latter patently depend on cultural definition and can be expected to vary from society to society.

“‘System constraints’ include norms such as those identified by Grice: be relevant, be informative, etc. (Schmidt and Richards, 1980: 139).” Hence, Goffmann mentions that any language has both universal characteristics and culture-specific characteristics, both of which are necessary in verbal communication (1976). According to Fraser (1975: 19-20) “the strategies used in performing illocutionary acts are essentially the same across languages”. However, he contends that two cultures may differ significantly on what strategy may be used appropriately in a given context. He gives the example of addressing in American and German universities. He assumes that in all cultures the presence of a title of address conveys more deference than its absence. However, cultures differ on what level of deference is required. In American universities, it is current custom to use fırst names in addressing one's students. On contrary, in German universities, the usage title "mister" or at least the use of formal "you' “sie” is required. Fraser's findings are obviously in line with Goffman's distinction between "system constraints" and "ritual constraints".

As a result of his findings, Fraser (1975: 20) also asserted “acquiring social competence in a new-language does not involve substantially new concepts concerning how languages are organized and what types of devices serve what social functions, but only new social attitudes about which strategies may be used appropriately in a given context.”

Brown and Levinson (1978, 1987) have the most detailed debate for the universality of speech act strategies. They assert that most of the speech acts are threatening either for the speaker or the hearer, by imposing on one party's freedom of action or by damaging the positive self-image of one of the parties. They argue