Comparison of extracorporeal shock wave therapy

in acute and chronic lateral epicondylitis

Correspondence: Mahir Mahiroğulları, MD. Medipol Üniversitesi Tıp Fakültesi, Ortopedi ve

Travmatoloji Anabilim Dalı, Atatürk Bulvarı, No: 27, 34830 Fatih, İstanbul, Turkey. Tel: +90 – 444 85 44 e-mail: mahirogullari@yahoo.com

Submitted: June 16, 2014 Accepted: October 08, 2014 ©2015 Turkish Association of Orthopaedics and Traumatology

Available online at www.aott.org.tr doi: 10.3944/AOTT.2015.14.0215 QR (Quick Response) Code

doi: 10.3944/AOTT.2015.14.0215

İsmet KöKsal1, Olcay Güler2, Mahir MahİrOğulları2, serhat Mutlu3,

selami ÇaKMaK4, ertuğrul aKşahİn5

1Yenimahalle State Hospital, Department of Orthopedics and Traumatology, Ankara, Turkey

2Medipol University Faculty of Medicine, Department of Orthopedics and Traumatology, İstanbul, Turkey

3Kanuni Sultan Süleyman Training and Research Hospital, Department of Orthopedics and Traumatology, İstanbul, Turkey

4Gülhane Military Medical Academy Haydarpaşa Training and Research Hospital,

Department of Orthopedics and Traumatology, İstanbul, Turkey

5Numune Training and Research Hospital, Department of Orthopedics and Traumatology, Ankara, Turkey

Objective: The aim of this study is to evaluate and compare the results of extracorporeal shock wave therapy (ESWT) in the treatment of acute (<3 months) lateral epicondylitis (LE) and chronic (>6 months) LE groups.

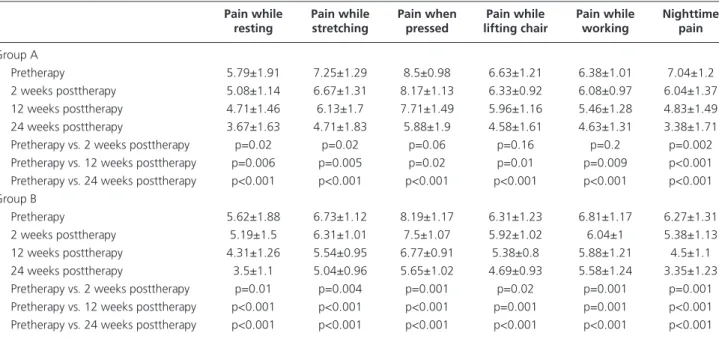

Methods: Fifty-four patients who were diagnosed with LE and treated with BTL-5000 SWT Power (BTL Türkiye Medikal Cihazlar, Ankara, Turkey) ESWT were included in the study. Twenty-four patients who had symptoms for <3 months were defined as the acute LE group (Group A), and 30 patients who had symptoms for >6 months were defined as the chronic LE group (Group B). All cases were evaluated pretherapy and at Weeks 2, 12, and 24 posttherapy according to pain while resting, pain while stretching, pain when pressed, pain while lifting chair, pain while working, nighttime pain on LE zone.

Results: Almost all values in both Group A and Group B were significantly improved at Weeks 2, 12, and 24 compared to the baseline values.

Conclusion: ESWT is equally effective in the treatment of acute LE and chronic LE. In addition, the current data suggest the progression of LE cases from acute phase to chronic phase may be prevented by treatment with ESWT.

Keywords: Epicondylitis; extracorporeal shock wave therapy; tennis elbow. Level of Evidence: Level III Therapeutic Study

Lateral epicondylitis (LE) is a pathology caused by ex-cessive use of the limbs, especially during sports and pro-fessional activities. It is characterized by pain originating from the lateral epicondyle and extending to the humer-us and forearm, as determined during physical examina-tion. It is generally observed in patients aged between

40–50 years. Its incidence is equal in men and women.[1]

While acute onset is common in young athletes, chronic phase is more common in the elderly.

LE is described as acute if symptoms are <3 months and chronic if symptoms are >6 months.[2] There are

litera-ture. In conservative therapy, nonsteroid anti-inflamma-tory medicine (NSAI), brace, forearm bandage, ultraso-nography, steroid application, low dose laser application, extracorporeal shock wave therapy (ESWT), and other methods are suggested. Surgical therapy methods are re-served for patients who cannot benefit from conservative treatment. Numerous studies show that ESWT is effec-tive in treatment of chronic persistent LE.[3–5]

Further-more, it is believed that ESWT is effective in preventing progression to the chronic phase when applied in the acute phase.

The objective of this study is to evaluate the efficien-cy of ESWT application in the treatment of acute (<3 months) LE and chronic (>6 months) LE, as well as to compare outcomes in both groups.

Patients and methods

Patients who came to the physical therapy center with a diagnosis of LE and were treated with BTL-5000 SWT Power (BTL Türkiye Medikal Cihazlar, Ankara, Turkey) ESWT between 2008–2009 were included in the study. Twenty-four patients who had symptoms for <3 months and had not been treated previously were defined as the acute LE group (Group A). Thirty patients who had symptoms for >6 months and had not benefitted from therapies such as NSAI, brace, forearm bandage, and physical therapy were defined as the chronic LE group (Group B). Patients who had local infection, were <18 years, were pregnant, had a bleeding disorder, or had been diagnosed with arthritis were excluded from the study.

ESWT application was performed without the use of local anesthesia. A shock wave with an impulse of 2.000, frequency of 5 Hz, and pressure of 2.5 bars was applied to each elbow. One session lasted 5 minutes, with an interval of 3 days between sessions. Three ses-sions were applied to each patient, and a second round of ESWT was not applied to any patient.

All cases were evaluated at Weeks 2, 12, and 24 pre- and posttherapy according to pre- and posttreatment scores. Evaluation was performed to determine pain scores. Visual analog scoring system (VAS) was used for pain scoring. The VAS scoring system was used to assess pre- and posttreatment degree of pain, which was scored from 0 (no pain) to 10 (extremely severe). Pain scores were evaluated as pain while resting, pain while stretching (defined as full flexion of the wrist), pain while lifting chair,[6,7] and pain when pressed

(de-fined as tenderness while palpation), nighttime pain (defined as pain caused awaking), pain while work-ing (defined as pain that reduces the workwork-ing perfor-mance). Pain while lifting chair was defined as the pain that occurred when a chair weighing 3.5 kg was lifted using the affected extremity while the shoulder was at a 60° anteflexion position and the elbow was extended. In this study, Statistical Package for Social Sciences for Windows 15.0 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, Illinois, USA) was used for conversion and analysis of raw data ob-tained from surveys.

Data obtained as a result of the study were compared in terms of temporal change using Wilcoxon signed-table 1. Data from Group A and Group B pre- and post-ESWT.

Pain while Pain while Pain when Pain while Pain while nighttime

resting stretching pressed lifting chair working pain

Group A

Pretherapy 5.79±1.91 7.25±1.29 8.5±0.98 6.63±1.21 6.38±1.01 7.04±1.2

2 weeks posttherapy 5.08±1.14 6.67±1.31 8.17±1.13 6.33±0.92 6.08±0.97 6.04±1.37

12 weeks posttherapy 4.71±1.46 6.13±1.7 7.71±1.49 5.96±1.16 5.46±1.28 4.83±1.49

24 weeks posttherapy 3.67±1.63 4.71±1.83 5.88±1.9 4.58±1.61 4.63±1.31 3.38±1.71

Pretherapy vs. 2 weeks posttherapy p=0.02 p=0.02 p=0.06 p=0.16 p=0.2 p=0.002

Pretherapy vs. 12 weeks posttherapy p=0.006 p=0.005 p=0.02 p=0.01 p=0.009 p<0.001

Pretherapy vs. 24 weeks posttherapy p<0.001 p<0.001 p<0.001 p<0.001 p<0.001 p<0.001 Group B

Pretherapy 5.62±1.88 6.73±1.12 8.19±1.17 6.31±1.23 6.81±1.17 6.27±1.31

2 weeks posttherapy 5.19±1.5 6.31±1.01 7.5±1.07 5.92±1.02 6.04±1 5.38±1.13

12 weeks posttherapy 4.31±1.26 5.54±0.95 6.77±0.91 5.38±0.8 5.88±1.21 4.5±1.1

24 weeks posttherapy 3.5±1.1 5.04±0.96 5.65±1.02 4.69±0.93 5.58±1.24 3.35±1.23

Pretherapy vs. 2 weeks posttherapy p=0.01 p=0.004 p=0.001 p=0.02 p=0.001 p=0.001

Pretherapy vs. 12 weeks posttherapy p<0.001 p<0.001 p<0.001 p=0.001 p=0.001 p<0.001 Pretherapy vs. 24 weeks posttherapy p<0.001 p<0.001 p<0.001 p<0.001 p<0.001 p<0.001

rank test and differences between groups using Mann-Whitney U test. Results were evaluated with a 95% confidence interval and a significance level of p<0.05. Institutional Review Board approval and informed con-sents were obtained for all patients.

results

Twenty-four patients (14 men, 10 women) were included in Group A, and 30 patients (18 men, 12 women) were included in Group B. The right elbows of 16 patients and left elbows of 8 patients were affected in Group A, while the right elbows of 18 patients and left elbows of 12 patients were affected in Group B. NSAI adminis-tration was discontinued in all patients 2 weeks prior to beginning ESWT. Average symptom duration was 1.6 months in Group A and 8.4 months in Group B. Aver-age Aver-age of patients in Group A was 47 (range: 32–61) and 48 (range: 32–66) in Group B. Mild pain was ob-served at the application site in 50% of patients in both groups. Ice application was recommended for such pa-tients, and they did not require medication. Ecchymose, hematoma, or swelling was not observed in any patient.

When the pretherapy pain scores were compared with those obtained at Weeks 2, 12, and 24 postther-apy, no significant improvement was observed in pain while lifting chair, pain during working, and pain when pressed in Group A at Week 2 posttherapy, while these parameters were significantly improved at Weeks 12 and 24 posttherapy compared to the baseline. All other values in both Group A and Group B were significantly improved at Weeks 2, 12, and 24 posttherapy compared to the baseline values (Table 1). There was no difference in pre- and posttreatment scores regarding the domi-nant hand.

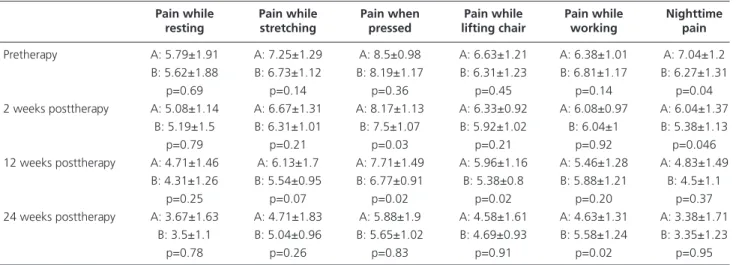

Baseline nighttime pain values were higher in LE cases comparing both baseline and posttherapy scores of chronic and acute LE cases (p=0.04). Similarly, it was found that the pain when pressed values were higher in acute LE cases at Weeks 2 (p=0.03) and 12 (p=0.02) posttherapy (Table 2, Figure 1).

Pain while lifting chair and pain pressed values were higher in acute LE cases compared to chronic cases at Week 12 posttherapy (p=0.02 in both), while pain while working values were higher in chronic cases at Week 24 posttherapy (p=0.02) (Table 2). Both groups benefited from the therapy equally when the efficiency of the ther-apy was considered in terms of values while pain while resting, pain while stretching, pain while nighttime. Discussion

We analyzed the results of ESWT therapy applied to cases of acute and chronic LE. Our results show that there is a significant clinical improvement in the pa-rameters of pain while resting, pain while stretching, pain when pressed, pain while working, and nighttime pain at Weeks 2, 12, and 24 posttherapy compared to the baseline values in chronic LE cases. It is also seen that all parameters decreased and a clinical improve-ment was achieved at Weeks 12 and 24 posttherapy in acute LE cases. It was observed that parameters such as pain while resting, pain while stretching, and nighttime pain decreased, a clinical improvement was achieved at Week 2 posttherapy compared to baseline values, and that pain when pressed, pain while lifting chair, and pain while working also decreased at Week 2 posttherapy compared to baseline values, although it was not statisti-cally significant. When the baseline values and values at Weeks 2, 12, and 24 posttherapy of acute and chronic table 2. Comparative statistical results of the groups.

Pain while Pain while Pain when Pain while Pain while nighttime

resting stretching pressed lifting chair working pain

Pretherapy A: 5.79±1.91 A: 7.25±1.29 A: 8.5±0.98 A: 6.63±1.21 A: 6.38±1.01 A: 7.04±1.2 B: 5.62±1.88 B: 6.73±1.12 B: 8.19±1.17 B: 6.31±1.23 B: 6.81±1.17 B: 6.27±1.31 p=0.69 p=0.14 p=0.36 p=0.45 p=0.14 p=0.04 2 weeks posttherapy A: 5.08±1.14 A: 6.67±1.31 A: 8.17±1.13 A: 6.33±0.92 A: 6.08±0.97 A: 6.04±1.37 B: 5.19±1.5 B: 6.31±1.01 B: 7.5±1.07 B: 5.92±1.02 B: 6.04±1 B: 5.38±1.13 p=0.79 p=0.21 p=0.03 p=0.21 p=0.92 p=0.046 12 weeks posttherapy A: 4.71±1.46 A: 6.13±1.7 A: 7.71±1.49 A: 5.96±1.16 A: 5.46±1.28 A: 4.83±1.49 B: 4.31±1.26 B: 5.54±0.95 B: 6.77±0.91 B: 5.38±0.8 B: 5.88±1.21 B: 4.5±1.1 p=0.25 p=0.07 p=0.02 p=0.02 p=0.20 p=0.37 24 weeks posttherapy A: 3.67±1.63 A: 4.71±1.83 A: 5.88±1.9 A: 4.58±1.61 A: 4.63±1.31 A: 3.38±1.71 B: 3.5±1.1 B: 5.04±0.96 B: 5.65±1.02 B: 4.69±0.93 B: 5.58±1.24 B: 3.35±1.23 p=0.78 p=0.26 p=0.83 p=0.91 p=0.02 p=0.95 A: Group A; B: Group B.

LE cases were compared, it was observed that nighttime pain was higher in acute LE cases. Efficiency of ESWT on pain when pressed was lower in acute cases than chronic cases at Weeks 2 and 12 posttherapy, and simi-larly, its efficiency on pain while lifting chair was lower in acute cases than chronic cases at Week 12 posttherapy. It was found that the effect of ESWT on pain while work-ing was lower in chronic cases at Week 24 posttherapy.

Prevalence of LE has been reported as 1–3% in vari-ous studies.[1] This problem is observed rarely in patients

<30 years and most commonly in patients in their 30s. The disease generally occurs on the dominant side, and the right side is affected twice as frequently as the left side. In our series, the dominant sides of 18 patients were affected in both groups.

Causes of LE are multifactorial. The natural course of LE is not clear, and there is not sufficient evidence in the literature that supports any definitive therapy method. In a randomized clinical study in which the patients were followed using a wait-and-see procedure by only limiting their activities, it was reported that equivalent outcomes with physical therapy and better outcomes than corticosteroid treatment were achieved in the elimination of the primary symptoms.[8] It has been

demonstrated that corticosteroid injection is effective in a short period of 2–6 weeks.[9] In a prospective

random-ized study that compared corticosteroid injection with ESWT application, it was found that corticosteroid injection was more effective in elimination of pain, but it was reported that longer follow-up periods were

re-quired for comparing efficiency in acute cases.[10] It was

reported that topical diclofenac administration was ef-fective in decreasing elbow pain.[11] It is recommended

that surgical therapy should be applied in patients who do not respond to conservative therapy but benefit from shock wave therapy.

In a randomized controlled study conducted in 198 patients by Bisset et al., they reported that the most ef-fective strategy was corticosteroid injection in order to achieve short-term outcomes; however, this application was less effective than physical therapy—including el-bow and wrist manipulations, frictions, stretches, exer-cises (isometric and isotonic) with a treatment of pulsed ultrasound, and acupuncture—due to recurrence of symptoms and its long-term outcomes.[5]

The mechanism of action of shock wave therapy is not clear. The operating logic of ESWT is to create an acute or new injury at lesion site over chronic condition, thereby triggering self-repair mechanisms of the body. As a result, vascularization and blood flow increase. It is suggested that hyperstimulation relieves pain by its anal-gesic effects.[5,12] Positive impacts of shock wave therapy

on improvement after injury of the Achilles tendon have been suggested.[13,14]

In a prospective randomized controlled study con-ducted by Chung and Wiley, they reported that there was no significant difference between the shock wave therapy group and the placebo group.[15] Chung and

Wiley applied shock wave therapy in patients with LE who were not treated previously (patients with

symp-Fig. 1. Comparison of acute and cronic LE pain scores. [Color figure can be viewed in the online issue, which is available at www.aott.org.tr]

Pain during rest Pain during stretching Pain when pressed Pain while lifting chair Pain during working Nighttime pain

5.79 5.62 5.08 5.19 4.71 4.31 3.67 7.25 6.73 6.67 6.31 6.13 8.19 8.17 7.71 6.77 5.88 5.65 6.63 6.31 6.33 5.92 5.96 5.38 4.58 4.69 6.38 6.81 6.08 6.04 5.46 5.88 4.63 5.58 7.04 6.27 6.04 5.38 4.83 3.38 3.35 4.5 5.54 4.71 5.04 8.5 7.5 3.5

Before therapy A Before therapy B 2 weeks after therapy A 2 weeks after therapy B 12 weeks after therapy A 12 weeks after therapy B 24 weeks after therapy A 24 weeks after therapy B

toms for <1 year and >3 weeks), but they were unable to show its efficiency with long-term outcomes.[15] In

another study with a similar patient group conducted by the same authors, it was found that ESWT was more effective in treatment of patients with symptoms for <16 weeks than in patients with symptoms >16 weeks.[16] In our study, average symptom duration was

1.6 months in Group A and 8.4 months in Group B. In a study conducted by Haake, the efficiency of shock wave therapy was not shown in treatment of LE.[17] Ko

reported that perfect and good outcomes were achieved in 57.9% of the patients at Week 12 posttherapy and 73.1% of the patients at Week 24 posttherapy in a study he conducted including 56 elbows with LE.[10] Rompe et

al. reported that low dose ESWT application decreased pain in chronic tennis elbow cases.[18] As an alternative

approach, Ozturan et al. compared outcomes of cortico-steroid, autologous blood injection, and ESWT appli-cation in treatment of chronic LE and reported that au-tologous blood injection and ESWT application were more effective.[19]

We did not find any existing study in the literature that compares ESWT application in acute and chron-ic LE. ESWT applchron-ication is becoming an increasingly common method in the treatment of chronic LE. We at-tempted to reveal the efficiency of ESWT application in the treatment of chronic LE by assessing the response of ESWT application in patients in the acute phase. Pro-cess is an early treatment method in acute LE; the body is aware of the problem but has not been desensitized, as in the case of chronic LE. Even though it appears that this contradicts the operating logic of ESWT, we believe that ESWT applied in the acute phase triggers improve-ment. Additionally, our study reveals that the concerns regarding the excessive increase of inflammation are not valid. No exacerbation or increase in the inflammation table was observed in the symptoms of any patient. On the contrary, patients who were treated with ESWT did not progress to chronic phase or suffer from long-term pain due to its analgesic efficacy.

With regard to the differences between the groups, the higher baseline nighttime pain in the acute group may be accounted for by the fact that the disease was in the acute phase. When the general pain scores are considered, pain increased in the early stages of ESWT treatment, though this increase was not significant. A higher pain while working in the chronic group at Week 24 posttherapy may be explained by the persistence of chronic symptoms.

There was no untreated control group in this study, and the number of patients was relatively low to assess

such a disputed therapy method, and these constitute the weaknesses of the study.

We suggest that ESWT is effective in the treatment of acute LE as it is in the treatment of chronic LE. In addition, the current data suggests that the progression from acute phase to chronic phase in cases of LE may be prevented by treatment with ESWT.

Conflics of Interest: No conflicts declared. references

1. Allander E. Prevalence, incidence, and remission rates of some common rheumatic diseases or syndromes. Scand J Rheumatol 1974;3:145–53.

2. Behrens SB, Deren ME, Matson AP, Bruce B, Green A. A review of modern management of lateral epicondylitis. Phys Sportsmed 2012;40:34–40.

3. Böddeker I, Haake M. Extracorporeal shockwave therapy in treatment of epicondylitis humeri radialis. A current overview. [Article in German] Orthopade 2000;29:463– 9. [Abstract]

4. Buchbinder R, Green SE, Youd JM, Assendelft WJ, Barn-sley L, Smidt N. Shock wave therapy for lateral elbow pain. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2005;4:CD003524. 5. Bisset L, Paungmali A, Vicenzino B, Beller E. A

system-atic review and meta-analysis of clinical trials on physical interventions for lateral epicondylalgia. Br J Sports Med 2005;39:411–22.

6. McCallum SD, Paoloni JA, Murrell GA. Five-year pro-spective comparison study of topical glyceryl trinitrate treatment of chronic lateral epicondylosis at the elbow. Br J Sports Med 2011;45:416–20.

7. Paoloni JA, Appleyard RC, Murrell GA. The Orthopaedic Research Institute-Tennis Elbow Testing System: A mod-ified chair pick-up test-interrater and intrarater reliability testing and validity for monitoring lateral epicondylosis. J Shoulder Elbow Surg 2004;13:72–7.

8. Smidt N, van der Windt DA, Assendelft WJ, Devillé WL, Korthals-de Bos IB, Bouter LM. Corticosteroid injections, physiotherapy, or a wait-and-see policy for lat-eral epicondylitis: a randomised controlled trial. Lancet 2002;359:657–62.

9. Struijs PA, Smidt N, Arola H, Dijk CN, Buchbinder R, Assendelft WJ. Orthotic devices for the treatment of tennis elbow. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2002;1:CD001821. 10. Crowther MA, Bannister GC, Huma H, Rooker GD. A

prospective, randomised study to compare extracorporeal shock-wave therapy and injection of steroid for the treat-ment of tennis elbow. J Bone Joint Surg Br 2002;84:678– 9.

11. Green S, Buchbinder R, Barnsley L, Hall S, White M, Smidt N, et al. Non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs

(NSAIDs) for treating lateral elbow pain in adults. Co-chrane Database Syst Rev 2002;2:CD003686.

12. Ko JY, Chen HS, Chen LM. Treatment of lateral epicon-dylitis of the elbow with shock waves. Clin Orthop Relat Res 2001;387:60–7.

13. Rasmussen S, Christensen M, Mathiesen I, Simonson O. Shockwave therapy for chronic Achilles tendinopathy: a double-blind, randomized clinical trial of efficacy. Acta Orthop 2008;79:249–56.

14. Furia JP. High-energy extracorporeal shock wave therapy as a treatment for insertional Achilles tendinopathy. Am J Sports Med 2006;34:733–40.

15. Chung B, Wiley JP. Effectiveness of extracorporeal shock wave therapy in the treatment of previously untreated lateral epicondylitis: a randomized controlled trial. Am J Sports Med 2004;32:1660–7.

16. Chung B, Wiley JP, Rose MS. Long-term effectiveness of extracorporeal shockwave therapy in the treatment of pre-viously untreated lateral epicondylitis. Clin J Sport Med 2005;15:305–12.

17. Haake M, König IR, Decker T, Riedel C, Buch M, Müller HH; Extracorporeal Shock Wave Therapy Clinical Trial Group. Extracorporeal shock wave therapy in the treat-ment of lateral epicondylitis : a randomized multicenter trial. J Bone Joint Surg Am 2002;84–A:1982–91. 18. Rompe JD, Hope C, Küllmer K, Heine J, Bürger R.

Anal-gesic effect of extracorporeal shock-wave therapy on chron-ic tennis elbow. J Bone Joint Surg Br 1996;78:233–7. 19. Ozturan KE, Yucel I, Cakici H, Guven M, Sungur I.

Au-tologous blood and corticosteroid injection and extracopo-real shock wave therapy in the treatment of lateral epicon-dylitis. Orthopedics 2010;33:84–91.

![Fig. 1. Comparison of acute and cronic LE pain scores. [Color figure can be viewed in the online issue, which is available at www.aott.org.tr]](https://thumb-eu.123doks.com/thumbv2/9libnet/5437555.104159/4.850.62.793.131.466/comparison-cronic-scores-color-figure-viewed-online-available.webp)