AT THE MARITIME FACULTY OF ISTANBUL TECHNICAL UNIVERSITY \

A THESIS PRESENTED BY 'a y s e AYDAN DENGIZ

TO

THE INSTITUTE OF ECONOMICS AND SOCIAL SCIENCES IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE

DEGREE OF MASTER OF ARTS

IN TEACHING OF ENGLISH AS A FOREIGN LANGUAGE

BILKENT UNIVERSITY SEPTEMBER, 1995

- A

IOC

Title: An analysis of the English language needs of the students at the Maritime Faculty of Istanbul Technical University.

Author: Ayse Aydan Dengiz

Thesis Chairperson: Dr. Phyllis Lim, Bilkent University, MA TEFL Program. Thesis Committee Members: Dr. Teri S. Haas,

Ms. Bena Gul Peker, Bilkent University, MA TEFL Program. This needs analysis study investigated the English language needs of the students at the Maritime Faculty of Istanbul Technical University where prospective deck

officers and marine engineers are educated to work both on cargo and passenger ships. The lack of a curriculum, the need to identify the objectives and means of the language

V

instruction, and the shortcomings of the current language program at the faculty necessitated a needs analysis study to meet the specific purposes of the maritime students.

The participants were 35 prep students, 77 junior students, 10 graduates, 7 language teachers, 8 content course teachers, 3 faculty administrators, and 3 employers from the maritime sector. Semi-structured questionnaires and interviews were used to gather data for this descriptive study.

The researcher sought an answer for a major question: What are the English language needs of the students at the Maritime Faculty both for their future careers and their studies? The sub-questions aimed at discovering the

marine engineers during their studies and professions; the language skills and sub-skills they will need in their work domain and faculties; the suitable teaching approach to be followed; and the shortcomings of the present English

language program.

The results obtained from the study revealed that maritime students should know English at an advanced or at least intermediate level.

The English language skills deck officers and marine engineers will need in their profession were determined as listening and speaking, whereas marine engineers will need reading most. Writing followed these skills for both

departments.

The following subskills were also considered as

important for seamen; writing reports, formal letters, and logbooks; reading instruction manuals, trade books, and professional journals; listening and responding to radio telephone messages, instructions, and participating in conversations with foreign colleagues.

The shortcomings of the current language program are reported to be inappropriate teaching methods, lack of coordination between teachers, inappropriate content of courses, underemphasis of oral/aural skills, and unsuitable regulations.

Purposes (ESP) approach with appropriate methodology should be followed in teaching English to maritime students and emphasized the urgency of the development of a curriculum that will meet the specific needs of the students at the Maritime Faculty as expressed in this study.

INSTITUTE OF ECONOMICS AND SOCIAL SCIENCES MA THESIS EXAMINATION RESULT FORM

AUGUST 31, 1995

The examining committee appointed by the

Institute of Economics and Social Sciences for the thesis examination of the MA TEFL student

Ayse Aydan Dengiz

has read the thesis of the student. The committee has decided that the thesis

of the student is satisfactory.

Thesis Title

Thesis Advisor

Committee Members

An analysis of the English language needs of the students at the Maritime Faculty of Istanbul Technical University Dr. Teri S. Haas

Bilkent University, MA TEFL Program

Dr. Phyllis L. Lim

Bilkent University, MA TEFL Program

Ms. Bena Gul Peker

Bilkent University, MA TEFL Program

We certify that we have read this thesis and that in our combined opinion it is fully adequate, in scope and in quality, as a thesis for the degree of Master of Arts.

Phyllis L. Lim (Committee Member)

Approved for the

Institute of Economics and Social Sciences

Ali Karaosmanoglu Director

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

I would like to express my special thanks to my thesis advisor, Dr. Teri S. Haas, for her helpful guidance, and continuous encouragement throughout my research study.

I am thankful to Dr. Phyllis L. Lim, Ms. Susan D. Bosher, and Ms. Bena Gul Peker, who provided me with invaluable feedback and recommendations.

I am deeply grateful to the Dean of the Maritime Faculty, Prof. Osman Kamil Sag, and to the former Head of the Basic Sciences Department, Assistant Prof. Nil Guler, who provided me with the opportunity to study at Bilkent University.

I wish to express my gratitude to the two Vice-deans of the Maritime Faculty, Prof. Ahmet Bayulken and Prof.

Süreyya Oney, and the maritime employers who contributed to this study with their participation in the interviews.

Special thanks go to the Maritime Faculty preparatory students, junior students, graduates, English language and content course teachers who participated in this study and provided me with invaluable data.

I am indebted to my dear colleague, Clodagh Mary

Green, who has been most supportive since the beginning of my teaching career and who encouraged me to attend the MA TEFL Program.

I am also grateful to my dear friend, Elif Uzel, without whose help and invaluable suggestions the

translation and the typing of the questionnaires could have never been completed.

Thanks go to all the MA TEFL students for their

cooperation, support, patience, and friendship throughout the program.

Finally, I must express my deep appreciation to my dear family, who have always been with me and supported me

LIST OF TABLES ... xiii

CHAPTER 1 INTRODUCTION ... 1

Background of the Study ... 1

Statement of the Problem ... 2

Purpose and Significance of the Study ... 6

Research Questions ... 7

Definition of Terms ... 8

CHAPTER 2 LITERATURE REVIEW ... 9

ESP and Needs Analysis ... 9

Definitions of Needs ... 12

Needs Analysis Methodology ... 15

Conclusion ... 17 CHAPTER 3 METHODOLOGY ... 18 Subjects ... 18 Instruments ... 21 ' Procedure ... 23 Data A n a l y s e s .... ... 25

CHAPTER 4 ANALYSIS AND INTERPRETATION OF D A T A ... 26

Introduction ... 26

The Method of Data Analysis ... 28

Results and Interpretations ... 29

Questionnaires ... 29

Tasks ... 29

Proficiency Level of English ... 31

English Language Skills ... 33

Writing ... 40

Reading ... 42

Listening ... 53

Speaking ... 56

Marine Terminology ... 60

Proficiency to Follow the English-based Content Courses .... 61

Suggestions ... 63

The English Language Instruction at the Faculty ... 64

Proficiency Level of English .. 66

English Language Teachers .... 66

Methodology ... 67

English Language Skills ... 67

Need for ESP Training for

English Language Teachers .... 69

Examinations ... 70

Instructional Materials ... 70

Facilities ... 70

More English After Prep ... 71

English-based Content Courses ... 71

Interviews ... 72

Importance of English ... 72

Purposes for Using English and Skills/Subskills Necessary in the Maritime Profession ... 73

Proficiency Level of English ... 75

More English After Prep ... 76

English-based Content Courses ... 77

Marine Terminology ... 77

Suggestions ... 78

CHAPTER 5 CONCLUSION ... 79

Overview of the Study ... 79

Results of the Analysis ... 80

Implications ... 84

Limitations of the Study ... 86

REFERENCES ... 87

APPENDICES ... 90

Appendix A: Informed Consent Form ... 90

Appendix B: Questionnaire for Language Teachers ... 91

Appendix C: Questionnaire for Junior Students ... 99

Appendix D: Questionnaire for Preparatory Students ... 106

Appendix E: Questionnaire for Graduates ... 113

Appendix F: Questionnaire for Turkish Content Course Teachers ... 120

Appendix G: Questionnaire for English-based Content Course Teachers ... 127

Appendix H: Interview Questions for the Dean/Vice-Deans of the Maritime F a c u l t y ... 137

Appendix I: Interview Questions for the Employers

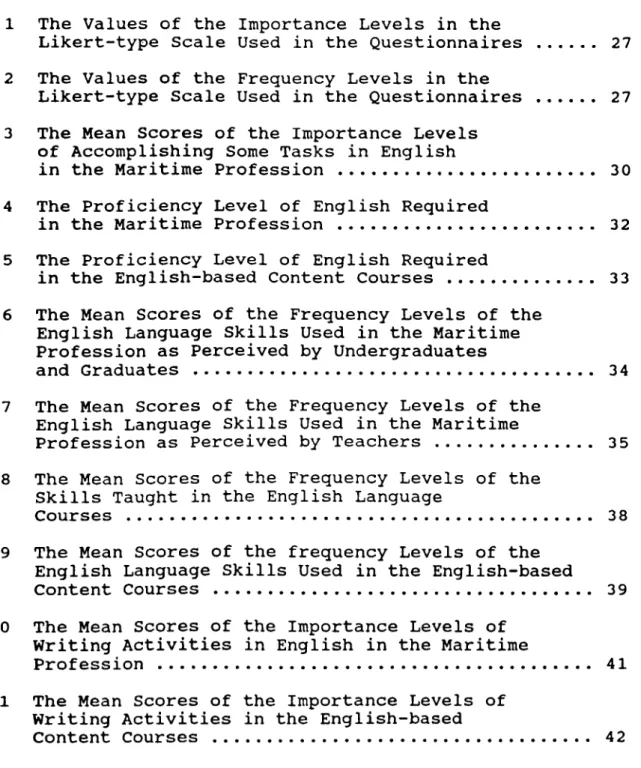

LIST OF TABLES

TABLE PAGE

The Values of the Importance Levels in the

Likert-type Scale Used in the Questionnaires ... 27 The Values of the Frequency Levels in the

Likert-type Scale Used in the Questionnaires ... 27 The Mean Scores of the Importance Levels

of Accomplishing Some Tasks in English

in the Maritime Profession ... 30 The Proficiency Level of English Required

in the Maritime Profession ... 32 The Proficiency Level of English Required

in the English-based Content Courses ... 33

8

10

11

The Mean Scores of the Frequency Levels of the English Language Skills Used in the Maritime Profession as Perceived by Undergraduates

and Graduates ... 34 The Mean Scores of the Frequency Levels of the

English Language Skills Used in the Maritime

Profession as Perceived by Teachers ... 35 The Mean Scores of the Frequency Levels of the

Skills Taught in the English Language

Courses ... 38 The Mean Scores of the frequency Levels of the

English Language Skills Used in the English-based Content Courses ... 39 The Mean Scores of the Importance Levels of

Writing Activities in English in the Maritime

Profession ... 41 The Mean Scores of the Importance Levels of

Writing Activities in the English-based

12 The Mean Scores of the Importance Levels of Reading Materials in English in the Maritime

Profession ... 43 13 The Mean Scores of the Importance Levels of

Reading Materials Used in the English-based

Content Courses ... 45 14 Difficulty in Reading and Understanding

Professional Materials in English ... 46 15 The Mean Scores of the Importance Levels of

Reasons for Difficulties in Reading and Understanding Professional Materials in

English ... 47 16 Methods for Coping with Difficulties in Reading

Professional Materials in English ... 48 17 The Mean Scores of the Importance Levels of

Reading Skills in English in the Maritime

Profession ... 49

V

18 The Mean Scores of the Importance Levels of Reading Skills in the English-based

Content Courses ... 51 19 The Mean Scores of the Importance Levels of

Reading Materials to Improve Reading Skills

in English ... 52 20 The Mean Scores of the Importance Levels of

Listening Activities in English in the Maritime

Profession ... 54 21 The Mean Scores of the Importance Levels of

Listening Activities in the English-based

Content Courses ... 55 22 The Proficiency Level of Speaking Skills

Required in the Maritime Profession ... 57 23 The Proficiency Level of Speaking Skills

Required in the English-based Content

Courses ... 59 24 Usefulness of Teaching Marine Terminology in

25 Belief in Students' Proficiency in English to Follow the English-based Content

Background of the Study

Beginning in the early 1960s, there were many reports from around the world of a growing dissatisfaction with the language teaching practices then current, in which all

learners were placed in the same language programs, and taught regardless of their aims, needs or interests (Mackay and Mountford, 1978; McDonough, 1984). In other words,

there were serious gaps between the language syllabi and the students* needs for the language.

Many of these students were learners for whom English was a tool in a job or profession. They were the students of different scientific areas such as medicine, economics, engineering and physics. During this period, the question of "special" language was much discussed and English for Specific Purposes (ESP)— the "utilitarian" purpose of

language, as Robinson (1980) called it— began to be current in order to cater for the special language needs of the learners. These learners were of a new generation who knew specifically why they were learning a language— businessmen who wanted to sell their products, mechanics who had to read instruction manuals, doctors who needed to keep up with

developments in their field and a whole range of students whose course of study included textbooks and journals only available in English (Hutchinson and Waters, 1987;

The general effect of this development was to put pressure on the language teaching profession to match the objectives of the language programs with the specific

language needs of the learners. As Hutchinson and Waters (1987) said, "English now became subject to the wishes, needs and demands of people other than language teachers"

(p.7). At this point, ESP's greatest contribution to

language teaching should be emphasized; it led to extensive needs analyses for curriculum design. Munby (1985), defines ESP courses as those in which the curriculum and materials are determined by the prior analysis of the English language needs of the learner. ESP learners want to learn English for particular purposes: reading technical books, writing business letters, and talking on the radio-telephone. In order to determine such specific language needs of

learners, a needs analysis is necessary. Statement of the Problem

The Maritime Faculty of Istanbul Technical University (ITU), where the researcher teaches, is the only institution in Turkey that trains deck officers and marine engineers to work both in cargo vessels and passenger ships cruising all over the world. Every year, a total of approximately 150 students (all male) enter this faculty, according to their university entrance exam results. Ninety of them are

engineering department due to their choices in the exam. Their profession will take them to many parts of the world, where English is considered as the "lingua franca."

Consequently, the need for English language instruction through an effective language program is indisputable.

When a student enters this faculty, he has two choices: the Turkish program or the English-supported program. If he chooses the former, he will do all his courses in Turkish in his department, with four hours of English instruction per week for four years. If a student chooses the latter, he must then take an English language proficiency exam which is prepared and given by the main English Language Department of ITU. About 20% of students, who have attended English- medium high schools have sufficient English to pass the

proficiency exam. The other students who fail this exam and wish to attend the preparatory (prep) class in learning

English can do so. In the prep class, these students are placed without taking their departments into account. They are taught grammar, reading, writing, listening, speaking and maritime terminology courses in mixed classes. At the end of one year, they take a test prepared by the English language teachers of the Maritime Faculty. Those who pass this exam enter their faculties and take 10% of their

studies. Those who fail the prep class do not repeat it, but transfer to the Turkish program and subsequently have four hours of English per week for four years.

Upon entering the prep class, every student takes a placement test. The results of these tests during the four year history of the prep class, have shown that, with a handful of exceptions, every student is either a total beginner or a false beginner. Therefore, as language teachers, we find it unrealistic for these students to achieve more than an intermediate level of English in one year. At the end of the year, the students who pass the prep class are of "good" intermediate standard, but students and teachers report that their English language level is not sufficient for the content courses given in English, such as Personnel Management. After having the information from the upper-class students that their level of English will not be enough for following the English-based content courses, and knowing that they will have no other English language

courses during their whole studies, most of the prep students do not see much merit in passing the prep class. For this reason, many students lose their motivation. This negative motivation naturally affects enthusiasm and

motivation of the prep teachers as well. Everybody seems to be dissatisfied, the students, the English language teachers

courses to the inadequately prepared students in the following four years.

The faculty follows the above regulations of the main English Language Department of ITU. However, since the location is far from the main campus, all coordination, materials and test preparation are done by a few language teachers who voluntarily take this responsibility. Also, the selection of books, the content of courses, and the type of exams are determined by the language teachers.

The English language program at the Maritime Faculty is not based upon a formal needs analysis and thus, a written curriculum defining the objectives and means of this program does not exist. Moreover, there are controversies among the language teachers whether General English or English for Specific Purposes (ESP) should be operationalized. Every academic year, different syllabi are put into practice and the debates about the objectives and means of the language program at the Maritime Faculty never come to an end.

To sum up, there is a dissatisfaction with the status quo both among the teachers and the students. Therefore, an

investigation into the language needs of the students at the Maritime Faculty must be carried out. This type of study is called a needs analysis, or needs assessment.

A needs assessment study has never been carried out at the ITU Maritime Faculty before. Yet, in order to design and teach effective courses, it is essential that the

researcher must investigate the uses to which the language will be put.

It is very important to develop a language program at the Maritime Faculty according to the learners' needs

because English is crucial for their studies and future careers. They could better learn and use English in a program designed according to their needs and specific

purposes. In addition, the administration and the maritime'' sector will indirectly benefit from this study; the

graduates of such a program, designed according to the specific needs of prospective workers of the profession, would be successful members of the maritime sector.

The purpose of this study was to find out the English language needs of the students at the Maritime Faculty through semi-structured questionnaires that were given to students, teachers, and graduates and semi-structured interviews with faculty administrators and employers from the maritime sector. It was hoped that after these needs were identified, they would be translated into linguistic and pedagogic terms in order to develop a new language

Research Questions

The main question to be asked in this study is: What are the English language needs of the students at the

Maritime Faculty? In order to answer this question, the following sub-questions need to be asked;

1. What level of English do the students at the Maritime Faculty need to know for their professions?

2. What level of English do the students at the Maritime Faculty need to know for their studies at the

faculty?

3. Which skills and sub-skills need to he in the curriculum to meet the students' language needs in their professions?

4. Which skills and sub-skills need to be in the

curriculum to meet students' language needs in their studies at the faculty?

5. Which is more suitable for the specific purposes of the students at the Maritime Faculty? General English or English for Specific Purposes?

6. What are the shortcomings of the current language program at the Maritime Faculty?

Needs assessment refers to a number of procedures for identifying general and specific language needs of learners and establishing priorities among them, so that appropriate goals, objectives, and content in courses can be developed

(Hutchinson & Waters, 1987).

"ESP courses are those in which the aims and the

content are determined not by criteria of general education, but by functional and practical English language

The main purpose of this chapter is to present an overview of the literature on ESP and needs analysis.

First, the origins of ESP and the role of needs analysis in developing ESP courses will be discussed. Then, different definitions of needs will be given. Following that,

definitions of needs analysis and its methodology will be included. Finally, a conclusion with the goals and

methodology of this study will be provided. ESP and Needs Analysis

With the rise of technology, science, and commerce after the Second World War, a need for an international language for communication generated. English as the

"lingua franca" grew out of this need and a new generation was created who knew why they needed to learn English

(Hutchinson and Waters 1987; McDonough, 1984), in other

words, learners who were aware of their specific purposes in learning English. This consciousness led to the demand for English language courses that matched the special purposes for which many learners needed foreign languages in the real world.

According to Kennedy and Bolitho (1984), ESP is taught when learners will need English as part of their

professions. In other words, ESP learners who have

of needs in terms of language skills and functions which are required in their professions. Hutchinson and Waters (1987) note that the English language skills needed by a particular group of learners can be identified by analyzing the

linguistic characteristics of their specialist area of work or study. "Tell me what you need English for and I will tell you the English that you need” became the guiding principle of ESP (Hutchinson and Waters, 1987, p. 50).

Hutchinson and Waters (1987) believe that the

foundation of ESP relies on one simple question: Why do these learners need to learn English? They identify the need on the part of the learner to learn a language. In ESP course design, all decisions as to content and method are based on the learner's reason for learning English. The authors claim several differences between ESP and General English. According to Hutchinson and Waters (1987), what distinguishes ESP from General English is "not the existence of a need, but rather an awareness of the need" (p.53).

Hutchinson and Waters continue; "If learners and teachers know why the learner needs English, that awareness of a target situation will have an influence on what will be acceptable as reasonable content in the language course"

(p.53). Thus, content of any ESP course should depend on learner need— a definable need to communicate in English that distinguishes the ESP learner from the learner of

General English.

Hutchinson and Waters (1987) also comment that the development of English courses in which relevance to the learners' needs and interests is pre-eminent will improve the learners' motivation and, thereby, make learning better and faster.

Wilkins believes that "it is necessary to predict what kinds of language skills will be of greatest value to the learner" (1974, p. 58). This furthers the idea that an analysis of learner needs and expectations will be a

prerequisite to program development in any language-teaching situation, whether for "general" or for "specific" purposes

(Shutz & Derwing, 1981).

Robinson defines ESP as "goal directed" (1991). That is, students study English not because they are interested in the English language or its culture, but because they need English for study or work purposes. This goal-

consciousness in learning English led course designers to collect information on learners' language needs in order to draw up "a profile to establish coherent objectives, and take subsequent decisions on course content, language

skills, and vocabulary required for the situation in which learners will use English" (McDonough, 1984, p. 23).

Mackay and Mountford (1978) and Robinson (1991),

language courses must be specified, through an analysis of the activities the learners will be performing in the

foreign language they are learning. That is why the needs assessment procedure in ESP has great importance and is regarded as the first step to be taken in ESP course design.

Definitions of Needs

Before deciding on a procedure to analyze the language needs of the learners, the researcher should first define what is meant by "needs.” A number of people (Berwick,

1989; Brindley, 1989; Mackay and Mountford, 1978; Widdowson, 1981) have discussed the different interpretations of needs. First, needs can refer to learners' study or job

requirements, that is, what they should be able to do at the end of their language course. This is a goal-oriented

definition of needs, according to Widdowson (1981). Berwick (1989) describes needs in this sense as objectives. Second, needs can be defined as "what the user-institution or

society at large regards as necessary or desirable to be learned from a program of language instruction" (Mackay and Mountford, 1978, p. 27). Third, needs can refer to what the learner must do to actually acquire the language. This is a process-oriented definition of needs and refers to the means of learning (Widdowson, 1981).

Some of the views of needs have been paired, and the members of each pair seen as polar opposites. For example.

researchers contrast the views of learners and of teachers on the goals and content of the ESP course (Brindley, 1989). This type of needs analysis was conducted by the Research and Development Unit (English Language) of the National

Autonomous University of Mexico prior to designing a special purpose English Language course for undergraduates in the Faculty of Veterinary Medicine (Mackay, 1978). The needs analysis committee administered two sets of structured interviews— one to the teaching staff and the other to the undergraduates whom they taught. In this way, the committee were able to identify the discrepancies between the needs as stated by the professors and those as stated by the student body.

Another contrasted view of needs includes perceived versus felt needs, which can also be referred as objective and subjective needs respectively. According to Berwick

(1989) felt needs (sometimes referred to as expressed needs) are those which learners have, whereas perceived needs

"represent the other side of the coin: they are the

judgements of certified experts about the educational gaps in other people's experience" (p. 57).

In determining learners* language needs, Mackay and Mountford (1978), mention that care has to be taken to

distinguish real, current needs (what the students need the language for now), from future, hypothetical needs (what the

student may want the language for at some unspecified time in the future). "Both of these should be distinguished from student desires (what the student would like to be able to do with the language, independent of the specific

requirements of the situation or job for which the needs analysis is being carried out) and the teacher-created needs

(what the teacher imagines is needed or would like to impose on the students)" (Mackay and Mountford, 1978, p. 29).

Hutchinson and Waters (1987), parallel to Widdowson's differentiation of needs as process-oriented versus goal- oriented, make a distinction between target needs (i.e. what the learner needs to do in the target situation) artd

learning needs (i.e what the learner needs to do in order to learn). Target needs includes such concepts as necessities. lacks, and wants. The term necessities refers to some

specific features of language which the learner will need in order to operate efficiently in the target situation,

whereas the term lacks refers to what learners still need to know based on an assessment of what they already know. In this sense, lacks is the gap between learners' existing proficiency in a subject area and their target proficiency. Finally, wants refers to learners' views as to what their needs are (Hutchinson and Waters, 1987) .

Needs Analysis Methodology

Needs analysis, or needs assessment, is defined by

Pratt (1984), as "an array of procedures for identifying and validating needs and establishing priorities among them”

(cited in Richards, 1984, p. 5).

According to Smith (1990), "Needs assessment is a process for identifying the gaps between the educational goals schools have established for students and students' actual performance” (p. 6).

As has already been mentioned, ESP students learn

English in order to acquire a set of professional skills and to perform particular job-related fun'ctions. Therefore, ESP practitioners begin with a basic question: What does the language learner need to know in order to function in the target situation? It has become a common practice to carry out some form of needs analysis where the students' future use of English is identified in order to answer this

question.

Holliday and Cooke (1983) suggest that answers for needs assessment must be found from four different

perspectives:

1. What the subject teacher thinks the learner needs to know (subject teacher perceived needs),

2. What the institution thinks the learner needs to know (institution perceived needs),

3. What the English language teacher thinks the learner needs to know (ESP teacher perceived needs) ,

4. What the learners think they need to know (learner perceived needs) ,

5. What the learner wants to know,

6. What is compatible with specific local features of the environment (means) (p. 66).

The work of Richterich and Chancerel (1980), which is a useful guide for the practitioners of needs assessment,

organizes data collection into three major information categories: identification by the learner of his needs, identification of the learner's needs by the teaching

establishment, and identification of the learner's needs by the user-institution (i.e. learner's employer). This would be a full-scale assessment of language needs.

Richterich and Chancerel (1980) also point out that needs analyses can contribute information during the language course as well as for course planning. These formative effects of needs analysis thus overlap with the formative influence of evaluation since both needs analysis and evaluation are concerned with informing decision-making about the aims, objectives, content and methods of an

existing learning program. Therefore, needs analysis can be an on-going process which will help both learners and

can be modified, and in doing so forms an important aspect of education.

Conclusion

This needs analysis study attempted to both identify the students' real needs and future (target) needs, and to provide feedback about the shortcomings of the English language program at the Maritime Faculty of Istanbul

Technical University. In order to do this, the researcher conducted a needs analysis. The language needs of the

students were identified by administering questionnaires to students and graduates (identification by the learner of his needs) by giving questionnaires to language teachers and content course teachers and interviewing the faculty

administrators (identification of the learner needs by the teaching establishment) and by interviewing the employers from the maritime sector (identification of the learner needs by the user-institution). The researcher also aimed to elicit criticisms and recommendations from these subjects about the current language program at the faculty. Based on the information gathered from the subjects, the researcher made suggestions about ways to meet the specific needs of the students. The researcher hopes that these suggestions will lead the academic administrators to take necessary steps to develop a curriculum according to the language needs of the students at the Maritime Faculty.

CHAPTER 3 METHODOLOGY

In this study, a needs assessment procedure was

followed in order to identify the English language needs of the students at the Maritime Faculty of Istanbul Technical University. It was a descriptive study using survey

methodology. Data were collected through similar

questionnaires that were administered to junior students, prep students, graduates, language teachers, and content course teachers, and through interviews with the faculty administrators and employers from the maritime sector.

Subjects

The subjects were: 35 pre-facultv prep students who had positive expectations about the English language

instruction at the faculty; 77 junior students who were more conscious about their language needs; 10 graduates who had experienced the specific language requirements of their professions; 7 English language teachers who had some controversial ideas about the approach to be implemented into the English language instruction at the faculty; 8

content course teachers who had some ideas and demands about the English language instruction at the faculty; 3 faculty administrators whose points of view about the English

language policy at the faculty were considered important; and 3 employers from the maritime sector who would employ the graduates eventually.

One hundred and twelve students participated in this study: 35 prep students who were selected randomly among

a

total number of 99 and 77 junior students— 49 from theEnglish-supported Program and 28 from the Turkish Program— out of a total number of 87. The researcher had aimed to give questionnaires to all of the junior students since they formed a heterogeneous community representing different

language programs and thus different perspectives. However, it was impossible to reach all of the juniors since some of them did not want to participate in the study and some of them were not at school during the data collection week.

This resulted a 88.6% response rate. Freshman and sophomore students were eliminated in this study because the

researcher believed that their views about their language needs would not differ substantially from the prep students and junior students respectively. Also the senior students did not take part in the study, since they were doing their sea training during the period of data collection.

Ten graduates of the faculty who were on land during this period also filled out questionnaires for the study. Six of them were deck officers and four of them were marine engineers. It should be emphasized that all graduates who participated in this study were students in the Turkish Program before the development of the English-supported Program, and took only four hours of English per week during

their course of studies.

Among the English language teachers were five prep teachers and two other language teachers, who had been teaching English in the Turkish program at the faculty for more than 20 years. Two other prep teachers participated in the piloting and the other remaining two did not want to participate in the study.

Eight content course teachers among a total of about 40 participated in the study to represent all the departments of the faculty; two from the deck department, one from the engineering department, and five teachers who taught

students from both departments (three of these teachers taught only in the Turkish program, one taught only in the English-supported program, and four of these teachers taught in both programs).

Representing the faculty administrators, the dean and the two vice-deans participated in this study. Three

employers from the maritime sector were also included in this needs analysis: one administrator from the State Shipping Company (SSC), one administrator from a private shipping company (PSC) and one administrator from a foreign shipping company (FSC).

Instruments

The information from the students, the teachers, and the graduates about their language needs were elicited by means of questionnaires. a suitable data gathering

instrument for large numbers of subjects. The

questionnaires were modified versions of the questionnaires used in previous needs analysis studies (Elkilic, 1994; Ustunluoglu, 1994) . They followed a semi-structured format with closed items based on two kinds of 5-point Likert-type scales, and with one multiple choice and three yes/no

questions, and one open-ended item which allowed subjects to go into more detail or to express different views on thfe questions asked. There was also a space after some closed items to allow respondents to specify ideas that had not been covered in the options.

In addition, an informed consent form (see Appendix A) was given to the subjects to sign in order to remind them that it was their own choice to participate in the study and to assure them that the answers would remain anonymous.

All of the questionnaires administered to all subject groups consisted of nine common closed items about the target needs of the students at the Maritime Faculty, and some additional items specific to some of the groups. One open-ended item at the end was also administered to all subject groups. The common items were about the purposes of

the students for using English in their professions, the level of English they needed, and the skills and subskills they would need in their jobs. The open-ended item sought for suggestions for the improvement of the current language program at the faculty.

A fourteen-item questionnaire was administered to both English language teachers and junior students (see Appendix B and Appendix C ) . The items in these questionnaires were the same except for minor wording changes. The

questionnaire administered to the preparatory students (see Appendix D) consisted of 13 items, whereas there were 12 items in the questionnaire for the graduates (see Appendix E) . Except for one item and some minor wording changes, these questionnaires were also the same.

Content course teachers completed different

questionnaires, according to whether they taught in the Turkish Program or in the English-supported Program.

Turkish content course teachers were asked questions about the target needs of the students (see Appendix F). English- based content course teachers who taught in the English- supported Program were asked six additional items about the English language needs of those students who were then

enrolled in the English-based content courses (see Appendix G) .

the maritime sector, interviews were used as the data

gathering instrument. The interviews were guided by semi- structured questions which were thematically similar to those in the questionnaires (see Appendix H and Appendix I). The interviewer also allowed time for one open-ended

question at the end, so that respondents could freely offer their own suggestions about the English language instruction at the Maritime Faculty.

Procedure

The questionnaires were first prepared in English and then translated into Turkish since the subjects' level of English— except for the language teachers— might not be adequate to comprehend the questions. Then a back- translation was provided by a colleague to help ensure validity and reliability of the questionnaires.

The researcher had been given official permission by the faculty administrators to carry out the study, and received some help from the faculty members and the

graduates in contacting the necessary people for the study. The questionnaires were piloted by the researcher on March 23 and 24, with a small subsample of the population to provide a clear idea of the variety and range of answers that might be expected for any question and to clarify

misunderstandings or ambiguities of wording. The subsample for the piloting consisted of 10 junior students, four prep

students, two graduates, two language teachers, and four content course teachers. The subjects in the piloting were asked to complete a pilot questionnaire evaluation checklist in order to give feedback to the researcher on the clarity of the questions and instructions in the questionnaires. The subjects in the pilot were also asked to specify issues that had not been covered in the questions and which they believed should be incorporated in the questionnaires. In order to improve validity and reliability, the researcher revised the questionnaires according to the helpful

suggestions in the evaluation checklists.

The revised questionnaires and the interviews were administered between the dates of April 10 and 14. The researcher went to the faculty, explained to students and teachers the purpose of the questionnaires, and distributed and collected the questionnaires in person. This prevented misunderstood questions. Similarly, the researcher

personally administered questionnaires to the graduates who were not on board ship in order to increase the number of returns. English language teachers and content course teachers were also asked to complete questionnaires administered by the researcher. Students filled out questionnaires in the classroom environment, whereas teachers and graduates were asked to fill out the

asked to write their departments on the questionnaire sheet and also to state which program they were in at the Maritime Faculty.

Interviews with the faculty administrators and

employers from the maritime sector were also conducted in an office environment. The researcher both took notes and

recorded the interviews.

Data Analyses

The Likert-type scale responses of the subjects for each item in the questionnaires were reported in means. Other type of questions, like yes/no and multiple-choice questions were analyzed by frequencies and percentages. The responses elicited from different groups of the population about the language needs of the students at the faculty, and the percentages, frequencies, and the mean scores of these responses were compared in tables. Answers to open-ended questions were analyzed by putting them into categories

according to recurring themes. Interview answers by faculty administrators and employers from the maritime sector were also categorized and compared.

CHAPTER 4 ANALYSIS AND INTERPRETATION OF DATA Introduction

This needs analysis study aimed at investigating the English language needs of the students at the Maritime Faculty of Istanbul Technical University. The data came from two main sources: semi-structured questionnaires administered to 35 prep students, 77 junior students, 10 graduates, seven language teachers, and eight content course teachers, and semi-structured interviews with three faculty administrators and three maritime employers.

All of the questionnaires administered to all subject groups consisted of nine common closed items about the target needs of the students at the Maritime Faculty and some additional items about their study needs specific to some of the groups. One open-ended item at the end was also administered to all subject groups. The common items were about the purposes of the students for using English in

their professions, the level of English they needed, and the skills and subskills they would need in their jobs. The open-ended item sought for suggestions for the improvement of the current language program at the faculty.

In the questionnaires, two kinds of Likert-type scales were used: the responses in one varied from not important

(1) , to extremely important (5); and in the other from never (1), to always (5) (see Tables 1 and 2).

The Values of the Importance Levels in the Likert-tvpe Scale Used in the Questionnaires

Table 1

Importance Level Value

Not at all important 1

Not too important 2

Fairly important 3

Very important 4

Extremely important 5

Table 2

The Values of the Freauencv Levels in the Likert-tvoe Scale Used in the Questionnaires

Frequency Level Value

Never 1

Rarely 2

Sometimes 3

Usually 4

Always 5

A few yes/no, and multiple-choice questions were also included in the questionnaires.

Semi-structured interviews were administered to faculty administrators and maritime employers. The

questionnaires. The interviewer also allowed time for one open-ended question at the end to ensure that all issues important to these two groups were discussed.

The Method of Data Analysis

The Likert-type scale responses of the subjects for each item in the questionnaires were reported in means. For mean score values, the cut-off point for the decimals were decided accordingly: Up until .50, the value was considered the whole number preceding it. With .51, the value was considered the whole number following it. Other types of questions, such as yes/no and multiple-choice questions were analyzed by frequencies and percentages. However, since the percentages with decimals were rounded up, the total of all scores may not add up to exactly 100%. The responses elicited from different subject groups about the language needs of the students at the faculty were tabulated and compared by presenting percentages, mean scores, and frequencies. Since the item number in each questionnaire is not the same, the researcher categorized them under common headings. Answers to open-ended item in the questionnaires were analyzed by putting them into

categories. Interview answers were also categorized and compared.

Results and Interpretations Questionnaires

Tasks

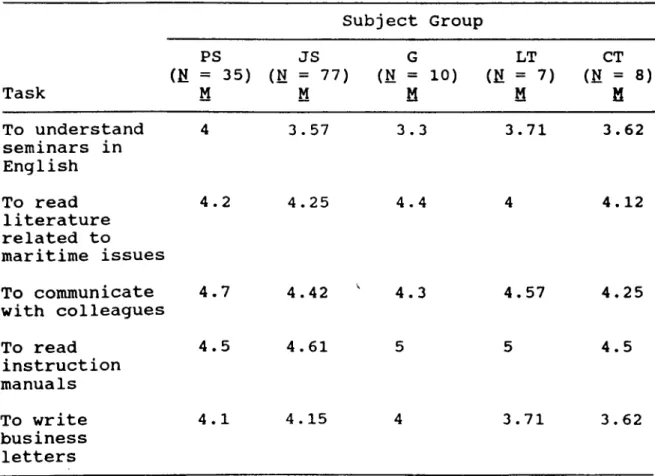

The first item asked all subjects to evaluate the

importance of accomplishing certain tasks in English in the maritime profession. The mean scores of the importance

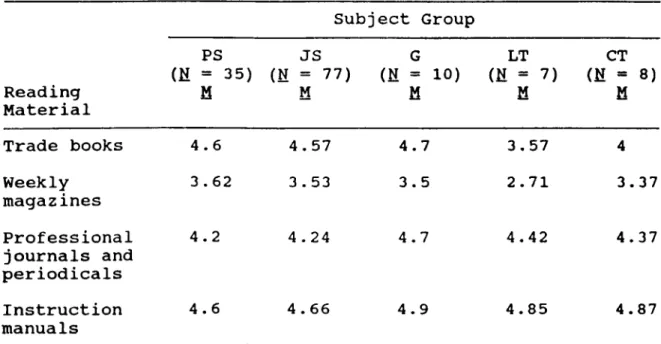

levels (see Table 3) demonstrate that all subjects except for prep students rated "to read instruction manuals" as the most important task.

The Mean Scores of the Importance Levels of Accomplishing Some Tasks in English in the Maritime Profession

Table 3 Subject Group PS JS LT CT (N = 35) (N = 77) (N = 10) (H = 7) (H = 8) Task M M M M M To understand seminars in English 4 3.57 3.3 3.71 3.62 To read literature related to maritime issues 4.2 4.25 4.4 4 4.12 To communicate with colleagues 4.7 4.42 4.3 4.57 4.25 To read instruction manuals 4.5 4.61 5 5 4.5 To write business letters 4.1 4.15 4 3.71 3.62

Note. PS = Prep Students ; JS = Junior Students; G = Graduates; LT

Teachers.

' = Language Teachers; CT = Content Course

According to the table, "to write business letters" and "to understand seminars in English” seemed to be the least in importance to most of the groups. However, nearly all subject groups still rated these tasks as very important. Graduates and undergraduates believed that "to write

groups also considered "to understand literature related to maritime issues" to be a very important task for seamen. Prep students and language teachers perceived "to

communicate with colleagues" as an extremely important task in the profession, whereas other subject groups rated it as very important.

In the blank space that allowed subjects to present any ideas that were not in the options, 10 junior students, one language teacher, and one content course teacher

specified that communicating with people from different cultures in ports was another important task a seaman. A few students also Mentioned, "to be able to follow recent developments; to be able to understand articles and research in foreign media; and to do research in the maritime

profession" as other English language tasks a seaman should accomplish.

Proficiency Level of English

The next item asked subjects to indicate the level of English required in order to be successful in the maritime profession. The results (see Table 4) show that an advanced level of English is needed, according to all groups who

participated in the study. As seen in Table 4, nearly all graduates (90%) responded that seamen should know English at an advanced level.

The Proficiency Level of English Required in the Maritime Profession Table 4 Proficiency Level Subject Group

Native-speaker- Advanced Intermediate Beginning like t

%

£

%

!

%

£

%

PS (N = 35) 10 29 24 69 1 3 — JS (N = 77) 17 22 54 71 6 8 — G (N =' 10) — — 9 90 1 10 — LT (N = 7) 1 14 5 71 1 14 — CT (N = 8) — — 7 88 1 13 —Note. PS = Prep Students ; JS = Junior Students;

G = Graduates; LT = Language Teachers; CT = Content Course Teachers.

Over 93% of all students, 71% of language teachers, and 88% of content course teachers agreed that either an advanced level or native-speaker-like level was necessary, whereas only approximately 6% of all students and one language teacher and one content course teacher suggested that an intermediate level was required. No one among all

participants checked the beginning level.

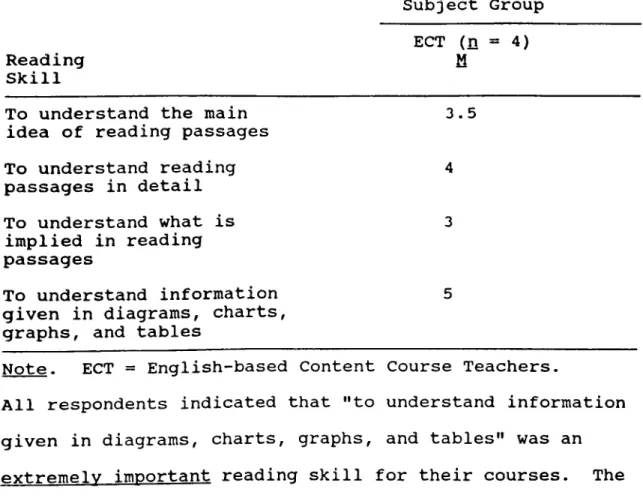

teachers to estimate the proficiency level of English required in their courses (see Table 5).

Table 5

based Content Courses

Proficiency Level Native-speaker- Advanced like Intermediate Beginning Subject Group f i f 1 £ i f i ECT (n = 4) 2 50 1 25 1 25

Note. ECT: English-based Content Course Teachers.

Teachers showed contrast in their responses. One teacher among four believed that the beginning level was enough, another checked the intermediate level, whereas two teachers

(50%) thought that students should know English at an advanced level.

English Language Skills

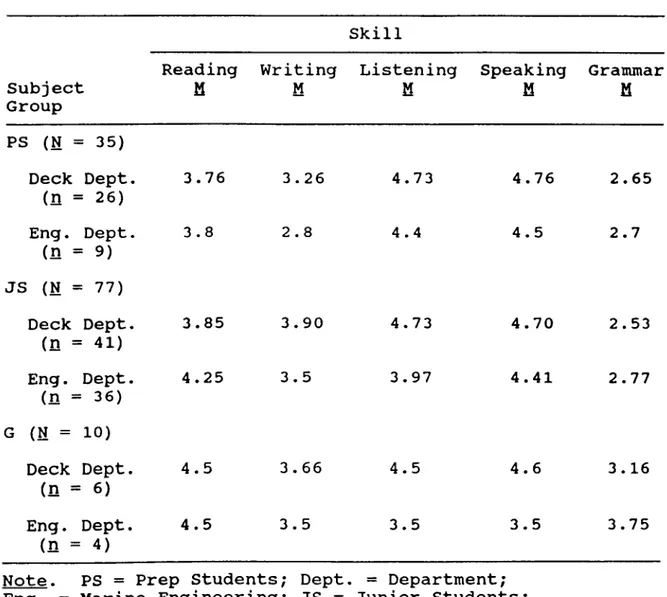

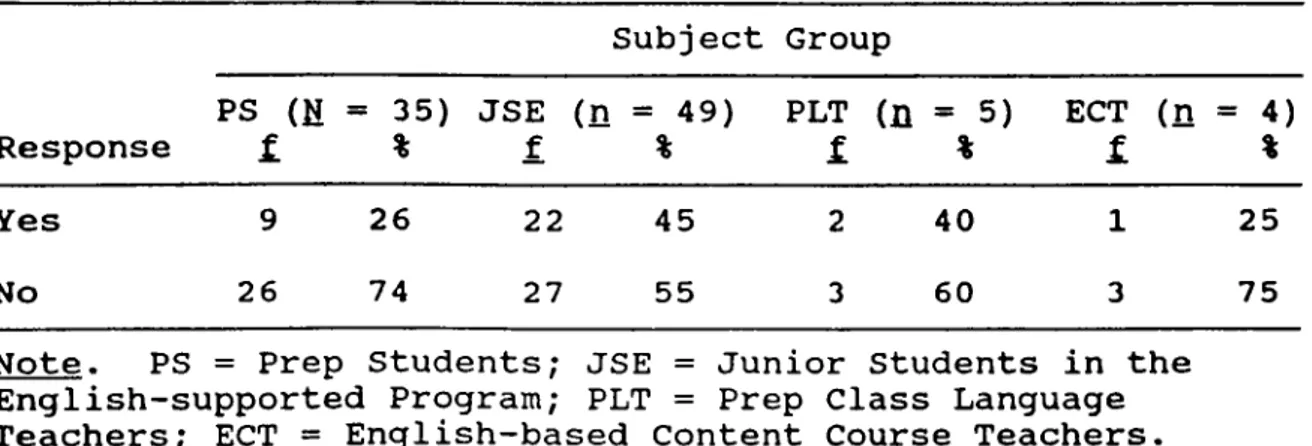

The next item asked all subjects to identify the frequency of the English language skills used in the maritime profession. Table 6 illustrates the means of frequency levels rated by undergraduates and graduates and Table 7 by teachers.

The Mean Scores of the Frequency Levels of the English

Language Skills Used in the Maritime Profession as Perceived bv Undergraduates and Graduates

Table 6 Skill Subject Group Reading H Writing M Listening M Speaking H Grammar n PS (N = 35) Deck Dept. (n = 26) 3.76 3.26 4.73 4.76 2.65 Eng. Dept· (n = 9) JS (N = 77) 3.8 2.8 4.4 4.5 2.7 Deck Dept, (n = 41) 3.85 3.90 4.73 4.70 2.53 Eng. Dept, (n = 36) G (N = 10) 4.25 3.5 3.97 4.41 2.77 Deck Dept. (n = 6) 4.5 3.66 4.5 4.6 3.16 Eng. Dept. (n = 4) 4.5 3.5 3.5 3.5 3.75

Note. PS = Prep Students; Dept. = Department; Eng. = Marine Engineering; JS = Junior Students; G = Graduates.

The mean scores (see Table 6 and 7) show that undergraduates and teachers highly agreed on speaking and listening as the most frequently used skills by prospective deck officers.

The Mean Scores of the Frequency Levels of the English Table 7 by Teachers Subject Group Skill Reading M Writing M Listening M Speaking M Grammar n LT (N = 7) Deck Dept. 3.71 3.57 4.57 4.71 2.57 Eng. Dept. 4.57 3.14 4.14 4.14 3 CT (N = 8) Deck Dept. 3.5 3.87 4.5 4.75 2.5 Eng. Dept. 4.12 3.25 3.87 3.87 2.37

Note. LT = Language Teachers; Dept. = Department; Eng. = Marine Engineering; CT = Content Course Teachers.

More than 95% of all undergraduates from the deck department and 100% of all teachers maintained that speaking and

listening were usually or always used by deck officers in their profession.

As seen in Table 6, differing from other subject

groups, graduates from the deck department rated reading as the most frequently used skill, together with speaking and listening (with the mean scores of 4.5, 4.5, and 4.6

respectiyely) . Experienced deck officers appeared to regard reading comparable in importance to oral/aural skills.

probably in terms of expanding their professional knowledge. Grammar was rated as the least frequently needed skill in the deck department by all subject groups. However, the mean score of the frequency level for grammar as perceived by graduates is 3.16, which is higher than other groups' scores. This means that graduates found grammar as a fairly important skill for their professions, probably due to the fact that accuracy plays an important role in the maritime profession.

The mean scores also indicate that, with the exception of undergraduates, all subject groups considered reading to be the most frequently used skill by marine engineers in their profession. One hundred percent of the graduates from the marine engineering department checked that reading was usually or always used in their profession. Similarly, six among seven language teachers (over 85%) responded that reading was always used by marine engineers.

The answers giyen by undergraduates are different in that more than 86% of juniors from the marine engineering department belieyed speaking was the most frequently used skill; they rated speaking as usually or always used in their profession. Speaking was followed by reading according to oyer 80% of the juniors from the marine

engineering department. Preps from the marine engineering department rated both speaking and listening as the most

frequently used skills.

The mean scores also demonstrate that writing, listening, and speaking are important skills for marine engineers, but a close look at Table 6 suggests that graduates rated grammar as more frequently used than

writing, speaking, and listening. This might be due to the necessity to understand the complicated grammar used in the instruction manuals which marine engineers frequently refer to. All other subjects rated grammar as the least

frequently used skill in the maritime profession, but most of the subjects agreed that grammar was more frequently needed by marine engineers than by dec'k officers.

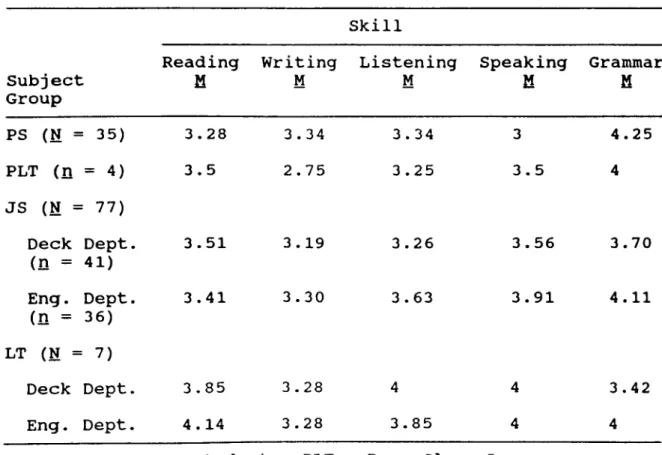

The next item investigated how often each of the

English language skills were taught in the English language courses, as perceived by teachers and undergraduates. Over 88% of prep students who participated in the study state that grammar, the least frequently needed skill in the work domain is the most frequently taught in the classroom. This finding was confirmed by 75% of language teachers who taught prep students at the faculty. According to the mean scores in Table 8, prep students also believed that speaking was the least frequently taught skill, whereas prep class teachers reported that they taught writing the least frequently.

The Mean Scores of the Frequency Levels of the Skills Taught in the English Language Courses

Table 8 Skill Subject Group Reading H Writing M Listening M Speaking M Grammar PS (N = 35) 3.28 3.34 3.34 3 4.25 PLT (n = 4) 3.5 2.75 3.25 3.5 4 JS (N = 77) Deck Dept. 3.51 3.19 3.26 3.56 3.70 (n = 41) Eng. Dept. 3.41 3.30 3.63 3.91 4.11 (n = 36) LT (N = 7) Deck Dept. 3.85 3.28 4 4 3.42 Eng. Dept. 4.14 3.28 3.85 4 4

Note. PS = Prep Students; PLT = Prep Class Language Teachers; JS = Junior Students; Dept. = Department; Eng. = Marine Engineering; LT = Language Teachers. The deck department junior students also believed that grammar was usually taught in the language classroom, whereas language teachers claimed that listening and speaking were the most frequently taught skills.

Both prep students and language teachers agreed that writing was sometimes taught in the English language