THE CHANGING ROLE OE THE IME

A T HESI S

SUBMI T T ED TO THE DEP A R T ME N T OF MANAGEMENT AND THE I N S T I T U T E OF MANAGE- MENT S C I EN C ES

OF B I L K E N T U N I V E R S I T Y

IN P A R T I A L F U L F I L L M E N T OF THE REQUI REMENT S FOR THE DEGREE OF

MAST ER OF BUS I NESS A D MI N I S T R A T I O N

by M.Emin Kasapgil January 1989 V ¿ α S 2 ІJ

Íil-taiiiinAaA

tarafndua V.:;"' '

i;iv.

I c e rtify that I have read this thesis and in my opinion it is fully adequate, in scope and in quality, as a thesis fo r the degree of the Master o f Business Administration.

I c e rtify that I have read this thesis and in my opinion it is fu lly adequate, in scope and in quality, as a thesis fo r the degree o f the Master o f Business Administration.

Assist. Prof. Erol Çakmak

I c e rtify that I have read this, thesis and in my opinion it is fu lly adequate, iri scope and in quality, as a thesis fo r the degree o f the Master o f Business Administration.

Assist. Prof. Kürşat Aydogan

Approved fo r the Institute o f Management Sciences.

ABSTRACT

THE CHANGING ROLE OF THE IMF

M.Emin KASAPGİL

M.B.A. Thesis, Institute o f Management Sciences Supervisor: Assist. Prof. Gökhan Çapoğlu

January 1989, 61 pages.

In this study, requirements o f the international monetary system and evolution o f the IMF's role in the system are studied. The IMF's role changed over the past years by force o f circumstances, moved towards long term lending, and recently involved in the negotiations o f debt reschedulings with creditor banks. For this, it is criticised to have broken away from the principles o f the Bretton Woods conference where it was conceived. Recently, the IMF's role and functions become controversial· p articu larly by hdgh-debt developing countries.

Keywords : international monetary system, IMF policies, external debt problem, and reschedulings.

ÖZET

IMF'NİN DEĞİŞEN POLİTİKALARI

M. EMİN KASAPGİL

Yüksek Lisans Tezi işletme Bilirrjler Enstitüsü Tez Yöneticisi: Y. Doç. Dr. Gökhan Çapoglu

Ocak. 1989, 61 Sayfa

Bu çalrşma u lu s la ra ra s ı para sisteminin özelliklerini ve IMF'nin bu sistemdeki rolünü araştırm aktadır. IMF, geliştird iği orta ve uzun vadeli kredileriyle ve Üçüncü Dünya ülkelerinin d ış borçların ın ertelenm esi görüşmelerindeki çalışm alarıyla Bretton Woods konferan sında düşünülen rolünden uzaklaşmış, ve bu ülkelere önerdiği programların b a ş a r ıs ız ve t u t a r s ız olduğu iddia edilerek, rolü ve iş le v le r i daha çok t a r t ı ş ı l ı r duruma gelmiştir.

Anahtar sözcükler : u lu s la ra ra s ı para sistem i IMF, d ış borç sorunu ve b o rçla rın ertelenm esi

CONTENTS

1 INTRODUCTION ... 1

2. INTERNATIONAL MONETARY SYSTEM ... 4

2.1 Re quire roents o f the International Monetary System .... 4

2.2 Bretton Woods System ... 10

2..3 Flexible Exchange System... 15

.3. IMF's FINANCIAL FACILITIES AND CONDITIONALITY ... 19

3.1 Balance o f Payments Disequilibrium and Adjustment ... 19

3.2 IMF's Financial Facilities and Conditionalities ... 22

3.3 Use o f Fund Credit ... 29

4. CHANGING POLICIES AND NEW ROLES OF THE IMF ... 37

4.1 From Short Term Stabilisations to Medium Term S tru ctu ral Adjustments ... 37

4.2 New Organisator Role in the International Debt ... 42

5. CONCLUSIONS ... 52

6. NOTES ... 55

FIGURE 2.1_ US Reserve Assets & Dollar ... 13 FIGURE 3.1_ Use o f IMF Credit ... 35 FIGURE 3.2_ Use o f IMF Resource ... 36

LIST OF TABLES

TABLE 2.1_ Exchange Rate Arrangements Categories and number o f countries ... TABLE 3.1_ Possible Tranche Drawings and

Related Conditionality ... .

L INTRODUCTION

Before the Second World War, the world econoniy experienced a severe crisis (Great Depression,1929). The experience o f the 1930's, implicitly or explicitly, was the basis fo r the b e lief that an active stabilization policy was needed throughout the world to maintain stable economic performance.!

The International Monetary Fund (IMF) was formed in 1944 as "the chief organization in charge o f overseeing and monitoring the operation o f a new monetary order" . 2 The. d ra ft o f the Articles o f Agreement o f

the Fund, specifying the basic stru ctu re and rules o f the new monetary regime was prepared a t the Bretton Woods conference. At that time there was a strong body o f opinion or rath er the expectation that the Fund should be a regu lar intermediary between surplus and deficit countries, that the Fund resources should constitute the next line o f defence, a ft e r their own re serv es fo r the balance o f payments. In this context, the IMF was originally charged with overseeing on exchange rate system that was characterized by fixed or ra th er "pegged" exchange ra te s with adjustable parities but with fa ir ly infrequent changes in the exchange rates. This fixed exchange rate system was d ifferen t than the gold standard operated among major countries from 1880 to 1914.

In the Bretton Woods system the hey role o f gold was connected to the convertibility o f the US dollar into gold a t a fixed price. It lasted until August 1971 when the United States announced that it would no

longer fre e ly convert dollars into gold as before. Representatives from the countries were again gathered in December 1971 a t a meeting a t the Smithsonian Institution in Washington: a new agreement was reached that cen tral role o f the gold was removed from the system.

The world financial system has been in the r e a l floating exchange rate period since March 1973. But it is also argued that this system is not a true floating, nor is it a fixed rate but a "somewhat flexible exchange ra te system" because central banks do sometimes in terfere in the market to get their hands "dirty." The IMF whose major function by 1970s was to protect the fixed exchange rate system, allowing the •devaluations only to the limit o f one percent o f the original rates,

succeeded to adopt well to the system o f flexible exchange rates.

The major objectives o f the Fund are today o ffic ia lly to (i) promote cooperation among countries on international monetary issues, (ii) promote sta b ility in exchange rates, (iii) provide temporary funds to member countries attempting to correct imbalances o f international payments, (iv) promote free mobility o f capital flows across member countries, and finally (v) promote fre e trade. In other words its s u p ra -g o a l can be described as to encourage increased internationaliza tion o f business.

Referring to the Articles of Agreement o f the Fund, we see that the IMF would adhere to the "primary objectives o f economic policy" such as "the promotion and maintenance o f high levels o f employment and r e a l income and... the development o f the productive resources o f a ll members." But the IMF's role in this issue is found to be doubtful,

especially by "the developing countries and its terms o f conditionality fo r lendings to these countries are globally c o n tro v e rs ia l Before running into any scepticism about the inevitable role o f the Fund we will f i r s t highlight the requirements o f the international monetary system such as international money, an adjustment system, a control mechanism fo r sta b ility o f the system ,and then financial fa c ilitie s o ffe re d by the Fund ; second, examine the evolution o f the IMF's policies to respond to the changing requirements fo r the stab ility o f the system ; and third how f a r could it adhere to the above "primary objectives o f economic policy."

2. INTERNATIONAL MONETARY SYSTEM

The main characteristics o f the international monetary system are (i) the international money used by individual countries fo r clearing re sid u a l balances with others and fo r holding re serv es against contingencies and, fo r arranging values o f their domestic currencies in the foreign exchange markets; (ii) a medium fo r in stitu tional arrangements such as in terrelated banking systems, money and foreign exchange markets so th at international money can circulate within the system; (Hi) methods fo r dynamically arranging the distribution o f international money among the countries by adjusting the deviations from the balance o f payments o f the countries; and (iv) any kind o f control power to keep the system in the balance.

2.1 Requirements o f the International Monetary System

Int^ernatdonal Money

Gold was the only form o f international money in the past. But it was re la tiv e ly limited with resp ect to constantly growing world trade and its value was uns table. 3 Another form o f interna tio n al money is convertible currencies : a national currency is a fia t money and only is convertible if it is accepted or confirmed by other countries. But this convertibility is not risk less because a ll currencies are not equals A more recent form o f international money is the

Special Drawing Eight (SDR). Although this created liability o£ the IMF has a limited money function and forms a small proportion in the aggregate o f the international liquidity, its relativ e importance is much la rg e r in the system.5

Institutional Arrangements

The institutions o f international finance are the aggregation o f national banking systems including the cen tral banks, commercial banks and those specialized in overseas business; the spot and forward foreign exchange markets; and the international cap ital markets dealing with cap ital flows among countries. These institutions have been in continuous evolution, and their evolution was quite rapid especially a ft e r the Second World War; banking systems have ramified, foreign exchange markets have become more widespread, and Individual capital markets have been more integrated with the r e s t o f the world. So, while balance_of_payments problems resulted, until a few decades ago, from the disturbances to the current account, particularly to the trade items and were adjusted by changes in the cap ital account, today they mostly re s u lt from the cap ital accounts imbalances due to the flows occasioned by in te re st ra te d ifferen tials between the countries.^

That the cap ita l flows from one country to another is much e a sie r by wide range o f liquid a sse ts through electronic tra n s fe r media. All these developments have served capital to become more mobile. As will

ba shown la t e r in this study, capital -Flight due to this mobility has a considerable responsibility in the balance o f payments problem o f the developing countries.

Adjustment

Ad.justment procedui’e is the mechanism to re sto re equilibrium o f the balance_of_payraents, which is in part automatic and in part a matter fo r conscious choice among alternative policies. Adjustment mechanism is an e sse n tia l characteristic in the system, without which a ll international money would flow p ersisten tly to a few surplus countries and away from d eficit countries. Under the floating exchange rate system, the adjustment process is simple; a disequilibrium a lte rs the exchange rates and changes the relativ e prices o f the export goods o f the country. That is to say that, in either case, adjustment through changes in re lativ e prices corrects the disequilibrium in the balance o f payments i f the M arshall-Lerner condition-appropriate e la sticity conditions o f demand and supply fo r tra d ab le s- is satisfied. The choices o f a country facing a balance o f payments deficit can be listed as follows:

i) i f the country is well endowed with foreign exchange re serv es and the balance_of__payments d iffi culties seem likely to be transitory, then the disequilibrium can be le f t to correct i t s e lf decreasing the reserves;

ii.) i£ ‘the disequilibrium is in "the current account, the country may seek adjustment by reducing its domestic price le v e l relativ e to the price levels o f its trading competitors (but a t a certain cost o f unemployment); or

iii) the country may devalue its currency o r le t it depreciate as much as required in the floating system;

iv) if the disequilibrium is located in the cap ital account, adjustment may be sought by raising domestic in te rest rates relativ e to those abroad, providing that domestic financial market in the country is well developed and well integrated to the r e s t o f the world;

v) i f the above measures cannot be sa tis fa c to rily manipulated by the monetary o fficials, the country may re s o r t to direct controls on the current and/or capital account transactions.7

Although adjustment is an important requirement fo r the sta b ility o f the system, adjustment policies may conflict with domestic policies. Policies aimed a t employment, stable prices, economic growth and so cial w elfare are not usually compatible with the balance_of_payments policies. In the case o f a deficit, policies acted against d eficit lead in the long run to "domestic terras o f trade deterioration" and to absolute decline in the purchasing power o f domestic residents.8 For this reason, policy makers in the deficit countries are reluctant towards

balance_of_payinents adjustment policies.

Balance_of_payments disequilibrium is two sided; w-hen some countries give balance_of_payments deficits, some others must give surpluses. But in the case o f a surplus, the surplus country may be content to accumulate reserv es, re sistin g the demands o f d eficit countries fo r corrective action. While the sanctions operating against a d eficit country to adju st its deficit are pressing and forcing as in the case o f LDCs, those against a surplus country are moral or persuasive as in the case o f recent Japanese surpluses.

Balance _of_payments disequilibrium creates an allocation fo r international money and hence creates instability in the international monetary system. So s ta b ility in that system is directly correlated with the harmonization o f the balance o f payments policies and with the presence and strength o f the adjustment forces and policies within the system. This problem gives rise to the fourth fundamental characteris-. tic o f the international monetary system: coordinating and directing force by institutions a t the center o f the system.

Control o f the System

Control o f the international monetary system is a p olitical problem. The history o f the international economic relations over the past century demonstrates that the control was maintained by a few most powerful leader countries governing the system. Gold standard period (1870-1914) was the system functioned explicitly under the control and

with the cooperat ijn o£ the moat powerful countries. The period between the World Wars I and II was a period o f non-control and even chaos from point o f international financial cooperation and confidence. But the Bretton Woods system which was e ffec tiv e from 1945 to 1971 was a period o f control . To this end, the International Monetary Fund (IMF), General Agreements on T ariffs and Trade (GATT), World Bank (IBRD) were established as international monetary institutions. The present system imposes controls involving sanctions which are brought to bear against d eficit countries except the US. Permitting the control o f the system means some degree o f surrender o f national sovereignty fo r small countries. This is what makes the problem political; exchange rates and economic growth and even so cial welfare policies are supervised by external authorities. Contradictions and conflicts among the policies and methods o f supervision by these international financial institutions make th eir operations con troversial throughout the world. For instance, a voice from Chile comments :

"The Fund [the International Monetary Fund] does not seem to worry unduly about the extreme fluctuations that have taken place in the value of the dollar, which motivated, until very recently, a massive flight of capital from all over the world towards the US, with a number of additional economic disturbances in the other regions. Although the situation has turned around dramatically since mid-1985, it is still a valid assertion that the IMF does not interfere with US monetary and exchange policies, as it does with those of the Third World."’

Each o f these four requirements_Jnternational money, institutional arrangements, adjustment requirements and control mechanism participates

in enabling' the international monetary system to function. But one fea tu re is common to a ll the elements: i f the condition o f confidence is not universally met, these four elements are not su fficien t to provide a workable system. Particularly, failu re o f the confidence in international financial institutions such as the IMF may imperil the whole system.

The IMF was conceived in the Bretton Woods conference which initialized the fixed exchange rate period. In this period, the hiternational monetary system was organized around the IMF. When this period ended in 1971, the system evolved to adopt to the system o f flexible exchange rates. In the following two sections, these periods are studied from point o f the changing role o f the IMF.

2.2 The Bretton Woods System

The Bretton Woods conference brought about mainly , f i r s t the replacement o f the gold standard by the dollar standard fo r improved international money, and second the two financial institutions, the IMF and IBRD fo r the control o f the system. The principles o f the new Bretton Woods monetary system can be listed as follows:

i) value o f the dollar was pegged to gold a t a ra te o f $35 an ounce and currencies o f the members o f the IMF, except

the US, were valued in terms o f US dollar. Besides this, the U.S.A. was committed to exchange to gold a ll the dollars o f the other members' c en tral banks a t the fixed o ffic ia l rate;

ii) values o f _ -the a U the members' currencies could only flo a t within the margin o f one percent. Central banks o f the ' members would in te rfe re in their own exchange markets in order

to keep th eir rates within these limits. Dollar would be used in these interventions fo r being international money;

iii) the current accounts would be opened by the member countries, allowing fre e foreign trade; a ll currencies would be

convertible, t a r iffs and subsidization to export removed, and; iv) since the system was based on the fixed exchange ra te s, devaluations were considered to be the la s t r e s o r t fo r improving the balance o f payments disequilibria o f the d eficit members.

The primary i’esponsibility hence role o f the IMF was to a s s is t these countries in resolving "temporary balance o f payments problems." Through sh ort term loans and economic policy recommendations the IMF would help these countries adjust the periods o f balance o f payments disequilibrium. Finally if these aids and the proposed policies o f the IMF came out to be s t i l l insufficient, the IMF would give the permission to these member countries to devaluate their currencies by 10 percent or more as required. But the conditionality sought fo r this was the existence o f "s tru c tu ra l disequilibrium." And also , as will be emphasized la t e r in this study the IMF remained reluctant fo r such devaluations as i f it had dedicated i t s e lf to the fixed exchange rate systera.io

The Bratton Woods confex’ence, in short, made the dollar the world's key currency. The quantity o f international liquidity was tied to the supply o f dollar. For this reason, increase in the supply of international liquidity required the US balance o f payments deficits. But, in the years ju s t following the Second World War, the United States was running huge export surpluses, as much as $31.9 billio n fo r the period 1946-1949. In this case, the credits in the current account should be o ffs e t by the debits in the capital account in the form o f loans and grants made to the European countries under the Marshall Plan and other aid programs.n Financial meaning o f these aids was that the US was pumping to the system the required amount o f international liquidity. During the 1950-65 period, the US s t i l l maintained balance of trade surpluses but a t the same time made large r amounts o f foreign aid and cap ital investment abroad. That is to say that although the U.S. gave trade surpluses o f $21.9 and $38.8 billion in the successive periods o f 1950-57 and 1958-65 respectively, due to overfinancing the export surpluses it gave increasing balance o f payments deficits a ll adjusted by the increased supply o f dollars with no burden or cost to the United States. This caused large dollar balances to be accumulated in the r e s t o f the world while the US gold supply was decreasing. As shown in Figure 2.1, US gold reserves f e l l from a $25 billion in 1950 to $10 billion in 1970. During the same period, dollar claims against the US gold supply increased from around $5 billion to $70 billion.

FIGURE 2.1 US RESERVE ASSETS & DOLLAR

LIBILITIES TO FOREIG-NERS, 1950- 75 Y E A R S □ US $ LI ABI LI TI ES S o u r c e ; P o o l and S t amos (19 8 7 ), p,45 + US G-OLD RESERVESThe Bretton Woods system was s e t up around the IMF whose major function was to provide its members with international money in case they are short o f it. US dollar and gold were interchangeable as international money and stocks o f both were held by the Fund as well as by its members. As f a r as the international liquidity is concerned, the IMF was not s a tis fa c to ry in its major function to provide the member countries with the required international money. Because 75% o f the

IMF's fund was creatad as a paol o f a ll membez’s' currencies, most of which were quite useless to adjust the balance_of_payments deficits o f the members. For this reason the IMF was short o f US dollars as international liquidity. Increases in members' quotas, with the General Agreements to Borrow o f 1960 and with the Rio Agreement o f 1967 to s e t up the SDR system and the flush o f petro_do liars and euro _do liars reduced the e ffe c t o f "less o f dollars and more o f many national currencies" with the IMF.

As previously explained, exchange rates were to be kept fixed in the sh o rt terra and balance_of_payments dis equilibria should be met by re se rv e tra n sfers, supplemented by drawing on the Fund. Although the IMF, in the long run, was going to permit the exchange rates to be fre e ly devaluated (revaluated) when necessary to adjust the balance_of_payments deficits (surpluses), it disregarded this condition and s t r ic t ly opposed frequent changes in the exchange rates o f key currencies. But this le f t the system without any flexibility with resp ect to the exchange rates. Consequently, demand fo r the US dollars to adjust the balance_of „payments deficits o f the member countries increased. This development was the underlying reason o f the large US d eficits and the so called "dollar glut", which accelerated the failu re o f the confidence in the system. The outburst o f the world trade and increasing balance_of_payments imbalances, and the above mentioned developments brought the system to the inevitable breakdown.

Although the IMF was s e t up with - g rea t expectations, its authority was limited a t the beginning. During the period o f Marshall Aid

(1948-1952) it was th ru st into the bachgi-ound, and organisations l-ilr·:^ the OEEC and the European Payments Union came to power. In its f i r s t decade, the IMF opposed any attempt on the part o f members to free exchange rates, and demonstrated a strong American influence on its a ffa irs . In the 1950s it returned to the center o f the system but s t i l l having the inability to lead in solving the financial problems o f the world. The IMF, until 1971, made its contributions to solving the problems, but they were peripheral rather than centrales

2.3 Flexible Exchange System

Within a few years o f the breakdown o f the Bretton Woods, leading countries allowed their currencies' exchange rates to float, and some others pegged their ra te s either to a currency or to an appropriate basket o f currencies. The new system brought about two things: (i) Special Drawing Right (SDR)_ a created liability o f the IMF_ and currencies o f some Industi'ial countries replaced the gold and dollar fo r holding rese rv e s and fo r intervention and; (ii) members of the IMF were permitted to control over their own exchange rates. The Board o f Directors o f the Fund approved two fundamental decisions in 1973 and 1974. These decisions were titled as "Central Limits" and "Guidelines fo r the Management o f Floating Exchange Rates" according to which, shortly, the members could control their currencies by 2.5 % above and below th eir cen tral limits and moreover, providing that the Fund be informed, they could s e le c t the regime o f "multiple exchange rates.

Proposal fo r the Second Amendment was put into e ffe c t in April 1978. This Second Amendment o f the IMF clearly approved the flexible exchange ra te system o f controllable type in which the members would be fre e to se le c t their own exchange rate policies. Members could make m ultilateral agreements fo r seeking compatible macro economic and monetary policies fo r stable exchange rate system. The categories o f the exchange rate arrangements and number o f countries Included in these categories as o f September 30, 1986 are shown in Table 2.1.15

Table 2.1

Exchange Rate Arrangements

Categories and number o f countries Pegged to Single Currency

U.S. dollar French franc Other

Pegged to Currency Composite SDR

Other

Flexibility Limited v is -a -v is single currency Flexibility Limited v is -a -v is group o f currencies More Flexible Adjusted Managed floating Independently floating T o tal 50 41 5

8

46 31 14 5 10 316

20

20

150 S o u r c e ; IMF, F l o a t i n g Ex c h a ng e R a t e s in D e v e l o p i n g C o u n t r i e s E x p e r i e n c e wi t h A u c t i o n and I n t e r b a n k Ma r k e t s , May 1987.by 32.5 % o f which 25 % was accepted to be payed in SDR and in other convertible currencies in lieu o f gold. One o f the major differences o f this period from the Bretton Woods period was the demonetization o f the gold. The IMF f i r s t removed the requirement fo r 25 % o f the quota to be payed in gold and then sold half o f one_third o f its gold reserves in the market and gave back the other half to the members. By this revenue, the IMF established a fund to help improve the balance o f payments deficits o f poor countries with less than SDR 300 per capita.

The years 1970s were under the pressure o f inflationary trend in the world economy. The world prices in the 1960s had increased by only 1 %, but increased by 6-7 % between the years 1970-72 and by almost 90 % between 1973-75, resulted to a grea te r extent from that petroleum prices increased more than 6 times in this period. In the 1970s, the IMF acted against this worldwide inflationary going with its financial and policy assistance to the applicant deficit countries and decided on " a uniform policy o f deflationary adjustment_ instant currency devaluation, a balanced budget and a package o f deflationary reductions in government outlays and consumption.''i6

From point o f the effectiven ess o f the IMF and from point of viability o f its role, the flexible e.xchange rate system strengthened the requirement fo r the international monetary system the control as that o f the IMF. In this system, in order to achieve exchange rate stab ility it was necessary to achieve a common pattern o f macro policies. Because, divergent macro policies, especially among the "target zone" countries would lead the system to drawbacks i f not to breakdown: when

"these Goun"tries ixifle"te or defl^^be toge'thei·’, exchange i"’at,es will remain constant, in this case there is no problem, but when some inflate and others deflate, the exchange rates diverge to harm the stab ility o f the system. In this context, the IMF's control role includes also the supervision o f the harmonization o f the macro policies o f member countries.

3. IMF'S FINANCIAL FACILITIES AND CONDITIONALITY

Article I(ii) o f the Fund Articles o f Agreement s ta te s that a purpose o f the IMF is "to fa c ilita te the expansion and balanced growth o f international trade, and to contribute thereby to the promotion and maintenance o f high levels o f employment and r e a l income and to the development o f the productive resources o f a ll members.” It is further state d in the Article I(v) that another purpose o f the Fund is to "give confidence to members by making the general resources o f the Fund temporarily available to them under adequate safeguards , thus providing them with opportunity to co rrect maladjustments in balance o f payments without reso rtin g to measures disruptive o f national or international prosperity." However evaluations o f "maladjustments in the balance o f payments” by the IMF evolved and conditionalities fo r lendings to the members changed in the course o f the history o f the IMF.!"^

.3.1 Balance o f Payments Disequilibrium and Adjustment

Since the Bretton Woods conference, there have been changes in the IMF's concepts o f balance o f payments disequilibrium and the adjustment process. Before the 1970s there were tliree Idnds o f situations recognized. The f i r s t one was considered to be caused by a reversible loss o f markets or reduction in the terms o f trade. It was regarded to be temporary and required no change in policies and no adjustments.

IMF's I’esources would supplement the country's own reserves. The country's re se rv e position would be restored when external conditions and terms o f trade were improved. The second type o f disequilibrium was a consequence o f excess demand resulting from expansionary monetary and fis c a l policies. In this case demand management was required by the Fund fo r drawings in the higher credit tranches. The third situation which was not originally defined in the Articles o f Agreement was the "fundamental disequilibrium" that internal and external prices were so divergent that an adjustment o f the country's par value or exchange ra te was required. Although the f i r s t type o f disequilibrium required no conditionality, stand_by agreernents fo r the other two types o f disequilibrium involved fis c a l and macroeconomic monetary, and fis c a l policies, with exchange rate adjustment in the case o f fundamental dis equilibrium.

In each case o f above situations, some financing might be called for, but it was to be temporary financing to bridge a gap until the balance o f payments restored. So the Fund's resources would therefore revolve. Until 1970s the IMF was originally in the business o f making temporary loans. It had a duty to make sure that those loans would indeed revolve, which required that it ensure that adjustment was taking place i f the deficit was not inherently se lf-re v e rs in g . That was the purpose o f the two types o f conditionality.is

Low conditionality involves merely establishment that a country declares it has a "balance o f payments need" and it is taking measures to resolve its deficit problem. In this case there are no o ffic ia l

performance cri-tei’da for’ following the country's situation. But high conditionality involves the country's design o f a specific s e t o f measures to eliminate its deficit, and Fund agreement that the program will be adequate fo r that purpose, and the country's commitment to implement the program.

The collapse o f the Bretton Woods system and the f i r s t o il shock in 197.3 created a more uncertain and d ifficu lt international climate fo r many developing countries. It was accepted by the IMF that there were economies "characterized by slow growth and inherently weak balance o f payments positions" which are not temporary. There were also economies "su fferin g serious payments imbalances relating to s tru c tu ra l maladjustments in production and trade." In this context, the IMF identified new kinds o f disequilibrium that c a ll fo r both financial assistance over a longer term and additional policy instruments as will be listed below. Thus two main categories o f problems were defined: "(1) Serious imbalance relating to s tru c tu ra l maladjustments in production and trade and where cost and price distortions have been widespread, and (2) an economy characterized by slow growth and an inherently weak balance o f payments position which prevents pursuit o f an active development policy. "19

Under the f i r s t categoi’y the disequilibrium was defined to be caused by "external shocks," which were best represented by the sudden rise in o il prices in 1973-74 and again in 1979-80. The second category o f payments imbalance covered the typical slow-growing poor developing countries.

Amid t,hs changing financial ays tern, the IMF has flexibly adopted its c red it policies to the changing perceptions o f financial needs of members and its role. Members' access to Fund credit has been greatly expanded in relations to quotas through both the liberalization o f basic financing and the addition o f special fac ilitie s o f longer term.q. This evolution finally brought the IMF near to the traditional expertise o f the World Bank (IBRD), with medium-term stabilisation programs which explicitly recognized the links between balance o f payments adjustments and resource mobilization and between stabilization and production. More technically spealdng, the IMF added the "supply side adjustment policies" to its rep ertoire other than the cliche o f "demand management."

.3.2 IMF's Financial Facilities and Conditionalities ■$

The fund was created as a pool o f currencies and gold subscribed by its members in proportion to their quotas as indicated before. The quota has fou r functions: it determines (1) members' subscription to the Fund, (2) voting rights o f members, (3) their borrowing rights on the Fund, and (4) their share o f any allocations o f SDRs. Each member contributed a qu arter o f its quota in gold and the remainder in its national currency. In return fo r accepting that its currency might be drawn by another member, every member acquired the right to draw other currencies under certain circumstances. So "drawing" from the Fund involves a purchase o f another country s currency mostly which are called hard currencies in exchange fo r its own currency, and a repurchase

o f its own currency by paying back the foreign currency. These transactions are borrowing from, and repayment to the Fund.

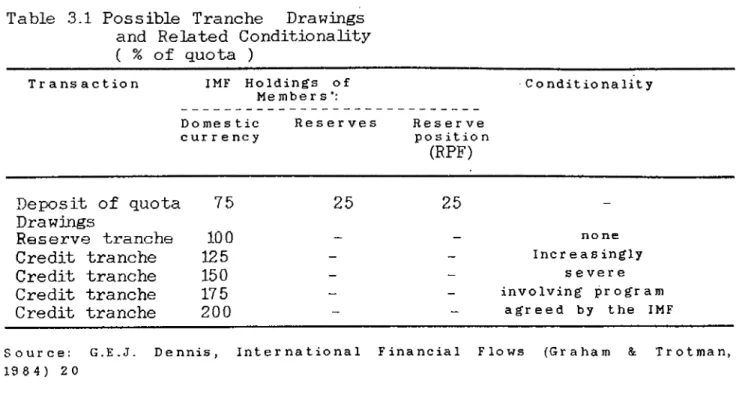

A member's quota used to constitute the ceiling on its permissible borrowing, which was divided into five equal tranches: the f i r s t one is reserve tranche, which was originally called "gold tranche", the other four tranches are known as cred it tranches as shown in Table 3.1. At the stage o f reserv e tranche, the member is merely withdrawing the liquidity it deposited with the Fund as part o f its membership

I

subscription. The f i r s t o f the credit tranches has been available on e a s ie r terms than the other three higher cred it tranches. Although this Credit Tranche Policy is the Fund's basic financial facility, since the 1950s a v ariety o f additional fa c ilitie s have been added, the cumulative e ffe c t o f which has been to create the possibility o f members' borrowing as much as over five times their quota. From the mid-1950s, low conditionality was applied to the f i r s t credit tranche. Any member requesting a drawing in this stage was expected to make only reasonable e ffo r t s to overcome its balance o f payments problems. But there are no c rite ria by the IMF to measure the effectiven ess o f these e ffo rts, which is up to the borrower's discretion. Drawings from the higher credit tranches are su bject to a high degree o f conditionality. They are provided in the form o f a stand-by agreement^ this provides the member with assurance o f a right to draw in a se rie s o f Installments over specified years. These installments are available su bject to the observance o f conditions known as performance criteria. When o r i f the member violated the conditions o f the arrangements, it became ineligible

to dx-aw fui-bhex' instaliments. It is also woi-th noting' that there is a s h ift in the Fund credits from low conditionality to high conditionality since the mid-1970s.

Table .3.1 Possible Tranche Drawings and Related Conditionality ( % o f quota ) T r a n s a c t i o n IMF H o l d i n g s o f Member s * : Dome S t i c c u r r e n c y R e s e r v e s R e s e r v e p o s i t i o n (RPF) C o n d i t i o n a l i t y Deposit o f quota 75 Drawings Reserve tranche 100 Credit tranche 125 Credit tranche 150 Credit tranche 175 Credit tranche 200 25 25 none I nc r e a s i n g l y s e v e r e i n v o l v i n g p r o g r a m a g r e e d by t he IMF S o u r c e : G.E. J. D e n n i s , I n t e r n a t i o n a l F i n a n c i a l F l o w s ( G r a h a m & T r o t m a n , 1984 ) 20 Basic Financing

As stated above and shown in Table 3.1, drawings in the resex-ve tranche, which merely return to the member resources it has provided, are readily available without any condition. Further drawings are in the credit tranches and are normally su bject to conditions. Although these credit tranche drawings are not "loans" officially, they are economically equivalent to loans and are generally fo r balance o f payments support rath er than . fo r development projects. When the Fund was established, there were controversies on what conditionality should be put on the

Fund credits. A policy on conditions fo r their use was adopted in 1952. It was re sta te d and elaborated most recently in a 1979 executive board decision. 21

Credit is extended under a stand-by arrangement, which assures a member that it may draw on the Fund up to a specified amount in a given period without fu rth er review o f its policies, provided it has observed the conditions and other terms o f the arrangement. These stand-by arrangements originally have allowed drawings during a one-year period, and members have been expected to automatically repay Fund credit within three to five years. But in the 1970s as stated, above, balance o f payments problems were not "temporary" anymore; to adopt this, the 1979 board decision on access to Fund credit stated that: " in helping members to devise adjustment programs, the Fund will pay due regard to the domestic so c ia l and p olitical objectives, the economic priorities, and the circumstances o f members, including the causes o f their balance o f payments problems...[and performance c rite ria ] will normally be confined to (i) macroeconomic variables, and (ii) those necessary to implement specific provisions o f the Articles [o f Agreement] or policies adopted under them." Other performance c rite ria may be adopted only "in exceptional cases when ... e sse n tia l fo r the effectiven ess o f the member's programs

-I

because o f their macroeconomic irapact. 2 2

The original Articles o f Agreement limited a member's drawings in any one year to 25 percent o f its quota unless the Fund granted a waiver. But no waiver was granted until 1953. However in the f i r s t years, most o f the drawings were unconditional (during the f i r s t five years o f

opei-ations, only 32 percent o£ a ll drawings f e l l in the f i r s t credit tranche with low conditionality). A fter the mid-1950s, waivers became more common because balance o f payments could not be restored in short periods as before. And finally the annual limit on drawings was eliminated by the Second Amendment.

Special F a cilities

The IMF originally provided only temporary balance o f payments finance, distinct from other capital account transactions (which were mostly under the responsibility o f the World Bank). Over the years, as state d above, financial requirements fo r the stab ility o f the system changed and the interpretations o f the IMF's beginning principles (Articles o f Agreement and issues a t the Bretton Woods Conference) were interpreted to allow the establishment o f policies or fa c ilitie s to meet special balance o f payments problems associated with the differen t needs o f particu lar classes o f members and also to permit lengthening the period o f continuous use o f IMF financial resources and providing explicit subsidies fo r poor countries. It is these special fa c ilitie s that “edged the Fund more directly into the realm o f traditional World Bank expertise."2 3

Compensatory Financing' F a cility (CFF) was f i r s t created in 1963, principally to a s s is t primary producing countries, particularly in providing " financing to members su fferin g an export s h o r tfa ll o f a short-term character... largely attribu table to circumstances beyond the control o f the member." It was la t e r modified to expand access and to

requii’e fo r large drawing's in relation to quota that the Fund be s a tis fie d that the meraber is ju s t on the way to correct its balance of payments deficits. Guidelines approved by the executive board in 1983 in terp ret the requirement o f cooperation with the Fund fo r an upper credit tranche drawing under the compensatory financing facility as equivalent to meeting the usual conditionality standards fo r an upper credit tranche program.

Buffer Stock Financing F a cility (BSFF) was established in 1969 fo r sa tisfy in g the demands o f the developing countries that the Fund payed g re a te r heed to the problem o f stabilisation o f prices o f primary products. Lihe the Compensatory Financing Facility, the Buffer Stock Financing Facility required only such conditionality as cooperating with the Fund in finding appropriate solutions to any payments problems.

Oil F a cility and Subsidy was f i r s t established in 1974, responding to sharp increase in o il prices. For the 1974 facility, the conditionality was minimal but when it was modified in 1975, drawers were required to describe th eir medium-term policies to deal with their balance o f payments problems and to make economy on o il consumption or to develop altern ative energy sources. This fa c ility is also important from point o f view that it was used by in dustrial countries as well as developing countries.

Extended Fund F a cility (EFF) happened to be a milestone in the evolution o f Fund policies· when it was established in 1974, it was obvious that some countries needed longer time to solve their serious balance o f payments problems because o f stru c tu ra l maladjustments in

pi’CiductiDn and tz-ada. Foi’ t,his z’aason Extended Fund Facility was introduced with the intention o f providing longer term finance to support th re e -y e a r programs involving s tru c tu ra l adjustments. The programs involve drawings in, installments and performance criteria. Loans from this fa c ility have a maximum terra o f ten years, as against the fiv e -y e a r maximum that applies to the other facilities.

Supplementary Financing F a cility (SFF) was established in 1977 and became operational in 1979. It was intended to provide resources in much la rg e r amounts and large r periods than are available under the Credit Tranche Policy or Extended Fund Facility to members with serious balance o f payments problems that are large in relation to their quotas. Commitments are no longer made under this fa c ility since it was replaced in 1981 by the Enlarged Access Policy which serves the same purpose, allowing stand-by arrangements to be extended beyond the higher credit tranches, or extended arrangements to be enlarged beyond the regular limits, on the basis o f resources borrowed by the Fund under b ila te ra l arrangements. These resources carry a higher in te rest rate than the Fund's regu lar facilities.

Structural Adjustment F a cility (SAF) was established in 1986, which marks a significant new phase in the World Bank-Fund collaboration. Being the most recent fac ility o f the Fund, the SAF would be available to low-income countries which face protracted balance o f payments problems and are currently eligible fo r IDA resources. To gain access to the SAF, a member must develop a "policy framework describing the member's medium-term objectives and the main outlines o f the policies to

be followed in pursuing' these objectives".2 4 "The policy framework would be developed jointly with the s t a ffs o f the Fund and World Bank, and would describe the "general outlines" o f a th re e -y e a r adjustment program including stru c tu ra l measures, and delineate in broad terras the expected path o f macroeconomic policies.

Enhanced Structural Adjustment F a cility , (ESAF) was established in December 1987. Tins fac ility expands the concessional resources available to low-income developing countries with strong adjustment programs. The objectives, eligibility, and basic program features are p a ra lle l those o f the SAF, but the two fa c ilitie s d iffe r with respect to the provisions governing access, conditionality, monitoring, and funding.

Compensatory and Contingency Financing F a cility (CCFF) was established in August 1988. This most recent fa c ility combines assistance to compensate members against exports sh o rtfalls and excesses in c ereal imports cos t s . 2 4

Of the special fa c ilitie s o f the IMF, the Compensatory Financing Facility, the B u ffer Stock and Oil fa c ilitie s, and CCFF are applied with low conditionality. But high conditionality is applied to the EFF, SFF, SAF and ESAF-2 5,2 6 On the other side, SAF and ESAF also require the

consultative cross conditionality by the World Bank

.3.3 Use o f Fund Credit

The chronology o f the IMF's financial fa c ilitie s shows the evolution that it has flexibly adopted its credit policies to changing perceptions

o£ financial needs and its role. By establishing the Extended Fund Facility in 1974, the IMF conceded that the balance o f payments deficits o f developing countries were less amenable to quick correction than previously had been considered. But however, this facility has been used less frequently than might have been expected: during the firs t· ten years a ft e r it was established, there were outstanding twenty-nine stand-by arrangements and only .four extended arrangements. At this point, there were criticisms to the IMF that special fac ilitie s were unnecessary because the needs could have been met by a flexible application o f policies governing access to the Fund's regular financing. 2 7

Member countries obtain economic resources as IMF credit, as explained earlier, providing loans to be returned to the Fund within three to five years or in some cases, ten years. The IMF charges are lower than market in te rest rates, but since 1970s the IMF became much more a lender o f la s t re s o rt because o f its lendings subject to conditionality. As pointed out in Section 2.1, adjustment policies or policies fo r restorin g external balance were recognized to conflict with domestic policies countries would like to pursue fo r their domestic economies. IMF's demand management requirement such as tight fis c a l and monetary policies as conditionality fo r lending to LDCs were not e asily accepted by the elected policy makers o f these countries. But IMF's duty was to make sure that those loans would revolve, requiring that it ensure that adjustment should take place to re sto re the external balance. Since the balance o f payments problems reflected

mostly from raacrueconomic pz’obleras such as poor resource mobilisation, sta b ility and production, the IMF shifted from short-term financial assistan ce to medium term stabilization programs, with longer return periods fo r credits, and hence higher risks fo r the IMF. The record o f the use o f IMF credits in years clearly shows the sh ift from low conditionality to high conditionality. Figure 3.1 depicts the situation that high conditionality credits were negligible in the mid-1970s as compared to the low conditionality credits fully reversed in the mid-19 8 0 s . 2 8

The Fund's stereotyped image in the LDCs became easily that o f an ordinary cred itor which inflexibly insisted on demand management which is a tough decision fo r elected governments in these countries. In this context, countries with access to the international capital market in normal circumstances were reluctant to apply to the IMF fo r financing th eir payments deficits. Only when they exhausted their creditworthiness they turned to the IMF, to get a "sea l o f approval' o f their creditworthiness as well as to finance their deficits. For these countries such as Britain, Italy, Peru and Portugal, IMF's high conditionality credits were means to re sto re their creditworthiness in the international market.2 3 This development might have given rise to the most recent role o f the Fund_ organizatör role in the debt negotiations, which will be studied in the next section.

There is also a second group o f countries which are permanent clientele o f the Fund from the poor LDCs. Because these countries have no altern ativ e financial sources fo r not being creditworthy, they s t i l l

need the Fund whatever the conditionality is. But they have "an in te re s t in the retention and extension o f the low conditionality fa c ilitie s so as to provide them with access to low-conditionality credit whenever a payments deterioration is due to circumstances beyond their own controL"3 0

Developing countries have used Fund credit to a much g reater extent than in dustrial countries in absolute amounts and especially in relation to th eir quotas. From 1947 through mid-1980s, the cumulative use o f Fund credit by non-oil developing countries equaled 232 percent o f their quotas whereas that by industrial countries 28 percent. In absolute amounts, almost 76 percent o f the Fund credit was used by non-oil & non-Indus t r i a l countries, o f which almost 65 percent was obtained through the above mentioned special fa c ilitie s .31

There was also a significant change in the distribution o f use o f Fund credit among groups o f members: until 1973,- drawings by industrial countries accounted fo r 54 percent o f t o t a l Fund credit, but in the period 1974-1984, the share o f industrial countries f e ll to 14 percent. So the flexible exchange rate system made the industrial countries less dependent upon IMF resources. In recent years the IMF has turned out to be a cred itor to the LDCs because no industrial country made an ordinary credit drawing from the Fund since 1977.

With the establishment o f the SAF and la te r ESAF the IMF was appeared to be rather a lender to the poorest countries_mostly African countries. SAF was designed as a d e b t -r e lie f facility to "allow the poorest countries to borrow more cheaply and over a longer period than

is prissible "thi’Ciugh the IMF''s other forms o f assistance. China and India volunteered not to draw on it, so most o f the resources are available fo r Africa. "3 2

The combination o f the special facilities provided by the Fund and the continuation o f the requirement fo r external financial aid by most o f the countries due to severe economic problems encountered resulted in prolong'&d use o f IMF ci'edit by these member countries. Records show that tw enty-four member countries made use o f Fund credits fo r periods o f a t le a s t eleven continuous years, during the tree decades ended in mid-1 9 8 0s .3 3 Herein there is one certain point that the cases of

prolonged continuous use o f IMF credit can not be accounted fo r the success o f the Fund's facilities, but can be attribu table to unforeseen adverse external conditions or policy failures by the Fund. On the other side, only ten o f these twenty-four countries were granted credits under the extended Fund Facility, which normally allows a period o f repayment up to ten years.

When records o f use o f Fund credits are examined, many LDCs are found to be dependent on IMF credits fo r a long time. But "the t o t a l o f cred it outstanding began to f a l l a ft e r 1985 and the IMF has become a net recipient o f capital from the developing countries. For this it is much criticized."3 4 However, this situation may be only temporary as it was in the period o f 1977 to 1980; then, as shown in Figure 3.2, the IMF was able to increase again its credits to LDCs. But the recent situ ation is much d ifferen t as was written by The Economist on September

24, 1988: "...'the debt troubles rumble on, and the Fund has become increasingly compromised by them. The revolving short-term nature o f its various credit fa c ilitie s made it impossible to sustain the in itial b u rst o f new lending a ft e r 1982."

FIG-URE 3.1 USE of IMF CREDIT

cC O U) E O 5 6 -5 - z 3 -2 -■ Z x i z z z zfn

N z \ z z ,Nz

z z 1 9 7 6 1 9 7 7 1 9 7 8 1 9 7 9 1 9 8 0 1 9 8 1 1 9 8 2 1 9 8 3 Y E A R S\Z7\ LOW C ON D I T I O N A L I T Y [ V ^ HIG-H COND I T I ONAL I T Y

S o u r c e : K e t t e l a n d Ma g n u s (19 8 6 ), p . l 0 2 .