Original Article

Gynecol Obstet InvestPro-Gastrin Releasing Peptide:

A New Serum Marker for

Endometrioid Adenocarcinoma

Mine Kiseli

aGamze Sinem Caglar

aAsli Yarci Gursoy

aTolga Tasci

bTuba Candar

cEgemen Akincioglu

dEmre Goksan Pabuccu

aNurettin Boran

bGokhan Tulunay

bHaldun Umudum

daDepartment of Obstetrics and Gynecology, Ufuk University Faculty of Medicine, Ankara, Turkey; bEtlik Zubeyde Hanim Women’s Health Teaching and Research Hospital, Gynecologic Oncology Clinic, Ankara, Turkey; cDepartment of Biochemistry, Ufuk University Faculty of Medicine, Ankara, Turkey; dDepartment of Pathology, Ufuk University Faculty of Medicine, Ankara, Turkey

Received: November 15, 2017 Accepted after revision: March 27, 2018 Published online: June 13, 2018

DOI: 10.1159/000488854

Keywords

Pro-gastrin releasing peptide · Endometrial cancer · Adenocarcinoma · Tumor marker · Cancer

Abstract

Background: Gastrin-releasing peptide (GRP) is thought to

play a role in the metastatic process of various malignancies. The more stable precursor of GRP, pro-GRP (ProGRP), has been shown to be secreted by neuroendocrine tumors. This study was designed to assess the validity of ProGRP as a di-agnostic marker in endometrioid adenocarcinomas (EAs) of the endometrium. Methods: Thirty-seven patients with a di-agnosis of EA, 23 patients with endometrial hyperplasia, and 32 age-matched controls with normal endometrial histology were recruited for this study. Serum ProGRP and cancer an-tigen 125 (CA125) values were compared between groups.

Results: Median serum ProGRP levels were significantly

higher in the cancer group compared to corresponding lev-els in both the hyperplasia and control groups (p = 0.008 and p < 0.001 respectively; endometrial cancer: 27.5 pg/mL; hy-perplasia: 16.1 pg/mL; controls: 12.9 pg/mL). Age and

endo-metrial thickness were positively correlated with ProGRP lev-els (r = 0.322, p = 0.006 and r = 0.269, p = 0.023, respectively). Receiver Operating Characteristic curve analyses for EA re-vealed a threshold of 20.81 pg/mL, with a sensitivity of 60.7% and specificity of 81.4%, positive predictive value of 68% and negative predictive value of 76.1%. Conclusion: Significantly higher ProGRP levels were observed in patients with EA than in controls. Serum ProGRP has good diagnostic sensitivity and specificity for EA. © 2018 S. Karger AG, Basel

Introduction

Endometrial cancer is the most common gynecologi-cal cancer in developed countries [1]. The increased inci-dence of endometrial cancer in high-income countries could be related to greater overall prevalence of obesity and metabolic syndromes as well as the aging of the pop-ulation [2]. Endometrial cancers can generally be catego-rized into 2 broad groups: endometrioid adenocarcinoma (EA) or type I, and non-endometrioid endometrial

carci-nomas or type II tumors [3]. The most common histo-pathological type (80%) is EA, which is dependent on un-opposed estrogen, and typically arise from a background of atypical endometrial hyperplasia.

Gastrin-releasing peptide (GRP) is a mammalian ho-mologue of bombesin, and is expressed in the hypothala-mus, anterior pituitary, gastrointestinal tract, lung, and pancreas [4]. GRP is thought to act in the metastatic pro-cess by autocrine activity or by cell-to-cell interactions [5]. The more stable precursor of GRP, ProGRP, which is a 125-aminoacid prohormone, can be measured in both the serum and plasma. Neuroendocrine tumors have been shown to secrete significant amounts of ProGRP [5]. Recently, it has been used as a tumor marker to diagnose small-cell lung carcinoma (SCLC), and it has shown high sensitivity (86.5%) in discriminating SCLC from benign lung diseases [6, 7].

GRP is documented to be present in the uteri of preg-nant sheep, cattle, and humans [4]. GRP receptors were shown to be expressed in the myometrium, endometrial glands, and endometrial blood vessels of the uterus [8, 9]. Dumesny et al. [10] demonstrated significant in vitro concentrations of ProGRP N-terminal immunoreactivity in cell lines derived from endometrial cancers. In this clinical context, we aimed to investigate the levels of se-rum ProGRP in patients who had a histopathological di-agnosis of endometrial hyperplasia and endometrial can-cer. Moreover, the predictive value of this serum marker for diagnosing endometrial hyperplasia and endometrial cancer was also elucidated.

Materials and Methods

This prospective case-control study was performed between April 2014 and September 2015 at a university hospital and ter-tiary care setting. The study protocol was approved by the local Ethical Committee (number: 280320142) and written informed consent was obtained from each participant. During the study pe-riod, all gynecological patients who underwent endometrial biop-sy for various indications (e.g., abnormal uterine bleeding, in-creased endometrial thickness visible on transvaginal ultrasound, postmenopausal bleeding) were invited to participate in the study. Thirty-seven patients with a diagnosis of EA, 23 patients with en-dometrial hyperplasia, and 32 age-matched controls with normal endometrial histology as determined by biopsy (i.e., no hyperpla-sia/cancer) were recruited. Exclusion criteria included concomi-tant or prior cancer diagnosis, history of cancer treatment, and patients with renal failure.

Demographic data (i.e., age, gravidity, body mass index [BMI], menopausal status, menopause duration), medical history (i.e., chronic medical diseases), renal function tests (i.e., blood urea ni-trogen [BUN], creatinine), endometrial thicknesses observed on

transvaginal ultrasound, and histopathologic diagnosis were re-corded. BMI was defined as body weight (in kilograms) divided by the square of the body height (in meters) and was expressed as kg/ m2. The classification of hyperplasia was based on the World

Health Organization 1994 classification, as updated in 2003 by the Society of Gynecologic Pathologists (ACOG Committee opinion). The staging for EAs followed the International Federation of Gy-necology and Obstetrics staging system [11]. All biopsy specimens were interpreted by gynecologic pathologists. The postoperative surgical pathology reports for the cancer patients included tumor histology, tumor grade, tumor size, extent of myometrial invasion, presence of extrauterine spread, or cervical invasion, and status of the lymph nodes if lymphadenectomy was performed.

The serum samples for ProGRP and CA125 analysis were taken at the time of endometrial biopsy. The samples were immediately centrifuged and stored at –80 ° C until assayed for ProGRP and

CA125. ProGRP was measured in the serum using chemilumines-cent microparticle immunoassay technology with flexible assay pro-tocols referred to as chemiflex. First, the sample, assay diluent, and anti-ProGRP-coated paramagnetic microparticles were combined. Any ProGRP present in the sample became bound to the anti-ProGRP-coated microparticles. After washing, the anti-ProGRP ac-ridinium-labeled conjugate was added to create a reaction mixture. Following another wash cycle, pre-trigger and trigger solutions were added to the reaction mixture. The amount of ProGRP in the sample is directly related to the relative light units detected by the ARCHI-TECT i System Optics (Abbott, Germany). A commercially avail-able kit (1P45 ARCHITECT ProGRP Reagent Kit, Abbott, Germa-ny) was used for ProGRP analysis, with a functional sensitivity of ≤3 pg/mL at a total coefficient of variation of 20%. CA125 levels were measured using the Abbott i2000. The CA125 measurement meth-od used chemiluminescent microparticle immunoassay technology and flexible assay protocols referred to as chemiflex (Abbott Archi-tect iSystems Assay Parameters, Germany). Intraassay and interas-say coefficients of CA125 variation were 3.2 and 3.9% respectively. Serum creatinine was measured using the kinetic alkaline picrate methodology. BUN was measured with an enzymatic calorimetric assay, using commercially available kits (Abbott Architect cSystems Assay Parameters-Clinical Chemistry, USA).

Statistical Analysis

Data analysis was performed with SPSS for Windows, version 17.0 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA). Whether the distributions of continuous variables were normal or not was determined by the Kolmogorov Smirnov test, and the homogeneity of variances was evaluated by the Levene test. While all continuous variables were expressed as mean ± SD or median (min–max), the number of cases and percentages were used for categorical data. The statistical significance of the differences in medians between 2 independent groups was determined by the Mann Whitney U test. The mean differences among more than 2 independent groups were analyzed by one-way analysis of variance, and the Kruskal Wallis test was applied for comparisons between medians. When the p value from the one-way analysis of variance or Kruskal Wallis test was statisti-cally significant, post hoc Tukey HSD or Conover’s multiple com-parison test were used to determine which group differed from the others. Categorical data were analyzed with Pearson’s chi-square test. Degrees of association between grade and laboratory mea-surements were evaluated by Spearman’s rank correlation analy-ses. The optimal cutoff point for using ProGRP to determine

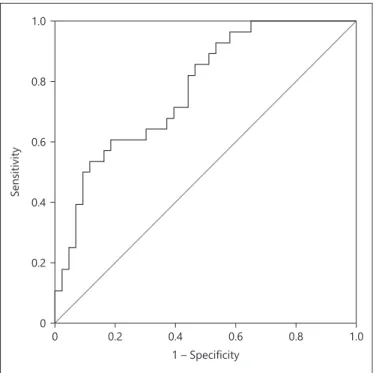

en-dometrial cancer was evaluated by receiver operating characteris-tics (ROC) analyses, namely, by calculating the area under the curve to determine the maximum sum of the sensitivity and spec-ificity for the test. Multinominal Logistic Regression analysis was used to determine the best predictor(s) for discriminating the hy-perplasia and cancer groups from the control group were analyzed by. Any variable whose univariable test had a p value less than 0.05 was accepted as a candidate for the multivariable model along with all variables of known clinical importance. ORs and 95% CIs for each independent variable were also calculated. A p value less than 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

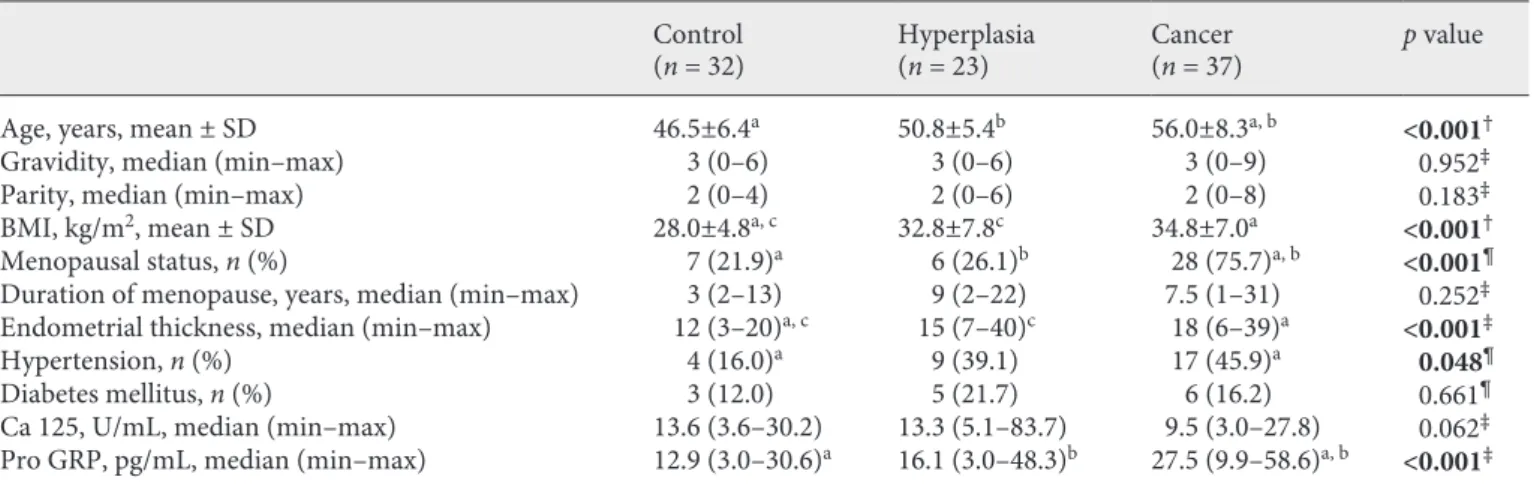

The demographic data, medical history, and clinical features of the 3 groups are summarized in Table 1. EA patients had significantly higher median BUN levels com-pared with the hyperplasia and control groups (EA group: median 13 mg/dL [8–33 mg/dL], hyperplasia group: me-dian 11 mg/dL [5–20 mg/dL], control group: meme-dian 10 mg/dL [6–22 mg/dL]; p < 0.001), whereas the median creatinine levels did not differ between groups (EA group: median 0.70 mg/dL [0.60–0.90 mg/dL], hyperplasia group: median 0.70 mg/dL [0.58–0.90 mg/dL], control group: median 0.70 mg/dL [0.60–0.86 mg/dL]; p = 0.559).

The median serum ProGRP levels were significantly higher in the cancer group compared to the levels in both the hyperplasia and control groups; but there was no sig-nificant difference between the control and hyperplasia groups (p > 0.05; Fig. 1). The number of patients with hy-perplasia was too low to analyze the CA125 and ProGRP levels in cases with or without atypia.

According to the Spearman rank correlation analyses, among the parameters of age, gravidity, parity, BMI, menopausal duration, endometrial thickness, BUN, cre-atinine, and Ca125 levels, only age and endometrial thick-ness were positively correlated with ProGRP levels (r = 0.322, p = 0.006 and; r = 0.269, p = 0.023 respectively).

The predictive value of the measured parameters on the risk of developing endometrial hyperplasia and can-cer was examined by multivariable analysis, using the variables that might be associated with endometrial can-cer. The results of the ROC analysis of the final logistic regression model containing the statistically significant continuous variables are given in Table 2. With regards to cancer, ProGRP, BMI, endometrial thickness, and

0 10 20 30 40 50 60 Pr o-GRP , pg/mL

Control group Endometrial

hyperplasia group groupEA

Fig. 1. Serum ProGRP values in endometrial cancer, endometrial

hyperplasia, and control groups. EA, endometrial adenocarcinomas.

Table 1. Demographic parameters, medical history, and clinical features in groups

Control

(n = 32) Hyperplasia(n = 23) Cancer (n = 37) p value

Age, years, mean ± SD 46.5±6.4a 50.8±5.4b 56.0±8.3a, b <0.001†

Gravidity, median (min–max) 3 (0–6) 3 (0–6) 3 (0–9) 0.952‡

Parity, median (min–max) 2 (0–4) 2 (0–6) 2 (0–8) 0.183‡

BMI, kg/m2, mean ± SD 28.0±4.8a, c 32.8±7.8c 34.8±7.0a <0.001†

Menopausal status, n (%) 7 (21.9)a 6 (26.1)b 28 (75.7)a, b <0.001¶

Duration of menopause, years, median (min–max) 3 (2–13) 9 (2–22) 7.5 (1–31) 0.252‡

Endometrial thickness, median (min–max) 12 (3–20)a, c 15 (7–40)c 18 (6–39)a <0.001‡

Hypertension, n (%) 4 (16.0)a 9 (39.1) 17 (45.9)a 0.048¶

Diabetes mellitus, n (%) 3 (12.0) 5 (21.7) 6 (16.2) 0.661¶

Ca 125, U/mL, median (min–max) 13.6 (3.6–30.2) 13.3 (5.1–83.7) 9.5 (3.0–27.8) 0.062‡

Pro GRP, pg/mL, median (min–max) 12.9 (3.0–30.6)a 16.1 (3.0–48.3)b 27.5 (9.9–58.6)a, b <0.001‡ † One-way ANOVA, ‡ Kruskal Wallis test, ¶ Pearson’s chi-square test, a Control vs. cancer (p < 0.05), b Hyperplasia vs. cancer (p <

menopausal status were the strongest predictors, after ad-justing for other variables (Table 2). The predictive accu-racy of ProGRP as a marker for EA was found by ROC curve analyses (AUC 0.775, 95% CI 0.667–0.882, p < 0.001; Fig. 2). A threshold of 20.81 pg/mL had 60.7% sen-sitivity, 81.4% specificity, a positive predictive value 68%, and a negative predictive value of 76.1%. Regardless of age, ProGRP was found to be predictive of EA of the en-dometrium with an accuracy of 73.2%.

Staging was performed surgically in the endometrial cancer patients. Twenty-six patients had stage IA cancer, 8 had stage IB cancer, and 3 had stage II cancer. Only 6 patients showed lymphovascular invasion in their patho-logical reports, but none had metastatic pelvic or para-aortic lymph nodes. Neither CA125 nor ProGRP was sig-nificantly correlated with stage, myometrial invasion, or lymphovascular invasion (CA125: p = 0.481, p = 0.462,

p = 0.827, respectively; ProGRP: p = 0.132, p = 0.345, p >

0.999 respectively).

Discussion

To the best of our knowledge, for the first time in the literature, we documented significantly elevated levels of serum ProGRP in EA patients. The results indicate that ProGRP is highly predictive of early stage EA of the en-dometrium. The diagnostic sensitivity and specificity of serum ProGRP obtained from this study imply that ProGRP levels may be a potential tumor marker for type 1 endometrial cancer.

Because GRP is a potent mitogen for various tumor types including pancreatic, small cell lung, prostate, renal, breast, and colon cancers its utility in oncology has been investigated [10]. The association of proGRP with neuro-endocrine malignancies such as small cell lung cancer, medullary thyroid cancer, and prostate cancer has been

Table 2. The results of multinominal logistic regression analysis

OR 95% CI Wald p value lower upper Hyperplasia Age, years 1.185 0.960 1.463 2.489 0.115 BMI, kg/m2 1.179 0.970 1.434 2.731 0.098 Endometrial thickness 1.417 1.058 1.898 5.473 0.019 ProGRP 1.152 1.008 1.316 4.307 0.038 Post-menopause 0.648 0.028 14.831 0.074 0.786 Hypertension 0.520 0.043 6.318 0.263 0.608 Cancer Age, years 1.101 0.879 1.379 0.706 0.401 BMI, kg/m2 1.318 1.043 1.667 5.330 0.021 Endometrial thickness 1.408 1.046 1.894 5.101 0.024 ProGRP 1.304 1.105 1.538 9.876 0.002 Post-menopause 39.782 1.102 1,436.347 4.052 0.044 Hypertension 0.345 0.027 4.456 0.664 0.415 1.0 0.8 0.6 0.4 0.2 0 0 0.2 0.4 0.6 0.8 1.0 Sensitivity 1 – Specificity

Fig. 2. Receiver operating characteristics (ROC) curve showing the

diagnostic performance of serum proGRP in predicting endome-trial adenocarcinoma.

shown before [12]. In gynecology, only one study inves-tigated ProGRP in ovarian and cervical malignancies (n = 15) and the reported mean levels were 18 pg/mL [13]. In our study, the median value of ProGRP was 27.5 pg/mL in EA and the calculated cutoff value was 20.81 pg/mL for diagnosis of EA. The observed trend of gradually increas-ing levels of ProGRP in endometrial hyperplasia, which is a precursor of EA, appears to support our assertion. ProGRP did increase as endometrial thickness increased. In sheep, the synthesis, storage, and secretion of GRP are differentially affected by estrogen and progesterone [14]. The regulation of GRP appears to be tissue-specific and can be influenced by the presence of ovarian steroids [14]. Although no previous data about the regulation of GRP in the human endometrium expression exists, long-term unopposed estrogen altering the endometrial mileu might have caused the high ProGRP values we observed in pa-tients with EA. Moreover, neuroendocrine cells have been identified in endometrial EAs [15]. The presence of neuroendocrine cells in these tumors is another explana-tion for elevated levels of ProGRP in EA. In addiexplana-tion, in our study, myometrial invasion was observed in 77% of the EA cases (<50% myometrial invasion in 19 cases and >50% myometrial invasion in 9 cases). GRP receptors have also been found to be expressed in human myome-trium that exist outside of the endometrial glands [9]. In EA patients, the high levels of ProGRP might be due to increased secretion and expression from myometrium, as well.

According to the results from this study, even if ProGRP is not discriminating enough for use in diagnos-ing endometrial hyperplasia, it appears to be valuable for diagnosing EA. Every one unit increase in proGRP is as-sociated with a 1.304 increase in the risk of endometrial cancer. GRP acts as a potent mitogen for cancer cells of diverse origin, in both in vitro and in animal models of carcinogenesis [16]. Overexpression of GRP and its re-ceptors has been demonstrated at both the mRNA and protein levels in many types of tumors including lung, prostate, breast, stomach, pancreas, and colon [16]. How-ever, the expression of GRP and its receptors in endome-trial cancer and the possible use for prediction of lymph node status preoperatively is yet to be elucidated. Even though the number of patients is insufficient to interpret this topic, it was found in this study that ProGRP level does not correlate with lymphovascular space invasion. Further studies are needed to confirm this issue.

Numerous authors have investigated the diagnostic value of different cancer antigens in EA, such as cancer antigen 15–3 (CA15–3), carcinoembryonic antigen,

CA125, carbohydrate antigen 19–9 (CA19–9), serum am-yloid A, and human epididymis secretory protein 4 (HE4) [17]. No significant difference in CA125 levels was found in patients with endometrial cancer compared with healthy controls [17]. Consistent with previous data, we found no significant difference in CA125 levels between the control group, hyperplasia group, and EA group. The significance of CA125 levels in the evaluation of endome-trium cancer is essentially restricted to the advanced stage of the disease [17, 18]. On the other hand, the results from this study indicate that ProGRP has high specificity (81.4%) for detecting EA. Therefore, ProGRP currently seems to be a promising marker for EA. However, it may also be elevated in other cancers, including SCLC and in benign conditions, such as in patients with high creatinine levels [19]. ProGRP testing is not perfectly sensitive for detecting EA because not every patient with EA will have elevated levels of ProGRP in serum.Our results indicate that 60% of all EA patients are positive for ProGRP, where-as remaining patients do not express this marker at all.

In healthy individuals, 95% of ProGRP serum samples showed values of 37.7 pg/mL or less (ARCTITECT ProGRP assay) [20]. Our study used the same assay in healthy women (mean age 46), and the mean ProGRP levels ranged between 3.0 and 30.0 pg/mL, with a median level of 12.9 pg/mL. The expected values are affected by the collection conditions and it is recommended that each laboratory establish its own expected reference range for the population of interest. Limitations of this study in-clude the high unstability of ProGRP and its variance in plasma and serum levels. The increased age of EA patients compared with controls and the positive correlation of pro-GRP with age might prevent us from drawing strong conclusions. Thus, similar age interval and menopausal status would optimize the results.

Serum ProGRP has good diagnostic sensitivity and specificity for EA. Further studies are needed to establish appropriate reference values for the healthy female popu-lation, for both plasma and serum levels as well as the prognostic importance of Pro-GRP. Large population-based studies might support the validity of using ProGRP in the diagnosis of EAs.

Acknowledgment

The authors wish to thank all patients for their participation in this study and all personnel at the obstetrics and gynecology de-partment of 2 hospitals for their enthusiastic contribution. This study received no financial support and the authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

1 Ferlay J, Soerjomataram I, Dikshit R, Eser S, Mathers C, Rebelo M, Parkin DM, Forman D, Bray F: Cancer incidence and mortality worldwide: sources, methods and major pat-terns in GLOBOCAN 2012. Int J Cancer 2015; 136:359–386.

2 Morice P, Leary A, Creutzberg C, Abu-Rus-tum N, Darai E: Endometrial cancer. Lancet 2016;387:1094–1108.

3 Bokhman JV: Two pathogenetic types of en-dometrial carcinoma. Gynecol Oncol 1983; 15:10–17.

4 Song G, Satterfield MC, Kim J, Bazer FW, Spencer TE: Gastrin-releasing peptide (GRP) in the ovine uterus: Regulation by interferon tau and progesterone. Biol Reprod 2008;79: 376–386.

5 Molina R, Filella X, Auge JM: ProGRP: a new biomarker for small cell lung cancer. Clin Bio-chem 2004;37:505–511.

6 Nisman B, Biran H, Ramu N, Heching N, Barak V, Peretz T: The diagnostic and prog-nostic value of ProGRP in lung cancer. Anti-cancer Res 2009;29:4827–4832.

7 Kim HR, Oh IJ, Shin MG, Park JS, Choi HJ, Ban HJ, Kim KS, Kim YC, Shin JH, Ryang DW, Suh SP: Plasma proGRP concentration is sensitive and specific for discriminating small cell lung cancer from nonmalignant conditions or non-small cell lung cancer. J Korean Med Sci 2011;26:625–630.

8 Whitley JC, Giraud AS, Shulkes A: Expression of gastrin-releasing peptide (GRP) and GRP receptors in the pregnant human uterus at term. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 1996;81:3944– 3950.

9 Fleischmann A, Waser B, Gebbers JO, Reubi JC: Gastrin-releasing peptide receptors in normal and neoplastic human uterus: in-volvement of multiple tissue compartments. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2005;90:4722–4729. 10 Dumesny C, Patel O, Lachal S, Giraud AS,

Baldwin GS, Shulkes A: Synthesis, expression and biological activity of the prohormone for gastrin releasing peptide (ProGRP). Endocri-nology 2006;147:502–509.

11 Pecorelli S: Revised FIGO staging for carci-noma of the vulva, cervix, and endometrium. Int J Gynaecol Obstet 2009;105:103–104. 12 Preston SR, Miller GV, Primrose JN:

Bombe-sin-like peptides and cancer. Crit Rev Oncol Hematol 1996;23:225–238.

13 Molina R, Auge JM, Filella X, Vinolas N, Ali-carte J, Domingo JM, Ballesta AM: Pro-gas-trin-releasing Peptide (ProGRP) in patients with benign or malignant diseases: compari-son with CEA, SCC, CYFRA 21–1 and NSE in patients with lung cancer. Anticancer Res 2005;25:1773–1778.

14 Whitley JC, Giraud AS, Mahoney AO, Clarke IJ, Shulkes A: Tissue-specific regulation of gastrin-releasing peptide synthesis, storage

and secretion by oestrogen and progesterone. J Endocrinol 2000;166:649–658.

15 Chun YK: Neuroendocrine tumors of the fe-male reproductive tract: a literature review. J Pathol Transl Med 2015;49:450–461. 16 Patel O, Shulkes A, Baldwin GS:

Gastrin-re-leasing peptide and cancer. Biochim Biophys Acta 2006;1766:23–41.

17 Omer B, Genc S, Takmaz O, Dirican A, Kusku-Kiraz Z, Berkman S, Gurdol F: The diagnostic role of huma epididymis protein 4 and serum amyloid-A in early stage endometrial cancer patients. Tumor Biol 2013;34:2645–2650. 18 Sadowski EA, Robbins JB, Guite K,

Patel-Lippmann K, Munoz del Rio A, Kushner DM, Al-Niaimi A: Preoperative pelvic MRI and se-rum cancer antigen-125: selecting women with grade I endometrial cancer for lymphad-enectomy. AJR Am J Roentgenol 2015;205: 556–564.

19 Kamata K, Uchida M, Takeuchi Y, Takahashi E, Sato N, Miyake Y, Okubo M, Kodama T, Yamaguchi K: Increased serum concentra-tions of pro-gastrin-releasing peptide in pa-tients with renal dysfunction. Nephrol Dial Transplant 1996;11:1267–1270.

20 Stieber P, Molina R, Dowell B, Doss R, Yo-shimura T, Blankenburg F, Hofmann K, Scheuer C, Hogg A, Hatz R: Clinical evalua-tion of the ARCHITECT ProGRP assay. J Thoracic Oncology 2008;3:S236.