www.interlawandfs.org

MALPRACTICE TENDENCY IN PATIENT CARE PRACTICES ISSN: 2572-5408 (Print)

ISSN: 2572-5416 (Online)

Seval Canpolat*, Serap Torun**

*RN, Çukurova Üniversity, Balcalı Hospital, Adana/Turkey e-mail: sevalbozkurt01@gmail.com

** Assist.Prof. Dr. Cukurova University, Faculty Of Health Science, Nursing Department, Department Of Nursing Management, Adana/Turkey

e-mail: torunserap@gmail.com Corresponding Author: Serap Torun e-mail: torunserap@gmail.com ABSTRACT

Objective: The aim in this study is to determine probability of malpractice among attending healthcare professionals.

Background: Malpractice is a significant problem with potentially serious consequences, even death, and which is commonly encountered in healthcare practices.

Material and Method: The study sample comprised 560 healthcare workers from three different hospitals. The Scale of Malpractice Tendency (SMT) validated by Ozata and Altunkan (2010) and a Personal Data Form were used in the study, and the SPSS for Windows 20. 0 software package was used for the statistical analysis. In determining the parameters affecting the subscale scores of the SMT, a t-test or a one analysis of variance were used in independent groups. The level of statistical significance was set as 0.05 in all analyses.

Results: The mean score was 87.22±4.23 in the medication and transfusion subscale, 57.69±3.43 in the nosocomial infections subscale, 42.71±3.24 in the patient follow-up and material safety subscale, 23.99±1.78 in the falls subscale and 24.36±1.38 in the communication subscale. The total mean scale score was 235.97±14.06.

Conclusion: The probability of malpractice among the participants was low. The mean total sub-scale score of the participants aged 40 years and older was found to be higher, while the likelihood of malpractice was lower than in the other age groups.

Keywords: tendency, patient care, patient safety, healthcare professional, medical malpractice.

This study is a graduate thesis of Seval Canpolat. This project, TYL-2015-5273, was supported by Ç.U. Scientific Research Projects.

I. INTRODUCTION

Medical malpractice in the course of patient care that occurs as a result of the recommendations and/or interventions of healthcare professionals that are authorized to provide healthcare services and to be involved in the treatment of patients in all stages of the healthcare system, in all institutions, and every stage of the treatment process, includes all conditions, from delays in recovery by affecting the usual disease course, to death. 1,2,3

Malpractice in the practices of medicine and law frequently come the agenda due to the demands of people to receive high quality and safe service. Accordingly, there is growing interest among some professional groups working in the field of law related to the financial aspects of medical malpractices. The number of patients exposed to malpractice worldwide started to be recorded in the 1990s.4 In a conference organized by the World Health Organization (WHO) in Geneva in 2007, further research was recommended into patient safety, based on the fact that an estimated 10 million people around the world die or become disabled per year due to preventable medical errors. Although studies into safe patient care have increased worldwide in line with this recommendation, the rate of medical errors has not decreased as predicted.5 According to Hakeri, 1,060 files were submitted to departments of forensic medicine following a death in 2013, and 100 physicians were found to be at fault, indicating the 100 out of 1000 physicians involved in malpractice lawsuits were found to be at fault in Turkey. The reason for this is that although files are brought against the physician in the event of patient death, it is normally organizational failure that is to blame.6

Intention and negligence are important factors in the occurrence of medical errors. Intention is defined as acting deliberately, despite knowing that the action is against the rules; while negligence refers to unintentional medical errors that result from a lack of sufficient attention while taking measures.7 Medical errors generally occur when the necessary works are not carried out in accordance with the established standards (negligence), or doing what must not be done (carelessness).8 In medical malpractice cases that occur due to negligence, the service provided by the healthcare professional is below acceptable standards. There are certain legal conditions to consider when defining a medical outcome as malpractice, such as the presence of an established relationship, being against the law, the presence of an injury, the presence of medical error, and the presence of a causal relationship. 9

There are three main sources of medical error: human-derived, organizational and technical. Human-derived causes can result from insufficient education and fatigue.10, and failure to take precautions, insufficient communication, carelessness, inadequate time given, incorrect decisions, lack of reasoning and disputatious personality.11 Human-derived errors can be further classified as medication errors, surgical errors and diagnostic errors.12 Errors related to negligence (failure to take the correct

way) are common human-derived errors.13 Organizational errors can relate to the physical condition of the workplace, the administrative structure, the policies followed, the improper allocation of personnel and failure to resolve problems. Finally, technical errors refer to those based on the failure or absence of a device .14,15

Malpractice is the main aspect of patient safety emphasized by the International Council of Nurses (ICN).16 Medical errors in nursing practice include inattentiveness, failure to take precautions, lack or insufficiency of professional experience, carelessness, and failure to follow orders and instructions.17 Conditions that involve nurses in legal problems include violation of patient safety and negligence, errors in the administration of drugs and blood transfusions, errors or failures in the use of medical devices, miscommunication, missing records, nonadherence to existing protocols, hospital infections, patient falls and bed sores. 18,12,19

Medication errors, which can be detrimental to patient safety and which increase morbidity-mortality and treatment costs, are significant health problems worldwide.20,21,22 According to the United States National Coordinating Council for Medication Error Reporting and Prevention 23, “a medication error is any preventable event that may cause or lead to inappropriate medication use or patient harm while the medication is in the control of the health care professional, patient, or consumer”.23 In a study by Milch et al. (2006) in which reports of medical errors and side effects in 2006 were examined, 33 percent of the reported errors were related to medication, and were reported by the nurses.24 Nonadherence to basic rules has been suggested as the most common cause of error during the preparation and administration of medication leading to lawsuits.18,25. In a review of 33 studies related to medication errors, Wright (2010) concluded that more attention must be paid to the preparation and administration of medication .26

Hospital infections, as a common occurrence, can be spread by healthcare professionals who are constantly in close contact with patients and are responsible for their care, but can also result from an excessive number of patients in a hospital room, high mobility within the hospital, and serious and complex medical interventions.27,28

Falls are medical errors that frequently lead to lawsuits against nurses. In the United States, falls account for 30 percent of non-fatal injuries among patients aged 65 years and older.29, 30 Being aware of the medical history of the patient and taking appropriate precautions after determining the risk of fall would prevent many of these cases.31

Another type of medical error relates to patient follow-up and material safety. In many developed countries, the insufficiency of patient follow-up is the most common cause of malpractice lawsuits.32 Accurate and timely recording, effective communication, and appropriate equipment and diagnostic-therapeutic procedures can decrease the probability of errors. 33,34,35,36

healthcare services. The interaction between the patient and the healthcare professional in the diagnosis and treatment processes is an important factor affecting patient satisfaction and the quality of service provided.37

According to the “Regulation on Ensuring Patient and Employee Safety” in Turkey, healthcare institutions are responsible for the safety of the service provider and the recipient. Upon receipt of a complaint, the relevant units are notified after a preliminary evaluation by the patient rights unit.38 All errors must be reported to allow preventable errors to be precluded rather than imposing penalties on the responsible persons.39 In a study by Lawton and Parker (2002) examining the attitudes of healthcare professionals towards the reporting of errors, physicians in particular were found to be reluctant to report medical errors due to occupational autonomy 40, while in a study by Gökdoğan and Yorgun (2010), it was found that most nurses feel comfortable about reporting errors.41 Karaca and Arslan (2013) emphasized the importance of establishing an efficient error reporting system and controlling patient safety in the prevention of medical errors. 42

The present study was conducted to evaluate the likelihood of attending healthcare professionals who are directly responsible for patient care (nurses, midwives, emergency medical technicians) to make medical errors.

II. MATERIAL AND METHOD

The study was approved by the ethics committee (decree number 2015.44/29, dated July 3, 2015) and written permission was received from the hospitals in which the study was carried out. Data was collected between September 2015 and February 2016. The participants read the informed consent section of the data collection form and their consent was obtained.

2.1. Data and sample

The study population comprised 1,780 healthcare professionals who provide healthcare services in three training and research hospitals in the province of Adana, Turkey. The final study sample was composed of 560 subjects, including 499 nurses, 34 midwives, nine emergency medicine technicians and 18 medical assistants.

The study data was collected through face-to-face interviews, using the Scale of Malpractice Tendency (SMT) validated by Ozata and Altunkan (2010) and the Personal Data Form developed by the researchers for data collection.

The responses to each of the 49 items on the scale were rated on a 5-point Likert-type scale , with the participants being asked to mark the most appropriate option according to their preferences,

49–245 point range. The higher the total score in the scale, the lower the tendency to make medical errors.

2.2. Statistical analysis

The SPSS 20.0 software package, Kolmogrov Smirnov test, t test, one-way analysis of variance, Pearson’s correlation coefficient, Scheffe or Tamhane tests were used for the statistical analysis of the data. A linear regression analysis was made performed to determine the characteristics affecting the SMT subscale scores the most. The level of statistical significance was set as 0.05 in all analyses.

The Cronbach’s alpha internal consistency coefficient of the scale was calculated at 0.84, and the mean total score of the scale was found to be 235.97±14.06.The mean subscale scores are presented in TableI.

Table I. Numerical values for SMT

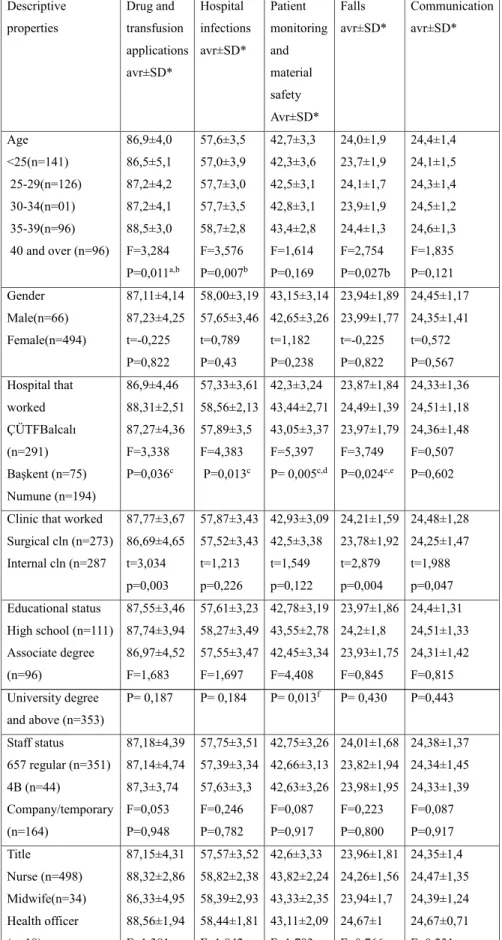

Of the study participants, 24 percent have provided patient care for 6–10 years, 45 percent have worked at the same institution for 1–5 years, 52 percent have worked in the same unit for 1–5 years, 47 percent work fewer than 45 hours per week, and 51 percent work from 1–5 nightshifts per month. Of the participants, 39 percent were observed to be indecisive when asked about job satisfaction. Of the study participants, 79 percent reported that they were healthy and 28 percent slept for around six hours per day. The medication administration and transfusions, falls and communications subscale scores were observed to vary from clinic to clinic (p<0.05), while the scores in these three subscales were higher among the healthcare professionals working in surgical units. The mean total scores in all subscales were higher in healthcare professionals aged 40 years and older when compared to the other age groups (Table II).

over p<0.05, b25-29: between 25-29 years- comparision for 40 years and over p<0.05, comparision for cÇÜTF Balcalı Hospital-Başkent University Hospital p<0.05, comparision for dÇÜTF Balcalı Hospital – Numune Hospital p<0.05, comparision for eBaşkent Hospital-Numune Hospital p<0.05,comparision for Assocation-University or above graduate p<0.05.

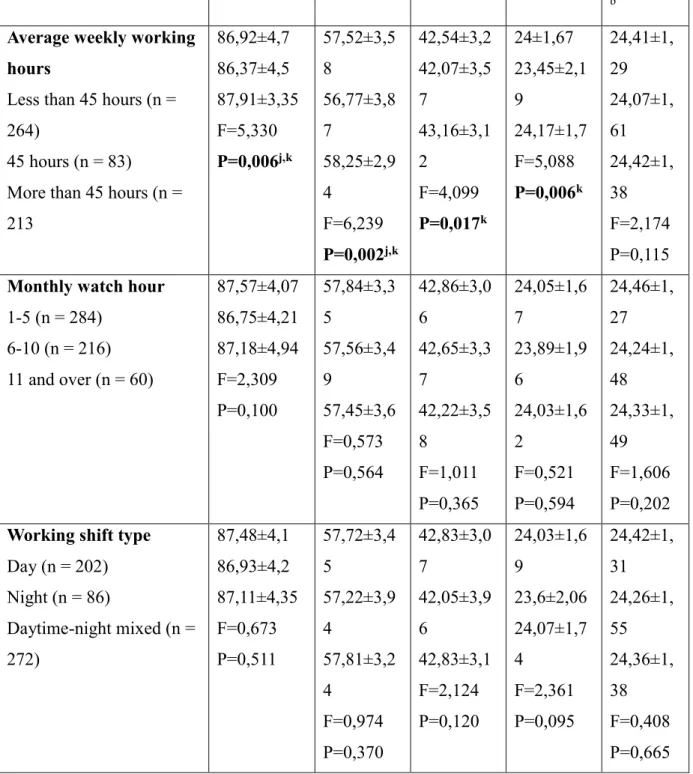

In an evaluation of the relationship between the sociodemographic characteristics of the study participants and the mean SMT subscale scores, all subscale scores, aside from the communication subscale, varied from institution to institution (Table III).

Table III. Assessment of Relationship Between Vocational Qualifications of Healthcare Workers and SMT Subscale Score Averages (Continued)

* Avr: Avarege, SD: Standard Deviation.

a Comparision for 1 years less - 21 years and over for p <0.05,

b Comparision for1-5 years - 21 years and over for p <0.05 cp <0.05 comparision for 6-10 years - 21 years and over, dp <0.05 comparison for less than d1 year and 11-15 years, ep <0.05 comparison for 1-5 years and 11-15 years,

fp <0.05 comparison for 6-10 years - 11-15 years,

gp <0.05 comparison for less than 1 years and 16-20 years, hp <0.05 comparison for 1-5 years - 16-20 years,

i p<0.05 comparison for 6-10 years and 16-20 years, a-f : a,b,c,d,e,f a-i : a,b,c,d,e,f,g,h,i jp <0.05 comparison for over 45 hours and less than 45 hours

kp < 0.05 45 for comparison 45 hours and over 45 hours lp <0.05, for comparison between 1-5 patients 11-15 patients m p <0.05 for comparison 11-15 patients - 16-20 patients

n p <0.05 for comparison between I'm not satisfied at all - very satisfied

o p <0.05 comparison forI am not pleased-very satisfied with the comparison for p <0.05, p p <0.05 comparison for Unstable - very satisfied,

rp <0.05comparison for inferiority - satisfaction

IV. DISCUSSION

In the present study, 63 percent of the participants had graduate and postgraduate degrees, which supports the idea that malpractice tendencies decrease with increasing educational level, as suggested in the study by Anezz (2006).

The scores in the medication and transfusion subscale (87.22±4.23) show that the participants had a low malpractice tendency. The mean score in this subscale was found to be 86.56±3.54 in the study by Dikmen et al. (2014), compared to 86.14±4.77 in the study by Alan and Khorshid (2016). When compared to these results, the participants in the present study had a lower tendency to malpractice.43,44

The participants’ mean scores in the “I make it sure that I administer the correct medication to the patient” and “I pay attention to administering the drug to the correct site during IV, IM and SC injections” subscale expressions were found to be 4.93±0.28, indicating the particular attention paid in these fields. Dikmen et al.(2014) also reported the highest scores in this expression (4.98±0.13).43 This finding can be attributed to the attention paid to learning and reinforcement during the process of education in the administration of drugs. The lowest score (4.60) in the study was noted in the expression of “I know about the side effects of the drugs, and administer accordingly”. In the study by Çırpı et al. (2009), the mean score in this subscale expression was found to be 4.44±0.63.45 The

fact that the lowest mean score was identified for this expression in the present study indicates the lower tendency of the participants to malpractice when compared to those in similar studies. Reid et al. (2009) reported that the rate of side effects following drug administration in their study was 13.3 percent, and 0.4 percent of these side effects resulted in death.46 Aygin et al. (2002) determined that the majority of surgical nurses lacked sufficient knowledge of premedication drugs and their side effects. Such a lack of knowledge on the side effects of drugs and failure to monitor the effects of drug after administration complicate the prevention of conditions that may harm the patient, and may even lead to death.47 The role of nurses in the administration of drugs is not solely administering the drug as prescribed. The professional responsibility attributed to drug administration also involves having sufficient knowledge of the relevant drug, errorless/safe administration, monitoring the physiological response to the drug, interpretation and providing education to the patient and their relatives about drug therapy. Gülçin et al. (2016) found that the lowest scores of nurses in the “Medication Administration and Transfusion” subscale were noted in the expression “I follow the patient sufficiently after drug administration”.48 Young et al. (2008) found that “administration at wrong time” ranked first (70.8%) among all other medication errors.49 In our study, it is reasonable to suggest that the participants adhered to the drug confirmation system.

In our study, the mean scores in the subscales were highest among the participants aged 40 years and older. Üstüner et al.(2016) found a significant relationship between drug administration errors of nurses and age, educational level, work experience, number of cared patients and working conditions (day work/night shifts).50 Tang et al. (2007) reported that medication errors involving nurses mostly occur among personnel that have recently started working in the profession. It is considered that medical errors decrease with the increasing number of years worked in the occupation, as occupational knowledge and skills develop as experience is accumulated.

Factors associated with medical errors that have been reported in literature include interruptions during the administration of medication, lack of sufficient knowledge and skills, failure to use the confirmation system, excessive workloads, problems encountered in the continuity of care and the lack of sufficient communication between the members of the healthcare team.25,51,52 Al-Shara (2011) observed that the majority of medication errors can be traced to excessive workload.53 Ersun et al. (2013) reported that the most common medical errors among nurses relate to the administration of medication,54 while Ertem et al. (2009) reported that medication errors decreased as the number of nurses working at the clinics increased.12 The conscious administration of medications in the light of accurate knowledge minimizes the probability of medical errors, while also increasing treatment success substantially.55

The mean score in the “Hospital Infections” subscale of the SMT was calculated as 57.69±3.43, while the mean score in this subscale was calculated as 57.29±4.33 by Alan and

Khorshid (2016), and as 57.67±2.79 by Dikmen and Yorgun.43,44 It is reasonable to suggest that the participants had a low probability of malpractice in this subscale. In the evaluation of this subscale, the highest score (4.88) was noted in the expressions “I pay attention to not to contaminate infused fluids during preparation and administration” and “I avoid the use of materials if safety concerns arise”. Although an indwelling catheter must be left in place for a maximum of 96 hours due to the risk of catheter infection and thrombophlebitis 55, the mean score was 4.71 for the expression “I pay attention to the 72–96-hour IV catheterization time.” Although this rate is low, it cannot be suggested that the associated likelihood of malpractice would be high.

The mean score in the “Patient Follow-up and Material Safety” subscale was 42.71±3.24, and the mean score in this subscale was higher among undergraduate (n=96) participants when compared to graduate and/or postgraduate (n=353) participants. This finding can be attributed to the fact that the undergraduate participants were those who were aged 40 years and older who had more job experience. The mean score in this subscale was reported to be 39.98±3.91 by Dikmen et al. (2014) and 40.70±4.24 by Alan and Khorshid.43,44 The mean malpractice scores of the participants in this subscale was found to be lower than those reported in other studies.

The mean score in the “Falls” subscale was found to be 23.99±1.78, with the highest scores in this subscale being noted in the expressions “I pay attention to the presence of grab bars/hand guards and guards at the edges of the patients’ beds” and “I ensure that precautions are taken during the transportation of the patient.” The lowest score (4.49±0.73) in the study by Dikmen et al. (2014) was noted in the expression “I provide information to the patient and his/her relatives about the causes of falls, and the measures that can be taken”,43 and the same expression also received the lowest score (4.74) in the present study. Preventing the access of a patient’s relatives into certain clinics may be associated with this result.

The mean score in the “Communication” subscale of the SMT was calculated as 24.36±1.38, while the mean score in the same subscale was found to be 23.00±2.17 by Dikmen and Yorgun (2014) and 23.20±2.17 by Alan and Khorshid (2016), with similar results reported by Telli (2013). 43,44, 56 Meginniss et al. (2012) reported that 60–80 percent of more than 40,000 medical errors that occurred in the United States in 2009 were actually a result of ineffective communication and insufficient team work.57 In our study, the mean malpractice tendency subscale score was found to be higher in the communication subscale when compared to other studies. Accordingly, it can be said that the participants experience no problems relating to communication.

The mean score in the “Communication” subscale increased with increasing number of years worked in the occupation, and job experience is also found to increase, and accordingly, the likelihood of malpractice is found to decrease, with the increasing number of years worked (p<0.05). The mean scores in all subscales, aside from in the “Patient Follow-up and Material Safety”

subscale, varied according to the total duration of time worked in the institution or unit. Şahin et al.(2015) found that the scores in all subscales, aside from the “Patient Follow-up and Material Safety” subscale, varied according to the total duration of time worked in the institution or unit, which supports the current findings (p<0.05).58

The present study found no change in the SMT subscale scores of the participating healthcare professionals related to shift patterns and the number of nightshifts per month. The mean scores of participating healthcare professionals in all SMT subscales, aside from in the “Communication” subscale, varied in line with the mean hours worked per week (p<0.05).

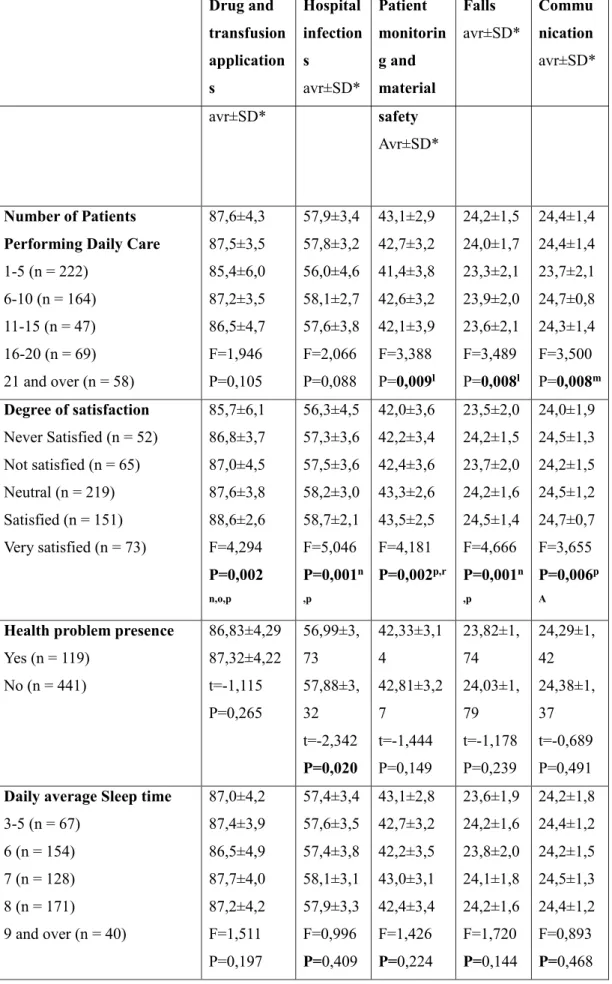

The mean scores of the participating healthcare professionals in all subscales, aside from the “Medication Administration and Transfusion” and “Hospital Infections” subscales, varied according to the daily number of patients provided with care. The mean scores in patient follow-up and material safety and falls subscales were lower among healthcare professionals providing care to 11–15 patients per day when compared to those providing care to 1–5 patients per day. These results are consistent with those reported by Alan and Khorshid (2016) (Alan 2016), and this finding can be attributed to the distinct needs of intensive care unit patients and those admitted to the clinic. In most hospitals, junior nurses that have recently started working are assigned to tasks in the intensive care unit. In the present study, the healthcare professionals that provide care to fewer patients (1–5) are those who work in the internal medicine and surgical intensive care units, and who have less than a year’s experience. It is reasonable to suggest that these participants are in possession of contemporary occupational knowledge, and act more cautiously with the fear of medical error, and this decreases their tendency to malpractice. It was observed that healthcare professional providing care to 11–15 patients per day achieved lower scores in the communication subscale when compared to their scores in the other subscales, and there was a significant difference between the groups (p<0.05). Although studies in literature suggest that the likelihood of malpractice increases particularly in the communication subscale with the increasing number of patients cared for per day, the increase in the number of patients in the present study did not increase the tendency to malpractice.43,44

V. CONCLUSION AND RECOMENDATIONS

The present study evaluated the tendency to malpractice among 560 healthcare professionals providing patient care, and found that the participants had a low tendency to make medical errors. Compared to the other age groups, the mean total scale score was found to be higher in participants aged 40 years and older, and their malpractice tendency was lower. Healthcare professionals are involved in fewer malpractice cases due to the increased professional knowledge and skills associated with increased years of employment in the job that comes with increasing age.

Although the present study found a low tendency to malpractice, in-service training on patient safety must be provided to prevent possible malpractice cases. An ethical environment must be created in the institution to ensure the safety of both employees and patients. Considering the fact that burnout or occupational boredom may lead to medical errors, the necessary arrangements in the workplace must be made by managers considering the negative effects of working conditions, workload and stress.

REFERENCES

1.Yıldırım A, Aksu M, Çetin İ, Şahan AG.(2009). Tokat ili merkezinde çalışan hekimlerin tıbbi uygulama hataları ile ilgili bilgi, tutum ve davranışları. Cumhuriyet Tıp Dergisi (31), 356-366. 2.Pronovost PJ, Thompson DA, Holzmueller CG, Lubomski LH, Morlock LL. Defining and Measuring Patient Safety. Critical Care Clinics. 2005; 21:1-19.

3.İntepeler Ş.S., Dursun M.(2012). Tıbbi Hatalar Ve Tıbbi Hata Bildirim Sistemleri. Anadolu

Hemşirelik Ve Sağlık Bilimleri Dergisi, (15), 129-135.

4.Anezz E. (2006). Clinical perspectives on patient safety. In: K Wals, R Boaden (Eds.), Patient Safety Research in to Practice. (1st ed.) London: McGraw Hill Education Open University Press (pp. 9-18).

5.World Health Organization (WHO). (2007). Call For More Researche On Patent Safety, Available from URL, http://www.who.int/mediacentre/ news/releases/ 2007.

6.Hakeri H.(2014). “Hastane Yöneticilerinin Hukuki Sorumluluğu”, I. Sağlık Hukuku Sempozyumu,

İzmir Üniversitesi Hukuk Fakültesi, 15.Mart.2014 İzmir.

7.Özata M, Altunkan H.(2010). Hastanelerde tıbbi hata görülme sıklıkları, tıbbi hata türleri ve tıbbi hata nedenlerinin belirlenmesi: Konya örneği. Tıp Araştırmaları Dergisi, 8(2), 100-111.

8.Hancı İH.(2001). Malpraktis: Tıbbi Girişimler Nedeniyle Hekimin Ceza ve Tazminat Sorumluluğu. I. Baskı. Ankara. Seçkin Yayıncılık.

9.Hanyaloğlu A.(2011). Malpraktis Hekimler İçin Hukuksal Yaklaşım Ve Sigorta Rehberi. Nobel Tıp Kitap Evleri ltd.şti. İstanbul (pp.1-2).

10.Akalın HE. 2007). Klinik araştırmalar ve hasta güvenliği. İyi Klinik Uygulamalar (İKU)

Dergisi.(17),32– 35.

11.Güven R. (2007). Dezenfeksiyon ve sterilizasyon uygulamalarında hasta güvenliği kavramı, 5. Ulusal Sterilizasyon Dezenfeksiyon Kongresi (pp. 411).

12.Ertem G, Oksel E, Akbıyık A. (2009). Hatalı Tıbbi Uygulamalar (Malpraktis) İle İlgili Retrospektif Bir İnceleme. Dirim Tıp Gazetesi 84(1),1-10.

13.Mitchell PH.(2008). Defining Patient Safety and Quality Care. In Hughes RG Ed, Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, RockvillePatient Safety And Quality: An Evidence-Based Handbook For Nurses. First ed. Rockville: AHRQ Publication No.08-0043 (pp.1-5).

14.Top M, Gider Ö, Taş Y, Çimen S. (2008). Hekimlerin Tıbbi Hataya Neden Olan Faktörlere İlişkin Değerlendirmeleri: Kocaeli İlinden Bir Alan Çalışması, Hacettepe Sİ D, 11(2),161-199.

15.Adams JL, Garber S.(2007).Reducing Medical Malpractice By Targeting Physicians Making Medical Malpractice Payments, Journal of Empirical Legal Studies (4),185–222.

16.International Council of Nurses (ICN).(2006).Why is safe staffing importent? Safe Staffing Saves

Lives. International Nurses Day, Information and Action Tool Kit. 1 st ed. Geneva (pp. 9-12).

17.Kocaman G.(2007). Hemşirelik Hizmetlerinde Hasta Güvenliği Ve Liderlik. Hemşirelik Hizmetlerinde Hasta Güvenliği Paneli. İzmir..

18.Demir Zencirci A.(2010). Hemşirelik ve Hatalı Tıbbi Uygulamalar. Hemşirelikte Araştırma

Geliştirme Dergisi 12(1),67-74.

19.Cebeci F, Gürsoy E, Tekingündüz S. (2012). “Hemşirelerin Tıbbi Hata Yapma Eğilimlerinin Belirlenmesi” Anadolu Hemşirelik ve Sağlık Bilimleri Dergisi 15(3),188-196.

20.Akalın HE. (2005). Yoğun Bakım Ünitelerinde Hasta Güvenliği. Yoğun Bakım Dergisi 5(3),141-146.

21.Durmaz A.(2007).Hastaların Hastaneye Yatmadan Önce Kullandıkları İlaçların Kliniğe Kabul Edildikten Sonra Kullanımı İle İlgili İlaç Hatalarının İncelenmesi. Hemşirelik Esasları Yüksek Lisans Tezi, Dokuz Eylül Üniversitesi Sağlık Bilimleri Enstitüsü, İzmir.

22.Sharek PJ, Classen D. (2006). The İncidence Of Adverse Events And Medical Error in Pediatrics, Pediatric Clinics Of North America, (53),1067-1077.

23.NCCMERP (2009), About Medication Errors, www.nccmerp.org/aboutMedErrors.html. Erişim tarihi: 20.04.2017.

24.Milch CE, Salem DN, Pauker SG, Lundquist TG, Kumar S, Chen J. Voluntary (2006). Electronic Reporting Of Medical Errors And Adverse Events An Analysis Of 92,547 Reports From 26 Acute Care Hospitals. Journal of General Internal Medicine 21(2),165–70.

25.Nguyen EE, Connolly PM, Wong V. (2010). Medication Safety Initiative in Reducing Medication Errors. Journal of Nursing Care Quality 25 (3), 224-230.

26.Wright K.(2010). Do Calculation Errors By Nurses Cause Medication Errors In Clinical Practice? A Literature Review. Nurse Education Today 30(1), 85-97.

27.Özçetin M, Saz EP, Karapınar B, Özen S, Aydemir Ş, Vardar F. (2009). Hastane Enfeksiyonları; Sıklığı ve Risk Faktörleri. Çocuk Enfeksiyonları Dergisi (3), 49-53.

28.Postnote (2005) Infection control in healthcare settings,

http://www.parliament.uk/documents/upload/ POSTpn247.pdf Erişim tarihi: 02.01.2016.

29.Koh SSL, Manias E, Hutchinson AM, Donath S, Johnston L.(2008). Nurses’ Perceived Barriers To The Implementation Of A Fall Prevention Clinical Practice Guideline in Singapore Hospitals,

BMC Health Services Research. (8),105-111.

30.Dreschnack Gavin D,Nelson A, Fitzgerald S,Harrow J, Sanchez Anguiano A, Ahmed S, Powwel-Cope G, Wheelchair-Related Falls.(2005). Current Evidence and Directions For İmproved

Quality Care, Journal Of Nursing Care Quality 20(2),119-127.

31.Morse JM.(2008). Preventing Patient Falls: Establihing a Fall Intervention Program, Second Publishing, (pp. 3-5).

32.Safran N.(2004). Hemşirelik ve Ebelikte Malpraktis, İstanbul Üniversitesi Adli Tıp Enstitüsü Sosyal Bilimler Anabilim Dalı, (yayımlanmamış) Doktora Tezi, İstanbul.

33.Mete S, Ulusoy E.(2006). Hemşirelikte İlaç Uygulama Hataları, Hemşirelik Forum Dergisi (pp. 36-41).

34.Aştı T, Acaroğlu R. (2000). Hemşirelikte Sık Karşılaşılan Hatalı Uygulamalar. İ.Ü. HYD.4(2), 22-27.

35.Temel M. (2005). Sağlık Personelini ilgilendiren Önemli Bir Konu: Malpraktis, HFD (pp.84- 90).

36.Çelik F. (2008). Sağlık Kurumlarında iletişim; Hasta ile Sağlık Personeli iletişimi Üzerine Bir Araştırma, Selçuk Üniversitesi Sosyal Bilimler Enstitüsü, (yayımlanmammış)Yüksek Lisans Tezi. 37.Tang FI, Sheu SJ, Yu S, Wei IL, Huey C.(2007). Nurses Relate The Contributing Factors İnvolved İn Medication Errors. Journal Of Clinical Nursing, (16), 447-457.

38.Hasta ve Çalışan Güvenliğinin Sağlanmasına Dair Yönetmelik.

http://www.resmigazete.gov.tr/eskiler/2011/04/20110406-3.htm. Erişim Tarihi: 12.06.2017.

39.Evans SM, Berry JG, Smith BJ. (2006). Attitudes and barriers to incident reporting: A collaborative hospital study. Quality and Safety Health Care 6(15),39-43.

40.Lawton R, Parker D. (2002). Barriers to Incident Reporting in a Healthcare System. Quality and

Safety in Health Care (pp.11-15).

41.Gökdoğan F, Yorgun S. (2010). Sağlık hizmetlerinde hasta güvenliği ve hemşireler. Anadolu

Hemşirelik ve Sağlık Bilimleri Dergisi 13(2),53-59.

42.Karaca A, Arslan H.(2013). Üniversite Hastanesinde Çalışan Hemşirelerde Hasta Güvenliği Kültürünün İncelenmesi. F.N. Hem. Derg. Araştırma Yazısı 21(3), 172-180 (Issn 2147-4923). 43.Dikmen Y, Yorgun S, Yeşilçam N. (2014). Hemşirelerin Tıbbi Hatalara Eğilimlerinin Belirlenmesi. Hacettepe Üniversitesi Hemşirelik Fakültesi Dergisi 44–56.

44.Alan N, Khorsthd L.(2016).Bir Üniversite Hastanesinde Çalışan Hemşirelerin Tıbbi Hataya Eğilim Düzeylerinin Belirlenmesi. Ege Üniversitesi Hemşirelik Fakültesi Dergisi 32(1),1-18. 45.Çırpı F, Doğan Merih Y, Yaşar Kocabey M. (2009). Hasta Güvenliğine Yönelik Hemşirelik Uygulamalarının Ve Hemşirelerin Bu Konudaki Görüşlerinin Belirlenmesi. Maltepe Üniversitesi

Hemşirelik Bilim Ve Sanatı Dergisi 2(3),26-34.

46.Reid M, Estacio R, Albert R. (2009). Injury And Death Associated With incidents Reported To The Patient Safety Net. American Journal of Medical Quality. (24), 520-524.

47.Aygin D, Atasoy I. (2002). Hemşirelerin Premedikasyona İlişkin Bilgi Düzeyleri Ve Uygulamalarının Belirlenmesi. III. Ulusal–I. Uluslararası Ameliyathane Hemşireliği Kongresi. Hemşirelik Forumu. 5(3-4),65-68.

48.Gülçin A, Atabek Armutçu E, Karaman Özlü Z. (2016). Hemşirelerin Tıbbi Hata Eğilim Düzeyleri ve Tıbbi Hata Türleri: Bir Hastane Örneği HSP 3(2),115-122.

49.Young M, Gray SL, Mc Cormick WC. et al.(2008). Types, Prevalence, And Potential Clinical Significance Of Medication Administration Errors In Assisted Living, J Am Geriatr. Soc. 56 (7), 1199–1205.

50.Top ÜF, Çam HH.(2016). Hastanede Çalışan Hemşirelerin İlaç Uygulama Hataları ve Etkileyen Faktörlerin İncelenmesi. TAFPrev Med Bull (15),3.

51.Hellings J, Schrooten W, Klazinga N, Vleugels A.(2007). Challenging patient safety culture: Survey results. Int J Health Care Qual Assur, 20(7),620-632.

52.Taylor C, Lillis C, Lemone P, Lynn P. (2011). Fundamentals of Nursing: The Art and Science of

Nursing Care. 7th ed. Philadelphia (pp. 51-59).

53.Al-Shara M. (2011). Factors contributing to medication errors in Jordan: a nursing perspective. Iranian Journal of Nursing and Midwifery Research. 16(2),158-161.

54.Ersun A, Başbakkal Z, Yardımcı F, Muslu G, Beytut D.(2013). Çocuk hemşirelerinin tıbbi hata yapma eğilimlerinin incelenmesi. Ege Üniversitesi Hemşirelik Fakültesi Dergisi 29(2),33-45. 55.Perry AG, Potter P.(2011). Klinik Uygulama Becerileri ve Yöntemleri, Ed. Atabek Aştı T, Karadağ A. Nobel Kitabevi, Adana, (pp.901).

56.Telli S. (2013). Hemşirelerin Farklı Çalışma Saatlerindeki Durumluk Anksiyeteleri ve Tıbbi Hataya Eğilimlerinin İncelenmesi. Yayınlanmamış Y. L. Tezi. İzmir: Ege Üniversitesi Sağlık Bilimleri Enstitüsü(pp. 44).

57.Meginniss A, Damian F, FalvoF. (2012). “Tıme Out” for Patıent Safety. Journal of Emergency

Nursing 38(1),51-53.

58.Şahin ZA, Özdemir FK. (2015). Hemşirelerin Tıbbi Hata Yapma Eğilimlerinin İncelenmesi.

MALPRACTICE TENDENCY IN PATIENT CARE PRACTICES ISSN: 2572-5408 (Print)

ISSN: 2572-5416 (Online)

Seval Canpolat*, Serap Torun**

*RN, Çukurova Üniversity, Balcalı Hospital, Adana/Turkey e-mail: sevalbozkurt01@gmail.com

** Assist.Prof. Dr. Cukurova University, Faculty Of Health Science, Nursing Department, Department Of Nursing Management, Adana/Turkey

e-mail: torunserap@gmail.com Corresponding Author: Serap Torun e-mail: torunserap@gmail.com ABSTRACT

Objective: The aim in this study is to determine probability of malpractice among attending healthcare professionals.

Background: Malpractice is a significant problem with potentially serious consequences, even death, and which is commonly encountered in healthcare practices.

Material and Method: The study sample comprised 560 healthcare workers from three different hospitals. The Scale of Malpractice Tendency (SMT) validated by Ozata and Altunkan (2010) and a Personal Data Form were used in the study, and the SPSS for Windows 20. 0 software package was used for the statistical analysis. In determining the parameters affecting the subscale scores of the SMT, a t-test or a one analysis of variance were used in independent groups. The level of statistical significance was set as 0.05 in all analyses.

Results: The mean score was 87.22±4.23 in the medication and transfusion subscale, 57.69±3.43 in the nosocomial infections subscale, 42.71±3.24 in the patient follow-up and material safety subscale, 23.99±1.78 in the falls subscale and 24.36±1.38 in the communication subscale. The total mean scale score was 235.97±14.06.

Conclusion: The probability of malpractice among the participants was low. The mean total sub-scale score of the participants aged 40 years and older was found to be higher, while the likelihood of malpractice was lower than in the other age groups.

Keywords: tendency, patient care, patient safety, healthcare professional, medical malpractice.

This study is a graduate thesis of Seval Canpolat. This project, TYL-2015-5273, was supported by Ç.U. Scientific Research Projects.

I. INTRODUCTION

Medical malpractice in the course of patient care that occurs as a result of the recommendations and/or interventions of healthcare professionals that are authorized to provide healthcare services and to be involved in the treatment of patients in all stages of the healthcare system, in all institutions, and every stage of the treatment process, includes all conditions, from delays in recovery by affecting the usual disease course, to death. 1,2,3

Malpractice in the practices of medicine and law frequently come the agenda due to the demands of people to receive high quality and safe service. Accordingly, there is growing interest among some professional groups working in the field of law related to the financial aspects of medical malpractices. The number of patients exposed to malpractice worldwide started to be recorded in the 1990s.4 In a conference organized by the World Health Organization (WHO) in Geneva in 2007, further research was recommended into patient safety, based on the fact that an estimated 10 million people around the world die or become disabled per year due to preventable medical errors. Although studies into safe patient care have increased worldwide in line with this recommendation, the rate of medical errors has not decreased as predicted.5 According to Hakeri, 1,060 files were submitted to departments of forensic medicine following a death in 2013, and 100 physicians were found to be at fault, indicating the 100 out of 1000 physicians involved in malpractice lawsuits were found to be at fault in Turkey. The reason for this is that although files are brought against the physician in the event of patient death, it is normally organizational failure that is to blame.6

Intention and negligence are important factors in the occurrence of medical errors. Intention is defined as acting deliberately, despite knowing that the action is against the rules; while negligence refers to unintentional medical errors that result from a lack of sufficient attention while taking measures.7 Medical errors generally occur when the necessary works are not carried out in accordance with the established standards (negligence), or doing what must not be done (carelessness).8 In medical malpractice cases that occur due to negligence, the service provided by the healthcare professional is below acceptable standards. There are certain legal conditions to consider when defining a medical outcome as malpractice, such as the presence of an established relationship, being against the law, the presence of an injury, the presence of medical error, and the presence of a causal relationship. 9

There are three main sources of medical error: human-derived, organizational and technical. Human-derived causes can result from insufficient education and fatigue.10, and failure to take precautions, insufficient communication, carelessness, inadequate time given, incorrect decisions, lack of reasoning and disputatious personality.11 Human-derived errors can be further classified as medication errors, surgical errors and diagnostic errors.12 Errors related to negligence (failure to take the correct

approach), action (using a wrong procedure) and procedure (doing the right procedure in a wrong way) are common human-derived errors.13 Organizational errors can relate to the physical condition of the workplace, the administrative structure, the policies followed, the improper allocation of personnel and failure to resolve problems. Finally, technical errors refer to those based on the failure or absence of a device .14,15

Malpractice is the main aspect of patient safety emphasized by the International Council of Nurses (ICN).16 Medical errors in nursing practice include inattentiveness, failure to take precautions, lack or insufficiency of professional experience, carelessness, and failure to follow orders and instructions.17 Conditions that involve nurses in legal problems include violation of patient safety and negligence, errors in the administration of drugs and blood transfusions, errors or failures in the use of medical devices, miscommunication, missing records, nonadherence to existing protocols, hospital infections, patient falls and bed sores. 18,12,19

Medication errors, which can be detrimental to patient safety and which increase morbidity-mortality and treatment costs, are significant health problems worldwide.20,21,22 According to the United States National Coordinating Council for Medication Error Reporting and Prevention 23, “a medication error is any preventable event that may cause or lead to inappropriate medication use or patient harm while the medication is in the control of the health care professional, patient, or consumer”.23 In a study by Milch et al. (2006) in which reports of medical errors and side effects in 2006 were examined, 33 percent of the reported errors were related to medication, and were reported by the nurses.24 Nonadherence to basic rules has been suggested as the most common cause of error during the preparation and administration of medication leading to lawsuits.18,25. In a review of 33 studies related to medication errors, Wright (2010) concluded that more attention must be paid to the preparation and administration of medication .26

Hospital infections, as a common occurrence, can be spread by healthcare professionals who are constantly in close contact with patients and are responsible for their care, but can also result from an excessive number of patients in a hospital room, high mobility within the hospital, and serious and complex medical interventions.27,28

Falls are medical errors that frequently lead to lawsuits against nurses. In the United States, falls account for 30 percent of non-fatal injuries among patients aged 65 years and older.29, 30 Being aware of the medical history of the patient and taking appropriate precautions after determining the risk of fall would prevent many of these cases.31

Another type of medical error relates to patient follow-up and material safety. In many developed countries, the insufficiency of patient follow-up is the most common cause of malpractice lawsuits.32 Accurate and timely recording, effective communication, and appropriate equipment and diagnostic-therapeutic procedures can decrease the probability of errors. 33,34,35,36

Medical errors resulting from miscommunication are common during the delivery of healthcare services. The interaction between the patient and the healthcare professional in the diagnosis and treatment processes is an important factor affecting patient satisfaction and the quality of service provided.37

According to the “Regulation on Ensuring Patient and Employee Safety” in Turkey, healthcare institutions are responsible for the safety of the service provider and the recipient. Upon receipt of a complaint, the relevant units are notified after a preliminary evaluation by the patient rights unit.38 All errors must be reported to allow preventable errors to be precluded rather than imposing penalties on the responsible persons.39 In a study by Lawton and Parker (2002) examining the attitudes of healthcare professionals towards the reporting of errors, physicians in particular were found to be reluctant to report medical errors due to occupational autonomy 40, while in a study by Gökdoğan and Yorgun (2010), it was found that most nurses feel comfortable about reporting errors.41 Karaca and Arslan (2013) emphasized the importance of establishing an efficient error reporting system and controlling patient safety in the prevention of medical errors. 42

The present study was conducted to evaluate the likelihood of attending healthcare professionals who are directly responsible for patient care (nurses, midwives, emergency medical technicians) to make medical errors.

II. MATERIAL AND METHOD

The study was approved by the ethics committee (decree number 2015.44/29, dated July 3, 2015) and written permission was received from the hospitals in which the study was carried out. Data was collected between September 2015 and February 2016. The participants read the informed consent section of the data collection form and their consent was obtained.

2.1. Data and sample

The study population comprised 1,780 healthcare professionals who provide healthcare services in three training and research hospitals in the province of Adana, Turkey. The final study sample was composed of 560 subjects, including 499 nurses, 34 midwives, nine emergency medicine technicians and 18 medical assistants.

The study data was collected through face-to-face interviews, using the Scale of Malpractice Tendency (SMT) validated by Ozata and Altunkan (2010) and the Personal Data Form developed by the researchers for data collection.

The responses to each of the 49 items on the scale were rated on a 5-point Likert-type scale , with the participants being asked to mark the most appropriate option according to their preferences,

ranging from “1” (never) to “5” (always). The maximum and minimum possible scores were in the 49–245 point range. The higher the total score in the scale, the lower the tendency to make medical errors.

2.2. Statistical analysis

The SPSS 20.0 software package, Kolmogrov Smirnov test, t test, one-way analysis of variance, Pearson’s correlation coefficient, Scheffe or Tamhane tests were used for the statistical analysis of the data. A linear regression analysis was made performed to determine the characteristics affecting the SMT subscale scores the most. The level of statistical significance was set as 0.05 in all analyses.

III. RESULTS

The Cronbach’s alpha internal consistency coefficient of the scale was calculated at 0.84, and the mean total score of the scale was found to be 235.97±14.06.The mean subscale scores are presented in TableI.

Table I. Numerical values for SMT

Of the study participants, 24 percent have provided patient care for 6–10 years, 45 percent have worked at the same institution for 1–5 years, 52 percent have worked in the same unit for 1–5 years, 47 percent work fewer than 45 hours per week, and 51 percent work from 1–5 nightshifts per month. Of the participants, 39 percent were observed to be indecisive when asked about job satisfaction. Of the study participants, 79 percent reported that they were healthy and 28 percent slept for around six hours per day. The medication administration and transfusions, falls and communications subscale scores were observed to vary from clinic to clinic (p<0.05), while the scores in these three subscales were higher among the healthcare professionals working in surgical units. The mean total scores in all subscales were higher in healthcare professionals aged 40 years and older when compared to the other age groups (Table II).

*avr: avarege, SD: standard deviation, a25: under 25 years- comparision for 40 years and over p<0.05, b25-29: between 25-29 years- comparision for 40 years and over p<0.05, comparision for cÇÜTF Balcalı Hospital-Başkent University Hospital p<0.05, comparision for dÇÜTF Balcalı Hospital – Numune Hospital p<0.05, comparision for eBaşkent Hospital-Numune Hospital p<0.05,comparision for Assocation-University or above graduate p<0.05.

In an evaluation of the relationship between the sociodemographic characteristics of the study participants and the mean SMT subscale scores, all subscale scores, aside from the communication subscale, varied from institution to institution (Table III).

and SMT Subscale Score Averages

Table III. Assessment of Relationship Between Vocational Qualifications of Healthcare Workers and SMT Subscale Score Averages (Continued)

* Avr: Avarege, SD: Standard Deviation.

a Comparision for 1 years less - 21 years and over for p <0.05,

b Comparision for1-5 years - 21 years and over for p <0.05 cp <0.05 comparision for 6-10 years - 21 years and over, dp <0.05 comparison for less than d1 year and 11-15 years, ep <0.05 comparison for 1-5 years and 11-15 years,

fp <0.05 comparison for 6-10 years - 11-15 years,

gp <0.05 comparison for less than 1 years and 16-20 years, hp <0.05 comparison for 1-5 years - 16-20 years,

i p<0.05 comparison for 6-10 years and 16-20 years, a-f : a,b,c,d,e,f a-i : a,b,c,d,e,f,g,h,i jp <0.05 comparison for over 45 hours and less than 45 hours

kp < 0.05 45 for comparison 45 hours and over 45 hours lp <0.05, for comparison between 1-5 patients 11-15 patients m p <0.05 for comparison 11-15 patients - 16-20 patients

n p <0.05 for comparison between I'm not satisfied at all - very satisfied

o p <0.05 comparison forI am not pleased-very satisfied with the comparison for p <0.05, p p <0.05 comparison for Unstable - very satisfied,

rp <0.05comparison for inferiority - satisfaction

IV. DISCUSSION

In the present study, 63 percent of the participants had graduate and postgraduate degrees, which supports the idea that malpractice tendencies decrease with increasing educational level, as suggested in the study by Anezz (2006).

The scores in the medication and transfusion subscale (87.22±4.23) show that the participants had a low malpractice tendency. The mean score in this subscale was found to be 86.56±3.54 in the study by Dikmen et al. (2014), compared to 86.14±4.77 in the study by Alan and Khorshid (2016). When compared to these results, the participants in the present study had a lower tendency to malpractice.43,44

The participants’ mean scores in the “I make it sure that I administer the correct medication to the patient” and “I pay attention to administering the drug to the correct site during IV, IM and SC injections” subscale expressions were found to be 4.93±0.28, indicating the particular attention paid in these fields. Dikmen et al.(2014) also reported the highest scores in this expression (4.98±0.13).43 This finding can be attributed to the attention paid to learning and reinforcement during the process of education in the administration of drugs. The lowest score (4.60) in the study was noted in the expression of “I know about the side effects of the drugs, and administer accordingly”. In the study by Çırpı et al. (2009), the mean score in this subscale expression was found to be 4.44±0.63.45 The

fact that the lowest mean score was identified for this expression in the present study indicates the lower tendency of the participants to malpractice when compared to those in similar studies. Reid et al. (2009) reported that the rate of side effects following drug administration in their study was 13.3 percent, and 0.4 percent of these side effects resulted in death.46 Aygin et al. (2002) determined that the majority of surgical nurses lacked sufficient knowledge of premedication drugs and their side effects. Such a lack of knowledge on the side effects of drugs and failure to monitor the effects of drug after administration complicate the prevention of conditions that may harm the patient, and may even lead to death.47 The role of nurses in the administration of drugs is not solely administering the drug as prescribed. The professional responsibility attributed to drug administration also involves having sufficient knowledge of the relevant drug, errorless/safe administration, monitoring the physiological response to the drug, interpretation and providing education to the patient and their relatives about drug therapy. Gülçin et al. (2016) found that the lowest scores of nurses in the “Medication Administration and Transfusion” subscale were noted in the expression “I follow the patient sufficiently after drug administration”.48 Young et al. (2008) found that “administration at wrong time” ranked first (70.8%) among all other medication errors.49 In our study, it is reasonable to suggest that the participants adhered to the drug confirmation system.

In our study, the mean scores in the subscales were highest among the participants aged 40 years and older. Üstüner et al.(2016) found a significant relationship between drug administration errors of nurses and age, educational level, work experience, number of cared patients and working conditions (day work/night shifts).50 Tang et al. (2007) reported that medication errors involving nurses mostly occur among personnel that have recently started working in the profession. It is considered that medical errors decrease with the increasing number of years worked in the occupation, as occupational knowledge and skills develop as experience is accumulated.

Factors associated with medical errors that have been reported in literature include interruptions during the administration of medication, lack of sufficient knowledge and skills, failure to use the confirmation system, excessive workloads, problems encountered in the continuity of care and the lack of sufficient communication between the members of the healthcare team.25,51,52 Al-Shara (2011) observed that the majority of medication errors can be traced to excessive workload.53 Ersun et al. (2013) reported that the most common medical errors among nurses relate to the administration of medication,54 while Ertem et al. (2009) reported that medication errors decreased as the number of nurses working at the clinics increased.12 The conscious administration of medications in the light of accurate knowledge minimizes the probability of medical errors, while also increasing treatment success substantially.55

The mean score in the “Hospital Infections” subscale of the SMT was calculated as 57.69±3.43, while the mean score in this subscale was calculated as 57.29±4.33 by Alan and

Khorshid (2016), and as 57.67±2.79 by Dikmen and Yorgun.43,44 It is reasonable to suggest that the participants had a low probability of malpractice in this subscale. In the evaluation of this subscale, the highest score (4.88) was noted in the expressions “I pay attention to not to contaminate infused fluids during preparation and administration” and “I avoid the use of materials if safety concerns arise”. Although an indwelling catheter must be left in place for a maximum of 96 hours due to the risk of catheter infection and thrombophlebitis 55, the mean score was 4.71 for the expression “I pay attention to the 72–96-hour IV catheterization time.” Although this rate is low, it cannot be suggested that the associated likelihood of malpractice would be high.

The mean score in the “Patient Follow-up and Material Safety” subscale was 42.71±3.24, and the mean score in this subscale was higher among undergraduate (n=96) participants when compared to graduate and/or postgraduate (n=353) participants. This finding can be attributed to the fact that the undergraduate participants were those who were aged 40 years and older who had more job experience. The mean score in this subscale was reported to be 39.98±3.91 by Dikmen et al. (2014) and 40.70±4.24 by Alan and Khorshid.43,44 The mean malpractice scores of the participants in this subscale was found to be lower than those reported in other studies.

The mean score in the “Falls” subscale was found to be 23.99±1.78, with the highest scores in this subscale being noted in the expressions “I pay attention to the presence of grab bars/hand guards and guards at the edges of the patients’ beds” and “I ensure that precautions are taken during the transportation of the patient.” The lowest score (4.49±0.73) in the study by Dikmen et al. (2014) was noted in the expression “I provide information to the patient and his/her relatives about the causes of falls, and the measures that can be taken”,43 and the same expression also received the lowest score (4.74) in the present study. Preventing the access of a patient’s relatives into certain clinics may be associated with this result.

The mean score in the “Communication” subscale of the SMT was calculated as 24.36±1.38, while the mean score in the same subscale was found to be 23.00±2.17 by Dikmen and Yorgun (2014) and 23.20±2.17 by Alan and Khorshid (2016), with similar results reported by Telli (2013). 43,44, 56 Meginniss et al. (2012) reported that 60–80 percent of more than 40,000 medical errors that occurred in the United States in 2009 were actually a result of ineffective communication and insufficient team work.57 In our study, the mean malpractice tendency subscale score was found to be higher in the communication subscale when compared to other studies. Accordingly, it can be said that the participants experience no problems relating to communication.

The mean score in the “Communication” subscale increased with increasing number of years worked in the occupation, and job experience is also found to increase, and accordingly, the likelihood of malpractice is found to decrease, with the increasing number of years worked (p<0.05). The mean scores in all subscales, aside from in the “Patient Follow-up and Material Safety”

subscale, varied according to the total duration of time worked in the institution or unit. Şahin et al.(2015) found that the scores in all subscales, aside from the “Patient Follow-up and Material Safety” subscale, varied according to the total duration of time worked in the institution or unit, which supports the current findings (p<0.05).58

The present study found no change in the SMT subscale scores of the participating healthcare professionals related to shift patterns and the number of nightshifts per month. The mean scores of participating healthcare professionals in all SMT subscales, aside from in the “Communication” subscale, varied in line with the mean hours worked per week (p<0.05).

The mean scores of the participating healthcare professionals in all subscales, aside from the “Medication Administration and Transfusion” and “Hospital Infections” subscales, varied according to the daily number of patients provided with care. The mean scores in patient follow-up and material safety and falls subscales were lower among healthcare professionals providing care to 11–15 patients per day when compared to those providing care to 1–5 patients per day. These results are consistent with those reported by Alan and Khorshid (2016) (Alan 2016), and this finding can be attributed to the distinct needs of intensive care unit patients and those admitted to the clinic. In most hospitals, junior nurses that have recently started working are assigned to tasks in the intensive care unit. In the present study, the healthcare professionals that provide care to fewer patients (1–5) are those who work in the internal medicine and surgical intensive care units, and who have less than a year’s experience. It is reasonable to suggest that these participants are in possession of contemporary occupational knowledge, and act more cautiously with the fear of medical error, and this decreases their tendency to malpractice. It was observed that healthcare professional providing care to 11–15 patients per day achieved lower scores in the communication subscale when compared to their scores in the other subscales, and there was a significant difference between the groups (p<0.05). Although studies in literature suggest that the likelihood of malpractice increases particularly in the communication subscale with the increasing number of patients cared for per day, the increase in the number of patients in the present study did not increase the tendency to malpractice.43,44

V. CONCLUSION AND RECOMENDATIONS

The present study evaluated the tendency to malpractice among 560 healthcare professionals providing patient care, and found that the participants had a low tendency to make medical errors. Compared to the other age groups, the mean total scale score was found to be higher in participants aged 40 years and older, and their malpractice tendency was lower. Healthcare professionals are involved in fewer malpractice cases due to the increased professional knowledge and skills associated with increased years of employment in the job that comes with increasing age.

Although the present study found a low tendency to malpractice, in-service training on patient safety must be provided to prevent possible malpractice cases. An ethical environment must be created in the institution to ensure the safety of both employees and patients. Considering the fact that burnout or occupational boredom may lead to medical errors, the necessary arrangements in the workplace must be made by managers considering the negative effects of working conditions, workload and stress.

REFERENCES

1.Yıldırım A, Aksu M, Çetin İ, Şahan AG.(2009). Tokat ili merkezinde çalışan hekimlerin tıbbi uygulama hataları ile ilgili bilgi, tutum ve davranışları. Cumhuriyet Tıp Dergisi (31), 356-366. 2.Pronovost PJ, Thompson DA, Holzmueller CG, Lubomski LH, Morlock LL. Defining and Measuring Patient Safety. Critical Care Clinics. 2005; 21:1-19.

3.İntepeler Ş.S., Dursun M.(2012). Tıbbi Hatalar Ve Tıbbi Hata Bildirim Sistemleri. Anadolu

Hemşirelik Ve Sağlık Bilimleri Dergisi, (15), 129-135.

4.Anezz E. (2006). Clinical perspectives on patient safety. In: K Wals, R Boaden (Eds.), Patient Safety Research in to Practice. (1st ed.) London: McGraw Hill Education Open University Press (pp. 9-18).

5.World Health Organization (WHO). (2007). Call For More Researche On Patent Safety, Available from URL, http://www.who.int/mediacentre/ news/releases/ 2007.

6.Hakeri H.(2014). “Hastane Yöneticilerinin Hukuki Sorumluluğu”, I. Sağlık Hukuku Sempozyumu,

İzmir Üniversitesi Hukuk Fakültesi, 15.Mart.2014 İzmir.

7.Özata M, Altunkan H.(2010). Hastanelerde tıbbi hata görülme sıklıkları, tıbbi hata türleri ve tıbbi hata nedenlerinin belirlenmesi: Konya örneği. Tıp Araştırmaları Dergisi, 8(2), 100-111.

8.Hancı İH.(2001). Malpraktis: Tıbbi Girişimler Nedeniyle Hekimin Ceza ve Tazminat Sorumluluğu. I. Baskı. Ankara. Seçkin Yayıncılık.

9.Hanyaloğlu A.(2011). Malpraktis Hekimler İçin Hukuksal Yaklaşım Ve Sigorta Rehberi. Nobel Tıp Kitap Evleri ltd.şti. İstanbul (pp.1-2).

10.Akalın HE. 2007). Klinik araştırmalar ve hasta güvenliği. İyi Klinik Uygulamalar (İKU)

Dergisi.(17),32– 35.

11.Güven R. (2007). Dezenfeksiyon ve sterilizasyon uygulamalarında hasta güvenliği kavramı, 5. Ulusal Sterilizasyon Dezenfeksiyon Kongresi (pp. 411).

12.Ertem G, Oksel E, Akbıyık A. (2009). Hatalı Tıbbi Uygulamalar (Malpraktis) İle İlgili Retrospektif Bir İnceleme. Dirim Tıp Gazetesi 84(1),1-10.

13.Mitchell PH.(2008). Defining Patient Safety and Quality Care. In Hughes RG Ed, Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, RockvillePatient Safety And Quality: An Evidence-Based Handbook For Nurses. First ed. Rockville: AHRQ Publication No.08-0043 (pp.1-5).

14.Top M, Gider Ö, Taş Y, Çimen S. (2008). Hekimlerin Tıbbi Hataya Neden Olan Faktörlere İlişkin Değerlendirmeleri: Kocaeli İlinden Bir Alan Çalışması, Hacettepe Sİ D, 11(2),161-199.

15.Adams JL, Garber S.(2007).Reducing Medical Malpractice By Targeting Physicians Making Medical Malpractice Payments, Journal of Empirical Legal Studies (4),185–222.

16.International Council of Nurses (ICN).(2006).Why is safe staffing importent? Safe Staffing Saves

Lives. International Nurses Day, Information and Action Tool Kit. 1 st ed. Geneva (pp. 9-12).

17.Kocaman G.(2007). Hemşirelik Hizmetlerinde Hasta Güvenliği Ve Liderlik. Hemşirelik Hizmetlerinde Hasta Güvenliği Paneli. İzmir..

18.Demir Zencirci A.(2010). Hemşirelik ve Hatalı Tıbbi Uygulamalar. Hemşirelikte Araştırma

Geliştirme Dergisi 12(1),67-74.

19.Cebeci F, Gürsoy E, Tekingündüz S. (2012). “Hemşirelerin Tıbbi Hata Yapma Eğilimlerinin Belirlenmesi” Anadolu Hemşirelik ve Sağlık Bilimleri Dergisi 15(3),188-196.

20.Akalın HE. (2005). Yoğun Bakım Ünitelerinde Hasta Güvenliği. Yoğun Bakım Dergisi 5(3),141-146.

21.Durmaz A.(2007).Hastaların Hastaneye Yatmadan Önce Kullandıkları İlaçların Kliniğe Kabul Edildikten Sonra Kullanımı İle İlgili İlaç Hatalarının İncelenmesi. Hemşirelik Esasları Yüksek Lisans Tezi, Dokuz Eylül Üniversitesi Sağlık Bilimleri Enstitüsü, İzmir.

22.Sharek PJ, Classen D. (2006). The İncidence Of Adverse Events And Medical Error in Pediatrics, Pediatric Clinics Of North America, (53),1067-1077.

23.NCCMERP (2009), About Medication Errors, www.nccmerp.org/aboutMedErrors.html. Erişim tarihi: 20.04.2017.

24.Milch CE, Salem DN, Pauker SG, Lundquist TG, Kumar S, Chen J. Voluntary (2006). Electronic Reporting Of Medical Errors And Adverse Events An Analysis Of 92,547 Reports From 26 Acute Care Hospitals. Journal of General Internal Medicine 21(2),165–70.

25.Nguyen EE, Connolly PM, Wong V. (2010). Medication Safety Initiative in Reducing Medication Errors. Journal of Nursing Care Quality 25 (3), 224-230.

26.Wright K.(2010). Do Calculation Errors By Nurses Cause Medication Errors In Clinical Practice? A Literature Review. Nurse Education Today 30(1), 85-97.

27.Özçetin M, Saz EP, Karapınar B, Özen S, Aydemir Ş, Vardar F. (2009). Hastane Enfeksiyonları; Sıklığı ve Risk Faktörleri. Çocuk Enfeksiyonları Dergisi (3), 49-53.

28.Postnote (2005) Infection control in healthcare settings,

http://www.parliament.uk/documents/upload/ POSTpn247.pdf Erişim tarihi: 02.01.2016.

29.Koh SSL, Manias E, Hutchinson AM, Donath S, Johnston L.(2008). Nurses’ Perceived Barriers To The Implementation Of A Fall Prevention Clinical Practice Guideline in Singapore Hospitals,

BMC Health Services Research. (8),105-111.

30.Dreschnack Gavin D,Nelson A, Fitzgerald S,Harrow J, Sanchez Anguiano A, Ahmed S, Powwel-Cope G, Wheelchair-Related Falls.(2005). Current Evidence and Directions For İmproved

Quality Care, Journal Of Nursing Care Quality 20(2),119-127.

31.Morse JM.(2008). Preventing Patient Falls: Establihing a Fall Intervention Program, Second Publishing, (pp. 3-5).

32.Safran N.(2004). Hemşirelik ve Ebelikte Malpraktis, İstanbul Üniversitesi Adli Tıp Enstitüsü Sosyal Bilimler Anabilim Dalı, (yayımlanmamış) Doktora Tezi, İstanbul.

33.Mete S, Ulusoy E.(2006). Hemşirelikte İlaç Uygulama Hataları, Hemşirelik Forum Dergisi (pp. 36-41).

34.Aştı T, Acaroğlu R. (2000). Hemşirelikte Sık Karşılaşılan Hatalı Uygulamalar. İ.Ü. HYD.4(2), 22-27.

35.Temel M. (2005). Sağlık Personelini ilgilendiren Önemli Bir Konu: Malpraktis, HFD (pp.84- 90).

36.Çelik F. (2008). Sağlık Kurumlarında iletişim; Hasta ile Sağlık Personeli iletişimi Üzerine Bir Araştırma, Selçuk Üniversitesi Sosyal Bilimler Enstitüsü, (yayımlanmammış)Yüksek Lisans Tezi. 37.Tang FI, Sheu SJ, Yu S, Wei IL, Huey C.(2007). Nurses Relate The Contributing Factors İnvolved İn Medication Errors. Journal Of Clinical Nursing, (16), 447-457.

38.Hasta ve Çalışan Güvenliğinin Sağlanmasına Dair Yönetmelik.

http://www.resmigazete.gov.tr/eskiler/2011/04/20110406-3.htm. Erişim Tarihi: 12.06.2017.

39.Evans SM, Berry JG, Smith BJ. (2006). Attitudes and barriers to incident reporting: A collaborative hospital study. Quality and Safety Health Care 6(15),39-43.

40.Lawton R, Parker D. (2002). Barriers to Incident Reporting in a Healthcare System. Quality and

Safety in Health Care (pp.11-15).

41.Gökdoğan F, Yorgun S. (2010). Sağlık hizmetlerinde hasta güvenliği ve hemşireler. Anadolu

Hemşirelik ve Sağlık Bilimleri Dergisi 13(2),53-59.

42.Karaca A, Arslan H.(2013). Üniversite Hastanesinde Çalışan Hemşirelerde Hasta Güvenliği Kültürünün İncelenmesi. F.N. Hem. Derg. Araştırma Yazısı 21(3), 172-180 (Issn 2147-4923). 43.Dikmen Y, Yorgun S, Yeşilçam N. (2014). Hemşirelerin Tıbbi Hatalara Eğilimlerinin Belirlenmesi. Hacettepe Üniversitesi Hemşirelik Fakültesi Dergisi 44–56.

44.Alan N, Khorsthd L.(2016).Bir Üniversite Hastanesinde Çalışan Hemşirelerin Tıbbi Hataya Eğilim Düzeylerinin Belirlenmesi. Ege Üniversitesi Hemşirelik Fakültesi Dergisi 32(1),1-18. 45.Çırpı F, Doğan Merih Y, Yaşar Kocabey M. (2009). Hasta Güvenliğine Yönelik Hemşirelik Uygulamalarının Ve Hemşirelerin Bu Konudaki Görüşlerinin Belirlenmesi. Maltepe Üniversitesi

Hemşirelik Bilim Ve Sanatı Dergisi 2(3),26-34.

46.Reid M, Estacio R, Albert R. (2009). Injury And Death Associated With incidents Reported To The Patient Safety Net. American Journal of Medical Quality. (24), 520-524.

47.Aygin D, Atasoy I. (2002). Hemşirelerin Premedikasyona İlişkin Bilgi Düzeyleri Ve Uygulamalarının Belirlenmesi. III. Ulusal–I. Uluslararası Ameliyathane Hemşireliği Kongresi. Hemşirelik Forumu. 5(3-4),65-68.

48.Gülçin A, Atabek Armutçu E, Karaman Özlü Z. (2016). Hemşirelerin Tıbbi Hata Eğilim Düzeyleri ve Tıbbi Hata Türleri: Bir Hastane Örneği HSP 3(2),115-122.

49.Young M, Gray SL, Mc Cormick WC. et al.(2008). Types, Prevalence, And Potential Clinical Significance Of Medication Administration Errors In Assisted Living, J Am Geriatr. Soc. 56 (7), 1199–1205.

50.Top ÜF, Çam HH.(2016). Hastanede Çalışan Hemşirelerin İlaç Uygulama Hataları ve Etkileyen Faktörlerin İncelenmesi. TAFPrev Med Bull (15),3.

51.Hellings J, Schrooten W, Klazinga N, Vleugels A.(2007). Challenging patient safety culture: Survey results. Int J Health Care Qual Assur, 20(7),620-632.

52.Taylor C, Lillis C, Lemone P, Lynn P. (2011). Fundamentals of Nursing: The Art and Science of

Nursing Care. 7th ed. Philadelphia (pp. 51-59).

53.Al-Shara M. (2011). Factors contributing to medication errors in Jordan: a nursing perspective. Iranian Journal of Nursing and Midwifery Research. 16(2),158-161.

54.Ersun A, Başbakkal Z, Yardımcı F, Muslu G, Beytut D.(2013). Çocuk hemşirelerinin tıbbi hata yapma eğilimlerinin incelenmesi. Ege Üniversitesi Hemşirelik Fakültesi Dergisi 29(2),33-45. 55.Perry AG, Potter P.(2011). Klinik Uygulama Becerileri ve Yöntemleri, Ed. Atabek Aştı T, Karadağ A. Nobel Kitabevi, Adana, (pp.901).

56.Telli S. (2013). Hemşirelerin Farklı Çalışma Saatlerindeki Durumluk Anksiyeteleri ve Tıbbi Hataya Eğilimlerinin İncelenmesi. Yayınlanmamış Y. L. Tezi. İzmir: Ege Üniversitesi Sağlık Bilimleri Enstitüsü(pp. 44).

57.Meginniss A, Damian F, FalvoF. (2012). “Tıme Out” for Patıent Safety. Journal of Emergency

Nursing 38(1),51-53.

58.Şahin ZA, Özdemir FK. (2015). Hemşirelerin Tıbbi Hata Yapma Eğilimlerinin İncelenmesi.