Disponibleenlignesur

www.sciencedirect.com

ORIGINAL

ARTICLE

Effect

of

high

intensity

interval

training

on

elite

athletes’

antioxidant

status

Effet

de

l’entraînement

par

intervalles

à

haute

intensité

sur

le

statut

antioxydant

des

athlètes

de

haut

niveau

A.

Faruk

Ugras

BilkentUniversity,DepartmentofPhysicalEducationandSports,06800Ankara,Turkey Received28July2010;accepted25April2012

Availableonline7June2012

KEYWORDS Athletes; Intervaltraining; SOD; CAT; GPX; MDA Summary

Objective.—Theeffectsofhighintensityintervalexercisesonantioxidantdefensesystemare not clear.Since thereisanevidentlackofstudies focusedonoxidative stressexperienced followingcombatsportsandhighintensityintervaltraining,weinvestigatedoxidativestress markers (malondialdehyde[MDA], catalase [CAT],glutathione peroxidase[GPX], superoxide dismutase[SOD])bycompletinghighintensityintervaltrainingprogram(HIITP)andfollowing InternationalMuayThaiChampionship(IMTC).

Methods.—Thestudywascarriedouton21eliteplayers(15malesandsixfemales)whohad regularexercisingandtraininghabits.Theparticipantsweresubjectedtoadaily3-hourHIITP duringbrieftrainingcamp(10-day)beforeIMTC.Theywereinstructedtomaintaintheirnormal dietarypracticesthroughoutthecampandduringthestudytotakenoantioxidantcontaining vitamintablets.

Results.—TherewasasignificantincreaseinMDAlevelsandsignificantdecreaseinCAT activi-tiesofplayers(P<0.05).ThedifferencesinSODandGPXactivitieswerenotsignificant.

Conclusion.—Theseresultssuggestedthathighintensityintervaltrainingandcompetitioncould affecttheoxidativestatusofMuayThai(MT)athletes.

©2012ElsevierMassonSAS.Allrightsreserved.

MOTSCLÉS Athlètes; Entraînementpar intervalles; SOD; CAT; Résumé

Objectif.—Leseffetsdesexercicesdehauteintensitéparintervallesurlesystèmededéfense antioxydantnesontpasclairs.Commeilexisteunmanqueévidentd’étudesportantsurlestress oxydatifsurvenulorsdessportsdecombatetd’entraînementsparintervallesàhaute inten-sité, nous avonsétudiéles marqueursde stress oxydatif(malondialdehyde[MDA], catalase

[CAT], glutathione peroxidase [GPX], superoxide dismutase [SOD]) en complétant les pro-grammesd’entraînementsparintervalledehauteintensité(EPI)etàlasuiteduChampionnat internationaldeMuayThaï(IMTC).

E-mailaddress:ugras@bilkent.edu.tr

0765-1597/$–seefrontmatter©2012ElsevierMassonSAS.Allrightsreserved. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.scispo.2012.04.009

GPX; MDA

Méthodes.—L’étudeaétéréaliséesur21athlètesdehautniveau(15hommesetsixfemmes) quiavaientl’habituded’effectuerdesexercicesetdesentraînementsréguliers.Les partici-pantsontétésoumisàunprogrammed’entraînementsparintervallejournaliersdetroisheures (EPI)pendantdesstagesd’entraînementdecourtedurée(dixjours)avantleIMTC.Les ath-lètesavaientpourinstructiondemaintenirleurshabitudesalimentairespendanttouteladurée dustaged’entraînementetdeneprendreaucuncomprimédevitaminesantioxydantsdurant l’étude.

Résultats.—Il y aeuuneaugmentation significativedes niveauxde MDAet unediminution significativedesactivitésdeCATdesathlètes(P<0,05).Lesdifférencesdanslesactivitésde SODetdeGPXnesontpassignificatives.

Conclusion.—Cerésultat suggèreque l’entraînementparintervalledehaute intensitéet la compétitionpeutaffecterlestatutoxydatifdesathlètesdeMuayThaï(MT).

©2012ElsevierMassonSAS.Tousdroitsréservés.

1.

Introduction

Reactive oxygen species (ROS) are generated by regular metabolic process in vivo and can initiate a cascade of free-radicalformationanddamagetomacromolecules[1].

Oxidativestressisaninevitableconsequenceofaerobiclife,

andthereisgrowingevidencethattheendogenous

genera-tionofROSplaysamajorroleinagingandmanypathological

conditions[2]. In resting state the bodyis equipped with

both non-enzymatic and enzymatic antioxidant defense

systemtoscavengethepotentially harmfuleffectsofROS

[3,4].Thissystemincludesantioxidantenzymessuchas

glu-tathioneperoxidase(GPX),catalase(CAT),andsuperoxide

dismutase (SOD), and non-enzymatic molecules including

vitaminE,vitaminC,vitaminAprecursor,thiol-containing

compounds e.g. glutathione (GSH). These antioxidant

defense systems preserve homeostasis for normal cell

functionsatrestandundernormalphysiologicalconditions.

However,duringstrenuous exercise, pathogenic processes

and aging, ROS production may overwhelm antioxidant

defense capacity causing cell and tissue damage [5,6].

As consequencesthe bilayerlipid membraneof the cells,

proteins, and even DNA material may suffer oxidative

damage[7].

Manyathletesinvolvedindifferentintensephysical

activ-itiesduringphysicaltrainingandsportiveevents,whichare

performedinuncontrolledsettingandoftenpossess

compo-nentsofbothanaerobicandanaerobicnature[8].Excessive

trainingcanproduce oxidative stressand antioxidant

ele-mentsof organismswereaffected withthischallenge[9].

Fewstudieshaveinvestigatedoxidativestressinresponseto

bothaerobicandanaerobicexercisebouts[10,11]especially

oxidative stress, which is experienced following sporting

competitions [8]. Higher resting plasma MDA levels were

reportedin sprint-trainedathletes comparedwithcontrol

subjects.ItwasreportedthatplasmaMDAlevelsfollowing

anextremeenduranceeventineliteathleteincreased[12].

Severalstudieshavealsoreportedthatacute,highintensity

physicalexerciseinducesoxidativestress[13—16].

Muay Thai (MT) is one of the combat sports and field

observationhasshownthatitisintermittentinnatureand

similartothatofkarate,taekwondo,boxingandwrestling.

MTtrainingconsistsofbothstrenuousandexhaustive

exer-cises[17].MTinvolvesastyleofboxingwherecompetitors

try to win bouts and international level amateur bouts

involve four 2-minute rounds with 1-minute rest periods

[18]. Sparring is very intermittent in nature,divided into

periods of veryhigh intensive activity (whenattacking or

blocking) and low intensive activity when the athlete is

preparing for an attack or just moving around [19] from

which athletes can receive short term recovery, as well

as time to prepare for following attack. Thus, sparring

performances principally rely on the immediate (ATP-PC)

and short-term (Glycolysis) energy systems [17]. As the

developmentoffreeradicalsandscavengingofthemarean

importantconsiderationforoptimalperformance,recovery,

and health for players [20]. We aimed to investigate the

oxidativestatusofMTathletesbycompletinghighintensity

intervaltrainingprogram(HIITP)andfollowingInternational

MuayThaichampionship(IMTC).

2.

Methods

2.1. Subjects

Inthisstudy,15malesandsixfemalesMTnationalathletes

wereselectedastheathleticsubjects.Theoxidativestress

parametersofathletesbeforecampperiodwereusedasa

controlvalueforapropercomparison.Subjectshadregular

exercising and traininghabits for three times a week for

120minutes at an elite level. Each athlete had at least

6 years of trainingexperience. The exclusion criteriafor

studyweredrugsandmedicinesintakeboth,sufferingfrom

someillnessandcigarettesmoke.Noneoftheathleteshad

tobeexcludedfromthestudy.Duringcamps,athleteswent

undersomeof thehematologicaltestsasanormal

proce-dure. The investigatedperiod included the 10 dayscamp

durationbeforetheIMTC.Beforethetests,theparticipants

were given adequate information about the importance

of the study and they signed a consenting document. All

training sessions took place at the same time of day to

controlthecircadianvariationinperformance.Duringthe

study, the subjects stayed in the same hotel and were

providedwiththesamedietwithoutanyextraantioxidants

or other nutritional supplements. The subjects showed

100% compliance withtheexercise training program.The

participants were instructed to refrain from eating or

drinkingimmediatelybeforethetests,andtorefrainfrom

exercise24hoursbeforeeachtestingsession.Theprotocol

startedonedaybeforethebeginningofthetrainingperiod.

2.2. Physiologicalmeasurements

Thebodymasswasmeasuredusingcalibrateddigitalscales

andheightwasmeasuredusingaportablestadiometer.The

age of athletes were accurately recorded in years. Blood

samplesweretakenfromtheparticipantthreetimes; the

firstonepriortotraining,thesecondoneafterthetraining

campandthethirdoneaftertheIMTC.Wealsoanalyzedthe

oxidative stress biomarkers at threedifferent times:

pre-camp,aftercampandattheendoftheIMTC.Thetraining

consistedofexercisestostrengthenphysicalfitnessthrough

technicaltrainingandsparringpractices.TheHIITPapplied

toallathletes. The present HIITPwasdesignedaccording

toeliteMTathletes’needs,aftertakingintoconsideration

‘‘theprerequisitesinperformance’’.TheHIITPisavaluable

methodfor improving both aerobic andanaerobic fitness.

Trainingintensitywasdeterminedbyuseofmaximalheart

ratemethod[21].

The HIIT sessions lasted approximately 3hours a day;

1½hours in the morning, 1½hours in the afternoon for

the 3rd, 5th, 7th, and 9th day of camp. Athletes began

dailypracticesbothinthemorningandafternoonsessions

witha20minuteswarm-up,thatincludedrunning5minutes

andwasfollowed bycalisthenicsandstretchingexercises.

Afterwarm-up,actualpracticeforHIITPapproximatelytook

52 minutes in the morning and 48minutes in the

after-noonincludingavarietyof repeatedkickingand punching

techniques and mini matches for 12minutes only in the

afternoonsessions.Twentyminutescoolingdownexercises

followed after both trainingprograms. For the remaining

days,athletesrunwithaerobicintensityandpracticelight

MTexercises inthe morning.Intheafternoonallathletes

takeacompleterest.Duringtrainingcamp,alongwiththe

pre-competitiontrainingroutine,mentalandpsychological

skills(emotionalcontrol,arousalmanagementi.e.)tailored

towardsthespecificneedsofathletesandtheypracticedat

thesimulatedcompetition.

2.3. Trainingsession—Highintensityinterval trainingprogram(HIITP)

2.3.1. Morningpractices

Technicalworkout(TW):(frontkick,sidekick,roundhouse

kickandpunches-alldonewithalternatinglegsandarms):

• 20minuteswarm-up;

• 6secondswork(95—100%ofMaxVO2),18secondsrest,20

rpt,totaloftwosetsofwork,5minutesrest1inbetween

theset;

• 10secondswork(95—100%ofMaxVO2),30secondsrest,12

rpt,totaloftwosetsofwork,5minutesrest1inbetween

theset;

• 20minutescoolingdownexercises.

1Passiverecoveryreferstoperiodsthatdonotinvolveanyform

ofactivity.

2.3.2. Afternoonpractices

TW:

• 20minuteswarm-up;

• 30secondswork(80—90%ofMaxVO2),60secondsrest,4

rpt,totaloftwosetsofwork,3minutesrest2inbetween

theset;

• 60secondswork(80—90%ofMaxVO2),120secondsrest,2

rpt,totaloftwosetsofwork,3minutesrest2inbetween

theset;

• 2minutes sparring, total of foursets of work, 1minute

restinbetweentheset;

• 20minutescoolingdownexercises.

2.3.3. Trainingprotocol

Period:10-day.

Trainingfrequency:2timesaday.

1stday:1sttest.

2nd,4th,6th,8thdays:½dayaerobicrunningandlow

intensityMTtechnical/tacticalactivities&½dayrest,3rd,

5th,7th,9thdays:HIITP.

10thday:2ndtest.

Traininghours:10.00—11.30a.m.and5.00—6.30p.m.

Trainingtype:Interval(everyotherday)andaerobiclow

intensityofrunning.

Training intensity: 95—100% of MaxVO2 (Morning) and

80—90%ofMaxVO2(Afternoon).

Trainingperiod:approximately1½hour/session.

BloodTest: 1st,10th days of the camp, and after the

championship.

2.4. Measurementofoxidativestatus

Erythrocyte SOD, GPX, and malondialdehyde (MDA) were

measured as previously described by Aydin et al. [23].

Erythrocyte CAT activity was measured in hemolysates as

describedbyAebi[24].

2.5. Statisticalanalysis

Allstatisticalanalyses werecalculatedbythe SPSS

statis-ticalpackage. A paired t-test wasused todetermine the

differencesin physiological parameters between pre-and

post-values.Datawereexpressedasmeanvalues±standard

deviation(SD)andstandarderror(SE).Differencesbetween

beforeandafter exercises werereported asmean

differ-ence±95%confidenceintervals.Thestatisticalanalysiswas

calculatedwithnon-parametrictestWilcoxonSignedRanks

testfortheoxidativestressparameters.

3.

Results

PhysicalcharacteristicsoftheMTmaleandfemaleathletes

are presented in Table 1. The body weight of male and

femaleathletesdidnotchangedduringthechampionship.

2Active rest-lowto moderateactivityis effectiveimmediately

followingsustainedhighintensitytrainingorcompetition, partic-ularly where the anaerobic glycolytic energy pathway has been substantiallyinvolved[22].

Table1 PhysicalcharacteristicsoftheMuayThai(MT)maleandfemaleathletes.

SelectedPhysicalParameters BeforeX1 AfterX2 Meandifference±95%CI

Male(n=15) Age(year) 20.93±2.43 Height(cm) 178.60±6.98(1.80) Bodyweight(kg) 68.71±13.02(3.36) 68.04±12.72(3.28)* 0.67±0.50(0.13) Female(n=6) Age(year) 18.83±1.47 Height(cm) 170±1.79(0.73) Bodyweight(kg) 57.28±7.58 56.86±7.59(3.09)* 0.41±0.09(0.04)

Valuesarethemean±SD(SE).Beforethecamptraining;afterthecamptraining*(P<0.01).

Table2 TheerythrocyteoxidativestressstatusofMuayThai(MT)athletes.

SOD(U/ml) CAT(KU/ml) GPX(U/ml) MDA(nmol/ml) Pre-training 343.62±168.38 111.06±22.28 11.45±3.12 32.67±2.47 Post-training 330.10±168.40 109.30±17.12 10.76±3.18 45.52±4.01a Afterthechampionship 293.65±128.37 87.07±13.69a,b 11.61±3.07 49.80±2.29a,b SOD:superoxidedismutase;CAT:catalase;GPX:glutathioneperoxidase;MDA:malondialdehyde.n=21(sixfemales,15males).

ap<0.05whencomparedwithpre-training. b p<0.05whencomparedwithpost-training.

0 50 100 150 200 250 300 350 400 450 500

After the championship Post-training Pre-training SO D (U /m l) 0 20 40 60 80 100 120 140 After the Post-training Pre-training championship CA T ( K U/ m l) 0 2 4 6 8 10 12 14 16 After the Post-training Pre-training championship G P x ( U /m l) 0 10 20 30 40 50 60 After the Post-training Pre-training championship M DA (n m ol /m l)

a, b

a, b

a

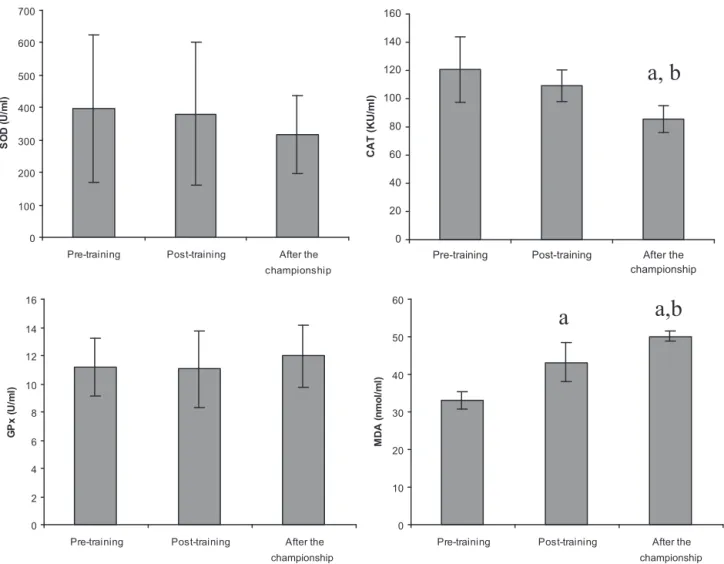

Figure1 Theoxidativestressstatusofmaleathletes.Threedependentgroupswerecomparedwithnon-parametricWilcoxon SignedRankstest.Valuesareexpressedasmean±S.D.SOD:superoxidedismutase;CAT:catalase;GPX:glutathioneperoxidase; MDA:malondialdehyde.n=15.a:P<0.05whencomparedwithpre-training;b:P<0.05whencomparedwithpost-training.

0 100 200 300 400 500 600 700

Pre-training Post-training After the championship

S O D (U /m l) 0 20 40 60 80 100 120 140 160

Pre-training Post-training After the championship CA T (KU /m l) 0 2 4 6 8 10 12 14 16

Pre-training Post-training After the championship GP x (U /m l) 0 10 20 30 40 50 60

Pre-training Post-training After the championship MD A (n m ol /m l)

a, b

a,b

a

Figure2 Theoxidativestressstatusoffemaleathletes.Threedependentgroupswerecomparedwithnon-parametricWilcoxon SignedRankstest.Valuesareexpressedasmean±S.D.SOD:superoxidedismutase;CAT: catalase;GPX:glutathioneperoxidase; MDA:malondialdehyde.n=6.a:P<0.05whencomparedwithpre-training;b:P<0.05whencomparedwithpost-training.

OxidativestressparameterswerepresentedinTable2.MDA

levelsincreased post trainingand after thechampionship

(P<0.05),CATactivitiesdecreasedafterthechampionship

(P<0.05). SOD activities decreased post training and

after the championship, but these differences were not

significant. GPX activities did not change. The oxidative

stress status changed for both female and maleathletes

(Table2,Figs.1and2).

4.

Discussion

Physicalexerciseisacomplexbiologicalactivitychallenging

homeostasisatthecell,tissue,organandwholebodylevels

[25].There arenumerousreports that providereasonable

supporttothenotionthatexerciseincreasestheproduction

of ROS [26]. Little is known, regarding the extent of

oxidative stress when comparing aerobic and anaerobic

exercisemodes[10].

On theoccurrenceofexercise,stress isnotfullyclear.

However, the principal factor responsible for oxidative

damage during exercise is the increase in oxygen

con-sumption[27],Itappearsthatanaerobictypesofexercise,

whichinvolveslessoxygencirculationthroughoutthebody

thanaerobicexerciseis associatedwithan increasedROS

generationlevel throughotherpathways [8,11]suggesting

thatoxygenconsumptionper seisnotthemajorcauseof

exercise-inducedoxidativedamage[11].

Differenttypesofexercisewouldhavedifferenteffects

onoxidative stress [11] which is definedas asituation in

whichanincreasedlevelofROSgenerationoverwhelmsthe

antioxidantdefensecapacity,resultinginoxidativedamage

tolipids,proteinsandDNA[11,28].

A review of literature on changes in oxidative stress

markersandphysicalparametersfollowingtheMTtraining

and championship indicates a lack of information in this

subjectarea.Forthisreasonweinvestigatedtheoxidative

statusofathletesduringcompetitionseasonbycompleting

HIITprogramandfollowingIMTC.

Field observation has shown that, MT activity is

extremely dynamic in nature and during sparring athlete

repeatedexplosivemovementsatahighintensityfollowed

by sub-maximal work. Thus the primarily energy systems

utilizedaretheanaerobicATP-CPandlacticsystems[17].

Itwasreportedthattheactivitiesofantioxidantenzymes

anacuteboutofexerciseinskeletalmuscle,heartandliver

[3].

SOD,CAT,GPXanMDAactivitiesinresponsetoexercise

arevariable. When we looked at our study, we observed

thatMDAlevelsincreasedintheperiodofposttrainingand

afterthechampionship(P<0.05),CATactivitiesdecreased

afterthechampionship(P<0.05).SODactivitiesdecreased

in the post-training period and after the championship,

but these differences were not significant. GPX activities

didnotchange inall samples.The oxidative stress status

changedforbothfemaleandmaleathletes.Itisconcluded

withtheseresultsthatoxygenradicalswereproducedafter

strenuous physical training and some antioxidant enzyme

activitiesweredecreased.

When oxygen radicals were not scavenged properlyby

antioxidantenzymestheyaffected lipidmolecules incells

andMDAlevelswereincreased.Theseresultssupportedour

hypothesis.Zoppietal.[7]arrivedatthesameconclusion

intheirstudy,suggestingthatantioxidantsupplementation

hadpositiveeffectsonantioxidantcapacityoftheplayers.

Baker et al. [29] reported the increased MDA levels in

high-intensityexercise and supported ourresults. Several

studiesreportedthatsingleboutofexerciseincreaseblood

levelsofMDA [4,14].Higher resting plasmaMDA reported

insprint-trainedathletes comparedwithcontrolsubjects.

Elevated in plasma MDA following an extreme endurance

event in elite athlete also reported [12]. Not all studies

reportedincreases in MDA in response to physical effort.

MiyazakiH.etal. observed nochange in erythrocyte MDA

aftera12-weektrainingprogram[14].

According to the Metin et al. [9] excessive training

can produce oxidative stress and organism’s antioxidant

elements were stimulated with this challenge. This idea

canbeexplainedasanadaptivemechanism.Inevery

condi-tion it is clear that oxygen radicals are produced in the

organismsduringstrenuoustrainingperiods.Forthisreason

nutritionplanningincludingantioxidantsupplementationis

consideredasanimportantmeasureagainstthehazardous

effectsoffreeradicals.

SODisoneofthemainantioxidantenzymesthatdegrade

superoxide radicals [30] increase in SOD enzyme activity

correspondswith enhancedresistance tooxidative stress.

Groussardet al. found that SOD activity decreased after

a single sprint anaerobic exercise [27]. Not all studies

reported decrease in SOD in response to exercise. It has

been reportedthat 8-week moderate intensity of aerobic

trainingdid notelevate SOD activity.Furthermore,it has

beenrevealedadecreaseinSODlevelsfollowingan acute

boutofexerciseinskiersparticipatinginagradedtreadmill

test to exhaustion and elevated erythrocyte SOD activity

immediatelypost-exercisewhenthesprintersperformeda

sprintexercise[12].

CATactivityinresponsetoexerciseisvariable.Following

about of sub-maximalexercise adecreasein erythrocyte

CATactivityreportedintrainedcyclists.

Furthermore, it has been reported that sprinters who

performedasprint-typeexercisedidnothavealtered

ery-throcyteCATactivity[12].

GPXactivityisakeycomponentoftheglutathione

home-ostasisanditsresponsetoexerciseisvariable[28].Higher

inoxygenconsumptionduringexerciseactivatestheenzyme

GPXtoremovehydrogenperoxide.Inresponsetoanacute

bout of high intensity exercise, elevated erythrocyte GPX

activityhasbeenfoundafterasprintexercisebutnochange

whenrunnersperformedanenduranceexercise[12].

The present study is the first to report improvements

in oxidativestatus aftershort-termhighintensity interval

trainingandimmediatelyafterMTcompetition.We

specu-latethat changesintheseparametersmight representan

increaseinROSafterhighintensityintervaltraining.

Incomparisonwithother investigators, webelieve the

presentstudyprovidedthefirstdirectanalysisofeffectof

highintensityintervaltrainingoneliteathletes’antioxidant

statusaftertrainingandcompetition.

Theresultsofthisstudyalsosuggest thatabrief

train-ingcamp,whichtheHIITprogramis carriedoutappearto

causepositivechangesonphysiological parametersdueto

somebiologicalreasonslinkedwithpreparationforhigh

per-formanceandoxidativestatusof MTathletes.However,it

wasobservedthatoxidativedamageincreased.The

recruit-ment of alimited number ofspecial MT athletes wasthe

limitationofourstudy.Furtherstudiesareneededwhether

similaradaptationsaremanifestafteracoupleofweeksof

differenttypeofintervaltraining.Afterthiskindofstudies

thenutritioncomponentofeliteathletescanbearranged

againstoxidativedamage.

Disclosure

of

interest

Theauthordeclaresthathehasnoconflictsofinterest

con-cerningthisarticle.

Acknowledgements

TheauthorwouldliketothankHuseyinG.Sonmez3for

tech-nical assistance, Ayse Eken, Ph.D.4, Onur Erdem, Ph.D.4,

Cemal Akay, Ph.D.4, Ahmet Sayal, Ph.D.4, Ahmet Aydin,

Ph.D.5, and Mesut Akyol, Ph.D.6 for measuring oxidative

stressparameters,andJuliaGoggin7forhelpingwithproof

reading.

References

[1]Forsberg L, de Faire U, Morgenstern R. Oxidative stress, humangeneticvariation,anddisease.ArchBiochemBiophys 2001;389:84—93.

[2]Cooke M, Evans M, Dizdaroglu M, Lunec J. Oxidative DNA damage: mechanisms, mutation, and disease. FASEB J 2003;17:1195—214.

[3]Banarje AK, Mandal A, Chanda D, Chakraborti S. Oxi-dant, antioxidant and physical exercise. Mol Cell Biochem 2003;253:307—12.

3BilkentUniversity,DepartmentofPhysicalEducationandSport,

06800Ankara,Turkey.

4GülhaneMilitary MedicalAcademy,DepartmentofToxicology,

Etlik,06010Ankara,Turkey.

5YeditepeUniversity,FacultyofPharmacy,Departmentof

Toxi-cology,Kayisdagi,34755Istanbul,Turkey.

6GülhaneMilitaryMedicalAcademy,DepartmentofBiostatistics,

Etlik,06010Ankara,Turkey.

7Bilkent University, Faculty Academic English Program, 06800

[4]KoskaJ,Blazicek P,MarkoM,GrnaJD, KvetnanskyR, Oigas M.Insulin,catecholamines,glucoseandantioxidantenzymes inoxidativedamageduringdifferentloadsinhealthyhumans. PhysiolRes2000;49(Suppl.19):S95—100.

[5]JiLL. Free radicalsand exercise:implication inhealth and fitness.JExercSciFitness2003;1(1):15—22.

[6]KanterM.Freeradicals,exerciseandantioxidant supplemen-tation.ProcNutrSoc1988;57:9—13.

[7]ZoppiCC,HohlR,SilvaFC,LazarimFL,NetoJMFA,Stancanneli M,etal.VitaminCandEsupplementationeffectsin profes-sionalsoccerplayers underregulartraining.JIntSocSports Nutr2006;3(2):37—44.

[8]Fisher-WellmanK,BloomerRJ.Acuteexerciseandoxidative stress:a30-yearhistory.DynMed2009;8(1):1—25.

[9]MetinG,GumustasMK,UsluE,BelceA,KayseriliogluA.Effects ofregulartrainingonplasmathiols,malondialdehydeand car-nitineconcentrations inyoungsoccerplayers.ChinJPhysiol 2003;46(1):35—9.

[10] BloomerRJ,SmithWA.Oxidativestressinresponsetoaerobic andanaerobicpowertesting:Influenceofexercisetrainingand carnitinesupplementation.ResSportsMed2009;17:1—16. [11] ShiM, Wang X, Yamanaka T, Ogita F,Nakatani K, Takeuchi

T. Effects of anaerobic exercise and aerobic exercise on biomarkers of oxidative stress. Environ Health Prev Med 2007;12:202—8.

[12] UrsoML,ClarksonPM.Oxidativestress,exerciseand antioxi-dantsupplementation.Toxicology2003;189:41—5.

[13] BelviranlıM,GokbelH.Acuteexerciseinducedoxidativestress andantioxidantchanges.EurJGenMed2006;3(3):126—31. [14] MiyazakiH,Oh-ishiS,OokawaraT,KizakiT,ToshinaiK,HaS,

etal.Strenuousendurancetraininginhumansreduces oxida-tivestress following exhaustingexercise. EurJApplPhysiol 2001;84:1—6.

[15] PepeH,BalciSS,RevanS,AkalinPP,KurtogluF.Comparison ofoxidativestressandantioxidantcapacitybeforeandafter runningexercisesinbothsexes.GendMed2009;6(4):587—95. [16] Sureda A, Tauler P, Aguilo A, Cases N, FuentespinaE, Cor-dovaA,etal.Relationbetweenoxidativestressmarkersand antioxidantendogenousdefensesduringexhaustiveexercise. FreeRadicRes2005;39(12):1317—24.

[17] McArdleWD,KatchFI,KatchVL.Nutritionforphysicalactivity. Exercise training and functional capacity. In: McArdle WD,

KatchFI,KatchVL,editors.Essentialsofexercisephysiology. 1stedPhiladelphia:LeaandFebiger;1994.

[18]MyersTD,BalmerNJ,NevillAM,NakeebY.Evidenceof nation-alisticbiasinMuayThai.JSportsSciMedCSSI2006:21—7. [19]NunanD.Developmentofasportsspecificaerobiccapacitytest

forkarate—apilotstudy.JSportsSciMedCSSI2006:47—53. [20]VollaardNB,ShearmanJP,CooperCE.Exercise-induced

oxida-tivestress:myths,realitiesandphysiologicalrelevance.Sports Med2005;35(12):1045—62.

[21]FoxEL,BowersRW,FossML.Methodsofphysicaltraining.In: FoxEL,BowersRW,FossML,editors.Thephysiologicalbasis for exercise and sport.4thed.New York:SoundersCollege Publishing;1988.

[22]ClementD,DavidsonR,MathesonGO,NewhouseI,SawchukL, CoxD,etal.Issuesspecifictowomen.In:JacksonR,FitchK, O’BrienM,editors.Sportsmedicinemanual.1sted.Canadian CataloguinginPublishingData:Calgary;1990.

[23]AydinA,HilmiO,SayalA,OzataM,SahinG,IsimerA. Oxida-tive stress and nitric oxide related parameters in type II diabetesmellitus:effects ofglycemiccontrol.ClinBiochem 2001;34:65—70.

[24]AebiH.Catalaseinvitro.MethodsEnzymol1984;105:121—6. [25]Ji LL, Radak Z, Goto S. Hormesis and exercise: how the

cell copes with oxidative stress. Am J Pharmacol Toxicol 2008;3(1):44—58.

[26]PackerL,CadenasE,DaviesKJA.Freeradicalsandexercise: anintroduction.FreeRadicBiolMed2008;44:123—5. [27]GroussardC,Rannou-BekonoF,MacheferG,ChevanneM,

Vin-centS,SergentO,etal.Changesinbloodlipidperoxidation markersandantioxidantsafterasinglesprintanaerobic exer-cise.EurJApplPhysiol2003;89:14—20.

[28]KinnunenS, AtalayM,HyypaS, LehmuskeroA,Hanninen O, Oksala N. Effects of prolonged exercise on oxidative stress andantioxidantdefenseinendurancehorse.JSportsSciMed 2000;4:415—21.

[29]Baker JS,Bailey DM, Hullin D,Young I,Davies B.Metabolic implications of resistiveforce selection for oxidative stress and markers ofmuscle damage during30s of high-intensity exercise.EurJApplPhysiol2004;92(3):321—7.

[30]QiaoD,HouL,LiuX.Influenceofintermittentanaerobic exer-ciseonMousephysicalenduranceandantioxidantcomponents. BrJSportsMed2006;40:214—8.