SPEED AND ACCURACY DEVELOPMENT IN PRAGMATIC COMPREHENSION OF STUDENTS OF SCHOOL OF FOREIGN LANGUAGES AT PAMUKKALE UNIVERSITY

by

GÜLER EKİNCİER

In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of MASTERS OF ARTS

in

THE DEPARTMENT OF

TEACHING ENGLISH AS A FOREIGN LANGUAGE GAZI UNIVERSITY

ANKARA

Güler EKİNCİER‘in “Speed and Accuracy Development in Pragmatic Comprehension of Students of School of Foreign Languages at Pamukkale University” başlıklı tezi 09/12/2009 tarihinde, jürimiz tarafından İngilizce Öğretmenliği Ana Bilim Dalında Yüksek Lisans Tezi olarak kabul edilmiştir.

Adı Soyadı İmza

Üye (Tez Danışmanı): Yard. Doç. Dr. Cemal ÇAKIR ...

Üye : Yard. Doç. Dr. Hüseyin ÖZ ...

SPEED AND ACCURACY DEVELOPMENT IN PRAGMATIC

COMPREHENSION OF STUDENTS OF SCHOOL OF FOREIGN LANGUAGES AT PAMUKKALE UNIVERSITY

Ekincier, Güler

M. A., Department of Teaching English as a Foreign Language Supervisor: Assist. Prof. Dr. Cemal Çakır

September 2009

The purpose of the present study is to investigate to what extent Turkish upper-intermediate level learners of English as a foreign language (EFL) can comprehend implied meaning and their speed in comprehension of these implicatures. To this end, 60 participants at Pamukkale University, School of Foreign Languages first completed a 10-item multiple-choice test programmed into computers. The scores of the participants in pre-test and post-test were compared, and analysed according to descriptive and inferential statistics. Also, this study examined development of pragmatic comprehension ability across time with this test measuring ability to comprehend implied meaning (implicatures) in dialogues. The participants’ comprehension was analyzed for accuracy and comprehension speed (average time taken to answer each item correctly). The learners’ accuracy and comprehension speed improved significantly over a 8-week period. However, the magnitude of effect was lower for comprehension speed than for accuracy. Accuracy level bore no relationship to comprehension speed, which means accuracy and comprehension speed were not related to each other.

In summary, foreign language learners’ pragmatic comprehension in implicatures is analysed with a view to see whether pragmatic comprehension accuracy and speed improve over time and increase learner consciousness in these areas. It should be noted that the features of the learners in relation to their implicature perception are outside the scope of this investigation. It is hoped to contribute to the pragmatics research by uncovering the implicature comprehension development of Turkish

processing capacity of using the knowledge may not coincide perfectly in foreign language development.

PAMUKKALE ÜNİVERSİTESİ YABANCI DİLLER YÜKSEKOKULU İNGİLİZCE HAZIRLIK BİRİMİ ÖĞRENCİLERİNİN EDİMBİLİMSEL

ANLAMADA HIZ VE DOĞRULUK DÜZEYLERİNİN İNCELENMESİ

Ekincier, Güler

Yüksek Lisans, İngiliz Dili Eğitimi Bölümü Danışman: Yrd. Doç. Dr. Cemal Çakır

Eylül 2009

Bu çalışmada orta-üstü düzeyde İngilizce bilen öğrencilerin hedef dilde edimbilimsel anlamada hız ve doğruluk oranları ve bunlar arasındaki ilişki araştırılmıştır. Öncelikle 10 soruluk çoktan-seçmeli bilgisayar ortamında hazırlanmış bir ölçek aracılığıyla Pamukkale Üniversitesi Yabancı Diller Yüksekokulu öğrencisi olan 60 katılımcının hedef dilde edimbilimsel anlamadaki hız ve doğruluk düzeyleri ön-test ve son-test olarak iki ayrı zamanda ölçülmüştür. Elde edilen sonuçlardan ön-test ve son-test arasındaki ilişki ve ölçek aracılığıyla elde edilen veriler betimleyici, yorumlayıcı bir şekilde incelenmiştir. Ayrıca, bu çalışmayla, çoktan seçmeli testte kullanılan diyaloglarda geçen sezgisel ifadeleri edimbilimsel anlamada, katılımcıların zamanla gelişim gösterip göstermedikleri incelenmiştir. Doğruluk oranları her soruya verdikleri doğru cevapla, hız oranları ise bir soruya cevap vermek için harcadıkları zamanla ilişkilidir. Katılımcıların edimbilimsel ifadeleri doğru anlama ve anlama hızları 8 haftalık bir zaman diliminde gelişme göstermiş; fakat oranlandığında bu gelişimin hızda, doğruluk oranına göre daha düşük olduğu gözlemlenmiştir. Ayrıca, anlama hızı ile doğru anlama arasında doğru bağlantılı bir ilişki kurulamamıştır.

Özetle, İngilizce’yi yabancı dil olarak öğrenen katılımcıların edimbilimsel anlamadaki hız ve doğruluk düzeylerinin incelenmesi ve 8 haftalık bir sürede gelişim gösterip göstermemesi amacıyla yola çıkılan bu çalışmada, katılımcıların

çalışmanın kapsamına alınmamıştır. Yapılan çalışma sonucunda, bulgular katılımcıların edimbilimsel anlama becerilerinin genel olarak orta üstü durumda olduğunu göstermiştir.

This work would not have been possible without the support and encouragement of my colleague and friend, Özlem Yolcusoy, under whose supervision I began the thesis. I am heartily thankful to my advisor, Cemal Çakır, whose encouragement, guidance and support from the initial to the final level enabled me to develop an understanding of the subject.

Naoko Taguchi, in the first stages of the work, has also been abundantly helpful, and has assisted me in numerous ways, including summarizing the implications of the topic and some ideas which were not available for me to examine, and in particular for allowing me to read the extracts.

Turan Paker, Tamer Sarı and Seçil Çakır deserve special thanks as my supporters. In particular, I would like to thank them for askingwhether the research was going well, which was encouraging.

All my library buddies at Gazi, Hacettepe, Bilkent and Pamukkale University made it a convivial place to work. I thank all other folks who had inspired me in research and life through our interactions during the long hours at cafes.

I cherished the support from my class-mates At Gazi MA TEFL program. I treasured all precious moments we shared and would really like to thank them. I cannot end without thanking my mother, on whose constant encouragement and love I have relied throughout my time. Her unflinching courage and conviction will always inspire me.

ABSTRACT ……… i

ÖZET ……… iii

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS ……… v

TABLE OF CONTENTS………... vi

CHAPTER ONE: INTRODUCTION ………. 1

1.1. General Background to the Study ……… 1

1.2. Aim of the Study ……….. 6

1.3. Scope of the Study ……… 7

1.4. Significance of the Study ………. 7

1.5. Limitations of the Study and Directions for Future Research 8 1.6. Organization of the Chapters ……… 9

1.7. Definitions of Key Terms ………. 10

1.8. List of Abbreviations ……… 12

CHAPTER TWO: REVIEW OF LITERATURE ………... 13

2.1. Introduction ………. 13

2.2. Comprehension versus Production ………. 21

2.3. Pragmatic Considerations in Language Learning ………… 23

2.4. Implied Meaning and Foreign Language Learning ………. 26

2.5. Grice’s Theory of Co-operative Principle ……… 28

2.6. Non-observance of Conversational Maxims ……… 31

2.7. Properties of Implicatures ……… 32

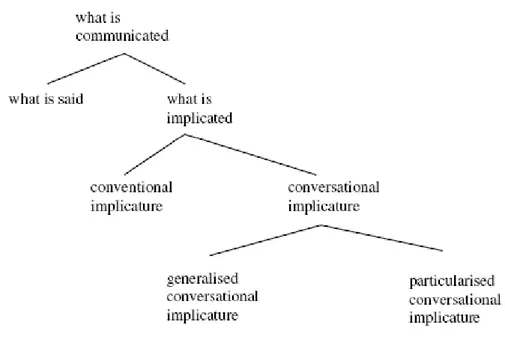

2.8. Classification of Implicatures ……….. 34

2.8.1. Conventional Implicatures ………. 35

2.8.2. Conversational (non-conventional) Implicatures …. 36

2.9. Comprehension of Implicatures ……….. 38

2.10. Relevance Theory ……… 39

2.11. Other Approaches to Implicatures ……….. 41 2.12. Interlanguage Pragmatics Studies Pertaining to Implicatures 42

CHAPTER THREE: METHOD OF RESEARCH ……….. 49

3.1. Introduction ……….. 49

3.2. Research Question ……… 49

3.3. Research Design ………... 49

3.4. Participants ……… 50

3.5. Data Collection Instrument ……….. 50

3.6. Data Collection Procedures and Analysis ……… 52

3.7. Analysis of Implicature Comprehension Data ………. 52

CHAPTER FOUR: RESULTS AND DISCUSSIONS ………. 53

4.1. Introduction ………. 53

4.2. Development of Pragmatic Comprehension Ability ……… 53

4.3. Discussion ……… 55

CHAPTER FIVE: CONCLUSION AND IMPLICATIONS FOR ENGLISH AS A FOREIGN LANGUAGE LEARNERS ………. 59

5.1. Introduction ……….. 59

5.2. Discussion ………. 59

5.3. Implications of the Findings for English as a Foreign Language 60 5.4. Recommendations for Future Research ……… 64

5.5. Summary ……….. 65

REFERENCES ……….. 66

APPENDIX ……….. 81

Implicature Comprehension Instrument ……… 81

CHAPTER I

INTRODUCTION

1.1. General Background to the Study

Understanding language in communicative context is a complex process, and the comprehension of utterances is affected by various factors. Pragmatic or contextual information has a significant role in determining what a speaker wants to convey and what the listener needs to comprehend (Blakemore, 1992; Ervin-Tripp, 1996; Gibbs and Moise, 1997; Sperber & Wilson, 1995). In the study of communication, context is usually conceived as an extensive and multidimensional concept which includes cognitive and social dimensions as well as linguistic, physical, and other non-linguistic features (Sperber and Wilson, 1995). Context can be said to encompass all the information that the hearer utilizes when he/she interprets language expressions. World knowledge is a very important part of context (Mercer, 2000; Sperber and Wilson, 1995). The same expression can have a different meaning in a different communicative situation; by exploiting context it is possible to understand the speaker’s intention. Hence, effective uses of pragmatic language involve the processing of contextual information. How do young children fare with these communicative demands? To date, evidence from English-learning preschoolers points to developmental changes during the preschool years (e.g., Leinonen, Ryder, Ellis and Hammond, 2003; Ryder and Leinonen, 2003).

Research into pragmatic development in other languages has been scarce, and it remains an open question whether the results relating to the performance of English children can be generalized to other cultural settings (Adams, 2002).

The growing emphasis on the non-grammatical features of language ability continues with Bachman’s (1990: 84) broader model dividing language competence into pragmatic and organisational components. Unlike Canale and Swain’s model, this model represents pragmatic competence independently

rather than as a subsection of sociolinguistic competence. Thus, the role of pragmatic ability as a crucial constituent of language ability has been brought into limelight in the communicative competence paradigms. Although this does not signify the underestimation of grammar, it is evident that grammatical competence in itself does not ensure a parallel level of pragmatic competence – the ability to use language in a socially appropriate way in relation to the context. As Bardovi-Harlig (1996: 21) demonstrates, a learner of high grammatical proficiency will not necessarily show high pragmatic competence. In line with this, Jianda (2006) reports: “Students with high TOEFL [Test of English as a Foreign Language] scores do not seem to have correspondingly high pragmatic ability” (p.17).

What is more, following the recent emphasis on sociolinguistic and pragmatic aspects of communicative language competence, current foreign language teaching and research focus on the development of learners’ functional and sociocultural use of language in a variety of contexts. Pragmatic competence, the ability to perform language functions in context, has received much interest as an important aspect of communicative ability. Within the construct of pragmatic competence, comprehension of pragmatic meaning is a growing area of interest in the field of foreign language learning (Taguchi, 2005). Pragmatic comprehension involves understanding meaning at two different levels: utterance meaning, or assigning sense to words uttered, and force, or the speaker’s intention behind the words (Thomas, 1995). A growing number of L2 studies have examined the ability to comprehend speakers’ intentions that are not explicitly stated (Carrell, 1984; Garcia, 2004; Hohgraves, 2007; Kasper, 1984; Rover, 2005; Takahashi & Roitblat, 1994; Taguchi, 2005, 2007). These studies reveal that successful comprehension of implied meaning or pragmatic speech depend on the levels of indirectness encoded in the utterances as well as learners’ general proficiency of English. As their proficiency develops, learners become able to comprehend a range of conventional and nonconventional implicatures. Although a direct relationship

between proficiency and pragmatic comprehension is established the literature so far, the majority of the studies use a cross-sectional design and are confined to snap-shot descriptions of learners’ pragmatic comprehension at a given point of time (Taguchi, 2005). Very few studies have employed a longitudinal design and addressed the process of development (i.e., how learners proceed from beginning stage to intermediate and advanced stages of pragmatic comprehension). As a result, many questions remain unanswered, including the patterns of pragmatic development and the factors that influence that development. Only a handful of studies to date have used a pretest and posttest design and investigated the longitudinal development of pragmatic comprehension (Taguchi, 2007). In Bouton’s (1992, 1994) in Taguchi (2007) studies, the learners complete a written test that have 33 short dialogues including different types of implicature. In the first study, Bouton found that the learners’ comprehension of relevance-based implicatures becomes nativelike after 4.5 years, but their comprehension of formulaic implicatures show less profound development. Taguchi (2007) examines the development of the comprehension of indirect refusals and opinions among Japanese learners of English as a foreign language (EFL). Indirect refusals are considered conventional because they follow a common, routinized discourse pattern (i.e., giving a reason for refusal), as shown in the empirical data (e.g., Beebe et al., 1990; Nelson et al., 2002). In contrast, expressions used to convey opinions indirectly are considered less conventional because meaning is not attached to specific linguistic expressions or language use patterns (e.g., indicating a negative opinion of a gift by saying “The wrapping paper was OK.”). The data reveal that comprehension is faster and more accurate for indirect refusals than for indirect opinions. The size of gain is much larger for accuracy than it is for speed. Accuracy correlates with general proficiency as measured by TOEFL, but speed does not. Accuracy and speed are not related to each other. In addition, because the target population in Taguchi’s study is foreign language learners, in order to confirm the generalizability of the findings the participant sample

should be expanded to learners in a target language environment. Finally, the development of pragmatic comprehension should be analyzed separately for accuracy and processing speed because, as documented in Taguchi, the degree of development differs between these two attributes. Speed shows distinct characteristics, independent of general English proficiency or accuracy of comprehension. It suggests that analysis of accuracy and speed combined could provide more meaningful developmental accounts of pragmatic comprehension. The distinction between accuracy and processing speed has been much discussed in the field of cognitive psychology, as represented in several models of skill acquisition. One of the well-known models of skill acquisition, namely Anderson’s Adaptive Control of Thought (ACT), claims that skill acquisition involves a transition from the stage of declarative knowledge to the stage of procedural knowledge (Anderson, 1983; Anderson & Lebiere, 1998). Declarative knowledge refers to the knowledge of “what,” which is conscious and analyzable. Procedural knowledge refers to the knowledge of “how” and involves the state in which one’s knowledge is executed in actual behaviors. Skill acquisition is a process in which declarative knowledge becomes proceduralized via an associative stage where rules are practiced repeatedly in a consistent manner. The end point of skill acquisition is characterized as a stage where rules are executed unconsciously and automatically. Speed is a metric of the extent to which declarative knowledge is proceduralized, whereas accuracy is a general measure of declarative knowledge (Segalowitz, 2001, 2003). The distinction between accuracy and processing speed in skill acquisition parallels Bialystok’s (1990, 1993) theoretical model of L2 pragmatic acquisition, which claims that acquisition of pragmatic competence involves acquiring efficient and speedy control over pragmatic knowledge. Her two dimensional model distinguishes between analysis of knowledge and control of processing. Analysis of knowledge refers to the ability to structure and organize linguistic knowledge, whereas control of processing means the ability to access the knowledge in real time. Efficient processing capacity enables us to focus attention on the relevant

part of linguistic information and to select, coordinate, and integrate information in real time, which eventually leads to a performance that appears fluent and effortless. These theoretical claims emphasize the importance of separate analysis for accuracy and processing speed in the development of pragmatic comprehension. Pragmatic acquisition has two complementary aspects: accurate demonstration of pragmatic knowledge and efficient processing of that knowledge. In pragmatic comprehension, learners require pragmatic knowledge that encompasses a wide range of properties, including linguistic knowledge, knowledge of Gricean (Grice, 1975) maxims of conversation (i.e., assumption of relevance), conventions of language use, and sociocultural norms of interaction. Some parts of the knowledge bases are subject to conscious learning. For instance, in order to comprehend indirect utterances, learners need to know the vocabulary and grammar of the utterances, as well as culturally specific forms, conventions, and rules of pragmatic language use that accompany the utterances. According to Bialystok (1990, 1993), adult L2 learners already have concepts of pragmatic functions such as speech acts and implicatures from their native language; they know how to convey thoughts politely or how to interpret indirect meaning in L1. The problem for adults is to relearn the form-function relations appropriate to L2, which entails learning new expressions and conventions, as well as the social conditions and contexts in which they occur. Whereas some pragmatic and linguistic knowledge requires conscious learning, other knowledge bases are directly transferable from L1. For instance, the presumption of relevance is considered part of basic human communication and is directly present in both L1 and L2 processing. Also, when norms and conventions are shared between L1 and L2, meaning could be understood almost as formulaic, as long as learners have sufficient linguistic ability to comprehend the utterances (Sperber and Wilson, 1995). Based on these claims, accuracy in pragmatic comprehension is considered as a general measure of underlying knowledge bases that are either newly learned in target language or transferred from our mother language. Speed in pragmatic comprehension, on the other

hand, is a property of general skill execution. It is an indication that the knowledge bases have been proceduralized through extensive practice and use, and learners have acquired efficient and speedy control over the knowledge. Developmental analyses of accuracy and speed combined will be valuable because it will help reveal whether the two dimensions—the acquisition of pragmatic knowledge and the achievement of automatic control in processing the knowledge—develop in a parallel manner and jointly characterize the course of pragmatic development.

In summary, longitudinal development of pragmatic comprehension can be operationalized at two different levels: the accurate demonstration of pragmatic knowledge (i.e., knowledge of how to interpret implied speakers’ intentions in context) and processing capacity of the knowledge (i.e., the speed with which learners access and process pragmatic information). Given this broad operationalization, development of pragmatic comprehension is potentially affected by a number of component variables, both cognitive and contextual. The analysis of pragmatic gains in relation to those variables will help reveal what factors influence the development of accurate and speedy pragmatic comprehension and whether these factors jointly affect the course of pragmatic development. In the light of these, it can be deduced that pragmatic inferencing is a complex mechanism, which is not thoroughly illuminated as yet. For now, it remains to be identified as a default skill in native speakers of a language.

1.2. Aim of the Study

Based on the gaps in the existing literature, this study investigates the ability to comprehend implied meaning among learners of English as a foreign language. The purpose of the study is to examine the development of accuracy and comprehension speed across time. The research question of this study is:

(1) Does foreign language learners’ ability to comprehend implied meaning improve over time, in terms of accuracy and speed of comprehension?

1.3. Scope of the Study

With the aim of contributing to the expanding ILP research, throughout the present study the focus will be on the comprehension of implied meanings – specifically implicatures – in English as a foreign language. Furthermore, foreign language learners’ pragmatic comprehension in implicatures will be analysed with a view to see whether pragmatic comprehension accuracy and speed improve over time and increase learner consciousness in these areas. The study is descriptive in nature and inquires into the development of EFL learners’ implicature comprehension. It should be noted that some other features of the learners in relation to their implicature perception are outside the scope of this investigation. This study hopes to contribute to the pragmatics research by uncovering the implicature comprehension development of Turkish EFL learners.

1.4. Significance of the Study

Despite the fact that implicature is a universal phenomenon, the presence of cultural differences is inevitable and can potentially impede native-nonnative speaker communication severely. Studies pertaining to the comprehension aspect of pragmatics display cross-cultural variance. This may pose a potential threat to intercultural communication. Thus, whether Turkish learners face difficulty in pragmatics comprehension due to cultural causes is a significant question to be answered. What is more, based on the results of this study, EFL teachers may incorporate instruction of pragmatic aspects of the target language, which may be useful in promoting EFL learners’ communicative comprehension. Hence not only learning the language but also learning about the sociocultural norms of the target language speakers is considered to be useful for EFL learners. Furthermore, interpretation of implied meanings is assessed in worldwide acknowledged proficiency tests as an indicator of listening competence. As Kostin (2004: 27) reports, “the need to draw an inference beyond what is

explicitly stated in the dialogue” is one of the most difficult tasks awaiting non-native learners of English in TOEFL.

1.5. Limitations of the Study and Directions for Future Research One major limitation in this study is the homogeneity of the participant population. Because the participants are limited to young adult Turkish EFL learners of Pamukkale University, School of Foreign Languages, findings cannot be generalized to different groups of English language learners. This study was applied to only EFL learners. However, without comparative groups of ESL learners or learners in a traditional English class, the precise contextual factors that affect the development are not clear. Compared with EFL learners, ESL learners are potentially more often exposed to everyday out-of-class practice in inferential comprehension, and have more out-of-class associative practices between input and meaning. Therefore, when overall L2 proficiency is controlled, ESL learners might perform pragmatic functions better and faster than EFL learners who have limited exposure to target input outside the classroom. Similarly, it is possible that ESL learners in an intensive program receive rich, condensed, in-class input that promotes general language skills, and that EFL learners in a regular university class receive a limited amount of in-class input that is distributed over months. Thus, the intensive format of classroom practice may contribute to accurate and speedy comprehension of implied meaning. However, without data from ESL and EFL learners in a traditional instructional setting, this study is not able to make such comparisons. To overcome these limitations, future research should examine pragmatic comprehension over a wider range of instructional environments. Another limitation of this study relates to the limited number of data collection sessions. Because this study compares performance gains between the beginning and end of the 8-week session, the study does not capture the incremental developmental trend over an extended period of time. Such longitudinal analysis is important, particularly because the size of speed gain is smaller than that of accuracy gain.

Future research should incorporate more frequent observations and monitor students’ progress for a longer period of time. The results imply that there may be other cognitive and non-cognitive variables that affect processing speed. For instance, speed might be affected by individual processing strategies. Some learners might activate multiple interpretations of non-literal meaning and choose the most plausible one after closely evaluating them, and others might jump to the most accessible interpretation without considering other options. Therefore, it remains for future research to identify other processing related factors, both cognitive and non-cognitive, that could influence the development of speed in pragmatic comprehension.

1.6. Organization of Chapters

The present thesis comprises five chapters, in the first of which the background and statement of the problem studied are detailed. The significance and the limitations of the study in the domain of pragmatics are also explained in this part. In Chapter 2, a more comprehensive review of the literature is provided in order to elaborate on the theoretical basis of the study. The main issues addressed in this section are communicative and pragmatic competence, interlanguage pragmatics, theories of implicature, and the Gricean framework. In Chapter 3, the design of the research is presented. The findings obtained after the implementation of the research steps and the interpretations based on them are documented in Chapter 4. In the final chapter, a discussion of the results and some pedagogical implications are presented. Lastly, recommendations for future research are provided.

1.7. Definitions of Key Terms

Cooperative principle (CP): A basic assumption in conversation that each participant will attempt to contribute appropriately, at the required time, to the current exchange of talk (Yule, 1996: 128).

Conventional implicature: Implicit meaning that can be conventionally inferred from forms of expression in combination with assumed standard adherence to conversational maxims (Verschueren, 1999: 34).

Conversational implicature: Implicit meaning inferred from the obvious flouting of a conversational maxim in combination with assumed adherence to the CP (Verschueren, 1999: 34).

Inference: Any conclusion that one is reasonably entitled to draw from a sentence or utterance (Hurford & Heasley, 1983: 279). The listener’s use of additional knowledge to make sense of what it is not explicit in an utterance (Yule, 1996:131).

Implicature: A nonlogical inference constituting part of what is conveyed by S[peaker] in uttering U within context C, without being part of what is said in U. (MIT Encyclopaedia, 2004)

Implicit meaning: The general term for a range of meanings emerging from the contextually embedded action character of speech (Verschueren, 1999: 25).

Interlanguage pragmatics: a subfield of pragmatics which studies the ways in which context contributes to meaning in terms of the utterances in the target language to convey the same message made by the native speaker of that language.

Generalized conversational implicature: An additional unstated meaning that does not depend on special or local knowledge (Yule, 1996: 130).

Maxims of conversation: Intuitive principles which are supposed to guide conversational interaction in keeping with a general Co-operative Principle.

Particularized conversational implicature: An additional understated meaning that depends on special or local knowledge (Yule, 1996: 132).

Pragmatics: The study of language use, the study of language phenomena from the point of view of their usage properties and processes (Vershueren, 1999: 1).

Pragmatic competence: Knowledge of the linguistic resources available in a given language for realizing particular illocutions, knowledge of the sequential aspects of speech acts and finally, knowledge of the appropriate contextual use of the particular languages' linguistic resources (Barron, 2003: 10)

Scalar implicature: An additional meaning of the negative of any value higher on a scale than the one uttered, e.g. saying ‘some children’, I create an implicature that what I say does not apply to ‘all children’ (Yule, 1996: 134).

Speech act: A communicative activity defined with reference to the intentions of a speaker while speaking and the effects achieved on a listener (Crystal, 2001: 314).

1.8. List of Abbreviations

CC Communicative Competence CEF Common European Framework CP Co-operative principle

EFL English as a Foreign Language EIL English as an International Language ESL English as a Second Language

ICI Implicature Comprehension Instrument ICC Intercultural Communicative Competence ILP Interlanguage Pragmatics

L1 Native Language

L2 Second Language / Foreign Language GCI Generalized Conversational Implicature NS Native Speaker

NNS Non-native speaker

PCI Particularized Conversational Implicature RT Relevance Theory

TEFL Teaching of English as a Foreign Language TOEFL Test of English as a Foreign Language TL Target language

CHAPTER 2

REVIEW OF LITERATURE 2.1. Introduction

Second language acquisition (SLA) has much discussed communicative competence, as stated by the emergence of several models (Bachman & Palmer, 1996; Canale & Swain, 1980). Pragmatic competence has been situated as a distinct, indispensable component of communicative competence by these models, emphasizing functional and context-dependent language use. Pragmatic competence, assumed in the roles of the speaker and listener in interaction, refers to the ability to produce meaning in a socially appropriate manner and to interpret meaning, explicitly or implicitly stated, according to contexts (Thomas, 1995). It involves being able to use language in interpersonal relationships, taking into account such complexities as social distance and indirectness. Pragmatic ability, which is an important part of the language proficiency construct (Canale, Canale and Swain, in Bachman, 1990), is the ability to use language appropriately according to the communicative situation. The importance of the pragmatic dimension in the language ability construct is not disputed; however, its role in interlanguage development has only recently begun to be researched empirically, particularly within the aspect of comprehension (Bardovi-Harlig, 1999; Kasper & Rose, 1999). Pragmatic competence refers to the comprehension of oral language in terms of pragmatic meaning. English language learners need to be able to comprehend meaning pragmatically in order to:

• understand a speaker's intentions;

• interpret a speaker's feelings and attitudes;

• differentiate speech act meaning, such as the difference between a directive and a commissive;

• evaluate the intensity of a speaker's meaning, such as the difference between a suggestion and a warning;

• be able to respond appropriately.

With the recognition of the role of pragmatic competence in communicative ability, a lot of second language (L2) research has analyzed learners’ pragmatic performance in communicative contexts. In the existing L2 or EFL literature, pragmatic competence has been analyzed mainly from production skills, specifically production of speech acts. Little L2 research has investigated comprehension of pragmatic functions (Kasper & Rose, 2002: 79). Moreover, research has not substantially studied issues related to developmental aspects or relationships of pragmatic competence with general L2 proficiency and other cognitive and noncognitive variables. According to Thomas (1995: 57), meaning has two levels: utterance meaning, or assigning sense to the words uttered; and force, or speakers’ intention behind the words. Pragmatic comprehension entails understanding meaning at both levels. It involves the ability to understand what words and sentences mean, as well as to understand what speakers mean by them. Therefore, comprehension of implied meaning, namely, meaning “that goes beyond what is given by the language form itself or what is literally said” (Verschueren, 1999: 25), is an important aspect of comprehension ability. Grice (1975: 162) explains the comprehension process of implied meaning by using a notion of conversation maxims, or rules of communication. The conversation maxims enable people to interpret implicit meaning, such as in B’s response: A: I’m really thirsty.

B: There is a market around the corner.

The listener B in this dialogue makes an appropriate comment to A and A draws the conclusion that the market has water. Implied meaning is understood based on the assumption that the speaker operates under the cooperative principle as well as the listener’s ability to supply contextual information to make inferences from seemingly unrelated utterances. Sperber and Wilson (2004: 608) used relevance theory to extend Grice’s insight and claimed that communication is achieved by interpreting contextual cues and using them to infer speaker intention. Contextual cues include not only such external factors as physical

environment or the immediately preceding discourse, but also internal factors such as one’s knowledge about the world, conventions, and experiences. Relevance Theory also emphasizes the relation between context and processing effort. The theory argues that implicatures vary in their degree of strength; some implicatures are strongly conveyed, but others are weakly understood because of the number of contextual cues to be processed (Sperber and Wilson, 2004). The greater the number of contextual cues to be processed, the more extensive the search for meaning becomes, resulting in greater processing effort. One factor that could reduce processing effort is the level of conventionality encoded in utterances. When implicatures convey conventional meaning, that is, when speaker intentions are linguistically coded or embedded within predictable, fixed patterns of discourse, the listener may not attend to many contextual cues, consequently reducing the processing effort. A relatively small number of L2 studies have examined whether learners can comprehend implied meaning accurately (Bouton, 1992, 1994, 1999; Cameron & Williams, 1997; Carrell, 1981, 1984 in Cook & Liddicoat, 2002; Garcia, 2004; Kasper, 1984; Koike, 1996 in Röver, 2005; Takahashi & Roitblat, 1994; Taguchi, 2002, 2003; Ying, 1996). Some studies examined the ability to comprehend implicit meaning in relation to L2 proficiency and the degree of directness or conventionality encoded in utterances. Cook and Liddicoat (2002) examined L2 comprehension of requests of various types. ESL learners of two proficiency levels responded to a written questionnaire that contained brief scenarios followed by a requestmaking expression. The expressions had three directness levels: direct (e.g., Pass me the salt), conventional indirect (e.g., Can you pass me the salt?), and nonconventional indirect (e.g., Are you putting salt on my meat?). The high proficiency learners had difficulty in understanding nonconventional indirect forms, and the low proficiency group had difficulty with both indirect forms. Results suggest a difference in comprehension difficulty among different types of expressions. Nonconventional indirect requests were difficult to comprehend even for the high proficiency learners, but conventional expressions were not. As

FL proficiency develops, learners are able to comprehend a winder range of indirect expressions. Taguchi (2002) also documented different difficulty levels across implied meaning types. Eight Japanese ESL learners at two different proficiency levels listened to dialogues that contained three types of indirect utterances: indirect refusals, indirect disclosure of information, and indirect expression of opinions. The results showed that higher proficiency learners more accurately comprehended implied speaker intentions than lower proficiency learners. Retrospective verbal reports revealed that comprehension of refusals required less effort; learners used fewer strategies to interpret indirect refusals than the other. Morgan (1978) defines conventionality as “common knowledge of the way things are done” (p. 279) that encompasses both knowledge of language and language use. Morgan calls some indirect speech acts short-circuited implicatures, meaning that they are types of implicatures that do not require extensive inferencing because the listener understands the intended meaning based on conventions of language and language use, and does not have to process a great number of contextual cues. Implied expressions may stem from different levels of conventionality encoded in the utterances and more research is needed to enlighten these different types of conventions.

In summary, a few previous studies have documented that successful comprehension of implied meaning or implicatures depend on the degree of processing effort required for comprehension, as well as learners’ general language proficiency. What is not examined systematically relates to the developmental aspect of pragmatic comprehension. Only one study to date has examined development of pragmatic comprehension using a pretest and posttest design. Bouton (1992, 1994) investigated L2 learners’ comprehension of conversational implicatures. ESL learners took a test that had short written dialogues including different types of implicatures. The results showed that learners’ overall comprehension improved over time along with the length of residence in the target language country. However, learners showed much less pronounced development for formulaic implicatures that had typical structural

and semantic features (e.g., showing agreement by saying Is the pope Catholic?). Building on Bouton’s work, whether the ability to understand implied meaning develops over time, and what factors influence the development should be examined. Because Bouton did not directly address the difference in comprehension load in relation to the differential degree of conventionality among implied meaning types, integration of conventionality could provide useful insights into the nature and development of pragmatic comprehension ability. Another gap in the previous research is that most studies on pragmatic comprehension have analyzed comprehension accuracy, namely the knowledge dimension of pragmatic ability, and only a few studies to date have addressed the speed of pragmatic comprehension, an aspect of the processing dimension of pragmatic ability. As Segalowitz (2001, 2003) claims, fluency – speed and ease of language processing – belongs to Implicatures tested in Bouton’s studies include relevance-based implicatures (violation of Grice’s relevance maxim), Pope implicatures (violation of Grice’s relevance maxim), indirect criticism (violation of Grice’s quality maxim), sequence-based implicatures, irony, scalar implicatures, and indirect criticism. Learners’ cultural knowledge and language background affected comprehension ability. Korean, Japanese, and Chinese speakers showed significantly poorer comprehension ability than German, Spanish, and Portuguese speakers in the study of performance. The study of fluency should provide an alternative way to characterize language acquisition because rapid, effortless, and accurate skill execution is the fundamental goal of SLA and FLA.

A growing number of studies have inquired into processing speed in L2 performance by examining response times in language tasks. In L2 research, response-time measures have been used mostly to examine lower order processes, such as lexical decisions (Jiang, 2002), grammaticality judgments (White & Juffs, 1998), and sentence decoding (Juffs, 1998). Results generally confirm that processing speed is related to automatization of lower order processes, and that the automaticity is related to proficiency (Carber, 1990;

Segalowitz, 2001; Towell, 2002). However, little research has examined speed of higher order processing, such as comprehension of implied intentions. Thus, it is important to find out whether previous findings about the relationship between proficiency and processing speed can be extended to higher level language use, such as pragmatic processing, which involves processing of multiple pragmatic cues, including contextual information, schemata, and knowledge of communication conventions. Only a few studies to date have examined speed in pragmatic comprehension (Takahashi & Roitblat, 1994; Taguchi, 2005). Takahashi and Roitblat examined L2 processing patterns of conventional indirect requests – whether L2 learners activate literal interpretation of indirect requests first or they immediately process illocutionary force of requests. ESL learners and native speakers of American English read 12 stories: six including implied requests and six including literal interpretations of the utterances. Results showed that, although ESL learners took longer to comprehend the indirect requests than native English speakers, they showed processing patterns similar to those of native speakers. The learners read at the same speed whether the target sentence was interpreted as a conventional request or was interpreted literally. In Taguchi’s (2005) study, native English speakers and Japanese college students of EFL completed a listening test measuring ability to comprehend more and less conventional implicatures. More conventional implicatures had indirect requests and refusals that had conventional features (e.g., making a request by using Do you mind if followed by a subject). In less conventional implicatures, meaning was not attached to specific linguistic forms (e.g., indicating a negative opinion of a movie by saying I was glad when it was over). Comprehension was analyzed for accuracy and speed. Results showed that, for L2 learners, comprehension of more conventional implicatures took less time than comprehension of less conventional implicatures. Proficiency had a significant impact on accuracy, but not on comprehension speed, and no significant relationship was found between accuracy and comprehension speed. These previous studies suggest that processing speed could be a reflection of

learners’ ability to comprehend implied meaning. Taguchi’s study in particular suggests that speed has distinct characteristics on its own, independent from general L2 proficiency or accurate demonstration of pragmatic knowledge. It seems that pragmatic knowledge and the capacity to use or process the knowledge are distinguishable underlying aspects of L2 communicative competence and thus should be examined separately. What is not yet examined to date is longitudinal development of processing speed when comprehending pragmatic meaning. In L2 research, a limited number of studies have investigated development of performance speed over time using a pretest and posttest design, mostly in the areas of oral fluency (Freed, 2000; Segalowitz & Freed, 2004; Towell, 2002) and word recognition (Segalowitz & Segalowitz, 1993; Watson, & Segalowitz, 1995 in Fukkink, Hulstijn, & Simis, 2005). Segalowitz and Freed administered an oral proficiency test at the beginning and the end of a semester to college students of Spanish in a domestic environment and in a study-abroad environment. The results showed that the study-abroad students made significant gains in oral fluency. Theories of cognitive skill development claim that increased performance speed is related to increased L2 practice (Anderson, 1990). According to Anderson, skill development involves a shift from declarative knowledge (knowledge that) to procedural knowledge (knowledge how). For instance, knowing a rule that English plural nouns are marked with a suffix s is declarative knowledge, but using the rule in real time reflects procedural knowledge (Anderson, 1990: 92).

Language acquisition is a process where declarative knowledge becomes procedural. At the initial stage of skill development, L2 learners retrieve and use language rules consciously. After repeated practice in applying rules, the use of rules becomes increasingly automatic, rapid, and unconscious. Automaticity develops through consistent associative practices between input and learners’ response, as shown in some L2 studies. Snellings, van Gelderen, and Glopper (2003:102) examined the effect of training on fluent lexical retrieval among Dutch learners of L2 English. Learners who received semantic access training

had higher accuracy scores and faster reaction times in recognizing word meaning. Based on the theoretical claims and empirical findings, it is reasonable to assume that increased L2 experience over time will promote rapid skill execution. However, in EFL pragmatics, little research has examined the development of speed over time. Performance speed in pragmatics might show a different developmental course because of a number of resources to be processed, including linguistic, contextual, and sociocultural resources. Another gap in the literature is the analysis of factors that may affect speed of pragmatic processing. Taguchi (2005) found that general L2 proficiency did not influence speed of pragmatic comprehension among EFL students. A question then remains as to what factors actually affect processing speed in pragmatic comprehension. Some candidate factors belong to the domain of cognition, including semantic access ability, pattern recognition, short-term memory, and attention control. These factors reflect overall cognitive abilities, a set of components that enable us to allocate and select and coordinate information in language tasks (Bialystok, 1990 in Robinson, 2003, 2005; Widdowson, 1989). Among those cognitive factors, lexical access speed, one processing characteristic, has been recognized as a factor that is directly implicated in performance fluency. Processing speed of lexical items (e.g., words) is considered as one of the underlying abilities in speedy skill execution (Ackerman, 1988). An increasing number of L2 studies have examined lexical access ability as an underlying component skill in language performance (DeKeyser, 2001).

Segalowitz and Freed (2004) examined whether lexical access speed and attention control are related to oral fluency gains among L2 Spanish learners. Results revealed that oral fluency significantly correlated with lexical access speed but not with attention control ability.

Their study confirmed that the ability to access meanings quickly could promote fluent speech. Building on recent work, L2 pragmatics research that incorporates measures of cognitive processing abilities, such as lexical access speed, in addition to L2 proficiency, could reveal factors that affect

speed as well as accuracy of pragmatic comprehension. Pragmatic comprehension involves processing at multiple levels. It involves lower level processing of attending to and assigning meaning to aural stimuli (Wolvin & Coakley, 1985: 99).

It also involves higher level processing – supplementing acoustic information with nonacoustic information (e.g., prior knowledge, schemata) to derive meaning behind utterances (Smith, 1975: 304). One can assume that lexical access speed, namely the ability to access word meaning quickly, reflects lower level processing which underlies the process of comprehending pragmatic meaning. However, because this assumption has not been tested, it merits empirical investigation. Briefly, very few studies have addressed the development of pragmatic comprehension ability.

As Kasper (2001) states, pragmatic competence refers to the acquisition of pragmatic knowledge and to gaining automatic control in processing it in real time. Thus, the two dimensions (i.e., pragmatic knowledge and processing capacity for the knowledge) should be addressed together because they provide complementary insight into developmental accounts of pragmatic comprehension. In addition, with increasing attention to the interdependence between cognition and language performance, cognitive processing abilities, such as lexical access skill, are considered to affect performance. Because limited empirical evidence has demonstrated the relationship among cognitive variables, general foreign language proficiency, and pragmatic comprehension, future research also awaits in this direction.

2.2. Comprehension Versus Production

Language allows people to express and communicate their thoughts to others. Using language to communicate these thoughts relies on their abilities to both produce and to comprehend language. That is, without someone who can comprehend language (the ‘listener’), someone producing an utterance (the ‘speaker’) will not be able to communicate thoughts via that utterance. Luckily,

each one of us is both a speaker and a listener (Taguchi, 2002). Both the dependency between production and comprehension for communication and the fact that people all have both abilities, leads to a central question in language research: how are the two processes related? In other words, is going from thought to language and from language to thought, accomplished by a single system working in two directions, or by two separate systems? Most of the research on this question comes from the domain of psycholinguistics, primarily because of the focus on intermediate mental representations and processes (Grice, 1975).

Traditionally, psycholinguistic research has treated production and comprehension as independent systems, each with its own set of representations and processes. Perhaps the most influential findings that contributed to this traditional view were the discoveries of two functionally and anatomically distinct aphasias (Lichtheim, 1985). Patients with damage to Broca’s area are described as having impaired language production abilities, but relatively intact comprehension. Their speech is characterized as being broken and telegraphic, lacking function words and containing many articulatory disfluencies. In contrast, patients with damage to Wernicke’s area are characterized as having impaired language comprehension. Their speech is fast, fluent, and grammatical, but lacking in true content or meaning (Lichtheim, 1985). Additionally, Wernicke’s aphasics have severe difficulties in their comprehension abilities. Further evidence supporting the dissociation between production and comprehension comes from studies of language development. Generally, comprehension abilities develop prior to production abilities. Children typically understand words before they begin to produce those same words (Benedict, 1979).

Production and comprehension also differ with respect to the local processing problems that must be solved. Taguchi (2002: 281) briefly explains this as follows:

This is most easily demonstrated by considering that production begins with a thought or message to be conveyed. The non-linguistic representation

corresponding to this message must then be mapped onto corresponding linguistic representations (e.g., words). These linguistic representations must then be correctly ordered (e.g., phrases and clauses), and be translated into articulatory commands. Along the way, the speaker is in control of the input (the speaker knows the message to be conveyed) and outputs (what actually gets said). That is, speakers determine the content of the utterance, the speed of the utterance, and what the intended effects of the utterance are to be. The situation for the listener is quite different. The listener is not in control of the input to the comprehension system. The listener’s task is to interpret the utterance and to attempt to recover the speaker’s intended message. The problem for the listener is that ambiguities may arise at nearly every step of the process, during interpretation of the acoustic input, retrieval of the appropriate words and their meanings, the construction of the appropriate syntactic representation, and finally, the construction of an overall integrated interpretation.

So, while on the surface, comprehension and production may appear to be the same sets of processes acting in opposite directions, the two systems must resolve different problems along the way, which may involve very different processing mechanisms and representations.

2.3. Pragmatic Considerations in Language Learning

The discipline of pragmatics, its subdiscipline, interlanguage pragmatics and the concept of pragmatic competence possess a relatively short history when compared to other disciplines. Nonetheless, these three terms can be found in abundance in the recently conducted studies ranging from the field of philosophy, second language acquisition, literature, neurology to cognitive sciences. This groundbreaking ascend parallels the general paradigm shift in linguistics, hitherto focusing on syntax and structuralism. In the mid-1900s, as an opposition to the structuralist line, scholars like James (1907) in Morris (1938), Austin (1962) busied themselves with the use and users of language. As the gift of their studies, the offshoots of pragmatics grew into a broader discipline, defined by Crystal (2001: 269) as: the study of language from the

point of view of the users, especially of the choices they make, the constraints they encounter in using language in social interaction, and the effects their use of language has on the other participants in an act of communication. This route of isolation from the structuralist and formalist approaches continued with the works of functional theorist like Halliday (1973).

Under the influence of these, Hymes (1972) contributed to another shift of paradigm in second language acquisition. As an opposition to Chomsky’s (1965) highly abstract concept of competence, Hymes proposed the notion of communicative competence (CC). In Chomsky’s scheme, competence merely comprises of nonobservable knowledge of the rules of a language, whereas performance is the observable realization of knowledge of language. Hymes’ concept, “communicative competence” includes not only knowledge of linguistic rules but also rules and use of communication, which is similar to Chomsky’s component of performance.

With Canale and Swain (1980) and Canale’s (1983: 5) expansion on Hymes’ formulation, more dimensions—grammatical competence (knowledge of lexical items, morphology, syntax, semantics, phonology), sociolinguistic competence (knowledge of rules governing the production and interpretation of language in different sociolinguistic contexts), discourse competence (cohesion and coherence) and strategic competence (appropriate use of communication strategies) were annexed to the CC concept. Thus, the distinction between linguistic and nonlinguistic dimensions of CC was determined. Following Canale and Swain, Bachman (1990) set out to develop her version of CC, namely, “communicative language ability”. This model was different from the earlier models in that it allocated pragmatic competence an independent and significant position as one of the two basic parts of communicative ability. This emphasis on pragmatic competence signalled the growing concern for developing pragmatic skills.

In another model by Celce-Murcia et al (1995), discourse competence dimension of CC was centralised and linguistic, sociocultural, and actional

competence were presented as interrelated to this central dimension. Lastly, the strategic competence was regarded to be influencing all of the other components. In this model, pragmatic competence, though represented under another name, actional competence, was continued to be recognized as one of the basics of CC. In accordance with the previous models, one of the latest models of communicative competence, devised by Council of Europe, puts more emphasis on the communicative language competences than the general competences such as knowledge or learning ability. All four skills, linguistic and sociolinguistic competences are included within the domain of communicative competences – a person’s ability to act in a foreign language in linguistically, sociolinguistically and pragmatically appropriate ways (Council of Europe, 2001: 9). Pragmatic competences are recognised as another component of the communicative competence and defined as “the functional use of linguistic resources (production of language functions and speech acts), mastery of discourse, cohesion, coherence, irony, and parody” (Council of Europe, 2001: 13).

The shift of attention from linguistic competence to communicative competence and the latter shift to the dimensions of it, such as pragmatic competence, seem to be competing with the rise of another competence – intercultural competence recently. This term refers to “the complex of abilities needed to perform effectively and appropriately when interacting with others who are culturally and linguistically different from oneself” (Fantini, 2005: 1). As a matter of fact, the two types of competence are connected to each other in that they both value the sociocultural aspects of language learning. The term intercultural communicative competence (ICC) incorporates both competences into a more comprehensive notion. Now foreign language learners are expected to develop not only effective communicative skills, but also an awareness of the target language culture. The development of ICC has also been supported by Council of Europe (2001) on the grounds that cultural diversity and plurilingualism should be encouraged among Europeans from different countries.

These rapid improvements in the conceptualisations of pragmatic and intercultural competence have brought about the birth of a subdisciplinary field – Interlanguage Pragmatics (ILP), the primary concern of which is the investigation of non-native speakers’ comprehension and production of speech acts, their universality, and the acquisition of L2 related speech act knowledge (Kasper and Dahl, 1991: 215). In the recently conducted studies, the development of pragmatic competence, the effects of such factors as input, proficiency, individual differences, pragmatic transfer, the role of context and linguistic form, which contribute to pragmatic comprehension, are also researched. Depending on the findings of crosscultural pragmatics and other disciplines such as neurology, pscycholinguistic part of the studies have been devoted to the study of comprehension of non-literal and implicit meanings, particularly implicatures (Gibbs, 2002; Holtgraves, 2004). Bialystok (2003: 54) points out that adult L2 learners make pragmatic errors not only because they do not understand forms and structures, or they do not have sufficient vocabulary to express their intentions, but because they make wrong interpretations of utterances. This may lead to miscommunication. With a view to learning if language learners have such difficulties, in the present study not only the comprehension but also the production of implicatures by EFL learners will be investigated.

2.4. Implied Meaning and Foreign Language Learning

In order for L2 learners to communicate in the FL they should not expect everything to be clear and direct in conversation as this is not possible in any language. This indirectness makes it more difficult for the L2 learner to comprehend the native speakers, whose conventions are less familiar (Bialystok, 2003: 53). Corbett (2003) explains the dilemma as follows:

A considerable difficulty for non-native speakers tackling casual conversation in English is that much of what is said is indirect. People do not mean what they literally say. Participants in conversations, then, have to infer what is meant from what is actually said. The name usually given to an expression that demands some kind of inference to make sense is

conversational implicature. Both transactional and interactional talk make frequent use of implicatures.

(p. 58)

As explained above, the process whereby speakers of a language communicate without expressing their intentions directly is termed conversational implicature or implicature in short. Before going into a lengthy explanation of implicatures, it is more useful to develop an insight into types of meaning. In the literature, the distinction between what is said and what is meant is clearly drawn. The former, literal-conventional meaning depends on the linguistic (semantic) value of the proposition – usually named as the truth value, whereas the latter, nonconventional meaning is related to further propositions intended for speaker meaning and pragmatic factors (Grice, 1978: 162).

Horn (2004: 3) asserts that “what a speaker means” is far richer than “what s/he directly says or expresses”. Thomas (1995: 57) adds that there is an additional level of meaning beyond the semantic meaning of the utterances. In this sense, implicature is “a component of speaker meaning that constitutes an aspect of what is meant in a speaker’s utterance without being part of what is said” (Horn, 2004: 3). In the light of these, the communicative content of an utterance consists of what is said and what is implied.

Differences between semantic and pragmatic meaning Semantic meaning Pragmatic meaning Literal, Conventional, Concrete Non-literal, Non-conventional, Contextual

Sentence meaning Utterance meaning What is said What is implied Explicitly expressed Implicitly expressed Related to linguistic content Related to contextual content

Truth-conditional Non-truth conditional Context independent Context dependent ( Horn,2004: 4)

Now that semantic and pragmatic meanings are two distinct things, they may involve different interpretations. Explaining that pragmatic interpretation is not specifically linguistic as in the case of semantic interpretation, Recanati (2004: 451) adds that pragmatic interpretation is involved in the understanding of human action in general. Thus, he points out that a broader mechanism – something deeper than the mechanical interpretation of semantics is at work in pragmatic processes. Although the processing of this mechanism is not accounted for yet, some studies have shown that it works differently in children and adults. Children are shown to be attending to literal meanings more often, whereas adults use their rich schematic and contextual knowledge to interpret meanings. As Blakemore (1992: 10) confirms, “utterance interpretation takes place so fast and so spontaneously that we are not usually aware of how we recover the message we do”. Leaving aside the biological foundations of pragmatic interpretation, as Grice did earlier, in the present study, pragmatic interpretation, and its subcomponent, implicature processing, will be considered as default skills.

2.5. Grice’s Theory of Co-Operative Principle

As a philosopher following the convention of Austin (1962), who had introduced the notion of speech acts – actions performed via utterances (Yule, 1996: 47), Grice continued the informal approach to language use and conversation. Austin (1962) had made the distinction between what is said and meant earlier and going one step further, Grice explored how the hearer gets from what is said to what is meant (Thomas, 1995: 56). Beyond this exploration stands his general theory of communication – the Co-operative Principle (CP).

Grice formulated the CP with a view to accounting for the conduct of everyday conversation. Asserting that human communication could not be explained by formal logic operators (Green, 1989: 88; Levinson, 1983: 113; Vershueren, 1995: 190) due to its tendency for indirectness, Grice emphasized the need for cooperation in discourse.

The CP is grounded on one basic principle and four maxims:

Make your contribution such as is required, at the stage at which it occurs, by the accepted purpose or direction of the talk exchange in which you are engaged (Grice, 1975: 307).

1. The maxim of Quality: Try to make your contribution one that is true, specifically:

(i) Do not say what you believe to be false

(ii) Do not say that for which you lack adequate evidence 2. The maxim of Quantity

(i) Make your contribution as informative as is required for the current purposes of the exchange

(ii) Do not make your contribution more informative than is required. 3. The maxim of Relevance

Make your contributions relevant

4. The maxim of Manner: Be perspicuous, and specifically: (i) Avoid obscurity

(ii) Avoid ambiguity (iii) Be brief (iv) Be orderly

These maxims can be recognized as tacit assumptions of communicative behaviour although they should not be taken as rules or advice for speech as Levinson (1983: 102) warns: It can be readily admitted that few people follow these guidelines to the letter. Rather, in most ordinary cases these principles are oriented to, such that when talk does not proceed according to their specification, hearers assume that, contrary to appearances, the principles are nevertheless being adhered to at some deeper level.

This is the reason why Grice incorporated implicatures to his system; he strived to explain non-conformance to the CP (Lakoff, 1995: 191). Even when speakers do not abide by the maxims, hearers can sense that s/he is still being cooperative. The hearer will change his reasoning in this situation and interpret the speaker’s utterance accordingly. Through paralinguistic, linguistic, or non-linguistic hints, the speaker indirectly conveys the intended meaning to the hearer, and expects

the hearer to deduce the message with the same hints (Thomas, 1995: 58). This does not mean that the hearer is always successful, though. What is implied by the speaker may not correspond to what is inferred by the hearer.

The contributions Grice provided to the field of pragmatics are enormous in two aspects. First of all, Grice led the way to the formation of a subdomain of linguistics by making the distinction between semantics and pragmatics (Prince, 82: 1). Second, he attempted to describe a conversational phenomenon, which is a hard task to manage with the tools of formal logic. The informal approach he adopted proved to be highly influential since to date it is the most widely acknowledged one; yet, such an informal theory has inevitably some deficiencies. The most evident shortcoming of the Gricean theory is the claim that it is in fact not a complete theory but a basis for one (Prince, 1982: 2; Thomas, 1995: 56, Levinson, 1983: 118). Searle (1969) tried to fill in the gaps of the theory. He argued that the theory was hearer oriented and that it should follow a speaker centred approach (Aysever, 2003: 41). The explanation given for the calculation of implicatures was also shown to be insufficient and ad hoc (Cruse, 2000: 369, Thomas, 1995: 87). Furthermore, the distinction between different types of nonobservance is not clear (Thomas, 1995: 87). Again there is an opposition to the universality claim. However, as Lakoff (1995: 195) points out, the CP applies in other cultures, but with different basic assumptions. Although CP has its deficiencies, the theoretical basis it provides is satisfactory for the purposes of the present study. As Cook (cited in Gobel, 2005) puts forth, analysis of spoken interactions with the Gricean framework can be rewarding: Pragmatic theories including the Cooperative Principle provide essential insights both into the problems of communicating in a foreign language and culture. They are essential tools for discourse analysis and thus for the teacher and learner. Thus, in this study Grice’s framework for implicatures is adopted in the pragmatic analysis of EFL learners’ comprehension skills.

2.6. Non-Observance of Conversational Maxims

Grice in his studies tries to raise awareness that users of a language often transgress the expectation that they would follow the maxims mentioned above and did so for interactional reasons. Non-observance of these conversational maxims can take some number of forms. These include:

1. The most direct form of non-observance of the CP is violating one or more maxims. The violator-speaker aims to mislead or deceive the hearer quietly and unostentiously (Grice, 1975: 310; Thomas, 1995: 72). Due to the absence of a communicative effort to send an indirect message to the hearer, this misbehaviour does not lead to implicatures (Peccei, 1999: 27). Telling a lie is an obvious example of a violation of the maxim of quality (Green, 1989: 89, Cutting, 2002: 92).

2. As opposed to violating the maxims covertly, a speaker may express his/her willingness to comply with the norms of the CP, which is called opting out of a maxim. In order to indicate this to the hearer, the speaker simply states his/her conditions with either implicit or explicit messages such as “I cannot say any more. My lips are sealed.”, “I’m not sure if it’s true, but…”, “I have no evidence for this, but…” (Thomas, 1995: 74, Green, 1989: 30, Harnish, 1991: 330).

3. Unintentional failure to observe the CP results in infringement of maxims. The causes of their generation may vary; it might be due to the imperfectness of child speech or foreigner talk; temporary situations like nervousness or drunkenness, a cognitive disorder or the speaker’s incapability (Thomas, 1995: 74). There is controversy concerning the boundaries of infringement. Harnish (1991: 330) explains infringement as the general term for any non-observance of the CP, and relates it to the clash between maxims. Thomas (1995: 72) points out to this irregularity as follows: “It is extremely irritating to note that Grice himself does not use these terms consistently and remarkably few commentators seem to make any attempt to use the terms correctly.”

4. There are also occasions in which the speaker does not have to opt out of observing the maxims (Thomas, 1995: 76) but just suspend the maxims. Keenan