Original article /

Araştırma

A cross-sectional study comparing some clinical features of

patients with rapid cycling and non-rapid cycling bipolar disorder

Murat Eren ÖZEN,

1Mehmet Bertan YILMAZ

2_____________________________________________________________________________________________________

ABSTRACT

Objective: Literature indicates that rapid cycling (RC) feature in bipolar disorder (BD) has been associated with

worse disorder outcome and more severe disability. We aimed to investigate factors that affect or involved in vulnerability to increase rapid cycling in the previous 12 months. Methods: This is a cross-sectional study. Patients (n=380) were recruited from an outpatients clinic of a general hospital. Diagnostic interviews were performed with Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV Disorders (SCID-I) and SCID-II. Sociodemographic Form, Young Mania Rating Scale (YMRS) and Hamilton Depression Rating Scale (HAM-D) were applied. RC was defined as presence four or more mood episodes in the previous 12 months. Patients were arranged as whether having rapid cycling bipolar disorder (RCBD) or not. RCBD was compared to the group of non-RCBD patients regarding the sociode-mographic and clinical data. Results: Study group showed a female preponderance (65.0%). Sixty patients (15.8%) had RC in the previous 12 months. There were statistically significant differences between two groups regarding in number of suicide attempts, family history of mood disorders, psychotic depression, number of antidepressants utilized, manic, depressive, mixed and total number of episodes. Discussion: The presence of RC in the previous 12 months was found correlated with specific clinical features closely related to worse outcome in the course of BD. Further studies are needed to clarify disease-related factors in patient groups with a standard definition of homo-geneous RCBD. (Anatolian Journal of Psychiatry 2019; 20(5):477-484)

Keywords: bipolar disorder, rapid cycling, clinical variables

Hızlı döngülü ve hızlı olmayan bipolar bozukluk hastalarının

bazı klinik özelliklerini karşılaştıran kesitsel bir çalışma

ÖZ

Amaç: Literatür, bipolar bozuklukta (BB) hızlı döngü özelliğinin (HD) daha kötü hastalık sonucu ve daha ciddi

malu-liyet ile ilişkili olduğunu göstermektedir. Son 12 ayda HD'yi etkileyen veya artmasında etkili etkenleri araştırmayı amaçladık. Yöntem: Bu bir kesitsel çalışmadır. Hastalar (s=380) genel bir hastanenin polikliniklerinden alındı. Tanı görüşmelerinde DSM-IV Bozuklukları için Yapılandırılmış Klinik Görüşme (SCID-I) ve SCID-II uygulandı. Sosyode-mografik Form, Young Mani Derecelendirme Ölçeği (YMRS) ve Hamilton Depresyon Ölçeği (HDÖ) uygulandı. HD, önceki 12 ayda dört veya daha fazla duygudurum nöbetinin varlığı olarak tanımlandı. Hastalar hızlı döngülü bipolar bozukluk (HDBB) tanısı olup olmadıklarına göre ayrıldı. HDBB hasta grubu, HDBB olmayan hasta grubuyla sosyo-demografik ve klinik veriler açısından karşılaştırıldı. Sonuçlar: Çalışma grubunda kadınlar daha yüksek orandaydı (%65.0). Altmış hastada (%15.8) son 12 ayda HD vardı. İntihar girişimi sayısı, duygudurum bozuklukları aile öyküsü, psikotik depresyon, kullanılan antidepresan sayısı, manik, depresif, karışık ve toplam nöbet sayısı açısından iki grup grup arasında istatistiksel olarak anlamlı farklılıklar bulundu. Tartışma: Son 12 ayda HD varlığı, BB gidişinde daha

kötü sonuçlarla yakından ilişkili özgül klinik özellikler ile ilişkili bulundu. Standart tanımı yapılmış ve homojen HDBB

_____________________________________________________________________________________________________

1 Private Adana Hospital, Adana 2 Çukurova University, Adana

Correspondence address / Yazışma adresi:

Uzm. Dr. Murat Eren ÖZEN, Private Adana Hospital, Adana, Türkiye E-mail: muraterenozen@gmail.com

Received: December, 12th 2018, Accepted: February, 04th 2019, doi: 10.5455/apd.22515

hasta gruplarında hastalıkla ilişkili etkenlerin açığa çıkartılması için daha fazla çalışmaya gerek vardır. (Anadolu

Psikiyatri Derg 2019; 20(5):477-484)

Anahtar sözcükler: Bipolar bozukluk, hızlı döngü, klinik değişkenler

_____________________________________________________________________________________________________ INTRODUCTION

Bipolar disorder (BD) is a chronic disease that is defined by cyclic episodes of severe mood oscil-lations followed by periods of remission. The severity of episodes alters, and polarity might represent as depression or mania. A bipolar cycle is characterized as the period between the onset of an episode of any polarity and the occur-rence of a new mood episode of any polarity. The cycling model is a clue characteristic for this disorder, and the period and frequency of cycles changes from days to years.1 It emerges that

rapid cycling identifies a special subgroup of patients with bipolar disorder.2 For now, rapid

cycling definition is currently a process specifier for BD in DSM-5.3 The requirement of a history

of four or more affective episodes during any period of 12 months in the past is defined as RC.4

Since the first description in 1974,5 rapid-cycling

(RC) BD has been represented to be existing in about 12-24% of patients with bipolar disorders at specialized mood disorder clinics.6,7 The

approximatively 12-month prevalence of RCBD ranges from 9 to 32%, whereas the lifetime prevalence of RCBD ranges from 26 to 43%.4,8,9

For episodes of the same polarity, a remission period of at least two months must emerge to define RC bipolar disorder (RCBD). On the other hand, for episodes of opposite polarity, a remis-sion period is not required.6

Many studies have investigated the differences between BD patients with and without RC. In general, RCBD has been associated with worse disorder outcome,10,11 and more severe

disabi-lity.9 More specifically, many factors have been

described to be correlated with RC, such as earli-er age at onset,12 female gender,11,13 elevated

risk for suicide,11,14 predominance of

depres-sion,15 bipolar type II disorder,16,17 and higher

percentages of antidepressant utilization.10

In a recent study, it was suggested that RCBD is a group of patients with more specific, more symptomatic BD patients, and supports the existence of a relationship between more suicide attempts, more antidepressant use with RC, and an earlier BD.18 There are studies showing that

antidepressants are not a factor in improving depressive symptoms in the RC 19 and that mood

shifts can be prevented even though

antidepres-sant treatment does not affect recovery.20

It is understood that the differences in the studies are due to the fact that the definition of RC is not uniform. In addition, there are criticisms of the use of heterogeneous samples in the studies. For these reasons, it is concluded that more studies are needed to clarify the existence, emergence and whether there is a separate determinant of BD. For this purpose, in the cur-rent study, we aimed to investigate factors in a group of patients with BD (BD I, BD II) that affect or involved in vulnerability to increase RC in the previous 12 months.

METHODS

This is a cross-sectional study of patients with BD type I and BD type II. Patients were selected from the Outpatients Clinic of Private Adana Hospital that applied between June and Decem-ber 2018. The study was approved by the Ethics Committee of Çukurova University. All patients gave written informed consent to participate in the study.

All patients were diagnosed using the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV Disorders (SCID-I)18 and SCID-II19 was applied to assess

personality disorder. Patients aged 18-65 years, diagnosed with BD type I or BD type II, followed for at least 6 months in the outpatients unit and who were in remission (euthymic state) for at least 3 months were included in the study. Patients with active bipolar disease, active psychosis, dementia, mental retardation, Parkin-son's disease, degenerative diseases, neurolo-gical diseases such as multiple sclerosis, SLE, chronic renal failure and those with systemic chronic disease were excluded from the evalua-tion. The exclusion criteria were defined as having any neurological or physical disease and cognitive deficits which may cause problems in understanding the research guidelines and filling in the scales.

Remission state is defined as not having any mood episode in the last 3 months. This situation was evaluated with the scales used in the study. HAM-D, YMRS scales were applied to provide remission properties of patients diagnosed with BD by SCID-I.18

Instruments

Sociodemographic Form: By this form

pa-tients’ age, age at onset of BD; number of epi-sodes (manic, depressive, mixed and hypo-manic); polarity of the first episode; gender; number of hospitalizations; family history of mood disorder; the number of suicide attempts; early childhood abuse, family history of schizo-phrenia, history of ADHD, alcohol-substance abuse, axis II comorbidity, seasonal pattern, anxiety (any), psychotic depression, psychotic symptoms at first episode, psychotic symptoms during illness, number of antidepressants; and current use of medications (antipsychotics, anti-convulsants, lithium, and antidepressants) were assessed.

Young Mania Rating Scale (YMRS): YMRS

was developed to measure the severity and change of manic condition.23 This scale

as-sesses the patient’s insight, appearance, ele-vated mood, language-thought disorder, in-creased motor activity-energy, sleep, sexual interest, disruptive-aggressive behavior, content, irritability, and speech-rate and amount. The YMRS total score, with a range of 0 to 60, was a summation of each of the eleven individual scores, with the higher total YMRS scores re-flecting greater symptom severity. This form is validated by Karadağ et al.24

Hamilton Depression Rating Scale (HAM-D):

It is developed by Hamilton and measures the level of depression and change in severity of the patient, facilitates follow-up during treatment and does not make a diagnosis.25 It consists of 17

items that question the symptoms of depression in the last week, with a maximum of 53 points. The items related to the difficulty of falling asleep, waking up in the middle of the night, early morning waking, somatic symptoms, genital symptoms, attenuation and insight were rated at 0-2, and the other items were rated between 0-4. In our study, ≥8 points was accepted as having depression. The validity and reliability of the Turkish form was performed by Akdemir et al.26

Procedure

All the participants were informed about the study and their written approvals were obtained. Patients who did not have any obstacle to the application of the interview or the scale, and who agreed to participate in the study were included in the study. Patients who were followed up with bipolar disorder in euthymic state in the out-patients psychiatric unit were enrolled in the study and the sociodemographic form was

com-pleted for each patient. After the diagnostic inter-views with SCID-I and SCID-II, for the severity of manic symptoms YMRS and for the severity of depressive symptoms, HAMD scales were ap-plied during follow-up. RC was described as four or more mood episodes in the previous 12 months. Patients were arranged as whether having RCBD or not. After defining that, the group established with RCBD was compared to the group of non-RCBD patients regarding the sociodemographic and clinical data.

Statistical analysis

Categorical variables were analyzed using the Pearson chi-square test and the Fisher exact test. For continuous variables, differences be-tween groups were tested using the Mann-Whit-ney test. Significance was set at p<0.05. Statis-tical analysis was done using SPSS (v. 22.0). RESULTS

Our sample included 380 patients. Female pre-ponderance was present in the total sample (65.0% vs. 34.5%). BD type I and type II were identified in 87.1% (n=331) and 7.4% (n=28) respectively. Of the patients, 60 (15.8%) had RC in the previous year.

There were not any statistical differences be-tween RCBD and non-RCBD groups regarding mean age and genders. There were statistically significant differences in number of suicide at-tempts (2.03±0.28 vs. 1.64±0.12, p=0.011), family history of mood disorders (53.33% vs. 53.44%, p=0.047), number of antidepressants utilized (2.43±0.13 vs. 2.44±0.06, p=0.032) and psychotic depression (28.33% vs. 28.44%, p=0.021). Characteristics of BD patients are de-picted in Table 1.

This difference was significant for both manic (RCBD=9.53±0.80 vs. non-RCBD=7.30±0.35, p=0.007), depressive (RC=13.50±1.19 vs. RCBD=7.98±0.49, p<0.000), mixed (RCBD= 1.05±0.07 vs. non-RCBD=0.82±0.05, p=0.004) and total number (RCBD=18.50±1.60 vs. non-RCBD=14.23±0.68, p=0.041) episodes. How-ever, there was no statistically significant differ-ences between RCBD and non-RCBD regarding the number of hypomanic episodes (p=0.218) (Table 2).

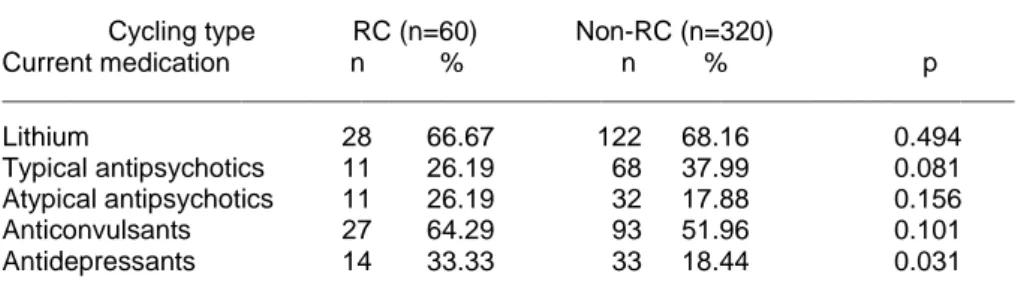

Regarding current psychotropic treatment use, we observed a significant difference for anti-depressants (RCBD=33.33%, non-RCBD=-18.44%, p=0.031), but not for lithium, typical anti-psychotics, atypical antipsychotics and

vulsants (Table 3). DISCUSSION

In the present study, we evaluated some clinical features of RC and RCBD in sample of 380 BD type I and type II patients.

Table 1. Characteristics of dipolar disorder patients

___________________________________________________________________________________ Cycling type RC (n=60) Non-RC (n=320) Characteristics Mean±SD Mean±SD p ___________________________________________________________________________________ Age (years) 32.83±2.51 33.22±1.09 0.781 Age at onset (years) 26.33±2.04 26.50±0.88 0.881 Number of antidepressants 2.43±0.13 2.44±0.06 0.032 Number of suicide attempts 2.03±0.28 1.64±0.12 0.011 Number of hospitalizations 2.58±0.30 2.52±0.13 0.714 Disease duration (years) 6.50±1.08 6.72±0.47 0.716 n % n %

Female gender 39 65.00 210 65.63 0.235 Family history of mood disorders 32 53.33 171 53.44 0.047 Seasonal pattern 11 18.33 55 17.19 0.087 Family history of schizophrenia 13 21.67 74 23.13 0.081 Psychotic depression 17 28.33 91 28.44 0.021 Psychotic symptoms at first episode 23 38.33 118 36.88 0.128 Psychotic symptoms during illness 34 56.67 179 55.94 0.210 Hospitalization (yes) 35 58.33 218 68.13 0.083 Early childhood abuse 22 36.67 116 36.25 0.293 Alcohol-substance abuse 10 16.67 44 13.75 0.127 Axis II comorbidity 20 33.33 110 34.38 0.093 Anxiety (any) 49 81.67 259 80.94 0.230 ____________________________________________________________________________________

RC: Rapid cycling; Chi-square test/Fisher’s exact test or Mann-Whitney U test.

Table 2. Comparison of rapid and non-rapid cycling bipolar disorder patients

in terms of mood episodes

____________________________________________________________________ Cycling type RC (n=60) Non-RC (n=320)

Episode characteristics Mean±SD Mean±SD p ____________________________________________________________________ Number of episodes 18.50±1.60 14.23±0.68 0.041 Manic 9.53±0.80 7.30±0.35 0.007 Depressive 13.50±1.19 7.98±0.49 <0.001 Hypomanic 1.17±0.09 0.85±0.05 0.218 Mixed 1.05±0.07 0.82±0.05 0.004 ____________________________________________________________________

RC: Rapid cycling; Chi-square test/Fisher’s exact test or Mann-Whitney U test.

Table 3. Current psychiatric treatment of rapid and non-rapid bipolar disorder patients ____________________________________________________________________________

Cycling type RC (n=60) Non-RC (n=320)

Current medication n % n % p ____________________________________________________________________________ Lithium 28 66.67 122 68.16 0.494 Typical antipsychotics 11 26.19 68 37.99 0.081 Atypical antipsychotics 11 26.19 32 17.88 0.156 Anticonvulsants 27 64.29 93 51.96 0.101 Antidepressants 14 33.33 33 18.44 0.031 ____________________________________________________________________________

RC: Rapid cycling; Chi-square test/Fisher’s exact test

Consistent with prior studies,11,13 women were

more likely to be rapid cyclers (65%) than men (35%). Women may be considered to be more susceptible to RCBD for the reasons attributed to biological activities. It is suggested that this condition is also associated with the onset age of the disorder for women.13

It has been argued that earlier age at onset may be related to a kindling mechanism that will final-ly cause to autonomous mood episodes that do not need a trigger.27

The higher number of suicide attempts in RC group of patients may indicate the worse course of a patient with this type of disorder.11,14

Gigante et al. reported the number of lifetime hospitalizations similar in both groups, but a con-siderably higher percentage of non-RC patients had been hospitalized when compared with RC patients.18

Bipolar patients had a threefold increase in BD in their biological relatives. Bipolar patients with a family history of affective disorders usually have an earlier age at onset,Hays12 more psychotic

symptoms,28 possibly more episodes,29 and

higher levels of comorbidity.30 Especially current

co-morbidity was associated with an earlier age at onset and worsening course of disorder.10

The higher number of antidepressant use in RC patients is shown by different studies.9,11,17,31

Some researches support negative impact of antidepressants.9,17 In addition, the number of

antidepressant use was identified significantly higher in RC patients and, not surprisingly, was correlated with anxiety and depression as onset episode. It is likely that this reflects anxiety and depression as remarkable later episodic forms of morbidity following such onsets.13

Some authors stated that the likelihood of cycling enhances linearly with antidepressant use, with patients taking antidepressants being over three fold more likely to have RC than patients who do not utilize antidepressants.9,17

Psychiatric disorder typically considered to be comorbid with BD was especially strongly corre-lated with first episodes of obsessive-compulsive disorder and panic disorder, regardless of the type of initial anxiety at presentation.13 A study

found a prevalence rate of OCD about 8% in patients with bipolar I disorder and 7% with bipo-lar II disorder.32 Additionally, presence of PTSD

causes bipolar patients to have a worse out-come, as assessed by their lower likelihood to recover, elevated proportion of RC periods,

increased risk of suicide attempts, strong associ-ation with mood instability and worse quality of life.33

Genetic studies have shown that there is a strong biological relationship between mood dis-orders and psychotic disorders. It is consistent with a relatively specific genetic predisposition to the disease, which has both distinct character-istics of schizophrenia and bipolar disorder (i.e., a mixed psychosis or a broadly defined schizo-affective disease).34

Findings support the impression that the clinical nature of the onset of BD is strongly predictive of later types, amounts, and patterns of morbidity. The polarity of first episodes of BD appears generally to predict later, long-term predomi-nance of depressive or manic recurrences.35

BD-II type is found more likely to present initially in depression as well as psychosis or mania.13

De-pressive episodes occur more frequently when a BD starts with a depressive episode.15 When the

first episode starts with depression, a RC course is more prevalent;36 depressive episodes tend to

predominate the following course of the disor-der15 and suicide attempts are more prevalent.37

Kassem et al. demonstrated that first-episode polarity inclines to run in families, and is a helpful way to detect patients with homogeneous sub-types of BD.38 Nonetheless, few studies

investi-gated the effects of the first-episode polarity on the clinical course of BD, which can comprise delays in diagnoses and suicide.

It is stated that early episodes of a major psychi-atric illness prior to typical mania or depression can include psychotic episodes.39 Initial forms of

the first major episodes may contribute to an increased impression that early morbidity can predict the future morbidity and the nature and extent of its course or pattern.13 When

first-epi-sode is psychotic in bipolar patients, the illness course is expected worse than non-psychotic ones, and these patients demonstrate signify-cantly more positive symptoms, thought disorder and paranoia than unipolar depressed patient controls.40

Goikolea et al. showed that cases with seasonal pattern have a considerably elevated number of major depressive episodes and were more likely to meet the criteria for BD II subtype. These results highlight that amongst mood disorders, BD may be a subtype more inclined to seasonal pattern.41

The higher risk for alcohol dependence in those with comorbid anxiety disorder42 and the higher

rates of substance use disorders (SUDs) in bi-polar I than in bibi-polar II disorder is also reported in studies with bipolar patients.43 Earlier onset of

first hypomania/mania was related with en-hanced risk for lifetime SUDs. More importantly, the time to the initial mood stabilizer treatment was negatively associated with the risk for recent SUDs as a sign of the correct diagnosis and treatment of bipolar disorder. It is suggested that early diagnosis and appropriate treatment with mood stabilizer in BD may reduce the risk of SUD.32

The presence of personality disorder was asso-ciated with the negative course of BD was signi-ficantly related to a history of child abuse, early age of onset, an anxiety disorder comorbiddi-ty, RC, and 20 or more previous episodes.44

Etain et al. found complex traumatic events in early childhood of RC bipolar patients than cont-rols.45 Garno et al. reported high prevalence of

childhood abuse and neglect, emotional abuse, physical abuse, emotional neglect, sexual abuse and physical neglect in bipolar patients.46

Limitations and strengths

The cross-sectional nature of the study, the fact that the cases were evaluated once and selected from a center were the limitations. Another limitation is that patients with BD not otherwise specified are not included in the study.

This study will contribute to the literature in terms of revealing and better understanding of clinical picture and risk factors of RCBD. In addition, this study was the first to evaluate RCBD in a psychiatric outpatient clinic of a general hospital in Turkey.

Conclusions

The presence of RC in the previous 12 months was found correlated with specific clinical features closely related to worse outcome in the course of BD. However, some of these corre-lations are still controversial, and many types research have been criticized regarding aspects such as lack of a standardized definition of RC and use of heterogeneous samples. So, more investigations in a prospective design are re-quired to elucidate which factors are correlated with the presence of RC in standardly defined homogeneous BD samples.

Acknowledgement: We thank Prof. Dr. Çiçek HOCAOĞLU for her support throughout the study.

REFERENCES

1. Carvalho AF, Dimellis D, Gonda X, Vieta E, Mclntyre RS, Fountoulakis KN. Rapid cycling in bipolar disorder: a systematic review. J Clin Psychiatry 2014; 75:e578-86.

2. Calabrese JR, Shelton MD, Rapport DJ, Kujawa M, Kimmel SE, Caban S. Current research on rapid cycling bipolar disorder and its treatment. J Affect Dis 2001; 67:241-255.

3. American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fifth Edition (DSM-5). Arlington: American Psychiatric Publishing, 2013.

4. Coryell W, Solomon D, Turvey C, Keller M, Leon AC, Endicott J, et al. The long-term course of rapid-cycling bipolar disorder. Arch Gen Psychi-atry 2003; 60:914-920.

5. Dunner DL, Fieve RR. Clinical factors in lithium carbonate prophylaxis failure. Arch Gen Psychi-atry 1974; 30:229-233.

6. Mackin P. Rapid cycling is equivalently prevalent in bipolar I and bipolar II disorder, and is asso-ciated with female gender and greater severity of illness. Evid Based Ment Health 2005; 8:52. 7. Kupka RW, Luckenbaugh DA, Post RM, Suppes

T, Altshuler LL, Keck PE Jr, et al. Comparison of

rapid-cycling and non-rapid-cycling bipolar disor-der based on prospective mood ratings in 539 out-patients. Am J Psychiatry 2005; 162:1273-1280. 8. Yildiz A, Sachs GS. Characteristics of rapid

cycling bipolar I patients in a bipolar speciality clinic. J Affect Disord 2004; 79:247-251.

9. Schneck CD, Miklowitz DJ, Miyahara S, Araga M, Wisniewski S. Gyulai L, et al. The prospective course of rapid-cycling bipolar disorder: findings from the STEP-BD. Am J Psychiatry 2008; 165:370-377.

10. McElroy SL, Altshuler LL, Suppes T, Keck PE, Frye MA, Denicoff KD, et al. Axis I psychiatric comorbidity and its relationship to historical illness variables in 288 patients with bipolar disorder. Am J Psychiatry 2001; 158:420-426.

11. Cruz N, Vieta E, Comes M, Haro JM, Reed C, Bertsch J, et al. Rapid-cycling bipolar I disorder: course and treatment outcome of a large sample across Europe. J Psychiatr Res 2008; 42:1068-1075.

12. Hays JC, Krishnan KR, George LK, Blazer DG. Age of first onset of bipolar disorder: demographic, family history, and psychosocial correlates. Depress Anxiety 1998; 7:76-82.

13. Balderassini RJ, Tondo L, Visioli C. First-episode types in bipolar disorder: predictive associations with later illness. Acta Psychiatr Scand 2014; 129:383-392.

14. Undurraga J, Baldessarini RJ, Valenti M, Pacchia-rotti I, Vieta E. Suicidal risk factors in bipolar I and II disorder patients. J Clin Psychiatry 2012; 73:778-782.

15. Daban C, Colom F, Sanchez-Moreno J, García-Amador M, Vieta E. Clinical correlates of first-epi-sode polarity in bipolar disorder. Compr Psychi-atry 2006; 47:433-437.

16. Hajek T, Hahn M, Slaney C, Garnham J, Green J, Ruzickova M, et al. Rapid cycling bipolar disor-ders in primary and tertiary care treated pa-tients. Bipolar Disord 2008; 10:495-502. 17. Koukopoulos A, Sani G, Koukopoulos AE, Minnai

GP, Girardi P, Pani L, et al. Duration and stability of the rapid-cycling course: a long-term personal follow-up of 109 patients. J Affect Disord 2003; 73:75-85.

18. Gigante AD, Bareboim IY, Dias RS, Toniolo A, Mendonça T, Miranda-Scippa Â, et al. Psychiatric and clinical correlates of rapid cycling bipolar disorder: a cross-sectional study. Revista Bra-sileira de Psiquiatria 2016; 38:270-274.

19. Lorenzo-Luaces L, Amsterdam J, Soeller I, DeRubeis R. Rapid versus non-rapid cycling bipolar II depression: response to venlafaxine and lithium and hypomanic risk. Acta Psychiatr Scand 2016; 133:459-469.

20. Amsterdam JD, Lorenzo-Luaces L, Soeller I, Li SQ, Mao JJ, DeRubeis RJ. Short-term venlafaxine

v. lithium monotherapy for bipolar type II major depressive episodes: effectiveness and mood conversion rate. Br J Psychiatry 2016; 2008(4):359-365.

21. First MB, Gibbon M, Spitzer RL, Williams JBW. Structured clinical interview for DSM-IV-TR axis I disorders. New York: Biometrics Research Department, 2002.

22. Spitzer R, Williams J, Gibbon M. Structured clini-cal interview for DSM-III-R personality disorders (SCID-II). New York: New York State Psychiatric Institute, 1987.

23. Young RC, Biggs JT, Ziegler VE, Meyer DA. A rating scale for mania: reliability, validity and sen-sibility. Br J Psychiatry 1978; 133:429-435. 24. Karadağ F, Oral ET, Yalçın FA, Erten E. Young

mani derecelendirme ölçeğinin Türkiye’de geçerlik ve güvenilirliği. Türk Psikiyatri Dergisi 2001; 13(2):107-114.

25. Hamilton M. Hamilton Psychiatric Rating Scale for Depression. W Guy (Ed.), Assessment Manual for Psychopharmacology. Washington: Education and Welfare, 1976.

26. Akdemir A, Örsel S, Dağ İ, Türkçapar MH, İşcan N, Özbay H. Hamilton depresyon derecelendirme ölçeğinin (HDDÖ) geçerliliği, güvenilirliği ve klinik-te kullanımı. 3P Derg 1996; 4:251-259.

27. Ernst CL, Goldberg JF. Clinical features related to age at onset in bipolar disorder. J Affect Disord 2004; 82:21-27.

28. Schürhoff F, Bellivier F, Jouvent R, Mouren-Simeoni, MC, Bouvard M, Allilaire JF, et al. Early and late onset bipolar disorders: two different forms of manic-depressive illness? J Affect Disord 2000; 58:215-221.

29. Winokur G, Coryell W, Akiskal HS, Endicott J, Keller M, Mueller T. Manic-depressive (bipolar) disorder: the course in light of a prospective ten-year follow-up of 131 patients. Acta Psychiatr Scand 1994; 89:102-110.

30. Donaldson S, Goldstein LH, Landau S, Raymont V, Frangou S. The Maudsley Bipolar Disorder Project: the effect of medication, family history, and duration of illness on IQ and memory in bi-polar I disorder. J Clin Psychiatry 2003; 64;86-93. 31. Kupka RW, Luckenbaugh DA, Post RM, Leverich

GS, Nolen WA. Rapid and non-rapid cycling bipolar disorder: a meta-analysis of clinical stu-dies. J Clin Psychiatry 2003; 64:1483-1494. 32. Gao K, Tolliver BK, Kemp DE, Verdun ML,

Gano-cy SJ, Bilali S, et al. Differential interactions be-tween comorbid anxiety and substance use disor-der in rapid cycling bipolar I or II disordisor-der. J Affect Disord 2008; 110:167-173

33. Quarantini LC, Miranda-Scippa Â, Nery-Fernan-des, Andrade-Nascimento M, Galvão-de-Almeida A, Guimarães JL, et al. The impact of comorbid posttraumatic stress disorder on bipolar disorder patients. J Affect Disord 2010; 123;71-76.

34. Craddock N, O'Donovan MC, Owen MJ. Genes for schizophrenia and bipolar disorder? Implications for psychiatric nosology. Schizophr Bull 2006; 32:9-16.

35. Baldessarini RJ, Undurraga J, Vazquez GH, Tondo L, Salvatore P, Ha K, et al. Predominant recurrence polarity among 928 adult international bipolar I disorder patients. Acta Psychiatr Scand 2012; 125:293-302.

36. Perugi G, Micheli C, Akiskal HS, Madaro D, Socci C, Quilici C, et al. Polarity of the first episode, clinical characteristics, and course of manic de-pressive illness: a systematic retrospective inves-tigation of 320 bipolar I patients. Compr Psychiat-ry 2000; 41:13-18.

37. Chaudhury SR, Grunebaum MF, Galfalvy HC, Burke AK, Sher L, Parsey RV, et al. Does first epi-sode polarity predict risk for suicide attempt in bipolar disorder? J Affect Disord 2007; 104:245-250.

38. Kassem L, Lopez V, Hedeker D, Steele J, Zandi P, Bipolar Disorder Consortium NIMH Genetics initiative, et al. Familiality of polarity at illness onset in bipolar affective disorder. Am J Psychi-atry 2006; 163:1754-1759.

39. Salvatore P, Baldessarini RJ, Khalsa HM, Vas-quez G, Perez J,Faedda L, et al. Antecedents of manic versus other first psychotic episodes in 263 bipolar I disorder patients. Acta Psychiatr Scand 2014; 129:275-285.

40. Rosen C, Marwin R, Reilly JL, DeLeon O, Harris MSH, Keedy SH, et al. Phenomenology of first-episode in schizophrenia, bipolar disorder, and unipolar depression: a comparative analysis. Clini-cal Schizophrenia & Related Psychosis 2012; 6(3):145-151A.

41. Goikolea JM, Colom F, Martinez-Aran A, Sanchez-Moreno J, Giordano A, Bulbena A, et al. Clinical and prognostic implications of seasonal pattern in bipolar disorder: a 10-year follow-up of 302 patients. Psychol Med 2007; 37(11):1595-1599.

42. Mitchell JD, Brown ES, Rush AJ. Comorbid disor-ders in patients with bipolar disorder and conco-mitant substance dependence. J Affect Disord 2007; 102:281-287.

43. Regier DA, Farmer ME, Rae DS, Locke BZ, Keith SJ, Judd LL, et al. Comorbidity of mental disorders with alcohol and other drug abuse: Results from the Epidemiologic Catchment Area (ECA) Study. JAMA. 1990; 264:2511-2518.

44. Post RM, McElroy S, Kupka R, Suppes T, Helle-man G, Nolen W, et al. Axis II personality disor-ders care linked to an adverse course of bipolar disorder. J Nerv Ment Dis 2018; 206(6):469-472. 45. Etain B, Lajnef M, Henry C, Aubin V, Azorin JM,

Bellivier F, et al. Childhood trauma, dimensions of psychopathology and the clinical expression of bipolar disorders: a pathway analysis. J Psychiatr Res 2017; 95:37-45.

46. Garno JL, Goldberg JF, Ramirez PM, Ritzler BA. Impact of childhood abuse on the clinical course of bipolar disorder. Br J Psychiatry 2005; 186;121-125.