DEPARTMENT OF ENGLISH LANGUAGE TEACHING

THE EFFECTS OF USING PICTURES AS CONTEXTUAL

SUPPLEMENTS TO IMPROVE FOREIGN LANGUAGE LISTENING

COMPREHENSION

M.A. THESIS

By

Aydan IRGATOĞLU

Ankara

May, 2010

DEPARTMENT OF ENGLISH LANGUAGE TEACHING

THE EFFECTS OF USING PICTURES AS CONTEXTUAL

SUPPLEMENTS TO IMPROVE FOREIGN LANGUAGE

LISTENING COMPREHENSION

M.A. THESIS

Aydan IRGATOĞLU

Supervisor: Assist. Prof. Dr. Abdullah ERTAŞ

Ankara

May, 2010

ii

TEZ ONAY SAYFASI

Eğitim Bilimleri Enstitüsü Müdürlüğü’ne,

Aydan IRGATOĞLU’ na ait “Yabancı dil dinleme becerisi ediniminin geliĢmesi için bağlamsal kaynak olarak resimlerin kullanımının etkileri” adlı çalıĢma 22.06.2010 tarihinde, jürimiz tarafından Yabancı Diller Eğitimi Anabilim Dalında YÜKSEK LĠSANS TEZĠ olarak kabul edilmiĢtir.

Adı Soyadı Ġmza Üye (Tez DanıĢmanı): Yrd. Doç. Dr. Abdullah ERTAġ ... Üye : Yrd. Doç. Dr. Cemal ÇAKIR . ... Üye : Yrd. Doç. Dr. Hüseyin ÖZ . ...

iii

THE EFFECTS OF USING PICTURES AS CONTEXTUAL SUPPLEMENTS TO IMPROVE FOREIGN LANGUAGE LISTENING

COMPREHENSION

IRGATOĞLU, Aydan

M. A., Department of Teaching English as a Foreign Language

Supervisor: Assist. Prof. Dr. Abdullah ERTAġ

May 2010, 154 pages

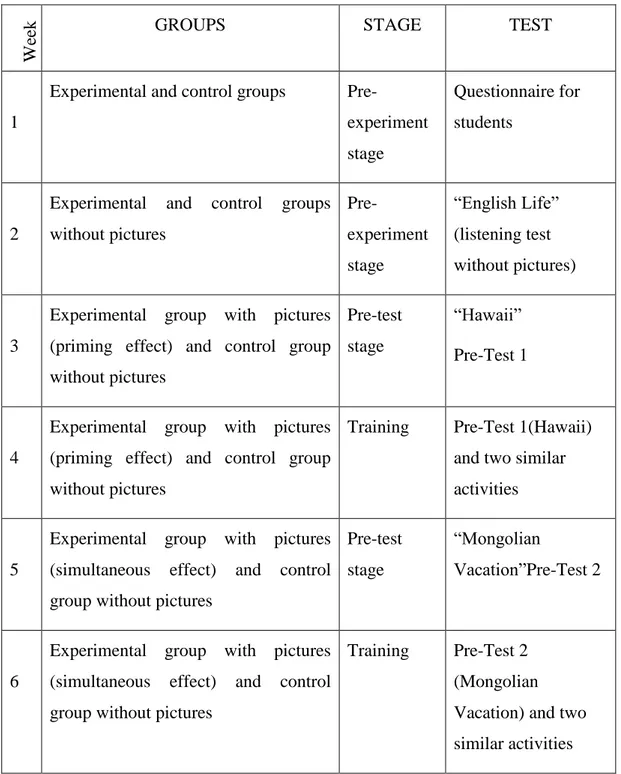

The aim of this present study is to investigate the effects of using different presentations of pictures as contextual supplements to improve foreign language listening comprehension. The study was conducted on two 9th grade classes and lasted 14 weeks, which includes pre-experiment stage, pre-test stage, training stage, post-test stage and post-experiment stage. Sivrihisar Anatolian Teacher Training High School in Sivrihisar, EskiĢehir was taken as the case school in order to collect and evaluate the data.

This study consists of five chapters. The first chapter is the introduction which gives a general background of the research study. The aim and scope of the study, significance of the problem, the hypotheses of the research and brief explanation of the methodology are provided in this chapter.

The second chapter includes the review of literature, the art of listening, listening comprehension process, comprehension process in terms of cognitive psychology, and the importance of using pictures in foreign language learning process

iv

The analysis of the data collected is presented in the fourth chapter and the results are discussed. The fifth chapter is the conclusion which also presents implications in addition to the limitations of the study.

Additionally, this experimental study includes twenty four appendices; a questionnaire for students, eight listening tests, eight transcripts of these listening texts used in tests, picture cards used for experimental group, and a sample lesson plan used in the experimental group which was presented by using priming presentation technique is given.

According to the analysis of results, four major findings are reported: Firstly, the results of the research show that using pictures as contextual supplements enhances listening comprehension better than audio-alone condition. Secondly, priming and feedback presentation techniques as methods of presenting visual cues are better when compared to simultaneous presentation technique. Thirdly, the training session helps students improve their listening comprehension. Lastly, the more the students are trained with pictures, the higher their foreign language acquisition ability is, so they can also be successful in listening comprehension process without pictures.

v

YABANCI DİL DİNLEME BECERİSİ EDİNİMİNİN GELİŞMESİ İÇİN BAĞLAMSAL KAYNAK OLARAK RESİMLERİN KULLANIMININ

ETKİLERİ

IRGATOĞLU, Aydan

Yüksek Lisans, Ġngiliz Dili Eğitimi Bölümü DanıĢman: Yrd. Doç. Dr. Abdullah ERTAġ

Mayıs 2010, 154 sayfa

Bu çalıĢmanın amacı yabancı dil dinleme becerisi ediniminin geliĢimi için bağlamsal kaynak olarak resimlerin farklı sunumlarının kullanımının etkilerini araĢtırmaktır. ÇalıĢma, iki adet dokuzuncu seviye sınıfta uygulanmıĢtır ve 14 hafta sürmüĢtür. Bu süreç deney öncesi, ön test, eğitim, son test ve deney sonrası aĢamalarını içerir. Verileri toplamak ve değerlendirmek için EskiĢehir Sivrihisar Anadolu Öğretmen Lisesi araĢtırma yapılacak okul olarak seçilmiĢtir.

Bu çalıĢma beĢ bölümden oluĢmaktadır. ÇalıĢmanın birinci bölümü giriĢ bölümüdür ve çalıĢmaya temel oluĢturan unsurlardan bahseder. Bu bölümde çalıĢmanın amacı, kapsamı, problemin önemi, araĢtırmanın hipotezleri ve kullanılan yöntem ele alınır.

Ġkinci bölüm literatür taramasını kapsar. Dinleme sanatı, dinlediğini anlama iĢlemi, biliĢsel psikoloji açıĢından anlama iĢlemi ve resimlerin yabancı dil öğrenme sürecinde kullanımın önemi konuları çalıĢılıp, detaylı bir Ģekilde açıklanmıĢtır. Üçüncü

vi

Toplanan verilerin analizi dördüncü bölümde verilmiĢtir ve elde edilen sonuçlar tartıĢılmıĢtır. BeĢinci bölüm sonuç bölümüdür. Sonuçlar ve araĢtırmanın sınırlılıkları bu bölümde verilmiĢtir.

Ek olarak, bu deneysel çalıĢmada yirmi dört ek bulunmaktadır: öğrenciler için bir anket, sekiz dinleme testi, sekiz adet dinlemede kullanılan parçaların metinleri, deney grubuyla kullanılan resimler ve deney grubunda kullanılan, resimlerin önce gösterilmesi tekniği kullanılarak hazırlanmıĢ ve sunulmuĢ olan örnek bir dinleme ders planı verilmiĢtir..

AraĢtırmanın sonuçlarının analizine göre dört temel sonuç belirtilmektedir: Birincisi resimlerin bağlamsal kaynak olarak kullanımı sadece dinlemenin kullanımına göre dinleme edinimini daha çok geliĢtirir. Ġkincisi, resimlerin dinleme etkinliklerinin baĢında ve sonunda gösterilmesi tekniklerinin kullanılması dinleme esnasında kullanılmasına göre daha etkilidir. Üçüncüsü, eğitim dönemi öğrencilerin dinleme edinimini geliĢtirmesine yardımcı olur ve son olarak, öğrenci ne kadar çok resimle öğretime maruz kalırsa, o kadar çok öğrenir ve ayrıca resimlerin kullanılmadığı durumlarda bile baĢarılı olur.

vii

It is a real pleasure to thank people who have contributed to this study. First of all, I would like to thank my thesis advisor, Assist. Prof. Dr. Abdullah ERTAġ, for his excellent guidance and his continuous patience and encouragement that I have always felt throughout the preparation of this thesis.

I would like to express my gratitude to my parents, Ahmet IRGATOĞLU and Nevin IRGATOĞLU, who provided me with love, tolerance and invaluable support throughout my thesis and throughout my life, to my sisters, Nurdan IRGATOĞLU, Handan ÖZBAY and my brother Murat IRGATOĞLU for their courage that always inspire me.

I especially owe thanks to my best friend, Ethem ĠYĠAKSU for supporting me throughout my studies whenever I needed him. He provided me with suggestions, encouragement and moral support.

I also thank my colleagues, Asuman ÖKÇÜN, Derya ÜNAL, Serpil ERDOĞAN, for their support and all teachers, experts and students for participating in the questionnaire and tests.

I am thankful to all my friends and colleagues, especially Ayça AKGÖL, Özkan KIRMIZI, and Selim Soner SÜTÇÜ, for their support, friendship, patience to listen to me and encouragement.

viii

TEZ ONAY SAYFASI ... ii

ABSTRACT ……….…. iii

ÖZET ……….………….… v

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS ………...… vii

TABLE OF CONTENTS ………... viii

LIST OF TABLES ………...….... xii

LIST OF GRAPHS ………...………...xiii

CHAPTER ONE: INTRODUCTION……….…….1

1.1 Problem………..………. 1

1.2 The Purpose of the Study ………...…… 2

1.3 Significance of the Problem ………..……...…. 3

1.4 The Hypotheses of the Research..……….……. 4

1.5 The Scope of the Study ………...………..……. 5

1.6 Limitations of the Study ...6

1.7 The Definition of Terms……….…….... 7

CHAPTER TWO: REVIEW OF LITERATURE ……….…………..…9

2.0 Introduction ………...………...……. 9

ix

2.2.2 Listening Comprehension in Foreign Language Learners …………...…14

2.2.3 Historical Background of Listening Comprehension………..……....…15

2.2.4 Factors That Affect Listening Comprehension………...………...18

2.2.5 Different Components of Listening Comprehension ………..……...…20

2.2.6 Stages of Listening Comprehension Process………..……….…22

2.2.6.1 Pre-Listening ……….……….... 22

2.2.6.2 While-Listening ……….………25

2.2.6.3 Post-Listening………....….27

2.3 Comprehension Process in Terms of Cognitive Psychology………..……...29

2.3.1 The Importance of Background Knowledge and Use of Pictures in Comprehension Process……...………..…...29

2.3.2 Foreign Language Listening in Cognitive Psychology…….………... 32

2.3.2.1 Schema Theory………...………... 34

2.3.2.2 Dual Coding Theory ………...……… 39

2.4 The Importance of Using Pictures in Foreign Language Learning Process ……… 41

2.4.1 Priming Presentations ……..……….………. 45

2.4.2 Feedback Presentations …..……….………. 46

CHAPTER THREE: METHODOLOGY ………...….. 49

3.0 Introduction …...……….... 49

3.1 Research Questions ………...…....50

x

3.5 Data Collection Procedure ………...…... 56

CHAPTER FOUR: RESULTS AND DISCUSSION ………64

4.0 Introduction ……….………… 64

4.1 Results ………...…...…….. 64

4.2 Discussion ………...…...……... 80

CHAPTER FIVE: CONCLUSION AND SUGGESTIONS...…………...… 85

5.0 Introduction ………..85

5.1 Conclusion ..………..85

5.2 Implications for Educational Practice ………...…89

5.3 A Suggested Lesson Plan ..………...91

REFERENCES ……….……99

APPENDICES ………..……… 117

Appendix 1: Questionnaire for Students ……….…... 117

xi

Appendix 5: Hawaii (Transcript) ……….……….…....…123

Appendix 6: Hawaii (Pictures for Experimental Group)………...125

Appendix 7: Mongolian Vacation (Pre-Test 2) ……….…...…127

Appendix 8: Mongolian Vacation (Transcript) ……….…...128

Appendix 9: Mongolian Vacation (Pictures for Experimental Group) ....……….…...130

Appendix 10: What Are You Addicted to? (Pre-Test 3)………..132

Appendix 11: What Are You Addicted to? (Transcript) ……….……....…133

Appendix 12: What Are You Addicted to? (Pictures for Experimental Group).…….135

Appendix 13: Movies (Post-Test 1) ……….…....…137

Appendix 14: Movies (Transcript)………....138

Appendix 15: Movies (Pictures for Experimental Group) ..……….………140

Appendix 16: Jobs (Post-Test 2) ………..…142

Appendix 17: Jobs (Transcript) ...……….……143

Appendix 18: Jobs (Pictures for Experimental Group)………...145

Appendix 19: Dream House (Post-Test 3) ..……….………147

Appendix 20: Dream House (Transcript) ……….……148

Appendix 21: Dream House (Pictures for Experimental Group)………..150

Appendix 22: Night Life (After Experiment Test) ...……….………152

xii

Table 1: AA and AP Conditons of the Study ……….55

Table 2: The Whole Process of the Experiment ……….62

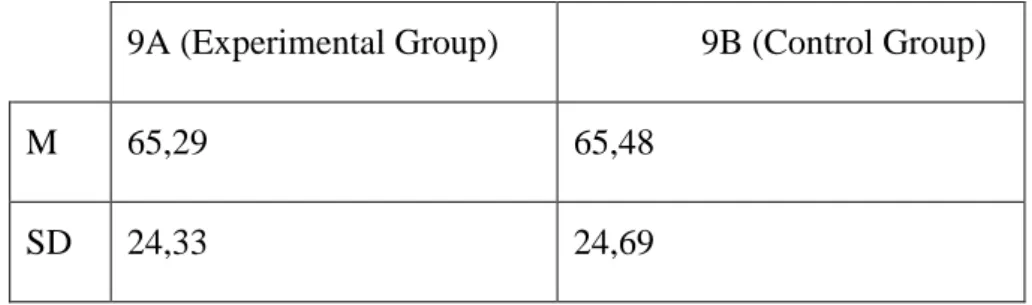

Table 3: Results of the Pre-Experiment Test ……….……… 70

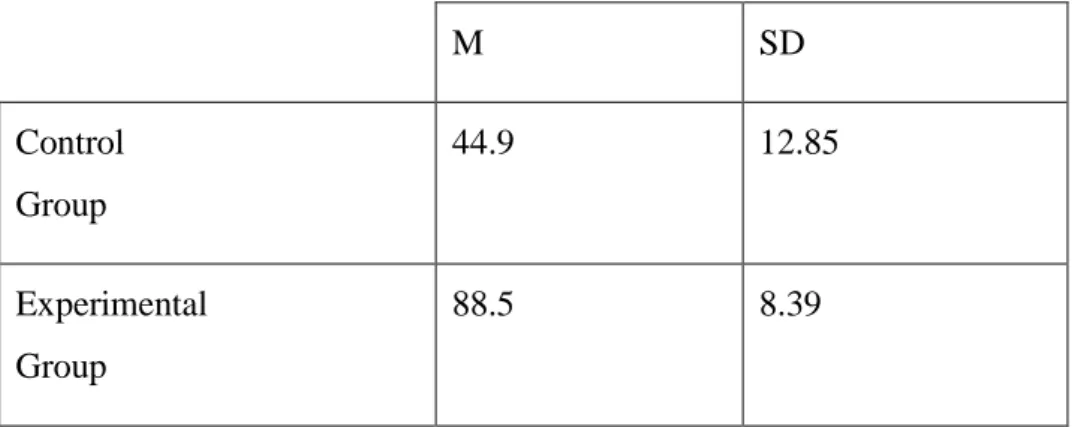

Table 4: Comparison of Pre-Test and Post-Test Scores (Independent Sample t-Test)...71

Table 5: Comparison of Three Different Presentation Techniques (OneWay ANOVA)75

xiii Graph 1: Question 1 ………65 Graph 2: Question 2 ………65 Graph 3: Question 3 ………66 Graph 4: Question 4 ………67 Graph 5: Question 5 ………67 Graph 6: Question 6 ………68 Graph 7: Question 7 ………69 Graph 8: Question 8 ………69

Graph 9: Comparison of Test-Time and Instruction Conditions ………73

Graph 10: Comparison of Test-Time and Different Presentation Techniques ……...…78

CHAPTER ONE

INTRODUCTION

This thesis examines the effects of using pictures as contextual supplements to improve foreign language listening comprehension. It also examines the different presentation techniques of using pictures. This chapter consists of seven sections: the problem, the purpose of the study, the significance of the problem, the hypotheses of the research, the scope of the study, limitations of the study and the definition of terms.

1.1 Problem

The use of multimedia, which combines several different methods of giving information such as text, picture, video or sound, has developed rapidly by influencing various realms of learning and teaching. How to integrate the multimedia technology into language learning effectively is central to particular language instructors‘ and learning tool producers‘ interests (Meskill, 1996). However, there is just a little empirical research applying the special functions of multimedia technology in improving foreign language listening comprehension. According to the studies, listening comprehension is facilitated by a number of factors such as presenting contextual visuals (Baltova, 1994; Bransford & Johnson, 1972; Chung, 1994; Herron, Morris, Secules, & Curtis,1995; Herron, Hanley, & Cole, 1995a; Mueller, 1980; Rubin, 1990; Secules, Herron, & Tomasello , 1992 ; Thompson & Rubin, 1996); giving aural information (Chung & Huang, 1998); previewing questions and pre-teaching

vocabulary (Chung, 2002); summarised sentences (Herron,1994; Herron et al., 1995a; Herron, Cole, York, & Linden, 1998); talking about titles and topics (Bransford & Johnson, 1972); and asking question (Herron, Corrie, Cole, & Henderson, 1999). According to most of studies, when contextual cues are presented before listening to the spoken text, listening comprehension is improved more.

Most of the EFL students tend to understand the delivered message using only its linguistic features although communication usually comprises not only linguistic but also non-linguistic elements. Delivered messages consist of not only oral information but also paralinguistic information which shows manner of the speakers and visual information set in communicative atmosphere (Chung, 1994; Dunkel, 1986; Rivers, 1981; Ur, 1984). To facilitate foreign language listening comprehension, both linguistic and non-linguistic elements of communication are to be taken into consideration. However, non-linguistic features have not been employed effectively in accordance with learners‘ language proficiency to improve listening comprehension in particular in EFL classrooms in Turkey.

1.2 The Purpose of the Study

The primary purpose of the present study is to specify the role and effects of using pictures as contextual supplements in improving foreign language listening comprehension. Within this framework, theoretical issues will be examined arising from the application of using pictures that may facilitate foreign language listening comprehension. In short, the effects of using still images will be investigated using students‘ language proficiency where three different presentation techniques such as priming, simultaneous, and feedback presentations are applied respectively.

1.3 Significance of the Problem

All skills are interconnected. As a skill, listening both forms a basic part of communication in native language and naturally plays a crucial role in developing foreign language learning or acquisition (Postovsky, 1981; Rivers, 1981; Winitz, 1981). Although the role of listening in foreign language learning is emphasized by some teaching methods such as the Direct Method, TPR, and the Natural Approach, just a little experimental research has been done showing the types of useful listening activities in foreign language listening comprehension (Chung, 1994).

Some studies (Bransford & Johnson, 1972; Dean & Enemoh, 1983; Hudson, 1982; Mueller, 1980; Omaggio, 1979; Wolff, 1987) suggest that the use of pictures facilitates listening comprehension based on schema theory because of attitudinal change and increased awareness about listening comprehension. However, Friedman & Stevenson (1980), Gildea, Miller & Wurtenberg (1988), Klein (1985) suggest that the relevant factors for effective use of visual cues are to be investigated due to the fact that all students do not benefit from the same picture equally, that picture may suggest different meanings to each student because of their background. Other researchers (Bransford, & Johnson, 1972; Dean & Enemoh, 1983; Hudson, 1982; Mueller, 1980; and Omaggio, 1979) claim that when a picture is organised and shown before listening, the learners construct the proper scheme required to comprehend the information contained in the text easily, so this facilitates the comprehension and remembering.

The development of media technology has influenced the studies about the effects of pictures in foreign language listening comprehension. It is claimed that the use of pictures as contextual supplements in listening comprehension motivates the students, takes their attention on the subject, and also improves foreign language listening comprehension (Baltova, 1994; Chung, 1994; Hennessey, 1995; Secules et al., 1992; Thompson & Rubin, 1996). These studies also show that the effectiveness of pictures may be strongly dependent upon a number of factors, such as the selection of pictures including sufficient contextual clues (Rubin, 1990); the degree of difficulty of the spoken

text (Wolff, 1987); students‘ language proficiency (Mueller, 1980); the types of the questions about the listening text (Secules et al., 1992); and the period of exposure to pictures (Herron, 1994). According to the studies of Herron (1995, and Herron, et al. (1995a) pictures as visual cues presented in advance facilitate comprehension. Thus the use of pictures as contextual supplements in foreign language listening comprehension is now widely recommended.

However Tuffs & Tudor (1990), and Glenn (1989) reject the effectiveness of pictures in foreign language listening comprehension. They suggest that pictures may not be effective contextual supplements all the time or that listening skills are not based on visual elements which may confuse them. Friedman & Stevenson (1980) also claim that some drawings and pictures in children‘s books are represented in a manner which is beyond their cognitive development or cultural experience. Therefore, knowing what types of visual cues are more effective and when they should be presented most effectively will be helpful for learners as well as for selection of appropriate media for teachers.

Since the way in which pictures as contextual supplements affect foreign language listening comprehension and information processing is emphasized recently, and the understanding has grown, more appropriate application of visual information for language or information processing will result in improved language listening comprehension as well as improved synthetic language teaching and learning.

1.4 The Hypotheses of the Research

As listening is one major source of input necessary for the learning of foreign languages, EFL students in Turkey need to develop their listening skills. Therefore, the importance of this study is great since four hypotheses were tested to ascertain the effects of pictures in listening comprehension to develop this skill. These research questions

aimed to find out whether the presentation of pictures as contextual supplements and the application of different presentation techniques were helpful for effective foreign language listening comprehension.

The hypotheses of this study are:

1. Listening comprehension will increase more when pictures are used than when no pictures are used.

2. Listening comprehension will increase more when pictures are presented using a combination of priming and feedback techniques than using simultaneous technique. 3. Listening comprehension will increase for both groups as a result of the intensive

training.

4. When learners are trained with pictures, they function better in listening tasks that are not accompanied by pictures.

1.5 The Scope of the Study

This study evaluates the effects of using pictures as contextual supplements in foreign language listening comprehension. Although using pictures facilitates the comprehension of the spoken text, there exists little data about the effects of different presentation techniques of using pictures. The students‘ language proficiency and the clarity of the spoken text are to be taken into consideration. When it is compared to other skills, in listening skill the texts are more synthetically complex and have less paralinguistic cues, less redundant, denser and use fewer pauses which make the comprehension hard (Rubin, 1994).

This study is divided into five parts. Chapter 2 reviews the characteristics of listening comprehension and comprehension process in terms of cognitive psychology. Chapter 3 describes the experiment related to the research. Chapter 4 includes the results and general discussion, and Chapter 5 includes conclusions from the results of the

experiment, implications for educational practice, and recommendation for further studies.

Chapter 2, the review of literature, identifies conceptual basis of listening and listening comprehension process in first and foreign language learning. It also gives information about the historical background of listening comprehension, factors that affect listening comprehension and components and stages of listening comprehension process. Then, it presents comprehension processes in cognitive psychology on the basis of dual coding and schema theory while focusing on the importance of background knowledge and using pictures as contextual enrichment. It also contains the effects of different presentation techniques of using pictures in language learning.

Chapter 3 describes a 14 week experiment, which compares the visual group with the audio alone group and different presentation techniques (priming, simultaneous, feedback techniques). In this experiment, pre-tests and post-tests were administered and repeated measure experimental design, independent samples t-test and one-way ANOVA were used for analysing the collected data.

Chapter 4 includes the analysis of results of the pre/ post-tests with graphics and tables and general discussion of the study. Finally, Chapter 5 includes conclusion from the results of the experiment. Implications for educational practice and recommendations are also included in chapter 5.

1.6 Limitations of the Study

The limitations of the study are listed below:

part in the study. It is not clear whether the same results would be obtained or not in case this study would be carried out with other schools or with more than 60 students.

2. The results of the tests depend on the atmosphere that these activities were carried out. We wonder whether the results would be the same if more relaxed atmosphere was provided for the learners.

3. The degree of the learners‘ comprehension of listening texts was limited by using only three types of test items such as fill-in-the-blanks, multiple- choice and true/false items in the present study. Thus, it is wondered whether the results would be the same or not if other than three types of tests were added to the tests.

1.7 The Definition of Terms

Contextual materials: Visual images (line drawing, animation, picture, moving images, caricature, etc.) that provide additional information to help listeners to comprehend the content of the spoken message.

Paralinguistic Cues: Nonverbal elements such as intonation, body posture, gestures, and facial expression, which modify the meaning of verbal communication.

Schema: A generalized description or a conceptual system for understanding knowledge.

Schema Theory: A theory which states that all knowledge is organized into units called schema.

verbal information are processed differently and along district channels with the human mind creating separate representations for information processed in each channel.

Priming Presentation: Showing pictures to the learners before listening to the spoken text.

Feedback Presentation: Showing pictures to the learners after listening to the spoken text.

Simultaneous Presentation: Showing pictures to the learners during the listening process.

Static Image: Picture

AA Condition: Audio-Alone Condition

CHAPTER TWO

REVIEW OF LITERATURE

2.0 Introduction

This chapter will focus on the listening comprehension theory. First and foreign language listening studies will be examined. Foreign language listening comprehension research based on historical background, the factors which make listening comprehension difficult, different components of listening comprehension and the stages of teaching listening comprehension will be dealt with. Then, comprehension processes in aspects of cognitive psychology will be considered by using the comprehension theory. This theory is connected with dual coding and schema theory. Dual coding theory attempts to give equal weight to verbal and non-verbal processing, so it states that information can be processed through both verbal and non-verbal cues. The role of background knowledge in language learning has been formalized as schema theory. It shows how pictures as contextual supplements may help learners to improve their listening comprehension. In this study, both of the theories are explained in the use of contextual supplements such as pictures to assist listening comprehension.

It is stated that a spoken message presented with non-verbal cues and visual information could assist and facilitate learners‘ listening comprehension (Chung, 1994; Dunkel, 1986; Herron, 1994; Herron et al., 1995; Meskill, 1996; Omaggio, 1979; Rivers, 1981; Rubin, 1990; Secules et al., 1992; Snyder & Colon, 1988; Ur, 1984; Wolff, 1987). Although such an idea is common; in fact, there has been little research to

investigate whether or not it is true. Some researchers (Gildea, Miller, & Wurtenburg, 1988; Ur, 1984) claim that pictures may distract learners when they are presented with spoken message. The experimental evidence of the research based on the schema theory shows that picture cues facilitate the learners‘ comprehension of the aural information and it is claimed by Mueller (1980) that the learners‘ listening comprehension develops when picture cues are shown before and immediately after the presentation of the listening text.

2.1 The Art of Listening

Listening is the first and the most important of the four skills that learners of a foreign language should develop. When individuals are born, they start to listen. They listen to every kind of sound around them, and then they try to make sense out of the sounds they hear. Afterwards, they learn speaking, reading and writing skills. Lundsteen (1979; p.11) expresses this process as follows: ―Children listen before they speak, speak before they read, and read before they write.‖ Thus, one‘s speaking, reading and writing abilities are directly or indirectly dependent on the ability to listen.

The term ―listening‖ can be defined in several ways. Nichols, one of the early scholars of listening, defines it as ―... the attachment of meaning to aural symbols‖ (Wing, 1985; p.14). For Jones, listening is a selective process by which sounds communicated by some source are received, and acted upon by a purposeful listener (Wing, 1985; p.14). Underwood (1989; p.1) defines listening as ―... the activity of paying attention and trying to get meaning from something we hear.‖ And he states that ―listening is the ability to identify and understand what others are saying.‖

Briefly, listening can be defined as the absorption of the meanings of words and sentences by the brain. Listening leads to the understanding of facts and ideas. It requires concentration, which is the focusing of thoughts upon one particular problem.

A person who incorporates listening with concentration is actively listening.

2.2 Listening Comprehension Process

Listening process is complicated in that it involves listener‘s experience and knowledge in addition to the interaction with the speaker to arrive at meaning (O‘Malley, Chamot and Kupper, 1989). Comprehension of a high amount of oral input is necessary for second language learning process. Listening is not only the primary means whereby most people learn to communicate in their mother tongue but also a substantial part of developing foreign language (Postovsky, 1981; Rivers, 1981; Winitz, 1981). Hasan (2000) defined ‗listening‘ as a process of just listening to the message without interpreting and responding to the text, and ‗listening comprehension‘ as a process which includes the meaningful interactive activity to understand the text. According to Hasan (2000), listening comprehension is the same as the second language acquisition theory which regards listening comprehension as an active and complex process whereby listeners select information from the auditory and/or visual clues and relate this information to existing knowledge in their long-term memory for better understanding and comprehending what they hear (Byrnes, 1984; Howard, 1983; O‘Malley, Chamot, & Kupper, 1989; Richards, 1985). Coakley & Wolvin (1986) described listening as on-going complex processes of communication activities that occur in the internality of the listener. Listening is also regarded as a skill to be developed separately from other skills (Mead, 1985), and as a ―unique ability‖ (Bostrom, 1990; p. 12).

Listeners generally have difficulty in comprehending the spoken text, especially if it is spoken by a native speaker. Chastain (1976) maintains that to understand a native speakers‘ speech, listeners do not have to understand each word and all of the details in the text. Instead, they should focus on the content of the message in a natural situation and try to guess the unknown words from the context of the spoken text by using their background knowledge and relating their prior knowledge or schemata to

the new information in the spoken text. It is vital for the teacher to know that the students come to the listening comprehension process with different backgrounds (Young, 1997). Students‘ comprehension is further influenced by several factors such as beliefs, attitudes, and biases. Therefore, learners need to be ready for what they are going to hear for better comprehension. Because of that reason, the purpose of listening comprehension activities in English foreign language classroom should be to help listeners deduce the meaning of complicated words or ideas from the verbal and non-verbal information to make them analyze, evaluate, synthesize, and organize critically what has been heard. This helps learners recognise cultural differences between the first language and foreign language and remove the cultural misunderstandings that may be induced from the delivered non-verbal information because, according to Faerch & Kasper (1986; p.264), ―comprehension takes place when input and knowledge are matched against each other‖.

To make the foreign language listening comprehension process easier, teachers should help listeners activate their schemata and background knowledge related to the spoken text by enabling connections between listeners‘ prior knowledge schemata and new information by using cues such as pictures to motivate them and to arouse their interest (Baltova, 1994; Bransford, & Johnson, 1972; Hasan, 2000; Hennessey, 1995; Omaggio, 1979; Secules et al., 1992; Thompson & Rubin, 1996), as well as topic or titles (Bransford, & Johnson, 1972; Omaggio, 1979; Schallert, 1976).

2.2.1 Listening Comprehension in Native Speakers

When listening to the native language, listeners usually do so at speed and without any effort. They try to focus on the meaning rather than on the language or sounds produced by the speakers. Perceiving the speech sounds does not seem problematic, except in unusual circumstances as noise or unfamiliar accent of the speaker. The listeners use their knowledge of phonological regularities of their language, its lexicon, and its syntactic and semantic properties to compensate for the

shortcomings of the acoustic signal (Anderson & Lynch, 1988), so in describing listening, the importance of hearing, attending, comprehending and remembering, should be taken into consideration (Mead, 1985).

Individual variables affect all aspects related to listening comprehension. No two individuals are the same, so all the theories related to listening can be applied differently according to individual variables. According to Bostrom (1990), the individual ability to receive and retain aural information is various in his native language listening comprehension. Different resources draw different individuals‘ attention because they vary among individuals. ―Non-cognitive factors such as affective meaning, situational and cultural factors, physical settings, nonverbal signals, and motivational and attitudinal factors mediate the listening processes‖ (Schwartz, 1992, p. 28), and as Mead (1985) maintains such non-cognitive factors should be taken into account in studying listening.

Listening is the first language skill that children acquire, so it has a crucial role in learning. Asher (cited in Morley, 1990) showed that average children by age six have spent about 33 % of their time for listening to their native language, and Rivers (cited in Gilman and Moody, 1984, p. 331) claimed that most adults have spent 40 / 50 % of their communication time for listening. Coakley & Wolvin (cited in Schwartz, 1992) reported that students listened to about 57 % to 90 % of their in-school information from their teachers and their schoolmates. On the basis of these results, the importance of listening comprehension has been recognised when it is compared to the other skills.

Listening comprehension has been traditionally believed as a passive skill for many years, but recently it has been considered as an active process (Anderson and Lynch, 1988: 4). It is a ―highly complex problem-solving activity‖ (Byrnes, 1984; p. 318), where information is used to solve problems. Samuels (1987) also regards the comprehension of spoken language as a process where the listener must construct meaning from the information provided by the speaker. It is difficult to think that it is a one-sided action, which means that the task to comprehend a spoken text belongs both

to the speaker and to the listener. The relationship between oral and aural is affected by the nature of the speaker‘s message and the listener‘s control over the received message. This control over the received message, forces listeners to process the message immediately, whether he or she is ready to receive the message or she is still processing the message (Danks & End, 1987).

2.2.2 Listening Comprehension in Foreign Language Learners

Although the importance of listening comprehension in learning foreign language has been emphasized, there is relatively little research on it (Brown, 1992; Goh, 1997). Because of this reason, most of the information on foreign language listening comprehension derives from studies done on first language learning (Anderson & Lynch, 1988; Devine, 1978, 1967; Duker, 1964; Dunkel, 1991; Keller, 1960).

In the foreign language context, the listening comprehension process is more complex than the first language comprehension process because the listeners cannot control the language completely as ―comprehending the spoken form of the target language is one of the most difficult tasks for a foreign language learner‖ (Paulston & Bruder, 1976; p. 127). Rivers (1981) agrees and states that the speed rate and the immaterial features of spoken utterance make listening comprehension difficult. If the vocabulary, structural complexity, and speed of the spoken text cannot be controlled by the listeners, the listening comprehension process becomes more difficult, so the listeners need more fluent communication skills (Nord, 1981).

Listening comprehension in foreign language learning can also be regarded as an invisible process (Lewis, 1999, p. 134) and as an ―active process in which listeners choose and comprehend the information which comes from auditory and visual cues in order to define what is going on and what the speakers are trying to express‖ (Rubin, 1995, p.7). Due to the invisibility of the listening process, only the results of this process

can be visible (Lewis, 1999) and comprehension involves a constructive process to understand and remember what is said (Harley, 2001). Namely, listening comprehension can be defined as a continuous process to comprehend the delivered message and to store it in long-term memory (Antes, 1996; Gassin, 1992; Hurley, 1992).

Some studies found that intelligence was strongly related to the foreign language learning and claim that intelligence levels affect the success of the learners, but Lightbown and Spada (1995) claimed that all learners may improve their listening comprehension skill individually because listening comprehension may not be affected by intelligence. Mead (1985) showed that listening comprehension is related with verbal aptitude, and also claimed that listening comprehension played a significant prediction role in reading comprehension and in the performance of aptitude and achievement tests. So, the importance of listening comprehension should not be ignored in teaching a foreign language.

2.2.3 Historical Background of Listening Comprehension

Listening comprehension has been considered as the least significant and passive skill for many years (Nunan, 1998) because listening process could not be observed directly. However, listening has recently been considered as an active skill which facilitates the emergence of other language skills (Vandergrift, 1999). Listeners are thought to be involved actively in communication process because they use their background knowledge of the world and of language to recreate the speaker‘s message.

Listening skill was neglected till 1960s. With the high influence of audio lingual method, listening provided the input for imitation of a short speech segment. That is, listening was used in the foreign language classes largely to teach oral production but not as a skill to be taught for its own sake. Nord (cited in Winitz, 1981, p.69) agrees with this idea in the following words:

Audiolingualism places listening first in the sequence of language skills, the listening that has taken place has been largely a listening for speaking rather than listening for understanding.

Although the audio-lingual method is still practiced today, it has been criticised a lot since it regarded listening primarily as a means of habit formation. The proponents of this method were mainly interested in form rather than the messages in the dialogues, so language learning consisted of practising structures that were explicitly presented to the learner. As a result, the learners were unable to apply the habits they had learned in the classroom to the real life (Richards & Rodgers, 2001). As a reaction to the behaviourist features of Audio Lingual Method, Chomsky argued that language could not be acquired through habit formation because people create and understand an infinitive number of novel utterances. Chomsky put an emphasis on human cognition and adopted a mentalist view related to the basic principles of cognitive psychology (Chastain, 1976). This view led to the Cognitive Approach which showed that language learners could form rules which allow them to understand and create utterances they have never heard before rather than simply being responsive to stimuli in the environment (Larsen-Freeman, 2000). Gattegno‘s Silent Way shares certain principles with Cognitive Approach, one of which was that teaching does not dominate the learning process but serves it (Larsen-Freeman, 2000). Suggestopedia, also known as ―Desuggestopedia‖, was developed by Lozanov (Larsen- Freeman, 2000: p. 73). This approach aimed to overcome psychological barriers to learning and help the learners to acquire a language at a much faster rate (Sarıçoban, 2001).

Most methods and approaches mentioned above placed primary emphasis on the development of speaking skills rather than listening skills, but it is claimed that attempting to speak before listening comprehension is acquired may cause problems in speaking (Asher, 1982; Postowsky, 1981). In the 1960s and 1970s, the idea that language learning should begin first with comprehension-based activities and later proceed to oral-based activities (Winitz, 1981) became widespread. From 1970s till 1980s, the role of listening comprehension began to be investigated by some language researchers like

Asher, Belasco, Krashen, Terrell, Postowsky, Winitz and Reeds because they stated that there is considerable amount of evidence that there is great positive transfer from listening to other language skills, including speaking. They have argued and demonstrated that foreign language instruction should begin with large amounts of practice in comprehending the target language and speaking should be delayed until a substantial base of receptive competence is gained. Some second language acquisition researchers (e.g., Brown, 1986; Long, 1985; cited in Wu, 1993) also began to look into listening and interaction, meaning negotiation, input, intake and output. The role of listening comprehension in learners‘ strategies as well as the nature of listening and the information processing it involves were increasingly investigated in terms of cognitive psychology, which emphasised ‗top-down‘ and ‗bottom-up‘ processing (e.g., Adams & Collins, cited in Wu, 1993; Anderson, 1990; O‘Malley, Chamot, Stewner- Manzanares, Kupper & Russo, 1985; O‘Malley, Chamot, & Kupper, 1989).

In some teaching methods, primary emphasis was put on the development of listening comprehension (Larsen- Freeman, 2000). In Asher‘s Total Physical Response methodology, learners respond with their bodies to the commands without speaking (Richards & Rodgers, 2001). Krashen and Terrell‘s also give importance to primarily listening comprehension in their Natural Approach. They claim that comprehension precedes production (Krashen & Terrell, 1983 cited in Wu, 1993). Postowsky (Morley, 1984, p.14) emphasizes the priority of listening with an explicit delay in oral production. Similarly, in Winitz and Reed‘s ―Self-Instructional Programme‖ and Winitz‘ ―The Learnable‖, learners listen to words, phrases and sentences while they are looking at accompanying pictures. The meaning of the utterance is clear in the context the picture provides. The Lexical Approach, which was developed by Lewis (1993), was more concerned with students‘ receiving plentiful comprehensible input rather than their production. All these programmes provide listening comprehension first; speaking is delayed until the learners are ready.

Recently, the importance of listening comprehension in foreign language acquisition has gradually been emphasized. Although listening comprehension had been

neglected and considered as a passive skill, it has been accepted as a significant language skill used most in communication (Anderson & Lynch, 1988; Anderson-Mejias, 1986).

Nowadays, listening is considered as an important process in terms of its four advantages: cognition, efficacy, utility and affect, so primary emphasis has been put on the development of listening comprehension (Gary, 1975). Listening to and understanding speech involves linguistic competence, recognition knowledge and background knowledge because listening is related to cognition. Because of that reason, the primary emphasis on listening comprehension is important as a more natural way to learn a language (Vandergrift, 1999). Thus, listening comprehension should be developed before speaking skills in foreign language classes, so the learners will grasp the exact meaning from the context and learn to produce correct sounds. This also shows the efficiency of this skill because listening provides a good language model for the learners.

With respect to utility, listening comprehension is important because people spend about 40 / 50 % of their communication time for listening. In terms of affect, listening comprehension is important because if pressure for early oral production is eliminated, the learners lower their inhibitions, feel safe and focus on their listening comprehension skills (Vandergrift, 1999).

2.2.4 Factors That Affect Listening Comprehension

Most learners complain about the difficulties of comprehending the spoken text, so many researchers have shown that there are some factors which may cause difficulties in listening comprehension (Goh, 2000).

spoken language, the learners‘ purpose in listening and the context. Similarly, according to Brown & Yule (1983), there are four factors that affect the difficulty of spoken language. These factors are the speaker (different speakers with different voices and accents, speech rate, the level of background noise), the listener (the purpose of listener, the level of response, the interest in the subject), the content (vocabulary, grammar, information structure, familiarity of topic, background knowledge, complex topic, unpredictable context), and supporting materials (visual aids to support the text – pictures, diagrams, etc.). Yagang (1994) also regards the message, the speaker, the listener and physical setting as important factors which cause difficulty in comprehension process.

According to Flowerdew & Miller (1996), the difficulties in listening to academic lectures were influenced by speech rate of the speaker, new terminology and concepts, concentration and problems related to physical setting. Similarly, Rubin (1994) claim that there are five factors which influence the comprehension process: text characteristics, interlocutor characteristics, task characteristics, listener characteristics, and process characteristics. For Hasan (2000), tasks and activities, the message, the speaker and the listener are significant factors in listening comprehension problems. In addition to them, some similar factors have been researched including speech rate (Blau, 1990; Conrad, 1989; Griffiths, 1992; Zhao, 1997), lexicon (Kelly, 1991), phonological characteristics (Henrichsen, 1984) and background knowledge (Markham & Latham, 1987; Long, 1990; Chiang & Dunkel, 1992). Brown (1995) agrees with these studies and adds that listening difficulty is the result of the levels of cognitive demands from the content of the text. For Lynch (1997), listening difficulties arise from the learners‘ different social and cultural backgrounds.

It has to be kept in mind that each student has different language ability and background, so they may have some difficulty while listening to a spoken message because of the factors mentioned above. However, while dealing with comprehending spoken messages, all learners may try to integrate what they hear with their existing background and world knowledge. Hence, listening comprehension difficulties may be

overcome by giving the learners a chance to use their prior knowledge or knowledge of the world.

2.2.5 Different Components of Listening Comprehension

Listening comprehension is viewed theoretically as an active process in which learners focus on the selected parts of aural input, construct the meaning from passages and relate what they hear to the existing knowledge by using the mental processes (O‘Malley & Chamot & Kupper, 1989).

Listening comprehension has several components which depend on each other. The first is the individual‘s knowledge of the linguistic code to distinguish all the sounds, intonation patterns, voice qualities and perceive the message. The second is various types of cognitive skills to perceive the message and decode it. The third is the knowledge of the world. Successful listening comprehension involves the integration of all these components (Omaggio, 1986; O‘Malley et al, 1989).

The individual‘s knowledge of the linguistic code which includes discrimination of all the sounds, intonation patterns, voice qualities and perception of the message deals with phonology, morphology, lexicon, syntax and semantics. This component has occupied a crucial position in human language acquisition over centuries.

After acquiring the ability to distinguish sounds, intonation, patterns and voice qualities common to the language, the learners become ready to listen to the sentences for meaning. So, listening can be defined as an activity of concentrating on what speakers say and trying to understand what they mean (Underwood, 1989).

comprehension belongs not only to the speaker but also to the listener. In order to comprehend the spoken message, the listener perceives the raw material of words, the arrangement of words, and the rising/falling intonation to create significance from this material (Rivers, 1981). In other words, by making use of the linguistic information that is extracted from the sound signal, and situational context of the utterance, the listener builds a relationship between what is heard and what is said. That is, the comprehended message depends on what the listener perceives as an intention of the speaker. Chung (1994), Dunkel (1986), Rivers (1981), and Ur (1984) have claimed that the sent message consists of oral and paralinguistic information provided by speakers and visual information provided by the context in which the message is heard. Oral information includes what the speaker conveys to the listener in words and extra information or subtle shades of meaning which can be conveyed by intonation, and non-verbal vocalisation, such as sighs, whistles, grunts, laughs, etc. In a conversation, the intended meaning can be conveyed differently according to the additional modes that encode information. For instance, a speaker is saying ―You are ill‖ may convey different kinds of understanding involved according to the situational context. The speaker can simply state the fact that you seem ill, or express surprise because he/she did not expect you to be ill or ask a question by using intonation. We can conclude that it is not enough for the listener to understand the verbal message itself but to understand it in the context in which it occurs.

Paralinguistic cues such as facial expressions and body language also help the listeners to understand the conveyed message easily (Rivers, 1981). Paralinguistic cues enable listeners to use additional information to comprehend the intention of the speaker.

The visual context in which the message is being delivered may help listeners comprehend the message easily. How the conveyed message is comprehended relies both on the information from the conversational environment and the speakers‘ background knowledge. If a listener tries to comprehend the delivered message using an appropriate frame of reference and some contextual cues, he/she may interpret it easily (Bransford, 1979; Rivers, 1981).

2.2.6 Stages of Listening Comprehension Process

Promising results can be attained from the foreign language learners if the listening process is divided into three stages: pre-listening, while-listening and post-listening.

2.2.6.1 Pre-listening

The pre-listening phase is a kind of preparatory work which: ―(...) ought to make the context explicit, clarify purposes and establish roles, procedures and goals for listening‖ (Rost 1990:232). In real life situations a listener almost always knows in advance something which is going to be said, who is speaking or what the subject is going to be about. The pre-listening stage helps learners to find out the aim of listening and provides the necessary background information.

The learners come to the listening process with different backgrounds (Young, 1997). Learners‘ comprehension is further influenced by several factors such as beliefs, attitudes, etc. Thus, learners need to be ready for what they are going to hear for better comprehension. By using pre-listening activities, not only the purpose of listening set, but also the learners‘ motivation and linguistic knowledge can be triggered. Jones and Kimborough (1987:2) suggest introducing some preliminary discussion in which students can talk together about their expectations and make predictions about what they are going to hear.

Pre-listening work can consist of a whole range of activities, including the teacher giving background information, the students reading something relevant, the students looking at pictures, discussion and answer session, written exercises, following

instructions for the while-listening activity, and consideration of how the while-listening activity will be done (Underwood 1989:31).

These types of exercise help to focus the learners‘ minds on the topic, specifying and selecting the items that the students expect to hear, and activating prior knowledge and language structures which have already been met. If the learner knows in advance that they are going to make a certain kind of response, they are immediately provided with a purpose in listening and they know what sort of information to expect and how to react to it. Such activities provide an opportunity to gain some, even if limited, knowledge which will help them to follow the listening text. According to Yagang (1994) this knowledge not only provides encouragement but also develops students‘ confidence in their ability to deal with listening problems. He suggests a variety of tasks for the pre-listening stage, such as: starting a discussion about the topic; where the students infer from the title what the topic of a conversation may be and the teacher encourages them to exchange ideas and opinions about the topic, brainstorming; where the teacher asks the students to predict the words and expressions which are likely to appear in the listening passage, games; e.g. miming the words or expressions, and guiding questions, asked or written by the teacher.

Mary Underwood in her book on teaching listening presents a number of activities which can be conducted in the classroom before the actual listening (1989:35-44). One of the most popular and frequently used exercise is looking at a set of pictures and naming the items which are likely to occur in the listening text. This can be done by a question and answer session or by general group discussion. Underwood does not advise giving the learners long lists of unknown words or long explanations, as this will not help to listen naturally, and such pre-listening ‗looking and talking about‘ is an effective way of reminding students of the vocabulary which may have been forgotten. In order to practise newly learnt words Underwood suggests providing students with the list of items and thoughts, however, the list should not comprise only the words which may cause difficulties, but it should have some purpose in the total (listening) activity. For example, it can be a list on which certain words or phrases will be ticked, circled or

underlined during the while-listening stage. This kind of activity removes the stress of suddenly hearing something forgotten and thus being distracted from the next part of the listening text. Presenting the list in the order in which the words, phrases and statements occur in the text makes while-listening exercises easier, so if the students find the task too easy, the teacher can increase the level of difficulty by putting the list in random order.

Other, popular pre-listening activities are: reading a text or reading through questions. As far as the former activity is concerned it is not recommended to give the students a written transcript of a listening text (Underwood 1989: 35-44), instead the students can read a short text and then check certain information and facts while listening. The latter exercise is based upon the principle that many listening activities require students to answer some questions after they hear a text, so it is quite helpful for the learners to see the questions before they begin listening, as they know what sort of information they have to look for. In order to revise the language already known it is recommended to propose an activity in which learners label a picture or pictures using the vocabulary already taught. Even if the students are able to complete all the labels before they hear the text, it is still a good activity as they listen and check whether they were right. What is more, this activity is suitable for pair or group work as it can generate a lot of discussion. Another good pair/group work exercise is completing a chart before listening. This activity can make students feel more personally involved if they are to fill in a chart with their own views or preferences and they can compare their opinions and judgements with others. For more advanced learners Underwood (1989) suggests predicting and speculating before listening. Although predicting what precisely the speaker will say next is a while-listening activity, predicting and speculating in a more general way can be a pre-listening activity. The students can be told something about the speaker/speakers and the topic and then try to indicate predict what they are likely to hear in the listening text.

Main pre-listening objectives are motivating and arousing interest in the learner, triggering off learners‘ prior knowledge, building linguistic knowledge, establishing a

purpose for the listener and providing a suitable situation for the listening task.

2.2.6.2 While-listening

While-listening activities can be defined as all tasks that students are asked to do during the time of listening to the text. At this stage, listeners confirm and edit their predictions about the received input. During this stage, the listeners are expected to make connections with their background knowledge, find out the speaker‘s intended message, concentrate on message rather than unknown words, verify former predictions, and make inferences and interpretations. The aim of this stage is to help learners to listen for meaning, that is to elicit a message from spoken language. Rixon (1986:70-1) points out that, at the while-listening stage students should not worry about interpreting long questions or giving full answers, but they should concentrate on comprehension, whether they have understood important information from the passage. That means that students can focus their attention on listening itself, rather than on worrying about reading, writing, grammar or spelling. The aim of the while-listening stage for students is to understand the message of the text not catching each word; they need to understand enough to collect the necessary information. While-listening exercises should be interesting and challenging, they should guide the students to handle the information and messages from the listening text.

According to Buck (1992), language learners resort to cognitive strategies to help them process, store and recall new information such as deducing the meaning of complicated words or ideas from the context. Cognitive strategies involve doing things with incoming information, often with the help of existing knowledge from long-term memory.

During the while-listening phase students usually respond somehow to a listening text. They indicate appropriate pictures or answers to multiple-choice questions,

complete a cloze test, fill in the blanks of incomplete sentences or of a grid, or write short answers to the questions etc. Yagang (1994) gives a number of suggestions such as; comparing the listening passage with the pre-listening phase, obeying instructions; where students are given certain instructions and show their understanding by a physical response (they draw, write, tick, underline etc.), filling in gaps; while listening to a dialogue students hear only the utterances of one of the speakers and are asked to write down those of the others, detecting differences or mistakes from a listening passage; students respond only when they encounter something different or contrary to what they already knew about the topic or the speakers, ticking off items; where students listen a list of words and categorize them as they hear, information transfer; where students have to fill grids, forms, lists, maps, plans etc., sequencing; where students are asked to give the right order of a series of pictures, information search; that is listening for specific items, e.g. answer a particular question from the pre-listening stage, filling in blanks of a transcript of a passage with the words missing, matching the items which have the same or opposite meaning as those the students hear, or matching the pictures with the descriptions heard.

One of the most popular while-listening activities is marking/checking the items in pictures. A picture is presented to students during the pre-listening stage and during the while-listening stage they are asked to mark/check/tick/circle etc. certain things in the picture. This is a very simple exercise, but it should not be rejected by teachers due to its apparent simplicity. The aim here is not to test students‘ abilities to make correct sentences based on the listening passage but to assist concentration on the text. This type of activity is good for helping learners to focus their minds on listening itself as they do not have to write down words. Among other activities are identifying people or things, marking errors or choices, checking details, marking items and pictures indicated by the speakers; e.g. students listen to a description or a short dialogue and decide (from the given selection) which picture is the right one. Another possibility is to give students different sets of pictures, while listening they decide which set ‗goes with‘ the story. Another possibility is to arrange pictures in the correct order according to the listening text. Underwood (1989) states that it is important to have a series of pictures which cannot be easily put in order without listening, though the students may try to solve this

exercise during the pre-listening phase. Younger learners and students at lower levels may be involved in an exercise where, presented only with a basic draft of a picture, they must draw or colour certain things following the instructions. A very popular exercise is the one during which students follow a route on a plan or map. During the pre-listening stage the students may try to mark the quickest way from A to B and then while listening check whether they were right. This type of activity could also be a good vocabulary practice if the teacher introduces the lexis of a hotel, hospital, airport, school etc. There is also a wide range of information gap activities which may require grid, form or chart completion. Usually these are used for listening about train/plane/bus timetables or likes/dislikes and hobbies. Making a list (a shopping list, or a list of places to visit) is another useful while-listening exercise. However, this one requires students to listen and write at the same time and may pose difficulties to the learners with limited listening experience in a foreign language or to those with spelling problems. It may happen that students are not familiar with the words, so they would not know how to write them. Underwood (1989) recommends in such a case introducing the words and phrases at the pre-listening stage. Two while-listening activities are True/False and multiple-choice questions, but they seem rather to test than teach. Usually students panic because of large number of such questions and they are afraid they will not be able to answer all of them during the listening time; though they always have 50% with true/false, and 25% - provided there are four answers – with multiple-choice questions, chance to tick the right solution. Text completion, on the other hand, is a very well accepted task among students, especially if it takes the form of songs or poems completion. Underwood (1989) suggests first completing of the text during pre-listening phase. The teacher should bear in mind that no matter which activities they choose, they must provide the students with immediate feedback either by giving the right answers by themselves or by asking the students to check and talk the solutions over in pairs or in groups.

2.2.6.3. Post-listening

listening to the text. Post-listening activities are very important as the listeners illuminate what they understand. Well-planned activities help learners to make connections between what they have heard and what they already know (Rixon, 1986). Some of these activities may be the extensions of those carried out at pre- and while-listening work but some may not be related to them at all and present a totally independent part of the listening session. Post-listening activities allow the learners to ‗reflect‘ on the language from the passage; on sound, grammar and vocabulary as they last longer than while-listening activities so the students have time to think, discuss or write (Underwood, 1989). There are a few tasks which teachers may do in the classroom after listening to a text (Pierce 1989) such as; discussing students‘ reactions to the content of the listening selection, asking students thought-provoking questions to encourage discussion, setting students to work in pairs to create dialogues based on the listening text, assigning reading and writing activities based on what students listened to.

Post-listening exercises should be interesting and motivating. Before a teacher chooses a certain activity he/she must consider how much language work they wish to do with the particular listening passage. How much time they will need to do a particular post-listening task; whether the post-listening stage will include speaking, reading or writing and whether they want students to work individually, in pairs or in groups (Underwood 1989). Yagang (1994) proposes the following activities for post-listening stage: Answering multiple-choice or true/false questions to show comprehension of messages, problem solving activities during which students hear all the information relevant to a particular problem and then try to solve it by themselves, summarising, students are given several possible summary sentences and are asked to say which of them fit a recording, jigsaw listening, writing letters, telegrams, postcards, messages etc. as a follow-up to listening activities, speaking in a form of debates, interviews, discussions, role-plays, simulations, dramatisation etc. as a follow-up exercise.

Main after-listening objectives are helping the learners to analyze, evaluate, synthesize, and organize critically what has been heard, enabling connections between their prior knowledge and new experience, and enhancing their understanding through