The Built & Human Environment Review, Volume 4, Special Issue 1, 2011

13

Cultural Values of Architectural Students

Tantekin, G. C.1, Laptalı, E. O.2 and Korkmaz A.2

gtantekin@yahoo.com, eoral@cu.edu.tr and k_korkmaz76@yahoo.com,

1

Çukurova University, Architectural Department, Adana, TURKEY 2

Çukurova University, Civil Engineering Department, Adana, TURKEY

Abstract

Culture is a dynamic reference point of a society which; constantly interacts with the environment, is shared and learned by the society members, affects the behavior of the society members and is passed on from generation to generation. Meanwhile, society members are affected by many cultural formations at the same time. Profession of an individual, for example, is one of these formations and professional cultural values are taught –consciously or unconsciously- together with technical aspects of the profession during vocational education. Thus, the hypothesis of the current study is that an architect’s professional culture starts to be shaped during the undergraduate study. A questionnaire survey based on Hofstede’s (2008) cultural dimensions has been undertaken with second and third year architectural students to test this hypothesis. Findings mainly show the effect of project based lectures on cultural formation of students.

Keywords: Culture, cultural differences, Hofstede, architectural education, construction sector

Introduction

Engineering and architectural sub-cultures have a significant role for the formation of the professional culture affecting the construction sector and; basic beliefs, values and judgments; are acquired during different stages of undergraduate education (Korkmaz,2009). It is thus expected that cultural values and approaches of students would be different during different years of undergraduate education due to the nature of the education process. The purpose of the current research has then been to identify differences and similarities in cultural values of civil engineering and architectural students during different years of their studies. This paper focuses on the research findings related with the architectural students.

“Culture” Concept And Hofstede’s Cultural Values

“Culture” concept which has been examined by different disciplines has over 300 definitions (Hofstede, 2001). It has been stated by sociologists and anthropologists that it is easier to explain “culture” rather than to define it.

Most researchers who study in the field of “culture”, agree on the common features of culture that; culture is; learned, shared, symbolic, rigid, restrictive, can be adjusted, and is passed from generation to generation (Hodgetts ve Luthans, 2003).

The Built & Human Environment Review, Volume 4, Special Issue 1, 2011

14

Many researchers (Hofstede, 1980a, 1991a, 2001; Schein, 1985; Trompenaars, 1993; Hancock, 2000; Sargut, 2001; Bowditch & Buono, 2001; Basım, 2000) analyzed culture and cultural differences by dividing the cultural environment into layers. According to them, while national culture affected the industry culture, industry culture affected the organizational culture and organizational culture affected group (family or community) and individual culture; and each layer has interaction with each other.

Hofstede (2001) defines culture as “the collective programming of the mind that distinguishes the members of one group or category of people from another.” Collective mind distinguishes one group from another and establishes cultural differences (Eren, 2006). Research related with understanding cultural differences have mainly focused on the comparison between countries and concentrated on the ways to adopt different national cultures to each other in order to satisfy business needs (www.igeme.org.tr/tur/haber/iskultur /uluslararasikulturweb.pdf, 2007).Among all of these studies, Hofstede’s (1980b, 2001) findings have most widely been used by other researchers. Hofstede indentified five dimensions (indexes) which explain how and why people/groups are affected by cultural structures (1991b, 2001). These are: Power Distance (PDI), Uncertainty Avoidance (UAI), Individualism (IDV), Masculinity (MAS),and Long Term-Short Term Orientation (LTO) and formed “Values Survey Module” (VSM). Then Minkov et al. (2008) added two new dimensions which are, Indulgence Versus Restraint (IVR) and Monumentalism (MON) and formed VSM08 together with the other 5 dimensions. These seven cultural dimensions are described below briefly.

Power Distance Index (PDI)

Most prominent feature of high “Power Distance” societies is the obedience of individuals to the orders of their superiors blindly. Children are taught obedience and individuals with power are always privileged.

Individualism Index (IDV)

The cultural differences are measured at opposite poles. At one pole there is “Individualism” (high IDV), at the other pole there is “Collectivism” (low IDV). “Collectivism” is dominant in a community which individuals are closely connected to each other with collective trends. The individual values of high IDV cultures is more “I centrist”. Relations in a society where “Individualism” is high are imposed on mutual interests and individual rationality together with cost/benefit ratio is considered in relations. Individual differences are considered to be normal.

Masculinity Index (MAS)

This cultural dimension has two poles; “Masculinity” with high MAS value and femininity with low MAS value. If success, money and assertiveness are important values of a society then there is a masculine culture in that society. If values like; worry for the environment, emphasis on quality of life, moral values are leading the society then femininity is dominant in that society.

Uncertainty Avoidance Index (UAI)

In societies with high “Uncertainty Avoidance”; uncertainty is approached as a risk that has to be reduced. Emotions must be controlled and people should not be trusted. Skepticism is dominant in such societies. There is

The Built & Human Environment Review, Volume 4, Special Issue 1, 2011

15 only one right way and rules are strict. However, in societies with low “Uncertainty Avoidance” rules are flexible, emotions are not hidden, laziness is not n undesirable behavior and most people are perceived as trust worthy.

Long Term-Short Term Orientation Index (LTO)

“Long Term Oriented” (high LTO) societies are related to future values. The tendency is towards postponing the fulfillment of needs to the future. The most important events in life are believed to be in the future. There is also little tendency towards solving problems with unknown structures. “Short Term Oriented” (low LTO) societies focus on the past and the present time, feel responsible to traditions and are unconditionally complied with social norms. Both sides are related with “Confucius” approach.

Indulgence Versus Restraint Index (IVR)

“Indulgence Orientation” (high IVR) means a society which especially is tolerant to individuals’ desires to enjoy themselves, spend money, consume as freely as possible in their leisure time. It is the opposite polar of the “Restraint Orientation” (low IVR) where people enjoy their lives less and lives under the pressure of a conservative society. (Hofstede, 2008).

Monumentalism Index (MON)

High MON value means a society where importance and value is given to individuals who behave like monuments, i.e. proud and firm. The opposite pole is Self-Effacement (low MON), where the society rewards humor and flexibility. Comments to this dimension are parallel to short term orientation. In fact country points for “Monumentalism”, is substantially related with “Short Term Orientation”; and “Monumentalism” values have negative correlation with “Long Term Orientation” values (Hofstede, 2008).

Previous Studies

Hofstede’s cultural dimensions have been applied by many researchers in different sectors/countries (Hofstede and Bond, 1988; Hoppe, 1990; Pheng and Yuquan, 2002; Akıner, 2004; Akıner,2005; Balaban, 2006). In this section, studies related with construction sector and education are summarized together with studies concerning Turkey.

While Hancock (2000) studied cultural dimensions of; architects, civil engineers and building surveyors, Rowlinson and Root (1996) examined architects and surveyors at private and public sector in Hong Kong. Pheng and Yuquan (2002), on the other hand, studied construction managers and employees who have at least university degrees and work on two continuing projects in Singapore and China, in order to derive results related

with national and industrial cultural values. Tukiainen et al. (2003) examined cultural and institutional differences about the management of international construction projects in Middle East and Europe (Akıner, 2004; Akıner, 2005).

Hofstede (2001) and Hoppe (1990) are the first two researchers who studied about cultural dimensions in Turkey. Hoppe used Hofstede’s survey related with four cultural dimensions (VSM82). Hoppe’s survey

The Built & Human Environment Review, Volume 4, Special Issue 1, 2011

16

also included questions related with organizational learning and covered more than 30 countries including Turkey.

Akıner (2004) and Balaban (2006) used VSM82 and VSM94 questionnaires in order to; determine the coordinates of Turkish construction sector on national and sub-cultural levels and understand the effect of culture on motivation of the employees.

Hofstede and Bond (1988) used “Long-term Short-term” (LTO) dimension to the students in 23 different countries to adopt “Uncertainty Avoidance” dimension to Asian culture. Hofstede (2008) ,then, examined cultural dimensions on different grade levels in different countries and investigated differences between countries.

VSM08 survey was first translated to Turkish by Korkmaz (2009) to determine both the cultural coordinates of Turkish Construction Sector and to explain the differences between the cultural dimensions of undergraduate architectural and civil engineering students. Comparisons were made based on Hofstede’s seven cultural dimensions.

Methodology

In this study, the VSM08 questionnaire survey which is based on Hofstede’s seven cultural dimensions, translated into Turkish by Korkmaz (2009), was applied to the second and third year architectural students in Çukurova University. The reason for selecting these two grades was due to the fundamental changes in the format of the lessons between these two years. Theoretical lessons are more intense during the second class level and homeworks are based on individual applications. During the third year, there are “City Planning”, “Conservation and Restoration” lessons in which group works are basis of the learning process and lecturers’ interference in term of giving ideas to the projects are less than the previous years.

The questionnaire survey provides a comparison of Hoftede’s seven dimensions and there are 4 questions about each dimension. 5 point Likert Scale is used to answer the questions. Statistical analysis has been undertaken by using “Microsoft Office Excel 2007 for Windows” and “SPSS 17.0 for Windows” software programs. The "Cronbach's Alpha Coefficient" was calculated under the "Internal Consistency Method" in order to measure the reliability of test measurement. Cronbach's Alpha value was found to be 0,447 for 28 questions. After removal of the question “How proud are you to be a citizen of your country?” which belongs to “Monumentalism” dimension, the Cronbach's Alpha value was found to be over 0,5 which is within the confidence intervals for a pilot study (Nunnally, 1967).

Research Findings and Discussion

The Built & Human Environment Review, Volume 4, Special Issue 1, 2011

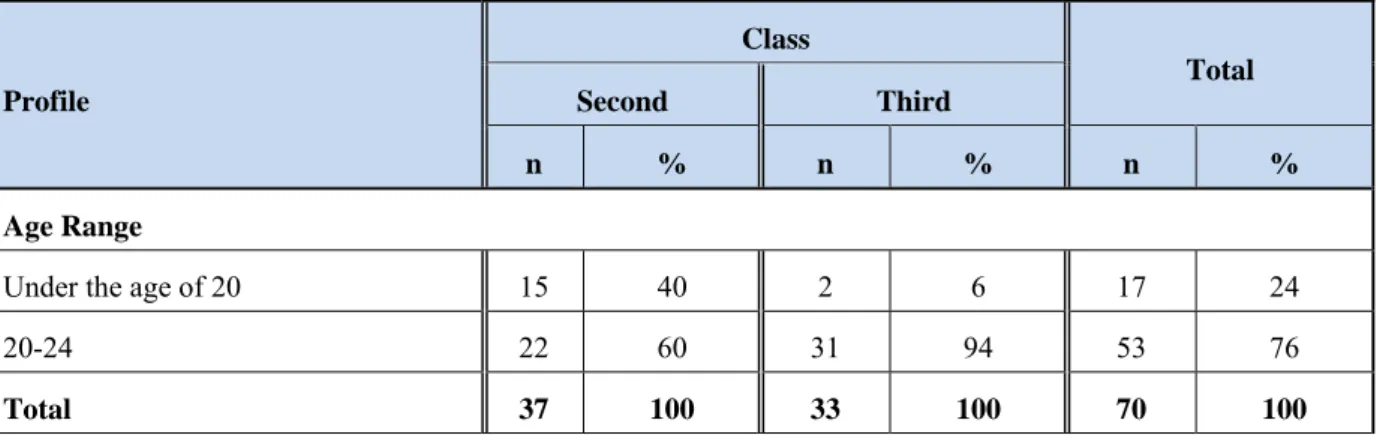

17 Profile and demographic characteristics of questionnaire survey participants, are given in Table 1, Table 2 and Table 3.

Table 1.Profile of survey participants.

Table 2. Age distribution of participants.

Profile Class Total Second Third n % n % n % Age Range

Under the age of 20 15 40 2 6 17 24

20-24 22 60 31 94 53 76

Total 37 100 33 100 70 100

Table 3. Gender characteristics of participants.

Profile Class Total Second Third n % n % n % Gender Boy 13 35 5 15 18 26 Girl 24 65 28 85 52 74 Total 37 100 33 100 70 100

Results in Table 1, Table 2 and Table 3 show that number of participants from second and third year students were nearly equal, 76% were between the ages of 20 to 24 and most of them (74%) were girls.

Class n %

Second year students 37 53

Third year students 33 47

The Built & Human Environment Review, Volume 4, Special Issue 1, 2011

18

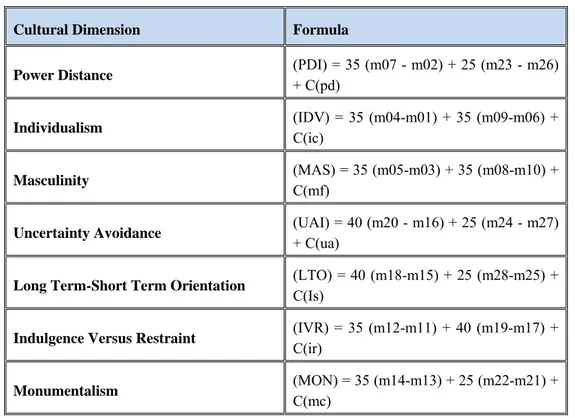

Seven Cultural Dimensions

Seven cultural dimensions of the two classes were calculated by following Hofstede's methodology (Hofstede et al., 2008). The formula for the calculation of these dimensions are given in Table 4 and the research findings are given in Table 5.

Table 4. Formula used for the calculation of the Hofstede’s seven dimensions.

Cultural Dimension Formula

Power Distance (PDI) = 35 (m07 - m02) + 25 (m23 - m26) + C(pd)

Individualism (IDV) = 35 (m04-m01) + 35 (m09-m06) +

C(ic)

Masculinity (MAS) = 35 (m05-m03) + 35 (m08-m10) +

C(mf)

Uncertainty Avoidance (UAI) = 40 (m20 - m16) + 25 (m24 - m27) + C(ua)

Long Term-Short Term Orientation (LTO) = 40 (m18-m15) + 25 (m28-m25) + C(Is)

Indulgence Versus Restraint (IVR) = 35 (m12-m11) + 40 (m19-m17) + C(ir)

Monumentalism (MON) = 35 (m14-m13) + 25 (m22-m21) +

C(mc)

m(i) : mean score (i) (The average value of the answers to the i th question)

c(x) : Coefficient value that is appointed by the researcher for dimension x. It can be any value between 0 and 100.

Table 5. Cultural dimension values of participants.

The Built & Human Environment Review, Volume 4, Special Issue 1, 2011

19

Class (PDI) (IDV) (MAS) (UAI) (LTO) (IVR) (MON)

Second Year 42 29 39 43 54 88 45

Third Year 42 4 25 66 32 68 46

Architecture Department General

42 17 33 54 43 78 46

Results presented in Table 5 are compared in the following paragraphs by considering factors that may affect cultural approaches of students.

Power Distance Dimension (PDI)

“Power Distance” dimension defines the relationship between teachers and students and freedom of students in asking for their rights within their department or in the university. Table 5 shows power distance dimension of both second and third year students to be equal. This result shows that students’ perception about their social status do not change between those two grades. This may be the result of application of standard procedures, existence of written rules throughout the university and approach of lecturers being equal to each grade student.

Individualism Dimension (IDV)

Third year students’ “Individualism” dimension value is lower than second year students’. Third year students work in groups in subjects like “City Planning” and “Conservation and Restoration” and submit their projects as a group. Increase in the amount of group activities result in the decrease in the ability of social mobility, i.e. ability to act on his/her own. It also requires compatibility. The projects are graded for each group, not for each student by the lecturers. This leads groups’ interests to have a higher priority than each student’s interests. This is thus reflected to the IDV cultural dimension.

Masculinity Dimension (MAS)

Third year students’ “Masculinity” cultural dimension value is lower than second year students’. Parallel to IDV value, group working have also great importance for “Masculinity” cultural dimension value. Group working which is more common during the third year results in the increase in social relations and requires both cooperation between students and adaptability to group decisions. Students’ anxiety level also increases as students are responsible for things that are done both by themselves and by group members.

The Built & Human Environment Review, Volume 4, Special Issue 1, 2011

20

“Uncertainty Avoidance” dimension of third year students is higher than second year students. This is an expected result when details of project work during these classes are examined. During the first two years of their education, students are not asked to worry about the structural system details as they do not have enough knowledge about structural analysis. Third year project, on the other hand, includes all architectural and structural system considerations. Additionally instructors’ interference to students during their project work change between second and third years. Instructors leave third year students more on their own during their project work, by only showing problematic areas of their project and leaving solutions to the group decision. This increases the anxiety and stress level of students and leads them to avoid risk and behave and design in more conventional ways.

Long Term Short Term Orientation Dimension (LTO)

LTO values show that second year students have more plans related with the future than third year students. Third year students study project based subjects like “City planning”, “Conservation and Restoration” and “Architectural Design”, which require more intense working tempo. This situation blocks their planning tendency for the future , as it requires focusing on the present rather than the future.

Indulgence Versus Restraint Dimension (IVR)

“Indulgence Versus Restraint” value of second year students is higher than third year students. This may be due to the fact that heavy work load of third year students results in very limited time left for social life.

Monumentalism Dimension (MON)

“Monumentalism” dimension of second and third year architectural students are very close to each other which shows that architectural education does not affect the approach of students in praising certain type of behaviors like pride, humor or flexibility.

Conclusions and Recommendations

In this study, the VSM08 survey which was developed to measure cultural dimensions of societies by Hofstede (2008), has been practiced to Çukurova University Architectural Department second and third year students and the effect of project based lessons on students' cultural dimensions has been investigated. Results provide a better understanding to the effect of architectural education process on shaping cultural values of architects.

The questionnaire survey was a pilot study, as Turkish translation of VSM08 was used for the time. This, unavoidably, resulted in some pitfalls. In order to get over these pitfalls, future research in Turkey should first focus on the translation of the questions which decrease the Cronbach Alpha value. The survey should be extended to more architectural students from every grade.

References

The Built & Human Environment Review, Volume 4, Special Issue 1, 2011

21 University.

Akiner I., (2005) Satılık Kültürler. Karakutu Publication, Istanbul, 975865875-1.

Balaban B. (2006) Türk İnşaat Sektöründe Çalışanların Motivasyonu Üzerinde Kültürün Etkisi, Thesis (MSc), Istanbul Technical University.

Basim, N. (2000) Belirsizlikten Kaçınma ve Güç Mesafesi Kültürel Boyutları Bağlamında Asker Yöneticiler Üzerine Görgül Bir Araştırma. Journal of Air Force Academy, 2, 33-53.

Bowditch, J.L. and Buono, A.F. (2001) A Primer on Organizational Behavior (5th Edition). John Wiley & Sons, New York..

Eren, K. (2006) Toplam Kalite Yönetimi ve Kültür. http://www.ikademi.com/toplam-kalite-yonetimi/99-toplam

kalite-yonetimi-ve-kultur.html, (27.03.2006).

Hancock, M. R., (2000) Cultural Differences Between Construction Professionals in Denmark and United Kingdom, SBI Report No: 324, Danish Building Research Institute, Hoersholm.

Hodgetts, R. M. and Luthans F. (2003) International Management: Culture, Strategy and Behavior (5th Edition). McGraw-Hill Book Company, Boston.

Hofstede, G. (1980a) Culture's Consequences: International Differences in Work Related Values. Sage Publications, London, 0803913060.

Hofstede, G. (1980b) Motivation, Leadership and Organization: Do American Theories Apply Abroad. _____ Organizational Dynamics, 9(1):42-62.

Hofstede, G. and Bond, M. H. (1988) The Confucius Connection: From Cultural Roots to Economic Growth. Organizational Dynamics, 16(4):4-21.

Hofstede, G. (1991a) Culture and Organizations. McGraw-Hill Book Company, New York.

Hofstede, G. (1991b) Cultures and Organizations: Software of the Mind. McGraw-Hill Book Company, London, U.K.

Hofstede, G. (2001) Culture's Consequences: Comparing Values, Behaviors, Institutions, and Organizations _____ Across Nations (2nd edition), Sage Publications, Thousand Oaks, California.

Hofstede, G. (2008) Announcing a New Version of the Values Survey Module: the VSM 08.

____ http://stuwww.uvt.nl/~csmeets/VSM08.html .

Hoppe, M. H. (1990) A Comparative Study of Country Elites: International Differences in Work-Related Values and Learning and Their İmplications for Management Training and Development. Unpublished doctoral dissertation, University of North Caroline at Chapel Hill.

Korkmaz, A. (2009) İnşaat Sektöründe Lisans Eğitimi ve Sonrasında Mesleki Kültürlerin Karşılaştırılması, Thesis (MSc), Adana, Cukurova University.

Minkov, M., Hofstede, G., Hofstede, G. J.,., Vinken, H., (2008) Values Survey Module VSM 08 Handbook. http://www.geerthofstede.nl , 08 January 2008.

The Built & Human Environment Review, Volume 4, Special Issue 1, 2011

22

Pheng L. S. and Yuquan S., (2002) An Exploratory Study of Hofstede's Cross-Cultural Dimensions in Construction Projects, Management Decision, 40(1):7-16, http://wwwemeraldinsight.com/0025- 1747.htm . Emerald.

Rowlinson, S. and Root, D. (1996) The Impact of Culture on Project Management. British Council Report, HMSO, London.

Sargut, A. S. (2001) Kültürler Arası Farklılaşma ve Yönetim, İmge Kitabevi, Ankara.

Schein, E. H. (1985) Organizational Culture and Leadership. A Dynamic View, San Francisco: Jossey- Bass.Inc, 0787903620.

Schein, E. H. (1985) Organizational Culture: Skill, Degense Mechanism or Addiction? In F. R. Brush & J. B. Overmier (Eds.), Affect, Conditioning, and Cognition (pp. 315-323). Hillsdale, NJ: Erlbaum. Trompenaars, F. (1993) Riding the Waves of Culture: Understanding Cultural Diversity in Business. Nicholas Brealey Publishing, London.

Tukiainen S., Ainamo A., J Nummelin O., Koivu T., and Tainio R., (2003) Effects of Cultural

Differences on the Outcomes of Global Projects: Some Methodological Considerations. CIB TG23

International Conference: Professionalism in Construction: Culture of High Performance, 26-27 October, Hong Kong. www.igeme.org.tr/tur/haber/iskultur/uluslararasikulturweb.pdf , 2007.