iv PISTACIA IN CWANA

Contents

Preface vi

Acknowledgements vii

I. Pistacia in West and Central Asia 1

Cultivated Syrian pistachio varieties 1

A. Hadj-Hassan 1

Ecogeographic characterization of Pistacia spp. in Lebanon 13 S.N. Talhou1, G.A. Nehme, R. Baalbaki, R. Zurayk and Y. Adham 13

Distribution, use and conservation of pistachio in Iran 16

A. Esmail-pour 16

Pistachio production and cultivated varieties grown in Turkey 27

B. E. Ak and I. A ar 27

Wild Pistacia species in Turkey 35

H. S. Atli, S. Arpaci, N. Ka ka, H. Ayanoglu 35

Collection, conservation and utilization of Pistacia genetic resources in Cyprus 40

C. Gregoriou 41

Natural occurrence, distribution and uses of Pistacia species in Pakistan 45

R. Anwar and M.A. Rabbani 45

Pistacia in Central Asia 49

Kayimov A.K., R.A. Sultanov and G.M. Chernova 49

II. Pistacia in North Africa 56

Pistacia genetic resources and pistachio nut production in Morocco 56

W. Loudyi 56

Genetic resources of Pistacia in Tunisia 62

A. Ghorbel, A.Ben Salem-Fnayou, A. Chatibi and M. Twey 62

Pistachio cultivation in Libya 72

H. El - Ghawawi 72

Pistacia species in Egypt 75

I. A. Hussein 75

III. Pistacia in Mediterranean Europe 77

Pistacia conservation, characterization and use at IRTA: current situation

and prospects in Spain 77

I. Batlle, M. A. Romero, M. Rovira and F.J. Vargas 77

Wild and cultivated Pistacia species in Greece 88

CONTENTS v

IV. Strengthening cooperation on Pistacia 93

The FAO-CIHEAM Interregional Cooperative Research Network on Nuts 93

I. Batlle and F.J. Vargas 93

ACSAD s activities on Pistachio 96

H. E. Ebrahim 96

The Mediterranean Group for Almond and Pistachio (GREMPA) Groupe de Recherche et d Etude M diterran en pour le Pistachier et L Amandier 99

B. E. Ak 99

V. A 1999 and beyond agenda for Pistacia 100

PISTACIA IN WEST AND CENTRAL ASIA 27

Pistachio production and cultivated varieties grown in Turkey

. . a . a

University of Harran, Faculty of Agriculture, Dept. of Horticulture, anl urfa, Turkey

Introduction

Turkey is one of the main pistachio nut producing countries in the world. Pistachio (Pistacia vera L.) is the only edible crop among the 11 species of the genus Pistacia (Ak 1998a). It grows in limited areas due to its ecological requirements. Pistachio has been growing in wild or semi-wild forms for hundred of years in areas of Afghanistan, Northwest India, Iran, Turkey, Syria and other Near East and North African countries. The taxonomy of pistachio is as follows (Bilgen 1973). Division Phanergamae Sub-division Angiospermae Class Dicotyledoneae Sub-class Choripetales Order Sapindales Family Anacardiaceae Genus Pistacia

Species Pistacia vera

Pistachio is a dioecious fruit tree; male and female flowers are in fact produced on different trees and pollination is by wind. For this reason male trees should be present in the orchards. These are planted generally at the ratio of one male to eight (or 11) female trees. Pistachio trees can be grown in steppe or semi-desert areas where winters are cold and summers are long, dry and hot with annual precipitation varying between 150 and 300 mm (Ak 1992, Ka ka 1990).

The non-bearing period length, the more or less alternate bearing habit, fruit quality, blank nut formation and blooming time are the main characters that are of interest in each cultivar. These traits should be considered when deciding the most suitable cultivar structure for each production area (Valls 1990).

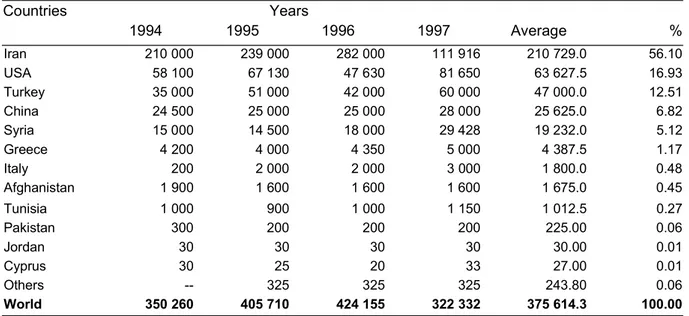

World pistachio production

The world production over four consecutive years is given in Table 1. The main world producers of pistachio nuts are Iran, USA, Turkey and Syria. Commercial exploitation of pistachio commenced in the 1930s in Iran, which still remains the largest producer (Chang 1990), providing 56.10% of the world s production. The second largest pistachio producer is USA, where Kerman is the most commonly grown cultivar. It covers over 90% of the total country production of pistachios. In both Iran and USA, pistachio plantations are irrigated whereas in Turkey there is no irrigation yet in place for this crop.

28 PISTACIA IN CWANA

Table 1. World pistachio production (tons)

Years Countries 1994 1995 1996 1997 Average % Iran 210 000 239 000 282 000 111 916 210 729.0 56.10 USA 58 100 67 130 47 630 81 650 63 627.5 16.93 Turkey 35 000 51 000 42 000 60 000 47 000.0 12.51 China 24 500 25 000 25 000 28 000 25 625.0 6.82 Syria 15 000 14 500 18 000 29 428 19 232.0 5.12 Greece 4 200 4 000 4 350 5 000 4 387.5 1.17 Italy 200 2 000 2 000 3 000 1 800.0 0.48 Afghanistan 1 900 1 600 1 600 1 600 1 675.0 0.45 Tunisia 1 000 900 1 000 1 150 1 012.5 0.27 Pakistan 300 200 200 200 225.00 0.06 Jordan 30 30 30 30 30.00 0.01 Cyprus 30 25 20 33 27.00 0.01 Others -- 325 325 325 243.80 0.06 World 350 260 405 710 424 155 322 332 375 614.3 100.00

Source: FAO Production Yearbook for 1994, 1995, 1996 and 1997

Pistachio production in Turkey

Pistachio has been cultivated for thousands of years in Turkey. It is speculated that Anatolia is one of the locations where pistachio might have originated.

Pistachio orchards are established in two ways: (1) through the top working of wild pistachio shrubs, trees and their hybrids which are used as rootstocks and which grow mainly in Anatolia. Under dry and non-irrigated conditions, a new pistachio orchard takes about 20-25 years to bear economic nut yields. This could be shortened to five to seven years by top working the wild trees. (2) By sowing the seeds directly using seedlings. As mentioned previously, pistachio production areas are characterized by dry and hot summer climates. Rainfall is very low and there is no irrigation or rain during the summer period. Therefore seedlings require a very long period to reach the budding stage (eight to ten years) (Ka ka 1990).

Pistachio can grow in very marginal soils, such as those that are stony, calcareous and poor. Pistachio in fact can be grown in soils, which are unsuitable for other crops. Pistachio productions in Turkey from 1994 to 1997 are given in Table 1. Table 2 provides estimates on the number of trees and yield in Turkey from 1955 to1996. The numbers of trees were 6.5 million in 1955, but this value reached to 44 million in 1996 with 54% of bearing trees. That means that the production is expected to increase in the future when non-bearing trees will enter production. The total production of nuts was 7636 tons in 1955 and reached 60 000 tons in 1996. There is no stability of production across years because of alternate bearing of trees. Although the yield per tree is very low, the production as a whole is increasing each year. The reasons behind the low yields in Turkey are: (i) young trees start bearing fruit very late, (ii) yield is very low on young trees, (iii) the soils of pistachio orchards are very poor, (iv) annual precipitation is very low and irrigation facilities do not exist, (v) application of chemical fertilizer is very limited, (vi) pollination is inefficient, (vii) most of the varieties have strong alternate bearing (Ka ka 1990, Ak 1998b). Out of these constraints, the most limiting factors in pistachio yields are irrigation, pollination and alternate bearing. Research efforts to address these problems are on-going in Turkey and elsewhere.

Pistachio is intensively grown in anl urfa, Gaziantep and Ad yaman areas (Table 3). Most of the pistachio cultivation areas are situated to the southern part of Turkey.

PISTACIA IN WEST AND CENTRAL ASIA 29

Source: Agricultural Structure and Production (statistics), State Institute of Statistics, Turkey. Table 2. Pistachio production and number of trees in Turkey

Number of trees ( 1000) Production Yield

Years Total Bearing Non-bearing (Tons)

Index* yield (kg/tree) 1955 6 579 -- -- 7 636 100.00 1.16 1960 8 413 -- -- 11 900 156.00 1.41 1965 10 750 -- -- 8 170 107.00 0.76 1970 18 123 10 937 7 186 14 200 186.00 1.30 1975 24 400 14 000 10 400 31 000 406.00 2.21 1980 28 150 16 150 12 000 7 500 98.00 0.46 1981 28 900 17 400 11 500 25 000 327.00 1.44 1982 30 330 17 400 12 930 13 000 170.00 0.75 1983 30 230 17 400 12 830 25 000 327.00 1.44 1984 30 600 17 600 13 000 23 000 301.00 1.31 1985 31 495 18 100 13 395 35 000 458.00 1.93 1986 30 310 18 640 12 670 30 000 393.00 1.61 1987 32 692 18 977 13 715 30 000 393.00 1.58 1988 33 377 19 343 14 034 15 000 196.00 0.78 1989 37 007 20 067 16 940 40 000 524.00 0.50 1990 37 418 20 385 17 033 14 000 183.00 0.69 1991 36 673 21 080 15 793 64 000 838.00 3.04 1992 38 600 22 000 16 600 29 000 380.00 1.32 1993 40 831 22 948 17 883 50 000 655.00 2.18 1994 41 689 23 340 18 349 40 000 524.00 1.71 1995 42 760 23 850 18 910 36 000 471.00 1.51 1996 44 080 24 480 19 600 60 000 786.00 2.45

*Estimated on the basis of number of bearing tree only. Table 3. Main pistachio producer areas in Turkey

Number of trees1 Production2

Provinces

Total Bearing % Tons % Yield3

ANLIURFA 14 845 660 8 125 210 54.73 21 439.8 46.11 2.64 GAZ ANTEP 14 838 800 9 162 500 61.75 12 377.0 26.62 1.35 ADIYAMAN 5 490 300 3 305 000 60.20 3 817.5 8.21 1.16 K.MARA 1 415 000 799 000 56.47 2 467.5 5.31 3.09 S RT 1 140 100 558 700 49.00 1 311.5 2.82 2.35 D YARBAKIR 195 900 83 575 42.66 710.00 1.53 8.50 ANAKKALE 339 710 280 040 82.44 567.80 1.22 2.03 BATMAN 174 370 56 300 32.29 540.30 1.16 9.60 MARD N 598 996 156 150 26.07 522.50 1.12 3.35 MAN SA 796 511 409 211 51.38 462.30 0.99 1.13 ZM R 312 320 160 290 51.32 421.30 0.91 2.63 AYDIN 363 780 144 180 39.63 381.50 0.82 2.65 TOTAL 40 511 447 23 240 156 57.37 45 019 96.82 1.94 OTHERS 3 568 553 1 239 844 34.74 1 481 3.18 1.19 TURKEY 44 080 000 24 480 000 55.54 46 500 100.00 1.90

1Source: State Institute of Statistics (1996 data), Turkey. 2Average of 4 years (1993-1996).

3Estimated on the basis of number of bearing trees only.

As Table 3 indicates the main producer areas are those of Southern Anatolia. This region includes the GAP locality (Southern Anatolia Project), which is a major regional development effort. Thanks to the GAP project in the near future most of those listed areas

30 PISTACIA IN CWANA

will have irrigation facilities. The first three main producer cities meet about 81% of total pistachio production in Turkey (Table 3).

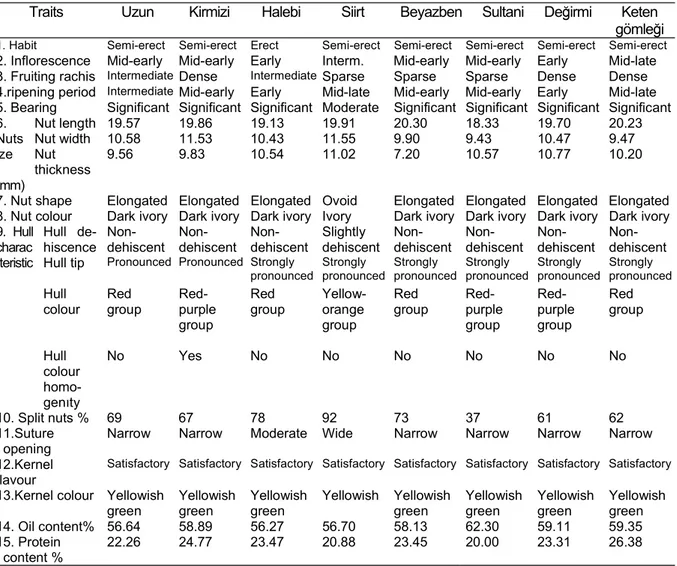

Pistachio varieties grown in Turkey

In Turkey, there are eight main domestic varieties, viz. Uzun, K rm z , Halebi, Siirt, Beyazben, Sultani, De irmi and Keten G mle i (Table 4); and five foreign varieties, viz. Ohadi, Bilgen, Vahidi, Sefidi and M mtaz (Table 5). For some varieties proper characterization using IPGRI s descriptors for pistachio (Pistacia vera L.) has been carried out (Barone et al. 1997).

Diversity of Turkish varieties

Following some values of most relevant descriptors for pistachio Turkish varieties are provided. Reference to IPGRI s descriptor list codes for Pistacia vera is given in parentheses whenever applicable.

1. Habit (6.1.2): Tree habits vary from erect to semi-erect, Halebi variety being the only erect type.

2. Flowering: Flowering period is very important because of the danger of late spring frost. Generally pistachio tree inflorescences appear late if we refer to other fruit species. Among the domestic varieties, Halebi and De irmi are early flowering; K rm z , Uzun, Beyazben and Sultani are mid-early and Siirt variety has intermediate.

3. Fruiting rachis: Changed from dense to sparse.

4. Ripening period: Early nut ripening is very important in pistachio as late fruit maturation could encounter rain and this would result in high production losses. In Turkey fruits are harvested by hand and this is a time-consuming operation. Fruits are spread on canvas to dry. Generally, early varieties mature at the beginning of September, having enough time to let fruits dry under the sun. However even early varieties are harvested late in some years. If late ripening occurs, the split nut rate will be low.

5. Bearing (6.3.10): All Turkish varieties except Siirt show strongly alternate bearing. Siirt has however a moderate alternate bearing.

6. Nut size: Nut size can change as a result of irrigation, fertilization and other cultivating practices. Nut length (mm)(6.4.6): Nut length ranges from 18.33 to 20.30.

Nut width (mm)(6.4.7): Nut width ranges from 9.43 to 11.55. Nut thickness (mm)(6.4.8): Nut thickness ranges from 7.20 to 11.02.

7. Nut shape (6.4.9): All Turkish varieties, except Siirt have elongated nut shapes Siirt has an ovoid nut shape.

8. Nutshell colour: Ivory in Siirt, dark ivory in all others. 9. Hull characteristics

Hull dehiscence (6.4.1): Only Siirt has slightly dehiscent halls. Other varieties are non-dehiscent.

Hull tip (6.4.3): This is strongly pronounced in all varieties except Uzun and K rm z . Hull colour (6.4.4): Domestic varieties are generally red. Only Siirt has yellowish hull colour.

Hull colour homogeneity (6.4.5): Homogeneous in all domestic varieties (except K rm z ). 10. Split nuts (%)(6.4.17): Splitting is a genetic trait typical of each variety (Ak 1998a) but it is

affected by the type of rootstock employed (Crane 1975), agronomic practices such as irrigation (Goldhamer et al. 1987, Ka ka and Ak 1996) and fertilization. Irrigation is the most important factor influencing the splitting, split nut rate can be increased in fact with greater irrigation. Another strategy to increase the number of split nuts is to use more Pistacia vera male trees in the orchard (Ak 1992, Riazi and Rahemi, 1995). However, splitting rate generally may change from year to year (Ak 1998c). Siirt is the best variety with regard to

PISTACIA IN WEST AND CENTRAL ASIA 31 splitting rate (G k e and Ak ay 1993).

11. Suture opening (6.4.20): Cultural practices such as irrigation, fertilization, pest and disease management also affect the suture opening. The better the kernel development the greater the suture opening.

12. Kernel flavour (6.4.30): Generally satisfactory in all varieties.

13. Kernel colour (6.4.31): This is an important factor for fruit quality. The desirable nut colour is green or dark green. Green colour depends on both genotype and environmental conditions. There are three methods to increase its incidence; the first is to grow pistachio trees at high altitudes where temperatures are lower during summers; the second is to harvest fruits before they reach full maturity (Karaca et al. 1988, Kunter et al. 1995); the third is to use s proper pollen source for instance, the fruits pollinated by P. terebinthus, P. atlantica, P. khinjuk and other wild pistachio species (except P. vera) will not be split and their kernels are dark green or greenish in colour (Ak 1992). Generally non-split fruits have green or greenish kernels. Domestic varieties generally have a yellowish-green kernel colour.

14. Oil content (%)(7.3.1.2): The average oil content of domestic varieties ranges from 56.27 to 62.30% (Karaca and Nizamo lu, 1995).

15. Protein content (%)(7.3.1.1): The average protein content of domestic varieties ranges from 20.00 to 26.38% (Karaca and Nizamo lu, 1995).

Table 4. Some traits of domestic Pistachio varieties grown in Turkey

Traits Uzun Kirmizi Halebi Siirt Beyazben Sultani De irmi Keten g mle i

1. Habit Semi-erect Semi-erect Erect Semi-erect Semi-erect Semi-erect Semi-erect Semi-erect

2. Inflorescence Mid-early Mid-early Early Interm. Mid-early Mid-early Early Mid-late

3. Fruiting rachis IntermediateDense IntermediateSparse Sparse Sparse Dense Dense

4.ripening period IntermediateMid-early Early Mid-late Mid-early Mid-early Early Mid-late 5. Bearing Significant Significant Significant Moderate Significant Significant Significant Significant

Nut length 19.57 19.86 19.13 19.91 20.30 18.33 19.70 20.23 Nut width 10.58 11.53 10.43 11.55 9.90 9.43 10.47 9.47 6. Nuts ize (mm) Nut thickness 9.56 9.83 10.54 11.02 7.20 10.57 10.77 10.20

7. Nut shape Elongated Elongated Elongated Ovoid Elongated Elongated Elongated Elongated

8. Nut colour Dark ivory Dark ivory Dark ivory Ivory Dark ivory Dark ivory Dark ivory Dark ivory Hull

de-hiscence Non-dehiscent Non-dehiscent Non-dehiscent dehiscent Slightly Non-dehiscent Non-dehiscent Non-dehiscent Non-dehiscent Hull tip Pronounced Pronounced Strongly

pronounced Strongly pronounced Strongly pronounced Strongly pronounced Strongly pronounced Strongly pronounced Hull

colour Red group Red-purple group

Red

group Yellow-orange group

Red

group Red-purple group Red-purple group Red group 9. Hull charac -teristic Hull colour homo-gen ty No Yes No No No No No No 10. Split nuts % 69 67 78 92 73 37 61 62 11.Suture

opening Narrow Narrow Moderate Wide Narrow Narrow Narrow Narrow

12.Kernel

flavour Satisfactory Satisfactory Satisfactory Satisfactory Satisfactory Satisfactory Satisfactory Satisfactory 13.Kernel colour Yellowish

green Yellowish green Yellowish green Yellowish Yellowish green Yellowish green Yellowish green Yellowish green

14. Oil content% 56.64 58.89 56.27 56.70 58.13 62.30 59.11 59.35

15. Protein

content % 22.26 24.77 23.47 20.88 23.45 20.00 23.31 26.38

32 PISTACIA IN CWANA

Table 5. Some traits of foreign pistachio varieties grown in Turkey Foreign varieties Trait

Ohadi Bilgen Vahidi Sefidi Mumtaz

1. Habit Spreading Spreading Spreading Semi-erect Spreading

2. Inflorescence Late Late Late Mid-late

3. Fruiting rachis Sparse Sparse Sparse Sparse Sparse

4. Ripening period Late Late Very late Late Very late

5. Bearing Moderate Moderate Moderate Moderate Moderate

Nut length 17.00 18.47 20.52 20.24 21.04 Nut width 12.03 13.72 15.12 12.36 13.65 6. N ut siz e (m m ) Nut Thickness 11.09 12.52 13.61 11.59 13.06

7. Nut shape Round Ovoid Ovoid Elongated Ovoid

8. Nut colour Ivory Ivory Ivory Dark ivory Dark ivory

Hull

Dehiscence Non-dehiscent Non-dehiscent Non-dehiscent Non-dehiscent Non-dehiscent

Hull tip Little

pronounced Little pronounced Little pronounced Strongly pronounced Strongly pronounced

Hull colour Orange-red

group Orange-red group Yellow-orange group Yellow-orange group Orange-red group

9. H ul l ch ar ac te ris tic Hull colour

homogeneity No Yes Yes No No

10. Split nuts % 47 42 32 71 58

11. Suture opening Moderate Narrow Narrow Narrow Narrow

12. Kernel flavour Satisfactory Satisfactory Satisfactory Satisfactory Satisfactory

13. Kernel colour Yellowish Yellowish Yellowish Yellowish Yellowish

14. Oil content % 58.97 51.75 55.67 56.77 55.40

15. Protein content % 23.22 24.63 21.77 24.43 23.15

Mid-late

Source: G k e and Ak ay (1993). This variety was introduced from Iraq by A.M. Bilgen.

Some traits of foreign varieties grown in Turkey

1. Habit (6.1.2): Sefidi is semi-erect and all others varieties are spreading types.

2. Flowering: International pistachio varieties are generally late flowering. Sefidi and Mumtaz are mid-late flowering; Ohadi, Bilgen and Vahidi varieties are late flowering. 3. Fruiting rachis: In all foreign varieties grown in Turkey, fruiting rachis is sparse. 4. Ripening period: Foreign varieties can be classified late to very late. Generally, late

varieties mature at the beginning of October in Turkey. If the maturation period is late, drying of the fruits will be a major problem in cultivation.

5. Bearing (6.43.10): Alternate bearing of fruits is moderate in all introduced varieties. 6. Nut size: Nut size of introduced varieties is generally small.

Nut length (mm)(6.4.6): Ranges from 17.00 to 21.04. Nut width (mm)(6.4.7): Ranges from 12.03 to 15.12. Nut thickness (mm)(6.4.8): Ranges from 11.09 to 13.61.

7. Nut shape (6.4.9): Bilgen, Vahidi and M mtaz are ovoid while Ohadi is roundish and Sefidi elongated.

8. Nutshell colour: ohadi, bilgen and vahidi ivory; sefidi and m mtaz dark ivory. 9. Hull characteristics

Hull dehiscence (6.4.1): All non-dehiscent.

Hull tip (6.4.3): In ohadi, bilgen and vahidi it is little pronounced whereas in sefidi and m mtaz is strongly pronounced.

Hull colour (6.4.4): Generally orange all varieties.

Hull colour homogeneity (6.4.5): Homogenous in bilgen and vahidi, not homogenous in ohadi, sefidi and m mtaz.

10. Split nuts (%)(6.9.17): Generally low. Sefidi having the highest splitting.

11. Suture opening (6.4.20): All varieties have narrow suture openings except ohadi in which this trait is moderate.

PISTACIA IN WEST AND CENTRAL ASIA 33 12. Kernel flavor (6.4.30): Generally satisfactory.

13. Kernel colour (6.4.31): Yellowish for all varieties.

14. Oil content (%)(6.3.1.2): The average oil content of foreign varieties ranges from 51.75 to 58.97% (karaca and Nizamo lu 1995, Ak and Ka ka, 1998).

15. Protein content (%)(6.3.1.1): The average protein content of domestic varieties ranges from 21.77 to 24.63% (Karaca and Nizamo lu 1995, Ak and Ka ka 1998).

Marketing

Pistachio nuts are generally marketed as salted and roasted as in-shell nuts. Roasting taces place in special ovens for 7 to 8 minutes at 110 C or 4 to 5 minutes at 150-160 C. During the roasting the nuts are continuously agitated. Roasted nuts are kept in plastic film lined sacks (Ka ka 1990).

In Turkey a certain amount of pistachio nuts is marketed as green kernels. The shells of nuts harvested a little earlier or grown at high elevations are split by hand crackers, separated from the kernels sieved and finally steam-sterilized before being sold in paper bags. The green kernels are more expensive and are used mostly in ice cream, pastry, halva (sweet dessert), baklava (sweet pastry), chocolate and other confectionery preparation (Ka ka, 1990).

Roasted in-shell pistachio nuts should be stored in a dry place to avoid absorption of moisture and the loss of flavour. Over the past ten years, Turkish salted and roasted pistachio nuts have been marketed in vacuum-sealed polyethylene bags of 250 g, 500 g and 1000 g (Ka ka 1990).

At the market, Turkish pistachio varieties are classified in two groups: (a) varieties with long fruits used for the table (Siirt, Ohadi, M mtaz etc) and (b) varieties with green kernels for industrial use (Uzun, K rm z , Halebi etc.) (Ayfer 1964).

Conservation

The germplasm of Turkish and international varieties is being maintained in Gaziantep in the field collection of the Pistachio Research Institute. The same varieties are also preserved in Ceylanpinar Experimental State Farm. In order to safeguard the genetic identity of each variety, and to best contribute to their preservation, global and regional field collections should be established to this regard with the aim of preserving all varieties and possible ecotypes. Tekin and Akk k (1995) carried out studies on pistachio in anliurfa, Gaziantep, Kahramanmara and Ad yaman Provinces. These studies have lead to the selection of 16 types, all having different characters. These types have been subsequently planted in both Gaziantep (Pistachio Research Institute) and Ceylanpinar State Farm.

Concluding remarks

In anliurfa, Gaziantep and other Turkish localities, pistachio trees will be irrigated and their yield will be further increased. Besides its positive effect on yield, irrigation also has a very beneficial effect on the increase of nut size and splitting incidence. Irrigation also reduces the percentage of blank nuts. Leaf size and number of current years shoots are also increased through irrigation (Goldhamer et al. 1987). As a result of this, the incidence of alternate bearing is expected to decrease in the future in Turkey.

Among the domestic varieties, Siirt is the most important for table use. It is therefore recommended that new orchards in the country be established using this variety.

References

AK, B. E., 1992. Effects of pollen of different Pistacia species on the nut set and quality of pistachio nuts. PhD Thesis, Univ. of ukurova, Faculty of Agriculture, Adana, Turkey. 211p. (in Turkish).

34 PISTACIA IN CWANA

Farm. Second International Symposium on Pistachio and Almond. August 24-29, 1997, California (Davis), USA, ACTA Horticulturae, 470: 294-299.

AK, B.E. 1998b. an introduction to the Pistachio Research and Application Centre of the University of Harran. Proceedings of the X GREMPA workshop, 14-17 October 1996, Meknes (Morocco). Cahiers Options Mediterraneannes, Vol. 33: 209-212.

AK, B.E. 1998c. Fruit set and some fruit traits of pistachio cultivars grown under rainfed conditions at Ceylanp nar State Farm. Proceedings of the X GREMPA workshop, 14-17 October 1996, Meknes, Morocco. Cahiers Options Mediterraneannes, Vol. 33: 217-223.

AK, B.E. and N. Ka ka. 1998. Effects of pollens of different Pistacia spp. on the protein and oil content in pistachio nut. Proceedings of the X GREMPA workshop, 14-17 October 1996, Meknes, Morocco. Cahiers Options Mediterraneannes, Vol. 33: 197-201.

Ayfer, M. 1964. Pistachio nut culture and its problems with special reference to Turkey. Univ. Ank. Fac. Agr. Yearbook, 189-217.

Bilgen, A.M., 1973. Antepf st . Tar m ve Hayvanc l k Bak. Yay. Ankara, 123 s.

Chang, K., 1990. Market prospects for edible nuts. Nut Production Industry in Europe, Near East and North Africa. Reur Technical Series 13, 47-86.

Crane. J.C., 1975. The role of seed abortion and parthenocarpy in the production of blank pistachio nuts as affected by rootstocks. J. Amer. Soc. Hort. Sci., 100(3): 267-270.

G k e, M.H. and M. Ak ay, 1993. Antepf st e it katalo u. T.C. Tar m ve K yi leri Bak. Mesleki Yay. Genel No: 361, Seri No: 20, 64 s.

Goldhamer, D.A., B.C. Phene, R. Beede, L. Sherlin, S. Mahan And D. Rose, 1987. Effects of sustained deficit irrigation on pistachio tree performance. California Pistachio Industry. Annual Report Crop Year 1986-87, pp. 61-66.

IPGRI. 1997. Descriptors for Pistachio (Pistacia vera L.). International Plant Genetic Resources Institute, Rome, Italy, 51p.

Karaca, R. and A. Nizamo lu, 1995. Quality characteristics of Turkish and Iranian pistachio cultivars grown in Gaziantep. First International Symposium on Pistachio Nut. ACTA Horticulturae, 419: 307-312.

Karaca, R., F. Akk k and A. Nizamo lu, 1988. e itli yeti tirme b lgelerinde antepf st klar n n farkl olum zamanlar nda i rengi ve baz kalite zelliklerinin ara t r lmas . Antepf st Ara t rmalar Projesi Yeni teklif ve sonu projeler. Antepf st Ar . Enst. Gaziantep, 96 s.

Ka ka, N. 1990. Pistachio research and development in the Near East, North Africa and Southern Europe. Nut Production Industry in Europe, Near East and North Africa. Reur Technical Series 13, 133-160.

Ka ka, N. and B.E. AK,1996. Effects of high density Planting on yield and quality of pistachio nuts. Proceedings of the IX. GREMPA Meeting-Pistachio. Bronte-Sciacca, Italy. May 20-21, 1993. pp. 48-51.

Kunter, B., Y. G l en and M. Ayfer, 1995. Determination of the most suitable harvest time for green colourand high kernel quality of pistachio nut (Pistacia vera L.). First International Symposium on Pistachio Nut. ACTA Horticulturae, 419: 393-397.

Riazi, G.H. and M. Rahemi, 1995. The effects of various pollen on growth and development of Pistacia vera L. Nuts. First International Symposium on Pistachio Nut. ACTA Horticulturae, 419: 67-72. Tekin, H. and F. Akk k, 1995. Selection of pistachio nut and their comparison to Turkish standard

varieties. First International Symposium on Pistachio Nut. ACTA Horticulturae, 419: 287-292. Valls, J.T., 1990. Tree nut production in South Europe, Near East and North Africa issues related to

production and improvement. Nut Production Industry in Europe, Near East and North Africa. Reur Technical Series 13, 21-46.