THE CHANGING DYNAMICS OF THE ARCHITECTURAL

PROFESSION IN TURKEY, 1960s - 1970s: THE RISE OF

PARTICIPATORY DESIGN AND THE EXPERIMENTAL CASE

OF İZMİT NEW SETTLEMENTS PROJECT

A THESIS SUBMITTED TO

THE GRADUATE SCHOOL OF ENGINEERING AND SCIENCE OF BILKENT UNIVERSITY

IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF SCIENCE IN ARCHITECTURE

By

Eda Bozkurt

July 2019

ii

THE CHANGING DYNAMICS OF THE ARCHITECTURAL PROFESSION IN TURKEY, 1960s - 1970s: THE RISE OF PARTICIPATORY DESIGN AND THE EXPERIMENTAL CASE OF İZMİT NEW SETTLEMENTS PROJECT

By Eda Bozkurt July 2019

We certify that we have read this thesis and that in our opinion it is fully adequate, in scope and in quality, as a thesis for the degree of Master of Science.

Asst. Prof. Dr. Giorgio Gasco (Advisor)

Prof. Dr. Havva Meltem Gürel

Assoc. Prof. Dr. Bülent Batuman

Approved for the Graduate School of Engineering and Science:

Ezhan Karaşan

iii

ABSTRACT

THE CHANGING DYNAMICS OF THE ARCHITECTURAL

PROFESSION IN TURKEY, 1960s - 1970s: THE RISE OF

PARTICIPATORY DESIGN AND THE EXPERIMENTAL CASE

OF İZMİT NEW SETTLEMENTS PROJECT

Eda Bozkurt M.S. in Architecture

Advisor: Asst. Prof. Dr. Giorgio Gasco July 2019, 238 Pages

The post-WWII period was dense of political, economic, and social transformations whose repercussions spread well beyond the Western scene. Although Turkey didn’t participate directly into the conflict, it was nevertheless invested by this set of changes that turned out to be crucial in directing the internal dynamics of the country. Moreover, the widespread capitalist development and the consequent accelerating industrialization, drove Turkey along a turbulent process, full of continuous and multi-faceted transformations, which include unpredictable national politics, emerging new economies and social structures, and in particular, rapid and uncontrolled urbanization. This climate of change and radical transformations eventually affected also the discourse and the practice of architecture. After the collapse of CIAM, and the orthodox ideology of modern architecture, the climate of austerity originated in the post war era determined an internal crisis in the architectural discipline, and a profound re-foundation of its objectives and duties. In particular, the recognition of the social inequality derived from the post-war urban renewal programs in Western nations, eventually threatened the very credibility of architecture. This renewed criticism aiming to question the social roles of architecture, starting from the beginning of the 1960’s entered decisively into the architectural debate in Turkey. The aim of the thesis is to evaluate and trace the changing dynamics of the architectural profession,

iv

regarding the concern of ‘social awareness’ as a central topic in the Turkish architectural agenda of the period. Following the trajectory of this discourse, the study attempts to answer the following questions: What were the underlying causes that led the query for the redefinition of the social content of architecture, and the reconsideration of the moral obligations of the architects? For which reasons architects were encouraged to make an introverted criticism? What affected architects to seek for a radical occupational change in the conventional architectural practice? Focusing both on the Turkish and the international architectural debate, in the period comprised between the 1960s and the 1970s, this study aims to emphasize the notion of ‘user participation’ as a new tradition of thought developed within the socialist, left-wing architectural criticism. By challenging the authoritative practice of architecture, this phenomenon has addressed more equitable and democratic priorities in the generation of the space, particularly in the practices of housing. The attempt of the thesis is to pursue the rise of the ‘participatory design’ as a new architectural term which represents the consciousness of social responsibility, and to find out how Turkish architects were influenced/if influenced by their counterparts through transnational exchange of views. Eventually the thesis focuses on the re-evaluation of the ‘İzmit New Settlements Project’, an archetypal experiment to illustrate the changing dynamics in the Turkish architectural agenda. The proposed case study will investigate the presence of possible analogies with the international architectural debate. The ultimate aim of the re-evaluation of the ‘İzmit New Settlements Project’, is to enlighten its highly comprehensive program enabling the ‘user participation’ on a large scale, and to stress how it can be considered as a favorable alternative to the housing production policies for the low-income groups in Turkey, by featuring the revised complemental the dialogue between the architects, the society, and the political authorities.

Keywords: Changing Dynamics of the Architectural Profession, Social Awareness in Architecture, Impaired Power Relations between Architect and User, Alternative Production of Space, Housing Question, Participatory Design, İzmit New Settlements Project.

v

ÖZ

TÜRKİYE’DE DEĞİŞEN MİMARLIK MESLEK DİNAMİKLERİ,

1960’LAR – 1970’LER: KATILIMCI TASARIMIN DOĞUŞU

VE DENEYSEL BİR ÖRNEK OLARAK İZMİT YENİ

YERLEŞKELER PROJESİ

Eda Bozkurt

Yüksek Lisans, Mimarlık Bölümü Tez Danışmanı: Ass. Prof. Giorgio Gasco

Temmuz 2019, 238 Sayfa

İkinci Dünya Savaşı sonrası dönem, politik, ekonomik ve sosyal değişimlerin yoğun olarak yaşandığı bir dönem olmuş, bu değişimlerin yansımaları Batı’nın çok ötesine yayılmıştır. Türkiye her ne kadar doğrudan savaşa katılmamış olsa da, yaşanan bu değişimlerin yansımaları, ülkenin iç dinamiklerine yön veren önemli etkenler olmuştur. Yayılan kapitalist gelişim, ve beraberlerinde getirdiği hızlı sanayileşme, Türkiye’yi öngörülemeyen ulusal politikaların deneyimlendiği, yeni bir ekonomik ve sosyal yapının oluştuğu, ve özellikle de hızlı ve kontrolsüz kentleşmenin yaşandığı, çok yönlü değişimlerle dolu çalkantılı bir sürece itmiştir. Bu değişim ortamı ve yaşanan radikal dönüşümler, nihayetinde, mimarlık söylemini ve pratiğini de etkilemiştir. Savaş sonrası yaşanan bunalımlı dönem, mimarlık disiplininde bir iç kriz yaratmış, CIAM’in ve kalıplaşmış modern mimarlık ideolojisinin çöküşünün ardından, disiplinin amaçlarının ve görevlerinin, derinlemesine bir biçimde, yeniden kurgulamasına neden olmuştur. Özellikle Batı ülkelerinde savaş sonrası uygulanan kentsel dönüşüm programlarının doğurduğu sosyal eşitsizliğin fark edilmesi, mimarlık mesleğine karşı duyulan güveni tehdit etmiş, ve mesleğe karşı yöneltilen eleştirileri arttırmıştır. 1960’lı yılların başından beri gün yüzüne çıkan, ve mimarlığın sosyal rolünü sorgulamayı amaçlayan bu yeni eleştiri, aynı dönemlerde, Türkiye’nin mimarlık camiasındaki tartışmalarına da kesin olarak dahil olmuştur. Tezin amacı, o

vi

dönemin Türk mimarlık gündeminde de ön plana çıkan bu ‘sosyal farkındalık’ tartışmasının izini sürmek, ve değişen mimarlık meslek dinamikleri üzerine bir değerlendirme yapmaktır. Bu yeni söylemin gelişim sürecini takip etmeyi hedefleyen bu çalışma; aşağıda belirtilen soruların da cevaplarını aramaya çalışmaktadır: Mimarlığın sosyal içeriğinin yeniden tanımlanmasının, ve mimarların manevi yükümlülüklerinin yeniden gözden geçirilmesinin altında yatan sebepler nelerdir? Hangi sebepler mimarları, içe dönük bir eleştiri yapmaları konusunda teşvik etmiştir? Mimarları geleneksel mimarlık pratiğinde köklü bir mesleki değişim yapma arayışına sürükleyen etkenler nelerdir? 1960’lı ve 1970’li yılların hem Türkiye hem de uluslararası mimarlık tartışmalarına değinilen bu çalışmada, sosyalist, sol yönelimli mimari eleştirilerle geliştirilen, mimarlıkta ‘kullanıcı katılımı’ kavramının ön plana çıkarılması amaçlanmıştır. Mimarlığın otoriter kimliğine meydan okuyan bu fenomen, özellikle konut uygulamalarında, mekânın oluşumuna dair daha adil ve demokratik süreç önerileri sunmuştur. Bu tez çalışması ‘kullanıcı katılımı’ kavramını, mimarlık disiplininin sosyal sorumluluk bilincini temsil eden, yeni bir mimari terim olarak ele almaktadır. Ayrıca, uluslararası etkileşimlerle gerçekleştirilen mimari fikir alışverişleri aracılığıyla, Türk mimarların farklı ülkelerdeki meslektaşlarından ne denli etkilendiklerini/eğer etkilendilerse saptamaktadır. Sonunda ise, tez, Türk mimarlık gündeminin değişen dinamiklerinin ve söyleminin ilk kez hayata geçirilmesinin deneysel bir uygulaması olarak öne çıkan ‘İzmit ‘Yeni Yerleşkeler Projesi’ni bu bağlamı içinde incelemektedir. Ayrıca, mimarlık disiplininde önemi artan sosyal farkındalık kavramı dahilinde, bu projenin, uluslararası mimarlık tartışmalarından ve pratiklerinden edindiği olası referansların varlığını araştırmaktadır. ‘İzmit Yeni Yerleşkeler Projesi’nin incelenmesiyle, ‘kullanıcı katılımı’ stratejisinin, Türkiye’de düşük gelirliler için konut üretiminde, sosyal kaygılar taşıyan, belediye destekli alternatif bir konut politikalası olarak kullanılabileceği vurgulanmakta, ve katılımcı mimari proje süresince sağlanacak olan demokratik ortam ile, mimarlar, siyasi yetkililer ve toplum arasındaki iletişim bağlarının güçlendirilebileceği savunulmaktadır.

Anahtar Kelimeler: Değişen Mimarlık Meslek Dinamikleri, Mimarlıkta Sosyal Farkındalık, Mimar ve Kullanıcı Arasındaki Bozulan Güç Dengesi, Alternatif Mekan Üretimi, Konut Sorunu, Katılımcı Süreç, İzmit Yeni Yerleşkeler Projesi.

vii

To my family, in eternal gratitude...

viii

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

I would like to begin expressing my sincere gratitude toward Giorgio Gasco, my thesis advisor, for his consistent prodding, coaxing, and critical comments that provided me guidance throughout the preparation of this thesis. I would especially like to thank for his encouragement and support in my professional endeavors.

My grateful thanks to Meltem Gürel, Bülent Batuman, Serpil Özaloğlu, Mark Paul Frederickson, and all my professors at Bilkent University, for guiding me with their strong minds and valuable critics.

I would like to candidly thank Suha Özkan, Aydan Erim, Önder Şenyapılı, İlhan Tekeli, Erol Köse, who kindly accepted my interview requests and generously shared their valuable times, experiences, suggestions and professional approaches with me.

Thank you to my cousin Yasemin Asarlık, and to all of my friends, especially Melis Özkan, Eylül Taşkın, Elif Deniz Haberal, Cansu Coşkun, Feyza Pehlivan, Helyaneh Aboutalebi, Meltem Selen Önal, Mehveş Demirer, Çağla Mirasyedioğlu, Zeynep Altınkaya and Baran Orhan for their warm hearts and continuous motivations.

My deepest gratitude to my family, Gülten and Koray Bozkurt, for their unwavering support and unconditional love. Their spirits have always given me strength and have inspired me to strive towards my goals. I am so grateful to have them. And my other half, Burak Can Koç, who has always been right next to me; his serene love, sincere care and infinite support have always sustained me.

ix

TABLE OF CONTENTS

ABSTRACT...iii ÖZ...v DEDICATION...vii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS...viii TABLE OF CONTENTS...ix LIST OF ABBREVIATIONS...xi LIST OF FIGURES...xii 1. INTRODUCTION...1 1.1 Problem Statement...11.2 Aim and Scope...3

1.3 Method and Sources...6

1.4 Structure...10

2. PARADIGM SHIFTS IN THE INTERNATIONAL ARCHITECTURAL DEBATE...14

2.1 A Shift towards a Revised Modernism...15

2.2 The Changing Dynamics between the Architect and the User...17

2.3 The Rise of Participation...19

2.4 Illustrating the Debates on Participation...21

3. THE SOCIAL, POLITICAL, ECONOMIC AND ARCHITECTURAL CONTEXT OF TURKEY, 1960s-1970s...32

3.1 Developments in the 1960s and 1970s...32

3.1.1 Political and Institutional Developments...32

3.1.2 Economic and Sectoral Developments...35

3.1.3 Transforming the Architectural Education System...38

3.2 The Problem of Rapid Urbanization...42

x

4. THE EMERGENCE OF SOCIAL AWARENESS IN TURKISH

ARCHITECTURAL DEBATE...53

4.1 Changing Dynamics in the Architectural Agenda...54

4.1.1 Developments Related to the Social Role of Architects...54

4.1.2 Discussions among the Chamber of Architects...56

4.1.3 The 1969 Architecture Seminar...61

4.2 The New Municipal Movement, 1973-1977...64

4.2.1 Radicalization of Squatters...65

4.2.2 Local Elections of 1973 and the New Municipal Movement...68

4.2.3 New Municipalities’ Pursuit of Breakthrough in Housing...69

5. RE-EVALUATING THE EXPERIMENTAL CASE OF İZMİT NEW SETTLEMENTS PROJECT...72

5.1 İzmit Municipality and the Mayoral Consultants...73

5.2 About the Project...77

5.3 The Design Process...78

5.3.1 The Planning Strategy and the Local Organizations...78

5.3.2 The Participation of the Users...83

5.3.2.1 Participatory Design Phase with the ‘Possible Users’...86

5.3.2.2 Participatory Design Phase with the ‘Actual Users’...89

5.4 The System of Construction...96

6. CONCLUSION...101

FIGURES...109

BIBLIOGRAPHY...153

APPENDICIES...167

A. Interview with Suha Özkan...167

B. Interview with the Villaggio Matteotti Residents...174

C. Interview with Aydan Erim...177

D. Interview with Önder Şenyapılı...189

E. Interview with İlhan Tekeli...208

xi

LIST OF ABBREVIATIONS

CDSs: Community Design Centers

CIAM: Congrès Internationaux d’Architecture Moderne COE: Council of Europe

DP: Democrat Party

EEC: European Economic Community FYDP: Five Year Development Plans

IAF: International Architecture Foundation İTÜ: Istanbul Technical University

JP: Justice Party Mémé: Maison Médicale

METU: Middle East Technical University

OECD: Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development RPP: Republican People’s Party

SAR: Stichting Architecten Research SPO: State Planning Organization

TOKİ: Housing Development Administration [Toplu Konut İdaresi]

TUBİTAK: Turkish Scientific Technical Research Institution [Türkiye Bilimsel ve Teknolojik Araştırma Kurumu]

xii

LIST OF FIGURES

Figure Page

Figure 1.1 A letter written by Giancarlo De Carlo to Behruz Çinici in 1968

109

Figure 2.1 Aerial view of Ralph Erskine’s Byker Wall redevelopment project

110

Figure 2.2 Site Plan of Ralph Erskine’s Byker Wall redevelopment project

110

Figure 2.3 Partial elevation of Byker Wall 111

Figure 2.4 Physical model of the design proposal for Manila Competition by Doruk Pamir & Ercüment Gümrük

111

Figure 2.5 Site Plan of the design proposal for Manila Competition by Doruk Pamir & Ercüment Gümrük

112

Figure 2.6 Diagrams of the design proposal for Manila Competition by Doruk Pamir & Ercüment Gümrük

112

Figure 2.7 Diagram of the Segal’s modular timber-frame construction system

113

Figure 2.8 Left: Segal, while giving instructions to self-builders; Right: Lewisham self-builders at work in a half-constructed Segal House

113

Figure 2.9 Built houses in Lewisham. Left: Interior; Right: Exterior 114

Figure 2.10 Site Model of Villaggio Matteotti 115

Figure 2.11 Views from Villaggio Matteotti. 115

Figure 2.12 Semi-closed ground floors for car parking areas in Villaggio Matteotti

116

Figure 2.13 Top: Giancarlo De Carlo in a meeting with future

residents; Bottom: Future residents reviewing the models and drawings of different housing types

116

Figure 2.14 Mémé’s architectural form of ‘disorder’ 117

Figure 2.15 Interior views from Mémé 117

Figure 2.16 The 1:20 site model through which the future inhabitants were allowed to make changes to evolve the Mémé

xiii

Figure 2.17 An axonometric view of a particular cluster at Mexicali which was generated through following determined patterns

119

Figure 2.18 Future users are participating to the construction process in Mexicali

119

Figure 3.1 The claim of “Turkey can not produce automobiles” was confuted by ‘Devrim’

120

Figure 3.2 The newspaper clippings that announce the

establishments of new private schools of architecture

121

Figure 3.3 Some posters prepared by METU students during ’68 protests

122

Figure 3.4 The cover page of Mimarlık journal, showing the anonymous apartments (on the top), and gecekondus (at the bottom)

123

Figure 3.5 Illustrations of the various banks for Lottery Houses in 1950s

124

Figure 3.6 General Plan of 1st Levent Housing District 125

Figure 3.7 1st Levent Housing District 125

Figure 3.8 General Plan of 4th Levent Housing District 126

Figure 3.9 4th Levent Housing District 126

Figure 3.10 Aksaray Block Apartments on Atatürk Boulevard 127

Figure 3.11 General Plan of Ataköy Development 128

Figure 3.12 The Ataköy Development 128

Figure 3.13 View of the Ataköy Development from the sea 128 Figure 3.14 Aerial view of the model, OR-AN Settlement 129 Figure 3.15 Elevation drawing of one block of OR-AN Settlement 129 Figure 3.16 Elevation of one block of OR-AN Settlement 129 Figure 3.17 Model photo of Çorum Binevler Housing Complex 130 Figure 3.18 A photo from the site, Çorum Binevler Housing Complex 130 Figure 3.19 Photos of houses in Çorum Binevler Housing Complex 130 Figure 3.20 Location of İzmit New Settlements Project 131 Figure 3.21 S.S. Edirne Cumhuriye District, Apartment Elevations 132 Figure 3.22 S.S. Edirne Cumhuriye District, Sample Apartment Plan 132

xiv

Figure 3.23 S.S. Edirne Cumhuriye District, View from the street 132 Figure 4.1 First two pages of the charter of ‘Socialist Architects

Club’

133

Figure 4.2 A cartoon illustrating the XII. General Assembly of the Chamber of Architects

134

Figure 4.3 While the head of the Chamber, Haluk Baysal, was giving his opening speech for the XII. General Assembly in 1966

134

Figure 4.4 The posters demonstrating the discussions of the XVII. General Assembly of the Chamber

135

Figure 4.5 An aerial view of gecekondu settlements in Ankara 136 Figure 4.6 Demolition of a gecekondu dwelling, military men

standing in the front

136

Figure 4.7 A newspaper clipping about the results of 1973 local elections

137

Figure 4.8 Ahmet İsvan, the Mayor of İstanbul, indicates the need for working in collaboration with the group of experts in their professions for the new municipal programs

138

Figure 5.1 A newspaper clipping about the proposal on the municipalities’ mass-housing initiatives

139

Figure 5.2 A newspaper clipping about the new municipalism for the Turkish cities

139

Figure 5.3 A newspaper clipping about the land expropriation in İzmit under the leadership of the municipality, for the housing project with 30,000 house-capacity

140

Figure 5.4 A cartoon demonstating the possible alineation of people from their houses

141

Figure 5.5 A cartoon demonstrating that there is no choice for the low-income people other than the imposed mass-housing

142

Figure 5.6 Alison and Peter Smithson’s ‘hierarchy of association’ diagram

142

Figure 5.7 Interview with future users in their own dwellings 143 Figure 5.8 Meeting with the future user groups in the planning studio 143

xv

Figure 5.9 Model of a multi-story residential units 144 Figure 5.10 Three-storey blocks with private entrances through

stairways from their own courtyards

144

Figure 5.11 A large-scale model of a typical housing block 145 Figure 5.12 A 1:1 scale model of a prefabricated floor slab with a grid

of 9 sub-frames underneath

145

Figure 5.13 A cartoon demonstrating an active particiption of the user in the architectural design process

146

Figure 5.14 The site plan (at the top) and the elevation (at the bottom) drawings of one of the selected housing types

147

Figure 5.15 The first-floor plans of one of the selected housing types 148 Figure 5.16 The elevation drawing of one of the other selected

housing types

149

Figure 5.17 The first-floor plans of one of the other selected housing types

149

Figure 5.18 Construction of the prefabricated construction elements 150 Figure 5.19 The connection of the prefabricated floor slab and the

column

150

Figure 5.20 A newspaper clipping about the construction of the İzmit New Settlements project

151

Figure 5.21 A newspaper clipping about the factory which was started to be built to produce the construction elements of the New Settlements project

152

Figure 5.22 A newspaper clipping about the first foundation which was laid for the first building of the New Settlements Project in 1977

1

CHAPTER 1

INTRODUCTION

1.1 Problem Statement

The period between 1960s and 1970s, was characterized by provocative tendencies aiming to stress the limits of modern architecture in its meaning, image and language. Architectural practice started to be deeply criticized as a result of an abstract ideology unable to address social and cultural needs of community (Jones, Petrescu & Till, 2005, p.xiv). Therefore, the lens was shifted from the canonical features of modern architecture, such as formal functionality and rationality, to a set of new concepts and ideas such as; continuity, flexibility, complexity, plurality, social liability; in general, there was a shift towards pragmatism. In turn, it brought discussions on the moral obligations of the architects, on the changing dialogue between architects and the users, and on the occupational shift aiming to connect architecture with the society. These progressive dynamics have become the cumulative underpinnings for the rise of social awareness in architectural theory and practice.

This critical period was full of intense upheavals, including community protests, critiques of the welfare state, the rise of consumer society, that were exposed by the civil rights movements and the urban renewal in the U.S and Europe (Risselada & Heuvel, 2005, p.12). These turbulences, which gave this period its historical distinction, have been the catalysts that intensified an interest in social responsibility in almost every intellectual and professional spheres. Architecture, being one of them, has confronted with magnified criticisms upon its moral accountabilities. By questioning the authoritative doctrines of architecture, more democratic alternatives have been sought. Architects have strived after a social change through mediating between their professional authorities and the society’s unfulfilled needs. In spite of dominant decisions of architects while generating solutions through design, more egalitarian ways of space production started to be considered. Among other strategies

2

to reach this goal, ‘user participation’ gained an historic relevance due to its ideological appeal and determination in stating a sort of equality between architects and users in the implementation of a design process. This strategy succeeded to radically question the hierarchical approaches of previous architectural practice, and to promote a dialogue of involvement and consensus, and hence eventually earned a global consideration.

Under this framework, the study in particular, investigates a set of similar dynamics originated in the same years in Turkey. The country was, at that time, under the hegemony of political, economic and social mobility. The disequilibrium of Turkish politics has marked the inconsistent economic policies, whose echoes were transmuted both into country’s social structure and its architectural agenda (Tekeli, 2005, p .15). Additionally, as a composite result of the mechanization of rural areas, and industrialization of urban areas, rural masses subsequently migrated to the urban centers to chase new job opportunities. Thereafter, the consequent rapid urban growth immediately provoked a massive demand of dwelling that determined the urgent need of proper housing policies (Sey, 2005, p.170). The housing question, besides concerned within the political domains, also had broad repercussions in the Turkish architectural circles. Also, with the influence of social awakening in the wider world and the consequent criticism towards authoritative ethos of architecture, the parallel debates started to find places in the Turkish architectural agenda. Younger architects of the 1960s’s generation with socialist tendencies, reoriented themselves as the social agents. They defended the opinion that, architects have to be aware of the social realities of the community, and they have to use their technical expertise for serving the society (Baytop, 1966, pp.8-12). These discussions have been the main agenda topics for the Chamber of Architects. This younger generation of Turkish architects who were aware of the crises in architecture, called for a reform in the organizational and ideological structure of the Turkish architectural agenda through a redirection towards society (TMMOB Mimarlar Odası, 1969, unpaginated). The fragmentations in the architectural debate, due to the confrontational views of the younger and the older generation of architects, became evident by mid-60s. After the architects with socialist tendencies took all the seats of the Executive Board of the Chamber of Architects in 1971, the organization expanded its borders with left-wing ideologies

3

through their brief motto ‘architecture in the service of society’ (Gürkan, 1969, unpaginated). This sort of ideological shift occurred between older and younger generations in Turkish context, resembles the same sequence of events occurred in the Western debate when the younger generation of Team 10 were dissociated from CIAM, and searched for a revised modernism above the orthodox modernist ideologies of their previous generation.

This study, within the periods under discussion, inquires the underlying reasons and the reinforcing evolvements, which comprised a basis for the rise of ‘social awareness’ in the Turkish architectural agenda. By also referring to the trans-national resemblances, the remarkable instances/or chain of events are evaluated in Turkish context, with the specific focus of the ‘user participation’ concept as the practical mediator of social awareness.

1.2 Aim and Scope

The socialist tendencies in architecture came to light as reaction against canonic features of the modernist architectural and urban planning strategies, which put emphasis on functionality, user passivity, professional authority and hierarchical design strategies. The first critical confrontations with modern architecture’s chief premises was generated by the Team 10, who were a younger group of intellectuals, discussing on concepts that were intended to prevail the social content of architecture and urbanism, by redefining the modern architecture tradition. After their break away from CIAM, this group sought alternative strategies which would leave a room for individual and collective identities, which would create meaningful environments capable of being appropriated by their residents and users (Risselada & Heuvel, 2005, p.12). With regard to the alertness for revealing social dimensions of architecture and urbanism, this study focuses particularly on one aspect of Team 10’s concerns which was the ‘establishment of a more democratic dialogue between the user and the architect’. This focus which meant the radical shift from the authoritarian architectural practice, to a more democratic one that aims to give people their rights to rise their voices for their built environments. By touching upon the criticisms of modern

4

architecture for losing its credibility, this study reviews the discourses focusing on ‘user participation’ as an alternative solution that challenges the status quo. Examining some archetypal international experiences, which were particularly selected from social housing projects, provide this study an insight into the theories and practices of ‘user participation’ by illustrating its key concepts, methods, aims, and ideologies from different lenses.

After gaining an adequate perception on the emergence and development of the ‘user participation’ concept in architecture in the wider world, specifically in housing practices, this study orientates its focus to the Turkish context. The selected time period of 1960s and 1970s of Turkey was deeply affected by the political instability, economic imbalance and social restructuring. The influences of both external factors, and internal dynamics entailed Turkey to confront multi-faceted transformations which reflected on the social and political agenda of the country (Tekeli, 2005, p.15). While providing a pragmatic reading of the era in Turkish context, which is generally seen as an era that was condemned to social chaos and political failure, this study principally gives prominence to the changing headings in the Turkish architectural debate in the period under discussion, by questioning the problem of housing regarding the rapid industrialization, and the consequent massive rural-to-urban migration.

As it will become clear throughout the following chapters, the rise of social awareness in the profession, and the ideological alteration of architects is evaluated, peculiarly by referring to two remarkable incidents: the ‘1969 Architecture Seminar’ and the ‘New Municipal’ movement. The former is brought forward within the study as it provided an environment for the search for the social meaning of architecture, while also reflecting the political and social characteristics of its period. The 1969 Architecture Seminar is evaluated as an important event where the positioning of architects was questioned in the existing urban circumstances and in its political dynamics. It considered as the discursive threshold for the socially charged young generation of architects who were moving forward with progressive, revolutionary and democratic motives in architecture. After demonstrating the increasing rhetoric on social awareness in architecture, ‘New Municipal’ movement is addressed as an instance of opportunity which allowed architects and planners of the generation of

5

1960s to involve as mayoral consultants, and practice their social democratic theories through the new municipal program. Under favor of the primary objectives of the New Municipals, which were the democratization of the municipality and people’s participation in local politics, the commissioned socially conscious architects followed the revisionist thoughts, and some of them even applied ‘user participation’ concept in the social housing projects initiated by the municipalities themselves.

Among other concurrent housing projects initiated by the ‘New Municipalities’, this study orients its focus on the one particular case study, which is the “İzmit New Settlements” project. Designed to be the largest-scale housing project of Turkey, which was initiated by the municipality of İzmit, this project challenged the status quo by practicing the egalitarian ways of space production without any dominating powers of the professionals. This project has a distinctive features from its concurrent counterparts for being the very first attempt in Turkey, that the theorized democratic generation process of architecture were tended to be experimented by the ‘participation’ of users in the steps of decision-making, idea generation and design of the project, with the contributions of the architects of the 1960’s generation as mayoral consultants. It is the most appropriate project that satisfies one of the main curiosities of the thesis that seeks the answers for why, when, how the ‘user participation’ did first brought into the Turkish architectural practice.

This study can be viewed as a contribution to the historical and contemporary studies by expanding the ubiquitous questions on the social ideals of architectural discipline, and the moral responsibilities of the architects over the European and American debates, by focusing on Turkish architectural agenda. By underscoring the global trajectories on the socialist criticisms in architecture, this research ponders how Turkish architectural culture responded to emanating social awareness along the 1960s and the 1970s, and points a particular project which embodied the circulating social tenets in the architectural circles.

6

1.3 Method and Sources

This research attempts to piece together the selected correlated references that were nominated as the actuators of the rise of social content in the profession of architecture. In order to detect the origination and the evaluation of the social consciousness in architecture, which turns a new page to modern architecture through offering a more democratic relation between design professionals and society, a profound research was obtained over a vast number of primary and secondary sources.

The route of the study found its flow by following different directions with diversified points of focus. However, the intention of the study has always been to chase the alternative ways of producing space. I have originally been concerned with the issues of injustice and inequality between different segments of society created by architectural practices that are taken over by non-egalitarian ideological powers. Therefore, it drove what I want to reveal through this study that is to question if there are any doctrines which may turn the domination of authoritative power relations of architectural theory and practice upside-down. That is how this study oriented towards the concept of ‘user participation’, which reverses the hierarchy in the operational structure of architecture from ‘top-down’ to ‘bottom-up’. It allows to give voice to people to have their words on their build environments, to the people who cannot afford architectural service otherwise by their economic situation and by their social status.

The first acquaintance with the concept of ‘user participation’ was procured under the guidance of my advisor, when he introduced me Giancarlo De Carlo, the only Italian founding member of Team 10, who was eloquently criticizing modern architecture and advocating an active democratic participation and equity in architecture. So, I started this study by reviewing De Carlo’s writings and projects, which he mostly reflected his visions that he wrote into his practices. One of his books that I reviewed was ‘Nelle Città del Mondo’, which he writes about his journeys and memories all over the world, including his hand drawings which he made during his travels. In one section of the

7

book that is titled “Da Ankara A İstanbul”, he tells his visit to Turkey in 1973.1 In the

very beginning of the chapter, he indicates the names of Suha Özkan and Feyyaz Erpi that they have travelled from Ankara to İstanbul together. This discovery, led to the interviews that I conducted with Suha Özkan, the first in Ankara Turkish Freelance Architects Association, and the other in Bodrum Architecture Library. Özkan’s personal communication with Giancarlo De Carlo, supplied peculiar details to the study, in terms of revealing to what extend Turkish architectural debate was influenced/if influenced by the cross-national ideological exchanges, specifically obtained by De Carlo’s visit to Turkey.2 What was discovered through the interviews

was the main reason behind De Carlo’s visit to Turkey in 1973; he was actually invited to give a series of conferences in Middle East Technical University (Suha Özkan was one of the coordinators of this invitation, together with Davran Eşkinat - the student of De Carlo from Venice, Italy), which could possibly be a platform that De Carlo might share his ideas on ‘user participation’ with Turkish architecture students, academicians, and practicing architects. That has been the point, which this study was motivated to be concerned with how ‘user participation’ concept came to light in the professional circles in Turkey, to what extent the Turkish architectural agenda influenced/if influenced by the international debates on the alternatives for the democratic production of space. Still not turning my back to Giancarlo De Carlo, I also visited Giancarlo De Carlo’s project archive at Università IUAV di Venezia, to attain any letters circulated between him and Turkish architects, or any reference of De Carlo to Turkish architects in the magazines of Casabella and Spazio e Società. Due to my very short stay, it was not possible to perform a consistent archival research, so I could not encounter any intended data. However, this kind of archival research, as a future goal, can be one of the possible ways to enlarge this study. Yet, I reached a personal letter of De Carlo, which he wrote to Behruz Çinici in 1968 to thank Çinici for his contribution to De Carlo’s book ‘Pianificazione e Disegno delle Università’

1 See; De Carlo, G. (1998a). Nelle Città del Mondo (2nd ed.). Venice: Marsilio.

2 For the personal interview conducted with Suha Özkan, see; Appendix A. See also; Özkan, S. (1998). “Toplum ve Mimarlık”ın Babası Giancarlo De Carlo 79 Yaşında. Arredamento, (4), 48-50. Additionally De Carlo’s article was also published in the same issue of Arredamento, see; De Carlo, G. (1998b). Başaşağı Edilmiş Piramit. Arredamento, (4), 51-55.

8

that includes METU, in SALT Research online archive (Figure 1.1).3 This detection

still contributed to this study to correlate some kind of intellectual exchanges between De Carlo and Turkish architects. Altuğ and Behruz Çinici’s social housing project in Çorum mentioned in the thesis.4 This is then why the focus of the study was shifted to

investigate the specific case of Turkey, as the project generated through the ideology of social tendencies of the architect, which shows that foreign national architects with parallel visions have already acquaint themselves with each other’s projects and created a cross-national socialist ideology in architecture.

These processes can be defined as a warm-up lap before widening the general content of the thesis. After determining the particular time period to be questioned throughout the study (that is the 1960s and the 1970s, which has a historically distinctive character in terms of being full of revolutionary views generated within architectural discourse globally), an overall literature review was made by scanning the international and Turkish architectural debates concentrated on the changing paradigms of architecture. Within the compass of the qualitative research, numerous types of sources were used, including books, digital books, articles, conference papers, conference/lecture/seminar broadcasts, journals (mainly Mimarlık, Arkitekt, Arredamento was used for Turkish context), online journal catalogs, documentaries, newspapers (obtained from National Library in Ankara), academic dissertations, online archive catalogs, photographs (including the personal archive of the author) and architectural drawings. To supplement the close scrutiny of literature review, the visual materials were critically analyzed in order to interpret the new discussions by comparing the figures, and to demonstrate the existing discussions which were incorporated in the thesis.

To further complement the information gathered through the literature review, and to explore the revisionist incidents of the period, semi-structured comprehensive interviews were conducted with architects, academicians, officials, locals and a politician. The interviews were designated as a direct means to have the first-hand

3 See; SALT Research. (1968). Letter About University Design Book that Includes METU. Retrieved from https://archives.saltresearch.org/handle/123456789/88018.

9

information through the personal experiences of the interviewees within the context of the research study, which also enriched thesis to be also participative itself. Apart from the aforementioned interviews carried out with Suha Özkan, a few more semi-structured comprehensive interviews were conducted with Aydan Erim, Önder Şenyapılı, İlhan Tekeli, Erol Köse, and also with the locals of Villaggio Matteotti, Terni, Italy (designed by Giancarlo De Carlo, Villaggio Matteotti appears in the thesis for being one of the prominent social housing projects applying ‘user participation’ in the architectural design process).

During the interview with Aydan Erim (her previous surname was ‘Bulca’), she provided her personal, never-before- written experiences pertaining to İzmit New Settlements project and the determined time period in general. She was a young academician when she was expelled from METU, and after, she was commissioned as a mayoral consultant of İzmit Municipality, as the coordinator of the New Settlements Project.

İlhan Tekeli, is an erudite academician who provided deep insights to the study extensively covering the general scope of the thesis. He has been an active professional and academician since his youth, therefore he has been substantially well-versed in the Turkish architectural debate with a broad interest in all social-political relations. Sharing the same fate with Aydan Erim, he was also one of the academicians who were expelled from METU. After his expulsion, he was commissioned as a mayoral consultant and actively took part in the activities of İzmit and Ankara Municipalities.

Önder Şenyapılı was also worked as a mayoral consultant in Ankara Municipality, however his featuring contribution was mainly on the 1969 Architecture Seminar, since he took an active role in the organization of the Seminar.

Lastly, during my visit to Terni, few interviews were made with some of the current residents of the Villaggio Matteotti who were also experienced the generation process of the project. This interview shed a light on the extent to which they were consulted on design, and also if De Carlo was successful in managing an applicable ‘user participatory’ design process. Since İzmit Project bears some ideological and practical

10

resemblances to the project of Villaggio Matteotti, understanding the users’ satisfactory levels in Terni, led to a prediction of success of the İzmit Project if the project would be actualized.

It is important to note that, it was crucial to acquire information from Aydan Erim, İlhan Tekeli and Erol Köse, especially for the selected case study of İzmit New Settlements Project, due to their active partaking in the regulation of the project at varied levels. Since the project could not be actualized, by reason of the administrative change of the İzmit Municipality in 1977, the accessible resources regarding the project remained limited. In spite of the negotiations with the related departments of the İzmit Municipality, no original documents, reports, technical drawings, sketches nor photographs related to the project could be obtained. Additionally, Tuncay Çavdar being the architect of the project, and Erol Köse being the mayor of İzmit in that period, were not holding any physical copies of any documentation of the project. Therefore, no archival data could be provided regarding the case study. The existing written sources of the project, apart from the oral interviews, were composed of the articles published in the journals of Mimarlık and Çevre, the newspaper clippings noticing the project, the number of book chapters, and the few academic dissertations mentioning the İzmit New Settlements Project as the precedent practice of ‘user participation’ in architecture in Turkey. Therefore, the interviews have been one of the supplementary sources to obtain more information about the project.

The abundant bibliography of the study aims to provide a list of multiple references for the prospective studies with correlative contextual analogies as this thesis.

1.4 Structure

This thesis is composed of six chapters including the introductory and concluding chapters.

After this first introductory chapter, the second chapter reviews the reactions that were raised against the basic doctrines of modern architecture, which were criticized for

11

failing to satisfy the exact needs of the society. The emergence of Team 10, after their break away from CIAM is mentioned as the crucial motive that changed the architectural agenda, through promoting a more democratic dialogue between the user and the architect, by challenging the hierarchical structuring of modern architecture. Particularly, by focusing on one of their concepts, named ‘user participation’ is introduced as the practical mediator of the ‘social awareness’ in architectural circles. This chapter reveals the international debates based on the social targets in processional and intellectual architectural venues, the re-evaluation of architect’s role, the re-definition of user’s domain in architectural practice. Some leading international experiments, such as from; Giancarlo De Carlo, Ralph Erskine, Walter Segal, Lucien Kroll, Christopher Alexander, which targeted ‘user participation’ are also highlighted with an alertness to grasp any relevancies to Turkish architectural debate.

In the third chapter, after gaining an adequate perception on the emergence and development of the social consciousness in architecture in the wider world, specifically in housing practices, the focus of the study is shifted towards Turkish context. In order to trace the changing views of the Turkish architectural agenda, this chapter serves to provide an insight to the social, political and economic contexts of the country as the integral perimeters of the architectural debates. Within the time period under interest, the unsteady politics, the consequential unbalanced economic policies and the evolving social structure of Turkey are evaluated; and their echoes upon the architectural agenda are examined. For being the common concern of political, economic and architectural circles, the housing question is pointed out and the inconsistencies of the housing programs after the 60s are reviewed. This review is made with an intention to remark that, to what extent the efforts of the state or the individual endeavors were sufficient/if sufficient to serve for the needs of a population that was truly in need of affordable housing.

The fourth chapter of the thesis is allocated for tracing the paths of ‘social awareness’ in Turkish architectural debate. After specifying the underlying reasons that could be both derived from the national and the international debates, the rise of social tendency among the Turkish architectural circles is examined. To emphasize the changing dynamics in the Turkish architectural agenda, the critical debates on the necessity of

12

the occupational change, and the reorientation of the role of the architects are underscored. Throughout this chapter, two critical remarks are brought forward for being the mediators to generate and develop the social content in architecture: the ‘1969 Architecture Seminar’ and the ‘New Municipal’ movement. The former is indicated to demonstrate the increasing rhetoric on social awareness in architecture, while the latter is addressed as an opportunity for architects to exercise their socially motivated ideologies.

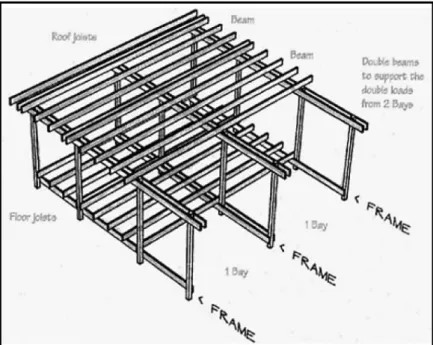

In the fifth chapter, ‘İzmit New Settlements’ project is reevaluated profoundly with regard to the historical framework drawn in the former chapters of the thesis. Initiated under the scope of the revisionist municipal program of İzmit, this project was aimed to be developed with a democratic dialogue between the architects and the possible users. Through this project, the architects, who were promoting the rise of social awareness in the profession, took part as mayoral consultants, and practiced their social democratic theories by applying ‘user participation’ concept along the whole design process. Since İzmit was an industrial city, the greater occupational group of its population was composed of workers, with all their potentials to self-organize. This paved a basis for the organizational structure of the project, that the future users were organized in cooperatives. These cooperatives formed the organizational framework of the project, and ensured an effective dialogue between the users, architects, and the local government. Additionally, to correspond with the ‘user participation’ concept, a special prefabrication building technology was customized. This construction system of the project was aimed to provide a structural flexibility that could adopt the changing needs of the users in time. Among other housing projects, which were concurrently initiated by the other ‘New Municipalities’, the ‘New Settlements’ project in İzmit reveals the revisionist ideals of the architects the furthest. Despite all these distinctive characteristics, this project could not be actualized, due to the unfortunate change of municipal administration. So, even though it was considered as an opportunity to actualize the socially oriented theories, due to its nonconsummation, the project became the theory itself. In addition to other features that distinct the project, this irony has also been one of the motivations to reevaluate the ‘New Settlements’ project as the leading experiment that brought up the social content of the architecture to the Turkish architectural agenda.

13

The last sixth chapter of conclusion, with a quick glance to the study, is devoted to a series of determinations, and is aimed to open up new areas of discussion for further studies.

14

CHAPTER 2

PARADIGM SHIFTS IN THE INTERNATIONAL

ARCHITECTURAL DEBATE

Participation in architecture became an increasingly visible strategy whose roots can be traced back to the widespread growth of community actions and social movements fighting for social democracy in post-war Western societies in 1960s. The discussions on ‘participation’ were brought forward as a historical reaction against modernist architectural and urban planning strategies with their emphasis on functionality, user passivity, professional authority and hierarchical design strategies. Early generation of CIAM modernists, ostensibly trying to build a socially progressive architecture, included the idea of user in their plans. With this aim in their minds, they created a model-user, which was theorized to fit in well with the determinants of modern norms. Due to the limitation of modernism’s repressive authoritarianism, this passive universal character of user, was not given a word to say for his/her exact needs. Architects isolated themselves from the real context of society and worked with the abstract users whose characteristics they invented. Therefore, the design codes generated in the abstract world could not overlap with the natural codes of the concrete world of users (Lefebvre, 1970). In the sequel, the distance between the world of designers and the world of users were increased, and cause a dissatisfaction for both architects and users (Page, 1972). After realizing the failings of orthodox modernism, there have been a number of attempts made to delineate systems of the ‘participation’ phenomenon which also expands over different disciplines.

In this chapter, first, a critical review will be made on the motives of the failings of orthodox modernism; the re-evaluation of architect’s role and the re-definition of users domain in architectural practice will be discussed, the initiators of the notion of ‘participation’ in processional and intellectual venues will be revealed; and finally some leading international experiments will be highlighted as the fragments that

15

formed the major precedents of participatory architecture with notifying their relevancies to Turkish architectural debate.

2.1 A Shift towards a Revised Modernism

In the early part of the 20th century, the visions of modernist architecture proliferated from the center toward the margins of Europe, and took hold of the architectural agenda with its radical doctrines. The older generation of CIAM modernists claimed science and positivism, and put emphasis on the concepts of ‘rationalism’ and ‘functionalism’. They saw it as their mission to use this techno-rationalism, infused with the aesthetic dogma against ornament, to solve the world's problems (Risselada & Heuvel, 2005, p.13). These former modernist protagonists of CIAM were captivated with the powerful machines of the 19th century. As Le Corbusier (1986) famously

declared, “A house is a machine for living in.” (p.95), the ‘classically’ modernist architects almost mimicked the efficiency and sleekness of machines in their designs.

The generation of 1928 of CIAM modernists, who formulated the Athens Charter, were motivated by the increasing population of cities resulting from industrial revolution. They began to concentrate their efforts on designing cities with the same characteristics as their buildings. This is important not only because it shows architects’ interest in urbanism, but also, it reveals the overt efforts of architects having social concerns. CIAM defined itself as an avant-garde association of architects who were intended to advance both modernism and internationalism in architecture and urbanism, and to revolutionize them to serve the interests of society (Mumford, 2002). Most of the architectural supports provided for the auspices of social reformation were proliferated through CIAM. Eric Mumford (2002) states that, “CIAM was a major force in creating a unified sense of what is now usually known as the Modern Architecture.” (p.1). The ideas generated and discussed among CIAM, gained force through their dissemination by CIAM members including some of the best-known architects of the twentieth century. Therefore, in the span of its operation, CIAM exercised a great influence over the built environment in many parts of the world.

16

Modern architecture and urban planning that were formed with CIAM’s dogmatism, were emphasizing rigid functionalism and determinism. One of the reasons of CIAM’s bankruptcy was due to this functional dogmatism which failed to apperceive the nuances of use by dictating uniformity, rather than variety (Zucchi, 1992, p.11). Thus, although CIAM started out with the aim of social democracy, it evolved into an elitist organization interested in pursuing its own authoritative program. The older generation of modern architects of CIAM were therefore charged with being seriously remiss in understanding the humane features of the individuals: “Ignoring...cultural differences and making most choices based on their own experience, most modern architects assumed that the users would become accustomed to living the way they expected them to live.” (Brolin, 1976, p.62).

The various surveys (physical, historical, sociological, and economic) that inform architectural practice became less informative, since the architectural solutions were tended to be relied on ‘typification’ of circumstances (Zucchi, 1992, p.13). The model situations and the model people that modern architecture brought discussed by De Carlo (1972) as follows: “… the model man has neither society nor history that his perimeters do not extend beyond the rotation of his members. His behaviors are no more than abstract descriptions, having little to do with the reality…” (Zucchi, 1992, p.13).5

This kind of abstraction in architectural design considered dangerous, since it might end up with losing sight to the real subject of the profession, the community. In case of not serving the communities, architecture becomes unquestioning, self- referential and mechanical. Architects have been widely criticized for their authoritarian attitudes and narrow-spectrum of their architectural visions. Their failure in overlooking the complexities of human affairs, caused a severe request to do justice to the complexity of a pluralist society (Zucchi, 1992).

5 The quotation is retrived from Zucchi, B. (1992). Giancarlo De Carlo (p.13). Oxford: Butterworth Architecture. For the primary source, see; De Carlo, G. (1972). An Architecture of Participation. Melbourne: Royal Australian Institute of Architects.

17

2.2 The Changing Dynamics between the Architect and the User

“In different historical epochs, depending on the use to which political power put him, the architect has been more a head-brick-layer or more a god. If not exactly head-brickhead-brick-layer, he was certainly head builder at the end of the middle ages and the beginning of the Renaissance. If not exactly God, then he was high priest and custodian of state secrets in ancient Egypt from the first Dynasty to the conquest of Alexander.” (De Carlo, 2005, p.5.)

In his words, De Carlo clearly intended that, in all epochs, whatever the importance of his role was, architect has been subjected to the world view of those who were in power. Since the act of an architect was requiring money, resources, land and authority, and since the ruling power was the only force capable of offering these means, architect represented his identity as being the operative member of the class in power (De Carlo, 2005). His duties were limited to the study and application of building technology (later urban planning and environmental planning), through which he both found his dignity and his earnings. However, in the course of his operations he was not referring his activities to a more general political condition. Architecture continued to follow the same path from medieval cathedral builders through bourgeois specialization and the industrial revolution.

Mumford (2002) states that, “much of the international network now in place involved with conceptualizing and re-conceptualizing the role of the architects in the design of urban environments can be traced back to CIAM. As Bozdoğan (2002) argues, only with the Modern Movement was the traditional patronage relations defining the architectural profession yielded to a new definition of the architect along a technocratic and professional model (p.152). However, even though some humanist rhetoric of modern architecture was witnessed in CIAM sayings, architecture has still continued to favor the client over the user; and architects’ role have still stayed ambiguous. The serious failing of the Modern Movement was its deliberate programmatic attitude of an elite. In an attempt to question the credibility of the profession, De Carlo (2005) insisted on finding the answer of the most critical question; “what is architecture’s

18

public?” (p.6). He, without hesitation, answered it by saying that, “…architecture’s public are not the architect themselves, or the clients who commissioned the buildings, but the people who use architecture are its public.” (De Carlo, 2005, p.7). Yet, the problem with field which the Modern Movement intended to operate, was already formed as being restricted to relations between clients and entrepreneurs, landowners, critics, and architects (De Carlo, 2005, p.7). Therefore, it was already a field which was structured on economic and social class interests and held together with the ties of cultural and aesthetic class codes. The vanguards of modern architecture who were searching ways to conquer in this field, initially had some intentions to work beyond these limits of power. Yet, they somehow leaned out their elite positions, and excluded any other cultural, social, economic and aesthetic values that were not shared by the class in power. At this point, it can be stated that, the Modern Movement lost its track of the most important insights when it took the elite position on the side of the client rather than on the side of the user. However, there were some daring free spirits excluded themselves from the majority of modern architects following the dogmas set by the CIAM, searched for the newness, and stood on the side of the general public (De Carlo, 2005, p.7). Their focus was shifted from wealthy ‘client’ with political or financial power, to ‘user’ which was later began to be considered as ‘participant’ of the architectural production. Through this new description of the ‘participant’, the ‘user’ became a serious subject that affected the hierarchical act of the architectural discipline.

State of Crisis due to Urban Renewal

The second half of the 20th century was formed dominantly by the Second World War and its adverse effects on urban life. In the post-war period, cities surrendered to face their total annihilations. Being one of the most vital problems of the period regarding the rebuilt of the urban areas and life, the physical and social conditions of housing, resulted in the eventual reflections from both professionals and society (Toker, 2000). At that period of 1950s, “the landowning capital and state bureaucracy had combined interest that this situation prepared the brutal operation known as urban renewal” (De Carlo, 2005, p.10). American and European cities witnessed the segregation of classes in physical space, which can be defined as the extension of social inequality. Wealthy

19

classes remained in the valuable zones, where reserved for the houses of the rich, for the most profitable economic activities, for bureaucracy and politics; while poor (such as negroes, immigrants, proletariat, foreign workers, or workers of any kind) were excluded to the outskirts of the city where they were cut off from the real life in their minimum standard housings. As De Carlo (2005) remarks: “The unconsciousness – or rather congenital irresponsibility – of architecture about motivations and consequences, had contributed decisively to the expansion of social iniquity in its most ferocious and shameful aspect: the segregation of classes in physical space.” (p.11).

To simply put, due to its elitist position, architecture has lost its ability to ground people’s individuality, and steadily moved away from engagement from social issues. Even such issues like affordable and appropriate housing, manageable urban areas and environmental quality fall in the realm of their professional competence, architects’ proposals for these issues have not satisfied the groups in need (Crawford, 1991). So that, in progress of time, architectural proposals on houses, neighborhoods, suburbs and cities, became obvious manifestations of an abuse perpetrated on the poor. These dissatisfactions formed a basis to the reactions of community which became effective through protests in the United States and Western Europe during the 1960s. These protests were mainly against the authority who excluded the community in decision-making processes over time, and the prominent arguments of them were based on anti-war movement, human rights, women’s liberation movement, challenges of alternative cultures, a non-discriminatory social welfare and rights for having a say for shaping of their own environment due to the disruptive consequences of urban renewal.

2.3 The Rise of Participation

A younger generation of modern architects, who were sharing a profound distrust and dissatisfaction to the CIAM’s canonic doctrines of architecture and urbanism, triggered a process of having the control over the organization. They recognized that the crude schematizations of CIAM could not do justice to the complexity of a pluralist society (Zucchi, 1992, p.27). Since it was mostly equated with deterministic, formalist, and above all functional architecture and city planning, CIAM came to be seen as a

20

negative symbol against which many ‘alternative’ or ‘radical’ architectural practices developed (Mumford, 2002).

In 1956 in Dubrovnik, the tenth CIAM meeting was organized by this younger generation of modernist architects, who were later nicknamed as ‘Team 10’; and, this started the dissolution process of CIAM. At the final congress held in Otterlo in 1959, the legendary organization of CIAM came to an end (Risselada & Heuvel, 2005). This formation in the ongoing process of modernization indicated a renewed significance in social responsibility in architecture. The intent was to revitalize the inanimate prototypes of the modern language of architecture and to allow this new language communicate society’s unfulfilled needs and undefined longings (Boyer, 2005).

Until the beginning of the 1960s, the planning and design professions remained isolated from the aspirations and needs of the community. This disconnection, caused the reactions of community which became effective through protests in the United States and Western Europe during the early 1960s. These protests were mainly against the authority who excluded the community in decision-making processes over time, and the prominent arguments of them were based on anti-war movement, human rights, women’s liberation movement, challenges of alternative cultures, a non-discriminatory social welfare and rights for having a say for shaping of their own environment due to the disruptive consequences of urban renewal. The community protests against top-down approaches, supported the idea that all citizens should have more leading and central role in planning, design and the production of urban environments. Thus, together with the community reactions, 1960s have been the period which was characterized with the experimental forms of architectural practice and production (Sanoff, 2000; Toker, 2012; Toker, 2000). As Jones (2005) described the mood of 60’s as optimistic, utopian, and egalitarian, it was also at this time that the first participatory architectural practices were developed. De Carlo (2005) stated that, discovering the real needs of the users gained the priority, therefore exposing and acknowledging their rights to express themselves became crucial (p.18). Giving their rights to express themselves, means provoking a direct participation of the users as the part of the design processes. It also means, questioning all the traditional value systems of architecture which were built on authoritative, non-participatory orders.

21

2.4 Illustrating the Debates on Participation

The 1960s changed the perception of space and the production of space. The conception space moved beyond solely being a physical object, it started to be defined as a social phenomenon (Lefebvre, 1991). The architectural design which had been an authoritarian act up to this time, transformed to be more user-oriented. Rather than privileging the ones in power, it put more emphasis on empowering the ordinary citizens/users. The classical modernist formalism was disrupted with the determination of real needs of the users. With the concern for ‘participation’, the authoritarian and repressive conditions of the conventional methods of architecture were refuted. The idea of incorporating the user more systematically and consciously in the design process as a participant was stated to be discussed within the design disciplines. In this part of the study, some archetypal international experiences are examined, with the main intent to, first, to illustrate some of the key concepts and issues identified through international experiments of ‘participation’ in the architectural practice, and second, to illustrate some parallels of these practices to the Turkish experiences.

Based on the spread of community action and social protests fighting for social democracy in the 1960’s, American activist planner Paul Davidoff launched a pluralistic debate on participatory design practice.6 Davidoff’s concept of ‘advocacy’ has radically evolved into the idea of ‘advocacy planning’ and had a profound effect on the characterization of architecture and urban planning as an engaged and participatory process of positive social change.7 He urged planners to proceed not only as government representatives, but also as advocates to the public and other interest groups (Davidoff, 1965). Davidoff’s advocate views on planning supported by Sanoff (2000) who states that, since the citizens are more aware of the realities of their own

6 See; Davidoff, P. (1965). Advocacy and Pluralism in Planning. Journal of the American Institute of

Planners, 31 (4), 331-338. Doi: 10.1080/01944366508978187

7 Upon Davidoff’s concept of ‘advocacy planning’, ‘Community Design Centers (CDCs)’ emerged in the United States. The CDCs aimed for providing technical and design advice to communities who could otherwise not afford it. Architects and planners, who were influenced by Davidoff’s proposal, give voluntary professional support to CDCs (Sanoff, 2000). These professionals viewed themselves as advocates for those excluded from the design process, and represented the demands and concerns of the excluded community groups (Comerio, 1984; as cited in Sanoff, 2000).