Background: Postpartum hemorrhage (PPH) is one of the emergency situations of obstetrics practice that constitutes of 1 to 5% of vaginal and cesarean deliveries. Uterine atony is the number one cause of PPH and is responsible for at least 75% of PPH cases. Uterine compression sutures have been regarded as an effective method in PPH cases, as well as preserving fertility by preserving the uterus. Aims: The main purpose of this study was to report on our results with a new uterine compression suture technique that was developed by us. Subjects and Methods: In this study we included all women who needed uterine compression sutures because of uterine atony while cesarean section from January 2014 to December 2018. Fifteen cases with PPH with uterine atony were reported, who were treated with our uterine compression suture technique after conservative medical and uterine massage treatment failure. Results: All of the cases in this study were managed successfully namely none of the patients needed a hysterectomy or reoperation because of bleeding again. One week, one month, three months later all patients were followed up. Six months later 11 patients were examined, four patients lost to follow‑up, but they were reached by phone since they were outside of the city, they reported no complaints. Ultrasound examination was performed to follow up patients. Short‑term follow‑up revealed no complications such as pyometra, endometritis, reoperation, amenorrhea, or uterine necrosis. Conclusions: We described our practice with our uterine compression suture that is easy to learn and apply. All of the cases that participated in our study showed improvement to the compression sutures, so no other surgical interventions were applied. The same suture technique was applied by only one physician. This is a feasible and easy way to stop bleeding in uterine atony and in uterine preservation, especially in rural areas when help may not be available in case of complications.

Keywords: Cesarean section, compression suture, postpartum hemorrhage, uterine atony

A New and Feasible Uterine Compression Suture Technique in Uterine

Atony to Save Mothers from Postpartum Hemorrhage

G SEL, İİ Arıkan1, M Harma, Mİ Harma

Address for correspondence: Dr. G SEL, Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, Zonguldak Bülent Ecevit University Hospital, Zonguldak, 67000, Turkey. E‑mail: gorkersel@gmail.com

PPH is one of the most important reasons for maternal mortality in the globe.[6,7] The mortality risk is much lower in the developed countries than in the developing countries (1 in 100,000 versus 1 in 1000 births).[8] Uterine atony is the number one cause of PPH, and is responsible for at least 75% of PPH cases.[9]

Introduction

P

ostpartum hemorrhage (PPH) is one of the emergency situations of obstetrics practice that constitutes of 1–5% of vaginal and cesarean deliveries,[1,2] For vaginal delivery, this is defined as blood loss greater than 500 ml while for a cesarean delivery some studies defined as blood loss greater than 1000 ml.[3,4] Another definition of PPH is blood loss sufficient to cause hypovolemia, a 10% drop in hematocrit or requiring transfusion of blood products regardless of the route of delivery.[5]Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, Zonguldak Bülent Ecevit University Hospital, Zonguldak,

1Department of Obstetrics

and Gynecology, Beykent University, İstanbul, Turkey

Abstract

How to cite this article: Sel G, Arikan İİ, Harma M, Harma Mİ. A new and feasible uterine compression suture technique in uterine atony to save mothers from postpartum hemorrhage. Niger J Clin Pract 2021;24:335-40.

Access this article online

Quick Response Code:

Website: www.njcponline.com

DOI: 10.4103/njcp.njcp_140_20

This is an open access journal, and articles are distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution‑NonCommercial‑ShareAlike 4.0 License, which allows others to remix, tweak, and build upon the work non‑commercially, as long as appropriate credit is given and the new creations are licensed under the identical terms.

For reprints contact: reprints@medknow.com

Received: 28-Mar-2020; Revision: 24-May-2020; Accepted: 08-Jul-2020; Published: 15-Mar-2021

The conventional management of PPH in uterine atony cases begins with medical and non‑invasive methods, like bimanual massage of the uterus, uterotonics, and application of a Bakri balloon.[10] The medical treatment fails in less than 1% of cases.[11] In these cases, management strategies involve uterine compression sutures such as B‑Lynch,[12] U‑type sutures,[13] or other techniques described by Hayman,[14] Pereira,[15] and Cho.[16] Uterine compression sutures have been regarded as an effective method in PPH cases, as well as preserving fertility by preserving the uterus. Fertility preserving procedures other than uterine compression sutures include; internal iliac artery ligation, uterine artery ligation, and selective uterine artery embolization.[17] Emergency per partum hysterectomy is the last chance to save patient’s life in postpartum period for hemorrhage which is unresponsive to fertility preserving treatments.[18]

The main purpose of this study was to report on our results with a simplified uterine compression suture technique that was developed by us. We evaluated its success in managing cases with PPH after conventional methods fail.

Materials and Methods

We reviewed of all cases of PPH that applied our uterine compression suture technique in January 2014–December 2018 at Bartın State Hospital and Zonguldak Bülent Ecevit University Hospital. In our research we strictly obeyed to “Compliance with Ethical Standards”. ZBEU Ethics Committee approval number: 2018‑103‑28/03‑21. Written informed consent was taken from every patients. In this study we included all women who needed uterine compression sutures because of uterine atony unresponsive to the conventional therapies after cesarean section (CS) during the study period. About 8,000 deliveries occurred during this period. Fifteen cases with PPH with uterine atony experienced by the same obstetrician (GS) were treated with simplified uterine compression sutures after conservative medical and uterine massage treatment failure, were reported. Clinical, laboratory, surgical, and follow‑up data were collected.

CS was performed via Pfannenstiel incision. The uterus was exteriorized and hysterotomy incision was sutured with Polyglactin 910 (Synthetic absorbable, size 0, undyed braided, 27” (70 cm) suture, Ethicon, Coated Vicryl ®), as routinely done in CS. When uterine atony occurred, first of all, uterotonic therapies, oxytocin infusion (40 units in 1 L of normal saline intravenously), methylergonovine maleate (ergot alkaloid) injection (0.2 mg intramuscularly) and rectal Prostaglandin E1,

namely misoprostol (800 micrograms‑4 tablets) were applied along with manual compression and uterine fundal massage. Also 1 gr tranexamic acid, which is an antifibrinolytic agent, in 10 ml intravenously administered in 10 minutes and additional 1 dose is applied if bleeding continues after 20 minutes.

When uterine atony was unresponsive to uterotonic drugs and uterine massage in approximately 15–20 minutes, our uterus compression suture technique was performed. Estimated blood loss (EBL) was intraoperatively estimated by direct measure of blood in suction canister along with counting sponges at the end of the operations. Description of the uterus compression technique 1. Bilateral Fundal Sutures: The uterus is exteriorized.

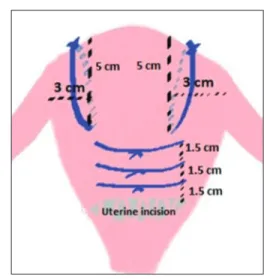

A straight needle with Polyglactin 910 (Synthetic absorbable, size 0, undyed braided, 27” (70 cm) suture, Ethicon, Coated Vicryl ®) is passed 2‑3 cm from the lateral borders of the uterus, 4‑5 cm from the upper borders of the uterus fundus, from the serosa of the anterior to posterior uterine wall through uterine cavity until no space is left in the uterine cavity. By this way 2 sutures are passed, left and right knot is tied as tightly as possible on the fundus of the uterus, respectively as shown on Figure 1.

2. Uterine corpus sutures: After right and left fundal sutures are tied, as described above, then again a straight needle with Vicryl 0 (Polyglactin 910) is passed 1–2 cm below fundal sutures from the serosa of the anterior uterine wall through uterine cavity to serosa of the posterior uterine wall. Then that thread and needle is passed 4–5 cm lateral to the point that the needle was passed, this time from the posterior to the anterior uterine wall through uterine cavity. That knot is tied, as tightly as possible to compress uterine walls, on the anterior wall of the uterus. Two or three horizontal uterine whole thickness sutures 1–2 cm apart from each other, anterior to posterior and then posterior to anterior passing through the entire layers, are placed on the uterine corpus, knot is tied on the anterior surface of the uterus as shown on Figures 2, 3 and 4. By those sutures, uterine corpus is compressed without letting total ischemia of the uterine corpus.

Results

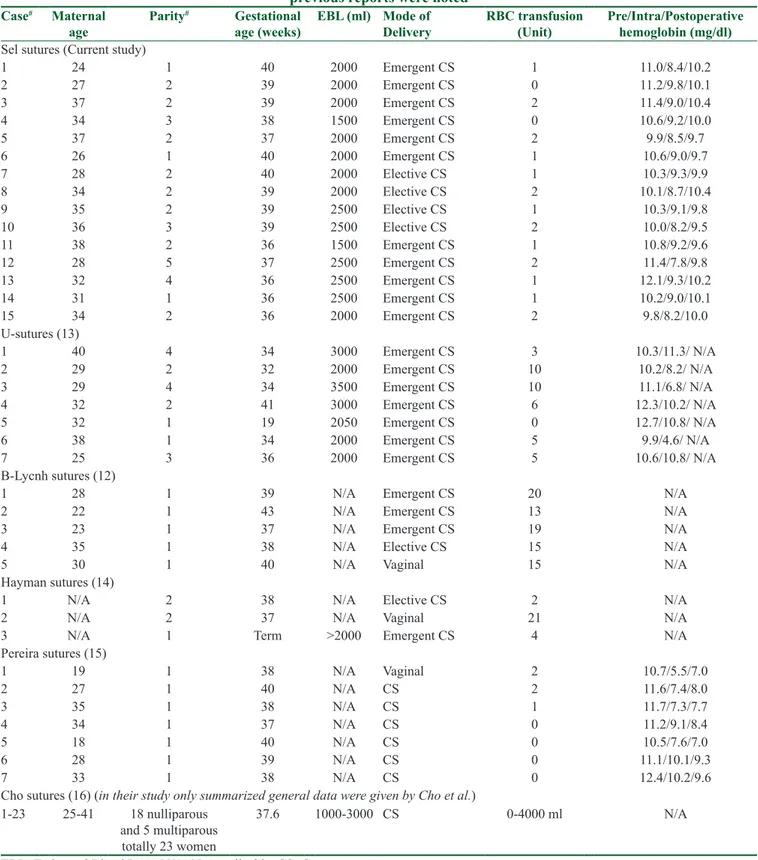

Our uterine compression suture technique was applied to 15 patients with uterine atony unresponsive to uterotonics and uterine massage; these cases occurred during CS from January 2014 to December 2018. The results are summarized with other types of compression sutures in Table 1.

All of the cases in this study were managed successfully namely none of the patients needed a hysterectomy or reoperation because of bleeding again. On average, patients were discharged five days after the operation. One week, one month, three months later all patients were followed up. Six months later 11 patients were examined, four patients lost to follow‑up, but they were reached by phone since they were outside of the city, they reported no complaints. Ultrasound examination was performed to followed up patients. Short‑term follow‑up revealed no complications such as pyometra, endometritis, reoperation, amenorrhea, or uterine necrosis.

Discussion

PPH is a life‑threatening obstetric emergency. Women in low‑income countries and lower middle‑income countries have an increased likelihood of severe PPH and of dying from PPH‑related consequences.[7] Generally, uterotonic medical treatment is successful. However,

when atony is unresponsive to uterotonics and uterine massage, then surgical interventions are needed. These methods must be efficient when preserving fertility is desirable, especially in young patients. Hysterectomy is another option, but it should be reserved when uterine preservation is not possible.

The logic behind all uterine compression procedures is to control bleeding by surgical tamponade of the uterus. In 1997, Christopher B‑Lynch reportedon the first widely utilized uterine compression suture.[12] In his article, B‑Lynch reported five cases with atony and concluded that the suturing technique had been successfully applied with no problems to that date and no apparent complications.[12] Hayman et al. then described the vertical placement of two to four compression sutures from the anterior to the posterior wall of the uterus on three patients with atony, concluded that compression sutures placed into the postpartum uterus might provide a simple first surgical step to control bleeding when routine oxytocic measures had failed.[14] In our method we also performed vertical stiches but with a difference of the length of the sutures. In Hayman’s method the Figure 1: Bilateral fundal sutures, anterior view Figure 2: Horizontal sutures, final result, anterior view

Figure 4: Final result, anterior view Figure 3: Horizontal sutures, final result, posterior view

Table 1: Chart reports of PPH and uterine atony patients that needed compression sutures using our technique and previous reports were noted

Case# Maternal

age Parity

# Gestational

age (weeks) EBL (ml) Mode of Delivery RBC transfusion (Unit) Pre/Intra/Postoperative hemoglobin (mg/dl)

Sel sutures (Current study)

1 24 1 40 2000 Emergent CS 1 11.0/8.4/10.2 2 27 2 39 2000 Emergent CS 0 11.2/9.8/10.1 3 37 2 39 2000 Emergent CS 2 11.4/9.0/10.4 4 34 3 38 1500 Emergent CS 0 10.6/9.2/10.0 5 37 2 37 2000 Emergent CS 2 9.9/8.5/9.7 6 26 1 40 2000 Emergent CS 1 10.6/9.0/9.7 7 28 2 40 2000 Elective CS 1 10.3/9.3/9.9 8 34 2 39 2000 Elective CS 2 10.1/8.7/10.4 9 35 2 39 2500 Elective CS 1 10.3/9.1/9.8 10 36 3 39 2500 Elective CS 2 10.0/8.2/9.5 11 38 2 36 1500 Emergent CS 1 10.8/9.2/9.6 12 28 5 37 2500 Emergent CS 2 11.4/7.8/9.8 13 32 4 36 2500 Emergent CS 1 12.1/9.3/10.2 14 31 1 36 2500 Emergent CS 1 10.2/9.0/10.1 15 34 2 36 2000 Emergent CS 2 9.8/8.2/10.0 U‑sutures (13) 1 40 4 34 3000 Emergent CS 3 10.3/11.3/ N/A 2 29 2 32 2000 Emergent CS 10 10.2/8.2/ N/A 3 29 4 34 3500 Emergent CS 10 11.1/6.8/ N/A 4 32 2 41 3000 Emergent CS 6 12.3/10.2/ N/A 5 32 1 19 2050 Emergent CS 0 12.7/10.8/ N/A 6 38 1 34 2000 Emergent CS 5 9.9/4.6/ N/A 7 25 3 36 2000 Emergent CS 5 10.6/10.8/ N/A B‑Lycnh sutures (12)

1 28 1 39 N/A Emergent CS 20 N/A

2 22 1 43 N/A Emergent CS 13 N/A

3 23 1 37 N/A Emergent CS 19 N/A

4 35 1 38 N/A Elective CS 15 N/A

5 30 1 40 N/A Vaginal 15 N/A

Hayman sutures (14)

1 N/A 2 38 N/A Elective CS 2 N/A

2 N/A 2 37 N/A Vaginal 21 N/A

3 N/A 1 Term >2000 Emergent CS 4 N/A

Pereira sutures (15) 1 19 1 38 N/A Vaginal 2 10.7/5.5/7.0 2 27 1 40 N/A CS 2 11.6/7.4/8.0 3 35 1 38 N/A CS 1 11.7/7.3/7.7 4 34 1 37 N/A CS 0 11.2/9.1/8.4 5 18 1 40 N/A CS 0 10.5/7.6/7.0 6 28 1 39 N/A CS 0 11.1/10.1/9.3 7 33 1 38 N/A CS 0 12.4/10.2/9.6

Cho sutures (16) (in their study only summarized general data were given by Cho et al.) 1‑23 25‑41 18 nulliparous

and 5 multiparous totally 23 women

37.6 1000‑3000 CS 0‑4000 ml N/A EBL=Estimated Blood Lose, N/A=Not applicable, CS=Cesarean

needle is inserted at the lower uterine segment from anterior to the posterior sides, which is a long distance from lower uterine segment to be tied at the fundus of the uterus and also it could be easily detached or got

loosen. Because of that we performed vertical sutures in a short distance as fundal sutures, as we described above. Addition to those vertical sutures, we added transverse sutures to compress the uterus imitating

bimanual uterine massage and without putting the uterus in an ischemia. Pereira et al. reported another technique that series of transverse and longitudinal sutures are placed around the uterus via a series of sutures into the sub‑serosal myometrium on their series with seven patients with atony and postpartum hemorrhage.[15] Two or three lines of these sutures are applied in each direction to completely envelop and compress the uterus and finally, the combination of longitudinal and transverse sutures not only aids compression but also collapses the lumen of ascending branches of the uterine artery, reducing vascular flow and venous bleeding.[15] Cho et al. defined another technique where multiple square knots are performed to compress uterus in 23 women with postpartum hemorrhages at cesarean who did not respond to conservative treatment, in all patients hysterectomy had been avoided.[16]

We described our practice with our uterine compression suture that is easy to learn and apply. All of the cases that participated in our study showed improvement to the compression sutures, so no other surgical interventions were applied. The suture technique was applied by only one physician (GS) and the same method was consistently applied.

The advantages of our technique are that it is easy to learn and apply; moreover, we suture the stitches step by step, thereby preventing loosening of the whole knot and starting again, as could be experienced in the B‑Lynch technique. Our knots do not completely put the uterus in an ischemic situation, preventing blood passage to the uterus and leading to necrosis of the uterus, as has been seen in other techniques.[19‑21] Long‑term complication of B‑Lynch technique such as antenatal uterine rupture encountered at 32 weeks of gestation after previous B‑Lynch suture, is also experienced, in the literature.[22] Importantly, sutures passing through the full thickness and covering the whole longitudinal segment of the uterus can lead to uterine ischemia and necrosis. Therefore, we apply sutures in short lengths in order to tamponade the uterus.

Conclusions

Our uterus compression suture technique is simple, but the response rate is satisfactory. The moderate number of patients treated with this technique is the main limitation of this study. Nonetheless, this kind of uterine atony and compression sutures studies generally include less number of patients, as discussed above referred techniques were investigated on 3–23 patients in the literature.[12,14‑16] Before making the decision to perform a hysterectomy, our suture technique would help to preserve the uterus namely the fertility of the woman.

Financial support and sponsorship Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

References

1. Reynders FC, Senten L, Tjalma W, Jacquemyn Y. Postpartum hemorrhage: Practical approach to a life‑threatening complication. Clin Exp Obstet Gynecol 2006;33:81‑4.

2. Sheldon WR, Blum J, Vogel JP, Souza JP, Gülmezoglu AM, Winikoff B. Postpartum haemorrhage management, risks, and maternal outcomes: Findings from the World Health Organization Multicountry Survey on Maternal and Newborn Health. BJOG 2014;121(Suppl 1):5.

3. Stafford I, Dildy GA, Clark SL, Belfort MA. Visually estimated and calculated blood loss in vaginal and cesarean delivery. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2008;199:519, e1–e7.

4. ACOG Practice Bulletin No. 183: Postpartum Hemorrhage. Obstetr Gynecol 2017;130:e168‑86.

5. Weisbrod AB, Sheppard FR, Chernofsky MR, Blankenship CL, Gage F, Wind G, et al. Emergent management of postpartum hemorrhage for the general and acute care surgeon. World J Emerg Surg 2009;4:43.

6. Khan KS, Wojdyla D, Say L, Gülmezoglu AM, Van Look PF. WHO analysis of causes of maternal death: A systematic review. Lancet 2006;367:1066‑74.

7. Maswime S, Buchmann E. A systematic review of maternal near miss and mortality due to postpartum hemorrhage. Int J Gynaecol Obstet 2017;137:1‑7.

8. World Health Organization, Unicef. Trends in maternal mortality: 1990 to 2013: Estimates by WHO, UNICEF, UNFPA, The World Bank and the United Nations Population Division. Available from: https://www.who.int/reproductivehealth/publications/monitoring/ maternal‑mortality‑2013/en/. [Last accessed on 2020 Mar 01]. 9. Marshall AL, Durani U, Bartley A, Hagen CE, Ashrani A. The

impact of postpartum hemorrhage on hospital length of stay and inpatient mortality: A National Inpatient Sample‑based analysis. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2017;217:344.e1.

10. Bakri YN. Balloon device for control of obstetrical bleeding. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol 1999;86:S84.

11. Prendiville WJ, Elbourne D, McDonald S. Active versus expectant management in the third stage of labour. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2000;CD000007. doi: 10.1002/14651858. CD00000.

12. B‑Lynch C, Coker A, Lawal AH, Abu J, Cowen MJ. The B‑Lynch surgical technique for the control of massive postpartum haemorrhage: An alternative to hysterectomy? Five cases reported. Br. J Obstet Gynaecol 1997;104:372‑5.

13. Hackethal A, Brueggmann D, Oehmke F, Tinneberg HR, Zygmunt MT, Muenstedt K. Uterine compression U‑sutures in primary postpartum hemorrhage after cesarean section: Fertility preservation with a simple and effective technique. Hum Reprod 2008;23:74‑9.

14. Hayman RG, Arulkumaran S, Steer PJ. Uterine compression sutures: Surgical management of postpartum hemorrhage. Obstet Gynecol 2002;99:502‑6.

15. Pereira A, Nunes F, Pedroso S, Saraiva J, Retto H, Meirinho M. Compressive uterine sutures to treat postpartum bleeding secondary to uterine atony. Obstet Gynecol 2005;106:569‑72. 16. Cho JH, Jun HS, Lee CN. Hemostatic suturing technique for

2000;96:129‑31.

17. Api M, Api O, Yayla M. Fertility after B‑Lynch suture and hypogastric artery ligation. Fertil Steril 2005;84:509‑e5.

18. Uysal D, Cokmez H, Aydin C, Ciftpinar T. Emergency peripartum hysterectomy: A retrospective study in a tertiary care hospital in Turkey from 2007 to 2015. J Pak Med Assoc 2018;68:487‑9.

19. Reyftmann L, Nguyen A, Ristic V, Rouleau C, Mazet N, Dechaud H. Partial uterine wall necrosis following Cho hemostatic sutures for the treatment of postpartum hemorrhage. Gynecol Obstet Fertil 2009;37:579‑82.

20. Akoury H, Sherman C. Uterine wall partial thickness necrosis following combined B‑Lynch and Cho square sutures for the treatment of primary postpartum hemorrhage. J Obstet Gynaecol Can 2008;30:421‑4.

21. Benkirane S, Saadi H, Serji B, Mimouni A. Uterine necrosis following a combination of uterine compression sutures and vascular ligation during a postpartum hemorrhage: A case report. Int J Surg Case Rep 2017;38:5‑7.

22. Pechtor K, Richards B, Paterson H. Antenatal catastrophic uterine rupture at 32 weeks of gestation after previous B‑Lynch suture. BJOG 2010;117:889‑91.