Clinical Surgery-International

Torsion of the primary epiploic appendagitis: a case

series and review of the literature

Suleyman Ozdemir, M.D.

a,b,*, Kamil Gulpinar, M.D.

a,b, Sezai Leventoglu, M.D.

b,

Hatim Yahya Uslu, M.D.

a, Erdem Turkoz, M.D.

c, Necdet Ozcay, M.D.

b,

Atila Korkmaz, M.D.

a aDepartment of Surgery, Ufuk University, Medical School, Mevlana Bulvari 86-88 Mevlana, 06520, Ankara, Turkey; b

Department of Surgery, Ankara Guven Hospital, Ankara, Turkey;cDepartment of Surgery, Ankara Guven Hospital,

Ankara, Turkey

Abstract

BACKGROUND: Differential diagnosis and appropriate treatment of epiploic appendagitis (EA) is a dilemma for general surgeons because of nonspecific signs and symptoms.

METHODS: Twelve patients (3 women and 9 men, average age 40 years, range 18 – 82 years) who were diagnosed as having EA upon presenting to the emergency department or at the time of discharge between April 2002 and September 2008 were included.

RESULTS: The major presenting symptom was abdominal pain. Physical examination revealed well-localized tenderness in all cases (n⫽ 12); in addition, rebound tenderness and distention were also observed. Laboratory blood tests were normal except for 4 patients who had leukocytosis. Seven cases were diagnosed by an abdominal computed tomography scan. Five patients required surgical interven-tion, whereas the remaining did not.

CONCLUSIONS: Surgeons should be aware of this self-limiting disease that mimics many other intra-abdominal acute conditions. An abdominal computed tomography scan has a significant role in accurate diagnosis of EA before surgery to avoid unnecessary surgical interventions.

© 2010 Elsevier Inc. All rights reserved. KEYWORDS:

Epiploic appendagitis; Torsion;

Acute abdominal pain

Primary epiploic appendagitis (EA) is an ischemic in-flammatory condition that may arise from torsion, sponta-neous venous thrombosis, or inflammation in one of the hundreds of appendices epiploica.1 Patients may present with severe and focal abdominal pain at the site of infarction and or inflammation, which may mimic other acute abdom-inal conditions (ie, appendicitis, diverticulitis, hernia, or cholecystitis).2– 4 If the diagnosis of EA is achieved by noninvasive methods such as abdominal computed tomog-raphy (CT) techniques, it can be managed conservatively.

Unfortunately, accurate and final diagnosis of the disease, in general, is often hard to attain without surgery. However, with careful physical examination and awareness of the characteristic imaging findings, surgery can be avoided.

Patients and Methods

Data for the presented cases were collected from Ufuk University Faculty of Medicine Department of Surgery (n⫽ 2) and Ankara Guven Hospital Emergency Service (n ⫽ 10) between April 2002 and September 2008. Among 2,500 visits annually in each hospital, 12 patients (3 women and 9 men) were diagnosed with symptomatic EA, and the mean age was 40 years (range 18 – 82 years). All patients were evaluated by the same clinician (first author) and diagnosed

* Corresponding author. Tel.:⫹0090-533-323-2502; fax:

⫹0090-312-204-4055.

E-mail address:drsozdemir@hotmail.com

Manuscript received January 17, 2009; revised manuscript February 16, 2009

0002-9610/$ - see front matter © 2010 Elsevier Inc. All rights reserved. doi:10.1016/j.amjsurg.2009.02.004

as EA either in the emergency room or at final discharge. Informed consent was sought from all patients, and the hospital institutional review board granted approval. A structured retrospective chart was completed by 2 authors to share their experiences (SO and KG). Data were collected on a prepared structured sheet and compiled in an electronic database (Microsoft Excel for Windows; Microsoft, Corp, Redmond, WA), and the mean values for numeric items were calculated and the data evaluated.Tables 1and2show the characteristics of the presented cases in numeric order. All patients were examined by an emergency physician and the first author. Total abdominal ultrasound (USG) was the first imaging method in all, and 10 patients were further evaluated by abdominal CT scans. The CT scans were performed on a General Electric helical scanner using 8-mm thick slices, with a pitch of 1.5-mm and 5-mm image spac-ing. Operations were performed by the same surgical team (SO, NO, HYU, SL, and AK). The senior attending sur-geon’s specific notes on the examination of significant symptoms such as anorexia, nausea, duration of pain, ten-derness, and rebound were collected. Laboratory results including imaging techniques such as abdominal CT scans and USG reports were also studied. The operation notes of surgery were also collected and examined in detail. With regard to the recurrence of EA, all patients were checked 1 month later after hospital discharge; in addition to this, the patients in the nonoperative group were followed-up for an average of 28 months (range 8 – 49 months).

Results

Patients presented at the hospital between 1 and 10 days after the initial symptoms had arisen. Most patients (n⫽ 10) had dull, constant pain either in the right (n ⫽ 3 patients, 30%) or left lower quadrant (n⫽ 7 patients, 70%). Most of them (n⫽ 10) denied complaints such as anorexia, nausea, vomiting, diarrhea, hematochezia, melena, fever, chills, and sweats. In addition, 1 patient had recurrent urinary tract symptoms. Two patients had general abdominal pain with nausea and vomiting and noted that they had not had defe-cated for the last 10 days (patient 4) and 2 days (patient 5). On physical examination, no pathologic abdominal mass was found except for the woman with a 29-week gestation (patient 1) and for patients 4 and 5 who had abdominal distention (Table 1). Bowel sounds of all patients were normal in auscultation except for 2 patients with hypoactive bowel movements (patients 4 and 5). Rectal examinations of the patients were all unremarkable. Laboratory test values including whole blood count, urine samples, and biochem-istry panel were normal except for 4 patients who were found to have leukocytosis (patients 1, 5, 7, and 12) (Tables 1and2). Most of the patients had tenderness in either the right or left lower quadrant. In addition, 3 patients were found to have rebound and muscular rigidity at physical

examination and, eventually, underwent surgery (Table 1). Table

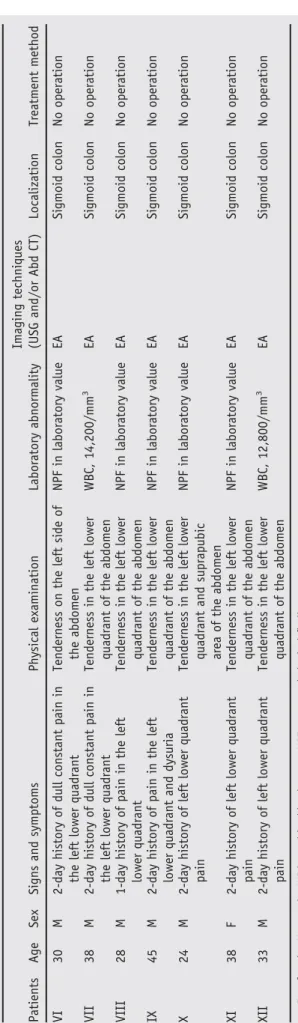

1 Demographic data, physical examination, laboratory test abnormality and radiologic reports of patients who underwent surgery Patients Age Sex Signs and symptoms Physical examination Laboratory abnormality Imaging techniques (USG and/or Abd CT) Localization Treatment method I 29 F 2-day history of dull constant pain in the right lower quadrant Rebound-tenderness localized muscular rigidity on the right side of the abdomen WBC, 15,500/mm 3 Normal USG findings Abd CT was not applicated Cecum Laparotomy II 37 M 3-day history of pain which became violent in the right lower quadrant Rebound-tenderness, localized muscular rigidity on the right side of abdomen NPF in laboratory value Pelvic USG; free fluid around cecum and noncompressive acute appendicitis with a 8-mm diameter. Abd CT was not used Cecum Laparotomy III 18 M 18-hour history of right lower pain radiating to the back Rebound-tenderness, on the right side and suprapubic area NPF in laboratory value NPF in USG and Abd CT Sigmoid colon Laparoscopy IV 78 F 10-day history of abdominal pain, nausea, vomiting, and constipation Tenderness and distention in abdomen, hypoactive bowel sound NPF in laboratory value Ileus in Abd CT Sigmoid colon Laparotomy V 82 M 2-day history of abdominal pain, nausea, vomiting, and constipation Tenderness and distention in abdomen, hypoactive bowel sound WBC, 20,500/mm 3 NPF in USG and ileus in Abd CT Sigmoid colon Laparotomy F ⫽ female; M ⫽ male; WBC ⫽ white blood count; NPF ⫽ no pathological finding.

Patients were further evaluated by transabdominal USG (n⫽ 12) and abdominal CT scan (n ⫽ 10). Unfortunately, abdominal CT scans could not been used for 2 patients because of their medical conditions: one was pregnant (pa-tient 1) and the other was suspected of having perforated acute appendicitis vermiformis (patient 2) by ultrasonogra-phy. Pathognomonic findings of fat density lesions sur-rounded by inflammatory changes for EA were observed by CT scans in 7 patients (Fig. 1).

Five patients required surgical intervention for the diag-nosis and management of an acute abdomen (Table 1). Laparotomy (n ⫽ 4) and diagnostic laparoscopy (n ⫽ 1) were performed. Small right paramedian incisions were made for the first and second patients with suspected acute appendicitis (Table 1). In these cases, abdominal explora-tion revealed a gangrenous EA adjacent to the cecum. In addition, the second patient had an abscess formation in the pelvic and right paracolic region secondary to EA. During surgery on these patients, the inflamed EA was totally re-moved, and an appendectomy procedure was also per-formed. The 3rd patient with suspected acute appendicitis underwent diagnostic laparoscopy, and a gangrenous EA adjacent to the sigmoid colon was observed at the same time (Fig. 2). The gangrenous EA was removed by using an ultrasonically activated scalpel during laparoscopy, and ap-pendectomy was also included. The 4th patient had ileus for 10 days and underwent diagnostic laparotomy. During ex-ploration, a segment of small bowel with an EA of the sigmoid colon was found to be incarcerated together into the femoral hernia sac, and a small intestine dilatation proximal to the obstruction was observed (Fig. 3). EA was removed, and the femoral hernia was repaired. The 5th patient had

Figure 1 A CT image showing EA 2 cm in diameter and peripheral hyperattenuated ring with associated inflammation of the mesentery adjacent to sigmoid colon (Light Speed Ultra, 8 Slice Computer Tomography, General Electric).

Table 2 Demographic data, physical examination, laboratory test abnormality, and radiologic reports of patients who did not undergo surgery and were treat ed conservatively Patients Age Sex Signs and symptoms Physical examination Laboratory abnormality Imaging techniques (USG and/or Abd CT) Localization Treatment method VI 30 M 2-day history of dull constant pain in the left lower quadrant Tenderness on the left side of the abdomen NPF in laboratory value EA Sigmoid colon No operation VII 38 M 2-day history of dull constant pain in the left lower quadrant Tenderness in the left lower quadrant of the abdomen WBC, 14,200/mm 3 EA Sigmoid colon No operation VIII 28 M 1-day history of pain in the left lower quadrant Tenderness in the left lower quadrant of the abdomen NPF in laboratory value EA Sigmoid colon No operation IX 45 M 2-day history of pain in the left lower quadrant and dysuria Tenderness in the left lower quadrant of the abdomen NPF in laboratory value EA Sigmoid colon No operation X 24 M 2-day history of left lower quadrant pain Tenderness in the left lower quadrant and suprapubic area of the abdomen NPF in laboratory value EA Sigmoid colon No operation XI 38 F 2-day history of left lower quadrant pain Tenderness in the left lower quadrant of the abdomen NPF in laboratory value EA Sigmoid colon No operation XII 33 M 2-day history of left lower quadrant pain Tenderness in the left lower quadrant of the abdomen WBC, 12,800/mm 3 EA Sigmoid colon No operation F ⫽ female; M ⫽ male; WBC ⫽ white blood count; NPF ⫽ no pathological finding.

ileus for 2 days and underwent laparotomy. A segment of small bowel attached to EA of the sigmoid colon had caused the obstruction of the small intestine. Patients’ pathologic specimens were sent for histopathological examination with the following results: a congested hemorrhagic and partly necrotic adipose tissue, consistent with the clinical diagno-sis of strangulated appendix epiploica. Abdominal USG and/or CT scans were not supportive of the diagnosis of EA in the patients who underwent surgery because of their abnormal physical examination findings such as rebound, localized tenderness (n⫽ 3) and abdominal distention (n ⫽ 2). The remainder of the patients were fortunate to be

diag-nosed with EA because they revealed the pathognomonic CT findings of fat density lesions surrounded by inflamma-tory changes (Fig. 1). Beneficially, they were all treated conservatively (hydration, pain control, and/or antibiotics) (Table 2). Four patients were followed up in an outpatient clinic without any complications (patients 7, 9, 11, and 12). One patient (patient 10) was discharged from the hospital without any complications on the 3rd day of her hospital stay. The remaining patients (patients 6 and 7) were dis-charged on the 6th day of their hospital stay because they had subjective complaints of abdominal discomfort and required close follow-up. All patients recovered within 3 weeks, and no recurrences were encountered during the 1-month follow-up. The patients in the nonoperative group were followed up for an average 28-month period (range 8 – 49). No recurrence was occurred (Fig. 4).

Comments

EA was first anatomically described by Vesalius in 1543, but their surgical significance was not realized until 1843 when Virchow suggested that their detachment might be a source of free intraperitoneal loose body.5,6EA is typically .5 to 5-cm long and 1 cm to 2 cm thick and has no known function. The total number is approximately 100 and gen-erally located along the sigmoid colon (57%) and ileocecum (26%).7–9Our study at this point showed that the sigmoid colon appears to be the most frequent localization for EA (83%).

Figure 2 A laparoscopic view of a gangrenous appendix epip-loica on the surface of the sigmoid colon.

Figure 3 A CT image of a segment of small bowel with EA in the femoral canal. FA, femoral artery; DSI, dilated small intestinal segment.

Figure 4 We recommend this algorithm for patients with sus-pected EA.

Primary EA is considered an unusual surgical condition, and the actual prevalence is unknown because most are self-limiting cases.10 Detached epiploic appendages are thought to be the most common source of intra-abdominal loose bodies, often found incidentally in the pelvis during laparotomy.11One series that included 15 patients was col-lected over 9 years.12 We have collected 12 cases of EA within 6 years. In the past, EA was diagnosed during lapa-rotomy; however, more recently, the diagnosis is more fre-quent with using CT scans and USG to exclude diverticular disease (2%–7%) and appendicitis (1%).13,14

EA was first reported as the inflammatory result of these appendages.15Thomas et al1classified the etiology of EA as torsion and inflammation (73%), hernia incarceration (18%), intestinal obstruction (8%), and intraperitoneal loose body (⬍1%). The venous component of the appendage is affected first because each appendage is supplied by paired arteries but drained by only 1 vein.16Other suspected causes of EA are lymphoid hyperplasia and bacterial invasion sec-ondary to diverticulitis.6,16

EA can occur at any age and has a wide range (12– 82 years) with a peak incidence in the 4th and 5th decades, and men seem to be slightly more affected than women.2,17In

our study, the mean age was 40 years, and male predomi-nance was observed. In contrast to our cases, 1 study has implied that EA occurs more commonly in obese people, especially in those with a rapid recent weight loss and who had done strenuous exercise.18

Localized nonmigratory pain without vomiting, fever, or toxicity specific for EA has been reported to be generally less than 1-week old and usually involves the right lower quadrant.19,20 However, conflicting data were reported by the studies of Legome et al21 and Levret et al22 in which

73% and 83% of patients presented with left lower quadrant pain, respectively. In our case series, 58% of patients pre-sented with left lower quadrant pain, and 2 patients had nausea and vomiting.

In search of an accurate diagnosis, USG examination might be helpful and could show nonspecific images such as an oval noncompressible hyperechoic mass with a subtle hypoechoic rim directly under the site of tenderness with no color Doppler flow.23 Pathognomonic CT appearances of EA are reported to be 1- to 4-cm oval-shaped, fat density lesions with an enhancing rim adjacent to the colon, thick-ened visceral peritoneal lining, and periappendageal fat stranding.16,24Despite these imagining techniques,

errone-ous diagnosis is still common, and misdiagnosis usually leads to operative intervention as we and some other series have reported.12 We were fortunate that 7 of our patients

revealed pathognomonic USG and CT findings of EA, and, thus, unnecessary surgical intervention was avoided. Two patients did not undergo CT examination because one was pregnant and the other was misdiagnosed with perforated acute appendicitis by using USG preoperatively. In our study, USG revealed highly possible diagnosis of EA in 7 out of 12 (58%), which was confirmed by CT scan in 7 out

of 10 (70%). It is not easy to claim the diagnosis of EA through USG, and CT examinations are usually necessary to confirm the diagnosis.

Our first impression was acute appendicitis in the first patient and perforated appendicitis in the second. We pre-sumed a colon cancer before the operation in the 4th patient but observed that her ileus was caused by an EA of the sigmoid colon together with part of the small bowel incar-cerated into a femoral hernia sac (Fig. 3). The 5th patient had small bowel obstruction because of peritoneal adhesion because of EA. Occasionally, EA results in peritoneal ad-hesions, leading to bowel obstruction and is involved in lipomatosis or sometimes reveals itself as a paracolic mass or incarceration within an incisional or inguinal hernia or abdominal abscess formation.3,25–29

Colonic bacteria have shown to be obtained from tortured appendages and are reported to be responsible for localized abscess formation and generalized peritonitis.29This is comparable to one of

our patients (patient 2) who had localized abscess formation around the cecum and pelvic region.

In the past, the standard therapy for EA was surgical excision because most cases were discovered during surgery for suspected abdominal emergency pathology.11,21,30Some authors have reported that pain recurred or persisted until the EA was removed in 25% to 40% of their cases, and they strongly recommended excision of EA when diagnosed.2,31 Some authors recommend excising of EA during laparos-copy.32In our series, 5 out of 12 patients required surgery; only 1 of them underwent diagnostic laparoscopy for en-lightenment of acute abdomen and 4 have had a laparotomy. We had to operate on 3 patients via laparotomy for the following reasons: 1 was 29 weeks pregnant (patient 1), 1 was diagnosed with perforated acute appendicitis with ab-scess formation in the right paracolic region preoperatively (patient 2), and the last 2 had ileus (patients 4 and 5). Some authors favor the appendectomy procedure to prevent future confusion if recurrent right iliac fossa pain recurs.11In our group of patients who had surgery, only 3 had an appen-dectomy to prevent future disturbances. The last 2 patients in whom we did not perform appendectomy were the 79-and 82-year-old patients. We would also like to mention that this is the first report in the English literature to present 2 special cases of EA causing an acute abdomen: in a preg-nant woman (patient 1) and in the patient with ileus caused by EA of the sigmoid colon incarcerated in femoral hernia sac with small bowel segment (patient 4).

Although nonsurgical management of EA was hypothe-sized by Epstein and Lempke33in 1968, it was not reported until 1992.34We treated 7 out of 12 patients with conser-vative therapy and succeeded in overcoming the symptoms, which resolved within approximately 3 weeks. With con-servative management, patients’ symptoms mostly alleviate between 1 weeks and 4 weeks.4,23,35,36 In our study, no recurrence was observed during the mean follow-up of 28 months (range 8 – 49 months). If a patient is suspected of

having EA, the algorithm for the diagnosis and treatment could be followed (Fig. 4).

Conclusions

Diagnosis and treatment of EA is still a challenge for surgeons because of its nonspecific signs and symptoms. However, the increasing use of abdominal CT scans in the diagnosis of abdominal pain is leading clinicians to become more familiar with this disease. Finally, we suggest that when combined with appropriate imaging techniques, EA patients with a consistent clinical history and physical ex-amination have the opportunity to be managed conserva-tively.

References

1. Thomas JH, Rosato FE, Patterson LT. Epiploic appendagitis. Surg Gynecol Obstet 1974;138:23–5.

2. Sand M, Gelos M, Bechara FG, et al. Epiploic appendagitis— clinical characteristics of an uncommon surgical diagnosis. BMC Surg 2007; 7:11.

3. Singh AK, Gervais D, Rhea J, et al. Acute epiploic appendagitis in hernia sac: CT appearance. Emerg Radiol 2005;11:226 –7.

4. Lien WC, Lai TI, Lin GS, et al. Epiploic appendagitis mimicking acute cholecystitis. Am J Emerg Med 2004;22:507– 8.

5. De Vesalius A. Humanis corporis fabricia libri septem.. In: Basileae, ed. Andreae vesalii bruxellensis, scholae medicorum patauiniae pro-fessoris de humani corporis fabricia libri septem. Basel, Switzerland: Ex officina Joannis Oporini; 1543.

6. Vinson DR. Epiploic appendagitis: a new diagnosis for the emer-gency physician. Two case reports and a review. J Emerg Med 1999;17:827–32.

7. Legome EL, Sims C, Rao PM. Epiploic appendagitis: adding to the differential of acute abdominal pain. J Emerg Med 1999;17:823– 6. 8. Sangha S, Soto JA, Becker JM, et al. Primary epiploic appendagitis: an

underappreciated diagnosis. A case series and review of the literature. Digest Dis Sci 2004;49:347–50.

9. Hiller N, Berelowitz D, Hadas-Halpern I. Primary epiploic appendagi-tis: clinical and radiological manifestations. Isr Med Assoc J 2000;2: 896 – 8.

10. Rioux M, Langis P. Primary epiploic appendagitis: clinical, US, and CT findings in 14 cases. Radiology 1994;191:5236.

11. Schein M, Rosen A, Decker GA. Acute conditions affecting epiploic appendages. A report of 4 cases. S Afr Med J 1987;71:397– 8. 12. Abadir JS, Cohen AJ, Wilson SE. Accurate diagnosis of infarction of

omentum and appendices epiploicae by computed tomography. Am Surg 2004;70:854 –7.

13. van Breda Vriesman AC, Puylaert JB. Epiploic appendagitis and omental infarction: pitfalls and look-alikes. Abdom Imaging 2002;27: 20 – 8.

14. Zissin R, Hertz M, Osadchy A, et al. Acute epiploic appendagitis: CT findings in 33 cases. Emerg Radiol 2002;9:262–5.

15. Dockerty MB, Lynn TE, Waugh JM. A clinicopathologic study of the epiploic appendages. Surg Gynecol Obstet 1956;103:423–33. 16. Singh AK, Gervais DA, Hahn PF, et al. Acute epiploic appendagitis

and its mimics. Radiographics 2005;25:1521–34.

17. Jain TP, Shah T, Juneja S, et al. Case of the season: primary epiploic appendagitis: radiological diagnosis can avoid surgery. Semin Roent-genol 2008;43:4 – 6.

18. Molla E, Ripolles T, Martinez MJ, et al. Primary epiploic appendagitis: US and CT findings. Eur Radiol 1998;8:435– 8.

19. Son HJ, Lee SJ, Lee JH, et al. Clinical diagnosis of primary epiploic appendagitis: differentiation from acute diverticulitis. J Clin Gastro-enterol 2002;34:435– 8.

20. Vlahakis E. Torsion of an appendix epiploica of the ascending colon. Med J Aust 1973;2:1148 –9.

21. Legome EL, Belton AL, Murray RE, et al. Epiploic appendagitis: the emergency department presentation. J Emerg Med 2002;22:9 –13. 22. Levret N, Mokred K, Quevedo E, et al. [Primary epiploic

appendici-tis]. J Radiol 1998;79:667–71.

23. Boulanger BR, Barnes S, Bernard AC. Epiploic appendagitis: an emerging diagnosis for general surgeons. Am Surg 2002;68:1022–5. 24. Danielson K, Chernin MM, Amberg JR, et al. Epiploic appendicitis:

CT characteristics. J Comput Assist Tomogr 1986;10:142–3. 25. Talukdar R, Saikia N, Mazumder S, et al. Epiploic appendagitis: report

of two cases. Surg Today 2007;37:150 –3.

26. Kulacoglu H, Tumer H, Aktimur R, et al. Epiploic appendicitis in inguinal hernia sac presenting an inguinal mass. Hernia 2005;9: 288 –90.

27. Ghahremani GG, White EM, Hoff FL, et al. Appendices epiploicae of the colon: radiologic and pathologic features. Radiographics 1992;12: 59 –77.

28. Ozkurt H, Karatag O, Karaarslan E, et al. Clinical and CT findings of epiploic appendagitis within an inguinal hernia. Diagn Interv Radiol 2007;13:23–5.

29. Romaniuk CS, Simpkins KC. Case report: pericolic abscess secondary to torsion of an appendix epiploica. Clin Radiol 1993;47:216 –7. 30. Bundred NJ, Clason A, Eremin O. Torsion of an appendix epiploica of

the small bowel. Br J Clin Pract 1986;40:387.

31. Bernard M, Jaffe DH. Berger. Epiploic appendagitis. In: Brunicardi FC, editor. The Appendix. 8th ed. Schwartz’s Principles of Surgery. McGraw-Hill New York; 2007. p. 1127.

32. Vazquez-Frias JA, Castaneda P, Valencia S, et al. Laparoscopic diag-nosis and treatment of an acute epiploic appendagitis with torsion and necrosis causing an acute abdomen. JSLS 2000;4:247–50.

33. Epstein LI, Lempke RE. Primary idiopathic segmental infarction of the greater omentum: case report and collective review of the literature. Ann Surg 1968;167:437– 43.

34. Puylaert JB. Right-sided segmental infarction of the omentum: clini-cal, US, and CT findings. Radiology 1992;185:16972.

35. Tutar NU, Ozgul E, Oguz D, et al. An uncommon cause of acute abdomen— epiploic appendagitis: CT findings. Turk J Gastroenterol 2007;18:107–10.

36. Pavone E, Mehta SN, Trudel J, et al. Torsion of an appendix epiploica: a nonsurgical cause of acute abdomen. Digest Dis Sci 1997;42:851–2.