The Impact of a Nursing Coping Kit and a Nursing Coping Bouncy Castle

on the Medical Fear Levels of Uzbek Refugee Children

Emel Teksoz

a,⁎

, Vesile Düzgüner

b, Ibrahim Bilgin

c, Ayse Ferda Ocakci

d,ea

Health School of Mustafa Kemal University, Hatay, Turkey

bSchool of Health Sciences of Ardahan University, Ardahan, Turkey c

Education Faculty of Mustafa Kemal University, Hatay, Turkey

d

School of Nursing, Koc University, Istanbul, Turkey

eGüzelbahçe sok. Nişantaşı, İstanbul, Turkey

a b s t r a c t

a r t i c l e i n f o

Article history: Received 17 May 2017 Revised 9 January 2018 Accepted 10 January 2018Purpose: This study determines the effect of a nursing coping kit and a nursing coping bouncy castle on the self-reported medical fear levels of Uzbek refugee children.

Design and Methods: The study was conducted with Uzbek refugee children (n = 70) aged 6 to 18 years from Hatay province of Turkey. The children were randomly assigned into 2 groups; an experimental group (n = 35) and a control group (n = 35). Two coping interventions were tested; a nursing coping kit and a nursing coping bouncy castle. These were designed to present medical implements, depictions of healthcare staff, and medical procedures to the children in a fun and playful way. A socio-demographic questionnaire was completed by all participants prior to the experiment. Also, a Fear for Medical Procedures Scale (FMPS) questionnaire was completed by each participant both prior to and after the intervention sessions with both the coping interven-tions.

Results: The FMPS post-test scores decreased significantly in the experimental group after exposure to the two interventions when compared with the control group (11.77 and 22.14, respectively). Thus, the results support the notion that two coping interventions appear to reduce children’s medical fear level and make healthcare pro-cedures easier to deal with.

Conclusion: The participation of children in creative activities such as making toys or playing with items from the nursing coping kit, and the opportunity for having fun represented by the nursing coping bouncy castle have po-tential benefits for them in terms of developing strategies to cope with their medical fears.

Practical Implications: Using interventions to cope with medical fears of children might be recommended when the normal development process is considered significantly. Nursing researches should attach more importance and perform further studies about the subject.

© 2018 Elsevier Inc. All rights reserved.

Keywords: Medical fear Refugee Nursing Coping Kit Coping Activities

Introduction

Childhood fears are a natural part of children's development and occur in fairly predictable patterns. In infancy and early childhood, fears initially reflect a fear of strangers and separation from parents, and later, focus on fear of the dark and large animals. In time, these fears are gradually replaced by the fear of being alone, kidnappers or medical experiences (Mahat, Scoloveno, & Cannella, 2004;Nicholson & Pearson, 2003). Specifically, medically-focused fears are common in childhood and among these are fear of injections, blood, contact with healthcare professionals, and fear of surgical procedures. Such fears

anxieties can be learnt and remembered from children's prior medical experiences, for example, during routine vaccine injections which may lead to the establishment of a fear of injections. Children's fears related to medical experiences have been extensively researched over the last decade (Heden, Essen, & Ljungman, 2016;Karlsson, Englund, Enskär, Nyström, & Rydström, 2016;Karlsson, Rydström, Nyström, Enskär, & Englund, 2016;Mahat et al., 2004).

Medical fears can be predicted on the basis of demographic factors including age, gender or contextual factors such as culture (Eleonora

Gullone, 2000;Mahat et al., 2004). Commonly reported fears by chil-dren and adolescents typically relate to death and danger, the unknown, school and social stress, as well as medical and situational fears ( Serim-Yildiz & Erdur-Baker, 2013). Culturally-mediated beliefs, values, and traditions play a role in such fears; therefore, children from different cultures may perceive medical experiences differently. At present, the

⁎ Corresponding author: Emel Teksoz.

E-mail addresses:eteksoz@mku.edu.tr(E. Teksoz),vesileduzguner@ardahan.edu.tr

(V. Düzgüner),ibilgin@mku.edu.tr(I. Bilgin),aocakci@ku.edu.tr(A.F. Ocakci).

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pedn.2018.01.010

0882-5963/© 2018 Elsevier Inc. All rights reserved.

Contents lists available atScienceDirect

lack of culturally-focused studies of children's medical fears represents a gap in the research. Therefore, further cultural studies are recommend-ed to better understand the influence of culture on children's medical anxieties (Cole, Bruschi, & Tamang, 2002;Mahat et al., 2004;Mahat & Scoloveno, 2003;Serim-Yildiz & Erdur-Baker, 2013).

Fear is a necessary emotion which serves to make us aware of danger and ready to take action to secure our safety. Such fear is a normal reac-tion which usually decreases with age (Forsner, Jansson, & Söderberg, 2009). However, medically-focused fears can be differentiated from normal fears in several aspects, including whether or not the expressed fear is age- or stage-specific, whether or not it persists over an extended period of time, and/or significantly interferes with everyday functioning (EleonoraGullone, 2000;Heden et al., 2016). As medical fears do not tend to decrease throughout childhood, they have the potential to ad-versely affect medical procedures necessary for children's health and/ or complicate the treatment of childhood diseases (Birnie et al., 2015;

Kunzelmann & Dünninger, 1990). Additionally, these fears may have a negative impact on children's perceptions of healthcare and healthcare professionals. All healthcare professionals, and especially nurses who tend to spend more time with children, play a crucial role in supporting children to cope with their fears. Nurses may act as catalysts for children to learn and develop coping skills (Mahat et al., 2004; Mahat & Scoloveno, 2003). Therefore, it is important that nurses are able to accu-rately assess and intervene in reducing these fears. Nurses can play a pivotal role in alleviating children's fears of medical experiences by pro-viding culturally-sensitive care (Mahat et al., 2004).

Coping strategies to deal with medical fears are well established in the literature, such as coping kits, storytelling, acting, painting, and toys (Caddy, Crawford, & Page, 2012; Drake, Stoneck, Martinez, & Massey, 2012;Wilson, Megel, Enenbach, & Carlson, 2010). Children have various coping strategies which are different from adults'. Children's ability to cope with medically-derived fears is based on their prior experiences. In this way, nurses may apply variegated inter-vention in accordance with the child's experiences of their medical fears. Nurses also need to have an understanding of different cultural practices relevant to the children's background, as these may influence children's fears and coping strategies. Studies that focus on children's fears and coping strategies in the medical context need to be enlarged with more samples from different geographic areas (Mahat & Scoloveno, 2003). Refugee children belong to a vulnerable cohort that has often experienced deprivation, poverty, complicated physical, men-tal and nutritional health issues, and exposure to significant violent and traumatic events. These experiences occur during a critical develop-mental period, this situation will cause them to create fears. Improving educational experiences may assist in these children's resettlement and recovery from trauma (Mace et al., 2014).

In addition gender, education, occupation, income and place of resi-dence are all closely linked to refugee's access and experience of the benefits of healthcare and education. Refugee families face a range of challenges that can affect childrearing practices and are likely to precip-itate fear and anxiety in their offspring. These include their past experi-ences of torture and trauma, changes in family roles, separation from family members and poor access to primary healthcare and education. This means that child refugees tend to have a poor quality of life as a consequence (Riggs et al., 2012; Teodorescu et al., 2012;Zepinic, Bogic, & Priebe, 2012) and identifying and addressing the often-overlooked health needs of refugee children needs to be prioritized in health care visits. Although well-child health care visits are useful in identifying health issues early on, there has been limited investigation into the use of these services for children from refugee backgrounds (Idemudia, Williams, & Wyatt, 2013;Kristiansen, Kessing, Norredam, & Krasnik, 2015;Matanov et al., 2013).

In 1982, the Uzbeks, who were placed in the Ovakent area of Hatay province of Turkey, formed a special traditional life style. They never abandoned their culture and traditions and their relationship with the people of the province where they are established is always limited.

Connections with the people of Hatay are only in thefield of health and education. Children live in an almost semi-isolated community. Some experiences are completely uncertain for them, especially those related to health such as injections and interaction with health profes-sion because they usually do not socialize with natives. The purpose of this study is to investigate the effect of a nursing coping kit and a nurs-ing copnurs-ing bouncy castle on refugee children's medical fears.

Methods Study Design

Health systems researchers use a wide range of quasi-experimental approaches to estimate the causal effects of healthcare interventions (Harris et al., 2006). In medical informatics, the quasi-experimental, sometimes called the pre-post intervention, design often is used to eval-uate the benefits of specific interventions. Quasi-experimental designs identify a comparison group that is as similar as possible to the treat-ment group in terms of baseline (pre-intervention) characteristics. The comparison group captures what would have been the outcomes if the intervention had not been implemented (White & Sabarwal, 2014). These methods are considered to be potent in estimating the strength of causal relationships (Reeves, Wells, & Waddington, 2017). The data were obtained from quasi-experimental study with a pre-and postest after intervention pre-and comparison group (without inter-vention), which gathered survey information from Uzbek refugee child participants living in a small town in the Hatay province. Ovakent is located approximately 20 km from the city centre and is mainly inhabited by an Uzbek refugee population.

The provision of medical treatment and education forms the princi-ple link between Uzbek children and the local native community. In this way, the sample is a more specific cohort for examining medical fears because the Uzbek refugee children share medical experiences with only health personnel as they live separately from the local population.

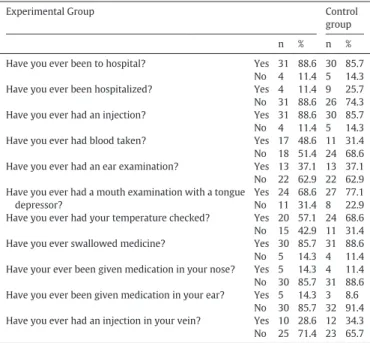

Table 1provides an overview of these children's medical experiences. Therefore, selecting Uzbek refugee children in Hatay as a sample seems to be a convenient method to measure the impact of specific in-terventions on their medically-based fears.

This study uses an appropriate sampling method where all partici-pating children were identified from a pool of volunteers aged 6 to 18

Table 1

Respondent's prior medical experiences questionnaire results.

Experimental Group Control

group n % n % Have you ever been to hospital? Yes 31 88.6 30 85.7

No 4 11.4 5 14.3 Have you ever been hospitalized? Yes 4 11.4 9 25.7 No 31 88.6 26 74.3 Have you ever had an injection? Yes 31 88.6 30 85.7 No 4 11.4 5 14.3 Have you ever had blood taken? Yes 17 48.6 11 31.4 No 18 51.4 24 68.6 Have you ever had an ear examination? Yes 13 37.1 13 37.1 No 22 62.9 22 62.9 Have you ever had a mouth examination with a tongue

depressor?

Yes 24 68.6 27 77.1 No 11 31.4 8 22.9 Have you ever had your temperature checked? Yes 20 57.1 24 68.6 No 15 42.9 11 31.4 Have you ever swallowed medicine? Yes 30 85.7 31 88.6 No 5 14.3 4 11.4 Have your ever been given medication in your nose? Yes 5 14.3 4 11.4 No 30 85.7 31 88.6 Have you ever been given medication in your ear? Yes 5 14.3 3 8.6

No 30 85.7 32 91.4 Have you ever had an injection in your vein? Yes 10 28.6 12 34.3 No 25 71.4 23 65.7

years by nurses on home visits. The complete study contains compara-tive data using a pre-test/post-test design which compares the experi-mental group (i.e. those provided with the nursing coping kit and nursing coping bouncy castle) with a control group who did not receive any intervention.

Children as Participants

The county of Hatay, which is divided into Uzbek refugees, consists of approximately 1500 children and teenagers. Uzbek youths spend most of their time in their own provinces because they have limited in-teractions with local people creating restricted social opportunities. The study was carried out using Uzbek refugee children (n = 70) aged 6 to 18 years with a mean age of 10.39 (SD = 2.63). Percentage of age ranges of participating children are as follows; 6–8 age: 21 person (30%), 9–11 age: 26 person (37.1%), 12–14 age:19 person (27.1%), 15–18 age: 4 person (5.7%).

The children were randomly divided into 2 groups; an experimental group (n = 35) and a control group (n = 35). The children's ability to understand/speak Turkish and being developmentally appropriate for their age were the inclusion criteria used to select suitable participants in home visits. Information about the research was provided to the chil-dren verbally and their parent's permission (verbal and written) was obtained during home visits. The sample consisted of both boys (n = 24) and girls (n = 51).

The children's experiences of contact with medical professionals varied on an individual basis. For instance, some of the members of ex-perimental group had had occasional contact with healthcare profes-sionals, for the administration of medicines orally (85.7%), mouth examination using a tongue depressor (68.6%), fever measurement (57.1%), ear examination (37.1%), and the administration of nasal med-ication (14.3%). For others, their medical experiences had been more se-rious in nature, such as hospitalization (11.4%), having an injection (88.6%), taking of blood samples (48.6%) and intravenous drug adminis-tration (28.6%). Similarly, the control group also had comparable medi-cal experiences (seeTable 1).

Nursing Coping Kit

The nursing coping kit was specifically designed by the researcher to relate to the typical instruments used in medical interventions experi-enced by children. The kit (seeFig. 1) is composed of a tongue depres-sor, 3 × syringes (2cm3, 5cm3, and 20cm3), a mask and toy-making

items (eco-friendly glue, scissors, and small accessories). Nurses

explained how the children should use the kit before each child was given one. The children then decided to make toys or play games with the materials themselves without any interference.

Nursing Coping Bouncy Castle

This consists of an 8 × 5m2sized bouncy castle designed by the

re-searcher. The interior depicts images of objects and people related to medical experiences such injections, nurses, doctors and medication, as well as pictures of fruit, used for fun. It is powered by an electric fan and is used in a playground setting with 10 children up to 50 kg each. The bouncy castle was designed to be suitable for the children to bounce and jump around on (Fig. 2).

Data Collection

A town-center municipal building and garden were reserved for the study. The nursing coping kit was supervised by 2 nurses with 4 chil-dren using to play with or make toys from. In total, 9 desks were avail-able for the 2 nurses and 4 children to use. For the nursing coping bouncy castle, part of the municipal garden was set up as a play area.

In the present study, a socio-demographic questionnaire and the Fear for Medical Procedures Scale (FMPS) were utilized. All data were collected by 20 nurses under the supervision of the researcher. If the children required help, 1 nurse was provided for every 2 children. Fear for Medical Procedures Scale

The Fear for Medical Procedures Scale (FMPS) was developed by Marion Bloom et al. in 1985 to measure the medical-related fears of chil-dren (Alak, 2010). The FMPS's face validity and reliability were investi-gated byAlak (2010)who assessed that its reliability coefficient was α = 0.93 using the Cronbach alpha measure. Thus, its high level of validity and reliability means that it is an adequate measurement to determine the levels of medical fears in the children. This Likert-type tool is com-prised of 29 items relating to medical fears and 4 sub-groups about op-erational, environmental, personal and interpersonal fears. Children were asked to rate themselves for each item on a 3-point Likert-type scale (1 = no fear, 2 = some fear and 3 = much fear). Scores between 0 and 29 represent no fear, 29–58 some fear and 58–87 much fear. For each child, a total score was calculated with a range from 29 to 87. Demographic Questionnaire

A questionnaire was used to obtain demographic data. The items in-cluded name, surname, gender, age, number of siblings, education level of parents, and parent's occupation(s) (19 items). Demographic

Fig. 1. The Nursing Coping Kit.

Questionnaire was conducted during home visits, when all family mem-bers were present together. When the child did not know the answer, the father/mother replied instead of the child.

Procedure

During thefieldwork, the nurses made home visits and did not per-form interventions with the experimental/control groups. Intervention was performed with the experiment group in an especially designed sa-loon in the municipality of Ovakent. The control group was not present in this building while the game was being played by the experimental group to avoid the contact between groups. During the intervention, the interactions between the experimental and control groups were avoided.

After the children and parents had been given information about the study's aims the children were asked again whether they wanted to join the intervention. Verbal consent was taken again from their families. Then they were invited to the municipal area. Firstly, the children in the randomly selected control group were given a socio-demographic questionnaire and an FMPS pretest. The FMPS re-tests were then given again after 4 h. After the control group had completed the coping interventions, the experimental group was given the socio-demographic questionnaire and FMPS pretest. Then the children in the experimental condition group were invited to play or to make toys with the nursing coping kit at their desks. At the same time, the exper-imental group played on the nursing coping bouncy castle for approxi-mately 10–15 min. Finally, the experimental group children were invited to complete the FMPS post-test after the intervention. This pro-cess took 4 h to complete.

Data Analysis

The data from the FMPS were entered and analyzed using SPSS 13 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA). The independent t-test results were exam-ined in order to determine any changes in the children's medical fears before and after the interventions. The alpha level of significance was set at .05.

Ethical Considerations

The study was conducted using the Helsinki criteria. Initially, per-mission was obtained from the governor of the Hatay province to com-plete the study in this district of Hatay. Verbal and written informed

consent forms were collected from the children and parents. Ethical ap-proval for this study was obtained from the Mustafa Kemal University Ethics Committee. In addition, written and verbal permission has been obtained for the participation of the children from the parents as well as written and verbal approval from the children themselves.

Results

Seventy refugee children aged 6–18 participated in the study. Their self-reported fears were analyzed by group (control vs. experimental) using an independent t-test. The total fear scores of the experimental group children as measured by the pre-test was a mean average of 24.17 (SD = 12.54) and the total fear score of the control group was a mean average of 24.74 (SD = 13.87). There was no significant differ-ence in the pre-test fear scores between experimental and control group children (t [1, 70] =−0.181, P N .05). In the post-test phase, the mean average of the experimental group's post-test fear score was 11.77 (SD = 7.2), while the mean average of the control group's fear score was 22.14 (SD = 13.71). This result showed that there was a sig-nificant difference between the experimental group's self-reported fears and the control group's scores (t [1, 70] =−3.972, P b .00). In

Table 2, the frequency, mean, and standard deviation of fears reported by the experimental and control groups are presented.

InTable 3, the FMPS post-test scores of the experimental and control group are presented according to specific sub-groups as explained next. The experimental group's pre-intervention mean fear score was 1.85 (SD = 1.84) while that of the control group's was 6.11 (SD = 5.32). The experimental group's mean environmental fear score was 3.71 (SD = 3.07) and the control group's was 7.51 (SD = 4.79). There were significant differences in the post-test sub-groups pre-intervention fear score (t [1, 70] =−4.52, P b .00) and post-test sub-groups environ-mental fear score (t [1, 70] =−3.95, P b .00) between the experimental and control groups. In addition, the result showed no significant differ-ences between the post-test sub group's personal fear score (t [1, 70] = −1.88, P N .05) and inter-personal fear score (t [1, 70] = −1.81, P N .05) between the experimental and control groups. However, the mean scores of the experimental group were lower than control groups.

The experimental group's fears were analyzed by gender (Table 4). The mean average of total-fear pre-test scores for girls in the experi-mental group was 27.32 (SD = 12.21), while that of the boys was 18.35 (SD = 11.65). This result shows that there are no significant dif-ferences between the experimental group's self-reported fears by gen-der (t [1, 35] = 2.016, PN .05). In the experimental group, the total fear post-test mean average for girls was 12.41 (SD = 7.32), and for boys was 10.59 (SD = 6.91). The result showed no significant differ-ences between the experimental group's self-reported fears by gender (t [1, 3 5] = .684, PN .05), although the mean scores for the boys were lower than the girls'. The control group's fears were analyzed by gender

Table 2

Medical procedures fear tool pre- and post-test scores for the experimental and control groups.

Variants Groups n Mean SD t df P Pre-FMPS Experimental group 35 24.17 12.54 −.181 68 .857

Control group 35 24.74 13.87

Post-FMPS Experimental group 35 11.77 7.12 −3.972 68 .000* Control group 35 22.14 13.71

Table 3

Medical procedures fear tool post-test sub-group scores for the experimental and control groups.

Variant Group n Mean SD t df P Preoperative Experimental group 35 1.85 1.84 −4.52 68 .000*

Control group 35 6.11 5.32

Environmental Experimental group 35 3.71 3.07 −3.95 68 .000* Control group 35 7.51 4.79

Personal Experimental group 35 2.14 1.54 −1.88 68 .064 Control group 35 2.97 2.11

Interpersonal Experimental group 35 4.77 4.76 −1.81 68 .074 Control group 35 6.77 4.44

Table 4

Experimental group's pre- and post-test scores by sex.

Variant Groups n X SD t df P Pre-FMPS Girl 22 27.32 12.21 2.016 33 .052 Boy 13 18.35 11.65 Post-FMPS Girl 22 12.41 7.32 .684 33 .499 Boy 13 10.59 6.91 Table 5

Control group's pre- and post-test scores by sex.

Variant Groups n Mean SD t df P Pre-FMPS Girl 19 25.16 16.23 .190 33 .850

Boy 16 24.25 10.93

Post-FMPS Girl 19 22.74 15.57 .275 33 .785 Boy 16 21.44 11.5

(Table 5). Although, the mean scores for the boys were lower than that of the girls', no statistically significant differences were found between the pre-test fear scores of the control group (t [1, 35] = .190, PN .05) and their post-test fear scores (t [1, 35] = .275, PN .05) (seeTable 5).

Discussion

Fear is a normal reaction to a real or imagined threat that poses a risk to a person's well-being. Fear seems to differ according to age, and the research suggests that fear and anxiety are more common in children than in adults (E.Gullone, King, & Ollendick, 2001). Fear relating to medical interactions is an important issue for both children and healthcare professionals. However, it isfirst and foremost a subjective experience. For the children of immigrants, poverty, the stresses of mi-gration, and the challenges of acculturation can substantially increase their risk for the development of physical and mental health problems. Because migration exposes children to unique developmental demands and stressors associated with acculturation, it reshapes their normative development. To adapt, immigrant children and their families choose different combinations of acculturation and enculturation strategies (Perreira & Ornelas, 2011). Uzbek refugees were deployed 20 years ago in Hatay province. But instead of adapting, they continued their cul-ture for generations. The strategy of Uzbek refugees in Hatay were not to change their traditions and cultures. They interact with the new envi-ronment only to the extent they need it.

A recent study demonstrated that Uzbek refugee children were found to experience fear relating to medical procedures such as injec-tions, taking blood, ear and/or throat examination, and hospitalization. The studies suggest that fear of contact with healthcare professionals re-mains commonplace among children as they grow and develop (Heden et al., 2016;Karlsson, Englund, et al., 2016;Karlsson, Rydström, et al., 2016;Mahat et al., 2004;Mahat & Scoloveno, 2003).

The present study's results suggest that the nursing coping kit and the nursing coping bouncy castle both decreased fear levels in the refu-gee children experimental group. Thisfinding concurs withMarasuna and Eroglu (2013)report that positive patient–nurse interactions, and providing explanations of medical procedures to child patients before-hand, tend to reduce their fear levels. Children's ability to cope with their medical fears is based on their prior experiences. Therefore, expo-sure of child patients to the nursing coping kit and the nursing coping bouncy castle prior to medical treatment seems to be effective in reduc-ing such fears.

The materials used in the nursing coping kit and the nursing cop-ing bouncy castle were related to medical experiences such injec-tions, nurses, doctors and medication, masks, syringes, and tongue depressors. The reason for the success of these coping interventions seems to be that they were able to change the hospital environment from one feared by the children to one where they were able to have fun through creative and active play. To overcome the experiences and fears of health practices of children in this refugee community, which is isolated at this level, to hopefully approach future hospital experiences with less fear. Also children with a limited medical ex-perience will forget about their frightening by making toys with medical materials.

The nursing coping kit provided a potent effect on reducing children's self-reported medical fears and would be useful in pre-operative applications as it encouraged children to develop better-coping strategies.Bloch and Toker (2008)indicate that by initiating a controlled pain-free encounter with the medical environment in the form of a“Teddy Bear Hospital,” they can reduce children's fear levels. They conducted medical procedures including physical examinations, various laboratory and diagnostic tests which determined that it is pos-sible to combine coping activities and professional knowledge tofind a way for children to overcome their fear. Also, it can be beneficial for par-ents to join their child/children in such activities (Birnie et al., 2015;

Forsner et al., 2009;Li, Yu, Yang, & Chang, 2014;Simons, Kaczynski, Conroy, & Logan, 2012;William & Lopez, 2008).

Although the present study found no significant gender-based dif-ferences between boy's and girl's self-reported medical fear levels in the Uzbek child refugee sample, it is known that medical fears in chil-dren are affected most by variables such gender, age, socioeconomic sta-tus, and culture.Serim-Yildiz and Erdur-Baker (2013)reported that 8-year old girls from poor socioeconomic backgrounds revealed the highest fear scores for all fear factors, while the lowest fear scores were disclosed by male adolescents from varied socioeconomic back-grounds. The outward appearance of Uzbek culture, the traditions of conservatism and beliefs could possibly be triggering fears of children. Similarly, other studies report that children's and adolescent's fear levels may vary according to their culture of origin (Cole et al., 2002;

Mahat et al., 2004; Mahat & Scoloveno, 2003; Svensson, Ramírez, Peres, Barnett, & Claudio, 2012). Ultimately, the research overwhelm-ingly emphasizes that young females experience higher fear levels than young males.

Implications for Practice

Every child will undergo medical interventions of varying types and multiple times in their lives. Encouraging and facilitating healthcare professionals, such as nurses to provide intervention activities with chil-dren that not only help them to overcome their prior medical fears but also support the development of children's coping skills in relation to necessary future medical procedures. It would be beneficial if healthcare professionals could undertake outreach programmes (i.e. outside of the traditional medical settings of hospitals and clinics) such as using the nursing coping kit and nursing coping bouncy castle in order to enable children to build more robust coping strategies in relation to their med-ical fears.

Limitations of Study

Thefindings of the study cover the 6–18 year old Afghan children. It is not generalizable to other refugee children, but can be used as prelim-inary data for studies to be carried out in other groups. Also due to the specific criteria of the study, it was necessary to study with small sample size. In future studies it may be advisable to work with more numbers in different age groups.

Conclusion

Children's perceptions of the medical environment and healthcare professionals play an important role in determining their level of fear of medical experiences. High levels of such fears can present problems for the effective examination and treatment of children. In this study, the Uzbek refugee children's self-reported fear of medical experiences was reduced after using the nursing coping kit and the nursing-coping bouncy castle. Therefore, these methods represent an effective approach to the alleviation of medical-based fears and seem to encourage chil-dren to develop better coping strategies with which to overcome their medical fears. Thefindings are a suggestion for future studies and it is recommended that future research should investigate this approach further, perhaps assessing alternative play-based methods such as role play.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the children and nurses who partic-ipated in this study. Also, special thanks to the staff at the Ovakent Mu-nicipality. The authors have no conflicts of interest. This study was supported by the Social Support Program (SODES) funded by the East-ern Mediterranean Development Agency (DOĞAKA) coordinated by the Ministry of Development of Turkey (2013-31-0094).

References

Alak, V. (2010).Fears of 7-14 yeared children who admitted to hospital for operation and nursing applications. Ege Universty Journal of Nursing School, 26, 288.

Birnie, K. A., Chambers, C. T., Taddio, A., McMurtry, M., Noel, M., Riddell, R. P., & Shah, V. (2015). Psychological interventions for vaccine injections in children and adolescents systematic review of randomized and quasi-randomized controlled trials. The Clinical Journal of Pain, 31(10), 72–89.https://doi.org/10.1097/AJP.0000000000000265. Bloch, Y. H., & Toker, A. (2008).Doctor, is my teddy bear okay? The“teddy bear hospital”

as a method to reduce children's fear of hospitalization. The Israel Medical Association Journal, 10, 597–599.

Caddy, L., Crawford, F., & Page, A. (2012).‘Painting a path to wellness’: Correlations be-tween participating in a creative activity group and improved measured mental health outcome. Journal of Psychiatric and Mental Health Nursing, 19(4), 327–333.

https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2850.2011.01785.x.

Cole, P. M., Bruschi, C. J., & Tamang, B. L. (2002). Cultural differences in Children's emo-tional reactions to difficult situations. Child Development, 73(3), 983–996.https:// doi.org/10.1111/1467-8624.00451.

Drake, J., Stoneck, A. V., Martinez, D. M., & Massey, M. (2012).Children's Hospital of Wis-consin. 2012. Evaluation of a coping kit of items to support children with develop-mental disorders in the hospital setting. Pediatric Nursing, 38(4), 215–221.

Forsner, M., Jansson, L., & Söderberg, A. (2009). Afraid of medical care: School-aged children's narratives about medical fear. Journal of Pediatric Nursing, 24(6), 519–528.https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pedn.2009.08.003.

Gullone, E. (2000). The development of normal fear: A century of research. Clinical Psychology Review, 20(4), 429–451. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0272-7358(99)00034-3.

Gullone, E., King, N. J., & Ollendick, T. H. (2001).Self-reported anxiety in children and ad-olescents: A three-year follow-up study. Journal of Genetic Psychology, 162(1), 5–19.

Harris, A. D., McGregor, J. C., Perencevich, E. N., Furuno, J. P., Zhu, J., Peterson, D. E., & Finkelstein, J. (2006).The use and interpretation of quasi-experimental studies in medical informatics. Journal of the American Medical Informatics Association, 13, 16–23.

Heden, L., Essen, L. V., & Ljungman, G. (2016). The relationship between fear and pain levels during needle procedures in children from the parents' perspective. European Journal of Pain, 20, 223–230.https://doi.org/10.1002/ejp.711.

Idemudia, E. S., Williams, J. K., & Wyatt, G. E. (2013).Migration challenges among Zimbabwean refugees before, during and post arrival in South Africa. J Inj Violence Res., 5(1), 17–27.

Karlsson, K., Englund, A. -C. D., Enskär, K., Nyström, M., & Rydström, I. (2016). Experienc-ing support durExperienc-ing needle-related medical procedures: A hermeneutic study with young children (3–7 years). Journal of Pediatric Nursing, 31, 667–677.https://doi. org/10.1016/j.pedn.2016.06.004.

Karlsson, K., Rydström, I., Nyström, M., Enskär, K., & Englund, A. -C. D. (2016). Conse-quences of needle-related medical procedures: A hermeneutic study with young chil-dren (3–7 years). Journal of Pediatric Nursing, 31, e109-e118.https://doi.org/10.1016/ j.pedn.2015.09.008.

Kristiansen, M., Kessing, L. L., Norredam, M., & Krasnik, A. (2015).Migrants' perceptions of aging in Denmark and attitudes towards remigration: Findings from a qualitative study. BMC Health Services Research, 15(225).

Kunzelmann, K. -H., & Dünninger, P. (1990). Dental fear and pain: Effect on patient's per-ception of the dentist. Community Dentistry and Oral Epidemiology, 18(5), 264–266.

https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1600-0528.1990.tb00073.x.

Li, M. Y., Yu, C. W., Yang, Y. C., & Chang, C. C. (2014). Reducing the pain of intravenous in-jections in preschool children. Hu li za zhi The Journal of Nursing, 61(2), 68–75.https:// doi.org/10.6224/JN.61.2S.68.

Mace, A. O., Mulheron, S., Jones, C., & Cherian, S. (2014).Educational, developmental and psychological outcomes of resettled refugee children in Western Australia: A review of School of Special Educational Needs: Medical and Mental Health input. Journal of Paediatrics and Child Health, 50(12), 985–992.

Mahat, G., & Scoloveno, M. A. (2003). Comparison of fears and coping strategies reported by Nepalese school-age children and their parents. Journal of Pediatric Nursing, 18(5), 305–313.https://doi.org/10.1053/S0882-5963(03)00102-7.

Mahat, G., Scoloveno, M. A., & Cannella, B. (2004). Comparison of children's fears of med-ical experiences across two cultures. Journal of Pediatric Health Care, 18(6), 302–307.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pedhc.2004.04.003.

Marasuna, O. A., & Eroglu, K. (2013). The fears of high school children from medical pro-cedures and affecting factors. The Journal of Current Pediatrics, 11, 13–22.https://doi. org/10.4274/Jcp.11.03.

Matanov, A., Giacco, D., Bogic, M., Ajdukovic, D., Franciskovic, T., Galeazzi, G. M., ... Priebe, S. (2013).Subjective quality of life in war-affected populations. BMC Public Health, 13(624).

Nicholson, J. I., & Pearson, Q. M. (2003).Helping children cope with fears: Using children's literature in classroom guidance. American School Counselor Association, 7(1), 15–19.

Perreira, K. M., & Ornelas, I. J. (2011).The physical and psychological well-being of immi-grant children. The Future of Children, 21(1), 195–218.

Reeves, R. C., Wells, G. A., & Waddington, H. (2017). Quasi-experimental study designs series-paper 5: Classifying studies evaluating effects of health interventions-a taxon-omy without labels. Journal of Clinical Epidemiology.https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclinepi. 2017.02.016.

Riggs, E., Davis, E., Gibbs, L., Block, K., Szwarc, J., Casey, S., ... Waters, E. (2012).Accessing maternal and child health services in Melbourne, Australia: Reflections from refugee families and service providers. BMC Health Services Research, 12(117), 2–16.

Serim-Yildiz, B., & Erdur-Baker, O. (2013). Examining fears of Turkish children and adoles-cents with regard to age, gender and socioeconomic status. Procedia - Social and Behavioral Sciences, 84, 1660–1665.https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sbspro.2013.07.010. Simons, L. E., Kaczynski, K. J., Conroy, C., & Logan, D. E. (2012). Fear of pain in the context

of intensive pain rehabilitation among children and adolescents with neuropathic pain: Associations with treatment response. The Journal of Pain, 3(12), 1151–1161.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpain.2012.08.007.

Svensson, K., Ramírez, O. F., Peres, F., Barnett, M., & Claudio, L. (2012). Socioeconomic de-terminants associated with willingness to participate in medical research among a di-verse population. Contemporary Clinical Trials, 33, 1197–1205.https://doi.org/10. 1016/j.cct.2012.07.014.

Teodorescu, D. -S., Siqveland, J., Heir, T., Hauff, E., Wentzel-Larsen, T., & Lien, L. (2012).

Posttraumatic growth, depressive symptoms, posttraumatic stress symptoms, post-migration stressors and quality of life in multi-traumatized psychiatric outpatients with a refugee background in Norway. Health and Quality of Life Outcomes, 10(84), 2–16.

White, H., & Sabarwal, S. (2014).Quasi-experimental design and methods. UNICEF Meth-odological Briefs Impact Evaluation No. 8.

William, L. I. C., & Lopez, V. (2008). Effectiveness and appropriateness of therapeutic play intervention in preparing children for surgery: A randomized controlled trial study. Journal for Specialists in Pediatric Nursing, 13(2), 63–73.https://doi.org/10.1111/j. 1744-6155.2008.00138.x.

Wilson, M. E., Megel, M. E., Enenbach, L., & Carlson, K. L. (2010). The voices of children: Stories about hospitalization. Journal of Pediatric Health Care, 24(2), 95–102.https:// doi.org/10.1016/j.pedhc.2009.02.008.

Zepinic, V., Bogic, M., & Priebe, S. (2012).Refugees' views of the effectiveness of support provided by their host countries. European Journal of Psychotraumatology, 3(8447), 1–9.