https://doi.org/10.1007/s10597-020-00594-8

ORIGINAL PAPER

Psychological Well‑Being Among Internally Displaced Adolescents

and the Effect of Psychopathology on PTSD Scores Depends on Gender

Şafak Eray1 · Duygu Murat2 · Halit Necmi Uçar3 · Edip Gönüllü4

Received: 25 September 2019 / Accepted: 24 February 2020 / Published online: 2 March 2020 © Springer Science+Business Media, LLC, part of Springer Nature 2020

Abstract

The purpose of this cross-sectional study was to investigate the post-traumatic symptoms and psychological well-being among internally displaced (ID) adolescents in the early phase of the conflict in the southeast part of Turkey and clarify the effect of psychopathology on PTSD scores depends on gender. With the help of the results of our study, we aimed to enhance our understanding of adolescent mental health. Our study was completed with 102 ID adolescents (42 boys, 60 girls). Our results showed that ID adolescents flee from conflict had significantly higher levels of mental disorders and PTSD. Girls show higher rates of PTSD symptoms than boys and there was no significant interactive effect of gender and emotional, behavioral and peer problems on PTSD. However, boys with ADHD seem to be more prone to develop PTSD than girls. We aimed to highlight the challenges facing adolescents forced to flee from conflict zones who were temporarily relocated. These results may help us to enlighten our understanding of ID adolescents and may suggest more studies to provide beneficial gender-specific intervention program.

Keywords Internal displacement · Adolescent · Mental health · Conflict

Introduction

Every year, millions of people are forced to leave their homes because of war, violence, or other threats to their safety. According to the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR 2016), 65.3 Mio. people worldwide have been forced to displace from their homes. Among them, nearly 21.3 Mio. refugees, over half of whom are under the age of 18 (UNHCR 2016). A refugee is defined as a dis-placed person who has been forced to leave his or her coun-try and unable to go home safely. An internally displaced person (IDP) has also been forced to flee his or her home but still remains within the borders of his or her country in

order to avoid violence. IDP is a new status distinguished from that of refugees by not being protected by international laws. IDPs are often referred to as refugees, although they do not fall within the current legal definition of a refugee (UNHCR 2016).

Individuals are usually displaced in order to reduce the effects of traumatic events. While displacement and relocation provide an immediate escape from the source of trauma, at the same time they create new problems as changes in their home, school, and parental employment disturb the social environment (Derluyn et al. 2009). These challenges may lead to an increase in mental disorders (Siriwardhana and Stewart 2012). Despite the fact that adolescents have been shown to be more resilient than adults (Sigal and Weinfeld 2001), following severe trau-mas such as conflicts and forced displacement, high lev-els of psychological stress, including posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD), depression, anxiety, and behavioral problems, have nonetheless been reported (Barenbaum et al. 2004; Derluyn et al. 2008; Melse et al. 2010; Reed et al. 2012). Both direct and indirect exposure to traumatic events may lead to subsequent mental health problems and PTSD in adolescents (Domanskaité-Gota et al. 2009). A study from Bosnia found that ID adolescents exhibited * Şafak Eray

drsafakeray@gmail.com

1 Department of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, Bursa

Uludağ University Medical Faculty, 16059 Bursa, Turkey

2 Department of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, Avcılar

Hospital, Istanbul, Turkey

3 Department of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, Medical

Faculty, Selçuk University, Konya, Turkey

4 Department of Anesthesia, Dokuz Eylül University, Izmir,

higher rates of depression than their non-displaced peers (Sujoldžić et al. 2006). In a study from ID camps in South-ern Darfur, 75% of 331 ID children in camps were reported to meet the diagnostic criteria for PTSD, and 38% of them had depression (Morgos et al. 2008). A study composed of a community sample of ID adolescents, returned former ID adolescents, and their non-displaced peers determined that ID adolescents had the highest incidence of internaliz-ing problems, followed by returnees, while non-displaced adolescents scored significantly lower (Mels et al. 2010). An epidemiological study from Turkey indicated that ID children and adolescents had significantly higher internal-izing, externalizing problems than their peers who have not displaced (Erol et al. 2005). In these recent studies, PTSD and internalizing problems were reported to be higher in girls while externalizing and conduct problems were higher in boys (Erol et al. 2005; Sujoldžić et al. 2006; Olff 2017). Also, acute subjective responses of PTSD such as threat perception, peritraumatic dissociation have been also reported to be more common in girls (Olff 2017).

Although there are many studies in the literature related with the psychiatric problems that developed after displace-ment, these studies were mostly on the refugees and the number of studies on ID adolescents is limited (Erol et al.

2005; Morton and Burnham 2008; Porter and Haslam 2005; Siriwardhana and Stewart 2012; Sun et al. 2015). In the stud-ies performed with ID adolescents, it is seen that most of the studies have only been conducted in sub-acute or chronic phase after the displacement, and the studies conducted in the acute phase of trauma are extremely limited (Erol et al.

2005; Sun et al. 2015). To the best of our knowledge, there is no study investigated ID adolescents due to conflict who were planning to return to their homes. Even when IDPs flee from conflict or attempt to settle elsewhere, problems generally remain until a permanent solution is found and adolescents mostly suffer from PTSD and psychiatric disor-ders. Also, sex differences in post-traumatic symptoms and effects of psychopathology on PTSD among ID adolescents are not well clarified.

Following the increase of the violence in southeastern cit-ies of Turkey, especially in Hakkari, the city of Van, where is about 205 km far away from Hakkari, hosted approximately six thousand families, fleeing from violence caused by an on-going conflict in 2016 study.

The purpose of this cross sectional study was to investi-gate the post-traumatic symptoms and psychological well-being among ID adolescents in the early phase of trauma in southeast region of Turkey who were displaced due to vio-lence and were planning to return to their homes, and clarify the effect of psychopathology on PTSD scores depends on gender. With the help of the results of our study, we aimed to enhance our understanding of adolescent mental health fol-lowing traumas in order to improve intervention programs.

Method

Participants and Procedures

Following the displacement, ID students were distributed to some schools which were determined by the Ministry of Education in Van. The necessary legal permission and approval were obtained from the Ethics Committee of the Van Training and Research Hospital before proceeding to the data collection stage (Date: 12.10.2016, No: 2016/9). We contacted the Ministry of Education and high schools and made announcement about our study. Than we con-tacted the participating schools’ principals and psycholog-ical counselors to inform them of the study. The research-ers visited the schools at times specially designated for parents to visit in order to provide information about the study. Information regarding the study was given to all parents and students both orally and in writing. The vol-unteer students from the sixth, seventh, and eighth grades who were in class on the days that research was conducted and whose parents consented were invited to their school counselor’s office. All participants were interviewed by the researchers and an only ID adolescent were included the study. 123 participants were wanted to fill out the study questionnaires by themselves in a comfortable area and the researchers provided help (when needed) interpreting the questions. A total of 12 students refused to participate in the study (9 of students had not parent consent form and 3 of students refused to participate withdraw from the study on their own accord). The forms which are with unreliable answers (such as all the questions marked as the same) or if any section of questionnaire was left blank, were considered incomplete form (2 forms). The study group was determined according to the questions in infor-mation collection form (ICF) that participants answered regarding whether they had been displaced from Hakkari by the conflict and whether they were planning to return. ID adolescents were asked if they plan to return their origi-nal home or not and nine displaced adolescents, who did not plan to return, were excluded the study. Thus, the final sample was 102 adolescents.

Measures

Research data were collected using an information collec-tion form (ICF) developed by the researchers, the Child Posttraumatic Stress Disorder-Reaction Index (CPSD-RI), and Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire (SDQ).

The ICF was created by the researchers. The ICF sur-veyed students concerning their socio-demographic char-acteristics, including age, sex, educational status and

occupation of parents, economic status and psychophysi-ological functions. Socioeconomic levels were determined according to the responses of students on the question-naires regarding family income from 1 (< 1500 TRY) to 3 (> 4500 TRY). The questions on the ICF were based on the Turkey’s official starvation and poverty limits for 2015 (Confederation 2015, November, 26).

The SDQ was translated into Turkish by Güvenir et al. (2008). It was developed in 1997 by British psychiatrist Robert Goodman for screening behavioral and emotional problems in children and adolescents (Goodman 2001). The SDQ has 25 items evaluating both positive and negative emotions and behavioral features. These items are grouped into 5 sub-scales, which contain 5 items in each accord-ing to both appropriate diagnostic measures and the results of factor analysis: ADHD, behavioral problems, emotional problems, peer relationship problems and social behaviors. In our country, the Cronbach’s alpha for the SDQ was found to be 0.73 in a study by Güvenir et al. (2008). Cronbach’s alpha coefficient was 0.729 for our sample.

In order to examine the severity of PTSD symptoms, the CPTS-RI was developed by Pynoos et al. (1987). CPTS-RI was developed to evaluate the stress reactions that occur in children and adolescents following various traumatic experi-ences. It uses a self-reported, 5-point Likert scale ranging from “none of the time” (0) to “most of the time” (4) and con-tains 20 items. A total score is obtained by adding the scores for all items after adjusting for reverse-scored items. When the total score is between 12 and 24, mild PTSD symptoms are indicated; a score of 25 to 39 indicates moderate PTSD symptoms; a score between 40 and 59 indicates severe PTSD symptoms; and a score of 60 or above points indicates very severe PTSD symptoms. Scores of 40 and above are cor-related with clinical PTSD diagnosis (Pynoos et al. 1993). The Turkish validity and reliability study was carried out by Erden et al. (1999). The reliability and validity study of the Turkish version was conducted with primary school children who had survived an explosion in Turkey. Test–retest reli-ability was 0.86 and internal consistency (alpha) was 0.75 (Erden et al. 1999). In this study, internal consistency (alpha) was 0.91. Pynoos et al. reported that CPTS-RI, scores ≥ 40 were correlated with a clinical PTSD diagnosis (Pynoos et al. 1993).

Data Analysis

Data were evaluated using the IBM Statistical Package for the Social Sciences Statistics 23.0 statistical software pack-age program, and expressed as mean and standard devia-tion, with minimal and maximal levels. Comparison of the continuous variables between the groups was performed using the student’s t-test for normally distributed variables, while the Mann–Whitney U test was used for comparison of

the non-normally distributed variables and non-parametric parameters. Comparison of the categorical variables of the groups was performed using the chi square test. In other assessment p value of < 0.05 was considered statistically significant. Scores on the PTSD scale, and SDQ scale were statistically compared between the girls and boys using a Student’s t-test. To investigate the interactive effect of gen-der, we conducted a two-way analysis of variance (ANOVA), with gender, and psychopathology based on SDQ as inde-pendent variables and scores on the PTSD scale as depend-ent variable. The significance threshold was set at 0.05 (two-tailed) in all tests.

Results

Study was completed with 42 boys, 60 girls, and in a total 102 adolescent students. The mean age of the participants was 14.78 ± 0.86. The majority of students (79.4%, n = 81) had nuclear family type. The socio-demographic character-istics (Including sex, age, education, and employment) of the groups were shown in Table 1.

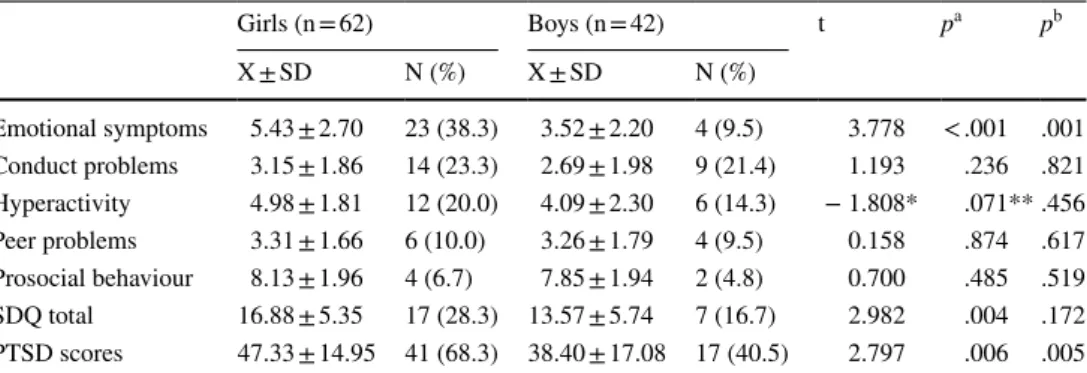

When we evaluated the SDQ scores in boys and girls, there were no significant differences between the genders in terms of social skills, behavioral problems, attention deficit hyperactivity problems, but peer problems and emotional problems were reported to be higher in girls. Emotional behavioral problems in terms of gender were indicated in Table 2. When the results of PTSD were evaluated in terms of gender, PTSD scores were significantly higher in girls than in boys. Girls had a significantly higher estimated prevalence of PTSD than did boys (70.0 vs. 45.2%). Girls had also a significantly higher estimated prevalence of Emo-tional Problems than did boys (38.3 vs. 9.5%). The results are given in Table 2.

Of these participants, 56.9% (n = 58) met study criteria for PTSD as assessed with the CPTS-RI. The CPTS-RI scores averaged 43.65 ± 16.39. Based on the total PTSD score on the CPTS-RI, 1.0% (n = 1) of the participants reported few or no symptoms, 13.7% (n = 14) reported symptoms as mild, 28.4% (n = 29) as moderate, 36.3% (n = 37) as severe, and 20.6% (n = 21) reported very severe levels of PTSD. The correlations between PTSD scores and SDQ scores of groups were given in Table 3.

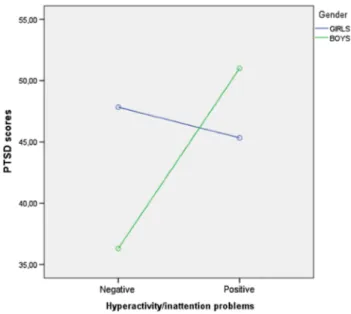

Regarding the two-way ANOVA of gender and hyperac-tivity/inattention problems, there was a significant interac-tive effect of gender X hyperactivity/inattention problems on PTSD scores (F = 4.043; p = 0.047). There was no significant effect of gender (F = 0.470; p = 0.495), and no significant effect of hyperactivity/inattention problems (F = 2.034; p = 0.157) on PTSD scores (Fig. 1).

Regarding the two-way ANOVA of gender and other SDQ subscales, there was no significant interactive effect

of gender X SDQ subscales (emotional, conduct, peer and prosocial) on PTSD scores. According to our results boys with ADHD have higher PTSD scores than the girls with ADHD.

Discussion

In the present study, the psychological effects of internal displacement following mass violence on adolescents who were planning to return to their original homes have been

Table 1 Socio-demographical variability and gender differences

*p score of Chi-square test between girls and boys

Girls n = 60 Boys n = 42 Total n = 102 p*

Age 14.75 ± 0.79 14.83 ± 0.96 14.78 ± 0.86 .364 Family income < 1500 TL 41 (68.3%) 31 (73.8%) 72 (70.6%) .706 1500–4500 TL 17 (28.3%) 9 (21.4%) 26 (25.5%) > 4500 TL 2 (3.3%) 2 (4.8%) 4 (3.9%) Cohabitation of parent Married 56 (93.3%) 38 (90.5%) 94 (92.2%) .597 Divorced/widowed 4 (6.7%) 4 (9.5%) 8 (7.8%)

Mother’s educational level

Never went to school 33 (55.0%) 25 (59.5%) 58 (56.9%) .956

Primary school 16 (26.7%) 10 (23.8%) 26 (25.5%)

Middle school 7 (11.7%) 5 (11.9%) 12 (11.8%)

High school/university 4 (6.7%) 2 (4.8%) 6 (5.9%)

Mothers’ employment status

Unemployed 60 (100.0%) 42 (100.0%) 102 (100.0%)

Father’s educational level

Never went to school 7 (11.7%) 8 (19.0%) 15 (14.7%) .056

Primary school 21 (35.0%) 11 (26.2%) 32 (31.4%)

Middle school 16 (26.7%) 8 (19.0%) 24 (23.5%)

High school 7 (11.7%) 13 (31.0%) 20 (19.6%)

University 9 (15.0%) 2 (4.8%) 11 (10.8%)

Father’s employment status

Unemployed 32 (53.3%) 25 (59.5%) 57 (55.9%) .535

Employed/retired 28 (46.7%) 17 (40.5%) 45 (44.1%)

Table 2 SDQ and PTSD scores

and rates of boys and girls

X mean of the scores, SD Standard Deviation *Mann Whitney U test z score

**Mann Whitney U test p score

a Student t test p score for numeric values of SDQ b p score of Chi-square test for categoric evaluation of SDQ

Girls (n = 62) Boys (n = 42) t pa pb X ± SD N (%) X ± SD N (%) Emotional symptoms 5.43 ± 2.70 23 (38.3) 3.52 ± 2.20 4 (9.5) 3.778 < .001 .001 Conduct problems 3.15 ± 1.86 14 (23.3) 2.69 ± 1.98 9 (21.4) 1.193 .236 .821 Hyperactivity 4.98 ± 1.81 12 (20.0) 4.09 ± 2.30 6 (14.3) − 1.808* .071** .456 Peer problems 3.31 ± 1.66 6 (10.0) 3.26 ± 1.79 4 (9.5) 0.158 .874 .617 Prosocial behaviour 8.13 ± 1.96 4 (6.7) 7.85 ± 1.94 2 (4.8) 0.700 .485 .519 SDQ total 16.88 ± 5.35 17 (28.3) 13.57 ± 5.74 7 (16.7) 2.982 .004 .172 PTSD scores 47.33 ± 14.95 41 (68.3) 38.40 ± 17.08 17 (40.5) 2.797 .006 .005

studied. Our results showed that ID adolescents flee from conflict had significantly higher levels of mental disorders and PTSD. Girls show higher rates of PTSD symptoms than the boys and there was no significant interactive effect of gender and emotional, behavioral and peer problems on PTSD. However, boys with ADHD seem to be more prone to develop PTSD than girls.

Studies of adults have shown that forced migration was strongly associated with psychopathology and PTSD (Ergun et al. 2008; Porter and Haslam 2005; Steel et al. 2009),

consistent with the literature on adolescents (Fremont

2004). A study conducted with a Turkish epidemiological sample, ID children and adolescents were found to have more internalizing problems when some of the confound-ing factors such as physical illness, age, gender, and urban residence were controlled for (Erol et al. 2005). Similarly, in the present study, 23.5% of ID adolescents were suffered from emotional and behavioral problems. The present study included adolescents who were temporarily displaced in Van but planned to return to their original homes. Displacement to a new place, unemployment, low socioeconomic status, make it difficult for adolescents to adapt to a new environ-ment, thus increasing the development of mental disorders. Mels et al. reported that lower socioeconomic status and daily stressors cause the most psychological distress in ID adolescents (Mels et al. 2010). And also we should take into account the reason for displacement that is also a risk factor for adolescent’s mental health. (Porter and Haslam 2005; Fremont 2004; Ergun et al. 2008; Siriwardhana and Stewart

2012).

The main psychiatric consequences of the displacement were stated in literature as PTSD and emotional behavioral problems. Nearly all participants were shown PTSD symp-tom and more than half of them were shown severe or very severe PTSD symptoms. When we examined the effects of gender, on mental disorders and PTSD, it found that psy-chiatric symptoms occur more frequently in girls than boys. A previous study regarding displaced adolescents indicated that girls are more prone to developing internalizing prob-lems than boys (Derluyn et al. 2008). In a meta-analysis, girls were found to be at greater risk for developing PTSD following interpersonal traumas (Alisic et al. 2014). In the present study, emotional and behavioral problems were sig-nificantly higher in girls than in boys, consistent with what has been reported in the literature (Alisic et al. 2014). Con-sistent with the literature internalizing problems reported

Table 3 Correlations between PTSD scores and SDQ scores

r Pearson correlation test r score, p Pearson correlation test p score *Spearman’s correlation test r score

**Spearman’s correlation test p score Emotional

symptoms Conduct problems Hyperactivity Peer problems Prosocial behaviour PTSD score of girls r 0.505 0.087 − 0.095* .300 0.127 p .000 .510 .469** .020 .332 PTSD score of boys r 0.187 0.164 0.107* .175 − 0.005 p .236 .300 .500** .267 .976

PTSD score of total group

r 0.433 0.148 0.080* .238 0.085

p .000 .136 .423** .016 .395

Fig. 1 Gender X hyperactivity/inattention problems on PTSD scores. X mean of the scores, SD standard deviation. *Mann Whitney U test z score. **Mann Whitney U test p score. aStudent t test p score for

numeric values of SDQ. bp score of Chi-square test for categoric

to be more common in girls than boys (Erol et al. 2005). When we correlate the psychopathological symptoms and PTSD scores, emotional problems and peer problems are related to PTSD symptoms in girls, however it is not correct among boys. Thus, indicate that girls who are more vulner-able and had negative peer relations are risky for develop-ment ADHD. On the other hand, for male gender there is no correlation. When we investigate the interactive effect of gender and psychopathology on PTSD, our results suggest that the boys with ADHD have higher PTSD scores than the girls with ADHD. Our results suggest that after traumatic events adolescents need different interventions. It seems that appropriate treatment of neurodevelopmental disorders in males is crucial for preventing PTSD and also emotional symptoms and supportive peer relations are crucial in girls. However, our results reflex our study group. The number of subjects are insufficient to extend your findings to all ID adolescents.

There are several limitations in this present study. The main limitation is the sample size of the study. We need to repeat our results in larger samples. The present study was also composed only of volunteer adolescents who were continuing their education; we should also have included adolescents who were not able to continue their education. There may be a big amount of children who were displaced and had to give up their school we could not evaluate them. Also, In our study we could not have a control group, in the period of the study there was a legal curfew and many families forced to internally displace which make difficult have a control group that exposes to the same trauma but did not displace. Thus not having a control group may restrict the results and the interpretation. Another limitation is that participants were evaluated by self-reporting rather than undergoing clinical interviews. Thus diagnosis of the par-ticipants was not made by a clinical interview. On the other hand, both CPTS-RI and SDQ have been validated for ado-lescents in Turkish. Also evaluating socioeconomic status from youth reporting on family income may be considered as a limitation.

Despite these limitations, our study is significant because it is the first study on ID adolescents in Turkey who were planning to return to their homes. The major strength of our study is the immediate assessment of psychiatric symptoms in a specific study group, all of whose members were dis-placed by the same conflict and not resettled. We wanted to highlight the challenges of adolescents who have had to tem-porarily flee from their homes following the mass violence. The present study has shown that conflict related trau-mas and internal displacement due to violence negatively affect adolescent mental health. Even though escaping a conflict zones might decrease the effects of trauma; our study showed that adolescents still have to survive with many psychiatric symptoms following displacement. Thus,

we can debate if temporary displacement is helpful follow-ing traumas or create new challenges. For public health as well as preventive mental health, it is important to provide healthcare and economic, educational, and social support for families who are forced to migrate. Also gender bias is another important point of our study. To fully understand the differences, we need more gender- and sex-sensitive research as well as reporting and develop gender specific intervention programs.

References

Alisic, E., Zalta, A. K., Van Wesel, F., Larsen, S. E., Hafstad, G. S., Hassanpour, K., et al. (2014). Rates of post-traumatic stress dis-order in trauma-exposed children and adolescents: Meta-analysis. The British Journal of Psychiatry, 204(5), 335–340.

Barenbaum, J., Ruchkin, V., & Schwab-Stone, M. (2004). The psy-chosocial aspects of children exposed to war: Practice and policy initiatives. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 45(1), 41–62.

Confederation, T. T. U. (2015). November 2015 Hunger and Poverty Limit. Retrieved November 26, 2015 from www.turki s.org.tr/ dosya /VJ2DA 9G9d5 7X.pdf.

Derluyn, I., Broekaert, E., & Schuyten, G. (2008). Emotional and behavioural problems in migrant adolescents in Belgium. Euro-pean Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, 17(1), 54–62.

Derluyn, I., Mels, C., & Broekaert, E. (2009). Mental health problems in separated refugee adolescents. Journal of Adolescent Health, 44(3), 291–297.

Domanskaité-Gota, V., Elklit, A., & Christiansen, D. M. (2009). Vic-timization and PTSD in a Lithuanian national youth probability sample. Nordic Psychology, 61(3), 66.

Erden, G., Kılıç, E., Uslu, R., & Kerimoğlu, E. (1999). The validity and reliability study of Turkish version of child posttraumatic stress reaction index. Çocuk ve Gençlik Ruh Sağlığı Dergisi/Turkish Journal of Child and Adolescent Mental Health, 6(3), 143–149. Ergun, D., Çakici, M., & Çakici, E. (2008). Comparing psychological

responses of internally displaced and non-displaced Turkish Cyp-riots. TORTURE: Journal on Rehabilitation of Torture Victims and Prevention of Torture, 18(1), 20–28.

Erol, N., Şimşek, Z., Öner, Ö., & Munir, K. (2005). Effects of internal displacement and resettlement on the mental health of Turkish children and adolescents. European Psychiatry, 20(2), 152–157. Fremont, W. P. (2004). Childhood reactions to terrorism-induced

trauma: A review of the past 10 years. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, 43(4), 381–392. Goodman, R. (2001). Psychometric properties of the strengths and

difficulties questionnaire. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, 40(11), 1337–1345.

Güvenir, T., Özbek, A., Baykara, B., Arkar, H., Şentürk, B., & İncekaş, S. (2008). Psychometric properties of the Turkish version of the strengths and difficulties questionnaire (SDQ). Çocuk ve Genç-lik Ruh Sağlığı Dergisi/Turkish Journal of Child and Adolescent Mental Health, 15(2), 65–74.

Mels, C., Derluyn, I., Broekaert, E., & Rosseel, Y. (2010). The psycho-logical impact of forced displacement and related risk factors on Eastern Congolese adolescents affected by war. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 51(10), 1096–1104.

Morgos, D., Worden, J. W., & Gupta, L. (2008). Psychosocial effects of war experiences among displaced children in southern Darfur. OMEGA: Journal of Death and Dying, 56(3), 229–253.

Morton, M. J., & Burnham, G. M. (2008). Iraq’s internally displaced persons: A hidden crisis. JAMA, 300(6), 727–729.

Olff, M. (2017). Sex and gender differences in post-traumatic stress disorder: An update. European Journal of Psychotraumatology, 8(sup4), 1351204.

Porter, M., & Haslam, N. (2005). Predisplacement and postdisplace-ment factors associated with postdisplace-mental health of refugees and inter-nally displaced persons: A meta-analysis. JAMA, 294(5), 602–612. Pynoos, R. S., Frederick, C., Nader, K., Arroyo, W., Steinberg, A., Eth,

S., …, Fairbanks, L. (1987). Life threat and posttraumatic stress in school-age children. Archives of General Psychiatry, 44(12), 1057–1063.

Pynoos, R. S., Goenjian, A., Tashjian, M., Karakashian, M., Manjikian, R., Manoukian, G., …, Fairbanks, L. A. (1993). Post-traumatic stress reactions in children after the 1988 Armenian earthquake. The British Journal of Psychiatry, 163(2), 239–247.

Reed, R. V., Fazel, M., Jones, L., Panter-Brick, C., & Stein, A. (2012). Mental health of displaced and refugee children resettled in low-income and middle-low-income countries: Risk and protective factors. The Lancet, 379(9812), 250–265.

Sigal, J. J., & Weinfeld, M. (2001). Do children cope better than adults with potentially traumatic stress? A 40-year follow-up of Holo-caust survivors. Psychiatry: Interpersonal & Biological Pro-cesses, 64(1), 69–80.

Siriwardhana, C., & Stewart, R. (2012). Forced migration and mental health: Prolonged internal displacement, return migration and resilience. International Health, 5, 19–23.

Steel, Z., Chey, T., Silove, D., Marnane, C., Bryant, R. A., & Van Ommeren, M. (2009). Association of torture and other potentially traumatic events with mental health outcomes among populations exposed to mass conflict and displacement: A systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA, 302(5), 537–549.

Sujoldžić, A., Peternel, L., Kulenović, T., & Terzić, R. (2006). Social determinants of health: A comparative study of Bosnian adoles-cents in different cultural contexts. Collegium Antropologicum, 30(4), 703–711.

Sun, X., Chen, M., & Chan, K. L. (2015). A meta-analysis of the impacts of internal migration on child health outcomes in China. BMC Public Health, 16(1), 66.

UNHCR (Producer). (2016). Handbook for the protection of internally displaced persons. Retrieved February 1, 2016 from https ://www. unhcr .org/figur es-at-a-glanc e.html.

Publisher’s Note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to