ARTISTIC PRACTICE IN THE AFTERMATH OF POSTMODERNISM: A CASE STUDY A Master's Thesis by İLKER ÇELEN Department of Communication and Design İhsan Doğramacı Bilkent University

Ankara january 2017

To

ARTISTIC PRACTICE IN THE AFTERMATH OF POSTMODERNISM: A CASE STUDY

Graduate School of Economics and Social Sciences of

İhsan Doğramacı Bilkent University

by İLKER ÇELEN

In partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of MASTER OF ARTS

in

Media and Visual Studies

THE DEPARTMENT OF COMMUNICATION AND DESIGN İHSAN DOĞRAMACI BİLKENT UNIVERSITY

ANKARA January 2017

ABSTRACT

ARTISTIC PRACTICE IN THE AFTERMATH OF POSTMODERNISM: A CASE STUDY

Çelen, İlker

MA, in Media and Visual Studies Supervisor: Asst. Prof. Dr. Ahmet Gürata

January 2017

Postmodern discourse is still the dominant factor in the 21st century art production. On the other hand, there have appeared a number of alternative concepts which suggest that the influence of postmodern tendencies on art is diminishing, becoming unable to meet today's realities, or transforming altogether. The common ground among these new concepts is that they postulate a partial return to modernist tendencies such as creativity, originality, and/or uniqueness, without denying the achievements of postmodernism such as deconstruction, open-endedness or interaction, thus creating an oscillation. The thesis aims to examine a selection of recent new media works which are all connected with these new tendencies in one way or another, based on their conceptual

backgrounds and/or their aesthetic approach in relation to the evolution of new media. While investigating these artworks by case study approach, the thesis claims that these artworks can be taken as indicators of a new understanding in arts.

ÖZET

POSTMODERNİZM SONRASI SANATSAL PRATİKLER: BİR VAKA ÇALIŞMASI

Çelen, İlker

Yüksek Lisans, Medya ve Görsel Calışmalar Tez Yöneticisi: Yrd. Doç. Dr. Ahmet Gürata

Ocak 2017

Postmodern anlatım, 21. yüz yıl sanat üretiminde halen en baskın unsurdur. Diğer bir yandan, bu eğilimlerin etkilerinin azaldığını, günümüz gerçeklerini karşılayamaz hale geldiğini veya topyekün değişime uğradığını öne süren alternatif kavramlar da ortaya çıkmaya başlamıştır. Bu yeni kavramların temel ortak noktası postmodernizmin yapıbozum, açık uçluluk veya etkileşim gibi kazanımlarını yadsımadan, yaratıcılık, özgünlük ve/veya biriciklik gibi modernist eğilimlere kısmi bir geri dönüş yaşandığını, dolayısıyla modernizm ve postmodernizm arasında bir salınımın oluştuğunu iddia etmeleridir. Bu tez, kavramsal geçmişlerini ve/veya yeni medyanın evrimi ile ilgili estetik yaklaşımı temel alarak, bu yeni eğilimlerle bir şekilde bağlantılı, yakın zamanda üretilmiş yeni medya çalışmalarından bir seçkiyi incelemeyi amaçlamaktadır. Sözü geçen eserleri, vaka analizi yaklaşımı ile incelerken, bu sanat eserlerinin sanatta yeni bir anlayışın göstergeleri olarak ele alınabileceğini iddia etmektedir.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

First of all, I want to thank everyone who supported and accompanied me throughout my journey in Bilkent. You all know who you are.

I want to thank my thesis advisor Assistant Professor Ahmet Gürata for his patience, and infinite support.

I want to thank İpek Altun for being around whenever I needed a friend, and of course, for making everything about Bilkent easier for me. What I know for sure is that

someday she's going to rock the world.

I want to thank my family who never stopped believing in me. I hope they won't stop anytime soon.

And finally, I want to thank the greatest architect that I know, my lovely wife Ezgi, for being my love, my trouble, my companion, my struggle, my relief, my joy, my home and my friend. Her immeasurable support and patience always gave me enough reason to keep going. Every time I felt like giving up, she somehow convinced me not to. I guess I'm lucky to have a stubborn wife in the long run. Thank you.

TABLE OF CONTENTS Page ABSTRACT... iii ÖZET... iv ACKNOWLEDGMENTS... v TABLE OF CONTENTS... vi

LIST OF TABLES... viii

LIST OF FIGURES... ix

CHAPTER I: INTRODUCTION... 11

CHAPTER II: CONCEPTUALISATION OF CRISES: MODERNISM AND POSTMODERNISM... 17

2.1. Crisis of Modernism... 17

2.2. Crisis of Postmodernism... 19

CHAPTER III: A PROPOSAL FOR THE AFTERMATH OF POSTMODERNISM: ALTERNATIVE CONCEPTS AND THEIR IMPACT ON ART... 24

3.1. Alternatives in Theory: Metamodernism... 24

3.2. Alternatives in Theory: Common Grounds... 28

CHAPTER IV: CASE STUDIES... 39 4.1. Computer Code and The New Aesthetics as Index: A Glimpse

of Future and Now... 39

4.2. Metamodern Art: Turner, Rönkkö & LaBeouf... 46

4.3. Holly Herndon's Chorus: Aesthetics of Failure... 50

4.4. Virtual Reality as a New Medium... 57

4.4.1. REZ: Implementation of Art Into The Mainstream... 60

4.4.2. Quill: Potential of Oculus Rift as a Creative Platform... 69

CHAPTER 5: CONCLUSION... 79

LIST OF TABLES

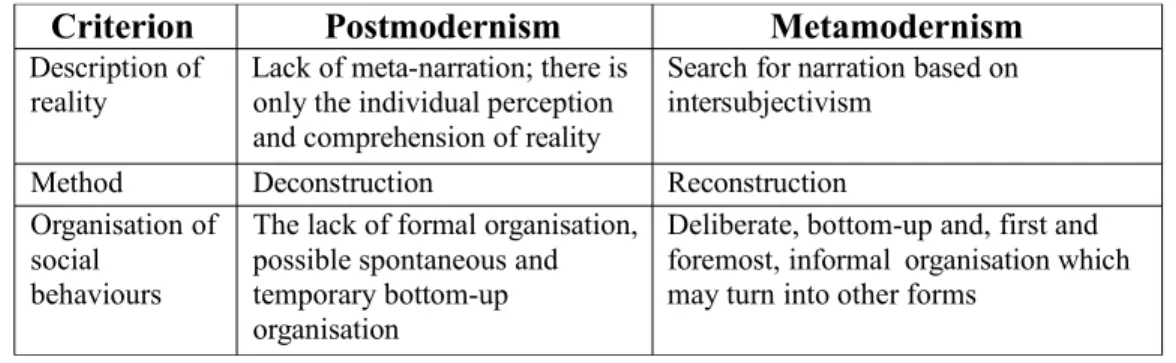

Table 1: Comparison of postmodernism and metamodernism in view of challenges of the social sciences (Komańda, 2016)... 26

LIST OF FIGURES

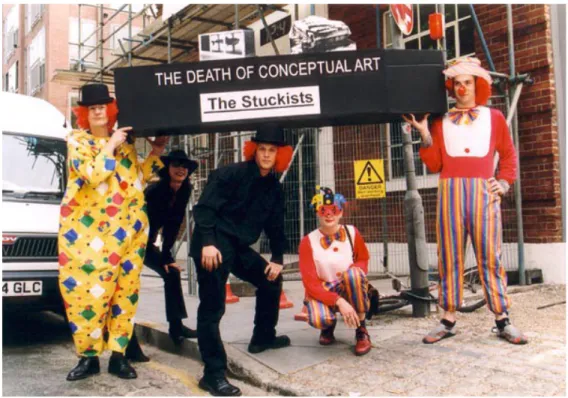

Figure 1. Stuckist demo outside White Cube Gallery... 34

Figure 2. Pixelated chair design by Japanese designer Kunihiko Morinaga... 44

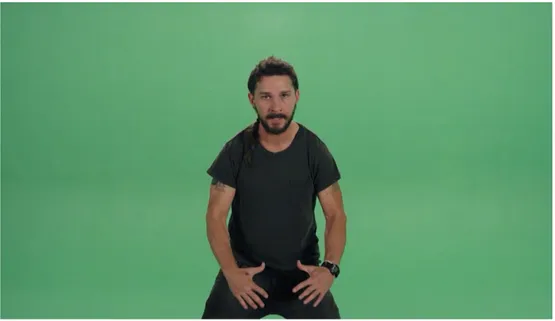

Figure 3. LaBeouf against the green screen in the raw footage of #INTRODUCTIONS... 47

Figure 4. Manipulated footage of LaBeouf at the graduation show, mimicking a salesman on a TV sale commercial... 48

Figure 5. Video still from Holly Herndon's music video “Chorus”... 51

Figure 6. Screenshot from iWitness... 53

Figure 7. Comparison of different angles in Chorus... 55

Figure 8. Comparison of two different VR headsets from different eras... 58

Figure 9. The first musical input in REZ is represented as a 'dot'... 62

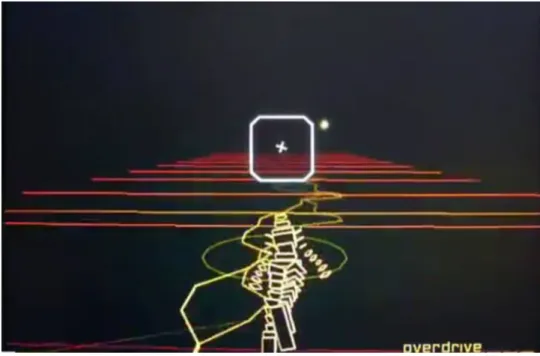

Figure 10. A screenshot from the early 'layers' in Rez... 63

Figure 11. A screenshot of more complex advanced abstract layers in Rez... 64

Figure 12. In comparison: On the left, Circles in a Circle (1924) by Kandinsky, on the left, international box art of REZ (2001)... 66

Figure 13. Screenshot from Oculus Medium. A digital sculpture made out of virtual clay... 70

Figure 15. Screenshot from 3D illustration of a grocery store made with Quill, by Carlos Felipe Leon... 74 Figure 16. Screenshot from the same 3D grocery store from a different angle... 75 Figure 17. Pablo Picasso "draws" a centaur in the air with light, 1949... 77

CHAPTER I: INTRODUCTION

Whether they are grounded on the level of wishful thinking or serious confrontation, various concepts related with postmodernism's 'future' has been around for quite some time. David Rudrum and Nicholas Stavris (2015), in their book Supplanting the

Postmodern: An Anthology of Writings on the Arts and Culture of the Early 21st

Century, describe these concepts as “a number of offshoots of the postmodern” which,

they claim to have been “striking out in a multitude of new directions from it, and some of these directions seem to run athwart the main postmodern currents.” For these concepts, they use a metaphor, 'delta effect' as they claim that postmodernism which was once a 'mighty river,' in time, slowed to a halt, then diverged and splitted into multiple channels along different courses. Cultural theorists, critics and artists gave these different concepts different names such as metamodernism, digimodernism, or altermodernism, etc. in order to “diagnose or champion ways in which the art, literature, and culture of the twenty-first century involve important differences and new departures from the mainstream of postmodernism” (Rudrum & Stavris, 2015: 3). Therefore we can claim that it is more likely a matter of diagnosing the flaws of postmodernism, rather than an objection. Even though these allegedly diverse concepts seem far from conclusion, they are, however, signs of a transformation period – of postmodernism – and it seems to me that this period can be marked with the struggle to justify the claims

of these so-called alternatives. On the other hand, postmodernism itself is also a subject of such transformation which, in this case, is that of modernism. For Lyotard (1984: 79), postmodernism is “not modernism at its end but in the nascent state, and this state is constant.” He describes modern aesthetic as an aesthetic of the sublime which is

fundamentally nostalgic, and this mode of nostalgia – although it offers to the viewer or the reader a matter for pleasure – eventually can not constitute the real sublime

sentiment which is an essential mixture of pleasure and pain, whereas postmodernism – by reducing the influence of the mode of nostalgia and replacing enjoyment with presentation of the unpresentable – can reach the real sublime mentioned, and this shift eventually offers new conditions for the artists and in this regard, Lyotard expalins: A postmodern artist or writer is in the position of a philosopher: the text he writes,

the work he produces are not in principle governed by preestablished rules, and they cannot be judged according to a determining judgement, by applying familiar

categories to the text or to the work. Those rules and categories are what the work of art itself is looking for. The artist and the writer, then, are working without rules in order to formulate the rules of what will have been done. (1984: 81)

This can be regarded as a prime example of a paradigm shift and the co-existence of two inherently different discourses within each other: “A work can become modern only if it is postmodern” (Lyotard, 1984: 79). So, within this trajectory, the new

contemporary conceptions mentioned above can be claimed to be the symptoms of the fact that it is now postmodernism's turn to be questioned: “What lies beyond

postmodernism? Of course, no one knows; we hardly know what postmodernism was. But questions have a way of inveigling an answer” (Hassan, 2003). In this regard it would not be surprising that recent contemporary practices in the art have been contested and criticized, especially in a time when contemporary tools of

communication are claimed to have already been internalized to a point where

“software has become a commonsense shorthand for culture and hardware a shorthand for nature” (Chun, 2005).

As we have already argued, the struggle to understand the transition periods and their outcomes has always existed. Famous American visual art critic Clement Greenberg's remark on the emergence of postmodernism in art is revealing as much as it is archaic, considering the fact that it was written in 1980, a relatively early stage of

postmodernism in art:

Postmodern is a rather new term. It's a catchy one and has been coming up more and more often in talk and writing about the arts, and not only about the arts. I'm not clear as to just what it points.... A friend and colleague had been to a symposium about postmodern last spring. I asked him how the term had gotten defined at that symposium. As art, he answered, that was no longer self-critical. I felt a pang. I myself had written twenty years ago that self criticism was a distinguishing trait of Modernist art. My friend's answer made me realize as I hadn't before how

inadequate that was as a conveying definition of Modernism or the modern. (Greenberg, 1980)

More than two decades after Greenberg's rather pessimistic – even sentimental – credit, Baudrillard's remark on contemporary art clearly illustrates the substantial change in the apprehension of postmodernist art and (in comparison with the former) the extent it reached:

The adventure of modern art is over. Contemporary art is only contemporary of itself. It no longer transcends itself into the past or the future. Its only reality is its operation in real time and its confusion with this reality. Nothing differentiates it from technical, advertising, media and digital operations. There is no more

transcendence, no more divergence, nothing from another scene: it is a reflective game with the contemporary world as it happens. This is why contemporary art is null and void: it and the world form a zero sum equation. (Baudrillard, 2005: 89)

What is essential about these statements, regarding their historical significance, is that they both point out a certain type of crisis – one is of modern and the other, of

postmodern – or an ambivalent resolution, which renders existing discourse somewhat unsustainable or jeopardized. For instance, obscurity in the art of Marcel Duchamp is a good example as an indicator of crisis and of being a precursor to what was to come after it, as if modernism, though involuntarily at those times, had already foreseen its own dissociation (Jameson, 1991: 4). Thus, the paradigm of the arts, inevitably, ended up in a transformation process in which methods of 'creative act' was once again put in question. This contradictory condition itself almost became the very defining

characteristic of then-existing art aesthetically, yet again the discourse of contemporary art today, with all of its complexity, is, by all means, no exception. In my opinion, it is this exact moment of confusion from which the new conceptions are claimed to be emerging.

The current thesis hereby aims to examine a selection of new media works which are all connected with these new tendencies in one way or another, based on their conceptual backgrounds and/or their aesthetic approach in relation to the evolution of media. While investigating these artworks by case study approach, the thesis claims that these

artworks can be taken as indicators of a new understanding, and at times, can be

considered as a seemingly romantic departure from postmodernism, if not substantially utopic. Their theoretical basis in common is their somewhat unclear yet tangible struggle to deal with postmodern concepts like irony, nihilism, relativism,

deconstruction and rejection of the grand narratives, and converge (or dare to replace) them with hope, sincerity, affect, romanticism and the potential for grand narratives and universal truths, however, they are not in a state of total denial of what has been learned from postmodernism (Turner, 2015). Ultimately, these new alternatives are not rejecting the notions of postmodernism, but rather putting an effort into the possibility of an oscillation between the postmodern and the modern in order to create a new condition in which this oscillation would remain constant. Personally, I find this alleged gradual transformation period unique in terms of its historical relevance, and therefore worth analyzing.

The thesis consists of three chapters. The first chapter aims to conceptualize the crisis of modernism and, in turn, of postmodernism in art, thus provides a contextual background for the movements, or tendencies in general, which are claimed to have signaled a recent departure from postmodernism. The second chapter examines the evolution of media and art by establishing a relationship with the theoretical aspects of these new tendencies such as metamodernism, digimodernism, altermodernism. However, the primary emphasis will mostly be on metamodernism because it has been the most widely used term among others. The validity of conceptual art in the postmodernist sense will be questioned at times. Additionally, discourses from several other disciplines, which contextually follow the same so-called

departure-from-postmodernism pattern, will be briefly explained just for supplementary purposes. In the third and the final chapter of the thesis, recent contemporary inclinations and several

new media artworks which can be regarded as the indicators of this so-called post-postmodern condition will be examined. Firstly, the effect of computer code on art and aesthetics in contemporary culture will be covered, and then, the chapter will introduce a relatively recent phenomenon called The New Aesthetics, by which a new state of visual perception unique to our time will be justified. Following that, it will examine a new media artwork titled #INTRODUCTIONS, a collaboration between

self-proclaimed metamodern artists Luke Turner, Nastja Säde Rönkkö and actor Shia LaBeouf, revealing its ties with new movements and extensive participation. The next sub-chapter will be explaining Holly Herndon's music video titled Chorus, focusing both on its visuals (primary) and sound (secondary). The context will be constructed upon the deliberate use of failure in computer aesthetics as a creative method, and eventually, Herndon's way of constructing sound. Moreover, the last sub-chapter will cover association of virtual reality technology with art and how it widens the already existing possibilities. The first one is a video game called REZ, and the second one is a virtual painting/illustration software, called Quill. Their ties with the promises of these new concepts will also be questioned.

CHAPTER II: CONCEPTUALISATION OF CRISES: MODERNISM

AND POSTMODERNISM

2.1. Crisis of Modernism

Jameson (1991) distinguishes postmodernism from postmodernity (historical phase), and defines it as a cultural dominant rather than a style, a conception which jeopardizes the notion of difference – like Baudrillard's 'zero sum equation' – and by doing so, “allows for the presence and coexistence of a range of very different, yet subordinate features” (Jameson, 1991: 4). Existence of such homogeneity is by no chance

incidental, as it can be traced back to the first half of the 20th century, namely, to the Avant-Garde in general and Dada in particular, and in turn, as the most anticipated figure of the Dadaism, to Marcel Duchamp, since his art – and attitude towards art – is considered as a precursor to postmodernist art (1991: 4). Being considered as the 'kick-starter' of what is known as the expanded arts, he is associated with “crossing of borderlines between media, the interdisciplinary approach that blurs the distinctions between painting, sculpture, artistically designed spaces (“installations” or

“environments”), and object” (Ruhrberg, Honnef, Schneckenburger, Fricke & Walther, 2000: 131). In this respect, I consider Duchamp's reflexive attitude as an early stage of awareness which is symptomatic of an imminent crisis – that of modernism. In fact, his

ready-mades, which also influenced conceptual art on a fundamental level, can be seen as a natural outcome of such crisis. His most famous ready-made sculpture, The

Fountain (1917) can be considered as a prototypical example of conceptual art “because of the way in which it challenged the rules of what a work of art could be” (Malpas, 2005: 31). Moreover, Duchamp's separation of retinal and conceptual is equally important to grasp contemporary artistic discourse today – conceptual art in particular: From too great an importance given to the retinal. Since Courbet, it's been believed

that painting is addressed to the retina. That was everyone's error. The retinal shudder! Before, painting had other functions: it could be religious, philosophical, moral. If I had the chance to take an antiretinal attitude, it unfortunately hasn't changed much; our whole century is completely retinal, except for the Surrealists, who tried to go outside it somewhat. And still, they didn't go so far! In spite of the fact that Breton says he believes in judging from a Surrealist point of view, down deep he's still really interested in painting in the retinal sense. It's absolutely ridiculous. It has to change; it hasn't always been like this. (Cabanne, 1987: 43) By observing his statement, it can be claimed that, although partly, the crisis of modernism seems to be stemming from the fact that comprehension of art – and painting in particular – is reduced to a point where 'retinal' is primary. Accordingly, Kosuth (1991) criticise that the context beyond the visible – or beyond the canvas – is either ignored or put in a secondary/inferior position, thus makes it impossible for the viewer to 'understand' what art really is or might be, thus formalist approach is indeed problematic:

Being an artist now means to question the nature of art. If one is questioning the nature of painting, one cannot be questioning the nature of art. If an artist accepts painting (or sculpture) he is accepting the tradition that goes with it. That’s because the word art is general and the word painting is specific. Painting is a kind of art. If you make paintings you are already accepting (not questioning) the nature of art. One is then accepting the nature of art to be the European tradition of a painting-sculpture dichotomy. (1991: 18)

Within this direction, making an effort to break its bonds with the dichotomy, crisis of modern art – and modernism in general – resulted in what is known as the

deconstruction of formalism and, in turn, gave way to intermediate forms by blurring the line between high-art and low-art (Desmond, 2011: 149). To put it simply, for many critics, postmodernism marks the exhaustion of modernist projects and the belief that art has a single functional purpose or can change the world altogether (Malpas, 2005: 20).

2.2. Crisis of Postmodernism

What McLuhan remarked almost 50 years ago is essential to grasp today's exhaustion as he suggests that “the instantaneous world of electric informational media involves all of us, all at once. No detachment or frame is possible” (McLuhan & Fiore, 2001: 53) and additionally, in the same respect, we should look into the involvement of electronic/new media in arts simply because it is fundamentally related with how we currently

experience arts – and culture: “...development of new media and communication networks, and the collapse of religious and political traditions and beliefs across the world all appear to point towards a culture that has rapidly become fundamentally different from that experienced by earlier generations” (Malpas, 2005: 34).

In the arts, older/modernist modes of representation have been challenged by electronic media, as new media tools such as video and computer, played a major role in creating postmodern conditions which have changed the way art itself is perceived. These conditions can not be perceived well enough, without moving beyond the paradigm of

arts and understanding the effects of technological advancements on the discourse of modernity. Lovejoy (2004) defines this significant change as shifting of cultural

paradigm “from the concept of a single Eurocentric cultural stream dominated by white male privilege to one which recognizes diverse identities and voices interacting in a complex web of ideological and behaviorist associations” (2004: 8). How this shifting occurred is of importance. Within this trajectory, firstly, video – broadcasting – as the ultimate tool for transmission of mediated images (and sound) over long distances, was adopted as a new and powerful consciousness-transforming form of representation, and as of today, it has “become part of an expanded multimedia territory where it is

combined with the interactive capabilities of the computer, as in CD and DVD

production, and in virtual reality and interactive installation works”, nonetheless, in arts, “real break with the paradigm of representation we have followed since the

Renaissance” (2004: 8), is believed to be the digital simulation capabilities of computer: A digital image does not represent an optical trace such as a photograph but

provides a logical model of visual experience. In other words, it describes not the phenomenon of perception, but rather the physical laws that govern it, manifesting a sequence of numbers stored in computer memory. Its structure is one of language: logical procedures or algorithms through which data is orchestrated into visual form. (Legrady, 1990)

What is problematic about this mode of representation “made through logical, numeric based mathematical language structures” (Lovejoy, 2004: 154) or in other words, computer logic, might be the very reason behind the established indifference: “Although both may look like the same on the surface, a digital image may be said to differ from its analogue counterpart in terms of verifiable past and possible future” (Legrady, 1990). Consequently, it becomes a matter of somewhat ambiguous convergence: “Digital

technologies have [thus] become the catalyst for tendencies in the convergence of disciplines, for the universal computer is both a tool and a medium” (Lovejoy, 2004: 157). Moreover, just as video encompassed photographic and cinematic forms of representation, computer superseded video and its previous counterparts. Just like television, the internet allows the audiences to share real or imaginary experiences from great distances while sitting in front of a screen. Nevertheless, participatory experience renders the internet entirely different from television. According to Lovejoy (2004) this is rather a revolution of communication, than of computer but unless we define a direction for it, we can find ourselves in an uncharted territory which presents great challenges:

As a new form without fixed entry points and narratives, the Internet challenges us to explore fundamental aspects of representation that have acquired new meaning and significance such as content and context. While, up to now, we have understood how context can change the meaning of an artwork, the Web creates extremely different conditions where the two are interchangeable. (2004: 223)

This substantial shift is, in my opinion, is the very proof of modernity transforming into postmodernity and, therefore, what seems to be the crisis of the outcome of

postmodernity in the arts, namely the crisis of postmodernism, is presumably this interchangeability, because it puts the separation of content and context (accordingly, of high art and popular culture) in jeopardy on a fundamental level. According to Malpas (2005: 35) there is a dispute over this issue, as for some postmodernist critics, this is an emancipation of artistic practice from the old systems and rules of taste and judgement thereby leads to new forms of critical practice which are able to analyze art with different goals and categories, whereas for other critics who are more critical of

postmodern thought, the loss of these systems of taste makes it impossible to distinguish the good from the bad, the context from the content, the progressive from the

reactionary, and, eventually “leaves us with a culture in which 'anything goes' so long as it is capable of generating profit.” To grasp this contemporary confusion – crisis – better, one could look into the breakdown of the promise of modernism.

Modernism as an aesthetic style could be explained with an emphasis put on the value of being original and innovation in general, hence it was regarded as rather autonomous and this autonomy gave the artists the opportunity to shape their art upon their

individual vision, with almost scientific precision in context and content that every single artist was treated as if she/he was a theoretician on her/his own. Modernist art in this sense was a reflection – and a natural outcome – of modernity and a discourse of originality (Krauss, 1981). Consider, for example, the paintings of Pablo Picasso and Wassily Kandinsky. They were both regarded as modern painters, yet their paintings look entirely different from each other because of their unique theories on art. On the other hand, regardless of their artistic decisions, there is an unmistakable consistency in their art (as well as many other artists who belong to the modernist mode of thought) in terms of the correlation between their content and context. It is as if every autonomous position proposes its own grand narrative individually, therefore constructive in its own respect. On the other hand, demarcation of the transition from modernism to

postmodernism in art still seems like a complex issue since there are various theories as to how, why and when such shifting occurred. Nevertheless, the most viable idea as to

what postmodernism asserts is that it rejects or reacts against modernist values such as authenticity, originality or universality and replace them with irony, parody, chaos or deconstruction, thus creating a complex cultural condition in which criticism is demythologized, the basic proportions of modernism is being liquidated by exposing their fictitious condition: “It is thus from a strange new perspective that we look back on the modernist origin and watch it splintering into endless replication” (Krauss, 1981). As far as I am concerned, it is this ambiguity which results in the aesthetic confusion mentioned above. However I find this confusion fruitful, as it forces us to search for alternatives.

CHAPTER III: A PROPOSAL FOR THE AFTERMATH OF

POSTMODERNISM: ALTERNATIVE CONCEPTS AND THEIR

IMPACT ON ART

3.1. Alternatives In Theory: Metamodernism

Metamodernism, as artist Luke Turner (2015) has pointed out, “is a term that has gained traction in recent years as a means of articulating developments in contemporary

culture.” Prior to its more common recognition in the early 2010s, the term

metamodernism remained somewhat less apparent in a variety of contexts for almost four decades following its first appearance in 1975, coined by American scholar Mas'ud Zavarzadeh in his critical essay The Apocalyptic Fact and the Eclipse of Fiction in Recent American Prose Narratives (Abramson, 2015b). In the essay, through which then-current contemporary – American – fiction is discussed within paradigms concerning the criticism on modernism, Zavarzadeh (1975) uses the term

'metamodernist' – in his own words, for the lack of a better term – to describe the emerging aesthetics within which the dichotomy between 'life' and 'art' is blurred by the fusion of fact and fiction, and indeed “the sharp division between the two does not exist” (Zavarzadeh, 1975: 75). At this point, implying the notion 'the lack of a better term' is of significance since he places 'Metamodernism' somewhat distanced from, yet

in conjuncture with conceptions such as Anti-Modernism, Para-Modernism, and Post-Modernism and, in this regard, he notes:

I am using this term to refer to a cluster of attitudes which have emerged since the mid 1950s. I shall use the term ' metamodernist ' in conjunction with three others to describe various aesthetic and ideational approaches to the art of narrative in the present century. I retain ' Modernist ' for the ideas associated with Joyce, Woolf, Faulkner and their followers. The reaction against their poetics in 1950s by such writers as Kingsley Amis, John Wain and C.P. Snow I label ' Anti-Modernist '. The modified and sometimes radicalized continuation of the Modernist aesthetics in the works of Samuel Beckett, Vladimir Nabokov and others I shall call '

Para-Modernist'. Some critics use the single term ' Post-Modern ' to describe these new developments. However, the term is too general to catch all the nuances

(Zavarzadeh, 1975, p: 75)

As of today, one can find Vermeulen and Van Den Akker's (2010) definition of metamodernism similar in the way it distances itself from postmodernism (and in this case also from modernism) as they argue that “this form of modernism is characterized by the oscillation between typically modern commitment and a markedly postmodern detachment” (Vermeulen and Van Den Akker, 2010). They call this structure

metamodernism. Their proposition suggests that metamodernism “oscillates between a modern enthusiasm and a postmodern irony, between hope and melancholy, between naivete and knowingness, empathy and apathy, unity and plurality, totality and fragmentation, purity and ambiguity.” However, they claim that this is a pendulum swinging between innumerable poles, rather than a balanced oscillation. “Each time the metamodern enthusiasm swings toward fanaticism, gravity pulls it back toward irony; the moment its irony sways toward apathy, gravity pulls it back toward enthusiasm” (Vermeulen and Van Den Akker, 2010). Another more refined view on metamodernism is as follows:

metamodernism is not just a simple reaction to postmodernism and does not remain only at the stage of conflict, of ongoing denial or question about concepts or

theories. Metamodernism is that trend which attempts to unify, to harmonize and to settle the conflict between modern and postmodern by supporting the involvement in seeking solutions to problems and the desirable positioning towards existing

theories, not only combating or questioning them. (Baciu, Bocoş & Baciu-Urzică, 2015)

The relationship between postmodernist and metamodernist discourse can be understood more clearly in the following table:

Table 1. Comparison of postmodernism and metamodernism in view of challenges of the social sciences (Komańda, 2016)

Criterion Postmodernism Metamodernism

Description of

reality Lack of meta-narration; there isonly the individual perception and comprehension of reality

Search for narration based on intersubjectivism

Method Deconstruction Reconstruction

Organisation of social

behaviours

The lack of formal organisation, possible spontaneous and temporary bottom-up organisation

Deliberate, bottom-up and, first and foremost, informal organisation which may turn into other forms

The comparison in the above table should also be explained further, in order to

understand what metamodernism claims to offer against/instead of postmodernism. In the table, we can see a division between postmodernism and metamodernism on the subject of narration, and correspondingly, the methods which these two separate

concepts claim to depend on – deconstruction versus reconstruction. Meta-narrative is a term Lyotard brought into prominence and for Lyotard (1984), because of their

totalizing nature and their tendency towards universal and transcendent truth, they should be approached skeptically:

Simplifying to the extreme, I define postmodern as incredulity toward

metanarratives. This incredulity is undoubtedly a product of progress in the sciences: but that progress in turn presupposes it. To the obsolescence of the metanarrative apparatus of legitimation corresponds, most notably, the crisis of metaphysical philosophy and of the university institution which in the past relied on it. The narrative function is losing its functors, its great hero, its great dangers, its great voyages, its great goal. It is being dispersed inclouds of narrative language elements narrative, but also denotative, prescriptive, descriptive, and so on. Conveyed within each cloud are pragmatic valencies specific to its kind. (Lyotard, 1984)

Here, from this statement, we can clearly get the idea that, metanarration – specific to the modernist project – is now decentralized, or simply deconstructed, and it is not surprising, as mentioned earlier, that deconstruction is playing a central role in postmodernism. On the other hand, the main concern of metamodernist sensibility, as previously outlined, is to reclaim what has been deconstructed – as if it hopes to fix it – without committing a total decline of the traits of postmodernism – the oscillation. Additionally, searching for a narration based on intersubjectivism is of essential value as to understand the promise of metamodernism, because intersubjectivity, in general sense, is an interpersonal phenomena, a shared understanding “that helps us relate one situation to another” (Bober & Dennen, 2001), moreover, it is also “central to everyday functioning; only through shared meanings can we work and build knowledge together” (Bober & Dennen, 2001). In my opinion, this mode of thought, by taking empathy seriously, can be regarded as a rather naive one, compared to the harsh, deconstructive nature of the postmodern condition, and this contrast, although not so conclusively, illustrates the claimed difference between the postmodern and the metamodern to a certain degree.

3.2. Alternatives in Theory: Common Grounds

It is also possible to see that the definition of Altermodernism (as a manifestation embedded in the context of 2009 Tate exhibition with the same name: Altermodern; curated by Bourriaud himself) has a strong resemblance to the notion that

metamodernism is an 'oscillation.' Nicolas Bourriaud (2015a) suggests:

Altermodernism can be defined as that moment when it became possible for us to produce something that made sense starting from an assumed heterochrony, that is, from a vision of human history as constituted of multiple temporalities, disdaining the nostalgia for the avant-garde and indeed for any era - a positive vision of chaos and complexity. It is neither a petrified kind of time advancing in loops

(postmodernism) nor a linear vision of history (modernism), but a positive experience of disorientation through an art-form exploring all dimensions of the present, tracing lines in all directions of time and space. (Bourriaud, 2015a) Mutuality in the 'dynamics' of metamodernism and altermodernism, however, is not exclusive and, it is not surprising to come across similar attitudes in the cluster of definitions regarding the alternatives and/or (claimed to be) successors to

postmodernism. In this respect, another major approach in the cultural landscape is Alan Kirby's Digimodernism – which is, in other words, digital modernism. Kirby (2009), by situating the digitization as default, argues the traits of digimodernism:

There are various ways of defining digimodernism. It is the impact on cultural forms of computerization (inventing some, altering others). It is a set of aesthetic

characteristics consequent on that process and gaining a unique cast from their new context. It’s a cultural shift, a communicative revolution, a social organization. The most immediate way, however, of describing digimodernism is this: it’s a new form of textuality. (2009: 50)

Nevertheless, this new form of textuality refers to a complex set of relationships between digimodernist and postmodernist texts. According to Kirby, peculiarity of

digimodernist textuality lies somewhere deeper than that of postmodernist whose function is to represent “a textual content or a set of techniques employed by an antecedent author, embedded in a materially fixed and enduring text” whereas the former “describe how the textual machine operates, how it is delimited and by whom, its extension in time and space, and its ontological determinants” (Kirby, 2009: 51). These 'deeper traits' of digimodernist text are in fact a number of dominant features which, in Kirby's definitions, are onwardness, haphazardness, evanescence,

reformulation and intermediation of textual roles, anonymous, multiple and social authorship, the fluid-bounded text and electronic-digitality (2009: 52-3). Traits of the digimodernist and the metamodernist intersect and, often at times, complement each other. Digimodernist text, for Kirby – unlike postmodernist text – “seems to have a start but no end” (2009: 52). The claim is that onwardness is evident and its traits can be found in such domains as online blogs, thus, referring to the digimodernist textuality found in the blogs, he explains:

It is a textuality existing only now, although its contemporary growth also

guarantees the continued life of its past existence (archived entries): it’s like some strange entity whose old limbs remain healthy only so long as it sprouts new ones. (Kirby, 2009: 112)

Likewise, Vermeulen and Van Den Akker (2010) defines metamodern 'wo/man' as someone whose destiny is “to pursue a horizon that is forever receding” and, further claim that “metamodernism moves for the sake of moving, attempts in spite of its inevitable failure; it seeks forever for a truth that it never expects to find.” Endless scrolling feature implemented in a variety of web pages (i.e. Tumblr blog feed) is a good example of onwardness in practice.

Ambiguity in this sense is a major trait in all cases and, consequently, it causes the haphazardness mentioned above: The qualities upon which the text is built are as yet unknown because the future progress of the text is undecided, and this coincidental situation creates an illusory effect. One might consider it as power or freedom, whereas another may find it futile. “If onwardness describes digimodernist text in time,

haphazardness locates in it the permanent possibility that it might go off in multiple directions: the infinite parallel potential of its future textual contents” (Kirby, 2009: 52). It seems that haphazardness is also present in metamodernist domain and sets the ground for justification of exploration. Emphasizing its progress rather than its promise, Turner (2015) defines the discourse of metamodernism as “descriptive rather than prescriptive; an inclusive means of articulating the ongoing developments associated with a structure of feeling for which the vocabulary of postmodern critique is no longer sufficient, but whose future paths have yet to be constructed.” Bourriaud (2015b) in his manifesto, also remarks a new type of globalized perception and “a cultural landscape saturated with signs” that artists traverse and thus “create pathways between multiple formats of expression and communication” (Bourriaud, 2015b: 253). In his 2012 book, Approaching The Hunger Games trilogy: A literary and cultural analysis, Tom

Henthorne explains:

The open-endedness that marks many contemporary texts also seems to contribute to their haphazardness: because they lack defined boundaries, digimodernist texts have the potential to continually grow and change, reflecting new ideas and

circumstances. It is not that digimodernist texts lack structure but rather that the structure itself is subject to change....Although some readers may find such haphazardness disconcerting or even troubling, to others it increases the sense of verisimilitude since life itself can be chaotic and develop in way that cannot be easily predicted (Henthorne, 2012: 147)

Open-endedness is treated as a major property in all cases above and requires further explanation, especially in terms of its practice. At this point, the role of authorship in digimodernist text appear significant as it is claimed to have become “multiple, almost innumerable and is scattered across obscure social pseudocommunities” (Kirby, 2009: 52) Henry Jenkins (2006) gives one of the adequate examples of how these

pseudocommunities function, which, in this case, fandom in online discussions, since convergence allows 'users' or 'fans' (or, in a broader/digimodernist sense, readers of digital text) to socially produce, circulate and revise the television meanings and become 'a part' of the text:

Within moments after an episode is aired, the first posts begin to appear, offering evaluations and identifying issues that will often form the basis for debate and interpretation across the following week. Because this process is ongoing, rather than part of focused and localized interview sessions, computer net discourse allows the researcher to pinpoint specific moments in the shifting meanings generated by unfolding broadcast texts, to locate episodes that generated intense response or that became particularly pivotal in the fans' interpretations of the series as a whole. (Jenkins, 2006: 118)

Hence, the possibilities for active participation of the audience to the open-ended text also tends to be an illustration of how Vermeulen and Van Den Akker summarize metamodernism by defining metamodernist sensibility as “rhizomatic rather than linear, open-ended instead of closed. It should be read as an invitation for debate rather than an extending of a dogma” (Vermeulen & Van Den Akker, 2010). Accordingly, in the practice of art, reducing an artwork to a presence of a single final object is no longer sufficient since it is subjected to fragmentation: A work of art, now “consists of a significant network whose interrelationships the artist elaborates, and whose

notion of 'artist as an autonomous master of his/her product' (Bourdieu, 1984: 3) has diminished, if not disappeared entirely. In other words, it is the process of creating an artwork through participation. Participation on the level of interaction with an artwork is by no means something new, yet creating the whole body of an artwork exclusively through participation is something else.

On the other hand, these contemporary tendencies are not exclusive to new media texts, but, for instance, also to a traditional discipline which, in this case, is painting. While remaining relatively conventional in practice and seemingly distant from those more dependent on digital mediums, Stuckism and Remodernism (the two are in fact written by same individuals and fundamentally interrelated) also make a good example of 'the yearning for the new.' Ontologically, they have a similar pattern with metamodernism, digimodernism and altermodernism in their claim of searching for something new, despite Remodernism/Stuckism embraces a rather strict paradigm and dictates one particular art-making discipline over another: “Artists who don't paint aren't artists” (Childish & Thomson, 1999). Behind this philosophy, two British artists reside: Billy Childish (real name: Steven John Hamper) and Charles Thomson announced The Stuckist Manifesto, a harsh criticism on tendencies in contemporary art at every level, addressing the practice of painting as the source of the authenticity in art, they

presuppose that painting “engages the person fully with a process of action, emotion, thought and vision, revealing all of these with intimate and unforgiving breadth and detail” (Childish & Thomson, 1999). This engagement is claimed to be crucial in its

purest sense. Thus it gives way to the pronounced detachment from postmodernism and renders conceptual art overdue:

Post Modernism, in its adolescent attempt to ape the clever and witty in modern art, has shown itself to be lost in a cul-de-sac of idiocy. What was once a searching and provocative process (as Dadaism) has given way to trite cleverness for commercial exploitation. The Stuckist calls for an art that is alive with all aspects of human experience; dares to communicate its ideas in primeval pigment; and possibly experiences itself as not at all clever! (Childish & Thomson, 1999)

In its very essence, Remodernism's motivation seems to be stemming from the loss of spirituality, or in other terms, the loss of the 'holistic' vision in contemporary culture in general. The proof of this claimed-deadlock is also evident in the title 'stuckism' as it was said to have derived from arguments between Billy Childish and his former girlfriend, one of the most famous British contemporary artists and a member of the infamous Young British Artists, Tracey Emin. Thomson, in this regard, notes that: On more than one occasion he (Billy Childish) had recited part of one of his poems

to me, which recorded Tracey's invective that he was 'stuck' with his art, poetry and music. Apparently to make sure he didn't miss her drift, she reinforced it with: 'Stuck! Stuck! Stuck!' (Thomson, 2004)

The controversy revolving around the contemporary art world -and around Young British Artists as a triggering point in the case of stuckism- gained publicity when Stuckists held a demonstration on the opening of the Stuckism International Gallery. Figure 1 shows the demo and the coffin with the slogan 'The Death of Conceptual Art' written on it, along with pictures of Damien Hirst's infamous shark sculpture The Physical Impossibility of Death in the Mind of Someone Living (1991) and Tracey Emin's My Bed (1998) embedded on top of the coffin which was to be left in front of the famous White Cube Gallery – which is on the same street with the Stuckism

International Gallery – on the day of July 25th, 2002.

Figure 1. Stuckist demo outside White Cube Gallery.

On the other hand, the struggle between the Stuckists and the contemporary art world is not an argument only about formal aesthetics (which in Stuckists' case is their position as an “international art movement for contemporary figurative painting with ideas”), but also a political one since they relentlessly attacked foundations like Tate Modern, Saatchi Gallery, and Turner Prize: “Brit Art, in being sponsored by Saatchi, mainstream conservatism, and the Labour government, makes a mockery of its claim to be

At first glance, it might appear that Remodernism/Stuckism fails to fulfill its promise to promote something 'new' due to its harsh nature and loosely-compulsive dictation. But if one digs deeper into its fundamental traits, she/he can see that a certain amount of oscillation relevant to other 'new' forms of modernism is present: “Stuckism is anti 'ism.' Stuckism doesn't become an 'ism' because Stuckism is not Stuckism, it is stuck!”

(Childish & Thomson, 1999). It is a perfect example of what Vermeulen and Van Den Akker (2010) calls “a typically modern commitment and a markedly postmodern detachment.” In fact, metamodernist discourse and Remodernism share a common ground where a new type of sensibility lies: While remodernism identifies itself with “a new spirituality in art” (Childish & Thomson, 2000), metamodernism situates itself closely associated with a new type of romanticism: “...Romantic sensibility has been expressed in a wide variety of art forms and a broad diversity of styles, across media and surfaces” (Vermeulen and Van Den Akker, 2010). Romanticism here refers to a type of artistic sensibility which resembles the 'original' romanticism originated toward the end of the 18th century, in other words the feelings and the emotions of the artist – once again – important within the context of the work she/he creates. For instance, paintings of Scottish painter Peter Doig has been said to contain ideas associated with

metamodernism or directly regarded as a metamodern painter in several resources (Kadagishvili, 2013; Vermeulen & Van Den Akker, 2010). How art critic Jonathan Jones describes Doig's art is as follows:

Doig’s art will last because it embodies a unique, beguiling vision. His paintings take the mind to new places, far-off places, forgotten places. He paints landscapes but it would make no sense to call him a landscape artist. Rather, like the early 20th century metaphysical painter Giorgio de Chirico, he creates spooky fictional places

inhabited by bizarre outcasts.... Doig is the painter of the global age, a traveller without a destination, between cultures, between jobs, looking for paradise and finding a prison on the horizon. His art portrays the dreams we share, the freedoms we crave... (Jones, 2015)

Here, when Jones defines Doig as the painter of the global age, a traveller without a destination, a romantic individal who is looking for a paradise, he attaches a somewhat melancholic yet conscious value to Doig's art, a kind of melancholy and awareness which creates the oscillation metamodernism asserts, as it fulfills the inclination that “Metamodernists are as aware of political, economic, climatological, and other forms of chaos as is anyone else, but they choose to remain optimistic and to engage their communities proactively even when and where they believe a cause has been lost” (Abramson, 2015a). On the other hand, Doig's determination is claimed to match with an early 20th Century painter with his way of soul-searching vision and this claim then refers to what Stuckist Manifesto notably declares: “Painting is mysterious. It creates worlds within worlds, giving access to the unseen psychological realities that we inhabit” (Childish & Thomson, 1999).

Also, the notion of New Old Masterism by art historian Donald Kuspit is as distinctive in terms of its modality of fusion of old and new. Unlike Stuckism, New Old Masterism does not impose necessary amateurism. Yet, it promotes adoption of the techniques of Old Masters and transcend them into new meanings as a way of creating a fresh

contemporary understanding, and on the other hand, like Stuckism, New Old Masterism is by all means critical about conceptualism and minimalism – it is also possible to find the traces of the oscillation (as in metamodernism) between the old and the new:

The New Old Masterism [then] restores everything Conceptualism devalued and repudiated. It struggles to repair the serious connection to tradition broken by avant-gardism. At the same time, it does not discard avant-garde aesthetics, but integrates it with Old Master aesthetics. The New Old Masterism involves a return to the personal craft of object making, and, more crucially, to the human object and human condition, art's perennial themes. (Kuspit, 2006)

Though being rather strict – with the absence of open-endedness, multiple authorship, haphazardness or electronic-digitality – compared to former '-isms' explained above, this brief example of paradigm shift within the conventions of so-called fine arts and/or painting is also symptomatic to our current cultural climate today, at least in terms of their 'romantic' departure.

However, it should be noted that, despite having noticable amount of commonalities among new conceptions, contemporary experience in art practice is far from conclusive. Within this context, such complexity can be portrayed as:

This is actually an inquiry into the mentality of contemporary society. Attempting to define the current cultural climate is difficult at best, but it also raises concerns about society’s aspirations. Having journeyed through modernism and postmodernism, we wish to travel to the theory beyond, before this elusive new culture has even had time to solidify. In fact, today’s ism, if indeed there is one, appears to be an amalgamation of previous theories. (Lyons, 2015)

What remains is that these contemporary ideas and movements seem to coexist and can not be interpreted outside the context of their relationship with each other. With their complex, progressive nature, they all go hand in hand when it all comes down to approaching existing structure critically and, regardless of the medium, these attributes eventually dissolve into a ubiquitous pattern which seems to be in search for an

a hankering after modernist notions of artistic practice making a difference to the society within which it circulates” (Downey, 2007). One of the very insightful comments about this 'hankering' perhaps belongs to Manovich, as he explains: I am not advocating a revival of modernism. Of course we don't want to simply

replay Mondrian and Klee on computer screens. The task of the new generation is to integrate the two key aesthetic paradigms of the twentieth century: (1) belief in science and rationality, emphasis on efficiency and basic forms, idealism and heroic spirit of modernism; (2) skepticism, interest in “marginality” and “complexity,” deconstructive strategies, baroque opaqueness and excess of post-modernism (1960s-). At this point all the features of the second paradigm became tired clichés. Therefore a partial return to modernism is not a bad first step, as long as it is just a first step towards developing the new aesthetics for the new age. (Manovich, 2002) At first glance, it might be mistaken that all of these assumptions resolve into a 'mixed bag' of consecutive theories, which might turn into a haystack of indistinguishable thoughts, but the reality is not as complicated. In this regard, the following chapter will investigate if such conditions, one way or another, exist.

CHAPTER IV: CASE STUDIES

4.1. Computer Code and The New Aesthetics as Index: A Glimpse of Future and Now

Manovich (2002) made a definition for a generation of artists who emerged in the late 90s, namely, the Flash Generation (deriving the name from the software Macromedia Flash – now owned by Adobe); artists who created their own cultural systems by writing their own software codes instead of using samples derived from the commercial media – as their 'modern' predecessors did: “Thirty years of media art and post-modernism have inevitably led to a reaction. We are tired of always taking existing media as a starting point. We are tired of being always secondary, always reacting to what already exists” (Manovich, 2002). He explains the historical trajectory by putting three distinguishable artist figures in picture. First one is the romantic modernist artist who – as a genius – creates art right from scratch, imposing the 'inner-self' and her/his imagination on the world – which is now a thing of the past. Next is the new figure of a – post-modern – media artist who rejects the notion that possibility of an original, unmediated vision of reality exists:

Their subject matter is not reality itself, but representation of reality by media, and the world of media itself. Therefore, these media artists not only use media

technologies as tools, but they also use the content of commercial media.... The media artist is a parasite who lives at the expense of the commercial media – the

samples from/subverts/pokes at commercial media can ultimately never compete with it. Instead of a feature film, we get a single scene; instead of a complex computer game with playability, narrative, AI, etc., we just get a critique of its iconography. (Manovich, 2002)

Finally, a type of artist, which is also relevant to our study, emerges: The software artist who makes her/his mark on the world by writing her/his original code, regardless of what this code does at the end. Software artist is claimed to have steered her/his art-making process away from applying figuration and using the language of commercial media, to re-using the language of modernist abstraction and design: in other words, the new romantic who reappropriates computer as a programming machine – like the empty canvas of the modernist – instead of computer as a media – collage – machine, and in this respect, what these new romantics are said to have offered was a new type of sensibility which is, in Manovich's (2002) term, soft, elegant, restrained and smart: “If images of the previous generations of media artists, from Nam June Paik to Barbara Krueger, were screaming, trying to compete with the intensity of the commercial media, the new data artists such as Franceschini/Merg whisper in our ears” (Manovich, 2002). Significance here is that, over a decade ago, long before the so-called fresh,

contemporary alternative formations of postmodernism were even conceptualized, indications of a certain discomfort towards existing cultural and political structure became apparent, as in the case of those Manovich described as new romantics; they had already existed long before the conception of neoromanticism in metamodernism emerged (Vermeulen & Van Den Akker, 2010).

enthusiasm of the new romantic with that of the prolific Internet Artist of the 1990s and late 1980s, since they both regard software as their medium but implementation of software by the former resembles the enthusiasm of a modern artist (the act of code writing – subjective view of the world) whereas the latter is mainly concerned with using the software – also as a programmer – almost as a self-referential tool for media criticism (Manovich, 2002). Nonetheless, if we rule out the contextual differences of these two tendencies, we can see that they were both criticized in the same manner, due to their common reliance on computer language:

For those who do not support it, net art is often thought to lack the craft and direct impact of work in painting and sculpture by privileging commercial tools, veering too close to graphic design, or exploiting cheap, 'whizz-bang' programming tricks (to which authentic, meaningful art should naturally be opposed). Furthermore, net practices such as software art do not align with existing gallery, museum and

discursive systems, and these institutions often want to differentiate themselves from commercial fields. (Greene, 2004: 12)

This is the proof that software, plausible or not, has become one of the major

distinguishing features of the discourse of contemporary art – and thus of contemporary culture – since mathematical abstraction in the visual arts has been dramatically

accelerated by computers (Lovejoy, 2004: 152). However, even further, what we experience today is a kind of prolific transcendence of computer language which exceeds the limits of artistic (or any relevant practice) and evolves into an aggressive, ubiquitous reality.

First, it should be noted that the subject that will be examined in this part, basically, is neither an artwork nor an art movement, but rather an index which is consisted of the

excessive outcomes of our ever-growing relationship with humans and

computers/digital tools, or simply, the visual clues of audiovisual language/logic of computer code merged into material life or vice versa, an archive of incarnations. On the other hand, it is a descriptive term which can applied on these incarnations that result in an ambiguous aesthetic phenomenon.

To be understood more properly, paradigms related to this phenomenon furthermore requires their corresponding patterns of aesthetic concepts to be seen, despite their theoretical negotiations with somewhat loose uncertainty – ironically, this uncertainty roughly refers to an infinite number of 'romantic' possibilities – ubiquitous realities. Here, characteristics of one particular formation called The New Aesthetics fits into this pattern. How London based artist James Bridle (the one who coined the term as a concrete definition) defines The New Aesthetic is worthy of note as he claims it to be the “new ways of seeing the world, an echo of the society, technology, politics and people co-produce them” (Bridle, 2011a). It can be found in the “material” that he has been collecting – and exhibiting – since 2011, and he further suggests that “The New Aesthetic is not a movement, it is not a thing which can be done. It is a series of artefacts of the heterogeneous network, which recognises differences, the gaps in our distant but overlapping realities” (Bridle, 2011a). Bridle's Tumblr feed is a massive collection of exclusively collected imagery, a resourceful documentation which aims to exhibit the “evidence of the increasingly symbiotic relationship between man and machine, revelling in the often-unexpected beauty that arises when the human-digital

divide is ruptured” (Turner, 2012). For Bridle, trying to grasp what happens in the realm of snapshots, online videos, screen captures, still images and alike, is not only

consequential but also inevitable:

It is impossible for me … not to look at these images and immediately start to think about not what they look like, but how they came to be and what they become: the processes of capture, storage, and distribution; the actions of filters, codecs,

algorithms, processes, databases, and transfer protocols; the weight of data centers, servers, satellites, cables, routers, switches, modems, infrastructures physical and virtual; and the biases and articulations of disposition and intent encoded in all of these things, and our comprehension of them! (Bridle, 2013)

In addition to this, Bourriaud's rather romantic notion of 'artist as cultural nomad' is based on the assumption that nomadism, as a way of learning about the world, “enshrines specific forms, processes of visualisation peculiar to our own epoch” (Bourriaud, 2015) and this formulation of nomadism, in turn, can be considered analogous to Bridle's enthusiasm towards 'objects' of the New Aesthetics:

I started noticing things like this in the world. This is a cushion on sale in a furniture store that's pixelated. This is a strange thing. This is a look, a style, a pattern that didn't previously exist in the real world. It's something that's come out of digital. It's come out of a digital way of seeing, that represents things in this form. The real world doesn't, or at least didn't, have a grain that looks like this. But you start to see it everywhere when you start looking for it. It's very pervasive. It seems like a style, a thing, and we have to look at where that style came from, and what it means, possibly. Previously things that would have been gingham or lacy patterns and this kind of thing is suddenly pixelated. Where does that come from? What's that all about? (Bridle, 2011b)

Obviously, it is not by chance to see such modality pervasively while the characteristic of the new system of communication is based on digitization and networked integration of multiple communication modes, and all cultural expressions are subsumed by this new system of communication itself (Castells, 2011: 405). Within this system, as can be seen in Figure 2, coming across this pixelated imagery and objects – intentional or not –

more often as a natural outcome of the blurriness between the real and the digital, the physical and the virtual, the human and the machine (Bridle, 2012) can be interpreted as a major consequence of digitized electronic production, distribution and exchange of signals (Castells, 2011: 406). Based on this phenomena, one explanation as to reveal the intention behind the effort in Bridle's blog is as follows:

The particular sense this collection documents is a concerted effort at realizing and acknowledging the digital nature not only of the immaterial 'space' produced by computers and algorithmic systems (the results of digital automation), but the transfer of these autonomously produced artifacts into the physical realm. The automated machine labor revealed by this project is a symptom of the emergent autonomous production it documents, revealing the paradox of automation, labor, and value production: the cultural, historical, and aesthetic ruptures between automation and the (traditional) conceptual mappings of human society. (Betancourt, 2013)

Accordingly, visual representation of integration of 'the virtual' into 'the real' is not primarily “concerned with beauty or surface texture. It is deeply engaged with the politics and politicisation of networked technology, and seeks to explore, catalogue, categorise, connect and interrogate these things” (Bridle, 2013). Furthermore, such complex engagement requires close attention because “it is ferociously attached to modish, passing objects and services that have short shelf-lives” (Sterling, 2012), objects which compels one to be “involved with some contemporary, fast moving technical phenomena” (Sterling, 2012). The Tumblr feed mentioned above is an

enormous collection of the contents related to this phenomenon and a clear indication of what Berry (2012) describes as the mediation of our experience (and engagement with the world) by digital technologies and computation. The consistency of the blog, for the most part, stems from the fact that it functions as an archive of collected/re-posted technology-related material rather than a collection of personal opinions or self-promotional content. The archive is consisted of several overlapping categories of material, such as, autonomously generated images that contain markers of the digital such as glitches of various types (encoding errors, algorithmic misidentifications of faces, pixelation / scan lines / digital noise, etc.), physical constructions employing signifiers of digital forms (blocky pixel-imitating construction, scanlines, etc.),

translations of digital forms into a visual style (QR codes, low resolution bitmaps, etc.), dynamic, interactive data visualizations (art installations, biometric scanners, and augmented reality) (Betancourt, 2013). According to Betancourt (2013), “these groupings are neither exhaustive nor mutually exclusive. While there are points of

contact and degrees of overlap between them, they articulate general tendencies in the formal appearance of digital technology, and document an apparent paradox: immaterial physicality.” This paradox is, indeed, said to be the very essence of the new aesthetics, immaterial physicality, as an illusory feature, renders the 'aura' of information

perceivable and almost physically present but, at the same time, lessens the effect of immediate engagement:

Objects collected by Bridle reflect digitally-derived features displaying the existing capacities (both current and historical) of digital technology: the illusion they produce is one where what was immaterial, penumbral, crystalizes from the air into solid, tangible form: reification becomes realization... (Betancourt, 2013)

According to Chun (2005), “software and ideology fit each other perfectly because both try to map the material effects of the immaterial and to posit the immaterial through visible cues” (2005: 44) and if this is the case, then it can be speculated that these 'objects' of immaterial physicality, or in other words, the objects of the new aesthetics, function as a major visual cue of our contemporary ideology and this might explain why we see such modality pervasively. Respectively, this pervasiveness makes it possible to approach new -isms from the perspective of the new aesthetics, and vice versa.

4.2. Metamodern Art: Turner, Rönkkö & LaBeouf

Having said that, one particular art project relevant to the issue was realized in 2015 titled #INTRODUCTIONS, a multi-layered collaboration arranged by self-proclaimed metamodern artists Luke Turner, Nastja Säde Rönkkö and Hollywood star Shia

perception of artwork/text, and ultimately gives us the insight into the ways in which the meaning of the text is reproduced within these new discourse. The project was to serve as the pivotal part of Fine Art Bachelors' graduation show at Central St. Martins and consisted of a set of 36 half-minute long films performed by LaBeouf against a green screen, as seen in Figure 3.

Figure 3. LaBeouf against the green screen in the raw footage of #INTRODUCTIONS

For the films, the students were asked by the artists to send a piece of text to introduce each of their graduation works, to be presented during a live stream broadcast at the degree show opening. They were then tasked with filling the green screen with

the graduating students and the artists in the first place. Moreover, the boundaries of the text become more blurry as LaBeouf, Rönkkö and Turner released the raw footage under non-commercial creative commons license on Vimeo and made it available for the public to use it as they see fit. From that moment on, as seen in Figure 4, the footage quickly went 'viral, ' and dozens of new material were generated from it:

It seems that LaBeouf and his collaborators knew very well what they were doing. The video art, in this case, wasn’t just what LaBeouf performed or what the Central Saint Martins students created from it — in the end, the performance art also included a whole Internet full of inspired, witty, and impressively quickly made videos. (Pogue, 2015)

Figure 4. Manipulated footage of LaBeouf at the graduation show, mimicking a salesman on a TV sale commercial