T.C.

GAZİ UNIVERSITY

GRADUATE SCHOOL OF EDUCATIONAL SCIENCES DEPARTMENT OF FOREIGN LANGUAGES EDUCATION

ENGLISH LANGUAGE TEACHING PROGRAM

FLIPPED WRITING CLASS MODEL WITH A FOCUS ON BLENDED LEARNING DOCTORAL DISSERTATION Emrah EKMEKÇİ ANKARA May, 2014

T.C.

GAZİ UNIVERSITY

GRADUATE SCHOOL OF EDUCATIONAL SCIENCES DEPARTMENT OF FOREIGN LANGUAGES EDUCATION

ENGLISH LANGUAGE TEACHING PROGRAM

FLIPPED WRITING CLASS MODEL WITH A FOCUS ON BLENDED LEARNING

DOCTORAL DISSERTATION

Emrah EKMEKÇİ

Supervisor: Assoc. Prof. Dr. İskender Hakkı SARIGÖZ

ANKARA May, 2014

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

Several people deserve my deepest gratitude for contributing to this lengthy and hard process. First and foremost, I would like to thank my supervisor, Assoc. Prof. Dr. İskender Hakkı SARIGÖZ for his invaluable guidance and support throughout the process. This process would not have been completed without his understanding and patience.

I would like to express my gratitude to the other members of the committee, Assoc. Prof. Dr. Arif SARIÇOBAN from Hacettepe University and Assist. Prof. Dr. Kadriye Dilek AKPINAR from Gazi University for their constructive feedback and advice in the dissertation progress meetings.

I also wish to thank Assoc. Prof. Dr. Paşa Tevfik CEPHE for encouraging me and easing the process from the very beginning of this journey.

The instructors of the School of Foreign Languages at Ondokuz Mayıs University also deserve my thanks for their contributions to the study. Special thanks go to my distinguished colleague, Dr. İsmail YAMAN who has never hesitated to support and help me in almost every phase of the study.

Sincere appreciation is extended to my dear students in the ELT Preparatory classes for their contributions to the treatment process.

Last but not least, I would like to thank my wife Öznur EKMEKÇİ for her never-ending support, encouragement and love throughout the process. My beloved daughter, Neva Nur, also deserves appreciation for granting her time which she could spend with me. Finally, many thanks from the deepest corner of my hearth go to my mother for her priceless prayers and to my late father who is somewhere in heaven.

FLIPPED WRITING CLASS MODEL WITH A FOCUS ON BLENDED LEARNING

ABSTRACT EKMEKÇİ, Emrah

Doctoral Dissertation, Department of English Language Teaching Supervisor: Assoc. Prof. Dr. İskender Hakkı SARIGÖZ

May - 2014, 221 pages

Flipped learning is a pedagogical approach in which the typical lecture and homework elements of a course are reversed. It has been recently recognized as an alternative instructional strategy. In flipped learning, classrooms are transformed into the interactive and dynamic places where the teacher guides the students and facilitates their learning.

The point of departure of this study is to develop a new instructional model for EFL writing classes in order to compensate for the hardship and complexities of the foreign language writing skill, and students' negative attitudes toward it. To this end, flipped writing class model is employed during the fall semester of 2013-2014 academic year in an ELT prep class in School of Foreign Languages at Ondokuz Mayıs University. The population of the study consists of students attending ELT Preparatory Classes at School of Foreign Languages. Two randomly selected groups constitute the experimental and control groups of the study. Both quantitative and qualitative data collection instruments are employed in the study. The quantitative model of the study is a pre- and post-test true experimental design with a control group. As the quantitative data collection methods, the pre- and post tests, Argumentative Paragraph Rubric, ICT literacy survey, and Flipped Writing Class Attitude Questionnaire are used. As for the qualitative data, a semi-structured follow-up Interview is employed. The pre-test is conducted for both groups before the treatment process, and the results indicate no statistically significant difference between them. After the pre-test, ICT literacy survey is administered to determine the students' tendencies towards and interests in the technology use. The students in the experimental group are introduced the CMS (Edmodo) which provides them to follow the course requirements and to see the shared links by the teacher. The experimental group consisting of 23 ELT prep students are instructed for fifteen weeks (one semester) through Flipped Writing Class Model in which the typical lecture and homework elements of a course are reversed. The students

view the teacher-created videos at home as homework and in-class time is devoted to exercises and paragraph writing practices. The control group consisting of 20 ELT prep students, on the other hand, are instructed through traditional lecture-based writing class. The same syllabus prepared by the researcher and which is in line with the pre-selected coursebook is followed by both groups. The writing lessons of both groups are offered by the researcher himself. At the end of the fifteen weeks of instruction, both groups are given the same post-test to determine the difference between and with-in the groups. Independent and paired samples t-tests are carried out for the analyses of the data gathered through the pre-and post tests. The results indicate that there is a statistically significant difference between the experimental and control groups in terms of their writing performances. In other words, the students in the experimental group outperform the students in the control group after the treatment process. In addition, the most improved dimension on behalf of flipped writing class is found to be in the Relevance and Content, which is followed by the dimensions; Organization and Structure, Overall, Lexical Range & Word Choice, Grammar & Sentence Structure, and Mechanics respectively. In order to get an idea about the students' attitudes towards Flipped Writing Class Model, Flipped Writing Class Attitude Questionnaire, which is developed and piloted by the researcher, is administered to the experimental group's students. The frequency analysis of the students' responses reveals that the great majority of the students hold positive attitudes towards Flipped Writing Class Model. These positive results are verified with the semi-structured interview which is analysed by categorizing the students' responses. The frequency analyses overlap with the percentages of the categorized responses of the students.

To conclude, the findings of both qualitative and quantitative data indicate that the Flipped Writing Class Model is more effective than traditional lecture-based writing class in terms of improving students' writing proficiency. In addition, students hold positive attitudes towards flipped writing class. It is believed that Flipped Writing Class Model can be employed in EFL and ESL contexts, which may resolve the problems of boredom, hardship, and complexities of writing skill together with the negative attitudes towards writing.

Keywords: Flipped learning, flipped writing class, flipped classrooms, blended Learning.

HARMANLANMIŞ ÖĞRENME ODAKLI TERSTEN YAPILANDIRILMIŞ YAZMA SINIFI MODELİ

ÖZ

EKMEKÇİ, Emrah

Doktora Tezi, İngiliz Dili Eğitimi Bilim Dalı Danışman: Doç. Dr. İskender Hakkı SARIGÖZ

Mayıs - 2014, 221 sayfa

Tersten yapılandırılmış öğrenme, bir dersin geleneksel ders anlatımı ve ödev kısımlarının yer değiştirildiği pedagojik bir yaklaşım şeklidir. Bu öğrenme şekli son zamanlarda oldukça rağbet gören alternatif bir öğretim stratejisidir. Tersten yapılandırılmış öğrenmede, sınıflar; öğretmenin öğrencilere yol gösterdiği ve öğrenmelerini kolaylaştırdığı etkileşimli ve dinamik yerlere dönüştürülür.

Bu çalışmanın çıkış noktası; yabancı dilde yazma becerisinin zorlukları, karmaşıklığı ve öğrencilerin bu beceriye karşı olan olumsuz tutumlarını telafi etmek için EFL yazma sınıflarında yeni bir öğretim modeli geliştirmektir. Bu amaçla; Ondokuz Mayıs Üniversitesi Yabancı Diller Yüksekokulu'nda öğrenim gören bir grup İngiliz Dili Eğitimi hazırlık sınıfı öğrencisine 2013-2014 akademik yılı güz dönemi boyunca tersten yapılandırılmış yazma sınıfı modeli uygulanmıştır. Çalışmanın evrenini Yabancı Diller Yüksekokulu'nda İngiliz Dili Eğitimi hazırlık sınıflarına devam eden öğrenciler oluşturmaktadır. Deney ve kontrol grupları rastgele seçilmiş öğrencilerden oluşturulmuş ve çalışmada hem nicel hem de nitel veri toplama araçları kullanılmıştır. Araştırma modeli olarak öntest-sontest kontrol gruplu gerçek deneme modeli kullanılmıştır. Nicel veri toplama araçları olarak araştırmada; ön ve son testler, tartışmacı paragraf puanlama rubriği, bilgi ve iletişim teknolojileri okuryazarlığı anketi ve tersten yapılandırılmış yazma sınıfı tutum ölçeği kullanılmıştır. Nitel veri toplama aracı olarak ise; yarı yapılandırılmış görüşme tekniği kullanılmıştır. Tersten yapılandırılmış yazma sınıfı uygulama süreci öncesinde, her iki gruba öntest uygulanmış ve öntest sonuçlarına göre iki grup arasında istatistiksel olarak anlamlı farkın olmadığı bulunmuştur. Öntest sonrasında deney grubundaki öğrencilerin teknoloji kullanım alışkanlıkları ve eğilimlerini belirlemek amacıyla bilgi ve iletişim teknolojileri okuryazarlığı anketi uygulanmıştır. Deney grubundaki öğrencilere; öğretmenin paylaştığı linkleri görebilmeleri ve ders gereksinimlerini takip edebilmeleri amacıyla Ders Yönetim Sistemi (Edmodo) tanıtılmıştır. İngiliz Dili Eğitimi hazırlık sınıfında öğrenim gören 23

öğrenciden oluşan deney grubuna on beş hafta (bir dönem) boyunca, ders anlatımı ve ödev kısımlarının yer değiştirdiği tersten yapılandırılmış yazma sınıfı modeli uygulanmıştır. Öğrenciler öğretmen tarafından çekilen ders videolarını evlerinde ödev olarak izlemişler, bu şekilde sınıf içerisindeki zaman tamamen genel alıştırmalara ve paragraf yazma uygulamalarına ayrılmıştır. Diğer taraftan, İngiliz Dili Eğitimi hazırlık sınıfında öğrenim gören 20 öğrenciden oluşan kontrol grubuna geleneksel ders anlatımına dayalı öğretim tekniği uygulanmıştır. Her iki grupta da daha önce seçilmiş ders kitabına uygun olarak araştırmacı tarafından hazırlanmış aynı izlence takip edilmiştir. Her iki grubun yazma dersi de araştırmacı tarafından yürütülmüştür. On beş hafta süren uygulama sonunda, gruplara kendi aralarında ve kendi içlerinde fark oluşup oluşmadığını belirlemek için aynı sontest uygulanmıştır. Ön ve sontest sonuçlarının analizinde SPSS 20 programıyla bağımsız ve eşleştirilmiş örneklem t- testi uygulanmıştır. Elde edilen sonuçlara göre, öğrencilerin yazma performansları bakımından deney ve kontrol grupları arasında istatistiksel olarak anlamlı fark olduğu görülmüştür. Diğer bir deyişle, deney grubu öğrencileri uygulamadan sonra kontrol grubundaki öğrencilerden daha iyi performans sergilemişlerdir. Buna ilaveten, uygulama sonrası öğrencilerin paragraflarında en çok gelişme İlgililik ve İçerik boyutunda olmuştur. Bu boyutu sırasıyla, Organizasyon ve Yapı, Genel Görünüm, Kelime Çeşitliliği ve Seçimi, Dilbilgisi & Cümle yapısı ve Yazım Kuralları boyutları izlemiştir. Tersten yapılandırılmış yazma sınıfı modeline yönelik öğrencilerin tutumları araştırmacı tarafından geliştirilen anketle ölçülmüştür. Verilen cevapların frekans analizleri, öğrencilerin büyük bir çoğunluğunun yeni uygulamaya karşı olumlu tutum geliştirdiğini göstermiştir. Anketten elde edilen sonuçların, araştırmanın nitel kısmını oluşturan yarı yapılanmış görüşme sonuçlarıyla da örtüştüğü görülmüştür.

Sonuç olarak, hem nicel hem de nitel verilerden elde edilen bulgular, tersten yapılandırılmış yazma sınıfı modelinin öğrencilerin yazma becerisi yeterlilikleri açısından geleneksel ders anlatımına dayalı öğretim şeklinden daha etkili olduğunu göstermiştir. Tersten yapılandırılmış yazma sınıfı modeli, yabancı veya ikinci dilde yazma bağlamında kullanılarak yazma becerisindeki zorluk, sıkılma ve bu beceriye yönelik olumsuz tutumlara bir çözüm olabileceği düşünülmektedir.

Anahtar Kelimeler: Tersten yapılandırılmış öğrenme, tersten yapılandırılmış yazma sınıfı, tersten yapılandırılmış sınıflar, harmanlanmış öğrenme.

TABLE OF CONTENT PAGE ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS ... i ABSTRACT ... ii ÖZ ... iv TABLE OF CONTENT ... vi LIST OF TABLES ... xi

LIST OF FIGURES ... xiii

LIST OF GRAPHS ... xiv

LIST OF APPENDICES ... xv

LIST OF ABBREVIATIONS ... xvii

CHAPTER 1: INTRODUCTION ... 1

1.1. Statement of the Problem ... 1

1.2. Aim of the Study ... 4

1.3. Significance of the Study ... 5

1.4. Limitations ... 5

1.5. Assumptions ... 6

1.6. Definitions ... 6

CHAPTER 2: REVIEW OF LITERATURE ... 9

2.1. Writing as a Productive Skill ... 9

2.1.1. The Nature of Writing Tasks ... 11

2.1.2. Types of Writing Performances ... 12

2.1.2.1. Notation ... 12

2.1.2.2. Dictation ... 12

2.1.2.3. Expressive Writing & Composition ... 13

2.1.2.4. Controlled Writing ... 13

2.1.2.6. Display and Real Writing ... 14

2.1.3. The Nature of Written Language ... 14

2.1.4. Characteristics of EFL/ESL Writing ... 16

2.2. Teaching Writing ... 19

2.2.1. Approaches to Teaching Writing ... 24

2.2.1.1. The Controlled-to-Free Approach ... 24

2.2.1.2. The Grammar-Syntax-Organization Approach ... 24

2.2.1.3. The Paragraph-Pattern Approach ... 25

2.2.1.4. The Free Writing Approach ... 25

2.2.1.5. The Product Approach ... 25

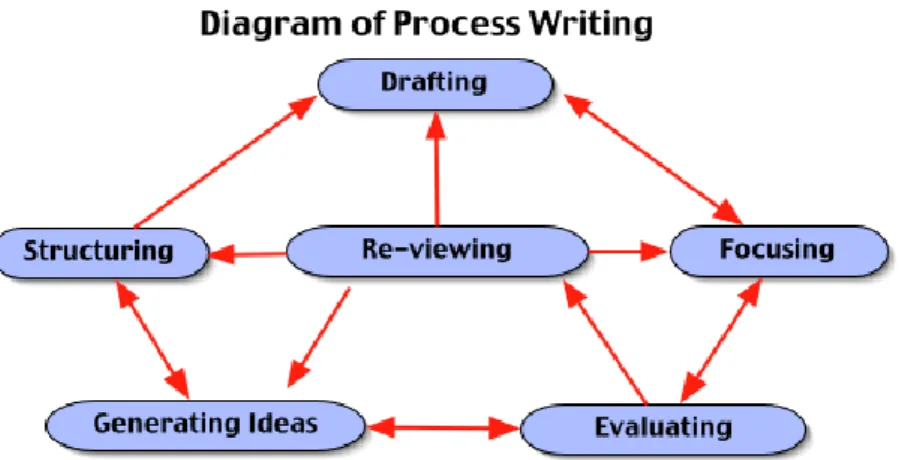

2.2.1.6. The Process Approach ... 26

2.2.1.7. Post-Process Approaches ... 27

2.3. Feedback on Writing ... 29

2.3.1. Types of Feedback ... 30

2.3.1.1. Individual Conferences & Oral Teacher Feedback ... 31

2.3.1.2. E- Feedback ... 31

2.3.1.3. Peer Feedback ... 32

2.3.1.4. Taped Commentary ... 33

2.3.1.5. Reformulation ... 33

2.3.2. Ways of Providing Written Feedback ... 34

2.3.2.1. Written Comments ... 34

2.3.2.2. Checklists ... 35

2.3.2.3. Rubrics ... 35

2.4. Assessing Writing ... 35

2.4.1. Portfolio as an Alternative Assessment ... 37

2.4.2. Types of Scoring for Writing Assessment ... 39

2.4.2.1. Primary Trait Scales ... 39

2.4.2.2. Holistic Scales ... 40

2.5. Technology and Teaching Writing ... 41

2.6. Blended Learning ... 45

2.6.1. Definition ... 45

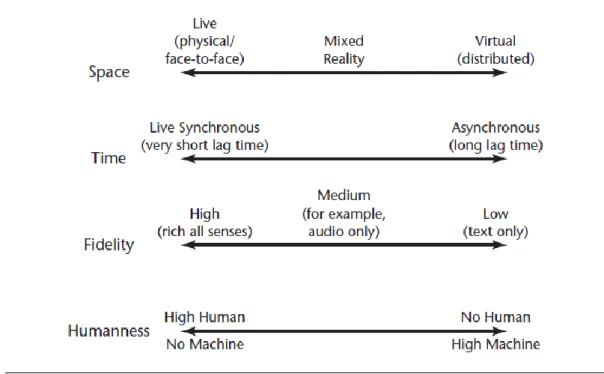

2.6.2. Theoretical Framework ... 45

2.6.3. Constructivism and Blended Learning ... 49

2.6.4. Types of Blended Learning ... 52

2.6.5. Relevant Studies on Blended Learning ... 53

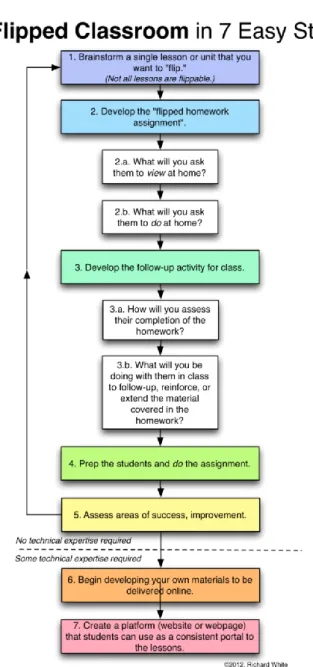

2.7. Flipped Classroom ... 56

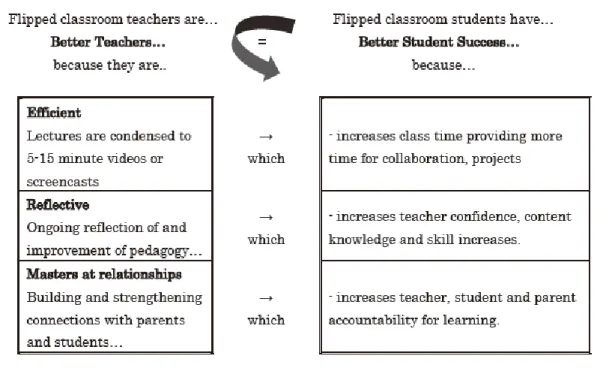

2.7.1. Background, Definition, and Characteristics ... 56

2.7.2. Critique of Flipped Learning ... 68

2.7.3. Relevant Studies on Flipped Classroom/Learning ... 70

CHAPTER 3: METHODOLOGY ... 74

3.1. Research Design ... 74

3.2. Population and Sampling ... 76

3.3. Data Collection and Procedure ... 78

3.3.1. Instruments ... 78

3.3.1.1. Argumentative Paragraph Rubric ... 78

3.3.1.2. ICT Literacy Survey ... 79

3.3.1.3. Flipped Writing Class Attitude Questionnaire ... 79

3.3.1.4. Interview ... 81

3.3.2. Procedure ... 81

3.3.2.1. Pre-Test ... 82

3.3.2.2. ICT Literacy Survey ... 82

3.3.2.3. Treatment ... 83

3.3.2.4. Post-Test ... 95

3.3.2.5. The Process in the Control Group ... 95

3.3.2.6. Flipped Writing Class Attitude Questionnaire ... 101

CHAPTER 4: FINDINGS AND DISCUSSION ... 103

4.1. Findings of Information and Communication Technologies Survey ... 103 4.2. Findings about Pre-Test Scores of the Experimental and Control Groups’ Students ... 110 4.3. Findings about Post-Test Scores of the Experimental and Control Groups’ Students ... 112 4.4. Findings about Pre-Test and Post-Test Scores of the Experimental Group's Students ... 113 4.5. Findings about Pre-Test and Post-Test Scores of the Control Group's Students ... 114 4.6. Findings about Pre-Test and Post-Test Scores of the Experimental Group and the Control Groups' Students in Terms of the Dimensions of Writing Skill ... 115

4.6.1. Findings about the dimension of Organization and Structure .... 116 4.6.2. Findings about the dimension of Relevance and Content ... 117 4.6.3. Findings about the dimension of Lexical Range/Word Choice . 119 4.6.4. Findings about the dimension of Grammar/Sentence Structure . 120 4.6.5. Findings about the dimension of Mechanics ... 122 4.6.6. Findings about the Overall Dimension ... 123 4.7. Findings and Discussion about Flipped Writing Class Attitudes

Questionnaire ... 125 4.7.1. Findings and Discussion about Students' Attitudes towards

Course Management System (CMS) ... 125 4.7.2. Findings and Discussion about Students' Attitudes towards Video Lectures ... 127 4.7.3. Findings and Discussion about Students' Attitudes towards

Learning Writing through Flipped Classroom ... 130 4.7.4. Findings and Discussion about Students' Attitudes towards

Preparing for the Exams in Flipped Learning Environment ... 134 4.7.5. Findings and Discussion about Students' Attitudes towards Flipped versus Traditional Learning ... 135 4.8. Findings and Discussion about the Effectiveness of Flipped Writing Class with Regard to Improving Writing Skills ... 140

CHAPTER 5: CONCLUSION AND SUGGESTIONS ... 143

5.1. Summary of the Study ... 143

5.2. Conclusions ... 145

5.3. Suggestions and Implications ... 148

REFERENCES ... 150

APPENDICES ... 169

ÖZGEÇMİŞ ... 222

LIST OF THE TABLES PAGE

Table 1. A Comparison of Standard and Flipped Math Class ... 58 Table 2. Comparison of Class Time in Traditional versus Flipped Classroom ... 60 Table 3. Comparison of the Experimental and Control Groups’ Pre-Test Results ... 111 Table 4. Comparison of the Experimental and Control Groups’ Post-Test Results ... 112 Table 5. Comparison of the Experimental Group’s Pre-Test and Post-Test Results .. 113 Table 6. Comparison of the Control Group’s Pre-Test and Post-Test Results ... 114 Table 7. Comparison of the Experimental Group’s Pre-Test and Post-Test Results with

Regard to Organization and Structure Dimension ... 116 Table 8. Comparison of the Control Group’s Pre-Test and Post-Test Results with Regard to Organization and Structure Dimension ... 117 Table 9. Comparison of the Experimental Group’s Pre-Test and Post-Test Results with Regard to Relevance and Content Dimension ... 118 Table 10. Comparison of the Control Group’s Pre-Test and Post-Test Results with

Regard to Relevance and Content Dimension ... 118 Table 11. Comparison of the Experimental Group’s Pre-Test and Post-Test Results with Regard to Lexical Range/Word Choice Dimension ... 119 Table 12. Comparison of the Control Group’s Pre-Test and Post-Test Results with

Regard to Lexical Range/Word Choice Dimension ... 120 Table 13. Comparison of the Experimental Group’s Pre-Test and Post-Test Results with Regard to Grammar/Sentence Structure Dimension ... 121 Table 14. Comparison of the Control Group’s Pre-Test and Post-Test Results with Regard to Grammar/Sentence Structure Dimension ... 121 Table 15. Comparison of the Experimental Group’s Pre-Test and Post-Test Results with Regard to Mechanics Dimension ... 122 Table 16. Comparison of the Control Group’s Pre-Test and Post-Test Results with Regard to Mechanics Dimension ... 122 Table 17. Comparison of the Experimental Group’s Pre-Test and Post-Test Results with Regard to Overall Dimension ... 123 Table 18. Comparison of the Control Group’s Pre-Test and Post-Test Results with Regard to Overall Dimension ... 124 Table 19. Percentage of Students' Attitudes towards Course Management System (CMS) ... 125

Table 20. Percentage of Students' Attitudes towards Video Lectures ... 127 Table 21. Percentage of Students' Attitudes towards Learning Writing through Flipped Classroom ... 130 Table 22. Percentage of Students' Attitudes towards Preparing for the Exams in Flipped Learning Environment ... 134 Table 23. Percentage of Students' Attitudes towards Flipped versus Traditional Learning ... 135 Table 24. Pearson-Product Moment Correlation Coefficient of the Pre-Test ... 217 Table 25. Pearson-Product Moment Correlation Coefficient of the Post-Test ... 217

LIST OF THE FIGURES PAGE

Figure 1. The Hayes-Flower Model ... 22

Figure 2. The Hayes Model ... 23

Figure 3. White and Arndt's Process Model ... 27

Figure 4. Convergence of Traditional Face-To-Face and Distributed Learning Environments ... 47

Figure 5. Four Dimensions of Interaction in Face-to Face and Distributed Learning Environments ... 48

Figure 6. Flipped Classroom in 7 Easy Steps ... 59

Figure 7. Better Teachers = Better Student Success ... 67

Figure 8. Student Sign Up Web-Page of Edmodo ... 85

Figure 9. A Sample YouTube Page Containing First Week's Video Lecture ... 86

LIST OF THE GRAPHS PAGE

Graph 1. Types of High School the Experimental and Control Group Students

Graduated from ... 78

Graph 2. Percentage of Students' Computer Possession ... 104

Graph 3. Percentage of How Students Use a Computer ... 104

Graph 4. Percentage of whether Students have a TabletPC or not ... 105

Graph 5. Percentage of whether Students have a Smart Phone/PDA ... 105

Graph 6. Percentage of How Often Students Use Computer ... 106

Graph 7. Frequencies of How Often Students Use Computer to Complete Some Certain Tasks ... 107

Graph 8. Percentage of whether Students’ Have Access to the Internet or not ... 108

Graph 9. Percentage of How Often Students Use Internet ... 108

Graph 10. Frequencies of What the Students use the Internet for ... 109

Graph 11. Percentage of whether Students have ever Used a CMS before ... 110

Graph 12. Mean scores of the Experimental and Control Groups’ Pre-Test Results . 111 Graph 13. Mean scores of the Experimental and Control Groups’ Post-Test Results 113 Graph 14. Mean scores of the Experimental Group’s Pre-Test and Post-Test Results ... 114

Graph 15. Mean scores of the Control Group’s Pre-Test and Post-Test Results ... 115

Graph 16. Students' Responses about their Satisfaction with CMS (Edmodo) ... 126

Graph 17. Students' Responses about their Satisfaction with Video Lectures ... 129

Graph 18. Students' Responses about the Efficiency of Flipped Writing Class ... 132

Graph 19. Students' Responses on the basis of Pros and Cons of Flipped Writing Class ... 133

Graph 20. Students' Responses about their Preferences of Flipped versus Traditional Class ... 136

Graph 21. Students' Responses with regard to Problems Encountered in the Flipped Class ... 138

LIST OF APPENDICES PAGE

Appendix 1. A Sample Primary Trait Scale ... 170

Appendix 2. A Sample Holistic Scale ... 171

Appendix 3. A Sample Analytic Scale ... 172

Appendix 4. Argumentative Paragraph Rubric ... 173

Appendix 5. Information and Communications Technologies (ICT) Literacy Survey ... 176

Appendix 6. Flipped Writing Class Attitude Questionnaire Pilot Study ... 178

Appendix 7. Statistical Analysis of the Flipped Writing Class Attitude Questionnaire ... 180

Appendix 8. Flipped Writing Class Attitude Questionnaire Main Study ... 183

Appendix 9. Interview Questions about Flipped Writing Class ... 185

Appendix 10. Flipped Writing Class Syllabus ... 186

Appendix 11. Content of the Writing Pack Compiled By the Researcher ... 187

Appendix 12. Presentation on Flipped Writing Course ... 188

Appendix 13. Images of Video Lectures on YouTube ... 192

Appendix 14. Sample Peer Review Form for Descriptive Paragraph Type ... 200

Appendix 15. Argumentative Paragraph Checklist ... 201

Appendix 16. Pre-Test for the Experimental and Control Group ... 203

Appendix 17. Post-Test for the Experimental and Control Group ... 204

Appendix 18. A Sample Argumentative Paragraph Written By a Student in the Experimental Group in the Pre-Test ... 205

Appendix 19. A Sample Argumentative Paragraph Written By a Student in the Experimental Group in the Post-Test ... 206

Appendix 20. A Sample Argumentative Paragraph Written By a Student in the Control Group In The Pre-Test ... 207

Appendix 21. A Sample Argumentative Paragraph Written By a Student in the Control Group In The Post-Test ... 208

Appendix 22. Sample Process Paragraphs Written By Students in the Experimental Group ... 209

Appendix 23. Sample Process Paragraphs Written By Students in the Control Group

... 211

Appendix 24. Sample Descriptive Paragraphs Written By Students in the Experimental Group ... 213

Appendix 25. Sample Descriptive Paragraphs Written By Students in the Control Group ... 215

Appendix 26. Inter-Reliability of the Raters ... 217

Appendix 27. Transcription of a Sample Interview ... 218

Appendix 28. Pre-Test Results of the Experimental and Control Groups ... 220

LIST OF ABBREVIATIONS

BLOG: Web Log

CEF: Common European Framework of References for Languages CMS: Course Management System

DVD: Digital Versatile/Video Disc EFL: English as a Foreign Language ELT: English Language Teaching E-MAIL: Electronic Mail

ESL: English as a Second Language FL: Foreign Language

ICT: Information and Communication Technologies L1: Native Language

L2: Second Language

LMS: Learning Management System

MOODLE: Modular Object-Oriented Dynamic Learning Environment PhD: Doctor of Philosophy

SPSS: Statistical Package for the Social Sciences TOEFL: Test of English as a Foreign Language USB: Universal Serial Bus

VCD: Video Compact Disc

CHAPTER 1

INTRODUCTION

This chapter presents a general framework of the study. It consists of statement of the problem, aim and significance of the study, assumptions, limitations and definitions.

1.1. Statement of the Problem

Considering the communicative framework of language teaching, writing is of primary importance as it is one of the productive skills in language study. In the modern world where languages are learned for communication, this productive skill needs to be encouraged in language classes as much as possible. For this reason, research on second language writing has experienced a dramatic outburst and has gained recognition as a new field of research in recent years (Matsuda & De Pew, 2002; Silva & Brice, 2004). While research on second language writing has showed an increase, research on foreign language writing has received scant attention in the literature. However, in the last few years, research on foreign language writing has started to gain importance and has found place in conferences and journals. The reason for this is that writing in English as a foreign language (EFL) context is assumed to be more difficult than writing in English as a second language (ESL) context. Reichelt, Lefkowitz, Rinnert, and Schultz (2012) focus on the main differences between EFL and ESL writing context. They state that the important distinguishing factors are ESL and EFL learning environments, contrasting characteristics of learners, strong emphasis on English language writing and research in ESL context, and different teaching approaches.

Likewise, Manchón (2009) states that foreign language (FL) writing takes place in classes to a great extent. Most of foreign language writers learn and practise writing in classes. Manchón (2009: XV) distinguishes between FL, second language (SL) and L1 writing as in the following ways;

The backgrounds of foreign language (FL) students in terms of social, cultural, and educational perspectives are likely to be uniform. These similarities reduce

the linguistic and literacy variability among research participant.

Some FL students have the opportunity to interact with L2 speakers and their cultures. This interaction has an impact on learner proficiency and motivation.

Educational systems in the world provide L1 writing instruction in different degrees, thus learners gain proficiency in L1 writing which correlates with L2 writing proficiency.

Each society places different social value on writing. Manchón (2009) takes the example of North American SL settings, and he states that learning to write in these contexts is regarded as 'school-sponsored' as defending and taking a position. Writers in these settings develop some approaches and attitudes towards writing which is different from the ones developed in societies in which the ability to write is constructed as a reflection of quality education, self-reflect, personal creativity, and so on. For these reasons, a particular society wants its young people to gain L2 writing proficiency as well so as to make their learners reflect their ideas as in the case in L1 writing.

Motivation to write in FL context may be extrinsic and explicit, because learners in FL settings have no apparent aims apart from teacher-set assignments.

Lastly, employing writing to develop language proficiency may be a core aim of L2 writing in FL context, which is contrary to dogma in SL writing.

As it is clear from what Manchón emphasizes, writing in FL context is a very different issue and it should be put into a different category. Writing in L1 is already a painful process. When it comes to writing in FL context, it is more painful and difficult (Gilmore, 2009). This hardship affects students’ performances in writing classes, and creates boredom, lack of interest, participation, and motivation in the classroom. They need more and more writing practice both inside and outside the classroom. Social, cultural and particularly educational backgrounds of the FL students should be supported well in order to minimize the negative effects on their writings.

The other problem rising in FL writing classes may be related to students’ negative attitudes towards writing. Sharples (1993) points out that the nature and complexity of writing in FL context may demotivate the students, lead them to discouragement, and result in negative attitudes. Development of attitudes towards writing is an integral part of writing development. In order to make students better

writers, their initial personal theories of writing should be taken into account (Petric, 2002). For this reason, foreign language writing teachers may revise their styles of instruction and minimize difficulties and try to create more enjoyable, motivating, and self-reliant classes.

In order to cope with both disadvantages appearing in the foreign language classes where students have limited opportunities to practice the target language and negative attitudes towards writing skill, foreign language teachers should inevitably integrate technology into the classroom. Our age is the age of "digital natives" which is defined in www.oxforddictionaries.com as "a person born or brought up during the age of digital technology and therefore familiar with computers and the Internet from an early age." Digital natives have almost limitless access to technology which develops with each passing day all over the world. With their technological devices with which they are always together such as smartphones, laptops, mp3 players, netbooks, tablet PCs, IPods, and so on, digital natives cannot be deprived of their devices in today's educational context. Integration of their valuable devices into learning process will probably yield better results in terms of language learning and production. Foreign language teachers in the 21st century, particularly foreign language writing teachers, need to find answers to the following questions if they really want to contribute to learning process:

- What can we do to attract students' attention and to cope with the prejudice against foreign language writing?

- How can we integrate technology into our classrooms?

- How can we practice more inside the classroom where it is foreign language students' almost unique chance to be exposed to authentic language and tasks? - How can we change our ways of writing instructions to prevent boredom and lack of motivation in foreign language classrooms?

- How can we create more learner-centred and active learning atmosphere in foreign language classes?

- How can we change our role in the classroom from an authority to a facilitator?

With all the above-mentioned questions and problems in mind, this study suggests an alternative model of writing instruction for foreign language classes in EFL

context. The model changes the traditional way of instruction and presents more learner-centred, motivating, amusing, and supportive style of writing instruction with the help of blended learning tools.

1.2. Aim of the Study

Recent developments in educational technologies and Web 2.0 tools which enable the users to generate the content of websites make it inevitable to integrate these technologies into language learning and teaching curricula. Flipped learning, which is a very recent phenomenon, is one of these technological facilities which provide student-centred and autonomous learning environments for learners. It is believed that flipped classrooms offer great advantages to language learning and teaching process. First, it promotes autonomous learning in that each student is responsible for their own learning. Then, it has a potential of increasing the student-teacher and student-student interactions in a collaborative learning environment in which the teacher's role is not an authority anymore, but a guide and facilitator. Moreover, flipped classroom provides learners with maximum flexibility in following the lectures with its nature of anytime and anywhere learning notion. Thanks to flipped learning, teachers have a chance of appealing to different learning needs and styles, and each student can study at their own pace.

With the above-mentioned advantages in mind, the aim of this study is to suggest flipped writing class model as an alternative for traditional lecture-based writing instruction. By employing the pillars of flipped classes, blended learning environments for EFL students and the quantitative and qualitative data gathered throughout the study, the researcher tries to find answers to the following research questions:

1. What are the perceptions of the students in the experimental group towards the Information and Communication Technologies (ICT) use? 2. Is there a statistically significant difference in the pre-test scores of the

students in the experimental and control groups prior to the treatment process of the Flipped Writing Class Model?

3. Is there a statistically significant difference in the post-test scores of the students in the experimental and control groups after the treatment process of the Flipped Writing Class Model?

4. Is there a statistically significant difference in the pre- and post-test scores of the students in the experimental group after the treatment process of the Flipped Writing Class Model?

5. Is there a statistically significant difference in the pre- and post-test scores of the students in the control group after the process of traditional lecture-based writing class?

6. Are there statistically significant differences in the pre- and post-test scores of the students in the experimental and control groups with regard to such dimensions of writing skill as;

a. Organization and Structure b. Relevance and Content c. Lexical Range/Word Choice d. Grammar/Sentence Structure e. Overall

7. What are the attitudes of the students in the experimental group towards Flipped Writing Class Model?

8. Is Flipped Writing Class Model an effective way of improving writing skill?

Applying respectively a new model in the foreign language teaching field, the researcher hopes to find satisfying answers to the questions above. The study is expected to contribute to foreign language writing research by suggesting a new model, and thus, help foreign language students cope with difficulties in writing classes. The study also aims to create more enjoyable, customizable, motivating and interesting writing classes.

1.3. Significance of the Study

Writing is regarded as one of the most problematic skills especially in EFL context. Foreign language teachers and several researchers have constantly been looking for new ways of instruction of writing to make students become good writers and

improve their writing skills as much as possible. Some researchers focus on students’ perceptions and attitudes of foreign language writing instruction. For instance, upon analysing 50 EFL students’ composition, Rushidi (2012) concludes that writing is not attached so much importance by the students, but different genres of writing can be helpful for students to improve their writing skills and writing is no longer considered as an intimidating process. McCarthey and Garcia (2005) state that students’ writing practices and attitudes toward writing are influenced by home backgrounds and classroom contexts. Kobayashi and Rinnert’s (2002) findings on students’ perceptions of first language literacy instruction and its implication for second language writing highlight L1 and L2 writing relations. The writers' aim is to clarify the gap between L1 instruction and its effects on L2 performances.

With regard to the new ways of instruction, several researchers (Cumming and Riazi, 2000; Mirlohi, 2012; Arslan and Kızıl, 2010; Pooser, 2004; Sun, 2010; Hashemnezhad and Zangalani, 2012; Dişli, 2012) have set forth different ways of writing instruction to make writing courses more enjoyable, easier, interesting and motivating. The techniques they offer include processing instruction, launching web sites special for writing instruction, using blog software, online writing, and employing computer assisted writing activities. As it is seen, there is an adequate number of studies employing technology in writing classes, but flipped writing class model has not been emphasized in the literature so far. For this reason, the study is attached importance as it attempts to carry out relatively a new method in EFL writing classes.

The study is also significant in that the new model adopted in an EFL writing class setting requires the students to be actively involved in their own learning process, which complies with the principles of constructivism. The students are responsible for their learning since they are expected to watch pre-recorded videos as the lecture part of the course. They interact with their friends and the teacher by helping their peers and getting oral and written feedback from the teacher and peers in the face-to-face phases of the writing course. Thus, they become independent learners.

This study takes on an important role by empowering a new model for foreign language writing classes. It is expected that the flipped writing class model will shed a light upon English Language Teaching (ELT) field and the importance of flipped

classes in language teaching and learning will be clarified. In addition, this study is expected to contribute to prospective research and studies on foreign language writing skills.

1.6. Limitations

1- The study is limited to one semester of treatment process for Flipped Writing Class. 2- This study is limited to two groups of students attending the ELT preparatory classes at School of Foreign Languages, Ondokuz Mayıs University in 2013 – 2014 academic year.

3- This study is limited to the EFL context in the School of Foreign Languages at Ondokuz Mayıs University.

4- The treatment process is limited to the randomly-assigned experimental group of the study.

1.4. Assumptions

1. The levels of English knowledge of both the experimental group and the control group are assumed to be similar.

2. All students in the experimental group are assumed to have an easy access to internet and follow the videos created by the researcher.

3. All students in the experimental group and the control group are assumed to answer the questions in the questionnaire and evaluate their own performances sincerely.

4. The pre-test and post-test are assumed to be in conformity with the levels of students. 5. It is assumed that the researcher will compensate for some technological problems like students’ lack of computers or internet connection by letting them download and copy the necessary documents and videos in their DVDs, flash memories or directly to their computers.

1.5. Definitions

Blended Learning: There is a variety of definitions of blended learning. Most of the researchers prefer defining blended learning as simply the combination of online

(mostly asynchronous) learning with face-to- face learning environments (Reay, 2001; Rooney, 2003; Sands, 2002; Ward & LaBranche, 2003; Young, 2002).

Flipped Class: It is a recent term referring to inverted classrooms which have brought an innovative perspective to the traditional lectures.

Digital Native: A person born or brought up during the age of digital technology and therefore familiar with computers and the Internet from an early age. (www.oxforddictionaries.com)

Course Management System: CMS is a software application for the administration, documentation, tracking, reporting and delivery of e-learning education courses or training programs (Ellis, 2009).

Video Lectures: Videos created by the teacher or taken from different sources. They constitute the homework part of the Flipped Writing Class.

CHAPTER 2

REVIEW OF LITERATURE

This chapter presents an overview of writing skill with detailed explanations on the nature of writing skill, approaches to teaching writing, feedback and assessing issues on writing, and integration of technology into writing. In the other sections of this chapter, blended learning and flipped classrooms with their theoretical background and

relevant studies in the literature are examined in detail.

2.1. Writing as a Productive Skill

Language learning involves four skills; listening, reading, speaking and writing. The former two are considered as receptive skills while the latter are productive ones. Among these four skills, writing, which is a productive skill, is an important skill foreign language learners need to develop. In other words, writing is an inseparable part of foreign language teaching in terms of acquiring communication skills. Writing is undoubtedly for communication; however, it should be distinguished from the other productive skill, speaking, because of its peculiar characteristics. What makes writing more difficult than speaking is explained by Rivers (1981: 291-292) as follows:

We must realize that writing a language comprehensibly is much more difficult than speaking it. When we write, we are, as it were, "communicating into space." When we communicate a message orally, we know who is receiving the message. We know the situation, including the mood and tone it requires of us, even if it is as impersonal as "someone in the office" taking a phone message. We receive feedback from the interlocutor or audience (oral, emotional, or kinesthetic) which makes clear how the message is being comprehended. With spoken messages, many things are visible, or are part of shared knowledge, which cannot be taken for granted in writing.

The above-mentioned characteristics of writing skill leads a number of problems for especially EFL learners who constantly struggle with the language they are trying to learn. In a broader sense, learners think that writing skill is just a skill to be learned in school or to pass an exam. They think that after graduation, they will never need to write a paragraph or an essay except for those who are engaged in academic studies. They usually miss a critical point which emphasizes that writing is a complex and multi-faceted process which requires the learners to be aware of and combine different

components of language successfully. These acquired or learned components of language can only be put into practice through productive skills. In other words, with a good command of productive skills, one can declare that s/he knows that language. In receptive skills, reading and listening, learners can handle the language at the most sophisticated levels, because in receptive skills they do not have to control the complexity of the material they face. These are the skills learners can improve independently at a later stage. However, in productive skills, learners need to use what they know, the language, effectively and flexibly (Rivers, 1981).

In order to use the language learned, learners try to develop their productive skills, which is a very challenging work for them. Microskills for writing can help learners improve their writing skills. Brown (2001:343) enumerates the following microskills for writing:

1. Produce graphemes and orthographic patterns of English. 2. Produce writing at an efficient rate of speed to suit the purpose.

3. Produce an acceptable core of words and use appropriate word order patterns.

4. Use acceptable grammatical systems (e.g., tense, agreement, pluralization), patterns, and rules.

5. Express a particular meaning in different grammatical forms. 6. Use cohesive devices in written discourse.

7. Use the rhetorical forms and conventions of written discourse.

8. Appropriately accomplish the communicative functions of written texts according to form and purpose.

9. Convey links and connections between events and communicate such relations as main idea, supporting idea, new information, given information, generalization, and exemplification.

10. Distinguish between literal and implied meanings when writing.

11. Correctly convey culturally specific references in the context of the written text.

12. Develop and use a battery of writing strategies, such as accurately assessing the audience's interpretation, using prewriting devices, writing with fluency in the first drafts, using paraphrases and synonyms,

soliciting peer and instructor feedback, and using feedback for revising and editing.

As it can be seen from the content of microskills, writing consists of various components of the language from grammar to distinguishing implied meanings. Only if one is good at these components of the language, s/he can produce the written work effectively. Learning and teaching how to write in a foreign language is extremely important as the written work is an indication of one’s language proficiency with different dimensions from lexis and sentence structure to relevance, organization and mechanics.

Drawing an analogy between swimming and writing, the psycholinguist Eric Lenneberg discusses this "species specific" human behaviour. Walking and talking are learnt universally, but swimming and writing are behaviours learned culturally. If there is an appropriate setting, one can learn to swim, and if there is a literate society in which one lives, one can learn to write (Brown, 2001:334). It is obvious from this analogy that like learning to swim, learning to write requires to follow a systematic, planned, and well-organized instruction as well as more and more practice for a perfect like performance. This complex and multi-faceted process should be evaluated from different points of view taking into account the nature of writing tasks, types of writing performances, the nature of written language, and characteristics of EFL and ESL writing.

2.1.1. The Nature of Writing Tasks

The focus of writing tasks is mainly on the mechanics. The mechanics refer to the recognition and discrimination of letters, word recognition, the rules of spelling and capitalization, and the recognition of sentences and paragraphs. If learners’ native language writing system is different from the target language, the mechanics are of great importance. The primary aim of early writing tasks is mainly to help the learners move from letters to sentences and discourse. Drills on recognition and writing are the first steps in the development of writing skill.

As for more advanced writing tasks which aim to develop writing skill as a fundamental communication skill, the focus is on “... basic process-oriented tasks that will need to incorporate some language work at morphological and discourse level.” (Olshtain, 2001: 211). In order to cope with advanced writing tasks, a set of specifications are developed. These are Task description, Content Description, Audience Description, Format Cues, Linguistic Cues, Spelling and Punctuation Cues.

Olshtain (2001) categorizes writing tasks as Practical, Emotive and School-oriented. Practical writing tasks are procedural and in a predictable format. There may be various list types such as things to do, things completed, and shopping list. Filling in forms and preparation of invitations are also the examples of other types of practical writing tasks. The focus in these types of writing tasks is on orthographic, mechanical, and linguistic accuracy. Emotive writing tasks are related to the personal writing such as narratives describing personal experiences, journals, and diaries. They are indicators of learners' general proficiency. School-oriented tasks are the tasks which are offered in schools in the form of assignments, summaries and different kinds of paragraphs and essays. All these writing tasks aim at improving learners' writing proficiency in linguistic, semantic, relevance, and organization level.

2.1.2. Types of Writing Performances

2.1.2.1. Notation

Notation refers to the activities covering the ability to use the writing system of the language. Learners are expected to copy or reproduce an already written script. The objective of such an activity is to make the learners familiarize with the new writing system which does not have one-to-one correspondence with their native language. These sorts of activities may last long if the writing systems are totally different (Rivers, 1981).

2.1.2.2. Dictation

As early writing activities, dictation in which learners write down English letters and sentences can be employed. In dictation, teachers may read sentences and

paragraphs by pausing at certain times, and students try to write what they hear (Brown, 2001). This provides students to practise in listening carefully and pay attention to the mechanics of spelling, punctuation, and capitalization. In a conventional dictation activity, the teacher stands in front of the class and reads a passage focusing on recently learned vocabulary or grammar point (Raimes, 1983).

2.1.2.3. Expressive Writing & Composition

This kind of writing task aims at helping students express their personal meaning, original ideas and convey information in an organized way in the target language. Rivers (1981: 296) states that “The ultimate goal in creative expression will be to express oneself in a polished form which requires a nuanced vocabulary and certain refinements of structure.” In second or foreign language context, students cannot still express themselves by using wide range of vocabulary and knowledge in the target language, because their resources of expression are still limited. For this reason, it is suggested that students simplify their thoughts and organize them well, and think in detail before writing.

2.1.2.4. Controlled Writing

This type of task does not permit much creativity for students. An example of this task is to give the students a paragraph and ask them to change some certain structure (Brown, 2001). Other form of controlled writing is guided writing which is a little bit flexible. Students are given more freedom for the selection of lexical items and grammatical forms. They are prevented from attempting to write beyond their level of the target language (Rivers, 1981). Another form of guided writing is dicto-comp in which the paragraph is read twice or three times at normal speed, and students are asked to rewrite the paragraph. In other words, students are asked to write what they remember from teacher’s reading. The teacher can write some key words on the board as cues (Brown, 2001).

2.1.2.5. Self-Writing

Note-taking, diary, and journal writing are in this category. Students are expected to take notes during a lecture or write more personal thoughts and feelings about a topic. Teachers might then read and analyse their writings.

2.1.2.6. Display and Real Writing

All writing activities within the curriculum fall into this category. Some writing tasks indicate real communicative objectives. These are written to an audience as a response message. However, display and real writing are combined in the form of three subcategories such as academic, technical and personal writing (Brown, 2001).

2.1.3. The Nature of Written Language

There exist some characteristics peculiar to written language. Raimes (1983) emphasizes the differences between written and spoken language. Firstly, it is stated that everybody acquires a native language in the first few years of life, but not everybody learns to write or read. Secondly, written language has standard forms of syntax, vocabulary, and grammar, whereas the spoken language has variations with regard to dialects. Thirdly, spoken language enables people to make use of gestures, facial expressions, and intonation to convey their ideas, while written language involves only words. Another difference is that spoken language is usually unplanned, but written language is generally planned. There may be many more differences between the spoken and written language. The above-mentioned differences are the ones which are of primary importance. Some characteristics of written language are also highlighted as in the followings:

a) Variety of Vocabulary

In written language, students try to use more advanced and wide-ranging vocabulary effectively and accurately. Passive vocabulary may also be activated in written language. The reason for this is that students have more time to think and produce more advanced lexical items.

b) Permanence

When students write and hand in the final draft of a piece of writing, they feel like losing power and they think that they will not withdraw and make clarifications on the written work. This makes the writing a challenging activity which almost all students are scared of. However, in spoken language they feel more relaxed as they have a chance of correcting and making clarifications.

c) Variety

Written language, in contrast to spoken language, requires standardization of grammar, sentence structure, syntax, vocabulary and organization (Raimes, 1983). In spoken language, various accents and dialects may exist. However, written language has more variety in terms of sentence types, lexical range and vocabulary.

d) Formality

There are some conventions to be followed in written language. Students are expected to obey some rules while writing paragraphs, essays, and a piece of writing. Brown (2001:306) states that

We have rhetorical, or organizational, formality in essay writing that demands a writer's conformity to conventions like paragraph topics; we have logical order for, say, comparing and contrasting something; we have openings and closings, and a preference for non-redundancy and subordination of clauses, etc.

It can be inferred from what Brown states that written language is often more formal than spoken language. This formality necessitates producing organized and well-planned pieces of writing which are in line with certain conventions.

e) Processing Time

Students have much more time to produce the final draft of a piece of writing when compared to spoken production. However, in many contexts like EFL and ESL,

there is time limitation for students to complete the given writing task. They may need much more time for the piece of writing which they are expected to produce.

f) Audience

In written language, writers are selective with the language they use, whether formal or informal, according to the potential characteristics of the readers. Writers are expected to know the general characteristics of the targeted audience, their knowledge, and schemata (Brown, 2001).

g) Complexity

Students in the EFL and ESL contexts tend to use more complex sentences when compared to spoken language. Clause, sentence types, and the use of conjunction vary to a great extent in written language. However, as Brown (2001) states the complexity of written and spoken language belongs to different modes and they represent different types of complexity.

2.1.4. Characteristics of EFL and ESL Writing

Writing in English as a foreign language (EFL) and English as a second language (ESL) context differ from each other in terms of learning environments, characteristics of EFL versus ESL learners, EFL and ESL writing research and different teaching approaches (Reichelt, Lefkowitz, Rinnert, and Schultz, 2012). In her comparative study, Lefkowitz (2009) interviewed 20 instructors who taught in EFL and ESL context. She found that enrolment rate to EFL classes was higher and both class size and contact hours were important factors influencing success in writing. Reichelt et al. (2012:25) also point out that EFL writing instructors desired for more time and fewer students. ESL students have the advantage of unlimited exposure to target language when compared to EFL students. Lack of opportunities for exposure to the target language causes weaker integrative and more instrumental motivation for EFL learners. They interpret this fact as follows:

For FL students, contact with the L2 is often limited mostly to the artificial context of the classroom and is supplemented outside the classroom primarily by homework assignments that may or may not include writing. In general, then, FL students often have significantly less exposure to the FL than do ESL students.

EFL Students' motivation with regard to their peculiar learner characteristics is negatively affected. EFL students enrol in course in order to meet university language requirements in their fields of specialization or to study or work abroad. However, as Dörnyei and Schmidt (2001) state, their use of and exposure to the target language take place in a narrow and well-defined context (cited in Reichelt et al., 2012). ESL students come to a university writing class with a rich background in English when they are expected to write, however; EFL students have 0-3 years of language study.

Another difference between EFL and ESL writing arises from the research conducted. A great body of research has been devoted to ESL writing studies, but this is not the case for EFL writing. Researchers are expected to conduct more research on EFL writing context (Reichelt et al., 2012). Different teaching approaches adopted in the ESL and EFL context also affect the success in writing. Lefkowitz (2009) states in her study that EFL instructors usually employ form-focused and product-oriented approaches. In contrast to EFL instructors' insistency on grammatical accuracy in writing tasks, ESL instructors prefer to focus on content rather than linguistic precision and they emphasize the writing process instead of the final product. Reichelt et al. (2012:38) suggest a change in EFL writing instruction as follows:

Much is to be gained from a focus on teaching writing in the FL classroom because students often have weak writing skills in both their L1 and L2 and because a focus on FL writing instruction can facilitate overall TL acquisition, including the acquisition of grammar, increased fluency in oral expression, and knowledge of different cultures’ rhetorical forms for diverse genres. We recommend that FL writing instructors explore various types of writing assignments, choosing ones that fulfil purposes that are appropriate to the context.

Apart from writing instruction, the influence of EFL and ESL differences can be observed in general English courses as well. Bell (2011) states that understanding the fundamental differences of EFL and ESL contexts can make the teachers more effective. She states that ESL classrooms are in the countries where English is the dominant language. The students in these classrooms are visitors or immigrants, and there are different nationalities. Hence, students do not have a common culture and do

not share a native language. The ESL students need to use the language outside the class. They are exposed to English and English culture almost daily even though their language skills may limit their understanding. On the other hand, EFL classrooms are in the countries where English is not the dominant language. Almost all students share the same language and culture. The only native speaker may be the teacher. They have very few opportunities to use English outside the class. Learning English may not have a practical benefit for some of the learners. They have a limited exposure to authentic language. After defining two different classroom types, Bell focuses on the needs of ESL and EFL students in the classroom, and states that ESL students need;

1. English lessons providing hands-on activities which support students' immediate needs. If teachers have immigrant students who are struggling with how to fill forms, teachers should teach them to fill out forms. If they have foreign doctoral students, they should teach them how to talk to their supervisors.

2. Explicit cultural instruction. The students coming from different countries and cultures can be explicitly instructed with regard to English culture together with a comparison with their owns. This provides them to understand the culture of the target language, which is a helpful step towards fluency.

3. Bridges towards integration. ESL teachers may not consider themselves as a guidance counsellor. However, they should be ready to help students with their problems; for instance, they may need help while applying for a job online. ESL teachers are most probably will be the first person students ask for help.

On the other hand, Bell (2011) maintains that EFL students' needs are different. She states that EFL students need;

1. Lots of practice using English, especially orally. Teachers should encourage them to speak in the classroom, and help them with where to find opportunities to practice speaking English outside of the class.

2. Exposure to living English. EFL teachers should never attempt to make the students believe that English is a set of rules and words to memorize. They should make them expose to the authentic language as much as possible with the help of pen pals, non-traditional teaching materials, and field trips.

3. Reasons to learn English, and motivation to stick with it. EFL teachers should provide their students with reasons to communicate. This increases their motivation to learn the target language. Social networks are powerful tools for fulfilling it.

Bell's remarks on ESL and EFL students' needs in language learning process indicate that EFL students are disadvantageous with regard to their chances of being exposed to authentic language. The superiority of language learning in ESL context to EFL context is also emphasized by different researchers (Brecht, Davidson, & Ginsberg, 1993; Carroll, 1967; Diller & Markert, 1983; Freed, 1990; Lennon, 1995; Spada, 1986; Tonkyn, 1996; Freed, 1995; Huebner, 1995). They state that studying a foreign language in ESL context has a considerable impact on language learning. In this context, Longcope (2009) conducted a research to describe and compare ESL and EFL learning context with respect to the availability of conditions that facilitate second language acquisition. He states that the subjects report having more L2 contact in the ESL context than in the EFL context. However, the nature of that contact is more conducive to language learning as ESL context makes available more comprehensible input and output. His findings make us understand the differences between two language learning contexts better.

2.2. Teaching Writing

In both second and foreign language education, the ability to write and writing instruction are progressively becoming important in our modern world where communication across languages becomes essential. Because of educational, business, and personal reasons, the ability to write and speak is gaining recognition as an important skill (Weigle, 2002). The need for teaching writing is emphasized as a cornerstone in language education by many researchers from the past to the present. Murray (1973), for example, enumerates a number of reasons for why writing should be

taught in language classes. The writer explains seven good reasons why teachers should be concerned about teaching writing. Murray (1973:1235) notes that:

- Writing is a skill which is important in school and after school.

- Writing, for many students, is the skill which can unlock the language arts. - Writing is thinking.

- Writing is an ethical act, because the single most important quality in writing is honesty.

- Writing is a process of self-discovery.

- Writing satisfies man's primitive hunger to communicate. - Writing is an art, and art is profound play.

The above-mentioned reasons may not be suitable for all students, but the primary aim in language education is to open the doors and students should be offered new opportunities to develop their skills. The opportunities to write for the above-mentioned reasons should also be provided by the teachers (Murray, 1973).

In order to enhance the efficiency of writing instruction, various research has been conducted in the field of second and foreign language writing. Brown (2001:346-356) recommends that teachers follow some principles while designing writing techniques as in the followings:

1. Incorporate practices of "good" writers. 2. Balance process and product.

3. Account for cultural/literary background. 4. Connect reading and writing.

5. Provide as much authentic writing as possible.

6. Frame your techniques in terms of prewriting, drafting, and revising stages. 7. Strive to offer techniques that are as interactive as possible.

8. Sensitively apply methods of responding to and correcting your students' writing. 9. Clearly instruct students on the rhetorical, formal conventions of writing.