* i i 4 * i ‘ ,

P£

/404

•Aáa.

1993

ffi 6«»rss::-!3i

шийтхя ■

,

тк

яшттп

шіш

ішш-Miîî ш м о» еншбтЕййш

íbifi îïCï.r?'?:«« Ά Ψ Μ ŞT'^ I ,«i I· ■ * Г . ·:;TT£f: T!!· Ti:í£

t)F

Н

іІ

йіілч]£S

уччг; niivs-í-iW?· ί;.ϊ ¿ ,?Г»Г-і*5 Гчï’.ir^fïStî '**·■.'f >* .1™ ■> .“ ' Г ѵг ^-.'î··" / w У' . *»··.ι— « · •►■•.A· w , д, .fc. ν'* 75* £S5L?-^vH ÄS Д >'■"; л'£Ш|?EFL CCMPOSITION ASSESSMENT: THE RELATIONSHIPS BETWEEN TEACHER-RATER BACKCaiOUND CHARACTERISTICS

AND READER RELIABILITY

A THESIS

SUBMITTED TO THE FACULTY OF HUMANITIES AND LETTERS AND THE INSTITUTE OF ECONOMICS AND SOCIAL SCIENCES

OF BILKENT UNIVERSITY

IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE D E C a ^ OF MASTER OF ARTS

IN THE TEACHING OF ENGLISH AS A FOREIGN LANGUAGE

— S u Mu.

farafindcn tc^iflanm igtir.

BY

ALI SIDKI AGAZADE AUGUST 1993

pe

-AS2

т з

ABSTRACT

Title: EFL composition assessment: The relationships between teacher- rater background characteristics and reader reliability

Author: Ali Sidki Agazade

Thesis Chairperson: Dr. Linda Laube, Bilkent University, MA TEFL Program Thesis Cotmdttee Members: Dr. Dan J. Tannacito, Dr. Ruth A. Yontz,

Bilkent University, MA TEFL Program

It is common knowledge among composition researchers that different composition readers judge the same compositions differently due to certain reader variables. This controversial issue leads to a further problem, which is best termed as the reader reliability and unreliability dichotomy. While it is assumed that some ccatposition rater background characteristics influence reader reliability, few studies have investigated the rela

tionships between rater background characteristics and reader reliability. This research study explored the relationships between composition teacher-rater background characteristics and reader reliability at the Eastern Mediterranean University Preparatory School in the Turkish Republic of Northern Cyprus.

A background information questionnaire consisting of fourteen items was first developed, and then administered to 47 teacher-raters who had scored an EFL composition achievement test consisting of one prompt. The research participants scored a total number of 1191 student compositions. The arrangement of the scoring process was such that two teachers indepen dently scored a subset of about 30 compositions using a twenty-point analytic scale. The researcher was also provided with the composition assessment record prior to the administration of the questionnaire.

The two sets of scores cissigned to the compositions in each subset were correlated in order to identify the reliable and the xmreliable readers within pairs. At this point, the dependent reliability variable was created so that it could be regressed with the independent background characteristics variables. One of the 14 independent variables —

composition examination papers — was excluded from the stxody, and the analysis was done with 13 independent variables. This variable was

excluded because all of the raters' responses were "yes" to this background characteristic.

The analysis did not yield any statistically significant relation ships between the depaident variable and the independent variables group. Therefore, the alternative hypothesis stating that there are EFL canrposi- tion teacher-rater background characteristics related to reader reliability was rejected, and the null hypothesis stating that there are no EFL

corrposition teacher-rater background characteristics related to reader reliability had to be accepted.

Only one rater out of the 47 raters was identified ëis unreliable. However, it is believed that factors other than background characteristics, such as fatigue, physical distractions, or subconscious rebellious behavior against the testing administrators affected his/her reading performance. This conclusion was supported by some collected data and insitu observa tions.

IV

BILKENT UNIVERSITY

INSTITUTE OF ECONOMICS AND SOCIAL SCIENCES M A THESIS EXAMINATION RESULT FORM

Augiast 31, 1993

The exanuning cotmdttee appointed by the Institute of Economics and Social Sciences for the

thesis examination of the MA TEFL student

Ali Sidki Agazade

has read the thesis of the student. The conmittee has decided that the thesis

of the student is satisfactory.

Thesis Title: EFL composition aissessment: The relationships between teacher-rater background

characteristics and reader reliability

Thesis Advisor: Dr. Linda Laube

Bilkent University, MA TEFL Program

Conmittee Members: Dr. Dan J. Tannacito

Bilkent University, MA TEFL Program

Dr. Ruth A. Yontz

V

We certify that we have read this thesis and that in our combined opinion it is fully adequate, in scope and in quality, as a thesis for the degree of Master of Arts.

(Comnnittee Mannber)

Ruth h/. Yqiitz (Committee Member)

Approved for the

Institute of Econcmics and Social Sciences

ACKNCWLEDGEMENTS

I am grateful to my thesis advisor, Dr. Linda Laube, for her invalu able guidance throughout this research study; and to the MA TEFL program

director. Dr. Dan J. Tannacito, and Dr. Ruth A. Yontz, for their advice and suggestions on various aspects of thisresearch study.

I am particularly indebted to the president of the Eastern Mediterra nean University in the Turkish Republic of Northern Cyprus, Prof. Dr. özay Oral, and the chairperson of the University's Board of Trustees, Mr. Burhan Tuna, for their joint decision to give me a one-year leave with pay to attend the Bilkent MA TEFL program.

I must also express my deepest gratitude to the other administrators of Eastern Mediterranean University for their moral support, especially to the Dean of the Faculty of Arts and Sciences, Dr. Ayhan Bilsel, and the former head of the English department. Dr. Nüvit Mortan; to the former director of the preparatory school, Mr. Ali Kılıç; to the former assistant director of the preparatory school, Mr. Fikri Asal; to the former English service courses coordinator, Ms. Bahire Efe özad; and to the present assistant head of the English department, Mr. Ahmet Hidiroglu.

My most special thanks go to the present assistant director of the Eastern Mediterranean University Preparatory School, M r . Semih Şahinel, who gave me permission to conduct this research in the institution; to the present testing unit coordinator of the preparatory school, Ms. Melek Gül Şahinel, who provided me with the test information; and to the testing unit staff, who eissisted me in administering the composition teacher-rater

background characteristics information questionnaire.

Finally, I would like to dedicate this thesis to my beloved parents, Mehmet Vahip Agazade and Müsteyde Agazade, and my wonderful kid brother, Hasan Agazade, who supported, encouraged, and endured me through it all.

V I 1

TABLE OF CONTENTS

LIST OF T A B L E S ... viii

CHAPTER 1 INTRODUCTION TO THE S T U D Y ... 1

Background of the P r o b l e m ... 1

Purpose of the S t u d y ... 3

Problem S t a t e m e n t ... 4

Limitations and Delimitations of the S t u d y ... 5

D e f initions... 6

CHAPTER 2 LITERATURE R E V I E W ... 9

Introduction to Second Language T e s t i n g ... 9

Testing W r i t i n g ... 11

Direct Versus Indirect Tests of Writing ... 11

The Best Test of W r i t i n g ... 12

Essay Evaluation A p p r o a c h e s ... 15

Reader Reliability in Essay Evaluation ... 16

Selection of Essay Test E v a l u a t o r s ... 17

C o n c l u s i o n ... 18

CHAPTER 3 RESEARCH M E T H O D O L O G Y ... 19

Introduction... 19

Parti c i p a n t s ... 19

Data Collection Procedure ... 23

Data Analysis Procedure ... 24

C o n c l u s i o n ... 24 CHAPTER 4 R E S U L T S ... 25 Introduction... 25 Presentation of the D a t a ... 25 Analysis of the D a t a ... 35 Interpretation of the R e s u l t s ... 39 C o n c l u s i o n ... 40 CHAPTER 5 CONCLUSIONS ... 41

Recommendations for the Conposition Scoring Process ... 41

Inplications for Further S t u d y ... 42

BIBLIOGRAPHY ... 44

A P P E N D I C E S ... ...46

Appendix A: Permission Letter for Data Collection ... 46

Appendix B: EFL Conposition Teacher-Rater Background Information Questionnaire... 47

Appendix C: Table C-1 Ccxiposition Subsets and Their Rater P a i r s ... 51

Vlll

LIST OF TABLES

TABLE PAGE

1 Age Distribution of the R a t e r s ... 26 2 Turkish Raters' Experiences Living in English-Speaking Countries . . 27 3 Turkish Raters' Interactions with Native Speakers of English . . . . 28 4 ELT Experience Distribution of the R a t e r s ... 29 5 Average Number of Pages the Raters Wrote in English Each Month . . . 30 6 Raters' Experiences in Scoring English Composition Examination

P a p e r s ... 31 7 Average Number of Pages the Raters Read in English Each Month . . . .33 8 Distribution of the First S c o r e s ... 34 9 Distribution of the Second S c o r e s ... 35 10 Pearson Product-Moment Correlations within Rater Pairs ... 36 11 P Values for the Relationships between Quantitative Independent

Variables and Dependant Variable ... 37 12 P Values for the Relationships between Qualitative Independent

Variables and Dependent Variable ... 38 13 Confidence Intervals for the Relationships between Independent

CHAPTER 1 INTRODUCTION TO THE STUDY Background of the Problen

Language teaching professionals and language testing experts all know that there are two different tests available at their fingertips for

assessing writing skills and that, oftentimes, they face difficulty in making a choice between the two. Namely, these tests are direct tests of composition (essay tests) and indirect tests of composition (multiple- choice or fill-in-the-blaixk tests).

Although the administrators of large-scale testing organizations and schoolwide composition testing programs recognize the fact that direct tests of composition are tests of communicative ability in processing written discourse, they usually prefer using indirect tests of composition to using direct tests of composition because of practicality, reliability, and validity issues. But, the main reason for this preference is the ease in the scoring process of indirect tests of composition.

However, most of the people who are involved both in the teaching and testing of composition disfavor indirect tests of composition and argue that these tests measure editorial skills or learners' knowledge of

discrete pieces and patterns of the language rather than composition skills (Jacobs, Zinkgraf, Wormuth, Hartfiel, & Hughey, 1981).

Recently, schoolwide composition testing programs and even large- scale testing organizations all over the world have started favoring and

thus using direct tests

of composition. For instance, a direct test of composition, the TWE (The Test of Written English), Wcis incorporated into TOEFL (The Test of English as a Foreign Language) in July, 1986(Stansfield, 1986).

In spite of the shift from indirect tests of composition to direct

composition still persist. One of the most important problems is measure ment error. Direct tests of cornposition generally exhibit three different

sources of mecisurement error. These sources of measurement error are the rater, the test taker, and the test itself (Stansfield, 1988). However, the rater is usually the measurement error source of greatest concern for the administrators of large-scale testing organizations and schoolwide testing programs because a large number of raters for composition evalua tion are usually engaged. And, engaging a large number of raters for composition evaluation requires paying a great deal of attention to the consistency of performance across readers since different raters are likely to score the same conpositions differently due to their personal and

subconscious biases. It is a highly established fact in testing ccsntposi- tion that some raters cissign the same scores to the same conrpositions in a given set, whereas some other raters assign different scores to the same conpositions. This simply means that in the former situation the raters are reliable and in the latter unreliable.

Most of the time, because of the corrplexity of the reader reliability issue, we all take it «is natural or inevitable, and think that there is not much we can do about it. The major reason for this kind of attitude is

that we are uneible to see what really goes on in the raters' minds. Actually, this is the right point at which we should stop to ask a very inportant question because the conplexity of the issue starts from here onwards. This inportant question, which might well serve as a guide in trying to visualize the whole picture and arrive at some possible solu tions, has to do with the identification of the factor or factors determin ing reader reliability at both extremes. That is, on the one hand, what makes some raters reliable, and on the other hand, what makes some other raters unreliable? It is rather difficult to find an answer by means of

our intuition and observations though, to a large extent, they enable us to make some predictions as to the factor or factors involved. However, solid research should test these predictions. It is only then that we can be at a position to suggest solutions.

In light of the above discussion, it is vitally crucial for all conposition testing program administrators to consider the rater, a source of measurement error, especially when they are interested in the consisten cy of performance across raters, and hence the accuracy of test scores. Such a consideration is necessary because conposition testing program administrators and educators might be dependent upon ccsnnposition test scores in making some important decisions eüjout the testees through the interpretation of conposition test scores.

Purpose of the Study

At the Eastern Mediterranean University English Preparatory School in the Turkish Republic of Northern Cyprus, while I was serving both as an EFL instructor and a member of the testingoffice staff, I thought that

teacher-raters were careless, tired of reading examination paper piles one after another, and, perhaps, even reluctant to read examination papers not answered by their own students. I had taken it for granted that raters are liable to make idiosyncratic judgements. However, the prospect that the teacher-raters were deliberately not doing their job properly was making me furious.

We had been having each EFL conposition achievement test paper scored by two teacher-raters so as to acconplish a higher degree of reliability. However, prior to the scoring process, almost always, we, the members of the testing office staff had arguments as to which teachers would be paired and assigned to evaluate the EFL conposition achievement test papers:

rienced teachers, male teachers with female teachers, male teachers with male teachers, female teachers with female teachers; what? If we had been able to correctly anticipate both the reliable and the unreliable EFL connposition teacher-raters, our job would have been easy. However, when I started taking courses leading to my HA TEFL degree at Bilkent University, in Ankara, I realized that I had not been making correct predictions

because the difference in the reader reliability apparently resulting from the idiosyncratic judgements the teacher-raters make might perfectly stem frcsm their own background characteristics such as their age, sex, teaching experience, literacy habits, teaching qualifications and so forth.

If this is the case confronting us, it is essential to investigate EFL conposition teacher-rater background characteristics because being aware of what they are can assist the administrators of large-scale testing organizations and schoolwide testing programs in appropriately deciding which raters to engage for connposition evaluation. Thus, the primary objective of the present study is to identify and quantify the probable significant relationships between EFL carposition teacher-rater background characteristics and reader reliability.

Problem Statement

Since rater background characteristics vary, reader reliability of EFL compositions also varies. Therefore, it is absolutely possible to argue that there are two different sets of rater background characteris tics, each of which relates to reliable and unreliable readers. Then, it is necessary that we undertake a correlational study in order to determine each set of rater background characteristics of the reliable and unreliable readers respectively.

The relevant research questions which are being addressed here then are as follows:

(1) Which teacher-raters of the Eastern Mediterranean University Preparatory School teacher-rater population who scored the

conposition subtest of the English achievement test administered on 15 January, 1993 are reliable conposition readers?

(2) Which teacher-raters of the Eastern Mediterranean University Preparatory School teacher-rater population who scored the

composition subtest of the English achievement test administered on 15 January, 1993 are unreliable conposition readers?

(3) What are the EFL conposition teacher-rater background character istics of the reliable readers?

(4) What are the EFL conposition teacher-rater background character istics of the unreliable readers?

Thus, the null and the alternative hypotheses underlying the current study are as follows in turn:

Ho "There are no EFL conposition teacher-rater background charac teristics related to reader reliability."

Hi "There are EFL conposition teacher-rater background character istics related to reader reliability."

Limitations and Delimitations of the Study

The EFL conposition teacher-rater background questionnaire was the only instrument which was used for data-gathering in the study. Although particular care was taken to make the questionnaire as comprehensive as possible, there might have still been sonoe other questions to be asked in the questionnaire. This was one of the limitations the questionnaire itself imposed on the study.

Another limitation was the participants', the EFL conposition teacher-raters', self-reports on the questionnaire, which might have influenced the reliability of the data collected. In other words, we

cannot estimate to what extent we can rely on the accuracy of the self- reports since seme individvials might knowingly or unknowingly conceal the facts. Thus, this limitation might have reduced the relieibility of the data collected, as well as the overall reliability of the results of the research study. For instance, two participants reported that they wrote an average number of 300 pages each in English each month (see Table 5). This is an incredulous self-report.

The choice of only one EPL composition assessment site limited the scope of the research study in terms of the quality of the compositions and the range of the rater background characteristics. Consequently, the

results might not have been generalized to other EFL composition assessment sites.

The last limitation of the stiody was the population size of the EFL composition teacher-raters, as well as of the student essayists. This limitation might have influenced the generalizability of the results to other EFL composition assessment environments with larger teacher-rater and essayist populations.

There were two major delimitations of the study. One of than was the choice of the trained composition teacher-rater population, and the other- one was that there were not any advanced level essayists available. These two delimitations might have affected the range of the data collected. Definitions

Reliability is one of the terms that appears very extensively in the language testing literature. Since it is directly relevant to this

research study, it needs to be defined in order to avoid confusion.

Simply, it is related with accuracy of measurement. Henning (1987) states that "this kind of accuracy is reflected in the obtaining of similar results when measurenent is repeated on different occasions or with

different instruments or by different persons" (p, 73). Here, Henning talks about varioias kinds of relisibility. That is, "different occasions," "different instruments," and "different persons" refer to test-retest reliability, parallel form reliability, and reader reliability respective ly. Each of these three kinds of reliabilities assumes a different source of measurement error: the examinee, the test, and the reader in order. Test-retest reliability refers to the consistency of the examinee's performance at different administrations, parallel form reliability the consistency of performance on different versions of the test, and reader reliability the consistency of reader performance (Stansfield, 1988). Reader reliability is further divided into two categories: Intrarater reliability, which is the consistency of performance by a single reader, and interrater reliability, which is the consistency of performance across readers.

In this research study it was assumed that the greatest source of measurement was that of the reader since there were different pairs of readers for the subsets of the composition subtest. The terms reader, rater, and scorer are synonymously used. In addition, the definition of the term reader reliability used is the one borrowed from Wayne and Auchter (1988): "the consistency with which different readers in a given scoring session award the same scores to a given set of essays" (p. 2).

Furthermore, another term which is very closely related to the term reliability needs to be defined. It is the concept of validity. In fact, the concepts reliability and validity are the conplementary aspects of a connvon concern in measurement (identifying, estimating, and controlling the effects of factors that affect test scores) (Bachman, 1990). Validity can briefly be defined as the extent to which the test measures what it sets out to measure (Hamp-Lyons, 1991). We will not elaborate on the concept of

validity much since it is not directly relevant to this research study. However, to sum it up, it should be made clear here that a test should be both reliable and valid because reliability is the necessary condition for a test to be valid. This is one of the most important testing principles.

In the language testing literature five major kinds of validity are discussed: face, content, construct, predictive, and concurrent (Davies, 1990). However, face and content validity, which are indirectly relevant to this research study, will only be defined. Face validity is concerned with the fairness of the test for the testees, whereas content validity is concerned with the coverage of the sartples of the main items taught. In this respect, these two terms can even be considered synonymous. Thus, validity is used as an umbrella term to refer either to face validity or to content validity throughout the text.

CHAPTER 2 LITERATURE REVIEW Introduction to Second Language Testing

In instructional contexts, testing is undoubtedly an integral part of teaching because it can provide learners, teachers, and even administrators with some useful information that can serve as a basis for improvement. However, in the past, quite a large number of tests showed a tendency to isolate testing from teaching. Both teaching and testing are interrelated in such an intimate way that it is almost always impossible to work in either field without being constantly concerned with the other (Heaton, 1988).

Oiler (1980) stated that the developments in testing seem to be related to trends in language teaching methodology. Madsen (1983) agreed with him, in a way, by saying that "language testing today reflects current interest in teaching genuine conmunication, but it also reflects earlier concerns for scientifically sound tests" (p. 5).

If we take a historical view of the development of second language testing, we can easily see that, so far, there have roughly been three stages: intuitive (subjective), scientific, and cormunicative stages.

During the eighteenth century and the early nineteenth century, testing was in its intuitive, subjective, or, so to speak, pre-scientific stage because it was dependent upon the highly personal judgments teachers and administrators made. Teachers and administrators were both untrained in testing as far as the long pre-scientific language testing era is concerned.

Then, parallel to the innovative improvements in some other disci plines such as linguistics, psychology, and statistics, testing came to a scientific stage. This was the time when objective language assessment was emphasized. A great number of drastic changes came into being during this

so-called scientific era of remarkably considerable sophistication. One of the most significant of all changes was probably the appearance of linguis tically trained testing experts. These specialists started to argue that subjective writtoi tests were not reliable measure of language ability due to their peculiar scoring procedure and they constructed objective tests consisting of recognition items. In short, their having held the fascinat ing and persuading idea that objective, or, what is also called, multiple- choice type tests could be scored consistently, easily, and fast facilitat ed the replacanent of subjective written tests.

Thereafter, when the comnunicative language teaching approach was introduced, people began searching for appropriate means for assessing real ccninunication ability in the second language. This is what second language testing is mainly interested in today. In this cotnnunicative era, the major problem is that we want to go beyond testing isolated langxxage elements because communicative tests require testing how well second language learners can function in their second language when they attenpt to conmnunicate orally or in writing. It is obvious that objective tests are not sound enough to achieve this important goal. Carroll (1980) says "Some aspects of language proficiency cannot be measured by solely objec tive techniques. This is generally true of the more active and productive aspects of competence — speaking, writing, pronunciation, and fluency" (p. 519). The cloze test, which is the global language performance

measure, seems to satisfy this testing goal by connbining the best features of both subjective and objective tests. However, it is still insufficient, to some extent since it does not put learners into actual canmunication process. Therefore, in the case of comnnunicative writing skill, for instance, it is arguable that second language learners absolutely need to do actual writing, and this can only be tested through the traditional

essay test. All we may try to do is to improve or devise a better scoring procedure, which can yield the highest possible scorer reliability, since the traditional essay, or the direct test of writing demonstrates a high degree of validity. In this communicative testing era, it is then vitally important to make use of both subjective and objective tests simultaneously for attaining the overall testing goals. In this way, a good balance is likely to be obtained.

Testing Writing

In order to be able to discuss what "testing writing" is, it is indeed essential to know what the writing process is. Harris (1969) defines it as "a highly sophisticated skill combining a number of diverse elements, only some of which are strictly linguistic" (p. 69). He also lists five such general elements that most educators would agree on: "con tent, form, grammar, style, and mechanics."

Direct Versus Indirect Tests of Writing. What are the tests used for testing writing? Hartp-Lyons (1991) distinguishes between two "writing tests" (p. 5); that is, direct versus indirect tests of writing. According to Hamp-Lyons, direct tests of writing are the "tests that test writing through the production of writing" whereas indirect tests of writing are the "tests that claim to test writing through verbal reasoning, error recognition, and other measures that have been shown to correlate fairly highly with measured writing ability."

Hamp-Lyons discusses some characteristics of direct and indirect tests of writing. The characteristics that belong to a direct test of writing are as follows, according to her:

1. At least one piece of continuous text of 100 words or longer actually, physically written by each testee;

2. Providing the testee with a set of instructions and a text.

picture, or other prompt material so that s/he is given consider able гост within which to create a response to the pronpt;

3. At least one human reader-judge who gets prepared or trained before the essay evaluation process reads every writing sample written by a testee;

4. All readers have some sort of с с ш ю п rating scale;

5. Readers' responses to the writing are expressed as numbers not as ccmnents.

Similarly, the following are the characteristics that belong to an indirect test of writing, according to Hamp-Lyons:

1. The testee does not write continuous prose but rather chooses the answer s/he thinks is the best from a given set of possible

answers;

2. There is no room for personal interpretation by the test taker; 3. Training is not needed to score the test;

4. Readers have answer keys that were produced by the test constructors;

5. The test reports scores as numbers not as conments.

As it can clearly be seen, the only characteristic ссятпюп to both direct and indirect tests of writing is the numerical scoring.

The Best Test of Writing. Unfortunately, there have been long arguments as to which one of the two tests of writing to adopt, but it is not that sinple to decide since each test of writing has its own strengths and weaknesses. Some people have favored the direct test of writing while some others have disfavored it.

Here are sonne rationales from those who have favored the direct test of writing in their defence:

1. Direct tests of writing require students to organize their own

13

ideas, and express than in their own words. Therefore, direct tests of writing measure certain writing abilities more effec tively than do indirect tests of writing;

2. Direct tests of writing motivate learners to inprove their writing. If tests do not reqviire actual writing, many learners will neglect the development of this skill;

3. Direct tests of writing are much easier and quicker to prepare than indirect tests of writing.

On the other hand, opponents of the direct test of writing raise the following objections:

1. Direct tests of writing are unrelieible measures because students perform differently on different topics and on different occa sions. In addition. The scoring of direct tests of writing is of subjective nature;

2. In producing written texts, learners can cover up weaknesses by avoiding problanns they find difficult. This is impossible with well-prepared indirect tests of writing;

3. Direct tests of writing require much more scoring time than indirect tests of writing. Thus, direct tests of writing add to the expense and administrative problems of large-scale testing. Harris (1969), however, sees no reason for such a debate and claims that both parties have been unable to come to a consensus due to their one sided fixed attitudes although it is possible to take the 'moderate

position' in light of some research findings (p. 70). Then, he sutrmarizes the 'moderate position' as the following:

1. Well-prepared objective tests of the language skills have been found to correlate quite highly with general writing c±iility, as determined by the rating of actual samples of free writing. Thus

in situations where the scoring of ccjrpositions would be unfeasi ble (as in some large-scale testing operations), objective tests can be used alone as fairly good predictors of general writing skill;

2. At the same time, it is now clear that there are ways to adminis ter and score direct tests of writing so that they, too, may be used by themselves as reliable instruments. Put briefly, high reliability can be obtained by taking several samples of writing from each student and having each sample read by several trained readers. Thus the classroom teacher who lacks the experience and/or the time to prepare indirect tests of writing ability, or who feels strongly aibout the pedagogical value of testing writing through writing, can use direct tests of writing with a reason able degree of confidence;

3. Inasmuch as both direct and indirect tests of writing have their own special strengths, the ideal practice is undoubtedly to measure writing skill with a combination of the two types of tests, and it is recommended that this procedure be followed whenever conditions permit. Such a combination will probably produce somewhat more valid results than would either of the two types of measures used by itself.

Although there is truth in what Harris says, we should be cautious when losing indirect tests of writing because more recent research has cast siispicion on their validity. For instance, Wesche (1987) claims the

following:

Indirect measures are often favored for reasons of practicality. There may be some cases where results of indirect tests correlate quite highly with more direct measures of criterion performance.

However, in any given case, this must be demonstrated. In communica tive testing, it would seem that our tests should be as direct as possible, and that any indirect measures must be shown reliably predict the criterion performance in real-life language use or at least to have concurrent validity with more direct measures (p. 377). Essay Evaluation Approaches

There are two essay evaluation approaches. These approaches are holistic scoring and frequency-count marking (analytic scoring) approaches

(Cooper, 1977).

Holistic scoring entails one or more markers awarding a single mark each, based on the total irrpression of the piece of writing ais a whole. As it is possible for an essay to appeal to a certain reader but not to

another, it is largely a matter of luck whether or not a single examiner likes a particular script. As has been demonstrated, the testee's score is a highly subjective one based on a fallible judgement, affected by fatigue, carelessness, prejudice, and so forth. However, if assessment is based on several fallible judgements, the net result is far more reliable than a score based on a single judgement.

Frequency-count marking is a procedure which consists of counting the errors made by each testee and deducting the number from a given total. Frequency-count marking is more objective but less valid than holistic scoring. As a result of this, frequoicy-count marking is not usually recommended. Since no decision can bereached about the relative impor tance of most errors, the whole scheme is actually highly subjective. For example, should errors of tense be regarded as more important than certain misspellings or the wrong use of words? Furthermore, as a result of

intuition and experience, it is fairly common for a scorer to feel that an essay is worth several marks more or less than the score s/he has awarded

and to alter the assessment accordingly. Above all, frequency-count

marking unfortunately ignores the real purpose of essay writing — comnuni- cation; it concentrates only on the negative aspects of the writing task, placing the students in such a position that they cannot write for fear of making mistakes. The consequent effect of such a marking procedure on the

learning and teaching of the writing skills can reverse the intention to develop skills.

Reader Reliability in Essay Evaluation

There are a nurtber of connplex factors which cause essay readers to vary in their judgements of the quality of essay tests. What are these complex factors, then? Some of them are the individtial readers' standards of severity, their ways of distributing scores along the scale, their inconsistencies in applying the standards, their reactions to certain elements in the evaluation or the papers, and their values for different aspects of an essay (Jacobs et a l ., 1981).

The reader variable mentioned above can affect the reliability, or consistency, of essay scores. Therefore, it is essential to compute reader reliability. There are two types of reader reliability estimates:

intrarater reliability and interrater reliability. The former indicates how consistent a single rater is in scoring the same set of essays twice with a specified time interval between the first and second scoring.

However, the latter, estimates the extent to which two or more raters agree on the score that should be assigned to an essay. This simply means that intrarater reliability is involved when there is only one reader for the same set of essays. On the other hand, interrater reliability is involved when there are two or more readers for the same set of essays (Bachman, 1990).

Earlier, it was maintained that at least two readers are needed for

the sound essay evaluation. In this respect, holistic scoring is being advocated. However, in order to be able to end up with high interrater reliability estimates, it is necessary to train essay readers prior to the scoring process. Carlson and Bridgeman (1986) state that "when essays and raters represent different cultural perspectives, interrater reliability is likely to be lower than when both essays and raters come from a hcxnogeneous group" (p. 146). Here, the complication is apparently due to the interac tion between writer and reader variables. As far as English as a second language classes are concerned, the writer variable is not scsnething easily controllable, but the reader variable can be controlled through careful rater training. Controlling the reader variable is a wise thing to do since it means solving half of the problem.

Selection of Essay Test Evaluators

In large-scale and schoolwide essay testing, there are generally large numbers of raters, most of whom are usually from totally divergent backgrounds. Even though training is done before reading essays, some readers may still not be properly trained owing to the time constraint. Thus, administrators are obliged to select essay readers who are nKJst likely to be reliable. Similarly, if they know the most likely unreliable essay readers beforehand, they will be able to identify those who need more training.

It is assumed that some essay rater background characteristics relate to high reader reliability, whereas seme other essay rater background

characteristics relate to low reader reliability. What are these essay rater background characteristics relating to these extremely different reader reliabilities? Being informed about these two distinct categories of essay rater background characteristics will greatly help large-scale or schoolwide essay assessment program administrators.

Jacobs et a l . (1981), for exan^le, refer to some broad categories of essay rater background characteristics like "academic, experiential,

geographic, sexual, and racial," but they do not elaborate on them. Conclusion

In this chapter, the most relevant literature on English as a second language corposition testing has been reviewed in order to be able to learn the history of the problem, familiarize ourselves with the theoretical background of the problem, assess the strengths and weaknesses of previous studies, identify promising ways to study the problem, and develop a

conceptual framework and rationale for the present study.

It is hard to say that this primary purpose of this very chapter has been well achieved due to the lack of library research facilities here in Turkey and the researcher's inexperience. However, some evidence for the relationships between composition rater background characteristics and reader reliability has been gleaned from the literature. Nevertheless, studies showing relationships are difficult to find. This study will investigate whether such relationships can be demonstrated.

19

CHAPTER 3 RESEARCH METHODOLOGY Introduction

The main objective of this present research study is to determine the probable significant relationships between reader reliability and EFL

composition teacher-rater backgrotind characteristics. In order to be able to investigate the above-mentioned relationships, it is first necessary to collect two sets of data — composition test information and composition teacher-rater background characteristics — from an EFL conposition

assessment environment so that they can be related after identifying both reliable and unreliable teacher-raters. For this purpose, the graduate student-researcher collected such data and analyzed it.

In addition to the collection of the two sets of data, it was neces sary for the researcher to observe the conposition scoring process.

However, it was not possible to observe the carposition scoring process since scoring had been done before the research was conducted. Consequent ly, the researcher had to rely on a number of previous insitu observations he had made and the testing administrators' reports.

In this chapter, information as to the participants of the study, data collection procedure, and data analysis procedure is supplied and discussed. Under the heading of participants, information about the educational institution with which the participants have affiliation is also given.

Participants

The participants in this research study were two groups from the Eastern Mediterranean University English Preparatory School in the Turkish Republic of Northern Cyprus. One of these groups was the composition teacher-rater population. The other group was the student essayist population, who were indirectly involved in the research study. The

student essayist population was indirectly involved in the research study because the graduate student-researcher did not ask them to volunteer for writing compositions on any given prompt or prompts. Instead, the most recent composition assessment record was requested from the administrators of the educational institution concerned. As for the composition teacher- raters, all of them volunteered to participate in the research study when their participation was requested.

There were several reasons for the choice of this particular composi tion assessment environment. First, it was one of the large-scale composi tion assessment environments in the immediate neighborhood of the graduate student-researcher, with the problems of which he was quite familiar. The familiarity was due to the experience he had gained while he was on the same staff. Second, he wholeheartedly wanted to contribute to their testing system by suggesting seme solutions for the most persistent problem. Third, he had easy access to the type of data to be collected through permission.

The university involved is an English medium university. Admission to the university is by a multiple-choice entrance examination based on the high school curricula. Once the students pass this examination, they are all required to take an English proficiency exainination administered by the English Preparatory School unless they can submit an internationally

recognized English proficiency examination result with a satisfactory passing score before they are allowed to take their departmental freshman courses. If they do not pass this English proficiency examination, they then sit for an English placement examination; according to the result they study general English at the English Preparatory School for one or two years depending upon their eissessed English proficiency level.

This English Preparatory School administers three midterm

tions and a final one in each academic semester for each of three general English proficiency level courses — beginning, lower intermediate, and intermediate. The objective of these three courses is to bring the stiidents to lower intermediate, intermediate, and higher intermediate

general English proficiency levels respectively. The students who exit the program are at the higher intermediate general English proficiency level. In the first academic semester of the freshman year, besides their depart mental courses, they take a higher intermediate general English proficiency course offered by the English department service courses division, the objective of which is to take the students from the higher intermediate general English proficiaicy level to the advanced level general English proficiency level. Then, the students who succeed in this course take another course in the second academic semester of the freshman year, which is an advanced general English proficiency level course aiming to get the students to brush up their advanced level English. The primary purpose of all these English courses is to train the students in such a way that they can cope with their specialized departmental courses, which require high level of ability in listening, speaking, reading, and writing skills.

The English Preparatory School midterm and final examinations mentioned above consist of six separate subtests. These subtests are

listening, vocabulary, language features, reading, cloze, and writing subtests. The listening subtest can have a number of different formats, but vocabulary, language features, reading, and cloze subtests have multiple-choice format. The writing subtest, on the other hand, is a twenty-point scale direct test of writing in response to one prompt.

The scores of the two midterm examinations and the final examination for each level are combined into one conposite score, which determines the exit from each course program. The conposite scores are educationally

important in that they are the only decision making-criteria as to each course program exit. Therefore, the ccxiposite scores must be reliable so that they can confidently be interpreted. However, the writing subtest might contaminate some potential unreliability since it is subjectively scored. The prevailing writing subtest scoring procedure is analytic assessment practiced with two different trained teacher-raters for each different student group of about thirty students. This procedure is followed in order to increase composition teacher-rater reading reliabili ty. Another precaution taken in the current use is to have the examination papers of each student group evaluated by a conposition teacher-rater pair, the two members of which have not taught the student group because they might be likely to subconsciously favor some students. The two indepen dently assigned scores to every single composition by two composition teacher-raters are averaged unless there is a difference of more than four points between them. If a difference of more than four points is found between the ratings of the pair, the testing office staff members then ask a third connposition teacher-rater to independently score those composition examination papers. The three scores obtained are conrpared and the two closest ones are averaged.

Of course, more than two raters can be assigned to rate each ccsnposi- tion in order to increase the reader reliability; however, it is not

practical for this conposition assessment environment at the moment. In addition, the administrators of the institution do not know for sure whether the composition teacher-raters in question are reliable or not. They just assume that they are reliable since they have taken seme sinple precautions. In spite of these simple precautions, these composition subtest scores might still be unreliable. Therefore, it was necessary to conduct this present research study.

23

Data Collection Procedure

Before proceeding with the research, the graduate student-researcher received permission in writing for collecting data from the administrator of the Eastern Mediterranean University Preparatory School in charge of academic affairs after explaining the purpose of the research study (see Appendix A). First, the graduate student-researcher was given the most

recent composition assessment record, which is the results of the 15 January, 1993 English conposition achievement subtest. Second, the

graduate student-researcher pilot-tested the EFL composition teacher-rater background information questionnaire he had previously designed by using several composition teacher-raters different from the ones actually scored the midterm examination papers. After making the necessary modifications, the final version of the EFL composition teacher-rater background infor mation questionnaire (see Appendix B) was administered to all connposition teacher-raters who scored the 15 January, 1993 English composition achieve ment subtest papers. The aim for using this questionnaire was to collect data concerning the background characteristics of the EFL composition teacher-raters under consideration.

The two sets of scores for all Eastern Mediterranean University English Preparatory School students were used in the research study. The scores belong to all groups of students at the beginning, lower intermedi ate, and intermediate goieral English proficiency levels. Data sampling was not done so that the most possible reliable results of the data analysis could be obtained.

There were seme students who did not take the examination because of illness, and those students who were not allowed to take the examination because of not meeting the minimum class attendance requirement, as well as those students who took the examination but did not produce a piece of

writing. Thiis, the composition scores of the students in these three categories were not available. These absent students were not many in number so their absence did not reduce the expected sample size at all. Data Analysis Procedure

The data analysis was performed in three steps. First, the two sets of scores for each canposition subset were correlated by using Pearson correlation technique so as to conpute the correlation coefficients. After having found the correlation coefficients for all ccsiposition subsets, they were interpreted for distinguishing the reliable and unreliable EFL

cortposition teacher-raters within pairs. Second, each EFL composition teacher-rater background characteristic for reliedble and unreliable readers was analyzed by using t-test and chi-square analyses depending on the

qualitative/quantitative status of the background characteristic indepen dent varicible so as to investigate the relationship. Finally, all back ground characteristics were logistically regressed with the reliability dependent variable.

Conclusion

In this chapter, an introduction to the research methodology has been made, and then basic information about the participants of the study, the data collection procedure, and the data analysis procedure has been

presented. Seine other information such as the characteristics of the place where the research study was conducted has also been supplied in an

integrating fashion. In the next chapter, the analytical results of the research study are presented after the statistical description of the data is given.

25

CHAPTER 4 RESULTS Introduction

The aim of this results chapter is three-fold. The data are presented, and then analyzed. Then the results of the data analysis are discussed and interpreted.

Since this research study explored the relationships between EFL composition teacher-rater background characteristics and reader reliabili ty, the hypothesis that there are EPL conposition background characteris tics related to reader reliability was tested after reliable and unreliable readers within rater pairs were identified. The reader reliability is the dependent variable, and the rater background characteristics the indepen dent variables. The independent variables are the fourteen items in the questionnaire (see Appendix B). Thus, each rater background characteristic is discussed in order of presentation on the questionnaire.

Presentation of the Data

The total number of English connpositions written by the students was 1191. Because each test taker was instructed to write one composition on a given pronpt, the number is also equivalent to the overall test taker

student population. Each cotposition received two independent scores of 20 maximum points each. The total number of the readers for the conpositions was 47.

Since each rater pair scored a number of conpositions, the number of conpositions scored by a rater pair is, hereafter, called a cottposition subset. The total number of the conposition subsets studied was 42. Table C-1 téibulates the conposition subsets and their rater pairs (see Appendix C).

A close study of Table C-1 reveals that the ntmiber of the siibsets evaluated by a single rater is not the same. That is, sane raters

évaluât-26

ed only one subset, while some others evaluated two or three subsets. Age was the independent variable designated as the variable no. 1. The ages of the raters were between 22 and 59, and the most frequent age was 24. Table 1 shows the age distribution of the raters.

Table 1

Age Distribution of the Raters

Age Frequency % 22 3 6.4 23 6 12.8 24 10 21.3 25 7 14.9 26 5 10.6 27 2 4.3 28 2 4.3 29 2 4.3 31 1 2.1 32 2 4.3 33 1 2.1 35 1 2.1 37 1 2.1 43 1 2.1 48 1 2.1 55 1 2.1 59 1 2.1 Note. Mean = 28.13 ; SD = 8.10

As for the sex (variable no. 2) of these 47 raters, 12 (25.5%) of them were male, and 35 (74.5%) of them were female. In other words, the female raters were almost three times the male rater population.

As far as the native tongue of the raters (variable no. 3) is concerned, 13 (27.7%) of the raters were English native speakers, and 34 (72.3%) of them were Turkish non-native speakers of English. There is a difference of 21 (44.6%) between these figures.

of English which the researcher was interested in were their experiences in English-speaking countries (abroad), and the number of their interactions with native speakers of English in a year (interaction) — variable no. 4, and variable no. 5 respectively. Table 2 shows the Turkish raters' experi ences living in English-speaking countries (abroad), and Table 3 shows the number of their interactions with native speakers of English in a year

(interaction) respectively.

Table 2

Turkish Raters' Experiences Living in English-speaking Countries

27

Abroad (in weeks) Frequency %

0 19 55.9 4 3 8.8 6 1 2.9 8 2 5.9 9 1 2.9 12 2 5.9 16 1 2.9 24 1 2.9 52 2 5.9 104 1 2.9 208 1 2.9 Note. Mean = 15.38 ; SD = 40.02

As can be inferred from Table 2, the most frequent Turkish rater's experience living in English-speaking countries is zero. That is, 19 (55.9%) of the 34 Turkish raters had not been to any English-speaking country in their lives. The number of the Turkish raters who had the most experience living in English-speaiking countries (208 weeks) was only one (2.9%). The frequencies of the other Turkish rater experiences living in English-speaking countries were quite low. Generally speaking, this Turkish rater population had little experience living in English-speaking

28

countries.

When Table 3 is studied, it is seen that the lowest number of

interactions was 150, and the highest number of interactions was 330. The most frequent number of interactions was 200. This simply means that 11

(32.4%) of the 34 Turkish raters interacted with the native speakers of English 200 times in a year.

Table 3

Turkish Raters' Interactions with Native Speakers of English

Interaction (times in a year) Frequency %

150 1 2.9 160 1 2.9 180 1 2.9 195 1 2.9 200 11 32.4 240 6 17.6 250 3 8.8 300 8 23.5 315 1 2.9 330 1 2.9 Note. Mean = 238.82 ; SD = 49.39

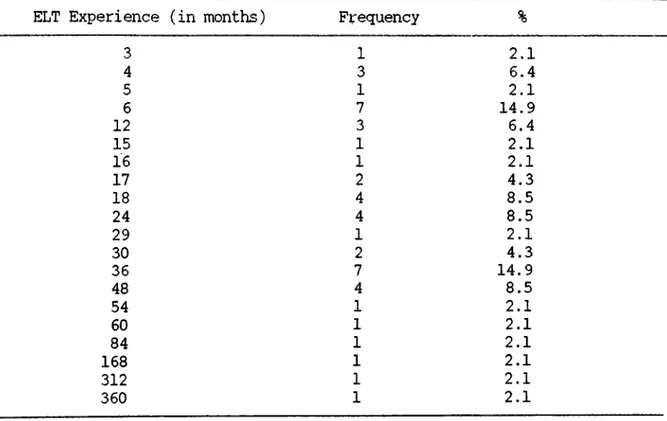

The next rater background characteristic (variable no. 6) the researcher was concerned with was the raters' English language teaching experiences (ELT experience). Table 4 displays the ELT experiotice distri bution of the raters. As can be seen from Table 4 the lowest ELT experi ence was three months, whereas the highest ELT experience was 360 months. The most frequent ELT experiences were 6 and 36 months. That is, one group of 7 raters (14.9%) had 6 months' ELT experience, and another group of 7 raters (14.9%) had 36 months' ELT experience.

ELT Experience Distribution of the Raters

Table 4

29

ELT Experience (in months) Frequency %

3 4 5 6 12 15

16

17 18 24 29 30 36 48 54 60 84 168 312 3601

31

7 3 11

2

4 41

2 7 41

1

1

1

1

12.1

6.4 2.1 14.9 6.42.1

2.1

4.3 8.5 8.52.1

4.3 14.9 8.5 2.1 2.1 2.1 2.1 2.1 2.1 Note. Mean = 40.47 ; SD = 68.86Another rater background characteristic under consideration was the average number of pages written in English each month (variable no. 7). Table 5 indicates the average number of pages the raters wrote in English each month. The lowest number of pages written was 2, while the highest number of pages written was 300. The most frequent average number of pages written in English each month was 20 by 10 raters (21.3%). Although there existed high numbers of pages written by some raters, the frequency of these high numbers of pages was very low.

30

Average Number of Pages the Raters Wrote in English Each Month

Table 5 Pages Frequency % 2 3 5 6 8 10 15 20 30 40 50 60 70 90 100 120 150 160

200

3002

1

31

2

1 3 10 41

2

31

1 3 3 21

1

2

4.32.1

6.4 2.1 4.3 2.1 6.4 21.3 8.5 2.1 4.3 6.4 2.1 2.1 6.4 6.4 4.32.1

2.1

4.3 Note. Mean = 59.98 ; SD = 71.28The highest English teaching qualification was another rater back ground characteristic (variable no. 8) investigated in this research study. Five raters (10.6%) had graduate degrees (MA/MS), one rater (2.1%) a

graduate diploma (DOTE), three raters (6.4%) graduate certificates (COTE), 35 raters (74.5%) undergraduate degrees (BA/BS), two raters (4.3%) diplo mas, and one rater (2.1%) a certificate. The most frequent highest degree was baccalaureate.

Pre-service training in teaching English composition (variable no. 9) was another rater background characteristic explored through the question naire. Fourteen raters (29.8%) took no pre-service training courses in teaching English composition, eleven raters (23.4%) as part of one course, eleven raters (23.4%) one course, and eleven raters (23.4%) more than one

31

course. Unfortunately, this leads to the deduction that 14 raters were conpletely untrained in English conposition teaching methodology.

Participation in reader group-training sessions before scoring English conposition examination papers (variable no. 10) was the next questionnaire item seeking information edDOut the raters in yes/no form. All of the 47 raters' responses to this item was yes (100%). This is not surprising because this was the institutional requirement.

As a rater background characteristic, raters' experience in scoring English composition examination papers (variable no. 11) wais also investi gated. Table 6 illustrates the raters' experiences in scoring English composition examination papers.

Table 6

Raters' Experiences in Scoring English Composition Examination Papers

Experience (in months) Frequency %

2 1 2.1 3 2 4.3 4 4 8.5 5 2 4.3 6 9 19.1 12 1 2.1 15 1 2.1 16 1 2.1 17 2 4.3 18 3 6.4 24 6 12.8 29 1 2.1 30 2 4.3 36 4 8.5 48 3 6.4 54 1 2.1 84 1 2.1 168 1 2.1 180 1 2.1 360 1 2.1 Note. Mean = 33.74 ; SD = 60.34