T.C.

YAŞAR ÜNİVERSİTESİ SOSYAL BİLİMLER ENSTİTÜSÜ

İNGİLİZ DİLİ VE EDEBİYATI ANABİLİM DALI YÜKSEK LİSANS TEZİ

EXPLORATIONS OF THE FREUDIAN UNCANNY AND THE DERRIDEAN ARCHIVE IN NEIL GAIMAN’S NEVERWHERE

Evrim IŞIK

Danışman

Yrd. Doç. Dr. Trevor J. HOPE

T.C.

YAŞAR ÜNİVERSİTESİ SOSYAL BİLİMLER ENSTİTÜSÜ

İNGİLİZ DİLİ VE EDEBİYATI ANABİLİM DALI YÜKSEK LİSANS TEZİ

EXPLORATIONS OF THE FREUDIAN UNCANNY AND THE DERRIDEAN ARCHIVE IN NEIL GAIMAN’S NEVERWHERE

Evrim IŞIK

Danışman

Yrd. Doç. Dr. Trevor J. HOPE

ii

YEMİN METNİ

Yüksek Lisans/Doktora Tezi olarak sunduğum “Explorations of the Freudıan Uncanny and the Derridean Archive In Neil Gaiman’s Neverwhere” adlı çalışma nın, tarafımdan bilimsel ahlak ve geleneklere aykırı düşecek bir yardıma başvurmaksızın yazıldığını ve yararlandığım eserlerin bibliyografyada gösterilenlerden oluştuğunu, bunlara atıf yapılarak yararlanılmış olduğunu belirtir ve bunu onurumla doğrularım.

23/12/2016 Evrim IŞIK

iii ABSTRACT Master’s Thesis

EXPLORATIONS OF THE FREUDIAN UNCANNY AND THE DERRIDEAN ARCHIVE IN NEIL GAIMAN’S NEVERWHERE

Evrim IŞIK Yaşar University Institute of Social Sciences

Master of Arts in English Language and Literature

The purpose of this master’s thesis is to examine and explore the Freudian formula t io n of the human psyche and the Derridean archive through the urban fantasy novel

Neverwhere by Neil Gaiman. Both approaches this thesis employs centre around a

metaphorical topography of conscious and unconscious domains in psychical/me nta l and material structures, which echoes Neverwhere’s richly and metaphorically drawn topography of the city of London. The city of London’s separated and antagonis t ic realms of London Below and London Above convey the very relationship between the conscious and unconscious psychical and archival domains. Whereas the human being represses the unwanted, the non-ideal, and the traumatic into its unconscious mind, the city of London also represses the unwanted, the non-ideal, and the traumatic into its unconscious underground space, London Below. Through explorations of the Freudian psyche and the Derridean archive in Neverwhere, this project demonstrates that the act of repression, far from effacing the repressed, produces the uncanny and leads to disorder; the encounter with the uncanny when the repressed returns, however, may also serve therapeutic purposes.

Keywords: urban fantasy, fantasy, archive, psyche, consciousness, unconsciousness, violence, mental topography, repression, Freud, Derrida

iv ÖZET Yüksek Lisans

EXPLORATIONS OF THE FREUDIAN UNCANNY AND THE DERRIDEAN ARCHIVE IN NEIL GAIMAN’S NEVERWHERE

Evrim IŞIK Yaşar Üniversitesi Sosyal Bilimler Enstitüsü

İngiliz Dili ve Edebiyatı Yüksek Lisans Programı

Bu tezin amacı, Neil Gaiman tarafından yazılmış olan Neverwhere adlı fantastik şehir romanını kullanarak Freud’un insan zihni formülasyonları ve Derrida’nın arşiv teorisini incelemektir. Bu tezde kullanılan yaklaşımların ikisi de, bilinçli ve bilinç siz zihinlerin yarattığı zihinsel topografiyi merkezine alan yaklaşımlardır ve bu topografi

Neverwhere’in zengin ve metaforik şehir tasviri ile örtüşmektedir. Londra şehrinin

birbirinden ayrı ve birbirine düşman iki farklı versiyonu olan London Above (Üst Londra) ve London Below (Alt Londra) şehirleri arasındaki ilişki, zihinsel ve arşivsel alanlarda karşımıza çıkan bilinçli ve bilinçsiz alanlarda da karşılık bulmaktad ır. İstenmeyen, ideal olmayan ya da travmatik olanı baskılayarak bilinçsiz zihnine göndermeye çalışan insan zihninin işleyişi gibi, Londra şehri de istenmeyen, ideal olmayan ya da travmatik olan tarihini, insanlarını ve hatta yapılarını baskılayarak yer altına itmektedir. Freud’un zihin ve Derrida’nın arşiv yaklaşımını bir roman üzerinde n inceleyen bu proje, baskılama eyleminin baskıladığı unsuru aslında yok edemediğini, baskılanan unsurun varlığını sürdürürken de uncanny (tekinsiz) hale geldiğini ancak tekinsiz olanın iyileştirici de olabileceğini göstermektedir.

Anahtar Kelimeler: urban fantasy, fantasy, archive, psyche, consciousness, unconsciousness, violence, mental topography, repression, Freud, Derrida

v

TABLE OF CONTENTS

EXPLORATIONS OF THE FREUDIAN UNCANNY AND THE DERRIDEAN ARCHIVE IN NEIL GAIMAN’S NEVERWHERE

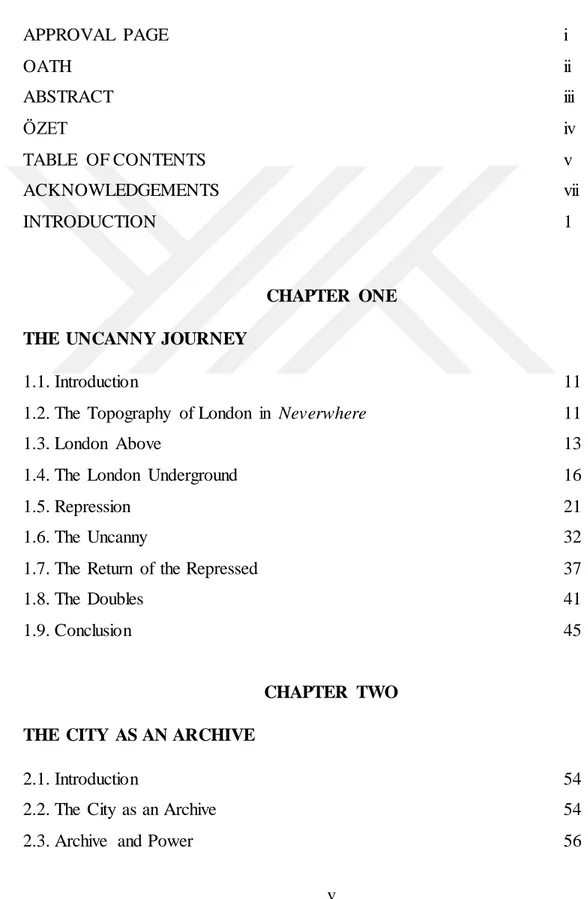

APPROVAL PAGE i OATH ii ABSTRACT iii ÖZET iv TABLE OF CONTENTS v ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS vii INTRODUCTION 1 CHAPTER ONE THE UNCANNY JOURNEY

1.1. Introduction 11

1.2. The Topography of London in Neverwhere 11

1.3. London Above 13

1.4. The London Underground 16

1.5. Repression 21

1.6. The Uncanny 32

1.7. The Return of the Repressed 37

1.8. The Doubles 41

1.9. Conclusion 45

CHAPTER TWO THE CITY AS AN ARCHIVE

2.1. Introduction 54

2.2. The City as an Archive 54

vi

2.4. Failure of the Ideal 60

2.5. Ambivalence and the Counter-Archive 67 2.6. The Archiviolithic and the Uncanny 71 2.7. Conclusion: The Therapeutic Value of the Uncanny 76

CONCLUSION 82

vii

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

First of all, I would like to express my heartfelt and immense gratitude to my advisor Dr. Trevor HOPE for his continuous and relentless support, amazing guidance, and endless patience throughout this process. He has always been and always will be my inspiration with his incredible kindness, diligent work, extensive knowledge, and wonderful ways of thinking. This has been a long journey for me, and without his support and patience, this work would never be possible. And secondly, I would like to thank my dearest friend Güliz ÖZGÜREL who has always been there for me to encourage, support, and guide me at times of despair.

EXPLORATIONS OF THE FREUDIAN UNCANNY AND THE DERRIDEAN ARCHIVE IN NEIL GAIMAN’S NEVERWHERE

INTRODUCTION

Born in the UK and now resident in the USA, the British author Neil Gaiman is a key figure in contemporary fantastic literature. Gaiman is a prolific writer of short stories, novels, comic books, audio theatre, films, and drama. Thanks to works that have reached audiences of all ages, Gaiman is listed as one of the top-ten living post-modern writers in the Dictionary of Literary Biography and he is also the New

York Times’ bestselling author of the novels Neverwhere, Stardust, American Gods, Anansi Boys, and Good Omens (with Terry Pratchett), as well as the short story

collections Smoke and Mirrors and Fragile Things. Some other notable works by Gaiman include the ground-breaking and widely acclaimed comic book series The

Sandman, the first comic ever to receive a literary award, “Coraline,” a bizarre

novella of two alternate worlds, and The Graveyard Book. Although his name has only recently begun to appear in academic and critical works, Gaiman is quite popular in reading circles, and is even referred to as “the literary world’s first iconic ‘rock star’” (Berman, “Neil Gaiman”).

Neverwhere, Gaiman’s debut novel, was first published by BBC Books in

1996 (“Neverwhere”). Gaiman, however, first wrote the story as the script of the low-budget TV mini-series of the same name for the BBC, and actively participated in the shooting process. On the very first day of the shooting, as he notes in the introduction to the novel, he decided to turn the series into a novel when he saw that the characters and scenes were not exactly as he had imagined them to be. Although the plot, characters, and even dialogues are almost identical, unlike its TV version, which did not receive much international recognition, the novel Neverwhere, which the official Neil Gaiman website defines as “a darkly comic urban fantasy set in London about an ordinary man, who, after helping a wounded girl he finds on the street, finds himself in an alternate London” (“Neverwhere”), has enjoyed great success worldwide.

Neverwhere is based on a clash between two different and even antagonistic

2

civilised, shiny, clean, and yet superficial urban space, and a darker, deeper, and more interesting London Below, which has long existed beneath London Above, and is yet invisible to and hidden from those who live in the upper city. As the alternative version of London Above, London Below, with its foul sewers, dark tunnels, tricky labyrinths, and abandoned subway stations, is an underworld kingdom of “the lost and the forgotten” (308), and is home to those who have fallen through the cracks of reality (126). The “other” space of the city harbours not only fantastical monsters and saints, murderers and warriors, angels and vampire-like creatures, talking rats, and a hierarchy of nobility, but also the homeless, sickly, smelly, unsightly people of today’s London. Furthermore, the buried and repressed past of the city, which is kept in “little pockets of old time…where things and places stay the same, like bubbles in amber” (229) fascinatingly fill the underground space with a rich, yet apparently non-ideal and thus repressed history of the city. The protagonist Richard Mayhew begins a journey of self-discovery and transformation into this uncanny double of London when he insists on “seeing” and helping a wounded, smelly, scruffy girl lying on a pavement, despite his fiancée Jessica’s threatening protests. Curiously, Richard begins to fade away from existence, and becomes a “non-person” (62) in London Above soon after the incident, and begins a challenging and enlightening journey into the depths of London Below, which also becomes a vital test for each character. At the end of Richard’s symbolic journey, the true identity of each character is either fully established or revealed in their hidden nature, and thus the hidden underground with its Victorian structures becomes a therapeutic and revelatory space where the personal defects of the characters are either fully exposed or healed.

Although the whole plot of the novel centres around Richard’s journey into the underground and his subsequent self-recovery, Neverwhere is not simply a story that narrates the fantastical adventures of its protagonist; it is a multi-layered work which portrays the city of London itself as another protagonist, and, by means of Richard’s journey, takes us to the city’s repressed and hidden past, people, and architecture. Whereas London Above is mostly a superficial city governed by the politics and ideology of the rich, London Below is remarkable in terms of the richness of its various spaces teeming with Victorian heritage and architecture and its curious residents, both of which Gaiman uses as a tool of social and political critique

3

and satire of the modern world. The novel, thus, raises various social and political questions regarding historiography as well as the issues of social stratification, discrimination, poverty, and homelessness through its carefully and richly drawn topography and spatiality of London Below. Although there are not many, the critical works written on Neverwhere also focus on the spatial and social issues that the novel raises rather than its fantastical aspect, but some critics also use the novel to examine how the genre of fantasy, particularly urban fantasy, in fact, addresses serious problems through metaphorical and mythological realms. Although some scholars, like Johanna Schüpbach, engage in a detailed analysis of the city’s richly mythological and historical realms and their contents without much discussion, most critics and academics who have worked on Neverwhere explore the questions of othering, liminality, visibility/invisibility, repressed urban history, and archaeology by focusing on the striking spatiality of the city of London depicted in the novel.

Julia Round, in a rather short article, “London’s Calling: Alternate Worlds and the City as Superhero in Contemporary British-American Comics,” published in the International Journal of Comic Art, employs a comparative perspective towards the comic book versions of From Hell by Alan Moore, Neverwhere by Neil Gaiman, and The Invisibles by Grant Morrison to explore the links between geographical duality and the superhero figure in literature. She notes that the texts she uses all take place “in a divided London whose segregation is maintained by processes of exclusion and opposition” (29), and she goes on to discuss how the city as a divided body, which can also be considered “as a psychoanalytic symbol of fragmented identity” (26), can be linked to the superhero figure. Regarding Neverwhere, Round focuses her arguments on how Richard, “a good Samaritan who gets sucked” (25) from London Above into London Below, becomes a superhero and a great warrior once he has recognised the fragmented structure of the city of London. After a brief discussion, she concludes by noting that “many of the characteristics of an alternate London accord with the superhero figure” if viewed as a psychological metaphor (30).

Another comparative essay named “The Sub-Creation of Sub-London: Neil Gaiman’s and China Miéville’s Urban Fantasy” by Dirk Vanderbeke focuses on the genre of urban fantasy and its political nature. Vanderbeke notes that the genre of

4

urban fantasy is a hybrid mix of “fantasy, magical realism, satire, utopia and dystopia, allegory, urban fiction, science fiction, steampunk, salvagepunk, and a few other genres” (161), and that its hybridity allows for a social and political critique of the modern world, albeit “in metaphorical and symbolic garb” (141). Referring particularly to China Miéville’s Un Lun Dun, James Clavell’s King Rat, and Neil Gaiman’s Neverwhere, Vanderbeke explores fantastic counter-cities that are simultaneous, inverted, imaginative, and satirical reflections of the modern world and their “eminently political” (141) structures. Gaiman’s London Above, according to Vanderbeke, is the

affluent, capitalist, consumerist world of our daily experience, the sphere in which the inhabitants have to work in shops and offices, where money is the usual means of trade and commerce, where machines work, where information technologies increasingly structure interpersonal communication and relationships, and where digital media inform us about the world and external reality. (148)

London Below, on the other hand, is the space where the city’s long past “is still alive, but it is not quite the past that can be learned from history books” (157). Vanderbeke, in his analysis of London Below, also draws on the conspicuous theme of space in the novel, and, referring to Foucault, notes that counter-cities of urban fantasies also serve as a “heterotopia of deviation” (148) where “out of the box” individuals whose behaviour, Foucault suggests, “is deviant in relation to the required mean or norm” (qtd. in Vanderbeke 148) are placed. Richard’s consignment into the underground, therefore, becomes a politically-motivated act of scapegoating and suppression that London Above resorts to in order to punish a “deviant” member of the society.

David L. Pike, another literature scholar, seems to be fascinated by Gaiman’s London Below, and explores the underground images of the city in two interrelated articles “Afterimages of the Victorian City” and “London on Film and Underground.” Whereas his earlier article “Afterimages of the Victorian City” focuses on the deeply Victorian aspect of London Below, his later “London on Film and Underground” centres around “the symbolic meaning of the London Underground” as cultural and cinematic space “more than those of other

5

metropolitan subway systems.” In both of his articles, Pike also employs a spatial perspective to discuss the matters of “the modern city and its hidden past” (“Afterimages” 261), strains of modernity, social invisibility, marginality, and other issues of the modern urban space, and argues that the topography in Neverwhere “allows it to imagine an otherworld without any separation between the modern space of the Tube and the more archaic and whimsical spaces of underground London” (“London on Film” 234). Putting much emphasis on the role and function of the underground in the nineteenth century, Pike says,

The underground was such a powerful paradigm in the nineteenth century because it visualized and fixed the meaning of the radical changes being undergone by cities such as London and Paris by giving them a spatial function in a broader conceptual framework of urban space. (“Afterimages” 263)

Comparing it to its aboveground counterpart London Above, Pike views the complex urban underground in London Below as a space of revolution, transformation, and transition not only in history but also in Gaiman’s novel, and comments on the transformative effect of the underground that follows the incident when “Richard Mayhew chooses to help what appears to be a young drug addict…[and] finds himself punished for the gesture: erased from the world above and cast into a strange underworld known as London Below” (“London on Film” 233). As I have already mentioned, juxtaposed with the modernity and modernism of London Above, the Victorian itself constitutes a substantial part of London Below, and Pike also draws attention to the paradoxes inherent in this juxtaposition and opposition of the two eras when he notes,

There is a complex ideology involved in determining what precisely a Victorian heritage is, especially from a preservation (and thus a legal and economic) point of view. For the modernists, the nineteenth-century underground was not ‘Victorian’; it was a counter-space to all that was Victorian…Whether a space of alienation or a space of potential liberation and revolution, subterranean London, and especially the Tube, was a quintessential space of modernity, and it remained ‘modern’, even as, in a material sense, it became more and more antique. (“Afterimages” 256)

6

According to Pike, the blurred boundaries between the material spaces of London Above and Below also apply to the blurred boundaries between the Victorian and the Modern. Therefore, although they are in rejection and denial of each other, both spaces and eras amalgamate to produce more blurred visions of the city.

“Outside/Inside Fantastic London” by Jessica Tiffin is another article that explores “contemporary fantasy novels which create and explore fantastic doubles to the modern city of London” (32) by comparatively referring to Gaiman’s

Neverwhere and Miéville’s Un Lun Dun. Tiffin is another strong advocate of the

fantasy genre’s suitability for discussing the problems of the modern urban space, and maintains that urban fantasy “has the potential to interrogate and expose assumptions about the cityscape, and particularly the metropolitan cityscape, through its literalizing and re-fashioning of the familiar” (37). Drawing on the concepts of the familiar and the other, Tiffin argues that the modern city tends to estrange its citizens, and thus simultaneously promises and denies “an absolute belonging” (32), and that the fantastic doubles to the real cities directly speak “to the individual’s experience of the city as othering, while simultaneously addressing and ameliorating that alienation” (38). Not only does she take Richard as the ‘other’ to the ideal citizens of London Above, but also suggests that London Below is the ‘other’ to London Above “in its subterranean dirt, tacky colour and characters who exemplify the underclass” (39). Richard Mayhew’s journey, according to Tiffin, is thus also a journey of othering and alienation which, in the end, helps him discover his true self and identity. She remarks that although London Above “functions for him as negative space, associated with lack of individuality or happiness,” Richard Mayhew’s journey “allows him to align London Below with self-discovery, his alienated self becoming a heroic self” (39).

Hadas Elber-Aviram’s article “‘The Past Is Below Us’: Urban Fantasy, Urban Archaeology, and the Recovery of Suppressed History” provides a finely-structured perspective that explores the relationship between archaeology and urban fantasy, which, she suggests, correlate “through a shared concern with the material history of the city” (1). Neverwhere and Tim Lebbon’s Echo City, according to Elber-Aviram, are narratives that are “overtly and deeply concerned with the material history of the city” (2), and “cast their protagonists into the symbolic role of archaeologists who

7

descend into the urban underworld to recover the city’s forgotten past” (1). Both cities “preserve a past that has been lost to the surface city, wilfully forgotten by its upper-class people,” argues Elber-Aviram, and suggests that the dynamics and politics of power relations are significantly influential in the processes of forgetting and repressing the threatening “authentic historical evidence” (3). She quotes from Orwell’s 1984: “Who controls the past controls the future: who controls the present controls the past” (qtd. in Elber-Aviram 3), and thus drawing attention to the hegemony of the rich in London Above, particularly embodied in a media-giant named Mr. Stockton, she remarks that Neil Gaiman’s Neverwhere “engages with these complexities, imagining hegemony not so much in terms of a privileged group, but as an aggressively dominant representation of London that expresses the power of such a group” (3). She rightly argues that the representation of hegemony in London “involves turning a blind eye to the city’s downtrodden; allowing them to plunge into an under-city termed ‘London Below’ that lies beneath the surface of the middle and upper-class ‘London Above’” (4), and continues to discuss how the past’s and Richard’s repression into the underground space is related with hegemony. The incident that turns Richard into an archaeologist, Elber-Aviram argues, helps him discover the repressed past and archaeology of the city “that have escaped the sterilisation of London Above to assume concrete dimensions on the underside” (4). The journey into the city’s past is also a journey into Richard’s own fears and limitations, and when he finally beats the nasty Beast of the Labyrinth – which Elber-Aviram relates to Freud’s conceptualisation of the return of the repressed – he also overcomes his fears. Nevertheless, when Richard returns to his old life in London Above, he simply discovers that “his bourgeoisie life has become…colourless” (8). Through the relationship between archaeology and literature, Elber-Aviram excavates the text itself to reveal the problematic relationship between historiography and ideology, just as Richard reveals his true identity by means of the underground.

As I have suggested, there are not yet many critical works written on Gaiman’s Neverwhere; however, those that I have reviewed mostly centre around the themes of homelessness, social alienation, marginalisation, and other problems of the urban space that Gaiman himself satirises by means of the rich topography and spatiality of London in his urban fantasy. In my reading of the novel, the themes of geographical duality and fragmented identity that Julia Round draws on have been

8

influential. On the other hand, the politically- and ideologically-motivated forgetting and repression of the “other,” the “deviant,” the non-ideal, and the threatening in modern urban space, a theme that has been explored by Vanderbeke, Tiffin, and Elber-Aviram, shall also often come up in my discussion of the city as a Derridean archive that depends on repression, segregation, and externalisation for its much-desired purposes of ideality and order. Also, David L. Pike’s discussion of the London underground as a space of transformation and transition and the paradoxes concerning the blurred boundaries between the Victorian and the modern have also been inspiring and guiding in my discussion of the past that has been repressed into the underground.

In addition to the issues and themes that have been explored by these critics, however, the novel also conveys rather intriguing and fascinating physical and metaphorical representations of the theme of “home” and other home-related themes. The main story in the novel begins when Richard takes a homeless girl home, despite his fiancée’s saying, “They all have homes, really” (24), only to lose his home and be erased from the memory of his home town. The homeless girl Richard has found on the street is significantly named after a domestic structure, and is literally called Door, and she possesses the magical gift and ability to “create doors where there are no doors” “unlock doors that are locked” and “open doors that were never meant to be opened” (326). And when Door opens a door and drags Richard into her home town, that is, London Below, “the homesickness engulf[s] him like a fever” (122; emphasis mine). “I want to go home,” writes Richard in what he calls a “mental diary” and he “mentally underline[s] the last sentence three times, [rewrites] it in huge letters in red ink, and circle[s] it before putting a number of exclamation marks next to it in his mental margin” (136).

With its various references to homes, homelessness, and losing and restoring home spaces, the novel also raises paradoxical questions regarding belonging and estrangement, homeliness and unhomeliness, placement and displacement, domestic and exterior spaces, insides and outsides, which mark the relationship between London Above and Below. The metaphorical topography of the city of London in the novel is particularly interesting in terms of the ambiguous borders between insides and outsides as well as the hidden outsides that are, paradoxically, still on the insides.

9

London Below is the unhomely, estranged outside space of the city of London, and is yet placed at the very heart of the city, beneath the ground, where such vital structures as the London Underground and London sewers silently, invisibly and yet actively work to provide the upper city with its defining features of order and cleanliness. The secret, hidden space of the city is home to the unwanted and non-ideal, thus repressed history, people, and even architecture of the city, and the deeper one goes down, the older the memories get. London Below is, thus, the unconscious space of London in which the repressed bits of the city’s memories actively and yet latently reside unbeknownst to the upper city.

As the second protagonist of the novel, the city of London itself is a dynamic organism with its conscious and unconscious territories, which lead me into a psychoanalytic reading of the city, and to Freud and, particularly, his home-related deliberations on the uncanny. London Below is the uncanny city that is at home but that is unhomely, thus generating strange feelings of the uncanny which Freud relates, in The Uncanny, with “something that was once familiar, and yet repressed, expelled from one’s conscious mind, and assumed to be forgotten only to return at a later time” (124). The city that resorts to repression, similar to human beings, also represses Richard after he helps Door, and he suddenly finds himself a fading memory in London Above, and begins his journey into the depths of the city’s unconscious realm. Richard Mayhew’s journey into the uncanny space after he himself turns uncanny in London Above, however, proves to be a therapeutic journey in which he not only discovers the unconscious aspects of his own psychical topography, but also the city’s repressed past preserved in London Below.

As we follow Richard into the depths of the counter-city, we also discover the repressed and hidden aspects of the city and its history. The city’s unconscious territory turns into an archive when it is understood that it is replete with the lost and the forgotten, leftover people, old-time pockets as well as derelict, rotting edifices of the Victorian period. It is home to people “who look like they have escaped from a historical re-enactment society,” people who remind Richard of “hippies,” “the albino people in grey clothes and dark glasses;” “the polished, dangerous ones in smart suits and black gloves;” “the tangled-hair ones who looked like they probably lived in sewers and who smelled like hell” (112). In its peripatetic markets, one can

10

barter for “Lovely fresh dreams!” “First-class nightmares!” “Rubbish!” “Junk!” “Garbage!” “Trash!” “Offal!” “Debris!” “Nothing whole or undamaged!” “Crap, tripe and useless piles of shit!” “Lost property!” (110) as well as “full bottles and empty bottles of every shape and every size,” “lamps and candles,” “a child’s severed hand clutching a candle,” “glittering gold and silver jewellery,” “old clothes,” “a dentist’s chair,” “unlikely things that might have been hats and might have been examples of modern art,” and even “a blacksmith’s” (111).

Whereas London Below teems with a plethora of London Above’s discarded aspects, we are also repeatedly drawn to see literal archives, that is, museums in London Above. And the archival aspect of the city raises further questions concerning remembering and collective forgetting at a collective level, which leads me to Derrida and his deconstructive theory of the archive. In his analysis of the archive, Derrida himself is in some ways reworking elements of Freud when he talks about the domestic inside, the domestic outside, and the prosthesis of the inside to explain the workings and dynamics of the archive. The Derridean archive is an archive of repression, suppression, segregation, and alienation which aims for a perfect order, to which the depiction of the city of London in Neverwhere conveys excellent examples.

11

1. CHAPTER ONE: THE UNCANNY JOURNEY 1.1. Introduction

The 20th-century Austrian psychologist and neurologist Sigmund Freud is probably one of the most important and renowned personalities in the fields of psychology and psychiatry thanks to his countless invaluable contributions to the disciplines. He is the founder of psychoanalysis and is also an influential thinker whose ideas radically changed the way we understand the human mind. With his interest in literature and deep understanding of human behaviour, Freud constructed a solid basis to the understanding of the human psyche and left the floor to various other successors who have so far helped us build an understanding of the motives lying beneath not only our own but also others’ intricate and at times ostensibly senseless actions and desires. In my reading of this fantastic adventure in the underground in Neil Gaiman’s first novel Neverwhere, I would like to exploit a Freudian perspective. In order to provide a basis for and to clarify the following deliberations on the uncanny, I shall begin by explaining and elaborating on the importance and implications of the conscious and the unconscious in the novel and in general, and how they relate to the identity of the city of London at its different levels. Then, I shall attempt at explaining the links between Freud’s unconscious-related conceptualisations and Richard’s underground journey, analysing the scenes which create the uncanny aspects within Richard’s quest. However, extending and also challenging Freud’s arguments concerning the uncanny, my focus will be on how the uncanny may also serve therapeutic purposes, as in Richard’s case.

1.2. The Topography of London in Neverwhere

Neverwhere is a multi- layered work that allows for various interpretations and

readings. Although the novel’s main storyline follows the protagonist Richard Mayhew’s enlightening underground experience in London Below, Gaiman’s elaborate depiction of London throughout the novel as a fragmented and stratified city is also quite intriguing. As Gaiman re-creates the city with its hidden layers, he also draws a picture of a living and dynamic organism that not only has its own needs, desires, memories, weaknesses, and fears but also possesses a unique mind similar to that of a human being. The structuration of the city in the novel recalls

12

Freud’s very own structuration of the human psyche, where he defines the mind as an agency consisting of two different levels of consciousness. In that regard, whereas the conscious mind seems to be represented in London Above, the stronger unconscious mind is represented in London Below in the fantastical world of

Neverwhere, and I shall discuss how the relationship between London Above and

London Below is paralleled in the relationship between the conscious and unconscious minds.

At the beginning of the novel, Richard Mayhew, the protagonist, helps and rescues a wounded girl, who, he learns, is the Lady Door from London Below. Door is a girl in ragged clothes, has a special gift for opening doors, and has ended up in London Above because she is pursued by two assassins, Mr. Croup and Mr. Vandemar. As Pike also suggests, however, “[Richard] also finds himself punished for the gesture: erased from the world above and cast into a strange underworld known as ‘London below’” (“London on Film” 233) upon this encounter with Door. All of a sudden, he finds out that no one seems to recognise or notice him anymore, as if he had faded out of existence, and this is also the moment he meets the magic world of London Below. Thus, he decides to go to London Below and find Door, who seems to be the only cause and the only possible remedy of his sudden non-existence in London Above. Yet, the Marquis de Carabas, a trusted friend of the Lady Door, makes it clear that he is not wanted in the world of London Below either, at the same time giving us a glimpse of these two interpenetrating worlds of London Above and Below:

‘Young man,’ he said, ‘understand this: there are two Londons. There's London Above – that's where you lived – and then there's London Below – the Underside – inhabited by the people who fell through the cracks in the world. Now you're one of them. Good night.’ (126)

After the encounter with Door, the novel introduces two Londons that, though bizarrely coexisting, are separated from each other in terms of space and temporality. What Gaiman calls London Above in Neverwhere is the part of London where people live (or seem to live) their supposedly proper and satisfactory lives in a socially appropriate manner. However, beneath the streets of London, there is

13

another, almost dystopic London, London Below, with its underground labyrinth of sewers, abandoned tube stations, and queer residents. As it turns out, London Below with its jumbled layers is also the part of the city where London Above’s memories and knowledge as well as fears and doubts are stored and, when necessary, repressed into the depths of the city. The topography and structuration of the city of London in

Neverwhere, therefore, bears an almost perfect resemblance to what Freud calls the

mental apparatus (or the topographic structure of the mind). Whereas London Below corresponds to the darker, deeper unconscious mind of the Freudian psyche, as I shall explore, London Above is the conscious mind of the city.

1.3. London Above

In “A Note on the Unconscious in Psycho-Analysis” (1912), Freud defines the term “conscious” as “the conception which is present to our consciousness and of which we are aware” (2577). The conscious mind, therefore, consists of everything inside of our awareness and also includes sensations, perceptions, memories, feelings, and fantasies that are allowed in the conscious mind, whereas those that are not allowed into consciousness are repressed into and kept in the unconscious mind. Having already pointed out that London Above corresponds to the conscious mind in Freud’s psychic topography, before moving on to the more striking London Below, I shall explore what is to be found in London Above, or in the conscious mind of the city, and how it relates to London Below, especially referring to the assumed roles and environments of Richard and Jessica in London Above right before everything changes when Door, all of a sudden, enters Richard’s life.

The London Above that Gaiman depicts in the novel is the London of the 1990s. Richard Mayhew – our hero or, rather, anti- hero – is a young and ordinary Scottish businessman with a boring office job in the Securities and a pretty, yet difficult, demanding, and ambitious fiancée, Jessica. Richard, as a tiny part of a huge army of white-collar corporate workers swarming the city, and Jessica, as an avid go-getter in a cruel business world are typical, ordinary, and proper Londoners. Richard has an ordinary life and, at the very beginning of the novel, one can easily identify him as a weak, unassuming and submissive character. He is a member of the group of people who seem to be content with mere existence in their average lives in the urban space. But unlike his colleagues, like Gary, or his fiancée Jessica, Richard is

14

neither aggressive nor focused enough to get ahead, is even passed over for promotion, and is stuck in a job of boring routines (12). He is even intimidated by Jessica, and it appears that he does not even have a voice in the decisions they make regarding their future life.

Jessica, on the other hand, is an ambitious and domineering woman who is “certainly going somewhere” in life (12). She is beautiful, funny, successful, and well- mannered. She spends her free time going to art galleries and museums, and eats at the best restaurants in town. Besides, when she does not go to art galleries or to museums, Richard trails behind Jessica as she goes shopping in K nightsbridge or “on her tours of such huge and intimidating emporia as Harrods and Harvey Nichols, stores where Jessica [is] able to purchase anything from jewelry, to books, to the week’s groceries” (12). As a marketing executive for a company that is owned by one of the richest media giants, Mr. Stockton, Jessica applies strict rules to every element of her life, including her love life, and demands that Richard also play by her rules. Even love- making, for Jessica, is to be played by the rules and in a manner that befits civilised people:

And when they made love – which they did at Jessica’s apartment in fashionable Kensington, in Jessica’s brass bed with the crisp white linen sheets … - in the darkness, afterwards, she [Jessica] holds him very tightly, … and she would whisper to him how much she loved him, and he would tell her he loved her and always wanted to be with her, and they both believed it to be true. (20-21)

Brass beds, linen sheets, their words of love mixed with Gaiman’s ironic language actually uncover a familiar yet ridiculous attitude towards life, and reveal them to be nothing more than puppets whose strings are held only by conventions in a relatively modern and pretentious society that shall simply ignore any sort of discomfort. Elber-Aviram temptingly suggests, “Jessica’s worldview reduces the entire city, including Richard himself, into an enormous museum exhibition that has been dusted off and encased in glass” (4), which makes her an ideal Londoner in an ideal London. Jessica being a very good representative o f its conscious values, London Above is a typical, shiny modernist and capitalist city of luxury malls, residences, busy schedules, business meals, pseudo- intellectuals, and money hunters, where

15

people chase after success and money, unaware of their own limitations and triviality.

Jessica also has the power to turn those around her – like Richard – into ideal personalities, and if they resist or disappoint her, on whatever grounds, expel and even bury them in the underground. Therefore, it is not surprising that Jessica threatens Richard by saying “‘Richard Oliver Mayhew, … you put that girl down and come back here this minute. Or this engagement is at an end as of now. I’m warning you,’” when she sees Richard helping the wounded girl (the Lady Door) precisely because the wounded girl already poses a danger to the ideality of London that Jessica represents and has the potential to infect with non- ideality those who help or know her or even recognise her as a being (25, 26). When Richard brings the injured girl lying on the ground to Jessica’s attention, Jessica indifferently says, “‘Oh. I see. If you pay them any attention Richard, they’ll walk all over you. They all have homes, really. Once she’s slept it off, I’m sure she’ll be fine.’” (24) Here, not only does she convey a typical Londoner’s attitude towards homelessness, but also she reminds Richard of the essential rule of London Above that the poor should be unseen and ignored because they are a threat to the city’s appeara nce. Next, however, despite Jessica’s protests, Richard walks away with the wounded girl and leaves Jessica there on the sidewalk, and with that begins his physical and psychological journey of repression into the depths of London, in the magical world of London Below (26).

As a counter-city to London Above, the more interesting, alternative London, London Below exists contemporaneously yet in secret from London itself. It is a mysterious underworld kingdom of abandoned subway stations with its curious people who have “fallen through the cracks of reality” (126). It is an uncanny place of monsters and saints, murderers and warriors, fallen angels and life-sucking vampire- like seductresses, talking rats, and a hierarchy of nobility. However, all these beings that reside in London Below represent much more than what they are, taking us to the unconscious of London where the city’s haunting memories of the past lie.

In Freud’s own words, the term unconscious “designates not only latent ideas in general, but especially ideas with a certain dynamic character, ideas keeping apart

16

from consciousness in spite of their intensity and activity” (“A Note on the Unconscious” 2579). In that regard, whereas the conscious mind consists of everything inside of our awareness, the unconscious mind is a repository or a reservoir of those instincts, feelings, idea s, and memories that exist outside our conscious awareness, and yet which altogether continue to influence our behaviour and experience. The unconscious mind is that part of the mind where psychic activity, of which the person is unaware, occurs and continues to affect our deeds. In accordance with that conceptualisation, the underground space in Neverwhere, London Below, is not readily accessible or visible to the inhabitants of London Above. People from London Above do not notice the folks of London Below, and if they do, they immediately forget about the encounter. Therefore, London Below is where London Above keeps its feelings, ideas, and memories outside of its conscious awareness, especially if they are unwanted and non-ideal, as I shall examine in the following section.

1.4. The London Underground

The labyrinth itself is a place of pure madness. It was built of lost fragments of London Above: alleys and roads, and corridors and sewers that had fallen through the cracks over the millennia and entered the world of the lost and the forgotten…They walked through daylight and night, through gas-lit streets and sodium- lit streets lit with burning rushes and links. It was an ever-changing place: and each path divided and circled and doubled back on itself. (308)

This passage conveys Richard’s first impression of the labyrinth on Down Street, which is a street that literally goes down and is placed at the deepest and darkest level of London Below; however, it also provides an excellent overview of London Below, the second, invisible space of London, or the city’s unconscious. London Below is a counter-world “built of lost fragments of London Above,” (308) indicating, once again, its similarity to the unconscious mind, which is a space where not only inactive/latent ideas but also ideas that keep apart from consciousness in spite of their intensity and activity reside. So, the unconscious is not only a space where latent ideas are stored but also where thoughts and memories actively removed from consciousness dwell. In this sense, London Below also functions as a place of

17

abandonment for London Above as it keeps/represses whatever disrupts its identity here.

In Neverwhere, it is the London Underground (the Tube System) that marks the threshold between London Above and London Below. The space where the Tube is located is a permeable space at this level, which people from both London Above and Below use at the same time, though the folks of the latter still remain invisible to those living above them. This permeable territory in between, however, while allowing entry to some, does not admit others and reminds us of the censorship mechanism that ideas have to pass through to become conscious that Freud speaks of. As he maintains, “There is a force in the mind which exercises the functions of a censorship, and which excludes from consciousness and from any influence upon action all tendencies which displease it” (“Psychoanalysis” 4405; italics mine). To be more precise, the unconscious is guarded by an entity that works within the region of the unconscious, and this entity exerts a controlling and selective action. It checks those elements of unconscious experience which, by their unpleasant nature, would disturb their possessor if they were allowed to reach his consciousness, and if it permits these to pass, sees that they appear in such a guise that their nature will not be recognised. As clearly stated here, all tendencies or ideas that are displeasing are prevented from entering consciousness and are thus repressed if required. So, the territory of the tube system is precisely the point where this censorship mechanism is activated.

The tube system serves as a liminal space between London Above and London Below, and this liminal space is where the fate of things of the past is determined, and once it is determined, the subject is either allowed entry into London Above, or is doomed to be repressed into the depths of London Below, later to be erased completely from consciousness and sent down to deeper levels of the unconscious. In a certain sense, London Below is the place where London Above hides whatever disrupts its assumed identity and ideality, and it is remarkable that Richard himself is physically and literally pushed down and repressed into deeper levels of London Below after he rescues Door, obviously because he has become a threat to London Above’s supposed identity and ideality, and cannot escape the censorship mechanism exercised. However, before moving on to discuss how

18

Richard, functioning as an unwanted deed of the past, is rejected from the conscious and repressed, I would like to comment more on London Below as the city’s unconscious mind.

“The underground is a complex space, a catch-all container of sorts for everything that is no longer of use to the world above ground,” (7) suggests Schüpbach deftly in her analysis of London Below. I would like to argue, in parallel with this argument, that Gaiman’s underground in Neverwhere functions as the unconscious space which contains all sorts of obsolete edifices, unused train tracks and stations, antiquated people, horrendous beasts, killer nightmares, dirt, sewage, and debris, and even time pockets that preserve nasty historical events forgotten by the city. The city hidden below the shiny, mod ern upper world is home to everything that London Above refuses to take as its own. In other words, London Below is everything that London Above has denied and forgotten about itself, and repressed into the unconscious. However, as Freud argues, “It is by no means impossible for the product of unconscious activity to pierce into consciousness,” (“A Note on the Unconscious” 2581), which should explain Door’s first appearance in London Above as well as the situation of many others belonging to London Below who can come and go between the two spaces. So, here Door appears to have pierced into the conscious mind of the city although she is not visible to most Londoners. Freud also extends this argument in his 1915 article “The Unconscious” and says,

The unconscious comprises, on the one hand, acts which are merely latent, temporarily unconscious, but which differ in no respect from conscious ones, and, on the other hand, processes such as repressed ones, which if they were to become conscious would be bound to stand out in the crudest contrast to the rest of the conscious processes. (2996; italics mine)

Door, as a representative of the inhabitants of London Below, does “stand out in the crudest contrast” to the rest of Londoners, and that is also probably why she is overlooked by most of them. She is not like anything or anyone Richard (or a typical Londoner) has seen before either, and she also does not conform to modern rules of clothing or sanity. Richard’s description of Door’s outlook on the morning after he rescues her is as follows:

19

She looked bad: pale, beneath the grime and brown-dried blood, and small. She was dressed in a variety of clothes thrown over each other: odd clothes, dirty velvets, muddy lace, rips and holes through which other layers and styles could be seen. She looked, Richard thought, as if she’d done a midnight raid on the History of Fashion section of the Victoria and Albert Museum, and was still wearing everything she’d taken. (30)

With the traces of the past on her clothing, Door definitely belongs to London Below, the unconscious mind of the city, and she has probably been forgotten for such a long time or repressed such a long time ago that she has become even harder to notice and classify. Again, it is acknowledged here that the contents of London Below are indeed a part of the city’s psyche but are meant to be hidden in the unconscious.

The first space we are introduced to in London Below is the Floating Market. It is a giant, colourful, vibrant, and peripatetic market where people, curiously, barter for all sorts of junk and magical items, and even trash and corpses – each of these being obviously unwanted in London Above. The Floating Market is a place of chaos, disorder, and insanity, as Richard’s first impression of it suggests: “Richard stood there, alone in the throng, drinking it in. It was pure madness. O f that there was no doubt at all. It was loud, and brash, and insane, and it was, in many ways, quite wonderful. People argued, haggled, shouted, sang” (109; italics mine). It is interesting that Richard uses the words “madness” and “insane” to describe this marketplace. The Floating Market does not resemble those he has seen before in London Above. Besides, the rules of London Above do not apply here. So, it is a place where the logic of London Above does not work anymore, and that is why Richard, as a (still) proper Londoner, defines it as “insane.”

Another curious phenomenon concerning the Floating Market is that the first thing Richard notices upon entering the market is that his watch stops working:

Richard looked down at his watch, and was not surprised to notice that the digital face was now completely blank. Perhaps the batteries had died, or, he thought, more likely, time in London Below had only a passing acquaintance

20

with the kind of time he was used to. He did not care. He unstrapped the watch and dropped it into the nearest bin. (108)

That his watch stops working the minute he enters a space which belongs to London Below or the city’s unconscious calls to mind Freud’s account of the id, which is closely related to the unconscious mind, when he says, “There is nothing in the id that corresponds to the idea of time; there is no recognition of the passage of time, and … no alteration in mental processes is produced by the passage of time” (“The Dissection of the Psychical Personality” 4682). This curious and insane phenomenon once again helps us understand that Richard is now in the city’s unconscious mind where everything is distorted and even inverted in relation to London Above.

Also distorting and inverting the cityscape of the modern, shiny, hygienic, and ideal London Above, Gaiman builds London Below as largely a 19th-century, Victorian version of the city. However, although it has quite a Victorian outlook, there is also a timelessness to London Below as if it has existed long before everything. The wall paintings that Richard looks at, for example, go further back in time to prehistoric times:

They were walking through a maze of caves, deep tunnels hacked from the limestone that to Richard felt almost prehistoric…[H]e admired the paintings on the cave walls. Russets and ochres and siennas outlined charging boars and fleeing gazelles, woolly mastodons, and giant sloths. (262)

With its prehistoric colours and animals, the paintings on the walls belong to much earlier times in the history of London. Things long forgotten show up in London Below as a reminder of the city’s past. In addition to this amazing labyrinth belonging to prehistoric times, we also learn that there are still “some Roman soldiers camped out by the Kilburn River” (89), and that the bunkbeds and cardboard boxes belonging to the soldiers of the Second World War are still kept in an underground tunnel (93).

Another telling moment in the novel is a scene in which the Lady Door’s entourage (comprised of Richard, the Marquis de Carabas, and the legendary Hunter) encounter a yellow-green fog that is getting thicker in London Below. When they see the fog, Door says “Pea-soupers” (229) which, also known as a “killer fog,” are a

21

coloured kind of fog, caused by extreme air pollution, containing poisonous gases, and there is a historical reference to the “Great Smog of 1952” or “Big Smoke,” which actually did take place in London in 1952, killing a vast number of people:

‘Pea-soupers,’ said Door. ‘London Particulars. Thick yellow river-fogs, mixed with coal-smoke and whatever rubbish was going into the air for the last five centuries. Hasn’t been one in the Upworld for, oh, forty years now. We get the ghosts of them down here. Mm. Not ghosts. More like echoes. (229; italics mine)

A fog containing poisonous gases which kills a vast number of people is definitely not a memory that a city or a nation would be proud of. On the contrary, such an incident is disgraceful and of a type one would like to forget and not remember again which explains why it has been repressed and sent down to London Below. As Vanderbeke maintains, “In London Below, the past is still alive, but it is not quite the past that can be learned from history books” (157). London Below preserves the unwanted truths, people, and history that do not fit into the desired image of London Above anymore. In that regard, London Below becomes a mirror that reflects a London jumbled together from all eras, and these elements altogether, once again, remind us that London Below functions as the repository for everything that is unwanted, improper, and non- ideal in London Above. It is the unco nscious mind of the city of London, where the city’s unwanted memories are stored, and the level of unconsciousness and insanity increases as we go deeper. Richard’s journey into the underground is nothing but the process of repression itself which he will either survive or surrender to.

1.5. Repression

As mentioned earlier, Richard’s acquaintance with London Below begins when he, despite Jessica’s protests, cannot overlook the wounded girl named Door lying on the pavement, and takes her home to help her. Jessica, the ideal citizen of the ideal city of London Above, threatens Richard with breaking off their engagement. However, her threat is not simply a threat to withdraw from Richard. Indeed, it is a warning by the retributive mechanism of London’s psyche that it will break Richard’s connection with reality (or consciousness) if he finishes what he has

22

already started doing by paying attention to a condemned and overlooked phenomenon, such as a homeless person, or a non-person, as Richard will later call himself (62). As Richard walks home with the poor homeless girl partly covered in blood in his arms, the blood soaking into his best shirt, the narrator tells us:

Somewhere in the sensible part of his head, someone – a normal, sensible Richard Mayhew – was telling him how ridiculous he was being: that he should just have called the police, or an ambulance; that it was dangerous to lift an injured person; that he had really, seriously, properly upset Jessica; that he was going to have to sleep on the sofa tonight; that he was spoiling his only really good suit; that the girl smelled quite dreadful… (26, 27; italics mine)

There is a voice in Richard’s head that immediately begins talking and tells him that what he has done is, in a way, not correct or sensible. So, here are a set of questions I shall try to answer: Who is this “someone - a normal, sensible Richard Mayhew” talking to Richard? Also, what is implied through “a normal, sensible part of his mind” and why does this sensible part of his mind tell him that such an innocent and even virtuous deed as helping a wounded person is not correct but rather ridiculous?

Apparently, the voice that Richard hears inside his head and calls “a normal, sensible Richard Mayhew” is the voice of his ideal self or what Freud calls, in his 1914 essay “O n Narcissism,” the “ego ideal,” which he will ultimately describe as the “super-ego.” At this point, before going on with my discussion of the foregoing quote and already having put considerable e mphasis on the concepts of the “ideal” and “ideality,” I would like to expand on the concept of the ideal self or ego ideal. In his article “On Narcissism,” Freud speaks of “a special psychical agency … which … constantly watches the actual ego and measures it by [the] ideal” (2948) it has set. This special agency is not only a censoring (2949) one that excludes and represses unwanted deeds, but it also critically observes (2950) and, if necessary, punishes the ego. This institution within the psyche is not something alien to us at all. Indeed, this power that constantly watches, discovers and criticises all our intentions “exists in every one of us in normal life,” (2949) and it is precisely what we call our conscience (2949) as Freud asserts. The super-ego, or the ego ideal, in Freudian terms, strives to live up to the established rules, morals and ethical restraints imposed on us by the

23

society and culture we live in. In a certain sense, the ego ideal is an imaginary picture of how we should be, and therefore represents learned or imposed rights and wrongs about how things should be. As a matter of fact, the ego ideal is an imagined and abstract picture of how one should be, and it sets the rules of how we should live, how we should treat other people and how we should behave properly as members of society. Whereas the id stands for the unconscious, passionate, impulsive, irrational, and almost bestial part of the human mind driven essentially by instincts and impulses and requiring immediate satisfaction, the super-ego is the guardian of the

ideal self. The super-ego thus functions as a mechanism, an inner critic, that judges

us, criticises us, and showers us with feelings of guilt, shame, and worthlessness when the experience of the subject does not conform to the rules it has set, and it thereby seeks to maintain the ideality. Howeve r, the process through which this personal internal judge is formed is of greater significance at this point particularly because Richard’s saving a wounded girl is not to be judged as wrong or ridiculous or irrational in terms of morality but rather as kind, humane and worthy of praise. So, this delusive judgment that Richard’s conscience or ideal self makes indicates that there is a negative and vicious element in the formation of the super-ego here, both in Richard’s and, as its reflection, in the city of London’s psyche.

“The institution of conscience was at bottom an embodiment, first of parental criticism, and subsequently of that of society…” (2949) says Freud in “On Narcissism.” So, the ideal ego is formed mostly during upbringing. The ideals that contribute to its formation do not solely include the morals and values learned from parents. The ideas about what is right or wrong acquired from the society and culture we live in are a major constituent of super-ego formation, and whether these rights or wrongs learned from the society are false does not matter at all because, as Freud remarks in the very first sentence of Civilisation and its Discontents, “[it] is impossible to escape the impression that people commonly use false standards of measurement – that they see power, success and wealth for themselves and admire them in others, and that they underestimate what is of true value in life” (4464). So, as the ego ideal aims to guide behaviour in accordance with the norms and values embraced by the family/society one lives in, we, once again, need to go back to the society and culture of where Richard lives, namely London Above, or the contents of

24

the city’s consciousness to understand what lies beneath his ideal self’s producing the feeling of guilt.

As noted earlier, Jessica is a very good representative of the values adopted in London Above and, indeed, she becomes the incriminating voice of the city of London’s super-ego when she threatens Richard with breaking off the engagement, saying “‘Richard Oliver Mayhew … you put that girl down and come back here this minute. Or this engagement is at an end as of now. I’m warning you’” (25, 26). Overall, obviously, Jessica’s reaction is not only to Richard’s leaving her in the middle of the street on the eve of an important meeting with her boss. It is also a reaction to Richard’s paying attention to a homeless person in need and whom, to Richard’s astonishment, Jessica literally cannot see for a while: “He could not believe she was simply ignoring the figure at their feet” (24). In the course of events, this – Richard’s seeing the girl despite Jessica’s refusal to notice her – becomes almost a sin that he has to pay for. It is perplexing that the representative of the ideal self of London perceives this little, wounded figure lying crawled on the pavement as a threat simply because Door looks like a homeless person and a threat to the city’s

ideal outlook. Homelessness and the homeless are an important social “threat” to

London’s ideal self, which can only be maintained by avoiding, denying, or excluding these completely, thus becoming an idealised London. Therefore, it is only natural that Richard’s ego-ideal, formed around these values, criticises him and punishes him with guilt. The feeling of guilt thus becomes a product of cultural conditioning although the deed of helping a needy person is worthy of commendation in itself. So, in a London that has idealised itself through excluding the phenomena that pose a threat to its ideal identity, it should not be surprising that an average Londoner, Richard Mayhew, has also developed an ideal ego that has been formed around values that deem avoidance of potential threats a virtue, which explains why the sensible self of Richard (his super-ego) considers his behaviour ‘ridiculous’.

Going back to the story, Richard, regardless of Jessica’s protests, does not stop, and, he walks away with the homeless girl in his arms, leaving Jessica behind with tears in her eyes, thus bowing to the inevitable consequences of his socially-unacceptable and inappropriate deed and accepting that he has to pay the price. In