Full Terms & Conditions of access and use can be found at

http://www.tandfonline.com/action/journalInformation?journalCode=raec20

Download by: [Bilkent University] Date: 25 October 2017, At: 04:04

Applied Economics

ISSN: 0003-6846 (Print) 1466-4283 (Online) Journal homepage: http://www.tandfonline.com/loi/raec20

High inflation and returns on residential real

estate: evidence from Turkey

Zeynep Onder

To cite this article: Zeynep Onder (2000) High inflation and returns on residential real estate: evidence from Turkey, Applied Economics, 32:7, 917-931, DOI: 10.1080/000368400322255 To link to this article: http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/000368400322255

Published online: 04 Oct 2010.

Submit your article to this journal

Article views: 106

View related articles

High in¯ ation and returns on residential

real estate: evidence from Turkey*

ZEY N EP OÈNDER

Bilkent University, Faculty of Business Administration, Bilkent, Ankara 06533, Turkey E-mail: zonder@bilkent.edu.tr

This study examines the hedging behaviour of real estate investment in a high in¯ a-tionary environment. The hypothesis that the real estate investment hedges both expected and unexpected in¯ ation is tested. The returns of investment on residential apartments in several neighbourhoods in the capital of Turkey are used in the analy-sis. Expected in¯ ation is measured by three proxies. It is found that in a high in¯ a-tionary environment, real estate investment does not provide hedge against in¯ ation. A reverse causality between returns on real estate and changes in expected in¯ ation is not observed. However, a relationship between real returns and changes in in¯ a-tionary expectations seem to be di erent in relatively low and relatively high income neighbourhoods.

I. INTR OD UCTION

Several studies have examined whether assets provide e ec-tive hedges against in¯ ation. The results of these studies have suggested that assets are di erent in terms of their hedging behaviour against expected and unexpected in¯ a-tion. Common stocks act as a perverse hedge against both expected and unexpected in¯ ation in most of the developed markets examined (for example, Bodie, 1976; Nelson, 1976; Fama and Schwert, 1977; Firth, 1979; Fama and Gibbons, 1982; Gultekin, 1983). Although the returns on common stocks are negatively correlated with expected and unex-pected in¯ ation, it is found that real estate investment is a good hedge against expected and unexpected in¯ ation. For example, Gyourko and Linneman (1988) ® nd a posi-tive association between appreciation in residential and nonresidential real estate and in¯ ation. Similarly, using the percentage change in the home purchase price compon-ent of the CPI as the return on privately held residcompon-ential real estate, Fama and Schwert (1977) conclude that real estate can hedge expected and unexpected in¯ ation.

Results are di erent for the hedging behaviour of real estate investments depending on the proxy used for meas-uring expected in¯ ation. For example, forecasting in¯ ation with ARMA model, Gyourko and Linneman (1988) ® nd a strong negative correlation between return on real estate investment trusts (REITs) and unexpected in¯ ation. Similarly, Gartzla (1994) ® nds that estimates of unex-pected in¯ ation using the adoptive expectations model and the rational expectations model are positively corre-lated with excess returns to housing. Park et al. (1990) use two proxy measures for expected in¯ ation. They ® nd that REITs behave as perverse in¯ ation hedges when they meas-ure anticipated in¯ ation with the return on Treasury bills. On the other hand, using Livingston’s in¯ ation expecta-tions, REITs seem to act as partial hedges against expected in¯ ation but not for unanticipated in¯ ation. Expanding the analysis to the international property trusts, Liu et al. (1997) ® nd that the degree of perverse hedging behaviour of trusts is di erent among countries in their sample.

The hedging behaviour of real estate returns can be explained with the following relationship. An increase in in¯ ation rate reduces the e ective cost of home ownership

Applied Economics ISSN 0003± 6846 print/ISSN 1466± 4283 online#2000 Taylor & Francis Ltd

http://www.tandf.co.uk/journals

Applied Economics, 2000, 32, 917± 931

917 * An earlier version of this paper was presented at the 1998 Joint International Conference of the American Real Estate and Urban Economics Association and the European Real Estate Society meeting in Maastricht, the Netherlands.

because of the decline in the relative cost of mortgage, hence, the tax subsidy to owner occupation is increased. The decline in the relative cost of home ownership will increase the demand for owner occupation, as a result, house prices will increase. Several researchers, for example, Summers (1981), Poterba (1984), Goodwin (1986) and Manchester (1987), have explained the boom in house prices in the US during the 1970s this way.

These results suggest that housing and mortgage markets and taxation might explain the expected and unexpected in¯ ation hedging behaviour of real estate returns. Almost all of the countries examined has not experienced high in¯ ation. There is a question of whether hedging behaviour of real estate can be extended to a high or hyper-in¯ ationary economy. The Turkish market provides a good oppor-tunity to test the hedging behaviour of real estate under high in¯ ation. The in¯ ation rate in Turkey is very high relative to all other countries examined in the literature. The average annual in¯ ation rate has been more than 50% since 1986.

This is the ® rst study that examines the hedging behav-iour of real estate investment in a high in¯ ationary envir-onment. The real estate and mortgage markets in Turkey have di erent characteristics compared to the developed markets that are examined extensively. In addition to high in¯ ationary economy, there is not a good mortgage market in Turkey. The downpayment requirement for pur-chasing a house is very high, reaching to 70% of the house value in some cases. Additionally, the longest term on home mortgage loans is ® ve years. Hence, we cannot argue that the existence of in¯ ation reduces the cost of home ownership. Tax regulations are also di erent. For example, mortgage payments are not tax deductible. In case of the sale of housing units, both buyer and seller have to pay equal amount of tax.

This study examines the relationship between in¯ ation and returns on residential real estate investment in the capital of Turkey, Ankara. The asking prices of apartments on sale in several neighbourhood s in Ankara are collected for the analysis. The quarterly in¯ ation rate and returns on real estate are calculated for the period between the ® rst quarter of 1977 and the last quarter of 1996. Unlike the studies that examined developed markets, it is hypoth-esized that returns on real estate do not signi® cantly hedge against expected and unexpected in¯ ation. In addition, Fisherian Direct Causality and Reverse Causality hypoth-eses are tested using returns on residential real estate investment in Ankara. For comparison, the models are also estimated for the returns on stocks traded in the Istanbul Stock Exchange (ISE). The results do not indicate that real estate investment in Ankara is a good hedging instrument against expected and unexpected in¯ ation.

The paper is organized as follows. The next section gives information about the real estate and mortgage markets in Turkey. The methodology and data used in the analysis are

presented in the third section. The fourth section presents the results of the analysis. The ® fth section concludes the paper.

II. BA CKG R OUN D: IN FLA TION , R EA L ESTA TE A ND M OR TGA GE MA R K ETS IN TUR K EY

In this section, some information about in¯ ation, housing supply and mortgage market in Ankara are given in order to understand the relationship between in¯ ation and returns on real estate in Turkey.

In¯ ation

Turkey has experienced high in¯ ation since 1977. A sudden increase in oil prices in the world in 1977 had an impact not only on the developed economies but also developing economies like Turkey. Since Turkey is an oil importing country, the increase in oil prices increased the demand for foreign currencies, and the ® nancing of large current account de® cits with external borrowing led to foreign exchange shortage. A series of devaluation of Turkish Lira against foreign currencies and the adjustment process with current account de® cit resulted in a sharp increase in in¯ ation for the period between 1977 and 1980.

The stabilization and liberalization policies in January 1980 settled down the economy. According to these deci-sions, ® rst, interest rates were allowed to ¯ oat. Then, they were increased above the in¯ ation rate. Even though the real interest rates were negative until 1980, after these deci-sions they became positive. An increase in interest rates attracted many people to invest in money market instru-ments and resulted in the decline in the demand for housing, which is considered as an alternative way of investment. Individuals started to sell their houses and invest in the money market instruments. It is found that the demand for housing decreased when the real interest rate on demand deposits was positive (Korum, 1982) .

Large amount of domestic borrowing at high levels of interest rate led in¯ ation rate to increase to 40% in 1984. Then, it reached 50% during the second half of the 1980s as the domestic debt ® nance had been the major source of ® nancing (OÈzmen, 1998). Political instability derailed the success of some disin¯ ation programmes and in¯ ation rate continued to increase. In 1994, another jump in in¯ ation occurred because of foreign exchange crises and Turkey had experienced three digit in¯ ation rates. Figure 1 shows the annual in¯ ation rate over the period analysed in this study.

Mortgage market in T urkey

The Turkish mortgage market is not well developed. Private lenders, mainly banks, started to give mortgages only in the late 1980s as part of their consumer loan pro-grammes designed not speci® cally for home buying. They were short-term and fully amortizing loans with the maxi-mum loan term between 1 to 5 years. The interest rate on loans has adjusted periodically. Several banks have di er-ent requiremer-ents for the mortgage origination. The maxi-mum loan-to-value ratio has been changing between 50% and 70%. Some banks also have limits on the loan amount that an individual can borrow.

In addition to private lenders, the loans from a govern-mental organization, Housing Development Administra-tion, are available for individual home buyers. They are also originated by the private lenders that charge commis-sion and servicing fee for loan originations. These loans have more favourable terms than loans provided directly by private lenders. Even though these loans had terms of up to 15 years, fully amortized with ® xed interest rate before 1989, interest rates have started to be adjusted

using CPI and terms have reduced after 1989. These loans are also available to home builders, especially to cooperatives that are responsible for the development of many housing projects in Turkey.

The private lenders o er construction loans to the home builders as well. These loans are used by yapsatci, a small

scale home builder.1 Most of the apartments analysed in

this study were constructed by this type of builders. Lenders have di erent requirements for them. For ex-ample, downpayment requirement has been changing

between 20% and 50%.2

Real estate market in Ankara

Ankara is one of the most developing cities in Turkey. The population has increased with the migration of households from rural areas and other cities to Ankara. According to 1980 and 1990 Censuses, the population in one central county (or township) in Ankara increased by 52%. The increase in population should increase the demand for housing. However, since the mortgage

In¯ ation and returns on real estate

919

0 20 40 60 80 100 120 140 77 -4 78 -3 79 -2 80 -1 80 -4 81 -3 82 -2 83 -1 83 -4 84 -3 85 -2 86 -1 86 -4 87 -3 88 -2 89 -1 89 -4 90 -3 91 -2 92 -1 92 -4 93 -3 94 -2 95 -1 95 -4 96 -3 Quarters In fla tio n R at e (% ) inflation

Fig. 1. Annual in¯ ation rate for the period 1977± 1996

1Y apsatci is in English translation, build and sell.

2These information are taken from the interviews with the major banks providing mortgages to individuals and home builders, made by the Fannie Mae (1992).

market is not well developed and buying a house requires large amount of saving, the demand for owner-occupied housing has not increased as much as the increase in popu-lation. The requirements of lenders for permanent income and a su cient amount of money for downpayment led to the development of slum houses at the outskirts of the city.

In Ankara, there are several neighbourhoods. Some neighbourhoods are located in the central part of the city and some are located at the outskirts. As the population in

Ankara increased, the densities increased.3Since the land is

limited in the central part, the increase in housing supply occurs with the rebuilding of higher story buildings or building new apartments on the limited land.

In the central part of the city, the densities increased by allowing higher ¯ oor buildings in already built-up areas. In these areas, most of the development of housing units is performed by yapsatci. They construct on single spots. They can either buy the land and construct apartments or they agree with the land owner to give some apartments in return for land.

An increase in demand for housing led the government to increase the supply of land for housing. This is achieved with two sources (Baharoglu et al., 1997). The ® rst one is the development of the new urban land at the outskirts of the city. The second one is the legalization of the unauthor-ized land where slum houses are located. This resulted in the increase in housing supply in neighbourhoods located not only at the central area but also in areas close to the outskirts of the city.

The increase in the housing supply has been high on the outskirts of the city because the new land area has been allowed for construction. This resulted in the construction of new suburban neighbourhoods that are 10± 20 kilo-metres from the central city. The construction on the out-skirts of the city is done usually by cooperatives and the state organization, called Housing Development Adminis-tration and the Real Estate Bank which provide some ® nancing bene® ts to the cooperatives and individuals buying apartments in these buildings. So, ® nancing alter-natives are di erent for these groups. In this study, the selected neighbourhoods are located in the central part of the city.

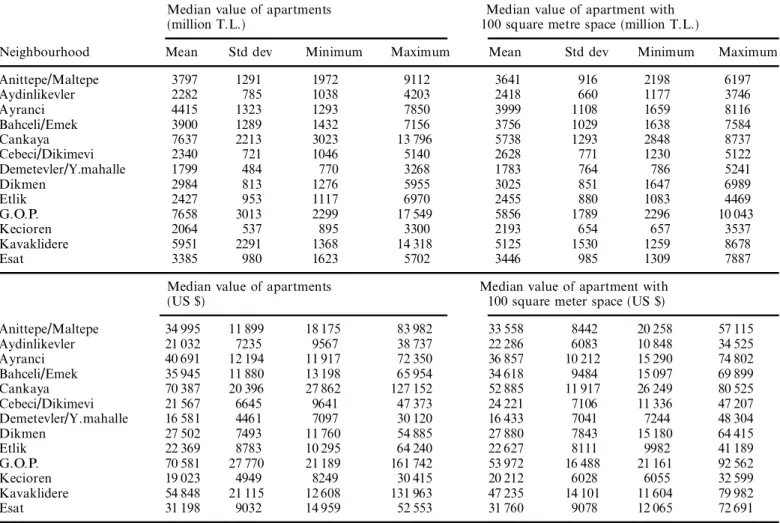

The apartment prices in several neighbourhoods in Ankara are shown in Table 1. The variation in values among neighbourhoods is not only related with the cost of construction because of di erences in land prices. The availability of shopping centres, the existence of coopera-tive buildings, hotels, embassies and the quality of housing construction also in¯ uence variation in prices. The

vari-ation in house values in Ankara is also documented by Turel (1981).

III . METHOD OLOGY A ND D A TA Models

Three models are used to examine the relationship between in¯ ation and returns on residential real estate in Ankara. The ® rst one is Fama± Schwert (1977) model which is based on the Fisher’s well-known argument that the nominal interest rate can be expressed as the sum of the expected in¯ ation and the expected real rate of return. Applying this argument to all assets, the expected nominal return on assets can be expressed as the sum of the expected in¯ ation and the expected real return. In analysing the hedging behaviour of assets, the model developed by Fama and Schwert (1977) is extensively used since it is possible to identify the relationship between return on assets and both expected and unanticipated components of in¯ ation. Their model is expressed as follows:

~

Ri;tˆ¬ ‡ E…~It† ‡ ® ‰ ~It¡ E… ~It†Š ‡ "it

where ~Ri;t represents the return on the asset i at time t. ~It

and E… ~It† correspond to the actual and expected in¯ ation

rates, respectively. If an asset provides a complete hedge against expected and unexpected in¯ ation, both and ® should be 1.

According to Fisher, the expected real return is deter-mined solely by real factors, such as productivity of capital, investors’ time preferences, tastes for risk. Hence, the expected real return and the expected in¯ ation rate are

unrelated. This hypothesis, which is called Fisherian

Direct Causality hypothesis, is tested using Solnik (1983) model:

~

ri;t ˆ ¬ ‡ 1E… ~It† ‡ 2‰E… ~It‡1† ¡ E… ~It†Š ‡ eit

where ~ri;t is the ex post real rate of return on asset

(~ri;tˆ ~Ri;t¡ ~It). Under the null hypothesis, both coe

-cients are expected to be zero since real returns are inde-pendent of any expected in¯ ation level or expected changes in in¯ ation.

As a third model, Geske and Roll’s (1983) hypothesis is tested. Unlike Fama and Schwert (1977) and Solnik (1983), they conjecture that ¯ uctuations in return on assets cause changes in in¯ ationary expectations. Their reverse causality model is tested using the following model:

E… ~It‡1† ¡ E… ~It† ˆ ¬ ‡ ¯1E…~It† ‡ ¯2R~i;t‡ et

3For example, according to the 1980 Census, there were 2023, 1576 and 663 people living in one square kilometre area in Cankaya, Kecioren and Yeni Mahalle counties in Ankara, respectively. These numbers increased to 2326, 2684 and 834 according to the 1990 Census.

Under the null hypothesis, both coe cients are expected to

be less than zero. The coe cient on E… ~It† represents the

speed of adjustment for expected in¯ ation. The coe cient

on ~Ri;tshows the impact of the asset returns on changes in

the expected change in in¯ ation.

All these models are tested for returns on residential real estate in several neighbourhoods in Ankara using three di erent in¯ ation expectations. Ordinary least squares pro-cedure is used in the estimations. When autocorrelation or heteroscedasticity is detected, standard errors are esti-mated using Newly± West correction procedure. In order to make comparison, all the models are also estimated for the return on the ISE stock index.

Expected in¯ ation

Three proxies are used to measure expected in¯ ation. As a ® rst proxy, using quarterly in¯ ation rates over the analysis period, in¯ ation rate is forecasted with the ARMA model.

The ARMA model is selected based on Akaike and Schwarz Information criteria. The model is presented in Table 2. The other expected in¯ ation measures are applied only for the period between the ® rst quarter of 1986 and the last quarter of 1996 because the T-bill market has been operating since 1986. The lagged returns on 3-month T-bills are taken as a second measure of the expected in¯ ation rate. The third proxy is the one o ered by Fama and Gibbons (1982). The expected in¯ ation rate is estimated using the yield on 3-month T-bills. Most of the previous research used these measures as an approximation for the expected in¯ ation rate.

The e ectiveness of these three proxies is measured using a regression model and presented in Table 2. The expected

in¯ ation rate with ARMA model has the highest R2. The

estimated constant is not signi® cantly di erent from zero, except for the second proxy, the lagged return on 3-month T-bill.

Table 1. Descriptive statistics of the median apartment values in several neighbourhoods in Ankara based on December 1996 prices (in

million T .L . and US$)

Median value of apartments Median value of apartment with (million T.L.) 100 square metre space (million T.L.)

Neighbourhood Mean Std dev Minimum Maximum Mean Std dev Minimum Maximum

Anittepe/Maltepe 3797 1291 1972 9112 3641 916 2198 6197 Aydinlikevler 2282 785 1038 4203 2418 660 1177 3746 Ayranci 4415 1323 1293 7850 3999 1108 1659 8116 Bahceli/Emek 3900 1289 1432 7156 3756 1029 1638 7584 Cankaya 7637 2213 3023 13 796 5738 1293 2848 8737 Cebeci/Dikimevi 2340 721 1046 5140 2628 771 1230 5122 Demetevler/Y.mahalle 1799 484 770 3268 1783 764 786 5241 Dikmen 2984 813 1276 5955 3025 851 1647 6989 Etlik 2427 953 1117 6970 2455 880 1083 4469 G.O.P. 7658 3013 2299 17 549 5856 1789 2296 10 043 Kecioren 2064 537 895 3300 2193 654 657 3537 Kavaklidere 5951 2291 1368 14 318 5125 1530 1259 8678 Esat 3385 980 1623 5702 3446 985 1309 7887

Median value of apartments Median value of apartment with

(US $) 100 square meter space (US $)

Anittepe/Maltepe 34 995 11 899 18 175 83 982 33 558 8442 20 258 57 115 Aydinlikevler 21 032 7235 9567 38 737 22 286 6083 10 848 34 525 Ayranci 40 691 12 194 11 917 72 350 36 857 10 212 15 290 74 802 Bahceli/Emek 35 945 11 880 13 198 65 954 34 618 9484 15 097 69 899 Cankaya 70 387 20 396 27 862 127 152 52 885 11 917 26 249 80 525 Cebeci/Dikimevi 21 567 6645 9641 47 373 24 221 7106 11 336 47 207 Demetevler/Y.mahalle 16 581 4461 7097 30 120 16 433 7041 7244 48 304 Dikmen 27 502 7493 11 760 54 885 27 880 7843 15 180 64 415 Etlik 22 369 8783 10 295 64 240 22 627 8111 9982 41 189 G.O.P. 70 581 27 770 21 189 161 742 53 972 16 488 21 161 92 562 Kecioren 19 023 4949 8249 30 415 20 212 6028 6055 32 599 Kavaklidere 54 848 21 115 12 608 131 963 47 235 14 101 11 604 79 982 Esat 31 198 9032 14 959 52 553 31 760 9078 12 065 72 691

4The State Institute of Statistics has calculated the CPI for Ankara since 1987. The estimations are also obtained by using this price index for the period after 1987. The results were similar. They are not reported here but available from the author upon request.

In the analysis, CPI reported by the State Institute of

Statistics is used in order to estimate the rate of in¯ ation.4

The natural logarithm of the ratio of the CPI values at time t and t ¡ 1 is calculated.

The quarterly analysis is employed. The time period cov-ered in the study is between the ® rst quarter of 1977 and the last quarter of 1996. Since both stock market and bond market have been operated since 1986, some analyses are done for the period after 1985 which corresponded to the high in¯ ationary period.

Measures of return on real estate

A proxy that is widely used in the literature for measuring return on real estate is the appreciation rate in the house purchase price component of the CPI (for example, Fama and Schwert, 1977). Unfortunately, only rents, the prices of

utilities and the maintenance costs are considered as hous-ing expenses in the Turkish CPI calculation. Hence, it is not possible to use this component as a return on real estate investment. If this component of the CPI is used, income component but not the appreciation in the real estate values will be included in the real estate returns.

In the literature, the return on REITs is widely used as another alternative. They behave like hybrid assets between stocks and real estate. There are only four REITs traded in the Istanbul Stock Exchange (ISE), all of them were issued in 1997. Hence, there is not su cient number of observa-tions regarding returns on REITs to compare with expected in¯ ation. In addition, the portfolio of these REITs consists of mainly nonresidential real estate, such as land and o ce buildings.

All these restrictions resulted in the collection of new data from daily newspapers. Daily newspapers have sec-tions where individuals or real estate agencies can list houses or apartments for sale. They provide information about real estate, such as price, location, size, number of bedrooms, heating facilities, number of baths, age of hous-ing unit, etc. The prices and some reported characteristics of the apartments listed in the daily newspapers at the end of each quarter are collected for the analysis. Unfortunately, these asking prices are not claimed to be actual transaction prices of apartments but since the appre-ciation rate is calculated, this bias will be consistent over all real estate values.

There is a dispersion in house values in Ankara. Therefore, the apartment appreciation rates in di erent neighbourhoods are analysed. Returns are calculated from two bases. The ® rst one is the change in the median apartment value for sale in each neighbourhood at the end of each quarter. The second one is based on the change in median value of apartments with 100 square metre space. Log returns are used in the calculations.

The data on apartments for sale at the end of each quar-ter are collected for the thirteen neighbourhoods in Ankara: Aydinlikevler, Anittepe/Maltepe, Ayranci, Bahceli/Emek, Cankaya, Cebeci/Dikimevi, Demetevler/Yeni Mahalle, Dikmen. Etlik, Esat, G.O.P., Kavaklidere and Kecioren. There are di erences in the characteristics of households residing in these neighbourhoods. Some neighbourhoods are preferred by relatively high-income households and some of them are preferred by relatively low-income households. In addition, some of them are located at the central part of the city and some of them are close to the outskirts of the city. Table 1 shows some descriptive statis-tics of the median apartment values and the median value

Table 2. Regression estimates for the evaluation of the expected

in¯ ation rates: Model: Itˆ ¬ ‡ E…Iit† ‡ et

Parameter

estimate t-statistic R-square

E…I1t† ¬ 70.007 70.308 0.302 1.052 5.618 E…I2t† ¬ 0.076 3.185 0.132 0.354 2.463 E…I3t† ¬ 0.000 0.000 0.156 1.000 2.757 Note.

Expected in¯ ation estimations:

E…I1t† is estimated using ARMA modelling. AR(1), MA(4), and SAR(4) are used in forecasting in¯ ation rates. This model pro-vided the highest Akaike and Schwarz information criteria. Estimation results:

…E…I1t† ˆ …0:925† ‡ …0:308† ¢ …It¡1† ‡ …0:996† ¢ …It¡4†

‡ …¡0:960† ¢ …ut¡4††

R-squared 0.301

Akaike info criterion 75.997 Schwarz criterion 75.874

F-statistic 10.184

E…I2t† is the lagged return on 3-month T-bill. (E…I2t† ˆ T ¡

Billt¡1†.

E…I3t† is estimated using the regression of in¯ ation with the return on 3-month T-bill.

…E…I3t† ˆ …0:076† ‡ …0:354† ¢ …T ¡ Billt¡1††

(3.185) (4.312)

t-statistics are in parentheses.

5Instead of using 13 neighbourhoods, another possibility is creating a housing index in Ankara using hedonic estimation. There are only limited numbers of housing units with detailed housing characteristics. The sample consists of 7057 units with value and location. The number of observations declines to 2785 with size. However, if we want to include any other characteristics, there are only 545 units left in the sample.

of apartment with 100 square metre area based on 1996 prices.

In addition to the returns on real estates located in 13

di erent neighbourhoods in Ankara,5the models are also

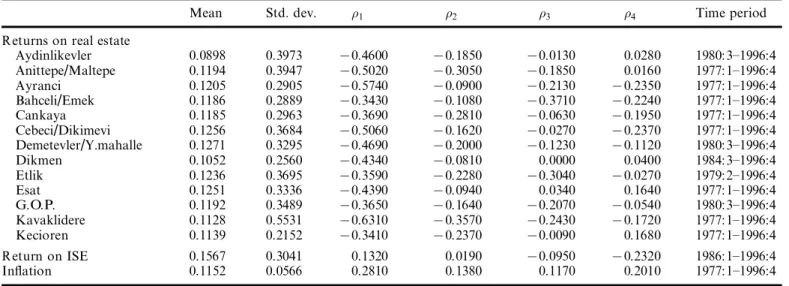

estimated for the return on the ISE index. Table 3 presents some descriptive statistics of the quarterly returns and in¯ ation for the period analysed.

IV. R ESULTS

Hedging behaviour of residential real estate

Table 4 presents the results of the test of in¯ ation hedging behaviour of the return on residential real estate in thirteen neighbourhoods in the city of Ankara and the return on the ISE stock index using the Fama± Schwert model with three di erent in¯ ation expectations. In order to eliminate any changes in the size of the apartments over the time period covered between 1977 and 1996, the returns on residential real estate are calculated using the changes in the median value of apartments converted into 100 square metre space. Since the last two measures of the expected in¯ ation are available after 1985, the last two tests examine the Fama±

Schwert model only for that period.6

The results suggest that residential real estate investment in several neighbourhood s in Ankara does not behave as hedges for expected and unexpected in¯ ation. Most of the coe cients on expected and unexpected in¯ ation are found to be not signi® cantly di erent from zero. The coe cients and their signi® cance are di erent depending on the proxy

used to measure expected in¯ ation. In only two neighbour-hoods, Ayranci and Kavaklidere, the coe cient on the expected in¯ ation is found to be signi® cantly positive when the third proxy is used to measure expected in¯ ation. Relatively moderate- and high-income households are con-sidered to be living in both of these neighbourhoods. Most of the coe cients on the unexpected in¯ ation are found to be negative but signi® cant in only ® ve neighbourhoods. In Demetevler, Etlik and Aydinlikevler where relatively low-and moderate-income households live, the coe cient is sig-ni® cantly less than zero. We cannot make any generaliza-tion regarding income level, because this coe cient is found to be negative and signi® cant in G.O.P. where the average median apartment value is highest. Unlike the pre-vious studies, we could not observe a hedging characteristic of residential real estates under high in¯ ation in Ankara. The coe cient on unexpected in¯ ation is found to be sig-ni® cant and positive in only Dikmen which has been open for urbanization within the last 15 years and still in this

process of urban development.7

The hypothesis of the equality of the coe cients on expected in¯ ation in all neighbourhoods and the equality of coe cients on unexpected in¯ ation is tested with F-test. The results suggest that these coe cients are not equal in all neighbourhoods using the ® rst and third proxies for expected in¯ ation. However, this hypothesis failed to be rejected when the lagged return on T-bill is used as a meas-ure of expected in¯ ation.

The hedging behaviour of the ISE stocks seems to be similar to the hedging behaviour of the stocks in other countries. Unlike the US market, ISE stocks do not act

In¯ ation and returns on real estate

923

Table 3. Means, standard deviations and autocorrelations of quarterly nominal rates of return

Mean Std. dev. »1 »2 »3 »4 Time period

Returns on real estate

Aydinlikevler 0.0898 0.3973 70.4600 70.1850 70.0130 0.0280 1980:3± 1996:4 Anittepe/Maltepe 0.1194 0.3947 70.5020 70.3050 70.1850 0.0160 1977:1± 1996:4 Ayranci 0.1205 0.2905 70.5740 70.0900 70.2130 70.2350 1977:1± 1996:4 Bahceli/Emek 0.1186 0.2889 70.3430 70.1080 70.3710 70.2240 1977:1± 1996:4 Cankaya 0.1185 0.2963 70.3690 70.2810 70.0630 70.1950 1977:1± 1996:4 Cebeci/Dikimevi 0.1256 0.3684 70.5060 70.1620 70.0270 70.2370 1977:1± 1996:4 Demetevler/Y.mahalle 0.1271 0.3295 70.4690 70.2000 70.1230 70.1120 1980:3± 1996:4 Dikmen 0.1052 0.2560 70.4340 70.0810 0.0000 0.0400 1984:3± 1996:4 Etlik 0.1236 0.3695 70.3590 70.2280 70.3040 70.0270 1979:2± 1996:4 Esat 0.1251 0.3336 70.4390 70.0940 0.0340 0.1640 1977:1± 1996:4 G.O.P. 0.1192 0.3489 70.3650 70.1640 70.2070 70.0540 1980:3± 1996:4 Kavaklidere 0.1128 0.5531 70.6310 70.3570 70.2430 70.1720 1977:1± 1996:4 Kecioren 0.1139 0.2152 70.3410 70.2370 70.0090 0.1680 1977:1± 1996:4 Return on ISE 0.1567 0.3041 0.1320 0.0190 70.0950 70.2320 1986:1± 1996:4 In¯ ation 0.1152 0.0566 0.2810 0.1380 0.1170 0.2010 1977:1± 1996:4

6In comparing the results with di erent in¯ ation measures, the ® rst proxy is also calculated for the period between 1986 and 1996. The results were similar to those obtained for the whole period with only slight di erences.

7These models are also tested for the median apartment values instead of the median value for apartments with 100 square metres, the results were similar to those reported here.

T ab le 4. T es t of in ¯a ti on he dg in g be ha vi ou r of qu ar te rl y re tu rn s on re si de nt ia l re al es ta te s (F am a± S ch w er t m od el ); M od el : Ri;t ˆ ¬ ‡ E… It † ‡ ® ‰I t ¡ E… It †Š ‡ et E… I1t † E… I2t † E… I3t † P er io d: 19 77 ±199 6 P er io d: 19 86 ±199 6 P er io d: 19 86 ±199 6 C oe ci en t t-St at is ti c R -s qu ar e F -s ta ti st ic C oe ci en t t-St at is ti c R -s qu ar e F -s ta ti st ic C oe ci en t t-St at is ti c R -s qu ar e F -s ta ti st ic s A yd in lik ev le r ¬ 1. 03 62 1. 66 16 0. 28 64 0. 40 14 1. 04 40 2. 01 53 0. 27 75 0. 38 41 1. 28 36 1. 14 82 0. 27 75 0. 38 41 7 7. 17 25 7 1. 24 87 7 6. 99 71 7 1. 94 03 7 9. 02 75 7 1. 07 35 ® 7 2. 88 61 7 0. 34 83 7 5. 88 29 7 2. 34 25 7 5. 88 29 7 2. 34 25 A ni tt ep e/ M al te pe ¬ 0. 27 47 2. 04 96 0. 02 42 0. 40 95 0. 11 68 0. 75 68 0. 08 79 1. 20 45 7 0. 01 08 7 0. 07 04 0. 07 39 1. 03 66 7 1. 29 29 7 1. 25 49 7 0. 21 01 7 0. 19 06 1. 03 47 0. 82 73 ® 7 0. 42 52 7 0. 45 92 7 1. 35 97 7 1. 32 41 7 1. 33 91 7 1. 24 68 A yr an ci ¬ 7 0. 04 60 7 0. 40 41 0. 03 72 1. 15 78 0. 19 07 2. 35 63 0. 16 72 3. 51 27 7 0. 07 19 7 0. 73 62 0. 17 19 3. 73 57 1. 25 12 1. 29 69 70. 63 10 71. 10 79 1. 57 86 2. 14 81 ® 70. 78 27 70. 88 90 71. 79 37 72. 33 23 71. 79 40 72. 33 26 B ah ce li/ E m ek ¬ 0. 07 77 0. 69 63 0. 00 30 0. 07 50 0. 15 21 1. 67 74 0. 00 23 0. 04 21 0. 14 25 1. 45 85 0. 00 23 0. 04 35 0. 38 68 0. 45 62 7 0. 16 49 7 0. 27 14 7 0. 08 27 7 0. 11 70 ® 0. 19 93 0. 32 68 70. 21 17 70. 29 42 70. 21 17 70. 29 44 C an ka ya ¬ 0. 23 05 1. 81 23 0. 02 34 0. 83 88 0. 05 98 0. 88 26 0. 01 16 0. 22 92 0. 23 54 1. 00 69 0. 00 78 0. 15 65 7 0. 97 74 7 0. 93 55 0. 37 17 0. 82 68 7 0. 80 81 7 0. 45 02 ® 0. 53 01 1. 07 83 0. 02 92 0. 05 80 0. 02 92 0. 05 71 C eb ec i/ D ik im ev i ¬ 0. 03 63 0. 12 89 0. 04 26 0. 71 12 0. 26 68 2. 68 28 0. 06 05 0. 99 78 0. 17 13 1. 05 88 0. 06 05 0. 99 78 0. 81 05 0. 37 40 7 0. 84 59 7 1. 30 64 7 0. 03 66 7 0. 03 06 ® 7 1. 21 07 7 1. 35 97 7 1. 29 00 7 1. 94 28 7 1. 29 00 7 1. 94 28 D em et ev le r/ Y .M ah al le ¬ 7 0. 26 29 7 1. 23 96 0. 16 39 3. 13 67 0. 22 56 1. 75 77 0. 13 92 2. 26 34 7 0. 20 92 7 0. 42 15 0. 13 92 2. 26 34 2. 97 34 1. 69 25 71. 07 31 71. 24 92 2. 61 04 0. 67 14 ® 73. 31 41 72. 89 04 73. 09 43 71. 50 92 73. 09 43 71. 50 92

In¯ ation and returns on real estate

925

D ik m en ¬ 0. 22 15 0. 86 26 0. 09 64 1. 75 97 0. 00 08 0. 00 90 0. 05 80 0. 95 49 0. 02 55 0. 18 69 0. 05 80 0. 95 49 70. 62 92 70. 33 55 1. 04 03 1. 86 97 0. 83 11 0. 94 24 ® 1. 48 36 2. 23 80 1. 15 50 1. 52 98 1. 15 50 1. 52 98 E tl ik ¬ 0. 59 84 1. 86 83 0. 15 25 1. 61 93 0. 49 69 4. 26 21 0. 20 89 2. 11 26 0. 46 41 2. 82 00 0. 20 89 2. 11 26 73. 16 33 71. 26 29 72. 20 72 73. 10 13 71. 92 90 71. 82 82 ® 7 1. 43 86 7 1. 77 80 7 2. 35 98 7 2. 73 23 7 2. 35 98 7 2. 73 23 E sa t ¬ 0. 16 21 0. 54 15 0. 01 50 0. 33 49 0. 11 18 1. 00 11 0. 11 64 2. 24 01 7 0. 23 55 7 0. 87 33 0. 11 64 2. 24 01 7 0. 26 73 7 0. 11 12 7 0. 15 49 7 0. 19 23 2. 78 69 1. 35 96 ® 7 0. 87 50 7 0. 70 52 7 1. 76 92 7 1. 57 81 7 1. 76 92 7 1. 57 81 G .O .P . ¬ 0. 17 05 0. 94 11 0. 07 06 2. 23 99 0. 23 30 2. 60 15 0. 07 98 1. 69 14 0. 07 05 0. 54 35 0. 08 07 1. 75 56 7 0. 45 27 7 0. 31 85 7 0. 85 21 7 1. 50 90 0. 49 58 0. 52 89 ® 7 1. 80 58 7 2. 98 12 7 1. 49 95 7 2. 64 86 7 1. 49 95 7 2. 65 16 K av ak lid er e ¬ 0. 05 08 0. 29 95 0. 00 49 0. 14 85 70. 00 15 70. 01 58 0. 04 69 0. 81 24 70. 12 01 70. 96 06 0. 02 95 0. 51 74 0. 40 81 0. 30 10 0. 81 37 1. 30 70 1. 95 92 2. 16 46 ® 70. 54 47 70. 67 55 70. 28 63 70. 44 48 70. 27 80 70. 43 13 K ec io re n ¬ 0. 21 25 1. 42 12 0. 02 27 0. 40 57 0. 21 52 1. 43 96 0. 02 18 0. 33 45 0. 18 85 0. 88 98 0. 02 18 0. 33 45 70. 74 39 70. 58 52 70. 82 53 70. 67 72 70. 59 91 70. 36 47 ® 7 0. 94 35 7 0. 68 52 7 0. 94 93 7 0. 68 89 7 0. 94 93 7 0. 68 89 T es ti ng eq ua lit y of s an d ®s fo r al l ne ig hb ou rh oo ds 70. 23 39 70. 52 17 4. 59 22 70. 58 08 71. 99 39 0. 11 69 0. 78 25 2. 95 93 5. 25 91 ® 7 0. 18 99 7 0. 68 91 7 1. 04 25 7 4. 00 43 7 1. 13 32 7 4. 20 27 IS E St oc ks ¬ 0. 21 60 0. 83 55 0. 01 85 0. 37 60 0. 15 33 0. 83 45 0. 03 19 0. 64 16 7 0. 02 03 7 0. 06 81 0. 03 19 0. 64 16 7 0. 44 76 7 0. 24 79 7 0. 16 68 7 0. 15 89 1. 30 34 0. 66 73 ® 7 0. 87 74 7 0. 75 37 7 0. 97 36 7 1. 00 90 7 0. 97 36 7 1. 00 90T ab le 5. T es t of F is he ri an di re ct ca us al it y m od el ; M od el : ri;t ˆ ¬ ‡ 1 E… It † ‡ 2 E… It‡1 † ¡ E… It †Š ‡ eit E… I1t † E… I2t † E… I3t † P er io d: 19 77 ±199 6 P er io d: 19 86 ±199 6 P er io d: 19 86 ±199 6 C oe ci en t t-St at is ti c R -s qu ar e F -s ta ti st ic C oe ci en t t-St at is ti c R -s qu ar e F -s ta ti st ic C oe ci en t t-St at is ti c R -s qu ar e F -s ta ti st ic s A yd in lik ev le r ¬ 7 0. 60 88 7 0. 41 94 0. 58 66 1. 41 92 0. 28 19 0. 19 59 0. 04 20 0. 04 39 0. 63 91 0. 17 29 0. 04 20 0. 04 39 1 5. 12 60 0. 42 96 7 1. 66 02 7 0. 15 80 7 4. 68 57 7 0. 15 80 2 711 .9 05 4 71. 22 57 73. 29 94 70. 12 65 79. 31 21 70. 12 65 A ni tt ep e/ M al te pe ¬ 0. 15 54 0. 77 09 0. 08 25 1. 48 30 0. 11 63 1. 23 16 0. 19 73 2. 94 97 0. 15 31 0. 63 90 0. 02 56 0. 34 14 1 7 1. 30 33 7 0. 81 80 7 0. 78 94 7 1. 49 81 7 1. 22 86 7 0. 65 21 2 7 1. 62 66 7 0. 84 18 3. 14 40 2. 63 23 2. 42 36 0. 49 89 A yr an ci ¬ 7 0. 23 63 7 1. 94 44 0. 05 83 1. 85 60 7 0. 07 86 7 0. 98 27 0. 01 15 0. 19 24 7 0. 03 15 7 0. 14 99 0. 00 68 0. 11 89 1 1. 90 32 1. 86 28 0. 45 82 0. 90 61 0. 23 33 0. 14 38 2 7 2. 38 78 7 2. 21 62 7 0. 61 21 7 0. 50 46 1. 01 46 0. 39 62 B ah ce lie vl er /E m ek ¬ 7 0. 08 45 7 0. 51 94 0. 04 10 1. 06 92 0. 07 32 1. 14 87 0. 01 01 0. 17 38 0. 19 62 1. 69 73 0. 01 41 0. 25 83 1 0. 73 58 0. 56 92 70. 47 72 71. 36 88 71. 49 24 71. 74 31 2 71. 92 26 71. 56 56 0. 17 77 0. 32 86 0. 65 33 0. 80 79 C an ka ya ¬ 0. 09 48 0. 72 49 0. 08 95 3. 43 92 70. 01 01 70. 14 59 0. 02 41 0. 45 76 0. 04 17 0. 24 00 0. 18 43 4. 40 55 1 7 0. 81 72 7 0. 76 40 0. 04 09 0. 09 20 7 0. 28 79 7 0. 21 26 2 71. 61 67 71. 53 55 70. 79 97 71. 84 82 74. 85 36 73. 39 48 C eb ec i/ D ik im ev i ¬ 0. 28 02 0. 88 72 0. 03 69 0. 61 39 0. 00 54 0. 05 48 0. 05 54 0. 88 00 0. 05 67 0. 24 17 0. 03 79 0. 61 07 1 7 2. 17 58 7 0. 90 67 0. 18 17 0. 31 63 7 0. 15 83 7 0. 09 30 2 2. 22 61 1. 45 60 7 1. 89 88 7 1. 67 83 7 3. 59 65 7 1. 50 78 D em et ev le r/ Y .M ah al le ¬ 0. 30 75 1. 08 80 0. 09 87 1. 75 22 7 0. 19 53 7 0. 88 16 0. 01 70 0. 23 42 7 0. 42 62 7 0. 80 60 0. 01 70 0. 23 42 1 7 2. 58 87 7 1. 13 59 1. 07 30 0. 74 54 3. 02 84 0. 74 54 2 4. 92 20 2. 25 62 7 0. 87 45 7 0. 32 32 7 2. 46 82 7 0. 32 32

In¯ ation and returns on real estate

927

D ik m en ¬ 0. 17 76 0. 72 12 0. 03 29 0. 56 18 0. 05 12 0. 66 89 0. 02 46 0. 39 13 0. 11 57 0. 78 01 0. 02 46 0. 39 13 1 7 1. 27 75 7 0. 71 19 7 0. 30 00 7 0. 87 83 7 0. 84 68 7 0. 87 83 2 7 0. 41 85 7 0. 30 82 0. 97 36 1. 73 10 2. 74 78 1. 73 10 E tl ik ¬ 0. 57 61 1. 30 88 0. 11 98 1. 22 48 0. 00 46 0. 03 23 0. 15 33 1. 44 86 7 0. 13 11 7 0. 39 93 0. 15 33 1. 44 86 1 7 4. 00 15 7 1. 17 07 0. 63 10 0. 70 65 1. 78 10 0. 70 65 2 7 0. 28 35 7 0. 08 94 7 4. 19 30 7 2. 69 50 7 11 .8 34 1 7 2. 69 50 E sa t ¬ 0. 03 19 0. 11 06 0. 02 32 0. 52 16 70. 02 68 70. 24 83 0. 05 07 0. 88 10 70. 06 86 70. 27 33 0. 05 07 0. 88 10 1 7 0. 28 08 7 0. 12 13 0. 19 44 0. 28 88 0. 54 87 0. 28 88 2 71. 54 67 70. 93 27 1. 91 68 1. 02 56 5. 40 97 1. 02 56 G .O .P . ¬ 0. 20 76 1. 35 07 0. 02 83 0. 85 94 70. 01 57 70. 15 18 0. 07 34 1. 46 58 70. 02 10 70. 10 72 0. 02 66 0. 53 23 1 71. 63 94 71. 33 94 0. 17 21 0. 29 06 0. 23 61 0. 16 37 2 7 0. 22 13 7 0. 19 26 7 2. 20 76 7 3. 18 67 7 2. 71 81 7 1. 09 11 K av ak lid er e ¬ 70. 22 42 70. 84 63 0. 05 44 1. 69 76 70. 04 03 70. 43 85 0. 06 75 1. 12 12 70. 19 14 70. 94 25 0. 01 23 0. 20 58 1 1. 77 02 0. 82 24 0. 28 75 0. 52 76 1. 47 50 0. 91 92 2 7 3. 39 38 7 1. 51 87 1. 66 51 1. 61 65 7 0. 93 66 7 0. 22 61 K ec io re n ¬ 0. 35 86 2. 37 45 0. 06 11 1. 13 81 0. 13 57 1. 46 83 0. 20 40 3. 58 88 0. 13 66 0. 52 32 0. 04 03 0. 60 90 1 7 2. 91 93 7 2. 32 09 7 0. 73 54 7 1. 21 35 7 1. 06 26 7 0. 53 79 2 1. 79 87 1. 10 86 4. 13 41 4. 99 86 3. 91 57 0. 58 58 T es ti ng eq ua lit y of 2 an d 2 s 1 7 1. 23 57 7 2. 02 67 5. 89 58 7 0. 62 29 7 1. 73 81 0. 14 93 7 0. 55 11 1. 25 60 3. 29 10 2 0. 02 30 0. 04 70 7 1. 25 18 7 2. 30 38 0. 25 17 0. 51 89 IS E st oc ks ¬ 0. 16 45 0. 56 11 0. 02 38 0. 48 76 70. 02 22 70. 12 90 0. 01 06 0. 19 81 70. 09 86 70. 32 19 0. 00 76 0. 14 53 1 71. 07 21 70. 51 26 0. 18 39 0. 23 50 0. 78 32 0. 39 53 2 70. 69 36 70. 46 27 0. 75 73 0. 80 48 1. 31 24 0. 62 71T ab le 6. T es t of re ve rs e ca us al it y ; M od el : E… It‡1 † ¡ E… It † ˆ ¬ ‡ ¯1 E… It † ‡ ¯2 Ri;t ‡ et E… I1t † E… I2t † E… I3t † P er io d: 19 77 ±199 6 P er io d: 19 86 ±199 6 P er io d: 19 86 ±199 6 C oe ci en t t-St at is ti c R -s qu ar e F -s ta ti st ic C oe ci en t t-St at is ti c R -s qu ar e F -s ta ti st ic C oe ci en t t-St at is ti c R -s qu ar e F -s ta ti st ic s A yd in lik ev le r ¬ 0. 20 78 7. 62 88 0. 80 51 4. 13 16 0. 02 63 0. 69 09 0. 23 68 0. 31 02 0. 02 40 0. 73 33 0. 23 68 0. 31 02 ¯1 7 1. 57 17 7 5. 01 65 7 0. 19 21 7 0. 75 88 7 0. 19 21 7 0. 75 88 ¯2 7 0. 06 04 7 3. 65 59 7 0. 01 16 7 0. 92 23 7 0. 00 41 7 0. 92 23 A ni tt ep e/ M al te pe ¬ 0. 08 54 6. 68 04 0. 33 41 8. 02 86 0. 04 07 1. 75 09 0. 10 39 1. 39 07 0. 06 50 3. 53 12 0. 26 83 6. 23 26 ¯1 7 0. 69 60 7 6. 62 30 7 0. 22 69 7 1. 60 23 7 0. 49 89 7 3. 27 47 ¯2 0. 01 18 0. 71 14 7 0. 00 26 7 0. 15 18 7 0. 00 04 7 0. 03 81 A yr an ci ¬ 0. 08 86 8. 97 27 0. 35 71 16 .3 85 9 0. 03 78 2. 23 45 0. 14 23 2. 73 77 0. 05 77 3. 78 86 0. 35 09 15 .6 79 7 ¯1 70. 74 35 77. 98 22 70. 21 82 72. 25 84 70. 49 67 73. 44 60 ¯2 70. 00 89 70. 70 69 70. 01 81 70. 62 03 70. 02 60 71. 95 37 B ah ce lie vl er /E m ek ¬ 0. 08 39 6. 70 08 0. 30 54 10 .9 91 5 0. 03 40 1. 85 43 0. 10 58 2. 06 99 0. 06 41 3. 85 74 0. 27 15 9. 12 94 ¯1 7 0. 67 96 7 7. 09 44 7 0. 21 02 7 1. 70 65 7 0. 48 99 7 3. 53 57 ¯2 70. 00 77 70. 66 50 0. 01 48 1. 46 70 70. 01 14 70. 84 58 C an ka ya ¬ 0. 08 42 10 .9 87 2 0. 38 22 21 .3 45 6 0. 03 58 2. 00 63 0. 15 11 3. 29 26 0. 05 49 5. 79 22 0. 27 39 13 .3 89 3 ¯1 7 0. 72 22 7 10 .8 86 4 7 0. 24 15 7 2. 16 80 7 0. 48 47 7 5. 34 49 ¯2 0. 02 02 1. 61 79 0. 03 80 1. 39 60 0. 02 83 1. 90 34 C eb ec i/ D ik im ev i ¬ 0. 09 10 4. 86 24 0. 36 65 8. 96 83 0. 04 37 1. 96 08 0. 12 79 2. 12 73 0. 03 24 1. 87 05 0. 12 79 2. 12 73 ¯1 7 0. 71 55 7 5. 00 75 7 0. 22 26 7 1. 73 57 7 0. 22 26 7 1. 73 57 ¯2 0. 01 11 0. 81 69 7 0. 02 50 7 1. 04 73 7 0. 00 89 7 1. 04 73 D em et ev le r/ Y .M ah al le ¬ 0. 08 77 5. 28 88 0. 29 89 6. 60 88 0. 03 74 2. 42 82 0. 18 76 3. 11 69 0. 04 98 3. 25 96 0. 25 40 5. 27 65 ¯1 7 0. 68 29 7 5. 41 51 7 0. 18 99 7 2. 11 77 7 0. 37 24 7 2. 73 56 ¯2 0. 00 42 0. 37 64 70. 02 81 71. 20 76 70. 00 59 70. 69 41

In¯ ation and returns on real estate

929

D ik m en ¬ 0. 11 24 6. 40 84 0. 39 31 10 .3 62 6 0. 04 62 2. 20 09 0. 14 21 2. 48 42 0. 01 84 0. 92 84 0. 04 92 0. 80 21 ¯1 7 0. 87 06 7 6. 82 66 7 0. 25 97 7 2. 16 88 7 0. 13 21 7 0. 89 45 ¯2 0. 01 99 1. 54 81 7 0. 00 02 7 0. 01 21 7 0. 00 09 7 0. 13 74 E tl ik ¬ 0. 12 56 3. 76 10 0. 43 91 6. 65 30 0. 05 56 2. 04 54 0. 31 63 3. 46 93 0. 05 34 1. 68 27 0. 38 10 5. 23 28 ¯1 7 1. 00 39 7 4. 30 35 7 0. 30 49 7 1. 88 95 7 0. 39 97 7 1. 71 46 ¯2 0. 00 68 0. 29 05 7 0. 03 15 7 0. 93 46 0. 00 33 0. 21 40 E sa t ¬ 0. 10 16 7. 05 13 0. 40 90 14 .8 78 5 0. 03 89 2. 58 24 0. 17 43 3. 37 80 0. 04 55 5. 90 38 0. 38 89 13 .6 84 2 ¯1 7 0. 80 39 7 7. 38 60 7 0. 22 56 7 2. 33 42 7 0. 41 12 7 6. 44 37 ¯2 0. 01 02 1. 07 66 70. 01 95 70. 90 51 0. 02 87 1. 82 72 G .O .P . ¬ 0. 09 00 9. 69 95 0. 36 20 16 .4 51 9 0. 03 89 2. 14 63 0. 12 03 2. 52 95 0. 03 94 3. 41 33 0. 13 41 4. 49 14 ¯1 70. 73 17 79. 76 48 70. 22 40 72. 12 83 70. 32 82 72. 85 04 ¯2 7 0. 00 76 7 0. 64 29 7 0. 00 89 7 0. 37 50 0. 01 92 1. 44 49 K av ak lid er e ¬ 0. 08 48 8. 46 57 0. 34 77 15 .9 94 1 0. 04 22 2. 56 35 0. 15 57 2. 94 98 0. 05 31 6. 47 83 0. 29 66 13 .2 84 9 ¯1 7 0. 70 84 7 7. 89 88 7 0. 26 10 7 2. 35 53 7 0. 45 12 7 6. 22 27 ¯2 7 0. 00 67 7 0. 81 31 7 0. 00 35 7 0. 30 22 7 0. 00 33 7 0. 42 73 K ec io re n ¬ 0. 08 95 7. 10 58 0. 42 98 12 .8 15 8 0. 05 63 2. 78 18 0. 42 60 10 .3 89 7 0. 09 50 4. 62 26 0. 58 92 22 .9 52 1 ¯1 7 0. 73 34 7 7. 79 83 7 0. 37 29 7 2. 89 81 7 0. 71 20 7 4. 88 86 ¯2 0. 02 66 1. 30 94 7 0. 01 96 7 0. 96 37 7 0. 00 19 7 0. 20 34 T es ti ng eq ua lit y of ¯1 an d ¯2 ¯1 7 0. 72 84 7 16 .7 49 3. 57 49 7 0. 13 47 7 2. 69 99 16 .4 12 3 7 0. 41 36 7 14 .2 08 3 13 .3 67 7 ¯2 0. 00 19 0. 99 76 7 0. 00 05 7 1. 24 95 0. 00 18 0. 98 75 IS E st oc ks ¬ 0. 10 74 7. 42 56 0. 41 38 13 .7 65 4 0. 04 06 2. 53 96 0. 19 78 4. 56 24 0. 03 04 2. 31 02 0. 19 78 4. 56 24 ¯1 7 0. 81 09 7 7. 66 08 7 0. 21 09 7 2. 05 69 7 0. 21 09 7 2. 05 69 ¯2 70. 01 37 71. 25 03 70. 03 36 72. 15 45 70. 01 19 72. 15 45in a perverse manner in hedging expected in¯ ation. The coe cients are not signi® cantly di erent from zero even though almost all coe cients are found to be negative regardless of the measure of expected in¯ ation.

Table 5 presents the estimations for the hypothesis that real returns are a ected only from real factors but not in¯ ation expectations. Even though the signs seem to be similar among three measures, the signi® cance of coe -cients seems to depend on the measure of expected in¯ a-tion. Most of the coe cients are found to be not signi® cantly di erent from zero, as the null hypothesis sug-gests. However, the results are slightly di erent depending on the measure of expected in¯ ation. In all of the neigh-bourhoods, the expected in¯ ation and the appreciation in house values are found to be not signi® cantly related, except in Kecioren. In the relatively high income level neighbourhoods (Ayranci, Cankaya and G.O.P.), there is a negative relationship between changes in expected in¯ a-tion and the real return on residential real estate. On the other hand, in low-income neighbourhoods , there is a posi-tive association between real returns on apartments and changes in in¯ ationary expectations. One explanation is that when the in¯ ation is expected to increase, high-income households prefer to make investment not in real estate but in other instruments. However, for low-income house-holds, the cost of renting will increase as the in¯ ationary expectations increase, as a result, the demand for owner occupancy housing will increase in the low-income neigh-bourhoods. The hypothesis that the coe cients are equal in all neighbourhoods is rejected when the expected in¯ ation rate is estimated with ARMA and Fama± Gibbons models. T est of reverse causality

Geske and Roll (1983) argue that the return on assets is not caused by the changes in in¯ ation but changes in asset prices lead to changes in in¯ ation expectations. Table 6 presents the results of this test. If Geske± Roll hypothesis holds, the coe cients on return on real estate and on in¯ a-tion are expected to be negative. In the Turkish market, the

speed of the adjustment coe cient (¯1) is found to be

sig-ni® cantly negative in almost all neighbourhoods , regardless of the proxy for expected in¯ ation. This is also true for the ISE stocks. This result suggests that investors revise their expectations for the change in in¯ ation using larger frac-tion of expected in¯ afrac-tion. This result is consistent with the ® ndings about Turkish in¯ ation that it can be predicted by examining only past period in¯ ation rates (Alper and Ucer, 1998) .

When the coe cients on nominal returns on residential real estate investment are observed, the results do not sup-port Geske± Roll argument. Almost all coe cients are found to be not signi® cantly di erent from zero. So, as the return on real estate changes, we do not observe any signi® cant change in expected in¯ ation. However, ISE

stocks behave as suggested by Geske and Roll (1983). As the return on ISE stocks increases (decreases), there is a signi® cant decrease (increase) in the in¯ ationary expecta-tions.

V. CONCLUSI ONS

This study examined the hedging behaviour of real estates against expected and unexpected in¯ ation under high in¯ a-tionary environment using three di erent proxies for expected in¯ ation. The returns on real estate investments in 13 neighbourhoods in Ankara are analysed. The results suggest that unlike the behaviour of real estates in other countries, real estate investment in Ankara does not pro-vide hedge against in¯ ation. We do not observe a reverse causality between returns on real estate and changes in expected in¯ ation. However, a relationship between real returns and changes in in¯ ationary expectations seem to be di erent in relatively low and relatively high income neighbourhoods.

The insigni® cant results for the hedging behaviour of real estate in Ankara can be explained with the lenders’ behaviour under high in¯ ationary environment. Lenders adjust the interest rate on loans periodically under in¯ ationary environment. Hence, the relative cost of owner-occupied housing will not be lower or investing in owner-occupied housing will not be in¯ ation neutral. As a result, we do not observe an increase in demand for housing. Hence, positive relationship between returns on real estate and both expected and unexpected in¯ ation will not be observed. Similarly, if households think money market instruments as alternatives to real estate invest-ment, as in¯ ation increases, the demand for owner-occupant housing will decline when the government tries to keep the positive real interest rate.

This study has some limitations. First, the data used in calculating returns on real estate are based on the charac-teristics of apartments on sale at the end of each quarter. Since di erent apartments are for sale in di erent periods, their characteristics will change, resulting in high variabil-ity in the returns on real estate. Second, apartments with reported value and size ® gures are included in the sample. Consequently, it can be argued that it does not fully repre-sent the median value of all apartments on the market for sale at that time.

R EFER ENCES

Alper, C. E. and Ucer, M. (1998) Some observations on Turkish in¯ ation: a random walk down the past decade, Bogazici University, Department of Economics, working paper. Baharoglu, D., Hannah, L. M. and Malpezzi, S. (1997) Getting

housing incentives right in Turkey, paper presented in the 1997 European Real Estate Meetings.

Bodie, Z. (1976) Common Stocks as a hedge against in¯ ation, T he

Journal of Finance, 31(2), 459± 70.

Fama, E. F. and Gibbons, M. R. (1982) In¯ ation, real returns and capital investment, Journal of Monetary Economics, 9, 297± 323.

Fama, E. F. and Schwert, G. W. (1977) Asset returns and in¯ a-tion, Journal of Financial Economics, 5, 115± 46.

Federal National Mortgage Association (FNMA) (1992) Creating

a Market Oriented Housing Finance System in T urkiye,

Report prepared for the Housing Development Administration of Turkey.

Firth, M. (1979) The relationship between stock returns and rates of in¯ ation, T he Journal of Finance, 34(3), 743± 9.

Gartzla , D. H. (1994) Excess returns, in¯ ation and e ciency of the housing market, Journal of American Real Estate and

Urban Economics Association, 22(4), 553± 81.

Geske, R. and Roll, R. (1983) The ® scal and monetary linkage between stock returns and in¯ ation, T he Journal of Finance, 38(1) , 1± 33.

Goodwin, T. H. (1986) In¯ ation, risk, taxes and the demand for owner-occupied housing, Review of Economics and Statistics, 68(2) , 197± 206.

Gultekin, N. B. (1983) Stock market returns and in¯ ation: evi-dence from other countries, T he Journal of Finance, 38(1), 49± 65.

Gyorko, J. P. L. (1988) Owner-occupied homes, income-producing properties, and REITs as in¯ ation hedges:

empiri-cal ® ndings, T he Journal of Real Estate Finance and

Economics, 1, 347± 72.

Korum, U. (1982) 1980 ve 1981 yillarinda Konut Piyasasi, Konut

81, Kent-Koop Yayinlari, No. 20, Ankara.

Liu, C. H., Hartzell, D. J. and Hoesli, M. E. (1997) International evidence on real estate securities as an in¯ ation hedge, Real

Estate Economics, 25(2), 193± 221.

Manchester, J. (1987) In¯ ation and housing demand: a new per-spective, Journal of Urban Economics, 21, 105± 25.

Nelson, C. R. (1976) In¯ ation and rates of return on common stocks, T he Journal of Finance, 31(2), 471± 83.

OÈ zmen, E. (1998) Is currency seigniorage exogenous for in¯ ation tax in Turkey? Applied Economics, 30, 545± 52.

Park, J., Mullineaux, D. J. and Chew, I. K. (1990) Are REITs in¯ ation hedges? T he Journal of Real Estate Finance and

Economics, 3, 91± 103.

Poterba, J. M. (1984) Tax subsidies to owner-occupied housing: an asset-market approach, T he Quarterly Journal of

Economics, 99(4), 729± 52.

Solnik, B. (1983) The relation between stock prices and in¯ ation-ary expectations: the international evidence, T he Journal of

Finance, 38(1), 35± 48.

Summers, L. H. (1981) In¯ ation, the stock market, and owner-occupied housing, American Economic Review, 71(2), 429± 34. Turel, A. (1981) Ankara’da Konut Fiyatlarinin Mekansal

Farklilasmasi, ODT U Mimarlik Fakultesi Dergisi, 7(1), 97± 109.