THE CORRELATION BETWEEN ANXIETY AND EMOTIONAL

INTELLIGENCE IN FOREIGN LANGUAGE LEARNING

MA THESIS

By: SEVĐNÇ YERLĐ

Supervisor:

Assist. Prof. Dr. Aslı Özlem TARAKÇIOĞLU

THE CORRELATION BETWEEN ANXIETY AND EMOTIONAL INTELLIGENCE IN FOREIGN LANGUAGE LEARNING

MA THESIS

By: SEVĐNÇ YERLĐ

Supervisor:

Assist. Prof. Dr. Aslı Özlem TARAKÇIOĞLU

Intelligence in Foreign Language Learning” (Yabancı Dil Öğreniminde Kaygı ve Duygusal Zekâ Arasındaki Korelâsyon) başlıklı tez, jürimiz tarafından 27/05/2009 tarihinde Eğitim Fakültesi Đngilizce Öğretmenliği Anabilim Dalında YÜKSEK LĐSANS Tezi olarak kabul edilmiştir.

Adı - Soyadı Đmza

Üye (Tez Danışmanı): Yrd. Doç. Dr. Aslı Özlem TARAKÇIOĞLU ………….

Üye: Doç. Dr. Gülsev PAKKAN ………….

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

First of all, I would like to express that I am grateful to the ones who did not hesitate to help and support me during the preparation process of my thesis.

I should specially thank to my supervisor Assist. Prof. Dr. Aslı Özlem TARAKÇIOĞLU for her great help and contribution.

I also would like to express my deepest gratitude for all my teachers who always supported and encouraged me during my education life.

I should thank to Assist. Prof. Dr. Đzzet KILINÇ and Research Assist. Muammer MESCĐ, for their great contribution and valuable comments.

And, my deepest gratitude is for my precious family and friends who were always with me believing and supporting.

Özet

Geçtiğimiz 20 yıl içerisinde, Duygusal Zeka kavramıyla ilgili tartışmalar giderek artmış, insanlar hayatta başarılı olmaları için gereken zekanın yalnızca IQ ile sınırlı olmadığını, aynı zamanda Duygusal Zeka kavramının da başarıyı yakalamakta önemli rol oynadığını fark etmeye başlamışlardır.

Öte yandan, yabancı dil öğrenimini olumsuz yönde etkileyen duygusal faktörler de yabancı dil öğretmenleri ve öğrencileri için yıllar boyu önemli bir problem teşkil etmiştir.

Bu çalışmada, duygusal faktörlerden olan kaygı ve duygusal zeka arasındaki ilişki incelenmiştir. Yabancı dil öğrenimi sürecinde yaşanılan kaygının nasıl azaltılabileceği ile Duygusal Zeka kavramının eğitim sürecindeki rolü araştırılmış ve bazı öneriler sunulmaya çalışılmıştır. Kaygı ile Duygusal Zeka arasındaki korelasyon incelenmiş ve yabancı dil sınıflarında kaygıyı azaltmak için Duygusal Zeka kullanımının öneminden bahsedilmiştir.

ABSTRACT

For the past two decades, questions about Emotional Intelligence have started to arise. Apart from IQ, people wanted to learn about the missing part of their intelligence, EQ. They realized that, IQ was not enough itself to bring success, but another dimension; emotional intelligence had also a big role in success equation.

On the other hand, the affective factors that obstruct foreign language learning have long been a vital problem for language learners and teachers.

In this study, the relationship between “Anxiety” and “Emotional Intelligence” was examined. Some suggestions for alleviating language anxiety were presented and the role of Emotional Intelligence in educational settings was tried to be shown. The correlation between Anxiety and Emotional Intelligence was tried to be emphasized, and the usage of Emotional Intelligence in foreign language classes to alleviate anxiety is also mentioned.

TABLE OF CONTENTS

ACKNOWLEDGEMENT... i

ÖZET... ii

ABSTRACT... iii

TABLE OF CONTENTS... iv

LIST OF TABLES... vii

CHAPTER I INTRODUCTION 1.0 Presentation... 1

1.1 Background to the Study... 1

1.2 Problem of the Study... 6

1.3 Aim of the Study... 7

1.4 Significance of the Study... 8

1.5 Scope and Limitations of the Study... 8

CHAPTER II REVIEW OF LITERATURE 2.1 Introduction... 9

2.2 What is Anxiety... 9

2.2.1 Components of Language Anxiety... 11

2.3 What Maintains Anxiety... 13

2.4 Types of Anxiety... 19

2.5 Anxiety and Foreign Language Learning... 21

2.5.1 Facilitating and Debilitating Anxiety... 25

2.5.2 How Does Language Anxiety Affect Language Learning and Students’ Performance... 26

2.6 Creating an Emotionally Healthy Classroom Atmosphere ... 30

2.7.1 Models of Emotional Intelligence... 40

2.7.1.1 Ability Models of Emotional Intelligence... 40

2.7.1.2 Trait Emotional Intelligence Model... 44

2.7.1.3 Mixed Models of Emotional Intelligence ... 48

2.7.1.3.1 The Bar-On Model of Emotional-Social Intelligence... 48

2.7.1.3.2 The Emotional Competencies (Goleman) Model………... 51

2.8 Teaching Strategies and Emotional Intelligence... 61

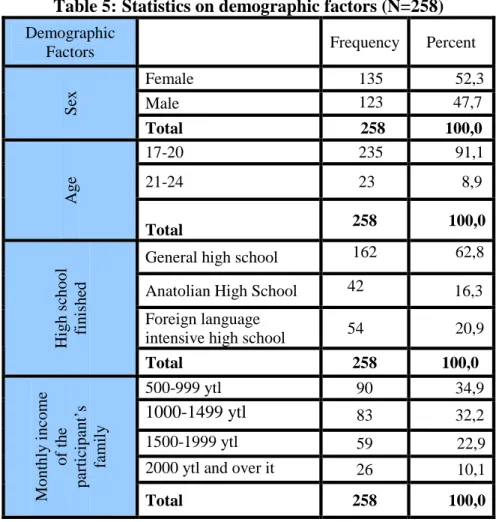

2.8.1 Helping Students Overcome Language Anxiety by Using EI... 65 CHAPTER III DATA COLLECTED 3.1 Introduction………..…… …… 70 3.2 Data Collection……… 70 3.3 Data Analysis……… 71 3.3.1 Demographic Factors……… 71

3.4 Analysis and Evaluation of Anxiety Questionnaire (FLCAS)……… 74

3.4.1 Reliability of the Data………..….………… 74

3.4.2 Factor Analysis for FLCAS………..………… 76

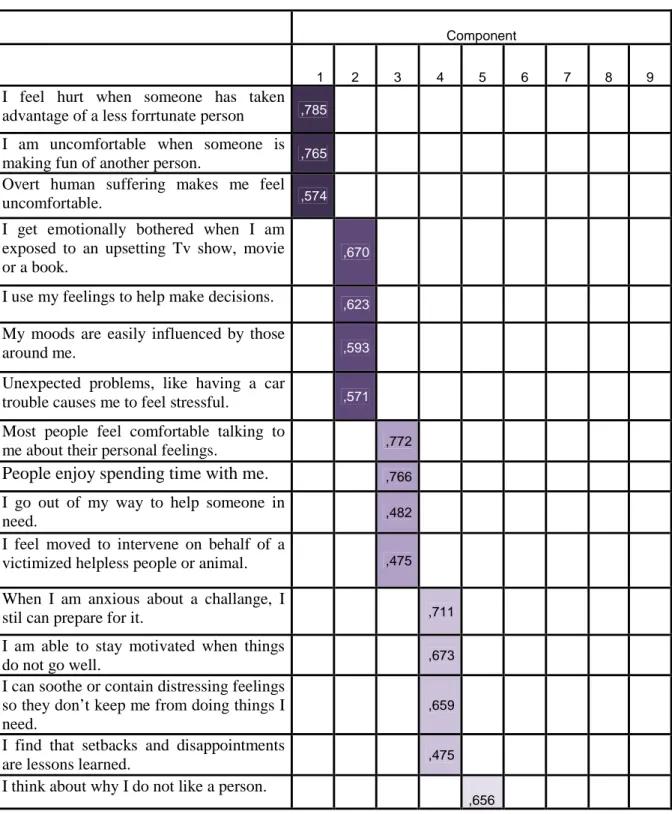

3.5 Emotional Intelligence Inventory……… 89

3.5.1 Reliability of the Data………... 90

3.5.2 Factor Analysis for Emotional Intelligence Inventory…... 93

3.6 Correlation Analysis……….... 104

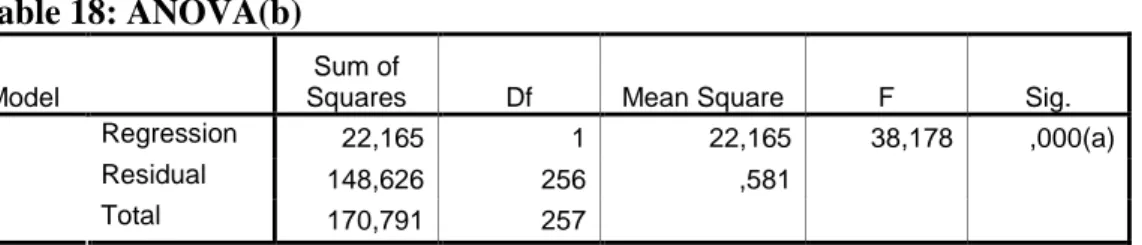

3.7 Regression Analysis………. 109

CHAPTER IV CONCLUSION AND SUGGESTIONS 4.1 Introduction……….. 111

4.2 Foreign Language Classroom Anxiety Scale……… 111

4.3 Emotional Intelligence Inventory……….… 112

REFERENCES………... 116

APPENDICES……… 125

APPENDIX A: Foreign Language Classroom Anxiety Scale……… 126

LIST OF TABLES

Table1: Anxious and Good Learners………... 32

Table 2: Four branches of Emotional Intelligence………... 43

Table 3: The Adult Sampling Domain of Trait Emotional Intelligence……..… 47

Table 4: Models of Emotional Intelligence……….… 60

Table 5: Statistics on Demographic Factors………... 71

Table 6: Number of Female and Male Participants……… 72

Table 7: Ages of the Participants……… 72

Table 8: High School Finished………... 73

Table 9: Dispersal of Monthly Income………...… 73

Table 10: KMO and Barlett’s Test for FLCAS……….. 74

Table 11: Scree Plot for FLCAS……….… 75

Table 12: Rotated Component Matrix (FLCAS)……… 76

Table 13: KMO and Barlett’s Test for EI Inventory……….. 90

Table 14: Scree Plot for EI Inventory……….… 90

Table 15: Rotated Component Matrix (EI)………... 91

Table 16: Correlations……….… 105

Table 17: Model Summary………..…... 109

Table 18: Anova………..……….... 109

CHAPTER I

INTRODUCTION

1.0 Presentation

This chapter tries to give the reasons why the present study, “The Correlation between Anxiety and Emotional Intelligence in Foreign Language Learning” is made. This chapter has five sections; 1.1 Background to the study gives some information about background of the study, 1.2 Problem of the Study tries to define the main problem that led to this study, 1.3 Aim of the Study gives the reasons to make this study, section 1.4 explains significance of the study and the last section 1.5 gives information about Scope and Limitations of this study.

1.1 Background to the study

As the world is getting bigger and global, the borders between countries and between people are getting narrower. So the number of foreign language learners is increasing; and the importance of foreign language learning is also improving. To be able to express yourself in a foreign language seems to be an inevitable necessity of the global world. With this belief, foreign language teaching -especially English- has been popular for years in many countries. But, learning a language is a complex process that involves cognitive and affective factors, influencing the learning process. And the teaching process is not that easy all the time, as there may be some obstacles both for teachers and students, so there seems to be a need for more studies on language learning- mainly for English language learning studies. One of the most important problems that impedes language learning process is language anxiety.

The study of language anxiety is not a new field. Language teachers have long been aware of the fact that many of their students experience discomfort in language learning environment. Researchers have been looking at language anxiety for nearly three decades now as one of the most important affective factors that affects performance and achievement in FL classes.

But the academic literature; however, has offered a somewhat confusing knowledge on language anxiety. Researchers have been unable to state a clear picture on the effects of language anxiety on language learning and performance.

The first review on the then available literature, about the relationship between anxiety and FL learning, was the one done by Scovel in 1978, which made reference to several other studies later.

Although the studies reviewed yielded inconsistent results, they all shared a common soul; they were the first studies to mention the effects of anxiety on foreign language learning.

While many studies have found that anxious students are less successful at language learning, several studies have shown that there is no relationship between anxiety and language learning, and there are very few studies which suggest that anxiety facilitates language learning.

For example, in a large study, Chastain (1975) found a negative correlation between French audio-lingual method student scores on tests and anxiety, but, in contradiction, he discovered a positive relationship between anxiety and the scores of German and Spanish students using the traditional model.

According to Chastain (1975), a little concern about a test may be a plus for the students but too much anxiety can produce negative results for them.

Almost a decade after Scovels’s study, Horwitz et al. (1986) researched the subject, language anxiety, and they described and clarified the effects of anxiety.

"Just know I have some kind of disability: I can't learn a foreign language no matter how hard I try."

"When I'm in my Spanish class I just freeze! I can't think of a thing when my teacher calls on me. My mind goes blank."

“Sometimes when I speak English in class, I am so afraid I feel like hiding behind my chair”

“I dread going to Spanish class. My teacher is kind of nice and it can be fun, but I hate when the teacher calls on me to speak. I freeze up and can’t think of what to say or how to say it. And my pronunciation is terrible. Sometimes I think people don’t even understand what I am saying”

The quotations above (Horwitz et al., Horwitz 1986:125, 1991: xiii) were taken from students’ journals, which show their negative feelings toward language learning. And, it is clear from these sentences that, anxiety has an obstructive effect on language learning.

Such statements are all too familiar to teachers of foreign languages. Many people claim to have a mental block against learning a foreign language, although these same people may be strongly motivated good learners in other situations, but they may have difficulties while trying to communicate in the foreign language. What, then, prevents them from achieving their desired goal? In many cases, they may have an anxiety reaction which hinders their ability to perform successfully in a foreign language class. (Horwitz and Cope, 1986)

Although communication apprehension, test anxiety, and fear of negative evaluation provide useful conceptual building blocks for a description of foreign language anxiety, we propose that foreign language anxiety is not simply the combination of these fears transferred to foreign language learning. Rather, we conceive foreign language anxiety as a distinct complex of self-perceptions, beliefs, feelings, and behaviors related to classroom language learning arising from the uniqueness of the language learning process. (Horwitz and Cope, 1986:128)

In their study, Horwitz and Cope (1986) also offered an instrument, the Foreign Language Classroom Anxiety Scale (FLCAS), which was developed to measure anxiety and to clarify its effects on language learning process.

The results of this study showed that anxiety has a negative effect on foreign language classes. The results also suggested that ‘anxious students feel uniquely unable to deal with the task of language learning.’

Their findings also suggest that significant foreign language anxiety is experienced by many students in response to at least some aspects of foreign language learning. So, foreign language teachers should be aware of anxiety in language classes and should take some precautions to overcome it.

There are some factors that affect language learning process in a way; these are cognitive factors and affective factors. Among the affective factors emotions, feelings, and also anxiety take place.

“Affective variables have often been defined as the converse of cognitive variables; that is, they are everything which impinges on language learning which is unrelated to cognition.” (Scovel, 1991:15)

By the 1980s, cognition research was the dominant theory that framed research in linguistics, psychology, brain science, and ultimately language learning pedagogy, in the 1980s, however, brain scientists began to recognize that cognition research explains only a part of how the mind works, only that part related to reasoning and thinking; they had neglected emotions. (Young, 1999:18)

But as we know now, minds without our emotions are very isolated; they are cold, lifeless creatures far away from desires, fears, sorrows, pain or pleasure.

“Brain scientists found that emotions could exist before cognition and could also be independent of cognition.” (Young, 1999:18)

As it is clear now, the term affect deals with emotions, feelings, thoughts, mood and attitudes of human behavior. When affective factors are examined, as Fox defines (1993:21) "the main focus is on understanding the pupil's feelings or emotional responses to the different situations.”

“The affective component includes those feelings and attitudes individuals hold toward themselves and their environment. Affective refers to the individuals’ emotional characteristics as opposed to their intellectual and social traits.” (Chastain, 1976:176)

According to Scovel, “affective variables are those factors which deal with vedana (feelings), the emotions of pleasure and displeasure that surround the enterprise of a task such as second language learning.” (1991:16) Affective variables include the items like attitudes, motivation, language anxiety and self confidence.

On the other hand, the cognitive factor deals with of mental processing. Cognitive psychologists perceive learning as internal and mental. Cognitive variables include the items like, mental intelligence, language aptitude and language learning.

The affective factor is the emotional side of human behavior in the language learning process (such as motivation, attitudes and anxiety). Although both factors affect students' performance in language learning, some researchers state that affective factors are more important than cognitive factors.

Psychologists such as; Robert Gardner, Guiora (1972), Lambert (1967), Krashen (1982), Dulay and Burt (1977) have done some researches on second language learning and affective variables. (as cited in Young, 1999:20)

One of these researches, done by Dulay and Burt (1977) (as cited in Young 1999: 20), contains a metaphor in which emotions act as a filter that controls whether language is allowed to flow into the language-learning system in brain.

“…if anxiety is high, the filter is up and the information doesn’t enter the brain’s processing system, however; if the filter is down, the brain’s operating systems can focus on processing the foreign language input.” (Young, 1999: 20)

Some researchers advocate that difficulties in foreign language learning process (especially psychological ones such as; stress, anxiety…) are mostly caused by affective variables. Young supports this idea with this quotation:

“Research in affective variables in language learning helped explain why some learners had more difficulty than others in learning a foreign language.” (Young, 1999:19)

For decades, a lot of emphasis has been put on certain aspects of intelligence such as logical reasoning, math skills, spatial skills, understanding analogies, verbal skills etc. Researchers were puzzled by the fact that, while IQ could determine to a significant degree academic performance and, to some degree, professional and personal success, some of those with great IQ scores were doing poorly in life. There was something missing in the success equation.

One of the major missing parts in the success equation is “emotional intelligence”, a concept made popular by Daniel Goleman whose famous book based on years of research on numerous scientists such as Peter Salovey, John Mayer, Howard Gardner, Robert Sternberg and Jack Block. For various reasons and thanks to a wide range of abilities, people with high emotional intelligence tend to be more successful in life even if their classical IQ is average.

Emotional intelligence is “…the abilities such as being able to motivate oneself and persist in the face of frustrations; to control impulse and delay gratification; to regulate one’s moods and keep distress from swamping the ability to think; to empathize and to hope.” (Goleman, 1995: 36)

So, emotional Intelligence should be used in all areas of life, especially in education, to help students experience a more relaxed classroom environment. . In this study, the main aim is to show the importance of emotional intelligence in educational settings.

As Young states (1999:18-21), emotional part of learning has been ignored for so long for many different reasons. As it has been ignored, the problems students faced with in the learning process have also been ignored. In this study, the effects of language anxiety (an affective factor) are going to be mentioned, and Emotional Intelligence (another affective factor) is going to be put into action to overcome language anxiety.

As Chastain explained (1976), affective variables are prior to cognitive factors for several reasons. He asserts that influence of attitudes and feelings on students’ achievement is higher than cognitive factors’ influences. It is clear from the research that anxiety impedes language learning. So, in order to create a positive and fruitful classroom environment, language teachers should refer to students’ emotions, and emotional intelligence. Therefore, the main subject of this study is the correlation between two important affective variables, - “Anxiety” and “Emotional Intelligence”.

1.2 Problem of the Study

Language students in Turkey, especially at prep class level; do not actively participate and do not speak in English in classes. They tend to speak in their native language as much as possible and it has been a very big handicap for language teachers. As students do not participate in classroom activities, they will not learn very effectively. The main reason found to prevent students from participating in language classes is language anxiety; therefore, it seems to be a harmful problem that obstructs language learning.

According to Horwitz and Cope (1986), students who experience high anxiety, are afraid of speaking in the foreign language classes, they feel a deep self-consciousness when asked to reveal themselves by speaking the foreign language in the presence of other people. (Horwitz and Cope, 129-131)

Anxious students are also afraid of being less competent than other students or being negatively evaluated by them. Shortly saying, anxious students are afraid of making mistakes in the foreign language classrooms, which impede their performance and achievement. (Horwitz and Cope, 1986:129-131)

The questions below are the research questions to be investigated in this study. Research Questions:

1. Does anxiety affect students’ performance in foreign language classrooms?

2. What kind of a correlation is there between anxiety and emotional intelligence?

3. May students having higher EQ be more successful than the others for their language skills in language learning classes?

4. May the anxiety experienced in foreign language classes be alleviated by using Emotional Intelligence?

1.3 Aim of the Study

Second language scholars and theorists have long been aware that anxiety is an important problem associated with foreign language learning. Language teachers and students strongly claim that anxiety is the key determiner of learners’ performance, achievement and success in language learning classrooms. When students experience anxiety, they cannot concentrate on learning, and as a result; they might fail in performing a task in classrooms. As it has been seen, anxiety may be the most dangerous obstacle for language learners; and it seems to be nearly impossible to teach language to the students who are anxious about it. So, the aim of this study is to show the relationship between anxiety and students’ participation and achievement in language learning classrooms and to find out how emotional intelligence (EI) can help to overcome this problem.

1.4 Significance of the study

It is not possible to teach anything, to the students who have some negative feelings about the learning process. As it has been mentioned earlier, affective factors play a very important role in terms of teaching and learning. So, in order to be able to teach, teachers should establish a positive classroom environment first.

“The extent to which emotional upsets can interfere with mental life is no news to teachers. Students who are anxious, angry or depressed do not learn; people who are caught in these states do not take in information efficiently or deal with it well.” (Goleman, 1995:89) “…powerful negative emotions twist attention toward their own preoccupations, interfering with the attempt to focus elsewhere” (Goleman, 1995:89)

The findings of this study will contribute to research on the negative effects of language anxiety, and the importance of Emotional Intelligence. It will help both language teachers and learners who experience some difficulties stemming from language anxiety in the learning process, in terms of establishing a positive classroom environment.

1.5 Scope and Limitations of Study

Anxiety has been found to have a negative effect on the language learning process. As anxiety approved to be an important problem in the language learning process, scholars have studied the subject from many different aspects so far. And this study, will deal with the relationship between anxiety and students’ emotional intelligence level in language learning classrooms. It will also present some suggestions for teachers in order to tackle this problem.

The limitations of this thesis are:

1. This thesis is limited to university prep school level only.

2. It will be limited to students attending English prep school from different departments.

3. It will be limited to level-A (beginner) students only.

CHAPTER II

REVIEW OF LITERATURE

2.1 Introduction

In this part, Anxiety and Emotional intelligence will be mentioned. Both variables will be explained, and overviewed.

2.2 What is Anxiety?

Anxiety is almost impossible to define in a simple sentence. There are many definitions for this term. For example, Powell states that (1990: 23) ‘‘anxiety is defined in the broadest possible sense as a series of physical, cognitive, and behavioral responses to stress’’. And Vaughn, Bos and Schumm explain that (2000: 200) "anxiety refers to extreme worry, fearfulness and concern (even when little reason for those feelings exists)". According to Fox (1993: 22), anxiety is related with one's believing that he is not safe, a belief that may be connected with illness, physical harm or social rejection. And for Powell, anxiety is a complex psychological construct related with feeling of uneasiness, frustration, insecurity or self-doubt. (1990: 22-42).

Anxiety is a normal reaction to stressful occasions in one’s life. It helps one deal with a tense situation in the office, study harder for an exam, and keep focused on an important speech. In general, it helps one cope. But when anxiety becomes an excessive, irrational dread of everyday situations, it has a debilitating effect.

“Anxiety is the subjective feeling of tension, apprehension, nervousness, and worry associated with an arousal of the autonomic nervous system.” (Spielberger, 1983:1 in Horwitz, 2001:113)

Most people have already experienced such a feeling in life; before performing an important task, while taking an important exam, or even before meeting a stranger. So, this is easy to say; anxiety is the feeling that everybody knows in a way. But some know its facilitating effects, on the other hand; some experience its debilitating effects.

“Anxiety is commonly described by psychologists as a state of apprehension, a vague fear that is only indirectly associated with an object.” (Hilgard, Atkinson, & Atkinson, 1971 in Scovel, 1991:18)

According to these definitions anxiety is a kind of fear that may cause a negative feeling in the classroom. For example, lots of people have experienced anxiety to some extent while learning a foreign language. It happens when one doubts in his/her abilities of performing a certain task and he/she feels nervous about succeeding in it.

“Studies about language anxiety range from investigations of how factors such as instructional organization...affect learning, to examinations of how language anxiety is related to and different from other types of anxiety.” (Horwitz, 1991: xiii)

As terms like anxiety, intelligence and motivation are abstract ones; it is very difficult to be able to easily define someone as anxious.

But according to Gaudry and Spielberger (1971) anxiety level can be determined in a variety of ways; such as Verbal Reports, Psychological Indications and General Behaviour.

A student may refuse to make a speech of thanks to a distinguished visitor who has addressed the school assembly. The reluctant speaker may state that he refused to take on task because he gets so nervous in such situations that he has great difficulty in marshalling his thoughts. Or he may state that he shakes and trembles so much that he becomes incapable of commencing or completing his speech. (Gaudry and Spielberger, 1971:7)

As anxiety is an emotional factor in language learning process, defining students’ language learning anxiety can be a bit difficult. There are not certain proofs for it, and it is also very difficult to define someone as anxious only looking at his/her behaviours. But anyway, Gaudry and Spielberger, (1971) assert some signs for defining anxious people.

In the presence of signs such as tremor in the limbs, sweating of the hands and forehead and flushing of the neck and face, is deemed to be an indication of anxiety. In more controlled laboratory situations, psychological measures of heart rate, blood pressure and sweating have been used to assess the extent of emotional response to stressful situations. (Gaudry and Spielberger, 1971:7)

According to Gaudry and Spielberger; anxiety can also be inferred from general behavior signs such as; restlessness, tenseness of posture, pacing around the room, increased rate of speech and general distractibility. (Gaudry and Spielberger, 1971)

These three examples of ways to assess anxiety level also illustrate that there is no qualitative way to define an affective construct such as anxiety, and in the teaching process; teachers bear a hard work as they are the ones to analyze their students’ feelings, and to help them.

2.2.1 Components of Language Anxiety

Language anxiety is an abstract term which is very difficult to define in a simple sentence. Horwitz and Cope were the first scientists to analyze deeply what language anxiety is. Horwitz, Horwitz and Cope (1986) outline a theoretical framework from which to begin. They try to explain what foreign language anxiety is and describe the components of this term.

The first component is communication apprehension. The second one which is closely related to the first one is the fear of negative social evaluation and the last component is test anxiety. Horwitz, and Cope (1986) claim that all these components have inhibitive effects on second language learning.

According to Horwitz and Cope (1986:127) “communication apprehension or some similar reaction obviously plays a large role in foreign language anxiety.” People who typically experience difficulty speaking in groups are likely to experience even greater difficulty speaking in a foreign language class where they have little control of the communicative situation.

Communication apprehension, the anxiety experienced in interpersonal settings, has been found to be related to both learning and recall of vocabulary items. (Gardner, Lalonde et al., 1987; MacIntyre & Gardner, 1989 in Bailey et al., 1999:220) Therefore, students with high levels of communication apprehension appear to be disadvantaged from the outset because basic vocabulary learning and production are impaired. (Bailey et al., 1999:220)

Speaking in the target language can be defined as the most stressful situation for nearly all of the foreign language learners. Young claims that having to speak in

the target language in front of a group is at the base of the anxieties related to classroom procedures. (Young, 1991:426-429) They experience stress and tension and generally want to escape from this situation.

But for those students who ignore speaking opportunities, this is a real disadvantage. As speaking activities include both basic vocabulary usage and production skills, those who do not prefer to speak in the target language are totally disadvantaged.

Fear of negative evaluation, defined as “apprehension about others’ evaluations, avoidance of evaluative situations, and the expectation that others would evaluate one self negatively,” is a third anxiety related to foreign language learning. (Horwitz and Cope, 1986:128)

“Since performance evaluation is an ongoing feature of most foreign language classes, test anxiety is also related to a discussion of foreign language anxiety. Test anxiety refers to a type of anxiety stemming from a fear of failure.” (Gordon & Sarason, 1955; Sarason, 1980 in Horwitz and Cope, 1986:127)

Test anxious students aren’t strangers for language teachers; because nearly in all language classes there are a few test-anxious ones who can be easily noticed. Those students often feel that anything except from a good grade from a test is a failure. And test-anxious students experience more difficulty in language classes than other classes as there are lots of tests and quizzes.

Although communication apprehension, test anxiety and fear of negative evaluation provide useful conceptual building blocks for a description of foreign language anxiety, we propose that foreign language anxiety is not simply the combination of these fears transferred to foreign language learning. Rather, we conceive foreign language anxiety as a distinct complex of self- perceptions, beliefs, feelings and behaviors related to classroom language learning arising from the uniqueness of the language learning process. (Horwitz and Cope, 1986:128)

As each classroom has its own dynamics and learning atmosphere, language anxiety is not only seen as the pure combination of its components (communication apprehension, test anxiety and fear of negative evaluation) but also as a mixture of beliefs, feelings and behaviors arising in the classroom.

2.3 What Maintains Anxiety

There seems to be many different factors found to be reasons of language anxiety, among them psychological ones play an enormous role. Language students’ self perceptions about the language learning process and the outer effects that are related to this process are the first ones to be mentioned. Researchers have different ideas about this point but most of them have a common soul.

Powell states that (1990:77) "there are a number of general factors which can serve to maintain anxiety." For Powell, the reasons which maintain anxiety are; lifestyles of the people, avoidance, loss of confidence and our thinking.” (1990:22-77) For example, people who have the particular stressful lifestyles may have become blocked in. People have resources and demands in life, and if the demands upon them outweigh their resources this will create stress and will continue to do so until they act either to strengthen their resources or reduce the demands upon them or both.

Another behavioral pattern which maintains anxiety is avoidance. People seem to avoid the situations which caused their fear or high level of stress. If a person avoids a particular situation, the opportunity to communicate simply is not available. According to Foss and Reitzel, (1988:442) “some second language learners may choose not to communicate in a situation because they judge their capabilities in the new language to be so poor that not communicating is perceived as more rewarding than doing so.”

A third factor that maintains anxiety is "loss of confidence". As Powell defines (1990:79) "a person's confidence stems very largely from seeing he/she copes effectively with all of life's everyday demands and challenges." The confident person feels happy to try new thing as they have had success at similar related tasks before.

Powell also suggests that (1990:80) "the degree to which a person feels confident at performing any given task can in some ways be thought of as a 'circle of safety'.” A person full of confidence feels safe in many things, thus their circle of safety is very large, they can perform the given task anytime. For people with anxiety problems however, it is common to avoid the difficult situations and tasks because they lack the self-confidence to deal with them effectively.

Our thinking also seems to maintain anxiety. Fear and other difficulties lead to avoidance of the problem situation. Very commonly anxious and stressed people express thoughts of self-doubt and self-deprecation. As anxiety takes over their lives they feel locked and unable to get free. The more people feel like this, the more these feelings become automatic and fixed and the less they are able to see a future for themselves. They may adapt a negative outlook on life, tending to anticipate and see problems where none exist, finding things to worry about and these all maintain anxiety better.

Young (1991) (in Young 1999) offered an extensive list of the potential sources of language anxiety stemming from the teacher, the learner and the instructional practice. According to her research, (1991:427), language anxiety arises from: 1) personal and interpersonal anxieties; 2) learner beliefs about language learning; 3) instructor beliefs about language teaching; 4) instructor-learner interactions; 5) classroom procedures; and 6) language testing.

According to this list, a learner’s personal problems such as low self-esteem, and interpersonal problems, like fear of losing one’s sense of identity, competitiveness and so on can be the basic seeds of anxiety. (32-33) For example; competitiveness can easily lead to anxiety when language learners are compared with other learners. Besides, people with low self-esteem worry about what their peers think; they are concerned with pleasing others. And they are often afraid of speaking in the target language, as it is very important for them not to be laughed by others.

Young claims that “students who start out with a self-perceived low ability level in a foreign or second language are the likeliest candidates for language anxiety, or any other type of anxiety for that matter.” (1991:248)

Young also proposes that other anxieties stemming from personal or interpersonal reasons are communication apprehension, social anxiety and anxiety specific to language learning, that’s to say; language anxiety stems from the personal or interpersonal issues in the language learning context. (1991:426-439)

Apart from these, unreal beliefs of learners’ about language learning and intimidating teacher attitudes (such as harsh error correction by teacher or some methods of testing) can also cause anxiety.

In her research (1988), Horwitz explains some unreal beliefs of learners; for example, some language learners think that pronunciation is the most important aspect of the language learning process, for this reason; they try to speak with an excellent accent (but that is not possible all the time), or some learners believe that two years is enough time for fluency in the foreign language and when they are not fluent enough after two years, they feel bad. In other words, when beliefs and reality do not meet; again, it results in anxiety.

The role of the teacher is also very important as it can be either facilitating or debilitating for the learners. “With an authoritarian, uncompromising teacher, students feel isolation and a loss of control, which creates separation in the classroom while intensifying language anxiety...” (Turula, 2002: 33) Language teachers should be friendly, helpful and sympathetic rather than being an authority figure in the classroom. Turula also suggests that; “with a teacher who creates a friendly learning environment of caring and sharing with a sense of direction and fun, students’ feelings of anxiety are dispelled.” (Turula, 2002:33) Because the more students feel anxious, the more they need someone who cares for them.

And for intimidating teacher attitudes, Young (1991:428) makes this explanation:

Instructors who believe their role is to correct students constantly when they make any error, who feel that they cannot have students working in pairs because the class may get out of control, who believe that the teacher should be doing most of the talking and teaching, and who think their role is more like a drill sergeant's than a facilitator's may be contributing to learner language anxiety.

So, language teachers should be more alert and sympathetic towards their students all the time, as it is vital to overcome language anxiety. Most of the time, anxious students feel self-conscious in the classroom atmosphere, so language teachers should take special care of anxious students, and should make them join in the appealing language tasks.

As the last source, language tests can be said. For example, if a language teacher has a communicative approach while teaching, but then if s/he gives a grammar test, this leads to not only complaints but also anxiety among the students.

In a research done by Price (1991:101-107), subjects were asked to say the sources of anxiety in language learning process. They all spoke about their fears of being laughed at by others, when they have to speak in foreign language. They were afraid of making errors in pronunciation. And a third source of anxiety for them was the fear of not being able to communicate effectively.

After their research on the factors associated with language anxiety, Bailey et al. (1999: 227) concluded that:

The students with the highest levels of foreign language anxiety tended to have at least one of these characteristics: older, high academic achievers, had never visited a foreign country, had not taken any high school foreign language courses, had low expectations of their overall average for their current language course, had a negative perception of their scholastic competence, or had a negative perception of their self-worth.

In their research, they stress the importance of students’ beliefs about the language learning process. According to them, students’ expectations of their achievement in foreign language courses are the biggest predictors of foreign language anxiety. If students do not expect to be successful in the language course, if they maintain their negative feelings about the language course, then it is possible that they are anxious learners.

According to MacIntyre (1995:94) “affective variables are considered as mere side effects of having difficulties in coding the native language.” Sparks and Ganschow (1991), in their article which was written as a response to MacIntyre’s ideas, suggest an alternative to affective explanations for FL learning failure and add another dimension to the role of language aptitude:

"In our view, low motivation, poor attitude, or high levels of anxiety are, most likely, a manifestation of deficiencies in the efficient control of one's native language, though they are obviously correlated with difficulty in FL learning." (Sparks &Ganschow, 1991:10)

Sparks and Ganschow propose to relate L1 problems of students with learning difficulties to FL learning by proposing that students with FL difficulties may have underlying linguistic coding deficits which interfere with their ability to learn a FL. That’s to say; some individuals have difficulty learning their native

language in oral and/or written form and that this difficulty is likely to affect ability to learn a FL. (Sparks and Ganschow, 1991: 3-16)

Although they acknowledge that motivation, attitude, and anxiety can hinder learning, they also suggest that poor attitudes and high anxiety are more likely to arise from difficulties inherent in the task itself.

Sparks and Ganschow also propose that (1991:235), “FL learning difficulties are likely to be based in native language learning and that facility with one's language "codes" (phonological/orthographic, syntactic, and semantic) is likely to play an important causal role in learning a FL.”

In their 1991 paper and related ones, Sparks and Ganschow call this position as the ‘Linguistic Coding Deficit Hypothesis’ (LCDH).

In another research, (1995:236) Sparks and Ganschow claim that “the ability to use and understand language, rather than affective variables, is the more important causal factor in FL learning in classroom settings”.

Sparks and Ganschow looked from a different aspect to the subject, they (in Ganschow et al., 1994:43) have suggested that “affective differences, such as anxiety, might be the consequence of FL learning problems, which themselves bear a strong relationship to a student's problems in his/her native language.”

Contrary to MacIntyre and Gardner (1991), these researchers argued that foreign language anxiety does not play a causal role in individual differences in foreign language learning but is merely the consequence of differences in native language skills. As a response to MacIntyre, they advocate that “one must look beyond anxiety for the factors which bring about the anxiety. One cannot discuss anxiety without inferring a cause.” In their view, the cause of FL anxiety is usually related to listening, reading, writing, or speaking a language.

According to Linguistic Coding Deficit Hypothesis (LCDH), “it seems clear that specific difficulty at the phoneme level can cause difficulties with the acquisition of oral and written language in both the native and the foreign language.” (Ganschow and Sparks, 1991:9)

According to their hypothesis, it is easy to conceptualize foreign language anxiety as a result of poor language learning ability. A student does poorly in language learning and consequently feels anxious. Conversely, a student might do

well in the class and feel very confident. The challenge is to determine the extent to which anxiety is a cause rather than a result of poor language learning.

MacIntyre (1995) and Horwitz (2000) have responded to the LCDH arguing for the existence of language anxiety independent of first or general language learning disabilities. They insist that anxiety is a well-known source of interference in all kinds of learning environment, so it cannot be taken as a different variable in language learning environment. They also insist that, the number of people who suffer from language anxiety is far more than the number of people with decoding disabilities. And, many successful language learners may also experience language anxiety. Moreover, they observe that language learning requires much more than sound-symbol correspondences and they conclude that LCDH is a simplified view of language learning.

That’s to say; while Sparks and Ganschow assert that there is a link between foreign language learning anxiety and native language learning disabilities; MacIntyre and Horwitz claim that there is no relationship between native language learning disabilities and foreign language learning problems.

According to Price (1991:105-107), there are certain causes of anxiety; such as difficulty of language courses, speaker’s beliefs, stressful classroom experience. And Foss and Reitzel (1988) claim that, sometimes the language learners may rebel against the second language culture. They may not want to learn the language because of the negative feelings they have against the culture. Dodd (1982) -in Foss and Reitzel, (1988:443) - suggests that:

Foreigners sometimes may fight or flee the second culture during the transitional stage of culture shock. For instance, students may choose not to associate with native speakers or use the second language as a way of "fighting" against the second culture. They are not motivated to use the language because they do not view the second culture in a positive light. Others may cope with culture shock by withdrawing ("fleeing") from contact with the second culture. The motivation to learn and use the second language, then, depends on students' perceptions of their abilities in the second language and their feelings toward the second culture.

Foreign language courses may be a bit more difficult than other courses for some individuals, thus eliciting higher anxiety than other courses. Speaker’s beliefs

also affect the language learning process, generally in a negative way, which can be seen as the potential sources of anxiety.

Language learning atmosphere has also a vital role on the effectiveness of learning process. It is clear from the researches that, if students feel relaxed in the language classroom, they can more easily concentrate on the learning process. Then, all the sources that maintain anxiety should be expelled from the language learning process. At this point, teachers have a vital role.

2.4 Types of Anxiety

Even if there are some beliefs which deal with language anxiety as distinct from other types of anxieties, but in fact; according to some researchers, language anxiety is connected to other types of anxieties, moreover, it stems from them.

“Even if one views language anxiety as being a unique form of anxiety, specific to second language contexts, it is still instructive to explore the links between it and the rest of the anxiety literature.” (MacIntyre,1999:28 )

According to McIntyre (1999), to replace language anxiety in the broader context of research on anxiety, literature distinguishes between three broad perspectives on the nature of anxiety.

These perspectives can be defined as trait, situation-specific and state anxiety. Two main types of anxiety such as; the trait anxiety and the state anxiety have been investigated in a number of different areas, including the language learning context.

Gaudry and Spielberger define these anxiety types in their books:

State anxiety, like kinetic energy, refers to an empirical process or reaction taking place at a particular moment in time and at a given level of intensity. Trait anxiety, like potential energy, indicates differences in the strength of a latent disposition to manifest a certain type of reaction. (Gaudry and

Spielberger, 1971:15)

“Trait anxiety is, by definition, a feature of an individual’s personality and therefore is both stable over time and applicable to a wide range of situations.” (MacIntyre, 1999:28)

Spielberger (1971) also defines trait anxiety as a probability of being anxious in any situation. According to MacIntyre, people having a high level of trait anxiety are more likely to be nervous most of the time, they lack emotional stability. But someone who has got a low trait anxiety is emotionally stable, a usually calm and relaxed person.

Trait anxiety, as understood from its name, is like a personal construct and some people are generally anxious about many things. On the other hand; state anxiety is evoked whenever a person perceives stimulus or situation as harmful, dangerous or threatening to him.

“State anxiety, refers to the moment-to-moment experience of anxiety; it’s the transient emotional state of feeling nervous that can fluctuate over time and vary in intensity.” (MacIntyre, 1999:28)

State anxiety is essentially the same experience whether it is caused by test taking, meeting with the fiancé’s parents, or trying to communicate in a language classroom. “State anxiety has an effect on emotions, cognition and behavior.” (MacIntyre, 1999:28) “State anxiety is evoked by a particular set of temporary circumstances.” (Allwright and Bailey, 1991:173)

Then, it is clear that; state anxiety is evoked by a certain stressful circumstance, such as test-taking, dating someone for the first time and speaking in the target language in front of the classroom.

“On one hand, state anxiety is an immediate, transitory emotional experience with immediate cognitive effects. On the other hand, trait anxiety is a stable predisposition to become anxious in a wide range of situations.” (Spielberger, 1983 in MacIntyre, 1995:93)

It should be emphasized that state anxiety is the reaction, and trait anxiety represents the tendency to react in an anxious manner. According to MacIntyre (1995), the negative effects of anxiety can only be associated with the immediate anxiety experience and therefore refer to state anxiety arousal.

For example, Gaudry and Spielberger (1971) think that a student with low trait anxiety may be quite calm in most testing situations, but s/he may react with intense anxiety when faced with a Mathematics test because of a failure in his/her history. So, trait and state anxieties are associated in a way.

If we compare trait and state anxiety we can conclude that; trait anxiety refers to constant personality differences in the tendency of anxiety, however; state anxiety is momentary and it relates to some particular event or a situation.

“Situation-specific anxiety is like trait anxiety, except applied to a single context or situation only…thus it is stable over time but not necessarily consistent across situations.” (MacIntyre, 1999:28)

As for MacIntyre (1999), stage fright, test anxiety, math anxiety and language anxiety can be given as examples of situation-specific anxiety. All of these examples have a different context, each situation is different. A person may feel nervous for one of them not for the others.

Applied to language learning, we can see that a person with a high level of language anxiety will experience state anxiety frequently; a person with a low level of language anxiety will not experience state anxiety very often in the second language context. (MacIntyre, 1999:29)

Then, it should be emphasized that “the negative effects of anxiety can only be associated with the immediate anxiety experience and therefore refer to state anxiety arousal.” (MacIntyre, 1995:93)

Macintyre also advocates this hypothesis with these sentences:

We see that when state anxiety is provoked, performance on second language tasks suffers, but no performance deficits are observed when learners are not experiencing anxiety. Thus, active interference seems to arise from state anxiety, and that interference can occur at any stage of the learning process. (1995:93)

From all these perspectives, it appears that language anxiety fits the general criterion for an anxiety which by definition is an unrealistic reaction to a particular situation.

2.5 Anxiety and Foreign Language Learning

There has always been a debate among scholars on whether language anxiety is just another type or a branch of state anxiety. Language learning researchers are still investigating whether the nervousness and worry experienced by some language

learners is actually “language anxiety” or a manifestation of one or both of the two most common types of anxiety: trait anxiety and state anxiety.

Language anxiety is a pervasive and prominent force in the language learning process, and any theoretical model seeks to understand language learning must consider its effects. MacIntyre posits that language anxiety can negatively or positively affect FL learning and that there is an anxiety specific to FL learning. (1995: 92-94)

To explain and try to understand what language anxiety is there are two different approaches:

(1) Language anxiety may be viewed as a manifestation of other more general types of anxiety. For example, test-anxious people may feel anxious when learning a language... or (2) Language anxiety may be seen as a distinctive form of anxiety expressed in response to language learning. (Horwitz and Cope, 1991:1)

After examining the role of related types of anxiety in language learning- specifically communication apprehension, fear or negative evaluation, and test anxiety- Horwitz and Cope (1991, 26) conclude that “language anxiety is a type of anxiety unique to second-language learning; that’s, they conceive of language anxiety as something more than the sum of its component parts.”

On the other hand, MacIntyre and Gardner, tested Horwitz and Cope’s three-part anxiety model, and found that all three components (communication apprehension, fear or negative evaluation, and test anxiety) of their model have an important role in language anxiety. That’s to say; they support that language anxiety is a composition of other types of anxiety. (Horwitz and Cope, 1991: 26)

Horwitz and associates (1986) regard language anxiety as “a distinct complex of self-perceptions, beliefs, feelings and behaviors related to classroom language learning arising from the uniqueness of the language learning process.”

According to a research, done by MacIntyre and Gardner (1991) to identify the types of anxiety and the relation between them, among the largest set of anxiety variables there were three clear anxiety clusters; these are General Anxiety, State Anxiety and French anxiety, this last factor was named as language anxiety.

This study showed that there could be no correlation among the anxiety factors. Thus, it is possible to separate language anxiety from other forms of anxiety.

(MacIntyre, 1999:30) MacIntyre defines language anxiety like that; “language anxiety is a situation-specific form of anxiety that does not appear to bear a strong relation to other forms of anxiety.” (MacIntyre, 1999:30)

It seems likely that no matter which language teaching method is used, speaking the language in front of an entire class is a difficult task for a large number of students. This means that predicting the students who have language anxiety is a difficult task, so language teachers have to pay special attention on students’ emotions.

According to Horwitz and Cope (1991), when anxiety is limited to the language learning situation only, it falls into the category of specific anxiety reactions; psychologists use the term specific anxiety reaction to differentiate people who are generally anxious in a variety of situations from those who are anxious only in specific situations.

At the earliest stages of language learning, a student will encounter many difficulties in learning, comprehension, grammar, and other areas. If that student becomes anxious about these experiences, if s/he feels uncomfortable making mistakes, then state anxiety occurs. After experiencing repeated occurrences of state anxiety, the student comes to associate anxiety arousal with the second language. When this happens, the student expects to be anxious in second language contexts; this is the genesis of language anxiety. (MacIntyre, 1999:30)

According to these definitions, it is understood that, language anxiety is a situation specific anxiety which comes into play when it is time to speak or fulfill a challenging task in foreign language classes. It is an aspect of state anxiety and after experienced for once, students are expected to live it again.

“...the phenomenon of language classroom anxiety was so widespread as to be an identifiable type of state anxiety... so anxiety, especially state anxiety is an acknowledged feature of language learning whether as cause, effect or both.” (Allwright and Bailey, 1991: 173)

MacIntyre’s model also describes how language anxiety differs from the other types of anxiety. And it is clear from these definitions that, language anxiety occurs when a student associates anxiety with the second language. Students who are very successful in other school subjects may find language-learning to be very

difficult and anxiety provoking. This can be caused either from their personal disbeliefs about language acquisition or their specific reactions to language learning process. So, language anxiety is unique to language learning process.

“Many people claim to have a mental block against learning a foreign language, although these same people may be good learners in other situations, strongly motivated, and have a sincere liking for speakers of the target language.” (Horwitz and Cope, 1991:27) “The anxiety experienced by language learners is said to be unique to the language learning process and completely distinct from other forms of anxiety.” (Horwitz et al., 1986; MacIntyre, 1999)

According to Allwright and Bailey (1991: 172-176), language learning provokes anxiety as it deprives learners of the means of behaving naturally. The learners may feel uncomfortable when they forced to use the language they are learning, because they may feel that they are representing themselves badly, showing only some of their personality, only some of their real intelligence, which makes them anxious.

With second language learners, there are the feelings of incompetence about grasping the language perfectly and about the inability to present oneself in a way consistent with one's self-image. In both forms of anxiety, negative self-perceptions set in motion a perpetuating cycle of negative evaluations that may persist despite the evaluations from others to the contrary. (Foss and Reitzel, 1988:439-440)

As for Allwright and Bailey, language classes can provoke anxiety more than others. For example, in Mathematics you may get the answer wrong, but anyway you can be reasonably sure of saying the numbers correctly, but in language classes, even if you get the answer right, you might still make an almost infinite numbers of mistakes in what you say and how you say it. In these circumstances, language learning can represent a threat to a learner’s sense of identity.

“...the probability of being wrong in some way of other is vastly greater in language learning than in other subjects. And being ‘wrong’, given many language teachers’ views on how important it is to correct errors...more or less mild form of public humiliation.” (Allwright and Bailey, 1991: 175)

People do not feel relaxed in indefinite situations, and language learning process is an indefinite, infinite process. Learning a foreign language is a long and

complex way, in which learners feel unsure for most of the time as there is always a risk to make a mistake. And, these feelings of uncertainity result in anxiety.

When we wear clothing that is unbecoming or have a "bad hair day," we feel uncomfortable because not only do we not feel like ourselves, we feel that we are presenting a less positive version of ourselves to the world than we normally do. In an analogous way, few people can appear equally intelligent, sensitive, witty, and so on when speaking a second language as when speaking their first; this disparity between how we see ourselves and how we think others see us has been my consistent explanation for language learners' anxieties. (Horwitz, 2000:258)

As it has been seen anxiety is a very complex term and it relates to foreign language learning. Since 1970’s language learning anxiety has been studied. According to the results of these studies it has been difficult to show the exact effects of anxiety on foreign language learning. The reason for this is that anxiety is difficult to measure and a problem can cause in defining, manipulating and quantifying it. However the findings of the earliest studies have all suggested that the level of anxiety in second language learning must be reduced.

2.5.1 Facilitating and Debilitating Anxiety

In learning environment, some amount of anxiety can be seen as helpful for the learning process, but if this amount is somewhat high; then, this can obstruct learning. Some researchers claim that anxiety doesn’t have a negative effect on language learning, but may be of facilitating and as well as of debilitating nature. “Knowing that success is not guaranteed, but that making a real effort might make all the difference between success and failure, we may do better precisely because our anxiety spurred us upon.” (Allwright and Bailey, 1991: 172)

After scanning all the literature on the effects of anxiety on language learning environment, Scovel (1991) proposed two different kinds of anxiety experienced in the foreign language learning process; debilitating and facilitating anxieties.

Anxiety-the distress evoked by life’s pressures-is perhaps the emotion with the greatest weight of scientific evidence connecting it to the onset of sickness and course of recovery. When anxiety helps us prepare to deal with some danger (a presumed utility evolution), then it has served us well. But in modern life anxiety is more often out of proportion and out of place- distress comes in the face of situations that we must live with or that are conjured by

the mind, not real dangers we need to confront. Repeated bouts of anxiety signal high levels of stress. (Goleman, 1995: 198)

If anxiety in language learning environment creates some competitiveness among students, and help them study more to out-perform other learners, to do better in tests and to have teacher’s approval, then this kind of anxiety can be evaluated as ‘facilitating’, because it motivates students and has a positive effect on learning. But, conversely; the anxiety may also lead learners to withdraw from the learning situation; sometimes it may detain students from learning. Then, this kind of anxiety can be evaluated as ‘debilitating’, as it obstructs learning situation.

Facilitating anxiety motivates learner to “fight” the new learning task; it gears the learner emotionally for approach behavior. Debilitating anxiety, in contrast, motivates the learner to “flee” the new learning task; it stimulates the individual emotionally to adopt avoidance behavior. (Scovel, 1991: 22) “It is with facilitating and debilitating anxiety in the normal learner- each working in tandem, serving simultaneously to motivate and to warn, as the individual gropes to learn an ever-changing sequence of new facts about the environment.” (Scovel, 1991:22)

According to Young (1991: 58), “facilitating anxiety is an increase in drive level which results in improved performance while debilitating anxiety is an increase in arousal or drive level which leads to poor performance.”

“Facilitating anxiety is considered to be an asset to performance and showed the predicted positive effects...debilitating anxiety, which is the more common interpretation of ‘anxiety’, is considered to be detrimental to performance…” (MacIntyre and Gardner, 1991: 41)

In other words; anxiety is not always a threatening subject for the learning process, but if language students experience debilitating anxiety- the anxiety that impedes successful learning-, teachers and parents must be alert.

2.5.2 How Does Language Anxiety Affect Language Learning and Students’ Performance

As it has been known, there are a lot of affective factors which influence language learning process in a positive or negative way. Among these factors,

anxiety is the most prominent one for language learning/teaching process, as it affects learning process in a negative and inhibiting way. Language anxiety ranks high among factors influencing language learning, whatever the learning setting (Oxford, 1991), and has become central to any examination of factors contributing to the learning process and learner achievement.

The effects of anxiety can extend beyond the classroom. Just as math anxiety serves as a critical job filter, channeling some women and some members of other minority groups away from high-paying, high demand math and engineering careers, foreign language anxiety, too, may play a role in students' selections of courses, majors, and ultimately, careers. Foreign language anxiety may also be a factor in student objections to foreign language requirements. (Horwitz and Cope, 1986:131)

As it is understood from this quotation, foreign language anxiety plays a vital role even in career selection of students. They try to prefer careers which do not require foreign language knowledge, even if they are not paid much. These figures make it clear that, foreign language anxiety is getting more and more dangerous, and some precautions must be taken immediately.

Since the mid 1960s, there have been different researches on the possibility that anxiety interferes with second language learning and performance; however, documentation of that relationship came much later.

Nearly two decades ago, Scovel (1978) reviewed the available literature of the time to show the relationship between language anxiety and performance.

There were studies which found the negative relationship between anxiety and second language achievement, but several studies found no relationship, and positive relationships between anxiety and second language achievement were also identified. (Chastain, 1975; Kleinmann, 1977).

After his research, Scovel concluded that, as language researchers used different anxiety measures in their researches, they found different types of relationships. He also suggested that language researchers should be specific on the type of anxiety they are measuring.

Scovel’s suggestions worked, and Horwitz and Cope (1986) took the literature a step further by proposing “a situation-specific anxiety construct which