WRITTEN OR ORAL TEACHER FEEDBACK: WHICH ONE FACILITATES IDEA DEVELOPMENT IN WRITING CLASSES?

SEVDE YAZICI

M.A. THESIS

DEPARTMENT OF FOREIGN LANGUAGE INSTRUCTION

GAZI UNIVERSITY

INSTITUTE OF EDUCATIONAL SCIENCES

i

TELİF HAKKI ve TEZ FOTOKOPİ İZİN FORMU

Bu tezin tüm hakları saklıdır. Kaynak göstermek koşuluyla tezin teslim tarihinden itibaren 12 ay sonra tezden fotokopi çekilebilir.

YAZARIN Adı : Sevde Soyadı : YAZICI Bölümü : İngilizce Öğretmenliği İmza : Teslim tarihi : 06. 05. 2015 TEZİN

Türkçe Adı : Yazılı ve Sözlü Geri Bildirim: Hangisi, Yabancı Dilde Yazma Derslerinde Öğrencilerin Fikirlerini Geliştirmesini Kolaylaştırmaktadır?

İngilizce Adı : Written or Oral Feedback: Which One Facilitates Idea Development in Writing Classes?

ETİK İLKELERE UYGUNLUK BEYANI

Tez yazma sürecinde bilimsel ve etik ilkelere uyduğumu, yararlandığım tüm kaynakları kaynak gösterme ilkelerine uygun olarak kaynakçada belirttiğimi ve bu bölümler dışındaki tüm ifadelerin şahsıma ait olduğunu beyan ederim.

Yazar Adı Soyadı: Sevde YAZICI İmza: ………

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

There are several people who deserve a lot of credit for their various contributions to the realization of this thesis.

First and foremost, I would like to express my deepest gratitude and appreciation to my supervisor, Assoc. Prof. Dr. Hacer Hande Uysal, for her helpful suggestions, guidance and motivation during the preparation of this study.

I am also grateful to my colleagues and all my students who have provided me with their support and valuable help during the collection of data. I am also indebted to Nilden Tutalar, who has helped me analyze the data quantitatively.

My grateful thanks are also extended to Mediha Toraman, who witnessed every stage of this experience and provided her personal and professional help whenever I needed, to Merve Çavuş, Merve Yüksel, and Seda Sevim, who supported me and provided their valuable contributions to the transcriptions of the student interviews, and to Büşra Delen and Nazan Cakcak for their support and encouragement in every phase of this thesis.

Finally and most importantly, my heart-felt thanks go to my husband, Engin Yazıcı, for his love and endless trust in me and his patience and support along with all the sacrifices he has made throughout the process. Also, I thank my family and my in-laws for believing that I will be successful in every phase of my life and encouraging me to achieve my goals.

v

WRITTEN OR ORAL TEACHER FEEDBACK: WHICH ONE

FACILITATES IDEA DEVELOPMENT IN WRITING CLASSES?

M.A Thesis

Sevde YAZICI

GAZİ UNIVERSITY

INSTITUTE OF EDUCATIONAL SCIENCES

October, 2015

ABSTRACT

This study aimed to find out and analyze to what extent EFL students with Pre-Intermediate level of proficiency at Middle East Technical University Preparatory School can understand and use written and oral teacher feedback on the content of their writing assignment. To achieve this aim, five main questions were attempted to be answered. The first question was whether or not there is a significant difference between the first and final drafts of the students who got written facilitative feedback and the ones who got oral feedback through teacher-student conferencing in terms of the content of the paragraphs they wrote. The second question was whether or not one of these two feedback types is more effective than the other in leading the students to develop the ideas in their paragraphs. The third question was whether or not the students’ attitudes towards written facilitative feedback and teacher-student conferencing show a significant difference in terms of their utilization of feedback. The fourth question was whether or not the students’ utilization of feedback matches their teacher’s intentions in both types of feedback. The final question was which factors affect the effectiveness of communication of feedback between the teacher and the students. Data was collected from 16 students by asking each to write two drafts of a paragraph and to have two open-ended interviews with the researcher. In the data analysis part, the first and second drafts of each student’s paragraph were examined, and the frequencies of student understanding of teacher feedback and successful revision were identified. Moreover, an inductive analysis of the two transcribed open-ended interviews was done to find out about the factors that affect student understanding and revision success. The results revealed that the students who got written feedback were able to improve the ideas in their paragraphs more frequently than the ones who got oral feedback although there was not a significant difference between the grades they got for their 2nd drafts in terms of the content of their written work. Furthermore, it

was seen that rather than formal characteristics of teacher feedback, students’ difficulty in elaborating on ideas, their overestimation of quality of their written work, their beliefs about an effective paragraph, their such concerns as exceeding word limits and making mistakes and lack of content knowledge influenced the students’ revision processes and the success of a second draft.

Key Words : Written feedback, oral feedback, effectiveness of revision, L2 writing, responding to feedback

Page Number : 138

vii

YAZILI VE SÖZLÜ GERİ BİLDİRİM: HANGİSİ, YABANCI DİLDE

YAZMA DERSLERİNDE ÖĞRENCİLERİN FİKİRLERİNİ

GELİŞTİRMESİNİ KOLAYLAŞTIRMAKTADIR?

Yüksek Lisans Tezi

Sevde YAZICI

GAZİ ÜNİVERSİTESİ

EĞİTİM BİLİMLERİ ENSTİTÜSÜ

Ekim, 2015

ÖZ

Bu çalışmanın amacı, Orta Doğu Teknik Üniversitesi Hazırlık Okulu orta seviye öncesi öğrencilerinin, yazdıkları paragrafların içeriği üzerine öğretmen tarafından verilen yazılı ve sözlü dönütü ne kadar anladıklarını ve kullanabildiklerini ortaya çıkarmak ve incelemektir. Bu amacı gerçekleştirmek için beş temel soruya cevap verilmeye çalışılmıştır. İlk soru, yazdıkları paragrafların içeriğine ilişkin yazılı geri bildirim alan öğrencilerin ilk ve son taslaklarıyla, öğretmen-öğrenci konferanslarıyla sözlü geri bildirim alanların ilk ve son taslakları arasında anlamlı bir fark olup olmadığıdır. İkinci soru, öğrencileri paragraflarındaki fikirleri geliştirmeleri açısından yönlendirmede, bu iki geri bildirim yönteminden birinin diğerinden daha etkili olup olmadığıdır. Üçüncü soru, öğrencilerin yazılı geri bildirime ve öğretmen-öğrenci konferansına olan tutumlarının anlamlı bir fark gösterip göstermediğidir. Dördüncü soru, her iki geri bildirim yönteminde de öğrencilerin geri bildirimden faydalanma şekillerinin öğretmenin beklentilerine uyup uymadığıdır. Son soru ise, öğretmen ve öğrenci arasındaki geri bildirim iletişiminin verimliliğini etkileyen etmenlerin neler olabileceğidir. Veriler, 16 öğrenciden, her birinden bir paragrafın iki taslağını yazmalarının ve araştırmacı ile iki açık uçlu görüşme yapmalarının istenmesiyle toplanmıştır. Veri analizi kısmında, her öğrenci paragrafının ilk ve son taslaklarının incelenmiş ve öğrencilerin öğretmen tarafından verilen geri bildirimi anlama ve iki taslaktaki başarılarının sıklığı belirlenmiştir. Ayrıca, öğrencilerin paragraflarında fikir geliştirmelerine yardımcı olmada hangi yöntemin daha etkili olduğunu belirlemek için, iki açık uçlu ve yazıya dökülmüş olan öğrenci - öğretmen görüşmesinin tümevarımsal analizi yapılmıştır. Sonuçlar, ikinci taslaklarının içeriği için aldıkları notlarda istatistiksel açıdan anlamlı bir fark gözlemlenmemesine rağmen, yazılı geri bildirim alan öğrencilerin sözlü geri bildirim alan öğrencilere kıyasla paragraflarında daha sık fikir üretebildiklerini

göstermiştir. Ayrıca, bulgular, öğrencilerin düzeltme yapma sürecini ve ikinci taslağın başarısını etkileyen faktörün öğretmen geri bildiriminin biçimsel özellikleri değil, öğrencilerin fikirlerini detaylandırmada yaşadıkları zorluk, yazdıkları paragrafları nitelik açısından gözlerinde büyütmeleri, iyi bir paragrafın özelliklerine yönelik (kuvvetle inanılan) düşünceleri, kelime sınırını aşma ve hata yapma gibi endişeleri ve konu hakkında yeterli bilgiye sahip olmamaları gibi faktörlerin olduğunu da göstermiştir.

Anahtar Kelimeler : Yazılı geri bildirim, sözlü geri bildirim, düzeltmede etkililik, ikinci dilde yazma, geri bildirime cevap verme

Sayfa Adedi : 138

ix

TABLE OF CONTENTS

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS ... iv

ABSTRACT ... v

ÖZ ... vii

TABLE OF CONTENTS ... ix

LIST OF TABLES ... ixii

LIST OF FIGURES ... ixv

LIST OF ABBREVIATIONS ... ixvi

CHAPTER I ... 1

INTRODUCTION ... 1

1.0. Presentation ... 1

1.1. Statement of the Problem ... 1

1.2. Objective of the Study ... 3

1.3. Significance of the Study ... 4

1.4. Assumptions ... 5

1.5. Limitations of the Study ... 5

1.6. Definitions of the Terms ... 6

CHAPTER II ... 9

REVIEW OF LITERATURE ... 9

2.0. Presentation ... 9

2.1. The Importance of Feedback ... 9

2.2. The Perception of Error Correction throughout the History ... 10

2.4. Studies that are for Error Correction Feedback ... 15

2.5. A Shift in the Focus of Teacher Feedback ... 16

2.5.1. The Tone of Teacher Feedback ... 18

2.5.2. Factors Affecting Students’ Utilization of Teacher

Feedback ... 20

2.5.2.1. Students’ Perception of Effective Feedback ... 20

2.5.2.2. The Focus of Teacher Feedback ... 21

2.5.2.3. Students’ Revision Habits as a Result of Teacher

Feedback ... 22

2.5.2.4. The Mode of Teacher Feedback ... 25

2.5.2.4.1. Advantages and Disadvantages of Written

Feedback ... 26

2.5.2.4.2. Advantages and Disadvantages of Oral

Feedback ... 29

CHAPTER III ... 35

METHODOLOGY ... 35

3.0. Presentation ... 35

3.1. The Rationale behind Using both Quantitative and Qualitative

Research Design ... 35

3.2. Research Design ... 37

3.3. The Setting ... 42

3.4. The Participants ... 44

3.5. Data Collection Instruments ... 45

3.5.1. Students’ Written Texts... 46

3.5.2. Open-Ended Interviews ... 46

3.5.3. Audiotapes ... 48

3.6. Data Collection Procedure ... 49

xi

CHAPTER IV ... 55

RESULTS ... 55

4.0. Presentation ... 55

4.1. Quantitative Findings ... 55

4.1.1. The First Research Question ... 55

4.1.1.1. Computing Normality for 1

stDraft Scores of Both

Groups ... 56

4.1.1.2. Wilcoxon Signed-Ranks Test Hypothesis ... 59

4.1.1.3. Computing Normality for Oral Feedback Group ... 60

4.1.2. The Second Research Question ... 61

4.1.2.1. Mann-Whitney U Test Hypothesis ... 62

4.1.2.2. Inter-Rater Reliability Analysis ... 63

4.1.2.2.1. Statistical Model ... 63

4.1.2.2.2. 1

stDraft Inter-Rater Reliability ... 64

4.1.2.2.3. 2

ndDraft Inter-Rater Reliability ... 65

4.1.3. The Third Research Question ... 66

4.1.3.1. Relationship between Understanding of Error

Feedback on the First Drafts of Paragraphs and Revision

Success ... 68

4.1.4. The Fourth Research Question ... 71

4.2. Qualitative Findings ... 72

4.2.1. Individual Stories ... 78

4.2.1.1. Difficulty in Elaborating on Ideas ... 80

4.2.1.2. Overestimation of Quality of Writing ... 83

4.2.1.3. Students’ Beliefs ... 86

4.2.1.4. Students’ Concerns ... 87

4.2.1.5. Lack of Content Knowledge ... 88

CONCLUSION AND SUGGESTIONS ... 91

5.0. Presentation ... 91

5.1. Summary of Findings in Relation to Research Questions ... 91

5.1.1. The First and the Second Research Questions ... 91

5.1.2. The Third Research Question ... 94

5.1.3. The Fourth Research Question ... 95

5.1.4. The Fifth Research Question ... 97

5.2. Implications for ELT ... 100

5.3. Implications for Further Research ... 103

REFERENCES ... 105

APPENDICES ... 121

APPENDIX 1. The Demographic Questionnaire ... 122

APPENDIX 2. The Consent Form ... 123

APPENDIX 3. Examples of Some of the Students’ 1

stDrafts ... 124

APPENDIX 4. Examples of Some of the Students’ 2

ndDrafts ... 127

APPENDIX 5. Examples of the Feedback Given to Some of the

Students ... 130

APPENDIX 6. The Questions Asked in the Second Interview ... 133

APPENDIX 7. METU EPE Writing Rubric ... 134

APPENDIX 8. Examples of the Completed Individual Coding

Sheets ... 135

xiii

LIST OF TABLES

Table 3.1. Yearly Achievement Grade in DBE ... 44

Table 3.2. Coding Sheet (for the First Draft ... 52

Table 3.3. Coding Sheet (for the Second Draft) ... 52

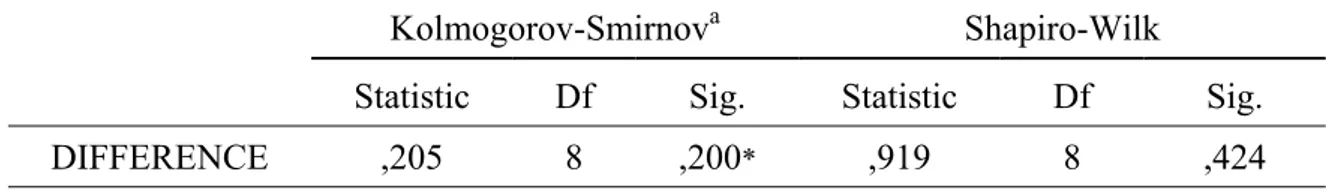

Table 4.1. Tests of Normality ... 56

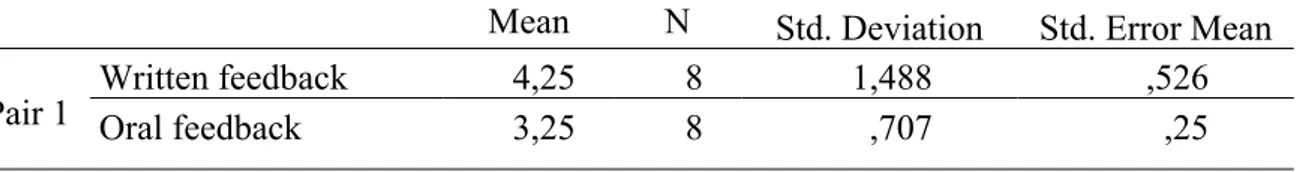

Table 4.2. Paired Samples Statistics ... 57

Table 4.3. Paired Samples T-Test ... 57

Table 4.4. Tests of Normality ... 58

Table 4.5. Descriptive Statistics ... 59

Table 4.6. Test Statistics ... 59

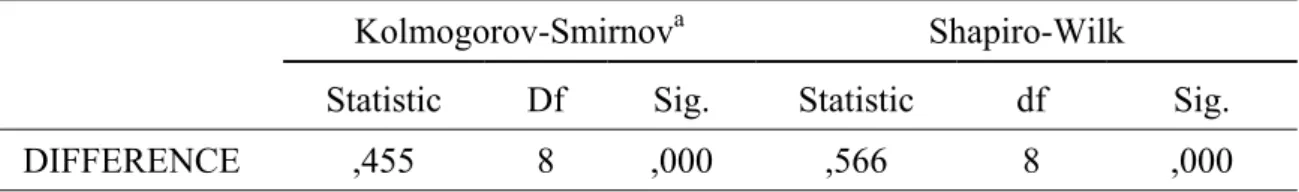

Table 4.7. Tests of Normality ... 60

Table 4.8. Paired Samples Statistics ... 60

Table 4.9. Paired Samples T-Test ... 61

Table 4.10. Tests of Normality ... 61

Table 4.11. Descriptive Statistics ... 62

Table 4.12. Test Statistics ... 63

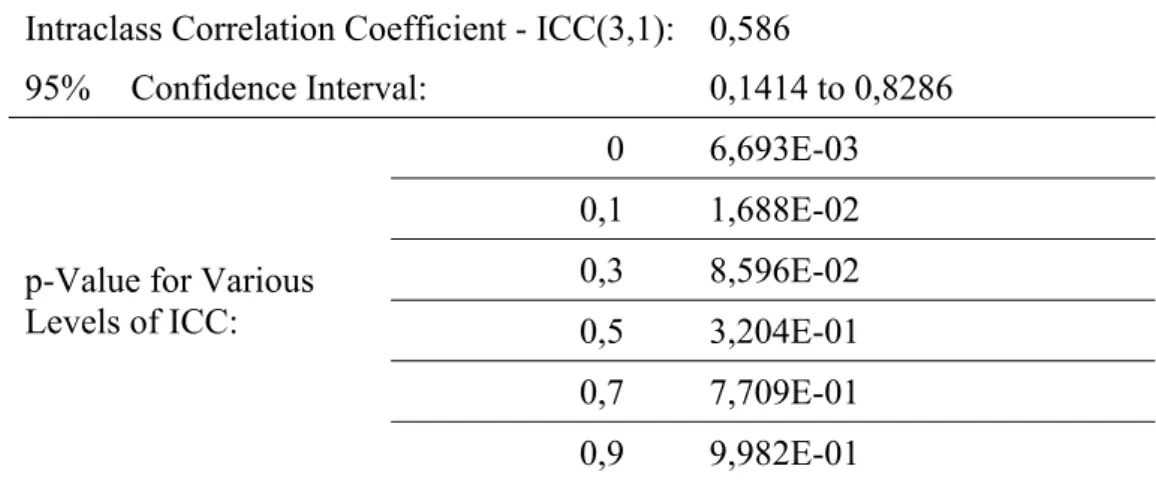

Table 4.13. Inter-Rater Reliability (1st Drafts) ... 65

Table 4.14. Inter-Rater Reliability (2nd Drafts) ... 65

Table 4.15. Students’ Initial Understanding of Teacher Feedback ... 67

Table 4.16. Relationship between Initial Understanding on 1st Drafts and Revision Success (Written) ... 69

Table 4.17. Relationship between Initial Understanding on 1st Drafts and Revision

Success (Oral) ... 70

Table 4.18. Relationship between Initial Understanding on 1st Drafts and Revision Success (Written + Oral) ... 70

Table 4.19. Students’ Feedback Preferences and 2nd Draft Grades ... 71

Table 4.20. Correlations ... 72

xv

LIST OF FIGURES

Figure 4.1. Grades given to the students’ first drafts by two raters ... 64

Figure 4.2. Group 1 students’ understanding of written feedback ... 66

Figure 4.3. Group 2 students’ understanding of oral feedback ... 67

LIST OF ABBREVIATIONS

DBE Department of Basic English METU Middle East Technical University EPE English Proficiency Exam

EFL English as a Foreign Language ESL English as a Second Language

L1 First Language

L2 Second Language

1

CHAPTER I

INTRODUCTION

1.0. PresentationIn this chapter, statement of the problem, the objective of the study, its significance, its assumptions and limitations together with definitions of the terms and the research questions will be presented.

1.1. Statement of the Problem

Recently, many foreign language students agree on the fact that learning to write is a difficult skill as they mainly suffer from the disadvantage of not getting immediate feedback from teachers, which is a significant point to be dealt with due to the fact that without sufficient feedback on their work, student improvement in writing may not place (Ferris, 1995; Harmer, 1983; Myles, 2002). Thus, teacher feedback is of utmost importance as an effective way to address and to communicate individual strengths and weaknesses directly to the student and as an opportunity to motivate and encourage students. In this sense, teachers are viewed as responsible for providing students with helpful feedback and scaffolding opportunities so that their students can develop strategies for self-correction and regulation.

However, some teachers may express concerns about how to provide commentary in ways that their students can effectively use to revise their texts and to learn for future texts because there is still no consensus on how teachers can best react to student errors in writing (Goldstein, 2004). Moreover, responding to student writing can be the most frustrating, difficult, and time-consuming part of teachers’ job because of the workload they have. At that point, some, for example, may prefer written corrective feedback, in

which the teacher provides the accurate linguistic structure for the student with explicit markings or notes above or near the error (Bitchener & Knoch, 2008). What the student is expected to do is just to copy the teacher’s corrections into the final draft, which implies minimal processing by the student according to Ellis (2008). William (2008) further claims that asking students to copy teacher corrections into the following drafts is a passive action as it does not teach students how to notice or correct errors on their own, and it causes students to focus more on surface errors than on the clarity of their ideas, which is another significant point to be included in teacher feedback.

As an alternative, indirect corrective feedback, in which the teacher shows the student errors in such ways as underlying to indicate the location of the error or using pre-determined error codes to help students understand the type of the error rather than directly correcting it, can also be chosen as a way of providing feedback (Sheen, 2007). In that case, the student is supposed to resolve and correct the problem on his/her own, which is believed to encourage problem solving and reflecting on linguistic forms (Bitchener and Knoch, 2008; Ellis, 2008).

Another option can be written feedback in the form of teacher comments written on student drafts that usually indicate problems and offer advice for improvement, which is more demanding for students as they need to incorporate information from the comments into the drafts of their papers. The main problem with that kind of feedback is believed to be about student comprehension since students may read the comments but not understand what they mean, or may understand them but not know how to respond to them to improve their writing skills (William, 2008).

Another effective choice has been called teacher-student conferencing, which gives learners the chance of having an open dialogue with teachers in a writing conference especially about the causes of the problems so that any potential miscommunication and misunderstanding can be prevented. Moreover, according to Williams (2008), during these sessions, teachers can gain a deeper understanding of student papers by asking them direct questions while students are expressing their ideas in writing more clearly and asking for clarification on any teacher comments on their writings. That can be made easier if students are provided with pre-conference sheets allowing them to decide which questions to ask their teacher and if the teacher has a list of comments and questions for each

3

individual student before the conference. This method is suggested to be more influential despite the extra class hours it requires (Hyland, 1998).

Keeping all aforementioned ideas in mind, it can be concluded that instructors and researchers have not yet reached a consensus on the most effective type of feedback to provide for students; however, as curricula at most preparatory schools of universities in Turkey require the inclusion of teaching writing in the English language syllabus, the issue of feedback or how to respond to student writing faces us as a critical issue to be dealt with.

1.2. Objective of the Study

The effect of a wide range of teacher feedback on students’ written work is not a new topic for researchers. The fact that curricula at most preparatory schools of universities in Turkey require the inclusion of writing in the English language syllabus and that teachers spend so much of their time and effort to comment on their students’ papers has also led to an increase in the focus on how to give effective feedback on students’ written work in order to help them improve their writing skills. Some research studies on error correction and second language acquisition show that there is individual variation in students’ ability to process teacher feedback and utilize it for their development as writers (Ferris, 2002). Thus, deciding on which method of writing feedback to use requires several considerations such as the number of students, the time available to teach and to respond, students’ proficiency levels, and a teacher’s responding style as the effect of teacher feedback on students’ written work could influence a student’s revision style. Therefore, as Ferris (2002) claims, it is not possible and appropriate to apply the same feedback strategies to all student groups and for all situations. Under these circumstances, one of the main problems is that although curricula at most preparatory schools of universities in Turkey necessitate the inclusion of writing skill in the English language course syllabus, detailed descriptions of how teachers should give feedback on students’ written work are limited in number. Therefore, the aim of the current research is to explore the effects of written versus oral teacher feedback on student writing in writing classes at the preparatory school of a Turkish University. In order to get a broader view, students’ attitudes toward two types of feedback, written facilitative feedback (Erskine, 2009) and oral feedback through teacher-student conferencing, and teacher-students’ strategies for handling feedback after getting back their

written work are also studied so that the effect of each feedback type on the quality of students’ final work could be determined. In other words, the present study aims to investigate how effectively a teacher’s intentions are communicated to the students through written and oral feedback, and the impact the effectiveness of each communication has on the quality of the students’ final drafts in terms of the content of their written work. This thesis, which is based on a study conducted in the Department of Basic English at Middle East Technical University with an EFL teacher and her Pre-Intermediate-level students, specifically seeks to address 5 main research questions stated below:

1. Is there a significant difference between the first and final drafts of paragraphs written by the students who get written feedback and oral feedback in terms of the content of their written work?

2. Is one of these two feedback types (written vs. oral) more effective than the other in leading the students to develop ideas in their written work?

3. Does the students’ utilization of written or oral feedback match their teacher’s intentions?

4. Do the students’ attitudes towards written and oral feedback show a significant difference in terms of their utilization of feedback?

5. What are the main factors that affect the effectiveness of communication of feedback between the teacher and the students?

1.3. Significance of the Study

As the study mainly aims at investigating how Pre-Intermediate level Department of Basic English (DBE) students of METU, who learn English in an EFL context, develop their writing skills based on their teacher’s written and oral feedback in their written work, it is likely to offer implications for instructional practices in EFL writing classes. Although the research is conducted with the participants from only one Turkish university, METU, the results can be applied to some other Turkish universities as curricula at most preparatory schools of universities in Turkey necessitate the inclusion of writing skill in the English language course syllabus. Moreover, findings in the study can function as the starting point for further research on how to foster better communication of teacher feedback between the teacher and the students in order to help improve EFL students’ writing skills because otherwise, as Ferris (2002) stated, if students do not understand their teacher’s feedback

5

when they focus on it or do not know how to respond to it and apply it to their writing, the teacher’s attempts will be just in vain. Although many writing teachers agree that teacher-student conferences whether to talk about ideas, organization, or errors are more effective than handwritten comments or corrections (Zamel, 1985) as an opportunity to clarify vague points and negotiate, unfortunately, there is very little research on these individual conferences with L2 students. Thus, this study can help gain more insight on giving effective feedback to correct errors by exploring students’ initial understandings of the teacher’s written and oral comments on their paragraphs and make a comparison between written and oral teacher feedback. Furthermore, it may help improve teachers’ assessment practices in the area of writing and help contribute to the current gaps in research because the evidence on the question of whether and how students respond to teacher feedback is quite limited (Ferris, 2012).

1.4. Assumptions

In this study, the sample group is believed to have all the features and abilities of the whole population, the Pre-Intermediate level students of METU, the Department of Basic English.

It is also assumed that students will respond naturally to the writing instruction that is given in both groups.

The time allotted for the research is assumed to be sufficient.

1.5. Limitations of the Study

The fact that the instructor is also the researcher may have influenced the analysis of the data and affected the neutrality of the results. Clearly, further analyses examining variations across instructors would be helpful.

The sample is not representative of a wider population as this study is limited to the Pre-Intermediate level students of the Department of Basic English at METU. Thus, the findings from this one study alone cannot be generalized to other populations or settings. It would be interesting to see whether repetition of this study with a larger and more representative sample of comparable university students would yield similar findings in the future.

This research is limited to the information and findings of the spring semester of the 2013-2014 academic year.

The study utilizes a single study research design; thus, its findings are limited to the data collection instrument employed by the researcher.

Since language learning and development can be an individual-based process, students’ English proficiency may vary even in the same level of language classroom.

Although students’ written work can be assessed depending on both their global errors (content and organization) and local errors (language and mechanics such as spelling and punctuation), in this study, only ‘content’ is taken into account as an aspect to be worked on since the time allotted for this study is limited, and the inclusion of all aspects requires a longer period of time and a more extensive and comprehensive study.

1.6. Definitions of the Terms

Effectiveness of communication: the extent to which the teacher’s intentions are understood by the students.

Global errors: The errors students make in the content, organization, or style of their written work (Erskine, 2009) and that interfere with the comprehensibility of their texts (Ferris, 2002).

Indirect feedback: When a teacher shows that a student has made a mistake but leaves it to the student to understand what is wrong and correct it, which encourages greater cognitive engagement, reflection, guided learning, and problem solving (Ferris, 2002). Local errors: The errors students make in the form, language, or mechanics of their written work (punctuation, spelling and so on) (Erskine, 2009).

Students’ utilization of feedback: a student’s interpretation of the feedback and his/her effort to make revisions in response to teacher feedback.

Teacher-student conferencing: A type of oral feedback in which students can enter into an open dialogue with instructors in a writing conference, which fosters two-way communication (Kramer-Simpson, 2012).

7

Written facilitative feedback: A type of feedback that offers praise, asks questions, guides, revision, explains rules of grammar and style, or adds additional sources (Erskine, 2009).

9

CHAPTER II

REVIEW OF LITERATURE

2.0. Presentation

The focus of this section is the pertinent literature on the present study. First, the importance of feedback is emphasized. The next focus is on the perception of error correction throughout the history, which is covered in detail depending on a number of studies that are against and for error correction. The last part of the section is on the shift in the focus of teacher feedback, which is explained in such categories as the mode and the tone of teacher feedback, students’ perceptions of teacher feedback, and the reasons why some students prefer written feedback while some others prefer oral feedback.

2.1. The Importance of Feedback

Recently, among foreign language students, there has been an agreement about the fact that learning to write is a challenging skill as they generally experience the disadvantage of not getting effective and sufficient feedback from teachers. This is an important issue to be dealt with as without helpful feedback on their work, it is not possible and realistic to expect improvement in students’ writing performance (Ferris, 1995; Harmer, 1983; Myles, 2002). Therefore, feedback is of utmost importance as an effective way to address and communicate individual strengths and weaknesses directly to the student concerned and as an opportunity to motivate and encourage students. While Arndt (1993) highlights the importance of feedback as a ‘central and critical contribution to the evolution of a piece of writing’ (p. 91), Rodger’s (2006) emphasized its significance as such:

… Feedback gives everyone the chance to slow down, to breathe, to make sense of where they've been, how they got there, where they should go next, and the best ways to get there together-a decision made with students, rather than for them (p.219).

Thus, students need to learn that what they write down on paper is not static and that ‘meaning resides not only in these words but also in what the audience brings to the reading of these words’ (Goldstein, 2004, p.64). They can only understand this if they get feedback from readers in a way that shows them what they have intended has been achieved and where their texts may have fallen short of their intentions and goals.

Despite its utmost significance, some teachers may still express concerns about how to provide feedback in ways that their students can effectively use to revise their texts and to learn for future texts because there is still no consensus on how teachers can best react to student errors in writing (Goldstein, 2004). A teacher in Ferris’ (2007) study shows her concern by saying:

The process of giving feedback to students’ writing… fills me with anxiety because I am afraid that it will not help but only confuse the student more (p. 165).

Furthermore, responding to student writing can be the most frustrating, difficult, and time-consuming part of their job because of the heavy workload they have already had. Virginia LaFontana (1996) describes this burden well when she states:

The scene is all too familiar. The school day ends, and we English teachers trudge to our cars, laden with heavier book bags and larger piles of student papers than those of our colleagues in other disciplines. Most of us love the challenge of helping our students become better writers, but the task of providing meaningful, prompt, and frequent feedback to their efforts is enough to give us second thoughts about our career choice (p. 71).

Given that teachers direct so much of their time and effort to commenting on their students’ papers, it is no surprise that a substantial amount of L2 writing feedback research has been conducted on the effectiveness of error correction.

2.2. The Perception of Error Correction throughout the History

Responding to student writing is an important and meaningful area of teachers' work. In the writing classroom, teacher feedback is a valuable instructive device to enhance the teaching and learning of writing (Rahimi and Gheitasi, 2010). Throughout the history, the perception of error correction has changed a lot; and therefore, it has always been a troublesome issue for both teachers and researchers.

A great deal of the research on written feedback in L2 writing has mainly focused on if error correction is effective or not, what strategies and methods teachers prefer to use for error correction, and to what degree students benefit from the feedback they receive on

11

their written work (Ashwell, 2000; Fathman and Whalley, 1990; Ferris and Roberts, 2001; Kepner, 1991; Polio, Fleck, and Leder, 1998; Semke, 1984; Truscott, 2001).

In the 1950s and 1960s, when the audio-lingual approach was popular in foreign language education, errors were widely considered to have a relationship to learning resembling that of ‘sin to virtue’ (Hendrickson, 1978, p. 587), which emphasizes the importance of error-free writing. However, with the introduction of the communicative approach, which arose in 1970s as a response to audio-lingualism, errors began to be treated more tolerably. With this new approach, the focus shifted from being product-based to process-based, and the learners were expected to participate more in the learning process where teachers and students interact with the objective of improving the quality of the text through revision. Teachers have encouraged or required their students to write multiple drafts of their papers and explored various ways to provide feedback in order to help students revise as they move through the stages of the writing process (Ferris, 1997).

In the process approach to writing instruction, teacher feedback and the opportunity to revise written work based on this feedback are keys to students' development as writers (Graves, 1983). In this kind of writing, it is recommended that teachers give feedback on students’ drafts focusing initially on ideas and organization and subsequently on language and style. That is, teachers are advised against placing too much emphasis on language in writing classrooms (Lee, 2007). The rationale behind this idea is that according to writing process pedagogy, an important purpose of the drafting process is for writers to develop and rethink their ideas as they progress from first to final drafts. The first draft is called a draft in part to signal its status as ‘an improvable object’ (Haneda and Wells, 2000, p. 443). Thus, it can be said that process-based writing refers to dynamic assessment involving a development-oriented process which reveals learners’ current abilities in order to help them overcome any performance problems and realize their potential (Shrestha and Coffin, 2012). In that way, as Richardson (2000) states, evaluation can turn into a positive force that encourages growth and independence rather than a means of indicating student deficiencies. Therefore, a power shift can also occur because teacher and students are united in a common effort to improve the students’ writing instead of ‘adversaries in an unequal contest in which one player (the teacher) essentially controls the outcome from the beginning’ (p.120).

Moreover, another common important belief is that it is healthy and normal to make mistakes during the learning process and the learner can get valuable information on the target language through subsequent corrections (Nunan and Lamb, 1996; Matsumura, Patthey-Chavez, Valdés, and Garnier, 2002). To illustrate, in that kind of process-based, learner-centered classrooms, mistakes are regarded as crucial developmental tools moving learners through multiple drafts towards the capability for expressing themselves in an effective way (Hyland and Hyland, 2006). Depending on the fact that it is inevitable for learners to make mistakes while learning a language, teachers have developed various methods to deal with them. However, the question of how, when and by whom these mistakes should be corrected has remained unanswered despite a considerable amount of research that has been done in this field.

Although research on error correction in L2 writing has been popular for many years, the discussion became heated when Truscott (1996) claimed that error correction was something to be avoided as feedback does not help students at all; on the contrary, it harms and discourages them. Moreover, he pointed out that there is little direct connection between error correction and learning. Often a student will repeat the same mistake over and over again, even after being corrected many times. In other words, according to Truscott, there is no convincing research evidence that error correction helps ESL students improve the accuracy of their writing. Since then, the studies attempting to prove the positive or negative effects of error correction on students’ writing ability have increased in number, but the scholars have not reached an agreement on this issue yet. In order to be able to find out the effect of written feedback on the improvement of students’ writing skill, researchers have conducted a wide range of studies involving experimental and control groups, and they have mainly focused on if error correction really helps students improve their writing ability or not.

2.3. Studies that are Against Error Correction Feedback

In spite of the strong arguments developed by the researchers in terms of the advantages of written feedback, there have also been studies which attempt to ascertain that feedback does not help students at all; on the contrary, it harms and discourages them, and it should be abandoned (Truscott, 1996, p. 328). Moreover, Hartshorn (2008) emphasized that Truscott actually makes three key observations in support of his position: 1) The common

13

approaches to error correction ignore second language acquisition research that suggests that acquiring the structures of a second language is a gradual and slow process; 2) Many teachers are unable or unwilling to give adequate error correction feedback, and even when they do, students are often unable or unwilling to use it; and 3) Error correction discourages and demotivates students and takes time and energy away from more productive tasks that can enhance their development as writers.

Truscott mainly based his claim on three L2 studies, which are Semke (1984), Kepner (1991), and Sheppard (1992). These frequently cited studies compared the influence of form-focused feedback and content-based feedback (in isolation and in combination) on various measures of accuracy. Taken as a whole, these studies suggest that form-focused feedback has no significant effect on the writing accuracy of adult learners.

In her study, Semke (1984) worked with German students at a U.S. university over a 10-week period. In this experimental study, she used the results of a writing accuracy test, a writing fluency test, and a close test to compare the effects of four methods of teacher feedback on the first drafts of essays written by learners of German over a ten-week period. These methods included: (1) writing content-focused comments without corrections, (2) making corrections on all errors, (3) writing positive comments with corrections, and (4) marking errors by means of a code for self-correction. Semke, who used a process approach, found that among the four groups, students who received comments alone made the most progress in general language proficiency on both the fluency and close test, while those who had to self-correct their errors made the least progress. Based on her findings, she claimed that students who received feedback on both content and grammar can become confused which type of feedback deserves higher priority, and this may obstruct the development of their writing abilities. She concluded that the way to improve writing accuracy was through the continued practice of writing and that error correction may have a negative effect on learners’ attitudes especially if they have to correct the errors on their own.

In the second one, Kepner (1991) provided students in an Intermediate Spanish as a foreign language course with two types of written feedback on their journal assignments: one group received message-related comments (comments on content) and the other received surface error corrections. Then, Kepner checked the students’ journal assignments which were written after 12 weeks of instruction. Kepner found a negligible difference in terms of

grammatical accuracy between the group who received surface error corrections and the group who received message-related comments on their journal entries. In addition, students who received meaning-focused comments revised significantly better than those who received error correction. Similarly, studies by Leki (1990) and McCurdy (1992) that asked students to evaluate the efficacy of written teacher response have demonstrated that a great majority of students considered the comments on both content and form helpful, utilized them to revise, and particularly appreciated teacher response that led them to positive learning experiences in their revision processes.

As for the third one, Sheppard (1992) compared the effects of two different types of feedback (coded error correction vs. feedback on content) on two comparable groups of intermediate ESL students. Both groups wrote seven compositions, and it was followed by a student-teacher conference where they could discuss any of their concerns about their feedback. The conclusion reached by the author was that feedback on content was superior to feedback on form on the writing assignments of L2 students.

Another study Truscott (1996) used to support his argument against error correction feedback was Robb, Ross and Shortreed’s 1986 experimental study in which the effects of four types of grammar corrections used on the surface errors of Japanese learners of English were examined. These types were: (a) explicit corrections where the errors were pointed out and the correct forms were given; (b) the mistakes were highlighted with a yellow pen without any explanations; (c) the number of errors were tallied at the end of each line without further explanation; and (d) a correction code, which showed both the location and type of error made, was used. In all these cases, the students were asked to rewrite their compositions by making the necessary corrections. At the end of the course, the results showed negligible differences among the groups in terms of accuracy. Consequently, the study concluded that ‘highly detailed feedback on sentence-level mechanics many not be worth the instructors’ time and effort’ if the less salient feedback had the same effect as the comprehensive feedback (p. 91).

In terms of L2 writing, Zamel (1987) was also critical of the way L2 teachers responded to their students’ writing, asserting that teachers acted more like language teachers than composition teachers. Zamel noted, for instance, that teachers ‘are so distracted by language-related problems that they often correct these without realizing that there is a much larger, meaning-related problem that they have failed to address’ (p. 700). Connors

15

and Lunsford (1993), Sommers (1982), Applebee (1981) and McAndrew and Reigstad (2001) also agree on the idea that teacher comments tend to focus on low level, technical concerns rather than on meaning-making, which makes written feedback a problematic practice. Similarly, Cohen and Cavalcanti (1990) claim that feedback that lacks balance among form and content and that is unclear and inaccurate can be regarded ineffective. As for teacher beliefs and perceptions regarding error feedback, in a study by Lee (2003), a questionnaire was administered to 206 secondary English teachers in Hong Kong, and follow-up telephone interviews were conducted with 19 of them. The teachers were asked questions about how they corrected student errors in writing, how they perceived their work in error correction, as well as their concerns and problems. The results of the study show that although selective marking is recommended both in the local English syllabus and error correction literature, the majority of teachers tend to mark errors comprehensively. However, at the same time, teachers themselves are not completely convinced that their effort pays off in terms of student improvement, but they still spend too much time marking student writing. As a result of this study, it is obvious that teachers are not totally satisfied with their own practice, and what they need is help and guidance to handle this challenging and significant aspect of their work.

2.4. Studies that are for Error Correction Feedback

There are a number of studies that have found that students benefit from teacher feedback. One of these studies was carried out by Fathman and Whalley (1990). In their study, there were three groups that either received feedback on form, content, or a combination of both. There was also a control group who received no feedback. This study showed that the groups who were provided with feedback on form and feedback on content seemed to show improvement in accuracy, which indicates that teacher feedback helps students develop their writing skills. Their study focusing on feedback on content and/or form inspired other researchers as well.

Another study which was conducted by Soori, Janfaza and Zamani (2012) in the Iranian context aimed at exploring the effect of teachers’ written feedback on students’ composition with regard to form and content. They examined any probable improvement in writing ability for a group of 47 EFL students under four feedback conditions, which are no feedback, feedback on form, feedback on content, and feedback on both form and

content. The results of this study showed that whereas providing feedback on form or content improved the students’ writing significantly, the absence of feedback would not help the students’ writing improvement.

In another study, Chandler (2003) used experimental and control group data to show that students’ correction of grammatical errors between assignments reduces such errors in subsequent writing over one semester without reducing fluency or quality. According to the results of his study, having the teacher either correct or underline all the grammatical errors for student self-correction in the autobiographical writing of high intermediate to advanced ESL undergraduates resulted in a significant improvement in accuracy.

In their study, using a no-feedback control group, Bitchener, Young, and Cameron (2005) examined two types of error correction feedback on three grammatical features (prepositions, the simple past, and the definite article). They compared direct written corrective feedback and an oral conference after each piece of writing with direct written corrective feedback only in order to determine the impact on the writing accuracy of 53 ESL post-intermediate adult students. The study found a significant effect of the combination of written and oral feedback in the use of the simple past and the definite article in new pieces of writing.

While partially acknowledging some of Truscott’s claims, Ferris (2002) argues that teachers should continue giving error correction feedback because (a) several studies have shown that error correction feedback helps students in the short term, (b) surveys of ESL student opinions have found that students both attend to and appreciate teachers’ comments on their errors (Ferris, 2002; Goldstein, 2001), and (c) error correction feedback helps students become ‘independent self-editors’ (Ferris, 2002, p. 9).

2.5. A Shift in the Focus of Teacher Feedback

Beginning in 1990s, several studies showed that the heavy focus on grammar in teacher feedback started to change in writing instruction (Caulk, 1994; Ferris, 1995; Hedgcock and Lefkowitz, 1994; Saito, 1994). In their 1990 study, for example, Cohen and Cavalcanti (1990) observed that the three instructors addressed both textual and organizational issues in their students’ compositions. In a later study, Conrad and Goldstein (1999) found that besides grammatical concerns, teachers also addressed a broad range of issues that

17

included coherence, cohesion, paragraphing, content, and purpose in written texts. According to Hartshorn (2008), one reason for this shift was the widespread use of the communicative language approach, which focused on meaning rather than on form. This is due to the fact that the theories of communication have the tendency to take a constructivist approach in which writing is fundamentally a social act, and meaning is constructed through the relationship between writer and reader (Smagorinsky, 1996). As Hyland (2003) states, writing is learnt, not taught, and the teacher is ‘non-directive, facilitating a cooperative environment’ (p. 18). A second reason, as Hartshorn (2008) asserts, is that a number of L2 written feedback studies discouraged further research by concluding that error correction has no facilitative effect on students’ writing accuracy. Among such studies are the ones by Jones (1985) and Sheppard (1992), who emphasize that teacher response focusing primarily on linguistic form can discourage students from revising altogether and, thereby, deprive them of the incentive to make deeper discourse-level changes. In addition, there are the others who agree on the idea that teacher feedback should encourage problem-solving and critical thinking (Cumming, 1989; Langer and Applebee, 1987; Leki and Carson, 1994), which is quite similar to the idea that ideally, teacher feedback enables students to expand and shape their ideas over subsequent drafts of their work (Ferris, 1997; Sternglass, 1998; Zeller-mayer, 1989). Otherwise, students start seeing teachers only in their parental role, and they will look to them for answers (Hirseh Jr and Gabriel, 1995).

Since the 1990s after the shift in the focus of teacher feedback, L2 writing feedback research has concentrated on a few key areas, which include student perceptions of teacher feedback, the tone of written feedback (i.e., praise, criticism), the mode of teacher feedback (i.e., oral, written, or computer mediated), and the effectiveness of various approaches to responding to student writing. For example, as Kagıtcı (2013) states, students have mostly been asked what type of feedback they prefer to receive (i.e. direct, indirect, error codes, conferencing, etc.) and whether they prefer teacher feedback, peer feedback or self-correction. All these points matter as teachers’ feedback methods and styles send very strong, and sometimes undesirable, messages to their student writers. The main significant point is that no matter what the purpose of feedback is (whether to improve form or content, or both), teachers have to keep in mind that students must understand the feedback and be capable of doing something with it (Hedgcock and Lefkowitz, 1994; Hyland and Hyland, 2001).

2.5.1. The Tone of Teacher Feedback

Chiang (2004) carried out a classroom research study to investigate Hong Kong students’ preferences for and responses to teacher feedback. It is suggested that the ineffectiveness of teacher feedback may not lie in the feedback itself, but in the way how feedback is delivered to students. The students stated that they felt discouraged when they received too much negative feedback, and they did value teacher feedback despite having difficulty in making use of the feedback. In Dragga’s (1986) study, 40 student essays were analyzed, and it was found that 94% of comments focused on what students had done poorly or incorrectly. Some further studies examine the different effects of focusing on positive and negative aspects of texts. Taylor and Hoedt (1966), for example, failed to find any difference in the quality of writing produced by students receiving either positive or negative feedback, although they showed that negative feedback had a detrimental effect on writer confidence and motivation. Gee (1972) also reported no significant differences in quality of writing, but more positive attitudes from those whose writing had been praised. A point to be taken into consideration has been emphasized by Hyland and Hyland (2001). They think that teachers’ positive comments need to be specific rather than formulaic and closely related to actual text features rather than general praise. Most importantly, praise should be sincere due to the fact that students are quite good at recognizing ‘formulaic positive comments which serve no function beyond the spoonful of sugar to help the bitter pill of criticism go down’ (p.208). All these make it inevitable that teachers should constantly examine their commentary both in terms of its form and its content to be able to decide on what is working and what is not so that if any changes are needed, they will be made (Goldstein, 2004).

At that point, Richardson (2000) suggests that teachers can phrase their commentary in the form of questions, rather than commands, usually to indicate parts that need further clarification or elaboration. Straub (1997) also argues that teachers ‘should move beyond the conventional roles of examiner, critic, and judge, and should take on the roles of reader, coach, mentor, fellow inquirer, and guide’ (p.92). According to Stern and Solomon (2006), one effective feedback principle is to provide positive comments in addition to corrections, which can be accomplished by including compliments on inventive ideas, questions to inspire further inquiries, and evaluation on how andto what extent the goals of the assignment are achieved. Moreover, they believe that kind of positive comments can

19

have a positive impact upon student motivation, attitude toward writing, and learning experience. As for Corno and Cardelle (1981), they believe that written feedback identifying students' errors, guiding them towards a better attempt next time and providing some positive comment on work particularly well done certainly has a positive effect on students' performances. Likewise, in Peterson and McClayb’s (2010) study, 216 teachers believe that the key ingredients of student improvement in writing are praise and encouragement. What Hyland and Hyland (2006) express actually summarizes that point. They think that teachers are generally conscious of the potential feedback has for helping to create a supportive teaching environment. Additionally, they are aware of the need for care when constructing their comments. They know that writing is very personal and that students’ motivation and self-confidence as writers may be damaged if they receive too much criticism whereas praise can be used to help reinforce appropriate language behaviors and to foster students’ self-esteem. One way to soften a face-threatening situation suggested by Mills is that teachers can use politeness strategies such as indirect speech forms (2003).

Despite its benefits, there are situations where indirect feedback cannot be helpful especially when it is not well understood. In fact, research suggests that indirect speech forms are more difficult to interpret than direct speech (Champagne, 2001), and indirect speech often takes significantly longer to respond to than direct speech because it may take more mental processes to understand (Holtgraves, 1999). In fact, previous research has suggested that teacher feedback written in direct speech acts is easier to understand and leads to more accurate revisions than feedback written in indirect speech acts (Ferris, 1997; Hansen, 2006). If feedback written in direct speech acts is indeed easier to understand, then students may not be able to interpret indirect speech in teacher written feedback (Rings, 2006). For example, even though teachers use indirect speech acts to be more polite, students may not expect indirect or polite forms, and therefore may not see these forms as criticism. This is especially true since feedback can be both positive and negative. For example, a student may find it difficult to know whether a statement such as ‘you have a lot of ideas here’ is a compliment or if it is an indirect request to delete material.

On the other hand, although teachers have their best intentions while trying to respond positively and effectively, ‘the effect of their mitigation can often be to make the meaning unclear to the students, sometimes creating confusion and misunderstandings’ (Hyland and

Hyland, 2001, p.207). Therefore, they state that dealing with problems and possible solutions quite frankly is especially important with learners of low English proficiency because they may be less familiar with indirectness and may fail to understand implied messages. Finally, Hyland and Hyland (2001) made a conclusion with the idea that the ways teachers frame their comments can alter students’ attitudes to writing and lead them to improvements, but their words can also confuse and dishearten them. That is why, it can be said that ‘it is a practice that carries potential dangers and requires careful consideration’ (p.207). Chandler (2003) also puts an emphasis on the importance of directness by stating that it reduces the type of confusion that can occur if learners fail to understand or remember what the feedback is saying.

2.5.2. Factors Affecting Students’ Utilization of Teacher Feedback

2.5.2.1. Students’ Perception of Effective Feedback

Focusing on students’ perceptions of teacher feedback in his study, Enginarlar (1993) investigated the attitudes of 47 freshmen students towards the feedback procedure employed in the Writing Composition class at a state university in Ankara, Turkey. In his application, he not only used error codes to indicate linguistic errors but also various types of comments to help students improve their drafts. His conclusion displays important findings as to the students’ perception of what effective feedback is. The students believe that effective feedback involves attention to linguistic errors, guidance on compositional skills, and overall evaluative comments on content and quality of writing. Hedgcock and Lefkowitz (1994), Lee (2007) and Lo and Hyland (2007) also emphasize the idea that some students wish their teachers to give them feedback on content and organization of their work. What these students mean with content is ‘comments to delete, re-organize, or add information, as well as questions intended to challenge students’ (Matsumura et al., 2002, p.11).

21

2.5.2.2. The Focus of Teacher Feedback

Student expectations do not seem to be in complete harmony with teacher feedback practices in writing classes. Searle and Dillon (1980), for example, examined 135 pieces of students’ classroom writing on which 12 teachers of Grades 4 to 6 had written their usual comments. They found that teachers responded to the form of the writing to a much greater extent than to its content. Similarly, what Stern and Solomon (2006) indicated in their study was that most teacher comments were technical corrections that addressed such points as spelling, grammar, word choice, and missing words. Macro- and mid-level comments addressing paper organization and quality of the ideas were surprisingly absent. They stated that the lack of these larger idea and argument centered comments may prevent students from improving the quality of the larger issues in written work and ‘refocus them on the smaller, albeit important, technical issues of writing’ (p.22).

Stern and Solomon (2006) suggest that more comments on ideas should be made since most papers in writing classes are about communicating ideas. Thus, by commenting on supporting evidence, teachers may help students to realize that the quality of their ideas often depends on the supporting evidence or thoughts that they support them with. In other words, if the concern is having students write error-free sentences, the generation of ideas may be stifled (Polio et.al, 1998). Todd, Khongput, and Darasawang (2007) point out that teachers can make comments on the content of their students’ written work by asking for clarification or additional information when necessary. In the study conducted by Lam (2013), some of the students found revision of content errors cognitively challenging, yet they still considered that performing revision at the discourse level could help ‘improve their writing abilities in general and the overall quality of texts in particular’ (p.139). Keppner (1991) and Olson and Raffeld (1987) indicated that teacher feedback about content such as comments encouraging students to add and delete content and/ or restructure content ideas as opposed to teacher feedback about surface features such as word choice and grammar during the revision process is associated with higher-quality revisions.

Likewise, in a study conducted by Sheppard (1992), the ESL writers who received extensive content-focused feedback produced essays that improved in terms of both content and linguistic accuracy, which points to highly positive effects for teacher response. Boice (1985) also puts emphasis on the idea that practice in writing should

contribute to ‘an increased fluency in generating ideas, including some ideas that might be labeled novel, useful, and creative’ (p.473). Taylor (1981) justifies the necessity of generating ideas by reminding us of the reality, which requires students to start producing content immediately after they are accepted into academic programs even if their language is still not ready. At that point, he suggests that students brainstorm to easily notice the links and relations among ideas, facts, and observations. In that way, they can gather information in order to be able to write a first draft simply by getting their ideas in paper without being concerned about the form. The written information generated up to this point can serve as data to be shaped and refined. Thus, students can now ask their teachers for feedback on the content of their written work, which means that the revision process begins. In other words, students can get the opportunity to clarify unclear points and elaborate on inadequately supported ideas.

In conclusion, the concern of both students and the teacher should be with the communicative effectiveness of the text rather than with whether or not a particular form was applied to the construction of the text (Brannon and Knoblauch, 1982; Siegel 1982).

2.5.2.3. Students’ Revision Habits as a Result of Teacher Feedback

According to Bereiter and Scardamalia (1987), Graham, Schwartz, and MacArthur (1993) and McCutchen (1995), if writers are not involved in self-regulatory activities, they generally produce poorer texts in terms of communicative effectiveness than do more self-regulated writers. Differences among these writers in the study were primarily found in the activities of planning and revision. More proficient writers devote more attention to planning their writing. They plan not only what they write but also how to write it, establish goals for writing, organize ideas, and consider the needs of the intended readers. For less proficient writers, it is very common to start writing immediately or to spend little time on planning. Like planning, revision also plays a limited role in the writing process of less proficient writers. More proficient writers revise for meaning and make sentence- and topic-related changes, whereas the revisions of less proficient writers are limited to lower-level aspects, such as spelling and grammar.

To see how students used their teachers’ comments in their writing, Hedgcock and Lefkowitz (1996) compared 21 foreign language (FL) and ESL college level participants,

23

using both quantitative (survey and factor analysis) and qualitative techniques (interviews). They found that although the FL students were fully aware that their teachers wanted them to add examples or elaborate on certain points in their compositions, they considered and expected composing and revision in an L2 to be a means for practicing their linguistic skills through writing, rather than ‘trying out new ideas or demonstrating creativity’ (p. 297). In contrast, the ESL students believed that the main purpose of writing was the development of ideas and being evaluated in academic settings, which meant that each group had expectations for a different type of feedback. The reason for that kind of an attitude by FL students can be what Silva (1993) suggests:

It is clear that L2 composing is more constrained, more difficult, and less effective. L2 writers did less planning (global and local) and had more difficulty with setting goals and generating ideas and organizing material. Their transcribing was more laborious, less fluent, and less productive—perhaps reflective of a lack of lexical resources. They reviewed, reread, and reflected on their written texts less, revised more—but with more difficulty and were less able to revise intuitively (p. 670).

Another reason why students don’t make use of teacher comments on their written work can be related to what Knoblauch and Brannon (1981) assert in their seminal article. They think that there isn’t enough evidence to show that students typically even comprehend teacher responses to their writing, let alone use them purposefully to modify their practice. A similar idea is that learners need to notice the feedback first and act on it, for the feedback to result in language learning (Qi and Lapkin, 2001; Sachs and Polio, 2007). However, even when they do understand a comment, research shows that students may still have difficulty figuring out a strategy for revising (Cohen, 1991; Conrad and Goldstein, 1999; Goldstein and Kohls, 2002), or they vary with regard to how successfully they are able to use the teacher’s feedback to revise (Conrad and Goldstein, 1999; Dessner, 1991; Ferris, 1997; Goldstein and Kohls, 2002). According to Pea and Kurland (1987), students face a dual set of difficulties while learning to revise: First, it is difficult for them to self-monitor what their writing problems are. Second, even though they are able to identify these problems, they lack ‘access to techniques and methods for overcoming them’ (p. 295). As a result of this, although students attempt to revise, the changes they have made do not always lead to an improved product (Beal, 1996). Moreover, Beal (1996) claims that students tend to overestimate the comprehensibility of the text and cannot realize that the reader may not understand it. The reason for this can be the fact that social and cultural knowledge of texts and contexts and the ability to shift perspective from writer of a text to

the reader of a text are required to understand the reader’s possible reception of one’s writing (Holliway and McCutchen, 2004).

Students also differ in terms of how much of their teachers’ feedback they actually use (Cohen, 1991; Conrad and Goldstein, 1999; Ferris, 1997; Goldstein and Kohls, 2002). Students may also lack the time to do the revisions (Conrad and Goldstein, 1999; Goldstein and Kohls, 2002; Pratt, 1999), or they may lack the content knowledge to do the revision (Goldstein and Conrad, 1999). Furthermore, when everything is said and done, unfortunately, if the students are not committed to improving their writing skills, they will not improve, no matter what type of feedback is provided (Gue´nette, 2007). That is, with low motivation, students are less likely to take teacher feedback seriously and find it useful.

As for Sommers (2006), she reports that ‘most comments, unfortunately, do not move students forward as writers because these comments underwhelm or overwhelm them, going unread and unused’ (p.250). Therefore, she states that it is quite normal for teachers to wonder whether their students really read their comments and what, if anything, they take from them considering the tremendous amount of time spent commenting upon a single paper, let alone twenty or thirty. With a different viewpoint, Conrad and Goldstein (1999) also state that it is very likely for students to misinterpret written commentary when revising drafts. Another problem can be related to teachers’ giving vague prescriptive advice instead of providing their students with specific strategies, questions, and suggestions that might help students reshape their texts (G. Smith, 1982; Winterowd 1983). Dessner's study of the responding practices of 10 college ESL teachers also found that two thirds of the teachers' commentary provided the students with advice and suggestions (i.e., not just corrections), and that these types of meaningful comments appeared to contribute to substantive student revisions (1991). Similarly, according to Ferris (1995), Jenkins (1987) and Straub (1997), while students prefer longer comments which explain specific problems and make specific suggestions, they tend to find short, general comments and comments questioning content more difficult to use. However, it is also important to note that two studies of ESL students’ responses to comments (Enginarlar, 1993; Radecki and Swales, 1988) indicate that the same sort of feedback may elicit different responses from different students, which emphasizes differences in students’ individual reactions to feedback.