COST-BENEFIT ANALYSIS OF KIDNEY DONATION SYSTEMS AND AN ALTERNATIVE SYSTEM PROPOSAL FOR TURKEY

A THESIS SUBMITTED TO

THE INSTITUTE OF SOCIAL SCIENCES OF YILDIRIM BEYAZIT UNIVERSITY

BY

YAVUZ DEMİRDÖĞEN

IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR

THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY IN

THE DEPARTMENT OF BANKING AND FINANCE

Approval of the Institute of Social Sciences

Asssociate Prof. Dr. Seyfullah Yıldırım Acting Manager of Institute

I certify that this thesis satisfies all the requirements as a thesis for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Department of Banking and Finance.

Assoc. Prof. Dr. Ayhan KAPUSUZOĞLU Head of Department

This is to certify that we have read this thesis and that in our opinion it is fully adequate, in scope and quality, as a thesis for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Department of Banking and Finance.

Prof. Dr. Fuat OĞUZ Supervisor

Examining Committee Members

Prof. Dr. Fuat OĞUZ (YBU, Economics) _____________

Assist. Prof. Dr. Erhan ÇANKAL (YBU, Banking and Finance) _____________ Assis. Prof. Dr. Fatih Cemil ÖZBUĞDAY (YBU, Economics) _____________ Assoc. Prof. Dr. Fetullah AKIN (Gazi Uni., Economics) _____________ Assist. Prof. Dr. Erkan GÜRPINAR (ASBU,Economics) _____________

iii

PLAGIARISM

I hereby declare that all information in this thesis has been obtained and presented in accordance with academic rules and ethical conduct. I also declare that, as required by these rules and conduct, I have fully cited and referenced all material and results that are not original to this work; otherwise I accept all legal responsibility.

Name, Last name: Yavuz DEMİRDÖĞEN

iv

ABSTRACT

COST-BENEFIT ANALYSIS OF KIDNEY DONATION SYSTEMS AND AN ALTERNATIVE SYSTEM PROPOSAL FOR TURKEY

Yavuz DEMİRDÖĞEN

Ph.D., Department of Banking and Finance Supervisor: Prof. Dr. Fuat OĞUZ

April 2017, 203 pages

This study analyzes the cost and benefit of the kidney donation system in Turkey through the analyses of the costs of hemodialysis and kidney transplantation. These analyses were made by using real data. Afterwards, a sensitivity analysis is made by the use of the results of the cost-benefit analysis. One other sensitivity analysis is made for the determination of the amount of the monetary incentive. Within the framework of this study, an alternative system for increasing organ donation rates is proposed which is based on the following three pillars: an opt-out system, a monetary incentive and a government monopsony.

Keywords: Cost-benefit analysis, organ donation, kidney transplantation, monetary incentive.

v

ÖZET

COST-BENEFIT ANALYSIS OF KIDNEY DONATION SYSTEMS AND AN ALTERNATIVE SYSTEM PROPOSAL FOR TURKEY

Yavuz DEMİRDÖĞEN

Ph.D., Department of Banking and Finance Danışman: Prof. Dr. Fuat OĞUZ

Nisan 2017, 203 sayfa

Bu çalışmada, hemodiyaliz ve böbrek nakil maliyetleri hesapları üzerinden Türkiye’deki bağış sisteminin maliyet-fayda analizi yapılmaktadır. Bu analizlerde gerçek veriler kullanılmıştır. Yapılan maliyet-fayda analizinin sonuçlarıyla duyarlılık analizi yapılmıştır. Bir başka duyarlılık analizi de parasal teşvik miktarının tespiti için yapılmıştır. Bu çalışmanın ışığında organ bağışını artırmak amacıyla üçayak üstüne kurulan alternatif sistem önerisi yapılmıştır: zorunlu donor sistemi, parasal teşvik ve devlet monopsonisi.

vi

DEDICATION

vii

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

I would like to extend my special thanks to;

…to my thesis advisor, Prof. Dr. Fuat OĞUZ for his guidance, support, encourager attitude and enlighten the path of every step whether it is a dead-end.

…the examining committee members, Assist. Prof. Dr. Fatih Cemil ÖZBUĞDAY, Assist. Prof. Dr. Erhan ÇANKAL, Assoc. Prof. Dr. Fethullah AKIN and Assist. Prof. Dr. Erkan GÜRPINAR for their precious contributions and criticisms.

…my friends and colleagues for their support and encouragements.

…Ayhan AYDIN for editing, proofreading and eliminating the deficiencies. I would also like to extend my sincerest gratitude and appreciation to;

…my all family members for moral support to academic studies and for their invaluable love, support and encouragements.

…AND my beloved wife and precious daughters for their patience, encouragement and support at every time of my life.

viii TABLE OF CONTENTS PLAGIARISM ... iii ABSTRACT ... iv ÖZET ... v DEDICATION ... vi ACKNOWLEDGMENTS ... vii

TABLE OF CONTENTS ... viii

LIST OF TABLES ... xii

LIST OF FIGURES ... xiii

LIST OF ABBREVIATIONS ... xiv

PART I: THEORY AND WORLD EXPERIENCE ... 1

1. INTRODUCTION ... 1

2. HISTORICAL DEVELOPMENT OF ORGAN TRANSPLANTATION ... 6

2.1. Definition of Brain Death ... 8

2.2. History of the Legal Status about Organ Donation ... 10

2.3. History of Organ Transplantation in Turkey ... 17

3. WHAT IS CHRONIC KIDNEY DISEASE (CKD)? ... 20

3.1. Initial Symptoms of CKD ... 22

3.2. Diagnosis of CKD ... 23

4. SUPPLY AND DEMAND OF KIDNEY AROUND THE WORLD ... 25

4.1. Supply of Transplantable Organs... 32

4.1.1. Transplantable Organs... 33

4.1.2. Approval of Next of Kin ... 35

4.1.3. Legal Procedures ... 36

4.1.4. Availability ... 38

ix

4.1.6 Time ... 40

PART II: ECONOMICS OF KIDNEY DONATION ... 42

5. DONATION SYSTEMS AROUND THE WORLD ... 42

5.1. Deceased Organ Procurement Policies ... 42

5.1.1. Presumed Consent ... 43

5.1.2. Informed Consent ... 44

5.1.3. Mandated Choice... 45

5.1.4. Enforced Donor ... 46

5.2. Monetary Incentive Mechanism Regimes ... 46

5.2.1. Free Market System ... 46

5.2.2. Government Monopsony ... 48

5.2.3. Reimbursement System ... 50

5.3. Future Delivery Market ... 51

5.3.1. Opt-in Future Contract System ... 51

5.3.2. Opt-out Future Contract System ... 51

5.4. Living Organ Procurement Policies ... 52

5.4.1. Policies Based on Monetary Incentives ... 53

5.4.1.1. Government Monopsony ... 53

5.4.1.2. Reimbursement of Living Donors ... 55

5.5. Non-monetary Organ Allocation ... 57

5.5.1. Pairwise Kidney Exchange... 58

5.5.2. NEAD Chain and Domino Paired Donation ... 59

6. ECONOMIC DIMENSION OF KIDNEY DONATION ... 61

6.1. Donation In Terms of Basic Economic Theory ... 61

6.2. Determinants of Supply ... 63

6.2.1. Altruism ... 63

x

6.2.3. Effect of Healthcare System ... 66

6.3. Determinants of Demand ... 66

6.3.1. ESRD Patients ... 66

6.3.2. Legal Regulations ... 66

6.4. Effect of Monetary Incentives on Supply and Demand ... 68

7. KIDNEY BLACK MARKET AND TRANSPLANT TOURISM ... 71

PART III: TURKEY ... 75

8. LEGAL REGULATIONS IN TURKEY ... 75

8.1. Organ and Tissue Allocation Principles ... 75

8.2. Donation and Transplantation from Living Donor ... 76

8.3. Kidney Allocation Principles ... 76

9. KIDNEY TRANSPLANTATION AND DONATION IN TURKEY ... 79

9.1. Legal Status ... 79

9.2. Change in the Last Decade ... 83

9.3. Fundamentals of Selection Process and Urgency of Transplant Patients in General 86 10. COST ANALYSIS ... 89

10.1. Cost of Dialysis in Turkey ... 89

10.2. Cost of Transplantation in Turkey ... 91

10.3. Comparison between Transplantation and Dialysis Costs ... 93

10.4. Cost-Benefit Analysis of Kidney Transplantation in the World ... 99

10.5. Cost Analysis of Hemodialysis ... 100

10.6. Cost Analysis of Transplantation ... 103

11. COST-BENEFIT ANALYSIS OF KIDNEY TRANSPLANTATION IN TURKEY ... 107

11.1. Sensitivity Analysis ... 109

xi

12. AMOUNT OF MONETARY INCENTIVE AND ITS EFFECTS ON KIDNEY

DONATION IN TURKEY ... 113

12.1. Kidney Transplantation and Dialysis in Turkey ... 116

12.2. Economic Analysis of Monetary Incentive... 117

12.3. Sensitivity Analysis ... 121

12.4. The Benefits of Decreasing the Number of Patients on the Waiting List ... 124

12.5. Encouraging Living Donation ... 127

PART IV: RECOMMENDATIONS ... 129

13. AN ALTERNATIVE PROPOSAL FOR KIDNEY DONATION SYSTEM IN TERMS OF SOCIAL WELFARE ... 129

13.1. Governmental Regulations for Incentive Systems ... 135

13.2. Evaluation of Applications around the World ... 138

13.3 Discussion ... 142

14. CONCLUSION ... 146

15. REFERENCES ... 149

16. APPENDICES ... 178

Appendix 1: Details of Calculations ... 178

Appendix 2: Briefing about Data Collection and Gathering ... 180

Appendix 3: Calculation Data Set ... 181

Appendix 4: Curriculum Vitae ... 182

xii

LIST OF TABLES

Table 1: Major legislative and regulatory landmarks and other requirements affecting

organ procurement organizations (OPOs). Source: Howard et al. (2012) ... 15

Table 2: Some articles from Turkish Law on harvesting, storage, grafting and transplantation of organs and tissue. Source: Haberal and Karaali (2005) ... 18

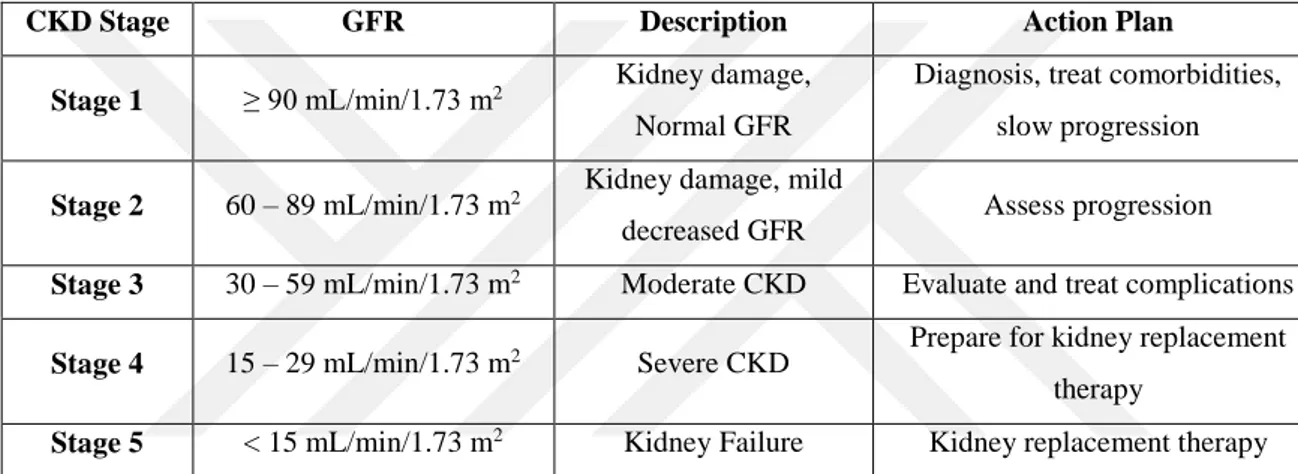

Table 3: Five stages of chronic kidney disease as defined by KDOQI guidelinesa ... 21

Table 4: Albuminuria categories of CKD... 21

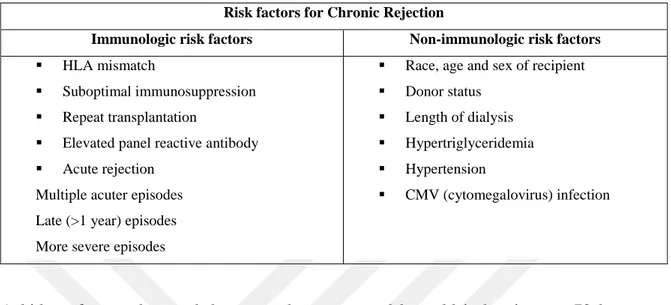

Table 5: Risk factors for chronic rejection ... 26

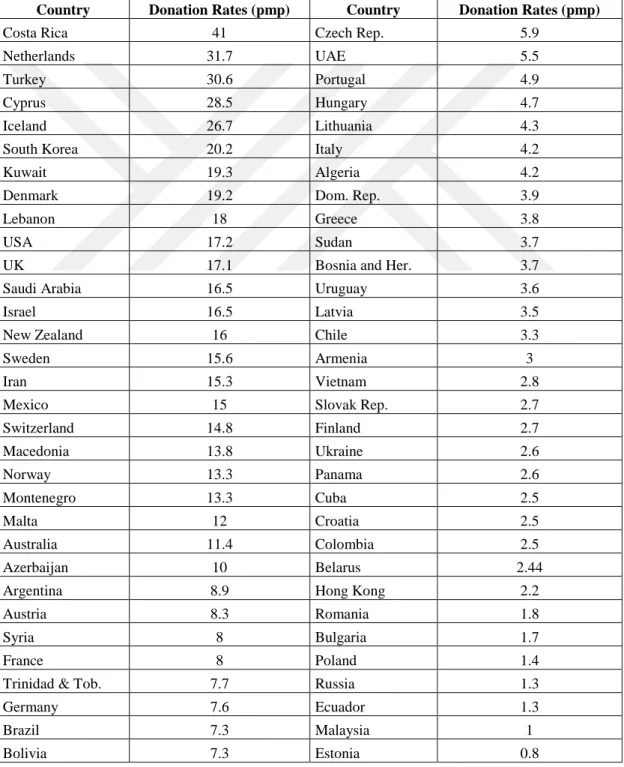

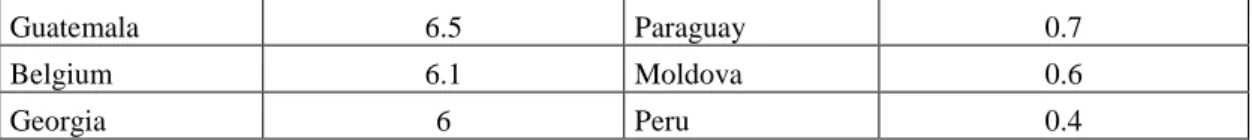

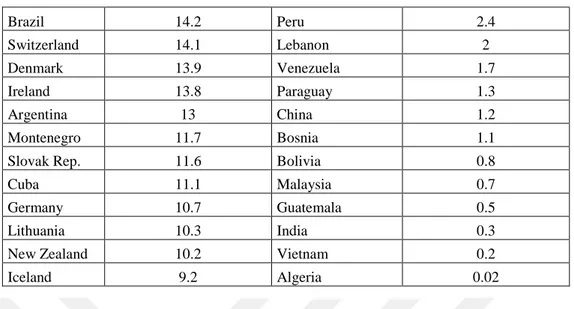

Table 6: Kidney transplant from deceased donors 2014 ... 28

Table 7: Kidney transplant from living donors 2014 ... 29

Table 8: Worldwide actual deceased organ donors 2014 ... 30

Table 9: Worldwide living organ donors 2014 (Source: IRODat Registry 2015)... 31

Table 10: Transplantation quantities from living and deceased donors (2011-2015) ... 84

Table 11: Costs of HD, PD, Tx from living and deceased donor for countries ... 96

Table 12: Cost of a Hemodialysis Patient ... 102

Table 13: The cost-benefit analysis of transplantation ... 108

Table 14: Sensitivity analysis of change in donation, transplantation and waiting list figures ... 110

Table 15: Change in number of transplantations according to VSL ... 122

Table 16: The list of penalties imposed in countries. Source: Bilgel (2011) ... 139

xiii

LIST OF FIGURES

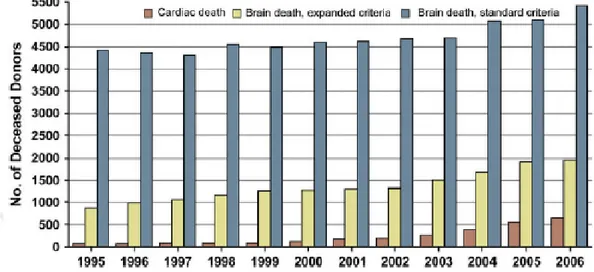

Figure 1: Distribution of organ donation from brain death and cardiac death in the U.S. .. 11

Figure 2: Major legislative and regulatory landmarks of organ donation and transplantation (U.S.) Source: Howard et al. (2012) ... 14

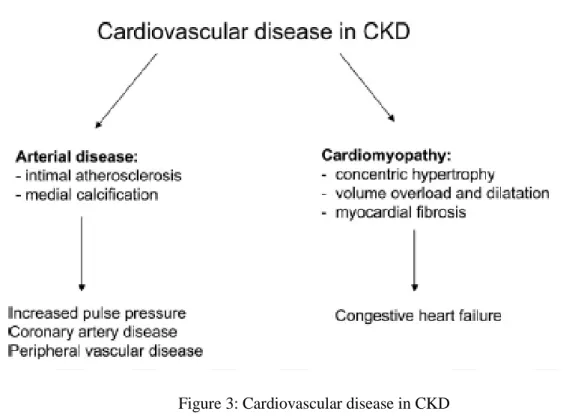

Figure 3: Cardiovascular disease in CKD ... 23

Figure 4: Elements of protocols recovering organs after cardiac death. ... 34

Figure 5: WHO Guiding principles on Human Cell, Tissue and Organ Transplantation ... 39

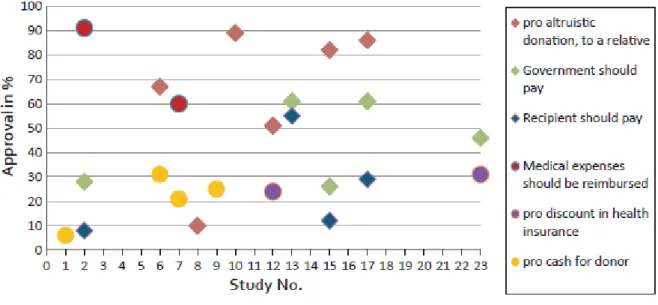

Figure 6: Percentage of approval of different models of FI for LD in comparison to percentage of willingness to donate altruistically to a relative. ... 56

Figure 7: Percentage of approval of different models of FI for LD in comparison to percentage of willingness to donate altruistically to a relative or a donation to a charity or getting priority in a waiting list in case one needs later an organ transplant. ... 57

Figure 8: Historical evolution of kidney paired donation from its original proposal by Felix Rapaport to present. Source: Wallis et al. (2011, p. 2092) ... 58

Figure 9: Schematic representation of exchange systems. ... 60

Figure 10: Simplified graph of supply and demand ... 62

Figure 11: Supply of kidney used normal conditions ... 62

Figure 12: Number of patients and transplants between 2011 and 2015... 63

Figure 13: The quantity of patients added to the waiting list (yearly basis) ... 85

Figure 14: The transplantation data and the graph of Turkey ... 86

xiv

LIST OF ABBREVIATIONS

BMI : Body Mass Index

CIBA : Chemical ındustry in Basel CKD : Chronic Kidney Disease CV : Cardiovascular Disease DBD : Donor after Brain Death DCD : Donor after Cardiac Death

DHCA : Deep hypothermic circulatory arrest DNA : Deoxyribose Nucleic Acid

DPD : Domino - Paired Donation

EDTA-ERA : European Dialysis and Transplant Association-European Renal Assoc. ESRD : End Stage Renal Disease

GDP : Gross Domestic Produce GFD : Glomerular Filtration Rate

HD : Hemodialysis

HLA-DR : Human Leukocyte Antigen - antigen D Related HNA (HAN) : Health Notification Application (SUT)

IBPS : Incentive Based Procurement Systems ICU : Intensive Care Unit

IRODat : International Registry in Organ Donation and Transplantation KDIGO : Kidney Definition Improving Global Outcomes

KDOQI : Kidney Disease Outcomes Quality Initiative KPD : Kidney Paired Donation

MDAT : Mobile Donor Action Team

MESOT : Middle East Society of Organ Transplantation

NATCO : North Ame4rican Transplant Coordinators Organization NCC : National Coordination Center

NEAD Chain : Non-simultaneous Extended Altruistic Donor Chain NGOs : Non-Governmental Organizations

NOTA : National Organ Transplantation Act NPV : Net Present Value

xv OPOs : Organ Procurement Organizations

OPTN : Organ Procurement and Transplant Network PD : Peritoneal Dialysis

PKE : Pairwise Kidney Exchange pmp : per million people

PPP : Purchasing Power Parity QALY : Quality Adjusted Life Years RCC : Regional Coordination Center SCIE : Science Citation Index Expanded

SEROPF : South-Eastern Regional Organ Procurement Foundation SEROPP : South-Eastern Regional Organ Procurement Program TRY : Turkish Lira

TNA : Turkish Nephrology Association TNA : Turkish Notification Association TPC : Turkish Penal Code

TPN : Turkish Penal Notification TSI : Turkish Statistical Institute Tx : Transplantation

UCLA : University of California

UNOS : United Network of Organ Sharing VSL : Value of a Statistical Life

WHA : World Health Assembly WHO : World Health Organization

1

PART I: THEORY AND WORLD EXPERIENCE

1. INTRODUCTION

Within the last century, the world witnessed outstanding advancements in the field of surgery and organ transplantation with success ratios up to 80-90%. However there is a huge difference between the number of organs available for transplantation and those in need of transplantable organs. Rephrasing the preceding sentence within the context of economics, the fact is that there is a huge gap between the supply and demand of transplantable organs with shortage on the supply side. The only source of supply for transplantable organs is the human body. Among the transplantable organs, kidney comprises the major demand. There are systems regarding transplantation and they are based on donation around the world. For the last few decades the gap is growing drastically and the systems mentioned are insufficient to balance the supply and demand of transplantable organs and specifically within the scope of this thesis, the shortage of kidneys. There is no recent or a solid study about the costs and benefits of kidney transplantation in Turkey. This thesis primarily aims to calculate the costs of dialysis and/versus transplantation and to focus on the benefits of increasing the number in donations. This number of donations is further used in a sensitivity analysis of economic gains by increase in donations in section 11.1. Beyond ethical concerns, the economic dimension of compensated kidney donation is depicted. This compensation in concern is based on the loss (es) of the donor, not on the commodification of the kidney. A monetary incentive would be affected especially with the value of a statistical life (VSL). Another sensitivity analysis of the effect of monetary incentive by changing the VSL is given in section 12.3.

Among the many challenges during this study, data collection from related organizations and stakeholders such as hospitals, Social Security Institution and Ministry of Health

2

(Turkey) is a tough issue. All kind of applications for any formal and statistical data for this study were rejected and only one set of raw data was obtained from one single hospital after three and a half months of intense effort. The Social Security Institution responded seven months after the applications for data acquisition and rejected the request on the basis of privacy of personal information. These raw data must be compiled and made ready for proper calculation.

There is no methodological study about the variables of this study. There are many variables those could change the calculation, some of which are age, gender, social status and comorbidities before and after a kidney disease etc. The calculation is based on the costs of transplantation from a deceased and a living donor without any comorbidity under regular hospitalization.

The purpose of this study is to make a contribution to the health literature by calculating the costs and benefits of kidney transplantation. Although there is (a) system, there is also (a) system failure thus current system(s) is (are) insufficient in terms of reducing the prolonging waiting list(s). Therefore this thesis proposes an alternative system that would help increase kidney donations and transplantations. The proposed system would also heavily suppress the black market that abuses poor people.

Advancements and achievements in medicine and medical technology intend to prolong the life time of human beings. Following the invention of immunosuppressive drugs in late 1970s, success ratio in organ transplantation increased significantly which is considered as an ultimate realization of extending the life span. Today, availability of transplantation of various types of organs brings hope for patients. However the shortage in supply of transplantable organs, and especially of kidneys, is the principal problem and the difference mentioned at the very beginning of this Introduction keeps growing every day. The main sources for transplantable organs are donated organs: either living or deceased donations. After World Health Organization (WHO) banned selling and buying organs/organ trading (WHO: 1984), transplantable organs are only available through altruistic donation.

This thesis begins with the historical development of organ transplantation. Transplant surgery is mentioned and discussed in many historical sources (Howard et al.: 2012, Carrel: 1902) and the first successful organ transplantation was achieved by Yurii Voronoy

3

in 1936 (Voronoy: 1937). After the invention of immunosuppressants medical surgeons achieved to successfully transplant kidney from human to human. This success made possible the transplantation of other organs like liver, lung and tissue.

The increase in number of organ transplantations together with an emerging shortage of transplantable organs gave rise to ethical and moral concerns. Therefore, necessity and requirement brought about legal acts for allocation, grafting and donation of transplantable organs. Brief information regarding the development and history of the legal status in Turkey and in the world is given for convenience in this thesis.

Almost 70% of all transplanted organs are kidneys all around world (IRODat: 2014) therefore the study focuses specifically on kidney transplantation. Diagnosis of the kidney disease, symptoms and stages those end with transplantation are important to understand the shortage in kidneys therefore the definition of Chronic Kidney Disease (CKD) is given as the focal point.

Chapter 5 examines the donation systems in the world. These systems differ with respect to their objections so they need to be explained with their benefits. Each system has its own perspective and the governments enact these regimes according to these perspectives. These systems are classified into three main groups: opt-in system, opt-out system and monetary incentive. Each one of these systems has dimensions for living and deceased donation. Another system for allocating donated organs is pairwise kidney exchange and/or NEAD Chain. This system does not focus on increase-in-donation however makes allocation more effective.

Chapter 6 examines kidney allocation system with respect to its economic dimension(s). The determinants of supply and demand together with the effect of monetary incentive on supply and demand are examined.

Monetary incentive could be effective for increasing organ donation, especially in poor countries. Black-market for organs and transplant tourism is explained in Chapter 7. According to reports generated by WHO; almost 5 to 10 percent of kidney transplantations are performed by organ trafficking every year (Budiani-Sabeni and Delmonico: 2008). At this point it is crucial to understand the driving factors of illicit organ transplantation. These factors could be traced down to their root causes those might enable stopping the

4

abuse of people suffering under challenging conditions since organ traffickers take advantage of these conditions by offering these people a covenant to change their lives. Legal regulations are the main factors for increasing (or decreasing) the donation rates and allocation of grafted organs. This thesis proposes a system for increasing the donation rates therefore the structure of legal regulations and amount of kidney transplantation and donation in Turkey should be known and hence these are discussed in the following sections.

Chapter 8 gives a brief documentation of legal regulations in Turkey and Chapter 9 compares the change in donation and transplantation in numbers from 1990’s to present. One of the primary pillars is the selection of the recipient and allocation of the grafted organ. The actual system in Turkey is examined in section 9.3 in light of the preceding discussion.

The primary objective of this thesis is to make a cost-benefit analysis of dialysis and kidney transplantation in Turkey. This requires the calculation of the costs of dialysis and transplantation. Government pays a standard amount for each dialysis session that is recalculated every year on the basis of annual inflation rate. However gathering reliable data for the costs of transplantation is almost impossible because of the restrictions of the Act about confidentiality of personal information. The data utilized in this study are obtained by special permission from Atatürk Education and Research Hospital. These data are the key component of the analysis. Having made the cost-benefit analysis of kidney transplantation, costs of kidney transplantation versus dialysis in Turkey is compared. In addition, similar analyses from different countries in academic literature are examined. A sensitivity analysis with variables of donation rates, waiting-list and number of transplantations is given in section 11.1.

One other primary pillar of alternative system proposed in this thesis is a monetary incentive. The factors affecting the amount of a monetary incentive and its (likely) effect on the number kidney donation is discussed in Chapter 12 with another sensitivity analysis. The amount payable is considered as a compensation of losses of donor but not as a price for a kidney. This could be perceived as the commodification of (a) kidney. In altruistic donation; recipient, surgeons, hospital and even the government (or insurance system) has a stake however the donor gets only moral relief which may not be enough to encourage

5

the potential donors to donate. At this point, the amount of a monetary incentive could be a motivator to encourage such potential donors.

Chapter 13 focuses on one pillar of this thesis which is the proposal of an alternative donation system. This proposal is divided into following three subtitles: opt-out regime, government monopsony and monetary incentive. The benefits and arguments in the academic literature of each subtitle are examined in section 13.2.

There are ongoing debates about all of the regimes and proposals. As the organ shortage increased in last few decades, the effect of monetary incentive is broadly discussed despite all its errors, transgressions and misdeeds. A unique example of where this system is applied is Iran that is (relatively) successful in terms of handling the waiting-list issue. This success draws the attention of alternative system researchers. Chapter 13 also takes into consideration the debate mentioned in the preceding paragraph. The data taken from Atatürk Education and Research Hospital are very detailed and are a bit complicated. The data set is given in Appendix 3 and can be obtained from the author.

6

2. HISTORICAL DEVELOPMENT OF ORGAN TRANSPLANTATION

The ancient history comprises myths and artworks giving reference to transplantation. Hindu texts dating back to 2500-3000 BC contain stories about grafting (Howard et al.: 2012, Carrel: 1902). Transplantation is also mentioned in Chinese legends. In one of these, Pien Chao transplants the heart of a man to change his spirit who he considers spiritually weak (Marino, Cirillo: 2014, p.2). The Bible also includes some stories mentioning transplantation. The story named “the miracle of the black leg” in Christianity is a valuable example for transplantation in historical and religious records together with its core argument that the leg transplanted was black conveys a universal message; religion is not restricted with races and color of the skin (Howard, Cornell: 2012). According to the story, the custodian of the church is crippled with an ulcerous leg. In his dream, two saints appear in his room holding medical instruments and they consult each other to replace his leg with that of an Ethiopian man that had died the day before1. In 1883, Theodor Kocher

transplanted a thyroid tissue into a patient who suffered from radical thyroidectomy. For his study about transplantation he won the Nobel Prize in 1909. In the 18th century, John

Hunter made some transplantation experiments on animals. On December 7th, 1905,

Austrian physician Eduard Zirm performed transplantation to a human which was recorded as the first successful (cornea) transplantation from human to human (Armitage, Tullo and Larkin: 2006). Mathieu Jaboulay and his team including Carrel worked on an improved method of vascular suturing in Lyon (Carrel: 1902). Alexis Carrel transplanted a kidney from a dog in France (Carrel: 1905). When he moved to the U.S., aviator Charles Lindbergh and Dr. Carrel, recipient of the Nobel Prize in 1912 for Physiology and Medicine for his work in vascular surgery invented the Carrel-Lindbergh perfusion pump which led to the development of the heart-lung machine2 (Howard, Cornell: 2012). By the beginning of the 20th century successful transplantation of skin and cornea was already available. Dr. Harold Neuhof wrote his book in 1923, Transplantation of Tissues, about transplantation of skin, cornea, fascia, muscles, nerves, bones, teeth, blood vessels, ovaries, parathyroids, adrenal glands, testises and pancreases (Neuhof: 1923). In 1925, Dr. Serge Voronoff wrote the Rejuvenation by Grafting, about testicular transplantation to older men those with loss of libido or sexual dysfunction (Varonoff: 1925).

1http://www.theroot.com/miracle-of-the-black-leg-honorable-act-or-exploitation-1790874834 2http://americanhistory.si.edu/collections/search/object/nmah_688713

7

The first kidney transplantation was performed by Russian doctor Yurii Voronoy in 1936 (Voronoy: 1937). Transplantation was performed from a deceased donor into the body of a young woman with a mismatch of blood-types (Hamilton: 1984, p. 289-294). Although the patient survived only for two days, this was the first successful transplantation recorded. The first modern kidney transplantation was performed in 1947 by David Hume from a deceased body into a young woman (Diethelm: 1990, p. 505-520). Between 1951 and 1953, Hume and his colleagues performed 9 transplants however it had not been possible to achieve a long-term survival for any of the recipients (De Vita MA: 1993, p. 113-129). In 1952, kidney transplantation was performed by a group of French doctors from a mother into his son. The recipient in this case survived only 22 days before the organ was rejected (Linden: 2009, p. 165-184). In 1954, the first successful transplantation was performed by Joseph E. Murray and his team from two identical twins after which the recipient lived 8 more years whereas the donor twin lived for 56 more years (Hakim and Papalois: 2003 p.92, Tinley: 2003). This successful surgery raised the question whether it was a must in order to perform transplantation from twins, since the use of immunosuppressives were not needed. If it had been considered that transplantation was possible only between twins most probably the need for immunosuppressives was never going to be realized.

The major problem that the physicians were facing was the fact that transplantation was not possible without the same DNA structure. Therefore, kidney transplantation had not been a treatment up until the development of immunosuppressive drugs. Experiments were made on animals based on cortical hormones; however the modest immunosuppressive effect of cortisone was achieved in early 1950s. In the late 1950s total body irradiation and allograft bone marrow rescue attempts were made in Paris, Boston and other institutes (Hamilton: 2008, p.5). In 1959, experiments about using 6-mercaptopurine on kidney transplant operations were made (Hakim and Papalois: 2003) which had success for immunosupprant use. In 1960 scientists started to use immunosuppresants on patients however the dosage presented a problem. 6-mercaptopurine was the ancestor of the main drug, azathioprine. The latter drug was more effective and useful than the other one. The combination of azathioprine and prednisone was making transplantation available. From 1958 to 1961, different variations of immunosupresives such as 6-mercaptopurine (6-MP), methotrexate and other anti-cancer drugs were used. David Hume, Roy Calne, Murray and

8

other surgeons tried to find and assess the proper formulation and dosage in clinics in London and Boston. Küss and colleagues succeeded on their studies regarding the survival of a non-related kidney patient (Küss et al.: 1962). This is known to be the first success of chemical immunosuppression.

12 patients were transplanted with azathioprine; except one, the others did not survive after the surgery (Murray et al.: 1960). In 1962, Dr. Murray performed the first successful kidney transplant from a deceased donor. The donor had several head injuries and transplantation was approved by the chairman (Howard et al.: 2012). This permission brought about the issue for an approval. Legal and ethical considerations begun almost at the same time with early successful operations. Moreover, Murray declared this problem as it first hashed out (Murray: 1976).

In 1963, Thomas Starzl performed the first liver transplantation and the same year James Hardy performed the first lung transplantation. The applicable combination of steroids, prednisolone and azathioprine was formulated (Starzl: 1978), survival rates had increased and an optimistic era had started by 1966 (Murray: 1976). Furthermore, the first successful pancreas transplantation was performed in 1966 by Richard Lilehei and again the first successful heart transplant was performed by Christian Barnard in 1967.

2.1. Definition of Brain Death

Until the first successful transplantation which was performed in Belgium with the approval of the chairman, asking for permission had not been something ever considered before. This successful surgery had been the precursor of the possibility of transplantation. But how was it going to be possible for surgeons to transplant other organs like lung, heart, cornea rather than liver and kidney based on the fact that if someone is dead, his/her heart wouldn’t beat and organs wouldn’t function, and thus not be available for transplantation. The achievements between 1950s and mid-1960s faced physicians, ethicists, philosophers, government officials and religious leaders with the question on the definition of “death”

9

(Howard: 2012). The accepted traditional definition of “death” was the cessation of breathing and “irreversible3” circulation (Howard: 2001).

At this point, the definition of death becomes much more critical. As long as there are conflicts about the definition, some other arguments based on ethical and legal issues would eventually arise. Although there is a legal definition, there is also an argument going on. The current definition and classification regarding the distinction between dead and alive gives an opportunity to graft organs while they are functioning.

Wertheimer et al. were the first to characterize death in 1959 by defining the failure in nervous system that was treated by artificial respiration (Wertheimer: 1959). The term “beyond coma” that defined an irreversible state of coma and apnea was used by Mollaret and Goulon. This was the first attempt to define “brain death” however the issue of continuing heartbeat was still not resolved (Mollaret, Goulon: 1959). Advancements in biomedical technology gave raise to sophisticated intensive care unit (ICU) techniques and mechanical ventilators. This helped pave the way to the definition of brain death.

In 1968, Symposium on Transplantation was held in London with the attendance of physicians, lawyers and others concerned on ethical and legal issues of transplantation. An extensive description of brain death was given in this symposium for the first time (Machado: 2005). The Ad Hoc Committee gathered to define brain death in London in 1968. The very first problem was to determine the characteristics of a non-functioning brain (Beecher et al.: 1968). Accordingly, the following conditions had to be diagnosed for a brain-dead individual:

1. unreceptivity and unresponsivity 2. no movements of breathing 3. no reflexes

4. flat electroencephalogram

This was a great movement to stand the medical declaration on a legal ground. There are three major results to confirm brain death: a) coma and unresponsiveness, b) absence of

3 Irreversible means that breathing and circulation cannot be functioned again by ventilators or any other

10

brainstem reflexe,s c) apnea (Morris, Knechtle: 2014, p.:94)4. This declaration had been the pioneer of legal status.

The importance of the definition comes into prominence for the satisfaction of conditions under which organs can be grafted. After cardiac death, the majority of the transplantable organs stop functioning. On the other hand, as one individual is defined brain-dead, most of his/her non-vital organs would keep functioning; however the body depends on a life-support machine to keep those organs functioning. Increasing number of transplantation shows that there is a great demand on kidney (and other organs) and having the definition of death re-defined from “cadaveric” to “brain” resulted with a significant increase in the number of transplantable organs. Between 1997 and 2007, approximately 53,000 people on average died from traumatic brain injuries every year in the U.S. (Coronado et al.: 2011). These figures increase every year because of motorcycle and car accidents, suicides and various other reasons.

There are many examples about revival after “irreversible coma” and those who oppose this idea keep debating on these examples. Ethical arguments are based on “the right of unplugging the machine”, “human dignity”, “integrity of the human body” and other humanitarian concerns, however these issues are beyond the scope this thesis.

2.2. History of the Legal Status about Organ Donation

In 1968, the Ad Hoc Committee of Harvard Medicine School published a report to examine the Definition of Death. This was ground-breaking because this definition enabled surgeons to perform actually all types of transplantations. Sequentially various states and countries accepted this definition as a medical law. The same year, the Uniform Anatomical Gift Act stated that an 18 year-old person could donate his/her organs after his/her death. Finland was the first country that accept brain death and Kansas was the first state that legalized brain death in 1970 in the U.S.

The improvements in medical care, intensive care and immunosuppression were promising. Although the use of immunosuppressives had increased the success ratio in transplantation surgeries from deceased donors, they did not help realize the expected

4 For more information about the medical diagnosis of brain death and cardiac death see; Morris, Knechtle,

11

increase in survivals after transplantation. The problem was solved by a successful clinical application of HLA-DR (Ting, Morris: 1978).

Seeking for different methods for increasing the number of donations was raised intensely throughout 1970s. The United Kingdom was the first country that introduced the Kidney Donation Card in 1971. The American Bar Association established brain death as a legal and medical fact in 1975. In 1976, France initiated an opt-out policy that assumed everybody as a potential donor unless declared otherwise before death. The Uniform Determination of Death Act drafted in 1978, recognized brain death as a legal concept and was approved at the National Conference of Commissioners on Uniform State Laws. The United States legalized brain death upon the approval of the Uniform Determination of Death Act through a landmark report issued by the Presidential Commission in 1981 (Howard: 2001). It defined death as an irreversible cessation of circulatory and respiratory functions or cessation of all functions of the entire brain, including brain stem. “Guidelines for Determination of Death” was published by this committee and now it is effective in all states. It is still being periodically revised by the American Academy of Neurology.

The act about brain death granted surgeons the required legal ease for transplantation however declaration of “legal death” was another issue. In some states, examination and

Figure 1: Distribution of organ donation from brain death and cardiac death in the U.S. Source: Linden (2009)

12

declaration of only one physician was deemed sufficient to confirm brain death whereas in some others more than one physician was required.

The clinical and medical innovations enabled better techniques for preservation. Total body hypothermia of the living kidney donor during surgery was something already achieved in the early 1960s. Initial attempts for preserving the kidney up to 48 hours5 were unsuccessful. Later on, scientists begun to apply hypothermic methods on human kidneys (Starzl: 1963). It became possible to preserve and transport the organs of a dead body in a short time and for short distances. Owing to improved techniques in time, preservation and transportation for far more distances became available. Until James Southard and Folkert Berzer in the University of Wisconsin in 1980s developed a proper formula, various flush solutions6 were tried. This and such medical and pharmaceutical achievements made far more things possible; transplantation of different organs from a dead body for more than one recipient at more than one single facility was possible, however there had raised far more responsibilities imposed on the stakeholders.

Developments in preservation techniques gave rise to the establishment of many organ banks those functioned almost in the form of organ procurement agencies. The New England Organ Bank founded in early 1970s served for more than 10 transplant programs. At the early stages of transplantation era, an organization for organ allocation was not needed. Almost all of the transplanted organs were form living donors. Transplant centers were at a limited number and donors and patients had to be at the same center. However, two important achievements those were advancements in preservation and new advancements in tissue typing (Williams et al.: 2004), made allocation organization necessary together with the principles of the legalization of allocation. In addition, increase in the number of transplantations, demand and donations forced regulatory authorities for a system to organize procurement policies. Definition of “brain death” was the first step among the early attempts. However there were still other issues those had to be clarified:

Grafting and preservation of organs donated,

Transportation of grafts into proper distances (if needed), Classification of patients according to their needs and urgency,

5 Ex vivo sanginous and asangunious artificial pulsatile perfusion techniques.

6 Collins solution, Euro-Collins solution and University of Wisconsin solution were some of these flush

13 Allocation of donations on a fair basis.

The innovations in matching the donor and preservation of the organ up to 12 hours made formal regional organ sharing programs necessary (Williams et al.: 2004). The Los Angeles Transplant Society and the Regional Organ Procurement Agency of Southern California were established in 1967 those were the first establishments recorded for kidney distribution (Howard et al.: 2012, p. 11). In 1969 an organ sharing program, South-Eastern Regional Organ Procurement Program (SEROPP), was founded under the leadership of David Hume and Bernard Amos with the participation of 8 hospitals in 4 states (Teresaki et al.: 1971). Dr. Paul Terasaki at UCLA expanded this organization to 61 West and Midwest transplant centers. SEROPP became an independent non-profit organization called South-Eastern Organ Procurement Foundation (SEOPF) incorporated with an online system for matching and sharing organs for transplantation (Ferree, Stearns: 1996). In 1977, this system gave rise to the United Network for Organ Sharing (UNOS), a computer system for registering potential patients, donors and sharing kidneys of non-SEOPF and SEOPF centers (Pierce: 1996, pp. 1-5). This kind of a distribution system enabled a larger sharing network, ease of transportation and decreased costs. This computer system was transformed into establishing a 1-year pilot Kidney Center program that was funded by American Kidney Fund. The success of this pilot program led to a country-wide organization which was funded by the Health Care Financing Administration in 1984 (SEOPF Newsletter: 1994, pp. 5-9). By contract with The Health Resources Services Administration of U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, the UNOS program started to serve as the Organ Procurement and Transplant Network (OPTN). Next year, UNOS separated from SEOPF with its computer facilities, personnel and other units (Pierce: 1996).

As computer technology became more sophisticated, the UNOS program evolved into the Organization for Transplant Professionals (NATCO) funded by Richard King Mellon Foundation that enabled a 24-hour alert system. Payment was an important issue within this process. Since transplantations were experimental, all the costs were financed by hospitals (Prottas: 1989). Kidney transplantations were expensive operations. Non-profit organizations for transplantation program were established which are considered the origins of independent Organ Procurement Organizations (OPOs). An amendment in the Social Security Act in 1971, guaranteed Medicare for recovery costs (Howard et al.: 2012).

14

Before the End Stage Renal Disease Act came into force, patients had to pay the costs, however most of them couldn’t afford the dialysis, transplantation and organ procurement. Besides, many insurance policies were not covering the costs (Howard: 2012). The Social Security Act which was repeatedly amended in three decades extended the coverage and enabled payment of transplantation and/or dialysis costs by the help of social security systems.

Figure 2: Major legislative and regulatory landmarks of organ donation and transplantation (U.S.) Source: Howard et al. (2012)

15

Table 1: Major legislative and regulatory landmarks and other requirements affecting organ procurement organizations (OPOs). Source: Howard et al. (2012)

1. 1935 Social Security Act: federal forerunner of the acceptance of public responsibility for the aged, needy, deprived and handicapped.

2. 1965 Medical/Medicare Laws, titles XVIII and XIX of the Social Security Act.

3. 1968 Uniform Anatomical Gift Act: legalizes organ and tissue donation for transplantation. Gave adults the right to donate their bodies or organs without subsequent veto by others. Passed by the Conference of Commissioners on Uniform State Laws as a suggestion for individual states.

4. 1968 Report of the Ad Hoc Committee of the Harvard Medical School to examine the definition of the brain death: defines brain death.

5. 1969 Kidney disease and its control placed under the aegis of the Public Health Services of the Department of Health, Education and Welfare (HEW) – Forerunner of the Department of Health and Human Services (DHHS). The Public Health Service launches kidney transplantation program to maintain computerized donor/recipient matching program. Contract with University of California, Los Angeles involved 7 deceased kidney procurement contracts.

6. 1970 Kansas is the first state to pass the brain death legislation. 7. 1971 Uniform Anatomic Gift Act: establishes legality to donor cards. 8. 1971 All states had adopted the Uniform Anatomic Gift Act.

9. 1972 End Stage Renal Disease Act (PL 92-603): Social Security Amendment – provides Medicare coverage for kidney failure, including dialysis and kidney transplantation, and pays for organ procurement.

10. 1973 (38 Federal Register p. 17, 210): interim regulation for the financing organ acquisition. 11. 1976 (41 Federal Register p. 22, 502): final rules for the financing of organ acquisition.

12. 1976 Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) initiated analytic effort to improve the performance of the organ procurement system—sought to apply methods of epidemiology to organ donation and acquisition. Tried pilot programs in Atlanta, Georgia, and Kansas City, Missouri. 13. 1976 Uniform Death Act: National Conference of Commissioners on Uniform State Laws.

14. 1978 President’s Commission for the Study of Ethical Problems in Medicine and Biomedical and Behavioral Research: expands studies of brain death and informed consent.

15. 1980 President’s Commission for the Study of Ethical Problems in Medicine and Biomedical and Behavioral Research drafts the United States Uniform Determination of Death Act.

16. 1981 Uniform Determination of Death Act approved. Common law basis for determining death. Defines death as irreversible cessation of circulatory and respiratory functions, irreversible cessation of all brain functions including the brain stem.

17. 1984 National Organ Transplant Act (NOTA) (Public Law 98-507). OPOs must be members of the Organ Procurement and Transplant Network to receive payment from Medicare. Established the Organ Procurement and Transplant Network, prohibited buying and selling of organs, established the Task Force on Organ Transplantation.

16 Table 1 continued

18. 1986 Task Force on Organ Transplantation report (task force was created by NOTA): recommended health professionals identify prospective donors and notify OPOs, hospitals adopt routine inquiry/request protocols, that the Joint Commission on Accreditation of Health Care Organizations (JCAHO) adopt a standard that required affiliation with an OPO as well as policies and procedures to identify prospective donors and give donation opportunity to the next of kin, that the Defense Department and Veterans Administration require their hospitals to adopt required request protocols, that the Health Care Financing Administration (HCFA) require hospitals to have routine request protocols as a condition of participation. It also recommended that OPOs and procurement specialists be certified and that only a single OPO be certified in “any standard metropolitan area”; “that each donated organ should be considered a national resource and be used for the public good”; and a governance structure for independent OPOs, which was incorporated into federal guidelines as a condition for receiving a supporting federal grant.

19. 1986 Omnibus Budget Reconciliation Act (Public Law 99-509, Section 9318) Required Request legislation: families of potential deceased donors had to be asked whether they wanted to donate their loved one’s organs for transplantation. Gave the HCFA the authority to certify OPOs.

20. 1987 Revision of the Uniform Anatomical Gift Act: prioritized decedent’s wishes, prohibited organ sales, required hospitals to institute a required request policy.

21. 1987 Omnibus Budget Reconciliation Act (Public Law 100-203): further defined laws governing OPOs.

22. 1987 Uniform Anatomic Gift Act prioritized descendant’s wishes for donation over family wishes, requires hospitals to inquire about organ donation.

23. 1988 DHHS, HCFA, Medicare and Medicaid programs approved regulations implementing the 1986 Omnibus Budget Reconciliation Act affecting OPOs and other organ procurement protocols, (42 CFR Parts 405, 413, 441, 482, 485, and 498 Fed Register 1 March 198; 53 (40): 6526-6551).

24. 1988 JCAHO, now renamed The Joint Commission, requires hospitals to identify potential donors and refer them for organ procurement.

25. 1988 Transplant Amendments (Title IV of Public Law 100-607): further defined OPO oversight. 26. 1990 Transplant Amendments (Public Law 101-616)–further defined OPO oversight. Further defined

HCFA’s authority to certify OPOs.

27. 1993 Public Health Service Act (42 U.S.C. section 264, is the authority for the Food and Drug Administration’s Interim Rule for Human Tissue Intended for Transplantation. (Federal Register 14 December 1994; 58 (238):65514).

28. 1996 Organ Donation Insert Card Act, authorizes mailing information about organ and tissue donation with income tax refunds.

29. 1998 National Conditions of Participation (DHHS).

30. 1998 Health Omnibus Programs Extension–OPOs required to obtain 50 actual donors per year, requires OPOs to test donors to avoid spreading infection.

17 Table 1 continued

32. 2003 Health Research and Services Administration announces the beginning of the Collaborative efforts to increase the number of organ transplants and reduce deaths on the waiting list.

33. 2003 Health Research and Services Administration announces the beginning of the Collaborative efforts to increase the number of organ transplants and reduce deaths on the waiting list.

34. 2006 Uniform Anatomical Gift Act–further revision in light of new federal regulations. 35. 2007 DHHS–CMS–Final Rule for Transplant Centers.

36. 2009 Uniform Anatomical Gift Act–addresses gift of the donor, first person consent, what to do when there is no next of kin.

2.3. History of Organ Transplantation in Turkey

The modern transplantation history dates back to early 1960s in Turkey. Despite various unsuccessful attempts, first successful transplantation was performed in 1962, after the invention of immunosuppresives. Transplantations in Turkey began very short after the first transplantation surgeries abroad. In 1969, there were two unsuccessful attempts of heart transplantation in Ankara and in İstanbul. M. Haberal and his team made experimental studies on animals in Ankara in 1972. First experimental liver transplantation surgery was performed on pigs and dogs in early 1970s (Haberal et al.: 1972). First living-related kidney transplantation was also performed by this team at Hacettepe University in 1975. Another milestone for Turkey was the deceased donor kidney transplantation which was performed in 1978 (Haberal et al.: 1988). This kind of a kidney donation was legally restricted therefore the kidney was supplied through Eurotransplant (Karakayalı and Haberal: 2005). Legal loopholes are a combination of legal, ethical, medial, social, psychological, technological, economic and religious aspects of transplantation and they need to be systemized by law. These perspectives are examined in the following chapters of this thesis.

Legalization issues were the main problem for transplantation. The supply of organ has two sources: either dead or living donors. At the beginning of experimental transplantation surgeries, supply of organs from deceased donors were “cardiac death” donors since the accepted definition of “death” was cardiac death. After the recognition of definition of brain death, a broader capability was enabled for grafting organs from deceased donors. As transplant surgeries advanced, need for regulations in organ transplantation arose. In 1979, the 2238 numbered law about “organ and tissue recovery, preservation, inoculation and

18

transplantation” was enacted. This law was basically about recovery, storage, grafting and transplantation of organs and tissues and had 4 main chapters; general provisions, organ recovery from a living donor, organ recovery from a deceased donor and penalties (Karakayalı and Haberal: 2005). The first local renal transplantation was performed the same year in July (Haberal, Öner et al.: 1984). Religious concerns were an important issue in order to persuade citizens to become organ donors. After 2238 numbered law was enacted, as a result of Haberal’s initiatives, the Supreme Council of the Directorate of Religious Affairs issued a fatwa in 1980 stating that there are no constraints and restrictions regarding organ donation and transplantation (Moray et al.: 2014).

Table 2: Some articles from Turkish Law on harvesting, storage, grafting and transplantation of organs and tissue. Source: Haberal and Karaali (2005)

Turkish Transplantation Law #2238, on the harvesting, storage, grafting, and transplantation of organs and tissue (June 3rd, 1979)

The buying and selling of organs and tissues for a monetary sum or other gain is forbidden.

Harvesting organs and tissues from persons under the age of 18 or those who are not of sound mind is forbidden.

In connection with enforcement of this law, the cause of medical death is established unanimously by a committee of four physicians consisting of one cardiologist, one neurologist, one neurosurgeon and one anesthesiologist by applying the rules, methods and practices that the level of science has reached in the country.

The physician who will perform the transplant surgery may not be a member of the group that pronounced the donor as dead.

Turkish Transplantation Law #2594 (January 21st, 1982)

In the case of the aforesaid persons, where next of kin do not exist or can be located, and the

termination of life has taken place as a result of accident or natural death, provided that the reason for the death is not in any way related to the reason for the suitable organs and tissues can be transplanted into persons whose lives depend on this procedure without permission from the next of kin.

In 1980, The Turkish Organ Transplantation and Burn Treatment Foundation was established and the first organ donation cards were printed. In 1982, new articles regarding the issue came into force with the enactment of the 2594 numbered law. In 1987 Middle East Society of Organ Transplantation (MESOT) was established with the contribution of eight Middle Eastern countries. After in 1990, Turkish Organ Transplantation Society was founded and was later associated to MESOT. In addition to organizing biennial congresses,

19

MESOT is publishing its official journal “Experimental and Clinical Transplantation Journal” since 2003 (Akbulut, Yılmaz: 2014).

In 1988, the first liver transplantation from a deceased person was performed by Haberal and his team (Haberal et al.: 1992). History of Turkish liver transplantation is divided into three stages by Dr. Sezai Yılmaz: initial stage (1988-1996), development stage (1997-2001), rise and spread stage (2002-2014) (Akbulut and Yılmaz: 2014). National organ sharing program was initiated in 1989 and National Coordination Center was established in 2001 by Ministry of Health which involves 9 coordination centers on the basis of geographic location, population, allocation and transplantation demand. The “Turkish Organ and Tissue Information System” was initiated to coordinate and distribute organs properly in a fair manner among the recipients and transplantation centers. Ministry of Health initiated “the national organ and tissue transplantation coordination system in 2011 via a directive. Another milestone was the first international paired kidney transplantation that was performed in May, 2013 (Tuncer et al.: 2015).

Today, organ transplantation is an effective, professional and expanding organization in Turkey under the leadership of Ministry of Health. Coordination Centers are well-organized and almost all potential donors are carefully considered with computer based systems. Although donation rates are insufficient (donation rates will be examined in Chapter 4), Turkey is the leading country in the world in terms of living kidney donation rates.

20

3. WHAT IS CHRONIC KIDNEY DISEASE (CKD)?

Tissues, bones, eyes, lungs, liver and even heart are transplantable organs however all of them require deceased donors with the exception of kidney and liver. Especially kidney transplantations yield very effective results. Most of the transplantation surgeries are kidney transplantations. Besides, operations are relatively easier when compared to transplantation of other organs with a minimum damage to donor which is acceptable for any potential donor. Making a decision regarding the urgency of a recipient’s need for transplantation is a delicate issue. Patients move towards the end-stage renal disease (ESRD) in phases, thus recognition of the definition of CKD is crucial.

The functions of kidney are cleaning the blood from toxic matters, balancing liquid equilibrium and blood pressure and secreting hormones etc. An agreed upon definition of kidney disease helps physicians make diagnoses. KDIGO (Kidney Disease Improving Global Outcomes)7 is an independent charity organization which is managed by the National Kidney Foundation in the U.S. KDIGO organizes conferences all over the world with the attendance of well-known nephrologists and publishes reports and guidelines which include every aspect of CKD. Besides, KDIGO definition on CKD is accepted globally. The first of International Controversies Conference was held in Amsterdam about the “Definition and Classification of Chronic Kidney Disease” in November 2004. The goals of this conference were to 1) provide a clear understanding to both the nephrology and non-nephrology communities of the evidence base for the definition and classification recommended by Kidney Disease Outcomes Quality Initiative (KDOQI)8, (2) develop global consensus for the adoption of a simple definition and classification system, and (3) identify a collaborative research agenda and plan that would improve the evidence base and facilitate implementation of the definition and classification of CKD9.

7www.kdigo.org KDIGO is a global organization developing and implementing evidence based clinical

practice guidelines in kidney disease.

8 K/DOQI is an initiative held in the first KDIGO conference.

9 http://kdigo.org/home/conferences/definition-and-classification-of-chronic-kidney-disease-in-adults-worldwide-2004/

21

Topics were definition and classification of CKD, Glomerular Filtration Rate (GFR) and assessment/measurement of albuminuria and proteinuria which are important to classify the level of kidney disease. (Levey, Eckardt et al.:2005).

CKD is classified either by a reduced GFR or kidney damage indicators like proteinuria, hematuria or biopsy etc. Reduced GFR must be < 60 mL/min/1.73 m2. At least three samples must be taken in a three month-period and these samples have to be positive for protein or albumin.

Table 3: Five stages of chronic kidney disease as defined by KDOQI guidelinesa

Source: Brosnahan, Fraer (2010), Weiner ( 2007)

CKD Stage GFR Description Action Plan

Stage 1 ≥ 90 mL/min/1.73 m2 Kidney damage,

Normal GFR

Diagnosis, treat comorbidities, slow progression

Stage 2 60 – 89 mL/min/1.73 m2 Kidney damage, mild

decreased GFR Assess progression

Stage 3 30 – 59 mL/min/1.73 m2 Moderate CKD Evaluate and treat complications

Stage 4 15 – 29 mL/min/1.73 m2 Severe CKD Prepare for kidney replacement

therapy

Stage 5 < 15 mL/min/1.73 m2 Kidney Failure Kidney replacement therapy

aGFR, glomerular filtration rate; KDOQI, kidney disease outcomes quality initiative

Another criterion for diagnosing the disease is about albuminuria is as follows: Table 4: Albuminuria categories of CKD

Albuminuria categories in CKD ACR (approximate equivalent)

Category AER

(mg/24 hours) (mg/mmol) (mg/g) Terms

A1 < 30 < 3 < 30 Normal to mildly increased

A2 30 – 300 3 – 30 30 – 300 Moderately increased*

A3 >300 >30 >300 Severely increased**

Abbreviations: AER, albumin excretion rate; ACR, albumin-to-creatinine ratio *Relative to young adult level.

** Including nephrotic syndrome (albumin excretion usually > 2200 mg/24 hours [ACR > 220 mg/g; > 220 mg/mmol]). (Levin et al.: 2013)

22

There are some other important complications that influence the management of patients and treatments (Said et al.: 2015):

a. Volume overload b. Metabolic acidosis c. Hypertension d. Anemia

e. Mineral and bone disorders f. Uremia

g. Dyslipidemia h. Infection

This thesis focuses on the economic perspectives of kidney disease, therefore complications and other related issues will not be discussed further.

3.1. Initial Symptoms of CKD

The prevalence of CKD is estimated from national surveys and health statistics (Brosnahan and Fraer: 2010). The results are classified and published by some researchers and initiatives such as K/DOQI. Coresh et al., surveyed the U.S. data between 1994 and 2004 and reached that obesity, diabetes, hypertension and aging are among the responsible factors increasing the prevalence of CKD (Coresh et al.: 2007). Similar results apply for researches from various other countries. Prevalence rate of CKD in people older than 64 is 13% in Beijing (Zhang et al.: 2008), 16% in Australia (Chadban et al.: 2003) and 23% to 36% in U.S. (Zhang and Rothenbacher: 2008).

CKD can occur at any age, however the people in the following categories have a higher risk of CKD (Brosnahan, Fraer: 2010):

Diabetes type 1 and 2 Hypertension

Obesity

Senescence (older age) Hyperlipidemia

Family history of ESRD Cardiovascular disease

23

Progressive kidney disease has some cardiovascular (CV) co-morbidities and mortalities in which most of the death-resulted CV diseases are caused by ESRD (Astor et al.: 2008). American Heart Association states that CKD patients are ranked in the high risk categories for CV events (Sarnak et al.: 2003). Traditional risk factors are classified by the Framingham Heart Study10.

Figure 3: Cardiovascular disease in CKD

3.2. Diagnosis of CKD

The main objective for diagnostic studies of CKD is on the limits of GFR. There are some other diagnostic tests for CKD patients such as urinalysis, quantification of proteinuria, renal ultrasound. There are additional diagnostic tests on the following clinical situations:

Serologies for autoimmune diseases

Serologies for chronic infections (Hepatitis B, C, HIV etc.) Serum and urine protein electrophoresis and immunofixation Blood and urine cultures

Imaging studies for malignancy Kidney biopsy

10 The Framingham Heart Study is to identify the common factors and characteristics of Cardio Vascular

Disease over a long period in a large group of observations. For more information please visit

24

The information contained up until this paragraph aims to provide a brief history on the development of transplantation together with a comprehensive understanding of the diagnosis of kidney disease. However the core argument of this thesis is the identification of the economic dimension of transplantation, which requires a thorough understanding and recognition of the disease. The following chapters will concentrate on the core argument and examine different dimensions of transplantation.

25

4. SUPPLY AND DEMAND OF KIDNEY AROUND THE WORLD

The transplantation of organs has been a revolution for many incurable diseases. After the availability of transplantation, some critical diseases related to lung, liver and kidney become treatable and furthermore, curable. In the meantime, techniques of transplantation advanced and complications those occurred at the early stages were solved. One of the most serious problems, mismatch on blood and tissues, was eliminated by use of immunosuppressive. There has been a significant increase on renal graft survivals from deceased and living donors after medical and surgical inventions and improvements (Hariharan et al.: 2000).

Invention of immunosuppressive became the light of hope for patients in concern. In this context, kidney disease is of different importance. In most other diseases the patients generally don’t have much time for treatment and they need be interfered as soon as possible while CKD patients have a considerably longer time since a CKD patient could survive almost 13-21 years with this disease (Hariharan: 2001). This means that, the patient has 13-21 years of time for proper kidney transplantation. In this time period, if s/he could find an organ s/he would be cured. At this point, a very major problem comes up into the picture: kidney shortage, in other words; not every patient is having an opportunity to find a proper kidney.

Kidney transplantation could be performed either from a deceased or a living person. Physicians have enough time to prepare and make examinations on both patients and living donors but from deceased donors the case if different and time matters; that is in most cases there is not enough time for preparation and elimination of risks, especially that of chronic rejection. These risks can be immunologic or non-immunologic factors in origin and need to be eliminated.