Romani Studies 5, Vol. 28, No. 2 (2018), 157–94 issn 1528–0748 (print) 1757–2274 (online)

doi: https://doi.org/10.3828/rs.2018.7

A socio-spatial ground for the co-inhabitation of Roma

immigrants and the local poor

egemen yılgür

A socio-spatial ground for co-inhabitation

The term teneke mahalle, literally “tin can neighbourhood,” has been widely used since the Russo-Turkish War of 1877–1878 to describe a specific kind of urban fabrication, possibly poor and physically dilapidated, but also the sole, cheapest, and undoubtedly creative solution for the urgent housing needs of the poorest segments of the urban population. Even though these neighbourhoods were initially built at least partly by Muslim refugees, the Roma Mohadjirs,1 teneke mahalles also welcomed other poor members of society seeking informal, easily accessible, and safe housing in late Ottoman Istanbul. This study discusses the role of the Roma in the formation of teneke mahalles, and the socio-historical dynamics that directed the non-Roma poor to co-inhabitation with Roma in these teneke mahalles, and outlines their socio-economic and cultural profile from various respects on the basis of the two oldest examples of this socio-spatial and perceptual phenomenon in Istanbul.

Keywords: teneke mahalle, Gypsies (Kıbtî), Istanbul, poll tax (cizye), immigrant

Roma, the Russo-Turkish War of 1877–1878, Kurds, Armenians, Posha (Bosha), co-inhabitation, Ottoman neighbourhoods, poverty

Teneke mahalles were a regular phenomenon in the urban environment of the late nineteenth and early twentieth-century Ottoman capital, Istanbul, and gradually developed in other imperial cities. The expression refers to the physical features of the dwellings in these quarters, in that the majority of them consisted of waste materials like old boards and gasoline tins (teneke). The state and society, both external and internal observers, adopted the term, and it denominated the home towns of tens of thousands of people. Even though they had never been comparable in number to the gecekondu dwellers of the 1950s and later periods,2 the teneke mahalle came to the agenda of the state and society, partly as a threat but also an object of curiosity.

1. Immigrants. The original Turkish spelling is “Muhacir.” French and English authors of the nineteenth century generally rendered the word “Mohadjir.”

2. Gecekondu literally means “built at night.” This term was a public invention to denominate Egemen Yılgür is Associate Professor in the Department of Political Sciences and International Relations, Faculty of Social Sciences, Beykoz University. Email: tegemen1523@yahoo.com

The presence of this socio-spatial phenomenon has never been a secret in the local urban studies and sociology literature. However, although the Romani Mohadjir were occasionally mentioned in a few works, their role in the formation of teneke mahalles has not been an issue of investigation until very recent times. This paper investigates the role of the immigrant Romanies, who fled from former Ottoman territories in Bulgaria and Romania during and after the Russo-Turkish War of 1877−1878, the history of the earliest two teneke mahalles, and the mechanisms that directed the non-Roma poor to them, drawing upon archival sources,3 and to a lesser degree, oral records and narratives.

The Russo-Turkish War of 1877−1878 (or the “’93 war,” the local designation that indicates the date of war according to the Hijri calendar) was a turning point for the demographic structure of the late Ottoman Empire. Hundreds of thousands of Muslims migrated to the Ottoman capital, Istanbul, as they saw themselves under threat when the Russian army invaded the Ottoman cities that are in Bulgaria today. In 1886, the total population of the Ottoman capital was 851,527 (Çelik 1993: 37−9), and the number of immigrants from the beginning of the war in 1877 until 1879 was estimated to reach 378,804 (İpek 1999: 58). These numbers clearly reveal the relatively large size of the migrated population, and suggest its importance for the transformation of city life and local social conditions. Although this influx was initially over the dealing capacity of the Ottoman administration, the government recovered from the shock quickly, and developed a settlement policy that aspired to minimize potential threats and to take maximum advantage of the refugees as a labour force, particularly in empty farmlands.

The immigrants were welcomed freely in public buildings like mosques, schools, and municipal buildings when they came to the capital for the first time (İpek 1999: 58−68). Then the process of ultimate settlement started for many of them. The majority of the immigrants who had already been agricul-turalists in their former land were dispersed into the rural territories of the Empire. The details and the conditions of this campaign are explained in the

informal settlements in the 1940s (Zadil 1949) and, with the chain immigration of rural newcomers beginning in the 1950s, scholars more likely used it for the newcomers’ squatter settlements, and tend to distinguish them from the older teneke mahalles (Keleş 1972; Karpat 2016).

3. I have added related pieces of the transliterated documents in footnotes or the main text according to their length. It would be extremely difficult to make a direct translation for the Ottoman documents due to the complex and linguistically mixed nature of the language used in official correspondence. Nevertheless, I have tended to give the exact meaning of quoted pieces from each document whenever they are crucial for the understanding of context, and I have also kept the transliterated Ottoman text for Ottoman language experts and historians to check the reliability of my transliterations and interpretations. I used Devellioğlu (2013) for the Latin spelling standards of Ottoman words.

instructions about giving land to the immigrants who were agriculturalists (İskân olunacak muhacirînin zerrâ’ takımına arâzî i’tâsı hakkında ta’lîmât), dated 1879.4 Another group of the Mohadjirs would be given permission to settle in cities (İpek 1999: 161). According to the 36th clause of the instruction which regulated the settlement policy for the immigrants,5 dated 1878, the wealthy (ashâb-ı servet) and the craftsmen (ehl-i sanâyi), whose financial resources were sufficient to rent or buy a home and workplace, would be supported in this effort by the administration if they requested to stay in cities.6 However, there were others among the immigrants, who were probably not agricultur-alists even in their former cities and towns, such as Ruse (Rusçuk), Plovdiv (Filibe), and Lovech (Lofça), who did not accept the state’s offer to settle in agricultural areas. Furthermore, it was not possible for them to rent or buy houses or workshops like middle-class craftsmen and, therefore, they insisted on staying in the temporary settlements in the capital and subsisting there on familiar, menial jobs such as porters (hamallar), shoe-shiners (ayakkabı boyacısı), carriage drivers (arabacı), or draymen (yük arabacıları), etc.

The government tolerated their presence in the temporary settlements until 1883, and they lived without paying any price for housing during this period. They were seen as Muslim war victims by both the state and ordinary people. The war was a great trauma for the majority of Ottomans, and the Mohadjirs were living reminders of the lost territories. This perception about the Mohadjirs allowed them to extend their stay in the free public buildings. However, 1883 was a turning point for them, in that the majority of agricul-turalist and wealthy Mohadjirs of the first-wave immigrants were already settled in rural areas or in the cities, and those remaining in the public buildings were largely the poorest segment of all. The government then tried to evict them and to find a method for resettlement. They were given two options: they could either go to the rural areas or surrounding cities, or, if

4. Başbakanlık Osmanlı Arşivleri (The Ottoman Archives of the Prime Ministry). Y.PRK. KOM.2.13.1.2. 3 Muharrem 1297 (17 December 1879).

5. “Bu kerre bâ-irâde-i seniyye Der-saâdet ve Rumeli sevâhilinden Anadolının vilâyât-ı ma’lûmesine sevk olunacak muhâcirînin icrâ-yı iskânları emrinde vâli ve mutasarrıf ve iskân me’mûrları ve merkez-i vilâyât ve elviye merkezlerinin idâre komisyonları ve kazâ kaimmakamlarıyla mezkûr komisyonlar şu’belerinin sûret-i hareketlerini mübeyyen tahrîr olunan ta’lîmât-ı seniyyedir.” BOA. YA.RES.1.41.2.3.8 Haziran 1294 (20 June 1878).

6. “Otuz altıncı madde Muhâcirîn-i merkûmenin cümlesi ashâb-ı zirâatten olmayub içlerinde hâceler ve ehl-i sanâyi âdemler dahi bulundığından bu misillû hâcelerden ehliyyet ve istihkakı sâbit olanlarının imâmet ve cihât-ı sâire tevcîhiyle tatyîbleri ve icrâ-yı san’at itmek üzere şehrde ikametlerini ârzû iderek dükkân ve hâne istîcâr ve iştirâsına ve kalfa ve çıraklık ile ahâlî-i esnâfın yanına girmeğe tâlib olanlar ve ashâb-ı servetden olarak şehirlerde temekkün itmesini isteyenler olur ise haklarında cümle tarafından bezl-i himmet ve gayret ve teshîlât-ı lâzıme ve muâvenet-ı mukteziyye îfâ olunacaktır.” BOA. YA.RES.1.41.2.7.8 Haziran 1294 (20 June 1878).

they insisted on staying in the capital, they would have to leave the public buildings in which they had lived without charge (meccânen). Only the ones who accepted being sent to the rural areas would be given permission to stay until their time of evacuation.7 The others who chose to stay were evicted from the public buildings, and that process of eviction was almost completed by the end of the summer of 1883.8

The archival documents indicating the administration’s perception of the teneke evler − houses constructed out of old collected boards, gasoline tins, and other waste materials − are mostly dated to the period after 1883. This fact suggests that the eviction of the poorest immigrants created a huge demand for housing, as they had no chance to rent or buy any dwellings in formal ways as their means of subsistence hardly allowed them to earn their daily bread. The evicted immigrants, whose number was around a few thousand,9 found a creative solution for the housing problem by building their own houses near and on the almost completely ruined old city ramparts (Kadırga Limanı mahallesinde ve Kule-i Zemînde),10 by railways (Yedikule’den Kumkapı’ya kadar şimendifer hattı boyunda),11 and in the empty territories and farmlands in the suburbs of the city (Balmumcu Çiftliği arâzîsinde).12 They sometimes completely ignored the regulations of dwelling construction and built their houses leylen “at night,” and hafiyyen “secretly,”13 on public or private lands without getting any permission from the municipality or the other formal institutions. Sometimes they manipulated legal loopholes to take an opportunity for house ownership without paying much. They had neither enough time nor financial resources to consider architectural requirements for the constructions, as their priority was clearly housing itself, not its quality. These were probably not the earliest informal and irregular dwellings in the Ottoman cities, but they were obviously the most crowded ones and, therefore, the most visible.

Within ten years, a new term had been invented that referred to a neighbourhood that consisted of teneke evler “tin can houses”: teneke mahalle

7. “şâyed gitmeyanlar olur ise ta’limât-ı mezkûrada gösterildiği üzere muhâcirînin meccânen ikamet iyledikleri mahallerdeki muhâcirînden yalnız taşraya sevk olunacakların ibkasıyla Der-saâdette kalacakların külliyyen ihrâcı.” BOA. Y.PRK.KOM.4.20.1. 29 Temmuz 1299 (8 August 1893).

8. “muhâcirîn sâkin olan mahallerde gidecek olanlardan mâ-adâ muhâcir kalmamış hükmünde ve hele Beşiktaş’da kâin Akarât-ı Hümâyûnları derûnunda bulunan muhâcirînden ke-zâlik gidecek olanlardan başkası kâmilen çıkarılıp.” BOA.Y.PRK.KOM.4.20.5. 15 Şevvâl 1300 (19 August 1883).

9. BOA. Y.PRK.KOM.4.20.3. 1 Ağustos 1299 (13 August 1883). 10. BOA. DH.MKT.1667.10.1.1.3 Teşrîn-i Evvel 1305 (15 October 1889). 11. BOA. DH.MKT.5.43.5.2.9 Haziran 1309 (21 June 1893).

12. BOA. Y.PRK.M.3.38.1.3.

“tin can neighbourhood.”14 According to the record book, including the data on teneke ev dwellers, dated 1892, the earliest cluster of teneke evs denominated, as a “teneke mahalle” was in Coum-Capou (Kumkapı),15 Teneke Mahallesi, which was located between the railway and almost ruined rampart in Coum-Capou, one of the oldest neighbourhoods of historical Istanbul, comprising a relatively crowded Armenian population, and to a lesser amount, Greeks.16 Its counterpart, located in an almost empty part of Balmumcu farmland named Taşocağı,17 referring to the old quarries located there, was also known as Nishantashi Teneke Mahallesi, an expression that implied its spatial proximity to Nishantashi (Nişantaşı).18 Even though it was built at almost the same time as Coum-Capou Teneke Mahallesi, the first document in which this locality was defined as a teneke mahalle belongs to a relatively late time: 1899.19

This study, which focuses on the ethno-social origin of teneke mahalle founders, and the conditions of their co-inhabitation with the local poor, is based empirically on archival sources and, to a lesser degree, historical novels, travelogues, narratives, news, and interviews regarding the two oldest examples of the phenomenon, and its results cannot be generalized for all teneke mahalles; rather, it provides grounds for the further research.

Review of the archival sources

From the end of the 1880s, the Ottoman administration tried to register the residents of teneke mahalles, and prepared record books that provided significant data from which to review the socio-economic conditions of the teneke mahalles. The motivation for this attempt was that the Ottoman state

14. “Kumkapı taraflarında şimendifer hattı boyunda gaz tenekelerinden küçük küçük kulübeler inşâ idilerek tedrîcen bir mahalle husûle geldiği ve bu kulübelerin derûnunda iskân idenlerin muhâcirîn ve fukarâdan iduğu.” BOA. İ.HUS.10.12.1.1.10 Mart 1309 (22 March 1893). 15. The original Turkish spelling of the word is “Kumkapı.” The French and English authors of the nineteenth century generally rendered the word “Coum-Capou.”

16. “Kumkapıda, hisâr dibinde Teneke Mahallesi’nde barakada iskân idenler.” BOA. İ. ŞE.2.30.1.1.

17. “Avusturya devleti tebaasından Marko Boçin nâm kimsenin Emlâk-ı Şâhâne’den Şişli Ihlamurdere ve Molla Ayazma nâm mevki’lerde istîcâr iylediği Frenk taşı ocağının bendlerden taksim çeşmesine gelan su yollarına mazarratı oldığı beyânıyla ta’tîl idildiğinden.” BOA. HR. TH.99.79.1.1.29 Mayıs 1306 (10 June 1890).

18. The original Turkish spelling of the word is “Nişantaşı.” Nineteenth-century English authors rendered the word “Nishantash,” and French, “Nichantach.” Nishantashi was established with a special order of Abdulmejid I as an elite settlement separating its territory from Balmumcu farmland in the second half of the nineteenth century (Esatlı 2010: 69). 19. “Nişantaşı’nda vâki’ taş ocağında geçenlerde muhterik olan Teneke Mahallesi’ndeki külbelerin yeniden yapılmasına müsâade olunmadığı gibi yanmamış olanların dahi hedmi cihetine gidilmekde bulundığı.” BOA. Y.MTV.185.98.26 Kânûn-ı Evvel 1314 (7 January 1899).

officials were worried about the rapid development of teneke mahalles, and needed to recognize the dynamics of this situation. Whenever they intended to make a policy change on the issue, they initially launched a new survey concerning the demographic, sociological, and economic features of teneke ev dwellers. There are two record books in the Ottoman archives concerning Coum-Capou Teneke Mahallesi, respectively dated 1892,20 and 1893,21 and four on Nishantashi Teneke Mahallesi, dated 1888,22 1892,23 1901,24 and 1904.25 The data presented in this study is largely collected from them.

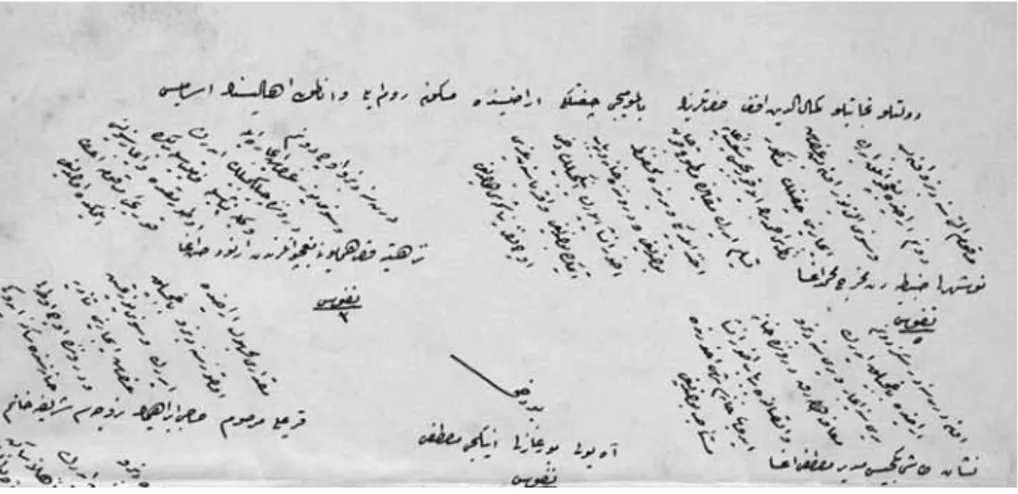

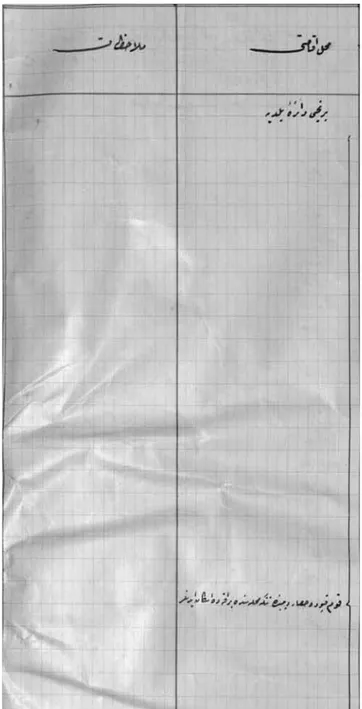

The record book (Figure 1) dated 1888 was prepared in research conducted by the Beyoğlu Mutasarrıflığı,26 and the directorship of police at Beşiktaş (Beşiktaş Polis Me’mûriyyeti).27 A “Der-saâdet ve Rumeli Vilâyâtı İskân-ı Muhâcirîn Me’mûru”28 was probably a part of the team.29 There are 121 households from all around Balmumcu farmland registered in the record book. Nishantashi-Taşocağı was located on the south-eastern side of the farmland, which is on the borderline of the Chichli (Şişli) and Beşiktaş districts today.30 From the record book, it is possible to learn the name, origin, and, occupation of household head; his/her date of arrival to the area, the way he/she gained the land and built his/her dwelling, the size, the former owner of land or dwelling, and the kind of the construction, i.e. house (hane), hovel (kulübe), barn, smithery, etc. (Figure 2). During this era, just 24 of 121 households were located in the Taşocağı Teneke Mahallesi.

20. For the whole text of the record book, see BOA. İ.ŞE.2.30.1.1-17. 21. For the whole text of record book, see BOA. İ.ŞE.2.30.2.1-2. 22. For the whole text of the record book, see BOA. Y.PRK.M.3.38.2-4. 23. For the whole text of the record book, see BOA. Y.MTV.73.43.7.1-9. 24. For the whole text of the record book, see BOA. Y.MTV.217.17.2.2-15. 25. For the whole text of the record book, see BOA. Y.MTV.265.37.2.3-19.

26. The highest formal authority of sancaks, which was an administrative unit between kaza and vilayet, were called mutasarrıf in the late Ottoman context (Pakalın 1971: 586). Between 1874−1926, Beyoğlu, or Pera, was a sancak (Sezen 2006: 80).

27. “ber-mantûk fermân-ı hümâyûn muhâcirîn-i merkumenin oralardan kaldırılması tabîî bulunmuş ise de bunların ne vakt ve kimler ma’rifetiyle iskân olunmuşlardır ve mutasarrıf veya müste’cir midirler bilinmek ve ona göre hükm-i irâde ve fermân-ı hazret-i pâd-şâhî yerine getürilmek üzere tahkikat icrâsı Beyoğlu mutasarrıflığına iş’âr olunmışdı. Mutasarrıfiyyet-i müşârün-ileyhâ ile Beşiktaş polis me’mûriyyeti beyninde bi’l-muhâbere tahrîr ve irsâl olunan ve manzûr-ı devletleri buyurulmak üzere leffen takdîm kılınan defter hulâsası mütâlaasında.” BOA.Y.MTV.35.70.1.1.26 Eylül 1304 (8 October 1888).

28. “Der-saâdet ve Rumeli Vilâyâtı İskân-ı Muhâcirîn Me’mûrı” refers to an official who specialized in the settlement procedure of immigrants in the capital and in Rumelia provinces. These officials were experienced on the issue, and were assigned by the central administration (İpek 1999: 168−9).

29. BOA. Y.PRK.KOM.7.7.3.1.21 Eylül 1304 (2 October 1888).

30. The original Turkish spelling of the word is “Şişli.” French and English authors of the nineteenth century generally recorded it as “Chichli.”

The names of Rumelians and Anadolians settled on Balmumcu farmland that belongs to Prince Kemaladdin Efendi

1 The mentioned one gardens for six years on five-decare land and pays 615 kurus rent annually to director of mentioned farmland, Ahmed

Bey and its keeper Şuayb Ağa and received printed receipt for this payment and he keeps it and on the land, he built a house and a one-roomed barn and he is also dairying and besides his relatives,

there are three hirelings. Nevşehirian Mehmet Ağa

dismissed from the Zaptiah Household population 5 Figure 2. The translation of the first item, 1888

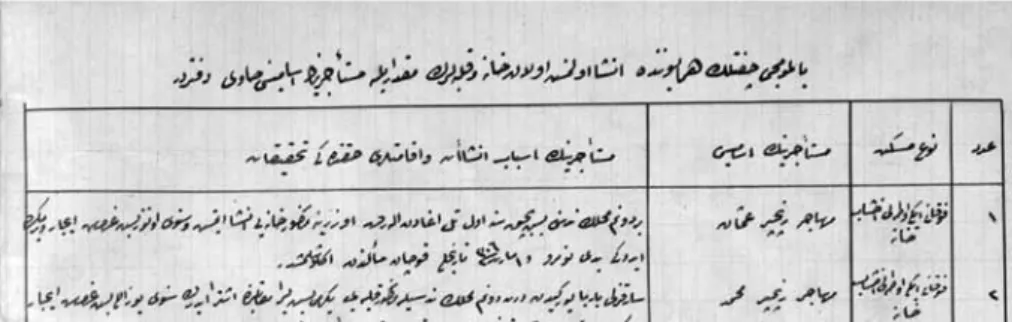

The research process to prepare the record book dated 1892 was conducted by the Hazine-i Hassa, the private treasury of the Ottoman sultan, which was the actual legal owner of Balmumcu farmland.31 In the record book (Figure 3), there are 268 entries, reflecting the 322 constructions, some of which belonged to 231 families, while the others were public buildings such as mosques. As indicated in the translation of the entry (Figure 4), as well as the architectural features of each building, the arrival date of the household owner, the size, the cost of possessory right transfer, the former tenant of

31. “Mantûk-ı celîline tevfîkan icrâ olunan tahkikat üzerine tanzîm idilan harita ile tafsilâtı lâzımeyi hâvî defterlerin leffen (ilişikte) arz ve takdîmine ibtidâr kılındı … Nâzır-ı Hazîne-i Hâssa Mîkâîl” (25 December 1892). For Mîkâîl Portakalyan Efendi see Kuneralp (1999: 6).

the land, the amount of annual rent paid to the farmland administration, and his/her origin and occupation were also explained in the record book. Furthermore, the ways by which the officials who prepared the record book accessed information, whether they depended on the interpretation of deeds or just on interviews, were also declared. It is understood from the record book that the number of households living in the Taşocağı Teneke Mahallesi, section of Balmumcu farmland increased to 71 between 1888 and 1892.

The record book dated 1901 was prepared by the special officials of Hazine-i Hassa by making observations in the locality to determine the estimated value of each construction.32 There are 731 items that define the

32. “ber-mantûk emr- ü fermân-ı hümâyûn hazînece ta’yîn kılınan me’mûrîn-i mahsûsa ma’rifetiyle mahallinde tahkikat-ı lâzıme bi’l-icrâ ol bâbda tahrîr ve leffen arz ve takdîm kılınan defter mündericâtından keyfiyyet muhât-ı ilm-i âli buyurulacağı üzere Balmumcu

Figure 3. The first page of the record book dated 1892

The record book including the number of “houses” (hane) and “hovels” (kulübe) built on Balmumcu Imperial Farmland and the names of tenants

Number Kind of

housing Name of tenant building and settling on the landInquiry results – reasons for 1 “Fevkani” (two-storey) two-roomed wooden “hane” (house) Mohadjir agricultural labourer Osman

It is understood from the interpre-tation of the deed number 7 and dated 306, March 1 that he bought

one decare fallow land from Tali Ağa 5 and half years ago and built

the mentioned “house” on it and pays 35 kurus for each year Figure 4. The translation of the first item, 1892

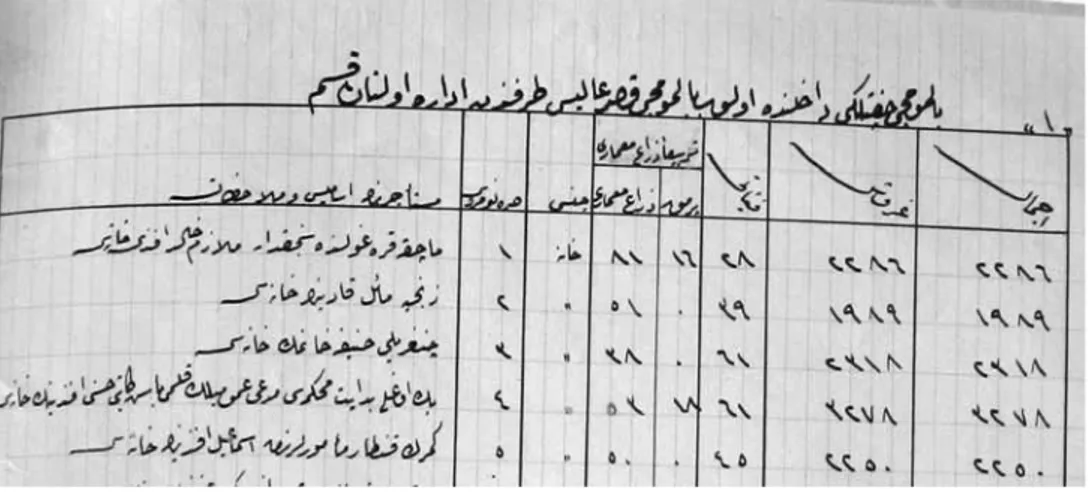

general socio-economic and demographic data, the architectural features, and the estimated value of each construction belonging to the 438 families in the record book. A small section of the first page of the record book may be seen in Figure 5. As the translation (Figure 6) indicates, the number, type, square measure by zira-ı mi’mârî and parmak (the unit prices used in calculation of the estimated price of each building), the price of the building by kurus (a local currency), and the total price of all buildings

Çiftliği dahilinde inşâ edilmiş olan hane ve barakalardan … Nâzır-ı Hazîne-i Hâssa Ohanes. Ohanes Sakız Efendi” (19 June 1901). For Ohanes Sakız Efendi see Kuneralp (1999: 6).

Figure 5. The first page of the record book dated 1901

The section within the boundaries of Balmamcu farmland and managed by Balmamcu Manor House

Names of tenants and explanation

Number Kind Square measurement Unit

price Kurus Total Zira-I Mi’mâri Parmak The household of Halid Efendi who is lieutenant flagbearer in Maçka police station 1 House 81 16 28 2,286 2,286

owned by each household head were the standard details for each building shared in the record book. The name, origin, and occupation of the household head were written as much as possible but, for some buildings, these details were absent. Household heads were registered as tenants in the record book considering the fact that, regardless of their building ownership, they were classified as tenants by the farmland administration, reflecting the judicial assumption that the terrain was imperial property. During the era, 168 of 438 households were living in Nishantashi Teneke Mahallesi.

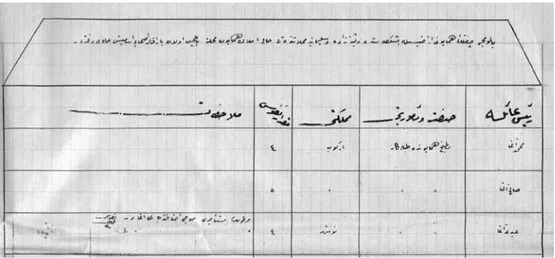

The record book dated 1904 was the work of the officials of the fourth municipal area (dördüncü dâire-i belediye).33 There are 592 households registered, 486 of which were building owners and 106 were tenants. Furthermore, the details of occupation, origin, and household population for each household head can be learned from aforementioned record (Figure 7). There were 186 households in Taşocağı sections during the era.

33. “mârü’l-arz barakaların hedmi muâmelâtı hakkında îfâsı muktezî muamele ve hareketin işbu defterin leffiyle emânet-i müşârün-ileyhâdan arz ve istîzânına müsâraat buyurulmak babında emr ü fermân hazret-i men lehü’l-emrindir … Müfettiş Vekîli (mühür) Mühendis-i Evvel Vekîli (mühür) Tahrîrât Kâtibi (mühür) Dördüncü Dâire-i Belediye Mal Me’mûrı.” BOA. Y.MYV. 265.37.2.15.31 Ağustos 1320 (13 September 1904).

The record book ıncluding the names of the owners of hovels contructed on the terrain of the Balmamcu ımperial farmland and the empty ımperial terrain in

Vişnezade and Süleymaniye neighbourhoods in Beşiktaş

Household

head Art or official duty Origin Household population explanationsAdditional Mehmed

Ağa imperial kitchenTablakar in the Ürgüp 4 Salih Ağa Tablakar in the

imperial kitchen Ürgüp 5 Abdi Ağa Tablakar in the

imperial kitchen Nevşehir 4 the mentioned The tenant of Ali Ağa, the water seller, Household population: 2 Figure 8. The translation of the first item, 1904

The first record book (Figure 9) including data on Coum-Capou Teneke Mahallesi was prepared in 1892 by the local municipalities (devâir-i belediye), to reveal the socio-economic and demographic features of the residents of the hovels constructed of waste materials like old boards and gasoline tins all around the city.34 They aimed to differentiate between the absolute poor, such as widows or the elderly, and the ones who had an occupation and, therefore, would probably have been able to rent or buy a home with their own resources. The 4,868 residents living in 979 hovels and similar kinds of dwellings in ten municipal areas of Istanbul were registered in the record book (işbu barakaların adedi dokuz yüz yetmiş dokuza ve muhâcir olarak mikdâr-ı sükkânı dahi dört bin sekiz yüz altmış sekize bâliğ olup).35 The exact location of each dwelling, the origin and occupation of household head, and the population of each household was recorded in the record book (Figure 10). Fifty-two of 979 households were living in Coum-Capou Teneke Mahallesi.

34. “evvel-emirde bu misillû âcizenin ne mikdâr nüfûsdan ibâret olub nerede ve kaç külbede sâkin olduklarının ve bunların içinde taşraya iğrâm olunmak üzere zirâatle iştigal idecek kaç âile bulundığının ve zirâat ve hirâset idecek kimsesi bulunmaması hasebiyle burada iskân ve iâşesi zarûrî olan dul kadınlarla eytâm mikdârının devâir-i belediyece serîan tahkik ve bir kıt’a defter tahrîr idilerek birkaç gün zarfında irsâl.” BOA.BEO.52.3875.2.1. 24 Muharrem 1310 (17 August 1892).

M ig ra nt s an d o th er s w ho a re ab le t o b uy or r en t dw el lings as t he y a re ar tis an s or t ra der s an d w ill b e ev ac ua te d by p ol ic e M ig ra nt s an d o th er s w ho w ill b e sen t t o t he pr ov in ce s an d w ho ar e a bl e t o eng ag e i n ag ric ul tu re M ig ra nt s an d o th er s w ho a re in n ee d o f ca re a nd se ttl em en t as t he y h av e no bo dy a ble to eng ag e i n ag ric ul tu re Th e na m e o f ho us eho ld he ad H om et ow n O cc up at io n Pl ac e o f r es id en t Ex pl an at io n Fi rs t M un ic ip al A re a 10 A sa du r H ar pu t A gri cu ltu ra l w or ke r Th e o ne s w ho liv e i n t he te ne ke mah all e ne ar th e r am pa rt i n Ku m ka pı Fig ur e 10 . Th e t ra ns la tio n o f t he fi rs t i tem , 1 89 2

Fig ur e 11 . Th e fi rs t p ag e o f t he r ec or d b oo k d at ed 1 89 3 N ei gh bo ur-ho od H om et ow n Pop ul at io n Th e na m e o f ho us eho ld Re lig ion O cc up at io n A ble D isa ble d A ble to w or k Un ab le to work Ex pl an a-tion Şe hsu va r Ed ir ne 1 A li b in Me hm et Is la m Pa çav ra ci A ble A ble Şe hsu va r Ple vne 4 Me hm et Is la m Kü fe ci A ble A ble Fig ur e 12 . Th e t ra ns la tio n o f t he fi rs t i tem , 1 89 3

In 1893, the Istanbul Municipality (Şehremâneti) and the administration of “birinci belediyye dâiresi”, one of the enumerated municipal domains of the city, prepared a new record book containing only the registrations of 128 households that were located in quarters around the railway such as Coum-Capou Teneke Mahallesi.36 They intention was the same, i.e. to see who would be able to settle through their own resources and who would need the assistance of the state. The name of household heads and, in many cases, their fathers’ names, their occupations, home towns, and religion are registered in the record book (Figure 12). However, when the administration evaluated the data in the record book, they realized that those who were working in menial jobs such as carriage drivers (arabacı) were extremely poor (erbâb-ı fakr u zarûret), and civil servants with low income such as cleaning services (tanzîfât amelesi), were barely able to earn their daily bread (akvât-ı yevmiyye).37

The data gleaned from the record books is critical proof of the actual presence of teneke mahalles as a socio-spatial phenomenon, which had been poorly documented until now. Nevertheless, some additional sources like oral interviews – some previously published, and others published for first time in this article – and literary sources like narratives, memoirs, and even fiction, allow us to follow the public discourses regarding this phenomenon.

The change of Ottoman Roma policy before the 1893 war

The founders of the earliest teneke mahalles were Mohadjirs according to the record books. This term was popular during the era, to the extent that even some Levantine and western Traveller authors used it in their narratives, indicating the great influence of the war on population movements.38 However, this term needs clarification in that, as indicated earlier in this study, the Muslim immigrants were not a homogeneous community, but a huge population of immigrants of various classes and ethnicities. Unfortu-nately, it is never easy to detect ethnic origin just drawing on the archive

36. “güzergâh-ı mezkûrede mütemekkin olanlar yeniden bi’t-tahrîr tahrîr itdirilan defteri meclis-i emânet ifâdesiyle leffen ve evvelki defter maan arz ve takdîm kılınmış … birinci dâire müfettişliğinden virilan rapor meâlinden müstefâd olmuş olmağın ol bâbda emr ü fermân hazret-i veliyyü’l-emrindir … Şehremîni Rıdvân. Rıdvân Paşa-1890/1906-:” (11 July 1893). For Rıdvân Paşa see Kuneralp (1999: 34).

37. “nüfûs-ı merkumeden yirmi altı hâne halkı seele ve dul ve bî-kudret ve küsûride tanzîfât amelesi ve küfeci ve arabacı gibi akvât-ı yevmiyyesini ancak tedârik idebilür erbâb-ı fakr u zarûretten bulundığına mebnî.” BOA. İ.ŞE.2.30.4.1.4 Ağustos 1309 (16 August 1893).

38. “The twins, on their return from one of their expeditions, described how they had seen some half-dozen of the Mohadjirs, as they were called, from a vantage ground on the top of a hill” (Bilir 1895: 3).

records. There are very few documents in the Ottoman archives referring to the ethnic origin of the Mohadjirs, but in many others, they were considered as an entire community of Muslims who experienced the pain of the war and deserved special attention as a compensation for this tragedy. This was also true for the Roma Mohadjirs to a considerable degree, at least initially.

Roma were institutionally classified as “Çingene” or “Kıbtî,” the etymolog-ically and semantetymolog-ically Ottoman equivalent of the word “Gypsy,” a term probably borrowed from the Byzantine Empire according to the convincing arguments and the findings of Soulis (1961: 148) and Ginio (2004: 131). This designation was also a head tax category: “Kıbtî Cizyesi” (Ginio, 2004, s. 117), in the Ottoman case. Eighteenth-century sources reflect the Ottoman administration’s perception of the Kıbtî population as a distinct category of cizye taxpayers, a tax justified by the fundamental principles of Islamic texts and canonically paid by non-Muslims. However, when it comes to the case of the Kıbtî, it becomes more obvious that the basis for the designation of “cizye” was something more than religious stratification, since even the Muslim Kıbtî were obliged to pay it (Ginio 2004: 118).39 “Cizye” was a concrete indicator of non-Muslims’ subjection to the Muslim conquerors. It was also a compensation that allowed non-Muslims to live in peace without conversion under the rule of the Muslim state (Cahen 1991: 559). However, non-Muslims living in frontier districts who could participate in the army units for a certain period had limited exemption from the “cizye” (Cahen 1991: 561). Similarly, the Muslim Kıbtî serving in the army, but just in the service areas (Çelik 2004: 67),40 had immunity from cizye taxation (Dingeç 2009: 44).

During the nineteenth century, the Ottoman army was also influenced by strong pressure from the universal waves of modernization. The new army regulations developed a system of conscription that required five

39. According to Ginio, collection of cizye from Muslim Roma might have been a practice that originally belonged to the Byzantine Empire as a specific poll tax for Gypsies, and adopted by Ottomans with a name change and religious re-formulation (Ginio 2004: 130−1). He also refers to the lack of any proof for the collection of cizye from Muslim Gypsies in Arab provinces (Ginio 2004: 131). Further research has to be done before crediting or discrediting this argument. However, there are many documents in the archives that indicate collection of a specific poll tax from Muslim Kıbtîs outside the Balkans. Here is an example of this practice: “The specific tax (kesim) which used to be collected from Muslim cingânes in Anatolia and other places” (Anadolu ve sâir müslüman cingânelerden alınu-gelen kesimi) (Akgündüz 1990: 46–8). There is also a cizye record dated 1843 indicating that Muslim Kıbtîs in Antalya, a region in the southern Anatolia, were liable to poll tax, namely cizye (Dinç 2017: 163).

40. They were accepted for the auxiliary services in the army and were generally not a part of the warrior units (Dingeç 2009: 38). There are some references in various historical sources pointing to their participation in warrior units, but these samples need confirmation in a more convincing manner (Marushiakova and Popov 2006: 41).

years military service and the recruitment of 30,000 men a year; and among those eligible for service, the drawing of lots (kura) determined the recruits’ positions in the army units (Zürcher 1998: 440). Only the Muslims were liable for compulsory military service (Zürcher 1998: 445) and, thus, their liability corresponded to non-Muslims’ obligation to pay “cizye,” which became a kind of compensation for the exemption from the military in the contemporary manner.

The Royal Edict of Reform (Islâhât Fermânı), which put special emphasis on equal rights and responsibilities for Muslims and non-Muslims in the empire, made non-Muslims liable for military service. However, neither group was enthusiastic about the participation of non-Muslims in the Ottoman army; in time, this new policy of payment of an exemption tax (bedel-i askerî) instead of conscription lasted until 1909 (Zürcher 1998: 445−6). According to the nineteenth century Ottoman historiographer Mustafa Nuri Paşa (1987: 292), in the Royal Edict of Reform (Islâhât Fermânı) in 1856, a new tax category, the “bedel-i askerî,” was imposed, which replaced the cizye. Actually, this was just a name change in that the function of the bedel-i askerî was never different from cizye; it was simply compensation for the forced or voluntary exclusion of non-Muslims and Kıbtîs from military service. Similar to the cizye practice, the bedel-i askerî were also collected from Kıbtîs, and this means, in practice, the continuation of inferior distinct statute of Kıbtîs in the Ottoman administrative structure and, to a degree, social stratification (Ulusoy 2011: 132).

The modernization of the army and financial requirements increased the importance of information on the qualitative and quantitative features of the Ottoman male population. This need was among the primary sources of motivation to develop a new statistical tradition in the late Ottoman Empire (Karpat 1985: 6–7). Therefore, in 1831, in the earliest census of the century, only males were counted in accordance with the traditional registration methods of the empire: that is, the government aimed to solve problems raised from unfair or inadequate taxation, and to determine the correct number of Muslim males who would serve in the army and non-Muslim males who would pay the cizye (Karpat 1985: 20). In the census, the Ottoman population was classified following the traditional procedure of Ottoman registration, by which religion was the basic classificatory criteria. This logic was consistent for the sub-population groups of the Ottoman state, that is, Muslims, Christians, Armenians, and Jews. However, the classification of Kıbtîs separately, regardless of their religion, Muslim or non-Muslim, was a complicated phenomenon (Karpat 1985: 20). According to the results of the census, there were 2,501,425 Muslims, 1,178,171 Reaya (a generic category for non-Muslims, particularly Orthodox Christians), 17,012 Jews, 20,309

Armenians, and 36,675 Kıbtîs (Karal 1997: 215). Shaw considers these results to be questionable, and should be regarded as “not more than estimates,” and therefore, the results of this census are much lower than the subsequent ones (Shaw 1978: 326). A new and more comprehensive census was initiated in 1844, and completion of the count took more than ten years. Even then, the complete results were not published by the state; rather, European writers published the data (Karpat 1985: 23). One of them was Ubicini (Karpat 1985: 23) and, according to him, the number of Kıbtîs just in the European Ottoman territories was 214, 000 during that era (Karpat 1985: 116).

The ancient classification policy of Ottomans to denominate Roma and, in many cases, other peripatetics,41 as Kıbtî (which substantially means that even the Muslim Roma were recognized by the state as a separate ethno-social unity from the non-Roma Muslims), changed in a few steps, a very short time before the Russo-Turkish War of 1877–1878. As a start, in the last quarter of the nineteenth century, the exemption of Muslim Kıbtîs from military service was abolished, and the collection of the “bedel-i askerî” from them ended (Ulusoy 2011: 131). According to Hacı Ahmed İzzet Pasha, the Edirne governor (Kuneralp 1999: 30), recruitment among Muslim Kıbtîs provided many benefits to the state (merkumlardan asker alınması devletçe fevâid-i adîdeyi … müstevcib olacağı gibi), and more importantly, the size of the population and the number of households of Kıbtîs in Rumelia was too large to allow their alienation from local Islamic society, and in such a sensitive land, it would not be acceptable (Rûmeli kıt’asında bunların çok hâne ve nüfûs olmağla böyle bir kıt’a-i nâzikede öyle binlerce nüfûs-ı Müslimeye İslam nazarıyla bakılmayub dâire-i cem’iyyet-i İslamiyeden eb’âd olınmaları tecvîz buyurulmayacağına binâen).42 The claim of the Pasha about the sensitivity of the land, Rumelia, can easily be understood, considering the fact that the great war, the Russo-Turkish War of 1877–1878, was so close, and the tension between Muslims and non-Muslims was rising in the

41. I prefer to use the term “peripatetic” as a social category, in which Roma and others can be classified, and largely draw on the definition established by Rao. According to the author, the survival and adaptation strategy of peripatetics was a combination of “spatial mobility,” “non-subsistent commercialism,” and endogamy (Rao 1987: 3). However, when it comes to the contemporary descendants of former peripatetics who are less mobile and who adopted new subsistence strategies in accordance with the requirements of largely urban environment, I prefer to use a new and more elastic concept, late-peripatetics (Yılgür 2016). There are many archival documents indicating the Ottoman use of the term Kıptî for non-Roma peripatetics. Tahtacis and Abdals, two typical cases of non-Roma peripatetics, were classified as Kıbtî in the 1831 census, at least partly. Here is just one example of the record of Abdals and Tahtacis registered in Antalya: “kıbtis called as tahtacı and aptals” (tahtacı ve aptallar tabir eyledikleri kıptiler) (Karal 1997: 122). See Roux (1987) for a detailed account of Tahtacis; Yıldırım (2011) for the Abdals; and Yılgür (2017b) for an overall evaluation of peripatetics in Turkey.

territory.43 Likewise, the seraskier of the era,44 Hüseyin Avni Paşa (Kuneralp 1999: 9) argued that the exception of Muslim Kıbtîs from conscription would motivate the non-Kıbtîs to adopt this identity in order not to join the ranks of the Ottoman army, and this would cause a critical difficulty for the army in finding new eligible men to add to the drawing of lots for conscription.45 This possibility had never come to the agenda of the Ottoman state in hundreds of years. However, the context and the conditions had changed, and the ancient rules had to be adapted to them. The arguments of the seraskier and Edirne governor, referring to the local sensibilities, convinced their superiors, and finally a royal decree (irâde-i seniyye) was issued to repeal the ancient exception of Muslim Kıbtîs from the military service, and to make them liable for conscription by the end of 1873.46

The policy change caused the substantial basis for the segregation of Muslim Kıbtîs from other Muslims to become vague. Also, the Russo-Turkish War of 1877–1878 followed the policy change, and the conditions of war and defeat weakened the socio-cultural borders among the Muslim population. The Mohadjir, the Muslim immigrants leaving the Ottoman territory in contemporary Bulgaria and Rumania, were the concrete evidence of this process, in that they shared almost similar terrifying conditions during their journey to the Ottoman capital regardless of their socio-economic background or ethnic origin. The former mufti of Stara Zagora (Zağra-i Atîk), Hüseyin Râci, a middle-class Mohadjir who shared his memories in his poetical work, first published in 1910, refers to this fact: “Türk, Pomak, miserable kıbtî were heaped up in the ship mercilessly” (Hüseyin Râci Efendi 1975: 267).47

43. One of the basic issues addressed by Mithat Pasha, one of leading pro-reform statesmen of the nineteenth-century Ottoman Empire, was to weaken the Bulgarian separatist movement, also supported by the Pan-Slav policy of Russia, while he was the governor of Tuna province (1864–1867) (Davison 1986: 162).

44. Ottoman defence secretary (Pakalın 1971: 176).

45. “tâife-i merkumenin ol sûretle askerden istisnâları hizmet-i askerîyeden kurtulmak zu’m-i fâsidesiyle Kıbtî olmayan ve öteden berü İslamiyetle müştehir olan bir takım hamiyyetsiz kesânın tahvîl-i lisân ile bu da’vâ-yı nâ-be-câya sâlik olmalarıyla sâire dahi sirâyet iylemesini ve bi’t-tab’ anâsır-ı İslamiye dokunup elde bulunan nüfûs-ı İslamiyenin tednîsiyle kur’a çekilerek efrâd bulunamamasını müstelzim olarak.” BOA.ŞD.609.40.3.1.28 Şubat 1288 (12 March 1873).

46. “Ma’rûz-ı çâker-i kemîneleridir ki Hâme-pirâ-yı ta’zîm olan işbu tezkire-i sâmiye-i âsaf-âneleriyle evrâk-ı ma’rûza manzûr-ı me’âli-mevfûr-ı cenâb-ı Şehin-şâhî buyurulmuş ve tezekkür ve istîzân olundığı vechile ba’d-ez-în Kıbtîlerden de asker alınmasının usûl ittihâzı müteallik ve şeref-sünûh buyurılan emr ü fermân-ı hümâyûn şevket-makrûn-ı Hazret-i Zıllullâhî mantûk-ı münîfinden olarak evrâk-ı mebhûsa yine savb-ı sâmi-i vekâlet-penâhîlerine iâde kılınmış olmağla ol bâbda emr ü fermân hazret-i veliyyü’l-emrindir. 29 Şevvâl 290 (20 December 1873).” BOA. İ.MMS.47.2025.13.1.

The categories of the next census were defined taking these developments into account. The second clause of the population registry regulation (Sicill-i Nüfûs Nizâm-nâmesi), dated 1881, underlined that the records would be kept separately for Muslims and the other religious communities (işbu siciller ahâlî-i Müslime ve cemâat-i sâire içün başka başka tanzîm olunacakdır).48 The fourth clause of the instruction for the execution of census (Tahrîr-i Nüfûsun Sûret-i İcrâsına Mahsûs Ta’limât) orders the registration of Muslims as a whole entity, and all the non-Muslim communities as separate communal units in their own records.49 In the third clause of the special instruction for the census in Istanbul (Der-saâdet ve Bilâd-ı Selâsede mütemekkin bi’l-cümle nüfûsun bâ-irâde-i seniyye icrâ olunacak tahrîrine dâir ta’limât), the binary categories of the census for population classification are defined as Muslim or non-Muslim and married or single; and this actually means that there would be separate records for Muslim and non-Muslims.50 When it comes to the registration of the Mohadjir, the thirteenth clause of the same regulation orders the Mohadjirs to be registered in quarters’ lists if they are married and otherwise, with other singles. But the officials of the census have to put a sign in the records near the name of each individual referring them to be Mohadjir.51

This way of registration largely explains the formal disappearance of Muslim Kıbtî immigrants: they were absorbed into the huge crowd of Muslim Mohadjirs. However, the issue was further complicated, in that in response to the demand of census officials for clarification of the method of registration of the local Muslim Kıbtîs in Istanbul,52 one of the highest institutions of the

48. BOA. A_) DVN.MKL.20.35.2.1.24 Eylül 1297 (8 October 1881).

49. “Sicill müsveddeleri ahâlî-i Müslime içün başka tutılacağı gibi ahâlî-i gayr-i Müslime için dahi başka başka tutılarak ve her cemâatin nüfûsı o cemâate mahsûs olarak ayruca müsveddeye kayd ve tahrîr olunarak sicill-i esâsîye dahi bu tertîb ile nakl ve terkim idilecek ve ahâlî-i gayr-i Müslimenin ahvâl-i askerîye hâneleri açık bırağılacaktır.” BOA. Y.A.RES.11.59.1.1.

50. “Madde 3 Nüfûs-ı Müslim ve gayr-i Müslim ayru ayru ve ahvâl-i kadimesi vechile evli ile bi-kâr başka başka olarak tahrîr idilecek ve medâris ve tekâyâ ve hanlardan başka emâkin ve meskenlerde bulunan nüfûs mahalle üzerine kayd olunacakdır.” BOA.ŞD.695.29.8.2.3 Şubat 1297 (15 February 1882).

51. “Madde 13 Mahallât arasında hânelerde sâkin olan muhâcirîn müteehhil defterine kayd olunması tabîî ise de esâmîleri hâmişine muhâcir oldukları şerh virilecekdir. Mesâcid ve maâbid gibi umûma mahsûs olan mahallerde sâkin olanlar içün başkaca defter tutılacak yani bir mahallenin müteehhil ve bî-kârı başka başka defterlere kayd olundukları misillü o makule muhâcîr içün dahi başka defter tutılacakdır.” BOA.ŞD.695.29.8.3.3 Şubat 1297 (15 February 1882). There are similar orders in the enactment of the census in Istanbul: “Der-saâdete Mahsûs Tahrîr-i Nüfûs Karâr-nâmesi/Onbirinci Madde: Nüfûs-ı Müslim ve gayr-i Müslim ve ale’l-umûm evli ile bî-kârlar başka başka tahrîr idilecek ve muhâcirînden olub da müteehhil bulunanların esâmîsi kenârına muhâcir oldukları işâret kılınacaktır.” BOA.Y.A.RES.10.45.3.2.9 Şubat 1296 (21 February 1881).

52. “Der-saâdet sekenesinden olan Müslim Kıbtîler gerek sicillât ve gerek tezâkir-i Osmani-yedeki mezheb hanesine Kıbtî ibâresinin yazılmasına muvâfakat itmediklerinden ve nüfûs

modernizing Ottoman state, the Şurâ-yı Devlet Tanzîmât Dâiresi, ordered the acceptance and registration of Muslim Kıbtîs as Muslims and non-Muslim Kıbtîs with the religious community to which they actually belonged.53 Then, just like the Mohadjir Muslims, at least the majority of local Kıbtîs were added to the rank of Muslims and, to a lesser degree, to the non-Muslim communities of the empire in the formal census statistics. Therefore, while at least 36,675 Kıbtî males were registered in the 1831 census, there were no Muslim Kıbtîs, and just 3,153 (male and female) non-Muslim Kıbtîs, who probably did not belong to the enlisted non-Muslim communities,54 unlike the other non-Muslim Kıbtîs who were unified with the non-Muslim communities in accordance with the order of the Tanzîmât Dâiresi, in the census of 1881/1882–1893 (Karpat 1985: 149). After all this, local and immigrant Muslim Kıbtîs were no longer part of the formal segregation of the Ottoman population, and they were added to Muslim masses at least on paper.

Informally Kıbtî and formally Mohadjir

Even though the Kıbtî Mohadjirs became invisible in the formal population statistics, this did not mean that ordinary citizens completely abandoned their perception categories, which had been the daily basis of the segregation of Roma and other peripatetics from the majority. Romani immigrants were aware of the benefits of the abolishment of the formal policy for them, and adopted their new denomination, “Mohadjir,” with a great enthusiasm. However, for the non-Roma immigrants, being under the same category as the Roma was not perceived as a privilege, but rather a misfortune. Moreover, sympathy for the Mohadjirs in the local community weakened in time as a result of daily conflicts.

The majority of the Mohadjirs were initially welcomed in public buildings (İpek 1999: 58), but also in private buildings such as mansions, without needing permission from their owners (İpek 1999: 65). Unlike the first wave,

nizâm-nâmesinde ise bu bâbda bir gûna sarâhat olmadığından bunlar hakkında ne yolda muâmele olunmak lazım geleceğinin li-ecli’t-tezekkür iş bu müzekkirenin Şûrâ-yı Devlete havâle buyurulması bâbında emr ü fermân hazret-i veliyyü’l-emrindir.” BOA.ŞD.2501.19.2.1.26 Kânûn-ı Evvel 1301 (7 January 1886).

53. “Kıbtîlerin İslam olanlarının cemâat-i Müslime ve Hristiyan bulunanlarının mensûb oldukları cemâat-i gayr-i Müslime efrâdından add idilerek sicillât ve tezâkirde ona göre icrâ-yı muâmelat olunması evvelce vâki olan istîzân üzerine Şurâ-yı Devlet Tanzîmât dâiresinden kaleme alınan 16 Kânûn-ı sânî 301 (28 January 1886) tarihlü mazbatada gösterilmiş oldığından Müslim Kıbtîlerin tezâkir-i Osmaniyelerinin mezheb hânelerine Müslim yazılması ve gayr-i Müslim olanlar hakkında da ona göre muâmele îfâsı lüzûmi.” BOA.DH.MKT.632.19.1.2. 30 Kanunievvel 318 (12 January 1903).

54. Greeks, Armenians, Bulgarians, Catholics, Protestants, Latins, Monophysites, Jews (Karpat 1985: 122−3).

there would be many other waves of immigrants soon, of agriculturalist or middle-class Mohadjirs who left the temporary settlements after a short time, and settled in the villages, renting or buying or building their own houses, the Roma Mohadjirs, for whom agriculture was largely an exceptional case, and a majority of whom were suffering from poverty even before the war, stayed for longer in public buildings, mansions, etc. They were trying to survive against hunger and weather conditions, and for these purposes, they rebuilt or adjusted the temporary settlements, making them more suitable for their basic needs, without considering aesthetic or architectural priorities. The famous early republican novelist Memduh Şevket Esendal mentions one of the examples of this situation in his novel, Miras, which was first published serially in the Meslek newspaper in 1924:

They were dying from starvation, misery or cold. They untied and burned the doors of the mansion, cut its trees, broke its boards. The huge mansion became wholly terrible. And one day, even the mohadjirs went away. (Esendal 2015: 19)55

The reaction against this kind of daily conflict was a direct result of the forced encounters of various groups whose spatial strategies, perception of material objects, and primary needs were obviously different, and to a degree, conflictive. This conflict forced the non-Roma, middle-class Mohadjirs, to emphasize their distinctiveness from the “evil” ones. One of them, Hüseyin Râci, summarized the popular discourse on the assumed, and probably factual, damages arising from the survival strategies of Mohadjirs in the temporary settlements they stayed in:

272. They burn the window frames and hang linen bags instead of glass.

273. Those uncouth ones burn wood in the brazier in the room, wash their laundry in the hall. (Hüseyin Râci Efendi 1975: 277)56

The popular discourse on Mohadjirs which, in time, took on a more and more pejorative tone, also consisted of typical stereotypes regarding the Roma; repeating these assumed features of the imagined personality of

55. “Konakta oturan muhacirler, dünyanın en büyük facialarını görmüş, gözleri önünde çocukları, babaları, kocaları öldürülmüş, anaları ve kardeşleri yakılmış insanlardı. Dünyada mukaddes ve aziz ne varsa hepsini terk etmiş bulunuyorlardı. Ahlakları, düşünce kabili-yetleri pek noksanlaşmıştı. Hiçbir şey yapmak tasavvurunda değillerdi. Açlıktan, soğuktan, sefaletten mütemadiyen kırılıp ölüyorlardı. Konağın kapılarını söküp yaktılar, ağaçlarını kestiler, tahtalarını kırdılar. Koca konak büsbütün korkunç bir hal bağladı. Ve bir gün muhacirler de çıkıp gitmiş bulundular.”

56. “272. Çârçupe demediler yaktılar − Cam yerine sonra çuval taktılar; 273. Odada mangalda yakarlar odun − Pislerini sofada yıkar o dûn.”

“evil” Mohadjirs, the author tends to distinguish between them and the “good” Mohadjirs, and ultimately reveals the source of their uncivilized habits – that they were actually Kıbtîs and a huge embarrassment to the “good” Mohadjirs:

274. Some dishonorable, evil and rich ones still travel to beg for aid. 275. They behave shamelessly at each door and beg for nothing. 276. They are not hungry but greedy. They are untrustworthy. 277. This ignoble and inferior race tarnished the mohadjirs’ name.

278. Good and evil are everywhere. There is flaw both in the axe and its stem. 279. Shameless “Kıbtîs” who are customarily dishonorable, brought shame upon the name mohadjir. (Hüseyin Râci Efendi 1975: 277)57

In many literary texts, it is possible to find traces of a relatively late popular discourse that includes contradictory depictions of the image of the Mohadjir, making it uncertain whether they were respectable, war victim Muslims, as was assumed in the beginning of the migration, or just dangerous and “shameless” Kıbtîs manipulating the religious and national sensibility of local Ottomans. In the documentary novel by Sâmiha Ayverdi, the small voice of a female servant of a mansion, who is resisting sharing waste with Mohadjirs, reflects on the pessimistic side of this dilemma:

It serves them right; what a good act it was not to let them pick through the mansion for food waste in the cellar. If they were trustworthy, they would not be immigrants. Who knows maybe they were “Çingene” or something like that. (Ayverdi 1973: 208)58

The testimony of another early republican intellectual, Ruşen Eşref Ünaydın, further reveals that even external observers were aware of the alien charac-teristics of the Mohadjir founders of the earliest teneke mahalles: “According to the mentality of Istanbulians in that period, “Mohadjir” meant a separate stratum. As if they were not Turks, as if they were not from the same land”

57. 274. Bir nice alçak kötü zenginleri − Yevmiye ardında gezer serseri; 275. Sokulur arsızlık eder her dere − Yüz suyu döker o deni yok yere; 276. Karnı tok imiş tutalım aç gözü − Dinlenilir şey değil asla sözü ; 277. Etti muhacirleri bed-nab hep − Böyle fürumaye ve süfli neseb; 278. Nik ü bedi her tarafın bulunur − Baltada da sapta da vardır kusur; 279. Kıbtî-i bi-şerm-i denâat-şiar − Verdi muhacir adına şin ü âr.

58. “Oh, ne iyi etmiş de kiler artıkları için o pis dilencileri köşke dadandırmamıştı. Adam olsalar muhacir olmazlardı. Kim bilir çingene miydiler neydiler?”

(Ünaydın 1960: 32).59 However, he also remained partly sympathetic towards the founders of “Mohadjir quarters” that consisted of “hovels reminiscent of village houses”:

These persons whose customs, way of speaking and living were different from us seemed to me very companionable. I used to go their houses; I was fascinated with their rolling out dough and especially their way of telling tales … As I recall my memories, I saw that those tales were probably the thing that gave me my first national concern, my first pleasure of travelling, my first enthusiasm for imagination. (Ünaydın 1960: 32)60

Which Mohadjirs founded teneke mahalles?

There is no exact explanation in the record books about the ethnic origin of the Mohadjirs. In accordance with regulations regarding the census, the officials who prepared the record books considered and, therefore, recorded Mohadjirs as a whole entity, without considering their ethno-social background. Nevertheless, in the record books, the occupation of the household heads for the majority of Mohadjirs is declared, and this data let us make an evaluation on their ethnic origin considering the local patterns of occupation and ethnicity in the Ottoman Empire.

According to the record book dated 1888, the heads of all founder households in Nishantashi Teneke Mahallesi were porters (hamal), and they were from Lovech (Lofça).61 Unfortunately, the specific occupational records of the Roma in Lovech could not be located during this research. However, there is an income-based record book (temettüat) on Kıbtîs who were living in tents (haymenişin) around Vidin, which was both historically and geograph-ically related to Lovech (Lofça). The record book was prepared in 1845,62 and in this period, Lovech was linked administratively to Vidin (Sezen 2006: 342). According to the record book, there were 222 Kıbtî household heads, and 29 of them were porters. More interestingly, all the porters in the central neighbourhoods of Vidin, except one Jew, were Kıbtîs (Selçuk 2013). Although

59. “İstanbul’un o vakitki zihniyetinde “muhâcır” başka bir tabaka demekti. Sanki onlar Türk değillerdi; ayni vatandan değillerdi.”

60. “Adetleri, konuşuşları, yaşayışları bizimkilerden başka türlü bu insanlar bana çok mûnis görünürlerdi. Evlerine giderdim; hamur açışlarına, hele masal anlatışlarına hayrân olurdum … Şimdi zihnimde araştırdıkça görüyorum ki, bana ilk millet acısı, ilk sayahat zevki, ilk hayâl hevesi veren şeyler belki de ilk bu masallardı.”

61. “Lofça muhâcirlerinden hamal Abdullah-Lofça muhâcirlerinden dul Ayşe Hatûn-Lofça muhâcirlerinden hamal İbrahim-Lofça muhâcirlerinden hamal Mehmed-Lofça muhâcirl-erinden Ali-Lofça muhâcirlmuhâcirl-erinden hamal Osman-Lofça muhâcirlmuhâcirl-erinden hamal Ömer-Lofça muhâcirlerinden hamal Mehmed.” BOA. Y.PRK.M.3.38.1.3.

this reveals the fact that the majority of porters in the central location of Vidin were Roma, further research is needed to confirm our argument more convincingly that, when all the population and income records belonging to Lovech are examined carefully, it would be possible to reveal the level of exclusivity of the occupation in the local context.

Occupational comparison does not work on the same level to detect the ethno-social origin of the founders of Coum-Capou Teneke Mahallesi, due to the more complex demographic structure of the locality. Twenty-Five Mohadjir families were the founders of Coum-Capou Teneke Mahallesi according to an archive document dated 1889.63 It is possible to learn their origin and subsistence ways from the record books dated 1892 and 1893. They were obviously more homogenous than their counterparts in Nishantashi. Nevertheless, families from Plovdiv (Filibe) and Chirpan (Çırpan), which was administratively linked to Plovdiv (Sezen 2006: 128), and Lovech (Lofça) were more numerous than the others. There were shoe repairers (kundura dikicisi), mobile vegetable sellers (küfeci) (Paspatis 2014: 76−7) or the load carriers with küfe, a kind of large basket, and carriage drivers (arabacı) among the household heads from Chirpan and Plovdiv, and carriage drivers and porters among the ones from Lovech.64 According to a record book dated 1840, 24 out of 192 Kıbtî household heads living in the central regions of Plovdiv were carriage drivers. And the others were working in menial or paid jobs such as porters (hamal), tanners (derici), servants (hizmet-kâr), or gravediggers (mezârcı), instead of traditional peripatetic occupations.65

The time gap between the record books from the 1840s and those of 1892−1893 necessarily weakens the reliability of an analysis depending on occupational comparison. However, there are also many more recent mentions in various sources which indicate a similarity between the occupations of Kıbtîs and the teneke mahalle founder Mohadjirs. For example, Said Bey, who prepared a report for the Sultan in 1891 about the overall situation of Kıbtîs all around the empire, particularly the Balkans, mentions Kıbtî porters as a more virtuous sub-group of the community (Uçar 2008: 133). Herbert writes in detail about the Balkan Gypsies in the beginning of the twentieth century depending on his own observations during a journey between 1903 and 1905 (Herbert 1906: vii). He mentions five Gypsy hamals in Sofia, whose weight-carrying performances were “incredible” (Herbert 1906: 48), with whom he consulted for the Romani language (Herbert 1906: 44). He also

63. “ol bâbda muhâcirîn-i merkume tarafından i’tâ olunarak ke-zâlik tesyîr-i savb-ı devletleri kılınan arzuhalde dahi kendüleri yirmi beş hâneden ibâret oldukları hâlde” BOA. DH. MKT.1671.48.1.1.19 Teşrin-i Evvel 1305 (31 November 1889).

64. BOA. İ.ŞE.2.30.

refers to a Gypsy vehicle driver with whom he travelled around the fortifi-cation in Pleven (Herbert 1906: 13). According to him, occupations such as horse-doctor, horse-dealer, harness-mender, cobbler, porter, and hawker were common among the Balkan Gypsies (Herbert 1906: 40). Those records are not exclusive, but they clearly indicate the presence of these occupations among Roma, and link what we know about the teneke mahalle founders and the Kıbtîs in the Balkans before the migration.

Oral records and references in literary texts are also considerable in this respect. One source, a retired taxi driver, born in 1935, and a member of the local lower-middle-class Armenian community, reflects on the external perception of the Coum-Capou Teneke Mahallesi; he explains the perception of the neighbourhood without any hesitation: “When we say ‘teneke mahallesi,’ we mean largely Romen citizens live there. . .” (Yılgür 2017a: 559).66 However, as we will see later, there were many others among the residents of the neighbourhood. There are similar oral records indicating the Romani origin of the founders of Nishantashi Teneke Mahallesi. Another source, an author and critic who lived in the privileged middle and upper-middle-class sections of the locality during his childhood and who left Nishantashi before the 1950s, reflects on the external perception of the quarter before its ethno-social heterogenization: he defines it as a “Çingene Mahallesi” exclusively to the extent that he uses the two terms almost interchangeably: “That place completely belonged to the poor: what we call a Teneke Mahallesi. More precisely, completely, Teneke Mahallesi is a place in where ‘Çingenes’ live” (Yılgür 2013: 42−3). It is possible to find similar allusions in literary works on the quarter. Famous Turkish novelist Refik Halit Karay, after a well-detailed description of the neighbourhood’s physical location claimed it to be “Çingene Mahallesi” (Gypsy Town) in his novel, Sonuncu Kadeh, first published in 1965 (Karay 1994: 156−7). Also, Saadet Timur Ulçugür (1974: 349) describes the territory as a “former ‘Çingene’ towns behind Nishantashi” in her short story Yenilenmek.

The occupational comparison and the oral and literary records considerably indicate the Romani origin of the majority of the founders of the two teneke mahalles. However, in order to specify the branch and community networks they belonged to, and their way of self-identification, further research is needed. Nevertheless, there is a Roma community in Bulgaria today that adopted the Turkish language, and whose preferred identity is Turkish, which is generally known as “Millet,” literally meaning a community with

66. In contemporary Turkey, this is a politer way of saying Çingene, and is actually a misuse of Romani self-identification that indicates the public misunderstanding and misinterpretation of similarity between the original Romani term Romanlar and Rumen or Romen “Romanian.”

similar qualities, and particularly religion, in the Ottoman case. However, they were denominated as “Çingene” by the ethnic Turks (Marushiakova and Popov 1999: 85). Today, in Plovdiv, Lovech, Ruse, and some other places, it is a common phenomenon for Muslim Romanies to partially or entirely lose their own language and adopt a preferred Turkish ethnic identity (Marushiakova and Popov 2012: 4). This seems similar to the Roma immigrants, in that they preferred the more neutral Mohadjir identity instead of Çingenelik.

The Armenian or Lom/Bosha neighbours of Roma in Coum-Capou Teneke Mahallesi

Although they were the oldest, the Muslim Roma were not the only group in both teneke mahalles. The record books reveal the fact that they lived in the vicinity of the local poor, who had needed housing even before the war, in teneke mahalles. According to the record books dated 1892 and 1893, Christians, largely Armenians except for one Greek family, constituted half of the population of Coum-Capou Teneke Mahallesi. Twenty-six of the 52 families were Christians in 1892, and the number decreased to 22 by 1893. Even though a few of them were from Anatolian cities with a considerable Armenian population, the majority of the local Christians were born in Istanbul.

The relations between Christian dwellers of teneke evler and middle and lower-middle-class Armenians were not perfect. There is a document in the Ottoman archives indicating the conflict between Armenian residents of the Coum-Capou Teneke Mahallesi and the parishioners of a local Armenian church. According to the document, the church claimed that the territory on which the poor Armenians built their houses actually belonged to the church, and they applied to the Ottoman administration for the eviction of the Armenian residents in Coum-Capou Teneke Mahallesi.67 Lower-middle-class Armenians’ perceptions of the residents of Coum-Capou Teneke Mahallesi are quite similar:

There were even some Armenians there. There are some Armenians in Anatolia, “Rumen,” “Posha.” They are being called “Posha.” Posha means “Çingene.” It is the same. They live in Yozgat. They live in Çorum. They are just like “esmer vatandaş”

67. “Kumkapı civârında Şehsuvar Bey Mahallesi’ndeki Ermeni Kilisası akarâtından bulunan arsaya inşâ idilmiş olan yirmi dört barakada sâkin olanlar Der-saâdet ahâlî-i Hıristiyânîyesinden olub cümlesi birer san’atla meşgul oldukları ve burada mezkûr arsaya tuğla sergisi inşâ idilmiş olmasıyla barakalarla serginin oradan kaldırılması Kilisa cem’iyyeti a’zâsı tarafından istid’â olundığı cihetle.” BOA. DH.MKT.1907.115.1.1. 4 Kânûn-ı Evvel 1307 (16 December 1891).

[“black citizen” a pejorative term used for Roma and other peripatetics]. They are Armenian Posha. (Yılgür 2017a: 564−5)

This generally underlines the teneke mahalle’s residents’ Armenian origin, but it also maintains a distance between them and uses the others’ assumed “Posha” (Poşa) identity to emphasize their difference.

“Bosha” is a term used by surrounding communities in Transcaucasia to identify the Lom peripatetics, and they were similarly known as “Posha” in north-eastern Turkey (Marushiakova and Popov 2014: 2). Lom communities have been reported to speak Armenian but also use a lexicon of Indo-Arian words for internal communication (Matras 2011). The traditional occupation of the Posha/Lom communities is believed to have been sieve-making, and their gender-based labour division is also very famous in that the sieves produced by the men were sold by women (Marushiakova and Popov 2016: 72). Posha peripatetics have had a long history in Istanbul as a small ethnic minority. There are some mentions of a sieve-maker community called “Κατζίβελος” in Byzantine Istanbul in the fourteenth century sources (Soulis 1961: 151). Although further research is needed to link them to the subsequent centuries’ Poshas, there is no doubt about the presence of a peripatetic niche of sieve makers in Istanbul and the surrounding rural settlements during that era. Later sources are clearer about the ethnic identity of local sieve makers. The seventeenth-century historian Eremya Çelebi Kömürciyan reported that Armenian Posha were living around the Topkapı ramparts. Some of them converted to Islam, and their traditional occupation was sieve-making (Kömürciyan 1998: 21). According to Pamukçiyan, Patriarch Hagop Nalyan allowed marriages between Armenians and Armenian Bosha in the eighteenth century, and this caused the local Bosha to be intermingled with other Armenians and, ultimately, to disappear (Pamukçiyan 2002: 5). This kind of mixed-marriage in more recent times has also been reported by local sources in Coum-Capou: “M… and A…, their mother was also Posha. Armenian Posha” (Yılgür 2017a: 22). Thus, contrary to the claim of Pamukçiyan, it appears that the Armenian Posha in Istanbul did not disappear completely; but the line between them and the poorest segment of Armenians became uncertain in time and a considerable number of them converted to Islam.

According to the record books of 1892 and 1893, the Christian residents of the teneke mahalle subsisted through many different occupations. There were no sieve makers among them, and this proves that these Christians were not the typical Armenian Bosha who had lived around Topkapı for long centuries. There were some metal workers among them, but this does not necessarily substantiate their peripatetic origin. Paspatis claims that