A+ArchDesign

Istanbul Aydın University

International Journal of Architecture and Design

Year: 2015 Volume: 1 Number: 1

İstanbul Aydın Üniversitesi

Mimarlık ve Tasarım Dergisi

Advisory Board - Hakem Kurulu

Prof. Dr. Bilge IŞIK, Istanbul Aydın University, Istanbul, Turkey

Prof. Dr. Nezih AYIRAN, Cyprus International University, North Cyprus

Prof. Dr. Mauro BERTAGNIN, Udine University, Udien, Italy

Prof. Dr. Gülşen ÖZAYDIN, Mimar Sinan University, Istanbul, Turkey

Prof. Dr. Aykut KARAMAN, Kemerburgaz University, Istanbul, Turkey

Prof. Dr. Sinan Mert ŞENER, Istanbul Technical University, Istanbul, Turkey

Doc.Ing. Ivana ZABICKOVA, Brno Uni.of Tech., Brno, Czech Republic

Prof. Dr. Neslihan DOSTOĞLU, Istanbul Kültür University, Istanbul, Turkey

Prof. Dr. Zekai GÖRGÜLÜ, Yıldız Technical University, Istanbul, Turkey

Prof. Dr. Salih OFLUOĞLU, Mimar Sinan University, Istanbul, Turkey

Prof. Dr. Şaduman SAZAK, Trakya University, Istanbul, Turkey

Prof. Dr. Kamuran ÖZTEKİN, Doğuş University, Istanbul, Turkey

Prof. Dr. R.Eser GÜLTEKİN, Çoruh University, Artvin, Turkey

Prof. Dr. Marcial BLONDET, Pontifical Catholic University of Peru, Peru

Prof. Dr. Saverio MECCA, University of Florence, Florence, Italy

Prof. Dr. T. Nejat ARAL, Istanbul Aydın University, Istanbul, Turkey

Prof. Dr. Murat ERGINOZ, Istanbul Aydın University, Istanbul, Turkey

Prof. Dr. Güzin DEMIRKAN, Bozok University, Yozgat

Assoc. Prof. Müjdem VURAL, Eastern Mediterranean University, North Cyprus

Assoc. Prof. Murat TAŞ, Uludağ University, Bursa, Turkey

Assist. Prof.Dr. Dilek YILDIZ, Istanbul Technical University, Istanbul, Turkey

Editor-in-Chief - Yazı İşleri SorumlusuNigar Çelik Editor - Editör Prof. Dr. Bilge IŞIK

Editorial Board - Editörler Kurulu Prof. Dr. Bilge IŞIK (Editor - Editör) Yard. Doç. Dr. Gökçen Firdevs YÜCEL CAYMAZ Yard. Doç. Dr. Ayşe SİREL

Cover Design - Kapak Tasarım Nabi SARIBAŞ

Administrative Coordinator - İdari Koordinatör Nazan Özgür

Technical Editor - Teknik Editör Hakan Terzi

Publication Period - Yayın Periyodu Published twice a year - Yılda İki Kez Yayınlanır June - December / Haziran - Aralık

Year: 1 Number: 1 - 2015 / Yıl: 1 Sayı: 1 -2015 ISSN: 2149-5475

Correspondence Address - Yazısma Adresi

Beşyol Mahallesi, İnönü Caddesi, No: 38 Sefaköy, 34295 Küçükçekmece/İstanbul Tel: 0212 4441428 - Fax: 0212 425 57 97 web: www.aydin.edu.tr - e-mail: aarchdesign@aydin.edu.tr Printed by - Baskı

Matsis Matbaacılık, Teyfikbey Mahallesi, Dr.Ali Demir Caddesi No: 51 34290 Sefaköy/İSTANBUL - Tel: 0212 624 21 11 - Fax: 0212 624 21 17 E-mail: info@matbaasistemleri.com

Project Implementation in Public Open Spaces: Saraçlar Street Urban Design Project, Edirne-Turkey

Kamusal Açık Mekanda Proje Uygulaması: Saraçlar Caddesi Kentsel Tasarım Projesi, Edirne-Türkiye

Ayşe SİREL... 1

Materials Used in the Construction of Village House in Van

Van Köy Evi Yapılarında Kullanılan Malzemeler

Hakan İRVEN... 15

Customs and Its Role in Tourism

Gümrük ve Gümrüğün Turizmdeki Yeri

Armin Saei LEYLONAHAR... 25

Search for Hidden Light in the Pyramids

Piramitlerdeki Saklı Işığın Araştırılması

The international journal A+ArchDesign is expecting manuscripts worldwide, reporting on

original theoretical and/or experimental work and tutorial expositions of permanent reference

value are welcome. Proposals can be focused on new and timely research topics and innovative

issues for sharing knowledge and experiences in the fields of Architecture- Interior Design, Urban

Planning and Landscape Architecture, Industrial Design, Civil Engineering-Sciences.

A+ArchDesign is an international periodical journal peer reviewed by Scientific Committee. It

will be published twice a year (June and December). Editorial Board is authorized to accept/reject

the manuscripts based on the evaluation of international experts. The papers should be written in

English and/or Turkish.

The manuscript should be sent in electronic submission via. http://www.aydin.edu.tr/aarchdesign

1 Bu makale 2005 yılında İTÜ ve TMMOB Şehir Plancıları odasının birlikte düzenlenmiş oldukları 8. Dünya Şehircilik Günü “Planlamada Yeni

Saraçlar Street Urban Design Project, Edirne-Turkey

Ayse Sirel

Faculty of Architecture and Design, Department of Architecture,

Istanbul Aydın University, Beşyol Florya, Istanbul/Turkey

E-mail: aysesirel@yahoo.com.tr

Abstract: Public open spaces are an integral facet of urban life and have social, physical, and symbolic

dimen-sions. In particular, public spaces deemed to be focal points of historical cities have been adversely affected in recent years by globalization and societal transformations. Many public open spaces, including squares, avenues, and boulevards, no longer reflect the cultural identity of “place,” and have instead become faceless, generic spaces. This situation has given rise to the necessity of studies designed to improve the quality of public places in the urban environment. In this paper, usage problems associated with public open spaces in historical city centers are examined. “Public open space” and “urban interface/façade” concepts are defined and method-ologically explored. In addition, the paper discusses problems observed by citizens, the characteristics of these problems, and how these problems impact the urban environment. The regulatory principles of the “Saraçlar Street Urban Design Project” in Edirne, Turkey, are presented as an example of public space planning for a historical city. The project aims to enhance the environmental quality of Saraçlar Street, which is commercially and socially the most important public space in Edirne, by transforming it into a pedestrian-only area. The study concludes with an assessment of Saraçlar Street’s problems prior to pedestrianization and its status and contri-butions to city life after pedestrianization.

Keywords: Public open space, interface, urban design, pedestrianization, Turkey, historic cities

Kamusal Açık Mekanda Proje Uygulaması: Saraçlar Caddesi Kentsel Tasarım Projesi, Edirne-Türkiye

Özet: Kentsel olayların süregeldiği kamusal açık mekanlar; sosyal-fiziksel-simgesel boyutlarıyla ve üstlendikleri

işlevlerle ön plana çıkan kent parçalarıdır. Tüm dünyada ve ülkemizde son yıllarda yaşanan değişim ve dönüşüm sürecinde, özellikle tarihi kentlerin odak noktaları sayılan kamusal dış mekanlar olumsuz etkilenmiştir. Bazen meydan, bazen cadde veya sokak olabilen kamusal açık mekanlar o “yer”in kimliğini yansıtan anlamlı mekan-lar olmaktan çıkmış, kimliksiz mekanmekan-lar haline dönüşmüştür Bu durum, kamusal mekanmekan-larının yeniden kente kazandırılması için, çevre kalitesini geliştirmeye yönelik (üçüncü boyutta arayüzleri de içeren) kentsel tasarım proje çalışmalarının gereğini de doğurmuştur. Bu çalışmada tarihi kent merkezlerindeki kamusal açık mekanlar ve kullanım sorunları incelenmektedir. Metodoloji olarak öncelikle “kamusal açık mekan” ve “kentsel ara-yüz/cephe” kavramları tanımlanmıştır. Kentte yaşayan insanlar için, çevreyi algılayabilecekleri mekanlar olma özelliği taşıyan bu alanlarda gözlenen sorunlar ortaya konmuştur. Çalışmanın örnekleme kısmında ise; kamusal alan düzenlemesinin bir örneği olarak; Edirne’de “Saraçlar Caddesi Kentsel Tasarım Projesi”nin düzenleme ilkeleri anlatılmıştır. Proje ile, Edirne’nin ticari ve sosyal açıdan en önemli kamusal açık mekanı olan Saraçlar caddesinin yaya alanına dönüştürülerek, çevre kalitesinin arttırılması amaclanmıştır. Çalışmanın sonunda Sa-raçlar Caddesinin; yayalaştırma öncesi sorunları ile yayalaştırma sonrası kente katkıları değerlendirilmiştir.

1. INTRODUCTION

The personal and cultural business of individuals in “public places” within cities forms the bedrock of societal life. In urban environments, residents gather in streets, squares, or parks to converse and freely express themselves. Public open spaces serve as integrative environments where cultural mores are trans-ferred from generation to generation and socialization is improved. However, the public spaces in today’s cities are unable to satisfy the expectations of city dwellers. These open areas, which are increasingly being developed as parking lots or throughways for motorized vehicles, have started to lose their appeal as spaces where people can wander easily or explore the environment. Historical city centers are under particular pressure from intensive use, and problems of urban decay, aesthetic depreciation, and unwelcoming open space have become significant problems [1], giving rise to the need for a plan to revive the allure of public open spaces in cities.

In this paper, usage and planning problems associated with public open spaces are explained. The study consists of two parts. In part 1, the theoretical underpinnings of “public open space” are described. In this context, the concept of an “urban interface-façade” functioning as a border element between public open space and structured areas in historical city centers is scrutinized. In part 2, the principles of the “Saraçlar Street Urban Design Project” are described as an example of public space arrangement. Location, design status, spatial functions, and existing problems with the horizontal and vertical planes (i.e., plan and façade) are identified for Saraçlar Street, which serves as a public open space in the historical city center of Edirne, Turkey. The study concludes with a comparison of the street and its contributions to the city before and after pedestrianization.

2. THE CONCEPT OF “PUBLIC OPEN SPACE”

In urban settlements, places where common or personal requirements are met as a result of collective living are called public open spaces. Structured and unstructured spaces are divided into public or private spaces depending on land use zoning [2]. The concept of public open space is emphasized in this study due to its relevance to the research aims.

Public space studies began in Europe in the 1960s, but even today, there remain different viewpoints on the concept and no agreed-upon precise definition. Although political scientists and architects/urban planners have different conceptions of public open space, the fundamental characteristics often overlap. Çubuk (1989) define public space as functional areas that are accessible by anyone and have symbolic meanings [3]. Rowe (1997) refers to public space as areas that can be directly accessed and which satisfy the key requirements of human socialization [4]. Keleş (2012) characterizes public places as laboratories for deter-mining the limits of living together, moral rules, and life direction [5]. Madanipour (2013) refers to public open space as areas that have always been an integral part of the city [6].

The common point in the definitions above is that public spaces feature discourse, action, and emphasis on “sociality.” The most significant feature of public space is that it is open to all citizens: indeed, it manifests the spirit of a city with its physical form and social fabric [7]. All non-private housing or business gather-ing areas (e.g., squares, avenues, streets, parks) may be referred to as public. In this paper, “public outdoor place” or “public open space” concepts are used interchangeably. Public places are essentially open spaces in which people gather to conduct all kinds of social and economic objectives [8, 9]. On a broader scale, public outdoor spaces may be seen as integrative environments where culture is transferred from generation to generation. Public space may serve as a dynamic passage area (e.g., avenue, street, waterway, channel) or statically qualified assembling area (e.g., square), depending on its spatial properties [10]. Public outdoor places are also associated with the structures encircling them.

In order to nurture collective life [11], open urban places should allow all for all kinds of social activities and at the same time should be in harmony with the topographic character of the natural environment. Conversely, structures intended to restrict public space should be expressed in such a way that establishes a collective identity. In recent decades, globalization has brought about a sea change in social, cultur-al, and economic processes. During this transformation, many public outdoor spaces deemed to be focal points have been adversely affected (i.e., they have ceased to reflect the identity of “place” and no longer contribute to the lives of city dwellers). Urban planning studies for historical cities in Turkey have mostly adhered to a two-dimensional ground arrangement strategy (i.e., Urban Plan). The desired results could not be attained except in instances of improvement for “urban interfaces” that make up the collective identity of building façades, which limits public engagement with the third dimension. In the following section, the interface phenomenon, which is a spatial consideration where the physical and societal frames of city life intermingle [12], is analyzed in detail.

3. THE INTERFACE CONCEPT: A Problematic Field in the Public Spaces of Historical Cities

The interface phenomenon refers to architectural façades that limit urban open places [10]. It is a boundary element that delineates structured areas in urban outdoor places. Interfaces are the transition zones between “urban public outdoor places” and “architectural structure forms”; they determine how the urban fabric will be read and establish visual and functional links between private indoor places and public outdoor spaces [13].The interface, which does not emerge uniformly in historical cities, is a physical formation shaped through local characteristics (e.g., space, architectural typology, construction materials, form, and aesthet-ics) and communal values.

Meanwhile, the interface phenomenon is composed of façades from a societal standpoint. That is, although transition zones may be an indication of a society’s personality, they are also the reflection of the communal differences of a city [12]. Interfaces, which have evolved through different cultural phases over the course of hundreds of years, constitute the most obvious evidence of urban evolution. The main elements that change are determined by systemic factors such as technology availability, construction materials, legal obligations, zoning laws, and aesthetic preferences.

As stated above, public outdoor spaces are integrative environments where culture passes from generation to generation. In recent years, interface characteristics that confer the unique identity of historical city cen-ters have been supplanted by unqualified structures as a result of intensive use pressure. In fact, deteriora-tion of public outdoor spaces may be seen in both pattern (funcdeteriora-tion-interface) and structural (plan-façade) scales, which also reduces citizens’ regard for these areas as common ground.

Urban interfaces play a major role in determining the degree of negative impact suffered by public places. “Urban Plans” are an inadequate prescription to solve problems with the current planning system in Turkey. “Urban Design Project” studies, which ostensibly address the third dimension of place, were carried out in order to produce more appealing urban interfaces [14].An initiative of the public administration, these stud-ies aimed to improve environmental quality by combining function with aesthetics. Spatial relationships were examined with the understanding of particular systems in the regulation of interfaces, which serve as sub-elements of public space. While examining the interface layout, different techniques were used to separate façades by the components that were utilized during construction [12].Here, it should be noted that the architectural characteristics of façades that form the interface for existing historical structures should not be thought of as badges (i.e., imitations, motif repetitions, etc.) to be attached to planned buildings [15].

The process of the aforementioned technical studies for regulation of interfaces is detailed below:

• Using photographs and drawings, a determination is made of which façades (interface) of existing structures restrict place.

• Next, textural-structural-volumetric-legal analysis studies are conducted.

• A determination of design principles is proposed. Fundamental inclinations of the design in deter-mining formal and structural relations between historical structures are emphasized. Required pro-tections and new buildings to be constructed on empty parcels remaining among existing structures are identified.

• Improvements for current degraded historical façades are identified. • Finally, a design guide is prepared.

Urban design projects allow for the integration of subjective personal attitudes in plans to enhance the value of public outdoor place [16].

4. CASE STUDY: The Saraçlar Street Urban Design Project and Contributions to Urban Life 4.1 The History and Urban Development Process of Edirne

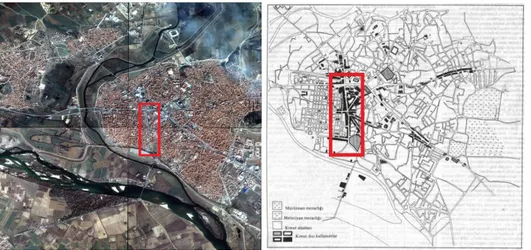

Edirne is located in the far northwestern region of Turkey. Greece and Bulgaria are located to its west (Fig-ure 1). The city, which dates back to prehistoric times, has been the birthplace of various civilizations and has long been a community focal point for the region. The city was established in 700 B.C. by the Odrysian kingdom [17]. The city then came under control of the Romans in A.D. 46, and then fell under rule of the Byzantine Empire in A.D. 375 when the Roman Empire was partitioned. The name of the city, which had been Adrianapolis until this date, was converted into Edirne when the Ottomans conquered the city in 1362 [18].

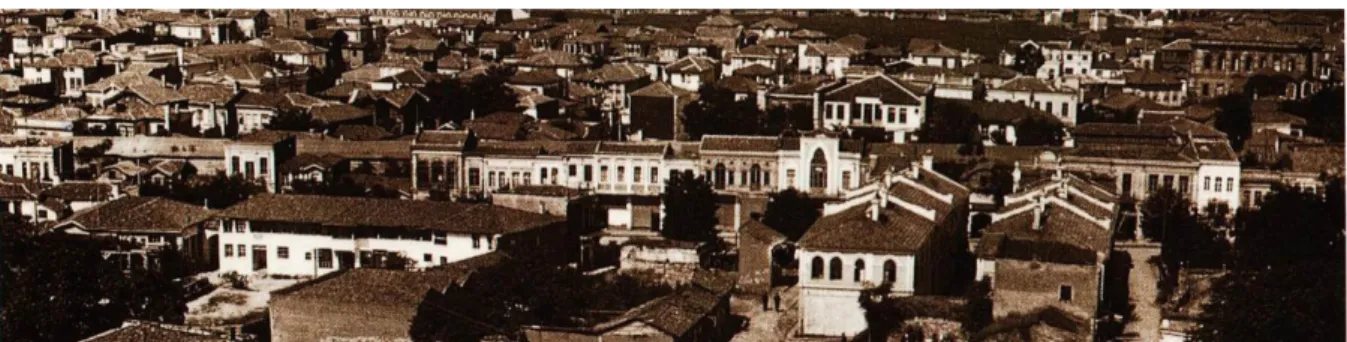

Edirne has been a significant settlement for centuries by dint of its geopolitical location. The city has histor-ic neighborhoods located on the western side of the Tunca River and a settlement (Castle Interior–Exterior) in the arc shaped by the Tunca River (Figure 2). Edirne’s importance increased dramatically after the Turks conquered it: the city served as capital of the Ottoman Empire for about one century. The city, with its mag-nificent monuments and stately civil architecture, represents the height of Ottoman architecture (Figure 3).

Figure 2. The historic macroform of Edirne. Figure 3. Saraçlar Street and its environs.

Edirne underwent many zoning transformations from the Republican era to the present. These numerous zoning plans did not allow for a holistic plan to control and protect the historical core of the city and its immediate surroundings. In other words, conservation remained at the scale of individual structures, not the entire urban fabric. Historical, cultural, and aesthetic properties could not be revealed completely for some time, which is a travesty considering Edirne is Turkey’s gateway to Europe. “Spatial transformation” projects, which are increasingly being supported, have begun to contribute to the socioeconomic devel-opment of the city by re-purposing its many historical places. One project, the “Saraçlar Street Pedestrian Zone Project”, an endeavor carried out by the Trakya University Revolving Fund at the request of Edirne Municipality [19], is described below.

4.2 Saraçlar Street’s Position in the City

Saraçlar Street parallels the east walls of Edirne Castle, which is practically indistinguishable today. The street is approximately 700 meters long and is the most important public open space from social and com-mercial viewpoints. Many comcom-mercial structures possess invaluable cultural/historical assets that survive to the present day on the street (Figure 3–5).

This route through Edirne, which has been a significant throughway since the Byzantine era, gained more importance after being conquered by the Ottomans. Saraçlar Street is connected to New Palace through Hükümet and Karanfiloğlu Streets toward the north and to Karaağaç through Tunca and Meriç bridges to-ward the south. The importance of Saraçlar Street is further increased due to its link with Istanbul Road in the east, and roads opening outside of the walls coming from Kaleiçi in the west. The entire region, which was previously situated next to Saraçhane Bridge, was renamed “Yeni Saraçhane” in the late sixteenth century and features the Saraçlar Bazaar [20]. Alipaşa Covered Bazaar, which extends parallel to the street along its northern side, is a major support for commercial activity in the area (Figure 5).

Figure 4. The general appearance of Saraçlar Street in the early twentieth century.

Figure 5. Saraçlar Street and Alipaşa Bazaar (prior to pedestrianization).

4.3 The Problems of Saraçlar Street Prior to Urban Design

a) Structural problems

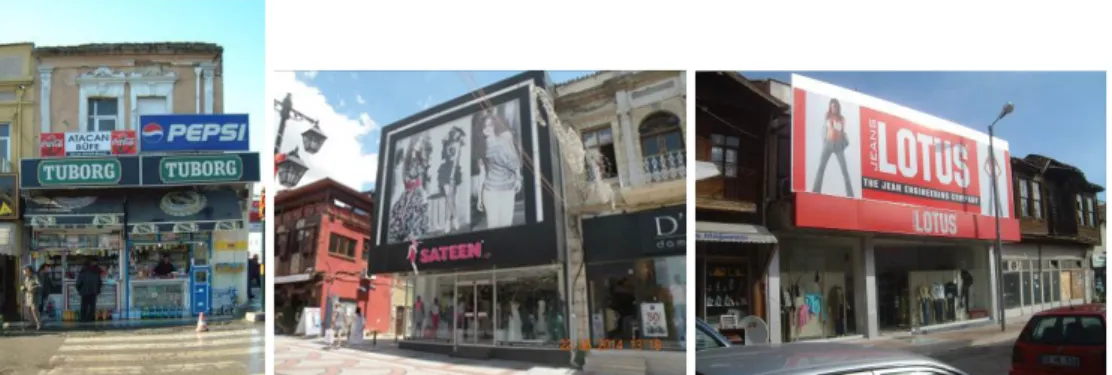

• Violations of building heights designated by the zoning plan (Figure 6) • Alterations made to unique façades (Figure 7)

• Frequent changes made to the initial zoning plan

• Problems matching color, material, and dimensional complexity

Figure 7. Façade changes along Saraçlar Street.

b) Problems related to urban fabric

• Some new structures clash with the historical silhouette of existing civil architectural structures (Figure 8)

• Visual pollution caused by advertising billboards (Figure 9)

• Visual pollution created by elements not compatible with historical structures (e.g., air condition-ers, sun blinds, antennae)

• Asphalt paving on the street

Figure 8. New architectural formations along Saraçlar Street.

Figure 9. Visual pollution along Saraçlar Street.

c) Problems associated with transportation

• Intense vehicle traffic on the street restricts pedestrian movement and daily life (Figure 10)

• Vehicles parked on sides of the street create blockages and impair pedestrian movement (Figure 11) • Pedestrian safety problems

d) Legal problems

• There is an inventory of “immovable cultural assets” located on Saraçlar Street

• Absence of a “development plan” prepared specifically for conservation of structures on Saraçlar Street.

Figure 10. Heavy motor vehicle traffic along Saraçlar Street

Figure 11. Parking problems along Saraçlar Street.

4.4 Design Principles for Saraçlar Street

The Saraçlar Street Urban Design Project is composed of two basic fields of study that complement each other [19]. These are;

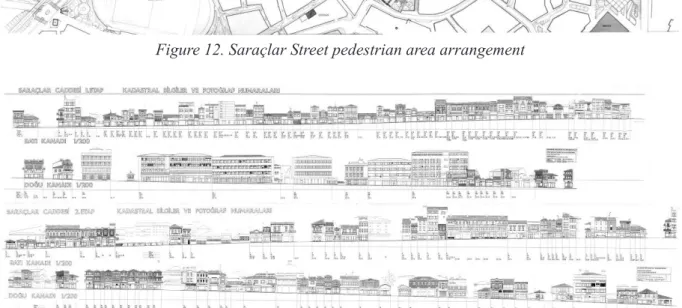

Pedestrianization and pedestrian area arrangement

Contemporary urbanism and city planning science advocate for the conservation and planning of city cen-ters. In general, these areas are the focal point of a city’s social, economic, and cultural activities, and there is a constant quest to improve existing structures as well as create new opportunities for sustainable urban development. Today, the worldwide trend is toward freeing city centers from vehicle traffic and creating more open space. In Europe, pedestrianization is already well underway to rescue historical city centers from the impacts of motor vehicle traffic. Municipalities in Turkey have only just started to follow this approach. For Edirne, street closures would allow pedestrian access to

cultural events and amenities; this approach has become an obligation in order for the historical city center to maintain its vitality. Planning concepts for pedestrianization included (Figure 12):

• Streets paralleling Saraçlar Street, which will be closed to motor vehicle traffic, have been desig-nated as transportation conduits

• Bicycle paths and bicycle parking spaces will line the street

• The continuity of pedestrian circulation will be ensured by interrelating passages, courtyards, and covered bazaars

• Trees on the street will be conserved and additional new green areas will be created • Recreation areas and outdoor cafes will be erected within walking distance of green areas.

Façade rehabilitation (regulation of interfaces)

Significant architectural differences existed between the interfaces of the two wings (two sides of the road) bounding the section of Saraçlar Street that was to be pedestrianized. This condition substantially affected the spatial function of Saraçlar Street. For example, buildings with three or less stories (many of which had immovable cultural assets) had narrow façades with a width varying between 3 to 6 meters at the western wing, adjacent to Alipaşa Bazaar. On the eastern wing, other than the partially conserved regions, 4 to 5 story buildings with wide façades dominated, resulting from an arrangement for increasing the width of the street in the 1970s (Figure 13). The most important spatial problem of Saraçlar Street was façades that dominated the street in general and created a lack of harmony with opposing façades.

Figure 12. Saraçlar Street pedestrian area arrangement

The main objective of interface arrangement for structures bounding Saraçlar Street was to eliminate visual pollution and to reclaim lost cultural assets. To achieve this goal, the following strategy was proposed:

• Determine the current situation: the façade silhouette of all structures restricting both sides of

Saraçlar Street was prepared at a scale of 1/100. Additionally, photographs, maps, and perspective drawings with regard to various eras were compiled into an album.

• Perform textural, structural, volumetric, and legal analyses: features such as horizontal and

ver-tical traces, proportion, contrast, layout, occupancy, and material and color of each façade were revealed. Restitution for the interface on both sides of Saraçlar Street was determined by consulting the album (particularly photographs from previous eras). Similarities and differences in building elements and interventions enacted up to the present day based on urban fabric and structures were identified. As a result of the aforementioned documentation study, it was determined that many structures with immovable cultural assets had been demolished or renewed their façades so as to become unrecognizable.

• Determine the directive design principles: in light of the studies described above and information

and documents examined, structures and parcels facing the street were classified in the following manner:

o Structures possessing immovable cultural asset qualifications

o Structures erected after demolition that had sufficient identifying information (e.g., photo-graph, building survey) regarding their façades

o New structures and empty parcels without information in respect to their history.

The main tendencies of the “Urban Design Project” were emphasized for these three categories. According-ly, for extant degraded historical façades it was proposed:

• To remove structural changes contrary to unique architectural elements on building façades • To remove elements that exceeded the floor height stipulated or which were constructed in

viola-tion of the zoning plan and without license

• To remove elements like eaves, sun shades, chimneys, etc., added to façades

• To remove devices like air conditioners, antennae, etc., added to façades or to relocate them as to be invisible

• To bring advertising billboards in compliance with the “Edirne Municipality Advertising, Publicity and Promotion Regulation”

• To perform necessary repairs on structures with aesthetic problems (e.g., plaster shedding, joinery deterioration, color conflicts).

Preparation of design guide

An “Urban Design Guide” containing details regarding the decisions and standards regarding Saraçlar Street and the “Edirne Pedestrian Zones Regulation” has been published. The guide specifies usage fun-damentals for Saraçlar Street and other pedestrian areas in light of the aforementioned studies. The goal in producing the guide is to ensure implementation by Edirne Municipality, so as to ensure uniform rules are enacted for historical areas.

5. CONCLUSION AND ASSESSMENT

Public open spaces have social, physical, and symbolic dimensions. These outdoor places often serve as the focal points of historical cities, but they have ceased to be meaningful places to city dwellers due to the rapid urban changes of recent years. In many cases, public spaces have turned into faceless areas that are seldom or never used, which diminishes society and limits the social outlets of city dwellers. This situation has catalyzed a new urban planning agenda that attempts to sustain historical and cultural value through conservation. Urban design project studies that combine function with aesthetics have been launched to improve environmental quality.

Pedestrianization functions, built with the correct dynamics, are of vital importance to preserving for his-torical city centers that teem with commercial activities. Pedestrianized zones enhance the quality of life for citizens (by generating solutions with respect to pedestrian and vehicle traffic) as well as the entire city; when implemented correctly, pedestrian-only zones can be a very effective tool for urban planners.

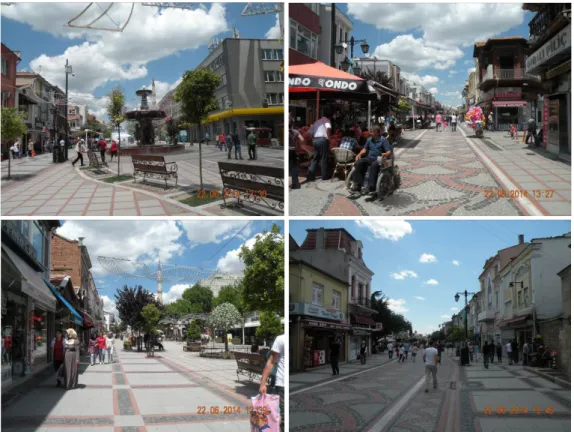

Saraçlar Street, the sampling area of this study, is the center of commercial and social life in Edirne, Turkey. The street experiences intense motor vehicle traffic, giving rise to many concerns about pedestrian safety. When social, cultural, communal, and commercial activities were taken into consideration, it was obvious that human beings were the driving force of activity along the length of the street. Assuming accessibility to events and amenities is a fundamental human right, it was the obligation of city government to conserve and maintain the vitality of the city center. Accordingly, an Urban Design Project dedicated to the pedestrianiza-tion of Saraçlar Street was prepared by Edirne Municipality in 2003. The project, which provides for “city dwellers’ rights” prescribed by a “European Urban Charter”and the preservation of historical and cultural assets, was conducted with the assistance of the Trakya University Revolving Fund. Saraçlar Street was pedestrianized in 2008 in accord with the principles of the Urban Design Project. After pedestrianization, city dwellers reported experiencing diminished environmental pollution and noise as well as more events ensuring the development of social, cultural, and communal relations. Moreover, property values grew and the region became more of a nexus for economic activity in the region (Figure 14).

A questionnaire measuring the satisfaction with the transformation of the area into a pedestrian area was distributed to people using the street and shop owners. The study was conducted with two groups consisting of 50 pedestrians and 50 shop owners selected randomly. Results showed that 100% of shop owners were satisfied after pedestrianization, and 92% of users/pedestrians were satisfied [21]. Based on the findings, it was concluded that Saraçlar Street acted as a place for “socializing, sharing, recreation, wandering, shop-ping, and walking,” and that the pedestrianization project was in compliance with these objectives.

Figure 14. Saraçlar Street after pedestrianization.

Overall, the project was deemed a success, but there were some negative observations associated with the project going beyond its stated scope. These issues included:

• Implementation regarding the interface improvement (rehabilitation) within the scope of the Urban Design Project.

• Decorative items selected by the municipal administration performing the implementation, not those proposed by the plan, were used (seating, lighting elements, pools, etc.).

• Commercial enterprises were permitted to settle on the street haphazardly rather than in locations that were identified in the project plan.

• Cyclists riding in an uncontrolled manner pose a danger to pedestrians because the bicycle path and bicycle parking elements proposed in the project were not implemented.

The completion of interface rehabilitation work and correction of other deficiencies in accordance with the Urban Design Project and design guide will further enrich the public spaces of Edirne city.

REFERENCES

[1] Bilsel, A., Bilsel, G., Bilsel, C., 1991. “Kentsel Kamu Alanlarının Düzenlenmesinde Kentsel Tasarım

Tekniğinin Kullanımına Planlama Bütününde Kuramsal Yaklaşım”, Kamu Mekanları Tasarımı ve Kent Mobilyaları Sempozyumu, 15-16 Mayıs 1989, MSÜ-Mimarlık Fakültesi, İstanbul, s.49-51.

[2] Özaydın, G., Erbil, D., Ulusay, B., 1991. “Kentsel Kamu Alanlarının Düzenlenmesinde Kentsel

[3] Çubuk, M., 1989. Kamu Mekanları ve Kentsel Tasarım, Kamu Mekanları Tasarımı ve Kent Mobilyaları

Sempozyumu, 15-16 Mayıs 1989, MSÜ-Mimarlık Fakültesi,İstanbul, s.15-17.

[4] Rowe, P. G., Civil Realism, MIT Press, Massachusetts Institute of Technology, Cambridge,

Massachu-setts

[5] Keleş, R., 2012. “Kamusal Alan, Kentleşme ve Kentlilik Bilinci”, Güney Mimarlık, Sayı:10, s.10. [6] Madanipour, A., 2013. “Whose Publıc Space?”, First Future Of Places International Conference On

Public Space And Placemaking, Sweden 24-27 june, Stockholm, s.33-43.

[7] Akay, A., 1997. Postmodern Görüntü, Bağlam Yayıncılık, İstanbul.

[8] Kostoff, S., 1991. The City Shaped: Urban Pattern and Meanings Through History, Boston: Bulfinch

Press.

[9] Şener, H. ve Yıldız, D., 1999. “Kentsel Mimari ve Mekana Katkı”, Kentsel Tasarım: Bir Tasarımlar

Bütünü-Ulusal Kentsel Tasarım Kongresi, MSÜ, İstanbul, s.32-37.

[10] Özaydın (Kılıçreis), G., 1993. Kentsel Tasarım Kapsamında Tarihi Kentsel Mekanlarda Arayüzlerin

Düzenlenmesine Sistemli bir Yaklaşım, Yayınlanmamış Doktora Tezi, MSÜ-Fen Bilimleri Enstitüsü, İstan-bul, s.13-24.

[11] Erdönmez, M. E., ve Akı, A., 2005. Açık Kamusal Kent Mekanlarının Toplum İlişkilerindeki Etkileri,

Megaron, YTÜ Mim. Fak. E-Dergisi, Cilt 1, sayı.1, s.67-78.

[12] Konuk, G.,1989. Kamu Mekanları Tasarımında Cephe Düzeni, Kamu Mekanları Tasarımı ve Kent

Mobilyaları Sempozyumu, MSÜ, İstanbul, s.55-56.

[13] Özyürek, İ., 1995. The Interface of Architectural Built Form and Urban Outdoor Space, METU, M.S.

Thesis, Graduate School of Natural and Applied Sciences, Ankara.

[14] Yarar, L., 2003. Planlama Kademelenmesindeki İçerisinde Kentsel Tasarım Projelerinin Yeri, Kentsel

Yenileşme ve Kentsel Tasarım-Uluslar arası 14. Kentsel Tasarım ve Uygulamalar Sempozyumu, MSÜ, İstanbul, s.157-159.

[15] Kuban, D., 1990. Tarlabaşı Yarışması ve Tarlabaşı’nın Geleceği, Yapı Dergisi, No: 105, s.55-59. [16] Konuk, G., 1991. Zaman ve Mekanın Bir Sentezi Olarak Kentsel Tasarım, 1. Kentsel Tarım ve

Uygu-lamalar Sempozyumu, MSÜ, İstanbul, s.73-78.

[17] Rıfat Osman., 1994. Yayınlayan: Kazancıgil, R., Edirne Rehnüması (Edirne Şehir Klavuzu), Türk

Kütüphaneciler derneği Şubesi Yayınları, No:15, Edirne, s.15-27,152.

[18] Peremeci, O.N., 1939. Edirne Tarihi, Resimli Ay Matbaası, İstanbul, s.10-43.

[19] Sirel, A. ve Sirel, Ü., 2005. Tarihî Kentlerin Unutulan Arayüzü: Edirne-Kaleiçi’nde Saraçlar Caddesi

Örneği, Dünya Şehircilik Günü Kolokyumu, Bildiri kitabı, İTÜ, İstanbul, s.408.

[20] Abdurrahman Hıbri., 1996. Enisü’l Müsamirin (Edirne Tarihi), Çev: Ratip Kazancıgil, Türk

Kütüpha-neciler Derneği Edirne Şubesi Yayınları, No:24, Edirne, s.16.

[21] Akansel, S., Kaprol, T., Varlı, E., 2011. Edirne Tarihî Saraçlar Caddesi Yayalaştırma Projesinin

Kent-sel Yaşama Katkıları, Mimarlık Dergisi 2011, Sayı. 359, s.49-52. Image sources:

Figure 13: Ayşe Sirel (2014); other figures: Saraçlar Street Pedestranization Urban Design Project, Ümit Sirel (2003).

AYŞE SİREL; B. Arch, M.Sc., PhD.,

Received her B. Arch (1980) from Mimar Sinan University, Faculty of Architecture, and M.Sc. in City Planning from Yıldız Univercity (1982). She earned her Ph.D. degree in City and Regional Planning from Mimar Sinan University (1993), Istanbul, Turkey. Dr. Sirel worked as a Research Assistant at the City and Regional Planning Department (Mimar Sinan University/1983-1993) and as Assistant Professor in the Department of

Architec-Village House in Van

Hakan Irven, Bilge Işık

Institute of Science Master of Architecture

Istanbul Aydin University, Florya Istanbul /Turkey E-mail: hakanirven@gmail.com

Abstract: The decision of the building materials is very important the survival and for the healthy living. Information, material and energy were described in the 1970s as the three pillars of the modern civilization of the people. Nowadays, the materials seem to be more important day by day. Different materials are used in the buildings according to the region. One of these regions is Van where the structures in rural areas were built with materials obtained from the completely natural environment. In the recent period, as a result of the access of the industrial building materials to the region and the economic opportunities reaching the level of purchase, a change can be seen in the buildings. Within the scope of the study, the changes in the use of the building materials were examined in the village house of Van during the process. As a result of the study it can be seen that the condition related to the human health has not been provided and the organization providing plus for the living comfort has not been structured during the selection of the materials in the newly built houses.

Keywords: Housing, natural materials, materials, region, Van

Van Köy Evi Yapılarında Kullanılan Malzemeler

Özet: Yapı Malzemesi kararı, insanların hayatta kalma ve sağlıklı yaşamaları için önemlidir. Bilgi, malzeme ve enerji 1970'lerde insanların çağdaş uygarlığının üçayağı olarak nitelendirilmiştir. Günümüzde malzemenin her geçen gün daha önemli olduğu görülmektedir. Yöre özelliklerine göre yapılarda farklı malzemeler kullanılır. Bu bölgelerden biri olan Van yöresi, kırsal kesimlerinde yapılar tamamen doğal çevreden elde edilen malzemeler ile inşa edilmiştir. Endüstriyel yapı malzemelerinin bölgeye ulaşması, ekonomik imkânların satın alma düzeyine gelmesi sonucu yapılarda son dönemde bir değişim görülmektedir. Çalışma kapsamında Van köy evlerinde süreç içerisindeki yapı malzeme kullanımdaki değişim incelenmiştir. Yapılan çalışma sonucunda yeni yapılan konutlarda malzeme seçimi yapılırken insan sağlığı ile ilgili şartların sağlanamadığı, yaşam konforuna artı sağlayacak örgütlenmenin yapılamadığı görülmektedir.

1. INTRODUCTION

The city of Van located in the eastern part of Turkey is a favourable residential center where the Lake Van can be found which is Anatolia’s largest river basin with productive rivers on its shore, besides its cultural wealth which has been cradled by many civilizations for centuries. Therefore, it has been a place since the ancient times of the history which was dominated by many civilizations. According to the archaeological researches the periods of Van extend before the written history B.C. 5000-3000, until the beginning of Chalcolithic period. The Hurrions are the first in 2000 B.C. who established the first state in this region. Then the state of Urartu with its capitol Tusba was established in 900 B.C. by the indigenous tribes who had followed the Hurriler in the region [1]. The Urartus had ruled the region of Van and their land was extended up in the south until Mesopotamia. The construction materials ongoing from these civilizations are observed to be continued in various regions of the city Van. The main building materials of the period can be listed as brick, wood beams and cane.

Adobe houses could be found frequently in the province of Van up to 1980 and the ratio of apartment type concrete houses was very little. With the founding of building societies after the mid- 1980s a rapid construction begun in the city and this construction continued to develop until today. The rapid development of the city center caused the reduction of the green areas in the environment and their completely or partially disappearance. In this process, how the green areas and old houses with large gardens which were located in the oldest residential areas of the city and which had an important place in the identity of the city were not protected, the existing green spaces were getting smaller or were completely destroyed. Neither the amount of green spaces nor the distribution of the urban pattern is sufficient enough to meet the demand. The result of the fact that the adobe materials were located in the education and that the building materials produced in the industry dominated the market in the city in the 1980s accelerated the transformation to concrete structure. As a result of the incidental observations it can be defined that the transformation reflected in the villages 10-15 years later or after 1990. It can be mentioned that in the years after 1990 the structure planning, plan scheme and the variety of materials changed significantly in village houses. In this context, as the subject of the study it was aimed to make an analysis study as a result of the obtained data by making examination of the changes occurred in the process in the materials used for the village houses in Van, in the field studies and in the literature reviews.

2. THE MAIN MATERIALS USED IN THE STUCTURAL DESING OF THE VILLAGE HOUSES

The substances produced naturally or artificially with the aim of making available bodies are called materials. Materials are essential components forming almost everything that we use in our daily life. The materials which occurred naturally or were obtained artificially can be used in any thinkable type of industry like automotive, aerospace, chemical, electronics, food production, and biomedical sectors. The materials can be divided into four basic groups. These are mainly expressed as natural inorganic materials, organic and natural materials, ceramics, glass, plastics, semiconductors and metals [2]. At the beginning of the civilization up to this time the materials together with energy raised the living standard of the mankind. A number of materials which have been used without changing from the ancient times until the present days always maintained their importance. The main of these materials can be listed as stone, adobe and wood. Nowadays in addition to these materials, briquette, concrete, glass wool and paint are used in the village houses.

2.1. Stone

The natural stone which was formed for thousands of years in the nature has a high strength. So, the features of the material can remain the same [3]. The buildings made in the previous periods were

constructed on the basis of the material’s strength under the pressure. In the structure building process masonry structures were made by placing the stone on each other with a particular system. Both the existing conditions and the easy providing were effective in the choice. Nowadays the new technological conditions, the desire of high structured buildings together with the decrease of stone craftsmen reduced the commitment to this material. Today, stones are preferred mostly for decorative purposes.

Figure 1. Village of Bayramli / Van/ stone school building [Irven, H.] photographed by Hakan Irven Figure 2. Village of Hamurkesen/ Van / Adobe building

2.2. Adobe

Adobe; is a building material made by pouring the mixture of soil, straw and hay into moulds in the size and form of a brick (Figure 2). Adobe is a material used in every regions of our country. It is used less in the rural areas of Eastern Anatolia. Nowadays, with the increase of industrial building materials it can be said that the usage ratio of the adobe is reduced. Adobe which is a traditional material uses less energy at the stage of production and consumption. It came up again recently because it is an environmental friendly building material. Adobe which is a type of mud with a suitable consistency which was prepared by being mixed with straw in a pool and then it got the desired size by filling it into wood molds. In the structure, from the ground up to the window level, adobe which is sensitive to water gives its place to stone material. The adobe material is also known for creating an air conditioning effect in the building.

2.3. Wood

Wood used often as a material in every period, continues today to be a material by increasing its importance. In the past, in the structure of the village houses wooden beams were preferred due to passing the opening in the upper floor, making light roof (Figure 3) and easy manufacturing. Today, wood is used generally for decorative purposes.

constructed on the basis of the material’s strength under the pressure. In the structure building process masonry structures were made by placing the stone on each other with a particular system. Both the existing conditions and the easy providing were effective in the choice. Nowadays the new technological conditions, the desire of high structured buildings together with the decrease of stone craftsmen reduced the commitment to this material. Today, stones are preferred mostly for decorative purposes.

Figure 1. Village of Bayramli / Van/ stone school building [Irven, H.] photographed by Hakan Irven Figure 2. Village of Hamurkesen/ Van / Adobe building

2.2. Adobe

Adobe; is a building material made by pouring the mixture of soil, straw and hay into moulds in the size and form of a brick (Figure 2). Adobe is a material used in every regions of our country. It is used less in the rural areas of Eastern Anatolia. Nowadays, with the increase of industrial building materials it can be said that the usage ratio of the adobe is reduced. Adobe which is a traditional material uses less energy at the stage of production and consumption. It came up again recently because it is an environmental friendly building material. Adobe which is a type of mud with a suitable consistency which was prepared by being mixed with straw in a pool and then it got the desired size by filling it into wood molds. In the structure, from the ground up to the window level, adobe which is sensitive to water gives its place to stone material. The adobe material is also known for creating an air conditioning effect in the building.

2.3. Wood

Wood used often as a material in every period, continues today to be a material by increasing its importance. In the past, in the structure of the village houses wooden beams were preferred due to passing the opening in the upper floor, making light roof (Figure 3) and easy manufacturing. Today, wood is used generally for decorative purposes.

Figure 3. Village of Karahan / Van / Application of wooden roof [4]

Figure 4. Village of Bayramli /Van / stone foundation photographed by Hakan Irven 3. THE SPATIAL TRANSFORMATION OF THE CITY OF VAN

The city of Van which was founded on the banks of the Lake Van in the year of 855 BC; besides it historical, military and strategic importance, it has been the crossing point of significant civilizations from time to time.

Even in Assyrian sources, Van was determined as a place decorated with gardens and trees. At the end of the XIX th. century Van had the feature of spare textured settlement between the vineyards and gardens and the walled section defined as the “Lower City” created the business and commercial center of the city of Van. Here trading establishment, government offices, mosques were located. The second part of the city, the “Upper City” which was located above the walled section was famous for its gardens, beautiful fruits and rich wine production. These gardens were watered with tea and by the canals remained from the Urartu era. This part of the town was mostly devoted to residence. From entering the gardens and reaching the main street the settlement groups were selected. The private residence of the governor of Van and of other administrators and the houses of the rich Armenian merchants were located in this area. The American mission, the French Dominican mission, the consulates of Russia, Iran and England and the schools of some countries with the important churches of the Gregorian denomination, were located in the garden section. The presence of the schools and consulates of different countries such as American schools in the city, contributed significantly to the progress of urbanizations as well as in socio-cultural aspects. The Armenian revolts between the years of 1895 and 1917 due to the Russian invasion in 1917 a significant part of the segment which held the city’s vibrancy and culture in the hand either emigrated or died in the war. This situation revealed quite grave consequences on the city’s cultural heritage and lifestyle [1]. The loss of cultural accumulation which is necessary for the development, the ceaseless wars, the prohibits for the trade life brought by the new political boundaries, the weak economy of the city dwellers which was based on agriculture and hand craft led the city to remain self-enclosed for a long time, to get weakened and to become a province that gave many migrates to the big cities.

During the Republic period, in certain regions of Anatolia it was seen that together with the industrialization, the urbanization begun also. This effect of modernism was not seen everywhere in Anatolia at the same time. In the province of Van the urbanization in modern sense has entered into a rapid period for the last 20 years due to various socio-economic reasons. Due to the disasters in the last 20 years the migration towards the city has accelerated and the development in the city turned to unplanned constructions and squatters. While on one side of the town observing modern city-specific structures and forms of life, on the other side even in the most developed villages of the region miseries can be seen.

During this process the structural elements of the individuals ‘buildings who were living in the village and which were still bearing the trace of the past were maintained to build in a totally unconscious way without putting them into certain discipline. This planning and these materials were continued to be used until the 1990s. After the years of the 1990s, a new process started in the construction by getting diversity in the materials, planning and structure. In this process, as material they used brick instead of adobe in the walls, concrete plaster instead of mud, steel coating in the roof and materials similar to glass wool for heat isolation. In the planning of structure carcass or mixed system was used instead of masonry structure. In accordance with this data the structure of the village houses can be taken into two periods.

4. THE CONSTRUCTON MATERIALS USED IN VILLAGE HOUSES BEFORE 1990

These are the buildings which were easily made by taking the available natural materials as reference in the course of time during the years of reign of the adverse conditions of the economy’s weakness and the absence of shelter indexed aesthetic worry. These buildings were made without foreseeing a specific planning system. The m² size of the building varied depending on the number of family.

4.1. The materials used in the construction of the basis

The richness of the region in stones and rocks was the main reason for the use of natural stones. Stones are placed until a certain socle elevation. Soil is put on the top of the stones as heating isolation. The surfaces are often plastered with mud (Figure 4).

4.2. Exterior walls

Adobe prepared in a specific pattern was put to the surface in an obfuscatory way and was obtained by coating the surfaces with mud plaster. Stone walls were also made by putting the stones to the outside surface of the adobe. The stone surfaces in a certain thickness can provide cool in the summer and warm in the winter by making air-conditioning effect for the house. At the same time it kept the house standing in a solid structure for many years until today. For many centuries stones were used in the structure as an important building material. Nowadays, it is preferred as building elements more for decorative purposes [5].

4.3. Upper Floor

The poplar trees which are preferred in the region due to their cultivation and rapid growth were used as roof beams on many of the upper floors, then nylon canvas was laid down on the top of the roof beams (Figure 5). Then soil was put on the top of the nylon and so the flat roof was constructed. Sometimes cane found in the region was used as a cover at the top (Figure 6).

Figure 5. The construction of adobe wall

During this process the structural elements of the individuals ‘buildings who were living in the village and which were still bearing the trace of the past were maintained to build in a totally unconscious way without putting them into certain discipline. This planning and these materials were continued to be used until the 1990s. After the years of the 1990s, a new process started in the construction by getting diversity in the materials, planning and structure. In this process, as material they used brick instead of adobe in the walls, concrete plaster instead of mud, steel coating in the roof and materials similar to glass wool for heat isolation. In the planning of structure carcass or mixed system was used instead of masonry structure. In accordance with this data the structure of the village houses can be taken into two periods.

4. THE CONSTRUCTON MATERIALS USED IN VILLAGE HOUSES BEFORE 1990

These are the buildings which were easily made by taking the available natural materials as reference in the course of time during the years of reign of the adverse conditions of the economy’s weakness and the absence of shelter indexed aesthetic worry. These buildings were made without foreseeing a specific planning system. The m² size of the building varied depending on the number of family.

4.1. The materials used in the construction of the basis

The richness of the region in stones and rocks was the main reason for the use of natural stones. Stones are placed until a certain socle elevation. Soil is put on the top of the stones as heating isolation. The surfaces are often plastered with mud (Figure 4).

4.2. Exterior walls

Adobe prepared in a specific pattern was put to the surface in an obfuscatory way and was obtained by coating the surfaces with mud plaster. Stone walls were also made by putting the stones to the outside surface of the adobe. The stone surfaces in a certain thickness can provide cool in the summer and warm in the winter by making air-conditioning effect for the house. At the same time it kept the house standing in a solid structure for many years until today. For many centuries stones were used in the structure as an important building material. Nowadays, it is preferred as building elements more for decorative purposes [5].

4.3. Upper Floor

The poplar trees which are preferred in the region due to their cultivation and rapid growth were used as roof beams on many of the upper floors, then nylon canvas was laid down on the top of the roof beams (Figure 5). Then soil was put on the top of the nylon and so the flat roof was constructed. Sometimes cane found in the region was used as a cover at the top (Figure 6).

Figure 5. The construction of adobe wall

Basic: The foundation structures with the use of stone is very important for the strength between the ground and the building (Figure 7, 8)

External surface: was made by using stone and adobe. The surfaces were plastered with mud material (Figure 7, 8)

Upper floor: wooden beams (poplar tree) and cane are frequently used (Figure 7, 8)

In Figure 7, we can see examples from the village of Bayramli for buildings made from adobe before 1990. It was used until the earthquake occurred in 2011, after the earthquake it was abandoned. The building in Figure 8 is an example for adobe structure in the rural area of Van before 1990.

The use of the materials mentioned above in the village houses seen to be the reason for some factors. After the conducted field observation the reasons that lead for the use of materials can be listed as the following.

5. THE CAUSES REFERRING THE MATERIALS USED IN THE VILLAGE HOUSES BEFORE 1990

The main reasons that lead for the use of materials can be listed as follows economic reasons, transportation, available materials within the near environment, the absent of the technical infrastructure and the cause of education [6].

Figure 7. Village of Bayramli / Van/ structure from before 1990 photographed by Hakan Irven Figure 8. Village of Ocakli / Van / structure from before 1990

5.1. The industry of traditional building technology

The individuals who have experience in the traditional building technologies do not have enough knowledge to use different materials in the structures. The situation restricts their entry to seek for something different.

5.2. The available materials which can be found in the near environment

6. THE MATERIALS USED IN THE BUILDING OF THE VILLAGE HOUSES IN VAN AFTER 1990

Together with the rapid transformation of the city the broken connection of the villages with the city began to close. The individuals living in the villages observing the development of the city have entered into various seeks. At the same time together with the multiplication of the individuals who were educated of the transportation, infrastructure and workforce development, a noticeable transformation-change was observed in the houses of the village. During this period, in addition to the structure made before 1990 as a result of the fact that the materials arrived to the region and the economic opportunity reached the level of purchase, they started to use briquette and concrete plaster for the external walls, glass wool for the heat isolation of the upper floor, and sheet metal cover for the upper cover. In the course of time, together with the transformation of the material change, different solutions started in the spatial planning. Worry can be seen about the different colours of the external walls on the building’s surfaces. In this context, in some of the buildings identity changes can be observed that occurred in the buildings of the village. Without the uniform planning of the building surfaces, besides the effort to create a number of moving surfaces, worries about the different colour of the exterior paint are seen on the surfaces (Figure 9, 10)

Figure 9. Village of Bayramli /Van photographed by Hakan Irven

Figure 10. Village of Bayramli /Van / Briquettes of the external wall photographed by Hakan Irven After 1990 in the building of Figure 11, 12 as it is seen, briquettes were used instead of adobe, the surfaces were plastered with concrete and were painted with whitewash. The window is divided into several panes instead of using one eye window. This also shows that various aesthetic seeks entered in the buildings. It is often observed that they used sheet metal cover for the upper floor coverings. In the area where heavy snowfall occurs together with the easier commute of the materials to the village, this transformation has become an active cause in the choice.

Figure 11. Village of Bayramli / Van/ Application of briquette structure photographed by Hakan Irven Figure 12. Village of Bayramli / Van / Application of masonry structure photographed by Hakan Irven

Figure 13. Village of Bayramli / Van/ building in the last period photographed by Hakan Irven The activities of change-transformation occurred in the village houses after the 1990s have gained speed. In the following years, the heat isolation and planning principles in the buildings have been adopted by the individuals. In this context, change and transformation can be observed within the framework of the emerging opportunities during this course of time in the rural area of the city of Van. This transformation in the countryside was not made by a plan and program; this should be done completely according to the basis of the individuals’ own formats and planning (Figure 13).

7. CONCLUSION

As the result of the studies made recently, the rural area of the city of Van emerges as two different periods. The first of these periods is before 1990 when the rural areas were observed to proceed by adopting the principles of planning for shelter in completely natural conditions. The individuals made the local places like house, barn with main materials such as stone, adobe, woods which could be found in natural conditions. At the development part of the location, some reasons which were mentioned before stood against them as forcing power to use these materials. The emerging opportunities and advantages after the 1990s helped the individuals to use new materials in the buildings. But unfortunately, this development did not go further than bringing the buildings one step forward only visually. During the

Figure 11. Village of Bayramli / Van/ Application of briquette structure photographed by Hakan Irven Figure 12. Village of Bayramli / Van / Application of masonry structure photographed by Hakan Irven

Figure 13. Village of Bayramli / Van/ building in the last period photographed by Hakan Irven The activities of change-transformation occurred in the village houses after the 1990s have gained speed. In the following years, the heat isolation and planning principles in the buildings have been adopted by the individuals. In this context, change and transformation can be observed within the framework of the emerging opportunities during this course of time in the rural area of the city of Van. This transformation in the countryside was not made by a plan and program; this should be done completely according to the basis of the individuals’ own formats and planning (Figure 13).

7. CONCLUSION

As the result of the studies made recently, the rural area of the city of Van emerges as two different periods. The first of these periods is before 1990 when the rural areas were observed to proceed by adopting the principles of planning for shelter in completely natural conditions. The individuals made the local places like house, barn with main materials such as stone, adobe, woods which could be found in natural conditions. At the development part of the location, some reasons which were mentioned before stood against them as forcing power to use these materials. The emerging opportunities and advantages after the 1990s helped the individuals to use new materials in the buildings. But unfortunately, this development did not go further than bringing the buildings one step forward only visually. During the

selection of material for the houses, a number of contrasts were continued and it is seen that the organizations that provide a plus in the living comfort have not been achieved. To give an example, while providing the heat isolation by the glass wool which is used recently under the roof cover as isolation briquettes are used on the surface of the walls which is very weak in terms of isolation. This case shows that the structures obtained are too weak in technical way. As a result, support should be given by the relevant institutions by delegating a team of experts in the context of rural development planning.

REFERENCES

[1] Taha Orhan, 2012. Planning Construction Engineer, Anonym company Analysis Reports of the Cities.

[2] Seden, A., Gürdal, E., 2003. Yenilenebilir Bir Malzeme: Kerpiç ve Alçılı Kerpiç, Istanbul.

[3] Siegesmund, S., Snethlage, R., 2014. Stone in Architecture: Properties, Durability. Springer; 5 edition.

[4] Schachner, A., 2010. Boğazköy-Hattuşaş Kazı ve Restorasyon çalışmaları, 33.3 KST (Ankara 2012) [5] Öztürk, S., 2013. Mud brick Bat and Natural Mud brick in the Production Techniques in Van, kerpic’13 – New Generation Earthern Architecture: Learning from Heritage International Conference Istanbul Aydın University, Turkey, 11-15 September 2013, 221-223.

[6] Sirel, A., 2013. An Urban Fabric mainly Based on Adobe: The old city of Van Kerpic, kerpic’13 – New Generation Earthern Architecture: Learning from Heritage International Conference Istanbul Aydın University, Turkey, 11-15 September 2013, 315-319.

[7] Işık B., Helvacı G., 1999. "Role of Culture and Tradition in the Development of Housing in the GAP Area of Turkey" IAHS World Congress on Housing "Housing Issues and Challenges for the New Millennium" San Francisco, USA, June 1-7

HAKAN IRVEN, Arch.

Graduated from Erciyes University at 2011; M.Arch at Istanbul Aydin University Institute of Natural and Applied Sciences (2014- ). Owner of architectural design office in Van; made public and private project designs, have done work in architectural design and architectural consultancy services in the Province of Van.

Armin Saei Leylonahar

Institute of Science Master of Architecture

Istanbul Aydin University, Florya Istanbul /Turkey E-mail: saei.armin@gmail.com

Abstract: By transition of societies and passing pre-historical era, roads are developed and completed consistent with improvement and efficiency of other social institutes. Meanwhile some people explore east and west looking for new ways for better living and gained common achievements which became the base of peaceful relationship between human beings and human with nature over the centuries. These led to appearance of long and important roads. It became so plain that famous roads such as Silk Road created. The Silk Road, or Silk Route, is a network of trade and cultural transmission routes that were central to cultural interaction through regions of the Asian continent connecting the West and East by merchants, pilgrims, monks, soldiers, nomads, and urban dwellers from China and India to the Mediterranean Sea

.

Silk Road were mainly economical and were related to agricultural, industrial, handicrafts and mining merchandises. Furthermore, dealings of different nations didn’t confine just to this specific domain, but cultural, social and political exchanges were also consequences of traveling in this long and continuous road which should not be overlooked.

Keyword: Silk Road, business, tourism, economy, culture, custom

Gümrük ve Gümrüğün Turizmdeki Yeri

Özet: Toplumların dönüşümü ve tarih öncesinden günümüze geçerken, yollar gelişim ve diğer sosyal enstitülerin yeterliliği ile gelişmiş ve süreçlerini tamamlanmışlardır. Bu arada bazı insanlar doğu ve batıda daha iyi yaşama olanaklarını araştırdılar ve bunun ardından yüzyıllardır süregelen insan varlığı ve insanın doğa ile ilişkisi arasında barışcılbir ilişki temeli kurdular. Bunlar uzun ve önemli yolların ortaya çıkışını sağlamıştır. Bunun sonucunda doğal olarakdan Ipek Yolu gibi ünlü yollar ortaya çıkmıştır. İpek yolu veya İpek rotası kültürel alışverişin ve ticaretin ağını oluşturdu. Ipek yolu tüccarlar, göçmenler, din adamları, askerler, göçebeler ve şehir sakinleri vasıtasıyla Batı’da Akdenizden ve Doğu’ da Çin’e kadar Asya kıtası bölgeleri boyunca kültürel etkileşimlerin merkezi oldu. İpek Yolu’nda ziraat, endüstri, el sanatları, madencilikle ilgili ana değişiklikler meydana geldi. Farklı milletler arası ilişkiler bu belirli alanlarda kalmadı. Bu uzun ve sürekli yol boyunca yapılan seyahatlerin kültürel, sosyal ve politik alanlardaki alışverişlerle sonuçlandığı gözardı edilmemelidir.

Armin Saei Leylonahar

Institute of Science Master of Architecture

Istanbul Aydin University, Florya Istanbul /Turkey E-mail: saei.armin@gmail.com

Abstract: By transition of societies and passing pre-historical era, roads are developed and completed consistent with improvement and efficiency of other social institutes. Meanwhile some people explore east and west looking for new ways for better living and gained common achievements which became the base of peaceful relationship between human beings and human with nature over the centuries. These led to appearance of long and important roads. It became so plain that famous roads such as Silk Road created. The Silk Road, or Silk Route, is a network of trade and cultural transmission routes that were central to cultural interaction through regions of the Asian continent connecting the West and East by merchants, pilgrims, monks, soldiers, nomads, and urban dwellers from China and India to the Mediterranean Sea

.

Silk Road were mainly economical and were related to agricultural, industrial, handicrafts and mining merchandises. Furthermore, dealings of different nations didn’t confine just to this specific domain, but cultural, social and political exchanges were also consequences of traveling in this long and continuous road which should not be overlooked.

Keyword: Silk Road, business, tourism, economy, culture, custom

Gümrük ve Gümrüğün Turizmdeki Yeri

Özet: Toplumların dönüşümü ve tarih öncesinden günümüze geçerken, yollar gelişim ve diğer sosyal enstitülerin yeterliliği ile gelişmiş ve süreçlerini tamamlanmışlardır. Bu arada bazı insanlar doğu ve batıda daha iyi yaşama olanaklarını araştırdılar ve bunun ardından yüzyıllardır süregelen insan varlığı ve insanın doğa ile ilişkisi arasında barışcılbir ilişki temeli kurdular. Bunlar uzun ve önemli yolların ortaya çıkışını sağlamıştır. Bunun sonucunda doğal olarakdan Ipek Yolu gibi ünlü yollar ortaya çıkmıştır. İpek yolu veya İpek rotası kültürel alışverişin ve ticaretin ağını oluşturdu. Ipek yolu tüccarlar, göçmenler, din adamları, askerler, göçebeler ve şehir sakinleri vasıtasıyla Batı’da Akdenizden ve Doğu’ da Çin’e kadar Asya kıtası bölgeleri boyunca kültürel etkileşimlerin merkezi oldu. İpek Yolu’nda ziraat, endüstri, el sanatları, madencilikle ilgili ana değişiklikler meydana geldi. Farklı milletler arası ilişkiler bu belirli alanlarda kalmadı. Bu uzun ve sürekli yol boyunca yapılan seyahatlerin kültürel, sosyal ve politik alanlardaki alışverişlerle sonuçlandığı gözardı edilmemelidir.

![Figure 1. Village of Bayramli / Van/ stone school building [Irven, H.] photographed by Hakan Irven Figure 2](https://thumb-eu.123doks.com/thumbv2/9libnet/4179653.64549/24.918.146.801.254.511/figure-village-bayramli-school-building-irven-photographed-figure.webp)

![Figure 3. Village of Karahan / Van / Application of wooden roof [4]](https://thumb-eu.123doks.com/thumbv2/9libnet/4179653.64549/25.918.169.732.140.351/figure-village-karahan-application-wooden-roof.webp)