O R I G I N A L R E S E A R C H P A P E R

The effect of a transtheoretical model

–based motivational

interview on self

‐efficacy, metabolic control, and health

behaviour in adults with type 2 diabetes mellitus: A randomized

controlled trial

Alime Selçuk

‐Tosun RN, PhD, Lecturer

1|

Handan Zincir RN, PhD, Associate Professor

21

Faculty of Nursing, Selçuk University, Konya, Turkey

2

Faculty of Health Sciences, Erciyes University, Kayseri, Turkey Correspondence

Alime Selçuk‐Tosun, Faculty of Nursing, Selçuk University, Alaaddin Keykubat Campus, Konya, 42250 Selçuklu, Turkey.

Email: alimeselcuk_32@hotmail.com Funding information

Scientific Research Project Coordination Department at Erciyes University, Grant/ Award Number: TDK‐2013‐4699

Abstract

Aim:

This study aimed to determine the effect of a transtheoretical model

–based

motivational interview method on self

‐efficacy, metabolic control, and health

behav-iour in adults with type 2 diabetes mellitus.

Methods:

A randomized controlled study design was used. The study was

con-ducted with 50 individuals with type 2 diabetes mellitus, divided into an intervention

group and a control group. The researcher held motivational interviews with the

patients in the intervention group. Both groups were observed at the beginning of

the study and 6 months after the baseline interview. The study data were collected

between January 8 and November 18, 2014.

Results:

Comparing the intervention and the control groups, the differences in the

level of self

‐efficacy and participants' metabolic values were significant (P < .05). The

number of participants in the action stage of the intervention group for nutrition,

exercise, and medication use significantly increased compared with the control group

(P < .05).

Conclusion:

The transtheoretical model

–based motivational interview method

increased the self

‐efficacy level of participants with type 2 diabetes mellitus, which

helped them improve their metabolic control and health behaviour stages over this

6

‐month period.

K E Y W O R D S

metabolic control, motivational interview, nursing, self‐efficacy, type 2 diabetes mellitus

S U M M A R Y S T A T E M E N T

What is already known about this topic?

• Type 2 diabetes mellitus is one of the top 10 potentially fatal dis-eases that are increasing in prevalence worldwide.

• The level of self‐efficacy is directly associated with health‐ promotion behaviours such as proper diet and regular exercise. The self‐belief or self‐efficacy level for a behaviour can increase or decrease the motivation for taking action.

• The transtheoretical model facilitates the classification of stages a person goes through before engaging in a behaviour.

This study was an oral presentation at the International Institute of Social and Economic Sciences 20th International Academic Conference. Selçuk‐Tosun A., Zincir H., The Effect of a Transtheoretic Model‐based Motivational Interview on Self‐Efficacy, Metabolic Control and Health Behavior in Individuals with Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus, IISES 20th International Academic Con-ference, Madrid Oral Presentation, October 6‐9, 2015, Madrid, Spain. pp. 92‐93.

DOI: 10.1111/ijn.12742

Int J Nurs Pract. 2019;25:e12742. https://doi.org/10.1111/ijn.12742

© 2019 John Wiley & Sons Australia, Ltd

What this paper adds?

• The transtheoretical model–based motivational interview helps people with type 2 diabetes mellitus control their blood glucose levels; increase their level of self‐efficacy, which is important for behavioural change; and make positive improvements in nutrition, exercise, and medication use.

• The frequency of conducting transtheoretical model–based motiva-tional interviews should be planned according to the characteristics of individuals.

The implications of this paper:

• The transtheoretical model–based motivational interview method for encouraging positive health behavioural change (nutrition, exer-cise, and medication use) in adults with type 2 diabetes mellitus who resist behavioural change may be beneficial in promoting behavioural change.

• Health care providers can easily apply the transtheoretical model– based motivational interview method.

1

|I N T R O D U C T I O N

The prevalence of type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM) has been growing in most parts of the world in recent years. The increasing prevalence of T2DM and the complications caused by its effect on individuals' lifespan have very high costs. In disease management, the main prior-ity of individuals and health professionals is to prevent acute compli-cations and reduce the risk of chronic complicompli-cations (ADA, 2017; WHO, 2010). For example, early diagnosis and treatment reduces complications in individuals with T2DM (ICN, 2010). With the purpose of achieving these goals, patients are asked to maintain a sufficient and balanced diet, do regular physical exercise, monitor their blood glucose regularly, and administer their medication and insulin, if neces-sary, at the right time and dose (ADA, 2017).

Many studies have been conducted recently on healthy lifestyles. The most commonly used health behaviour model is the transtheoretical model (TTM) (Dray & Wade, 2012; Glanz, Rimer, & Viswanath, 2008; Kirk, Mutrie, Macintyre, & Fisher, 2003; Pichayapinyo, Lagampan, & Rueangsiriwat, 2015). TTM enables people to use the targets and approaches of the behavioural change stage rather than all or nothing; it deals dynamically with behavioural change (Marshall & Biddle, 2001).

According to the TTM developed by Prochaska and DiClemente (1982), people engage in behaviours by going through the stages of precontemplation, contemplation, preparation, action, and mainte-nance (Shinitzky & Kub, 2001). Only the stages of change were assessed in this study. The model structure also involves the concept of self‐efficacy (Prochaska & Velicer, 1997). For our purposes, self‐ efficacy is the belief that an individual can display positive health behaviours. A person's self‐efficacy level directly affects their health‐ promotion behaviours (Stuifbergen, Seraphine, & Roberts, 2000). Thus, as one of the four general principles of the motivational inter-view, supporting self‐efficacy helps people change their behaviours

(Miller & Rollnick, 2009; Stuifbergen et al, 2000). A past study reported that motivational interviews improved self‐efficacy. The studies conducted with individuals that had T2DM also demonstrated that self‐efficacy has a positive effect on health behaviours (Gao et al, 2013; Walker, Smalls, Hernandez‐Tejada, Campbell, & Egede, 2014).

The motivational interview is an evidence‐based counselling method used by health care professionals to help people adopt the targeted treatment recommendations (Chen, Creedy, Lin, & Wollin, 2012; Dellasega, Gabbay, Durdock, & Martinez‐King, 2010; Jones et al, 2003; Welch, Zagarins, Feinberg, & Garb, 2011; West, Dilillo, Bursac, Gore, & Greene, 2007). Studies on conducting motivational interviews with patients with T2DM have shown that these interviews improve HbA1C, weight loss, control of diet, and physical activity (Chapman et al, 2015; Chen et al, 2012; Heinrich, Candel, Schaper, & de Veries, 2010; Miller et al, 2014; Poursharif et al, 2010). On the other hand, another study reported that motivational interviews had no superiority compared with regular care (Rosenbek Minet, Wagner, Lonving, Hjelmborg, & Henriksen, 2011).

TheTTM plays an integrative role in interventions utilizing a motiva-tional approach. The TTM‐based motivational interview is an appropri-ate approach (Van Nes & Sawatzky, 2010) for nurses, who play an important role in the protection and development of health in patients with T2DM (ICN, 2010; Shinitzky & Kub, 2001). It is reported in litera-ture that the TTM‐based motivational interview focuses more intensely on the behavioural components of changes than do other educational approaches (Jones et al, 2014). In planning a TTM‐based motivational interview, customizing its duration and frequency can increase effec-tiveness in managing T2DM (Jones et al, 2014; Minet, Moller, Vach, Wagner, & Henriksen, 2010). In Turkey, no studies involve TTM‐based motivational interviews for individuals with T2DM. Thus, this study will act as a guide for nurses that work in protecting and treating health ser-vices. These nurses will be able to help T2DM patients by increasing their knowledge and experience in the TTM‐based motivational inter-view technique using in‐service training programmes. This study aimed to determine the effect of a TTM‐based motivational interview on the self‐efficacy, metabolic control, and health behaviour changes in adults with T2DM.

1.1

|Hypotheses of the study

H1. The self‐efficacy scores of participants in the intervention and control groups will differ statistically at follow‐up.

H2. The metabolic scores (weight, body mass index [BMI], waist circumference, preprandial and postpran-dial blood glucose levels, and HbA1c level) of partici-pants in the intervention and control groups will differ statistically at follow‐up.

H3. The exercise behaviour change stages of partici-pants in the intervention and control groups will differ statistically at follow‐up.

H4. The nutrition behaviour change stages of partici-pants in the intervention and control groups will differ statistically at follow‐up.

H5. The medication use behaviour change stages of participants in the intervention and control groups will differ statistically at follow‐up.

2

|M E T H O D S

2.1

|Study design

This study was planned as a randomized controlled study with the aim of assessing the effectiveness of a TTM‐based motivational interview technique. This study was conducted by the researcher in the endocri-nology and metabolism polyclinic of a university hospital with study data collected between January 8 and November 18, 2014.

2.2

|Sample size

The study group consisted of people who met the study's inclusion criteria. On the basis of the total self‐efficacy mean score of the

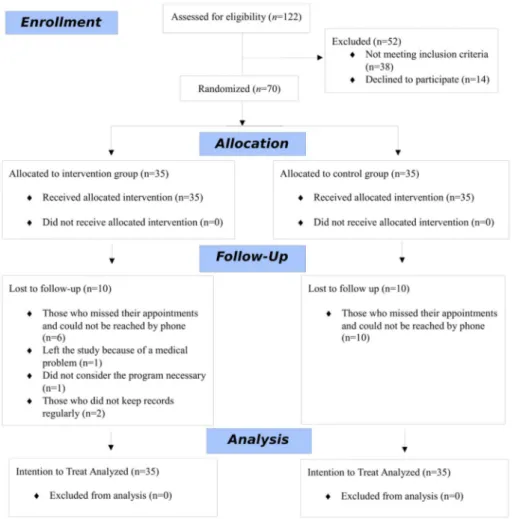

pre–follow‐up in a study conducted by Kartal and Özsoy (2014), the sample group size was determined to be 70, with an impact size of 0.34, 90% power, and a 5% margin of error. The individuals in the study sample were assigned to groups by an independent statistician in the computer environment. Computer program randomization placed 35 participants in the intervention group and 35 participants in the control group. In the present study, nine interviews and two interviews were conducted on average with the intervention and con-trol groups, respectively. In addition, the researcher was both the practitioner and responsible for the assessment. Therefore, the criteria for blinding could not be met. During the course of the study, 10 par-ticipants from the intervention group and 10 parpar-ticipants from the control group left or were excluded, and the study was completed with 50 participants (Figure 1).

2.3

|Study participants

The inclusion criteria for this study were that participants had T2DM and hypertension or dyslipidemia; were aged between 20 and 65 years; were primary school graduates; had a BMI of 25 kg/m2or more (overweight or obese); had a glycated haemoglobin (HbA1c) level of 7% or more; had been diagnosed with T2DM for 6 months or

longer; and were using oral diabetic medication, insulin, or both. The exclusion criteria were having medical problems that hindered exercise; having serious peripheral or autonomic neuropathy; having severe retinopathy; and having a psychiatric disorder. The termination criteria were being unwilling to continue participating in the study; developing other diabetic complications that hindered continued par-ticipation in the study; and not keeping records on a regular basis.

2.4

|Study instruments, primary and secondary

outcome measures

The researcher created the personal information form. The form has five questions about gender, age, education level, and the duration of T2DM.

The primary outcome was the self‐efficacy mean score measured at baseline and the sixth‐month follow‐up. This outcome was assessed with the Self‐efficacy (Competence) Scale for Patients with Type 2 Diabetes, the validity and reliability of which has been assessed (Kara, van der Bijl, Shortridge‐Bagget, Astı, & Erguney, 2006; Van der Bijl, Van Poelgeest‐Eeltink, & Shortridge‐Baggett, 1999).

The cross‐cultural adaptation of the scale was conducted by Kara et al (2006) in Erzurum, Turkey; the Cronbach alpha value of the scale was .89, test‐retest reliability was 0.91, and its construct valid-ity was 0.80.

The secondary outcomes were metabolic values (weight, BMI, waist circumference, preprandial and postprandial blood glucose levels, and HbA1c level); the number of steps taken; and the health behaviour change stage measured at baseline and the sixth‐month follow‐up.

2.4.1

|Height was measured in order to calculate

BMI

Height of individuals was measured as the length from the top of the head to the soles when they had their feet bare and adjacent and were standing in a Frankfort plane (back of the skull, shoulders, pelvis, and heels touching the same horizontal plane and the individual standing at attention) (Pekcan, 2011).

2.4.2

|Weight

The weights of the individuals were measured by the researcher using an electronic scale, and it was ensured that the individuals were bare-foot and wearing light clothes (Pekcan, 2011). The weights of the indi-viduals were measured using a TESS electronic scale that had a capacity of weighing a maximum 200 kg and a minimum sensitivity of 50 g.

2.4.3

|Body mass index

The researcher calculated the BMI values of all individuals using their height and weight measurement [(weight (kg)/height2 (m2)] (Saglik Bakanligi, 2011; Pekcan, 2011).

2.4.4

|Waist circumference

The researcher measured the waist circumferences of the individuals over their underwear after a mild expiration between the edge of the lower costal margin and iliac crest using a tape measure while the individuals were standing (Pekcan, 2011). A 1.5‐m‐long tape mea-sure was used to meamea-sure the waist circumference of the individuals. The measurement of waist circumference is also used individually and may be descriptive for the risk of chronic diseases (Saglik Bakanligi, 2011; Pekcan, 2011).

2.4.5

|Preprandial and postprandial blood glucose

levels and HbA1c level

Preprandial blood glucose is the glucose level of blood that is mea-sured after at least an 8 hours fast at night. Postprandial blood glucose is the value of blood glucose measured 2 hours after a meal. The HbA1c level shows the mean glycaemic value over the last 3 months (Saglik Bakanligi, 2011; International Diabetes Federation, 2012). Pre-prandial and postPre-prandial blood glucose levels and HbA1c level were evaluated following a venous blood draw in the hospital biochemistry laboratory. These values were requested by the physician when the individuals went to physician consultations were taken from the patient file and recorded by the researcher. The researcher also gave glucose metres to individuals in the experimental group to enable them to monitor their blood sugar levels at home.

2.4.6

|Activity levels

Participants in the intervention group received pedometers (Omron HJ‐321‐E) to monitor their daily activities. The individuals were asked to record on a tracking chart the dates they walked, the times of starting and finishing the walk, and the number of steps taken, with the purpose of ensuring that they regularly followed the exercise pro-gramme. The numbers of steps in the first‐ and sixth‐month assess-ments were calculated as the 30‐day means of step number in their records.

The pedometers were used as a motivational tool to increase walking (Baker, Mutrie, & Lowry, 2008).

2.4.7

|The stage of change in health behaviour

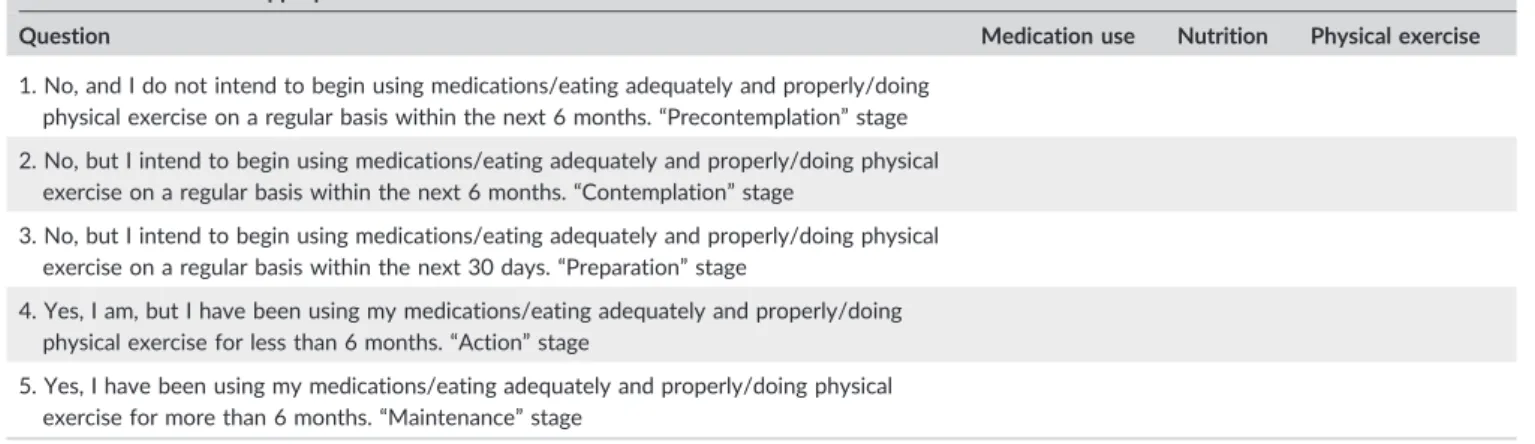

This was assessed using the Diagnosis Form for Behavioral Change Stage in Patients with Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus, which was prepared by the researcher based on information in the literature (Burbank, Reibe, Padula, & Nigg, 2002; Gillespie & Lenz, 2011; Prochaska, DiClemente, & Norcross, 1992; Salehi, Mohammad, & Montazeri, 2011; Shinitzky & Kub, 2001; Velicer et al, 2000) and on the TTM. The researcher consulted six experts (four public health nursing experts, one internal diseases nursing expert, and one statistics expert). The form consisted of three sections: physical exercise, nutri-tion, and medication use (Table 1). It included five multiple‐choice questions presenting the change stages through which a participantcould pass. This form was used in both the intervention and control groups to determine the participants' change stage regarding their physical exercise, nutrition, and medication use. The assessment was based on self‐reporting.

The researcher performed measurements of primary and second-ary outcomes (except preprandial and postprandial blood glucose levels and HbA1c level) using a face‐to‐face interview technique with the participants in a private room in the endocrine and metabolism outpatient clinic designated for the study.

2.5

|Interventions

2.5.1

|Intervention group

TTM‐based motivational interview guide

The TTM‐based motivational interview method for this study was developed by the researcher using motivational interview strategies consistent with the TTM's targets and approaches to behaviour stages, with the aim of producing a guide for patients with T2DM and health professionals. The physical exercise, adequate and proper nutrition, and medication use targeted for behavioural change were considered according to the change stages of the model. The literature was used while setting targets and approaches with regard to each change stage (Burbank et al, 2002; Gillespie & Lenz, 2011; Koyun & Eroglu, 2013; Miller & Rollnick, 2009; Prochaska et al, 1992; Prochaska & Velicer, 1997; Salehi et al, 2011; Shinitzky & Kub, 2001; Velicer et al, 2000; Yildiz, 2008). An interview protocol was prepared to ensure consis-tency among the participants in the intervention group during interviews.

The researcher (specialized in public health nursing) took a two‐ stage motivational interview technique course, each stage taking 9 hours. The researcher collected the data at the beginning and imme-diately after completion of the intervention (in the sixth month after the baseline interview) and held personal motivational interviews.

Participants were interviewed in a randomized order. At the begin-ning of the study, the participants filled out the personal information,

Self‐efficacy (Competence) Scale for Patients with Type 2 Diabetes, the Diagnosis Form for Behavioral Change Stage in Patients with Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus, and the Metabolic Control Follow‐up Form. The researcher also set the dates for the next interview.

TTM‐based motivational interview procedures

The researcher printed out TTM‐based motivational interview guides for each individual. TTM‐based motivational interviews were per-formed to assess targets and approaches to the nutrition, exercise, and medication use behaviour stages of the participants in the inter-vention group according to the Diagnosis Form for Behavioral Change Stage in Patients with Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus. Motiva-tional interview methods such as expressing empathy, developing discrepancy, rolling with resistance, supporting self‐efficacy, avoiding giving advice, providing simple decisional balance, using an importance‐confidence scale, using open‐ended questions, reflecting, and summarizing were used. Participants were given a medication use follow‐up table, a walking follow‐up table, and a food consump-tion registraconsump-tion form to fill out monthly. They were asked to bring their monthly follow‐up tables with them to the motivational inter-views. During the motivational interviews, these forms were used to help the individuals see the positive or negative changes in their behaviours related to their nutrition, exercise, and medication use and to encourage them make positive changes in themselves. In addition, any individual adaptations following the motivational inter-views were evaluated at the end of the sixth‐month period consider-ing self‐efficacy, metabolic values, number of steps, and behaviour change stage of nutrition, exercise, and medication use. The nutri-tion, exercise, and medication use guide for T2DM, prepared based on expert opinions, was given to the participants in the intervention group after the first TTM‐based motivational interview. Interviews were conducted every 15 days or monthly, at the participants' con-venience. Each interview was scheduled to take 30 to 45 minutes. These interviews ended in the sixth month after the baseline inter-view of the individual, and 9.12 (1.20) (mean [SD]) interinter-views were conducted with each participant.

TABLE 1 Diagnosis Form for Behavioral Change Stage in Patients with Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus

Medication use: Are you taking your medications regularly (at the same every day)?

Nutrition: Are you eating adequately and properly (eg, are you eating three main meals and three snacks on a regular basis?)

Physical exercise: Are you exercising at a moderate level three times a week (a total of at least 150 min) or more on a regular basis (eg, brisk walking)? Please mark the most appropriate choice.

Question Medication use Nutrition Physical exercise

1. No, and I do not intend to begin using medications/eating adequately and properly/doing physical exercise on a regular basis within the next 6 months.“Precontemplation” stage 2. No, but I intend to begin using medications/eating adequately and properly/doing physical

exercise on a regular basis within the next 6 months.“Contemplation” stage

3. No, but I intend to begin using medications/eating adequately and properly/doing physical exercise on a regular basis within the next 30 days.“Preparation” stage

4. Yes, I am, but I have been using my medications/eating adequately and properly/doing physical exercise for less than 6 months.“Action” stage

5. Yes, I have been using my medications/eating adequately and properly/doing physical exercise for more than 6 months.“Maintenance” stage

In the monthly interviews, the researcher assessed each individual with the Diagnosis Form for Behavioral Change Stage in Patients with Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus. If the participant was in the action stage or came to the action stage, the motivational interviews continued to maintain their behaviour and prevent them from regressing into previ-ous behaviours. If the participant had slipped back to previprevi-ous behav-iours (in other words, they returned from the action stage to the preparation stage), the interview continued in accordance with the tar-get and approaches of the preparation stage.

The forms that had been filled out at the beginning were filled out again, except for the personal information form, and the study was terminated.

2.5.2

|Control group

The researcher collected the data from the control group at the begin-ning and in the sixth month of the study. The participants also filled out the Self‐efficacy (Competence) Scale for Patients with Type 2 Dia-betes, the Diagnosis Form for Behavioral Change Stage in Patients with Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus, and the Metabolic Control Diagnosis Form.

The participants in the control group received no TTM‐based moti-vational interviews. Instead, they continued to receive the usual care in the polyclinic, including diagnosis tests and medication treatment. Participants who maintained their blood glucose levels were recom-mended to come for check‐up every 3 months; if their blood glucose levels were not regulated, they were recommended to come for check‐up every 10 days. This check‐up only reviewed medication. If the participant used insulin, the diabetes education nurse or insulin educator in the polyclinic provided education regarding the features and use of insulin. Participants who sought care at the polyclinic were also provided with diabetes mellitus education between 9 and 10AM once a week. This education was provided to groups of approximately 10 individuals using a narration method and slide presentation in a sin-gle session. Since the DM training was provided once a week, not all the individuals in the study received this training.

The study was terminated in the sixth month, and afterwards, the researcher provided training to the participants about nutrition, exer-cise, and medication use.

2.6

|Data analysis

Data were analysed using SPSS Statistics version 22.0 (IBM Corp., Armonk, New York, USA). The number of units (n), percentage (%), mean (standard deviation [SD]), and 25th and 75th percentile values of the median (median [25%‐75%]) were determined as the summary statistics. Whether the number of samples was adequate in each group was assessed with power analysis. The normal distribution of data was assessed with a Shapiro‐Wilk test and Q‐Q plot. The inde-pendent samples t test was used for the normally distributed vari-ables; a Mann‐Whitney U test and Wilcoxon test were used for the nonnormally distributed variables. For the comparison of cate-gorical variables, the exact method of chi‐square test was used and

P < .05 was regarded as statistically significant. The researcher per-formed intention‐to‐treat analysis for the lost data. An initial analysis was conducted within the study. The individuals that did not com-plete the intervention and the sixth‐month monitoring was also included in the analysis. For this procedure, the researcher assigned the missing values using the expectation‐maximization method with missing value analysis.

2.7

|Ethical considerations

Approval was obtained from the Ethics Committee of University Clin-ical Studies (EUCS), EUCS No: 2013/14, 08.01.2013. Study partici-pants were informed according to an informed volunteer consent form, and their written consent was obtained. This study was funded by the Scientific Research Project Coordination Department at Erciyes University (project No.: TDK‐2013‐4699). International Standard Randomised Controlled Trial Number Register (ISRCTN): 15662612.

3

|R E S U L T S

3.1

|Descriptive characteristics

The study had 70 participants. Table 2 shows the distribution of descriptive characteristics of the participants. The groups were similar in terms of descriptive characteristics (age, sex, educational level, and disease duration) (P > .05).

3.2

|Self

‐efficacy

The self‐efficacy scores in both groups increased, but the increase was higher in the intervention group. The intragroup and intergroup differ-ences (apart from the physical exercise subscale score of self‐efficacy) were statistically significant in both groups (P < .05) (Table 3).

3.3

|Metabolic values

The difference between the baseline and sixth‐month follow‐ups in the intervention group for metabolic values was significant (P < .05). In the between‐group comparison, the metabolic values were statisti-cally significant, and the decrease in metabolic values in the interven-tion group was significant (P < .05) (Table 3). At the sixth month of intervention and control groups, the Cohen's effect size of the HbA1c value was 1.0. The Cohen's effect size of the HbA1c value of the inter-vention group was 0.7 with regard to the change between baseline and sixth months within that group (Table 3).

3.4

|Number of steps

Most participants in the intervention group (76.0%) did not have reg-ular exercise habits at baseline. The mean (SD) number of steps mea-sured using the pedometer was 4338.12 (2326.96) 1 month after the first TTM‐based motivational interview (first follow‐up), and 5271.04

(2162.30) at the sixth‐month follow‐up. The difference in number of steps between the follow‐ups in the intervention group was statisti-cally significant (P < .05). According to intragroup comparisons, the dif-ference between the first follow‐up and the sixth‐month follow‐up was statistically significant (P < .05), and the number of steps increased at the sixth‐month follow‐up compared with the first follow‐up.

3.5

|Behaviour change stage of nutrition, exercise,

and medication use

The groups were similar in terms of nutrition, exercise, and medication use behaviour stages at baseline (P > .05). At the sixth‐month follow‐ up in the intervention group, 96.0% of participants were in the action stage for nutrition, 92.0% for exercise, and 96.0% for medication use. At the sixth‐month follow‐up in the control group, 16.0% of partici-pants were in the action stage for nutrition, 8.0% for exercise, and 60.0% for medication use. The groups were different in terms of nutri-tion, exercise, and medication use behaviour stages at the sixth‐month follow‐up (P < .05).

4

|D I S C U S S I O N

In this study, the use of a TTM‐based motivational interview technique for improving self‐efficacy, maintaining metabolic control, and devel-oping positive health behaviours in people with T2DM was assessed. An important aspect of this study is the use of nutrition, exercise,

and medication approaches together. For comparison of results, the literature was consulted for studies assessing the effect of motiva-tional interviews on the health results of people with T2DM and education‐based research because of the limited number of studies related to the model.

4.1

|Self

‐efficacy

The self‐efficacy level is an important indicator for health behaviour change, and self‐efficacy increases or decreases a person's motiva-tion for engaging in acmotiva-tion (Redding, Rossi, Rossi, Velicer, & Prochaska, 2000). In the present study, the TTM‐based motivational interview seemed to be an effective method for developing self‐ efficacy, appeared to help the study participants increase control over their health, and encouraged them to change their nutrition, exercise, and medication use behaviours in a positive way. The results supported the H1 hypothesis (Table 3). Similar to the results of this study, in other studies, it was reported that the motivational interview caused self‐efficacy scores to increase (Chen et al, 2012; Meybodi, Pourshrifi, Dastbaravarde, Rostami, & Saeedii, 2011). How-ever, Heinrich et al (2010) reported that the motivational interview did not significantly increase the self‐efficacy scores between groups. Planned education programmes provided for patients with DM affected their self‐efficacy in a positive way, increased their self‐efficacy perceptions (Atak, Gurkan, & Kose, 2009; Olgun & Akdoğan Altun, 2012; Jalilian, Motlagh, Solhi, & Gharibnavaz, 2014). In the present study, as distinct from the education‐based studies TABLE 2 Distribution of descriptive characteristics of participants

Descriptive Characteristic

Intervention Group (n = 35) Control Group (n = 35)

P Mean (SD)d Median (25%‐75%) Mean (SD)d Median (25%‐75%) Age, y 49.34 (6.96) 51.71 (7.65) .180a HbA1c, % 8.20 (7.50‐9.20) 8.20 (7.40‐9.50) .576b BMI, kg/m2 37.88 (30.93‐43.30) 34.81 (29.83‐38.27) .036b

Self‐efficacy scale (total score) 59.31 (7.00) 61.68 (5.56) .121a

Sex n % n %

Female 25 71.4 21 60.0 .450c

Male 10 28.6 14 40.0

Educational level

Elementary school or less 24 68.6 28 80.0 .413c

High school or more 11 31.4 7 20.0

Disease duration

≤5 y 9 25.7 15 42.9 .208c

>5 y 26 74.3 20 57.1

Abbreviation: BMI, body mass index. at test.

b

Mann‐Whitney U test. cχ2test.

TABLE 3 Dist ribution of the self ‐efficacy score s and the me tabolic v alues of particip ants in the interven tion and control group s Variable Intervention Group Control Group Comparison of Difference Between the Groups P At Baseline Sixth ‐month follow ‐up P At Baseline Sixth ‐month follow ‐up P Mean (SD) Median (25% ‐75%) Mean (SD) Median (25% ‐75%) Mean (SD) Median (25% ‐75%) Mean (SD) Median (25% ‐75%) Diet and food control subscale 32.82 (4.61) 47.20 (10.42) <.001 a 34.88 (4.07) 37.91 (3.79) <.001 a <.001 b 33.00 (30.00 ‐36.00) 53.00 (37.00 ‐54.00) 35.00 (31.00 ‐38.00) 38.00 (35.00 ‐41.00) Medical treatment subscale 16.94 (2.58) 21.60 (3.84) <.001 a 17.25 (2.44) 18.80 (2.85) .001 a .001 b 17.00 (15.00 ‐19.00) 24.00 (18.00 ‐24.00) 17.00 (15.00 ‐19.00) 19.00 (16.00 ‐21.00) Physical exercise subscale 9.54 (1.61) 11.97 (2.59) <.001 a 9.54 (1.42) 9.68 (1.54) .735 a <.001 b 9.00 (8.00 ‐11.00) 13.00 (10.00 ‐14.00) 9.00 (9.00 ‐11.00) 10.00 (9.00 ‐11.00) Total self ‐efficacy scale score 59.31 (7.00) 80.77 (16.25) <.001 a 61.68 (5.56) 66.40 (6.11) <.001 a <.001 b 60.00 (54.00 ‐63.00) 90.00 (64.00 ‐92.00) 62.00 (57.00 ‐65.00 66.00 (64.00 ‐69.00) Preprandial blood glucose 230.44 (74.68) 170.37 (73.56) <.001 a 209.05 (76.82) 185.19 (71.39) .030 a .023 b 226.70 (178.00 ‐278.50) 138.00 (123.00 ‐217.00) 197.00 (145.00 ‐236.00) 171.00 (136.00 ‐227.00) Postprandial blood glucose 291.66 (102.30) 215.42 (100.26) <.001 a 310.50 (111.13) 274.96 (90.89) .051 a .038 b 266.00 (225.00 ‐352.00) 196.00 (156.00 ‐250.00) 310.00 (220.00 ‐374.00) 260.00 (214.00 ‐320.00) HbA1c, % 8.34 (0.99) 7.46 (1.13) <.001 a 8.57 (1.28) 8.31 (1.47) .189 a .043 b 8.20 (7.50 ‐9.20) 7.20 (6.60 ‐7.90) 8.20 (7.40 ‐9.50) 8.20 (7.20 ‐9.20) Weight, kg 97.68 (17.58) 95.32 (17.16) <.001 a 87.44 (13.48) 86.84 (13.67) .106 a .020 b 98.40 (83.35 ‐108.65) 96.65 (79.80 ‐104.50) 84.25 (77.30 ‐95.35) 85.50 (75.05 ‐94.00) BMI, kg/m 2 37.64 (6.89) 36.49 (6.24) <.001 a 34.70 (6.15) 34.21 (6.13) .071 a .036 b 37.88 (30.93 ‐43.30) 37.75 (30.70 ‐40.99) 34.81 (29.83 ‐38.27) 34.40 (30.02 ‐37.53) Waist circumference 112.15 (12.19) 109.31 (12.51) <.001 a 107.11 (11.06) 106.34 (10.80) .053 a .031 b 111.00 (103.00 ‐122.00) 109.00 (99.00 ‐122.00) 104.00 (99.00 ‐115.00) 103.00 (99.00 ‐114.00) Abbreviation: BMI, body mass index. aWilcoxon test bMann ‐Whitney U test. The comparison of differences at baseline and sixth ‐month follow ‐ups in the intervention and control groups.

with motivational interviews, the participants' cognitive, psychologi-cal, and behavioural aspects were assessed together. This multiface-ted assessment might have provided additional benefit for participants in maintaining their terminal behaviours and helping them to maintain their motivation. The results support the H3 to H5 hypotheses.

4.2

|Number of steps

Nutrition, physical exercise, and medication constitute three essential bases for DM treatment (Kara & Çinar, 2011; ADA, 2017). In this respect, exercise has an extremely important place in the treatment of DM, and pedometers can be used as a motivational tool to increase daily physical activity (Baker et al, 2008). In the present study, the number of steps in the intervention group increased at the sixth‐ month follow‐up compared with the first follow‐up; the mean number of steps at the sixth‐month follow‐up was 5271, so the targeted num-ber of steps (3500‐5500) was achieved (Tudor‐Locke, Washington, & Hart, 2009). Results related to the effect of motivational interviews on physical activity and education‐based studies on physical activity vary across studies (Atak et al, 2009; Heinrich et al, 2010; Jansink et al, 2013; Kirk et al, 2003; Olgun & Akdoğan Altun, 2012).

Although the effects of both behavioural and education‐based studies on physical exercise behaviour varied, the motivation‐based intervention may be effective in maintaining behaviour. The pedome-ters used as a motivational tool to encourage the participants in this study might promote more physical activity, and physical activity is associated with glycaemic control (Poskiparta, Kasila, & Kiuru, 2006; Umpierre et al, 2011).

4.3

|Metabolic control

As in the present study, conducting motivational interviews that focus on the behavioural components of change in ensuring glycaemic control can be more effective than the methods used in education‐based stud-ies (Jones et al, 2014). In the present study, the HbA1c level decreased 1.22% at the sixth‐month follow‐up. The participants in the interven-tion group were closer to the targets for HbA1c level (less than 7.0%), preprandial blood glucose level (70‐130 mg/dL), and postprandial blood glucose level (less than 180 mg/dL) suggested by the ADA (2016) (Table 3), and these results support the H2 hypothesis. Discussing behavioural components (nutrition, exercise, and medication) together within the conceptual framework of TTM had a strong effect on ensur-ing glycaemic control. Studies report that the change in HbA1c level is 0.41% to 1.20% (Kartal & Özsoy, 2014; Kitiş & Emiroğlu, 2006; Shibayama, Kobayashi, Takano, Kadowaki, & Kazuma, 2007; Welch et al, 2011; West et al, 2007). Planned education programmes caused mild improvements in glycaemic control in the short term (Minet et al, 2010; Norris, Lau, Smith, Schmid, & Engelgau, 2002). However, education‐based studies cannot ensure the necessary behavioural changes required for healthy DM management in the short term (McGloin, Timmins, Coates, & Boore, 2015). Indeed, the behavioural

intervention regarding nutrition, physical exercise, and medication use is more effective in ensuring permanent development of glycaemic control.

In the present study, participants' weight, BMI, and waist circumfer-ence values were examined as indicators of nutrition behaviour. Having these values at normal levels ensures glycaemic control. In the present study, the weight change in the sixth month was 3.30 kg, whereas the change was 4.70 kg in the study of West et al (2007) examining the effect of motivational interviews on weight loss. The difference in the weight change may be because the participants in the intervention group in West et al (2007) received a group‐based behavioural weight control programme as well as the motivational interview, and this pro-gramme might have provided additional benefit for weight loss. In other studies, which differ in working time, there was no difference between groups for VKI (Meybodi et al, 2011; Rubak, Sandbæk, Lauritzen, Borch‐ Johnsen, & Christensen, 2011), weight, and waist circumference (Rosenbek Minet et al, 2011). The results of the that studies show that it takes more time for people to make the desired behaviour change at the cognitive level before the effectiveness of the motivational inter-view than after it (Rubak, Sandback, Lauritzen, & Christensen, 2005). In a study based on nutrition education for people withT2DM, no differ-ence was found between the groups in terms of weight and BMI values according to the assessment conducted 1 month after the intervention (Sharifirad, Entezari, Kamran, & Azadbakht, 2009). As distinct from the methods used in the present study, addressing only nutrition and the short duration of the assessment may have had an effect on obtaining these different results.

4.4

|Behaviour change stage of nutrition, exercise,

and medication use

A randomized controlled study to assess the effect of nutrition, phys-ical activity, and medication use on behaviour change reported that the HbA1c level increased in both intervention and control groups, that the increase was higher in the control group, and that the diet and exercise change stages of the intervention group showed more positive improvement; however, the activity in the change stages of medication use was lower (Partapsingh, Maharaj, & Rawlins, 2011). The result of the present study differs from that of the study con-ducted by Partapsingh et al (2011) because the change in the HbA1c level and the nutrition, exercise, and medication use behaviour change stages were at higher levels. The intervention group showed greater improvement in terms of this positive behaviour change and in the metabolic values than did the control group. Another reason why the intervention group showed better improvement in terms of metabolic values may be their regular medication use.

4.5

|Limitations

This study sample was limited because the study was conducted in patients who applied to a health care centre. The study results cannot be generalized because of the experimental design used in the study,

but they can contribute to the generalization. The potential bias of the evaluators and the nonblind nature of the study were limitations of the study. Additionally, the small sample size and self‐reported mea-surement can be as potential sources of bias. The researcher had con-versations by observing the motivational conversation guide, which they developed themselves, throughout the study, they were strictly loyal to the principles of motivational conversation, which contributed to the limitation of the study. One of the limitations of the study is that only the participants in the intervention group were provided with pedometers and glucose metres. Future research designs can be created considering this limitation and the effect of motivational interviews of behavioural change can be determined more clearly by providing the control group with the same tools (pedometer and glucose metre). Monthly interviews are not cost‐effective because they require intense effort. However, the motivational interviews can be more cost‐ effective, and the same results can be obtained after the number of interview sessions are planned according to individuals. The individuals who left the study also limit the study results. However, their group distributions at the beginning were examined and found to be similar. Although the interviews were conducted with participants in the inter-vention and control groups by appointment during the follow‐ups, there may have been short‐term interactions between the two groups.

5

|C O N C L U S I O N

The present study showed that using the TTM‐based motivational interview in patients with T2DM increased the level of their self‐ efficacy and positively affected their metabolic control and health behaviour change.

The TTM‐based motivational interview method for encouraging positive health behavioural (nutrition, exercise, and medication use) changes in adults with T2DM who resist behavioural change is needed to achieve successful management of T2DM. Health care providers can easily apply theTTM‐based motivational interview method. In addi-tion, health professionals' knowledge and experience can be improved by including the motivational interview method in the undergraduate curricula of nursing as well as in‐service training programmes. Further studies should be based on behavioural approaches and examine the long‐term effects of the motivational interview, taking into consider-ation the frequency of the motivconsider-ational interviews, the durconsider-ation of use, and having the TTM‐based motivational interviews conducted by nurses specializing in the area being studied. Moreover, further studies are needed for the comparison of the effect durations of the education‐ based studies and the motivational interview on positive behaviour change. A retrospective study assessing the long‐term effect of the intervention in the present study is ongoing.

A C K N O W L E D G E M E N T

We would like to thank Ferhan Elmalı (Department of Biostatistics and Medical Informatics,İzmir Katip Çelebi University, PhD Associate Pro-fessor Departmental Director) for his contribution to the evaluation of the statistical findings.

C O N F L I C T O F I N T E R E S T

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interests.

A U T H O R S H I P S T A T E M E N T

AST and HZ designed the study. AST collected the data. AST and HZ analysed the data and prepared the manuscript. All authors approved the final version for submission.

O R C I D

Alime Selçuk‐Tosun https://orcid.org/0000-0002-4851-0910

Handan Zincir https://orcid.org/0000-0002-1722-4647

R E F E R E N C E S

American Diabetes Association (ADA) (2017). Standards of medical care in diabetes. Diabetes Care, 40(Supplement1), 1–135. https://doi.org/ 10.2337/dc17‐S003

Atak, N., Gurkan, T., & Kose, K. (2009). The effect of education on knowl-edge, self‐management behaviours and self‐efficacy of patients with type 2 diabetes. Australian Journal of Advanced Nursing, 26, 66–74. Baker, G., Mutrie, N., & Lowry, R. (2008). Using pedometers as motivational

tools: are goals set in steps more effective than goals set in minutes for increasing walking? International Journal of Health Promotion and Educa-tion, 46, 21–26. https://doi.org/10.1080/14635240.2008.10708123 Burbank, P. M., Reibe, D., Padula, C. A., & Nigg, C. (2002). Exercise and

older adults: changing behavior with the transtheoretical model. Orthopaedic Nursing, 21, 51–61. https://doi.org/10.1097/00006416‐ 200207000‐00009

Chapman, A., Liu, S., Merkouris, S., Enticott, J. C., Yang, H., Browning, C. J., & Thomas, S. A. (2015). Psychological interventions for the manage-ment of glycemic and psychological outcomes of type 2 diabetes mellitus in China: a systematic review and meta‐analyses of random-ized controlled trials. Frontiers in Public Health, 16, 252. https://doi. org/10.3389/fpubh.2015.00252

Chen, S. M., Creedy, D., Lin, H. S., & Wollin, J. (2012). Effects of motiva-tional interviewing intervention on self‐manegement, psychological and glycemic outcomes in type 2 diabetes: a randomized controlled trial. International Journal of Nursing Studies, 49, 637–644. https://doi. org/10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2011.11.011

Dellasega, C., Gabbay, R., Durdock, K., & Martinez‐King, N. (2010). Motiva-tional interviewing to change type 2 diabetes‐care behaviours. Journal of Diabetes Nursing, 14, 112–118.

Dray, J., & Wade, T. D. (2012). Is the transtheoretical model and motiva-tional interviewing approach applicable to the treatment of eating disorders? A review. Clinical Psychology Review, 32, 558–565. https:// doi.org/10.1016/j.cpr.2012.06.005

Gao, J., Wang, J., Zheng, P., Haardörfer, R., Kegler, M. C., Zhu, Y., & Fu, H. (2013). Effects of self‐care, self‐efficacy, social support on glycemic control in adults with type 2 diabetes. BMC Family Practice, 24, 66–72. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471‐2296‐14‐66

Gillespie, N. D., & Lenz, T. L. (2011). Implementation of a tool modify behavior in a chronic disease management program. Advances in Pre-ventive Medicine, 2011. https://doi.org/10.4061/2011/215842, 1–5. Glanz, K., Rimer, B., & Viswanath, K. (2008). Theory, research, and practice

in health behavior and health education. In K. Glanz, B. Rimer, & K. Viswanath (Eds.), Health Behavior and Health Education Theory Reserach and Practice (4th ed.) (pp. 23–40). San Francisco: Jossey‐Bass.

Heinrich, E., Candel, M. J., Schaper, N. C., & de Veries, N. K. (2010). Effect evaluation of a motivational interviewing based counselling strategy in diabetes care. Diabetes Research and Clinical Practice, 90, 270–278. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.diabres.2010.09.012

International Council of Nurses (ICN) (2010). Delivering quality, serving communities: nurses leading chronic care. Available at: http://www. icn.ch/publications/2010‐delivering‐quality‐serving‐communities‐ nurses‐leading‐chronic‐care/ (accessed 06.04.2017).

International Diabetes Federation, (2012). Clinical guidelines task force global guideline for type 2 diabetes, pp. 7–147.

Jalilian, F., Motlagh, F. Z., Solhi, M., & Gharibnavaz, H. (2014). Effectiveness of self‐management promotion educational program among diabetic patients based on health belief model. Journal of Education Health Pro-motion, 21, 75–79. https://doi.org/10.4103/2277‐9531.127580 Jansink, R., Braspenning, J., Keizer, E., van der Weijden, T., Elwyn, G., &

Grol, R. (2013). No identifiable Hb1Ac or lifestyle change after a com-prehensive diabetes programme including motivational interviewing: a cluster randomised trial. Scandinavian Journal of Primary Health Care, 31, 119–127. https://doi.org/10.3109/02813432.2013.797178 Jones, A., Gladsone, B. P., Lübeck, M., Lindekilde, N., Upton, D., & Vach, W.

(2014). Motivational interventions in the management of HbA1c levels: a systematic review and meta‐analysis. Primary Care Diabetes, 8, 91–100. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pcd.2014.01.009

Jones, H., Edwards, L., Vallis, T. M., Ruggiero, L., Rossi, S. R., Rossi, J. S.,… Zinman, B. (2003). Changes in diabetes self‐care behaviors make a dif-ference in glycemic control: the diabetes stages of change (DİSC) study. Diabetes Care, 26, 732–737. https://doi.org/10.2337/diacare.26.3.732 Kara, K., & Çinar, S. (2011). The relation between diabetes care profile and metabolic control variables. Kafkas Journal of Medical Sciences, 1, 57–63. https://doi.org/10.5505/kjms.2011.41736

Kara, M., van der Bijl, J. J., Shortridge‐Bagget, L. M., Astı, T., & Erguney, S. (2006). Cross‐cultural adaptation of the diabetes management self‐ efficacy scale for patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus: scale develop-ment. International Journal of Nursing Studies, 43, 611–621. https://doi. org/10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2005.07.008

Kartal, A., & Özsoy, S. (2014). Effect of planned diabetes education on health beliefs and metabolic control in type 2 diabetes patients. Journal of Hacettepe University Faculty of Nursing, 1, 1–15.

Kirk, A., Mutrie, N., Macintyre, P., & Fisher, M. (2003). Increasing physical activity in people with type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Care, 26, 1186–1192. https://doi.org/10.2337/diacare.26.4.1186

Kitiş, Y., & Emiroğlu, N. (2006). The effects of home monitoring by public health nurse on individuals' diabetes control. Applied Nursing Research, 19, 134–143. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apnr.2005.07.007

Koyun, A., & Eroglu, K. (2013). Degişim Aşamalari Modeli (Transteoretik Model) ve Aşamalara Göre Hazırlanmış Sigarayı Bırakma Rehberi (pp. 1–127). Ankara: Palme Yayincilik. (in Turkish)

Marshall, S. J., & Biddle, S. J. H. (2001). The transtheoretical model of behavior change: a meta‐analysis of applications to physical activity and exercise. Annals of Behavioral Medicine, 23, 229–246. https://doi. org/10.1207/S15324796ABM2304_2

McGloin, H., Timmins, F., Coates, V., & Boore, J. (2015). A case study approach to the examination of a telephone‐based health coaching intervention in facilitating behaviour change for adults with type 2 dia-betes. Journal of Clinical Nursing, 24, 1246–1257. https://doi.org/ 10.1111/jocn.12692

Meybodi, F. A., Pourshrifi, H., Dastbaravarde, A., Rostami, R., & Saeedii, Z. (2011). The effectiveness of motivational interview on weight reduc-tion and self‐efficacy in Iranian overweight and obese women. Procedia‐ Social and Behavioral Sciences, 30, 1395–1398. https://doi. org/10.1016/j.sbspro.2011.10.271

Miller, S. T., Oates, V. J., Brooks, A. M., Shintani, A., Gebretsadik, T., & Jenkins, D. (2014). Preliminary efficacy of group medical nutrition ther-apy and motivational interviewing among obese African American women with type 2 diabetes: a pilot study. Hindawi Publishing Corpora-tion Journal of Obesity, 2014, 1–7. https://doi.org/10.1155/2014/ 345941

Miller, W. R., & Rollnick, S. (2009). In F. Karadag, K. Ögel, & A. E. Tezcan (Eds.), Trans. Eds.Motivational Interviewing (pp. 35, 216–45, 231). Ankara: HYB Basım Yayin Matbaasi. in Turkish

Minet, L., Moller, S., Vach, W., Wagner, L., & Henriksen, J. E. (2010). Medi-ating the effect of self‐care management intervention in type 2 diabetes: a meta‐analysis of 47 randomised controlled trials. Patient Education and Counseling, 80, 29–41. https://doi.org/10.1016/j. pec.2009.09.033

Norris, S. L., Lau, J., Smith, S. J., Schmid, C. H., & Engelgau, M. M. (2002). Self‐management education for adults with type 2 diabetes: a meta‐ analysis of the effect on glycemic control. Diabetes Care, 25, 1159–1171. https://doi.org/10.2337/diacare.25.7.1159

Olgun, N., & Akdoğan Altun, Z. (2012). Effects of education based on health belief model on nursing implication in patients with diabetes. Journal of Hacettepe University Faculty of Nursing, 19, 46–57. Partapsingh, V. A., Maharaj, R. G., & Rawlins, J. M. (2011). Applying the

stages of change model to type 2 diabetes care in Trinidad: a randomised trial. Journal of Negative Results in Biomedicine, 10, 13. https://doi.org/10.1186/1477‐5751‐10‐13

Pekcan, G. (2011). In A. Baysal, M. Aksoy, & H. J. Besler (Eds.), ve arkBeslenme Durumunun Saptanmasi.İçinde: Diyet El kitabı. Yenilenmis 6. Baski (pp. 67–143). Ankara: Hatipoglu Yayinlari. In Turkish Pichayapinyo, P., Lagampan, S., & Rueangsiriwat, N. (2015). Effects of a

dietary modification on 2 h postprandial blood glucose in Thai popula-tion at risk of type 2 diabetes: an applicapopula-tion of the stages of change model. International Journal of Nursing Practice, 21, 278–285. https:// doi.org/10.1111/ijn.12253

Poskiparta, M. K., Kasila, K., & Kiuru, P. D. (2006). Dietary and physical activity counseling on type 2 diabetes and impaired glucose tolerance by physicians and nurses in primary healthcare in Finland. Scandinavian Journal of Primary Health Care, 24, 206–210. https://doi.org/10.1080/ 02813430600866463

Poursharif, H., Babapur, J., Zamani, R., Besharat, M. A., Mehryar, A. H., & Rajab, A. (2010). The effectiveness of motivational interviewing in improving health outcomes in adults with type 2 diabetes. Procedia‐ Social and Behavioral Sciences, 5, 1580–1584. https://doi.org/10. 1016/j.sbspro.2010.07.328

Prochaska, J. O., & DiClemente, C. C. (1982). Transtheoretical therapy: toward a more integrative model of change. Psychotherapy, 19, 276–288. https://doi.org/10.1037/h0088437

Prochaska, J. O., DiClemente, C. C., & Norcross, J. C. (1992). In search of how people change, applications to addictive behaviours. American Psychologist, 47, 1102–1114.

Prochaska, J. O., & Velicer, W. F. (1997). The transtheoretical model of health behavior change. American Journal of Health Promotion, 12, 38–48. https://doi.org/10.4278/0890‐1171‐12.1.38

Redding, C. A., Rossi, J. S., Rossi, S. R., Velicer, W. F., & Prochaska, J. O. (2000). Health behavior models. The International Electronic Journal of Health Education, 3, 180–193.

Rosenbek Minet, L. K., Wagner, L., Lonving, E. M., Hjelmborg, J., & Henriksen, J. E. (2011). The effect of motivational interviewing on glycaemic control and perceived competence of diabetes self‐ management in patients with type 1 and type 2 diabetes mellitus after attending a group education programme: a randomised controlled trial.

Diabetologia, 54, 1620–1629. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00125‐011‐ 2120‐x

Rubak, S., Sandback, A., Lauritzen, T., & Christensen, B. (2005). Motiva-tional interviewing: a systematic review and meta‐analysis. British Journal of General Practice, 55, 305–312.

Rubak, S., Sandbæk, A., Lauritzen, T., Borch‐Johnsen, K., & Christensen, B. (2011). Effect of“motivational interviewing” on quality of care measures in screen detected type 2 diabetes patients: a one‐year follow‐up of an RCT, ADDITION Denmark. Scandinavian Journal of Primary Health Care, 29, 92–98. https://doi.org/10.3109/02813432.2011.554271 Saglik Bakanligi, (2011). Temel Sağlık Hizmetleri Genel Müdürlügü (pp.

18–45). Ankara: Türkiye Diyabet Önleme ve Kontrol Programı Eylem Plani (2011–2014. In Turkish

Salehi, L., Mohammad, K., & Montazeri, A. (2011). Fruit and vegetables intake among elderly Iranians: a theory‐based interventional study using the five‐a‐day program. Nutrition Journal, 10, 123. https://doi. org/10.1186/1475‐2891‐10‐123

Sharifirad, G., Entezari, M. H., Kamran, A., & Azadbakht, L. (2009). The effectiveness of nutritional education on the knowledge of diabetic patients using the health belief model. Journal of Research Medical Sci-ences, 14, 1–6.

Shibayama, T., Kobayashi, K., Takano, A., Kadowaki, T., & Kazuma, K. (2007). Effectiveness of lifestyle counseling by certified expert nurse of Japan for non‐insulin‐treated diabetic outpatients: a 1‐year random-ized controlled trial. Diabetes Research and Clinical Practice, 76, 265–268. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.diabres.2006.09.017

Shinitzky, H. E., & Kub, J. (2001). The art of motivating behavior change: the use of motivational interviewing to promote health. Public Health Nurs-ing, 18, 178–185. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1525‐1446.2001.00178.x Stuifbergen, A. K., Seraphine, A., & Roberts, G. (2000). An explanatory

model of health promotion and quality of life in chronic disabling con-ditions. Nursing Research, 49, 122–129. https://doi.org/10.1097/000 06199‐200005000‐00002

Tudor‐Locke, C., Washington, T. L., & Hart, T. L. (2009). Expected values for steps/day in special populations. Preventive Medicine, 49, 3–11. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ypmed.2009.04.012

Umpierre, D., Ribeiro, P. A., Kramer, C. K., Leitão, C. B., Zucatti, A. T., Azevedo, M. J.,… Schaan, B. D. (2011). Physical activity advice only structured exercise training and association with HbA1c levels in type 2 diabetes: a systematic review and meta‐analysis. The Journal of the American Medical Association, 305, 1790–1799. https://doi.org/ 10.1001/jama.2011.576

Van der Bijl, J., Van Poelgeest‐Eeltink, A., & Shortridge‐Baggett, L. (1999). The psychometric properties of the diabetes management self‐efficacy scale for patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 30, 352–359. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1365‐2648.1999. 01077.x

Van Nes, M., & Sawatzky, J. A. (2010). Improving cardiovascular health with motivational interviewing: a nurse practitioner perspective. Jour-nal of the American Academy of Nurse Practitioners, 22, 654–660. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1745‐7599.2010.00561.x

Velicer, W. F., Prochaska, J. O., Fava, J. L., Rossi, J. S., Redding, C. A., Laforge, R. G., & Robbins, M. L. (2000). Using the transtheoretical model for population‐based approaches to health promotion and disease prevention. Homeostasis in Health and Disease, 40, 174–195. Walker, R. J., Smalls, B. L., Hernandez‐Tejada, M. A., Campbell, J. A., &

Egede, L. E. (2014). Effect of diabetes self‐efficacy on glycemic control, medication adherence, self‐care behaviors, and quality of life in a pre-dominantly low‐income, minority population. Ethinicity & Disease, 24, 349–355.

Welch, G., Zagarins, S. E., Feinberg, R. G., & Garb, J. L. (2011). Motivational interviewing delivered by diabetes educators: does it improve blood glucose control among poorly controlled type 2 diabetes patients? Dia-betes Research and Clinical Practice, 91, 54–60. https://doi.org/ 10.1016/j.diabres.2010.09.036

West, D. S., Dilillo, V., Bursac, Z., Gore, S. A., & Greene, P. G. (2007). Moti-vational interviewing improves weight loss in women with type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Care, 30, 1081–1087. https://doi.org/10.2337/ dc06‐1966

World Health Organization (WHO), (2010). Global status report on noncommunicable diseases. p 15–16. Available at: www.who.int/ nmh/publications/ncd_report_full_en.pdf (accessed: 06.03.2017) Yildiz, E. (2008). Diyabet ve Beslenme (pp. 7–14). Klasmat Matbaacilik,

Ankara: Birinci Basim. (in Turkish)

How to cite this article: Selçuk‐Tosun A, Zincir H. The effect of a transtheoretical model–based motivational interview on self‐efficacy, metabolic control, and health behaviour in adults with type 2 diabetes mellitus: A randomized controlled trial. Int J Nurs Pract. 2019;25:e12742. https://doi.org/10.1111/ ijn.12742