THE FREEDOM OF ESTABLISHMENT AND TO

PROVIDE SERVICES: A COMPARISON OF THE

FREEDOMS IN EUROPEAN UNION LAW AND

TURKEY–EU ASSOCIATION LAW

İlke Göçmen

*Abstract

The association law between Turkey and the Union has been a source of rights for certain Turkish nationals, thanks to the decisions of the European Court of Justice. In this respect, the recent years have witnessed the increasing importance of Article 41(1) of the Additional Protocol – the standstill provision concerning the freedom of establishment and to provide services – in the case law of the Court. One striking example is the Soysal case which paved the way for certain Turkish nationals to travel to Germany without a visa. Thus, a need has emerged to explore the exact boundaries of this article in particular, and the scope and effects of the freedoms of establishment and to provide services in association law in general. Accordingly, this paper is an effort to examine the scope and effects of the said freedoms in association law by comparing them with the same freedoms in European Union law.

Öz

Türkiye ve Birlik arasındaki ortaklık hukuku, Adalet Divanı kararları sayesinde belirli Türk vatandaşları için bir hak kaynağı olmuştur. Bu hususta yakın geçmişteki yıllar, Divanın içtihat hukukunda Katma Protokol md. 41(1)’in

* Dr. Assistant Professor at the Ankara University School of Law of the University of

Ankara. I wish to thank to Prof. A. Sacha Prechal, Dr. Sybe de Vries, Aleidus J.T. Woltjer and Assoc. Prof. Dr. Sanem Baykal for their comments on the different aspects of the subject matter. Author may be contacted at ilkegocmen81@yahoo.com.

– yerleşme ve hizmet sunumu serbestîsine ilişkin standstill hükmünün – artan önemine tanıklık etmiştir. Belirli Türk vatandaşlarının Almanya’ya vize olmaksızın seyahat etmesinin yolunu açan Soysal davası, bu alandaki çarpıcı örneklerden bir tanesidir. Böylelikle özel olarak söz konusu maddenin tam sınırlarının ve genel olarak ortaklık hukukundaki yerleşme ve hizmet sunumu serbestîsinin kapsam ve etkilerinin incelenmesi ihtiyacı doğmuştur. Bundan dolayı bu makale, Birlik hukukundaki yerleşme ve hizmet sunumu serbestîsi ile karşılaştırmak yoluyla, mevzubahis serbestîlerin ortaklık hukukundaki kapsam ve etkilerini incelemeyi amaçlamaktadır.

Key Words: Freedom of establishment, freedom to provide services,

(personal, material and temporal) scope, restrictions and justifications, standstill provision.

Anahtar Kelimeler: Yerleşme serbestîsi, hizmet sunumu serbestîsi, (kişi,

konu ve zaman bakımından) kapsam, kısıtlama ve haklı gösterme, standstill hükmü.

INTRODUCTION

Initially just words on papers, the association law1 between the Republic of Turkey and the European Union (“EU”)2 grants rights to Turkish citizens which are legally enforceable before the national authorities and courts of the Member States, thanks to the decisions of the European Court of Justice (“ECJ”). In recent years, a new wave of cases has broken on the shores of the legal regime of the Member States and EU. These were related to Article 41(1) of the Additional Protocol (“AP”), which is a standstill provision concerning the freedom of establishment and to provide services in association law.

In 2000, the ECJ decided the Savas case which, for the first time, referred to Article 41(1) of the AP as directly effective.3 In the three subsequent cases concerning this article, namely the Abatay and Sahin, Tüm and Darı and Soysal cases, the Court clarified the interpretation of this Article.4 The Soysal case

1 The term ‘association law’ refers to the Ankara Agreement (“AA”) and other acts such

as the Additional Protocol (“AP”) which form an integral part of the AA.

2 In this article, the term ‘European Union’ (EU) will be used instead of “European

Community” since the Treaty of Lisbon, which entered into force in December 2009, refers only to the former.

3 Case C-37/98, The Queen and Secretary of State for the Home Department ex parte:

Abdulnasir Savas [2000] ECR I-2927.

4 Joined Cases C-317/01 and 369/01, Eran Abatay and Others and Nadi Sahin v.

Bundesanstalt für Arbeit, [2003] ECR I-12301; Case C-16/05, The Queen, Veli Tum and Mehmet Dari v. Secretary of State for the Home Department, [2007] ECR I-7415;

especially, which paved the way for certain Turkish nationals to travel to some of the Member States without a visa, met with rousing enthusiasm in Turkey. Hence, this shows us that there is a strong need to explore, on the one hand, the exact boundaries of this article in particular, and on the other hand, the scope and effects of the freedom of establishment and to provide services in association law in general.

This exploration yet forces us to examine these freedoms in EU law, essentially Articles 49 and 56 of the Treaty on the Functioning of the European Union (“TFEU”). This examination is needed, not only because of the fact that the Ankara Agreement (“AA”) (and association law) was heavily inspired by the Founding Treaties (and EU law), but also for the reason that the ECJ interprets association law, as far as possible, in accordance with EU law. Thus, the scrutiny of the EU law aspect of these freedoms is required in order to compare those freedoms in EU and association law which will facilitate reaching conclusions regarding the scope and effects of them in association law.

Accordingly, this article makes an effort to answer the following questions: What are the similarities and differences between the freedom of establishment and to provide services in European Union and association law? What conclusions can be drawn with regard to the scope and effects of those freedoms in association law from their counterparts in European Union law?

In accordance with these questions, therefore, the first section of this article will be devoted to the freedom of establishment and to the freedom to provide services in EU law. The second section will be dedicated to the same freedoms in association law. Both of the chapters are divided into similar subheadings under which the ‘relevant provisions’ of those freedoms and their ‘impact upon European Union law’ will be examined. The latter comprises the ‘direct effect’, ‘scope’ (personal, material, temporal) and ‘effects’ (restriction and justification plus limits) of the relevant provisions.

I. THE FREEDOMS OF ESTABLISHMENT AND TO PROVIDE SERVICES UNDER EUROPEAN UNION LAW

The relevant rules on freedom of establishment and the freedom to provide services in association law are guided by the principles of European Union law.5

This has also been reflected in the case law of the ECJ. In this context, the Court has already ruled that the principles enshrined in the provisions of the Treaty relating to the freedoms of establishment and to provide services must be

Case C-228/06, Mehmet Soysal, Cengiz Salkim, Ibrahim Savatli v. Bundesrepublik Deutschland [2009] ECR I-1031.

extended, as far as possible, to Turkish nationals with the aim of eliminating restrictions on those freedoms between the contracting parties.6

For these reasons, it is first necessary to explain the provisions of free movement relating to the establishment and services in European Union law. Next the relevant provisions regarding those freedoms and the impact of these provisions in European Union law will be examined.

A. Relevant Provisions of EU Law

Regarding the freedom of establishment, the relevant provisions are Articles 49, 51 and 52 of the TFEU.7 To mention briefly, Article 49, first of all, prohibits discrimination on the grounds of nationality which states that the “restrictions on the freedom of establishment of nationals of a Member State in the territory of another Member State shall be prohibited.” These prohibitions are valid for companies or firms as well.8 The freedom of establishment includes “the right

to take up and pursue activities as self-employed persons and to set up and manage undertakings.” Articles 51 and 52 lay down the exceptions to this freedom. These exceptions relate to the measures taken on the grounds of “exercise of official authority” and “public policy, public security or public health.”

Regarding the freedom to provide services, the relevant provisions are Articles 56, 57 and 62 of the TFEU.9 Article 56, in the first place, prohibits

discrimination on the grounds of nationality. In addition to this, it declares that the “restrictions on freedom to provide services within the [European] Union shall be prohibited in respect of nationals of Member States who are established in a Member State other than that of the person for whom the services are intended.” Article 57 lists some examples of services and defines service as things provided for remuneration and highlights its temporary character. Article 62 refers, inter alia, to the fact that companies or firms are also within the scope of the freedom to provide services and lists the exceptions to this freedom, namely, “exercise of official authority” and “public policy, public security or public health.”

B. Impact upon EU Law

The impact of the provisions relating to the freedoms of establishment and to provide services upon EU law is examined by first looking at the direct effect of Articles 49 and 56 of the TFEU, then examining the scope of these provisions. Lastly, their effects on the EU legal order are revealed.

6 See Abatay and Sahin, para. 112.

7 These are the Articles that are referred to by Article 13 of the AA. 8 Companies or firms are defined in Article 54 of the TFEU. 9 These are the articles that are referred by Article 14 of the AA.

1. Direct effect

Articles 49 and 56 of the TFEU are parts of the Founding Treaties. Therefore, they will have direct effect as long as they are ‘clear and unambiguous,’ ‘unconditional’ and ‘not dependent on further action.’10 The

Court has decided that these articles pass this test for direct effect and have been directly effective since the expiration of the transitional period.11 Therefore,

these articles “create individual rights which national courts must protect.”12 Next, we will consider the scope of the freedoms of establishment and to provide services in EU law, so as to determine the situations in which these articles may intervene.

2. Scope

The freedoms of establishment and to provide services have personal, material and temporal scope. I will scrutinize them in turn.

Personal scope concerns those persons who can benefit from Articles 49 and 56 of the TFEU. These provisions can be relied upon, not only by individuals, but also by companies or firms. As a preliminary observation, individuals must hold the nationality of one of the Member States; companies or firms must be formed in accordance with the law of a Member State and have their registered office, central administration or principal place of business within the EU.13

The freedom of establishment, with respect to individuals, requires that person to be self-employed. A person who pursues an economic activity is regarded as self-employed when he/she works outside any relationship of subordination, under his/her own responsibility and in return for remuneration paid directly to him/her, directly and fully.14 Regarding undertakings, the

freedom of establishment necessitates the actual establishment of that

10 See Trevor Hartley, THE FOUNDATIONS OF EUROPEAN COMMUNITY LAW 193-97 (6th

ed., Oxford University Press, 2007).

11 For Article 49 of the TFEU, see Case 2/74, Jean Reyners v. Belgian State, [1974]

ECR 631 para. 32. For Article 56 of the TFEU, see Case 33/74, Johannes Henricus Maria van Binsbergen v. Bestuur van de Bedrijfsvereniging voor de Metaalnijverheid, [1974] ECR 1299 para. 27.

12 See van Binsbergen, ECR 1299, para. 27.

13 For individuals, see case C-369/90, Mario Vicente Micheletti and others v.

Delegación del Gobierno en Cantabria, [1992] ECR I-4239, paras. 11, 14. For companies or firms see Article 54 of the TFEU; they may be established under civil or commercial law, including cooperative societies, and other legal persons governed by public or private law, except the non-profit-making ones.

14 See Case C-268/99, Aldona Malgorzata Jany and Others v. Staatssecretaris van

undertaking in the host Member State and the pursuit of genuine economic activity there.15

The freedom to provide services can be considered in three cases according to where the service providers move, where the service recipients move and where neither the provider nor recipient move but the service itself moves.16

Firstly, like the freedom of establishment, the freedom to provide services requires a person to be self-employed and an undertaking to pursue genuine economic activity.17 However, concerning the latter freedom, service providers

perform a service on a temporary or sporadic basis.18 Besides, in spite of the

wording of the TFEU which mentions only service providers, the Court has decided that service recipients also benefit from the freedom to provide services, since it is a ‘necessary corollary’ of this freedom.19 Persons who are

regarded as service recipients are tourists, persons receiving medical treatment and persons travelling for the purpose of (private) education or business.20

Furthermore, the service may move by telephone, Internet or cable without any movement from neither the provider nor the recipient.21

The freedom to provide services shows also a special characteristic regarding undertakings. Article 56 of the TFEU can be invoked, not only by undertakings within the meaning of that article, but also by the workers of that undertaking, since workers of the service provider are “indispensable to enable him to provide his services.”22

15 See Case C-196/04, Cadbury Schweppes plc, Cadbury Schweppes Overseas Ltd v.

Commissioners of Inland Revenue, [2006] ECR I-7995 para. 54.

16 See Catherine Barnard, THE SUBSTANTIVE LAW OF THE EU:THE FOUR FREEDOMS

355-58 (2nd ed., Oxford University Press, 2007).

17 Cf. [compare with] Jany and Others, ECR I-8615, para. 71; Cadbury, ECR I-7975,

para. 54.

18 Josephine Steiner and Lorna Woods, EULAW 474 (10th ed., Oxford University Press,

2009); see also Article 57 of the TFEU.

19 Joined Cases 286/82 and 26/83, Graziana Luisi and Giuseppe Carbone v. Ministero

del Tesoro, [1984] ECR 377, para. 10; see also Article 1/b of (repealed) Council Directive 73/148/EEC of 21 May 1973 on the Abolition of Restrictions on Movement and Residence within the Community for Nationals of Member States with Regard to Establishment and the Provision of Services, [1973] OJ L 172.

20 Luisi and Carbone, ECR 377, para. 10 and Case C-109/92, Stephan Max Wirth v.

Landeshauptstadt Hannover, [1993] ECR I-6447 para. 17.

21 See Barnard, supra note 16, at 357-58.

22 Case C-350/96, Clean Car Autoservice GesmbH v. Landeshauptmann von Wien,

[1998] ECR I-2521, paras. 19-21; compare with Abatay and Sahin, ECR 12301, paras 105-106; see also Soysal and others, ECR 1031, para. 46.

The material scope has two sides: subject matter and internal situation. The subject matter situation concerns the areas which are covered by Articles 49 and 56 of the TFEU. First will be a discussion as to what constitutes services and then what are the rights covered by the above-mentioned articles.

Firstly, in order to answer what constitutes services, the Treaty Articles and case law of the ECJ are the main sources. Article 57 of the TFEU includes a list of services which are the activities of craftsmen, the activities of the professions and the activities of an industrial or a commercial character. Article 58 of the TFEU excludes the transport sector, the banking sector and the insurance services sector which are connected with movements of capital from the provisions of ‘services.’ In addition, the case law clarifies that tourist, medical, financial, business, educational and sporting activities also constitute services.23 Secondly, Articles 49 and 56 of the TFEU give substantial rights to individuals;24 these articles cover a list of rights.25 With regard to the freedoms of establishment and to provide services, there are rights of departure, entry, residence and protection against expulsion.26 There are also rights related to the access to and exercise of these freedoms. In this regard, European Union law prohibits any unjustified measures which consist of direct or indirect discrimination or a restriction with regard to the access to and exercise of self-employed activity or access to the market in services and exercise of providing or receiving services.27

Situations that are wholly internal to a Member State are outside of the scope of the European Union law. In other words, there must be a cross-border

23 See Barnard, supra note 16, at 359-60; see also Luisi and Carbone, ECR 377, para.

10; Case 352/85, Bond van Adverteerders and Others v. Netherlands State, [1988] ECR 2085, para. 16; joined Cases C-51/96 and C-191/97, Christelle Deliège v. Ligue francophone de judo et disciplines associées ASBL, Ligue belge de judo ASBL, Union européenne de judo and François Pacquée, [2000] ECR I-2549, para. 56.

24 Compare with Article 41(1) of the AP. In this regard, see Tum and Dari, para. 55. 25 Although some of these rights are made clear by the directives, the ECJ observed that

the provisions of the directive(s) merely spell out the rights already protected by Articles 49 and 56 of the TFEU themselves. See Barnard, supra note 16, at 311, 368.

26 See (repealed) Council Directive 73/148/EEC, [1973] OJ L 172. These rights are now

regulated by Directive 2004/38/EC of the European Parliament and of the Council of 29 April 2004 on the Right of Citizens of the Union and their Family Members to Move and Reside Freely within the Territory of the Member States, [2004] OJ L 158. For right of exit, see Article 4; for right of entry, Article 5; for right of residence, Articles 6-14 and protection against expulsion, Article 28.

element.28 Articles 49 and 56 of the TFEU, therefore, cannot be applied to an

activity where there is no factor connecting that activity to a situation envisaged by European Union law.29

Temporal scope deals with the question about when Member States have been prevented from introducing restrictions on the areas covered by the Articles 49 and 56 of the TFEU. The Court has decided that these articles have been directly effective since the expiration of the transitional period and therefore “create individual rights which national courts must protect.”30 Hence,

they have been directly effective since 1 January 1970.

Until now, we have listed the situations that are within the scope (personal, material and temporal scope) of Articles 49 and 56 of the TFEU. It is now necessary to find out the effects of these articles where a situation is within their sphere of application.

3. Effects

Articles 49 and 56 of the TFEU prevent the application of conflicting national rules which cannot be justified. Nevertheless, there is one limit to invoking Articles 49 and 56, which is the abuse of rights. Here, I will examine firstly the restriction and justification issue and secondly the abuse of rights as a limit to the enjoyment of these freedoms.

Articles 49 and 56 of the TFEU prohibit not only discrimination on grounds of nationality but also restrictions on the freedoms of establishment and to provide services. The Court, first of all, determines whether a national measure breaches Articles 49 and 56 and then whether the measure can be justified by legitimate reasons provided that the principle of proportionality and the fundamental rights are observed.

28 Steiner and Woods, supra note 18, at 462. See also Kamiel Mortelmans, THE

FUNCTIONING OF THE INTERNAL MARKET:THE FREEDOMS,THE LAW OF THE EUROPEAN

UNION AND THE EUROPEAN COMMUNITIES 585-86 (4th ed., Paul Kapteyn, et. al., eds.,

Wolters Kluwer, 2008).

29 For the freedom of establishment, see joined Cases C-54/88, C-91/88 and C-14/89,

Criminal Proceedings against Eleonora Nino and others, [1990] ECR I-3537, para. 10; for the freedom to provide services, see Case C-97/98, Peter Jägerskiöld v. Torolf Gustafsson, [1999] ECR I-7319 para. 42; cf. Abatay and Sahin, ECR I-12301, para. 108.

30 For Article 49 of the TFEU, see Reyners, ECR 631, para. 32; for Article 56 of the

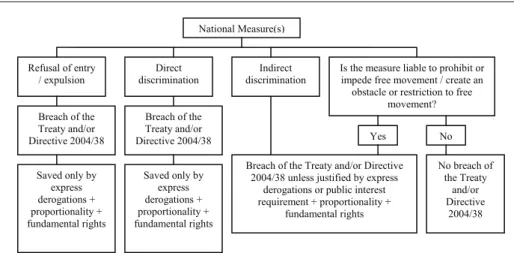

Figure 1: Market Access Approach to Freedom of Establishment and to Provide Services31

Now, in accordance with Figure 1,32 this matter will be addressed into four

parts: refusal of entry and exportation, direct discrimination, indirect discrimination and ‘obstacle’ or ‘restriction’ to free movement.

Refusal of entry or expulsion can only be taken against migrants; hence, they can only be justified by express derogations – namely public policy, public security or public health – provided that the principle of proportionality and fundamental rights have been observed by the state taking the measure.33

Both in the access to and the exercise of the freedoms of establishment and to provide services, Articles 49 and 56 of the TFEU prohibit discrimination on the grounds of nationality.34 Directly discriminatory measures can only be

31 Although with slight changes, this figure is basically taken from Barnard, supra note

16, at 275. With regard to the freedom to provide services, it should be noted that this figure may be affected by Article 16 of the Services Directive, Directive 2006/123/EC, [2006] OJ L 376/36. See Paul Craig and Gráinne De Búrca, EULAW:TEXTS,CASES AND MATERIALS 844 (4th Edition, Oxford University Press, 2008).

32 See Figure 1 supra.

33 For refusal of entry, see Case 41/74, Yvonne van Duyn v. Home Office, [1974] ECR

1337 paras. 22-23; for exportation, see Case C-348/96, Criminal Proceedings against Donatella Calfa, [1999] ECR I-11, para. 20; for the principle of proportionality, see case C-55/94, Reinhard Gebhard v. Consiglio dell'Ordine degli Avvocati e Procuratori di Milano, [1995] ECR I-4165, para. 37; for fundamental rights, see Case C-260/89, Elliniki Radiophonia Tiléorassi AE and Panellinia Omospondia Syllogon Prossopikou v. Dimotiki Etairia Pliroforissis and Sotirios Kouvelas and Nicolaos Avdellas and others, [1991] ECR I-2951, para. 42.

34 Case C-288/89, Stichting Collectieve Antennevoorziening Gouda and others v.

Commissariaat voor de Media, [1991] ECR I-4007, para. 10.

National Measure(s) Direct

discrimination Refusal of entry

/ expulsion Is the measure liable to prohibit or impede free movement / create an obstacle or restriction to free

movement? Breach of the Treaty and/or Directive 2004/38 Saved only by express derogations + proportionality + fundamental rights Breach of the Treaty and/or Directive 2004/38 Saved only by express derogations + proportionality + fundamental rights No Yes No breach of the Treaty and/or Directive 2004/38 Breach of the Treaty and/or Directive

2004/38 unless justified by express derogations or public interest requirement + proportionality +

fundamental rights Indirect

justified by the grounds explicitly mentioned in the TFEU, i.e. exercise of official authority, public policy, public security or public health, as long as they are proportionate and respect fundamental rights.35

An example is the Reyners case, which relates to the freedom of establishment.36 In this case, the Court decided that a Belgian measure

restricting the profession of attorney only to Belgium nationals breached Article 49 of the TFEU. However, this breach may be justified by the official authority exception. Nevertheless, this exception is limited to those activities which involve direct and specific connection with the exercise of official authority.37

In the context of the profession of attorney, nonetheless, it is not possible to invoke such an argument.38

Both in the access to and exercise of the freedoms of establishment and to provide services, measures that are indirectly discriminatory are also prohibited by Articles 49 and 56 of the TFEU.39 Those kinds of measures apply criteria of differentiation other than nationality, but that criteria leads to the same result as discrimination based on nationality.40 In other words, national measures which are “likely to operate mainly to the detriment of nationals of other Member States” entail indirect discrimination on the basis of nationality.41 Nonetheless, such measures may be justified by public interest requirements in addition to the express violations given that the principle of proportionality and fundamental rights are observed.

An example is the Commission v. Italy case which relates to the freedom to provide services.42 In this case, the Italian measure gave free admission to

museums or public monuments to persons who were resident in the same area as that museum or public monument and were aged over 60 or 65. Hence, non-residents fulfilling the age requirement could not gain the same benefit.43

According to the Court, the ‘residence’ criterion produced indirect discrimination on grounds of nationality, since it “is liable to operate mainly to

35 Id., para. 11. 36 Reyners, ECR 631. 37 Id., para. 54. 38 Id., para. 55.

39 Case C-388/01, Commission of the European Communities v. Italian Republic [2003]

ECR I-721 para. 13.

40 Id.

41 Regarding the freedom of establishment, see Case C-346/04, Robert Hans Conijn v.

Finanzamt Hamburg-Nord, [2006] ECR I-6137 para. 25; regarding the freedom to provide services, see Case C-224/97, Erich Ciola v. Land Vorarlberg, [1999] ECR I-2517, para. 14.

42 Commission v. Italy, supra note 39. 43 Id., para. 15.

the detriment of nationals of other Member States.”44 To justify this measure,

Italy relied on “the cost of managing cultural assets” on the one hand, and the “cohesion of the tax system” on the other.45 The Court rejected the reasons put

forward by the Italian Government, since the “aims of a purely economic nature cannot constitute overriding reasons in the general interest justifying a restriction of a fundamental freedom guaranteed by the Treaty.”46 Additionally,

the necessity to preserve the cohesion of the tax system has been acknowledged as an overriding reason in the general interest.47 However, in order to be deemed

a justification, there should be a direct link between any taxation and the application of preferential rates for admission to the museums and public monuments, which was missing in that case.48 In conclusion, the Italian measure

was incompatible with EU law.49

Both in the access to and exercise of the freedoms of establishment and to provide services, measures which are considered to be an ‘obstacle’ or a ‘restriction’ to free movement are contrary to Articles 49 and 56 of the TFEU. However, they may be justified by public interest requirements or express derogations provided that they respect the principle of proportionality and fundamental rights.

Regarding the freedom of establishment, in the Gebhard case, the Court established the ‘obstacle’ or ‘restriction’ approach as follows:

…national measures liable to hinder or make less attractive the exercise of fundamental freedoms guaranteed by the Treaty must fulfill four conditions: they must be applied in a non-discriminatory manner; they must be justified by imperative requirements in the general interest; they must be suitable for securing the attainment of the objective which they pursue; and they must not go beyond what is necessary in order to attain it.50

For now, it is settled that Article 49 of the TFEU requires the elimination of restrictions on the freedom of establishment. These restrictions are “all measures which prohibit, impede or render less attractive the exercise of that

44 Id., para. 14. 45 Id., para. 18. 46 Id., para. 22. 47 Id., para. 23. 48 Id., para. 24. 49 Id., para. 25.

50 Gebhard, ECR 4165, para. 37. (emphasis added); cf. Abatay and Sahin, ECR I-12301, paras. 110-111, 113-115; Tum and Dari, ECR I-7415, para. 47; Soysal and others, ECR I-1031, paras 55-57.

freedom.”51 However, such a measure may be justified where it serves

“overriding requirements relating to the public interest, is suitable for securing the attainment of the objective it pursues and does not go beyond what is necessary in order to attain it.”52

An example of this ‘obstacle’ or ‘restriction’ approach can be found in the

Haim case.53 In this case, Germany required a dentist who was a national of

another Member State to have the necessary linguistic knowledge of that state (Germany) in order to be appointed as a dental practitioner within the social security scheme.54 According to the Court, this requirement amounted to a

restriction on the exercise of the freedom of establishment.55 However, this

requirement may be justified, since “the reliability of a dental practitioner’s communication with his patient and with administrative authorities and professional bodies constitutes an overriding reason of general interest.”56 Nevertheless, this requirement should not go beyond what is necessary. In this respect, there may be patients whose mother tongue is not the national language and there may be need for dental practitioners who can communicate with such patients on their own language.57 In the end, the Member State of establishment may call for the necessary linguistic knowledge for that kind of a profession.58

Regarding the freedom to provide services, in the Säger case, the Court unequivocally declared that Article 56 of the TFEU requires:

the abolition of any restriction even if it applies without distinction to national providers of services and to those of other Member States, when it is liable to prohibit or otherwise impede the activities of a provider of services established in another Member State where he lawfully provides similar service.59

It is, however, possible to justify such measures by imperative reasons relating to the public interest which apply to all persons or undertakings

51 Case C-442/02, Caixa-Bank France v. Ministère de l'Économie, des Finances et de

l'Industrie, [2004] ECR I-8961, para. 11.

52 Caixa-Bank, ECR I-8961, para. 17.

53 Case C-424/97, Salomone Haim v. Kassenzahnärztliche Vereinigung Nordrhein,

[2000] ECR I-5123. 54 Id., para. 50. 55 Id., para. 57. 56 Id., para. 59. 57 Id., para. 60. 58 Id., para. 61.

59 Case C-76/90, Manfred Säger v. Dennemeyer & Co. Ltd, [1991] ECR I-4221, para.

12. (emphasis added); compare with Abatay and Sahin, I-12301, paras. 110-111, 113-115; Tum and Dari, ECR I-7415, para. 47; Soysal and others, ECR I-1031, paras 55-57.

pursuing an activity in the state of destination and where the measures are objectively necessary for the aim they pursue and do not exceed what is necessary to attain those objectives.60

The Säger case is also a fine example of the ‘obstacle’ or ‘restriction’ approach.61 Here, German legislation prohibited a company established in

another Member State from providing a monitoring and renewal service to the holders of patents in Germany with respect to those patents by paying the fees prescribed. According to the same legislation, this activity can only be carried by persons possessing a particular professional qualification, such as that of patent agent.62 The ECJ first determined that the disputed legislation constituted

a restriction on the freedom to provide services.63 The Court then returned to the

question of justification. According to the Court, the German legislation was intended to protect the recipients of the services in question against the harm which they could suffer because of legal advice given to them by unqualified persons, which is a public interest justifying a restriction on the freedom to provide services.64 However, by demanding a specific professional qualification, this measure is disproportionate to the needs of the service recipients.65 In the end, the relevant German legislation was held to be contrary to Article 56 of the TFEU.66

There is one limit for individuals trying to invoke these freedoms: abuse of rights. In this regard, European Union law entitles Member States to take measures “to prevent individuals from improperly or fraudulently taking advantage of provisions of [European Union] law.”67

60 Säger, ECR I-4221. 61 Id. 62 Id., para. 11. 63 Id., para. 14. 64 Id., paras. 16-17. 65 Id., para. 17. 66 Id., para. 21.

67 Regarding the freedom of establishment, see Case C-212/97, Centros Ltd v.

Erhvervsog Selskabsstyrelsen, [1999] ECR I-1459, para. 24; regarding the freedom to provide services, see van Binsbergen, ECR 1299, para. 13; cf. Tum and Dari, ECR I-7415, paras. 65-68.

II. THE FREEDOMS OF ESTABLISHMENT AND TO PROVIDE SERVICES UNDER ASSOCIATION LAW

The time has come to now focus on the freedoms of establishment and to provide services under association law.68 Here, while referring to the case law

of the ECJ and the doctrinal writings, these freedoms can be compared under European Union and association law. This comparison will thereby lead to the exploration of the scope and effects of these freedoms under association law which will indicate the relevant provisions in this regard and then demonstrate the impact of these provisions in European Union law.

A. Relevant Provisions of Association Law

The relevant provisions are Articles 9, 13 and 14 of the AA; Article 41 of the AP also applies.

Article 9 of the AA, which is a rule of non-discrimination, states that: The Contracting Parties recognize that within the scope of this Agreement and without prejudice to any special provisions which may be laid down pursuant to Article 8, any discrimination on grounds of nationality shall be prohibited in accordance with the principle laid down in [Article 18 of the TFEU].

Article 9 of the AA has relevance in this context, since there is no specific rule of non-discrimination regarding the freedoms of establishment and to provide services in association law; thus, this article, in conjunction with other articles, serves as a prohibition of discrimination on grounds of nationality in this regard.69

Articles 13 and 14 of the AA may be deemed as providing a ‘guidance rule.’ These articles articulate that the Contracting Parties agree to be guided by the articles of the TFEU regarding the freedoms of establishment and to provide services for the purpose of abolishing restrictions on these freedoms between themselves.70

68 For a comparison of the provisions relating to the freedom of establishment and to the

freedom to provide services in the AA and AP with the provisions in the Europe Agreements, see Marise Cremona, Movement of Persons, Establishment and Services, ENLARGING THE EUROPEAN UNION:RELATIONS BETWEEN THE EU AND CENTRAL AND

EASTERN EUROPE 200-07 (Marc Maresceau, ed., Longman, 1997).

69 Case C-92/07, Commission of the European Communities v. Kingdom of the

Netherlands, Judgment of 29 April 2010, nyr, para. 75.

70 In this regard, Article 13 of the AA refers to Articles 52 to 56 and Article 58 of the

Treaty Establishing the European Economic Community (“TEEC”) (now Articles 49 to 52 and 54 of the TFEU) and Article 14 of the AA refers to Articles 55, 56 and 58 to 65

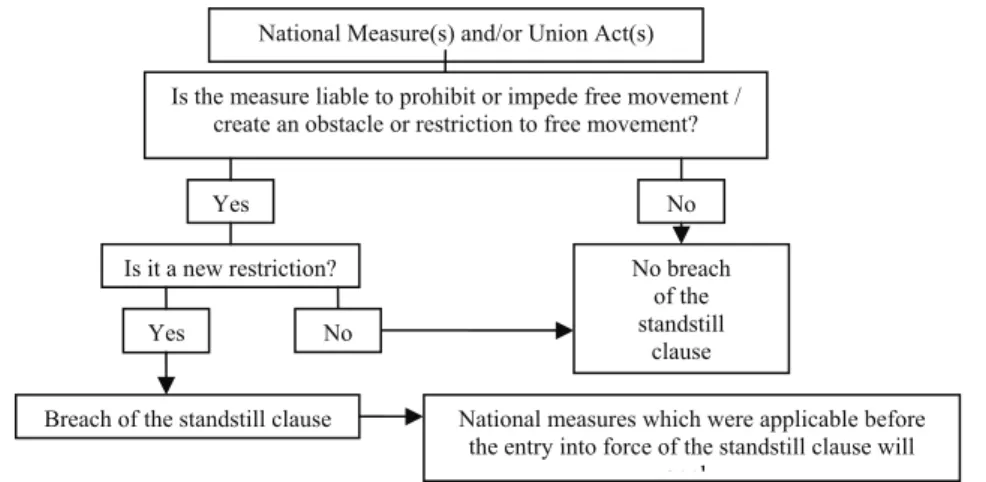

Article 41(1) of the AP, which is a ‘standstill clause,’ declares that “[t]he Contracting Parties shall refrain from introducing between themselves any new restrictions on the freedom of establishment and the freedom to provide services.”71

Article 41(2) of the AP charges the Association Council with the duty of setting the timetable and rules for the progressive abolition of restrictions on these freedoms between the parties. However, there has not yet been any Association Council Decision (“ACD”) on this point.72

To sum up, the relevant provisions regarding the freedoms of establishment and to provide services under European Union and association law differs in two aspects: contrary to Articles 49 and 56 of the TFEU, which lay down a specific non-discrimination rule, there is only a general non-discrimination rule in Article 9 of the AA and in contrast to Articles 49 and 56 of the TFEU which prohibit restrictions on these freedoms, Article 41(1) of the AP forbids only the introduction of new restrictions.

B. Impact upon EU Law

The impact of the provisions relating to the freedoms of establishment and to provide services under European Union law is framed as follows: the direct effect of Article 9 of the AA and Article 41(1) of the AP are verified, then the scope of these provisions are explained. Lastly, their effects in the European Union legal regime are illustrated.

1. Direct effect

Article 9 of the AA and Article 41(1) of the AP are a part of association law. These provisions are set out in the AA and AP which are concluded by,

inter alia, the European Union. Hence, in order to determine whether these

provisions have direct effect, we need to use the direct effect test with regard to international agreements in European Union law. According to the settled case law of the ECJ, a provision of an international agreement is directly effective

of the TEEC (now Articles 51, 52 and 55 to 62 of the TFEU). These articles do not have direct effect. Tum and Dari, ECR I-7415, para. 62; Savas, I-2927, paras. 42-45.

71 This article “appears to be the necessary corollary to [Articles 13 and 14] and

constitutes the indispensable means of achieving the gradual abolition of national obstacles to the freedom of establishment and … to provide services.” See Abatay and

Sahin, ECR 12301, para. 68.

72 According to Staples, therefore, the freedom of establishment and to provide services

in the AA has remained a paper right as far as Turkish nationals are concerned. Helen Staples, THE LEGAL STATUS OF THIRD COUNTRY NATIONALS RESIDENT IN THE

“when, regard being had to its wording and the purpose and nature of the agreement itself, the provision contains a clear and precise obligation which is not subject, in its implementation or effects, to the adoption of any subsequent measure.”73

The direct effect of Article 41(1) of the AP was the question in the Savas case.74 The Court first mentioned the test for direct effect of the provisions of

international agreements and then analyzed whether Article 41(1) of the AP satisfied those criteria.75 According to the ECJ, Article 41(1) of the AP “lays

down, clearly, precisely and unconditionally,76 an unequivocal ‘standstill’ clause, prohibiting the contracting parties from introducing new restrictions on the freedom of establishment as from the date of entry into force of the [AP].”77 Moreover, neither the purpose nor the subject matter of the AA was capable of invalidating the provisions contained therein from being directly effective. The purpose of the AA is “to promote the development of trade and economic relations between the contracting parties” which includes “the progressive abolition of restrictions on freedom of establishment” and to “facilitate the accession of [Turkey] to the [Union] at a later date.”78 From the foregoing, it is

clear that the Article 41(1) of the AP has direct effect.79

Article 9 of the AA, on the other hand, has not yet been subject to the test for direct effect of provisions of international agreements.80 Nonetheless, in the

case of Commission v. Netherlands, the Court found a national measure contrary to the general rule of non-discrimination laid down in Article 9 of the AA.81 It is therefore clear that the Court considers this article to be directly

73 Case 12/86, Meryem Demirel v. Stadt Schwäbisch Gmünd, [1987] ECR 3719, para.

14.

74 Savas, ECR I-2927, para. 36. 75 Id., paras. 39-40.

76 On the contrary, Hailbronner asserts that this provision is conditional, because of its

second paragraph where it empowers the Association Council to take the necessary measures. Kail Hailbronner, IMMIGRATION AND ASYLUM LAW AND POLICY OF THE

EUROPEAN UNION 234 (Kluwer Law International, 2000).

77 Savas, ECR I-2927, para. 46. Besides, the Court relied on three similar standstill

provisions which had been found directly effective: Article 53 of the TFEC, Article 7 of ACD 2/76 and Article 13 of ACD 1/80. According to the Court, like these Articles, Article 41(1) of the AP should also be directly effective. Id., paras 47-50.

78 Id., para. 52. The Court shed light on one more point – although there is imbalance

regarding the obligations between the parties, this does not prevent the provisions of association law from being directly effective. Id., para. 53.

79 Id., para. 54.

80 However, Advocate General (“AG”) Antonio la Pergola has assessed Article 9.

Opinion of the AG, Case C-262/96, Sema Sürül v. Bundesanstalt für Arbeit, [1999] ECR I-2685; Opinion of the AG in Savas, ECR I-2927, paras 16-20.

effective.82 Besides, Article 9 of the AA contains a clear and precise obligation

(prohibition of discrimination on the grounds of nationality)83 which is not

subject, in its implementation or effects, to the adoption of any subsequent measure.84 Furthermore, it is now well established that the wording, purpose

and nature of the AA are not capable of invalidating the provisions contained therein from being directly effective.85

We have established that, like Articles 49 and 56 of the TFEU, Article 41(1) of the AP and Article 9 of the AA have direct effect. Thus, it is time to consider the scope of the freedoms of establishment and to provide services under association law, with the purpose of determining in what types of situations these articles may step into.

2. Scope

The freedoms of establishment and to provide services under association law consist of personal, material and temporal scope. Each will be dealt with in turn.

Personal scope deals with who can benefit from the freedoms of establishment and to provide services under association law. As a preliminary remark, in order to benefit from these freedoms, any natural person has to hold Turkish nationality and undertakings should be established in Turkey.86

82 See also Opinion of the AG, Savas, ECR I-2927, para. 19. Hedemann-Robinson

recognizes that Article 9 of the AA might well have direct effects in conjunction with other legal instruments underpinning the association arrangements, by way of analogy with the Article 18 of the TFEU. See Martin Hedemann-Robinson, An Overview of

Recent Legal Developments at Community Level in Relation to Third Country Nationals within the EU, 38 COMMON MARKET L.REV. 542 (2001). On the other hand, Peers

states that Article 9 of the AA is a potential “wild card” – when it is pleaded, the Court may either declare it nugatory because of the lack of EU Treaty parallels, or it may begin to develop a sui generis interpretation of the clause which reflects the distinct nature of EU-Turkey relations. Steve Peers, Towards Equality: Actual and Potential

Rights of Third-Country Nationals in the European Union, 33 COMMON MARKET L.

REV. 18, 18-19, (1996).

83 Ott finds this wording less precise than the comparable non-discrimination provisions

of other Association Agreements, such as Article 44(3) of the Europe Agreement with Poland or Article 40 of the former Moroccan Cooperation Agreement. Andrea Ott, The

Savas Case – Analogies between Turkish Self-Employed and Workers?, 2 EUROPEAN

JOURNAL OF MIGRATION AND LAW 455 (2000).

84 Compare with Article 10 of ACD 1/80. In this regard, see Case C-171/01,

Wählergruppe ‘Gemeinsam Zajedno/Birlikte Alternative und Grüne GewerkschafterInnen /UG’, [2003] ECR I-4301, paras 58, 59, and 67.

85 See Savas, ECR I-2927, para. 52.

To date, the ECJ has decided some cases which include explanation of the personal scope of these freedoms; however, the case law is not conclusive on this point. Here, besides the clarifications of the Court, the internal market meaning of the personal scope of these freedoms will be used in order to describe them.87

In doing this, the principle of interpretation adopted by the Court is useful. In this regard, an analogy between the case law of the Court regarding Turkish workers and self-employed Turkish persons can be shown.88 Regarding Turkish

workers, the ECJ has consistently concluded from the wording of Article 12 of the AA that the principles enshrined in the articles of the TFEU which relate to the workers “must be extended, so far as possible, to Turkish workers who enjoy the rights conferred by [ACD 1/80].”89 The Court, then, said that

“reference should consequently be made to the interpretation of the concept of worker under [European Union] law for the purposes of determining the scope of the same concept employed in [Article 6(1) of ACD 1/80].”90 Afterwards,

Turkish worker is defined in the same way as a European Union worker.91

Regarding self-employed Turkish persons, the ECJ adverted to the same principle of interpretation – the wording of Articles 13 and 14 of the AA, coupled with the objective of the association, make it clear that the principles enshrined in the articles of the TFEU which relate to the freedoms of establishment and services, “must be extended, so far as possible, to Turkish nationals to eliminate restrictions on the freedom (of establishment and) to provide services between the contracting parties.”92 Therefore, by analogy to the

case law on Turkish workers, the Court will refer to the interpretation of the concepts regarding the personal scope of the freedoms of establishment and to provide services for the purposes of determining the scope of the same concept

87 See Murat Uğur Aksoy, AVRUPA HUKUKU AÇISINDAN TÜRK VATANDAŞLARINA

UYGULANAN VIZE ALMA MECBURIYETININ DEĞERLENDIRILMESI RAPORU [THE REPORT ABOUT THE ASSESSMENT OF THE VISA REQUIREMENT APPLIED TO THE TURKISH NATIONALS WITH RESPECT TO THE EUROPEAN LAW] 23-24 (İktisadi Kalkınma Vakfı

Yayınları, 2008); Klaus Dienelt, TÜRK VATANDAŞLARININ AVRUPA’YA SEYAHAT

ÖZGÜRLÜĞÜNÜN KISITLANMASI [THE RESTRICTIONS ON THE FREEDOM OF TRAVEL OF TURKISH NATIONALS TO EUROPE] 9 (Klaus Dienelt et al, ed., İktisadi Kalkınma Vakfı Yayınları, 2008).

88 The Court also drew such an analogy. See Savas, ECR I-2927, para. 63.

89 Case C-1/97, Mehmet Birden v. Stadtgemeinde Bremen, [1998] ECR I-7747, para.

23. Article 12 of the AA articulates that the Contracting Parties agree to be guided by the articles of the TFEU about the freedom of movement for workers for the purpose of progressively securing that freedom between them.

90 Id., para. 24. 91 Id., paras. 25-32.

employed under association law. To give an example, in the Abatay and Sahin case, the Court acknowledged that the Turkish truck drivers employed by a Turkish undertaking that lawfully provides services in a Member State are within the personal scope of the freedom to provide services, as it has been also decided in the Clean Car case relating to the internal market that “the paid employees of the provider of services are indispensable to enable him to provide his services.”93

The freedom of establishment, with regards to individuals, requires that person to be self-employed. Any person who pursues an economic activity is regarded as self-employed where he/she works outside any relationship of subordination, under his/her own responsibility and in return for remuneration paid directly to him/her directly and fully.94 It necessitates, regarding

undertakings, the actual establishment of that undertaking to the host Member State and the pursuit of genuine economic activity there.95

The freedom to provide services can be considered in three types of situations according to where service providers move, where service recipients move and where neither provider nor recipient but the service moves.96 A

service provider is a self-employed natural or legal person that performs a service on a temporary basis.97 Service recipients benefit also from the freedom to provide services, since they are a ‘necessary corollary’ to this freedom.98 In this regard, tourists, persons receiving medical treatment and persons travelling for the purpose of (private) education or business can be deemed to be service recipients.99 Furthermore, the service may move in itself by telephone, Internet or cable.100

The freedom to provide services also shows a special characteristic regarding undertakings. In this regard, not only the undertakings established in

93 Abatay and Sahin, ECR I-12301, para. 106; see Clean Car, ECR I-1521, paras. 19-21. 94 Cf Jany and Others, ECR I-8615, para. 71.

95 Cf. Cadbury, ECR I-7995, para. 54.

96 See Barnard, supra note 16, at 355-58; Sanem Baykal, TÜRKIYE-AT ORTAKLIK

HUKUKU VE ATAD KARARLARI ÇERÇEVESINDE KATMA PROTOKOL’ÜN 41/1.

MADDESINDE DÜZENLENEN STANDSTILL HÜKMÜNÜN KAPSAMI VE YORUMU,İSTANBUL

[THE SCOPE AND INTERPRETATION OF THE STANDSTILL PROVISION REGULATED IN THE

ARTICLE 41/1 OF THE ADDITIONAL PROTOCOL IN THE FRAMEWORK OF TURKEY-EC

ASSOCIATION LAW AND THE RULINGS OF THE ECJ] 31 (İktisadi Kalkınma Vakfı

Yayınları, 2008); Aksoy, supra note 87, at 23. See also Dienelt, supra note 87, at 8, 11-12.

97 Article 57 of the TFEU.

98 Cf. Luisi and Carbone, ECR 377, para. 10.

99 Cf. id., para. 10 and Max Wirth, ECR I-6447, para. 17. 100 See Barnard, supra note 16, at 357-58.

Turkey, but also the workers of that undertaking may invoke the relevant provisions, since they are indispensable to the service provider (undertaking) to enable the provision of services.101

To sum up, the personal scope of establishment and services under association law has been and should always be interpreted in the same way as their counterparts under European Union law.

The material scope consists of two aspects: subject matter and internal situation.

The subject matter concerns the areas which are covered by freedom of establishment and to provide services in association law. Here, firstly, will be addressed what constitutes services and secondly, what are the rights covered by these freedoms. In these explanations, the case law of the Court regarding the Article 41(1) of the AP provides sufficient basis. Moreover, the case law of the Court concerning the internal market freedoms will be helpful, since these principles will be transposed, as far as possible, to association law.102 Besides, the writings in the doctrine are helpful sources.

Firstly, the ones that constitute services in EU law are also considered to be services in association law. In this regard, the activities of craftsmen, professions and activities of an industrial or a commercial character – in addition to the tourism, medical, financial, business, educational and sporting activities – constitute services.103 Moreover, in contrast to the situation in EU law,104 the transport sector is also within the scope of services in association

law. This was at issue in the Abatay and Sahin case.105 In this case, the Dutch

Government argued that the transport sector is not covered by Article 41(1) of the AP. In the view of the government, there was a provision in association law dealing with transport separately and also in EU law this sector is excluded from the provision of services.106 However, the ECJ came to the opposite

conclusion. According to the Court, the position of transport in European Union

101 Abatay and Sahin, ECR I-12301, paras 105-106; see Opinion of the AG in Abatay and Sahin, ECR I-12301, para. 200; see also Soysal and others, ECR I-1031, para. 46;

compare with Clean Car, ECR I-2521, paras 19-21.

102 Abatay and Sahin, ECR I-12301, para. 112. For the interpretation principle adopted

by the Court regarding association law, see Section IIB supra.

103 Article 57 of the TFEU; see Luisi and Carbone, ECR 377, para. 10; Bond, ECR

2085, para. 16; Deliège, ECR I-2549, para. 56.

104 Article 58 of the TFEU.

105 See Abatay and Sahin, ECR I-12301.

106 Abatay and Sahin, ECR I-12301, para. 92. A similar conclusion as drawn by the AG. See Opinion of the AG, Abatay and Sahin, ECR I-12301, para. 134.

law is different from association law.107 The transport provisions in association

law, Article 15 of the AA and Article 42 of the AP, show that the extension of Treaty provisions to transport to Turkey is merely optional and until now it has not been achieved.108 As a result, “unlike intra-[EU] transport, transport services

in the context of the Association cannot be removed from the ambit of the general rules applicable to the provision of services.”109

Secondly, regarding the rights covered by the freedoms of establishment and to provide services under association law, some preliminary remarks come first, followed by the list of the rights that these freedoms cover and do not cover, in turn.

First of all, there is a marked difference between the provisions relating to the freedoms of establishment and to provide services under European Union and association law. Articles 49 and 56 of the TFEU confer substantial rights on their beneficiaries. These provisions, therefore, cover not only the rights of departure, entry, residence and protection against expulsion, but also the rights related to the access to and exercise of these freedoms. Article 9 of the AA in conjunction with (Articles 13 and 14 of the AA and/or) Article 41(1) of the AP and Article 41(1) of the AP alone, on the other hand, do not cover any substantial rights with regard to these freedoms. Whereas Article 9 of the AA, which is considered to be an instrumental rather than substantive rule, applies only to situations that are within the scope of the association law (which does not cover substantial rights regarding these freedoms), Article 41(1) of the AP (the standstill clause) is regarded as a quasiprocedural rule in contrast to substantial rules such as Articles 49 and 56 of the TFEU.110

Consequently, the following rights are not covered by Article 9 of the AA and/or Article 41(1) of the AP. To begin with, none of them compromise any substantial rights regarding departure, entry, access to and exercise of self-employment, access to and exercise in the market for services or residence.111 In

addition to this, Turkish nationals are not entitled to move freely throughout the

107 Id., para. 95. 108 Id., paras. 96-98. 109 Id., para. 99.

110 Regarding Article 9 of the AA, see Opinion of the AG, Savas, ECR I-2927, para. 18;

regarding Article 41(1) of the AP, see Tum and Dari, ECR I-7415, para. 55.

111 Savas, ECR I-2927, paras. 64-65; Abatay and Sahin, ECR I-12301, para. 62; Tum and Dari, ECR I-7415, paras 54, 52; see Robin C. A. White, WORKERS,

ESTABLISHMENT, AND SERVICES IN THE EUROPEAN UNION 220 (Oxford University

European Union, but benefit only from certain rights in a single Member State.112 Moreover, there is no right to family re-unification.113

Now come rights covered by the freedoms of establishment and to provide services under association law. Here is another distinction between regular Turkish nationals and others. According to the ECJ, Turkish nationals “may claim certain rights under [European Union] law in relation to holding employment or exercising self-employed activity, and, correlatively, in relation to residence, only in so far as his position in the Member State concerned is regular.”114 Moreover, in the doctrine, there are authors who depend on this

distinction between Turkish nationals who are in a regular position and others who are not.115

Regular Turkish nationals who are within the personal scope of the freedoms of establishment and to provide services will have a right of continued residence and a guarantee against expulsion like EU citizens and Turkish workers enjoy.116 In addition, given that such Turkish nationals will fall within

the scope of association law, they may invoke the instrumental rule of

112 Savas, ECR I-2927, para. 59; see also Abatay and Sahin, ECR I-12301, para. 64;

compare with Hacı Can and Çınar Özen, TÜRKIYE-AVRUPA TOPLULUĞU ORTAKLIK

HUKUKU [TURKISH-EUROPEAN UNION ASSOCIATION LAW] 209 (Ankara, Gazi Kitabevi,

2005).

113 See Nicola Rogers and Rick Scannel, FREE MOVEMENT OF PERSONS IN THE

ENLARGED EUROPEAN UNION 372 (London, Sweet & Maxwell, 2005).

114 Savas, ECR I-2927, para. 65. The AG in his Opinion refers to the “lawfulness of the

position” which seems to imply “being legally present at the territory of a Member State.” Opinion of the AG, Savas, ECR I-2927, para. 20.

115 See Rogers and Scannel, supra note 113, at 377; Peers, supra note 82, at 39-40, 47;

Eleanor Sharpston, Different but (Almost) Equal-The Development of Free Movement

Rights under EU Association, Co-Operation and Accession Agreements, A TRUE

EUROPEAN: ESSAYS FOR JUDGE DAVID EDWARD 242 (Mark Hoskins and William Robinson, eds., Hart Publishing, 2004); Tolga Candan, ATAD’ın Son Kararları Işığında

Ortaklık İlişkisinde Yerleşme Hakkı ve Serbest Dolaşım, AVRUPA BIRLIĞI’NIN GÜNCEL

SORUNLARI VE GELIŞMELER [THE RIGHT OF ESTABLISHMENT AND FREE MOVEMENT UNDER THE ASSOCIATION RELATIONSHIP IN THE LIGHT OF THE LATEST RULINGS OF THE

ECJ]353 (Belgin Akçay et. al., eds., Seçkin Yayıncılık, 2008).

116 See Savas, ECR I-2927, para. 65; Rogers and Scannel, supra note 113, at 377; Peers, supra note 82, at 39-40, 47. Besides substantive guarantees, the guarantee against

expulsion includes procedural ones. See Case C-136/03, Georg Dörr v. Sicherheitsdirektion für das Bundesland Kärnten and Ibrahim Ünal v. Sicherheitsdirektion für das Bundesland Vorarlberg, [2005] ECR I-4759, para. 69. Whether the provisions of Directive 2004/38, which relate to expulsion, will be applicable to the Turkish nationals has not yet been answered. See Case C-349/06, Murat Polat v. Stadt Rüsselsheim, [2007] ECR I-8167, paras. 23-27.

discrimination on the grounds of nationality laid down in Article 9 of the AA.117

Moreover, they may rely on the standstill clause of Article 41(1) of the AP, just as irregular Turkish nationals may.

Irregular Turkish nationals who are within the personal scope of the freedoms of establishment and to provide services, who alternatively may rely on the standstill clause against the introduction of new restrictions with regard to:

– first admission (as a corollary to the freedoms of establishment and to provide services (including all the substantive and/or procedural conditions)),118

– freedom of establishment (including access and exercise),119

– freedom to provide services (including access and exercise),120

– residence (as a corollary to the freedom of establishment and to provide services),121

– family re-unification (as a complementary of the freedom of establishment and to provide services),122

117 See Opinion of the AG, Savas, ECR I-2927, paras. 18-20; Commission v. Netherlands, ECR C-92/07, para. 75.

118 Tum and Dari, ECR I-7415, paras. 55, 58, 60-61, 63, and 69; for the contrary view, see Opinion of the AG, Tum and Dari, ECR I-7415, paras 52, 59 and 61; cf. Case

C-235/99, The Queen v. Secretary of State for the Home Department, ex parte Eleanora Ivanova Kondova, [2001] ECR I-5421, para. 54; Case C-63/99, The Queen v. Secretary of State for the Home Department, ex parte Wieslaw Gloszczuk and Elzbieta Gloszczuk, [2001] ECR I-6369, para. 51; Case C-257/99, The Queen v. Secretary of State for the Home Department, ex parte Julius Barkoci and Marcel Malik, [2001] ECR I-6557, para. 54. For analysis advocating that first admission is within the scope of the standstill clause, even before the Tum and Dari case, see Ott, supra note 83, at 457 and Christian Calliess, The Immigration Policy of the European Union -- Paving the Way to

Fortress Europe?, INSTITUT FÜR VÖLKERRECHT DER UNIVERSITÄT GÖTTINGEN,

Abteilung Europarecht - Göttinger Online-Beiträge zum Europarecht, No. 1, 2004, 12.

119 Savas, ECR I-2927, para. 65; Abatay and Sahin, ECR I-12301, para. 65; Tum and Dari, ECR I-1031, para. 49.

120 Abatay and Sahin, ECR 12301, paras 67, 111.

121 Savas, ECR I-2927, para. 65; Abatay and Sahin, ECR I-12301, para. 65; Tum and Dari, ECR I-7415, para. 49.

122 As Rogers and Scannel correctly indicate, the ECJ refers to the internal market case

law when it deals with association law; family unity is fundamental to TFEU provisions so Article 41(1) of the AP extends also to the right of family re-unification. Rogers and Scannel, supra note 113, at 372.

– expulsion (since there will be no access or exercise of the freedoms in case of expulsion).123

This list points out, therefore, that the areas covered by Article 41(1) of the AP match with Articles 49 and 56 of the TFEU. However, whereas Article 41(1) of the AP, as a quasiprocedural rule, precludes the introduction of new restrictions, Articles 49 and 56 of the TFEU, as substantive rules, substitute for the conflicting rules with regard to these areas.

Situations that are wholly internal to a Member State are outside of the scope of European Union law. Therefore, there should at least be one factor connecting an activity to any situations envisaged by EU law. For example, in the Abatay and Sahin case, the Court ruled that “the right freely to provide services may be relied on by a provider as against the State in which he is established, those services must then be provided for persons established in another Member State.”124 Thus, a German transport company cannot rely on Article 41(1) of the AP where the recipient of the services is established also in Germany, since there is no factor connecting its activity to European Union law.125

Temporal scope relates to the question of when Member States have been precluded from discriminating on the grounds of nationality in the areas protected by Article 9, of the AA on the one hand, and prevented from introducing new restrictions on the areas covered by the standstill clause on the other hand. Article 9 of the AA should be recognized to have direct effect from the date of the entry into force of the AA, which was 1 January 1964. Article 41(1) of the AP precludes Member States from adopting new restrictive measures from the date of the entry into force of the AP in that Member State.126 Consequently, this is 1 January 1973 for the original six Member States

(Germany, France, Italy, Netherlands, Belgium, and Luxembourg) and the states of first enlargement (United Kingdom, Ireland, and Denmark). For other states, the effective date of their membership in the EU has to be checked.

Until now, we have addressed the situations that are within the scope (personal, material and temporal scope) of the freedoms of establishment and to provide services under association law. It is now convenient to move on to discover the effects of those articles about these freedoms where a situation is within their sphere of application.

123 See Rogers and Scannel, supra note 113, at 377; Peers, supra note 82, at 47. 124 Abatay and Sahin, ECR I-12301, para. 107.

125 Id., para. 108.

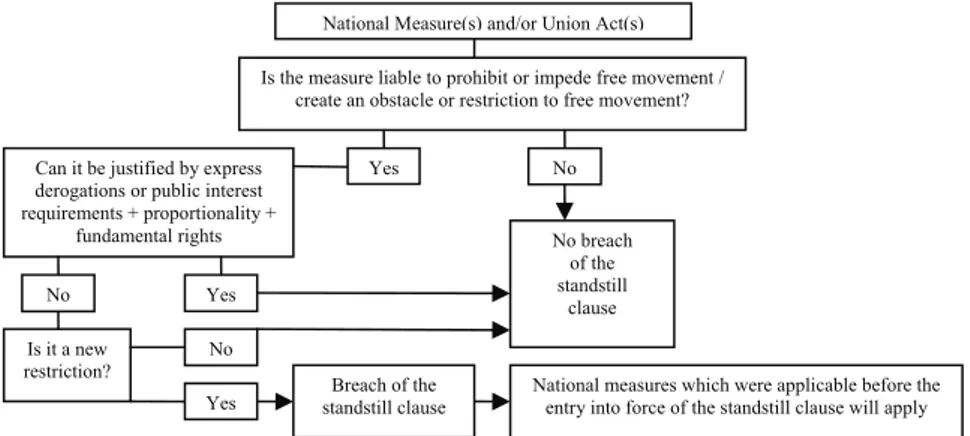

3. Effects

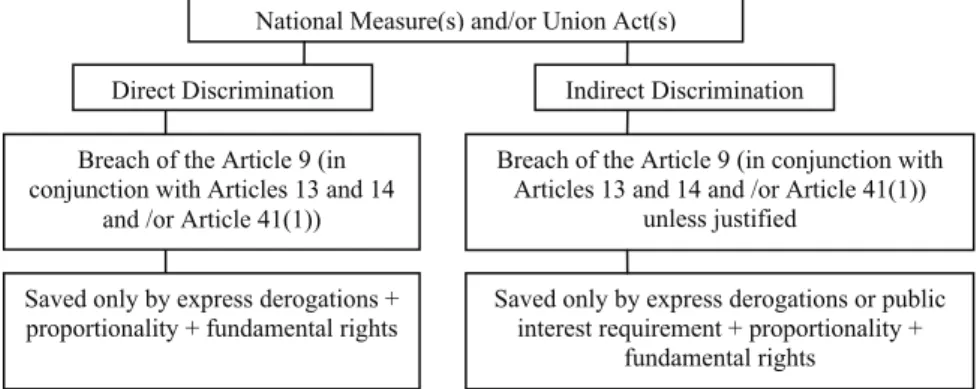

Both Article 9 of the AA (in conjunction with Articles 13 and 14 of the AA and/or Article 41(1) of the AP) and the Article 41(1) of the AP alone prevent the application of (unjustified) conflicting relevant measures.127 The topic has

two aspects: the first one relates to the restriction and justification, while the second one concerns the limits to the enjoyment of these freedoms.

Article 9 of the AA (in conjunction with Articles 13 and 14 of the AA and/or Article 41(1) of the AP) prohibits discrimination on grounds of nationality within its scope of application. In addition to this, Article 41(1) of the AP, which is a standstill clause, prohibits new restrictions on the freedoms of establishment and to provide services.

This matter is covered in three headings which correspond to the scheme followed regarding these freedoms under EU law: refusal of entry and exportation, direct and indirect discrimination and ‘new restriction’ to the freedoms.

Contrary to the situation in EU law (where refusal of entry or expulsion are in principle prohibited),128 this subject has to be divided into two under association law: refusal of entry and expulsion. Regarding the right of entry, Turkish nationals can only invoke Article 41(1) of the AP which will prevent the introduction of new restrictions in this regard.129 For the protection against expulsion, while regular Turkish nationals can depend on Article 9 of the AA along with Article 41(1) of the AP, irregular Turkish nationals can only rely on the latter.130

Article 9 of the AA, in conjunction with Articles 13 and 14 of the AA and/or Article 41(1) of the AP, prohibits discrimination on grounds of nationality regarding the freedoms of establishment and to provide services, as long as the position of a Turkish national in a Member State is regular.

Up to now, there has been only one case dealing with Article 9 of the AA; however, the Court did not elaborate on the effects of this article in that case.131

In that case, Turkish nationals who have a right of residence in the Netherlands pay higher fees than EU nationals regarding the issue or the extension of the

127 For discussion on Article 41(1) of the AP, see Abatay and Sahin, ECR I-12301, para.

59. Rogers and Scannel reveal that the benefit of Article 41(1) of the AP extends to both substantive and procedural provisions, as well as any policies or practices in existence at the relevant time. Rogers and Scannel, supra note 113, at 358.

128 See Section IIC supra.

129 Tum and Dari, ECR I-7415, paras. 55, 58, 60-61, 63, 69.

130 See Rogers and Scannel, supra note 113, at 377; Peers, supra note 82, at 39-40, 47. 131 See Commission v. Netherlands, C-92/07, para. 75.