Full Terms & Conditions of access and use can be found at

https://www.tandfonline.com/action/journalInformation?journalCode=rlcc20

Language, Culture and Curriculum

ISSN: 0790-8318 (Print) 1747-7573 (Online) Journal homepage: https://www.tandfonline.com/loi/rlcc20

Isolated form-focused instruction and integrated

form-focused instruction in primary school English

classrooms in Turkey

Zennure Elgün-Gündüz , Sumru Akcan & Yasemin Bayyurt

To cite this article: Zennure Elgün-Gündüz , Sumru Akcan & Yasemin Bayyurt (2012) Isolated form-focused instruction and integrated form-focused instruction in primary school English classrooms in Turkey, Language, Culture and Curriculum, 25:2, 157-171, DOI: 10.1080/07908318.2012.683008

To link to this article: https://doi.org/10.1080/07908318.2012.683008

Published online: 30 May 2012.

Submit your article to this journal

Article views: 832

View related articles

Isolated form-focused instruction and integrated form-focused

instruction in primary school English classrooms in Turkey

Zennure Elgu¨n-Gu¨ndu¨za∗, Sumru Akcanband Yasemin Bayyurtb

a

Department of English Language and Literature, Ardahan University, Ardahan, Turkey; b

Department of Foreign Language Education, Bog˘azic¸i University, Istanbul, Turkey (Received 11 January 2011; final version received 1 April 2012)

Content-based language instruction and form-focused instruction (FFI) have been investigated extensively in the context of English as a second language. However, there has not been much research concerning FFI in the context of English as a foreign language. The study described here explores the effect of integrated and isolated FFI on the vocabulary, grammar, and writing development of foreign language learners in two separate classes at the primary level in Turkey. It also investigates students’ attitudes towards integrated and isolated FFI. Findings suggest that the students receiving integrated FFI performed better than students receiving isolated FFI in all measures. In addition, the students expressed a preference for integrated FFI.

Keywords: content-based instruction; form-focused instruction; grammar; isolated form-focused instruction; integrated form-focused instruction; teaching methods

It is claimed that language instruction organised around curricular content provides optimal conditions for second language (L2) learning because it enables learners to improve their subject matter knowledge while improving their language skills (Brinton, Snow, & Wesche, 1989; Crandall, 1987; Met, 1991; Mohan, 1986). Much of the research in the field of second language learning has been conducted in immersion programmes in Canada and the USA, and most of them have been conducted in settings where English is taught as a second language. Some previous research, however, has examined content-and language-integrated learning (CLIL) (e.g. Dafouz, Nu´n´ez, & Sancho, 2007; Mehisto & Asser, 2007). Most of the research on CLIL and content-based instruction (CBI) has been descriptive and most has compared CBI with grammar-focused instruction. However, CBI has not been the subject of thorough research in settings where English is taught as a foreign language (EFL). The quasi-experimental study presented here examines two distinct instructional methods employing CBI in EFL at the primary level in Turkey. It explores the effect of isolated and integrated form-focused instruction (FFI), particularly in terms of vocabulary, grammar, and writing. It also investigates students’ attitudes concerning their instruction. This study sought to answer the following questions:

ISSN 0790-8318 print/ISSN 1747-7573 online #2012 Taylor & Francis

http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/07908318.2012.683008 http://www.tandfonline.com

∗Corresponding author. Email: zennureelgun@yahoo.com

. Are there any differences between a group of sixth-grade students after isolated FFI

and another group of sixth-grade students after integrated FFI in terms of second language vocabulary and grammar development in an EFL context?

. Are there any differences between two such groups of sixth-grade students in terms of

second language writing development in an EFL context?

. What are sixth-grade students’ attitudes towards isolated FFI after receiving isolated

FFI in second language in an EFL context?

. What are sixth-grade students’ attitudes towards integrated FFI after receiving

inte-grated FFI in second language in an EFL context? Background

Content-based language instruction

CBI is based on the principle that language learning occurs when learners produce and respond to language in meaningful tasks that are focused on course content. The content for CBI is derived primarily from the school’s curriculum, from courses such as mathematics, history, and science, and only secondarily from the language taught (Stryker & Leaver, 1997). CBI does not focus on language separately from content and does not postpone content instruction until the learners have mastered certain language forms. When content and language are inte-grated, learners improve their content knowledge and their language skills simultaneously (Wesche & Skehan, 2002). The duality of their learning helps them to develop cognitive aca-demic language proficiency (Cummins, 1980) and thus to adapt to an acaaca-demic programme or a workplace conducted in the target language (Cantoni-Harvey, 1987).

In order to learn and use content, the students may be involved in communicative tasks, but unlike task-based instruction (TBI), the focus remains on the content as well as the correct use of language. TBI makes use of tasks such as visiting a doctor and reading a bus schedule, the basic purpose of which is to develop students’ interpersonal communi-cation skills (Cummins, 1980). In TBI, the focus is on whether a task is achieved or not and not on the content or the language forms used.

A review of the literature on content-based language programmes indicates that meaning-centred instruction offers a number of advantages in foreign language learning, such as content knowledge, fluency in language use, academic skills, and higher order thinking skills such as synthesising and analysing (Alptekin, Erc¸etin, & Bayyurt, 2007; Bayyurt & Alptekin, 2000; Brinton et al., 1989; Chapple & Curtis, 2000; Crandall, 1987; Flowerdew, 1993; Genesee, 1994; Grabe & Stoller, 1997; Kasper, 1995, 1997; Met, 1991; Mohan, 1986; Yalc¸ın, 2007). Studies conducted mostly in French immersion programmes document the improved fluency and confidence of immersion-taught students. However, some such studies have also revealed weaknesses in accuracy and grammatical, lexical, and sociolinguistic development (Harley, Cummins, Swain, & Allen, 1990; Lyster, 1987; Spada & Lightbown, 2008). Therefore, it is argued that learners ought to be provided not only with subject matter knowledge but also with language forms that enhance the com-munication of content (Swain, 1985; Swain & Lapkin, 1989). Researchers in the field of second language learning have begun to formulate the features of content-based language classrooms with the dual focus of language and content (Netten, 1991). Thus, the role of FFI in foreign language learning has been adapted to a content-focused environment. Form-focused instruction

FFI means, in broad terms, drawing the learners’ attention to certain features in the target language. Reviews of empirical studies about the role of FFI in second language learning

(e.g. Doughty & Williams, 1998; Ellis, 2001; Larsen Freeman & Long, 1991; Lightbown, 2000; Norris & Ortega, 2000; Spada, 1997) suggest that FFI can help second language lear-ners in communicative and content-based classrooms to use the second language fluently and accurately. Responding to the findings of research conducted in classrooms with a focus only on content, advocates of CBI now recognise the importance of planning lessons with both content and linguistic objectives (Lyster, 1998; Pica, 2002). The question is no longer whether students should be provided with instruction about linguistic features, but how and when such instruction is best delivered in content-based language classrooms. Spada and Lightbown (2008) distinguished between isolated and integrated FFI to address the questions of how and when. Both aim at drawing the learners’ attention to language fea-tures and both incorporate content-based and communicative activities; the difference is all about the how and the when.

Isolated FFI

In isolated FFI, language forms can be taught, ‘in preparation for a communicative activity or after an activity in which students have experienced difficulty with a particular language feature’ (Spada & Lightbown, 2008, p. 8). This is different from grammar-focused language instruction which involves teaching and learning language forms without a context for com-munication and which is generally organised by a syllabus of sequential language struc-tures. Isolated FFI is clearly related to content-based or communicative activities. Integrated FFI

In integrated FFI, the learners’ attention is drawn to language forms during communicative or content-based instruction by way of feedback or brief explanations. Learners might be cued to use specific language forms in communicative activities based on subject matter or given help through corrective feedback. Through cues and feedback, teachers help lear-ners to see the relationship between language forms and their functions, with minimal inter-ruption of meaningful interaction.

The study The context

Subjects in this study were sixth-grade students in two private primary schools. Both schools offered 10 h of English lessons per week. In both schools, English teachers employed content-based activities in their lessons. However, the teacher in one school used isolated FFI and the teacher in the other school used integrated FFI.

The integration of language instruction and subject matter instruction within a commu-nicative setting is basic to CBI. In practice, however, a number of different CBI approaches accommodate different programme objectives, populations, and facilities (Snow, 1991). In a theme-based model, selected themes or topics provide the content on which learning activities are based (Snow, 1991). Examination of the course materials in the two schools revealed that they used this theme-based CBI model. Instructional units in both schools were based on themes such as friendship, shopping, festivals, food, traditions, environmental problems, and so on. These themes were related to what the students were studying in their other courses. During observations, in fact, the researcher often witnessed the students saying something like ‘Oh, we’ve already learnt this in science’ or some other subject. While the two schools were similar in using a theme-based model of CBI, they dif-fered in terms of how and when the teachers introduced new grammatical forms. In the

‘integrated’ classroom, the students encountered new grammatical forms through theme-based activities. In the ‘isolated’ classroom, they learned about new forms through isolated instruction taking place before or after theme-based activities.

Isolated FFI in a sixth-grade English class

In the school implementing isolated FFI, the researcher made observations during the language lessons for 2 h a week for 8 months – 64 h altogether.

Materials used in the isolated FFI classroom

In this school, the basic resources were composed of a course book for students called Enterprise (2006), which contained 15 units, an accompanying workbook, a grammar book, and some tests and worksheets provided by the teachers.

The workbook contained many exercises related to grammatical forms and to the content of the course book. The students were expected to fill in the blanks and complete the discrete-point tests that focused on grammar and new vocabulary. The exercises and activities in the workbook were not entirely isolated from the content of the unit; they usually referred in some way to the content of the unit.

The grammar book, on the other hand, was entirely grammar focused. Instruction addressed the grammar points introduced in the course book and the exercises required the students to use the target forms repetitively in de-contextualised sentences.

The flow of the language classes in the isolated FFI classroom

At the beginning of a new unit in the course book, the teacher usually read aloud and asked the meaning of certain words in the text. She also drew attention to certain language forms used in the text. Then, she introduced the grammatical form to be studied in the unit. She explained the relationship between the form and its function and clarified the rules about its use. After this period of isolated and explicit instruction, the students were assigned activi-ties in the course book and workbook. Typically, these exercises focused on the new form and new vocabulary related to the content of the unit. The exercises included fill-in-the-gaps, word order rearrangement, error correction, discrete-point items, and sentence com-pletions. So far, this was isolated FFI.

In the second phase of the typical lesson, the students were required to engage in content-based activities. This time, the focus was not specifically on the correct use of certain grammatical forms, but on the content or theme of communicative activities. These were composed of tasks such as preparing a short dialogue and then acting it out, playing language games such as finding a secret word, writing an essay or short story, and singing a song. The tasks required the students to refer to the content or theme of a unit in the course book. The focus of the lesson was on the content of the activities, not on the accomplishment of the task itself. The typical activities were not grammar focused, and the teacher usually refrained from correcting the students’ errors during the activities. However, the teacher did demonstrate the correct way of forming a sentence or pronouncing a word after the students had finished the content-focused activities.

Integrated FFI in a sixth-grade English class

In the school implementing integrated FFI, the researcher also made observations during the language lessons for 2 h a week for 8 months. There, too, certain salient patterns emerged.

Materials used in the integrated FFI classroom

The basic resources consisted of a course book called Visions (2004), a related activity book, some extra reading texts, and worksheets provided by the teacher. The themes of the units included: ‘cultures and traditions, technology, subways, holidays, environmental problems, religious fests, mathematical operations, literary works’, and so on.

Sections of the course book that conveyed knowledge about the content of the unit were followed in each unit by a reading text. This was usually followed by comprehen-sion questions requiring both ‘right-there’ answers and answers based on inference. The activities in the course book invited the students to relate the content of the chapter to other content areas such as social studies, mathematics, and music. At the end of each unit, there was an ‘apply and expand’ section, which required the students to produce projects by relating what they had read in the course book to personal experience or prior knowledge.

The activity book paralleled the course book. It contained exercises requiring the stu-dents to use their knowledge of vocabulary, elements of literature, and certain grammar points encountered in the course book.

The flow of the language classes in the integrated FFI classroom

A typical lesson started with questions about the previous lesson, which the students tried to answer in English. Then, the teacher elucidated the topic of the day, asking questions and eliciting answers to engage the students in the theme of the unit. After this warm-up activity, the teacher and the students usually read aloud from the course book. The teacher frequently stopped the reading to ask questions or explain the meaning of unfamiliar words in English. In addition to reading comprehension questions, the teacher asked questions that prompted the students to relate the new topic to their experiences in Turkey or to knowledge they had acquired in other courses, thus providing them with topics for communication. During this process, the focus was on content related to other subjects the students were studying. However, the teacher also tried to make the students aware of the language points selected for emphasis in the unit. To accomplish this, she rephrased the students’ answers using the new language forms. In addition, she corrected the students’ errors, particularly about a new grammar point, so that the students experienced new language forms gradually and implicitly.

Besides reading comprehension and discussion, the typical lesson included writing in pairs or small groups, creating a story all together as a class, dramatising a story, listening to songs, singing songs, or playing language games. These activities were all content oriented. However, they also incorporated specific language forms and required the students to use target language forms in order to reach a content-based objective.

After the lesson, the students were usually given assignments to produce an essay, story, fable, or poem related to the content of a unit or perhaps to a genre featured in the unit. To fulfil these assignments, the students had to focus not only on the content of the unit but also on the language forms targeted in the unit.

Participants

The participants comprised 120 students of English in sixth-grade classes in two private primary schools in Turkey. They had been assigned randomly to their class groups. Fifty were enrolled in a school implementing isolated FFI and 70 in a school implementing inte-grated FFI. Their native language was Turkish. Their ages ranged from 11 to 12 years. All

had been learning English since first grade. There was no experimental or control group. Instead, the study took the form of a case study.

Data collection instruments

At the beginning of the study, the researcher met with the teachers to learn about their instructional techniques and the syllabi of their courses. The researcher made observations during the language lessons in each school for 2 h a week. The observations enabled the researcher to form a clear picture of language teaching methods in the various classrooms, the ways in which the methods shaped the students’ language learning, and the attitudes displayed by the students towards learning. The students did not know that they were par-ticipants in a research study.

At the beginning of the first semester of the 2007 – 2008 academic year, the key English test (KET) was administered as a pre-test. Before the pre-test, the researcher made obser-vations for 2 h in each school. Eight months later, at the beginning of June, the students took a second KET. KET is a first-level Cambridge ESOL (English for Speakers of Other Languages) test at level A2 of the Council of Europe’s Common European Framework of Reference for Languages. It is designed to assess the reading, writing, listening, and speaking proficiency of young learners. Grammar knowledge can be assessed as a sub-skill using this test, since sufficient knowledge of grammar is needed to respond correctly to the test items. The test comprised 55 questions and 10 matching, 25 multiple-choice, and 20 fill-in-the-blank items. It also included a very brief writing item that asked the students to write an answer to a postcard. The maximum possible score for each test was 100. The listening and speaking parts of the KET were not included in this study.

The other data collection instruments were essays. Prior to the first essay, the researcher conducted 32 h of observation in each school. The second essay was administered 4 months after the first. The topics of the essays were not the same in the two schools because they were chosen from topics the students had studied throughout the year. The essays were scored by two experts using the same rubric (adapted from Reid, 1993). The maximum possible score was 100. Inter-rater reliability coefficients for the two sets of essays were 0.88 and 0.90.

In order to investigate students’ attitudes towards isolated and integrated FFI, the Turkish form of a questionnaire developed by Spada, Barkaoui, Peters, So, and Valeo (2009) was implemented at the end of the school year in both schools. The questionnaire consisted of 26 items, 13 of which could be grouped under the label ‘Activities in Isolated FFI’, while the other 13 could be grouped under the label ‘Activities in Integrated FFI’. The students were asked to judge statements as to whether language forms and content should be taught simultaneously or separately on a five-point Likert scale (strongly disagree to strongly agree).

As another data collection process, semi-structured interviews with 20 students from each school were conducted during the last month of the school year. In addition, conversa-tions with the teachers about the techniques they used in their classrooms lent insights into the processes involved in both types of instruction.

Findings

Vocabulary and grammar development

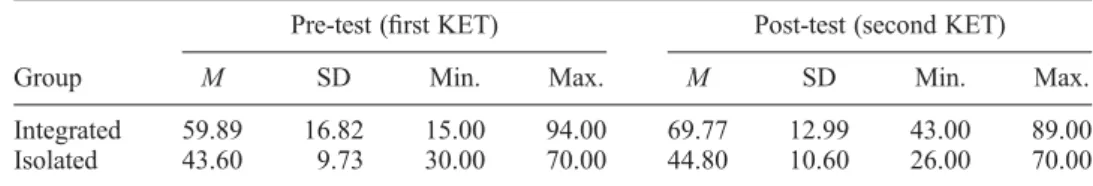

Vocabulary and grammar development in second language was measured through a pre-test and a post-test, the descriptive statistics for which are presented in Table 1.

Table 1 shows an increase in the mean scores of both groups. The increase in the inte-grated group’s scores was higher than that in the isolated group’s scores. There was a sig-nificant difference in the pre-test scores of the two groups (p , 0.01). As random allocation to groups is often impractical in educational settings and thus the initial scores of different groups are often also different, two methods of statistical analysis are appropriate: t-test on the gain scores and analysis of covariance (ANCOVA) partialling out the initial scores (Wright, 2006). For instance, a t-test on gain scores may yield statistical results different from those of the ANCOVA on the same scores. As a result, in order to detect the effect of instructional methods on post-test scores and to see if the differences between the two tests, which were not taken at the same time by each group, are significant, multiple stat-istical analyses were conducted. First, change scores between the pre-test and the post-test scores were calculated, and then an independent samples t-post-test was conducted on the change scores. Change means for the integrated and isolated groups were 9.88 and 1.20, respectively. The results of the t-test on change scores showed that there was a main effect of group, that is, the techniques implemented in the schools had a significant effect on the test scores.

To increase the reliability of the inference, we added a second statistical method to sup-plement the first. To control the baseline covariates, specifically the pre-tests, an ANCOVA on the change scores was conducted with the pre-test scores as the covariate. The ANCOVA confirmed the t-test results. A significant main effect of group (i.e. isolated and integrated instructional techniques) was found (F (1,66) ¼ 24.92, p , 0.001). The integrated FFI was found to be more effective than the isolated FFI in second language vocabulary and grammar learning according to the pre-test and post-test. The integrated FFI group per-formed better than the isolated group on items measuring knowledge of grammar and voca-bulary. The isolated FFI group had difficulty in responding to items that demanded knowledge of vocabulary and combined content and grammar. The integrated FFI group, on the other hand, registered an increase in knowledge of vocabulary and grammar as measured by the pre-test and post-test.

If the allocation of the participants had been problematic, the results of the t-test and ANCOVA would be different from each other. Since the results confirm each other, it can be concluded that the instructional methods had a significant effect on the vocabulary and grammar learning of the students. The fact that the groups’ improvement was measured by the pre-test and post-test scores enables us to attribute the differences between the groups to the different instructional methods. Observations made during the research showed that the methods made it easy or difficult for the students to achieve a degree of automaticity in their use of English. When students in the isolated FFI group were exposed to purposeful content-integrated activities, it was quite clear that their motivation and interest increased and, after some initial mistakes, they were able to integrate new language forms and voca-bulary into what they already knew. However, the same students became less motivated and visibly bored when the instruction was focused on language forms in isolation. Even if they

Table 1. Descriptive statistics for second language vocabulary and grammar learning.

Group

Pre-test (first KET) Post-test (second KET)

M SD Min. Max. M SD Min. Max.

Integrated 59.89 16.82 15.00 94.00 69.77 12.99 43.00 89.00

could memorise the rules of language that they had learned in this way, they could not make use of the new rules with any degree of fluency. If we think that the difference between the two groups in terms of their improvement from the pre-test to the post-test can be a result of their ‘already existing’ ability to learn a foreign language, then the isolated group should not have learned some forms or vocabulary items taught through the integrated way of instruc-tion of which the teachers made use on certain occasions, as described in the secinstruc-tion above on the contexts of the schools. It is even likely that the difference between the pre-test scores can be attributed to the two different methods of instruction because the students had been exposed to the two different methods for the previous 3 years of schooling. This is a hypoth-esis that could be explored in another research study.

Findings concerning the second language vocabulary learning, grammar learning, and writing development of both groups complement what was seen during observations made during the lessons. The students in the integrated FFI group knew the meaning of a range of vocabulary items and they could use the words correctly during communica-tive and content-based activities which required them to speak or to write in English. They could also apply their knowledge of grammar. After some time, they could use recently learned language forms and vocabulary items automatically in communicative activities. On the other hand, although the students in the isolated FFI group knew the meaning of certain vocabulary items, they had difficulty in using them correctly when speaking or writing. They could recall the rules of grammar when asked about them explicitly and in isolation, but they were less successful when applying the same rules in a communicative context. However, when they were given a chance to learn language forms and vocabulary through purposeful activities in a meaningful context, they were usually more successful.

Isolated and integrated FFI in writing development

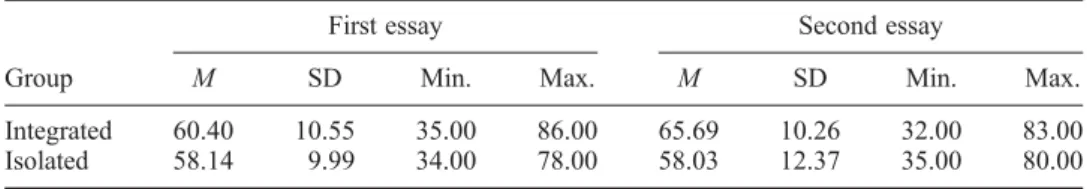

The writing development of the students was measured by comparing scores for two essays. Table 2 presents the descriptive statistics for the students’ writing development.

Table 2 shows that the integrated FFI group had higher means in both essays and that the difference between the two mean scores represents an increase. On the other hand, the iso-lated group had approximately the same means in both essays, with no increase. To inves-tigate the effect of instructional techniques on these essay scores, a 2× 2 mixed-design analysis of variance (ANOVA) was conducted with instructional technique (integrated vs. isolated) as the between-group variable and the essays (first essay and second essay) as the within-group variable. The assumptions of normality, homogeneity of variance, and sphericity were sustained. The ANOVA results revealed that the techniques had a sig-nificant effect on the essay scores. Although the means of the first essay scores of both groups were close to each other, the integrated group’s mean for the second essay was higher than the isolated group’s. The integrated group’s scores improved and the isolated group’s scores remained the same.

Table 2. Descriptive statistics for writing development.

Group

First essay Second essay

M SD Min. Max. M SD Min. Max.

Integrated 60.40 10.55 35.00 86.00 65.69 10.26 32.00 83.00

Because the KET pre-test scores of the two groups were significantly different, another statistical analysis was conducted to supplement our analysis of the essays. To that end, we controlled for the pre-test scores to uncover the main effect of the instructional methods on essay writing. Therefore, the same ANOVA was run again with the pre-test scores as the covariate. The ANCOVA results confirmed the ANOVA results. In other words, when the scores achieved in the pre-test were controlled, it was found that the main effect of group (integrated FFI vs. isolated FFI) was significant (F (1,66) ¼ 8.09, p , 0.01).

The range of vocabulary items used by the integrated group increased from their first essay to their second, as reflected in their means. In terms of grammar usage, most of the students from the integrated FFI used grammatical forms correctly, although there were some occasional errors, and they could write complex sentences as well as simple ones. Organisation and structure of their essays, in general, were appropriate for the task. In con-trast, the isolated group used a narrower range of vocabulary items. Their sentences were not well connected; organisation of the text resembled a list of sentences about the topic. They made grammatical errors, particularly in subject – verb agreement. In general, the pro-blems seen in their first essays were almost the same as those seen in their second essays, although some of the students in the isolated FFI group did perform better in their second essay.

The findings from the essays of both groups are consistent with what was observed during the lessons, as reported above. The students in the integrated FFI group were better able to apply their recently learned knowledge of vocabulary and grammar in com-municative activities, whereas the students in the isolated FFI group had difficulty in apply-ing their language learnapply-ing in speakapply-ing and writapply-ing activities. Durapply-ing their interviews and in their answers to the questionnaire, the students in the isolated FFI group showed that they were aware of their shortcomings and their low level of interest in isolated instruction. However, when they were introduced to more engaging communicative tasks, they showed a greater interest in learning and the capability of transferring what they had learned into another context.

To sum up the findings from the pre-test and post-test, it can be concluded that there was a significant main effect of the instructional methods on second language vocabulary and grammar development of the students (F (1,66) ¼ 24.92, p , 0.001). Findings from the essays show that students exposed to integrated FFI performed better than those exposed to isolated FFI (F (1,66) ¼ 8.09, p , 0.01). Integrated FFI was found to be more effective for teaching vocabulary and grammar even though the main focus of the language lessons was not language alone. These findings are parallel to the findings of previous research, which suggest that language and content integration can result in language development as well as content learning (e.g. Chapple & Curtis, 2000; Edwards, Wesche, Krashen, Clement, & Kruidenier, 1984; Gilzow & Branaman, 2000; Leaver & Stryker, 1989; Rodgers, 2006; Snow & Brinton, 1988; Swain & Lapkin, 1989). When learners are exposed to purposeful and meaningful samples of the target language and when they are taught a subject matter and language simultaneously, their language learning improves (Brinton et al., 1989; Crandall, 1987; Krashen, 1985; Met, 1991).

Consistent with the claims made by Chapple and Curtis (2000), the researcher observed that the students in the integrated language classes became highly motivated when engaged in a meaningful task aimed at a communicative target such as writing a story, finding a secret word, or finishing a puzzle – all based on content. These content-based activities caused the students to pay attention to the content and to language forms in order to accom-plish the task at hand. As a result, the students’ knowledge of content and language improved to the point of automaticity.

In the isolated FFI classes, the students were also engaged in content-based and com-municative activities. However, they were taught about language forms in separate de-con-textualised sessions, either before or after the communicative activities. They were motivated and interested when they were engaged in purposeful communication, but when they were asked to learn about language forms in isolation, they were not so willing to listen to the teacher and they began to talk among themselves. The statements made by the students during their interviews and their responses to a questionnaire support the observer’s conclusions.

Students’ attitudes towards integrated and isolated FFI

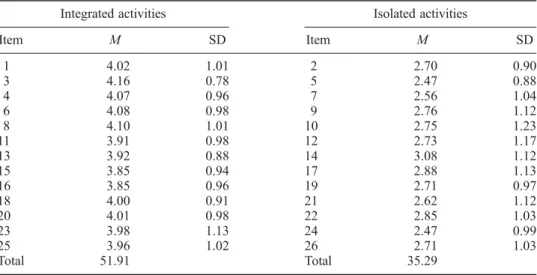

In order to investigate the students’ attitudes towards integrated and isolated FFI in second language learning, they were asked to respond to a 26-item questionnaire. Table 3 presents the statistics describing their responses.

Table 3 shows that the items related to integrated activities were rated higher than those related to isolated activities; the total mean of responses about integrated activities was higher than the mean of responses about isolated activities (51.91 and 35.29). These results show that the students had more positive attitudes towards integrated FFI than towards isolated FFI.

Interviews conducted with 20 students from each school explain their attitudes. One of the questions asked if similarity between the topics taught in other courses (mathematics, science, etc.) and those taught in English courses was helpful for learning English vocabu-lary and grammar. Most of the students (35 of the 40 interviewed) responded to this ques-tion positively. The students’ statements suggest that when the topics from other lessons are studied in English lessons, the students’ background knowledge is stimulated, enabling them to understand and recall the content of the English lessons.

Another question asked if they preferred to be corrected during or after communicative activities such as dialogues, games, and pair-work. Most (30 of 40) preferred to be corrected during the activities rather than after the activities. The students’ statements indicate that when they were corrected during the activities (as in integrated FFI classes), they found it easier to re-analyse their output and change it in accordance with forms of the language.

Table 3. Descriptive statistics for students’ attitudes towards integrated and isolated FFI.

Integrated activities Isolated activities

Item M SD Item M SD 1 4.02 1.01 2 2.70 0.90 3 4.16 0.78 5 2.47 0.88 4 4.07 0.96 7 2.56 1.04 6 4.08 0.98 9 2.76 1.12 8 4.10 1.01 10 2.75 1.23 11 3.91 0.98 12 2.73 1.17 13 3.92 0.88 14 3.08 1.12 15 3.85 0.94 17 2.88 1.13 16 3.85 0.96 19 2.71 0.97 18 4.00 0.91 21 2.62 1.12 20 4.01 0.98 22 2.85 1.03 23 3.98 1.13 24 2.47 0.99 25 3.96 1.02 26 2.71 1.03 Total 51.91 Total 35.29

Given the seven types of activities used during English lessons, the students were asked to choose three that they considered to be beneficial for learning and using vocabulary items and language forms. After the students made their choices, the researcher asked them why they chose those activities and how those activities helped them. The students’ responses reveal that they valued different activities for different purposes. For instance, some of the students preferred grammar exercises because they believed that grammar exercises helped them to respond to the items in discrete-point tests. They believed that to be success-ful in structured and form-focused tests, they needed to have exercises that facilitate the acquisition of explicit knowledge about grammatical forms and vocabulary. On the other hand, they also preferred communicative and content-based activities because they believed that these activities helped them to use new vocabulary items and language forms in context. They claimed that when they learned a rule or vocabulary item during a task, they could use it immediately and recall it more easily afterwards.

Towards the end of the interviews, the researcher described two different language lessons. One exemplified integrated FFI, the other isolated FFI. While describing these ima-ginary lessons, she sometimes reminded the students of activities or exercises in their English lessons. Then, she asked them which lesson they thought would be more useful for learning English. Twenty-nine of 40 students preferred the integrated FFI type of lesson and 11 pre-ferred the isolated FFI type of lesson. Common reasons for most of them preferring the inte-grated lesson were that: (1) they preferred using the language to say something with purpose in a meaningful context; and (2) they felt more motivated when they were involved in com-municative activities. They reported that they were sometimes confused by formulas for language rules and that they had difficulty in remembering and applying rules they had learned in isolation. The students were aware that using language forms and vocabulary items in the context of writing or reading activities helped them to recall them afterwards.

On the other hand, the statements made by students who preferred the isolated FFI type of lesson indicated that explicit instruction helped them to apply language forms in their sentences. Some of these students reported that it is difficult to notice a grammatical rule if it is not taught explicitly. They preferred to have the rules stated explicitly instead of extracting them from other instructional activities. Another common reason for them pre-ferring isolated FFI was that it helped them to perform better in structured grammar-based tests that required memorising rules but not using them in speaking or writing.

The students’ statements about integrated FFI led to the conclusion that their interest in language classes increased and they felt more motivated when they had an objective requir-ing the use of content knowledge. For example:

This one (the integrated lesson) seems to be more enjoyable for me. I like attending (to) such activities more.

The teacher often gives us tasks and we try to finish (them) and find out the result immediately. For example, we try to find a secret word by following the instructions in a game. I like English when we do such activities.

The researcher observed that the motivation of the students in the integrated FFI group increased considerably when they were engaged in a goal-directed task such as writing a story, finding a secret word, or finishing a puzzle. The statements made by some of the stu-dents suggest as much. For example:

I like English; but when the teacher begins to explain some rules in an extended way, I get bored and do not want to listen to her.

When we deal with rules in detail, it becomes very confusing for me. I cannot keep all the rules in my mind and I often confuse them, so I get bored.

Discussion and implications for foreign language teaching

Based on the relative improvement shown between the pre-test and post-test, one can con-clude that integrated FFI was more effective for teaching vocabulary and grammar than iso-lated FFI. The statements made by the students and the researcher observations of both types of lessons provide additional information about the effectiveness of the methods. Motivation increased when the students were involved in purposeful activities integrating content and language learning. The fact that the pre-test scores of the isolated group were lower than those of the integrated group might imply that the isolated group was less able to learn a foreign language; however, observations suggest otherwise. The students in the iso-lated FFI group were seen to learn certain topics successfully through content-integrated activities.

In answer to the first and second research questions, these findings support the hypoth-esis that second language learning is achieved during content instruction (Crandall, 1993; Krashen, 1985). When learners are exposed to purposeful and meaningful samples of the target language and when they are taught a subject matter and language simultaneously, their language learning improves (Brinton et al., 1989; Crandall, 1987; Krashen, 1985; Met, 1991). As the students purposefully tried to achieve a communicative objective, their increased motivation resulted in both language learning and sustained retention (Chapple & Curtis, 2000).

In the integrated FFI classrooms, the students were expected to make connections between new knowledge and what they already knew about the content and the language forms. As learners connect new learning with previous learning, learning becomes more meaningful (Flowerdew, 1993; Genesee, 1994; Kasper, 1995). When the students in the integrated FFI group addressed topics that were related to previously studied topics, and when they could use similar language forms to communicate new ideas, their language use became more automatic. It is likely that repeated opportunities to make and repeat these connections contributed to better language use and better performance in the essay-writing tasks.

Observations made in the isolated FFI classrooms showed that although the students could use certain target language forms correctly during some structured and grammar-centred activities, such as fill-in-the-gaps or true/false exercises, they had more difficulty in using the same target forms in contextualised communicative activities, including essay writing. Some students pointed out this difficulty during the interviews. For example:

When the teacher explains the rules, I can understand them very well. For example, I know we have to put ‘-s’ at the end of the verbs when our subject is ‘he, she’, or ‘it’. But when I’m talking or writing, I often forget to use -s and so I make a mistake . . . But on multiple-choice tests, I can do better, because I remember the rules immediately when I look at the options and I can find the correct option easily.

One can conclude from such statements that the students could learn certain rules about linguistic forms in the target language through isolated and explicit instruction. They could manage tasks that were structured and grammar focused. However, they had to make an extra effort to transfer what they had learned through isolated instruction into their commu-nicative activities.

This study also investigated the students’ attitudes towards integrated and isolated FFI through a questionnaire and interviews. The results of the questionnaire showed that most of the students preferred integrated FFI. When the content of lessons is related to the stu-dents’ needs, interests, and previous learning, the lessons become more interesting and more motivating (Genesee, 1994; Mohan, 1986; Snow, Met, & Genesee, 1989). The stu-dents reported as much; they liked English lessons when they had to carry out some task, and they became bored when they were taught language forms and rules in isolation. The results of this study have certain implications for foreign language teaching. In order to make use of the effectiveness of integrated FFI, the EFL curriculum must address the needs and interests of the students. Subject matter teachers and language tea-chers should cooperate in order to develop a curriculum that has both content objectives and language objectives. This collaboration can provide the students with a knowledge base that facilitates language learning, and as their language learning becomes more mean-ingful, their motivation is also increased.

Instruments for student assessment also need to be developed. Since integrated FFI has content and language objectives, assessment instruments need to measure student progress towards both. Data derived from appropriate instruments would also help teachers to fine-tune the language programme.

Conclusion

This study examined the effectiveness of an integrated and an isolated FFI programme in terms of vocabulary and grammar development. Considering the results obtained from stat-istical analyses of the gain scores, it can be concluded that students exposed to integrated FFI learned second language vocabulary and grammar more successfully than students exposed to isolated FFI. In addition, the statements made by the students and the researcher observations lead to the conclusion that students are more interested and more motivated to learn second language through integrated FFI than through isolated FFI.

This study also examined the effect of integrated and isolated FFI on the writing devel-opment of the students. It was found that the students in the integrated FFI group achieved higher scores in essay-writing tasks than the students in the isolated FFI group.

Examination of the students’ attitudes towards integrated and isolated FFI showed that, overall, they preferred the methodology of integrated FFI. They reported that they were more interested and more motivated when their language instruction was integrated in pur-poseful communicative tasks. However, some students also pointed out that isolated FFI helped them to answer the questions in tests of grammar and vocabulary. The results from interviews with students and an attitudes questionnaire suggest that curriculum devel-opers in Turkey need to consider students’ attitudes when developing new language programmes.

Considering a number of limitations, the results of this study should be taken as sugges-tive rather than as definisugges-tive. It was a case study with a limited number of participants, and the participants were not randomly assigned to the integrated and isolated FFI groups. Experimental studies with a higher number of participants would result in a more detailed appraisal of the effectiveness of both methods.

References

Alptekin, C., Erc¸etin, G., & Bayyurt, Y. (2007). The effectiveness of a theme-based syllabus for young L2 learners. Journal of Multilingual and Multicultural Development, 28(1), 1 – 17.

Bayyurt, Y., & Alptekin, C. (2000). EFL curriculum design for Turkish young learners in bilingual school contexts. In J. Moon & M. Nikolov (Eds.), Research into teaching English to young lear-ners: International perspectives (pp. 312 – 322). Pecs: University of Pecs Press.

Brinton, D.M., Snow, M.A., & Wesche, M.J. (1989). Content-based second language instruction. New York, NY: Newbury House.

Cantoni-Harvey, G. (1987). Content-area language instruction: Approaches and strategies. Reading, MA: Addison-Wesley.

Chapple, L., & Curtis, A. (2000). Content-based instruction in Hong Kong: Student responses to film. System, 28(3), 419 – 433.

Crandall, J. (1987). ESL through content-area instruction. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice Hall. Crandall, J. (1993). Content-centred learning in the United States. Annual Review of Applied

Linguistics, 13, 111 – 126.

Cummins, J. (1980). The cross-lingual dimensions of language proficiency: Implications for bilingual education and the optimal age issue. TESOL Quarterly, 14(2), 175 – 187.

Dafouz, E., Nu´n´ez, B., & Sancho, C. (2007). Analysing stance in a CLIL university context: Non-native speaker use of personal pronouns and modal verbs. The International Journal of Bilingual Education and Bilingualism, 10(5), 647 – 662.

Doughty, C., & Williams, J. (Eds.). (1998). Pedagogical choices in focus on form. In Focus on form in classroom SLA (pp. 197 – 261). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Edwards, H., Wesche, M., Krashen, S., Clement, R., & Kruidenier, B. (1984). Second-language acqui-sition through subject-matter learning: A study of sheltered psychology course classes at the University of Ottawa. The Canadian Modern Language Review, 41(2), 268 – 282.

Ellis, R. (2001). Introduction: Investigating form-focused instruction. Language Learning, 51(Supplement 1), 1 – 46.

Flowerdew, J. (1993). Content-based language instruction in a tertiary setting. English for Specific Purposes, 12(2), 121 – 138.

Genesee, F. (1994). Language and content: Lessons from immersion (Educational Practice Report No. 11). Washington, DC: Center for Applied Linguistics and National Center for Research on Cultural Diversity and Second Language Learning.

Gilzow, D., & Branaman, L.E. (2000). Lessons learned: Model early foreign language programs. Washington, DC: Center for Applied Linguistics.

Grabe, W., & Stoller, F.L. (1997). Content-based instruction: Research foundations. In M.A. Snow & D.M. Brinton (Eds.), The content-based classroom: Perspectives on integrating language and content (pp. 5 – 21). White Plains, NY: Longman.

Harley, B., Cummins, J., Swain, M., & Allen, P. (1990). The nature of language proficiency. In B. Harley, P. Allen, J. Cummins, & M. Swain (Eds.), The development of second language profi-ciency (pp. 7 – 25). New York, NY: Cambridge University Press.

Kasper, L.F. (1995). Theory and practice in content-based ESL reading instruction. English for Specific Purposes, 14(3), 223 – 229.

Kasper, L.F. (1997). The impact of content-based instructional programs on the academic programs of ESL students. English for Specific Purposes, 16(4), 309 – 320.

Krashen, S.D. (1985). The input hypothesis: Issues and implications. London: Longman.

Larsen Freeman, D., & Long, M.H. (1991). An introduction to second language acquisition research. New York, NY: Longman.

Leaver, B.L., & Stryker, S.B. (1989). Content-based instruction for foreign language classrooms. Foreign Language Annals, 22(3), 269 – 275.

Lightbown, P.M. (2000). Anniversary article: Classroom SLA research and second language teaching. Applied Linguistics, 21(4), 431 – 462.

Lyster, R. (1987). Speaking immersion. Canadian Modern Language Review, 43(4), 701 – 717. Lyster, R. (1998). Negotiation of form, recasts, and explicit correction in relation to error types and

learner repair in immersion classrooms. Language Learning, 48(2), 183 – 218.

Mehisto, P., & Asser, H. (2007). Stakeholder perspective: CLIL programme management in Estonia. International Journal of Bilingual Education and Bilingualism, 10(5), 683 – 701.

Met, M. (1991). Learning language through content: Learning content through language. Foreign Language Annals, 24(4), 281 – 295.

Netten, J. (1991). Towards a more language oriented second language classroom. In L. Malave´ & G. Duquette (Eds.), Language, culture and cognition (pp. 284 – 304). Clevedon: Multilingual Matters.

Norris, J.M., & Ortega, L. (2000). Effectiveness of L2 instruction: A research synthesis and quanti-tative meta-analysis. Language Learning, 50(3), 417 – 528.

Pica, T. (2002). Subject-matter content: How does it assist the interactional and linguistic needs of classroom language learners? The Modern Language Journal, 86(1), 1 – 19.

Reid, J. (1993). Teaching ESL writing. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice Hall Regents.

Rodgers, D.M. (2006). Developing content and form: Encouraging evidence from Italian content-based instruction. The Modern Language Journal, 90(3), 373 – 386.

Snow, M.A. (1991). Teaching language through content. In M. Celce-Murcia (Ed.), Teaching English as a second or foreign language (2nd ed., pp. 315 – 326). Boston, MA: Heinle & Heinle. Snow, M.A., & Brinton, D.M. (1988). The adjunct model of language instruction: An ideal EAP

fra-mework. In S. Benesch (Ed.), Ending remediation: Linking ESL and content in higher education (pp. 33 – 52). Washington, DC: TESOL.

Snow, M.A., Met, M., & Genesee, F. (1989). A conceptual framework for the integration of language and content in second/foreign language instruction. TESOL Quarterly, 23(2), 201 – 217. Spada, N. (1997). Form-focused instruction and second language acquisition: A review of classroom

and laboratory research. Language Teaching, 30(2), 73 – 87.

Spada, N., Barkaoui, K., Peters, C., So, M., & Valeo, A. (2009). Developing a questionnaire to measure learners’ preferences for isolated and integrated form-focused instruction. System, 37(1), 70 – 81.

Spada, N., & Lightbown, P.M. (2008). Form-focused instruction: Isolated or integrated? TESOL Quarterly, 42(2), 181 – 207.

Stryker, S.B., & Leaver, L.L. (1997). Content-based instruction in foreign language education: Models and methods. Washington, DC: Georgetown University Press.

Swain, M. (1985). Communicative competence: Some roles of comprehensible input and comprehen-sible output in its development. In S. Gass & C. Madden (Eds.), Input in second language acqui-sition (pp. 215 – 258). New York, NY: Newbury House.

Swain, M., & Lapkin, S. (1989). Canadian immersion and adult second language teaching: What is the connection? The Modern Language Journal, 73(2), 150 – 159.

Wesche, M.B., & Skehan, P. (2002). Communicative, task-based and content-based language instruc-tion. In R.B. Kaplan (Ed.), The Oxford handbook of applied linguistics (pp. 227 – 228). Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Wright, D.B. (2006). Comparing groups in a before-after design: When t test and ANCOVA produce different results. British Journal of Educational Psychology, 76(3), 663 – 675.

Yalc¸ın, S¸. (2007). Exploring the relationships among L1 academic language proficiency, L2 language proficiency, and content knowledge in a delayed partial immersion program (Unpublished Master’s thesis). Bogazic¸i University, Istanbul, Turkey.