1877-0428 © 2010 Published by Elsevier Ltd. doi:10.1016/j.sbspro.2010.07.101

Procedia Social and Behavioral Sciences 5 (2010) 339–344

WCPCG-2010

Outcome of anger management training program in a sample of

undergraduate students

AslÕ T. Akdaú Mitrani

a*

a Dogus University, Acibadem, Kadikoy, Istanbul 34722, Turkey Received January 14, 2010; revised February 27, 2010; accepted March 23, 2010

Abstract

In the present study effectiveness of an anger management training program which has been grounded on cognitive-behavior therapy principles was examined. The trainings were implemented to three groups of undergraduate students (N=28) concurrently, for a period of six weeks. A control group (N= 28) was selected from the same sampling frame. Pre- and post-test measures were obtained by State-Trait Anger Scale (Ozer, 1994), with a period of 6-months in between. Results demonstrated the effectiveness of the training; mean post-test anger-control score was significantly higher than the mean pre-test anger-control score for the treatment group, and no significant differences were found within the control group.

Keywords: Anger management training, outcome research, effectiveness, cognitive behavioral treatment, anger.

1. Introduction

In Turkey, research on anger related problems is very limited and mostly was conducted in the last decade (Sayar et al., 2000; ùahin-Hisli, Onur, & BasÕm, 2008; Yasak & Eúiyok, 2009). Adaptation of assessment tools into Turkish (Ozer, 1994; Aslan, & SevÕnçler-Togan, 2009; Ozdamli, 2009) and development of original anger expression assessment devices exclusively sensitive to the socio-cultural context of Turkey (Balkaya, & ùahin-Hisli, 2003) represent other significant research on anger in Turkey. There are some small-scale studies conducted in samples of adolescents and undergraduates aiming at to explore the effectiveness of interventions such as CBT, psychodrama, emotional intelligence training (Karataú, 2009; Karataú & Gökçakan, 2009; ùahin, 2006; YÕlmaz, 2009). When it comes to socio-cultural differences in the expressions of anger the research seems limited. It was argued that the socio-cultural context and gender roles imply the way of anger expression for the Turkish women and it was more acceptable to complain about physical illness like anger related headache or hyper tension (Thomas, 2005; Thomas & Atakan, 1993).

A number of meta-analyses have been conducted to determine the efficacy of a variety of treatment approaches and there is evidence that cognitive-behavioral interventions were the most effective in working on the anger related problems (Beck & Fernandez, 1998; Del Vecchio & O'Leary, 2004; DiGuiseppe & Tafrate, 2003; Sukhodolsky, Kassinove, & Gorman, 2001; Tafrate, 1995). Meta-analytical research indicated different effect sizes for various

* Asli T. Akdaú Mitrani Tel.: +90-216-544-5555; fax: +90-216-544-5533. E-mail address: aakdas@dogus.edu.tr.

© 2010 Elsevier Ltd. Open access under CC BY-NC-ND license.

approaches within the cognitive behavioral treatments. Tafrate (1995) found the largest effect size for relaxation based treatments, whereas DiGuiseppe and Tafrate (2003) indicated that the largest effect size for cognitive restructuring, followed by systematic desensitization. In general it is not clear which component is the most efficacious in treating anger problems but confidently it is concluded that cognitive and behavioral interventions have to be involved in anger management training. Sukhodolsky and colleagues (2001), based on a meta-analytical review found moderate effect sizes for different models of CBT. In reducing aggressive behavior social skills training and multimodal treatments were more effective, whereas in reducing subjective anger experiences problem-solving treatments were more effective. Moreover, the use of homework was significantly and positively related to therapy outcomes. Del Vecchio and O'Leary (2004) reviewed the anger treatment research that was conducted in the last 20 years and the superiority of cognitive therapies in treating anger suppression whereas cognitive-behavior therapy in treating anger expression problems.

The aim of the present study was to examine the effectiveness of an anger management training program which has been grounded on cognitive-behavior therapy principles and delivered in a group setting. The effectiveness and efficacy research provided the empirical ground in the selection of interventions that were employed in the treatment group. The present study represents a preliminary attempt to explore the effectiveness of an anger management training in a non-Western society.

2. Method

2.1.Participants

Twenty-eight undergraduate psychology students with a mean age of 21.96 (sd= 3.18) attended to a Anger Management Training Program (AMP) participated in the treatment condition and 28 undergraduate psychology students with a mean age of 22.56 (sd= 3.42) participated in the control group. Both samples were drawn from a sample of undergraduate students of psychology in the same university in Istanbul. The AMP was announced to the students during various classes and the participants who applied to the AMT constituted the treatment group and the same number of non-applicants was selected to the control group. Of the control group 93 % were females (n= 26) and for the control group 96 % (n= 27) were females. The AMP Group consisted of 5 first-year, 8 second-year, 12 year, and 3 fourth year students, whereas the Control Group consisted of 4 first-year, 12 second-year, 7 third-year, and 5 fourth-year students.

2.2 Measures 2.2.1 STAXI

The participants of the AMP and the control subjects were administered Turkish version of STAXI-State Trait Anger Scale (Ozer, 1994) in the very beginning of the AMP. STAXI was administered for pre- and post-assessments. The scale consists of 10 items to assess State Anger, and 24 items that assess anger expression style (anger-in, anger-out, anger-control). The responses of the subjects were rated on a 4-point Likert scale between 1and 4. Based on the responses for each subject trait anger score, anger-in score, anger-out score and anger-control score were attained. Trait-anger score indicates more intense levels of anger within the person, Anger-in score indicates anger suppression, anger-out score indicates expression of anger to others easily, anger-control score indicates one's capability to control one's own anger.

2.2.2 Anger Management Training Program (AMP)

Three parallel groups of AMP was conducted for 6 sessions, once a week. Each session lasted for 90 minutes and composed of 9-10 participants. Each group was lead by two co-therapists, and a total of 6 intern-psychotherapists served as facilitators. The entire psychotherapist received the same training in the same graduate program on cognitive behavioral psychotherapy and supervision from the author all at the same time each week during the AMP. Each session of AMP was focused on a different theme and skill that were found to be effective in the efficacy researches. Starting from the first week the participants filled in self monitoring forms to gather data to work on their anger. In the beginning of each session self-monitoring forms were evaluated in the group. The themes of the each session were delivered through active discussion and group activities. The topics for the six sessions included

psycho-education, relaxation, cognitive restructuring, assertiveness training, problem solving skills training, role plays and implementation of self-monitoring.

2.3 Procedure

The participation was voluntary as mentioned earlier. In the beginning of the AMP the pre-assessments were taken for both the treatment group and the control group (April 2009). Each session was run for each of the three groups on different days of the same week after the classes in the university (after 6 pm). The supervision of the psychotherapists was at the same time as a group session each week. Post-assessments were conducted after six months following the end of the AMP in the same week to both of the groups (November 2009). The anonymity and confidentiality of their answers were reassured and informed consent for participation was acquired.

3. Results

Within subjects design with control group was applied in the present study. The pre-test and post-test scores as taken by STAXI were studied both for the AMP group and for the control group.

T-tests for independent samples design were applied to the pre-test scores and no significant differences were found between the AMP group and the control group in the mean trait anger score (p>.05), mean anger-out score (p>.05), mean anger-in score (p>.05), mean anger-out score (p>.05), and mean anger-control (p>.05) scores, indicating equal variances for the two groups in terms of trait anger and anger expression styles.

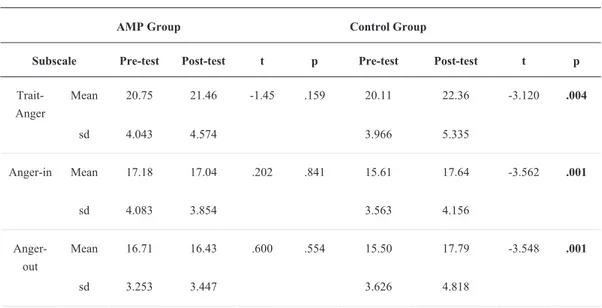

Paired samples t-test was applied to assess the variance between the pre-test and post-test assessments for the trait-anger score, anger-in, anger-out, and anger-control scores of the AMP group and the control group. It was found that mean post-test anger-control score (M= 24.21, sd= 10.91) was significantly higher than the mean pre-test anger-control score (M= 20.18, sd= 4.01) of the AMP group [t(27)= -2.064, p<.05)], whereas no significant variance was found between the pre- and post- assessments in the mean trait-anger score (p>.05) and mean anger-in (p>.05), and anger-out scores (p>.05) of the AMP group. In the control group, there were significant variances between the pre and postassessments in the mean traitanger score [t(27)= 3.120, p<.05], in the mean angerin score [t(27)= -3.562, p=.001], in the mean anger-out score [t(27)= -3.548, p=.001] and no significant difference was found between the pre- and post-assessments of the anger-control scores (p>.05). It was found that for the control group there is a significant increase in the mean trait-anger, anger-in, and anger-out scores between the pre-and post-assessments. See Table 1 for pre-test and post-test mean scores for each subscale of STAXI of the AMP group and for the control group.

Table 1. Pre- and post-assessment mean scores for the subscales of STAXI for the AMP (n=28) and for the control group (n=28)

AMP Group Control Group

Subscale Pre-test Post-test t p Pre-test Post-test t p

Mean 20.75 21.46 -1.45 .159 20.11 22.36 Trait-Anger sd 4.043 4.574 3.966 5.335 -3.120 .004 Mean 17.18 17.04 .202 .841 15.61 17.64 Anger-in sd 4.083 3.854 3.563 4.156 -3.562 .001 Mean 16.71 16.43 15.50 17.79 Anger-out sd 3.253 3.447 .600 .554 3.626 4.818 -3.548 .001

Mean 20.18 24.21 21.64 22.11 Anger-control sd 4.010 10.905 -2.064 .049 4.739 5.473 -.489 .629

4. Conclusion and Discussion

In the present research the effectiveness of an anger management training program was explored. Evidence-based practice was central to the selection of the interventions that were performed in the training group. The results supported the earlier findings on the effectiveness of cognitive-behavior therapy on anger control.

The results indicated that anger control scores of the participants who received anger management interventions in a group setting for six sessions were significantly higher than the controls after 6 months following the interventions. Moreover in the AMP group, there was no other significant changes were found in trait anger, anger-in, and anger-out scores. On the other hand, the control group displayed increased trait anger, anger-in and anger-out scores after 6 months. The change that was found in the post-assessments of the controls were not detected in the AMP group. This is an unexpected but possibly meaningful finding demonstrated by the present data. The cognitive-behavioral interventions affected the anger-control in the AMP participants, while the participants who did not receive any interventions displayed higher levels of trait anger, higher levels of anger suppression and more frequent externalizing demonstrations of anger after six months. A possible conclusion which could be drawn based on the present results is that anger management training is not only induce change in the direction of successful control of anger, at the same time a preventive effect is induced against the maladaptive forms and intensities of anger.

The present study demonstrated long-term lasting positive outcome of the anger-management program. An overview of the current research on the term effectiveness of CBT on anger management indicated that long-term follow-ups were relatively rare. There is limited evidence about long-long-term effectiveness based on follow-ups, like 1-year (Deffenbacher, 1988; Deffenbacher & Stark, 1992), 15 months (Deffenbacher, Oetting, Huff, & Thwaites, 1995) and 3-years (Lochmann, 1992). It was observed that post-assessments were taken usually between 4 weeks (Deffenbacher, Lynch, Oetting, & Kemper, 1996; Deffenbacher, Story, Brandon, Hogg, & Hazaleus, 1988; Deffenbacher, Story, Stark, Hogg, & Brandon, 1987; Deffenbacher, Thwaites, Wallace, & Oetting, 1994; Hazaleus & Deffenbacher, 1986; Soffronof, Attwood, & Tinton, 2007) and 15 weeks (Grodnitzky & Tafrate, 2000) following the treatment. Therefore present results provided additional support for the long-term lasting effects of anger management training.

Finally, the current study was an attempt to demonstrate the validity of CBT on anger control in a non-Western culture. Traditionally Turkey is a collectivistic society and as argued by Sato (1998) the psychotherapy paradigm of the Western therapies has its roots in individualistic cultures. For the case of Turkey, there is room for further research to identify socio-cultural issues that affect the effectiveness of CBT. Moreover, Thomas (2005) has demonstrated that anger expression style of the Turkish women varied significantly from the American and it was stated that culture possibly dictates the acceptable and non-acceptable ways of expressions of anger. There are other findings demonstrating the cultural variations in the expression and regulation of anger and it was argued that future research has to be focused upon the cultural considerations in applying the criteria of psychiatric disorders and clarification of the cultural roots of expressive symptomatology (Kim & Zane, 2004; Malgady, Rogler, & Cortés, 1996).

There is a current trend on the integration of evidence-based practice and multiculturalism in CBT (Hays, 2009), and the present research is a very preliminary step to demonstrate the effectiveness of evidence-based practice on anger-control, in a sample of Turkish undergraduates. In the future, culturally sensitive issues in the treatment have to be identified and culturally-correct interventions have to be developed based on empirical research conducted in Turkish populations.

In conclusion, as mentioned by DiGiuseppe & Tafrate (2001), anger is a frequent and debilitating client problem, and clear conceptual and practical formulations are required to work effectively on anger related problems. However, it was observed that outcome literature is relatively small and limited to a few therapeutic approaches, further research on the efficacy of the active ingredients of the cognitive-behavior psychotherapy of anger is needed.

References

Aslan, A. E. & SevÕnçler-Togan, S. A. (2009). Service for emotion management: Turkish Version of the Adolescent Anger Rating Scale (AARS). Educational Sciences: Theory & Practice, 9(2), 391-400.

Balkaya, F. & ùahin Hisli, N. (2003). Multidimensional anger scale, Türk Psikiyatri Dergisi, 14(3), 192-202.

Beck, R., & Fernandez, E. (1998). Cognitive-behavioral treatment of anger: A Meta-analysis. Cognitive Therapy and Research, 22, 63-74. Deffenbacher, J. L. (1988). Cognitive-relaxation and social skills treatments of anger: A year later. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 35(3),

234-236.

Deffenbacher, J. L., Lynch, R. S., Oetting, R. O., & Kemper, C. C. (1996), Anger reduction in early adolescents. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 43(2), 149-152.

Deffenbacher, J. L., Oetting, E. R., Huff, M. E., & Thwaites, G. A. (1995). Fifteen-month follow-up of social skills and cognitive-relaxation approaches to general anger reduction. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 42(3), 400-405.

Deffenbacher, J. L. & Stark, R. S. (1992). Relaxation and cognitive-relaxation treatments of general anger. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 39(2), 158-167.

Deffenbacher, J. L., Story, D. A., Brandon, A. D., Hogg, J. A., & Hazaleus, S. L. (1988). Cognitive and cognitive-relaxation treatments of anger. Cognitive Therapy and Research, 12, 167-184.

Deffenbacher, J. L. Story, D. A., Stark, R. S., Hogg, J. A., & Brandon, A. D. (1987). Cognitive-relaxation and social skills interventions in the treatment of general anger. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 34(2), 171-176.

Deffenbacher, J. L., Thwaites, G. A. Wallace, T. L., & Oetting, E. R. (1994). Social skills and cognitive-relaxation approaches to general anger reduction. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 41(3), 386-396.

Del Vecchio, T., & O’Leary, K. D. (2004). Effectiveness of anger treatments for specific anger problems: A meta-analytic review. Clinical Psychology Review, 24(1), 15–34.

DiGiuseppe, R. & Tafrate, R. C. (2001). A comprehensive treatment model for anger disorders. Psychotherapy: Theory, Research, Practice, Training, 38(3), 262-271.

DiGiuseppe, R. & Tafrate, R. C. (2003). Anger treatment for adults: A meta-analytic view. Clinical Psychology: Science and Practice, 10(1), 70-84.

Grodnitzky, G. R. & Tafrate, R. C. (2000). Imaginal exposure for anger reduction in adult outpatients: A pilot study. Journal of Behavior Therapy and Experimental Psychiatry, 31, 259–279.

Hays, P. A. (2009). Integrating evidence-based practice, cognitive–behavior therapy, and multicultural therapy: Ten steps for culturally competent practice. Professional Psychology: Research and Practice, 40(4), 354-360

Hazaleus, S. L. & Deffenbacher, J. L. (1986). Relaxation and cognitive treatments of anger, Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 54(2), 222-226.

Karataú, Z. (2009). The effect of anger management programme through cognitive behavioral techniques on the decrease of adolescents aggression. Pamukkale Üniversitesi E÷itim Fakültesi Dergisi, 2009, 12-24.

Karataú, Z. & Gökçakan, Z. (2009). A comparative investigation of the effects of cognitive-behavioral group practices and psychodrama on adolescent aggression. Educational Sciences: Theory & Practice, 9(3), 1441-1452.

Kim, I. J. & Zane, N. W. S. (2004). Ethnic and cultural variations in anger regulation and attachment patterns among Korean American and European American male batterers. Cultural Diversity and Ethnic Minority Psychology, 10(2), 151-168.

Lochman, J. E. (1992). Cognitive-behavioral intervention with aggressive boys: Three-year follow-up and preventive effects. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 60(3), 426-432.

Malgady, R. G., Rogler, L. H., & Cortés, D. E. (1996). Cultural expression of psychiatric symptoms: Idioms of anger among Puerto Ricans. Psychological Assessment, 8(3), 265-268

Ozdamli, F. (2009). A cultural adaptation study of multimedia course materials forum to Turkish, World Journal on Educational Technology,1,1.

Özer, K.(1994). Preliminary study of the Trait Anger and Anger Expression Scale, Journal of Turkish Psychology, 9(31), 26–35.

Sato, T. (1998). Agency and communion: The relationship between therapy and culture. Cultural Diversity and Mental Health, 4(4), 278-290. Sayar, K., Guzelhan, Y., Solmaz, M., Ozer, O. A., Ozturk, M., Acar, B., & Arikan, M. (2000). Anger attacks in depressed Turkish outpatients.

Annals Of Clinical Psychiatry: Official Journal Of The American Academy Of Clinical Psychiatrists, 12(4), 213-221.

Soffronof, K., Attwood, T., & Tinton, S. (2007). A randomized controlled trial of a cognitive behavioral intervention to anger management in children diagnosed with Asperger Syndrome. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 37, 1203-1214.

Sukhodolsky, D. G., Kassinove, H., & Gorman, B. S. (2001). Cognitive-behavioral therapy for anger in children and adolescents: A meta-analysis. Aggression and Violent Behavior, 9, 247-269.

ùahin Hisli, N., Onur, A., & BasÕm, H. J. (2008). øntihar olasÕlÕ÷ÕnÕn, öfke, dürtüsellik ve problem çözme becerilerindeki yetersizlik ile yordanmasÕ. Türk Psikoloji Dergisi, 23(62), 79-92.

ùahin, H. (2006). The effectiveness of the anger management program of decreasing aggressive behaviours. PDR: Türk Psikolojik DanÕúma ve Rehberlik Dergisi, 3(26):47-61.

Tafrate, R. C. (1995). Evaluation of treatment strategies for adult anger disorders. In H. Kassinove (Ed.), Anger disorders: Definition, diagnosis, and treatment (pp. 109–130). Washington, DC: Taylor & Francis.

Thomas, S. P. (2005). Women’s anger, aggression, and violence. Health Care for Women International, 26, 504-522.

Thomas S. P. & Atakan S. (1993). Trait anger, anger expression, stress, and health status of American and Turkish midlife women. Health Care for Women International, 14(2), 129-43.

Yasak, Y. & Esiyok, B. (2009). Anger amongst Turkish drivers: Driving Anger Scale and its adapted, long and short version, Safety Science, 47(1), 138-144.

YÕlmaz, M. (2009). The effects of an emotional intelligence skills training program on the consistent anger levels of Turkish university.students. Social Behavior & Personality: An International Journal, 37(4), 565-576.