Guler Yavas, Cagdas Yavas, Nasuh Utku Dogan1, Tolgay Tuyan Ilhan2, Selen Dogan1, Pinar Karabagli3, Ozlem Ata4, Ebru Yuce5, Cetin Celik2 Departments of Radiation Oncology, 2Obstetrics and Gynecology, 3Pathology and 4Medical Oncology, Selcuk University, Konya, 1Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, Akdeniz University, Antalya, 5Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, Ufuk University, Ankara, Turkey For correspondence: Dr. Nasuh Utku Dogan, Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, School of Medicine, Akdeniz University, Antalya, Turkey. E‑mail: nasuhutkudogan@ yahoo.com

Pelvic radiotherapy does not deteriorate

the quality of life of women with

gynecologic cancers in long-term

follow-up: A 2 years prospective

single-center study

ABSTRACT

Purpose: To evaluate the emotional, sexual and health‑related quality of life (HRQoL) concerns of the women with gynecologic malignancy treated with curative radiotherapy (RT).

Patients and Methods: A 100 women with diagnosis of gynecologic malignancy were prospectively enrolled. HRQoL at baseline, at the end of RT and during follow‑up was assessed using European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer QoL Questionnaire‑C30 (EORTC QLQ‑C30), EORTC QLQ‑cervical cancer module 24, and Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale. Results: The appetite loss, diarrhea, fatigue, dyspnea, insomnia, nausea and vomiting, pain scores, and sexual activity and sexual enjoyment scores were deteriorated after RT (P = 0.02 for pain scores and P < 0.001 for all other). Body image scores were higher in patients with endometrial cancer (P < 0.01). The emotional function, nausea and vomiting, body image and symptom experience scores were higher in patients who underwent chemotherapy (P = 0.04 and P = 0.01). All the complaints of patients improved during follow‑up period. The global health status scores and the level of depression deteriorated in patients with locoregional recurrent disease and distant metastasis. The anxiety (P = 0.001) and depression (P = 0.007) levels were higher in basal and after‑RT visits but then decreased through the subsequent follow‑up visits.

Conclusion: Although pelvic RT deteriorated HRQoL in patients with gynecologic malignancy, HRQoL improved during the follow‑up period. The progressive disease had a negative impact on HRQoL.

KEY WORDS: Gynecological malignancy, psychological distress, quality of life, radiotherapy, side effects

Original Article

INTRODUCTION

Survival for gynecologic cancer has increased with the advent of new therapeutic modalities.[1] Mild

changes in bowel and bladder function impair the health‑related quality of life (HRQoL) of long‑term survivors, but the severity of these effects does not meet the criteria for gradable toxicity. Therefore, long‑term psychological and QoL impacts of radiotherapy (RT) are still not fully understood.[2]

QoL issues are relevant to all aspects of medicine as well as gynecologic cancers.[3] Over the last decade

increasing attention has been focused on emotional distress and QoL in patients with gynecological cancer.[4,5] This renewed attention is associated

with the growing awareness that cancer diagnosis

and the consequences of multimodal treatments deeply affect woman’s self‑identity, social/intimate relationships, and overall self‑perception as mother and wife as well.[6,7]

Symptoms such as dysuria, urinary incontinence, fecal incontinence, and constipation are commonly associated with radical pelvic surgeries and pelvic RT for gynecologic cancer.[8,9] Although there is a

relative paucity of research documenting bladder

and bowel symptoms, previous studies suggest Access this article online Website: www.cancerjournal.net DOI: 10.4103/0973-1482.187243

PMID: ***

Quick Response Code: This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons

Attribution‑NonCommercial‑ShareAlike 3.0 License, which allows others to remix, tweak, and build upon the work non‑commercially, as long as the author is credited and the new creations are licensed under the identical terms.

For reprints contact: reprints@medknow.com

Cite this article as: Yavas G, Yavas C, Dogan NU, Ilhan TT, Dogan S, Karabagli P, et al. Pelvic radiotherapy does not

deteriorate the quality of life of women with gynecologic cancers in long-term follow-up: A 2 years prospective single-center study. J Can Res Ther 2017;13:524-32.

that these symptoms are common among survivors.[8,10,11]

Moreover, these symptoms may persist long after treatment and may adversely affect QoL.[9,12‑14] In our previous study,

pelvic RT deteriorated HRQoL immediately after treatment in patients with gynecologic malignancies, but HRQoL improved during the follow‑up.[15] Therefore, we suggested

that radiation‑related side effects are the main factors that decrease the HRQoL for patients with gynecologic malignancy. Furthermore, other studies reported that HRQoL and mood in women with gynecological cancer impaired during the treatment and tend to improve over time.[16‑19] Here, we provide

an updated analysis of our previous published data describing the longitudinal modifications of HRQoL scores and emotional status in patients with gynecologic malignancy during 2 years of follow‑up period.

PATIENTS AND METHODS

This prospective study was carried out between January 2011 and March 2014 in the Departments of Radiation Oncology and Obstetrics and Gynecology in Selcuk University. A hundred consecutive patients with histologically proven cervical or endometrial cancer treated with RT were prospectively included in the study. Informed written consent was obtained from all patients using a consent form approved by our Ethics Committee. This study was approved by the Ethics Committee of Selcuk University Faculty of Medicine. The preliminary results of first 57 patients were reported in our previous study.[15]

Patient eligibility

Patients were eligible for this study if they were >18 years of age and had a histological diagnosis of a primary cervical or endometrial cancer. All patients were evaluated with a complete history and a physical examination, review of diagnostic imaging, review of pathologic findings, and assessment of Karnofsky performance status (KPS). The patients who underwent pelvic RT previously and whose KPS were <70 were not included in the study.

Radiotherapy protocol

All the patients received external pelvic RT with a total dosage of 45–50.4 Gy in daily fractions of 1.8–2 Gy. Three‑dimensional conformal RT was performed with photon beam energy in an 18 MV linear accelerator using four field technique. Twenty‑one of our patients received high‑dose‑rate (HDR) brachytherapy with a total dosage of 1860–2800 cGy to Point A.

Assessment of health‑related quality of life, cognitive function, and depression

The primary endpoint of this clinical trial was HRQoL and psychological distress. Two measures were selected for the assessment of HRQoL; (i) the European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer QoL Questionnaire‑C30 (EORTC QLQ‑C30) version 3.0, (ii) the EORTC QLQ‑cervical cancer module 24 (QLQ‑CX24). Moreover, Hospital Anxiety and

Depression Scale (HADS) was used to measure anxiety and depression of the patients.

The EORTC QLQ‑C30 version 3.0 the most commonly used HRQoL instrument in cancer trials is a 30‑item cancer‑specific questionnaire measuring general HRQoL in cancer patients.[20] The EORTC QLQ‑C30 incorporates five functional

scales (physical functioning [PF], role functioning [RF], emotional functioning [EF], cognitive functioning, and social functioning scales); three symptom scales (fatigue, nausea/ vomiting, and pain); six single item scales (dyspnea, insomnia, appetite loss, constipation, diarrhea, and financial impact); and the overall health/global HRQoL scale. All items are scored on the 4‑point Likert scales ranging from 1 (not at all) to 4 (very much). However, two items (items 29 and 30) in the overall health/global HRQoL subscale was scored on a modified 7‑point linear analog scale. All the raw functional scales and individual item scores were transformed to a linear scale that ranged from 0 to 100 in which higher score represented a higher level of functioning or an improved level of symptoms. The items were scaled and scored using the recommended EORTC procedures.[20] EORTC QLQ‑C30 scores were calculated

by a computer‑based program. The reliability and validity of QLQ‑C30 were reported in Turkish population.[21]

The QLQ‑CX24 developed by the EORTC was recently designed to examine the aspects of QOL that are not addressed by the core instrument (EORTC QLQ‑C30). The EORTC QLQ‑CX24 includes 24 items consisting of three multiitem scales (symptom experience, body image, and sexual and/or vaginal functioning) and six single‑item scales (lymphedema, peripheral neuropathy, menopausal symptoms, sexual worry, sexual activity, and sexual enjoyment). The validity and reliability of Turkish version of EORTC QLQ‑CX24 are also available.[22]

The HADS was developed by Zigmond and Snaith in 1983. Its purpose is to provide clinicians with an acceptable, reliable, valid and easy to use practical tool for identifying and quantifying depression and anxiety. It consists of 14 items. The questions with odd number measure the availability of anxiety while questions with even numbers represent depression. There are cutoff points for both anxiety and depression scores. The scores more than 7 and more than 10 represent evidence of anxiety and depression, respectively.[23] The validity and

reliability of HADS in Turkish population were previously reported by Aydemir et al.[24]

The questionnaires were responded by patients themselves and were filled by either patient themselves or by the caregivers. All of these tests were performed at baseline and were repeated at 3rd, 6th, 9th, 12th, 15th, 18th, and 24th month after

the completion of RT.

Statistical analyses

Statistical analyses were performed by SPSS software (version 15.0, SPSS, Chicago, IL, USA). Scores of the questionnaires were

Yavas, et al.: Radiotherapy and quality of life in gynecologic cancers expressed as mean (±standard deviation) and median, where

appropriate. The scores were nonnormally distributed and were therefore compared by nonparametric methods. The numerical comparisons between consecutive measurements (dependent groups) were assessed by Friedman within the whole group comparisons and by Wilcoxon test in pairwise comparisons. The numerical comparisons between independent groups were performed by Kruskal–Wallis test in general group comparisons. The pairwise comparisons between two independent groups were performed by Mann–Whitney U‑test. Bonferroni corrections were used in multiple comparisons for reducing the Type I error. A P < 0.05 was considered to be statistically significant. RESULTS

This prospective study included a hundred women with gynecological cancers. The mean age of the patients was 56.8 ± 9.7 years, 65% of them were married, and 74% were in the postmenopausal state. Basic demographic characteristics of these patients are presented in Table 1. Thirty‑nine of the patients (39%) had cervical cancer, and 59 of the patients (59%) had endometrial cancer, and remaining 2 (2%) had endocervical canal tumor. The clinical and pathological characteristics of the participants were shown in Table 2.

All the patients with endometrial cancer underwent hysterectomy, whereas 53.8% of patients with cervical cancer underwent definitive chemo‑RT. Eighteen of the patients with locally advanced stage cervical cancer underwent extraperitoneal pelvic and paraaortic lymphadenectomy before definitive chemo‑RT. Type III radical hysterectomy along with pelvic lymphadenectomy was performed in 20 patients diagnosed with early stage cervical cancer. Fifty‑four patients with endometrial cancer underwent simple hysterectomy plus pelvic and paraaortic lymphadenectomy while Type III radical hysterectomy along with pelvic and paraaortic lymphadenectomy had to be performed to two patients with clinically Stage II endometrial cancer. Meanwhile in one patient with simple hysterectomy was carried out and lymphadenectomy had to be omitted due to the accompanying comorbidities. Two patients had been referred to our clinic with posthysterectomy diagnosis of serous endometrial adenocarcinoma with disease extending outside the uterus. Pelvic and paraaortic lymphadenectomy (omentectomy) and tumoral debulking had to be performed to those patients. Sixty‑six patients underwent chemotherapy. All of the patients received external beam radiation therapy (EBRT), and the median dose was 4500 cGy (range between 4140 and 5040 cGy). Twenty‑one of our patients underwent HDR brachytherapy, and the median dose was 2800 cGy (range between 1860 and 2800 cGy) to the Point A. One patient with endometrial cancer treatment was discontinued because of acute gastrointestinal (GIS) toxicity, and we stopped EBRT at the dose of 4140 Gy and we applied 2100 cGy intracavitary BRT. Otherwise, treatment was not discontinued because

of any toxicity. Twenty‑one patients with the diagnosis of cervical cancer received definitive chemo‑RT. Six patients with the diagnosis of endometrial cancer received salvage RT after tumor recurrence. All of these six patients also received chemotherapy. The rate of Grade 1 acute GIS and genitourinary system (GUS) complications were 32% and 55%, respectively. None of the patients had Grades 3–4 acute GIS toxicity. One of the patients had chronic Grade 3 GUS toxicity.

We evaluated the HRQoL of the patients with a response rate of 100% at the basal and post‑RT visits. However, response rate gradually decreased and reached to 14% at the 24th month

visits. The completeness of the assessments at the 3rd, 6th, 9th,

12th, 15th, 18th, and 24th month visits were 81%, 66%, 52%, 36%,

26%, 17%, and 14%, respectively. Total follow‑up time was defined as the sum of each patient’s follow‑up times, and it was 1200 patient‑months. Nine patients died, one dropped‑out, 13 had local recurrent disease, and nine had distant metastasis during follow‑up. Only two patients with endometrial cancer

Table 1: Demographic characteristics of the patients

Mean SD Age 56,84 9,71 n % Education Illiterate 34 34.0 Primary school 53 53.0 Secondary school 6 6.0 High school 5 5.0 University 2 2.0 Marital status Single 30 30.0 Married 65 65.0 Widow 5 5.0 Menopausal status Premenopausal 26 26.0 Postmenopausal 74 74.0 Table 2: Disease specific characteristics of the patients n % Diagnose Cervical cancer 39 39.0 Endometrial cancer 59 59.0

Endocervical canal cancer 2 2.0

Surgery

Staging (extraperitoneal) LND 18 18.0

TAH + BSO 1 1.0

TAH + BSO + LND 54 54.0

Type III Hysterectomy + LND 22 25.0

Debulking + LND 2 2.0

Histological diagnose

Adeno ca 51 51.0

Squamous cell carcinoma 35 35.0

Serous adenocarcinoma 6 6.0

SCC insitu 1 1.0

Carcinosarcoma 3 3.0

Adenoachantoma 1 1.0

Adenosquamous cancer 3 3.0

LND=Lymphadenectomy, SCC=Squamous cell carcinoma, TAH=Total abdominal hysterectomy

had a second primary cancer. One had rectum cancer, and the other patient had synchronous ovarian cancer.

European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer Quality of Life Questionnaire 30 scores

A gradual decrease in QLQ‑C30 score was noted in symptom scales, and an increase was observed in functional scales and global health status/QoL during the follow‑up period [Figures 1 and 2]. Figure 3 demonstrates an illustration of the general average of symptom and functional scales.

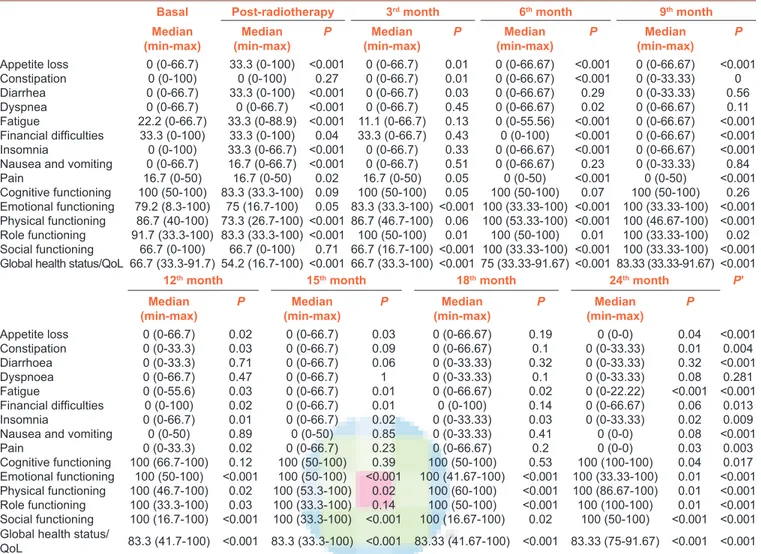

The comparisons of basal scores with each of the subsequent assessments in C‑30 scale are presented in Table 3. The appetite loss, diarrhea, fatigue, dyspnea, insomnia, nausea and vomiting, and pain scores were deteriorated after RT when compared to the baseline scores (P = 0.02 for pain scores and P < 0.001 for all other). The median RF and global health status scores were also decreased after RT (P < 0.001 for both). However, all the symptoms and functioning scales were improved from the beginning of 3rd month visits.

European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer Quality of Life‑cervical cancer module 24 scores

There was a mixed pattern of increases and decreases in symptom scales of QLQ‑CX24 [Figure 4]. The comparisons

of basal scores with each of the subsequent assessments in CX24 scale are presented in Table 4. When the scores in nine different evaluation visits were compared together, statistically significant differences were found only in symptom experience, peripheral neuropathy, sexual activity, and sexual enjoyment domains. There were significant differences in symptom experience, lymphedema, and peripheral neuropathy scores between the baseline and post‑RT (P < 0.001, P < 0.001, and P = 0.03, respectively). Sexual activity and sexual enjoyment scores deteriorated in the post‑RT period; however, at 24th month of follow‑up, both of the scores were improved

significantly (P < 0.001 for both).

Hospital anxiety and depression scores

The presence of anxiety and depression in each follow‑up visit is shown in Figure 5. Both anxiety (P = 0.001) and depression (P = 0.007) levels were higher in baseline and after RT visits but decreased through the subsequent follow‑up visits.

Sociodemographic characteristics and quality of life

The sexual activity scores were significantly correlated with marital status of the patients at baseline, after RT at the end of 3rd, 6th, 12th, and 15th month of RT (baseline P < 0.001, after RT

P < 0.001, and P = 0.01, P = 0.04, P = 0.05, and P = 0.01 for 3rd, 6th, 12th, and 15th month of RT). The sexual activity scores

were higher for married women. The body image scores were

Figure 4: Symptom scales in European Organization for Research

and Treatment of Cancer Quality of Life Questionnaire‑cervical cancer module 24

Figure 1: Symptom scales in European Organization for Research and

Treatment of Cancer Quality of Life Questionnaire‑C30

Figure 2: Functional scales in European Organization for Research

and Treatment of Cancer Quality of Life Questionnaire‑C30

Figure 3: Global health status/quality of life and average scores of

symptom and functional scales of European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer Quality of Life Questionnaire‑C30

Yavas, et al.: Radiotherapy and quality of life in gynecologic cancers

Table 3: Scores of EORTC QLQ-C30, comparisons of each assessment with baseline

Basal Post-radiotherapy 3rd month 6th month 9th month

Median

(min-max) (min-max)Median P (min-max)Median P (min-max)Median P (min-max)Median P

Appetite loss 0 (0-66.7) 33.3 (0-100) <0.001 0 (0-66.7) 0.01 0 (0-66.67) <0.001 0 (0-66.67) <0.001 Constipation 0 (0-100) 0 (0-100) 0.27 0 (0-66.7) 0.01 0 (0-66.67) <0.001 0 (0-33.33) 0 Diarrhea 0 (0-66.7) 33.3 (0-100) <0.001 0 (0-66.7) 0.03 0 (0-66.67) 0.29 0 (0-33.33) 0.56 Dyspnea 0 (0-66.7) 0 (0-66.7) <0.001 0 (0-66.7) 0.45 0 (0-66.67) 0.02 0 (0-66.67) 0.11 Fatigue 22.2 (0-66.7) 33.3 (0-88.9) <0.001 11.1 (0-66.7) 0.13 0 (0-55.56) <0.001 0 (0-66.67) <0.001 Financial difficulties 33.3 (0-100) 33.3 (0-100) 0.04 33.3 (0-66.7) 0.43 0 (0-100) <0.001 0 (0-66.67) <0.001 Insomnia 0 (0-100) 33.3 (0-66.7) <0.001 0 (0-66.7) 0.33 0 (0-66.67) <0.001 0 (0-66.67) <0.001 Nausea and vomiting 0 (0-66.7) 16.7 (0-66.7) <0.001 0 (0-66.7) 0.51 0 (0-66.67) 0.23 0 (0-33.33) 0.84

Pain 16.7 (0-50) 16.7 (0-50) 0.02 16.7 (0-50) 0.05 0 (0-50) <0.001 0 (0-50) <0.001 Cognitive functioning 100 (50-100) 83.3 (33.3-100) 0.09 100 (50-100) 0.05 100 (50-100) 0.07 100 (50-100) 0.26 Emotional functioning 79.2 (8.3-100) 75 (16.7-100) 0.05 83.3 (33.3-100) <0.001 100 (33.33-100) <0.001 100 (33.33-100) <0.001 Physical functioning 86.7 (40-100) 73.3 (26.7-100) <0.001 86.7 (46.7-100) 0.06 100 (53.33-100) <0.001 100 (46.67-100) <0.001 Role functioning 91.7 (33.3-100) 83.3 (33.3-100) <0.001 100 (50-100) 0.01 100 (50-100) 0.01 100 (33.33-100) 0.02 Social functioning 66.7 (0-100) 66.7 (0-100) 0.71 66.7 (16.7-100) <0.001 100 (33.33-100) <0.001 100 (33.33-100) <0.001 Global health status/QoL 66.7 (33.3-91.7) 54.2 (16.7-100) <0.001 66.7 (33.3-100) <0.001 75 (33.33-91.67) <0.001 83.33 (33.33-91.67) <0.001

12th month 15th month 18th month 24th month P’

Median

(min-max) P (min-max)Median P (min-max)Median P (min-max)Median P

Appetite loss 0 (0-66.7) 0.02 0 (0-66.7) 0.03 0 (0-66.67) 0.19 0 (0-0) 0.04 <0.001 Constipation 0 (0-33.3) 0.03 0 (0-66.7) 0.09 0 (0-66.67) 0.1 0 (0-33.33) 0.01 0.004 Diarrhoea 0 (0-33.3) 0.71 0 (0-66.7) 0.06 0 (0-33.33) 0.32 0 (0-33.33) 0.32 <0.001 Dyspnoea 0 (0-66.7) 0.47 0 (0-66.7) 1 0 (0-33.33) 0.1 0 (0-33.33) 0.08 0.281 Fatigue 0 (0-55.6) 0.03 0 (0-66.7) 0.01 0 (0-66.67) 0.02 0 (0-22.22) <0.001 <0.001 Financial difficulties 0 (0-100) 0.02 0 (0-66.7) 0.01 0 (0-100) 0.14 0 (0-66.67) 0.06 0.013 Insomnia 0 (0-66.7) 0.01 0 (0-66.7) 0.02 0 (0-33.33) 0.03 0 (0-33.33) 0.02 0.009

Nausea and vomiting 0 (0-50) 0.89 0 (0-50) 0.85 0 (0-33.33) 0.41 0 (0-0) 0.08 <0.001

Pain 0 (0-33.3) 0.02 0 (0-66.7) 0.23 0 (0-66.67) 0.2 0 (0-0) 0.03 0.003 Cognitive functioning 100 (66.7-100) 0.12 100 (50-100) 0.39 100 (50-100) 0.53 100 (100-100) 0.04 0.017 Emotional functioning 100 (50-100) <0.001 100 (50-100) <0.001 100 (41.67-100) <0.001 100 (33.33-100) 0.01 <0.001 Physical functioning 100 (46.7-100) 0.02 100 (53.3-100) 0.02 100 (60-100) <0.001 100 (86.67-100) 0.01 <0.001 Role functioning 100 (33.3-100) 0.03 100 (33.3-100) 0.14 100 (50-100) <0.001 100 (100-100) 0.01 <0.001 Social functioning 100 (16.7-100) <0.001 100 (33.3-100) <0.001 100 (16.67-100) 0.02 100 (50-100) <0.001 <0.001 Global health status/

QoL 83.3 (41.7-100) <0.001 83.3 (33.3-100) <0.001 83.33 (41.67-100) <0.001 83.33 (75-91.67) <0.001 <0.001

P=Comparisons of each visit with the basal measurement (Wilcoxon test); P’=Overall comparisons of all visits together (Friedman test)

Table 4: Scores of EORTC QLQ-CX24, comparisons of each assessment with baseline

Basal Post-radiotherapy 3rd month 6th month 9th month

Median

(min-max) (min-max)Median P (min-max)Median P (min-max)Median P (min-max)Median P

Symptom experience 9.1 (0-36.4) 15.2 (0-63.6) <0.001 9.1 (0-39.4) 0.44 6.06 (0-36.36) <0.001 3.03 (0-42.42) <0.001 Body image 100 (33.3-100) 100 (33.3-100) 0.16 100 (44.4-100) 0.31 100 (33.33-100) 0.62 100 (33.33-100) 0.60 Sexual/vaginal functioning 100 (75-100) 50 (0-100) 0.10 66.7 (33.3-100) 0.02 66.67 (41.67-100) 0.03 66.67 (33.33-100) 0.11 Lymphoedema 0 (0-66.7) 0 (0-33.3) <0.001 0 (0-66.7) 0.11 0 (0-33.33) 0.24 0 (0-33.33) 0.67 Peripheral neuropathy 0 (0-66.7) 0 (0-66.7) 0.03 0 (0-66.7) 1.00 0 (0-66.67) 0.61 0 (0-66.67) 0.19 Menopausal symptoms 33.3 (0-100) 33.3 (0-100) 0.91 33.3 (0-100) 0.24 33.33 (0-100) 0.61 33.33 (0-100) 0.26 Sexual worry 0 (0-100) 0 (0-100) 0.16 0 (0-100) 0.06 0 (0-100) 0.24 0 (0-66.67) 0.76 Sexual activity 0 (0-66.7) 0 (0-33.3) 0.13 33.3 (0-66.7) <0.001 33.33 (0-66.67) <0.001 0 (0-66.67) <0.001 Sexual enjoyment 33.3 (0-66.7) 0 (0-33.3) 0.16 33.3 (0-66.7) 0.21 66.67 (0-66.67) 0.19 33.33 (0-100) 0.79

12th month 15th month 18th month 24th month P’

Median

(min-max) P (min-max)Median P (min-max)Median P (min-max)Median P

Symptom experience 4.5 (0-33.3) 0.03 3 (0-54.5) 0.01 0 (0-18.18) <0.001 3.03 (0-15.15) 0.01 <0.001 Body image 100 (55.6-100) 0.79 100 (33.3-100) 0.89 100 (22.22-100) 0.80 88.89 (33.33-100) 0.72 0.494 Sexual/vaginal functioning 66.7 (33.3-100) 0.18 66.7 (41.7-100) <0.001 66.67 (50-100) <0.001 66.67 (58.33-83.33) <0.001 -Lymphoedema 0 (0-33.3) 0.76 0 (0-33.3) 0.71 0 (0-33.33) 1.00 0 (0-33.33) 0.16 0.515 Peripheral neuropathy 0 (0-33.3) 0.21 0 (0-66.7) 1.00 0 (0-66.67) 0.65 0 (0-33.33) 0.56 0.004 Menopausal symptoms 33.3 (0-100) 0.35 33.3 (0-66.7) 0.09 33.33 (0-100) 0.36 33.33 (0-66.67) 0.07 0.075 Sexual worry 0 (0-66.7) 0.75 0 (0-66.7) 0.21 0 (0-66.67) 0.14 0 (0-33.33) 0.09 0.653 Sexual activity 33.3 (0-66.7) <0.001 0 (0-66.7) <0.001 16.67 (0-66.67) 0.01 33.33 (0-66.67) <0.001 <0.001 Sexual enjoyment 33.3 (0-100) 0.32 66.7 (0-100) <0.001 66.67 (33.33-100) <0.001 66.67 (33.33-66.67) <0.001

also correlated with marital status. When the end of RT, 9th and

24th month of RT body image scores were compared with

respect to the marital status; scores were higher for married women (at the end of RT P = 0.04, 9th month of RT P = 0.043,

and 24th month of RT P = 0.03).

Effect of the treatment modality

The patients who underwent chemotherapy had higher peripheral neuropathy scores when compared to the patients who did not at baseline, after RT, and at the end of 3rd and

9th month (baseline P < 0.01, after RT P < 0.01, at the

3rd month P = 0.03, and the 9th month P = 0.04). Moreover,

the emotional function, nausea and vomiting, body image, and symptom experience scores were higher in patients who received chemotherapy at the end of RT (P scores were: P = 0.04 for emotional function and body image; and P = 0.01 for nausea and vomiting and symptom experience). With respect to different chemotherapy regimes in the 1st year results,

the scores in each item were comparable. As the respond rate declined significantly in the 2nd year, the subgroup

analysis in regard to different chemotherapy protocols could not be performed. A subgroup analysis comparing patients undergoing different type of hysterectomies (simple vs. radical) revealed no differences in each item of the questionnaires.

Effect of the tumoral characteristics

The tumor stage deteriorated the baseline body image (P < 0.01), sexual worry (P < 0.01), RF (P = 0.03), PF (P = 0.04), and EF (P = 0.04) scores.

To understand the effect of different tumor histologies (such as cervical or endometrial cancer) better, the data were reanalyzed with respect to tumor type. Besides body image scores, the other parameters were comparable. Body image scores were significantly higher in patients with endometrial cancer, i.e., more women with endometrial cancer were dissatisfied with their body images or perception than the patients with cervical cancer (P < 0.01). Lymphovascular space invasion significantly increased the anxiety and depression scores at the baseline and at 6th, 9th, and

24th month of RT (baseline P = 0.04 and P 0.04 and at the end

of 6th month P < 0.01 and P 0.01, and at the end of 9th month

0.02 and P < 0.01, and at the end of 24th month P < 0.01

and P < 0.01).

Effect of the disease progression

Locoregional recurrent disease and distant metastasis deteriorated global health status scores at the end of 6th, 12th,

and 15th month (6th month P < 0.01 for both and, 12th month

P = 0.03 and P = 0.01 and, 15th month P = 0.01 and P = 0.02).

The depression levels were significantly higher in patients with locoregional recurrent disease and distant metastases at the end of 3rd, 6th, 12th, 15th, and 24th month (3rd month P = 0.01

and P = 0.02, and 6th month P < 0.01 for both, and 12th month

P = 0.03 for both, and 15th month P = 0.01 and P < 0.01, and

24th month P = 0.01 for both). Moreover locoregional recurrent

disease deteriorated emotional function and appetite loss scores after RT, at the end of 12th, 15th, and 24th month (after RT

P < 0.01 and P = 0.03, and 12th month P = 0.04 and P < 0.01,

and P = 0.02 and P = 0.01, and P = 0.01 and P < 0.01. DISCUSSION

In this prospective single‑center study, we evaluated the HRQoL and psychological distress in patients with gynecologic malignancy during 2 years of the follow‑up period. In our preliminary experience, HRQoL deteriorated after RT but improvement during the follow‑up period was observed. The patients who underwent chemotherapy had a higher emotional function, nausea and vomiting, body image, and symptom experience scores. Tumor stage had a negative impact on baseline body image, sexual worry, RF, PF, and EF scores. The anxiety and depression scores were deteriorated after RT but decreased through the subsequent follow‑up visits. Finally, progressive disease had negative impact on global health status and depression levels.

The relationship between sociodemographic factors and HRQoL in patients with gynecologic malignancy has been poorly documented. In this study, we demonstrated that the sexual activity scores were significantly correlated with the marital status of the patients. The sexual activity scores were higher for married women. The body image scores were also significantly correlated with marital status. In parallel to our preliminary report, married women had higher body image scores than unmarried counterparts.

Pelvic RT may be associated with acute and late adverse effects on the GIS and genitourinary tracts. These symptoms may interfere with HRQoL of gynecologic cancer survivors and may cause considerable distress. Pearman reported that HRQoL of gynecologic cancer patients was most negatively affected around the time of diagnosis and treatment.[25]

HRQoL appears to improve over time. At 6–12 months after treatment, there was no difference in overall HRQoL compared to age‑matched controls. Similarly, Wenzel et al. demonstrated that HRQoL in the long‑term was not impaired compared to age‑matched controls for cervical cancer patients.[26] A review Figure 5: Anxiety and depression presence in the patients in each

Yavas, et al.: Radiotherapy and quality of life in gynecologic cancers of the literature of HRQoL of long‑term gynecologic cancer

survivors stated that in general long‑term survivors have a good HRQoL.[27] In our study, we demonstrated that a gradual

decrease was found in symptom scales, and an increase was observed in functional scales and global health status/HRQoL during the follow‑up period.

Vaz et al. demonstrated that sexual activity of the women with the diagnosis of gynecological cancer significantly improved during the follow‑up period.[19] The authors suggested that

improvement in symptoms due to treatment and control of the disease might have explained this improvement. Similarly, Ferrandina et al. documented an improvement of sexual activity over time.[28] Stead et al. proposed that

sexual function in women with gynecologic cancer may be impaired by symptoms such as vaginal discharge, pain, and bleeding.[29] It has been reported that 15% of the women with

endometrial cancer were sexually active before RT and a year after treatment this rose to 39%.[30] Other authors described a

decrease in the percentage of sexually active women after RT, whereas only 63% of these women continued to be sexually active a year after treatment.[31] Our findings were consistent

with previous reports. In our study, sexual activity and sexual enjoyment scores deteriorated in the post‑RT period; however, at 24th month of follow‑up, both of the scores were improved.

In this study, we evaluated the effect of tumoral characteristics on HRQoL. As we demonstrated in our previous study, body image scores were significantly higher in patients with endometrial cancer than the cervical cancer patients. All the patients with endometrial cancer underwent hysterectomy, whereas 53.8% of patients with cervical cancer underwent definitive chemo‑RT. We propose that, although it is unfunctional, living with intact uterus might have effect the patients’ decision about their body image. In studies regarding sexuality after hysterectomy for malignant disease, patients undergoing hysterectomy (either radicalor simple) scored worse with respect to sexuality and perception of body images when compared to controls.[32,33] We hypothesized that sparing

of the uterus could be assumed by the patient as an intact female function, and just the opposite, loss of uterus could be perceived by the woman as the loss of normal female body image as well.

Moreover, the tumor stage deteriorated the baseline body image, sexual worry, RF, PF, and EF scores. The need of adjuvant treatment increases with the advanced tumor stage; therefore, this may deteriorate the HRQoL of the patients. Moreover, emotional function, nausea and vomiting, body image and symptom experience scores were higher in patients who received chemotherapy. This finding also supports our hypothesis.

Major depressive disorder and depressive symptoms occur frequently in patients with cancer. It was estimated that 10–25% of cancer patients suffer from major depressive disorder.[34]

Women are especially prone to develop anxiety and depressive disorders; this may be related to reproductive hormones.[35]

Depressive symptoms are even more prevalent in patients with breast and gynecological cancers.[23,36] Gynecological

cancer represents a challenge to women as they cope with side effects from treatment such as nausea and fatigue, changes in their appearance secondary to chemotherapy and surgery, problems with sexual function and perhaps most importantly, the diagnosis of a potentially lethal disease.[35] Ferrandina et al.

prospectively evaluated the HRQoL and emotional distress in patients with endometrial cancer.[28] The authors used HAD

questionnaires to determine the depression and anxiety. They demonstrated a significant improvement of anxiety scores at the 3‑month of follow‑up. Similarly, in this study, we found that both anxiety and depression levels were significantly higher in basal and after‑RT visits but then decreased through the subsequent follow‑up visits.

Le et al. evaluated the immediate and long‑term effects of chemotherapy on HRQoL of advanced ovarian cancer patients.[37] Their results suggested that there were significant

differences in favor of patients with complete responders compared to those with partial response or progressive disease in the mean overall HRQoL scores as well as physical, emotional, functional, and concern domains mean scores. Capelli et al. evaluated the feasibility of measuring HRQoL in patients with either endometrial or cervical carcinoma.[38]

They demonstrated a significant 10‑point mean decrease in every SF‑36 scale for patients with progressive/recurrent disease. A biologic interaction among cervical carcinoma, age, and disease status was demonstrated in multivariate models showing worst scores for patients with progressive/ recurrent cervical carcinoma on almost all scales. In this study, locoregional recurrent disease and distant metastasis deteriorated global health status, emotional function, and appetite loss scores. In addition, the depression levels were significantly higher in patients with locoregional recurrent disease and distant metastases.

This study was not a part of the clinical trial setting, and the questionnaires were administered as a part of routine follow‑up; therefore, we did not meet with any problems during the data collection. Our patients had no difficulty during answering the questionnaires. We evaluated the HRQoLs and psychological distresses of our patients’ routinely; we also observed their needs closely from the medical, psychiatric, and social aspect.

Despite some weaknesses of our study including a certain degree of patient and treatment heterogeneity and lack of a control population, our findings seem to provide useful information about HRQoL of the patients with gynecologic malignancies. Moreover, heterogeneity of the different treatment modalities such as different chemotherapy regimes in cervical and endometrial cancers and also different surgical therapies such as simple versus radical hysterectomy could

lead to bias in this study. In further analysis, there seems to be no difference in these subgroups. Our study was designed to assess QoL with more general, global health scales. Detailed analysis with special questionnaires assessing pelvic neurologic functions of bladder and bowel could be scope of another study with probably different end‑points and results. Another point is the inclusion of the patients receiving brachytherapy to study group. This could be another limitation of the study, however, the main aim of this study was to evaluate the overall effect of RT on QoL. QoL studies with patients with different RT protocols in the same group were assessed to evaluate the impact of malignancy and RT on global health status.[39,40]

Our 2‑year follow‑up results in gynecological cancer patients revealed that no significant adverse long‑term effect on patients’ overall HRQoL resulted from RT. The acute worsening of HRQoL during the treatment phase had significantly improved with long‑term follow‑up. Complete disease remission remained important in maintaining improved HRQoL.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest. REFERENCES

1. van der Aa MA, Schutter EM, Looijen‑Salamon M, Martens JE, Siesling S. Differences in screening history, tumour characteristics and survival between women with screen‑detected versus not screen‑detected cervical cancer in the east of The Netherlands, 1992‑2001. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol 2008;139:204‑9. 2. Carter J, Sonoda Y, Chi DS, Raviv L, Abu‑Rustum NR. Radical

trachelectomy for cervical cancer: Postoperative physical and emotional adjustment concerns. Gynecol Oncol 2008;111:151‑7. 3. Eryilmaz MA, Eroglu C, Arslan K, Selvyi Y, Civcik S. The interaction

of mastalgia with depression and quality of life in Turkish women. J Clin Anal Med 2014;5:113‑8.

4. Vistad I, Fosså SD, Dahl AA. A critical review of patient‑rated quality of life studies of long‑term survivors of cervical cancer. Gynecol Oncol 2006;102:563‑72.

5. Chase DM, Watanabe T, Monk BJ. Assessment and significance of quality of life in women with gynecologic cancer. Future Oncol 2010;6:1279‑87. 6. Juraskova I, Butow P, Robertson R, Sharpe L, McLeod C, Hacker N.

Post‑treatment sexual adjustment following cervical and endometrial cancer: A qualitative insight. Psychooncology 2003;12:267‑79. 7. Korfage IJ, Essink‑Bot ML, Mols F, van de Poll‑Franse L, Kruitwagen R,

van Ballegooijen M. Health‑related quality of life in cervical cancer survivors: A population‑based survey. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys 2009;73:1501‑9.

8. Hazewinkel MH, Sprangers MA, van der Velden J, van der Vaart CH, Stalpers LJ, Burger MP, et al. Long‑term cervical cancer survivors suffer from pelvic floor symptoms: A cross‑sectional matched cohort study. Gynecol Oncol 2010;117:281‑6.

9. Hsu WC, Chung NN, Chen YC, Ting LL, Wang PM, Hsieh PC, et al. Comparison of surgery or radiotherapy on complications and quality of life in patients with the stage IB and IIA uterine cervical cancer. Gynecol Oncol 2009;115:41‑5.

10. Pieterse QD, Maas CP, ter Kuile MM, Lowik M, van Eijkeren MA, Trimbos JB, et al. An observational longitudinal study to evaluate miction, defecation, and sexual function after radical hysterectomy with pelvic lymphadenectomy for early‑stage cervical cancer. Int J Gynecol Cancer 2006;16:1119‑29.

11. Vistad I, Cvancarova M, Fosså SD, Kristensen GB. Postradiotherapy morbidity in long‑term survivors after locally advanced cervical cancer: How well do physicians’ assessments agree with those of their patients? Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys 2008;71:1335‑42. 12. Maher EJ, Denton A. Survivorship, late effects and cancer of the

cervix. Clin Oncol (R Coll Radiol) 2008;20:479‑87.

13. Erekson EA, Sung VW, DiSilvestro PA, Myers DL. Urinary symptoms and impact on quality of life in women after treatment for endometrial cancer. Int Urogynecol J Pelvic Floor Dysfunct 2009;20:159‑63. 14. Barker CL, Routledge JA, Farnell DJ, Swindell R, Davidson SE. The

impact of radiotherapy late effects on quality of life in gynaecological cancer patients. Br J Cancer 2009;100:1558‑65.

15. Yavas G, Dogan NU, Yavas C, Benzer N, Yuce D, Celik C. Prospective assessment of quality of life and psychological distress in patients with gynecologic malignancy: A 1‑year prospective study. Int J Gynecol Cancer 2012;22:1096‑101.

16. Lutgendorf SK, Anderson B, Ullrich P, Johnsen EL, Buller RE, Sood AK, et al. Quality of life and mood in women with gynecologic cancer: A one year prospective study. Cancer 2002;94:131‑40.

17. Caffo O, Amichetti M, Mussari S, Romano M, Maluta S, Tomio L, et al. Physical side effects and quality of life during postoperative radiotherapy for uterine cancer. Prospective evaluation by a diary card. Gynecol Oncol 2003;88:270‑6.

18. Vaz AF, Pinto‑Neto AM, Conde DM, Costa‑Paiva L, Morais SS, Esteves SB. Quality of life and acute toxicity of radiotherapy in women with gynecologic cancer: A prospective longitudinal study. Arch Gynecol Obstet 2008;278:215‑23.

19. Vaz AF, Pinto‑Neto AM, Conde DM, Costa‑Paiva L, Morais SS, Pedro AO, et al. Quality of life and menopausal and sexual symptoms in gynecologic cancer survivors: A cohort study. Menopause 2011;18:662‑9. 20. Honda K, Goodwin RD. Cancer and mental disorders in a national

community sample: Findings from the national comorbidity survey. Psychother Psychosom 2004;73:235‑42.

21. Cankurtaran ES, Ozalp E, Soygur H, Ozer S, Akbiyik DI, Bottomley A. Understanding the reliability and validity of the EORTC QLQ‑C30 in Turkish cancer patients. Eur J Cancer Care (Engl) 2008;17:98‑104. 22. Greimel ER, Kuljanic Vlasic K, Waldenstrom AC, Duric VM, Jensen PT,

Singer S, et al. The European organization for research and treatment of cancer (EORTC) quality‑of‑life questionnaire cervical cancer module: EORTC QLQ‑CX24. Cancer 2006;107:1812‑22.

23. Kissane DW, Clarke DM, Ikin J, Bloch S, Smith GC, Vitetta L, et al. Psychological morbidity and quality of life in Australian women with early‑stage breast cancer: A cross‑sectional survey. Med J Aust 1998;169:192‑6.

24. Aydemir O, Guvenir T, Kuey L, Kultur S. Validity and Reliability of Turkish Version of Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale. Turk Psikiyatri Derg 1997;8:280‑7.

25. Pearman T. Quality of life and psychosocial adjustment in gynecologic cancer survivors. Health Qual Life Outcomes 2003;1:33.

26. Wenzel L, DeAlba I, Habbal R, Kluhsman BC, Fairclough D, Krebs LU, et al. Quality of life in long‑term cervical cancer survivors. Gynecol Oncol 2005;97:310‑7.

27. Gonçalves V. Long‑term quality of life in gynecological cancer survivors. Curr Opin Obstet Gynecol 2010;22:30‑5.

28. Ferrandina G, Petrillo M, Mantegna G, Fuoco G, Terzano S, Venditti L, et al. Evaluation of quality of life and emotional distress in endometrial cancer patients: A 2‑year prospective, longitudinal study. Gynecol Oncol 2014;133:518‑25.

29. Stead ML, Fallowfield L, Selby P, Brown JM. Psychosexual function and impact of gynaecological cancer. Best Pract Res Clin Obstet Gynaecol 2007;21:309‑20.

Yavas, et al.: Radiotherapy and quality of life in gynecologic cancers 30. Nout RA, Putter H, Jürgenliemk‑Schulz IM, Jobsen JJ, Lutgens LC, van

der Steen‑Banasik EM, et al. Quality of life after pelvic radiotherapy or vaginal brachytherapy for endometrial cancer: First results of the randomized PORTEC‑2 trial. J Clin Oncol 2009;27:3547‑56. 31. Jensen PT, Groenvold M, Klee MC, Thranov I, Petersen MA, Machin D.

Longitudinal study of sexual function and vaginal changes after radiotherapy for cervical cancer. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys 2003;56:937‑49.

32. Serati M, Salvatore S, Uccella S, Laterza RM, Cromi A, Ghezzi F, et al. Sexual function after radical hysterectomy for early‑stage cervical cancer: Is there a difference between laparoscopy and laparotomy? J Sex Med 2009;6:2516‑22.

33. Jensen PT, Groenvold M, Klee MC, Thranov I, Petersen MA, Machin D. Early‑stage cervical carcinoma, radical hysterectomy, and sexual function. A longitudinal study. Cancer 2004;100:97‑106.

34. Pirl WF. Evidence report on the occurrence, assessment, and treatment of depression in cancer patients. J Natl Cancer Inst Monogr 2004;(32):32‑9.

35. Thompson DS, Shear MK. Psychiatric disorders and gynecological

oncology: A review of the literature. Gen Hosp Psychiatry 1998;20:241‑7. 36. Bodurka‑Bevers D, Basen‑Engquist K, Carmack CL, Fitzgerald MA, Wolf JK,

de Moor C, et al. Depression, anxiety, and quality of life in patients with epithelial ovarian cancer. Gynecol Oncol 2000;78 (3 Pt 1):302‑8. 37. Le T, Hopkins L, Fung Kee Fung M. Quality of life assessments in

epithelial ovarian cancer patients during and after chemotherapy. Int J Gynecol Cancer 2005;15:811‑6.

38. Capelli G, De Vincenzo RI, Addamo A, Bartolozzi F, Braggio N, Scambia G. Which dimensions of health‑related quality of life are altered in patients attending the different gynecologic oncology health care settings? Cancer 2002;95:2500‑7.

39. Kim SI, Lim MC, Lee JS, Lee Y, Park K, Joo J, et al. Impact of lower limb lymphedema on quality of life in gynecologic cancer survivors after pelvic lymph node dissection. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol 2015;192:31‑6.

40. Berretta R, Gizzo S, Noventa M, Marrazzo V, Franchi L, Migliavacca C, et al. Quality of life in patients affected by endometrial cancer: Comparison among laparotomy, laparoscopy and vaginal approach. Pathol Oncol Res 2015;21:811‑6.