SOSYAL BİLİMLER ENSTİTÜSÜ

YABANCI DİLLER EĞİTİMİ ANABİLİM DALI İNGİLİZCE ÖĞRETMENLİĞİ BİLİM DALI

THE USE OF PROJECT BASED LEARNING IN TEACHING ENGLISH TO YOUNG LEARNERS

Yüksek Lisans Tezi

Danışman

Yrd. Doç. Dr. Ece SARIGÜL

Hazırlayan Duygu ÇIRAK

ACKNOWLEDGEMENT

I would like to express my gratitude to all those who have supported and guided me in this thesis but most of all to Assist. Prof. Dr. Ece Sarıgül for her enduring advice and patience from the very beginning to the end. I would also like to extend my appreciation to Assist. Prof. Dr. Hasan ÇAKIR, Assist. Prof. Dr. A.Kadir ÇAKIR, A.Hamit ÇAKIR and Assist. Prof. Dr. Ahmet Ali ARSLAN, for their invaluable comments.

I am thankful to Assist. Prof. Dr. Ali Murat Sünbül for his suggestions and guidance. I am also thankful to the school manager, teachers and especially the students of TED Isparta College. I also would like to thank to my friend and colleague Mrs.Berna İçigen.

Thanks to Mehmet Bardakçı for supporting my thesis.

My thanks are due to my husband who supported me with his patience and understanding throughout my work on this thesis.

ABSTRACT

The purpose of this study is to investigate ‘the use of project based learning in teaching young learners’ achievement level in English lessons. This study also provides an opportunity to show that the students do not forget the things they learn by doing.

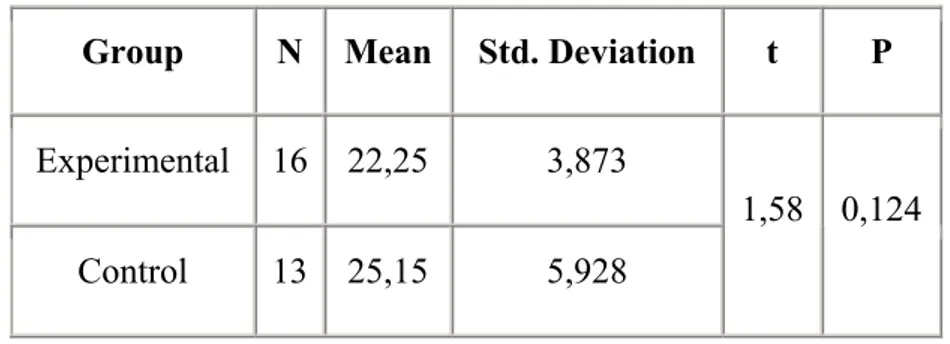

The study has been carried out on two groups, experimental and control, including 29 students. In the experimental group, the lesson has been taught by doing project, and the teacher has taught the unit by using traditional teaching methods in the control group. Teaching activities have been carried out by the researcher. Both of the groups have been pre-tested at the beginning and post-tested at the end of the study and the data has been analysed by t-test.

In the first chapter, the general background to the study, the goal and scope of the study, the statement of the problem and method of the study are introduced.

The next chapter gives information about the characteristics of young learners, Child’s Language Environment, Child’s Learning Styles, Child’s Learning Strategies, and Language Development in Child. Namely, this chapter allows knowing about the young learners.

The third chapter includes the child’s acqusition stages, English teaching methods and four basic language skills.

Fourth chapter mentions about the new trends in “Teaching English to Young Learners”, and “Multiple Intelligence”.

In the fifth chapter, what is PBL and the importance of Project based learning and how it works in class is introduced.

In the sixth chapter, the experimental study is explained and the results of the study are given through the interpretation of tables.

ÖZET

Bu çalışmanın amacı, “çocuklara yabancı dil öğretiminde proje tabanlı öğrenmenin faydaları”nın İngilizce derslerindeki başarı düzeyinin araştırılmasıdır. Bu çalışma aynı zamanda, çocukların yaparak öğrendikleri şeyleri unutmadıklarının gösterilmesi için bir fırsattır.

Bu çalışma, deney ve kontrol grupları olmak üzere toplam 29 öğrenci üzerinde yürütülmüştür. Konu, deney grubunda proje yapılarak, kontrol grubunda ise geleneksel öğretim kullanılarak anlatılmıştır. Öğretim faaliyetleri araştırmacı tarafından yürütülmüştür. Her iki grup da uygulama başında ön-test, uygulama sonunda ise son-test ile değerlendirilmiştir ve veriler t-son-testi ile analiz edilmiştir.

İlk bölümde, çalışma ile ilgili ön bilgi, çalışmanın amacı, problemin belirlenmesi ve çalışmada kullanılan metot belirlenmiştir.

Sonraki bölüm, çocukların karakterleri, çocuğun dil çevresi, çocuğun öğrenme stili, çocuğun öğrenme stratejileri ve çocuktaki dil gelişimi ile ilgili bilgi vermektedir. Yani, bu bölüm, çocukları tanımamıza izin verir.

Üçüncü bölüm, çocuğun dil edinim aşamalarını, İngilizce öğretim metotlarını ve dört temel dil becerilerini içermektedir.

Dördüncü bölüm, “Çocuklara İngilizce Öğretimi”ndeki yeni trendler ve “Çoklu Zeka”dan bahsetmektedir.

Beşinci bölümde, Proje Tabanlı Öğrenmenin ne olduğu ve Proje Tabanlı Öğrenmenin önemi ile sınıfta nasıl uygulanacağı anlatılmıştır.

Altıncı bölümde, deneysel çalışma açıklanmış ve sonuçlar tablo yorumları ile birlikte verilmiştir.

LIST OF TABLES

Table 2.1: Piaget’s Stages of Cognitive Development………...18

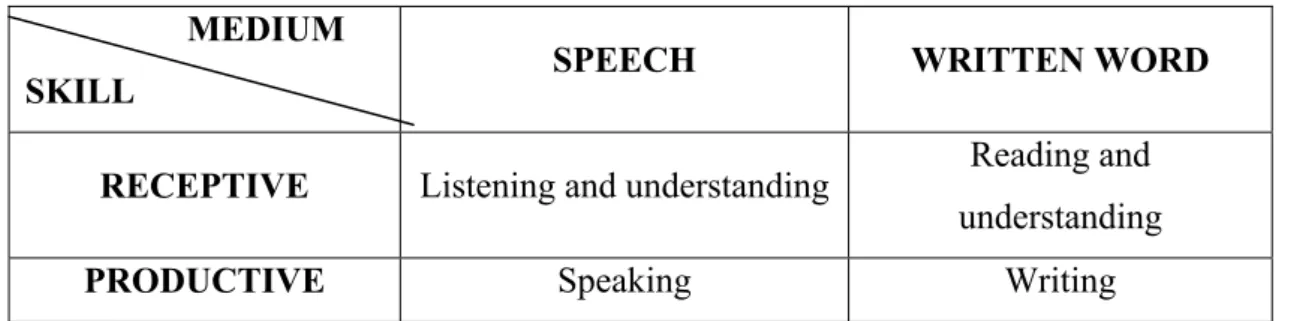

Table 3.1: The Four Language Skills………..47

Table 6.1: Group Statistics of Pre-test ………91

Table 6.2: The Comparison of Experimental and Control Groups Students’ post-tests………..92

Table 6.3: Comparison of Experimental and Control Groups Students’ achievement scores ……….92

LIST OF FIGURES

Figure 3.1: “Avarage” order of acquisition of gramatical morphemes for English

as a second language (children and adults) .…..………...………..28

Figure 3.2: Acquisition and learning in second language production …...…….29

Figure 3.3: Operation of the “Active Filter” ………...40

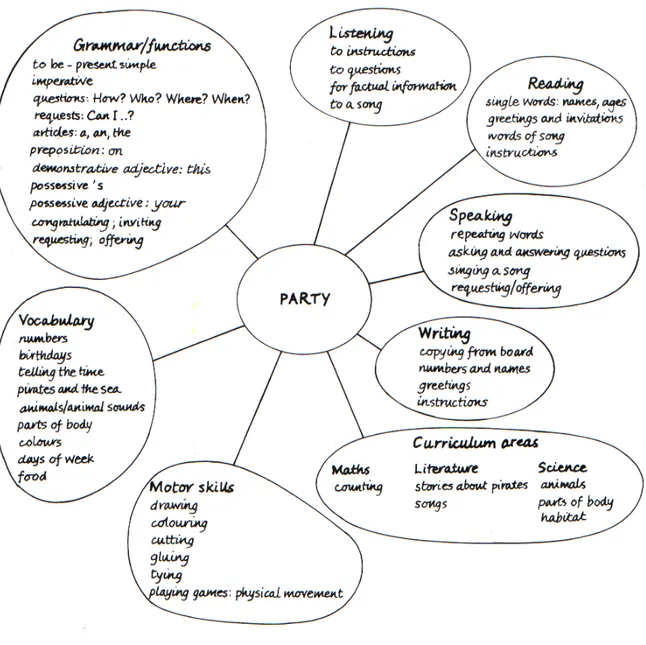

Figure 5.1: A Project Web Sample ……...………..76

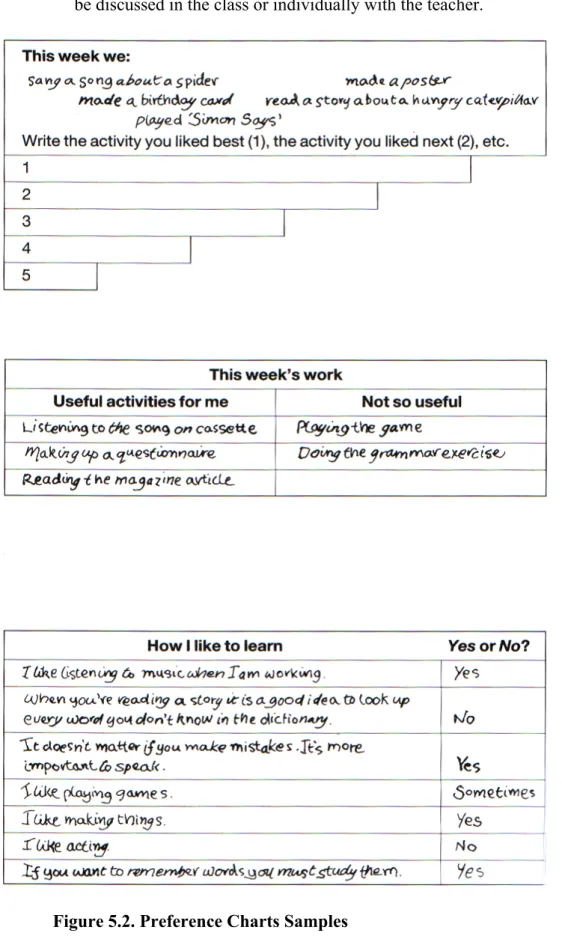

Figure 5.2: Preference Charts Samples ………...………81

TABLE OF CONTENTS ACKNOWLEDGEMENT...İ ABSTRACT... İİ ÖZET ...İV LIST OF TABLES ... V LIST OF FIGURES ...Vİ TABLE OF CONTENTS ... Vİİ INTRODUCTION ... 1

1.1. General Background to the Study... 1

1.2. Goal and Scope of the Study ... 2

1.3. Statement of the Problem... 3

1.4. Method of the Study ... 4

LANGUAGE AND CHILDREN ... 5

2.0. The Characteristics of Young Learners... 5

2.1. Child’s Development Areas... 7

2.2. The Child’s Language Environment... 10

2.3. Child Learning Styles and Strategies... 11

2.3.1. Child’s Learning Styles ... 11

2.3.2. Child’s Learning Strategies ... 16

2.4. Language Development in Child ... 17

LANGUAGE LEARNING AND TEACHING ... 21

3.0. First Language Acquisition... 21

3.1. Second Language Acquisition / Learning... 23

3.1.1. Acquisition – Learning Distinction ... 25

3.1.2. Natural Order Hypothesis... 26

3.1.3. The Monitor Hypothesis... 28

3.1.4. Input Hypothesis... 32

3.1.4.1. Statement of Hypothesis... 33

3.1.4.2. Evidence Supporting The Hypothesis... 34

3.1.5. The Affective Filter Hypothesis... 39

3.2.1. The Grammar Translation Method ... 41

3.2.2. The Direct Method... 42

3.2.3. Audio Lingual Method ... 42

3.2.4. The Silent Way ... 43

3.2.5. Suggestopedia ... 44

3.2.6. Community Language Learning ... 44

3.2.7. The Total Physical Response Method ... 45

3.2.8. The Communicative Approach... 46

3.3. Four Basic Language Skills and Teaching Them in EFL Classrooms... 46

3.3.1. Listening ... 48

3.3.2. Reading ... 51

3.3.3. Speaking... 52

3.3.4. Writing... 54

3.3.5. Integrating Skills... 56

ENGLISH LANGUAGE TEACHING FOR YOUNG LEARNERS ... 58

4.0. Teaching Young Learners versus Adults... 59

4.1. The Popularity of Teaching Young Learners... 60

4.2. Making Use of Multiple Intelligence Theory... 62

4.3. Teaching Young Learners is not Everybody’s Cup of Tea... 65

PROJECT BASED LEARNING AND TEACHING ... 68

5.0. The History of Project Based Learning ... 68

5.1. Defining Standards- Focused PBL ... 69

5.2. Project Work ... 70

5.3. Project Based Learning in the Classroom ... 71

5.3.1. Individual Work... 73

5.3.2. Group Work ... 73

5.4. Planning the Project ... 75

5.5. Advantages of Project Based Learning in Teaching Young Learners... 83

5.6. Some possible drawbacks to Project Work ... 86

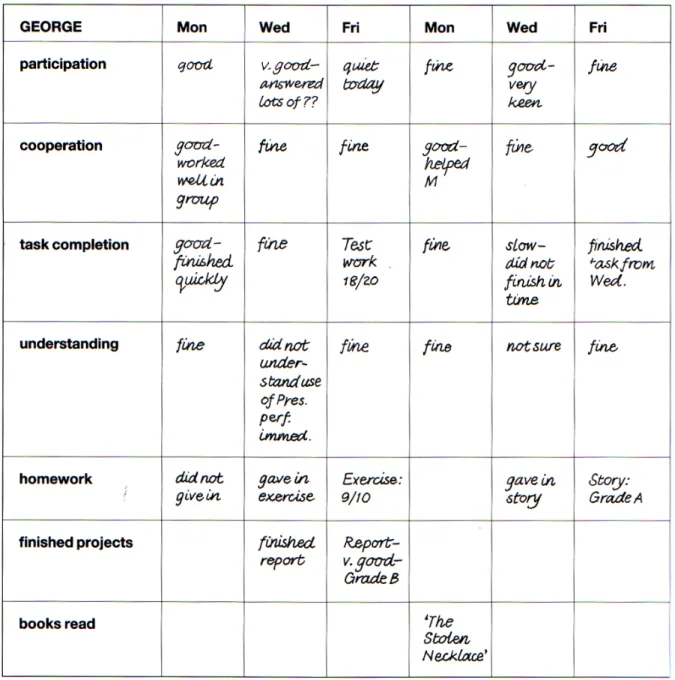

METHOD OF DATA COLLECTION, ANALYSIS AND INTERPRETATION OF THE RESULTS... 88

6.1. Subjects ... 88

6.2. Procedures ... 88

6.2.1. Assessment Instruments ... 89

6.2.2. Treatment ... 90

CONCLUSION ... 94

Summary and Findings ... 94

Suggestions ... 95 BIBLIOGRAPHY... 97 WEB BIBLIOGRAPHY... 100 APPENDICES... 101 Appendix I ... 101 Appendix II... 103 Appendix III ... 104 Appendix IV ... 105 Appendix V... 106 Appendix VI ... 106 Appendix VII... 107 Appendix VIII ... 108 Appendix IX ... 108 Appendix X... 109 Appendix XI ... 110 Appendix XII... 111

CHAPTER I

INTRODUCTION 1.1. General Background to the Study

Over last decade in English Language Teaching for Young Learners became popular (1990- 200). The age of learning foreign languages become lower and teaching English young learners became very popular trend. So there are many methods and techniques and materials for teaching English to young learners

Teaching young learners differs from teaching teenagers and adults according to their needs, expectations, learning style and strategies, interests, psychological and cognitive development. Young learners are considered as kinesthetic learners, thus they can easily get bored, and lose their interest, they do not like just sitting and listening to their teacher.

Lynne Cameron states these differences like that; Children often are more enthusiastic and lively as learners. They want to please the teacher rather than their peer group. They will have a go at an activity even when they do not understand why or how. However they also lose interest more quickly and are less able to keep themselves motivated on task they find difficult. Children do not find it as easy to use language to talk about the language; in other words, they do not have the same access as older learners to metalanguage that teachers can use to explain about grammar or discourse. Children seem less embarrassed than adults at taking in a new language, and their lack of inhibition seems to help them to get a more native like accent.

Children can not concentrate on something more than fifteen minutes, so they quickly lose their interest on that subject and at that time teachers should give them a break or do different activities. According to Holden (1980:7):

…young children’s moods seem to change much more quickly than those of older children. One day a whole class will be subdued and

inward looking, while the next they will be physically active, finding it difficult to sit still or refrain from wandering around the classroom. Individual children also seem to go through ‘personality passes’: a sociable child will become aloof for a few months, and a well behaved one will suddenly start acting as a bad temper. The teacher needs to be alive to these moods and able to choose the right kind of activities for a particular day. Ideally, too, the teacher should be able to match the length and frequency of lessons to interest and mood of the children. …. The ideal arrangement would seem to be about 30 minutes of language learning everyday, rather than a rigid hour or hour and a half twice a week.

Namely, teaching young learners is different from teaching adults. The teachers should choose different methods, techniques and material when teaching these learners. Because; their characteristics, their learning styles and strategies, their development and the many other things are different.

On the other hand childhood is a relatively short time in the life of a human being yet it is crucial to the adult we become. It is a time of curiosity, testing, learning about one-self and place in the world; a time of learning about the other people and relationships; a time of learning about social mores and norms and these values are often learned during social interaction and plays. So the teacher of young learners should be aware of the child needs first and create an atmosphere to fulfill his or her needs.

1.2. Goal and Scope of the Study

The goal of this study is to investigate the effects of using projects on the achievements of primary schools students.

The uses of projects are of great importance in learning/teaching a foreign language. First of all, it fulfils his or her basic needs such as socialization, fun and play… They learn to cooperate and sharing. They have opportunity to use target

language. As they learn by doing (hands – on experiences) they do not forget it quickly. And the most important thing is they have fun when they are learning.

This study also aims to provide foreign language teachers with a scope of language teaching through the use of projects by discussing the general features, characteristics, needs and expectations of young learners.

The following assumptions will be considered throughout this study:

1. The young learners may learn better by use of projects prepared or chosen because young learners learn by experiencing and they are completely different from adults.

2. Teaching a foreign language to young learners through traditional methods is not effective but boring. Since their attention span is short, different short activities can be applied by using projects.

1.3. Statement of the Problem

In recent years, foreign language teaching to young children has become more and more important all over the world, with an increasing number of countries started to introduce foreign language to students in the primary school ages. The importance of learning a foreign language at early ages is perceived and English lessons were put into the primary school curriculum in our country in the late 1990s. It is a really popular trend and so there are now many materials and activities to be use in classes.

Teaching young learners should be different from teaching adults. As the children learn by doing and hands- on experiences the children should be given opportunity to experiences with the language and should be let to do in order to learn. The kinds of activities that work well are games and songs with actions, total physical response activities, tasks that involve colouring, and sticking, projects repetitive stories, and simple, repetitive speaking activities that have an obvious communicative value.

There are many different views about teaching a foreign language to children but generally researchers agree that lessons in primary schools should be activity based. As children’s concentration changes rapidly the teacher should plan the lessons that the student are active, they are moving and doing. The teachers aim should be make the student not the learners of the language but the users.

1.4. Method of the Study

For this experimental study, it was necessary to learn the subject and then prepare a pre-test accordingly. This pre-test was applied to students attending another school who were also at the same age and level. The reliability of the pre-test was measured by Associate Prof. Dr. Ali Murat SÜNBÜL. Secondly, students were divided into two groups as experimental and control groups, and both groups are given a pre-test using a proficiency test consisting of seven different parts including 40 questions related to the subject. Lastly, the researcher taught the subject following the curriculum of the experimental group. The control group was taught according to traditional teaching methods by their own teacher and the experimental group was taught by using project based learning by the researcher. This study process took four weeks (two hours for each week). After the teaching period, students in both groups were given a post-test.

In conclusion, the purpose of this study is to evaluate the efficiency of using language teaching materials on the achievement level of primary school students in learning English.

CHAPTER II

LANGUAGE AND CHILDREN

2.0. The Characteristics of Young Learners

This section aims to give information about the child, his language development and his learning styles and strategies. First, we will look at the characteristics of young learners so we can see the characteristics distinctions between the adults and children so we can choose the best method and behaviours to them according to their characteristics and we can see their interest.

Scott and Ytreberg has (1990:1) divided the children into two main groups: “the five to seven year olds and the eight to ten year olds”. They also assume that the five to seven year olds are at level one, the beginner stage, and the eight to ten year olds that may learn the foreign language, but in the eight to ten year old age group there can be pupils who are at the level one. They list what five to seven year olds can do at their level as in the following:

• They can talk about what they are doing.

• They can tell you about what they have done or heard. • They can plan activities.

• They can argue for something and tell you why they think what they think. • They can use logical reasoning.

• They can use their vivid imaginations.

• They can use a wide range of intonation patterns in their mother tongue. • They can understand direct human interaction.

• They know that the world is governed by rules. They may not always understand the rules, but they know that they are there to be obeyed, and the rules help to nurture a feeling of security.

• They understand situations more quickly than they understand the language used.

• They use language skills long before they are aware of them.

• Their own understanding comes through hands, eyes, and ears. The physical world is dominant all times.

• They are very logical- what you say first happens first. “Before you turn of the light, put your book away” can mean 1 turn of the light then 2 put your book away.

• They have a very short attention and concentration span.

• Young children sometimes have difficulty in knowing what fact is and what fiction is. The dividing line between the real world and the imaginary world is not clear.

• Young children are often happy playing and working alone but in the company of others. They can be very reluctant to share.

• The adult world and the child’s world are not the same. Children do not always understand what adults are talking about. The difference is that adults usually find out by asking questions, but children do not always ask. They either pretend to understand, or they understand in their own terms and do what they think you want them to do.

• They will seldom admit that they do not know something either. • Young children cannot decide for themselves what to learn.

• Young children love to play, and learn best when they are enjoying themselves. But they also take themselves seriously and like to think that what they are doing is “real” work.

• Young children are enthusiastic and positive about learning. To keep their enthusiasm, it is important to praise them if they are successful.

The five to seven year olds are little children. Eight to ten year olds are somewhat mature children with an adult side and a childish side. Their understandings will change in the second period. They list the characteristics of eight to ten year olds as follows:

• Their basic concepts are formed. They have very decided views of the world. • They can tell the difference between fact and fiction.

• They ask questions all the time.

• They rely on the spoken word as well as the physical world to convey and understand meaning.

• They are able to make some decisions about their own learning. • They have definite views about what they like and do not like doing.

• They have a developed sense of fairness about what happens in the class – room and begin to question the teacher’s decisions.

• They are able to work with others and learn from others.

In the light of this information, not the teacher but the parents also can adopt the best attitude to their pupils and children. If do they know the characteristics of the child, they can help the child to improve his developmental areas that we will mention next part. They can understand them better so the period of childhood that is crucial to the adult we become may be joyful and fruitful for the parents, the teachers and for the child.

As Gardner states that the most remarkable features of the young mind – its adventurousness, its generativity, its resourcefulness and its flashes of flexibility and creativity. So as teachers and parents our role is enormous because child’s characteristics are so suitable to be best shaped.

2.1. Child’s Development Areas

Child development is a process every child goes through. This process involves learning and mastering skills like sitting, walking, talking, skipping, and tying shoes. Children learn these skills, called development milestones, during the predictable time periods. A developmental milestone is a skill that a child acquires within a specific time frame. For instance, one development milestone is learning to walk. Milestones develop in a sequential fashion. This means that, a child will need to develop some skills before he or she can develop new skills. For example; children must firs learn to crawl and to pull up to a standing position before they are able to walk. Each milestone that a child acquires, build on the last milestone.

Children develop skills in five main areas:

1. Cognitive Development: This is the child’s ability to learn and solve problems. For example, this includes a two – month – old baby learning to explore the environment with hands or eyes or a five – year – old learning how to do simple math problems.

2. Social and Emotional Development: This is the child’s ability to interact with others, including helping themselves and self-control. Example of this type of development would include; a six – week – old baby smiling, a ten – month – old baby waving bye – bye, or a five – year – old boy knowing how to take turns in games at school.

3. Speech and Language Development: This is the child’s ability to both understand and use the language. For example, this includes a 12 – month – old baby saying his first words, a two – year – old naming parts of her body, or a five – year – old learning to say “feet” instead of “foots”

4. Fine Motor Skill Development: This is the child’s ability to use muscles, specifically their hands and fingers, to pick up small objects, hold a spoon, turn pages in a book, or to use a crayon to draw.

5. Gross Motor Skill Development: This is the child’s ability to use large muscles. For example, a six – month – old baby learns how to sit up with some support, a 12 – month – old baby learns to pull up to a stand holding onto furniture, and five – year – old learns to skip.

The child develops these skills together. But, each child is an individual and may meet developmental milestones a little earlier or later than his peers. You may have heard people say these things like, “he was walking before he turned 10 months, much earlier than his brother “or “she didn’t say much until she was about 2 years old and

then she talked a blue streak!” This is because each child is unique and will develop at his or her own pace.

However, there are definitely blocks of time when most children will meet a mile stone. For example, children learn to walk anytime between 9 and 15 months of age.

Some takes this stages of development differently:

1. Physical Development: The changes in size, shape, and physical maturity of the body, including physical abilities and coordination.

2. Intellectual Development: The learning and the use of language; the ability to reason, problem-solve, and organize ideas; it is related to the physical growth of the brain.

3. Social Development: The process of gaining the knowledge and skills needed to be interacted successfully with others.

4. Emotional Development: Feelings and emotional responses to events; changes in understanding one’s own feelings and appropriate forms of expressing them.

5. Moral Development: The growing understanding of right and wrong, and the change in behaviour caused by that understanding; sometimes called a conscience.

Whatever they call these development skills they are similar. The most important development skills that is related with my study is intellectual development, this part is revised in the next to parts titled Child’s Language Development.

As all we know the brain grows rapidly during the first seven years of life. During this period, the child learns all new skills and develops them. Thus, this period

of life is so important in human. The parents and the teachers should make attempt to help the child to develop these skills. They should watch the child carefully but they should not forget that each child is unique.

2.2. The Child’s Language Environment

In this part, we will describe ten most important to features of a child’s language environment in order to look at his/ her world closely. Below are some features of child’s language environment taken from McGlothin’s article (2001:6).

First; there is no pressure to bear upon the child as he/ she learns the language. There are no test and grade.

Second; there is all the time a need to learn the language to express the needs.

Third; there is no possibility of escaping into a language that the children already know.

Fourth; the language a child hears is not sequenced by grammar or vocabulary. Parents do not use a textbook or a word frequency study to help them to decide how to speak to their children.

Fifth; there is lots of repetition around them, as the daily life contains lots of repetition.

Sixth; Both the words and the world around the child are new. So the curiosity that he/she has towards the world becomes a powerful force to learn the language.

Seventh; All the language is spoken in the context of the world around him/her. Namely; the language that he/she is learning is related directly the world around him/her. It is always presented as a living language.

Eight; the child has lots of opportunities to listen to the new language as it is spoken by native speakers.

Ninth; the language environment of a child gives him many opportunities to listen to the new language and to be understood.

Tenth; much of the language he/she hears is simplified especially for him/her.

As we see in the list above the child’s language environment is really rich. There is a natural environment that helps the child.

2.3. Child Learning Styles and Strategies

2.3.1. Child’s Learning Styles

Ellis (1985) described a learning style as the more or less consistent way in which a person receives, conceptualizes, organizes, and recall information. The child’s learning style will be influenced by his or her generitic make-up, their previous learning experiences, their culture and society he or she lives in.

There are many ways of looking at learning styles. First we will look at four modalities originates from the work of Dr’s Bandler, R. and Grinder, J., in the field of Neuro-Linguistic Programming. Then McCarthy’s four learning styles, then Field independent vs. Field dependent learning style and then Left brain vs. Right brain dominated learning styles:

Four Modalities:

Some may prefer a visual (seeing), auditory (hearing), kinesthetic (moving) or tactile (touching).

• Those who prefer a visual learning style ... ... look at the teacher’s face intently ... like looking at wall displays, books etc. ... often recognize words by sight

... use lists to organize their thoughts

... recall information by remembering how it was set out on a page

• Those who prefer an auditory learning style ... ... like the teacher to provide verbal instructions ... like dialogues, discussions and plays

... solve problems by talking about them ... use rhythm and sound as memory aids

• Those who prefer a kinesthetic learning style ... ... learn best when they are involved or active ... find it difficult to sit for long periods ...use movement as memory aid

• Those who prefer a tactile way of learning ... ... use writing and drawing as memory aids

... learn well in hands-on activities like projects and demonstrations

McCarthy’s Four Learning Styles:

McCarthy (1980) described students as innovate learners, analytic learners, common sense learners or dynamic learners.

• Innovate learners...

... look for personal manning while learning ... draw on their values while learning ... enjoy social interaction

... are cooperative

... want to make the world a better place

• Analytic learners...

... want to develop intellectuality while learning ... draw on facts while learning

... are patient and reflective

... want to know “important things” and to add to the world’s knowledge

• Common sense learners... ... want to find solutions

... value things if they are useful ... are Kinesthetic

... are practical and straightforward

• Dynamic learners...

... look for hidden possibilities ... judge things by gut reactions

... synthesize information from different sources ... are enthusiastic and adventurous

Field – Independent vs. Field Dependent:

• Field – Independent students: They can easily separate important details from complex or confusing background. They tend to rely on themselves and their own thought-system when solving problems. They are not so skilled interpersonal relationships.

• Field –dependent students: They find it more difficult to see the parts in a complex whole. They rely on others’ ideas when solving problems and are good at interpersonal relationships.

Left – Brain Dominated vs. Right Brain Dominated:

• Students who are left-brain dominated ... ... are intellectual

... process information in a linear way ... tend to be objective

... prefer established, certain information

... rely on language in thinking and remembering

• Those who are right-brain dominated... ... are intuitive

... process information in a holistic way ... tend to be subjective

... prefer elusive, uncertain information

... rely on drawing and manipulation to help them think and learn

There are some suggestions to suit teaching methods and activities to different learning styles:

The Four Modalities:

• Visual; use many visuals in the classroom. For example, wall displays, posters, realia, flash cards, graphic organizers etc.

• Auditory; use audio tapes and videos, story telling, songs, jazz chants, memorization and drills.

• Kinesthetic; use physical activities, competitions, board games, role plays etc. Intersperse activities which require students to sit quietly with activities that allows them to move around and be active.

• Tactile; use board and card games, demonstrations, projects, role plays etc. Use while listening and reading activities. For example; ask students to fill in a table while listening to a talk or to label a diagram while reading.

McCarthy’s Four Learning Styles

• Innovative learners; use cooperative learning activities and activities in which students must make value judgements. Ask students to discuss their opinions and beliefs.

• Analytic learners; teach the students the facts.

• Common sense learners; use problem-solving activities.

• Dynamic learners; ask students about their feelings. Use a variety of challenging activities.

Field – independent vs. Field – dependent:

• Field-independent; let the students work on some activities on their own.

• Field-dependent; let the students work on some activities in pairs and small groups.

Left – brain vs. Right – brain Dominated:

• Left-brain dominated; give verbal instructions and explanations. Set some closed tasks to which students can discover the “right” answer.

• Right-brain dominated; write instructions as well as giving them verbally. Demonstrate what you would like students to do. Give students clear guidelines, a structure, for tasks.

Set some open-ended tasks for which there is no “right” answer. Use realia and other things that students can manipulate while learning. Sometimes allow students to respond by drawing.

The teacher should take these different learning styles in consideration and in a classroom there may be students who learn differently so the teacher should make his or her lesson plans according to the different learners.

2.3.2. Child’s Learning Strategies

Now, we will have a look at the definition of strategies and what king of thing focuses on child’s attention. A child is not interested in language; he is just interested in playing. They use the language as a tool in order to play. If the language helps him in playing or his other interests, it gains importance. McGlothin explains The Child’s Learning Strategies as below:

• A child is not interested in English for it is on sake. His only interests are his toys, playmates and the things he can find that are not to be played with. The language is always of a secondary importance.

• A child is not disturbed with the language he does not understand.

• A child enjoys repetitive events of his life, and uses this enjoyment to help him learn the new language.

• A child uses his primary interest to help him learn. He learns the language in order to play, communicate, and provide his basic needs.

• A child directs his attention to the things that are easy to understand. He does not think about the world economy or foreign cultures. He thinks about the people around him and thinks around him.

• A child possesses a natural desire to call an object by its name and he uses that natural desire to help him learn the language.

• A child uses his natural desire to participate in the life around him to help him to learn new language. He wants to do what he sees others doing and when that includes language, he wants to speak it with too.

• A child adds words to his speaking vocabulary easily. If he already knows how to pronounce them.

• A child immediately uses the language and his success in communication builds confidence. He does not try to store up his knowledge for use at a later time.

• A child brings tremendous in genuity to the task of learning a new language. He has no fear of failure.

2.4. Language Development in Child

In this part, we will look at the child’s language development. There are many views on child’s cognitive development. Piaget (in Karlmiloff – Smith, 1979:3) describes the child’s cognitive development under four stages; Sensorymotor (0-2 Years), Preoperational (2-7 Years), Concrete Operational (7-11Years), and Formal Operational (11-15).

a) Sensorymotor: During this stage, the child learns about himself and his environment through motor and reflex actions. Thought derives from sensation and movement. The child learns that he is separate from his environment and that aspects of his environment – his parents or favourite toy- continue to exist even though they may be outside the reach of his senses. Teaching for a child in this stage should be geared to the sensorymotor system. You can modify behaviour by using the senses: a frown, a stern or a soothing noise. In this stage of development the child acts only with his basic needs.

b) Preoperational: Applying his new knowledge of language, the child begins to use symbols to represent objects. Early in this stage he also personifies objects. He is now better able to think about the things and events that are not immediately present. Oriented to the present, the child has difficulty conceptualizing time. His thinking is influenced by fantasy, the way he would like the things to be, and he assumes that others see the situations from his viewpoint. He takes in information and then changes it in his mind to fit his ideas. Teaching must take into account the child’s vivid fantasies and undeveloped sense of time. Using neutral words, body outlines and equipment a child can touch him an active role in learning.

c) Concrete Operational: During this stage, accommodation increases. The child develops an ability to think abstractly and to make rational judgements about concrete or observable phenomena, which in the past need to manipulate physically to understand. In teaching this child, giving him the opportunity to ask questions and explain things back to you allows him to mentally manipulate information.

d) Formal Operational: This stage brings cognition to its final form. This person no longer requires concrete objects to make rational judgements. At this point, he is capable of hypnotical and deductive reasoning. Teaching for the adolescent may be wide-ranging because he will be able to consider many possibilities from several perspectives.

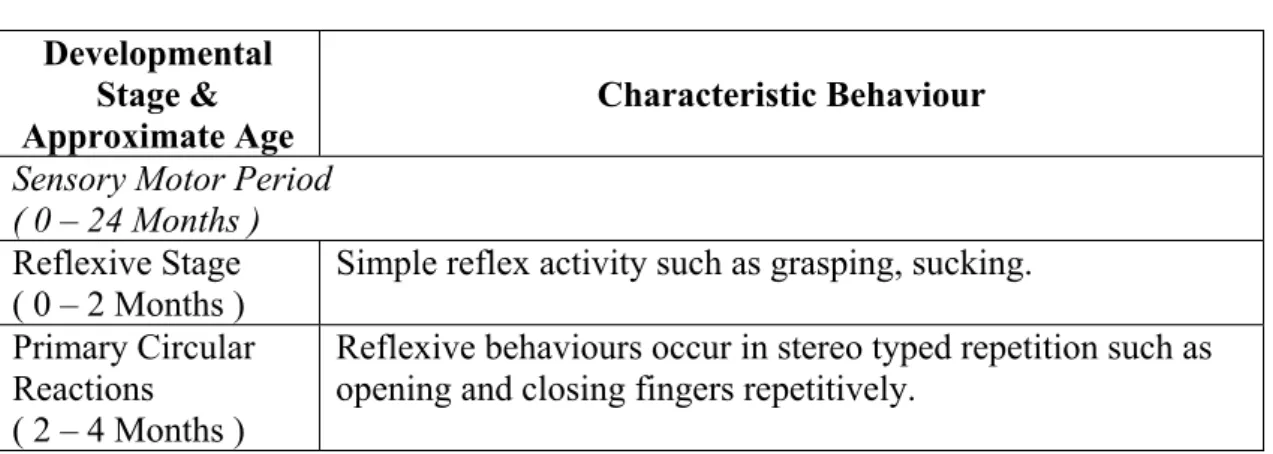

Table 2.1 Piaget’s Stages of Cognitive Development. Developmental

Stage & Approximate Age

Characteristic Behaviour Sensory Motor Period

( 0 – 24 Months ) Reflexive Stage ( 0 – 2 Months )

Simple reflex activity such as grasping, sucking. Primary Circular

Reactions ( 2 – 4 Months )

Reflexive behaviours occur in stereo typed repetition such as opening and closing fingers repetitively.

Secondary Circular Reactions

( 4 – 8 Months )

Repetition of change actions to reproduce interesting consequences such as kicking one’s feet to more a mobile suspended over the crib.

Coordination of Secondary Reactions

( 8 – 12 Months )

Responses become coordinated into more complex sequences. Actions take on an “intentional” character such as the infant reaches behind a screen to obtain a hidden object.

Tertiary Circular Reactions

( 12 – 18 Months )

Discovery of new ways to produce the same sequence or obtain the same goal such as the infant may pull a pillow toward him in an attempt to get a toy resting on it. Invention of New

Means Through Material

Combination ( 18 – 24 Months )

Evidence of internal representational system. Symbolizing the problem – solving sequence before actually responding. Deferred imitation.

The Preoperational Period ( 2 – 7 Years )

Preoperational Phase

( 2 – 4 Years )

Increased use of verbal representation but speech is egocentric. The beginnings of symbolic rather than simple motor play. Transductive reasoning. Can think about something without the object being present by use of language.

Intuitive Phase ( 4 – 7 Years )

Speech becomes more social, less egocentric. The child has an intuitive grasp of logical concepts in some areas. However, there is still a tendency to focus attention on one aspect of an object while ignoring the others. Easy to believe in magical increase, decrease, disappearance. Reality not firm.

Perceptions dominate judgement.

In moral – ethical realm, the child is not able to show principles underlying best behaviour. Rules of a game not develop, only uses simple do’s and don’ts imposed by authority.

Period of Concrete Operations ( 7 – 11 Years )

Evidence for organised, logical taught. There is the ability to perform multiple

classification tasks, order objects in a logical sequence, and comprehend the principle of conservation. Thinking becomes less transductive and less egocentric. The child is capable of concrete problem – solving.

Some reversibility now possible (quantities moved can be restored such as in arithmetic: 3+4=7 and 7-4=3, etc.)

Class logic – finding bases to sort unlike objects into logical groups where previously it was on superficial perceived attribute such as color. Categorical labels such as “number or animal” now available.

Period of Formal Operations ( 11 – 15 Years )

ability to generate abstract propositions, multiple hypotheses and their possible outcomes is evident. Thinking becomes less tied to concrete reality.

Formal – logic systems can be acquired. Can handle proportions, algebraic manipulation, other purely abstract processes. If a+b=x, then x=a-b. If ma/ca=IQ=1,00 then Ma=CA

Prepositional logic, as – if and if – then steps. Can use aids such as axioms to transcend human limits on comprehension.

CHAPTER III

LANGUAGE LEARNING AND TEACHING 3.0. First Language Acquisition

In this chapter, we will focus on language teaching and learning. It may be beneficial to begin with how the child acquires his first language, so this will give clues for second language learning and teaching.

George Yule (1985; 175) states that, the speed of acquisition and the fact that it generally occurs, without overtinstruction, for all children, regardless of great differences in a range of social and cultural factors, have led to the belief that there is some “innate” predisposition in the human infant to acquire language. We can think of this as the “language – faculty” of the human with which each newborn child is endowed. By itself, however, this faculty is not enough.

A child growing up in the first two or three tears requires interaction with other language-users in order to bring “language faculty” into operation with a particular language. He notes that a child who does not hear, or is not allowed using; the language will learn no language. He also stresses the importance of “cultural transmission” meaning that the language a child learns is not genetically inherited, but is acquired in a particular language – using environment.

The child must be physically capable of sending and receiving sound signals in a language. All infants make “cooking” and “babbling” noises during the first few months, but congenitally deaf infants stop after six months. So, in order to speak a language, a child must be able to hear that language being used. By itself, however, hearing language sounds is not enough. One reported case showed that with deaf parents who gave their normal – hearing son ample exposure to TV and radio programs, the child did not acquire an ability to speak or understand English. What he did learn very effectively, by the age of three, was the use of American Sign Language, the language he used to interact with his parents.

All normal children, regardless of culture, develop language at roughly the same time, along much the same Schedule. The physical activities like sitting and walking which are determined by the development of motor skills have the same basis with language development. Namely, both of the activities are depend on the child’s biological capacity. As all we know the baby should have enough maturity to stand and to walk. Baby cannot walk before creeping. First the baby should learn creeping then standing and then walking. Language acquisition schedule has the same basis. This biological schedule is tied the maturation of brain. Every child has biological capacity and this capacity requires sufficient input.

There are a number of controversial issues. Children acquire the language whether with innate talent or from his environment. Noam Chomsky (1983) has proposed that language development should be described as “language growth” because the “language organ” simply grows like any other body organ. This underestimates the importance the others’ views the importance of environment and experiences in the child’s development of language.

Another controversial issue is how we should view the linguistic production of young children. The linguist’s view tends to concentrate on describing the child’s speech in terms of the known units of phonology and syntax, for example. However, the child’s view of what is being heard and uttered at different stages may be based on quite different units. For example, a child’s utterance of [dùkəǽt] may be single unit for the child, yet may be treated as having three units, look at that by an investigator interested in the child’s acquisition of different types of verbs.

To sum up, all the children acquire the language at last, if he has no biological and pyshycological problems. But, they need sufficant input. And they should interact with the language. The parents should contact with them whether they have response or not. The child should be given opportunity to use the language whether you understand the language or not.

3.1. Second Language Acquisition / Learning

Many children whose parents speak different languages can acquire a second language in circumstances similar to those of first language acquisition. Learners can be proficient in a second language as they are in their first language.

From the 1960s onwards, great strides were made in first language acquisition research. Taking its cue from these, and starting in earnest in the 1970s, Second Language Acquisition research concerned itself with both explaining and describing the process of acquiring a second language. It has looked at the route, the rate, and the end state of second language acquisition, and the ways in which it is affected by external factors such as instruction, interaction and motivation. Praticular areas of interest have included the degree of transfer from the first language, the degree of systematicity in learners’ language, variation between learners or within one learner, and – most of all perhaps – why the process of acquiring a second language as opposed to acquiring a first language, is so often regarded as “incomplete”. Lastly, the findings of Second Language Acquisition research have frequently been drawn upon to suggest ways of improving language teaching and learning.

A great deal has been discovered by second language research and many explanations advanced. But, valid reservations have been expressed. One point of criticism is the term “the learner” of a Universalist model of the kind developed for the first language acquisition in linguistics. The process of Second Language Acquisition is considered to be more or less the same for all learners, relatively, unaffected either by exernal variables or by differences between languages. However, appropriate this model may be for first language acquisition. Where, there are elements common to the experience of every child, for Second Language Acquisition, it is much less convincing. In Second Language Learning, there are differences between learners and learning contexts, with consequent differences of outcome. Another point of criticism betrayed by the term Second Language Acquisition is the frequent implication that monolingualism is the normal starting point for language learners. The learners of Second Language Acquisition are those who are adding one language to an existing

repertoire of more than one. The term “Additional Language Acquisition” can be more appropriate.

There is an arguement that given the extent of individual and sociological variables, the difficulties of replicating the same learning situation and the subjective nature of measuring success, conclusions cannot be as factual and reliable as we are led to believe. It is said that, even if claims and findings are reliable and generalizable, there remains a need to adjust to differing educational and cultural traditions. Mediation is needed between the knowledge of “the experts” and the wishes and wants of individual students. The classic example of this is the resistance by many teachers and learners to Second Language Acquisition claims in the 1980s that language acquisition can take place without explicit learning of rules, translation, and grading of structures.

In recent years, such criticisms have been voiced with increasing frequecy and persuasiveness. There are also richer and more contexts – sensitive approaches now gathering momentum. They recognise the diverse and imprecise nature of Second Language Acquisition allowing the findings of research to be made relevant to widely varying types of educational situation.

To explain the Second Language Acquisition Theory, we should describe some very important hypotheses. The first three are, the acquisition – learning distinction, the natural order hypothesis, and the Monitor hypothesis. We have to give information about the other two, to give a good idea of hypotheses and the sort of evidence that exist to support them. The fourth hypothesis, the Input Hypothesis, may be the single most important concept in Second Language Acquisition Theory today. It is important because it attempts to answer the crucial theoritical question of how we acquire language. It is also important because, it may hold the answer many of our everyday problems in Second Language Instruction at all levels. The other hypothesis, Affective Filter, explains how affective variables relate to the process of Second Language Acquisition.

3.1.1. Acquisition – Learning Distinction

The acquisition – learning distinction is perhaps the most fundemental of all hypotheses. This hypothesis states that adults have two distinct and independent ways of developing competence in a second language.

The first way is language acquisition, it is a subconscious process: language acquirers are not usually aware of the fact that they are acquiring the language, but are only aware of the fact that they are using the language for communication. The result of language acquisition is also subconscious. We are generally not consciously aware of the rules of the languages we have acquired. Instead, we feel the correctness. We say, we do not know the rule but we feel it is right. We can describe the acquisition as implicit learning, informal learning, and natural learning. Namely, we can call the acquisition as picking – up a language.

The second way is language learning. We will use the term “learning” to refer to conscious knowledge of a second language, knowing the rules, being aware of them, and being able to talk about them. We can describe the learning as explicit learning, formal knowledge of the language. We can call the learning as knowing about a language. As the language users are aware of the fact they try to obey the rules.

Some second language theorists have assumed that children acquire but adults can only learn. The acquisition – learning hypothesis claims, However, that adults also acquire the ability to “pick – up” languages does not disappear at puberty. This does not mean that, adults will always be able to achieve native – like levels in a second language.

Error correction has little or no affect on subconscious acquisition but it can be useful for conscious learning. For example, if a student of English as a second language “I gets up at 8:00 every morning” and the teacher corrects him/her by repeating the utterance correctly, the learner is supposed to realize that the “s” ending gets with the third person and not the first person. This seems reasonable but it is not clear that the

Error correction has an impact on learning in actual practice. Namely, it is not clear that which is more affective to correct the errors while we are learning or communicating the others.

Brown and his colleagues have shown that parents actually correct only a small portion of the child’s language (occasional pronunciation problems, certain verbs and dirty words). They conclude from their research that parents attend far more to the truth value of what the child is saying rather than to the form. Namely, parents only notice the message they say. For example, if a child says “the wall is blue”, parents only look if the wall is really blue or not. They do not care whether the sentence is gramatically correct or not. Parents are only interested in the meaning of the sentence. But in a language course, teachers are only interested in correcting the gramatical errors. They do not give importance to the meaning.

The acquisition – learning distinction may not be unique to second language acquisition. We certainly “learn” small parts of our first language in school.

3.1.2. Natural Order Hypothesis

One of the most exciting discoveries in language acquisition research in recent years has been definding that the acquisition of gramatical structures proceeds in a predictable order. Acquirers tend to acquire certain gramatical structures early, and others later. The agreement among individual acquirers is not always 100%, but there are clear, statistically significant, similarities.

English is perhaps the most studied language as far as the natural order hypothesis is concerned, and of all structures of English, morphology is the most studied. Brown (1973) reported that children acquiring English as a first language tended to acquire certain gramatical morphemes, or functions words, earlier than others. For example, the progressive marker “ing” and the plural marker “s” were among the first morphemes acquired, while the third person singular marker “s” and the possesive “s” were acquired much later. De Villiers (1973) confirmed Brown’s longitudinal

results cross – sectionalily, showing that items that Brown found to be acquired earliest in time were also the ones that children tended to get right more often. In other words, for those morphemes studied, the difficulty order was similar to the acquisition order.

After Brown’s results were published, Dulay and Burt (1974, 1975) reported that children acquiring English as a second language also show a “natural order” for gramatical morphemes, regardless of their first language. The child’s second language order of acquisition was different from first language order, but different groups of second language acquirers showed striking similarities.

Dulay and Burt used a subset of the 14 morphemes, Brown originally investigated. Fathman (1975) confirmed the reality of the natural order in second language acquisition with her test of oral production, the SLOPE test, which probed 20 different structures. Following Dulay and Burt’s work Bailey, Madden, and Krashen (1974) reported a natural order for adult subjects, and order quite similar to that seen in child second language acquisition. This natural order appears only under certain conditions. Some of the studies confirming the natural order in adults for gramatical morphemes include Andersen (1976), who used composition, Krashen, Houck, Giunchi, Bode, Birnbaun, and Strei (1977), using free speech, and Christison (1979), also using free speech. Adult research using the SLOPE test also confirms the natural order and widens the database. Krashen, Sferlazza, Feldman and Fathman (1976) found an order similar to Fathman’s (1975) child second language order, and Kayfetz – Fuller (1978) also reported a natural order using the SLOPE test.

As we said before, the order of acquisition for second language is not the same as the order of acquisition for the first language, but there are some similarities.

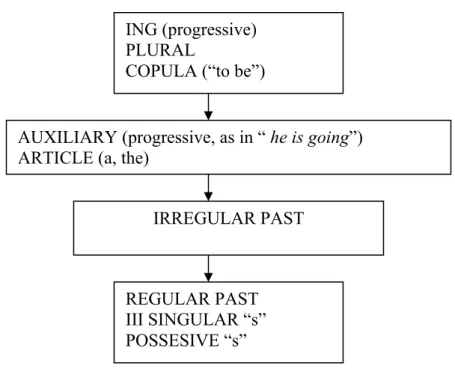

Figure 3.1 “Avarage” order of acquisition of gramatical morphemes for English as a second language (children and adults)

Figure 3.1., from Krashen (1977), presents an avarage order for second language, and shows how the first language order differs. This avarage order is the result of a comparison of many empirical studies of gramatical morpheme acquisition.

3.1.3. The Monitor Hypothesis

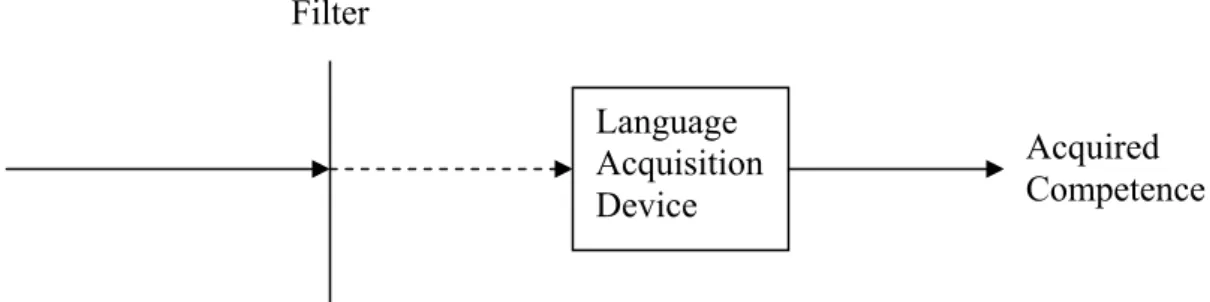

The Monitor Hypothesis posits that acquisition and learning are used in very specific ways. Acquisition “initiates” our utterances in a second language and is responsible for our fluency. Learning has only one function, and that is as a Monitor; or editor. Learning comes into play only to make changes in the form of our utterance, after it has been produced by the acquired system. This can happen before we speak or write or after. Figure 3.2. models this process.

ING (progressive) PLURAL

COPULA (“to be”)

AUXILIARY (progressive, as in “ he is going”) ARTICLE (a, the)

IRREGULAR PAST

REGULAR PAST III SINGULAR “s” POSSESIVE “s”

Figure 3.2. Acquisition and learning in second language production.

The Monitor hypothesis implies that, formal rules, or conscious learning, play only a limited role in a second language performance. These limitations suggest that second language performers can use conscious rules only when three conditions are met. These conditions are necessary and not sufficient, that is, a performer may not fully utilize his conscious grammar even when all three conditions are met. Now we will mention these conditions shortly.

i. Time: In order to think about and use conscious rules affectively, a second language performer needs to have sufficient time. When people have normal conversation, they do not have enough time to think about and use the rules. The over – use of rules in conversation can lead to trouble like hesitant style of talking and inattention to what the conversation partner is saying.

ii. Focus on form: The performer must also be focussed on form, or thinking about correctness (Dulay and Burt, 1978). Even when we have time, we may be so involved in what we are saying that we do not attend to how we are saying.

iii. Know the rule: This may be very discouraging requirement. Linguistics has taught us that the structure of language is extremely complex. We can be sure that our students are exposed only to a small part of total grammar of the language. And we know that, even the best student do not learn every rule they are exposed to.

Output Learned

Competence ( the Monitor )

Acquired Competence

The evidence for the production schema shown in Figure 3.1 comes originally from the natural order studies. These studies are consistent with this generalization: we see the natural order for gramatical morphemes that is child’s difficulty order when we test subjects in situations that appear to be “Monitor – free”; where they are focussed on communication and not the form (This situation happens at the time when she/he cannot find opportunity to use his or her mind). When we give our adult subjects test that meet the three conditions “grammar test” we see “unnatural” orders, orders unlike the child’s second language order of acqusition or difficulty order. The interpretation of this result is that the natural order reflects the operation of the acquired system alone, without the intrusion of the conscious grammar, since adult second language acqusition is posited to be similar to the child’s second language acquisition. When we put people in situations where three conditions met, when they have time, are focused on form, and know the rule, the error pattern changes, reflecting the contribution of the conscious grammar.

We can say that unnatural orders are the result of a rise in rank of certain morphemes, the late – acquired, more learnable items.

Use of the conscious Monitor has the effect of allowing performers to supply items that are not yet acquired. However, only certain items can be supplied by most Monitor users; Monitor does a better job with some parts of grammar than with others. Specifically, it seems to do better with rules that can be characterized as “simple” in two different ways. First, the rules that do not require elaborate movements or permutations; rules that are syntactically simple. Easy rules in this sense include bound morphology, such as the third person singular in English. Difficult rules in this sense include the English wh- question rule, which requires moving the questioned word to the front of the sentences. Rules can be difficult or easy due to their semantic properties.

To summarize, Monitor use results in the rise in rank of items that are “late-acquired. Only certain items can rise in rank, however. When Monitor use is heavy, this rise in rank is enough to disturb the natural order. It is possible to see small changes in certain late – acquired morphemes that are not enough to disturb the natural order; this can be termed as Light Monitor.

It is not easy to encourage noticable Monitor use. Experimentation has shown that anything less than a real grammar test will not bring out the conscious grammar in any force. Keyfetz (1978) found natural orders for both oral and written version of the SLOPE test, showing that simply using the written modality is not enough to cause an unnatural order. Houck, Robertson and Krashen (1978) had adult subjects correct their own written Output, and still found a natural order for the corrected version. Krashen, Butler, Birnbaum, and Robertson (1978) found that even when ESL students write composition with plenty of time and under instructions to be very careful the effect of Monitor use was suprisingly light. The best hypothesis now is that for most people it takes a real discrete – point grammar – type test to meet all three conditions for Monitor use and encourage significant use of the conscious grammar. In other words the students use Monitor when they have a real discrete point grammar type test.

There are three basic types of performer for individual variation in Monitor use.

1. Monitor Over – Users:

These are the people who attempt to monitor all the time, performers who are constantly checking their output with their conscious knowledge of the second language. So performers may speak hesitantly and are so concerned with correctness that they can not speak fluently.

There may be two reasons for over-use of the grammar. First may derives from the performers’ history; they may not be given sufficient opportunity to acquire the language. The other reason can be related with the performer’s personality. They may not trust acquired competence and only feel secure when they refer to their Monitor.

2. Monitor Under – Users:

These are performers who have not learned, or if they have learned, prefer not to use their conscious knowledge, even when the conditions allow it. They are not

influenced by error correction. They correct themselves by feeling the correctness or by relaying the acquired system.

Stafford and Covitt (1978) note that, some under users pay “lip – service” to the value of conscious grammar. They say that grammar is the key to every language but they do not put them to the practice.

3. The Optimal Monitor User:

The pedagogical goal is to produce optimal users, performers who use the Monitor when it is appropriate and when it does not interfere with communication. Many optimal users will not use grammar in ordinary conversation, where it might interfere. Some very skilled performers, such as some Professional linguists and language teachers might be able to get away with using considerable amounts of conscious knowledge in conversation. We can consider these people as “super Monitor users” however these performers when there is time, use their conscious grammar in writing and planned speech.

Namely, optimal Monitor users can use their learned competence as a supplement to their acquired competence. Some optimal users who have not completely acquired their second language, who make small and occasional errors in speech can use their conscious grammar so successfully that they can often produce the illusion of being native in their writing.

Input Hypothesis

Input hypothesis will take more time than the others because of two reasons. First, much of this material is relatively new. Second reason is, its importance, both theoritical and pratical. The input hypothesis tries to answer perhaps the most important question. This question is, how we acquire language. If the Monitor hypothesis is correct, acquisition must be the body in the language teaching. So, we must aim the

acquisition but how the acquisition is performed is another important question. There are evidences from research in the first and second language acquisition.

Statement of Hypothesis

If we suppose the correctness of natural order hypothesis, how do we move from one stage to another. The input hypothesis makes the following claim: a necessary (but not sufficient) condition to move from stage i to stage i+1 is that the acquirer understand input that contains i+1, where “understand” means that, the acquirer is focessed on the meaning and not the form. In other words, i represents our current level, i+1 represents the next level.

There is a problem that how we can understand the language that contains structures that we have not yet acquired. So, we use more than our linguistic competence to help us to understand. We also use context, our knowledge of world, our extra – linguistic information to help us understand language directed at us.

As Hatch (1978) has pointed out that we first learn structures, than practice learning them in communication, and this is how fluency develops. But, the input hypothesis says the opposite. It says, we acquire by “going for meaning” first, and as a result, we acquire structure. Although you do not know the words, sentences, you can learn them from the context. For example, you are teaching the future perfect tense, you can give the students a context which contains future perfect tense sentences like fortuneteller, and they can understand the sentences easily.

Thus, we can state first two parts of input hypothesis as follows:

• The input hypothesis relates to acquisition, not learning.

• We can acquire the language that contains structures a bid beyond our current level of competence (i+1). This is done by the help of context or extra linguistic information.

The third part of input hypothesis says that, input must contain i+1 to be useful for language acquisition, but it need not contain only i+1. It says that, if the acquirer understands the input, and there is enough of it, i+1 will automatically be provided. The best input should not even attempt to deliberately aim at i+1. Usually, both teachers and students feel that the aim of the lesson is to teach or to practice the structure. Once, this structure is mastered the syllabus proceeds to the next one. Input hypothesis implies that such a deliberate attempt is not necessary. Thus, third part of the hypothesis is :

• When communication is successful, when the input is understood and there is enough of it, i+1 will be provided automatically.

The final part of the input hypothesis states that speeking fluency cannot be taught directly. It emerges overtime, on its own. The best way to teach speeking is to provide comprehensible input. Early speech will come when the acquirers feel ready. The fourth and the last part of the hypothesis is :

• Production ability emerges. It is not taught directly.

Evidence Supporting The Hypothesis

• First Language Acquisition in Children: The input hypothesis is very consistent with “caretaker speech”, the changes that parents and others make when talking to young children. But, they do not attempt to teach the language deliberately. As Clark and Clark (1977) point out that caretaker speech is modified in order to aid comprehension. Caretakers talk is simpler to make the parents and the others to be understood by the child. The second characteristic of caretaker speech is “roughly – tuned” to the child’s current level of linguistic competence, not “finely – tuned”. In other words, caretaker speech is not precisely adjusted to the level of each child, but tends to get more complex as a child progresses. Caretakers are not taking aim exactly at i+1. the input they provide for children includes i+1, but also includes many structures that have already been acquired, plus some that have not (i+2, i+3) and that the child may

not be ready for yet. The third characteristic of caretaker speech that concerns us is known “here and now” principle. Caretakers talk mostly about what the child understand what is in the immediate environment. They deal with what is in the room and happening now.

While there is no direct evidence showing that caretaker speech is more affective than unmodified input, the input hypothesis predicts that caretaker speech will be very useful for the child because it aims to be comprehensible and “here and now” feature provides extra – linguistic context that helps the child understand the utterances containing i+1. McNamara (1972) pointed that the child understands first, and this helps him acquire language.

Roughly – tuned caretaker speech includes i+1 but does not focus on i+1 exclusively. If you understand there is automatically i+1. Roughly – tuned input has the following advantages.

i) Roughly – tuned input include i+1. The child’s level is not important to get i+1 input. For finely – tuned input, everybody is not accepted at the same level and the same things are taught to the child. However it is not useful. It ensures that i+1 is covered with no guesswork as to just what i+1 is for each child. On the other hand, deliberate aim i+1 might miss.

ii) Roughly tuned input provides i+1 for more than one child at a time, as long as they understand what is said. Finely – tuned input will only benefit the child whose i+1 is exactly the same as what is emphasized in the input.

iii) Roughly – tuned input provides built – in preview. As you use everything in everytime, the child has an opportunity to review. With natural roughly – tuned input i+1 will occur and reoccur.

If these are correct, caretakers’ speech is understood, i+1 input is always provided. So, caretakers need not worry about consciously programming the structure.