An Integrative Model Proposal About Underlying Mechanisms

Involved in Disturbing Dream Themes: Defense Styles,

Dysfunctional Attitudes, Interpersonal Styles, and Dream Th....

Article in Dreaming · July 2018

DOI: 10.1037/drm0000077 CITATIONS 0 READS 41 2 authors: Esra Güven Baskent University 6PUBLICATIONS 8CITATIONS SEE PROFILE

Gülçim Bilim Baykan Ufuk Üniversitesi

1PUBLICATION 0CITATIONS SEE PROFILE

All content following this page was uploaded by Esra Güven on 08 October 2019. The user has requested enhancement of the downloaded file.

Mechanisms Involved in Disturbing Dream Themes:

Defense Styles, Dysfunctional Attitudes, Interpersonal

Styles, and Dream Themes

Esra Güven

Çukurova University

Gülçim Bilim

Ufuk University

The aim of the study was to investigate the psychological processes pointed out by dream contents and themes. For this purpose, a model that indicates mediation roles of interpersonal relationship style and dysfunctional attitudes, on the relation-ship between immature and neurotic defense mechanisms and disturbing dream themes in addition to direct relationship between these defense mechanisms and disturbing dream themes, was examined. The sample included 610 adults within the age range of 18 to 65. The results of the structural equation modeling analysis demonstrated that the proposed model fitted the values for a good model and explained 22% of the variance. Considering that the research focused on dream processes is limited in the literature, this research plays a crucial role in providing important information on the issue.

Keywords: dream themes, defense mechanisms, dysfunctional attitudes, interpersonal relationship style

Dreams have long been seen as mysterious phenomena worth solving and have attracted the attention of many fields of study including psychology for centuries. Scientific study of dreams acquired a psychological dimension first throughFreud’s

(1899/1996, p. 114) “royal road to unconscious- via regia,” and today it has become

a functional material used in psychotherapies. Despite the increasing number of scientific studies on dreams recently, explanations still seem controversial; in other words, dreams still keep their mystery.

Although dream themes are identified as characteristic content that occurs in dreams, dream content represents basic emotion, subject, or situation revealed by

This article was published Online First July 19, 2018.

Esra Güven, Faculty of Science and Letters, Department of Psychology, Çukurova University; Gülçim Bilim, Faculty of Art and Science, Department of Psychology, Ufuk University.

Correspondence concerning this article should be addressed to Esra Güven, who is now at Faculty of Science and Letters, Department of Psychology, Bas¸kent University, Bag˘lıca Kampüsü, Eskis¸ehir yolu 18.km, 06790 Etimesgut/Ankara, Turkey. E-mail:esra.guvenn@gmail.com

This document is copyrighted by the American Psychological Association or one of its allied publishers. This article is intended solely for the personal use of the individual user and is not to be disseminated broadly. 261

Dreaming © 2018 American Psychological Association

dream images (Beck & Ward, 1961). After or during various dream theme experiences, individuals may feel some negative or positive emotions that induce him/her to be disturbed, uncomfortable, pleased, or neutral (Greenberg, Katz, Schwartz, &

Pearl-man, 1992; Moffit, Kramer, & Hoffman, 1993). For example, seeing something that

makes the dreamer fearful or seeing somebody following the dreamer in dreams may induce negative emotions and make the dreamer disturbed. In contrast, seeing somebody who is missed or a loved one, or doing something that the dreamer likes to

do, may induce positive emotions and make the dreamer pleased (Genç, Koçak,

Çelikel & Bas¸ol, 2013;Nielsen et al., 2003).

Research has indicated that content that reveals dream themes is affected by an individual’s internal and external processes (Caperton, 2012;Hill et al., 2013;

Hill & Knox, 2010;Rosner, 2004;Tien, Chen, & Lin, 2009). An individual’s mood,

thoughts, and behaviors, interpersonal relationships, or residuals from daily routine may be examples of these processes. In this study, within the independent variables, defense mechanisms are designed for representing an individual’s internal pro-cesses, whereas dysfunctional attitudes and interpersonal relationship styles repre-sent external processes reflected in awakened life.

Defense mechanisms are one of the psychological concepts most focused on as

a correlated variable with dreams and dream themes (Bryant, Wyzenbeek, &

Weinstein, 2011;Cartwright, 2010;Euler, Henkel, Bock, & Benecke, 2016;Freud,

1899/1996; Geçtan, 2005;Hartmann, 1998; Kröner-Borowik et al., 2013;

Lichten-berg, Lachmann, & Fosshage, 1992;Marcus, 2008;Vogel, 1960;Yu, 2011a,2011b).

Defense mechanisms were first defined byFreud (1966)as a psychological process that provides self-control over internal tensions like impulsive behaviors, emotions, or instinctual desires and makes ego move away unwanted and worrying behaviors. These psychological processes are assessed in three basic categories: mature, immature, and neurotic defenses (Vaillant, 1992;Vaillant, Bond, & Vaillant, 1986). Mechanisms such as projection, denial, repression, somatization, passive aggres-sion, regresaggres-sion, dissociation, and displacement have been approved as negative defense mechanisms including immature and neurotic categories (Andrews, Singh,

& Bond, 1993;Vaillant et al., 1986). Research about associations between defense

mechanisms and dream themes indicate two different links. The first link is about dreams and its contents being a defense mechanism all by itself. This link is based on dreams’ function that protects an individual’s ego integrity and psychological well-being in waking life by discharging the energy created by desires and drives

inappropriate to express in waking life through dreams (Marcus, 2008; Vogel,

1960). The other link indicates that dream process and content take place via a filter

composed by defense mechanisms (Freud, 1899/1996). According to this link,

repressing the thoughts makes the repressed content to occur in dreams (Bryant et

al., 2011;Kröner-Borowik et al., 2013). In addition to these fundamental

associa-tions between defense mechanisms and dream themes, some empirical studies have focused on links such as those between maturity of defenses and dreams’ complexity and liveliness (Euler et al., 2016) or especially, suppression and dream themes (Bell & Cook, 1998;Kröner-Borowik et al., 2013;Yu, 2011a).

Another psychological process thought to be reflected in dreams is individual’s dysfunctional attitudes. Dysfunctional attitudes are defined as negative judgments and beliefs that are formed by communicating to others, which decrease an individual’s life quality and determine an individual’s perspective about

This document is copyrighted by the American Psychological Association or one of its allied publishers. This article is intended solely for the personal use of the individual user and is not to be disseminated broadly.

himself/herself, others, and life (S¸ahin & S¸ahin, 1992; Weissman & Beck, 1978). According toBeck (1971/2002), dreams, which offer varying functions for individu-als, do not always contribute to an individual’s insight development, but they make an individual’s problems clearer and give clues about his or her dysfunctional

attitudes. Weissman and Beck (1978)indicated that dream themes are not about

unconscious processes, but they are about cognitive processes such as dysfunctional attitudes that can be measured. For instance, in depression, the basic elements that affect dream themes are an individual’s negative attitudes such as loneliness, imperfection, or worthlessness about himself/herself and others.

Indeed, defense mechanisms and dysfunctional attitudes, which are two divergent concepts of two divergent approaches (psychoanalytic and cognitive theories) trying to explain psychopathology, seem to correlate closely.Beck (1997), in an article where he discussed cognitive therapy’s past and future, stated that individuals behave according to their defense mechanisms, but the factors that determine these mechanisms are their cognitive processes that indicate the way individuals judge the situations. Besides other research that assessed associations between defense mechanisms and dysfunctional attitudes over various psychopa-thologies, there is also some research about associations between defense mecha-nisms and cognitive biases that are thought to contribute to dysfunctional attitudes

(Coleman, Cole, & Wuest, 2010; Cras¸ovan, 2014; Hovanesian, Isakov, &

Cervel-lione, 2009; Wenzlaff & Bates, 1998). Kwon (1999), for example, stated that

cognitive biases such as generalization, personalization, hopelessness, and catastro-phizing that contribute to dysfunctional attitudes are associated with immature defense mechanisms. Also, other research has indicated that psychopathologies such as depression are thought to be based on cognitive symptoms, and are also associated with defense mechanisms (Kwon, 1999;Spinhoven & Kooiman, 1997). These findings remark the associations between defense mechanisms and dysfunc-tional attitudes.

Social interaction and interpersonal relationships, or interpersonal relationship characteristics, are other factors thought to have effect on dream themes and content (Hall & Nordby, 1972; Schweickert, 2007; Van de Castle, 1991). It is obvious that significant relationships and their objects are seen in dreams fre-quently. Even though awake interpersonal relationships’ reflections are observed in dreams as dream figures, associations between dream themes/contents and inter-personal relationship styles such as egocentric or depreciatory have not been clear yet. Interpersonal relationship style has been defined as forms of an individual’s experienced and internalized emotion, thoughts, and behaviors during relationships with others (Plutchik, 1997). Interpersonal relationships and conflicts that influence a great part of our lives as social beings are often reflected in our dreams (Van de

Castle, 1991). Even though, during the literature review, no study was found

emphasizing the direct links between defense mechanisms and interpersonal styles, there are findings pointing out that immature defense mechanisms have a disruptive effect on interpersonal relationships (Cramer, Blatt, & Ford, 1988;Perry & Cooper,

1992; Vaillant, 1992). Similarly, there is some research stating the link between

defense mechanisms and interpersonal relationship satisfaction (Ungerer, Waters,

Barnett, & Dolby, 1997).Mulder, Joyce, Sellman, Sullivan, and Cloninger (1996)

also indicated that immature defense mechanisms are associated with dysfunctional personality patterns such as neurosis.

This document is copyrighted by the American Psychological Association or one of its allied publishers. This article is intended solely for the personal use of the individual user and is not to be disseminated broadly.

Although direct links in the context of outlined theoretic framework couldn’t be reached, individuals’ interpersonal styles and dysfunctional attitudes may have significant effects on associations between dream themes and defense mechanisms. In this context, the aim is to analyze a model that includes indirect correlations between defense mechanisms and disturbing dream themes mediated by dysfunctional attitudes and interpersonal relationship styles besides its direct correlations (Figure 1). Disturbing dream themes, which are evaluated as a dependent variable in this study, refer to specific dream contents dominated by negative emotions such as fear, anxiety, or frustration.

Method Participants

After data cleaning, a total of 610 adults (356 [58.4%] women and 254 [41.6%] men) aged 18 – 65 years old (Mage⫽ 34.33, SD ⫽ .13.57) participated voluntarily. In

all, 34.5% of the participants’ highest level of education was high school or lower, 54.6% of the participants were college students or graduates, and 38.5% of the participants last graduated from master’s or doctorate programs. In addition to these descriptive statistics, 38.5% of the participants were married, 19.2% of the participants were in a relationship, and 42.3% of the participants were single.

Measures

Dream Themes Scale. The 29-item Dream Themes Scale (DTS;Genç et al.,

2013; Cronbach’s␣ ⫽ .94) was used as a measure of disturbing dream themes. The individuals rated the theme expressions on the scale ranging from 0 (never) to 4 (always) according to their frequency of experience. Rising scores indicate increas-ing frequency of viewincreas-ing of the related theme.

In the development process of the scale, first, some expressions were collected from 200 healthy adults about their explicit content they could recall from their

Interpersonal Relationships Style Dream Themes Defense Styles Dysfunctional Attitudes Depreciatory Egocentric Immature Neurotic Negative Anxiety Fear Frustration

Figure 1. Dream themes model.

This document is copyrighted by the American Psychological Association or one of its allied publishers. This article is intended solely for the personal use of the individual user and is not to be disseminated broadly.

dreams. Thanks to these data, a dream theme/content pool was created, and the experts created a comprehensive initial scale by selecting expressions that they think fit in the light of the literature, from the pool of dream themes. Second, data were collected with the initial scale, and factor structure, validity, and reliability of the scale were examined. As a result of the related processes, 29 items representing the explicit content that individuals remembered in their dreams were created. It was found that these 29 items were collected under five factors on the basis of negative emotions (fear, anxiety, negativity, and frustration) and experiential remains without negative feeling loads. The four subscale items used in the context of this study are as follows:

Negative Themes

● I experience nice events in my dreams (reverse coded items [R]). ● In my dreams, I see that I succeed at something I tried to do (R). ● I am the one who has the leading role of the events in my dreams (R). ● In my dreams, I see that my future plans come true (R).

● In my dreams, I feel desperate in the face of events that happen to me. ● I see myself happy/joyful in my dreams (R).

● In my dreams, I am being humiliated by other people. ● I feel insufficient in my dreams.

Anxiety Themes

● In my dreams, I am looking for something I have lost/forgotten. ● In my dreams, I feel uneasy about what I am experiencing. ● In my dreams, I see myself having serious health problems. ● Worrying feelings dominate my dreams.

● In my dreams, I am afraid of something I do not know the reason for. ● In my dreams, I am with people I love/am close to (R).

● In my dreams, I sometimes see things that frighten me in my daily life. Fear Themes

● In my dreams, I see that others do evil to me. ● I see that I am tested in my dreams.

● I exhibit aggressive behavior in the events of my dreams. ● Some people follow me in my dreams.

This document is copyrighted by the American Psychological Association or one of its allied publishers. This article is intended solely for the personal use of the individual user and is not to be disseminated broadly.

● I am threatened in my dreams. Frustration Themes

● In my dreams, I am inhibited while trying to do something.

● My thoughts and feelings that I cannot share with people come into my dreams.

● In my dreams, I see myself defeated.

● In my dreams, I see doing something that I am embarrassed to do in my awake life.

The scale is composed of five subscales (Negative, Anxiety, Fear, Frustration, and Effect of Experiences), and the Cronbach’s␣s of the subscales ranged from .77 to .94. In line with the aims of this research, four of the subscales representing disturbing dream themes (negative, anxiety, fear, and frustration dream themes) were used.

Defense Styles Questionnaire. Negative subscales of the 40-item Defense

Styles Questionnaire (DSQ-40) developed byAndrews et al. (1993)and adopted by

Yılmaz, Gençöz, and Ak (2007)were used as a measure of negative defense styles. The

scale is composed of three subscales (Mature, Immature, and Neurotic Defense Styles)

whose Cronbach’s ␣s ranged from .61 to .83. The DSQ-40 includes items such as

“There is someone I know who can do anything and who is absolutely fair and just,” “People tend to mistreat me,” and “I’m able to laugh at myself pretty easily.” Participants rated the expressions on the scale ranging from 1 (it is not appropriate for me at all) to 9 (it is very appropriate for me) according to conformity to themselves. Rising scores indicate increasing intensity of the use of defense styles.

Interpersonal Relationships Styles Inventory. The 31-item Interpersonal

Relationships Styles Inventory (IRSI; S¸ahin, Durak, & Yasak, 1994; Cronbach’s ␣ ⫽ .79) was used as a measure of interpersonal relationships styles. The scale is composed of two basic subscales (Positive and Frustrative Interpersonal Styles), with each being sheared into subdimensions. In line with the aims of this research, only Frustrative Interpersonal Styles subscales’ subdimensions (egocentric and depreciatory styles) were used in this study. The IRSI includes items such as “I like lashing out somebody” and “I like bragging and talking just about myself.”

Participants rated the expressions on the scale ranging from 0 (never) to 3 (always) according to their frequency of experience. Rising scores indicate increas-ing positiveness on interpersonal relationships styles.

Dysfunctional Attitudes Scale. The 17-item Dysfunctional Attitudes Scale

(DAS)—first developed byWeissman and Beck (1978), adopted byS¸ahin and S¸ahin

(1989), and shortened byÇekmece (2010)—was used as a measure of dysfunctional

attitudes. The scale has a single factorial structure (Cronbach’s ␣ ⫽ .81). The DAS includes items such as “I have to be successful all the time for people to respect me” and “If someone doesn’t agree with me, it means that s/he doesn’t like me.”

The individuals rated the expressions on the scale ranging from 1 (0%) to 7 (100%) according to rate of conformity to themselves. Rising scores indicate increasing positiveness on interpersonal relationships styles.

This document is copyrighted by the American Psychological Association or one of its allied publishers. This article is intended solely for the personal use of the individual user and is not to be disseminated broadly.

Procedure

Participants accessed the measures via an online survey system. The proposed integrative model was analyzed with the Lisrel 8.51 package program (Jöreskog & Sörbom, 2001). Participants’ willingness to participate and informed consent were obtained before participating in the study. Participations were voluntary. Accuracy of inputting data and normality, extreme values, and the linearity of the data were controlled before performing the aimed analyses. After these procedures, it was determined that the data set had a normal curve and carried out the conditions for linearity.

Results

Intercorrelations Between Dream Themes, Defense Styles, Dysfunctional Attitudes, and Interpersonal Relationship Styles

The Negative Defense Mechanisms (Immature and Neurotic)— especially Imma-ture Defense Style—scales had largest correlation coefficient with negative dream themes (r⫽ .18 to .35, p ⬍ .01) except correlation between Neurotic Defense Style and Negative Themes subscale. DAS was significantly correlated with all of the DTS’s subscales, and the correlation coefficients varied between .19 and .26. Three of the DTS measures (Negative, Anxiety, and Fear Themes) varied positively with DAS, whereas Frustration Themes varied negatively with DAS. All of IRSI subscales correlated negatively with DTS subscales except Negative Themes, and correlation coefficients varied between .08 and .21 (Table 1).

Structural Equation Model

Lisrel 8.51 was used to examine the measurement and structural models. For each model, scores of the four negative subscales of DTS (Negative, Anxiety, Fear, and Frustration Themes) were used as the observed indicators of disturbing dream themes.

Table 1

Intercorrelations Between the Dream Themes Scale, 40-Item Defense Styles Questionnaire, Interpersonal Relationships Styles Inventory, and Dysfunctional Attitudes Scale

Dream Themes subscale Independent variables Negative Themes Anxiety Themes Fear Themes Frustration Themes Defense Mechanisms Immature .18** .28** .32** .35** Neurotic .06 .11* .10* .14** Dysfunctional Attitudes .23** .26** .24** ⫺.19**

Interpersonal Relationship Styles

Egocentric .02 ⫺.10* ⫺.10* ⫺.08

Depreciatory ⫺.07 ⫺.21** ⫺.24** ⫺.19**

Note. N⫽ 610. Rising scores on “Interpersonal relationship styles” indicate increasing positiveness on interpersonal relationships styles.

*p⬍ .05. **p⬍ .001. This document is copyrighted by the American Psychological Association or one of its allied publishers. This article is intended solely for the personal use of the individual user and is not to be disseminated broadly.

In addition, two observed indicators of defense mechanisms (Immature and Neurotic Defense Mechanisms subscales of DSQ-40), DAS subscales as indicators of dysfunc-tional attitudes, and IRSI subscale scores were analyzed. However, DAS scores were split in half randomly—the odd- and even-numbered items were divided in a random manner to form a parcel— because of their single factorial structure in the direction of

Coffman and MacCallum’s (2005)recommendation about item parceling in such cases.

A ratio of chi square to degrees of freedom (2/df); five indices to assess the

goodness of fit of the models, that is, the comparative fit index (CFI;ⱖ.90), the adjusted

goodness of fit index (AGFI; ⱖ.90), the incremental fit index (IFI; ⱖ.90), the

standardized root mean square residual (SRMR;ⱕ.08), and the root mean square error

of approximation (RMSEA; ⱕ.06; Hu & Bentler, 1999); the normed fit index

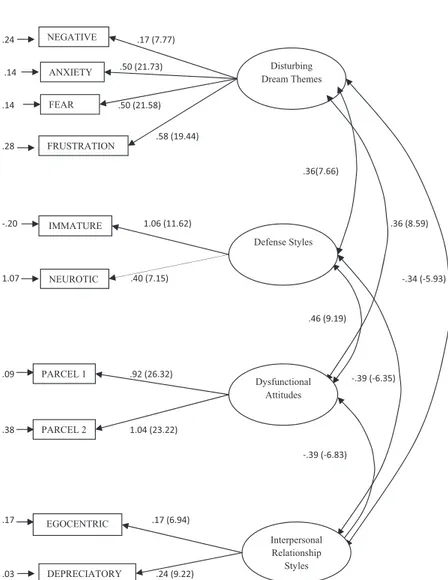

(NFI;ⱖ.90); the goodness of fit index (GFI; ⱖ.90); the parsimony normed fit index (PNFI;ⱖ.50); and the parsimony goodness of fit index (PGFI; ⱖ.50) are reported in subsequent analyses (Mulaik et al., 1989). Before testing the structural model, confirmatory factor analysis was used to ensure that the data fit the measurement model. The measurement model showed a good fit to the data and scaled2(38)⫽

91.85,2/df⬍ 3, RMSEA ⫽ .05, CFI ⫽ .97, IFI ⫽ .98, SRMR ⫽ .04, AGFI ⫽ .95,

NFI⫽ .97, PNFI ⫽ .63, GFI ⫽ .98, and PGFI ⫽ .55. The observed variable loadings on the latent variables were all significant at p⬍ .05. Therefore, the latent variables appear to have been adequately measured by their respective indicators (Figure 2).

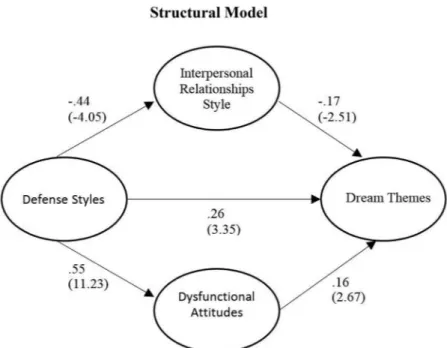

The hypothesized structural model provided a good fit to the data and scaled 2(30)⫽ 74.92, 2/df⬍ 3, RMSEA ⫽ .05, CFI ⫽ .98, IFI ⫽ .98, SRMR ⫽ .04, AGFI ⫽

.96, NFI⫽ .96, PNFI ⫽ .64, GFI ⫽ .98, and PGFI ⫽ .53. Together with negative defense styles, dysfunctional attitudes and interpersonal relationship styles explained 22% of the variance in disturbing dream themes (Figure 3).

Direct effects of the model. According to the analyzed structural equation

model, negative defense mechanisms had a direct positive effect on both disturbing dream themes as an independent variable (standardized, ⫽ .26, t ⫽ 3.79, p ⬍ .05), and dysfunctional attitudes (standardized,  ⫽ .55, t ⫽ 11.23, p ⬍ .05) and interpersonal relationships styles (standardized, ⫽ ⫺.44, t ⫽ 4.05, p ⬍ .05) as mediators. In addition to these direct effects, both the mediators, dysfunctional attitudes and interpersonal relationship styles, had a direct positive effect on the independent variable, disturbing dream themes (standardized, ⫽ .16, t ⫽ 2.67, p ⬍ .05, and standardized,  ⫽ ⫺.17, t ⫽ 2.51, p ⬍ .05, respectively). Even though  parameters of interpersonal relationship styles are negative, its effects should be interpreted as positive because of its rating system.

Indirect effects of the model. In the hypothesized model, in addition to the

direct effects spotted, indirect effects were observed to be significant. It was found that negative defense mechanisms also had an indirect effect on disturbing dream themes, mediated by dysfunctional attitudes and interpersonal relationships styles (standard-ized, ⫽ .16, t ⫽ 3.28, p ⬍ .05).

Discussion

According to the purpose of the research, at the first stage, the default factor structure formed by variables (measurement model) was tested. At the second stage, the proposed structural equation model was tested, and fit indices were

This document is copyrighted by the American Psychological Association or one of its allied publishers. This article is intended solely for the personal use of the individual user and is not to be disseminated broadly.

observed to be in the expected range for a good model. In other words, it can be said that the proposed model works.

The model analyzed in this study proposes that disturbing dream themes such as anxiety, fear, and frustration were positively predicted by immature and neurotic defense mechanisms such as projection, denial, displacement, rationalization, passive aggression, and somatization. In the related literature, two kinds of intertwined association between individual’s defense styles and dream themes have been consid-ered. These associations point out that dreams and dream themes are some kind of defense style that protects an individual’s ego integrity, and at the same time, dream

Measurement Model Disturbing Dream Themes NEGATIVE ANXIETY IMMATURE NEUROTIC PARCEL 1 PARCEL 2 EGOCENTRIC DEPRECIATORY .24 .14 1.07 .38 .09 .03 .17 .17 (7.77) .50 (21.73) .40 (7.15) .92 (26.32) 1.04 (23.22) .24 (9.22) .36(7.66) .36 (8.59) .46 (9.19) -.39 (-6.35) -.39 (-6.83) Defense Styles Dysfunctional Attitudes Interpersonal Relationship Styles -.20 .17 (6.94) FEAR FRUSTRATION .14 .28 1.06 (11.62) .50 (21.58) .58 (19.44) -.34 (-5.93)

Figure 2. Measurement model of the relationships between negative defense styles, dysfunctional attitudes, interpersonal relationship styles, and disturbing dream themes. Rising scores on Interpersonal Relationship Styles indicate increasing positiveness on interpersonal relationships styles.

This document is copyrighted by the American Psychological Association or one of its allied publishers. This article is intended solely for the personal use of the individual user and is not to be disseminated broadly.

content is formed by the filter of an individual’s defense mechanisms, especially by suppression (Bryant et al., 2011;Cartwright, 2010; Freud, 1899/1996; Geçtan, 2005;

Hartmann, 1998;Kröner-Borowik et al., 2013;Lichtenberg et al., 1992;Marcus, 2008;

Vogel, 1960). According to psychodynamic view, there is a compensative association

between dream themes and suppression. Freud (1899/1996) stated that the energy

created by suppressed material (desire and drives that cannot be expressed in awake life) is discharged and compensated in sleep via dreams. Ego psychology approach suggests that high levels of anxiety and aggression patterns in dreams of the individuals who frequently use the suppression defense style are compensative ego attempts in the process of adaptation for the awake life (Bell & Cook, 1998; Edwards, 1977). Consistent with the “avoidance motivational system” theory, self-psychology points that disturbing dream themes are compensative defense mechanisms for self-integrity

(Lichtenberg et al., 1992). In accordance with these views, Bell and Cook (1998)

indicated that dream content and themes vary according to the level of using suppression defense style, and individuals who frequently use suppression describe more aggressive and disturbing dream themes.Yu (2011a)similarly pointed out that intensity of emotion and theme in dreams are affected by an individual’s suppression frequency and are associated with somatization, which is one of the immature defense mechanisms. From the literature review, it is observed that studies focused on associations between defense mechanisms and dream content or themes emphasized on suppression (Bryant et al., 2011; Kröner-Borowik et al., 2013), so it can be Figure 3. Hypothesized structural model of the relationship between negative defense styles, dysfunc-tional attitudes, interpersonal relationship styles, and disturbing dream themes. Rising scores on Interpersonal Relationship Styles indicate increasing positiveness on interpersonal relationships styles. Path loadings for indicators were not included here, because they had been examined for significance when conducting the confirmatory factor analysis during the measurement-model testing (Weston & Gore, 2006). This document is copyrighted by the American Psychological Association or one of its allied publishers. This article is intended solely for the personal use of the individual user and is not to be disseminated broadly.

considered that there is almost no study that has examined the associations between dream themes or content and defense mechanisms except for suppression. However, in a study that analyzed associations between dream process and defense styles of individuals, it was pointed out that individuals who use suppression more frequently

use other immature defense mechanisms at a higher rate than other groups (Yu,

2011a). When considered in this context, it can be concluded that related literature may

underline the potential relationship between immature defense styles and disturbing dream themes.

The model analyzed in this study also proposes that disturbing dream themes are positively predicted by relationship styles including characteristics that inhibit interpersonal relationships. Such characteristics include being egocentric and depreciatory. Although no study was found to be a direct reference for the mentioned associations, in some studies, the reflection of interpersonal relation-ships and emotion and problems experienced in the context of these relationrelation-ships on dreams was emphasized (Blechner, 1998;Hill, Spangler, Sim, & Baumann, 2007;

Maggiolini, Cagnin, Crippa, Persico, & Rizzi, 2010;Mikulincer, Shaver, &

Avihou-Kanza, 2011; Weinberger, 1990). According to Maggiolini and colleagues (2010),

dream content or themes do not vary with waking life residuals including social interaction and interpersonal relationships. In other words, social interaction, situations, and emotions related to interpersonal relationships reflect on dreams. When considered in this context, it can be interpreted that dissatisfaction and negative emotions experienced in relationships of individuals who have a frustra-tive interpersonal relationship style reflect on dreams, or they are related with negative dream themes. According to another study with a closely related theme, individuals who want to establish rapport, but have difficulties about it, experience bonding anxiety closely related with high levels of seeking approval, fear of rejection, and dissatisfaction, and disturbing dream themes more frequently than other people (Mikulincer et al., 2011). It is known that these negative characteristics are closely related with frustrative interpersonal relationship styles (Bartholomew,

1990;Plutchik, 1997;Safran, 1990).

According to the model proposed in this study, disturbing dream themes are positively predicted by dysfunctional attitudes that are regarded as risk factors for psychopathology and interpersonal problems, too.Beck (1971/2002, p. 26) pointed out the reflections of an individual’s dysfunctional cognition and attitudes on dream themes, and he stated that dream work in psychotherapy is “a kind of biopsy of client’s psychological process.” In addition to these remarks, he indicated that dream theme and content are affected by dysfunctional cognition and attitudes that constitute cognitive patterns for depression. In a similar manner, Weissman and

Beck (1978)stated that dream themes are not unconscious processes, but instead,

they are a kind of process that can be measured and examined. And this view is exemplified via depression: A basic component that affects dream themes in depression is cognitive process, such as cognitions of imperfection and loneliness.

Freeman and White (2002)underlined the importance of dream work in forming

dysfunctional automatic negative thoughts and indicated that these thoughts affect dream themes. As can be understood from all these studies, this topic has been analyzed via depression instead of direct associations between dream themes and dysfunctional attitudes (Armitage, Rochlen, Fitch, Trivedi, & Rush, 1995;Barrett

& Loeffler, 1992; Beck & Ward, 1961; Cartwright, 1991; Kron & Brosh, 2003;

This document is copyrighted by the American Psychological Association or one of its allied publishers. This article is intended solely for the personal use of the individual user and is not to be disseminated broadly.

Soffer-Dudek, Shalev, Shiber, & Shahar, 2011). Given this context, it may be useful to point out the studies related with associations between dream themes and depression. Disturbing and threatening dreams, such as nightmares, and recurrent dreams are associated with low psychological well-being and depression (

Soffer-Dudek et al., 2011). In other studies, it is indicated that depressive individuals’

emotional dream contents change with antidepressant treatments; in addition to this, disturbing dream contents about stressors that trigger depression have more of an accelerator function than other contents. It is also stated that depressive individuals experience dreams themed anxious and/or unpleasant more frequently than nondepressive individuals (Armitage et al., 1995; Cartwright, 1991; Kron &

Brosh, 2003). Beck and Ward (1961) stated that severe depressive individuals’

dream themes have more masochistic components than those of nondepressive individuals.

The proposed model also reveals that individuals’ negative defense styles predict both a dysfunctional attitude and frustrative interpersonal relationship styles. Related literature supports this finding. Recently, some studies that reveal associations between defense styles and dysfunctional attitudes via various psychopathologies have been conducted (Coleman et al., 2010; Cras¸ovan, 2014; Hovanesian et al., 2009). For example,Cras¸ovan’s (2014)findings pointed positive correlations: in the male depres-sive group, between denial and dysfunctional attitudes; in the female depresdepres-sive group, between self-devaluation and dysfunctional attitudes; and for the entire depressive group, between withdrawal and dysfunctional attitudes. Similarly,Wenzlaff and Bates

(1998) also stated correlations between defense mechanisms and dysfunctional

atti-tudes. In addition to this finding, they underlined that depressive individuals’ cognitive predisposition toward depression can escape attention because of these individuals’ intense use of suppression, so therapists should be careful about it. At this point, it can be considered that if clients’ defense mechanisms that block dysfunctional attitudes and beliefs can be found out in therapies and worked on, this intervention will make significant contribution for healing.

Literature related to defense mechanisms and interpersonal relationship styles also supports the proposed model’s findings. As opposed to the defense mechanism definition based on urge in classical psychoanalysis, recently it is defined as a protector of self-worth and self-esteem and a blocker of negative emotional experiences. In addition to these emphasized functions, it is also indicated that defense mechanisms represent not only inner psychic processes but also interpersonal relationships (Cooper,

1998;Fenichel, 1945;Zeigler-Hill & Pratt, 2007). For example, a longitudinal study

revealed that mature defense mechanisms establish and maintain satisfied relationships

(Vaillant, 1992); nevertheless, immature defense mechanisms are associated with a

more negative style and outputs in interpersonal relationships, and more problems in marriage and romantic relationships (Bouchard & Theriault, 2003; Zeigler-Hill &

Pratt, 2007). Immature (isolation, devaluation, passive aggression, and projection)

defense styles are also correlated with introverted, distant, closed, and hostile inter-personal relationship styles (Zeigler-Hill & Pratt, 2007).

In addition to all these direct and indirect findings in related literature, it is remarkable that the number of studies that aim to analyze models that try to explain dream themes is limited. With a similar theme, only one study has aimed to improve the structural equation model of superego, affect, and dream functioning by incorporating positive instinctual emotions and more parameters (Yu, 2013).

This document is copyrighted by the American Psychological Association or one of its allied publishers. This article is intended solely for the personal use of the individual user and is not to be disseminated broadly.

The study revealed that superego functions such as defenses predict negative dream content via dream experiences.Yu’s (2013)findings are consistent with the present model in terms of its associations between defense mechanisms and disturbing dream themes.

Findings point out the significance of the proposed model, and the model reveals that immature defense mechanisms (projection, passive aggression, isola-tion, denial, devaluaisola-tion, displacement, rationalizaisola-tion, and somatization) affect disturbing dream themes, mediated by dysfunctional attitudes and frustrative interpersonal relationships styles. Binary associations that constitute the proposed model and that have been discussed thus far have rarely been studied in literature, so all of the implications in this section are interpreted via studies that have closely related topics. When the findings of the studies with closely related themes and their links with the proposed model are considered, it can be said that the proposed model and the related literature are consistent.

Clinical Implications

Dream works in psychotherapy have been suggested and became increasingly common as a supporter and as an alternative technique (Caperton, 2012;Crook & Hill,

2003;Eudell-Simmons & Hilsenroth, 2007). This study’s implications that may

contrib-ute to the process of psychotherapy and give some clues to psychotherapists are as follows: (a) Clients who express experiencing disturbing dreams frequently may use immature defense mechanisms such as projection, passive aggression, isolation, denial, devaluation, displacement, rationalization, and somatization. (b) If the clients who express experiencing disturbing dreams frequently have some dissatisfaction issues in their relationships, this connection may be via their egocentric and/or depreciatory interpersonal style. (c) While dysfunctional attitudes and beliefs of clients who express experiencing disturbing dreams frequently are being worked on, materials indicated by the previous two implications may be emphasized. (d) A decrease in disturbing dream experiences may be an indicator of the success of interventions to the previously mentioned topics (immature defense styles, dysfunctional attitudes, and frustrative interpersonal relationship style).

Even though studies about dream process are becoming increasingly common, it is seen that these studies are limited and the findings are still controversial. In this context, this study that analyzes multiple associations about dream themes—the usable aspects of the dream process as a material for psychotherapy—may be considered as the first of its kind within the related literature, as it offers important findings for the field.

It is known that variables that form the proposed model are concepts emphasized by different psychotherapy approaches. Defense mechanisms have arisen with psychodynamic theory and been a variable focused by researchers who internalize this approach more than others. However, dysfunctional attitudes and beliefs have been accepted as basic concepts of cognitive– behavioral therapy. As for interpersonal relationships, they constitute the new generation approaches’ focal point. Although the concept of “dream themes” has been rooted in psychody-namic approach, recently it has been accepted as a concept which aroused almost all of the new and old generation approaches’ interest. In this context, this study,

This document is copyrighted by the American Psychological Association or one of its allied publishers. This article is intended solely for the personal use of the individual user and is not to be disseminated broadly.

with its model proposal, has an integrative approach and addresses a wide range of implications.

Limitation and Suggestions

A total of 627 volunteers participated in this study via the Internet. Being conducted via the internet might be a limitation for the findings of the study. Although the analyses were performed by using the data of the 610 participants left after the required interventions and who were thought be fit to the patterns of the analyses and research ethics, the sample doesn’t scatter evenly among educational levels, as graduate and postgraduate participants dominate the sample. In addition to these limitations, the study has other limitations brought together with self-report-scale-type assessments.

References

Andrews, G., Singh, M., & Bond, M. (1993). The Defense Style Questionnaire. Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease, 181, 246 –256.http://dx.doi.org/10.1097/00005053-199304000-00006

Armitage, R., Rochlen, A., Fitch, T., Trivedi, M., & Rush, A. J. (1995). Dream recall and major depression: A preliminary report. Dreaming, 5, 189 –198.http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/h0094434 Barrett, D., & Loeffler, M. (1992). Comparison of dream content of depressed vs. nondepressed

dreamers. Psychological Reports, 70, 403–406.http://dx.doi.org/10.2466/pr0.1992.70.2.403

Bartholomew, K. (1990). Avoidance of intimacy: An attachment perspective. Journal of Social and Personal Relationships, 7, 147–178.http://dx.doi.org/10.1177/0265407590072001

Beck, A. T. (1997). The past and future of cognitive therapy. The Journal of Psychotherapy Practice and Research, 6, 276 –284.

Beck, A. T. (2002). Cognitive patterns in dreams and daydreams. Journal of Cognitive Therapy, 16, 23–27. (Reprinted from Dream dynamics: Science and psychoanalysis, Vol. 19. Scientific proceed-ings of the American Academy of Psychoanalysis, pp. 2–9, by J. H. Masserman, Ed., 1971, New York, NY: Grune & Stratton).

Beck, A. T., & Ward, C. H. (1961). Dreams of depressed patients. Characteristic themes in manifest content. Archives of General Psychiatry, 5, 462–467.http://dx.doi.org/10.1001/archpsyc.1961.01710170040004 Bell, A. J., & Cook, H. (1998). Empirical evidence for a compensatory relationship between dream

content and repression. Psychoanalytic Psychology, 15, 154 –163. http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/0736-9735.15.1.154

Blechner, M. J. (1998). The analysis and creation of dream meaning: Interpersonal, intrapsychic, and neurobio-logical perspectives. Contemporary Psychoanalysis, 34, 181–194. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/00107530.1998 .10746357

Bouchard, G., & Theriault, V. J. (2003). Defense mechanisms and coping strategies in conjugal relationships: An integration. International Journal of Psychology, 38, 79–90.http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/00207590244000214 Bryant, R. A., Wyzenbeek, M., & Weinstein, J. (2011). Dream rebound of suppressed emotional thoughts: The

influence of cognitive load. Consciousness and Cognition, 20, 515–522.http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.concog .2010.11.004

Caperton, W. (2012). Dream work in psychotherapy: Jungian, post-Jungian, existential-phenomenological, and cognitive-experiential approaches. Graduate Journal of Counseling Psychology, 3, 1–35.

Cartwright, R. D. (1991). Dreams that work: The relation of dream incorporation to adaptation to stressful events. Dreaming, 1, 3–9.http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/h0094312

Cartwright, R. D. (2010). The twenty-four hour mind: The role of sleep and dreaming in our emotional lives. New York, NY: Oxford University Press.

Çekmece, L. (2010). Bir geçerlik güvenirlik çalıs¸ması: Fonksiyonel olmayan tutumlar ölçeg˘i [A study of validity and reliability: Dysfunctional Attitudes Scale] (Unpublished master’s thesis). Ankara University, Ankara, Turkey.

Coffman, D. L., & MacCallum, R. C. (2005). Using parcels to convert path analysis models into latent variable models. Multivariate Behavioral Research, 40, 235–259.http://dx.doi.org/10.1207/s15327906mbr4002_4 Coleman, D., Cole, D., & Wuest, L. (2010). Cognitive and psychodynamic mechanisms of change in treated and

untreated depression. Journal of Clinical Psychology, 66, 215–228.http://dx.doi.org/10.1002/jclp.20645

This document is copyrighted by the American Psychological Association or one of its allied publishers. This article is intended solely for the personal use of the individual user and is not to be disseminated broadly.

Cooper, S. H. (1998). Changing notions of defense within psychoanalytic theory. Journal of Personality, 66, 947–964.http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/1467-6494.00038

Cramer, P., Blatt, S. J., & Ford, R. Q. (1988). Defense mechanisms in the anaclitic and introjective personality configuration. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 56, 610 –616. http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/0022-006X.56.4.610

Cras¸ovan, D. I. (2014). Psychological defense mechanisms associated with dysfunctional attitudes in non-psychotic major depressive disorder. Cognition, Brain, Behavior: An Interdisciplinary Journal, 18, 39 –53.

Crook, R. E., & Hill, C. E. (2003). Working with dreams in psychotherapy: The therapists’ perspective. Dreaming, 13, 83–93.http://dx.doi.org/10.1023/A:1023350025033

Edwards, N. (1977). Dreams, ego psychology, and group interaction in analytic group psychotherapy. Group, 1, 32–47.http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/BF02382983

Eudell-Simmons, E. M., & Hilsenroth, M. J. (2007). The use of dreams in psychotherapy: An integrative model. Journal of Psychotherapy Integration, 17, 330 –356.http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/ 1053-0479.17.4.330

Euler, J., Henkel, M., Bock, A., & Benecke, C. (2016). Strukturniveau, Abwehr und Merkmale von Träumen. [Structural level, defence and characteristics of dreams]. Forum der Psychoanalyse, 32, 267–284.http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s00451-016-0243-x

Fenichel, O. (1945). The psychoanalytic theory of neurosis. New York, NY: Norton.

Freeman, A., & White, B. (2002). Dreams and the dream image: Using dreams in cognitive therapy. Journal of Cognitive Psychotherapy, 16, 39 –53.http://dx.doi.org/10.1891/jcop.16.1.39.63706 Freud, A. (1966). The ego and the mechanisms of defense. New York, NY: International Universities

Press.

Freud, S. (1996). Düs¸lerin yorumu I [Interpretation of dreams I] (E. Kapkın, Trans.). I˙stanbul, Turkey: Payel Yayınevi. (Original work published 1899)

Geçtan, E. (2005). Psikanaliz ve sonrası [Psychoanalyses and after] (11th ed.). I˙stanbul, Turkey: Metis Yayınları.

Genç, A., Koçak, R., Çelikel, F. Ç., & Bas¸ol, G. (2013). Rüya temaları ölçeg˘i: Geçerlik ve güvenirlik çalıs¸ması [Development, validity and reliability of the Dream Themes Scale]. The Journal of Academic Social Science Studies, 6, 293–308.

Greenberg, R., Katz, H., Schwartz, W., & Pearlman, C. (1992). A research-based reconsideration of the psychoanalytic theory of dreaming. Journal of the American Psychoanalytic Association, 40, 531–550.http://dx.doi.org/10.1177/000306519204000211

Hall, C. S., & Nordby, V. J. (1972). The individual and his dreams. New York, NY: Signet. Hartmann, E. (1998). Dreams and nightmares. New York, NY: Plenum Press.

Hill, C. E., Gelso, C. H., Gerstenblith, J., Chui, H., Pudasaini, S., Burgard, J., . . . Huang, T. (2013). The dreamscape of psychodynamic psychotherapy: Dreams, dreamers, dream work, consequences and case studies. Dreaming, 23, 1–45.http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/a0032207

Hill, C. E., & Knox, S. (2010). The use of dreams in modern psychotherapy. International Review of Neurobiology, 92, 291–317.http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S0074-7742(10)92013-8

Hill, C. E., Spangler, P., Sim, W., & Baumann, E. (2007). Interpersonal content of dreams in relation to the process and outcome of single sessions using the Hill dream model. Dreaming, 17, 1–19. http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/1053-0797.17.1.1

Hovanesian, S., Isakov, I., & Cervellione, K. L. (2009). Defense mechanisms and suicide risk in major depression. Archives of Suicide Research, 13, 74 –86.http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/13811110802572171 Hu, L., & Bentler, P. M. (1999). Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: Conventional criteria

versus new alternatives. Structural Equation Modeling, 6, 1–55.http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/10705519909540118 Jöreskog, K. G., & Sörbom, D. (2001). LISREL 8.51 for Windows [Computer Software]. Lincolnwood,

IL: Scientific Software International, Inc.

Kron, T., & Brosh, A. (2003). Can dreams during pregnancy predict postpartum depression? Dreaming, 13, 67–81.http://dx.doi.org/10.1023/A:1023397908194

Kröner-Borowik, T., Gosch, S., Hansen, K., Borowik, B., Schredl, M., & Steil, R. (2013). The effects of suppressing intrusive thoughts on dream content, dream distress and psychological parameters. Journal of Sleep Research, 22, 600 –604.http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/jsr.12058

Kwon, P. (1999). Attributional style and psychodynamic defense mechanisms: Toward an integrative model of depression. Journal of Personality, 67, 645–658.http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/1467-6494.00068 Lichtenberg, J. D., Lachmann, F. M., & Fosshage, J. L. (1992). Self and motivational systems: Toward a

theory of psychoanalytic technique. Hillsdale, NJ: Analytic Press.

Maggiolini, A., Cagnin, C., Crippa, F., Persico, A., & Rizzi, P. (2010). Content analysis of dreams and waking narratives. Dreaming, 20, 60 –76.http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/a0018824

Marcus, S. M. (2008). Depression during pregnancy: Rates, risks and consequences—Motherisk Update 2008. The Canadian Journal of Clinical Pharmacology, 16, 15–22.

This document is copyrighted by the American Psychological Association or one of its allied publishers. This article is intended solely for the personal use of the individual user and is not to be disseminated broadly.

Mikulincer, M., Shaver, P. R., & Avihou-Kanza, N. (2011). Individual differences in adult attachment are systematically related to dream narratives. Attachment and Human Development, 13, 105–123. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/14616734.2011.553918

Moffit, A., Kramer, M., & Hoffman, R. (Eds.). (1993). The functions of dreaming. Albany, NY: SUNY Press.

Mulaik, S. A., James, L. R., Van Alstine, J., Bennett, N., Lind, S., & Stilwell, C. D. (1989). Evaluation of goodness-of-fit indices for structural equation models. Psychological Bulletin, 105, 430 –445. http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/0033-2909.105.3.430

Mulder, R. T., Joyce, P. R., Sellman, J. D., Sullivan, P. F., & Cloninger, C. R. (1996). Towards an understanding of defense style in terms of temperament and character. Acta Psychiatrica Scandi-navica, 93, 99 –104.http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1600-0447.1996.tb09809.x

Nielsen, T. A., Zadra, A. L., Simard, V., Saucier, S., Stenstrom, P., Smith, C., & Kuiken, D. (2003). The typical dreams of Canadian university students. Dreaming, 13, 211–235. http://dx.doi.org/10.1023/B:DREM .0000003144.40929.0b

Perry, J. C., & Cooper, S. H. (1992). What do cross-sectional measures of defense mechanisms predict. In G. E. Vaillant (Ed.), Ego mechanisms of defense: A guide for clinicians and researchers (pp. 195–216). Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association.

Plutchik, R. (1997). The circumplex as a general model of the structure of emotions and personality. In R. Plutchik & R. H. Conte (Eds.), Circumplex models of personality and emotions (pp. 17–45). Washington, DC: American Psychological Association Press.http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/10261-001 Rosner, R. I. (2004). Cognitive therapy and dreams. New York, NY: Springer Publishing.

Safran, J. D. (1990). Towards a refinement of cognitive therapy in light of interpersonal theory: I. Theory. Clinical Psychology Review, 10, 87–105.http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/0272-7358(90)90108-M S¸ahin, N. H., Durak, A., & Yasak, Y. (1994). Kis¸ilerarası ilis¸kiler ölçeg˘i: Psikometrik özellikleri

[Interpersonal Relationships Styles Inventory: Psychometric properties]. Paper presented at the VIII National Psychology Congress, I˙zmir, Turkey.

S¸ahin, N. H., & S¸ahin, N. (1989, June). Psychometric properties of the Dysfunctional Attitude Scale (DAS). Paper presented at the World Congress of Cognitive Therapy, Oxford, United Kingdom. S¸ahin, N. H., & S¸ahin, N. (1992, June). Adolescent guilt, shame, and depression in relation to sociotropy and autonomy. Paper presented at the World Congress of Cognitive Therapy, Toronto, Canada. Schweickert, R. (2007). Social networks of characters in dreams. In D. Barrett & P. McNamara (Eds.),

Praeger perspectives. The new science of dreaming: Vol. 3. Cultural and theoretical perspectives (pp. 277–297). Westport, CT: Praeger/Greenwood.

Soffer-Dudek, N., Shalev, H., Shiber, A., & Shahar, G. (2011). Role of severe psychopathology in sleep-related experiences: A pilot study. Dreaming, 21, 148 –156.http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/a0022865 Spinhoven, P., & Kooiman, C. G. (1997). Defense style in depressed and anxious psychiatric outpatients: An explorative study. Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease, 185, 87–94. http://dx.doi.org/10.1097/00005053-199702000-00004

Tien, H. L. S., Chen, S. C., & Lin, C. H. (2009). Helpful components involved in the cognitive-experiential model of dream work. Asia Pacific Education Review, 10, 547–559.http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s12564-009-9042-z Ungerer, J. A., Waters, B., Barnett, B., & Dolby, R. (1997). Defense style and adjustment in interpersonal

relationships. Journal of Research in Personality, 31, 375–384.http://dx.doi.org/10.1006/jrpe.1997.2192 Vaillant, G. E. (1992). Ego mechanisms of defense: A guide for clinicians and researchers (1st ed.).

Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Press, Inc.

Vaillant, G. E., Bond, M., & Vaillant, C. O. (1986). An empirically validated hierarchy of defense mechanisms. Archives of General Psychiatry, 43, 786–794.http://dx.doi.org/10.1001/archpsyc.1986.01800080072010 Van de Castle, R. L. (1991). A brief perspective on Calvin Hall: Commentary on Hall’s paper. Dreaming,

1, 99 –102.http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/h0094322

Vogel, G. (1960). Studies in psychophysiology of dreams. III. The dream of narcolepsy. Archives of General Psychiatry, 3, 421–428.http://dx.doi.org/10.1001/archpsyc.1960.01710040091011

Weinberger, D. (1990). The construct validity of the repressive coping style. In J. Singer (Ed.), Repression and dissociation (pp. 337–386). Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press.

Weissman, A. N., & Beck, A. T. (1978). Development and the validation of the Dysfunctional Attitude Scale: A preliminary investigation. Paper presented at the Annual Meeting of The American Educational Research Association, Toronto, Ontario, Canada.

Wenzlaff, R. M., & Bates, D. E. (1998). Unmasking a cognitive vulnerability to depression: How lapses in mental control reveal depressive thinking. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 75, 1559 –1571.http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.75.6.1559

Weston, R., & Gore, P. A., Jr. (2006). A brief guide to structural equation modeling. The Counseling Psychologist, 34, 719 –751.http://dx.doi.org/10.1177/0011000006286345

Yılmaz, N., Gençöz, T., & Ak, M. (2007). Psychometric properties of the Defense Style Questionnaire: A reliability and validity study. Turkish Journal of Psychiatry, 18, 244 –253.

This document is copyrighted by the American Psychological Association or one of its allied publishers. This article is intended solely for the personal use of the individual user and is not to be disseminated broadly.

Yu, C. K. C. (2011a). The mechanisms of defense and dreaming. Dreaming, 21, 51–69.http://dx.doi.org/10 .1037/a0022867

Yu, C. K. C. (2011b). Pain in the mind: Neuroticism, defense mechanisms, and dreaming as indicators of hysterical conversion and dissociation. Dreaming, 21, 105–123.http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/a0023057 Yu, C. K. C. (2013). The structural relations between the superego, instinctual affect, and dreams.

Dreaming, 23, 145–155.http://dx.doi.org/10.1037/a0032606

Zeigler-Hill, V., & Pratt, D. W. (2007). Defense styles and the interpersonal circumplex: The interpersonal nature of psychological defense. Journal of Psychiatry, Psychology and Mental Health, 1, 1–15. This document is copyrighted by the American Psychological Association or one of its allied publishers. This article is intended solely for the personal use of the individual user and is not to be disseminated broadly.

View publication stats View publication stats