Background: The aim of this study is to determine the relationship between healthy lifestyles behaviours and health‑related quality of life (HRQOL) among Turkish school‑going adolescents. Subjects and Methods: This cross‑sectional study was conducted among 413 students studying in a secondary school of Istanbul, Turkey. Data were collected using a questionnaire containing socio‑demographic characteristics, health promoting lifestyle behaviors and the Turkish generic health‑related quality of life questionnaire for children (Kid‑KINDL). Data were analyzed using descriptive statistics, t‑test, Pearson’s product‑moment correlation, and a hierarchical multiple regression analysis. Results: Univariate statistics

showed that gender, school grade, parental education level, monthly income, and all healthy lifestyles behaviours except for fruit and vegetable intake were associated with adolescents’ HRQOL. Multivariate statistics indicated that participation in social activities and talking about their problems were the most important predictors of better HRQOL. Healthy lifestyles behaviours, especially talking about their problems to close friends and/or family members and participation in leisure‑time social activity were related to better HRQOL of Turkish adolescents, independently of socio‑demographic factors. Conclusion: Collaborative efforts among providers of school health and counseling services are urgently needed to improve all aspects of adolescent health.

Keywords: Health‑related quality of life, healthy lifestyle behaviors, school‑going adolescent, school nursing, socio‑demographic

Relationship between Healthy Lifestyle Behaviors and Health Related

Quality of Life in Turkish School‑going Adolescents

N İlhan, K Peker1, G Yıldırım2, G Baykut3, M Bayraktar3, H Yıldırım3

Address for correspondence: Dr. N İlhan,

Department of Nursing, Faculty of Health Sciences, Bezmialem Vakif University, Merkez Mahallesi Silahtarağa Caddesi, No:189 (İgdaş G.Müdürlüğü Karşısı) Eyüp, İstanbul, Turkey. E‑mail: nilhan@bezmialem.edu.tr

improve adolescents’ daily lives in schools by focusing on protective factors that promote young people’s well‑being.[6,7]

In reality however, adolescence is a time when health problems such as nutritional issues, lack of adequate physical exercise, smoking, alcohol and substance abuse, violence, suicide and unwanted pregnancies are commonly encountered. Adolescents rarely use preventive services. In addition, they generally use

Introduction

A

dolescence is the transition period from childhood into adulthood which is characterized by rapid physical growth, sexual development, and psychosocial maturation.[1,2] The World Health Organization (WHO)identifies adolescents as between the ages 10 and 19, and refers to ages 15–24 as youth, and to the ages 10–24 as young people.[3] While 1.2 million adolescents

make up 16% of the world population, adolescents in the 10–19 age group constitute 15.97% of the population in Turkey.[4,5] Since adolescents are a demographic force

and represent the future state of health, importance, and priority should be given to improving the health of this age group.[2] For this reason, public health interventions

and policies integrated within the life course approach and the comprehensive action agenda are needed to Department of Nursing,

Faculty of Health Sciences, Bezmialem Vakif University, 1Department of Dental Public Health, Faculty of Dentistry, Istanbul University, Çapa, 2Department of Nursing, School of Health Sciences, İstanbul Gelişim University, 3Department of Nursing, School of Nursing, Halic University, İstanbul, Turkey

Abstract

This is an open access journal, and articles are distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution‑NonCommercial‑ShareAlike 4.0 License, which allows others to remix, tweak, and build upon the work non‑commercially, as long as appropriate credit is given and the new creations are licensed under the identical terms.

For reprints contact: reprints@medknow.com

How to cite this article:İlhan N, Peker K, Yildirim G, Baykut G,

Bayraktar M, Yildirim H. Relationship between healthy lifestyle behaviors and health related quality of life in turkish school‑going adolescents. Niger J Clin Pract 2019;22:1742‑51.

Access this article online

Quick Response Code:

Website: www.njcponline.com DOI: 10.4103/njcp.njcp_190_19 PMID: ******* Received: 05-Apr-2019; Revision: 05-Jun-2019; Accepted: 17-Aug-2019; Published: 03-Dec-2019

health services due to acute and chronic diseases. This health service utilization pattern of adolescents may lead to neglected health problems among adolescents.[1,2,8‑10]

Their unhealthy behaviors may be long‑term risk factors for chronic conditions in adulthood.[2] In our

country and in many countries, lack of access to quality services, maltreatment, insufficient physical activity and unhealthy diets are negatively affecting health among this vulnerable group.[11] Although there is some

positive news concerning adolescent behavior, fewer one in four adolescents meets recommended guidelines for physical activity; in some countries, as many as one in every three is obese.[1,12] This is the time when

adolescents seek independence so that they can make their own lifestyle decisions. These decisions may have a long‑term effect on the adolescent’s health and wellbeing.[13] In this context, schools are an effective

setting to implement health promotion programmes and to increase awareness of healthy lifestyle and its impacts on health of adolescents.[1,6,14]

Adoption of healthy lifestyle behaviors by adolescents helps prevent the development of many preventable lifestyle‑related chronic diseases of later adulthood[3,5]

and results in improved health‑related quality of life (HRQOL). [15‑17] It is known that HRQOL is a

multi‑dimensional concept related to the perception of an individual’s wellbeing in the context of physical, mental, and social functionality levels. Measuring HRQOL in adolescent, is increasingly seen as a useful indicator of health outcomes and health services effectiveness.[8]

Numerous studies have been conducted to examine the factors affecting the HRQOL of adolescents. Being boys,[13,18‑21] higher family socio‑economic status and

prosperity,[19,22‑24] having positive relationships with

friends,[25] higher levels of physical activity,[21,26‑29] and

good sleep quality[30,31] were found to be associated with

better adolescents’ HRQOL.

Although in recent years there has been a growing interest in assessing the HRQOL of adolescents, there are relative small number of studies examining the relationship between HRQOL and healthy lifestyle behaviors among school‑going adolescents. These studies reported that healthy lifestyle behaviors were significantly associated with better HRQOL among these adolescents.[15‑17]

Although many developing countries had well‑articulated and well‑staffed school‑based health programs, school health programs are often ignored because of lack of the necessary legal arrangements to clarify responsibilities, time, and training in Turkey.[32,33] Recently, Turkish

researchers have been paying more attention to examine the health promoting behaviors and its determinants

among school‑aged adolescents for developing school health programs.[32,34,35]

Despite growing awareness of the importance of HRQOL assessment for Turkish adolescents, much of the research to date has focused on specific diseases. To the best of our knowledge, in Turkey, few studies have attempted to identify predictors of HRQOL among these adolescents.[21,22] Consequently, little is known about the

relationship between health behavior patterns and their association with HRQOL as well as socio‑structural factors in Turkish adolescents. Information about lifestyles and adolescent HRQOL is useful for planning health promotion programs that aim to raise awareness about the importance of lifestyle and to motivate them to adapt the healthy lifestyles.[15,19]

Therefore, in this study, we aim to examine the association between healthy lifestyle behaviors and HRQOL among a sample of Turkish school‑going adolescents. The following research questions were addressed: (i) Are there differences in the HRQOL of adolescents in terms of socio‑demographic variables and healthy lifestyle behaviors? and (ii) What are the most important predictors of the HRQOL in Turkish school‑going adolescents?

Subjects and Methods

Participants

This cross‑sectional survey was carried out between October and December 2012 in students attending a public secondary school of Istanbul. Study sample comprised of 413 students in 6th, 7th, and 8th classes.

This study was incorporated within the ongoing school health promotion program performed by the Nursing Department of University.

Human subject protection and procedures

Study approval was first obtained from Istanbul Provincial Directorate for National Education. This study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki. Primary investigator visited each classroom and distributed the informed parent consent and child assent forms for students to take home to their parents. Parents signed the informed consent form at home, then returned them to school via students. The students completed their questionnaire after the parents gave informed consent. The students were informed by the same investigator about the nature of the study and were instructed that participation was voluntary and information was confidential and anonymous. Students completed the self‑report instruments in their classrooms during school hours.

The study included students aged 11–13 years who were present on the study day and whose parents authorized

participation. The criteria of exclusion were: absence on the study day, having a vision, hearing and cognitive problem, and incomplete questionnaire data.

Using an online calculator, the minimum sample size needed for multiple regression analysis was calculated to be 162 participants based on the following assumptions: medium effect size of 0.15, a power of 0.90, 13 predictors, and an alpha of 0.5.[36] Consent/assent was

obtained for 413 students (83%) who were subsequently enrolled in the study. Of the 497 eligible adolescents, 44 (9%) did not provide written permission from their parents, 28 (6%) were absent from school on the day of the study, and 12 (2%) did not want to participate. Measures

The study questionnaire with two sections was specifically designed for the study. The first section contained questions on socio‑demographic characteristics of adolescents and their parents including adolescents’ age, gender, school grade, parents’ education, monthly household income. Monthly income was standardized according to the number of family members and was divided into 4 quartile groups: lowest, lower middle, higher middle, and highest. Monthly income was measured in Turkish Lira (TRY) and categorized into four groups regarding the income clusters, which was used in the research on family structure in Turkey as follows; lowest (≤ 600 TRY), lower middle (601 and 1200 TRY), higher middle (1201 and 2500 TRY), and highest ((>2500 TRY).[37] In 2012, 1 US Dollar

was equal to 1.80 TRY. Education level was assessed according to the number of years of formal schooling in Turkey and classified into two categories: ≤8 years of schooling and >8 years of schooling. The second section was composed of healthy lifestyle behaviors and the Turkish version of the generic health‑related quality of life questionnaire for children (Kid‑KINDL).

The Turkish Kid‑KINDL (7–13 years)

This scale was used to assess the HRQOL of adolescents.[38] This measure consist of 24 items with a

5 point Likert scale (from 1= “never” to 5= “always”) which include six subscales: Physical well‑being, emotional well‑being, self‑esteem, family, friends, and school. The raw score are transformed into a 0‑100 scale, with higher scores indicating better HRQOL. Healthy lifestyle behaviors

Items related to healthy lifestyle behaviors were identified through a review of relevant literature and included doing psyhical exercise three times a week, having a breakfast, milk consumption, fruit and vegetable intake, sleeping, fast food consumption, leisure time social activity, and talking about their problems to close

friends and family members. Exercise was measured with asking students whether they do exercise 3 days in a week or not.[39] Sleep duration was assessed by the

question, “On an average school night, how many hours of sleep do you get?”. Responses were collapsed into two categories: short sleepers (<8 hours); and adequate sleepers (≥8 hours) according to the recent study.[40]

Fruit and vegetable intake was assessed assessed via the following question: “How many servings of fruit and vegetables do you usually eat on a typical day? Responses were classified into two categories pleasent (≥5 servings per day); and unpleasent (<5 servings per day).[41] Leisure time social activity was

measured using the item “Outside school hours: How often do you participate in social activities that include visiting someone you know, receiving a visit, being out for more than two hours with friends, being at a meeting or training in an organisation or a club.[42] It was rated

on a 4 ‑point Likert scale (from 1= ”Not once” to 4= ” 4 times or more in the last week”) Fast food consumption was measured using a self – report item “How often do you consume fast food (i.e. hamburgers, cheeseburgers, fried chicken, and pizza)?”. It was rated on a 4‑point likert scale (from 1= “never” to 4= ”daily”).[43] Other

health‑promoting behaviors (having a breakfast, milk consumption, talking about their problems to close friends and family members) were also assessed using scale items drawn from the Adolescent Life Style Profile II. These items are rated on a 4‑point Likert scale (from 1= “never” to 4= “routinely”).[44]

Statistical analysis

Descriptive statistics were used for the socio‑demographics variables and health behaviors of the children. The scores one the five subscales and the overall scores on the Kid‑KINDL were continuous variables, and the Kolmogorov‑Smirnov test revealed that all the scores of this scale were within a normal distribution. Internal consistency of Kid‑KINDL was evaluated using the Cronbach alpha. Before conducting the main study, the Item‑level Content Validity Index (I‑CVI) was calculated by an expert panel comprising three academicians in nursing to evaluate the content validity of healthy lifestyle behaviors. They

rated each item based on its relevance using a four‑point Likert scale[1–4], representing low to high agreement. I‑CVI was computed as the proportion of all the “somewhat relevant (3)” and “very relevant (4)” divided by the number of respondents and items with a I‑CVI score higher than 0.80 were accepted as content valid.[45]

Test‑retest reliability of of selected items was evaluated using intraclass correlation coefficients (ICC) with an interval of 14 days. Study sample size was calculated

based on the following assumption: the minimum acceptable ICC is above 0.80 with an anticipated true reliability of 0.90 at α = 0.05 and β = 0.20, a sample size of 46 children was required.[46]

To explore the differences between the two groups according to sociodemographic and behavioral characteristics of adolescents, the independent sample t‑test was used for dichotomous variables and Pearson’s correlation coefficient for continous variables. Pearson’s correlation coefficients were classified as very weak (r < 0.20), weak (r = 0.20–0.39), moderate (r = 0.40–0.59), strong (r = 0.60–0.79), and very strong (r > 0.80).[47]

To determine the best set of predictors of HRQOL in adolescents, the hierarchical multiple regression with enter method was conducted. In these analyses, the Kid‑KINDL scores were used as dependent variables. The independent variables were entered in the following steps: The socio‑demographic variables was entered into the first block, and the health –promoting behaviors in block 2. The magnitude of R2 change at each step was used to

determine the variance explained by each set of variables. Statistical significance was achieved when P < 0.05. Statistical analysis was performed using IBM SPSS Statistics 19 for Windows (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA).

Results

Sociodemographic and behavioral characteristics of study sample

The mean age of 413 students included in the study was 12.43 ± 0.71 years (range of 11–13 years). Among these, 34% were 8th graders, 53% were female, 47%

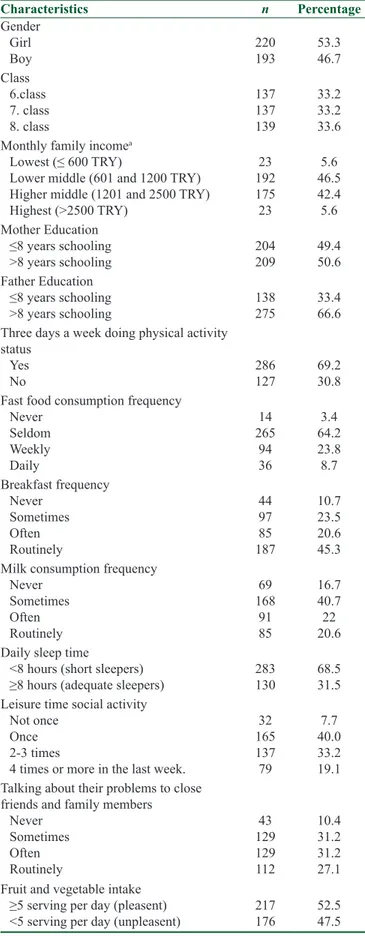

were in the lower middle income group, 49.4% of the mothers were educated for 8 years or less, 69% reported participation in physical activity three days a week, 64% consumed fast‑food seldom, 45% had regular breakfast, 41% sometimes drank milk, 69% were short sleepers, 31% sometimes talked to their family and other people about their problems, and 40% attended social activities occasionally [Table 1]

Content validity and test‑retest reliability of health behavior items

All items had an acceptable item‑level CVI ≥ 0.80.[45]

According to Landis and Koch criteria, all items indicated almost perfect reliability (the values of ICC ranged 0.83–1.00).[48]

Differences in HRQOL according to

socio‑demographics and behavioral characteristics

As shown in Table 2, girls reported higher scores on the self‑esteem and school subscales than boys (P < 0.05).

Table 1: Socio‑demographic Characteristics and Health Promoting Behaviors of Turkish Adolescents

Characteristics n Percentage Gender Girl Boy 220193 53.346.7 Class 6.class 7. class 8. class 137 137 139 33.2 33.2 33.6 Monthly family incomea

Lowest (≤ 600 TRY) Lower middle (601 and 1200 TRY) Higher middle (1201 and 2500 TRY) Highest (>2500 TRY) 23 192 175 23 5.6 46.5 42.4 5.6 Mother Education ≤8 years schooling ˃8 years schooling 204209 49.450.6 Father Education ≤8 years schooling ˃8 years schooling 138275 33.466.6

Three days a week doing physical activity status

Yes

No 286127 69.230.8

Fast food consumption frequency Never Seldom Weekly Daily 14 265 94 36 3.4 64.2 23.8 8.7 Breakfast frequency Never Sometimes Often Routinely 44 97 85 187 10.7 23.5 20.6 45.3 Milk consumption frequency

Never Sometimes Often Routinely 69 168 91 85 16.7 40.7 22 20.6 Daily sleep time

<8 hours (short sleepers)

≥8 hours (adequate sleepers) 283130 68.531.5 Leisure time social activity

Not once Once 2‑3 times

4 times or more in the last week.

32 165 137 79 7.7 40.0 33.2 19.1 Talking about their problems to close

friends and family members Never Sometimes Often Routinely 43 129 129 112 10.4 31.2 31.2 27.1 Fruit and vegetable intake

≥5 serving per day (pleasent)

<5 serving per day (unpleasent) 217176 52.547.5 aMonthly Family Income measured in TRY

Table 2: The relationship between the Kid‑KINDL scores and socio‑demographic factors

Socio-demographic factors Kid‑KINDL

Physical well‑being Emotional well‑being Self-esteem Friends School Kid‑KINDL Total Mean±SD Mean±SD Mean±SD Mean±SD Mean±SD Mean±SD

Adolescent gender Girl (n=220) 66.73±21.32 74.74±18.45 64.34±22.82 69.11±19.10 65.05±20.10 68.00±14.07 Boy (n=193) 66.28±20.44 72.76±18.76 59.39±24.41 69.59±15.95 60.26±18.75 65.66±12.51 Pa 0.830 0.281 0.034 0.787 0.013 0.077 Monthly income, r 0.09 0.12* 0.13** 0.11* 0.08 0.16** Class, r ‑0.12* ‑0.03 ‑0.10* ‑0.05 ‑0.17** ‑ 0.14**

Mother’s educational level ≤ 8 years of schooling

(n=204) 66.13±13.65 66.42±21.24 72.58±19.09 60.77±24.28 68.64±17.68 62.64±19.93

> 8 years of schooling

(n=209) 68.72±12.64 66.76±20.12 76.72±17.09 64.98±22.01 70.98±17.62 64.17±18.81

Pa 0.072 0.878 0.038 0.098 0.218 0.360

Father’s educational level ≤ 8 years of schooling

(n=138) 66.23±13.58 67.88±21.11 72.19±19.79 60.20±24.36 68.82±17.38 62.06±19.16

> 8 years of schooling

(n=275) 67.88±13.11 64.54±20.46 76.19±16.47 64.69±22.44 70.08±18.13 63.91±20.24

Pa 0.219 0.111 0.032 0.058 0.477 0.347

aStatistical evaluation by the independent sample t test; r, The Pearson product moment correlation coefficient

Table 3: The relationship between the Kid‑KINDL scores and healthy lifestyle behaviors

Healthy Lifestyle Behaviors Kid‑KINDL Physical WB

Mean±SD WB Mean±SDEmotional Self-esteem Mean±SD Mean±SDFriends Mean±SDSchool Total Mean±SDKid‑KINDL

Sleep duration

≥8 hours (n=130) 71.82±21.02 76.25±19.00 63.75±26.38 69.37±17.79 67.06±18.80 69.65±13.80

<8 hours (n=283) 64.09±20.41 72.70±18.33 61.24±22.33 69.32±17.66 60.86±19.68 65.64±13.04

Pa <0.001 0.072 0.318 0.978 0.003 0.005

Fruit and vegetable intake ≥5 ser. per day (n=217) < 5 ser. per day (n=176)

66.29±21.67 66.83±19.85 73.73±18.68 73.93±18.54 63.84±23.19 59.58±24.17 70.78±17.69 67.40±17.52 63.31±20.40 62.14±18.51 67.59±13.64 65.98±13.04 P valuea 0.797 0.914 0.071 0.055 0.548 0.226

Three days a week doing physical activity status

Yes (n=286) 67.28±20.67 75.13±18.21 63.70±24.19 69.95±18.03 63.89±19.70 67.99±13.50

No (n=127) 64.81±21.35 70.86±19.86 58.26±22.10 67.96±16.85 60.38±19.22 64.45±12.88

Pa 0.268 0.035 0.031 0.292 0.093 0.013

Milk consumption frequency, r 0.06 0.09 0.13* 0.12* 0.14** 0.16**

Having breakfast, r 0.05 0.05 0.10* 0.04 0.12* 0.11*

Fast‑food consumption, r ‑0.09 ‑0.02 ‑0.04 ‑0.03 ‑0.10* ‑0.09

Talking about their problems to close friends

and family members, r 0.08 0.21** 0.31** 0.16* 0.21** 0.30**

Leisure time social activity, r 0.08 0.17** 0.27** 0.20** 0.15** 0.26**

aStatistical evaluation by the independent sample t test; r, The Pearson product moment correlation coefficient Aadolescents whose parents had 8 years or less of

formal schooling reported lower scores on the self esteem subscale than the adolescents whose parents had higher than 8 years of formal education. School grades correlated negatively and weakly with the

Kid‑KINDL total scale and its subscales of physical well‑being, self‑esteem, and school. Higher scores in the Kid‑KINDL total scale and its subscales of self‑esteem, friends, and emotional well‑being were associated with higher mmonthly incomes.

As shown in Table 3, shorter sleepers reported significantly lower scores on the Kid‑KINDL total scale and its two subscales of physical well‑being and school than those slept more than 8 hour per day. Adolescents who reported they participated in physical activity three days a week scored higher on the Kid‑KINDL total scale and its subscales of self‑esteem and emotional well‑being than their counterparts who did not participated in physical activity 3 days a week.

We found a negative correlation between the frequence of fast food consumption and the school subscale scores. Having breakfast was weakly and positively correlated with the Kid‑KINDL total scale and its subscales of self‑esteem and school. Milk consumption frequency was correlated the Kid‑KINDL total scale and it’s all subscales except emotional well‑being and physical well‑being.

Participation in leisure time social activities and talking about their problems were correlated with the total score of the Kid‑KINDL and its four subscale scores: self‑esteem, school, friends, and emotional well‑being. Finally, a hierarchical multiple regression was conducted to determine the best set of predictors for the HRQOL. In the first block, SES and school grades were significantly related to the dependent variable and they explained

4.8% of the variance for self‑reported HRQOL. Participation in social activities and talking about their problems were the strongest individual predictors in the final model, which accounted for 17.3% of the variance in the HRQOL [Table 4].

Discussion

In this study, we administered a questionnaire on healthy lifestyles and the Turkish version of the Kid‑KINDL to examine the relationship between healthy lifestyles and HRQOL in early adolescents. At the beginning of our study, no validated Turkish version of the Adolescent Lifestyle Profile scale existed to assess the healthy lifestyle behaviors of adolescents; therefore, we prefer to use the self‑administered questionnaire on healthy lifestyles from previously published questionnaires. Health behavior items used in this study demonstrated satisfactory content validity and test‑retest reliability for Turkish adolescents. In the last decade, there has been a growing interest in assessing the HRQOL in Turkish adolescents. However, there are only three studies have evaluated the HRQOL and its determinants in school‑going adolescents.[21,22,29] Those studies examined

different and limited behavioral determinants. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first study to examine the influence of a wide range of socio‑economic and healthy Table 4: Hierarchical models of the factors associated with the HRQOL

Kid‑ KINDL

Socio‑demographic variables only Add to the healthy life style behaviors

Socio‑ demographic variables Gender (girls/boys) Socio‑economic status Class (years)

Mother’s educational level Father’s educational level Health promoting behaviors

Sleep duration

Fruit and vegetable intake

Three days a week doing physical activity Milk consumption frequency

Having breakfast Fast‑food consumption

Talking about their problems to close friends and family members

Leisure time social activity R2 Adjusted R‑square R‑square Change F change ‑0.081 ‑0.110* 0.117* 0.067 0.015 0.048 0.037 0.048 4.129** ‑0.050 ‑0.040 0.060 0.018 ‑0.012 0.092 0.040 ‑0.018 0.067 ‑0.010 ‑0.068 0.233*** 0.195*** 0.173 0.146 0.125 7.542*** Standardized beta coefficients are presented. *p<0.05; **p=0.01; ***p<0.001

lifestyle variables on the HRQOL in school‑going adolescents. When this study was implemented, there are few validated HRQOL instrument for use in Turkish adolescents. Among these measures, we chose the The Kid‑KINDL, because it requires little time to complete in school setting and offers more comprehensive information regarding overall HRQOL.[38]

We found Cronbach’s alpha values of 0.60 for whole scale which is lower than the acceptable level of 0.70. It should be noted that Istanbul Provincial Directorate for National Education did not permit the implication of family sub‑scale of Kid‑KINDL to be administered. This may be lead to slightly reduced Cronbach alpha values. The bivariate analyses showed that all of the sociodemographic factors were significantly associated with adolescent HRQOL. We found that girls had higher scores than boys in the subscales of self‑esteem and school. Previous studies yielded inconsistent results regarding gender differences in the HRQOL and its domains. Similar to our findings, Gaspar et al. (2009), reported that girls had higher scores than boys on the school subscale.[19] In contrast to our findings, Gaspar

et al. (2009) showed that girls scored significantly lower than boys on the self‑esteem subscale and Yayan and Altun (2013) reported that boys had higher scores on the school subscale.[19,21] Lima‑Serrano et al. (2018) showed

that boys had higher scores in most of the quality of life areas.[20] On the other hand, studies by Ravens‑Sieberer

et al. (2008) and Tavazar et al. (2014) did not find gender differences in these subscales.[24,29] These

inconsistent findings may be explained by differences in the study samples as well as the use different HRQOL instruments. We found significant differences in self‑esteem scores with regard to the education level of parents of Turkish adolescents. Consistent with this, a recent study conducted in Turkish adolescents suggested that parent’s educational background has a positive impact on their child’s self‑esteem.[49]

In agreement with previous studies, monthly income was found to be positively correlated with the total HRQOL scores and its subscale scores [emotional well being, self‑esteem, and friends).[19,22,24] Filho et al. (2018)

reported that economic status and family prosperity has a positive effect on quality of life.[23] Previous studies

showed that school grade was negatively correlated with the total HRQOL and its subscales of scores (physical well‑being, self‑esteem, and school),[19,22,24] which were

consistent with our results.

At the study time, all 6th, 7th, and 8th grades students

should join the National High School Entrance Exams (TEOG) to continue the education of high schools

according to the new education system in Turkey. The importance given to academic success increases with the high class level. It may lead to more stress, especially for 8th graders. They spent more time studying than

6th and 7th grade students, but not spending enough time

with their friends, hobbies and sports.[50]

The bivariate analyses showed that healthy lifestyle behaviors particularly dietary practices were associated with the HRQOL except for consumption of fruit and vegetable. Lower fast food consumption was associated with better HRQOL in school subscale. Positive correlations were found between the frequency of milk consumption and the subscale scores for self‑esteem, friends, and schools as well as between the frequency of eating breakfast and the subscale scores for self‑esteem and schools. In line with our results, a recent study in Turkey showed that adolescents who ate breakfast regularly had higher HRQOL scores.[21] Adolescents with

short sleep duration reported higher scores in the total HRQOL and its subscales of the physical well‑being and school. Similarly, previous studies reported that shorter sleep duration[15,17] and poor sleep quality[30,31] were

associated with worse HRQOL in junior high school students.

It is known that regular physical activity is an important component of a healthy lifestyle in adolescents. Recent studies showed that regular physical activity was associated with better HRQOL among adolescents.[15,17,21,26,28,30] Consistent with these

studies, we found that adolescents who reported they participated in physical activity three days a week had higher scores on the emotional well‑being subscale and the total HRQOL score than those who did not.[21] This

study showed that participation in leisure time social activities and talking about their problems were correlated positevely with the total score of the HRQOL and its four subscale scores: self‑esteem, school, friends, and emotional well‑being. These findings were consistent with previous studies that show leisure time social activities, social support satisfaction, family relation, school, and peers are associated with HRQOL in adolescent.[19,21,50] It is also important for adolescents

to feel accepted by their peers, the people they are in close contact with. Final hierarchical regression model including all study variables showed that only participation in social activities and talking about their problems were the strongest behavioural predictors of better HRQOL of Turkish school‑going adolescents. This finding corroborates the results from previous studies showing that having a supporting family and a good relationships between friends were very important for improving adolescents’ HRQOL.[26,51] These findings

are not surprising, because the TEOG has an important negative effects on the identification of the future educational lives and professions of the students through feelings such as stress, fear, anxiety and curiosity and affect their healthy lifestyle behaviors especially socializing.[50,52] As in other countries, schools in Turkey

are the most important setting to reach adolescents. However, school health services in our country are not broadly institutionalized because of existing laws and national policies. Employment opportunities for school nurses and counselors should be improved in Turkish educational institutions, because developing effective school‑based health and counseling services are most important to improve students’ academic performance, psychosocial wellbeing as well as healthy lifestyle.[50,53,54] Limitations

There are several limitations to this cross‑sectional study that should be considered when interpreting these findings. Our study was conducted in one public secondary school of Istanbul, limiting the generalizability of the results and conclusions. Therefore, future study using a nationally representative sample of public and private secondary school students is warranted to confirm our results. In addition, longitudinal studies are needed to determine potential changes in healthy lifestyles over time and the relationship between changes in lifestyles and HRQOL observed changes. In this study, data were collected via self‑report questionnaires, which may lead to social desirability bias. Thus, social desirability bias should be detected and controlled by using a social desirability scale in future studies. It should be noted that Istanbul Provincial Directorate for National Education did not permit the implication of family sub‑dimension of Kid‑KINDL to be administered. Therefore, we could not compare the mean HRQOL score with other studies using the Kid‑KINDL. We failed to account for other relevant factors, such as students’ psychosocial variables, school environment, family and parental characteristics in assessing the HRQOL. Future studies should assess these variables, which could provide a more comprehensive understanding of adolescent HRQOL.

Conclusion

In conclusion, our study suggests that healthy lifestyles behaviours, especially talking about their problems to close friends and/or family members and participation in leisure‑time social activity were related to better HRQOL among a sample of Turkish adolescents, independently of socio‑demographic factors. As a need assesment, this study may provide useful information regarding the factors influencing adolescent HRQOL for school health authorities when planning and developing

collaborative efforts among providers of school health and counseling services to improve their well‑being and HRQOL. Within these efforts, more emphasis should be given to promote students’ social skills that can help them to get more satisfaction from their life.

Financial support and sponsorship Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

References

1. Kuntsche E, Ravens‑Sieberer U. Monitoring adolescent health behaviours and social determinants cross‑nationally over more than a decade: Introducing the Health Behaviour in School‑aged Children [HBSC] study supplement on trends. Eur J Public Health 2015;25:1‑3.

2. İlhan N. Improving adolescent health. In: Efe R, Özcanarslan F, Shapekova NL, Sancar B, Özdemir A, editors. Recent Developments in Nursing and Midwifery. 1st ed. England:

Cambridge Scholars Publishing; 2018. p. 327‑43.

3. World Health Organization. Recognizing adolescence. [Cited 2017 July 12]. Available from: https://data.unicef.org/topic/ adolescents/adolescent‑demographics.

4. UNICEF. Adolescents overview. [Cited 2019 June 28]. Available from: https://data.unicef.org/topic/adolescents/overview/.

5. Turkish Statistical Institue. Population and Demography. [Cited 2017 July 12]. Available from: http://www.turkstat.gov.tr/ UstMenu.do?metod=temelist.

6. Schnohr CW, Molcho M, Rasmussen M, Samdal O, de Looze M, Levin K, et al. Trend analyses in the health behaviour in school‑aged children study: Methodological considerations and recommendations. Eur J Public Health 2015;2:7‑12.

7. UNFPA. UNFPA Strategy on Adolescents and Youth: Towards realizing the full potential of adolescents and youth. New York: UNFPA. 2013 [Cited 2015 December 12]. Available from: www.unfpa.org/webdav/site/global/ shared/youth/UNFPA%20, Adolescents%20and%20Youth%20 Strategy. pdf, accessed on.

8. Meade T, Dowswell E. Adolescents’ health‑related quality of life (HRQoL) changes over time: A three year longitudinal study. Health Qual Life Outcomes 2016;25:14.

9. WHO. Adolescents: Health risks and solutions. [Cited 2017 July 19]. Available from: http://www.who.int/mediacentre/factsheets/ fs345/en/.

10. Givens SR. Child and adolescent health. In: Nies MA, Mc Ewen M, editors. Community/Public Health Nursing Promoting the Health of Populations. 6th ed. Canada: Elsevier; 2015.

p. 286‑313.

11. WHO. Situation of child and adolescent health in Europe. [Cited 2017 July 19]. Available from: file:///P:/Users/nilhan/Downloads/ situation‑child‑adolescent‑health‑eng.pdf.

12. Dick B, Ferguson BJ. Health for the world’s adolescents: A second chance in the second decade. J Adolesc Health 2015;56:3‑6.

13. Freire T, Ferreira G. Health‑related quality of life of adolescents: Relations with positive and negative psychological dimensions. Int J Adolesc Youth 2018;23:11‑24.

14. Honkola S. World Health Organization approaches for surveys of health behaviour among school children and for health‑promoting schools. Med Princ Pract 2014;23(Suppl 1) 24‑31.

15. Chen X, Sekine M, Hamanishi S, Wang H, Gaina A, Yamagami T, et al. Lifestyles and health‑related quality of life in Japanese school children: A cross‑sectional study. Prev Med 2005;40:668‑78.

16. Chen G, Ratcliffe J, Olds T, Magarey A, Jones M, Leslie E. BMI, health behaviors, and quality of life in children and adolescents: A school‑based study. Pediatrics 2014;133:868‑74.

17. Xu F, Chen G, Stevens K, Zhou H, Qi S, Wang Z, et al. Measuring and valuing health‑related quality of life among children and adolescents in mainland China‑‑A pilot study. PLoS One 2014;9:89222.

18. Pappa E, Chatzikonstantinidou S, Chalkiopoulos G, Papadopoulos A, Niakas D. Health‑related quality of life of the Roma in Greece: The role of socio‑economic characteristics and housing conditions. Int J Environ Res Public Health 2015;12:6669‑81.

19. Gaspar T, Matos MG, Ribeiro J, Leal I, Ferreira A. Health‑related quality of life in children and adolescents and associated factors. J Cogn Behav Psychother 2009;9:33‑48.

20. Lima‑Serrano M, Martínez‑Montilla JM, Guerra‑Martín MD, Vargas‑Martínez AM, Lima‑Rodríguez JS. Quality‑of‑life‑related factors in adolescents. Gac Sanit 2018;32:68‑71.

21. Yayan EH, Altun E. Investigating some sociodemographic features effecting quality of life of teenagers who study in 6,7,8 classes of primary schools in city centre of Malatya. Cumhuriyet Nurs J 2013;2:42‑9.

22. Altıparmak S, Taner Ş, Türk Soyer M, Eser E. The quality of life in adolescent in secondary public schools in Bornova/İzmir. Anatolian J Psychiatry 2012;13:167‑73.

23. Filho VCB, Oppa DF, Mota, J, Mendes de Sá SA, Lopes da S. Predictors of health‑related quality of life among Brazilian former athletes. Rev Andal Med Deport 2018;11:23‑9.

24. Ravens‑Sieberer U, Erhart M, Wille N, Bullinger M, BELLA study group. Health‑related quality of life in children and adolescents in Germany: Results of the BELLA study. Eur Child Adolesc Psychiatry 2008;17:148‑56.

25. Frisen A. Measuring health‑related quality of life in adolescence. Acta Paediatr 2007;96:963‑8.

26. Muros JJ, Salvador Pérez F, Zurita Ortega F, Gámez Sánchez VM, Knox E. The association between healthy lifestyle behaviors and health‑related quality of life among adolescents. J Pediatr (Rio J) 2017;93:406‑12.

27. Wafa SW, Shahril MR, Ahmad AB, Zainuddin LR, Ismail KF, Aung MM, et al. Association between physical activity and health‑related quality of life in children: A cross‑sectional study. Health Qual Life Outcome 2016;14:71.

28. Gopinath B, Hardy LL, Baur LA, Burlutsky G, Mitchell P. Physical activity and sedentary behaviors and health‑related quality of life in adolescents. Pediatrics 2012;130:167‑74. 29. Tavazar H, Erkaya E, Yavaş Ö, Zerengök D, Güzel P, Özbey

S. The research of the differences between physical activity and life quality in senior high school students (Manisa City example). International Journal of Science Culture and Sport 2014;5:496‑510.

30. İyigün G, Angın E, Kırmızıgil B, Öksüz S, Özdil A, Malkoç M. The relationship between sleep quality with mental health, physical health and, quality of life in university students. J Exerc Ther Rehabil 2017;4:125‑33.

31. LeBlanc M, Beaulieu‑Bonneau S, Mérette C, Savard J, Ivers H, Morin CM. Psychological and health‑related quality of life factors associated with insomnia in a population‑based sample. J Psychosom Res 2007;63:157‑66.

32. Ortabag T, Ozdemir S, Bakir B, Tosun N. Health promotion

and risk behaviors among adolescents in Turkey. J Sch Nurs 2011;27:304‑15.

33. Özcan C, Kılınç S, Gülmez H. School health and legal status in Turkey. Ankara Med J 2013;3:71‑81.

34. Dağdeviren Z, Şimşek Z. Health promotion behaviors and related factors of high school students in Şanlıurfa. TAF Prev Med Bull 2013;12:135‑142.

35. Ardic A, Esin MN. Factors associated with healthy lifestyle behaviors in a sample of turkish adolescents: A school‑based study. J Transcult Nurs 2015;27:583‑92.

36. Soper DS. A‑priori Sample Size Calculator for Multiple Regression [Software]. [Cited 2017 July 19]. Available from: http://www.danielsoper.com/statcalc.

37. Republic of Turkey Ministry of Family and Social Policies. Research on Family Structure in Turkey. Ankara, Turkey: Avşar Publishing; 2011.

38. Eser E, Yüksel H, Baydur H, Erhart M, Saatli G, Ozyurt BC, et al. The psychometric properties of the new Turkish generic health‑related quality of life questionnaire for children (Kid‑KINDL). Turk J Psychiatry 2008;19:409‑17. 39. CDC. Physical Activity Guidelines for Americans: Active

Children and Adolescents. [Cited 2017 July 19]. Available from: http://health.gov/paguidelines/guidelines/chapter 3.aspx. [Last accessed on 2019 Sep 03.].

40. Garaulet M, Ortega FB, Ruiz JR. Short sleep duration is associated with increased obesity markers in European adolescents: Effect of physical activity and dietary habits. The HELENA study. Int J Obes 2011;35:1308‑17.

41. Agudo A. Measuring intake of fruit and vegetables. WHO Electronic publication. [Cited 2012 July 22].

Available from: https://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/

handle/10665/43144/9241592826_eng.pdf?sequence=1 and

isAllowed=y.

42. Cuypers K, De Ridder K, Kvaloy K, Knudtsen MS, Krokstad S, Holmen J, et al. Leisure time activities in adolescence in the presence of susceptibility genes for obesity: Risk or resilience against overweight in adulthood? The HUNT study. BMC Public Health 2012;12:820.

43. Payab M, Kelishadi R, Qorbani M, Motlagh ME, Ranjbar SH, Ardalan G, et al. Association of junk food consumption with high blood pressure and obesity in Iranian children and adolescents: The CASPIAN‑IV Study. J Pediatr (Rio J) 2015;91:196‑205. 44. Hendricks C, Murdaugh C, Pender N. The adolescent lifestyle

profile: Development and psychometric characteristics. J Natl Black Nurses Assoc 2006;17:1‑5.

45. Polit D, Beck C. The content validity index: Are you sure you know what’s being reported? critique and recommendations. Res Nurs Health 2006; 29:489‑97.

46. Walter SD, Eliasziw M, Donner A. Sample size and optimal designs for reliability studies. Stat Med 1998;17:101‑10.

47. Evans JD. Straightforward Statistics for the Behavioral Sciences. 1st ed. Pacific Grove: CA. Brooks/Cole Publishing

Company; 1996.

48. Landis JR, Koch GG. The measurement of observer agreement for categorical data. Biometrics 1977;33:159‑74.

49. Şahin E, Barut Y, Ersanlı E. Parental education level positively affects self‑esteem of turkish adolescents. J Educ Pract 2013;4:87‑97.

50. Baltacı HŞ. Turkish 6 th ‑8th grade students’ social emotional

learning skills and life satisfaction. International Journal on New Trends in Education and Their Implications 2013;4:1‑14. 51. Boylu AA, Paçacıoğlu B. Quality of life and indicators. Journal

52. Argon T, Soysal A. Teacher and student views regarding the placement test. Journal of Human Sciences 2012;9:446‑74. 53. Baysal SU, İnce T. Recent developments in school‑based health

services in Turkey. J Pediatr Res 2018;5:60‑4.

54. WHO. Creating an environment for emotional and social well‑being: An important responsibility of a health‑promoting and child friendly school. 2003. [Cited 2016 July 12]. Available from: http://www. who.int/school_youth_health/media/en/sch_childfriendly_03.pdf.