BARIATRIC SURGICAL PRACTICE AND PATIENT CARE Volume 14, Number 2, 2019

ª Mary Ann Liebert, Inc. DOI: 10.1089/bari.2018.0053

Bridged Mini Gastric Bypass:

A Novel Metabolic and Bariatric Operation

Aziz Su¨ mer, MD,1 Deniz Atasoy, MD,1 Umut Barbaros, MD,2 Osman Anıl Savasx, MD,1 Eryig˘it Eren,

MD,1 Isxıl Yurdaısxık, MD,3 Hasan Huseyin Eker, MD, PhD,4 and Selc¸ uk Mercan, MD2

Introduction: In this article, we aimed to report the first five cases of laparoscopic bridged mini gastric bypass

(BMGB) in the treatment of obesity and type II diabetes mellitus (DM).

Presentation of Cases: We have performed five cases with a new modified surgical method that we call a

BMGB. The patients’ recoveries were uneventful. The weight losses of the patients were 15, 13, 14, 11, and 13

kg subsequently and with complete normalization of all metabolic parameters at first month of follow-up.

Discussion: The BMGB was modified from the mini gastric bypass and resulted with the same nutritional

results, less surgical complications, and a possible advantage of remaining access to the remnant stomach.

Conclusion: BMGB may be as effective and possibly an even easier operation to treat obesity and uncontrolled

type II DM with possible advantages over currently available metabolic procedures.

Keywords: bridged mini gastric bypass, obesity, type II diabetes, BMGB

Introduction

O

besity is a worldwide epidemic currently affecting both developed and developing countries. After smok-ing, obesity is the second leading cause of preventable deathsin the world. According to the World Health Organization (WHO), 1.7 billion adults, 20 years and older, were over-weight or obese in 2008. Two hundred million men and nearly 300 million women were obese.1,2

Controlling type II diabetes mellitus (DM) currently is associated with intensive medical therapy. The positive effect of Metabolic Surgery on type II DM is getting more obvious over time.3 So far, two Diabetes Surgery Summits have been held and the first of them took place in 2007 in Rome and the last one in 2015 in London. The American Diabetes Asso-ciation, International Diabetes Federation, Chinese Diabetes Society, Diabetes India, European Association for the Study of Diabetes, and Diabetes UK joined to the Second Diabetes Surgery Summit (DSS-II). The guideline that resulted from this meeting determined the current indications for metabolic surgery. According to this summit, metabolic surgery should be recommended for the treatment of type II DM in selected cases with class III obesity (body mass index [BMI] ‡40 kg/m2), regardless of the level of glycemic control or complexity of glucose-lowering regimens, as well as in patients with class II obesity (BMI 35.0–39.9 kg/m2) with inadequately controlled hyperglycemia, despite lifestyle and optimal medical ther-

apy. Metabolic surgery indications were extended to the treatment of type II DM in patients with class I obesity

(BMI 30.0–34.9 kg/m2) and inadequately controlled

hyperglycemia despite optimal medical treatment by either oral or injectable medications (including insulin).4

For metabolic surgery, lots of techniques were defined from basic interventions such as adjustable gastric banding to more complex procedures such as ileal interposition. All current metabolic procedures, such as Roux-en-Y gastric bypass, du-odenal switch/biliopancreatic diversion, single anastomosis duodeno-ileal bypass (SADI), transit bipartition/its modifica- tion, and ileal interposition, are based on either the foregut or the hindgut theory or the combination of both.1,3–7

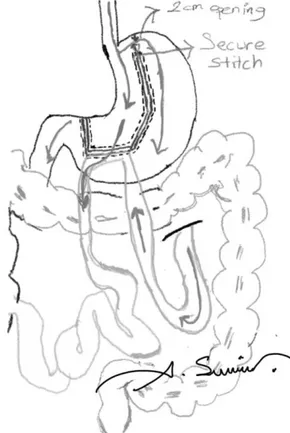

Rutledge first described mini gastric bypass (MGB) to treat obesity and related type II DM.5 We modified the previously described technique by leaving a bridge (such as artificial gastro-gastric fistula [GGF]) at the most cranial 2 cm of fun-dus. We would like to call this modified new technique bridged MGB (BMGB, Sumer’s techinque). In this article, we aimed to explain our technique in detail and discuss its potential ad-vantages and disadvantages in the light of the literature.

Materials and Methods

We have performed five cases with the modified method at the Bariatric and Metabolic Surgery Unit of Istinye Uni-versity Medical Park Gaziosmapasxa Hospital in 2018. Patient

1

Department of General Surgery, Faculty of Medicine, Istinye University, Istanbul, Turkey.

2

Department of General Surgery, Faculty of Medicine, Istanbul University, Istanbul, Turkey.

3

Department of Radiology, Faculty of Medicine, Istinye University, Istanbul, Turkey. 4

Department of Surgery, MCL, Leeuwarden, The Netherlands. 62

Table 1. Patient Demographics, Operative, and Postoperative Data

Age/ Height (cm)/ BMI EWL HbA1c FU OT EBL LOS

Case sex weight (kg) (kg/m2) (%) (%) C-P CM Ins PS (week) (min) (mL) (day)

1 51/F 155/124 51.6 19.9. 7.8 3.68 DM2 + AGB 6 170 50 3 - TT 2 26/F 159/95 37.6 29.1 — — GERD LNF 5 150 50 3 3 62/F 162/112 42.7 23.5 8.2 3.2 DM2 HT, + — 5 90 30 3 CRF + 4 53/F 161/93 35.9 26.8 10.2 5.1 DM2 HT — 4 120 30 3 5 56/F 158/102 40.9 25 5.2 3.45 DM2 HT + — 4 65 20 3

EWL = (Initial Weight - Current Weight)/(Initial Weight - Ideal Weight) · 100.

AGB, adjustable gastric banding; BMI, body mass index; CRF, chronic renal failure; CM, comorbidity; C-P, C-peptide; EBL, estimated blood loss; EWL, excess weight loss; FU, follow-up; GERD, gastroesophageal reflux disease; HT, hypertension; Ins, insulin; LNF, laparoscopic Nissen fundoplication; LOS, length of hospital stay; OT, operating time; PS, previous surgery; TT, Tumy Tuck; TIIDM, type II diabetes mellitus.

demographics and operative and postoperative variables are presented in Table 1.

The case presentations are below. Case 1

A 51-year-old female BMI: 51.6 kg/m2; with a 10-year history of obesity and type II DM underwent the procedure at Istinye University Medical Faculty hospital. In her medical history, there were laparoscopic adjustable gastric banding and abdominoplasty operations 4 and 3 years ago subse-quently. The control of her DM was poor, and she failed to lose weight. We performed laparoscopic removal of the gastric banding. After removal of the gastric banding we decided to perform a standard MGB as was defined by Ru-tledge. However, because of the dense and thick fibrotic tissue at the upper part of the fundus, we could not trust the green cartridge stapler, and we were forced to leave the up-permost 2 cm of the stomach uncut (Fig. 1). The patient’s recovery, was uneventful. Her metabolic parameters were completely normalized with cessation of all medications and loss of 15 kg at the first month. Case 2

A 26-year-old female who has BMI: 37.6 kg/m2 with a 5-year history of obesity and gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD). In the medical history, laparoscopic Nissen fun-doplication was performed 3 years earlier. She was admitted to our department for revision of the failed Nissen fundo-plication and bariatric surgery. After revision of the failed Nissen fundoplication, we attempted MGB operation. Be-cause of the dense and thick fibrotic tissue at the upper part of the fundus, we again had to leave the upper 2 cm of the stomach uncut. The patient’s recovery was uneventful. She lost 13 kg during the first month. Case 3

A 62-year-old female BMI: 42.7 kg/m2; with an 18-year history of obesity, type II DM, hypertension and chronic renal failure (creatinine level 2 mg/dL). After the success of the first two cases with BMGB, we decided to perform the same modified operation for this patient also. BMGB was per-formed after her inper-formed consent about the operation in detail. The patient’s recovery was uneventful. Her metabolic

parameters were completely normalized with cessation of all medications and insulin except her antihypertensive drug. She lost 14 kg at the end of the first month.

Case 4

A 53-year-old female BMI: 35.9 kg/m2; with a 19-year history of type II DM and hypertension. BMGB was per-formed. The patient’s recovery was uneventful. Her metabolic parameters were completely normalized with cessation of all medications and insulin and lost 11 kg during the first month. Case 5

A 56-year-old female BMI: 40.9 kg/m2; with an 8-year history of type II DM and hypertension. BMGB was

FIG. 1. Scheme of BMGM (NOTE: drawn by A. Sumer, one of the authors). BMGM, bridged mini gastric bypass.

64 SUMER ET AL. ¨

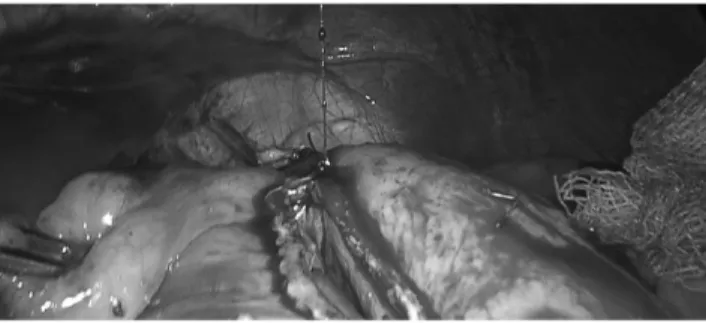

FIG. 2. Creation of an opening in the hepatogastric liga-ment at the level of incisura angularis.

performed. The patient’s recovery was uneventful. Her metabolic parameters were completely normalized with cessation of all medications and lost 13 kg at first month. Surgical Technique

The patient was positioned in a steep reverse Trendelen-burg position with legs separated and both arms extended. The surgeon stood between patient’s legs. A urethral catheter and a nasogastric tube were introduced to all patients. For the procedure, one 10 mm, two 12 mm, one 15 mm, and one 5 mm trocars were utilized. Pneumoperitoneum was estab-lished with Hasson’s open technique through a supra-umbilical incision. The 10 mm trocar was introduced through this incision and was used for laparoscopic camera. The other two 12 mm trocars were introduced from the subxiphoidal and left midclavicular lines, consecutively. The 15 mm trocar was inserted from the right midclavicular line. The 5 mm trocar was inserted from the left anterior axillary line. The subxiphoidal 12 mm trocar was used for gastric transection and later placement of the Nathanson Hookª liver retractor (Cook Ireland Ltd., Limerick, Ireland).

The procedure started with the creation of an opening in the hepatogastric ligament at the level of incisura angularis with a vessel sealing device (Ligasure ; Valleylab, Boulder, CO). A small hole, adequate for stapler entrance was created (Fig. 2). Then, the first linear stapler (Endo-GIA , Covidien Endo GIA Ultra Universal staplers with Covidien Endo GIA Reloads with Tri-Staple Technology, Mansfield) (45 mm

FIG. 4. After firing of the first stapler.

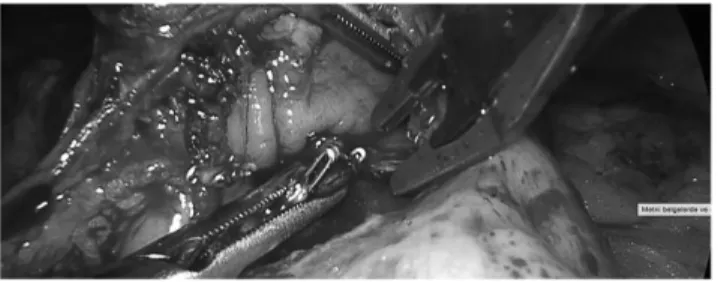

purple) was introduced through the subxiphoidal port and placed parallel and 3–4 cm away from the pylorus, at the level of incisura angularis (Figs. 3 and 4). After the first firing, an orogastric tube (39F-bougie) was introduced by the anes-thesiologist and later/following fires were placed according to the orogastric tube. After the first fire, the stapling was directed cranially. However, not just parallel to the orogastric tube, but a little bit away from the tube, thus creating a bigger pouch compared to the standard MGB. For the remaining stapling, blue, green, or purple cartridges were used depending on the appearance/thickness of the stomach (Figs. 5 and 6).

Before the last firing, approximately a 2 cm-long passage was left in the uppermost stomach. This passage could be measured by two methods. First, the 39F-bougie could be passed toward the fundus and the last cartridge is fired against the bougie. Second, the diameter of the remaining stomach bridge could be measured with the jaws of a laparoscopic instrument (Fig. 7). After the last fire, a stitch is placed at the corner, including the distal end of the uppermost stapler to reinforce the corner (Fig. 8).

Following completion of the gastric transection, the pro-cedure continues with the intestinal phase. The patient was brought to a Trendelenburg position. The transverse colon and omentum were retracted cranially. Following identifi-cation of the Treitz’s ligament, a small bowel segment be-tween 150 and 250 cm from the Treitz’s ligament, depending on the patients’s BMI, was measured. The measured loop of the small bowel was brought cranially close to the pouch. Finally, the patient was again brought to a steep reverse Trendelenburg position and with the aid of the monopolar bound hook cautery holes for the entrance of the jaws of the

FIG. 6. Depending of thickness of gastric wall placement of staplers.

stapler were created on the stomach and small bowel. Next, a blue load of 60 mm linear stapler was used for the creation of gastrojejunostomy anastomosis (Fig. 9). Following gas-trojejunostomy stapling, the staple line was observed for bleeding and if present, bleeding points were clipped or su-ture ligated (Fig. 10). The stapler entrance sites were closed with 3–0 V-Loc (Covidien, Mansfield) suture in a single layer manner (Fig. 11).

A methylene blue test was performed to evaluate any narrowing or staple line leaks. A drain was placed under the anastomosis.

Postoperative management

At the first postoperative day, patients underwent an upper gastrointestinal (GI) contrast-enhanced study to check for leakage and preferential passage of contrast through the gastrojejunostomy. After contrast-enhanced study, a clear liquid diet was started and the drain was removed. Patients were discharged with the dietician’s recommendations at day 3 postoperatively.

Discussion

The following is the main question to be answered: How right is it to irreversibly change or remove a large piece of a completely normal organ to treat other diseases?

As Buchwald said ‘‘To know what is new, one must know what is old.’’ From this perspective, reviewing obesity his-tory is a crucial step to understand the current surgical

FIG. 8. Securing corner with reinforcement stitch.

techniques. Bariatric surgery is a dynamic surgical field and changes have continued in recent years.1,7 Several GI opera-tions, including partial gastrectomies and bariatric procedures, promote dramatic, durable improvement of type II DM.4

The most commonly used bariatric and metabolic surgical techniques are adjustable gastric banding, sleeve gastrectomy (SG), and Roux-en-Y gastric bypass.7,8 Recently, especially in metabolic surgery, modifications of the first applied sur-gical techniques, such as SADI, transit bipartition, and modified transit bipartition have been attempted.3,9,10 One anastomosis gastric bypass, or as called earlier MGB, is a method that has been used for about 20 years. The MBG method was described by Robert Rutledge.5 At first, it was applied to trauma patients. After its metabolic benefits were detected, it became a method used in obesity treatment and metabolic surgery. This method, which was seriously criti-cized in the beginning, finally got accepted as a bariatric method by IFSO and presented as the recommended method (R. Rutledge, personal communication, June 22, 2018).11 Increasingly, evidence reveals that the risk of long-term

complications of MGB is less and that the metabolic effects are better than Roux-en-Y gastric bypass.12,13

A meta-analysis published by Wang et al. showed that MGB has multiple advantages over Roux-en-Y gastric by-pass.13 These advantages are a higher 1-year excess weight loss (EWL), higher 2-year EWL, higher type II DM remission rate, and a shorter operation time. In terms of long-term re- sults, such as %EWL and type II DM remission, MGB might be superior to laparoscopic SG also.12,13

In the area of metabolic surgery, GGF is an underestimated complication after Roux-en-Y gastric bypass, since some patients have asymptomatic fistulas or are lost to follow-up. The estimated incidence of GGF is 1% to 6%. GGF may be asymptomatic or presents with nonspecific symptoms, such

FIG. 7. Measuring of the stomach bridge with jaw of

66 SUMER ET AL. ¨

FIG. 10. Check for hemostasis and placement of clips when necessary.

as nausea, vomiting, and abdominal pain. Sometimes GGF causes more specific symptoms such as hemorrhage, perfo- ration, or stricture. Most of the patients who have GGF do not need surgical treatment.14,15 There is no data on GGF fol- lowing MGB in the Medline Database yet. In a personal discussion with Dr. Robert Rutledge in 2018, in Tu¨rkiye, during the MGB Bronze certificate course, he remembered *10 patients who had GGF in his personal experience of 7000 MGB patients, and none of them regained weight or recurred diabetes (R. Rutledge, personal communication, June 22, 2018). Rutledge’s personal experience might indicate that GGF in patient with MGB is less important as it was thought in terms of weight regain and recurrence of diabetes. From this perspective, as a MGB is essentially a malabsorptive proce-dure, GGF may not affect the malabsorption.

Postoperative upper GI bleeding is rare but dangerous, and in some patients may be a fatal complication after Roux-en-Y gastric bypass. In these cases, there is no endoscopic way to reach the remnant stomach in case of upper GI bleeding and laparoscopic endoscopy is mandatory in the operating the-atre, under general anesthesia.16,17 The same risk is present for MGB. In the modified technique that we described, the remnant stomach can be reached through the artificial GGF.

Also endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography

(ERCP) procedures could easily be performed.

MGB in comparison to Roux-en-Y gastric bypass and other metabolic methods has many advantages such as reversibility, being an easy and simple method. The most criticized side of the MGB, as well as Roux-en-Y gastric bypass, is the loss of the endoscopic pathway into the remnant stomach. In our technique, this single disadvantage is being eliminated.

In the BMGB, there is the possibility of performing en-doscopy through the 2 cm noninterrupted area that is on the

FIG. 11. Closure of stapler defect with barbed suture.

top of the fundus. The reason of leaving a 2 cm diameter gastro-gastric opening in BMGB is to allow endoscopic procedures and ERCP. Since the outer diameter of the distal part of the duodenoscope is 13.7 mm, the opening is cali-brated to 2 cm, to perform ERCP easily.18

The other advantages of BMGB method are shown below as eight ‘‘N’’s;

(1) Never touch and destroy the Angle of His

(2) Not removing 75–80% of the stomach as in SG and protection of the organ.

(3) No short gastric vessel bleeding during dissection of the fundus during the last stapler as it is performed in the MGB.

(4) No leak. Since there is an opening between the newly formed pouch and the gastric remnant, the risk of leakage from the pouch is theoretically lower. (5) No chance for endoscopic intervention in MGB and

Roux-en-Y gastric bypass in cases of remnant gastric bleeding.16,17 Since remnant stomach can be evalu-ated endoscopically, remnant gastric bleeding can be controlled more easily during surgery or in the post-operative period. Furthermore, endoscopic surveil-lance of the remnant stomach, in cases of gastric cancer suspicion, could be performed.

(6) No narrow pouch like in the MGB.

(7) No complications in revisional surgery after adjustable gastric banding. Because the fundus is fibrotic and thick after gastric banding, the risk of leakage increases in the operations that transect the fundus such as in

SG, MGB, and Roux-en-Y gastric bypass.19

(8) Not using one extra cartridge for the last few centimeters may provide a significant benefit in terms of cost.

Considering these advantages, regarding all modified tech-niques described so far, we can hypothesize that BMGB might be the most physiological and anatomical technique. In the long term, if the weight loss and metabolic effects can be achieved, it might be adapted more widely to patients of all ages.

The limitations of this study are its retrospective design and a small sample size. In addition, we did not have a chance to test the bridge for an endoscopy or ERCP postoperatively in these patients. The long-term results of the gastric bridge are not clear. Scarring on the long term may lead to stenosis and may hedge endoscopic intervention or surveillance. Further calibration of the ‘‘bridge’’ could be needed. On the contrary, stretching of the ‘‘bridge’’ may lose the bariatric and metabolic effects of the operation.

The idea behind this study was to find a solution for the remnant stomach without losing the metabolic and bariatric effects of the original MGB procedure. In addition, in case of scarred gastric wall in the fundus of the stomach, this approach avoids risky stapling in this area. More research has to be done to provide information on the long-term effects of this modified technique.

Conclusions

In addition to the advantages of MGB, BMGB method eliminates the single disadvantage of losing endoscopic ac-cess to the remnant stomach. Current results are encouraging, but further clinical studies are needed to evaluate the long-term results.

Author Disclosure Statement

No competing financial interests exist.

References

1. Sumer A. Definition of obesity and current indications for obesity surgery. Laparosc Endosc Surg Sci 2016;23: 56– 62.

2. Dixon JB, le Roux CW, Rubino F, Zimmet P. Bariatric surgery for type 2 diabetes. Lancet 2012;379:2300–2311. 3. Mui WL, Lee DW, Lam KK. Laparoscopic sleeve

gas-trectomy with loop bipartition: a novel metabolic operation in treating obese type II diabetes mellitus. Int J Surg Case Rep 2014;5:56–58.

4. Rubino F, Nathan DM, Eckel RH, Schauer PR, Alberti KG, Zimmet PZ, et al.; Delegates of the 2nd Diabetes Surgery Summit. Metabolic surgery in the treatment algorithm for type 2 diabetes: a Joint Statement by International, Dia-betes Organizations. Obes Surg 2017;27:2–21.

5. Rutledge R. The mini-gastric bypass: experience with the first 1274 cases. Obes Surg 2001;11:276–280.

6. Kheniser KG, Kashyap SR. Diabetes management before, during, and after bariatric and metabolic surgery. J Diabetes Complications 2018;32:870–875.

7. Buchwald H. Overview of bariatric surgery. J Am Coll Surg 2002;194:367–375.

8. Abraham A, Ikramuddin S, Jahansouz C, Arafat F, Heve-lone N, Leslie D. Trends in bariatric surgery: procedure selection, revisional surgeries, and readmissions. Obes Surg 2016;26:1371–1377.

9. Santoro S, Castro LC, Velhote MC, Malzoni CE, Klajner S, Castro LP, et al. Sleeve gastrectomy with trasit bipartition: a potent intervention for metabolic syndrome and obesity. Ann Surg 2012;256:104–110.

´ ´

10. Sanchez-Pernaute A, Rubio MA, Cabrerizo L, Ramos-Levi A, Pe´rez-Aguirre E, Torres A. Single-anastomosis duodenoileal bypass with sleeve gastrectmy (SADI-S) for

obese diabetic patients. Surg Obes Relat Dis

2015;11:1092– 1098.

11. Bariatric Surgery. https://ifso.com/bariatric-surgery/ Accessed March 29, 2019.

12. Abdel-Rahim MM, Magdy MM, Mohamad AA. Com-parative study between effect of sleeve gastrectomy and mini-gastric bypass on type 2 diabetes mellitus. Diabetes Metab Syndr 2018;12:949–954.

13. Wang FG, Yan WM, Yan M, Song MM. Outcomes of Mini vs Roux-en-Y gastric bypass: a meta-analysis and T sys-tematic review. Int J Surg 2018;56:7–14.

14. Chahine E, Kassir R, Dirani M, Joumaa S, Debs T, Chouillard E. Surgical management of gastrogastric

fistula after Roux-en-Y gastric bypass: 10-year

experience. Obes Surg 2018;28:939–944.

15. D’Hondt M, Vansteenkiste F, Van Rooy F, Devriendt D. Gastrogastric fistula after gastric bypass—is surgery always needed? Obes Surg 2006;16:1548–1551.

16. Rabl C, Peeva S, Prado K, James AW, Rogers SJ, Posselt A, et al. Early and late abdominal bleeding after roux-en-Y gastric bypass: sources and tailored therapeutic strategies. Obes Surg 2011;21:413–420.

17. Issa H, Al-Saif O, Al-Momen S, Bseiso B, Al-Salem A. Bleeding duodenal ulcer after Roux-en-Y gastric bypass surgery: the value of laparoscopic gastroduodenoscopy. Ann Saudi Med 2010;30:67–69.

18. Olympus. www.olympus-europa.com/medical/ Accessed March 9, 2019.

19. Tran TT, Pauli E, Lyn-Sue JR, Haluck R, Rogers AM. Revisional weight loss surgery after failed laparoscopic gastric banding: an institutional experience. Surg Endosc 2013;27: 4087–4093.

Address correspondence to: Aziz Sumer, MD Department of General Surgery Faculty of Medicine Istinye University Istanbul 34250 Turkey E-mail: drazizsumer@gmail.com