T.C.

GAZİ UNIVERSITY

THE INSTITUTE OF EDUCATIONAL SCIENCES

FOREIGN LANGUAGE TEACHING DEPARTMENT

ENGLISH LANGUAGE TEACHING PROGRAMME

DISTANCE FOREIGN LANGUAGE LEARNERS’ LEARNING

BELIEFS

AND READINESS FOR AUTONOMOUS LEARNING

MASTER THESIS

By

Lutfiye GÖÇMEZ

Ankara

ŞUBAT, 2014

T.C.

GAZİ UNIVERSITY

THE INSTITUTE OF EDUCATIONAL SCIENCES

FOREIGN LANGUAGE TEACHING DEPARTMENT

ENGLISH LANGUAGE TEACHING PROGRAMME

DISTANCE FOREIGN LANGUAGE LEARNERS’ LEARNING

BELIEFS

AND READINESS FOR AUTONOMOUS LEARNING

MASTER THESIS

By

Lutfiye GÖÇMEZ

Advisor: Gonca YANGIN EKŞİ

Ankara

ŞUBAT, 2014

ii

JÜRİ ONAY SAYFASI

Lutfiye GÖÇMEZ’in “DISTANCE FOREIGN LANGUAGE LEARNERS’ LEARNING BELIEFS AND READINESS FOR AUTONOMOUS LEARNING” başlıklı tezi 14/02/2014 tarihinde, jürimiz tarafından Yabancı diller Anabilim Dalı’nda Yüksek Lisans Tezi olarak kabul edilmiştir.

Adı-Soyadı İmza

Başkan: Doç. Dr. Paşa Tevfik CEPHE ...

Üye (Tez Danışmanı): Doç. Dr. Gonca YANGIN EKŞİ ...

iii

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

I would like to thank Assoc. Prof Dr. Gonca YANGIN EKŞİ, my supervisor in this study, for her guidance, valuable advice, and continual support during the course of this research. Her kind words provided me with the motivation to push on throughout the study. Her approach to teaching and research has been the best example I could ever have.

I would like to express my deep gratitude to the administrative and academic staff of Gazi University Distance Education Vocational School, and Research Assistant Esra HARMANDAOĞLU for their endless support and contributions to this study.

I will also be grateful to Prof. Dr. Elaine Horwitz and Assoc. Prof. Dr. Sara Cotterall for their permission to use their questionnaires in my study and their generous guidance during my research.

I would like to extend my gratitude to my dear husband Ensar GÖÇMEZ and my dear brother Utku CİVAN for their unceasing patience and constant understanding through these years of my Master’s program.

Last, but not least, I would like to thank all the distance language learners of Gazi University Distance Education Vocational School who took the time to participate in this study. Without them, this study would never have been possible.

Lutfiye GÖÇMEZ ANKARA 2014

iv ÖZET

UZAKTAN EĞİTİM ÖĞRENCİLERİNİN YABANCI DİL ÖĞRENME İNANÇLARI VE OTONOM ÖĞRENMEYE HAZIRBULUNUŞLUKLARI

GÖÇMEZ, Lutfiye Yüksek Lisans Tezi İngilizce Öğretmenliği Bölümü Danışman: Doç. Dr. Gonca YANGIN EKŞİ

Şubat-2014, 91 Sayfa

Uzaktan eğitim, Türkiye’de müfredat, dil öğretimi ve materyal açısından geliştirilmesi gereken yeni bir öğretim alanıdır. Ancak, Türkiye’de uzaktan eğitim alanında çok az araştırma yapılmıştır. İşte bu nedenle, bu tezin amacı uzaktan eğitim öğrencilerinin yabancı dil öğrenme inançlarını ve daha özel olarak, otonom öğrenmeye hazır olup olmadıklarını sistematik bir şekilde araştırmaktır. Ayrıca, uzaktan eğitim öğrencilerinin yabancı dil öğrenme inançları ve otonom öğrenmeye hazır olup olmadıklarıyla ilgili araştırma sorularını cinsiyet, yaş, en son mezuniyet durumları ve çalışma durumları değişkenlerine göre cevaplandırmaya çalıştık. Bu çalışmada, Cotterall ‘in (1995) öğrenme inançları ve otonomi ile ilgili anketi ve Horwitz’in (1988) BALLI ölçeği kullanılarak elde edilen verilerin analizinde nicel araştırma yöntemi kullanılmıştır. Araştırmanın örneklemini, Gazi Üniversitesi Uzaktan Eğitim Meslek Yüksekokulu’nun 2012-2013 öğretim yılının Güz döneminde Yabancı Dil - I dersini alan 947 öğrencisi oluşturmaktadır. Sonrasında, elde edilen veriler SPSS programı aracılığıyla analiz edilerek araştırmacı tarafından yorumlanmıştır. Sonuç olarak, her ne kadar bulgularda öğrencilerin cinsiyeti, yaşı, en son mezuniyet durumu ve çalışma durumları gibi değişkenlere göre farklılık olsa da, Türk uzaktan eğitim öğrencilerinin yabancı dil öğrenmeyle ilgili olumlu inançlara ve yabancı dil öğrenmek için oldukça fazla dış motivasyona sahip oldukları ve otonom öğrenmeye neredeyse hazır oldukları gözlenmiştir.

Anahtar Kelimeler: Uzaktan Eğitim, Otonomi, Yabancı Dil Öğrenme İnançları,

v ABSTRACT

DISTANCE FOREIGN LANGUAGE LEARNERS’ LEARNING BELIEFS AND READINESS FOR AUTONOMOUS LEARNING

GÖÇMEZ, Lutfiye

Master, Department of English Language Teaching Advisor: Assoc. Prof. Dr. Gonca YANGIN EKŞİ

February-2014, 91 Pages

Distance education is a new educational area, which needs to be developed in terms of the curriculum, instruction and material in Turkey. However, there is a lack of research on distance foreign language education in Turkey. For this reason, this thesis aimed to conduct a systematic research on the learning beliefs held by distance foreign language learners and more specifically their readiness for autonomous learning. Moreover, we tried to answer the research questions related to the distance language learners’ beliefs and their level of readiness for autonomy in terms of gender, age, the latest degree obtained, and employment state variables. This study was designed to use a quantitative research method to elicit data for the analysis via applying Cotterall’s (1995) questionnaire for learning beliefs and autonomy and Horwitz’s (Beliefs About Language Learning) BALLI 1988. The participants of the research were 947 first-year distance learners of Gazi University Distance Education Vocational School, who were attending the Foreign Language I class in the Fall Semester of 2012-2013 education years. Then, the obtained data were analyzed via SPSS program and they were interpreted by the researcher. In conclusion, the findings showed that Turkish distance language learners generally held positive beliefs about and were highly extrinsically motivated to learn the foreign language, and they were likely to ready for autonomous learning although there were some differences among the results in terms of their gender, age, the latest degree obtained, and employment state variables.

Key Words: Distance Education, Autonomy, Foreign Language Learning Beliefs,

vi INDEX

Page

Jüri Onay Sayfasi ... ii

Acknowledgements ... iii

Özet ... iv

Abstract ... v

Index ... vi

List Of Tables ... viii

List Of Abbreviations ... x

1. INTRODUCTION ... 1

1.1. Statement of the Problem ... 1

1.2. Aim of the Study ... 2

1.3. Significance of the Study ... 3

1.4. Assumptions of the Study ... 3

1.5. Limitations of the Study ... 4

1.6. Definitions ... 4

2. REVIEW OF LITERATURE ... 5

2.1. Distance Education... 6

2.1.1. Defining Distance Education ... 7

2.1.2. Theoretical Rationale for Distance Education ... 9

2.1.3. History of Distance Education in the World and Turkey ... 10

2.1.4. Distance Language Learning ... 13

2.2. Beliefs about Language Learning ... 16

2.2.1. Studies on Beliefs about Language Learning ... 17

2.2.1.1. Beliefs about Language Learning Inventory (BALLI) ... 19

2.3. Learner Autonomy ... 22

2.3.1. Historical and Theoretical Framework of Learner Autonomy ... 24

2.3.2. Why is Autonomy? ... 26

2.3.3. Characteristics of Autonomous Learners ... 27

2.3.4. Significance of Autonomy in Distance Education ... 28

3. METHOD ... 31

vii

3.2. Sample ... 31

3.3. Data Collection... 32

3.4. Data Analysis ... 33

4. RESULTS ... 35

4.1. Beliefs about Language Learning Inventory (1988) ... 35

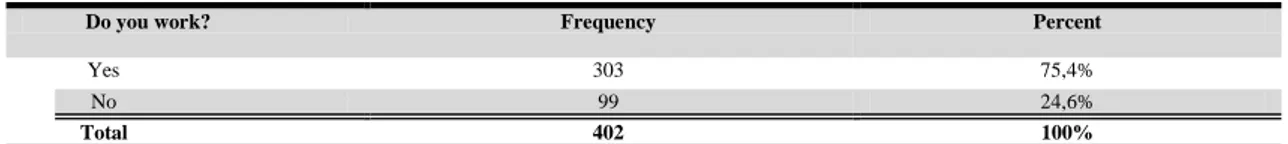

4.1.1. Demographic profile of the participants ... 35

4.1.2. Foreign language aptitude, BALLI items 1, 2, 10, 15, 22, 29, 32, 33, 34 ... 36

4.1.3. The difficulty of la nguage learning, BALLI items 3, 4, 5, 6, 14, 24, 28 .... 38

4.1.4. Nature of language learning, BALLI items 8, 11, 16, 20, 25, 26 ... 39

4.1.5. Learning and communication strategies, BALLI items 7, 9, 12, 13, 17, 18, 19, 21 ... 40

4.1.6. Motivation and expectation, BALLI items 23, 27, 30, 31 ... 42

4.2. Cotterall’s Questionnaire for Autonomy (1995) ... 43

4.2.1. Demographic profile of the participants ... 43

4.2.2. The role of teacher, items 5, 13, 27, 28, 29, 30, 31, 32, 33, 34 ... 44

4.2.3. The role of feedback, items 7, 8, 10, 21, 22 ... 49

4.2.4. Learner independence, items 9, 12, 15, 19, 20, 23 ... 53

4.2.5. Learner confidence in study ability, items 2, 3, 4, 6, 16 ... 57

4.2.6. Experience of language learning, items 11, 17, 18 ... 61

4.2.7. Approach to studying, items 1, 14, 24, 25, 26 ... 64

5. CONCLUSION AND IMPLICATIONS ... 68

REFERENCES ... 74 APPENDIXES ... 83 APPENDIX – 1 ... 83 APPENDIX – 2 ... 85 APPENDIX – 3 ... 88 APPENDIX – 4 ... 90

viii

LIST OF TABLES

Table 1: Gender Distribution of the Participants ... 35

Table 2: Age Distribution of the Participants ... 36

Table 3: Latest Degree Obtained of the Participants ... 36

Table 4: Employment State of the Participants ... 36

Table 5: Gender and Foreign Language Aptitude ... 37

Table 6: Gender and the Difficulty of Language Learning ... 39

Table 7: Gender and Nature of Language Learning ... 40

Table 8: Gender and Learning and Communication Strategies ... 41

Table 9: Gender and Motivation and Expectations ... 42

Table 10: Gender Distribution of the Participants ... 43

Table 11: Age Distribution of the Participants ... 43

Table 12: Latest Degree Obtained of the Participants ... 44

Table 13: Employment State of the Participants ... 44

Table 14: Gender and the Role of Teacher ... 45

Table 15: Age and the Role of Teacher ... 47

Table 16: Employment State and the Role of Teacher ... 48

Table 17: Latest Degree Obtained and the Role of Teacher ... 49

Table 18: Gender and the Role of Feedback ... 50

Table 19: Age and the Role of Feedback ... 51

Table 20: Employment State and the Role of Feedback ... 52

Table 21: Latest Degree Obtained and the Role of Feedback ... 52

Table 22: Gender and Learner Independence ... 54

Table 23: Age and Learner Independence ... 55

Table 24: Employment State and Learner Independence ... 56

Table 25: Latest Degree Obtained and Learner Independence ... 56

Table 26: Gender and Learner Confidence in Study Ability ... 58

Table 27: Age and Learner Confidence in Study Ability ... 59

Table 28: Employment State and Learner Confidence in Study Ability ... 60

Table 29: Latest Degree Obtained and Learner Confidence in Study Ability ... 60

Table 30: Gender and Experience of Language Learning ... 61

Table 31: Age and Experience of Language Learning ... 62

ix

Table 33: Latest Degree Obtained and Experience of Language Learning ... 63

Table 34: Frequency Distribution of Item 24 ... 64

Table 35: Gender and Approach to Studying ... 65

Table 36: Age and Approach to Studying ... 66

Table 37: Employment State and Approach to Studying ... 67

x

LIST OF ABBREVIATIONS

AIT The Asian Institute of Technology

AUOEF Anadolu University Open Education Faculty

BALLI Beliefs About Language Learning Inventory

CB Cognitive Behaviourist

CMC Computer Mediated Communication

DE Distance Education

DELLT Distance English Language Teacher Training

EAP English for Academic Purposes

EFL English as a Foreign Language

EFRT Education via Film, Radio and Television

ESL English as a Second Language

EU European Union

FLT Foreign Language Teaching

MANOVA Multivariate Analysis of Variance

METU Middle East Technical University

MOOs Multi-user Object-oriented domains

MNE (Turkish) Ministry of National Education OUUK Open University of the United Kingdom

RATIO Rural Area Training and Information Opportunities

TSL Turkish as a Second Language

UMS Universiti Malaysia Sabah

1. INTRODUCTION

In recent years, with the effect of European Union’s ‘Lifelong Learning’ objective all around Europe, distance education has gained a considerable attention among educators, university administrators and learners in Turkey. Distance education is advantageous in many ways such as flexible access to learning resources in time and space, the opportunity to study at your home’s comfort, and enabling those with jobs and/ or family commitments to study. In other words, distance education reinforces the continuing education and the learner autonomy which are both the musts of the modern education system. However, the demands of distance education from the learner are much more than the traditional face-to-face education contrary to the widespread opinion that the distance education programs are much easier to pass than the traditional ones. Because, as Zhang and Cui (2009) have stated “Within the limits of instructional design, distance learners can make their own decisions about when and how to study”. Therefore, distance language learners are generally required to be more self-regulated and autonomous in their learning comparing to the traditional language learners. At this point, the language learning beliefs they hold are crucial for their potential for being successful in language learning at a distance and readiness for autonomy. In conclusion, this thesis aims at conducting a systematic research on the learning beliefs held by distance foreign language learners and more specifically their readiness for autonomous learning.

1.1. Statement of the Problem

Distance education is a new educational area, which needs to be developed in terms of the curriculum, instruction and material in Turkey. Thus, there is a lack of research on distance foreign language education in Turkey. Many leading scholars state that the learning beliefs the learners hold have a great impact on learners’ behaviours. For this reason, this thesis aims to conduct a systematic research on the learning beliefs

held by distance foreign language learners and more specifically their readiness for autonomous learning and find the answers to the following questions:

What are Turkish distance language learners’ beliefs about foreign language learning?

Is there any difference between the distance language learners’ beliefs about foreign language learning according to sex?

Are Turkish distance language learners ready for autonomous learning?

Are the levels of readiness for autonomy of the male and the female distance language learners the same?

Does the level of readiness for autonomy differ according to the age group of the distance language learners?

Does the level of readiness for autonomy differ according to the employment state of the distance language learners?

Does the level of readiness for autonomy differ according to the latest degree obtained by the distance language learners?

1.2. Aim of the Study

In this study, the researcher aims to find out Turkish distance language learners’ beliefs about the role of feedback, the role of teachers, the strategies and self-efficacy through distance education and their readiness for autonomy. Because, for distance language learners, ‘capacity’ and ‘readiness’ need to become actualised rapidly as abilities and skills. Distance learning students are no more homogeneous than classroom learners, but they are by definition less accessible. This presents a real challenge to all course designers, task writers and tutors to devise ways of supporting their learners at a distance in developing the skills of self-management and self-regulation that are central to autonomy (Hurd, 2005: 19). Moreover, Cotterall argues further that ‘the beliefs learners hold may either contribute to or impede the development of their potential for

autonomy’ (1995: 196), thus making explicit a link between beliefs and autonomy is vital for FLT research era.

1.3. Significance of the Study

This subject will be investigated for three reasons: firstly, the previous researches indicate that learning beliefs play a crucial role in learning experience and achievement. Thus, as Wenden (1986) emphasize we educators should “... discover what... students believe or know their learning, and to provide activities that would allow students to examine these beliefs and their possible impact on how they approach learning ....” (as cited in. Cotterall, 1999: 494). Secondly, each factor of the survey of language learning beliefs is related to autonomous language learning behaviour so we can see the distance language learners’ level of readiness for autonomy, which is the key part of distance education. As Murphy (2008) notes “distance learners may be assumed to be learning autonomously because they control a number of aspects of their learning including the time, the pace, what to study and when to study”. Moreover, Cotterall (1995: 195) argues that “before interventions aimed at fostering autonomy are implemented, it is necessary to gauge learners' readiness for the changes in beliefs and behaviour which autonomy implies”. Lastly, As Yıldırım (2008) proposes “Since the perception of autonomy changes according to different cultural and educational conditions, before making any attempt to promote learner autonomy, we should investigate students’ readiness for autonomous learning” (p. 67). Thirdly, although a limited number of studies have been conducted on learner beliefs, there is almost no study on learning beliefs of distance language learners and their readiness for autonomy, especially in Turkey.

1.4. Assumptions of the Study

In this research, it is presupposed that

Turkish distance language learners are ready for autonomous learning.

1.5. Limitations of the Study

Although we try to minimize the probable limitations in the study, we have some: First limitation is related to the instrument and the nature of research design. In nature we need to design a quantitative research and apply the questionnaires to assess the distance language learners’ beliefs about language learning and their readiness for autonomy. As a normative approach, although the questionnaires of learning beliefs provide clarity and precision, it has limitations too as Bernat and Gvozdenko (2005) mention; “The beliefs profiled in normative studies are only those identified by the research and therefore, are not all the beliefs learners might hold about language learning. There is also potential for misunderstanding of questionnaire items”. Another limitation is that the results of the present study were based on the quantitative data collected from participants through questionnaires. Also, triangulation might have been conducted to gather more detailed information from the respondents.

1.6. Definitions

Distance Education: Distance education generally refers to the provision of

learning resources to remote learners, which involves both distance teaching – the instructor’s role in the process – and distance learning – the student’s role – (Palloff & Pratt, 1999).

Synchronous Distance Education: The synchronous model is a model which

enables a teacher and student to communicate in real time, through different spaces (White: 2003).

Asynchronous Distance Education: An e-learning model in which the student

and teacher do not have to communicate in real time, and provides an opportunity for the learner to complete his/ her education at his/ her own learning speed and time (White: 2003).

Learning Beliefs: Language learners form ‘mini theories’ of L2 learning

(Hosenfeld, 1978) which shape their way they set about the learning task. These theories are made up of beliefs about language and language learning.

Learner Autonomy: Autonomy is a situation in which the learner is totally

responsible for all the decisions concerned with his [or her] learning and the implementation of those decisions (Dickinson, 1987).

2. REVIEW OF LITERATURE

Palloff and Pratt (1999) define that distance education generally refers to the provision of learning resources to remote learners, which involves both distance teaching – the instructor’s role in the process – and distance learning – the student’s role (as cited in. Zhang & Cui, 2010, p. 31). Also, it can be described as the use of educational media to unite teacher and learner have a course together and communicate with each other in the situations where the teacher and the learner are separate in space or/ and time.

The synchronous model enables a teacher and student to communicate in real time, through different spaces (Karal, Çebi, & Turgut, 2011: 276). It is more advantageous comparing to asynchronous model since it is very similar to face-to face traditional class environment (esp. via video-conferencing) offering real time discussion and brainstorming, and giving instant feedback. Karal, Çebi and Turgut (2011) cite that the asynchronous model is defined as an e-learning model in which the student and teacher do not have to communicate in real time, which provides an opportunity for the learner to complete his/ her education at his/ her own learning speed and time.

The use of technology supports in second/ foreign language pedagogy has a long historical background starting with language labs, going on with videotapes and reaching its peak with internet use (Nunan, 2010). As Nunan states, technology is used in second/ foreign language learning for three major roles as a) a carrier of content and an instructional tool, b) a learning management tool, and c) a communication tool (2010).

Cotteral claims that “Learners approach the task of learning another language in different ways according to various individual characteristics” (1999). One of these characteristics is the learning beliefs they hold about language learning. Many studies suggest that beliefs are important in learning experience and achievements. Ehrman and Oxford (1995) report that “Believing that one can learn languages well was significantly correlated with proficiency in both speaking and reading”.

The learning beliefs the learners hold have a great impact on learners’ behaviours. McDonough (1995) points out that beliefs can be important stimuli for action:

... what we believe we are doing, what we pay attention to, what we think is important, how we choose to behave, how we prefer to solve problems, form the basis for our personal decisions as to how to proceed. An important fact about this argument is that it is not necessary for these kinds of evidence to be true for them to have important consequences for our further development (cited in Cotterall, 1999).

2.1. Distance Education

In recent years, with the effect of European Union’s ‘Lifelong Learning’ objective all around Europe, distance education has gained a considerable attention among educators, university administrators and learners in Turkey. Distance education is advantageous in many ways such as flexible access to learning resources in time and space, the opportunity to study at your home’s comfort, and enabling those with jobs or/ and family commitments to study. Januin (2007: 17) explains the motives encouraging the working adults to opt for distance education as “constraints in terms of finance, far distance between their workplace and the institutions they wish to enrol at, limited time allocated for lectures and tutorials due to the current work requirements”. As Brown (2001) has noted, unlike the industrial era when skills needed were relatively fixed, today education is needed to meet employers’ growing demand for continually evolving skills. Similarly, Gunawardena and McIsaac (2004: 356) underline an important point that “although there is an increase in the number of distance services to elementary and secondary students, the main audience for distance courses continues to be the adult and higher education market”. Therefore, distance learning provides a convenient, flexible, manageable alternative for this developing segment of society. Moreover, Anderson and Dron (2009) have highlighted the significance of benefiting from both technology and pedagogy in the learning and instructional designs with these words “the two being intertwined in a dance: the technology sets the beat and creates the music, while the pedagogy defines the moves”. To summarize, Gunawardena and McIsaac (2004: 356) state that distance education has experienced dramatic growth both nationally and internationally since the early 1980s and it has evolved from early correspondence

education using primarily print based materials into a worldwide movement using various technologies. Then, they add (2004: 356) that distance education relies heavily on communications technologies as delivery media such as print materials, broadcast radio, broadcast television, computer conferencing, electronic mail, interactive video, satellite telecommunications and multimedia computer technology to promote student-teacher interaction and to provide necessary feedback to the learner at a distance.

2.1.1. Defining Distance Education

Although there is no single definition of distance education, the terms of

distance education and distance learning are used synonymously. There are series of

definitions; however, all of them emphasize distance in space and/or time between teacher and learner. Some of them are as follows:

Keagon (1990) states that the definitions of distance education generally include these components: the separation of teacher and learner in time and/or space; the influence of an educational organisation (which distinguishes distance learning from private study context); the use of a range of media and communication devices; the possibility of face-to-face contact; and the provision of a range of support devices (cited in White, 2003: 12). Desmond Keegan (1980) identified six key elements of distance education: (1) Separation of teacher and learner; (2) Influence of an educational organization; (3) Use of media to link teacher and learner; (4) Two-way exchange of communication; (5) Learners as individuals rather than grouped; (6) Education as an industrialized form (cited in Gunawardena and McIsaac, 2004: 358). Gunawardena and McIsaac (2004) declare that definitions of distance education “... vary with the distance education culture of each country, but there is some agreement on the fundamentals” (p. 358). For example, colleges and universities in the United States offer existing courses through distance learning programs as an alternative to traditional attendance. On the other hand, the United Kingdom, who was the first to develop an Open University on a large scale, describes their distance strategies as flexible or open learning. Palloff and Pratt (1999) define that distance education generally refers to the provision of learning resources to remote learners, which involves both distance teaching – the instructor’s role in the process – and distance learning – the student’s role – (as cited in. Zhang &

Cui, 2010: 31). In summary, it can be described as the use of educational media to unite teacher and learner having a course together and communicate with each other in the situations where the teacher and the learner are separate in space or/ and time.

As mentioned above the definition of the distance education is in short “the separation of teacher and learner in time and/or space”. At this point we need to mention about the models of distance education: synchronous learning, asynchronous

learning, multi-synchronous learning and blended learning. Firstly, synchronous

distance learning uses ‘real time’ communication technologies such as the telephone, chat room, video-conferences. Since the time and opportunity for learners to participate is more controlled, it can be claimed that it is less flexible. However, synchronous distance learning systems can be highly motivating as the learners can have the feeling of being in a community and get immediate feedback from the teacher or learning group. Secondly, asynchronous learning takes place between the student and the teacher in different times and places via print, video, CD-ROM, e-mail, computer conference discussions and computer mediated communication (CMC) tools. As White (2003: 9) mentions the advantage of asynchronous interaction is that “learners can practice and respond at their convenience, there is time for thought and reflection between responses...” Learners can access to the content or communication whenever and wherever they desire. Thirdly, the term multi-synchronous was first used by Mason (1998) to refer to the combination of both synchronous and asynchronous media with the aim of benefiting from the advantages of both systems (cited in White, 2003: 20). One instance for this type of distance learning is Christine Uber Grosse’s (2001) satellite television internet based distance language programme called English Business Communication, which brought together these elements: interactive satellite television linking remote classes (synchronous); internet-based web boards for chatting (synchronous) and for posting and reviewing homework (asynchronous); e-mails (asynchronous); and face-to-face orientation meetings at the start of the course (synchronous). Finally, Bonk and Graham (2006: 5) define blended learning as “... systems combining face-to-face instruction with computer-mediated instruction”. They add (2006) that there is an ongoing convergence of two learning environments for some reasons such as “pedagogical richness, access to knowledge, social interaction, personal agency, cost-effectiveness, and ease of revision” (p. 8); and conclude “... we can be pretty certain that the trend toward blended learning systems will increase” (p. 7).

2.1.2. Theoretical Rationale for Distance Education

In their paper ‘Three Generations of Distance Education Pedagogy’, Anderson and Dron (2009: 82-90) introduce a typology in which distance education pedagogies are mapped into three distinct generations in a chronological order: (1) the cognitive-behavioural generation of distance education, (2) the social-constructivist generation of distance education, and (3) the connectivist generation of distance education:

Firstly, the cognitive –behaviourist (CB) pedagogies, which were developed in the latter half of the 20th century, focus on the philosophy of learning was “predominantly defined, practiced, and researched”. CB models defined the first generation of individualized distance education, which maximize access and student freedom at lower costs via mainly one-to-one communication tools such as postal services of print packages, mails, mass media (radio programs and/or television videos), telephone conversations at the mean while they reduce the social presence by focusing on individualized learning, and the cognitive presence by “using an instructional systems design model where the learning objectives are clearly identified and stated and exist apart from the learner and the context of the study”. In short, the cognitive-behaviourist pedagogy of distance education is mainly based on the ways of transmitting information with very limited level of interaction.

Secondly, the social-constructivist pedagogies, of whose roots based on the works of Vygotsky and Dewey, “developed in conjunction with the development of two-way (synchronous and asynchronous) communication technologies” such as e-mails, bulletin boards, the World Wide Web tools and mobile technologies. Thus, Garrison (1997) and others argue that constructivist-based learning, with rich student-student and student-student-teacher interaction constituted a new, ‘post-industrialist era’ of distance education. In summary, the social-constructivist pedagogy of distance education is “beyond the narrow type of knowledge transmission” with the use of synchronous and asynchronous rich human interactions; however, it is a more costly way of distance education and there are some limits on accessibility.

Thirdly, the connectivist pedagogy of distance education, which has recently been defined by George Siemens and Stephen Downes, assumes that “information is plentiful and that the learner’s role is not to memorize or even understand everything,

but to have the capacity to find and apply knowledge when and where it is needed” and “mental processing and problem solving can and should be off-loaded to machines”. Anderson and Dron (2009: 92) state that “Connectivism is built on an assumption of a constructivist model of learning, with the learner at the centre, connecting and constructing knowledge in a context that includes not only external networks and groups but also his or her own histories and predilections”. In the connectivist pedagogy of distance education, the learners are exposed to networks and are assumed to “gain a sense of self-efficacy in contributions to wikis, Twitter, threaded conferences, Voice threads, and other network tools. Furthermore, the content of learning is created and re-created by the learners and the teachers for future use by others via comments, contributions and student reflections on the networks. Thus, the most common problems of this pedagogy are that the students feel themselves lost and confused in a connectivist setting, and the connectivist models are “hard to translate into ways to learn and harder still to translate into ways of to teach”.

In brief, Cognitive-behaviourist pedagogical models arose in a technological environment that constrained communication to the pre-Web, one, and one-to-many modes; social-constructivism flourished in a Web 1.0, one-to-many-to-one-to-many technological context; and connectivism is at least partially a product of a networked, Web 2.0 world. It is tempting to speculate what the next generation will bring. Some see Web 3.0 as being the semantic Web, while others include mobility, augmented reality, and location awareness in the mix (Hendler, 2009).

2.1.3. History of Distance Education in the World and Turkey

In the first generation of distance education, the interaction between teacher and learners was ‘one-way’ via posting print materials and mails up to the 1960s. The second generation course model benefited from a range of media such as television and radio broadcasts, telephone, videocassettes and audiocassettes in addition to the print materials, which are examples of the use of technology for distribution. In the third generation of distance education, information and communication technologies such as CD-ROMs, internet resources, e-mails, bulletin boards, moodles etc. became widely used. The most significant difference of the third generation of distance education is the

use of technology for interaction between the teacher and the learners and between the learners themselves (White, 2003: 13-15). Anderson and Dron (2011) consider that there are three generations of distance education: The first generation of distance education technology was by postal correspondence. This was followed by a second generation, defined by the mass media of television, radio, and film production. Third-generation distance education (DE) introduced interactive technologies: first audio, then text, video, and then web and immersive conferencing. It is less clear what defines the so-called fourth- and even fifth-generation distance technologies except for a use of intelligent data bases (Taylor, 2001) that create “intelligent flexible learning” or that incorporate Web 2.0 or semantic web technologies.

Distance Education is not a new concept in both the USA and Europe. In the late 1800s, at the University of Chicago, the first major correspondence program in the United States was established, in which the teacher and learner were writing letters to each other at different locations. Before that time, particularly in preindustrial Europe, education had been available primarily to men from the elite class. Therefore, correspondence study was designed to provide educational opportunities for those who were not among the elite and who could not afford full time residence at an educational institution by educators like William Rainey Harper in 1890.

As radio developed during the First World War and television in the 1950s, radio and television broadcasts replaced the correspondence instruction. For instance, Wisconsin’s School of the Air in the 1920s was just one example of radio and television usage in schools to deliver the instruction at a distance. Moreover, Open University in Britain established in 1970 and Charles Wedemeyer’s innovative uses of media in 1986 at the University of Wisconsin followed it. The establishment of the British Open University in the United Kingdom in 1969 marked the beginning of the use of technology to supplement print based instruction through well designed courses. Compared to the Europe, the United States was slow to enter the distance education marketplace; however, it was able to accelerate the growth of distance education programs in the late 1980s. And, perhaps the most important report describing the state of distance education in the 1980s was done for Congress by the Office of Technology Assessment in 1989 called Linking for Learning. After then, some projects, such as the Panhandle Shared Video Network and the Iowa Educational Telecommunications

Network, have served as examples of operating video networks which are both efficient and cost effective (Gunawardena and McIsaac, 2004: 356-358).

Gunawardena and McIsaac (2006: 387) conclude that since 1970s, the British Open University has been providing leadership to developing countries such as Pakistan, India, China and Turkey. They especially emphasise “Turkey has recently joined those nations involved in large-scale distance learning efforts” and add “one example of a rapidly growing mega-university is Anadolu University in Turkey” with its 20-years background and with its over 600,000 students.

Distance education in Turkey started with Turkish Ministry of National Education‘s language classes through radio broadcasts and went on with the opening of Turkish Ministry of National Education Open High School and Open Primary School, Anadolu University Open Education, Open Faculty of METU, Fono publishing and Limasollu Naci publishing.

Fono publishing, which was established in 1953, and Limasollu Naci publishing were the first correspondence programs known in Turkey. They started their courses with posting mails and went on with posting print material as books and dictionaries, and audio-cassettes to their students at distance throughout the years. Now, they continue conducting the distance courses on internet. Turkish Ministry of National Education (MNE) began to teach English, French and German via radio broadcasts in order to supplement face-to-face language classes in the traditional schools in the 1970s. Moreover, in 1980s Education via Film, Radio and Television Centre (EFRT) of Turkish Ministry of National Education cooperated with TRT and produced many audio-visual courses and broadcasted these films through television so as to help the high school students with their classes at the school and to prepare them for university education. In 1992, Open High School was founded in order to encourage the drop out students to complete their higher education at a distance. Following that, in 1998 Open Primary School opened and so the students who were older than 15 and had not finished primary education yet were able to complete their primary education at a distance. Anadolu University Open Education Faculty (AUOEF), which is one of the biggest open universities in Europe now, was established in 1982 to provide tertiary education to the students who could not attend a formal class for any reason. The major motives of Anadolu University Open Education Faculty (AUOEF) were to meet the educational

problems such as lacking number of schools at every level, inadequate opportunity of high education for everyone, lacking number of qualified instructors and a need for educated person in technical areas (Koç, 2011: 115). In 2000, because of an increasing demand for language teachers in Turkey resulting from the 1997 education reform framework, Distance English Language Teacher Training (DELLT) program was launched at Anadolu University. DELLT was planned to be the only blended four-year undergraduate program in Turkey, in which the first two years are delivered face-to-face and the last two years through distance education (Kecik, 2011: 74). Then, Middle East Technical University started internet-based instruction in the name of ‘Distance Interactive Learning’ so as to prepare the students for both national and international language proficiency exams like KPDS, TOEFL and IELTS (Adıyaman, 2002).

2.1.4. Distance Language Learning

Although many institutions, language teachers and language learners may encounter with distance education quite recently, the concept of language learning at a distance is not a new phenomenon. In fact, it has a historical background going back to the long ago, which started with mail sending and receiving, printed materials sending, radio and television broadcasts, and went on with online learning, virtual worlds, learning management systems in parallel with the developments in information and communication technology. White (2003) states that

distance language programmes include a wide range of elements and practices ranging from traditional print-based correspondence courses, to courses delivered entirely online with extensive opportunities for interaction, feedback and support between teachers and learners, and among the learners themselves” (p. 3).

Moreover, she (2003: 2) emphasizes that “more than 1,300 language courses were registered – out of a total of 55,000 distance courses from 130 countries” and this number is growing day by day. In addition, sophisticated software and growing expertise in the use of CMC for language learning make it possible today for language learners to communicate not just with one other person asynchronously through e-mail, but with groups of other learners either asynchronously or synchronously, through

bulletin boards, text chat, audio-video conferencing or Multi-user Object-oriented domains (MOOs), as part of a virtual community (Hurd, 2005: 17).

Despite of the plentiful benefits of distant technology use in language classrooms many scholars may still be sceptic about the effectiveness of these courses at a distance. In her book (2003) Language Learning in Distance Education, for those colleagues, White introduces four distance language courses as examples of learning environment designs, course development and delivery procedures. The first one is a technology-based course in intermediate Spanish by Rogers and Wolff (2000) at Pennsylvania State University. The course was built around a combination of hi-tech and low-tech consisting of e-mail – for asynchronous writing, chat room – for real-time communication exercises, computer-aided grammar practice, and web-based cultural expansion modules – for reading Spanish. At the end of the course, “based on their experience Roger and Wolff see the greatest challenges in distance language learning as reduced opportunity for cohort-based learning and immediate, personalized feedback”. The second one is a multimode course in thesis writing for graduate students by David Catterick (2001) at the University of Dundee, Scotland. It was multimode (blended): half accessed in face-to-face traditional classes and half via WebCT (Worldwide Web Course Tools). After a face-to-face orientation programme within first weeks, the students accessed materials and completed online tasks using WebCT. At the end of the study, Catterick concludes that the text-based nature of WebCT was well-suited for a writing course. The third course is pre-sessional English for Academic Purposes (EAP) course by Boyle (1994, 1995) at the Asian Institute of Technology (AIT) in Thailand. This distance course was developed to enable the students, who had difficulty in attending a face-to-face pre-sessional course, and to prepare themselves for initial course work via recordings of talks and lectures, attached readings and other materials. The Boyle study showed that distance learning contexts can be used as complement to traditional face-to-face instruction. The last course she introduces is a vocational French language course delivered by Laouenan and Stacey (1999) as a part of European Union-funded project called RATIO (Rural Area Training and Information Opportunities). The course “consisted of satellite broadcast followed by videoconferencing sessions”. Their study was an example of “just-in-time distance learning that is developed for a particular group with specific needs at relatively short notice. As it can be clearly seen from these four courses mentioned, White (2003)

concludes that distance education can be applied to language programmes within various different ways (p.3-8). Moreover, Trajanovic et al. (2007) implemented a set of three academic English courses through three semesters both traditionally and as distance learning and concluded that “distance learning students on the whole score higher than the traditional ones” on exams (p. 451).

However, we should accept that distance language learning may have some drawbacks, too. For instance, As Peter (1998) mentions, in distance language learning “written teaching dominates in contrast to spoken teaching; and so learning by reading is stressed rather than learning through listening”. This has important implications for the development of oral and aural skills and interactive competence in distance language learning (cited in White, 2003: 12-13). Furthermore, distance education is characterized by potentially anxiety-provoking elements such as “isolation, competing commitments, absence of the structure provided by face-to-face classes, and difficulty in adjusting to the new context” (Bown, 2006: 642). Distance learners, therefore, have to take more responsibility for their own learning than conventional students (cited in Hurd & Xiao, 2010: 185).

On the other hand, the distance language course design and curriculum are very crucial so the teacher who is to design and instruct is assumed to have some qualifications. Shelley et al. (2006: 3) summarize the qualifications needed for being an efficient distance language tutor: First, they must be complemented by a personal commitment to the education of adults, and an appreciation of the challenges that face adult learners who are studying at a distance. Then, these tutors might be expected to have a degree or equivalent in the relevant language, and to be a native speaker or to have a near-native speaker competence. Last, they are required to demonstrate a commitment to communicative language-teaching methodology and to have a broad understanding of the societies and cultures of the country in question. However, the same qualifications might be required of a classroom teacher. Shelley et al.’s study about perspectives on tutor attributes and expertise in distance language teaching was conducted in OUUK and Massey University, New Zealand with a small team of academics (2006). It resulted that:

Tutors who work within distance education differ markedly from their classroom counterparts in terms of the roles they assume, the ways in which they interact with

students, and the attributes and expertise required of them. All these dimensions have changed and will continue to change in response to shifts in technology, the development of learning environments, and in line with political and institutional factors such as the availability of funding and quality control procedures (2006: 12).

2.2. Beliefs about Language Learning

Many studies suggest that beliefs are important in learning experience and achievements. Richardson (1996: 103) defines beliefs as “psychologically held understandings, premises, or propositions about the world that are felt to be true”. Moreover, Cotteral (1999) claims that “Learners approach the task of learning another language in different ways according to various individual characteristics. One of these characteristics is the learning beliefs they hold about language learning”. Hence, the learning beliefs the learners hold have a great impact on learners’ behaviours. McDonough (1995) points out that beliefs can be important stimuli for action:

... what we believe we are doing, what we pay attention to, what we think is important, how we choose to behave, how we prefer to solve problems, form the basis for our personal decisions as to how to proceed. An important fact about this argument is that it is not necessary for these kinds of evidence to be true for them to have important consequences for our further development (cited in Cotterall, 1999).

Besides, Ehrman and Oxford (1995) report that “Believing that one can learn languages well was significantly correlated with proficiency in both speaking and reading”. As cited in White’s research (1999), two such claims serve as useful background to this study: beliefs help individuals to define and understand the world and themselves, and as such have an adaptive function (Abelson, 1979; Lewis, 1990); beliefs are instrumental in defining tasks and play a critical role in defining behaviour (Bandura, 1986; Nespor, 1987; Schommer, 1990). Beliefs can be defined as ``mental constructions of experience'' (Sigel, 1985: 351) that are held to be true and that guide behaviour. Consequently, according to a survey done for the European Year of Languages (2001), 22% of the EU population do not learn languages because they believe they are ‘not good’ at them (Hurd, 2005: 11).

2.2.1. Studies on Beliefs about Language Learning

In second language acquisition and foreign language learning research there has been a recent shift towards the importance of the learner’s point of view regarding how their own beliefs and backgrounds play a role in their language learning experiences. Many researches have been conducted on language learning beliefs; however, among those researches Dr. Elaine Horwitz’s studies – from University of Texas – may be accepted as pioneer. Firstly, Horwitz (1999) reviewed seven representative studies conducted with different cultural groups (Americans learning foreign languages, and Turkish, Korean, and Taiwanese students learning English as a foreign or second language) to examine how learners’ beliefs may differ across cultures. Horwitz (1988) catalogued the beliefs of first semester American university students of French, German, and Spanish; Kern (1995) collected and compared the beliefs of American university French students and their instructors; Oh (1996) examined the beliefs of American university students of Japanese, Kunt (1997) compared the beliefs of two groups of Turkish and Turkish-Cypriot pre-university learners in North Cyprus; Park (1995) and Truitt (1995) both used a sample of Korean university students of English; and Yang (1992) studied the beliefs of Taiwanese university students of English. Subsequently, Horwitz’ (1999) study concludes that ‘within-group differences’ are likely to account for as much variation as the ‘cultural differences’ and ‘there is not strong evidence for a conclusion of cultural differences in learner beliefs’. Moreover, Horwitz conducted her research among students and instructors at the University of Texas at Austin. Subsequent studies employed Horwitz’s instrument for inquiries abroad. For example, Yang (1992) explored beliefs about language learning among English language students at six Taiwanese universities; Park (1995) investigated beliefs of English language learners at two universities in Korea; Truitt (1995) also conducted her study in Korea among Yonsei University students learning English. of English language learners have not been the only focus in such studies. Studies with other subjects are as follows: Horwitz (1988) conducted research among students of Spanish, French and German at the University of Texas at Austin. Kuntz (1996b) included learners of Arabic and Swahili in her studies. Smith (1989) and Tumposky (1991) investigated beliefs of Russian language learners. Kern (1995) used Horwitz’s model to assess beliefs of students learning French. Bacon and Finneman (1990)

surveyed beliefs of Spanish language students. Mori (1999) concentrated on learners of Japanese (cited in Nikitina & Furuoka, 2006: 210).

In addition to those, Young (1991) lists learner beliefs as one source of foreign language learning anxiety: personal and interpersonal issues, instructor-learners interactions, classroom procedures, language testing, instructor beliefs about language learning, and learner beliefs about language learning. Then, in Ariogul’s et al. local study of BALLI with Turkish foreign language learners (2009), whose purpose was to compare English, German and French foreign language groups’ beliefs among the categories of BALLI and to discover the areas of similarity and differences, has concluded that all three groups’ beliefs have been found slightly different from each other. Their (2009) research findings were in parallel with Horwitz’s (1988) study conducted with American foreign language students in most BALLI factors. However, Turkish students appeared to be more motivated to learn a foreign language than their American peers are since they consider it as an opportunity for their future career. Moreover, Kunt’s study addressing Turkish as a Second Language (TSL) learners’ beliefs about language learning in North Cyprus found that international Turkish as a Second Language (TSL) students in North Cyprus possessed mainly different beliefs about language learning from those of international ESL students in the United States (Horwitz, 1987), EFL students in Korea (Truitt, 1995), French and EFL students in Lebanon (Diab, 2000), and Turkish EFL students in North Cyprus; and, it revealed that “According to the BALLI results, international university students seemed to have integrative motivation to learn Turkish that is related to learning target language culture”. Afterwards, Akhtar and Kausar (2011) conducted a study in Pakistani schools with 101 students and 17 teachers of English. A close questionnaire, framed in Likert-scale as designed by Lightbown and Spada (1993) was administered. As a result, their research illustrated that ‘while there was an agreement between the beliefs of teachers’ and students’ with regard to teaching and learning of English, they differed on several accounts’. Lastly, Peng’s study Changes in language learning beliefs during a

transition to tertiary study: The mediation of classroom affordances (2011) revealed

that learner beliefs about English Language and its teaching and learning approaches may change substantially through a transitional period from high school to college study.

In summary, according to the findings reviewed above, beliefs about language learning are independent constructs that consist of multiple dimensions. These beliefs seem to be context specific and may vary depending on the amount of learning experience learners have received.

2.2.1.1. Beliefs about Language Learning Inventory (BALLI)

Although early studies explored and listed learners’ beliefs about language learning, no scale was available that systematically measured beliefs of learners concerning language learning until the late 1980s when Horwitz became the first, who systematically assessed learners’ beliefs using instruments based on scaled systems. She (1999) emphasized that as the learner has become accepted as an active participant in the language learning experience, the teachers have started to consider the learners’ strategies and motivations as integral elements in the design and implementation of effective language instruction. In 1987 and 1988, Horwitz argued that it was important to understand learner beliefs about language learning in order to understand learner approaches to and satisfaction with language instruction and offered an instrument, the ``Beliefs About Language Learning Inventory (BALLI)'', to collect these beliefs systematically.

In a chain of studies, Horwitz developed three different instruments to define teachers’ and students’ perceptions of language learning. First instrument was developed to assess teacher’s beliefs about language in 1985 in four major areas: foreign language aptitude, the difficulty of language learning, the nature of language learning, and appropriate language-learning strategies. It was composed of 27 Likert-scale items, which was applied to 25 language teachers of various cultural backgrounds. Horwitz’s second version of BALLI – the ESL/ EFL version – in 1987 so as to measure students’ beliefs about the nature of language and the language learning process. This ESL/ EFL BALLI consisted of 33 items in five main areas: foreign language aptitude, the difficulty of language learning, the nature of language learning, learning and communication strategies, and motivation. She developed the latest version of BALLI in 1988 adapting the 1987 version to Americans in order to assess the beliefs of American students of foreign languages about language learning (Hong, 2006). In other

words, as Kuntz (1996a) states that today, three distinct BALLIs are in use: one for ESL students (1984, 1987), second for foreign language teachers (1985), and the last for foreign language students (1988, 1990). The ESL and teacher BALLIs consist of 27 statements while the foreign language BALLI comprises 34 items each is in five point Likert-scale delineating points of agreement for response encodement.

Horwitz’s instruments of language learners’ beliefs are widely accepted as reliable and valid among the scholars. For instance, Nikitina and Furuoka’s study (2006) carried out at Universiti Malaysia Sabah (UMS) with the participants of 107 Russian language learning students from various ethnic aimed to assess the reliability of the instrument BALLI (1988) as developed by Horwitz. The findings of their research has supported ‘the proposition that language learning beliefs are systematic’, and ’items that describe beliefs can be separated into distinct, interpretable and independent dimensions’. Moreover, the validity of Horwitz’s choice of themes is advocated by many studies such as Yang’s (1992) study clearly identified the ‘foreign language aptitude’ dimension, and Park’s (1995) research, in which the ‘motivation’, ‘strategy’ and ‘aptitude’ themes were distinguishable. And, they (2006) concluded that “… despite criticisms and doubts regarding the reliability of BALLI (Kuntz, 1996) Horwitz’s instrument can be considered to be a suitable tool for conducting research on language learning beliefs in different socio-linguistic settings”.

As cited in Kuntz’s review (1996: 10-29) many scholars have repeated the Horwitz’s study using the BALLI or a variation of it. The followings are just some of them: firstly, Smith (1989) and Nummkoski’s research with students of Russian at the university of Texas-Austin, which resulted in Russian students’ having positive beliefs about language learning. Then, differently from the Horwitz model Bacon and Finnemann (1990) applied a survey comprising 109 statements into 11 factors with 1000 first-year students of Spanish at two Midwestern universities. As a conclusion of their study, they stated that student beliefs “shed light into how individual students anticipate their reactions to components of the foreign language curriculum. Beliefs and attitudes [may] be self-fulfilling” (1990: 469). After then, Campell and Ortiz (1991) repeated the Horwitz study incorporating five additional statements, with 150 military recruits at the US Air Force Academy. In another research, Campbell (1993) redesigned Horwitz’s instrument in seven statements followed by a write-in section conducting

with 70 first-month students of French and Spanish from two Midwestern universities. However, contrasting to Horwitz’s findings, Campbell’s survey resulted that more than 60% students disagreed that foreign language is mostly a matter of learning grammar rules. Next, Tumposky (1991) applied Horwitz’s BALLI to the US students of French and Spanish and the USSR students of English so as to see the effects of culture on language learning beliefs. Thus, his study suggested that “cultural differences were related to motivation and specific learning strategies”. A significant research by Yang (1992) was conducted with Taiwanese non-beginner students of English from six universities. She used a multivariate analysis of variance (MANOVA) to investigate effects of background variables on beliefs and strategy use, and her results indicated that ethnicity and culture influence student beliefs. Moreover, her study became a model for Park (1995) and Truitt (1995), who studied Korean students’ beliefs about English. Afterwards, Fox (1993) investigated the beliefs held by teaching assistants of first-year students of French in New York by utilizing some parts of the BALLI – 26 statements. Accordingly, like Horwitz (1985) Fox concluded that for a successful foreign language teaching and learning, teachers’ awareness of their own beliefs and student beliefs is essential. Then, Kern (1994) utilized 1986 Horwitz model for students of French and their teachers both at the first-semester and at the second-semester as a follow-up study. He aimed to determine any changes in their initial beliefs during the semester. Thus, he concluded that the initial responses of some beliefs did not change over time whereas some responses became even more negative. However, the most striking finding of Kern’s research was that “the teachers’ beliefs did not influence second-semester students as much as other elements in the learning environment”. Most recently, Mantle-Bromley (1995) used the BALLI – deleting four statements associated with the theme ‘Motivation and Expectation’ – for gathering data about students’ of French and Spanish beliefs at middle schools.

In brief, as a valid and reliable instrument, the BALLI has been used widely as a research instrument and as a training instrument in the field of second and foreign language acquisition.

2.3. Learner Autonomy

Language classroom has gained a new standpoint with the development of learner-centred approaches recently. This new approach has changed the roles of learners and teachers in the classroom. Thus, learners are expected to take charge of their own learning, and teachers are supposed to assist learners become more independent inside and outside the classroom. All these improvements in today’s language classroom have brought the concept of ‘learner autonomy” to the field.

What is autonomy? Is it the ‘ability to have and to hold the responsibility for all the decisions concerning all aspects of this learning’ (Holec, 1981: 3) or is it a ‘capacity for detachment, critical reflection, decision-making, and independent action’ (Little, 1991: 4)? Is autonomy a precondition for successful language learning, or a product or goal that emerges from learner exposure to certain contextual influences in language learning? There are many opinions about what autonomy is and its definitions.

The terms of self-access, self-regulation, self-direction, and self-instruction are synonymously used for autonomy. First of all, Holec’s definition of autonomy, ‘the

ability to take charge of one’s own learning’ (1980: 3) is widely used. Cotterall (1995) defines autonomy as "the extent to which learners demonstrate the ability to use a set of tactics for taking control of their learning" (p. 195). Dickinson's definition of self-instruction refers to ``situations in which learners are working without the general control of the teacher'' (1987: 11). There is broad agreement in the theoretical literature that learner autonomy grows out of the individual learner's acceptance of responsibility for his or her own learning (Benson & Voller, 1997; Little, 1991; Dickinson, 1995).

In the 1970s and 1980s, the focus on adult self-directed learning tended to be on the learning processes, which are outside the context of formal education. However, the more recent literature has begun to use the term ‘self-directed learning’ together with the concept of learner autonomy in the context of institutional education context (cited in Koçak, 2003: 14). The only distinction between autonomy and self-directed learning is clearly emphasized by Dickinson (1987) who says that in self-direction learners accept responsibility for all the decisions related to their learning but not necessarily implement those decisions; on the other hand, in autonomous learning the learners are entirely responsible for all the decisions concerned with their learning and also the

implementation of these decisions. The other term which is being used for autonomy is ‘self-access learning’. Like self-access and self-directed learning, ‘individualization’ is another concept used for autonomy. When the individualization first emerged in practice, “the learners determined their own needs and acted accordingly”. After that, it transformed into programmed individualized learning, in which the crucial choices were made by teachers instead of students themselves (Koçak, 2003: 15-16). Moreover, Hurd (2005: 14) makes the division of the terms self-regulation, self-direction and autonomy as (they) are often used synonymously in the literature, and while this does not necessarily lead to confusion, a useful distinction might be to interpret being autonomous as an attribute of the learner, self-direction as a mode of learning and self-regulation (a term borrowed from cognitive psychology) as the practical steps taken by learners to manage their own learning.

As it can clearly be seen above, there are widespread misconceptions about what autonomy is. Therefore, Little has stated on what autonomy is not:

1. Autonomy is not a synonym for self- instruction; in other words, autonomy is not limited to learning without a teacher.

2. In the classroom context, autonomy does not entail giving up responsibility on the part of teacher; it is not a matter of letting the learners get on with things as best they can.

3. Autonomy is not something that teachers do to learners; that is, it is not another teaching method.

4. Autonomy is not a single, easily described behaviour

5. Autonomy is not a steady state achieved by learners once (1991: 3-4).

Consequently, Eneau and Develotte confirm that “contrary to popular belief, a learner’s autonomy does not grow out of isolation – to be autonomous is not to be self-sufficient; rather it goes hand in hand with the development of meta-skills’’(2012: 5).

In summary, autonomy is a concept that remains elusive. As cited in Hurd (2005: 3), while there are no easy answers to any of these questions, there does appear to be almost universal acceptance of the development of autonomy as an ‘important, general educational goal’ (Sinclair, 2000: 5), and that autonomy can take a variety of different forms depending on learning context and learner characteristics.