GAZİ UNIVERSITY

INSTITUTE OF EDUCATIONAL SCIENCES

DEPARTMENT OF FOREIGN LANGUAGE EDUCATION

IMPACT OF THE COMENIUS ASSISTANTSHIP PROGRAMME (ERASMUS INTERNSHIP PRACTICE)

ON THE PROFESSIONAL DEVELOPMENT OF ENGLISH LANGUAGE TEACHERS

DOCTORAL DISSERTATION

KEMAL BAŞCI

ENGLISH LANGUAGE TEACHING PROGRAM

ANKARA

i

COPYRIGHT AND CONSENT TO COPY THE DISSERTATION

All rights of this dissertation are reserved. It can be copied …… months after the date of delivery on the condition that reference is made to the author of the dissertation.

AUTHOR:

Name : Kemal

Surname : BAŞCI

Department : English Language Teaching

Signature :

Date of Delivery : August, 2015

DISSERTATION:

Title of the Dissertation in Turkish: Comenius Asistanlığı (Erasmus Staj) Programının, İngilizce Öğretmenlerinin Mesleki Gelişimleri Üzerindeki Etkisi

Title of the Dissertation in English: Impact of the Comenius Assistantship Programme on the Professional Development of English Language Teachers

ii

DECLARATION OF CONFORMITY

I declare that I have complied with scientific ethical principles within the process of typing the dissertation that all the citations are made in accordance with the principles of citing and that all the other sections of the study belong to me.

Name and Surname of the Author: Kemal BAŞCI

iii Juri onay sayfası

This is to certify that we have approved this dissertation entitled “Impact of the Erasmus+ Comenius Assistantship Programme on the Professional Development of English Language Teachers” and that in our opinion it is fully adequate, in scope and quality, as a

thesis for the degree of Doctorate in English Language Teaching Department of Gazi University.

Supervisor/Chairman (Prof. Dr. Abdulvahit ÇAKIR)

(ELT, Gazi University) ………

Member (Prof. Dr. Dinçay KÖKSAL)

(ELT, 18 Mart University) ………

Member (Assoc. Prof. Dr. Paşa Tevfik CEPHE)

(ELT, Gazi University) ………

Member (Asist. Prof. Dr. Necat KUMRAL)

(ELT, Police Academy) ………

Member (Assist. Prof. Dr. Cemal ÇAKIR)

(ELT, Gazi University) ………

Date of Dissertation Defense: 26/08/2015

I certify that this dissertation has complied with the requirements of degree of Doctorate of Philosophy in the subject matter of English Language Teaching.

Title Name Surname

Director of Institute of Educational Sciences

iv

ACKNOWLEDMENTS

I owe heartfelt thanks to those people without whose contributions, this study would have never come into existence. Firstly, I thank my advisor Prof. Dr. Abdulvahit ÇAKIR, for his invaluable guidance, helpful manners and sophisticated discussions on the matter. I also thank Thesis Committee Members, Assoc. Prof. Dr. Paşa Tevfik CEPHE, and Assist. Prof. Dr. Necat KUMRAL, who have always been so generous to extend their help I needed. I am grateful to Prof. Dr. İhsan ALP and Dr Ali GÖKSU, who spared a great deal of time on analysing the data and displaying the results through the graphs accordingly.

Special thanks should go to Prof. Dr. Musa YILDIZ, who motivated and encouraged me through the administrative procedures. I should thank Prof. Dr. Tahsin AKTAŞ, Assoc. Prof. Dr. İskender Hakkı SARIGÖZ, Asst. Prof. Dr. Cemal ÇAKIR, Asst. Prof. Dr. Abdullah ERTAŞ, and Prof. Dr. Dinçay KÖKSAL, who have always provided academic support to guide me all the way through the process of designing and writing the thesis. My colleagues, R. Mutlu SALMAN, M. Yaşar SOYDAŞ and Asst. Prof. Dr. İbrahim ÖZAY, deserve special thanks for their motivation and statistical help.

I should not forget to thank the Comenius Assistants who provided all the information for me to collect the data by filling out the questionnaires with due care and timely feedback. I thank and send my best wishes to my classmates many of whom are already associate professors in their departments. I have unforgettable campus memories with them.

I owe thanks to my son, Enes Kasım; my daughters, Şule and Şevval Güner; and my nephew, Adem Alper for their help with typing the texts when I felt exhausted. During those hard times, my wife, the robust figure behind the scene, providing all the logistic and provisional support for all of us, truly deserves the greatest thanks for her unyielding patience and constant support.

v

COMENIUS ASİSTANLIĞI (ERASMUS STAJ) PROGRAMININ

İNGİLİZCE ÖĞRETMENLERİNİN MESLEKİ GELİŞİMLERİ

ÜZERİNDEKİ ETKİSİ

Doktora Tezi

Kemal BAŞCI

GAZİ ÜNİVERSİTESİ EĞİTİM BİLİMLERİ ENSTİTÜSÜ

AĞUSTOS 2015

ÖZ

Avrupa Birliği’nin ortaya çıkışı ve entegrasyon sürecinde, birliğe üye ve aday ülkeler arasında gerçekleştirilen eğitim ve kültür programları, söz konusu ülkelerde yaşayan insanlar arasında kaçınılmaz bir yakınlaşmayı ve etkileşmeyi beraberinde getirmiştir. Bu etkileşim ortak bir anlaşma dili doğurmuştur. Kullanılan dil ne olursa olsun, insanlar birbirlerini tanımanın, anlaşmanın ve dostluklar kurmanın bir yolunu bulmaktadır. Bu sürecin hızlanmasında Avrupa Birliği Eğitim ve Gençlik Programlarına başvuru yaparak katılım hakkı kazananlar arasında bulunan eğitimciler çok büyük pay sahibidir. Bunların başında da öğretmenler ve öğretmen adayları, yani program tabiriyle “Comenius Asistanları” gelmektedir. Comenius Asistanları hiç de azımsanamayacak bir süre için— asgari 13, azami 45 hafta— bu faaliyeti gerçekleştirmekte ve oldukça verimli bir süreç yaşamaktadır. Asistanlık faaliyetinin kişisel gelişimlerine olduğu kadar mesleki deneyim ve gelişimlerine de büyük katkı yaptığı düşünülmektedir. Bu araştırmanın amacı bu katkının boyutlarını ölçmektir. Bunun için bir anket geliştirilmiş ve asistanlara faaliyetin başında verilmiştir. Katılımcılara asistanlık faaliyeti öncesindeki beklentileri ve planları sorulmakta ve bu deneyime hazırlık durumları ölçülmektedir. 10 maddeden oluşan anket soruları, içerikleri çok fazla değiştirilmeden ancak asistanlık sonrası gerçekleşen durumu ölçmeye dönük olarak güncellenip tekrar verilmiştir. İki anket arasındaki benzerlik ve farklılıklar asistanlık faaliyetinin asistana/öğretmen adayına kazandırdıklarını, mesleki ve kişisel anlamda kendilerine yapmış olduğu katkıyı, yani asistanlık deneyiminin etkisini ortaya çıkarmakta yardımcı olacaktır. İkinci anketin sonuna bir de açık uçlu soru eklenmiş ve asistanlardan genel düşünce ve duygularını asistanlık programının güçlü ve zayıf yanlarını paragraf halinde yazmaları istenmiştir. Faaliyeti tamamlayan yararlanıcıların nihai raporlarının taranması ve kendileriyle yapılan yüz yüze görüşmelerden elde edilen bulgular da tez içeriğinin zenginleşmesine katkı sağlamıştır. Yukarıda belirtilen veri toplama araçları araştırmacının topladığı verilerden elde ettiği analizlerin tutarlı olmasını

vi

ve programın asistan öğretmenlerin mesleki gelişimi üzerindeki olumlu etkisine güçlü bir yorumlama ile ulaşmasını sağlayacak sonuçlarla desteklenerek tasarlanmıştır. Sonuçların karşılaştırılması araştırmacılara bu çalışmadan elde edilen bulguların yanısıra çalışmanın çıktıları kapsamında belirli bir sonuca ulaşmak için ihtiyaç duyulan istatiksel olarak anlamlı verileri elde etme imkanı sağlayacaktır. Araştırmaya katılan Comenius Asistanları, ucu açık sorular aracılığıyla programın güçlü yönleri ile temel sorunlarına ilişkin kişisel görüşlerini ifade etme ve genel değerlendirme yapma fırsatına sahip olmuşlardır.

Bilim Kodu :

Anahtar Kelimeler : Comenius Asistanlığı Programı, Mesleki ve Kişisel Gelişim, İngilizce Öğretmenliği, Erasmus +

Sayfa Sayısı :

vii

IMPACT OF THE COMENIUS ASSISTANTSHIP PROGRAMME

(ERASMUS INTERNSHIP PRACTICE)

ON THE PROFESSIONAL DEVELOPMENT OF ENGLISH

LANGUAGE TEACHERS

A PhD Dissertation

Kemal BAŞCI

GAZI UNIVERSITY

INSTITUTE OF EDUCATIONAL SCIENCES

DEPARTMENT OF ENGLISH LANGUAGE TEACHING

August 2015

ABSTRACT

This study has been designed to research into the impact of Comenius Assistantship /Erasmus Internship Programme on the professional development of the English Language Teachers. The programme concerned has been designed and developed in order to meet the needs of the member countries for a thorough understanding of communication and interaction within the union. This inevitable commitment required the Union to expand the scope and the quality of the educational and cultural exchange programmes to contribute more to the development of social, economic and political bonds within the boundaries of the union for creating a more promising future. While practicing the language they speak, the future English Language Teachers improve their world knowledge and develop a unique social identity, which becomes part of the whole learning experience in their host countries. This added bonus of the scholarship—an opportunity to improve their language learning and teaching skills in an international setting and become more conscious of their existence as a unique member of a greater community—helps develop an awareness of life from a broader perspective and create a new concept of constant professional development. The assumption behind the thesis of the dissertation is that once they have become more

viii

conscious of their own learning, they will be able to increase pedagogical effectiveness of their teaching. The social aspect of their learning experience urges them to understand their mutual commitment to their profession, and they believe that they can develop their competence in their field of study and perform their duties better if they collaborate with their peers, trainers and mentor teachers. CA programme provides enough time and opportunity for them to enjoy it to the fullest extent considering professional and personal benefits, as the programme lasts 13-45 weeks depending on the requirements and expectations of their host country. This comprehensive study, therefore, probes deeper into their professional and personal goals they have set prior to their departure and to what extent they have achieved them during the tenure of their scholarship by means of two questionnaires designed to double check their willingness to learn and the results of their efforts. The above mentioned data collection tools have been designed in such a way that they back up their results in order for the researcher to come up with consistent analyses of the data collected and to reach a sound interpretation as to the positive impact of the programme on the professional development of the assistant teachers. The comparison of the results will provide the researchers with the statistically significant data needed to arrive at a particular conclusion regarding the outcome of the study along with the research findings. Through the open-ended type questions they are provided with the opportunity to express their personal views and general assessment of the programme with specific reference to its strong side and major drawbacks respectively.

Scientific Code :

Key Words : Comenius Assistantship Programme, Professional and Personal Development, English Language Teaching, Erasmus +

Number of Pages :

ix

CONTENTS

Öz ... v

Abstract ... vii

Contents ... ix

List of Tables ... xii

List of Figures ... xiii

List of Abbreviations ... xiv

CHAPTER 1 ... 1

INTRODUCTION ... 1

1.0. Introduction ... 1

1.1. Statement of the Problem ... 3

1.2. Aim of the Study ... 3

1.3. Significance of the Study ... 3

1.4. Assumptions of the Study ... 4

1.5. Research Questions ... 4

1.6. Scope and Limitations of the Study ... 5

1.7. Abbreviations and Acronyms Used in the Study ... 5

CHAPTER 2 ... 7

LITERATURE REVIEW ... 7

2.0 Introduction ... 7

2.1. Language Teacher Professionalism and Professional Development (PD) 8 2.2. Models of Teacher Development... 11

2.3. Professional Development for Language Teacher Educators ... 12

2.3.1. The Emergence of Trainer Development ... 12

x

2.3.3. Personal Practical Knowledge in L2 ... 13

2.3.4. Language Teacher Cognition ... 14

2.3.5. Teacher Identity ... 15

2.3.6. The Novice Teacher Experience ... 15

2.4. Teaching Expertise: Approaches, Perspectives and Characterizations .. 17

2.5. Collaborative Teacher Development ... 18

2. 6. Current Practices in Teacher Training and Development ... 20

2.6.1. The Practicum ... 21

2.6.2. Teaching a Class ... 22

2.6.3. Self-Observation ... 23

2.6.4. Observation of Other Teachers ... 23

2.6.5. Mentoring ... 24

2.6.6. Language Teacher Supervision ... 25

2.6.7. School-Based Experience ... 26

2.7. L2 Teacher Development Through Research and Practice ... 27

2.7.1. L2 Classroom Research ... 27

2.7.2. Action Research in L2 Teacher Training ... 28

2.7.3. Reflective Practice ... 29 2.8. Conclusion ... 32

CHAPTER 3 ... 34

METHODOLOGY ... 34

3.0 Introduction ... 34 3.1 Research Model ... 343.2 Scope of the Research ... 36

3.3 Instrument ... 37

3.3 Collection of the Data ... 37

3.4 Analysis of the Data ... 38

CHAPTER 4 ... 40

PRESENTATION AND ANALYSIS OF THE DATA ... 40

xi

4.1. Presentation and analysis of the data ... 40

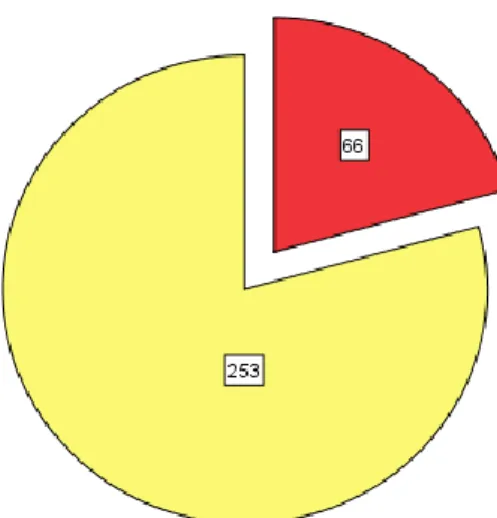

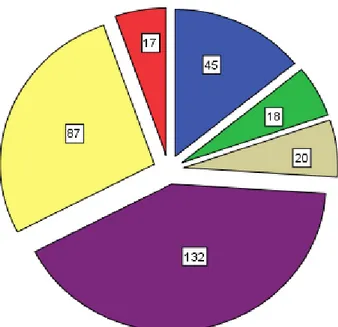

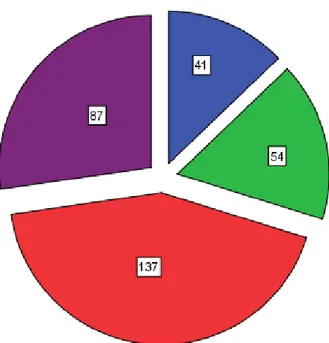

4.1.1. Gender Distribution of the Participants. ... 40

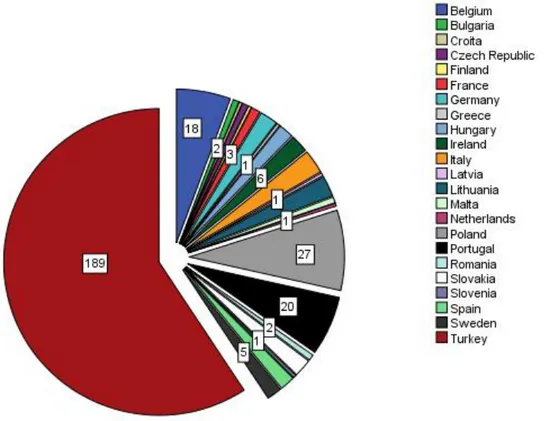

4.1.2. Nationality Distribution of the Participants. ... 41

4.1.3. Education Level of the Participants. ... 42

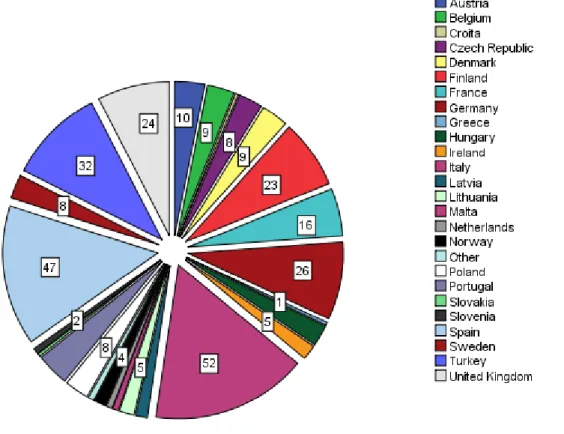

4.1.4. Distribution of the Host Countries ... 43

4.1.5. Distribution of the School Types in Host Countries ... 44

4.1.6. Length of Stay in Host Countries. ... 46

4.1.7. Distribution of the Location ... 46

4.2. Analysis of the Questions ... 47

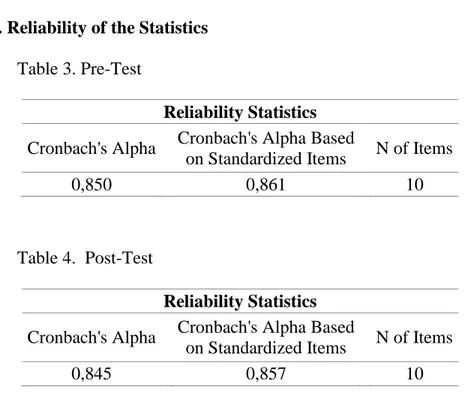

4.3. Reliability of the Research... 50

4.3.1. Reliability of the Statistics ... 51

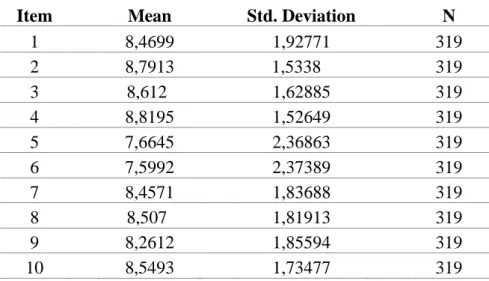

4.3.2. Summary of Item Statistics ... 54

4.4. Observed Differences in the Realized Expectations Depending on the Level of Education ... 56

4.5. Qualitative Analysis of the Impact of the CA Programme on the Professional Development ... 63

CHAPTER 5 ... 72

CONCLUSION AND SUGGESTIONS ... 72

5.0. Summary of the Study ... 72

5.1. Conclusion of the Analyses ... 72

5.2. Outcomes of Comenius Assistantships and Satisfaction of the Participants ... 73

5.3. Implications for Further Research ... 76

REFERENCES ... 79

xii

LIST OF TABLES

Table 1. Results of Paired Sample t-test ... 48

Table 2. Results of Paired Sample t-test on the items ... 49

Table 3. Pre- Tests ... 51

Table 4. Post- Tests ... 51

Table 5. Cronbach Alpha scale ... 52

Table 6. Item Statistics ... 52

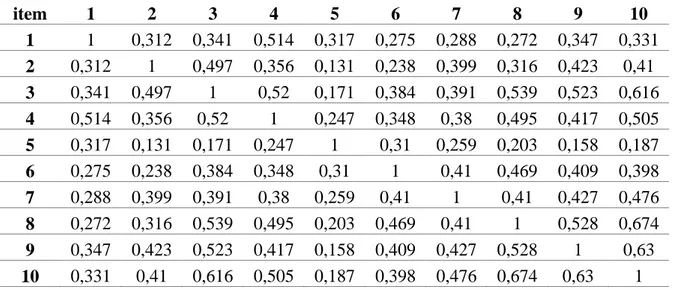

Table 7. Inter-item Correlation Matrix ... 53

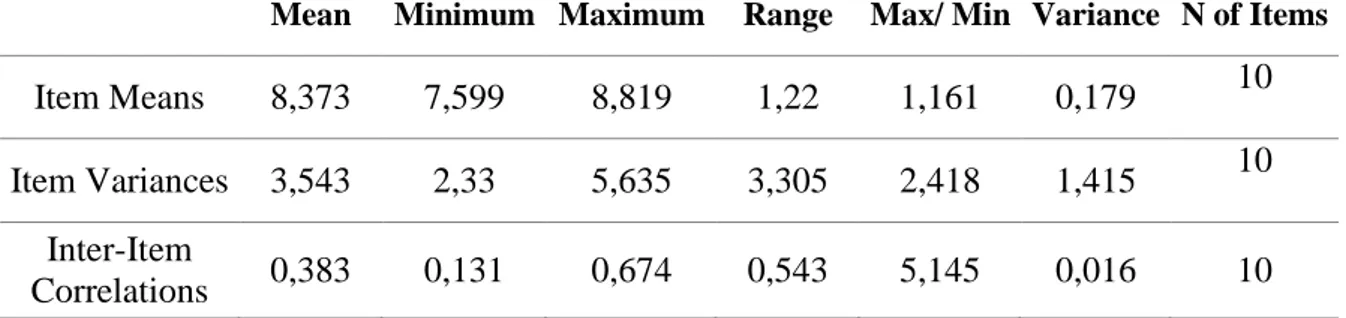

Table 8. Summary of Item Statistics ... 54

Table 9. Item-Total Statistics ... 55

Table 10. Gender ... 57

Table 11. Nationality (Home Country) ... 58

Table 12. Education ... 59

Table 13. Distribution of Host Countries ... 60

Table 14. School Types ... 61

Table 15. Location of Host Schools ... 61

xiii

LIST OF FIGURES

Figure 1. Teacher development progress ... 09

Figure 2. Gender distribution of the participants ... 41

Figure 3. Nationality distribution of the participants ... 42

Figure 4. Education level of the participants ... 43

Figure 5. Distribution of the host countries ... 44

Figure 6. Distribution of the school types in host countries ... .45

Figure 7. Length of stay in host countries... 46

xiv

LIST OF ABBREVIATIONS

CAp Comenius Assistantship CAt Comenius Assistant

CAP Comenius Assistantship Programme EU European Union

EC European Commission ELT English Language Teaching NA National Agency

ELT English Language Teacher/Teaching CTD Collaborative Teacher Development AR Action Research

PD Professional Development PPK Personal Practical Knowledge

TEFL Teaching English as a Foreign Language CLT Communicative Language Teaching

CLIL Content and Language Integrated Learning LTE Language Teacher Educators

CALL Computer Assisted Language Learning

TESOL Teaching English to Speakers of Other Languages NQT Newly Qualified Teacher

1

CHAPTER I

INTRODUCTION

1.0. Introduction

Comenius Assistantship is an action conducted under the Lifelong Learning Programme run by the European Union Educational Committee. In Turkey, the Centre for the European Union and Educational Programmes administers the Programme and the related activities. Comenius Assistants are prospective teachers who are in their 3rd or 4th year of the undergraduate programmes of their home universities. They may also be graduates of these programmes, but have not started teaching officially yet.

The aim of the Comenius Assistantship Activity is to give prospective teachers an opportunity to gain a better understanding of the European ways of teaching and learning, to enhance their knowledge of foreign languages, and to have a better insight into their education systems and of improving their teaching skills. They are supposed to improve the European dimension across the curriculum and conduct classes in their native language.

In Turkey, Comenius Assistants are selected from among the graduates of education faculties or from among those who are conferred upon certificates for their merit in teaching their major courses upon successful completion of teacher training programmes designed and offered by the departments concerned. Once selected as CAs, they are appointed to work with the Host Schools operating in EU countries designated on the mutual agreement between the parties involved. Comenius Assistantship is significant for the future career of the young assistant teachers. Maggioli in Richards and Farrell (2005) states that “true impact of professional development comes about when efforts are sustained over time, and when support structures exist that allow participants to receive modeling and advice from more experienced peers” (Richards and Farrell 2005, p.20).

2

Since 2007, the Comenius Programme, which includes the Comenius Assistantship Activity, has formed part of the Lifelong Learning Programme. It addresses school education and targets practically everyone involved in this: pupils, future teachers, teachers, schools, teacher education institutes, universities, local and regional authorities in school education, parents associations, NGOs, etc. The Comenius Programme aims to boost knowledge and understanding among young people and educational staff of the value and diversity of European cultures and languages and help young people acquire the basic life skills necessary for personal development, future employment and active European citizenship. Both aims are well reflected in the Comenius Assistantships action, which aims to:

- give future teachers the opportunity to expand their understanding of teaching and learning to a European level, enhance their knowledge of foreign languages, other European countries and their education systems and improve their teaching skills;

- improve the language skills of pupils at the host schools and increase both their motivation to learn languages and their interest in the assistant’s country and culture.

Comenius assistants spend between three and ten months (limited to eight months by Turkish NA) in pre-primary, primary or secondary schools in another country participating in the Lifelong Learning Programme. They often help teach foreign languages or use a foreign language to teach and work with pupils. They receive a grant for subsistence and travel expenses. It also covers travel costs to attend an induction meeting in the host country, and if needed to finance linguistic as well as pedagogical preparation in ‘Content and Language Integrated Learning’ (CLIL).

Previous experiences have shown that Comenius Assistantship has great potential to introduce the European dimension to the school, improve the quality of language teaching and increase the variety of languages being taught at all levels. Comenius Assistantship is enriching for both the host school and the Comenius Assistant. With almost 1500 assistants working in schools all over Europe, up to 300000 pupils benefit from the scheme every year. The vast majority of individual Comenius Assistantships were a great success. This is thanks to the efforts of all concerned. Each assistantship is different. For example, assistants teaching their mother tongue in a school where it is not on the curriculum and

3

where every learner is a beginner face a different challenge from assistants teaching pupils who have been learning a language for some time and who may be studying for public examinations at fairly advanced levels. But whatever the situation, assistants and host schools who invest hard work and imagination almost invariably find the experience of taking part in Comenius Assistantship immensely rewarding (Guide for Comenius Assistantship 2007-2013).

1.1. Statement of the Problem

Comenius Assistantship Programme (CAP) is a big project which has been continuing for a long time; however, a comprehensive study on the impact of the programme has not been carried out so far. By doing this research the researcher aims to measure the impact of the Comenius Assistantship experience on the professional development of the Comenius Assistants. We do not know exactly to what extent it affects their professional development, and what kind of expectations they have prior to the commencement of the programme. Neither do we know whether they achieve any of the goals they set before and to what extent they feel satisfied with their professional development in terms of their overall career goals. Sound information covering these areas is needed to evaluate the programme in terms of its professional benefits.

1.2. Aim of the Study

The main purpose of this study is to investigate the impact of the Comenius Assistantship experience on the prospective language teachers’ professional development. Through the data collection tool, it is intended to explore to what extent the prospective language teachers have achieved their goals they set prior to their tenure of the grant as Comenius Assistants in their respective host countries.

1.3. Significance of the Study

This study is significant as prospective English teachers’ first-hand knowledge on teaching will be of great source to the prospective CA candidates for it will be a true guide for them to make optimum use of their time and energy once they start their assistantship in their

4

host country. The findings of the research will help enhance efficiency of the programme and guide the prospective assistants all the way through their tenure of the scholarship. The overall evaluation of the programme in terms of the performance of the assistants will definitely contribute to the professional development of the prospective teachers, which will in turn promote the effective foreign language teaching in Turkey. If these programmes are considered with due care and effort, and if they are to reflect the overall success of the language teaching programmes in the ELT departments of universities, the findings can contribute to the betterment of the foreign language teacher training.

1.4. Assumptions of the study

As this research aims to explore to what extent the prospective language teachers have achieved their career goals they set prior to the commencement of the programme, the research will mainly focus on their expectations before they start teaching and their specific achievement of their goals based on their real-life experience and their performance throughout the tenure of their assistantship.

The researcher assumes that the Comenius Assistants have willingness to;

improve the knowledge of foreign language they speak by participating the programme.

develop professional teaching skills in their host schools.

know about the European countries and their cultures, and people.

expand their understanding of teaching and learning skills through constant use of English as a medium of instruction.

learn the language spoken in the host country.

1.5. Research Questions

In order to make a base for the study, the researcher developed the following questions:

What are the prospective English teachers’ expectations prior to their teaching experience as Comenius Assistants in their host country?

Do they have any career/professional goals they set for themselves prior to their teaching responsibility?

5

Which of the expectations do they feel (that) they have achieved?

To what extent have they reached their goals?

In what areas have they felt frustrated?

In what ways would they ever repair their drawbacks if they feel they performed poorly?

Would they ever think that the programme coordinators should change their selection policy and the criteria they currently seek during the screening process?

Are there any major drawbacks of the assistantship programme in general? If yes, what would the programme coordinators offer to make it a more rewarding experience on their part?

To what extent do they think that their assistantship experience can add up to their teaching career in Turkey?

What can the CAs suggest for the betterment of the CA programme?

1.6. Scope and Limitations of the Study

CAP is implemented across Europe covering 28 member countries, 3 EEA countries and several candidate countries. We could have asked all of these countries to provide feedback but it was beyond the scope of our study. Therefore, we have limited our study to the countries shown in figure 4.1.2. (p. 41). The research is also limited in that the feedback comes from the assistants who have never had any teaching experience before, and those who have never been abroad as teachers of English. The whole research is conducted in the field of ELT and the research questionnaires are administered to the assistants who are going to be teachers of English.

The survey is also limited to ELT assistants. German or French Language Assistants are excluded as the scope of the research is far beyond the capacity of the researcher to handle and cope with the challenges of such a complex and complicated academic task all the way through the research period.

1.7. Abbreviations and Acronyms Used in the Study

There will be some acronyms and terms defined as follows: CA stands for Comenius Assistants, and the programme is referred to as Comenius Assistantship Program offered

6

by EU, European Union, council of Education. The grant is conferred upon the assistants depending on the duration of the programme they will follow in their host country. These CAs are likely to work as teachers of English once they are back in their home country. Their host country is where they will work as CAs, whereas their home country, as is clear from the definition, is where they return upon their completion of the programme. The tenure of the grant simply means the duration of the programme supported financially by the amount of the grant allocated for the expenses on weekly basis. All the Acronyms used in the study are given below:

CAt: stands for Comenius Assistant, CAp stands for Comenius Assistantship Programme is referred to as Comenius Assistantship Programme, LLP Lifelong Learning Programme, EU: European Union, EEA: European Economic Area, Grant: is the money conferred upon the assistants depending on the duration of the activity. Home Country: is the place where they were living before they start practicing the programme, where they return upon their completion of the programme. Host Country: is the place where they work as CAs, Tenure of the grant simply means the duration of the programme supported financially by the amount of the grant allocated for the expenses on weekly basis. NA: represents National Agency, ELT: English Language Teacher/Teaching. CT: Collaborative Teacher Development. AR: Action Research P: Participant PD: Professional Development PPK: Personal Practical Knowledge TEFL: Teaching English as a Foreign Language CLT: Communicative Language Teaching, CLIL: Content and Language Integrated Learning, LTE: Language Teacher Educators, CALL: Computer Assisted Language Learning, TESOL: Teaching English to Speakers of Other Languages , NQT: Newly Qualified Teacher, AMEP: Australia’s Adult Migrant English Programme

7

CHAPTER 2

LITERATURE REVIEW

2.0. Introduction

Teachers’ professional development is an incessant learning process in their career. A dynamic learning process requires the teacher to be open to all sorts of progress, not only professional but also personal, social, individual and the like. Unless they have something more to learn and teach for the next day, teachers will not be able to add something to their expertise. Therefore, change is an indispensable part of life, and professional development is a life-long learning process. As professional goal setters, teachers should seek every opportunity to benefit from any professional activity organized by educational institutions or governmental / non-governmental agencies.

Comenius Assistantship is an activity under the Lifelong Learning Program (LLP). The main objectives of the CA are firstly to provide prospective teachers and the already practicing ones with the opportunity to acquire a better understanding of the European dimension of teaching and learning, to enhance their knowledge of foreign languages, and also that of other European countries and their education systems and to improve their teaching skills. Secondly, the assistantships help contribute to the improvement of the language skills of the pupils at the host schools and increase both their motivation to learn languages and their interest in the assistant’s home country and culture. Another key aspect of the CAts is their potential to introduce or reinforce a European dimension into the host schools and their local community. Assistants are expected to raise learners’ awareness of different European cultures and help overcome prejudice they might have developed over the years. The duration of assistantships supported by the European Commission is between three and ten months and a grant is awarded to cover travel and subsistence expenses and participation at a preparatory level, i.e. pedagogic, linguistic and cultural

8 preparation (Comenius Report, p.2).

Comenius Assistants may experience a cultural shock when they first arrive at their host countries. Their relationship with their mentors, school staff, neighbors, and students all affect their psychology while they strive to get used to the new place and ways of living in an area they have never been before. They will come across a different environment with different understandings of life and living conditions, not to mention the already established attitude towards foreigners, educational approaches, teaching strategies and styles other than those they have been used to. This program is intended to help expand their professional experience and develop a social identity through socio-cultural orientation of the program. This will ensure the participant to develop a sense of being an effective teacher who believes that learning to become an effective teacher is a lifelong learning experience. Learning to teach better is the idea behind this programme because novice teachers have the opportunity to understand how to become a better learner in order to teach better. Stephens and Crawley (1994) refer to this learning experience by foregrounding what they mean by the whole process, as “being an effective teacher means being able to get the best out of your students, measured in terms of your educational, psychological and social outcomes. To put this in simple terms, if your teaching and your interactive style contributes to improvement on those three important fronts, you are doing your job well” (p.2).

2.1. Language Teacher Professionalism and Professional Development (PD)

Professional development is one aspect of lifelong learning and teachers should understand the need to continually learn, whether this is done formally or informally. Nicholls (2001) defines professional development as “the enhancement of knowledge, skills and understanding of individuals or groups in learning contexts that maybe identified by themselves or their institutions” (p. 371). Professional development of teachers would include a broad range of activities that are designed to contribute to the learning of teachers, who have completed their initial training (Craft, 1996) and who have to make a continuous and determined effort in order to become and remain a knowledgeable, skillful and efficient teacher. Such teachers, who undergo meaningful professional development experiences, are better prepared to make the most effective curriculum and instructional decisions (Burns & Richards, 2009).

9

Development is a natural and gradual process, thus it is inevitable and part of the well-grounded school curriculum since it should include teacher learning component. Why do we need teacher development? Who is responsible for teacher development? How do teachers develop? These are some of the questions to be answered for a comprehensive development. According to Freeman (1998), the descriptive model of teaching consists of four areas where teachers are required to develop their professional capacity by considering all the necessary features of effective teachers as in the following:

Skills – you learn to do something, for example to give instructions more clearly.

Knowledge – you learn about something, for example how the sounds of English are produced

Awareness – you learn how to use your eyes and ears better to find out what happens when you teach

Attitude – you learn about your assumptions about teaching, learning yourself, your learners, your culture.

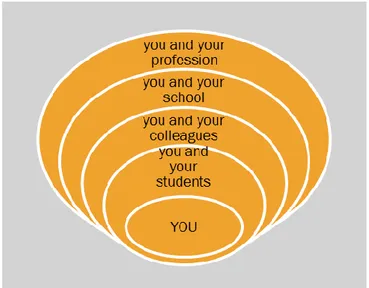

Your own development as a teacher is about how you grow and change in all of these four areas. The following figure illustrates five circles of professional development in sequence.

Figure 1. Teacher development progress (Freeman, 1998)

Other researchers have proposed models and mechanisms for supporting teachers’ awareness of their own professional development within the environment of their own classrooms. The model Freeman and Johnson (1998) proposed regarding teacher development includes knowledge, attitude, skills, and awareness, with awareness being “a

10

superordinate constituent, which plays a fundamental role in how the teacher makes use of the other three constituents (attitude, skills, and knowledge)” (p. 35). Allwright (2003), however, explains his own model as an inquiry-based approach to professional development designed to deepen teachers’ understandings of ‘life in the language classroom’ (p. 114). Such awareness, both authors argue, is critical to supporting and enhancing teacher professional development over the span of their careers. The question raised in that study is: what are the processes that teachers go through to become consciously aware of these changes? And to what extent does such awareness enhance their professional development? Professional development through cognitive, emotional, and collegial awareness is what Sakamoto (2011) proposes and focuses on. To elaborate on what they propose concerning the professional development model Banfi (1997) gives an example he encountered in Argentina as follows:

Despite the fact that the vast majority of certified English language teachers in Argentina, graduated from Teachers’ Training Colleges or Profesorados, have achieved a level of skills and knowledge about their teaching profession that turns them into initially competent professionals, we agree that “professional certification is only the starting point on the way towards professional competence. Within this perspective, professional competence is a constantly moving target, and professional development comprises those activities in which professionals are engaged for the purpose of achieving professional competence” (p. 15).

Nunan and Lamb (1996) call the experience-building process as “the effective management of teaching and learning processes in second and foreign language classrooms”. In other words, the competent teacher is the one who creates “a positive pedagogical environment” in the classroom and is able to make professional decisions “to ensure that learning takes place effectively” (Nunan & Lamb, 1996, p. 1) Professional development is perceived as a variety of activities in which teachers are involved to be able to improve their practice. Special stress is laid on teaching experience and expertise, on the convenience of attending seminars and conferences and on subscribing to professional journals and publications. Other important issues to be taken into account are individual or group reflection and interaction with colleagues.

From a humanistic and psychological point of view, Underhill (1991) defines teacher development as “one version of personal development” as a teacher. He sees “the process

11

of development as the process of increasing our conscious choices about the way we think, feel and behave as a teacher. It is about the inner world of responses that we make to the outer world of the classroom. Development is seen as a process of becoming increasingly aware of the quality of the learning atmosphere we create, and as a result of becoming more able to make creative moment by moment choices about how we are affecting our learners through our personal behaviour” (p. 37).

2.2. Models of Teacher Development

There are three main models as described in Wallace (1993), namely: the Craft Model, the Applied Science Model and the Reflective Model. We stand by this last model in our study since we believe that reflection guides future action. This model is briefly described by Ur (1999) as follows:

The trainee teaches or observes lessons, or recalls past experience; then reflects, alone or in discussion with others, in order to work out theories about teaching; then tries these out again in practice. Such a cycle aims for continuous improvement and the development of personal theories of action (p. 89).

Ur (1999) also points out that the Reflective Model can tend to over-emphasize teacher experience with a relative neglect of external input – lectures, reading, and so on – which can make a real contribution to understanding the true nature of the model. She puts a fine point on the whole matter: a fully effective Reflective Model should make room for external as well as personal input. She calls this model “enriched reflection,” as it requires a wide perspective for the content and the scope of professional development.

Farrell (1998) refers to a wide range of works as to the definitions of the term. Pennington (1992), for instance, defines reflective teaching as deliberating on experience and reflecting (mirroring) that experience on whatever they handle, while Richards (1990) sees reflection as a key component of teacher development. He says that “self-inquiry and critical thinking can help teachers move from a level where they may be guided largely by impulse, intuition, or routine, to a level where their actions are guided by reflection and critical thinking” (p.5). Richards (1990) proposes that critical reflection is a response to a past experience and involves conscious recall and examination of the experience as a basis for evaluation and decision-making and as a source for planning and action. For some authors, the broader aspect of society also plays a significant role in critical reflection.

12

Bartlett (cited in Farrell 1998) says that in order for teachers to become critically reflective, they have to transcend the technicalities of teaching and think beyond the need to improve their instructional techniques. Thus, he locates teaching in its broader social and cultural context.

Ur (1999), when talking about personal reflection, says that the first and most important basis for professional progress is simply the teacher’s own reflection on daily classroom events. But she adds that very often this reflection is quite spontaneous and informal, therefore, it is helpful only up to a certain point because it is solitary rather than organized study.

2.3. Professional Development for Language Teacher Educators

Professional development of teacher trainers is a vital aspect of language teacher education (LTE) because of teacher educator’s central role in defining and disseminating ideas about pedagogy. The work of teacher educators is relatively different from that of teachers regarding formal and/or informal professional development in that it enables them to perform their roles effectively while they continue learning (p.102).

Defining the nature of transition, Lubelska and Robins (1999) identify significant, cognitive, emotional and professional differences between teaching and teacher education. Teacher educators, they argue, need to both articulate and model their working principles. Teacher educators also need to be able to handle what they term the intentional

destabilization of teachers (p.8) and the emotional upheavals that this can cause. A further

issue regards time. The sort of transformation that is entailed by the shift may take far longer than a formal programme can achieve in its own time frame. This has implications for practice and process in formal trainer development, and for the potential role of informal professional development by language teacher educators (p.104).

2.3.1. The Emergence of Trainer Development

As we have noted, trainer development is a relatively new phenomenon in LTE, dating from the 1970s, in particular in the United Kingdom. The LTE literature dedicated solely to trainer development is thus relatively limited. Despite numerous trainer-development initiatives worldwide, few of these have been formally published for a wider audience. These accounts are characterized by a practical orientation and a relative lack of broad

13

theorization on trainer-development practices, especially in formal programmes. They reflect the emergent, practice-focused character and roots of this activity. Two overlapping periods of activity in trainer development are discernible, however, from which several themes emerge. Current practice and debate about trainer development draws heavily on these initial endeavors.

2.3.2. Early Directions: A Hands- On Approach

The concept of trainer development appears to have two main roots: one in private TEFL in the United Kingdom and the other through British aid to English Language Teaching abroad. Both were grounded in the development and spread of Communicative Language Teaching (CLT) in the period from roughly the mid-1970s to the mid-1990s. As is often put, this was an era of rapid and often radical change in English Language Teaching (ELT) particularly in ESL settings. In both cases the emergence of a group of teacher trainers, conversant in the first place with the principles and practices of CLT, was the key development in the understanding of language trainers. At first the group of teacher educators evolved from classroom practice, and often held a dual role of trainer and teacher, but later “training the trainers” started to become a planned aspect of the LTE process. This marked the beginning of trainer development (Burns & Richards, 2009).

2.3.3. Personal Practical Knowledge in L2

PPK (Personal Practical Knowledge) has recently become part of a dynamic scholarly change that has challenged the separation of knower and knowledge, experience and science, and subjectivity and objectivity in their own right. The theoretical confirmations of PPK have most commonly been identified with Dewey (1938) as he focused on the value of the experience, and the distinction of habits he placed on educative experiences. Schon’s (1983) writings on the reflective practitioner presented a discourse in which teacher educators and researchers alike could discuss the teacher as a thoughtful knower, whose knowing could be found in his or her experience, and, as Freeman and Johnson (1998) note, brought on the reflective teaching movement. Other scholars range from cultural anthropology, narrative psychology, educational philosophy, feminist theory, to postmodern theorists, challenging positivistic conceptions of knowledge, contributing to the epistemological shift in teachers’ knowledge that has transformed research and practice

14 in second language teacher education.

The impact of PPK has been notable on L2 pre-service education, L2 teachers’ professional development, and research on L2 teachers’ learning and teaching. Freeman (2002) suggests that the research on and development of the concept of PPK has led to a reassessment of the role prior knowledge in L2 teacher education, professional development and research on teachers. Language teacher educators all know that teaching is socially constructed out of the experiences and classrooms of highly effective teachers.

2.3.4. Language Teacher Cognition

The study of teacher cognition is concerned with understanding what teachers think, know, and believe. Its primary concern, therefore, lies with the invisible dimension of teaching – teachers’ mental lives, spiritual advancements and professional developments. As a tradition of research in education, the study of teacher cognition spans over 30 years (Borg 2006), and although some early work in this field actually centered on first language education (particularly reading instructions in the US), second and foreign (L2) language teacher cognition research which is what teachers and trainers focus on is a more recent phenomenon, which emerged in the mid-1990s and has grown rapidly ever since.

A key factor in the growth of teacher cognition research has been the realization that we cannot properly understand teachers and teaching without understanding their thoughts, knowledge, and beliefs that influence what they do. Similarly, in teacher education, it is firmly believed that we cannot make adequate sense of teachers’ experiences of learning to teach without examining the unobservable mental dimension of this learning process. Teacher cognition research, by providing insights into teachers’ mental lives and into the complex ways in which these relate to teachers’ classroom practices, has made a significant contribution to our understandings of the process of becoming professional practitioner endowed with constant urge to develop as a professional teacher.

A number of studies have examined the impact that pre-service teacher education has on trainees. One important issue highlighted in this work is the distinction between cognitive change and behavioral change. The study by Gutierrez Almarza (1996), for example showed that a group of trainees did adopt during their practicum the specific teaching method they were taught on their teacher education programme. This suggested that the programme had a great impact on their teaching while the interviews with the trainees

15

showed that some of them did not believe in this method and would not make use of it once the practicum was over. This finding indicated that the observed changes in these teachers’ behavior may have reflected the assessed nature of their practicum rather any deep-rooted change in their views about teaching.

2.3.5. Teacher Identity

Some researchers have conceptualized identity as a process of continual emerging and becoming professional instructor. Unitary labels are replaced by notions of progressive, dynamic, contradictory, challenging, shifting to and fro in their teaching practices, and contingent identities, or “points of temporary attachment” (Hall, 1996, p.6). The literature uses a range of diversified terminology, including social identity, ethnic identity, cultural identity, linguistic identity, socio-cultural identity, subjectivity, and the like. Although there are competing frameworks and discourses around the notion of identity (McNamara, 1997), the general move has been from psychological identity in terms of psychological processes towards contextualized social processes. Pierce (1995) provided a thorough concept of teacher identity and laid the fundamental principles, for identity is multiple and forms a site of struggle, as well as continuously changing over time for the better.

Duff and Uchida (1997) present the elements that are key to the understanding of language teacher identity defined as follows:

Language teachers and students in any setting naturally represent a wide array of social and cultural roles and identities: as teachers or students, as gendered and cultured individuals, as expatriates or nationals, as native speakers or non-native speakers, as content-area or TESL/English language specialists, as individuals with political convictions, and as members of families, organisations, and society at large (p. 451).

Also, the strategical function of discourse, in the construction of identity, has been constantly emphasized by many researchers in the field of ELT.

2.3.6. The Novice Teacher Experience

Many teacher educators, teachers, students, administrators, and even novice teachers themselves assume that once novice teachers have graduated, they will be able to apply what they have learned in teacher-preparation programmes whenever they start teaching.

16

The transition period ranging from the teacher education programme to the first year of teaching has been characterized as “a type of reality shock” since they may experience some sort of discrepancy between theory and practice (Veenman, 1984, p. 143). This is due to the ideals they have already formed during the teacher education programme, and they see why and how these ideals are replaced by the realities of the social and political contexts of the school. The fact is that what they have been preached cannot work well in practice. One reason may be that teacher education programmes are designed considering the environments teachers find themselves in when they start teaching in existing language teaching settings. Quite many novice teachers, therefore, are all alone coping with the unexpected problems likely to arise day in their own sort of “sink-or-swim” situations (Varah, Theune & Parker, 1986, p.182).

Novice teachers can also be called newly qualified teachers (NQTs), as they have completed their teacher-training programmes including the practicum) and started teaching in an educational institution. As is often stated, these novice are still involved in the process of learning something to teach better, as Doyle (1977) puts it, “learning the texture of the classroom and the sets of behaviours congruent with the environmental demands of that setting” (p.31). In their first year of teaching, they are usually face to face with three major types of influence: their schooling experiences, the teacher-education, and their newly encountered socialization experiences in their educational and cultural setting. Their schooling experiences include all levels of their education, from kindergarten to university, and involve “apprenticeship of observation” as Lortie (1975) defined concept. The nature, content, length, and philosophical and theoretical principles of their language teacher preparation programme will also impact on early teaching. Teacher socialization is “the process by which an individual becomes as participating member of the society of teachers” (Bliss & Reck 1991, p. 6). It includes how novice teachers are guided through collegial support they are always willing to receive. Mentoring is the process that novice teachers are expected to go through enabling them to adjust well to the job of teaching. Mentoring is defined as a period of professional training where “a knowledgeable person aids a less knowledgeable person” (Eisenman & Thornton, 1999, p. 81).

Novice language teachers learn to teach in their first year, and they develop conceptions of “self-as-teacher”. They formulate and develop a new concept of teacher identity related to institutional, personal, and professional roles they display in their career. Farrell (1999) suggests that language educators give pre-service teachers reflective assignments to assist

17

them as to how to unlock and articulate prior beliefs about language learning and teaching, which has got to do with “apprenticeship of observation”. In this way, novice L2 teachers can be more aware of their underlying beliefs and approaches to learning and teaching that they adopt gradually as they work.

According to the research done on the novice teachers, reasons for the problems occurred in classroom management are found as follows: limited procedural knowledge, knowledge of students, different expectations between teachers and students about what to learn. Classroom management techniques, maintenance of discipline, and how to meet the needs of different types of students are the main issues to be dealt with in the process of mentoring. Mentors appointed by the school and teacher educator mentors can collaborate in helping the novice teacher about what to teach and how to teach it in a classroom setting (Farrell in Burns & Richards, 2009).

2.4. Teaching Expertise: Approaches, Perspectives and Characterizations

There have been studies on expertise in teaching since the 1980s. These studies were inspired by some other investigations of expertise in other fields of study. They have been used to understand how the special form of knowledge can be formed by teachers. The need to demonstrate how experts use knowledge in teaching process skills that are as complex and sophisticated as they are in other professions (Berliner, 1994). As in other domains of learning, such as chess playing and problem solving in physics, much of the early work on teaching expertise was carried out in the form of novice-expert comparisons. Adopting an information-processing approach, these studies examined teachers’ cognitive process in pedagogical decision making. A number of studies were conducted in the form of comparing expert and novice teachers. Most of them adopted an information-processing model of the mind and investigated teachers’ cognitive process in the interactive and pre- and – post-active phases of expertise in other domains, mostly the work of Dreyfus and Dreyfus (1986), which has given so far the most comprehensive account of the characteristics of the different stages of expertise. First, expert teachers, if they are truly independent in their researches, are able to exercise autonomy in decision making, whereas novice teachers follow procedures, rules, and curriculum guidelines with regard to the specific contexts in which they operate. Expert teachers tend to take responsibility for their decisions (Borko & Livingstone, 1989). Second, expert teachers respond in a very flexible

18

way to contextual variations, student responses, disruptions, and available resources. They are able to understand difficulties, and they have their own plans to deal with them. Novice teachers do not anticipate problems, and are not as flexible as the expert teachers (Borko & Livingstone, 1989). Third, expert teachers are much more efficient in lesson planning and their lesson plans are usually brief and usually to the point. Yet, their planning thoughts are very rich, and they do not go into irrelevant details. They often rehearse their lessons mentally and consider what is likely to happen in similar lessons in their classes in order to know beforehand how they could foster their planning skills. They typically make longer-term plans on instructional objectives in accordance with the content (Sadro-Brown, 1990). By contrast; novice teachers spend a great deal of time preparing lessons, and their lesson plans are much more elaborate and detailed. Therefore, they do not tend to use their spare capacity to do longer-term planning (Borko & Livingston, 1989; Kagan & Tippins, 1992). Finally, expert teachers know how to make use of their integrated knowledge base. They relate their lessons to the entire curriculum and so as to establish coherence between lessons. Novice teachers see individual lessons as discrete units as they cannot create coherence to present what they teach in an organized curriculum. Expert teachers have the capacity and expertise to draw a bead on a wider range of knowledge domains. In particular, they have a profound knowledge of their students not only as groups but also as individuals, including their prior learning and their learning difficulties, and they have corresponding strategies to deal with them (Calderhead, 1996). They always start their lesson planning with their knowledge of the students. Novice teachers, however, tend to focus on what they want to do in the classroom, paying little attention to whether students will be able to respond positively to their teaching. Similarly, in the post-active phase, while novice teachers tend to deal with their own performance , expert teachers focus more specifically on how well they have learned and what they can do to enhance their knowledge in their field of study (Huberman, 1993).

2.5. Collaborative Teacher Development

Collaborative Teacher Development (CTD) is an increasingly common kind of teacher development found in a wide range of language teaching contexts, teaching has traditionally been an occupation pursued largely in isolation from one’s colleagues, though. Freeman (1998) called it as an “egg-box profession,” as each is carefully kept separate from the other fellow teachers. A crucial component of teacher development has

19

been to overcome this isolation with collaborative endeavors in this profession.

The practical effects of collaborative work have been impressive. However, the most significant thing in this kind of collaborative development thing lies deeper, particularly in the values that underlie collaboration as an immense source of teacher professional development. CTD reinforces the idea that teacher learning is fundamentally a social process, because teachers can learn professionally in sustained and meaningful ways when they work together. Edge (1992), for example, point out the fact that we need other people to develop professionally as we can understand and assess better our own ideas and experiences. CTD foregrounds the view that teachers individually and as a community can be regarded as “producers and also consumers of knowledge and understanding about teaching” (Freeman & Johnson, 1998; Johnston, 2003, pp. 123-126).

CTD arises from a belief that teaching can and should be a fundamentally collegial profession. Sockett (1993) argues that “collaboration and an implicit move toward a common professional community are justified morally because of its power in strengthening professional development and increasing professional dignity” (p. 25). Hargreaves (1992) foregrounds the significance of “culture of collaboration,” citing research on such cultures in which “routine help, support, trust and openness… operated almost imperceptibly on a moment-by-moment, day-by-day basis” (p. 226). Thus, wiping out the negative impact of professional isolation is of benefit not just to the individual teachers concerned, but to the entire community, as students and schools gain from teachers engaging in collaborative works.

As for who is collaborating with whom, the teacher is obviously at the heart of CTD. Yet, there are many options for collaboration in educational settings. Four major possibilities are so significant to mention as follows:

First, teachers can collaborate with their fellow teachers; that is, other language teachers who are peers. This is the most balanced relationship in terms of power. Collaborations among language teachers may well focus on instructional issues such as materials design and development studies, classroom management techniques, practical classroom language use, and so on. The shared professional understandings of language teachers are likely to lead them toward certain common concerns and interests.

A second very common form of collaboration is educational research studies between teachers and university-based researchers. They also tend to be interested in

20

comprehensive studies on methodological works, since researchers often have, or have access to, greater resources (including time, a precious commodity for classroom teachers) and to have a bigger interest in theorization for its own sake. It is also the case that such relations can be more problematic in terms of power and status (Stewart, 2006).

Third, teachers can collaborate with their students, usually involving a significant power use in fascinating possibilities for learning in depth about one’s own classroom practices. There are encouraging precedents for this kind of collaboration in main stream education This concept of collaborating with students is also under by a range of important philosophical positions ranging from the notion of solidarity with students to such critical pedagogical issues referring to the empowerment of learners For this kind of collaborative studies, it is better to cite Cowie’s (2001) and several of the studies that broaden the framework of practices of language teaching and learning (Johnston in Burns & Richards, 2009).

Last, teachers can collaborate with others in teaching and learning such as administrators, supervisors, parents, materials developers, and so on. An interesting example is what Winston and Soltman (2002) did to exemplify how collaboration works. They have worked with the families of the international students that they have taught in order to understand their teaching context better. Gebhard and Oprandy (1999) go deeper into the teacher-supervisor interactions and how they can be designed and structured for the sake of teacher professional development.

2.6. Current Practices in Teacher Training and Development

As an educational term ‘Collaborative Teacher Development’ does not imply any particular methodology, framework, or theory. CTD is in fact rooted in a certain attitude implying teaching and teacher development, but it suggests something beyond any particular method. In fact, CTD can take different forms within various approaches to teacher development.

The most widely known form of professional development is action research. Action research involves teachers engaging in small scale, systematic, publicly reported research in their own classrooms and contexts. In a typical action research study they aim at changing or understanding those classrooms and contexts. Action research does not always require a research team since it can be conducted by individual teachers working on their

21

own. Yet, as Burns (1999: 13) points out, its philosophical roots are in collaborative action, and it is by its very nature collaborative. The most extensive description of collaborative action research available with regard to professional development was conducted by Burns (1999) to collect data on how to book with evidence from a large scale action research programme in Australia’s Adult Migrant English Programme (AMEP). Burns demonstrates how powerful the potential of collaborative action research is and how it promotes individual professional growth in the process of time.

2.6.1. The Practicum

The practicum has long been recognized as an important part of an English language teacher’s training, just as it is offered within an ELT, TESOL, or English Education and teacher training programmes. A practicum usually involves supervised teaching, experience with systematic classroom observation, and obtaining familiarity with a particular teaching context to contribute to the professional development of practicing teachers through in-service programmes and the training of novice teachers through pre-service programmes (Wallace, 1999). A variety of terms is used to refer to the practicum, including practice teaching, field experience, apprenticeship, practical experience, and internship. However teacher-learners’ experiences in these different types of practicum may change considerably in intensity and level of responsibility. For example, during an internship the teacher-learner might be an assistant, but in a practice teaching setting, he or she might carry a full teaching load.

However, despite the variation in terminology, the level of responsibility and the actual setting where the programme is carried out, the goals are generally much the same. As Richards and Crookes (1988) clearly state, practicum goals include providing opportunities for teacher-learners to (1) enhance practical classroom teaching experience, (2) apply theory and teaching ideas from previous course work, (3) discover more about how to teach effectively by observing experienced teachers; (4) promote lesson-planning skills, and (5) gain skills in selecting, adapting, and designing and developing original course materials. They can also include enabling teacher-learners to (6) expand awareness of how to set their own goals related to improving their teaching skills beforehand, (7) question, articulate, and reflect on their own teaching and learning philosophies, which include a mellifluent blend of assumptions, beliefs, values, educational, and life experiences; and (8)