Yayınlayan: Ankara Üniversitesi KASAUM

Adres: Kadın Sorunları Araştırma ve Uygulama Merkezi, Cebeci 06590 Ankara

Fe Dergi: Feminist Eleştiri Cilt 8, Sayı 1

Erişim bilgileri, makale sunumu ve ayrıntılar için: http://cins.ankara.edu.tr/

Familialization of women: Gender ideology in Turkey’s public service advertisements

Alparslan Nas

Çevrimiçi yayına başlama tarihi: 15 Haziran 2016

Bu makaleyi alıntılamak için Alparslan Nas, “Familialization of women: Gender ideology in Turkey’s public service advertisements” Fe Dergi 8, no. 1 (2016), 168-182.

URL: http://cins.ankara.edu.tr/15_12.pdf

Bu eser akademik faaliyetlerde ve referans verilerek kullanılabilir. Hiçbir şekilde izin alınmaksızın çoğaltılamaz.

Familialization of Women: Gender Ideology in Turkey’s Public Service Advertisements Alparslan Nas*

In Turkey, Justice and Development Party (AKP) holds a single-party government since 2002 with a conservative, pro-Islamist and anti-feminist political ideology. AKP’s authoritarian tone towards women increased particularly after 2011 when the party gained its third consecutive election victory. In this regard, the abolishment of “The Ministry of Women and Family” and instead the foundation of “The Ministry of Family and Social Policies” (MFSP) in 2011 was criticized by feminist activism, with the claim that the attempt erases the name of women from the ministry which might lead to devastating effects on the solution of women’s issues. Focussing on advertisements as ideological apparatuses, this article undertakes a critical analysis of Public Service Advertisements (PSAs) with a total number of 30 spots broadcast on TV by MFSP since 2012. Problematizing the representation of women in PSAs, this article aims to analyse the practices of women’s familialization by means of the concealment of women’s issues and legitimization of patriarchy.

Keywords: AKP, Family, Gender, Public Service Advertisements, Women in Turkey. Kadının ailevileştirilmesi: Türkiye’de kamu spotlarında toplumsal cinsiyet ideolojisi

Türkiye’de 2002 yılından günümüze dek tek başına iktidarını sürdüren AKP dönemi, toplumsal cinsiyet bağlamında muhafazakar, İslamcı veya anti-feminist olarak nitelenedirilebilecek birtakım politikaların uygulayıcısı olmuştur. Özellikle AKP’nin üçüncü seçim zaferini kazandığı 2011 yılından itibaren kadına yönelik söylemlerin otoriter tonu giderek yükselmiştir. Bu bağlamda, 2011 yılında “Kadın ve Aileden Sorumlu Devlet Bakanlığı”nın kapatılarak yerine “Aile ve Sosyal Politikalar Bakanlığı” (ASPB) kurulması feminist aktivizmin eleştiri odağı olmuş, “kadın” ifadesini bakanlıktan silen bu girişimin kadınların sorunlarının çözümünü olumsuz etkileyebileceği vurgulanmıştır. Politik alanda kadına yönelik söylemlerin bir yansıması olarak reklam olgusunu ele alan bu makale, ASPB tarafından 2012 yılından itibaren günümüze dek yayınlanan 30 adet kamu spotunu eleştirel açıdan incelemektedir. Kamu spotlarında kadının temsilini sorunsallaştıracak olan bu makale, resmi söylemin kadının sorunlarını görünmez hale getirme ve patriyarkayı meşrulaştırma suretiyle kadını ailevileştirilme pratiklerini analiz etmeyi hedeflemektedir.

Anahtar Sözcükler: Aile, AKP, Kamu Spotu, Toplumsal Cinsiyet, Türkiye’de Kadın Introduction

"Our party is a conservative democratic party. The family is important to us", told Prime Minister Recep Tayyip Erdoğan, at a press conference held on June 9, 2011 for the announcement of the newly established ministries, where he declared that “Ministry of Women and Family Affairs” was replaced by “Ministry of Family and Social Policies”, prior to the general elections that would take place on June 12, 2011 (Belge 2011). The decision was actualized despite demonstrations organized by feminists to protest the dissolution of the ministry with 3000 signatures submitted to the prime minister’s office. The newly founded ministry consisted of several departments including the General Directorates of Family and Social Services, of Children Services, of Services for Disabled and the Elderly, of Social Aid and of Veterans and Families of people got deceased while serving the Turkish State, in addition to the General Directorate of the Status of Women. Erased from the name of the Ministry, the name of women was reduced to a department under the ministry. Women’s rights activists criticized the government for removing the name of women and considering women’s position along the same lines with other disadvantaged groups in society, particularly as an element of the family. Human Rights Watch evaluated this transformation as “a big leap backwards for Turkey” in terms of attaining gender equality (Belge 2011).

Since 2012, Turkey has been ruled by the single-party AKP (Justice and Development Party) government seeking conservative, patriarchal and pro-Islamic policies. AKP’s envisioning of women has coincided with its broader envisioning of the family, which led to the assimilation of women’s issues under the general rubric of the family discourse. Accordingly, this article seeks to point out the kind of discourses on women with regard to family that has been established following the transformation of The Ministry of Family and Social Policies (MFSP). For this purpose, it analyses Public Service Advertisements (PSAs) that were prepared and broadcast by MFSP since 2012. In this regard, the analysis aims to critically negotiate the ways in which women are situated as familialized subjects by the ruling political ideology in two ways; by tending to define women in relation to the family and by disallowing the critique of patriarchy in addressing women’s problems, thus normalizing and legitimizing male hegemony.

The Ideology of Conservatism and Gender

As a political ideology, conservatism has been associated with right wing authoritarianism, with a rigid stance towards social change and cultural differences that tend to reproduce the status-quo of the hegemonic establishment of social and political dynamics (Crowson, Thoma and Hestevold 2005, 571). Political currents that are committed to status quo with ethnocentric, fundamentally religious and militaristic motives have been closely linked to conservatism (Crowson, Thoma and Hestevold 2005, 572-573). Gender, has also been considered as an important counterpart of conservative ideologies all over the world, as feminist movements have struggled with various conservative agendas across different social and political settings. Feminism and any critical approach to gendered formations of patriarchal culture have been situated contrarily to conservative ideologies within the ideological spectrum. For example, politicians in British Conservative Party have been overtly anti-feminist, and feminists in Britain were unlikely to vote for the Conservative Party, staying critical towards its gendered policies and discourses (Bryson and Heppell 2010, 31). Mainly relying on preserving the traditional family structures and the gender roles imposed on women by those structures, conservative governments in Britain refused to recognize various sets of demands made by feminists, including sexual liberties, abortion, single-mothers, affirmative actions for women’s equality in the workplace, funding for child care and the extension of maternal leave to parental leave (Bryson and Heppell 2010, 34-35). As experienced in British political and social context since the 1970s until the 2000s, conservative ideologies have been highly gendered in terms of their tendency to reproduce women’s traditional roles as mothers in a heteronormative understanding of the family, as well as normalizing their subordination in the public sphere by reducing their visibility in social and economic aspects; the attempts which systematically concealed and legitimized women’s subordination due to the imposed gender norms.

Conservative ideology has also been manifest in Turkish context particularly in relation to the mainstream right wing politics and their perceptions on gender since the 1950s (Kalaycıoğlu 2007, 233). The establishment of the secular republic in 1923 led by Mustafa Kemal Atatürk with the dissolution of the Ottoman Empire has introduced certain civil and political rights for women. Civil Code of 1926 eliminated the Islamic way of marriage and provided women with the right to divorce and receive equal inheritance, as it also ended polygamy which was ensured by the Islamic code for centuries. Moreover, in 1934 women were granted with full suffrage. During this process, women’s rights were considered as a crucial part of Turkey’s project of modernization and secularization (Müftüler-Bac 1999, 303). Although these developments were important steps for women’s liberation, the regime on the other hand stereotyped women as nurses and teachers, given the role of the mothers of the nation, which led to another form of gendered stereotyping on women. During the republican period, women were emancipated but not fully liberated; which means that women were granted with equal rights in formal terms, but there were stills cultural and social obstacles that hindered their liberation (Kandiyoti 1987).

With the end of single-party government era at 1946, political parties that managed to form coalitions or hold single-party governments such as Democrat Party in the 1950s, Justice Party in the 1960s and the 1970s, Motherland Party in the 1980s and the 1990s were representatives of conservative centre-right politics. The Islamist tone of conservative ideology in Turkey firmly increased with the emergence of the AKP in the early 2000s, as the successor of Islamist Welfare Party and Felicity Party of the 1990s. AKP’s turn to global capitalism contrary to its predecessors, which were critical of capitalism while supporting an Islamic system of economic relations, enabled the party to expand its influence on centre-right voters. The way in which AKP managed to win the traditional right wing votes in addition to its core Islamist voter segment was an important factor behind

the party’s consecutive election victories since 2002. These developments consequently resulted in the popularization of an Islamist agenda throughout the society, particularly with regard to gender. Differing from the early republican regime that aimed at women’s emancipation as a part of the country’s project of modernization and secularization, conservative ideologies linked to Islamist politics tended to confine women to their houses by strictly separating the public and private spheres (Müftüler-Bac 1999, 303). Gendered discourses posing women’s primary duty as mothers and wives under the family structure attained an increased emphasis under AKP’s conservatism, which led to women’s further pressuring by patriarchal culture and their economic underdevelopment; as Turkey has widest male-female employment gap in the world (İlkkaracan 2012, 17). The mainstreaming of political Islam during this period further resulted in the wide circulation of gendered discourses on women and family, by which conservative ideology was practiced through social, cultural and political contexts with an increasing tone in Turkey’s contemporary social landscape.

AKP’s Envisioning of Family and Women

The family has historically been considered as the foundational unit of social, cultural and economic life (Parsons and Bales 1955; Walsh 2003; Foucault 1990). The idea of “nuclear family” consisting of a pair of adults and children has critically been evaluated as a setting where capitalism and the ideological presumptions of the nation state are rooted (Carrington 2001). In the context of Turkey, the family has been instrumentalized as a significant ideological apparatus throughout AKP’s single party government since 2002. As evident in Erdoğan’s speech declaring the establishment of the MFSP replacing the Ministry of Women and Family Affairs, the family is considered as an ideal setting where conservative politics can be implemented (Çitak and Tür 2008, 463). Yalçın Akdoğan, an advisor to Erdoğan who also served as a deputy prime minister, states that the family has a great importance to conservatism and the dissolution of the family as a social institution that hinders the transmitting of tradition and social values is the most negative aspect of modern society (Çitak and Tür 2008, 463). The family according to the conservative agenda of AKP is considered as a social institution, which is threatened by the emergent trends of contemporary society, challenging the strictly established boundaries of the nuclear family. Akdoğan’s remarks can be considered in line with Turkey’s adaptation to globalization in cultural and economic aspects particularly during the AKP rule, which brings along the problematic of the family as a traditional institution that is being challenged by the transformation of the public sphere. Since 2002 when AKP came to power, the party situated itself as “conservative democrat” (Akan 2012), which seeks conservative and pro-Islamic policies in cultural sphere whereas it takes bold steps towards neoliberalism and globalization in economic aspects. Eventually, considered as under threat by recent cultural and economic transformations, the family was considered by AKP as a space of dissolution that needs to be revitalized in accordance with the party’s conservative-democratic ideology.

The post-2011 period after AKP won the elections with %49 of votes is categorized by scholars as Erdoğan’s increasing authoritarian tendencies, especially manifest in his envisioning of a conservative society such as the emphasis on raising “pious generations”, refusal of abortion, insulting expressions on alcohol drinkers and the rejection of non-familial lifestyles such as unmarried boy and girl students sharing the same houses (Özbudun 2014, 157). This period also coincides with the transformation of the Ministry of Women and Family Affairs to MFSP, which was a symbolic attempt to refer to women’s issues under the general framework of family and social policies. Since the mid-2000s, the notion of the family has occasionally been portrayed by AKP as a happy extended family where members of the family live in peace, can easily solve their problems and respect traditions (Saraçoğlu 2011, 41). This portrayal of the family was imagined as a prototype of the nation, which was considered as the big family with members sharing the same values, beliefs and behaviours (Kaya 2015, 60). The meanings attributed to the family conceived of a society as a homogeneous whole that exists in harmony without any differences and plurality. According to Bozkurt, AKP’s imagination of the nation as a big family concealed ethnic and religious conflicts such as Kurdish and Alevi problems as well as other disadvantaged groups lacking social welfare as a result of AKP’s neo-liberal rule (Bozkurt 2013, 382). AKP elite in this regard tended to implement certain policies under the name of “social policy” which were indeed reduced to “family policy” with a bold emphasis on “strengthening the family” discourse (Yazıcı 2012, 116). AKP’s “strengthening the family” discourse legitimized the state’s social power that poses itself as the sole protector of the family and becomes a disciplining force over the family as a social institution through which certain hegemonic discourses and ideological inclinations could be implemented on citizens via families (Yılmaz 2015, 375). The emphasis on familialism accompanied by AKP’s political ideology with populist, liberal and

neo-conservative elements propagated the significance of the family as the main political unit whose “interest and welfare should be prioritized and protected politically at the expense of individual citizens and their universal rights” (Yılmaz 2015, 378). The establishment of “family advice centres” and “family education programs” throughout the country under AKP rule illustrates the ways in which political webs of power is being established to function as the technologies of power attaining AKP’s grand narrative of the family.

Women occupy a central role in AKP’s envisioning of the family. The family discourse reasserts women’s traditional gender roles under patriarchal society (Yılmaz 2015, 382); therefore, prevents the politicization of issues regarding women by legitimizing male hegemony. AKP politicians uttered several statements concerning women’s role and status in society that attempted to legitimize gendered relations of power and patriarchal oppression. After the bombing of 34 Kurdish civilians by the Turkish army at Turkey’s south-eastern border called Uludere in 2011, Erdogan stated in a press conference regarding women that “Every abortion is like Uludere”. He claimed that abortion is a trap that is imposed on Turkish women by the enemies of the nation to wipe Turkey off the world stage (Vela 2012; Eslen-Ziya 2013, 865). Women’s rights activists in Turkey noticed that after such remarks, state hospitals refused to undertake abortions despite its legal status (Letsch 2015). Erdoğan further stated that men and women are not equal and “women are God’s deposits given to men”. He also accused feminists who protested his statements for acting against traditional values of motherhood, claiming “feminists does not have any understanding of being a mother.”1 Besides, Erdogan is

known for his call for women to give birth to “at least three children” and “donate them for the nation” (Daloglu 2013). Defining the role for women solely in relation to women’s perceived utility for the nation as mothers, the hegemonic political discourse introduced a pro-family politics that aimed to reassert the role of women under traditional, patriarchal gender norms (Çitak and Tür 2008; Coşar and Yeğenoğlu 2011; Unal and Cindoglu 2013). The political statements uttered during this era constitutes what Unal defines as an “antifeminist discursive regime under the AKP rule”, which brings along the rejection of the notion of gender equality (Unal 2015, 14).

Under the AKP rule, issues regarding women are mentioned in so far as they are within the context of the family or with regard to the headscarf controversy (Çavdar 2010, 344). According to the AKP program, women are important, “not because they constitute the half of the population, but because they play the primary role in raising the next generations” (Çavdar 2010, 349). Pointing at the role of women in the family, former Ministry of Women and Family Affairs Nimet Çubukçu stated that, “We attach great importance to family values and women’s position within the family. We care about women’s role as a mother” (Çavdar 2010, 349). Accordingly, the first attempt put forward by AKP was the “Ailem Türkiye” (My Family Turkey) project initiated at 2005. Organized by Ayşenur Kurtoğlu, advisor to Prime Minister Erdogan, the project aimed to create awareness towards the “importance of the family” by organizing education seminars all around the country and distributing handbooks including “Family Law Guide”, “Family Health Guide”, “A Life on the Same Pillow” and “Family Home Guide”. According to Kurtoğlu, family was their most “uncorrupted value” and that they should be jealous of the family in the way that they should protect it with great care” (Çitak and Tür 2008, 463). The second attempt regarding the family was “Aile Olmak” (Becoming a Family) project, which was announced at June 2013 by the MFSP. Prime Minister Erdogan delivered a speech at the project’s press conference, where he declared that, “Caesarean and abortion murdered our nation.” Erdogan continued as follows:

Every woman should have at least three and even four children. For long years, they deceived our families imposing caesarean and abortion on them, telling that they cannot have more than two children with caesarean. Their aim was to wipe Turkey off the stage by decreasing our population. We have to end this game. I am saying this especially to our women, mothers. As Turkish women, you are going to get rid of this game, you have to give an attitude against this.2

In the press conference, Erdoğan and Fatma Şahin, Minister of Family and Social Policies called for the “bachelors to get married as soon as they can” so that they can have the chance to form the basis of their national ambitions. A period later, attending to a marriage ceremony, Erdogan criticized women who tend to deter pregnancy and declared: “Birth control is treason.”3 Recently, Prime Minister Ahmet Davutoğlu also stated prior

to the 2015 general elections that “every bachelor should apply us, we will find you good husbands and wives if your families cannot.”4 This almost obsessive emphasis on marriage is being continuously propagated by the

ruling elite as a bio-political tool that imagines the nation as a big family on patriarchal and heteronormative basis.

Women, in this picture, are solely referred as mothers and women’s issues are considered as familial issues, without any emphasis on different forms of subordination that women encounter in Turkey. Turkey ranks 130th among 145 countries in World Economic Forum’s 2015 Gender Gap Report.5 Patriarchy is also present in

structural forms at various spheres ranging from law to economics. Turkey’s court decisions usually tend to lower perpetrator’s sentences in rape incidents, which are legitimized by courts with the claim that “the victim had consented to sex.”6 Similar cases apply to femicide convicts as a recent court decision lowered the man’s sentence by stating that the man “loved his wife too much and that is because he had to kill her.”7 The AKP era

also marks a decreasing rate of female employment in Turkey (Kaya 2015, 63; Arat 2010, 873). According to the official records, women’s participation to the work force is 27,1% as Turkey has the worst record among OECD countries.8 Eventually, the statistics show that Turkey is experiencing a state of emergency in terms of women’s

subordination that needs special and urgent attention. However, political discourses tend to legitimize the mechanisms of women’s subordination by reducing women’s issues merely to the issues regarding the family. In a similar manner, PSAs prepared and broadcast by MFSP illustrate the ways in which women’s issues are assimilated under the general rubric of the “family” discourse that tends to familialize women under the state’s patriarchal and conservative political ideology.

Public Service Advertisements

Public Service Advertisements (PSAs) are defined as “promotional materials that address problems assumed to be of general concerns to citizens at large” (O’Keefe and Raid 1990, 67). PSAs basically aim to point at certain problems regarding the public good and increase public awareness towards possible solutions by influencing behaviours, opinions and attitudes. Mostly broadcast by non-profit or governmental organizations, PSAs usually receive gratis placement in broadcast and print media (O’Keefe and Raid 1990, 67). Traditionally defined as a visual medium of non-commercial advertising serving to public interest, PSAs are also significant in conveying certain ideologies and dominant discourses to the public (O’Keefe and Raid 1990, 72; Phelan 1991). PSAs can serve to certain ideological functions that could reinforce status quo of social and political relationships, under the disguise of promoting action and change for public good (O’Keefe and Raid 1990, 72). Various scholars have pointed out that, advertisements have significant roles in the reproduction of hegemonic discourses and ideologies with regard to gender, class, ethnicity and other measures (Gill 2009; Williamson 1978; McFall 2004; Goldman 1992). Similarly, PSA is a form of advertising with similar objectives to commercial ads that try to convince the audience to conform to a set of agenda regarding social matters (Wong 2005, 59). Positioned as the communicator of public good different than commercials, PSAs can be regarded as “privileged discourses” as powerful mediums to disseminate the articulations of power relations and ideologies (Wong 2005, 59).

In Turkey, a legal directive for PSAs “Kamu Spotları Yönergesi” (Directive for Public Spots) was passed by High Council of Radio Television (RTÜK) in 2012. According to the directive, PSAs are defined as “instructive and educative films prepared by public or civil institutions and are considered by the High Council as serving to the public good.”9 The directive further remarks that PSAs accepted by the High Council are

broadcast on TV on assigned time intervals free of charge. The directive distinguishes two types of PSAs: “kamu spotları” (public spots) and “zorunlu yayın” (obligatory broadcast). Obligatory broadcast under PSAs are the films prepared by state institutions, including Ministries. The category of “public spots” consists of films that are prepared mostly by non-governmental organizations regarding social problems. In 2014, PSAs by 62 state institutions and NGOs were screened for 55.162 times on over 40 TV channels.10 In 2015, the number of

institutions broadcasting PSAs increased 83 and so far 46.251 screening have been recorded on over 40 TV channels.11 PSAs were mostly dealing with issues regarding health problems including the use of alcohol,

smoking and drugs, as well as environmental consciousness and ways of nutrition including the correct choices of food and the need for sports.

The way in which PSAs are admitted after careful investigation of the High Council introduced an ideological space of political interrogation since the members of the High Council are predominantly determined and elected by the ruling party AKP. For example, a PSA by “Filmmor”, an organization of feminist activists engaged in filmmaking, was submitted to the high council and was rejected without any comment. The PSA was an announcement of the “11th Women’s Film Festival” and included feminist criticism particularly with reference to the discussions on abortion and marital rape.12 The rejection of the PSA met with the criticism of

feminists, who claimed that the high council controlled by AKP’s openly anti-feminist ideology does not allow them to sound concerns on male hegemony. Eventually, the decisions of the High Council regarding the PSAs illustrate the ways in which certain discourses are excluded whereas others are included in the general understanding of the “public good” by dominant political ideology.

This article analyses 30 PSAs that have been broadcast since 2012 by MFSP. With an analysis of discourses that arise from the PSAs, this article will first attempt to sketch a general view on the PSAs regarding the ways in which women’s issues are assimilated within the broader discourse of the family. In so doing, the article also provides an overview of the Family Action Plan prepared by AKP that form the basis of PSAs. The article will then continue with a deeper analysis of particular PSAs dealing with the issue of violence against women, and endeavour to point out the discursive mechanisms by which the narratives of patriarchy is conveyed to the viewer in normalized and legitimized formats.

The Analysis

The Family Action Plan

MFSP broadcast its first PSA in July 2012; a year after the Ministry was transformed from the Ministry of Women and Family Affairs. So far, total of 30 videos have been uploaded to the website of the Radio and Television High Council, all of which were also screened on TV. Among these PSAs, six videos have been prepared by non-governmental organizations and were broadcast under the patronage of the Ministry, while remaining 24 videos were prepared by the Ministry. The NGOs contributing to the Ministry’s work include MIKADER (The Association of Being Hand in Hand with Little Hearts), a charity organization for abandoned children, and KADEM (Women and Democracy Association), a women’s organization that was founded in 2013 by Sümeyye Erdoğan, the daughter of the President Recep Tayyip Erdoğan. The main themes of PSA cover several issues regarding women, elderly, children, disabled, war veterans and the general notion of the family. Two campaigns have been organized that accompanied the broadcast of certain PSAs, including “Because We Are a Big Family” and “Being a Family”. “Because We Are a Big Family” campaign was later merged with “Being a Family Campaign” in 2013, together with an action plan declared by the Ministry for the years 2013-2017.13

The action-plan significantly puts forward AKP’s envisioning of society and women under the general discourse of the family. According to the plan, Turkey faces a critical stage in terms of its demographic attributes since the birth rate decreased from 2,27 to 2.09 between 2003 and 2011. Drawing attention to the recent developments in globalization, modernization and urbanization due to the increase in city populations and industrialism, the report states that, “the Turkish family structure has been affected by such changes” (2013, 1). The family, according to the action plan, is the foundational unit of Turkish nation, consisting of a man, a woman and children, and aims to reproduce the next generations of humankind (2013, 2). In this regard, the report undertakes a heteronormative stance on the understanding of the family, identifies its role solely as a tool for raising generations with employing a bio-political agenda. It also excludes other kinds of families that may be formed by individuals including same-sex marriages, couples without children and single-parents. The plan explicitly acknowledges that, “the family gains comprehensive importance when children exist” and that “despite the modernization process” family still remains as the sole factor in “sustaining the welfare and the peace of Turkish nation” (2013, 3). Besides, the plan analyses that the Turkish family recently encounters certain “risks” that include the increase in divorce rates, increase in single-parenthood, increase in the couples’ inclination not to have children, refusal of marriage or marriage at a later age (2013, 7). The plan excludes the possible other understandings of the family that individuals may pursue by labelling them as “risky” and once more underscores the “threats” that need to be tackled to re-establish the family. The narrative however does not involve a critical analysis of the gender roles within the family, and it rather contributes to its invisibility by a bold emphasis on the normatively established boundaries of the family as an ideological apparatus.

Among the aims of the action plan stressed in fourteen different articles, the emphasis is on various issues including, “encouraging families’ participation to cultural events”, “easing access for the elderly and disabled in public space”, “providing public spaces for families to socialize”, “supporting the togetherness of the families in education facilities” and to “strengthen the integration of suburban families to the urban life” (2013, 5). The action plan however, does not put any emphasis on women’s issues and different forms of subordination that needs to be tackled. Throughout the report, the only remark on equality is stressed as it is suggested that, “equality between men and women will be actualized since our family policies rely on the lifelong marriages

between men and women with togetherness” (2013, 6). Women in this sense are defined solely with their relation to the heteronormative family. The emphasis on “lifelong marriage” further tends to reproduce the power relations during the marriage since hundreds of women, who wanted to divorce, have been murdered by their husbands in recent years. The act of divorce is considered as a threat against the male-dominated power relations invested in the institution of the family. For example, after seven women who attempted to divorce were killed by their husbands during November 2015, a commission to “investigate divorce” has been founded in the parliament where AKP members stated that the family should be strengthened to prevent divorce, rather than point at the family as a space of patriarchal oppression.14 Therefore, the family is an ideal state of affairs between

women and men that needs to be accomplished according to the dominant political ideology. PSAs in this regard may be evaluated as communicators of the idealized version of the family where women are interpellated by AKP’s gender ideology.

Familialization of Women

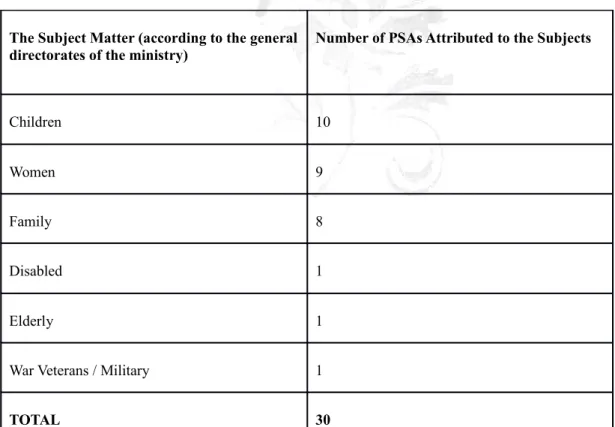

Initially total of seven PSAs were broadcast by the Ministry as a part of the “Being a Family Action Plan”. As of 2015, the number of PSAs extended to 30 different films, which also include the contributions of NGOs like MIKADER and KADEM. The subject matter of PSAs mainly include the target audience of five different directorates under the Ministry; General Directorate of the Status of Women, of Family and Social Services, of Children Services, of Services for Disabled and the Elderly, and of Veterans and Families of people got deceased while serving the Turkish state. The highest number of PSAs according to the subject matter is 10 addressing children’s issues, 9 addressing women’s issues and 8 directly addressing the notion of the family. While only 8 PSAs directly mention the significance of the family, in all PSAs the notion of the family is present as a contributing factor for different individuals to pursue a good life. Among 9 PSAs regarding women’s issues, 3 of them are prepared by KADEM, a women’s organization linked to AKP elite due to Erdogan’s daughter, Sümeyye Erdogan’s activities in the association (Table 1).

The Subject Matter (according to the general directorates of the ministry)

Number of PSAs Attributed to the Subjects

Children 10

Women 9

Family 8

Disabled 1

Elderly 1

War Veterans / Military 1

TOTAL 30

Table 1 The number of PSAs broadcast according to the subject matter. The PSAs are categorized according to the Directorates established under MFSP.

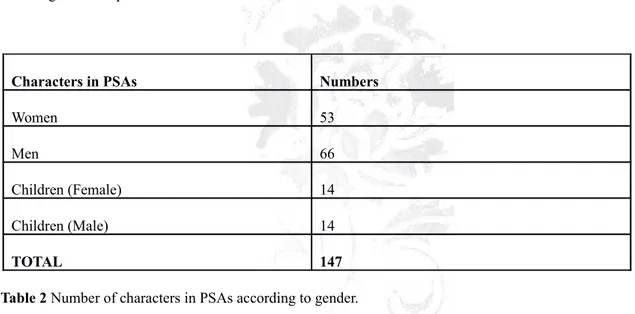

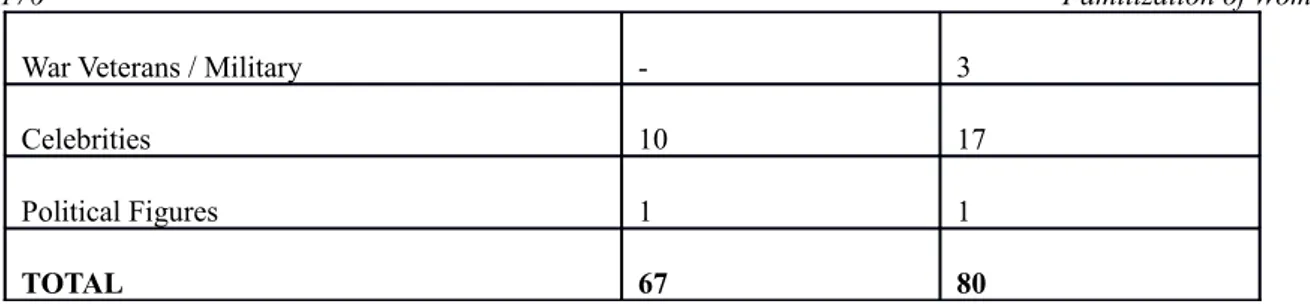

In terms of the total number of characters in PSAs males constitute the majority by 80 characters, whereas there are 67 female characters (Table 2, Table 3). There is an equal representation of girls and boys and a total of 28 children are portrayed in PSAs. Elderly women, who are portrayed as individuals in need and special care, are represented more in numbers than elderly men. On the other hand, there are five characters with disabilities, one of whom is a woman while remaining are represented as men. Celebrity figures also constitute an important part of the narrative with a total of 27 national celebrities including actors, actresses and musicians that appear on TV particularly for advising the citizens about violence against women and the care for abandoned children. Among celebrities, 17 men appear on TV while only 10 women celebrities are portrayed in PSAs. The only political figure in PSAs is President Erdoğan and his wife, Emine Erdoğan, in one of the PSAs aimed at stopping violence against women. Women politicians such as the Minister of Family and Social Policies and other women parliamentarians do not appear in PSAs. The numbers show that though there is an equal representation of youth in terms of the numbers of boys and girls, among adult characters men dominate the narratives. Other than disabled, elderly and celebrity figures, which constitute a minor portion of men represented in whole, men continuously appear in PSAs in family roles as fathers, grandfathers, close relatives and as ordinary citizens especially neighbours. Despite the fact that MFSP includes a specific directorate on women, the way in which the everyday representations of men are portrayed more than women points at the male-hegemonic aspect of PSAs.

Characters in PSAs Numbers

Women 53

Men 66

Children (Female) 14

Children (Male) 14

TOTAL 147

Table 2 Number of characters in PSAs according to gender.

Characters in PSAs Female Male

Women 33 N/A

Men N/A 38

Children 14 14

Elderly 8 3

War Veterans / Military - 3

Celebrities 10 17

Political Figures 1 1

TOTAL 67 80

Table 3 Number of characters in PSAs according to gender categorized by the Directorates under MFSP, further accompanied by external characters (Celebrities and Political Figures).

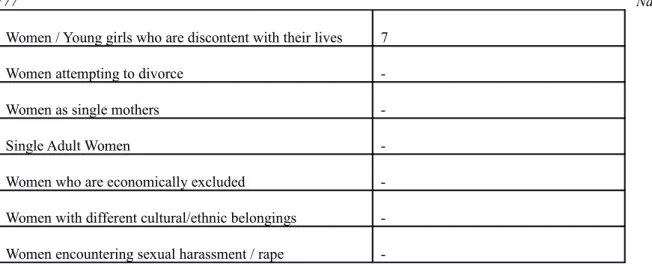

The analysis of the content shows that there are certain significant patterns of representation in terms of the attributes of women characters in PSAs. The most important aspect in representation is that all women in PSAs are portrayed in relation to the family as an institution, with reference to either the existence of family or its nonexistence (Table 4). Women are happy as long as they have proper families; they are portrayed as unhappy if there are certain problems regarding the family structure. In PSAs, there are no women characters who are in their middle ages and are not married; and women are portrayed as unmarried, single individuals only as students or elderly women taken care at centres. In this regard, among 67 women characters (including adults and young), 60 of these characters are portrayed as content with their lives in certain aspects. Only 7 characters are portrayed as discontent with their lives. A young girl being forced to marriage, two women encountering violence, three young girls abandoned or disturbed by the fight of their parents, an elderly woman who is left alone are the characters who face certain troubles in their lives. The aim of these PSAs is the public announcement of a phone number, 183, which can be called by women, elderly, children, veterans and the disabled in case of any emergency. Other than these matters, PSAs do not mention other problems that different women encounter in society; including women attempting to divorce, women as single mothers, unmarried women, women with different cultural/ethnic belongings, women who are economically excluded, women encountering harassment, women encountering rape and women encountering sexual harassment. Eventually, women as represented in PSAs merely correspond to certain segment among women and do not cover several of women’s prominent issues, which may as well be about the notion of family in alternative understandings. The PSAs further portray women mostly as individuals who are content with their lives; a narrative strategy that renders invisible the structures of domination and subordination directed by patriarchal society against women.

Attributes of Women Characters in PSAs Numbers (Out of 67) Women (adult) with household responsibilities 34

Women (adult) with child care responsibilities 26

Women pursuing careers/education 8

Women / young girls abandoned and without any families 4

Women encountering violence 2

Young Girls forced to marriage 1

Celebrity women giving advice 10

Women / Young girls who are discontent with their lives 7

Women attempting to divorce

-Women as single mothers

-Single Adult Women

-Women who are economically excluded

-Women with different cultural/ethnic belongings -Women encountering sexual harassment / rape

-Table 4 Attributes of women characters assigned by the general narratives in PSAs. The categories of women are designed according to the themes narrates by PSAs and was further extended to several of women's.

In addition to the dismissal of women’s prominent issues and the lack of critical distance against patriarchal society in PSAs, women’s roles are also reproduced in accordance with the already established gender hierarchies. In PSAs, women are not portrayed only with their female identities, but as elements of the family who undertake certain roles. The familial roles of women are at the same time displayed as women’s roles. 34 out of 53 adult women characters are screened as undertaking household work and 26 characters are engaged in child-care in household settings. Other women mostly include generic representations including having conversations with other family members. Only 8 women in PSAs are pursuing education or occupied with their professional careers. PSAs tend to define women’s role primarily in terms of traditional gender roles as housekeeping and childcare and depict the happy images of women who undertake such tasks. Young girls are also targeted in terms of getting prepared for their future gender roles. For example, a PSA regarding the abandoned children narrate the desires of a young girl, stating that “we can provide her with a house, but she needs a mother with whom she can prepare the meal together”. Similarly, when men enter the scenes of the family having meals and spending time together, women are mostly seen in housekeeping roles, particularly preparing the meal for the nuclear or extended families to enjoy. There is no single representation in PSAs, which point out the exploitation of women’s unwaged labour at the household due to the gender roles assigned and imposed on women. Rather, the PSAs tend to reproduce the gender roles that are assigned on women in Turkey’s patriarchal cultural setting and define the gender roles in relation to women’s role in the family.

Legitimization of Patriarchy

Among 30 PSAs broadcast by MFSP, 4 PSAs are directly concerned at violence against women. Two of these PSAs were prepared by the Ministry for public announcement of an emergency phone number that individuals in need can call for help at any time. The remaining two were broadcast by KADEM, an association in close contact with the family of President Erdoğan. The PSAs by the Ministry are mainly concerned about providing support for women by encouraging women to apply to the Ministry whenever an emergency occurs. One of these PSAs portray a woman sitting desperately in a bedroom, where stuff is scattered all around the room as a signifier of conflict between the woman and man. The scene implicitly narrates that there has been a fight between the two and that the woman is sitting by herself without knowing what to do. The woman is crying and although she is not physically hurt, the element of violence, at least in psychological terms, is conveyed to the viewer. With reference to the woman’s desperate emotional state, the narrator lets the audience know about 183 that can be called any time in case of need.

The other PSA regarding women encountering violence is the only PSA where violence in a physical state is more explicitly conveyed. The scene begins with a woman crying and zooms in one of her teardrops. The teardrop then turns into a mirror, which reflects the woman’s encounter with violence. In this scene, a man turned back to the viewer is seen as shouting at the woman, who leans against the wall in a frightened emotional

state. The man moves his hands in anger while shouting towards her while she gets even more frightened and is crying. The scene lasts four seconds and then the time is reversed to screen the previously happy moments of the couple once married with high hopes. The narrator then intervenes and calls for women to apply for help to the Ministry for a better life. In both PSAs, the element of violence is conveyed in an implicit way especially with regard to the perpetration of violence. Only in the second PSA, the perpetrator of violence is addressed, though his back is turned against the viewer, whereas the first PSA completely conceals the perpetrator of the violence. Hence the PSAs lack the necessary critical insights that the viewer can engage in an understanding of how patriarchy operates in the domestic sphere. Considering that the PSA prepared by Filmmor which was rejected by the High Council due to its radical critique of patriarchy, portraying marital rape and sexual assault, the PSAs prepared by the Ministry is too shallow to be able to expose the roots of women’s problems, though they tend to touch upon violence as one of the prominent women’s issues.

The two other PSAs concerned with violence against women that are prepared by KADEM association are also problematic in certain aspects. The first PSA consists of a celebrity-centred narrative, which aims to advise the target audience regarding the inappropriateness of violence against women. With famous musicians, actors and actresses starring as well as President Erdoğan and his wife Emine Erdoğan, the slogan of the PSA is “Violence against women is the betrayal of humanity.” The PSA was broadcast on TV in March 2015 and was also attempted by the Presidency, which was pressured by the drastic increase in the rates of femicide and violence against women in recent years. The narration however involves problematic aspects in the sense that it portrays 6 women celebrities whereas men dominate the narration with 14 celebrity figures, which sets up another male-dominated space that does not allow women to express themselves sufficiently. The narration is also based upon persuasion of men not to engage in violent acts, consisting of one-word expressions uttered by the celebrities that first define women and then call for men:

I’m a human being, I’m a woman, she is my wife (x3), she is my daughter, she is my neighbour, she is my mother. Do no shout, do not hurt, do not wound, do not do it, do not overlook, respect, love my brother love, I am you, you are me, mother, sister, wife, friend, woman, human, we are a whole, (Emine Erdoğan speaking) we are against violence against women, (Recep Tayyip Erdoğan speaking) violence against women is a betrayal of humanity.

Target audience of the PSA is situated as men who engage in violent deeds against women. For this aim, the narration initially tends to set up an understanding towards women in a relational sense; pointing at the women as victims’ relation to the perpetrator either as wives, daughters, neighbours and mothers. The men’s point of view in this regard initiates an understanding of women from a familial perspective and suggests that men should not engage in violence against women whom they are relationally linked in some way. The narrative then continues with a call for men not to undertake certain deeds such as wounding and hurting, and rather loving and respecting women. Consequently, Erdoğan and his wife appear on the scene and relate the whole message to a matter of humanity. The PSA shows that women’s subordination has also been acknowledged by the ruling political elite and can be considered as a manifestation of such acknowledgment. The narrative however prefers to relate the issues regarding women to a general problem of humanity, rather than specifying the roots and causes of women’s problems, particularly violence, with regard to the cultural dynamics of patriarchy inherent in Turkey’s social landscape. Rather than challenging patriarchy by allowing women to claim a space of empowerment for themselves via the advertisement, the PSA actualizes a male dominating visual space that solely aims to convince men not to do certain deeds against women, who are defined in relation to those men.

The reproduction of patriarchal motives is also evident in KADEM’s second PSA that is also concerned with violence against women. The PSA begins with a man walking on sideways passing by KADEM’s outdoor advertisements on billboards. The advertisement is a call for action regarding violence, and the slogan is “overcome your anger: End all kinds of violence against everyone”. The man passing by the billboard stops for a few seconds and adds the following expression by writing on the advertisement: “If you are a man”. The camera then shows the final stage of expression, “if you are a man, overcome your anger”, which turns into a call towards men not to engage in any kinds of violence. The expression “if you are a man” in Turkish has a cultural and masculine connotation in its everyday usage which men employ as a sign for their courageous attempts. Therefore, the expression is a manifestation of male hegemony and is entirely sexist in terms of defining

manhood in relation to being courageous. The PSA proceeds towards such a sexist expression to undertake a call for men not to engage in violence. The PSA further includes two problematic aspects. First, it does not openly address violence against women and rather calls for action towards “all kinds of violence”, where the women, who are supposed to be the integral part of the message, is absent. Second, the PSA calls for men to “overcome anger” and legitimizes the state of being angry as a characteristic attributed to men. Rather than calling for men not to get angry in the first place, the PSA admits that men can get angry with women due to their “manhood” but the best way for them is to overcome that anger so that no one gets hurt. As a result, the PSA fails to address the issue of violence against women by at the same time legitimizing male hegemony characterized with anger that indeed is the leading factor to femicide in real life circumstances.

Conclusion

In Turkey, ideology of conservatism has been manifest for decades particularly with the domination of right-wing politics, having close ties with religious establishment and patriarchal culture. Conceiving of women merely in relation to heteronormative family as mothers and wives rather than free individuals, conservatism has led to devastating effects on women in terms of their public visibility and economic participation. The post-2000 period witnessed the AKP’s rise to power with their conservative agenda asserting women’s traditional gender roles; a period which at the same time witnessed an increase in women’s problems including femicide, sexual violence and economic deprivation. The transformation of the Ministry of Women and Family to MFSP in 2011 pointed out a symbolic and a structural change regarding the ways in which the ruling political elite belonging to conservative ideology conceived of women’s issues from a gendered perspective. Since this period, the family has been considered as an institution where the AKP attempted to invest and reproduce the existing power relations for the revitalization of a conservative political agenda that also targeted women. In this regard, PSAs broadcast by the ministry since 2012 were instrumentalized as ideological apparatuses, which carefully and systematically define the status of women under the general rubric of the family discourse. This article aimed to show how women are situated in the wider discourse of the family under the Ministry via PSAs, by first drawing attention to the general patterns of women’s representation in PSAs and then focusing specifically on PSAs directed at women’s issues for a closer analysis.

The analysis of PSAs show that AKP’s gender ideology excludes several of women’s prominent issues from the narrative such as femicide, rape, sexual harassment, economic exclusion and the sexism in law applications. The only issue that it recognizes is violence against women; yet they do so in such a discursive attempt, which reproduces the existing gendered relations of power in two aspects. First, the PSAs do not clearly address patriarchal culture that generates the acts of men as the perpetrators of violence against women. By this way, PSAs fail to encourage the viewer to undertake a critical interrogation of the cultural setting to which s/he participates. Second, PSAs tend to speak to men in order to convince them not to engage in violent deeds and in so doing, automatically normalize and legitimize the deeds and the discourses of patriarchal culture. Eventually, women are familialized by the political motivations of the ruling elite that aims to secure the family as a hegemonic space reproducing patriarchy in line with AKP’s conservatism.

The overall analysis of PSAs by the Ministry shows that women are defined in relation to men and the family, rather than autonomous individuals with female identities. Women are further imagined as the integral elements of the nation, attributed with traditional gender roles such as housekeeping and child caring. The political discourse of “strengthening the family” is proposed as the solution of the problems that disadvantaged groups encounter, particularly women’s. Such an approach however deems the real structures of domination invisible; not only for women but also for other socially disadvantaged groups; whose urgent needs are also broadly categorized as familial necessities. In Turkey, the family serves as a superstructure that function as the waiver of the existing power relations, rather than their dissolution. Particularly with regard to women, the family becomes a grand narrative, which is posed as the solution of all problems, without necessarily addressing the causes of those problems.

Turkish president declares women and men are not equal. 24 November 2014.

http://www.telegraph.co.uk/news/worldnews/europe/turkey/11250795/Turkish-president-declares-women-and-men-are-not-equal.html (accessed December 12, 2015).

2Erdoğan: Doğum kontrolüyle kısırlaştırdılar (Erdoğan: They neutered us with birth control). 18 June

2013.http://www.milliyet.com.tr/erdogan-dogum-kontroluyle/siyaset/detay/1724651/default.htm (accessed December 12, 2015).

3Turkish President Erdoğan declares birth control ‘treason’. 22 December 2014.

http://www.hurriyetdailynews.com/turkish-president-erdogan-declares-birth-control-treason.aspx?pageID=238&nID=75934&NewsCatID=338 (accessed December 12, 2015).

4If your parents fail to marry you, come to us, PM tells Turkish youth. 23 October 2015.

http://www.hurriyetdailynews.com/if-your-parents-fail-to-marry-you-come-to-us-pm-tells-turkish-youth.aspx?PageID=238&NID=90246&NewsCatID=338 (accessed December 12, 2015).

5Global Gender Gap Report - Rankings. November 2015. http://reports.weforum.org/global-gender-gap-report-2015/rankings/

(accessed November 19, 2015).

6Prosecutor approves rape victim's 'consent' to sex. 6 October 2011.

http://www.hurriyetdailynews.com/prosecutor-approves-rape-victims-consent-to-sex.aspx?pageID=438&n=prosecutor-approves-rape-victim8217s-8216consent8217-to-sex-2011-10-06 (accessed November 12, 2015).

7Cinayete ''Aşırı sevgi'' indirimi (Deduction of Punishment Due to "too much love"). 9 November 2015.

http://www.ntv.com.tr/turkiye/cinayete-asiri-sevgi-indirimi,AYg7g94Uf0Gs2mhKhzkJ-A (accessed December 12, 2015).

8İstatistiklerle Kadın, 2014 (Women in Statistics, 2014). 2015 March 2015. http://www.tuik.gov.tr/PreHaberBultenleri.do?id=18619

(accessed August 25, 2015).

9The directive by RTÜK is available online at http://www.rtuk.org.tr/Home/SolMenu/25#

10Kamu spotlarında düşüş yaşandı (Decrease in Public Spots). 22 June 2014.

http://www.evrensel.net/haber/86798/kamu-spotlarinda-dusus-yasandi (accessed December 12, 2015).

11Ekrandaki Kamu Reklamları Tırmanışa Geçti (Increase in Public Advertising on TV). 14 April 2015.

http://www.haberler.com/ekrandaki-kamu-reklamlari-tirmanisa-gecti-7191039-haberi/ (accessed December 12, 2015).

12The association published the video online at their Facebook account by announcing that their video was rejected by the High

Council as a PSA to be screened on TV https://www.facebook.com/Filmmor/posts/230608770417247

13The news items were published at the campaign website “Biz büyük bir aileyiz” (We are a big great family)

http://bizbuyukbiraileyiz.gov.tr/sub.php?sf=basinhaber&k=52&u=207

14Meclis Boşanmaları Araştıracak (Parliament will investigate divorce). 16 December 2015.

http://m.bianet.org/bianet/toplumsal-cinsiyet/170239-meclis-bosanmalari-arastiracak (accessed December 16, 2015).

Bibliography

“(Action Plan for Protection and Strenghtening of the Family in Turkey).” Aile ve Sosyal Politikalar Bakanlığı (Ministry of Family and Social Policies), Ankara, 2013.

Çavdar, Gamze. “Islamist Moderation and the Resilience of Gender: Turkey's Persistent Paradox.” Totalitarian Movements and Political Religions 11, no. 3-4 (2010): 341-357.

Çitak, Zana, and Özlem Tür. “Women Between Tradition and Change: The Justice and Development Party Experience in Turkey.” Middle Eastern Studies 44, no. 3 (2008): 455-469.

Özbudun, Ergun. “AKP at the Crosssroads: Erdoğan's Majoritarian Grift.” South European Society and Politics 19, no. 2 (2014): 155-167.

Akan, Taner. “The political economy of Turkish Conservative Democracy as a governmental strategy of industrial relations between Islamism, neoliberalism and social democracy.” Economic and Industrial Democracy 33, no. 2 (2012): 317-349.

Arat, Yeşim. “Religion, Politics and Gender Equality in Turkey: Implications of a Democratic Paradox.” Third World Quarterly 31, no. 6 (2010): 869-884.

Belge, Burçin. "Women Policies Erased from Political Agenda". 9 June 2011. http://bianet.org/english/women/130607-women-policies-erased-from-political-agenda (accessed 12 12, 2015).

populism in Turkey.” Science & Society 77, no. 3 (2013): 372-396.

Bryson, Valerie and Timothy Heppell. “Conservatism and feminism: the case of the British Conservative Party.” Journal of Political Ideologies 15, no. 1 (2010): 31-50.

Carrington, Victoria. “Globalization, Family and the Nation State: Reframing "Family" in new times.” Discourse: Studies in the Cultural Politics of Education 22, no. 20 (2001): 185-196.

Coşar, Simten, and Metin Yeğenoğlu. “New grounds for patriarchy in Turkey? Gender Policy in the Age of AKP.” South European Society and Politics 16, no. 4 (2011): 555-573.

Crowson, Michael; Thoma, Stephen and Nita Hestevold. “Is Political Conservatism Synonymous With Authoritarianism?” The Journal of Social Psychology 145, no. 5 (2005):571-592.

Daloglu, Tulin. Erdogan Insists on Demanding Three Children. 13 August 2013. http://www.al-monitor.com/pulse/originals/2013/08/erdogan-asks-turks-to-have-three-children.html# (accessed December 12, 2015).

Eslen-Ziya, Hande. “Social Media and Turkish Feminism: New resources for social activism.” Feminist Media Studies 13, no. 5 (2013): 860-870.

Foucault, Michel. The history of sexuality volume 1: An introduction. New York: Random House, 1990.

Gill, Rosalind. "Supersexualize me! Advertising and the Midriffs." In Mainstreaming Sex: The Sexualization of Western Culture, edited by Feona Atwood, 93-110. London & new York: IB Tauris, 2009.

Goldman, Robert. Reading Ads Socially. London & New York: Routledge, 1992.

İlkkaracan, İpek. “Why so Few Women in the Labor Market in Turkey?” Feminist Economics 18, no. 1 (2012): 1-37. Kalaycioğlu, Ersin. “Politics of Conservatism in Turkey.” Turkish Studies 8, no. 2 (2007): 233-252.

Kandiyoti, Deniz. “Emancipated but unliberated? Reflections on the Turkish case.” Feminist Studies 13, no. 2 (1987): 317–338.

Kaya, Ayhan. “Islamisation of Turkey under the AKP Rule: Empowering Family, Faith and Charity.” South European Society and Politics 20, no. 1 (2015): 47-69.

Letsch, Constanze. Istanbul hospitals refuse abortions as government’s attitude hardens. 4 February 2015. http://www.theguardian.com/world/2015/feb/04/istanbul-hospitals-refuse-abortions-government-attitude

(accessed December 12, 2015).

Lutz, Catherine, and Jane Collins. Reading National Geographic. Chicago: The University of Chicago Press, 1993. McFall, Liz. Advertising: A Cultural Economy. London: Sage, 2004.

Müftüler-Bac, Meltem. “Turkish Women’s Predicament.” Women’s Studies International Forum 22, no. 3 (1999): 303-315.

O'Keefe, Garrett J., and Kathalein Reid. “The Uses and Effects of Public Service Advertising.” Public Relations Research Annual 2 (1990): 62-91.

Parsons, Talcott, and Robert Freed Bales. Family, socialization and interaction process. Glencoe, IL: Free Press, 1955. Phelan, John M. “Selling Consent: The Public Sphere as a Televisual Marketplace.” In Communication and Citizenship,

edited by P. Dahlgren and C. Sparks, 74-93. New York: Routledge, 1991.

Rose, Gillian. Visual Methodologies: An Introduction to the Interpretation of Visual Materials. London: Sage, 2007. Saraçoğlu, Cenk. “Islamic conservative nationalism’s projection of a nation: Kurdish policy during JDP’s rule (in

identification in contemporary Turkey.” Women's Studies International Forum 53 (2015): 12-21.

Unal, Didem, and Dilek Cindoglu. “Reproductive citizenship in Turkey: Abortion chronicles.” Women's Studies International Forum 38 (2013): 21-31.

Vela, Justin. 'Abortions are like air strikes on civilians': Turkish PM Recep Tayyip Erdogan's rant sparks women's rage . 30 May 2012. http://www.independent.co.uk/life-style/health-and-families/health-news/abortions-are-like-air-strikes-on-civilians-turkish-pm-recep-tayyip-erdogans-rant-sparks-womens-rage-7800939.html (accessed December 12, 2015).

Walsh, Froma. Normal family processes: Growing diversity and complexity. New York: The Guilford Press, 2003. Williamson, Judith. Decoding Advertisements: Ideology and Meaning in Advertising. London: Marion Boyars, 1978. Wong, Wendy Siuyi. “Political Ideology in Hong Kong’s Public Service Announcements.” In Advertising and Hong

Kong Society, edited by Kara K.W. Chan, 55-76. Hong Kong: Chinese University Press. , 2005.

Yılmaz, Zafer. “"Strenghtening the Family" Policies in Turkey: Managing the Social Question and Armoring Conservative-Neoliberal Populism.” Turkish Studies 16, no. 3 (2015): 371-390.

Yazıcı, Berna. “The return to the family: welfare, state, and politics of the family in Turkey.” Anthropological Quarterly 85, no. 1 (2012): 103-140.