SELÇUK ÜNİVERSİTESİ

SOSYAL BİLİMLER ENSTİTÜSÜ

YABANCI DİLLER EĞİTİMİ ANA BİLİM DALI

İ

NGİLİZCE ÖĞRETMENLİĞİ BİLİM DALI

ESKİ YUNAN VE ROMA MİTOLOJİSİNİN İNGİLİZCE MESLEKİ

YABANCI DİL DERSLERİNDE MATERYAL OLARAK KULLANIMI

( S.Ü. BEYŞEHİR MESLEK YÜKSEKOKULU

TURİZM REHBERLİĞİ PROGRAMI ÖRNEĞİ )

YÜKSEK LİSANS TEZİ

DANIŞMAN

Yrd. Doç. Dr. Nazlı GÜNDÜZ

HAZIRLAYAN

İ

hsan GÜNEŞ

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

I would like to express my gratitude to all who have supported and guided me in this thesis but most of all to Assist. Prof. Dr. Nazlı GÜNDÜZ for her enduring advice and patience from the beginning to the end. It would not have been possible without her help. I also wish to thank my students who took part in this study. Above all, I feel obliged to extend my deepest thanks to my wife, Emine, and my children for their patience, warm support and understanding they have shown during my long hours of study.

ABSTRACT

Because of the lack of published course materials for foreign language classes in tourist guide training courses, the foreign language teachers have to prepare their own teaching materials. The purpose of this study is to investigate how useful the stories of Greek and Roman mythology are when they are developed and used as teaching materials in the English lessons of tourist guiding programmes. To achieve this goal, a brief literature review has been made on Greek and Roman mythology, vocabulary and cultural values derived from the ancient world and the tourist guide training systems in Turkey and in some other countries have been compared. Within this aim, the stories of Greek and Roman mythology are developed and used as teaching materials in a short model course of 18 lessons which is applied to the first class students of tourist guiding programme of Selçuk University Beyşehir Vocational School of Higher Education. Before the short model course was carried out, it was decided to apply a questionnaire in order to determine the expectations and the needs of the students. After the experimental course, a second questionnaire was applied in order to research the students’ opinions on the lessons. The results of both questionnaires have been compared to asses how well the developed materials covered students’ needs and expectations.

ÖZET

Turist rehberliği eğitimi veren eğitim kurumlarında İngilizce derslerinde kullanılmak amacıyla hazırlanmış ders materyallerinin neredeyse hiç olmamasından dolayı, bu kurumlarda çalışan İngilizce öğretmenleri kendi ders materyallerini hazırlamak zorundadırlar. Bu çalışma, turist rehberliği eğitimi veren programlarda, eski Yunan ve Roma mitolojik öykülerinin ders materyali olarak geliştirilip kullanılmasının ne kadar faydalı olduğunu araştırmayı amaçlamaktadır. Bu amaca ulaşmak için, Yunan ve Roma mitolojileri, bu mitolojilerden gelen sözcükler, atasözleri ve deyimler, ve Türkiye ile bazı ülkelerin turist rehberi eğitim sistemi üzerine bir literatür taraması yapılmıştır. Yunan ve Roma mitolojik öyküleri ders materyali olarak geliştirilmiş ve geliştirilen materyaller Selçuk Üniversitesi Beyşehir Meslek Yüksekokulu Turist Rehberliği Programı birinci sınıflarında mesleki yabancı dil derslerinde 18 ders saati kullanılmıştır. Bu uygulamadan önce, öğrencilerin derslerden beklentilerini saptamak amacıyla bir anket; uygulamadan sonra ise, öğrencilerin uygulanan dersler hakkındaki düşüncelerini ölçmek amacıyla ikinci bir anket yapılmıştır. Her iki anketin sonuçları uygulanan derslerin öğrencilerin beklentilerini ve ihtiyaçlarını ne kadar karşıladığını değerlendirmek amacıyla karşılaştırılmıştır.

LIST OF TABLES

Table 1 Do you want to be a tourist guide? ... 23

Table 2 Would you prefer being an English teacher or a tourist guide? ... 24

Table 3 Have you ever worked as a tourist guide? ... 24

Table 4 What is your gender? ... 24

Table 5 How old are you? ... 24

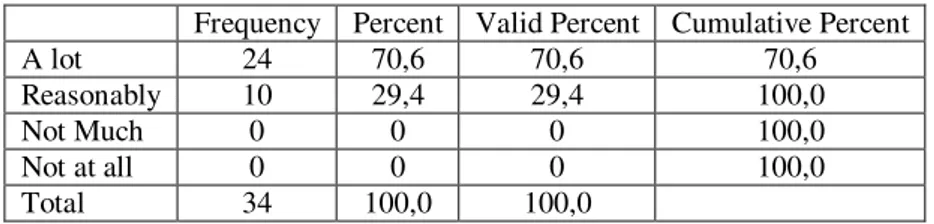

Table 6 How much do you know about mythology? ... 25

Table 7 How much grammar do you expect and think you need to cover your English classes? ... 25

Table 8 How much Vocabulary do you expect and think you need to cover your English classes? ... 25

Table 9 How much Reading do you expect and think you need to cover your English classes? ... 26

Table 10 How much Writing do you expect and think you need to cover your English classes? ... 26

Table 11 How much Listening do you expect and think you need to cover your English classes? ... 26

Table 12 How much Speaking do you expect and think you need to cover your English classes? .... 27

Table 13 How much Pronunciation do you expect and think you need to cover your English classes? ... 27

Table 14 How much Translation do you expect and think you need to cover your English classes? ... 27

Table 15 A Crosstable of Students’ Needs and Expectations... 28

Table 16 Please state the number of classes you attended. ... 31

Table 17 How much do you think you improved the following? ... 32

Table 18 Please say how much you coped with the following. ... 33

Table 19 How useful were the pre-reading activities? ... 34

Table 20 How useful were the post-reading activities? ... 36

Table 21Please say how much you enjoyed the lessons... 37

TABLE OF CONTENTS

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS ... i ABSTRACT ... iii ÖZET ... iv LIST OF TABLES ... v TABLE OF CONTENTS ... vi CHAPTER 1 ... 11.1. Background to the Study ... 1

1.2. Problems of Teaching Foreign Languages to Tour Guide Students ... 3

1.3. The purpose of the Study ... 5

1.4. Hypotheses ... 5

1.5. Research Methodology ... 6

CHAPTER 2 ... 8

REVIEW OF LITERATURE ... 8

2.1. Greek and Roman Mythology ... 8

2.2. Vocabulary and Cultural Values Derived from the Ancient World ... 9

2.2.1. The Myth of Hercules ... 10

2.2.2 The Myth of the Trojan War ... 11

2.2.3. The Myth of Cupid and Psyche ... 14

2.3. Comparison of Tour Guide Training in Turkey and other Countries ... 17

2.3.1. Tourist Guide Training in the USA ... 17

2.3.2. Tourist Guide Training in Scotland ... 18

2.3.3. Tourist Guide Training in Greece... 18

2.3.4. Tourist Guide Training in Iceland ... 19

2.3.5. Tourist Guide Training in London ... 19

2.3.6. Tourist Guide Training in Turkey ... 20

CHAPTER 3 ... 22

METHODOLOGY ... 22

3.1. Aims of the First Questionnaire ... 22

3.2. Hypotheses of the First Questionnaire ... 23

3.3. Data Analysis of the First Questionnaire ... 23

3.4. Results of the First Questionnaire ... 28

3.5. Aims of the Second Questionnaire ... 30

3.7. Data Analysis of the Second Questionnaire ... 31

3.8. The result of the Second Questionnaire ... 37

CHAPTER 4 ... 41

THE DEVOPMENT OF THE LESSONS ... 41

4.1. Aims of the classes ... 41

4.2. Development of the texts ... 41

4.2.1 Lesson 1: Pandora’s Box ... 42

4.2.2. Lesson 2: Echo and Narcissus ... 49

4.2.3 Lesson 3: Cupid and Psyche ... 55

4.2.4. Lesson 4: Orpheus and Eurydice ... 64

4.2.5. Lesson 5: King Midas and the Golden Touch ... 71

4.2.6. Lesson 6: Hercules... 78

CHAPTER 5 ... 86

CONCUSION ... 86

REFERENCES ... 89

CHAPTER 1

INTRODUCTION TO THE STUDY

The students of 2-Year (Diploma) Tourist Guiding Courses of universities in Turkey, generally, are not linguistically proficient in their chosen foreign language in order to direct and control the group as well as disseminate information and interpret the sites visited. This is not because the students are not taught the necessary guiding subjects such as History, Mythology and Geography, which are essential for tour guiding commentaries, sufficiently, but because their speaking, pronunciation and listening abilities are not improved well enough during their education period. These students know a great deal about many different subjects related to tour guiding but lack the necessary language skills for doing their job. One reason might be that there are almost no published ESP (English for Specific Purposes) teaching materials to use in these courses. Therefore, the foreign language teachers on duty have to prepare their own ones. This study aims to show how the stories of Greek and Roman Mythology can be used as teaching materials in English classes of Tourist Guiding Courses. Six mythological stories have been chosen to be used in English classes of Tour Guiding Programmes of Selçuk University Beyşehir Vocational School of Higher Education. These stories have been enriched with different kind of activities to improve the students’ related skills. The lesson materials are assessed in terms of their effectiveness in satisfying the demands of the students. The following sections detail the background to this study, the problems, the hypotheses and the scope of the research.

1.1. Background to the Study

According to the regulations of Professional Tour Guides of the Ministry of Culture and Tourism, a tour guide is someone who introduces Turkey both to foreign and native tourists in the best way, who helps them during their tours and gives the most correct information. Another description is made by Ahipaşaoğlu (2001):

A tour guide is someone who facilitates the tour from the beginning till the end, who is in a healthy communication with the tourists during their travel, who vividly interprets the sites visited, who enables the tourists to spend a nice time,

and who helps them in unusual situations and to protect their rights during their travel.

Many definitions have been made of who a tour guide is but to describe his/her duties is better to understand to describe the limits of this profession. Ortega (2007) states that, “Main three duties of a tour guide are: 1-helping the tourists, 2- disseminating true, technical information, 3- introducing the country and representing the nation”. To fulfil his/her duties adequately, a tour guide has to be in a non-stop interaction with the tourists, so it requires a high level of the used language. A tour guide is usually the first native person met closely by the tourists, that’s why he/se is not only regarded as just a helper but also as a representative of the nation. In this sense a tour guide plays a great role in reflecting the values of the nation. (Tangüler, 2005)

The prophet Moses, who guided half a million people through the Red Sea, is said to be the first tour guide in the world, but as a profession tour guiding has been done since the ancient times. Migrations from one continent to another, wars, trading caravans, visiting holly places, and many other factors made this profession emerge. (Çimrin, 1995)

In Turkey, in 1925, soon after the foundation of the new republic, the new government broadcasted instructions on the guiding of foreign nationals, and in 1929, the first licensed tour guiding training was started in Istanbul. (Ahipaşaoğlu, 2001: 19-21). The training courses improved over the years and, in 1983, Turkish Ministry of Culture and Tourism started the first licensed tour guide courses. Academic training of tour guiding started with the foundation of Erciyes University Tourist Guiding Department in Nevşehir in 1997. There are now four different courses that train tour guides:

a- a three-month course run by the Ministry of Tourism for a local tour guiding license,

b- a six month course run by the Ministry of Tourism for a national tour guiding license,

c- a two year university diploma course in tour guiding, and

d- a four year university degree course in tour guiding. (Özbay, 2002)

To enrol to the courses run by the Ministry the applicants have to be at least a high school graduate and know a foreign language well enough. Either gaining at least 70 points from the KPDS (the Turkish state’s foreign language exam) or passing the language exam made by the ministry itself is another requirement for registration. High school graduates have to pass the ÖSS (university entrance exam) and the YDS (university entrance foreign language exam) to be a member of a two-year diploma or four-year university degree courses.

The syllabuses followed at all the courses are basically the same. (Özdal, 2001). The following subjects are thought on the courses of the Ministry of Culture and Tourism.

1. General Tourism and Tourism Regulations 2. Tour Guiding

3. Tourism Geography of Turkey 4. Archeology

5. Art History 6. Mythology

7. Religion, Folklore and Sociology 8. Turkish History

9. Turkish Literature 10. First Aid

(www.kultur.gov.tr/TR/BelgeGoster.aspx?F6E10F8892433CFF4A7164CD9A18CEAEA9 21E9EDE01F4A70)

Tour guiding related subjects such as History, Mythology, Archaeology, Geography, Architecture, Art and History, Religions and Traditional Culture are in common in all courses. Foreign Languages, mostly English, are taught intensely on the University courses from six to sixteen classes per week each term. After being a graduate of a two-year university diploma course or a four-year university degree course, gaining at least 70 points from KPDS (the Turkish state’s foreign language exam) is compulsory to obtain a tourist guiding licence from the Ministry of Culture and Tourism. Attending a thirty day long tour of Turkey is another requirement for both university students and course attendants to obtain a tourist guiding licence. Although training of tour guides has improved over the last twenty-five years, there are many problems that both the teachers and the students face in terms of foreign language teaching and learning.

1.2. Problems of Teaching Foreign Languages to Tour Guide Students

While tour guiding is taught academically at universities in Turkey, the students still lack the productive oral practice of their knowledge. Although there is an intense language

teaching programme, from 4 to 10 classes per week each term, there are still many difficulties that both the teachers and the students encounter.

As mentioned in the previous section, the students may attend to the university tourist guide training courses only if they pass the ÖSS (student selecting exam), which is a test of multiple choices about many different subjects such as History, Turkish, Maths, Geography etc., and the YDS (foreign language exam) which is a test of multiple choices, too. Students, who enter and gain higher marks, might also enrol to the teacher training departments of all state’s and private universities. This causes to the result that almost all of the students, who have enrolled to tour guide training courses, do not want to be tour guides in fact because their ideal was, and to most of them still is, to become a foreign language teacher not a tour guide. Due to this problem, there is a lack of motivation which has a negative effect on language teaching.

The requirement of gaining at least 70 points of the Turkish state’s KPDS exam is also a problem. This exam is a test of language recognition, not production. It does not mean that the students who gain 70 points or more from this exam have the ability to speak well in English. Nor does the KPDS exam test tour-guiding related language, which should include tour guiding topic vocabulary as well as skills involved in language production. Despite this fact, teachers of foreign languages have to include preparation for the KPDS exam in the syllabus because it is compulsory to obtain a tourist guiding licence from the Ministry of Culture and Tourism.

Another problem is that the guiding related subjects taught at university courses such as History, Mythology, Archaeology, Geography, Architecture, Art and History, Religions and Traditional Culture are mostly taught in Turkish – not the foreign language that students will mainly use for tour guiding (i.e. English). This means that the tour guiding related language is ignored and as a result, students lack productive oral practice of their knowledge.

Because of the above mentioned reason, the responsibility for foreign language tour guiding practice falls on the foreign language teachers. But they usually fail to accomplish their tasks mainly because of the complete lack of teaching materials. Teachers, therefore, mostly have to prepare these specific materials by themselves, and because they are not from the profession of tour guiding it self, they face serious problems. It is because of this fact that the syllabuses of two year diploma university courses are mainly based on grammar repetition, which aims preparation for the KPDS exam.

1.3. The purpose of the Study

The main purpose of this study is to pilot and evaluate a model course of thirty English lessons (one semester) in tour guiding classes in Selçuk University Beyşehir Vocational School of Higher Education, wherein Greek and Roman mythological stories are used to assess how they contribute to students’ speaking, listening and reading skills as well as their motivation. We believe that the use of Greek and Roman mythological stories will greatly enhance the language abilities of the first year students of Selçuk University Beyşehir Vocational School of Higher Education Tourist Guiding Programme. The specific objectives of this study are listed are as follows:

1. To find out the extent of the students’ needs and expectations in regard to English classes by applying a questionnaire to the first class of Tour Guiding Programme of Selcuk University Beyşehir Vocational School of Higher Education.

2. To find out how useful Greek and Roman mythological stories will be for students’ speaking skills by enriching them with role play and discussion activities.

3. To find out how useful these stories will be for students’ listening skills by using podcasts as listening exercises.

4. To find out how useful these stories will be for students’ reading and comprehension skills by including some reading comprehension exercises.

5. To find out whether these stories will help students’ motivation or not.

6. To find out what contributions they will make to students’ learning the culture of the English people by teaching the idioms, proverbs and moral lessons, derived from these stories, that have influenced modern English culture.

1.4. Hypotheses

It is believed that the use of Greek and Roman mythological stories will make many contributions to students to be linguistically proficient in tourist guiding at the Tourist Guide Training Courses of Beyşehir Vocational High School of Selçuk University.

The research hypotheses are:

• By using Greek and Roman Mythology texts as teaching materials students will be easily motivated, because these stories are both meaningful and enjoyable,

• This kind of teaching material will be useful for improving students’ language skills in general, because these stories can be easily enriched with many discussion, role play, vocabulary, listening and writing activities,

• The level of these texts can easily be simplified so that the students can cope with these texts easily.

• Because English is filled with vocabulary, idioms, allusions and cultural values derived from these stories, these texts will contribute to students learning the culture of English speaking countries and thus help learning English in general.

1.5. Research Methodology

This study consists of four stages. Firstly, a literature review will be made on both tour guiding and Greek and Roman Mythology. Secondly, to understand the depth of the problem and students’ expectations, the students will be asked to fill in a questionnaire, which will be statistically analysed. Thirdly, six Greek and Roman Mythological stories will be chosen and enriched with a number of listening, speaking and reading activities, and will be used in the experimental group. Finally, a questionnaire will be used to asses the course. Quantitative techniques will be used to asses the model course. The frames of the methodologies that will be used in each stage are outlined as follows:

1. A detailed literature review will be made on mythology, its influences on the language and culture of English speaking countries and on tourist guiding. 2. To establish the degree of lack of motivation and their expectations, a

questionnaire will be administered to 40 first year tour guiding students and the result will be analyzed.

3. Six mythological stories will be chosen and enriched to use in the experimental group. Podcasts will be downloaded from the internet and used to develop listening exercises; discussion and role play activities will be added to these stories to develop speaking exercises; a list of vocabulary and idioms derived from these stories will be made and the cultural values of the native speakers will be discussed and compared with the Turkish culture to improve the cultural understanding; and some writing exercises will be included to improve students’ writing skills.

4. A final questionnaire will be administered to the same class and the result will be analyzed.

CHAPTER 2

REVIEW OF LITERATURE

This chapter reviews the literature on Greek and Roman mythology, tour guiding and a comparison of tour guide training in Turkey and in some other countries. Firstly, the Greek and Roman mythology is examined in order to gain an overview of their influence on modern western world in general and especially on modern English language. Their influences are exemplified with vocabulary, idioms and proverbs derived from these myths. Secondly, three popular myths are chosen and narrated briefly, and are examined to see how much these myths have affected the modern English language by studying the meanings of the words derived from them. Finally the tour guide training in other countries is examined and compared to the Turkish ones.

2.1. Greek and Roman Mythology

Stories that help to explain the mysteries of the world are called myths and most myths contain magical ideas that were believed when the myth was first created. (Whittaker, 2004) A myth might be seen as an interesting story or a fantasy if the reader is not a part of that culture, but it turns to a belief if someone shares the same culture or religion. (Planaria, 2002) Since the beginning of humankind’s existence, people have created myths to find answers to the inexplicable. Because there were no satisfactory answers for many questions due to the lack of science, people tried to explain these unknown by devising myths. (Hoover, 1995) The absence of scientific information made scientists devise stories to answer such questions as: Who made the world? Who was the first human? Why does the sun travel across the sky? Why do we have annual agricultural cycles and seasonal changes? Why does the moon wax and wane? So, the need for a myth was a universal need. Over time, one version of a myth would become the accepted standard that was passed down to generations, first through story-telling, and then, much later, in written form. Inevitably, myths became part of systems of religion, and were integrated into rituals and ceremonies, which included music, dancing and magic. (Hoover, 1995)

Greek Mythology, which has been an important part of the English language, literature, art, and music for over six hundred years, appeared more than three thousand years

ago when the Greeks began developing their own religion. The Greek religion was polytheistic, they believed in many gods and goddesses. With the conquest of Greece by Rome, the stories of the ancient Greek religion were adopted to by the Romans. The religion began to disappear when the Roman emperor Constantine was converted to Christianity in A.D. 312. (Planaria, 2002) But the stories of their gods, the myths remained.

These stories were first written by the most famous Greek poet Homer and were retold in Latin by Roman poet Virgil (70-19 B.C.), and later by another Roman poet named Ovid (43 B.C. – A.D. 18) Christianity came to England around 600A.D. and the Catholic monks translated the works of Homer, Virgil and Ovid into English. Geoffrey Chaucer (1343-1400) and William Shakespeare (1564-1616) retold the Greek and Roman Myths in English Literature. (Hamilton, 1996)

For over six ages, the legacy of ancient Greeks and Romans has been of major influence on the course of Western civilization. Ancient Greeks and Romans made many contributions to contemporary life. Among them are those which influence art, architecture, literature, philosophy, mathematics and science, theatre, athletics, religion, and the founding of democracy. (Whitelaw, 1995)

These stories have also greatly influenced the English language. As we deal with the use of these stories in English classes, it is necessary to lay stress on the contributions they made on the English language. The roots of much of the English language come from the ancient world. Lots of vocabulary, nouns, verbs, adjectives and adverbs derive from these well-known myths. Besides, many idioms and proverbs trace its roots back to ancient Greek and Roman. The English culture also inherited many cultural values from the ancient world. (Highet, 1985)

The following section details the influences of Greek and Roman mythology by giving examples to the most commonly used vocabulary and cultural values tracing its roots back to ancient world.

2.2. Vocabulary and Cultural Values Derived from the Ancient World

Since Greek and Roman Mythological stories have been a considerable part of the English language, literature, art and music for more than six hundred years, it is easy to understand what an important place these myths have in the literature, vocabulary, idioms and culture of the English-speaking world. Being familiar with as many of these myths as possible, will make considerable contributions in being fluent in English. In this part of the

study, some of the most popular of these myths are examined to make a list of lexical items that are derived from these myths.

2.2.1. The Myth of Hercules

Hercules, the most popular hero of the ancient Greece, has more stories told of his adventures than any other figure in Greek Mythology. Because he was accepted as the strongest mortal on earth, the Greeks admired him very much. His stories were part of the ancient Greek oral tradition but most of them have been lost. Yet there are versions of the stories of Hercules in tragedies of famous Greek playwrights, Sophocles and Euripides. (Planaria, 2002)

The story begins with the birth of Hercules which made Hera, Zeus’s wife very angry because he was the son of Zeus, the king of Gods, and a mortal married woman named Alcamena. When Hercules grew up, Hera decided to punish him and sent a madness upon him. Under this spell of madness, Hercules killed his three sons and then his beloved wife. When he awoke from this madness, he was convinced to consult an oracle to discover the appropriate punishment by his friends. The oracle told Hercules to complete twelve seemingly impossible tasks to clean himself of the sin of murder. These very difficult tasks are called the labours of Hercules. (Fink, 2004)

Below is a list of lexical items that trace back to the famous myth Hercules. The meanings of these lexical items have been quoted from Collins Cobuild English Language Dictionary, Cambridge International Dictionary of Idioms, Cambridge Advanced Learner’s Dictionary, The Oxford Dictionary of English and Mythological Dictionaries.

1- Herculean (adjective)

Contemporary meaning: To describe someone as Herculean is to liken him to Hercules in strength and stature. Any effort that is Herculean requires a tremendous exertion or spirit of heroic endurance. The Hercules is a constellation in the northern hemisphere near Lyra and Corona Borealis. A shrub, indigenous to the South-eastern United States and characterized by prickly leaves and large clusters of white blossoms, is known as Hercules' club.

2- A Herculean task (idiom)

Contemporary meaning: Attempting an extremely difficult task.

E.g. you must take a Herculean effort not to talk to them about it.

3- An atlas (noun)

Contemporary meaning: A book containing maps in American English. E.g. a road atlas, an atlas of the world

The myth: Atlas was a Titan, a giant, who had been punished by Zeus and was forced to carry the heavens on his shoulders. The eleventh labour of Hercules was to get the golden apples of three nymphs. No-one knew where they lived but Atlas, so Hercules went to him to him to ask directions. (Schwab, 2004), (Fink, 2004)

4- Like the Augean stables (idiom)

Contemporary meaning: a disgusting place or situation.

E.g. the house was like the Augean stables, it had not been cleaned maybe for years. The myth: One of Hercules’s tasks was to clean the stable of Augean, who had three thousand cows and the stable had not been cleaned for thirty years.

5- Hydra-headed (adjective)

Contemporary meaning: a difficult problem that keeps returning E.g. the country’s economy policy turned to a hydra-headed situation.

The myth: In one of the tasks Hercules had to go to the underworld and kill a monster called Hydra, which had fifty snake heads and when Hercules cut of one head two grew in its place.

6- Amazon (noun)

Contemporary meaning: a strong forceful woman

E.g. she walked in to the room like an Amazon and shouted at the children.

The myth: In one of the tasks Hercules had to bring back the belt of Hippolyta, who was the queen of the Amazons, fierce warrior women.

2.2.2 The Myth of the Trojan War

The story of Troy appears in several different ancient sources. One of them is The Iliad, which is the most famous book from ancient Greek, was written in poetry in twenty-four chapters by a famous poet called Homer. It is known that he lived sometime around eighth or

ninth century B.C. The Iliad has an important place and influence in world history, art and literature. (Michael, 2004) The story begins with the details of an argument between the king Agememnon and the great warrior Achilles and it ends with the death of prince Hector, who was also a great warrior, and the destruction of the kingdom of Troy. (Wöhlche, 2004)

Below is a list of lexical items that trace back to the story of Trojan War. The meanings of these lexical items have been quoted from Collins Cobuild English Language Dictionary, Cambridge Advanced Learner’s Dictionary, Cambridge International Dictionary of Idioms, Oxford Dictionary of English and Merriam Webster Dictionary.

1- to have a face that launched a thousand ships (idiom) Contemporary meaning: to be an extremely beautiful woman

The myth: The war between Sparta and Troy started when Paris, prince of Troy, stole Helen, Menelaus’s wife, king of Sparta. Helen was the most beautiful woman in the world and was pursued by many princes before she chose her husband. King Tyndarus, Helen’s father, made each suitor swear on oath that if anyone tried to carry Helen away, all the suitors would join together to protect the honour of Helen and her husband. When she was carried away by Paris, thousands of ships were launched to Troy to get her back and to protect their honour. (Wöhlche, 2004) , (Fink, 2004)

E.g. was this the face that launched a thousand ships and burnt the topless towers of Ilium?

2- to have an Achilles heel

Contemporary Meaning: a small fault or weakness in a person or system that can result in its failure.

E.g. a misbehaving minister is regarded as a government's Achilles heel and is expected to resign.

The myth: Achilles’ mother, a sea nymph, wanted to protect her son from death, so she put him in the water of the River Styx when he was a baby. Wherever the water covered him would protect him from being killed, but his ankle or heel of the baby where she was holding was not covered with water. Achilles became a great warrior, but he was left unprotected on his heel, which also lead to death when he was shot with an arrow at his vulnerable heel during the Trojan War. (Wöhlche, 2004) , (Fink, 2004)

Contemporary Meaning: a person or thing that joins and deceives a group or organization in order to attack it from the inside.

E.g. older supporters have accused the new leadership of being a Trojan horse that will try to destroy the party from the inside.

The myth: Odysseus, the king of Ithaca and a wise and valiant man, thought up a great plan to take Troy. He had an enormous wooden horse built to make the Trojans believe it was a gift from the Gods. But the wooden horse was hollow on the inside and the best warriors of Sparta climbed in it. The rest of the Greek armies broke the camp and pretended to sail away. The Trojans thought in the way as the Greeks had planned and brought the horse inside the walls. This meant loosing the war because the Greek soldiers came out of the horse at night and opened the doors of the city to let the army come in. (Wöhlche, 2004), (Fink, 2004)

4- Beware of Greeks bearing gifts (idiom)

Contemporary meaning: consider why someone is giving something to you.

The myth: When the Greeks made a hose to cheat the Trojans by making them believe that it was a gift from the gods, one of the Trojans warned them not to believe it and that it might have been a trick played by the Greeks.

E.g. do not trust the horse, Trojans. Whatever it is, I fear the Greeks even when they bring gifts.

5- to work like a Trojan

Contemporary meaning: to work very hard and never give up.

The myth: The Trojans worked very hard and never gave up to defend to defend their country against the Greeks.

E.g. He worked like a Trojan to finish the project on time. 6- a Cassandra (n)

Contemporary meaning: a pessimist, one that predicts misfortune or disaster.

The Myth: Cassandra is one of Priam’s daughters, the king of Troy, and when she was a teenager Apollo fell in love with her. When Apollo expressed his feelings, she demanded the gift of prophecy on return, but when she got the gift, she changed her mind. Apollo was furious at the trick, but the gods cannot take back what they have given, so Apollo kissed her on the lips and said that she was given the gift of prophecy but, because she lied to him, she would foretell the future but would be doomed to have no one believe in her. (Wöhlche, 2004), (Fink, 2004)

E.g. she talked s a Cassandra and led every one to feel pessimistically. 7- Let bygones be bygones (idiom)

Contemporary meaning: to tell someone they should forget about unpleasant things that happened in the past, and especially to forgive and forget something bad that someone has done to them.

E.g. Forget about the argument you two had, just let bygones be bygones and be friends again.

The myth: Patroclus, Achilles’ best friend, was killed by Hector, one of Priam’s sons, which made Achilles furious and swore an oath to take revenge. A great battle occurred between Achilles and Hector and the gods battled each other as well. Athena, the goddess of wisdom, stood by Achilles but Hector was abandoned by Apollo, the god of war. In the end Hector was killed by Achilles and dragged the body of the prince to his tent and threw it next to the body of Patroclus. That night, King Priam of Troy went to the tent of Achilles secretly to beg for the body of his dead son, and said the above idiom: “Let bygones be bygones” (Wöhlche, 2004), (Fink, 2004)

2.2.3. The Myth of Cupid and Psyche

This story about Cupid’s, whose Greek name is Eros, falling in love. He was the son of the goddess of love and beauty, Aphrodite. Cupid was the messenger of love, and it was his job to make people fall in or out of love. If he shot someone with a magic arrow tipped with gold, that person would fall in love with the person he or she saw next and if he used an arrow tipped with lead, that person would refuse to fall in love. Psyche was a beautiful princess and people said that she was more beautiful than Aphrodite. This made her jealous and angry and she sent her son, Cupid to take revenge. When Cupid saw Psyche, he was so shocked by her beauty that he scratched himself with the golden point of his arrow, which caused him to fall deeply in love with her. Without giving her any harm, he left decisively to come back and take her. One evening, while Psyche was walking outside, a gentle wind blew and took her from the earth and carried her away to a palace. They lived there happily for a while, but Cupid never told her his name and never showed his face to his wife. Time passed and Psyche missed her family. She begged her husband to let her two sisters come to visit. When her sisters saw her living conditions, they envied her and talked to her into doubting her husband. They suggested he must be a terrible monster and that was why he did not show his face. Psyche believed in her sisters and put a knife under her bed and waited for her husband to

come. At night when Cupid fell asleep, she got out of bed and lit a candle. She was curious and wanted to see her husband’s face, so she bent over him with the candle in her hand but a drop of hot wax dropped on Cupid’s shoulder. When he awoke he looked at her with anger and sadness and said: “After I left my mother and made you my wife, is this the way you trust me? Love and suspicion cannot live in the same house. So the god of love must go.” Psyche was regretful of what she had done and went to Ceres, the goddess of the earth and the harvest, to ask her what to do. Ceres advised her to go to go to Aphrodite and beg her for forgiveness. Aphrodite told her to complete several seemingly impossible tasks but she completed each task without any difficulty with the help of Cupid and the other gods and goddesses. In the end Cupid flew to Zeus, the god of the gods, to beg him to make his beloved Psyche a goddess. Zeus granted his wish and the couple were soon reunited. In time they had a child whom they named Pleasure. (Schwab, 2004), (Fink, 2004)

Below is a list of lexical items that trace back to the myth above. The meanings of these lexical items have been quoted from Collins Cobuild English Language Dictionary, Cambridge Advanced Learner’s Dictionary, Cambridge International Dictionary of Idioms, Oxford Dictionary of English and Merriam Webster Dictionary.

1- cupidity (noun)

Contemporary meaning: a great desire, especially for money or possessions E.g. Cupidity reach their lowest point in TV give-away shows.

2- erotic (adjective)

Contemporary meaning: related to sexual desire and pleasure

E.g. the play's eroticism shocked audiences when it was first performed. 3- psychiatric (noun)

Contemporary meaning: the part of medicine which studies mental illness

E.g. because he was mentally ill, after many investigations, they put him in a psychiatric hospital.

4- venereal disease (noun)

Contemporary meaning: a disease that is spread through sexual activity with an infected person; a sexually transmitted disease

The myth: The word venereal is derived from Venus which is the Roman name for Aphrodite.

E.g. one of the main problems of the 20th century is the venereal diseases such as aids.

5- Venus (noun)

Contemporary meaning: the planet second in order of distance from the Sun, after Mercury and before the Earth. It is the nearest planet to the Earth.

E.g. the second planet in order of distance from the sun is Venus. 6- psychotic (noun)

Contemporary meaning: any of a number of the more severe mental diseases that make you believe things that are not real.

E.g. His dislike of women bordered on the psychotic. 7- psychedelic (noun)

Contemporary meaning: causing effects on the mind, such as feelings of deep understanding or seeing strong images

E.g. psychedelic drugs 8- aphrodisiac (noun)

Contemporary meaning: something, usually a drug or food, which is believed to cause sexual desire in people

E.g. Are oysters really an aphrodisiac? They say that power is an aphrodisiac. 9- psychologist (noun)

Contemporary meaning: the scientific study of the way the human mind works and how it influences behaviour, or the influence of a particular person's character on their behaviour.

2.3. Comparison of Tour Guide Training in Turkey and other Countries

In this section it is aimed to examine the tour guide training systems abroad and in Turkey. The tour guide training systems in as many countries as possible are examined by using the web to search for information about their tour guide training systems. The World Federation of Tourist Guide Associations (WFTGA), which was founded in 1985 and has more than 88000 members throughout the world, sets one of its aim as to develop international tour guide training, and improve the quality of guiding through education and training. The data about the tour guide education systems in the word is collected from the web sites of WFTGA and the federations of the countries examined, and through emails. While investigating how tourist guides are being trained in the world, it is discovered that there is a variety of ways that are followed by various institutions. It is also seen that in some developed countries licensing is not even required. Some countries such as Australia and most states of the USA do not train the tourist guides, but only apply a test and deliver licenses; yet, there are also many countries such as Greece, Spain and Turkey where tour guide training is compulsory to get licensed. In the following section it is aimed to examine the tourist guide training systems in some countries.

2.3.1. Tourist Guide Training in the USA

The United States does not have a National Plan for tourism. It is handled by individual states and cities. In many localities of the USA tourist guide licensing is not required. The only localities that require licensing in the US are New Orleans, Louisiana; Washington, DC; New York City, New York; Savannah, Georgia; Charleston, South Carolina; Gettysburg Battlefield, Pennsylvania and Vicksburg Battlefield, Mississippi. All of these localities are in the eastern part of the US and therefore licensing is not required anywhere west of the Mississippi River. New Orleans, Louisiana, for instance, is one of only a few cities in the United States that does license guides. The educational requirements are not strenuous. Basically the city charges for testing and if you pass you are required to pay for a drug test and a background test before your license is issued. The test is 150 fill-in-the-blank questions about the History and Culture of New Orleans and the surrounding area.

(Gattuso, (2003). New Orleans, Louisiana- Educational system for Tourist Guides [On-line]. Available: http://wftga.org/page.asp?id=113 [Febraury 10, 2008].)

2.3.2. Tourist Guide Training in Scotland

In Scotland, potential guides must apply to the Scottish Tourist Guides Association. They are interviewed and language screened and then if accepted they go on a 4-day introductory course. They have to do presentations and a written assignment. If they pass that at minimum of 60% they are invited to become Student Associate Members of STGA. They start the course which is run for us by the University of Edinburgh and includes Core Knowledge, Practical Skills and Regional Studies (i.e. Applied core knowledge to different parts of Scotland). The course lasts for 2 years and includes 128 hours core knowledge, 280 hours guiding skills/regional studies - this is a mixture of web based distance learning, tutorials, lectures and field visits including two 7 day extended tours around Scotland and several weekend trips. They are assessed on coach, foot and on site and have to write 4 essays plus a longer project and tour notes. If they pass all this, they apply to sit the STGA membership exam which lasts for 4 days and includes a written exam, a project, oral questions on any area of Scotland, oral questions on practical issues and assessment on coach, site and walk. They are assessed in English but have to do the practical sessions in English and in any language they intend to guide in (whether it is their native language or not) They must pass at 70% and they are then awarded the Blue Badge, a joint STGA, University of Edinburgh Certificate and a Certificate in Scottish Studies (which can count for a degree if they want).

(Newlands, (2003). Scottish Educational system for Tourist Guides [On-line]. Available: http://wftga. org/page. asp?id=111 [February 15. 2008].)

2.3.3. Tourist Guide Training in Greece

In Greece potential guides must get a degree from The School of Tourist Guides, which is a state school in Greece and lasts for two an half years. The candidates have to take oral and written exams at least in one foreign language of their choice. If they pass the language exam, they take written exams in essay, Greek history, Greek geography and an interview. The tourist guide trainees have to take various courses at this school such as Greek and Byzantine history; Prehistoric and Classical archaeology; History of art, architecture and

theatre; Mythology; Geography; Geology, Palaeontology; First Aid and so on. There is also an intense (370 classes) practical training which includes visiting museums and archaeological sites.

(Kalamboukidou, (2003). Greek Educational system for Tourist Guides [On-line]. Available: http://wftga.org/page.asp?id=115 [February20,2008].)

2.3.4. Tourist Guide Training in Iceland

In Iceland potential guides must get a degree from The Iceland Tourist Guide School was founded in 1976. The objective of the school is to train students to become professional tourist guides who meet the industry's standards of excellent quality. The school follows a curriculum that is authorized by the Icelandic Ministry of Education. Entrance requirements for the Iceland Tourist Guide School include three clearly defined criteria. The prospective student must be at least 21 years of age at the start of the course, have university entrance exemption and meet the oral language proficiency standards. Before being admitted, prospective students are interviewed and examined in an oral language test by two examiners. Course duration is one year and includes 444 hours. Exams and field trips are in addition. At the end of the course there is a supervised six-day field trip around Iceland. Subjects include; tourist guiding techniques (presentation skills and group psychology, etc.), geology/geography, history, industries and farming, tourism, society and culture, arts, botany, ornithology, mammals in Iceland, 20 hour first aid course, area interpretation and presentation skills in the student's selected foreign language. Course evaluation is strict. Students must pass all individual subject exams with a mark of minimum 7 out of 10. At the end of the first term, students have to pass a language exam that covers the content of the subjects taught in the first term. At the end of the second term, students have to pass an oral language exam covering the subjects of the area interpretation in the classroom, and pass two practical oral exams in a coach.

(Valsson, (2004). Icelandic Educational system for Tourist Guides [On-line]. Available: http://wftga.org/page.asp?id=134[February20,2008].)

2.3.5. Tourist Guide Training in London

There has been a training course for people wishing to become professional tourist guides in London for over 50 years. The course, which is executed by The Guild of

Registered Tourist Guides and is accredited by the Institute of Tourist Guiding, prepares student guides for the Institute of Tourist Guiding examinations. On passing these written and practical examinations, the guide is awarded a Blue Badge, which is the industry recognised symbol of professionalism in tourist guiding.

During the course the students study a wide background to Britain, London knowledge, guiding techniques, which cover communication and presentation skills for guiding on foot, on site and from a moving vehicle, and business skills, that is learning to work as a self-employed guide within the tourist industry.

Subjects covered include: history, geography and geology, agriculture and countryside, law, English literature, visual and performing arts, monarchy, government, tourism, sport, industry and commerce, finance, various galleries and museums in London, religion, architecture, current affairs and tour planning and problem solving.

It is essential for students to have regular access to a computer, email and a good printer as many handouts for lectures and communications regarding changes or additions to the course are sent out electronically.

The course is designed to be part-time, with lectures and practical training sessions outside normal office hours. There are also practical training sessions and visits most Saturdays. These sessions are an essential part of the course. A training course prospectus is enclosed of London Blue Badge Tourist Guide Training Course 2008 in the appendices.

(Institute of Tourist Guiding, (2008). http://www.itg.org.uk/course_details.asp?courseid= 2&listtype=OPhttp://www.blue-badge-guides.com/pdf/LondonBlueBadgeCourse Prospectus 2008.pdf)

2.3.6. Tourist Guide Training in Turkey

In Turkey there are four different courses that train tour guides. The Ministry of Tourism executes two courses: a local one and a national one. The first is a three month course and the graduates get a local tourist guide licence with which they are only permitted to do their job in a specific area. The latter is a six month course and the guides trained at these courses are licensed to guide in whole country. Two different courses, a two year diploma course and a four year university degree course, are run by a number of private and state universities. Basically, the course contents are the same at the courses. (Kuşluvan, (2002). Tour Guiding, Tourism Geography of Turkey, Archaeology, Art History, Mythology, Religion, Folklore and Sociology, Turkish History, Turkish Literature and First Aid are

common subjects thought at these courses. Because of the length of the course these subjects, compared with the university courses, are superficially thought on the courses of the ministry. Language training on these courses differs too. The courses of the ministry do not contain any language courses, but to enrol to these courses the applicants have to pass a language in essay. To get the right to register for the courses of the universities the students have to pass the YDS (University Entrance Foreign Language Exam). The university courses contain an immense language training which ranges from four to ten classes per week each term. All graduates of all these courses have to pass the KPDS (the Turkish state’s foreign language exam), which is a multiple test and have to get minimum seventy out of hundred questions. Students might also enter a written exam opened by the ministry irregularly. Tourist Guide Training Programme Ankara University Vocational School of Higher Education id enclosed in Appendices. (Özbay, (2007). Türkiye’de Profesyonel Turist Rehberliği [On-line]. Available: http://www. tureb.net/GenelBilgiler.asp?id=84 [March 1, 2008])

CHAPTER 3

METHODOLOGY

The fact that there are almost no published ESP (English for Specific Purposes) teaching materials to use in the English classes of Tourist Guiding courses makes the language teachers face problems in fulfilling his/her responsibility. This study aims to lay out that Greek and Roman Mythology can be used as teaching materials in English classes of Tourist Guiding Programmes. In this study, a short course of 18 English lessons is developed and evaluated for using Greek and Roman mythological stories as teaching materials, which are supported by appropriate exercises and activities. The subjects of the research were 1st year students of Tourist Guiding Department of Selçuk University Beyşehir Vocational School of Higher Education. Before the application of these lessons, a questionnaire had been administered to the same group to find out the expectations and the needs of the students. After this short course, a second questionnaire is applied to the students to make it possible to compare the results of the first questionnaire and the second one. The research questions of both questionnaires were adopted from Ridgeway, C. (2003). Vocabulary for Tour Guiding

through Readings. Unpublished doctoral dissertation, Hacettepe University, Ankara, Turkey. This chapter details this process and concludes the results of this research.

3.1. Aims of the First Questionnaire

In order to take the course on tourist guiding, students have to do a test of multiple choices in the YDS exam (University Entrance Exam for Foreign Language Students). The students have studied general English to an advanced level and most of them have made more than 60 questions out of 100 questions. The problem is that students only get prepared to that test and make almost no progress in speaking, listening and writing; they are very well at grammar, vocabulary and reading though. The aim of the questionnaire is to obtain the expectations and needs of the tourist guiding students for the English classes at the university course. It is also aimed to find out whether these students really want to be guides or not to get some idea about their motivation.

3.2. Hypotheses of the First Questionnaire

It is thought that the questionnaire will reveal the following hypotheses:

1. The students who have chosen tourist guiding programme had tried to study to the teacher training programmes but, because they did not well enough at the University Entrance Exam they were obliged to choose the tourist guiding programme.

2. The students do not think of being a tourist guide because they still have the ambition of being an English teacher.

3. The students are in need of and have expectations for improving their listening, speaking, vocabulary and pronunciation; and want fewer classes on grammar, reading, writing and translation.

3.3. Data Analysis of the First Questionnaire

The data is analyzed by using the “Statistical Package for the social Sciences” SPSS version 12.0. The frequency percentage for each question is shown on tables. The applied questionnaire is enclosed in the appendixes. The results of each question are discussed separately.

Table 1 shows the frequencies for question 1. Out of total 33 students, 7 students (51,5%) have said they want to be tourist guides, 9 students (27,3%) have said they are not sure and 7 students (21,2%) have said they do not want to be guides. That means 48.5% of the students either do not want to be guides or have not decided yet.

Frequency Percent Valid Percent

Cumulative Percent

Yes, I want to be a guide. 17 51,5 51,5 51,5

I am not sure if I want to be

guide or not. 9 27,3 27,3 78,8

No, I do not want to be a guide.

7 21,2 21,2 100,0

Total 33 100,0 100,0

Table 1 Do you want to be a tourist guide?

Table 2 shows the frequencies for question 2. Out of total 33 students, 20 students (60,6%) have said they would prefer being a teacher and 13 students (39,4%) have said they would prefer being a tourist guide.

Frequency Percent

Valid Percent

Cumulative Percent I would prefer being an

English teacher 20 60,6 60,6 60,6

I would prefer being a tourist

guide 13 39,4 39,4 100,0

Total 33 100,0 100,0

Table 2 Would you prefer being an English teacher or a tourist guide?

Table 3 shows the frequencies for question 3. Out of 33 students, only 2 said they have worked as a tour guide before and 31 have never worked as a tourist guide.

Frequency Percent Valid Percent Cumulative Percent Yes 2 6,1 6,1 6,1 No 31 93,9 93,9 100,0 Total 33 100,0 100,0

Table 3 Have you ever worked as a tourist guide?

Table 4 shows that 8 students out of 33 are male and 25 female.

Frequency Percent Valid Percent

Cumulative Percent Male 8 24,2 24,2 24,2 Female 25 75,8 75,8 100,0 Total 33 100,0 100,0

Table 4 What is your gender?

Table 5 shows that 10 students are either at the age of 19 or younger, 19 students are between the ages 20 - 22 and four students are either 23 or older.

How old are you? Frequency Percent

Valid Percent Cumulative Percent I am 19 or younger 10 30,3 30,3 30,3 I am between 20-22 19 57,6 57,6 87,9 I am 23 or older 4 12,1 12,1 100,0 Total 33 100,0 100,0

Table 5 How old are you?

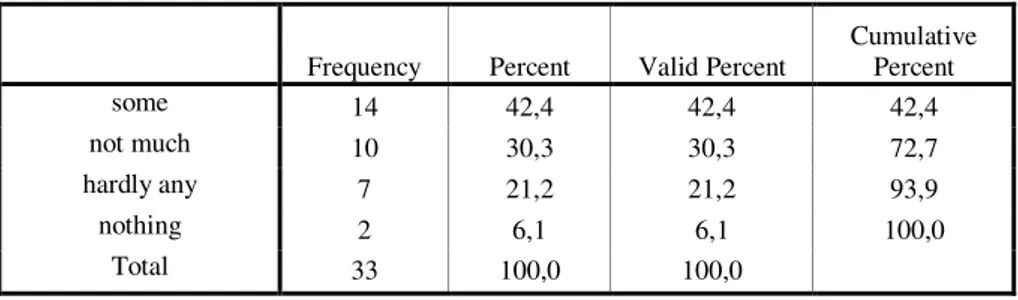

Table 6 shows how much students already know about Greek and Roman Mythology. Fourteen students out of 33 said they know some about mythology, 10 students said they do

not know much about it, 7 said they almost know nothing about it and 2 said the know completely nothing.

Frequency Percent Valid Percent

Cumulative Percent some 14 42,4 42,4 42,4 not much 10 30,3 30,3 72,7 hardly any 7 21,2 21,2 93,9 nothing 2 6,1 6,1 100,0 Total 33 100,0 100,0

Table 6 How much do you know about mythology?

Table 7 shows the frequencies for question 7. Out of 33 students, 2 students (6,1%) said they expect and need to study grammar a lot. 19 students (57,6%) said they need and expect some grammar. 10 students (30,3%) said they do not need and do not expect grammar to cover the English classes. 2 students (6,1%) said they hardly need any grammar.

Frequency Percent Valid Percent

Cumulative Percent a lot 2 6,1 6,1 6,1 some 19 57,6 57,6 63,6 not much 10 30,3 30,3 93,9 hardly any 2 6,1 6,1 100,0 Total 33 100,0 100,0

Table 7 How much grammar do you expect and think you need to cover your English classes?

Table 8 shows the frequencies for question 8. Out of 33 students 25 (75,8%) said they expect and need to study vocabulary a lot and 8 students (24,2%) said they need and expect some vocabulary. No student said they do not need and expect much or they need and expect hardly any vocabulary to cover the English classes.

Frequency Percent Valid Percent

Cumulative Percent

a lot 25 75,8 75,8 75,8

some 8 24,2 24,2 100,0

Total 33 100,0 100,0

Table 8 How much Vocabulary do you expect and think you need to cover your English classes?

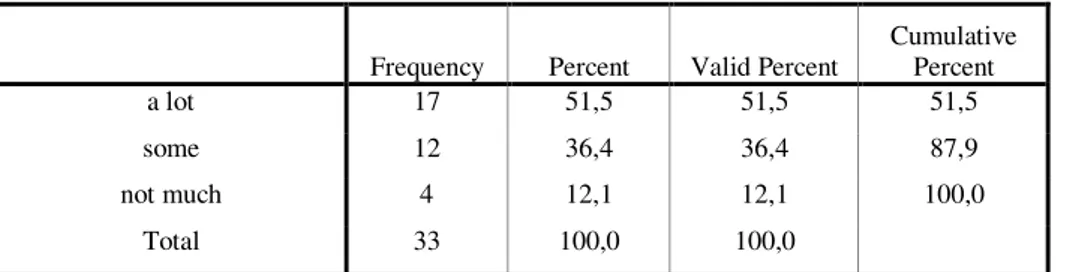

Table 9 shows the frequencies for question 9. Out of 33 students 17 (51,5%) said they expect and need to study reading a lot and 12 students (36,4%) said they need and expect

some reading. 4 students (12,1%) said they do not need and expect much and no students expect hardly any vocabulary to cover the English classes.

Frequency Percent Valid Percent

Cumulative Percent a lot 17 51,5 51,5 51,5 some 12 36,4 36,4 87,9 not much 4 12,1 12,1 100,0 Total 33 100,0 100,0

Table 9 How much Reading do you expect and think you need to cover your English classes?

Table 10 shows the frequencies for question 10. Out of 33 students 6 (18,2%) said they expect and need to study writing a lot and 13 students (39,4%) said they need and expect some writing. 12 students (36,4%) said they do not need and expect much and 2 students (6,1%) expect hardly any writing to cover the English classes.

Frequency Percent Valid Percent

Cumulative Percent a lot 6 18,2 18,2 18,2 some 13 39,4 39,4 57,6 not much 12 36,4 36,4 93,9 hardly any 2 6,1 6,1 100,0 Total 33 100,0 100,0

Table 10 How much Writing do you expect and think you need to cover your English classes?

Table 11 shows the frequencies for question 11. Out of 33 students 18 (54,5%) said they expect and need to study listening a lot and 12 students (36,4%) said they need and expect some listening. 3 students (36,4%) said they do not need and expect much and no student expect hardly any listening to cover the English classes.

Frequency Percent Valid Percent

Cumulative Percent a lot 18 54,5 54,5 54,5 some 12 36,4 36,4 90,9 not much 3 9,1 9,1 100,0 Total 33 100,0 100,0

Table 11 How much Listening do you expect and think you need to cover your English classes?

Table 12 shows the frequencies for question 12. Out of 33 students 25 (78,5%) said they expect and need to study speaking a lot and 7 students (21,2%) said they need and expect

some speaking. 1 student (3,0%) said they do not need and expect much and no student expect hardly any speaking to cover the English classes.

Frequency Percent Valid Percent

Cumulative Percent a lot 25 75,8 75,8 75,8 some 7 21,2 21,2 97,0 not much 1 3,0 3,0 100,0 Total 33 100,0 100,0

Table 12 How much Speaking do you expect and think you need to cover your English classes?

Table 13 shows the frequencies for question 13. Out of 33 students 23 (69,7%) said they expect and need to study speaking a lot and 6 students (18,2%) said they need and expect some speaking. 4 students (12,1%) said they do not need and expect much and no student expect hardly any speaking to cover the English classes.

Frequency Percent Valid Percent

Cumulative Percent a lot 23 69,7 69,7 69,7 some 6 18,2 18,2 87,9 not much 4 12,1 12,1 100,0 Total 33 100,0 100,0

Table 13 How much Pronunciation do you expect and think you need to cover your English classes?

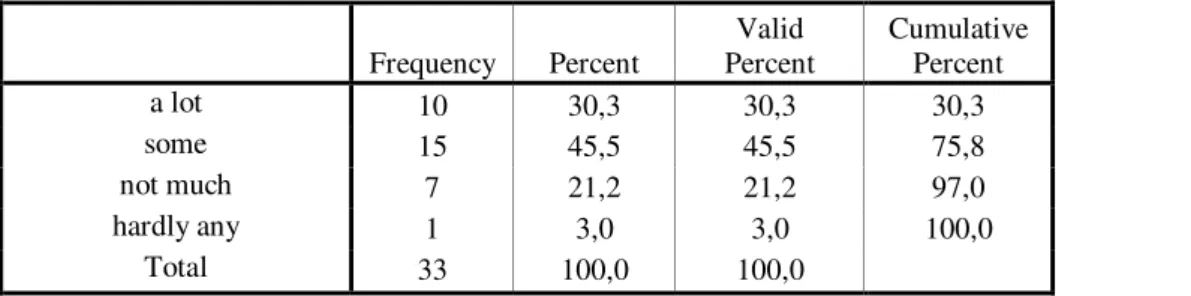

Table 14 shows the frequencies for question 14. Out of 33 students 10 (30,3%) said they expect and need to study speaking a lot and 15 students (45,5%) said they need and expect some speaking. 7 students (21,2%) said they do not need and expect much and only one student (3,0) expect hardly any speaking to cover the English classes.

Frequency Percent Valid Percent Cumulative Percent a lot 10 30,3 30,3 30,3 some 15 45,5 45,5 75,8 not much 7 21,2 21,2 97,0 hardly any 1 3,0 3,0 100,0 Total 33 100,0 100,0

Table 14 How much Translation do you expect and think you need to cover your English classes?

3.4. Results of the First Questionnaire

It was hypothesized that the students of tourist guiding programmes of Beyşehir Vocational School of Higher Education are disinclined to study on this programme because their ambition was being an English teacher rather than a tourist guide, and that they still have this ambition and chose tourist guiding programme because these students had failed in the YDS exam and did only well enough to study tourist guiding. The frequencies of question 1 show us that 51,5% of the students say they want to be tourist guides, 27,3% of them said they are not sure and 21,2% said they do not want to be tourist guides. The total frequency of the students who have said they want to be guides and they have not decided yet is 48,5%. This shows us that almost half of the students have not the ambition of being a tourist guide. The frequencies of table 2 show us that 60,6% of the students still prefer being an English teacher to tourist guiding, which supports the validity of the results of question 1. The frequencies of question number 5 show us that 30,3% of the students are either 19 years old or younger, which should be normally the age of university first class students. It is clear that 69,7% of the students have entered the Turkish University Entrance Exam more than once. These results show us that almost half of the students of tourist guiding programmes of Selçuk University Beyşehir Vocational School of Higher Education are not motivated for working as tourist guides after their graduation. This outcome lays out that the hypotheses that the students are unwilling to study on this programme and that they still have the ambition of being an English teacher comes true.

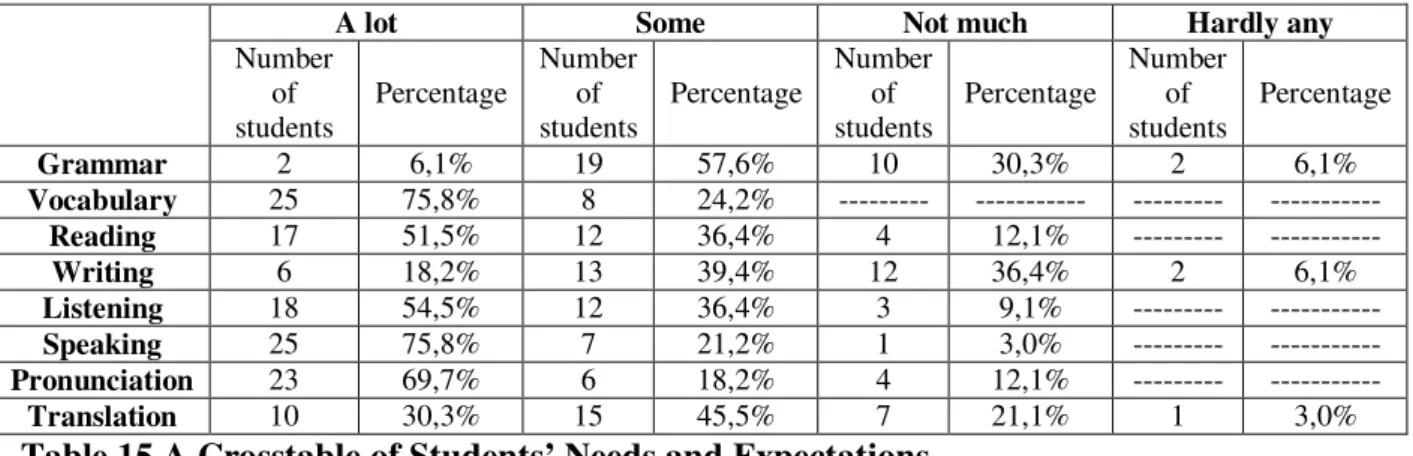

Question 7,8,9,10,11,12,13 and 14 are about students’ expectations and needs in regard to English classes. Table 15 is a crosstable of these questions.

A lot Some Not much Hardly any

Number of students Percentage Number of students Percentage Number of students Percentage Number of students Percentage Grammar 2 6,1% 19 57,6% 10 30,3% 2 6,1% Vocabulary 25 75,8% 8 24,2% --- --- --- --- Reading 17 51,5% 12 36,4% 4 12,1% --- --- Writing 6 18,2% 13 39,4% 12 36,4% 2 6,1% Listening 18 54,5% 12 36,4% 3 9,1% --- --- Speaking 25 75,8% 7 21,2% 1 3,0% --- --- Pronunciation 23 69,7% 6 18,2% 4 12,1% --- --- Translation 10 30,3% 15 45,5% 7 21,1% 1 3,0%

For speaking and vocabulary, “a lot” scored the highest frequency; 25 out of 33 students said they expect and think are in need of vocabulary and speaking to cover their English classes “a lot”. For speaking 7 students (21,2%) and for vocabulary 8 ( 24,2%) students said “some”. Only one student preferred “not much” for speaking and “not much” was not chosen for vocabulary. There are not any students who chose “hardly any” for neither vocabulary nor speaking. It it clear that students expect and think they are in need to have reading and vocabulary classes the most. For pronunciation, “a lot” was chosen by 23 students (69,7%), “some” was preferred by 6 students (18,2%), “not much” by 4 with the percentage of (12,1%9 and no student chose “hardly any”. For listening, “a lot” was chosen by 18 students (54,5%), “some” was preferred by 12 students (36,4%), “not much” by 3 with the percentage of (9,1%) and no student chose “hardly any”. According to these frequencies the language skills that students expect and think to cover their English classes can be put in range as follows: 1- Vocabulary, 2- Speaking, 3- Pronunciation, and 4- Listening. This range supports the hypotheses put forward initially.

Reading comes after the above mentioned skills. For reading, “a lot” scored the highest frequency; 17 students (51,5%) marked reading “a lot”, 12 students (36,4%) said “some”, 4 students (12,1%) said “not much” and no student preferred “hardly any”. It was hypothesized that students would say they are not in need of reading classes, but these frequencies show us that this hypothesis did not come true, because 29 students (87,9%) said they need reading classes either “a lot” or “some”.

Translation, writing and grammar are less marked than the others. For translation, “some” scored the highest frequency with the percentage of 15 (45,5%), 10 students (30,3%) marked “a lot”, 7 students (21,1%) marked “not much” and 1 student (3,0%) said “hardly any”. Writing comes next: 13 students (39,4%) marked “some”, 12 students (36,4%) marked “not much”, 6 students (18,2%) marked “a lot” and 2 students (6,1%) said “hardly any”. Grammar is the least marked subject: 19 students (57,6%) marked “some”, 10 students (30,3%) marked “not much”, 2 students (6,1%) marked “a lot” and 2 students (6,1%) said “hardly any”. These frequencies show us that the range of less marked subject is as follows: Translation, Writing and Grammar.

This result shows us that the the students expect to have more classes on listening, speaking, vocabulary, pronunciation and reading; and want fewer classes on grammar, writing and translation.