Research Article

Comparison of the effectiveness of two different interventions

to reduce preoperative anxiety: A randomized controlled

study

Nurcan Ertuğ,RN,PhD,1† Özge Ulusoylu,BSN,2Ayça Bal,BSN3and Hazal Özgür,BSN4

1School of Nursing, Ufuk University,2Etimed Hospital,3LÖSANTE Children’s and Adult Hospital and4Başkent University

Hospital, Ankara, Turkey

Abstract This study was conducted to determine and compare the effectiveness of nature sounds and relaxation exercises for reducing preoperative anxiety. A repeated measures randomized controlled trial design was used. We divided 159 preoperative patients into three groups: nature sounds (n = 53), relaxation exercises (n = 53), and control groups (n = 53). We evaluated anxiety using the visual analog scale and state anxiety inventory scores immediately before, immediately after, and 30 min after interventions in nature sounds and relaxation exercises groups, and silent rest in the control. We found no differences between the measurement values in the intervention groups, but we did observe a difference between the intervention and control groups. The two interventions were similarly effective in reducing preoperative anxiety. These simple and low-cost interventions can be used to reduce preoperative anxiety in surgical clinics.

Key words nature sounds, nursing, preoperative anxiety, randomized controlled trial, relaxation exercises.

INTRODUCTION

Anxiety affects people physiologically, psychologically, and behaviorally. Physiologically, anxiety can cause reactions such as increased heart rate, muscle tension, nausea, mouth dryness, and sweating. Anxiety may also have psychological effects, such as apprehension and uneasiness. Behavioral effects include the inability to cope with everyday struggles or to express oneself (Bourne, 2010).

Preoperative anxiety can have many causes, such as: fear of death, pain, nausea, and vomiting; an inability to recover from anesthesia; dependence on others during the postoperative period; loss of self-control during anesthesia; separation from loved ones; and uncertainty (McArthur-Rouse & Collins, 2007; Indratula et al., 2013). This form of anxiety plays a crucial role in the postoperative process (Munafo & Stevenson, 2001) and leads to the increased use of postoperative analgesics (Jamison et al., 1993; Pan et al., 2005).

Several studies have found a significant relationship between preoperative anxiety and postoperative pain (Özalp et al., 2003; Feeney, 2004; Granot & Ferber, 2005). Kain et al. (2000a) observed that patients with higher levels of preoperative anxiety had more postoperative acute pain. Another study by Kain et al. (2000b) reported that patients who took preopera-tive antianxiety medication experienced less postoperapreopera-tive acute pain. Ali et al. (2014) determined that patients with

higher levels of preoperative anxiety tended to take longer to recover from anesthesia, thus indicating a negative effect on postoperative pain management.

Some evidence indicates that preoperative anxiety is related to postoperative nausea and vomiting and increased cost. Van den Bosch et al. (2006) and Roh et al. (2014) reported a positive relationship between preoperative anxiety and postoperative nausea. Total joint arthroplasty patients with higher levels of preoperative anxiety and depression have been found to exhibit higher rates of postoperative complications, leading to higher costs (Rasouli et al., 2016). All of these studies indicate that preoperative anxiety has a negative effect on the postoperative period and that reducing preoperative anxiety could reduce negative outcomes.

Researchers have shown increasing interest in the use of non-pharmacological interventions, such as preoperative visits, music, acupressure, and hand massage to reduce preoperative anxiety in surgical settings (Valiee et al., 2012; Brand et al., 2013; Thompson et al., 2014; Bagés Fortacín et al., 2015). One of the most commonly used interventions to reduce anxiety, muscle relaxation through exercise, has been shown to decrease sympathetic stimulation of the hypothalamus with the neuromuscular, cardiovascular, and respiratory systems in the most affected areas (Roykulcharoen & Good, 2004; Pelka et al., 2017). Progressive relaxation consists of voluntary and orderly relaxation and contraction of the muscles until all muscle groups are relaxed. All relaxation processes ensure rhythmic breathing, the alleviation of muscle strain, and increased patient awareness. The patient works the muscle groups starting with the hands, followed by the arms, shoulders,

Correspondence address: Nurcan ERTUĞ, Yunus Emre Mah. Takdir Cad. No:5, Etlik, Yenimahalle, Ankara, Turkey. Email: ertugnurcan@gmail.com

Received 11 July 2016; revision 14 December 2016; accepted 14 January 2017

pectorals, legs, and feet (Demiralp & Oflaz, 2007). Relaxation exercises have been reported to reduce anxiety when used in hormonal therapy, ectopic pregnancy, arthroplasty, abdominal surgery, radical mastectomy, and pulmonary arterial hyperten-sion (Pan et al., 2012; Zhao et al., 2012; Büyükyılmaz & Aştı, 2013; Rejeh et al., 2013; Li et al., 2015; Zhou et al., 2015). However, we found no research on the effects of relaxation exercises on preoperative anxiety.

Sounds and music stimulate the involuntary centers in the central nervous system. They are initially transmitted to the higher levels of the brain, where they influence emotional and abstract thought before eliciting a physiological response (Davis & Nussbaum, 2008). Nature sounds have been shown to improve vital signs, decrease sympathetic activity, and increase parasympathetic activity (Alvarsson et al., 2010; Annerstedt et al., 2013). Alvarsson et al. (2010) reported that nature sounds enabled faster physiological recovery in persons exposed to physiological stress. Other studies have reported that listening to nature sounds during the intra-operative period resulted in lower heart rate and blood pressure (Tsuchiya et al., 2003; Arai et al., 2008). Nature sounds have also been found to decrease pulse rate, muscle tension, and stress in healthy volunteers (Largo-Wight et al., 2016). Studies have found evidence to indicate that nature sounds reduce anxiety in patients undergoing sigmoidoscopy or mechanical ventilation and those being weaned from mechanical ventilation (Lembo et al., 1998; Saadatmand et al., 2013; Aghaie et al., 2014).

In our literature search, we only identified one other study on the effects of nature sounds on preoperative anxiety. Cullum (1997) sampled a group of 15 patients who listened to nature sounds before surgery and compared them to a control group with the same number of patients who listened to instrumental music. The nature sounds group had lower preoperative anxiety, but the sample size used was too small to make such a deduction. We conclude that the effectiveness of relaxation exercises and nature sounds in reducing preoperative anxiety is not well understood. Both of these non-pharmacological interventions are easy to use and inexpensive with no adverse effects. We therefore evaluated the effectiveness of these interventions in reducing preoperative anxiety in this randomized study.

Study Aim

This study determined and compared the effectiveness of nature sounds and relaxation exercises in reducing preopera-tive anxiety.

Hypothesis

Patients who listen to nature sounds or perform relaxation exercises will have lower anxiety scores than patients who only rest silently during the preoperative period.

METHOD

Design

We used a repeated measures randomized controlled trial design in this study, which involved two intervention groups

(nature sounds and relaxation exercises) and a control. The first intervention group of patients listened to nature sounds, the second performed relaxation exercises, and the control patients were only exposed to silence in their rooms. A pilot study was conducted withfive patients from each group, and no changes in data collection, intervention, or content were deemed necessary.

Setting and participants

The study was conducted at the surgical clinics of a university hospital in Ankara, Turkey, between January and May 2014. The patients stayed in single rooms. A pilot study with 131 patients determined that a sample size of 159 patients would be necessary using power analysis withα = 0.05 and β = 0.20. A total of 159 patients who were about to undergo planned surgery with general anesthesia were randomly divided into three groups: (i) nature sounds (n = 53), (ii) relaxation exercises (n = 53), and (iii) a control (n = 53). Permuted-block randomi-zation with sealed envelopes was used to randomly assign the patients to the three groups while ensuring a balanced distribu-tion. To avoid bias, these envelopes were prepared by a person who was not involved in the study. Participants who met the following criteria were eligible for the study: (i) 18 years of age or older, (ii) able to communicate in Turkish, (iii) with no hearing impairment, and (iv) with no cognitive impairment.

Data Collection Tools

Patients

’ demographic data and clinical characteristics

Demographic data were collected by consulting patient medical records and by querying the patients themselves. The demographic information questionnaire included questions about age, gender, ethnic origin, educational level, extent of surgery, past surgical history, past hospitalization, and other information.

State Anxiety Inventory (SAI)

Patients’ state of anxiety was measured using the Turkish version of the State Anxiety Inventory (SAI). Öner and LeCompte (1983) tested its validity and reliability in Turkish and have granted permission for the inventory to be used in research studies. This inventory determines a person’s feel-ings at a certain time and condition. It contains 20 items and uses a four-point Likert scale: 1, not at all; 2, somewhat; 3, moderately so; and 4, very much so. Patients were re-quested to choose one of the four options for each of the 20 items. A minimum of 20 and a maximum of 80 points can be obtained from this inventory. High scores indicate high anxiety levels.

Visual Analog Scale (VAS)

In addition to the SAI, the Visual Analog Scale (VAS) was used to determine the patients’ anxiety levels. The VAS is widely used to determine the existence of symptoms and their severity. This scale is in the public domain, and we therefore used it without permission (Burckhardt & Jones, 2003). The VAS

consists of a 10 cm line where one end indicates the absence of anxiety and the other indicates severe anxiety. The scale can be used vertically or horizontally; in this study, we used a vertical line (Pritchard, 2010).

Data Collection

The investigators reviewed patient records and identified the patients who would undergo surgery the following day. On the day of surgery, the investigators explained the study objective to the patients and determined whether they were eligible. Eligible patients were randomly assigned to one of the nature sounds, relaxation exercises, and control groups. Demographic and clinical data were collected from the patients and recorded in the data collection tool. These interventions did not harm or compromise the patients in any way.

The VAS and SAI were used to determine the base anxiety levels in all three groups. In the nature sounds group, the patients were requested to choose from bird, rain, river, waterfall, or forest sounds to listen via earphones from a music player for 20 min at a sound level that they were comfortable with. Disposable earphone covers were used to ensure patient hygiene. In the relaxation exercises group, the exercises were undertaken in the patients’ own rooms and beds. Starting with the hands and ending at the feet, relaxation exercises included contraction and relaxation of the large muscle groups. The investigator demonstrated the exercises and the patients were asked to repeat them. The contraction and relaxation of the large muscle groups from the head to the feet lasted 10 min, consisting of two sets offive min each. The optimum duration has previously been suggested as 10–20 min (Roykulcharoen & Good, 2004; Rejeh et al., 2013). In the control group, the patients simply rested silently for 20 min, and their family

members and visitors were not allowed to enter the room during this period. The door was kept closed, and a“do not disturb” sign was placed for all three groups (Fig. 1).

The second set of measurements was conducted after 20 min of listening to the sounds in the nature sounds group, 10 min of exercise in the relaxation exercises group, and 20 min of quiet rest in the control group. Subsequently, the sign on the door was removed, and the patients were given 30 min of free time to spend with their relatives in their rooms. Their anxiety levels were measured again 30 min after the second measurement to determine the long-term effects of the intervention.

Ethical Consideration

We obtained research ethics committee approval from the Turgut Özal University Research Ethics Committee and writ-ten permission from the hospital. We then collected signed in-formed consent forms from the patients after explaining the purpose of the study. The patients were told that participation was voluntary, personal information would be kept confiden-tial, and they could withdraw from the study at any time.

Data Analysis

We used SPSS version 21.0 (IBM Corporation, Armonk, NY, USA) for data analysis. The chi-square test was used to eval-uate the homogeneity of the patients in the groups. Descrip-tive statistics are presented with the arithmetic mean and standard deviation. One-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) was performed to compare the anxiety scores of the groups by measurement time. The independent t-test and one-way ANOVA were used to specify the effects of the independent variables. Anxiety scores within a group were compared with

the repeated-measures ANOVA. Post hoc analysis was performed to determine the differences between the groups. A P value < 0.05 was accepted as statistically significant, while the significance level for the repeated-measures ANOVA was P≤ 0.016.

RESULTS

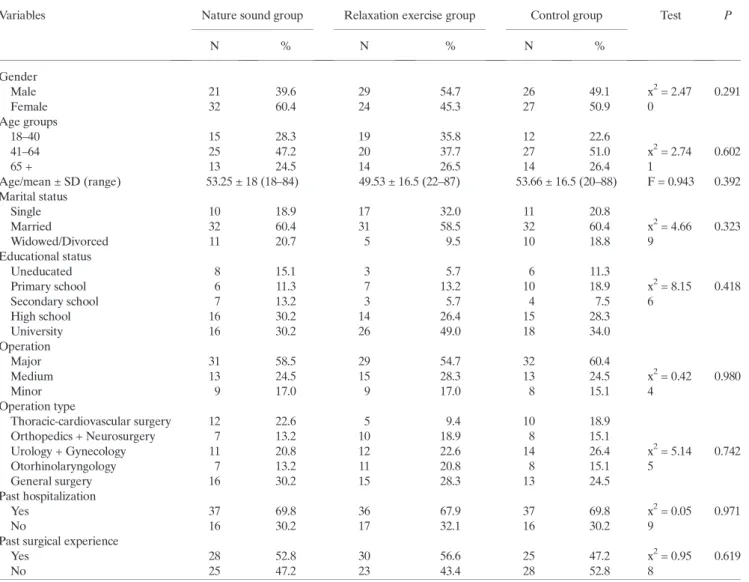

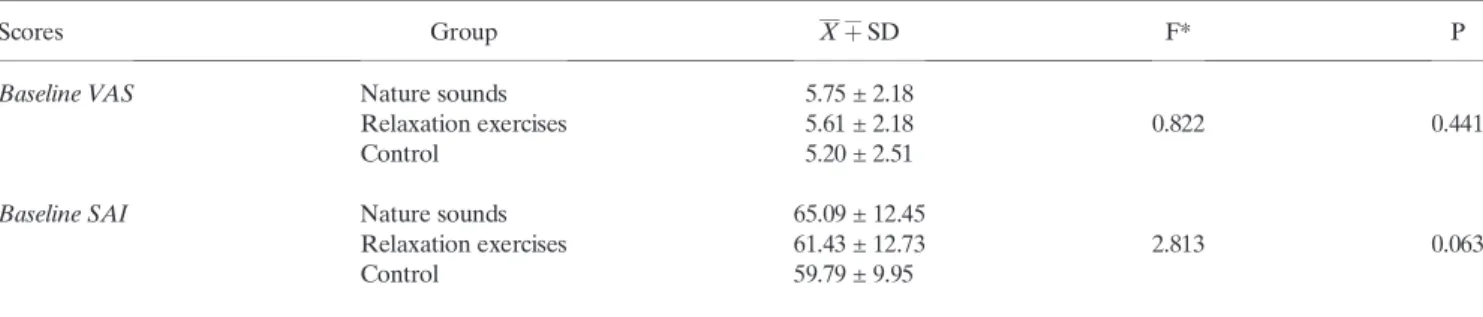

The sociodemographic and clinical characteristics of the patients are presented in Table 1. The mean age was 53.25 ± 18 years in the nature sounds, 49.53 ± 16.5 years in the relaxation exercises, and 53.66 ± 16.5 in the control group. More than half of the patients were married. Sixty percent of the participants in the nature sounds group were women, 45.3% in the relaxation exercises, and 50.9% in the control group. There was no statistically significant difference in terms of demographic and clinical characteristics (gender, age, marital status, educational level, type of surgery and whether it was major or minor, past surgical history, and past hospitalization) (P > 0.05) between the groups. Base VAS

scores in the nature sounds, relaxation exercises, and control groups were 5.75 ± 2.18, 5.61 ± 2.18, and 5.20 ± 2.51, respec-tively, as shown in Table 2. Base SAI scores were 65.09 ± 12.45, 61.43 ± 12.73, and 59.79 ± 9.95, respectively, as shown in Table 2. There was no statistically significant difference in the VAS (F = 0.822, P = 0.441) or SAI (F = 2.813, P = 0.063) scores (F = 2.813, P = 0.063) between the groups.

As shown in Figure 2, VAS scores immediately after and 30 min after the intervention were lower in the nature sounds and relaxation exercises groups than in the control (3.10 ± 1.68, 3.28 ± 1.80, and 5.44 ± 2.66, respectively; F = 4.611, P = 0.011). Post hoc analysis also revealed that the control group had higher VAS scores (P < 0.016). No statistically significant difference between the nature sounds and relaxation groups was observed (P = 0.894). The hypothe-sis was therefore accepted.

As shown in Figure 3, SAI scores measured 30 min after the intervention were also lower in the nature sounds and relaxation groups (P< 0.01); however, there was no statistically

Table 1. Patients’ sociodemographic and clinical characteristics

Variables Nature sound group Relaxation exercise group Control group Test P

N % N % N % Gender Male 21 39.6 29 54.7 26 49.1 x2= 2.47 0.291 Female 32 60.4 24 45.3 27 50.9 0 Age groups 18–40 15 28.3 19 35.8 12 22.6 41–64 25 47.2 20 37.7 27 51.0 x2= 2.74 0.602 65 + 13 24.5 14 26.5 14 26.4 1 Age/mean ± SD (range) 53.25 ± 18 (18–84) 49.53 ± 16.5 (22–87) 53.66 ± 16.5 (20–88) F = 0.943 0.392 Marital status Single 10 18.9 17 32.0 11 20.8 Married 32 60.4 31 58.5 32 60.4 x2= 4.66 0.323 Widowed/Divorced 11 20.7 5 9.5 10 18.8 9 Educational status Uneducated 8 15.1 3 5.7 6 11.3 Primary school 6 11.3 7 13.2 10 18.9 x2= 8.15 0.418 Secondary school 7 13.2 3 5.7 4 7.5 6 High school 16 30.2 14 26.4 15 28.3 University 16 30.2 26 49.0 18 34.0 Operation Major 31 58.5 29 54.7 32 60.4 Medium 13 24.5 15 28.3 13 24.5 x2= 0.42 0.980 Minor 9 17.0 9 17.0 8 15.1 4 Operation type Thoracic-cardiovascular surgery 12 22.6 5 9.4 10 18.9 Orthopedics + Neurosurgery 7 13.2 10 18.9 8 15.1 Urology + Gynecology 11 20.8 12 22.6 14 26.4 x2= 5.14 0.742 Otorhinolaryngology 7 13.2 11 20.8 8 15.1 5 General surgery 16 30.2 15 28.3 13 24.5 Past hospitalization Yes 37 69.8 36 67.9 37 69.8 x2= 0.05 0.971 No 16 30.2 17 32.1 16 30.2 9

Past surgical experience

Yes 28 52.8 30 56.6 25 47.2 x2= 0.95 0.619

No 25 47.2 23 43.4 28 52.8 8

significant difference between these two groups (P = 0.870), supporting both our hypotheses.

Independent variables such as age, gender, marital status, educational level, surgery type and whether it was major or minor, past surgical history, and past hospitalization had no effect on preoperative anxiety level in any of the groups.

Nature sounds and relaxation exercises did not harm any of the patients and instead helped to reduce their preoperative anxiety.

Correlations between the VAS and SAI scores were analyzed and their values compared according to the time of measurement (r = 0.608, P = 0.000; r = 0.570, P = 0.000; r = 0.733, P = 0.000, respectively). A strong and positive rela-tionship between the VAS and SAI scores was found according to Pearson correlation analysis. The VAS and SAI results were consistent with similar values representing anxiety levels.

DISCUSSION

This study determined and compared the effectiveness of nature sounds and relaxation exercises for reducing preoperative anxiety. Randomized controlled studies have previously reported that nature sounds and relaxation exercises are similarly effective in lowering anxiety levels in patients prior to surgery. Both techniques decrease sympathetic activity and increase parasympathetic activity, thereby improving vital signs, relaxing muscles, and reducing anxiety (Davis & Nussbaum, 2008; Alvarsson et al., 2010; Annerstedt et al., 2013). Nature sounds have been found to reduce anxiety in patients undergoing sigmoidoscopy and mechanical ventilation or in patients being weaned from mechanical ventilation (Lembo et al., 1998; Saadatmand et al., 2013; Aghaie et al., 2014). Cullum’s (1997) study on the effect of nature sounds on preoperative anxiety measured anxiety levels with the VAS immediately before and after the intervention; however, it had a small sample size. We found lower anxiety levels in the nature sounds group, similar to Cullum’s findings. Our relaxation and control group patients had similar levels of preoperative anxiety.

The intervention group patients also found the exercises enjoyable. This interactive intervention therefore adds a different dimension to the study. Various studies have found that relaxation exercises reduce anxiety when used during hormonal therapy, ectopic pregnancy, arthroplasty, abdominal surgery, radical mastectomy, pulmonary arterial hypertension, and other procedures (Pan et al., 2012; Zhao et al., 2012; Büyükyılmaz & Aştı, 2013; Rejeh et al., 2013; Li et al., 2015; Zhou et al., 2015). However, we did notfind any previous stud-ies on the use of relaxation exercises to reduce preoperative anxiety. Relaxation exercises in other studies were not used to reduce preoperative anxiety, and the patients did not have

Figure 2. Visual Analog Scale (VAS) scores.

Figure 3. State Anxiety Inventory (SAI) scores.

Table 2. Base anxiety (VAS and SAI) scores in the three groups

Scores Group Xþ¯SD F* P

Baseline VAS Nature sounds 5.75 ± 2.18

Relaxation exercises 5.61 ± 2.18 0.822 0.441

Control 5.20 ± 2.51

Baseline SAI Nature sounds 65.09 ± 12.45

Relaxation exercises 61.43 ± 12.73 2.813 0.063

Control 59.79 ± 9.95

similar characteristics. We are therefore unable to determine any similarity between our results and those of other studies; thus, further research on the effects of relaxation exercises for reducing preoperative anxiety is needed.

Limitations and suggestions for future studies

This study has some limitations. First, blinding of the investiga-tors or patients was not possible because of the nature of the study. Second, the study was conducted on the day of the operation, and the intervention lasted for only one session. Although we showed that the interventions reduce preopera-tive anxiety in the short term, future studies using multiple sessions over a longer period should be conducted. Third, the VAS and SAI scores were correlated in every comparison, but they rely on patient self-report measures and are, thus, subjective. Therefore, objective measurements could be used in future studies. Thefinal limitation was that the patients spent 30 min with their relatives between the second and third measurements, which may have played a role in decreasing or increasing their anxiety. We were unable to evaluate these fac-tors, which should be considered when planning future studies.

CONCLUSION

Nature sounds and relaxation exercises were found to effectively reduce preoperative anxiety in the intervention groups compared with the control in this randomized con-trolled study. Both the nature sounds and relaxation exercise groups had similar VAS and SAI scores, and both experienced a similar level of reduced preoperative anxiety. These interven-tions can therefore be considered non-pharmacological methods to reduce anxiety levels. They are easy to use, inexpensive, and do not cause harm to patients. In conclusion, we believe that nature sounds and relaxation exercises can be used to reduce preoperative anxiety in surgical clinics.

CONTRIBUTIONS

Study design: NE

Data collection and Analysis: NE, ÖU, AB, HÖ Manuscript Writing: NE, ÖU, AB, HÖ

REFERENCES

Aghaie B, Rejeh N, Heravi-Karimooi M et al. Effect of nature-based sound therapy on agitation and anxiety in coronary artery bypass graft patients during the weaning of mechanical ventilation: A randomised clinical trial. Int. J. Nurs. Stud. 2014; 51: 526–538. Ali A, Altun D, Oğuz BH, İlhan M, Demircan F, Koltka K. The effect

of preoperative anxiety on postoperative analgesia and anesthesia recovery in patients undergoing laparascopic cholecystectomy. J. Anesth. 2014; 28: 222–227.

Alvarsson JJ, Wiens S, Nilsson ME. Stress recovery during exposure to nature sound and environmental noise. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2010; 7: 1036–1046.

Annerstedt M, Jönsson P, Wallergård M et al. Inducing physiological stress recovery with sounds of nature in a virtual reality forest -Results from a pilot study. Physiol. Behav. 2013; 118: 240–250. Arai YCP, Sakakibara S, Ito A et al. Intra-operative natural sound

decreases salivary amylase activity of patients undergoing inguinal

hernia repair under epidural anesthesia. Acta Anaesthesiol. Scand. 2008; 52: 987–990.

Bagés Fortacín C, MdM LF, Español-Puig C, Imbernón Casas G, Munté Prunera N, Vázquez Morillo D. Effectiveness of preoperative visit on anxiety, pain and wellbeing. Enferm. Glob 2015; 14: 41–51. Bourne EJ. The Anxiety and Phobia Workbook (5th edn). Oakland,

CA: Raincoast Books, 2010.

Brand LR, Munroe DJ, Gavin J. The effect of hand massage on preoperative anxiety in ambulatory surgery patients. AORN J. 2013; 97: 708–717.

Burckhardt CS, Jones KD, Adult measures of pain. The McGill Pain Questionnaire (MPQ), Rheumatoid Arthritis Pain Scale (RAPS),

Short-form McGill Pain Questionnaire (SF-MPQ), Verbal

Descriptive Scale (VDS), Visual Analog Scale (VAS), and West Haven-Yale Multidisciplinary Pain Inventory (WHYMPI). Arthritis Rheum 2003; 49(Suppl 5): S96–S104.

Büyükyılmaz F, Aştı T. The effect of relaxation techniques and back massage on pain and anxiety in Turkish total hip or knee arthroplasty patients. Pain Manag. Nurs. 2013; 14: 143–154.

Cullum AL. Effects of nature-based sounds on patient anxiety during the preoperative period. (Dissertation)Florida: Florida Atlantic University 1997: 57.

Davis C, Nussbaum GF. Ambient Nature Sounds in Health Care. Perioper. Nurs. Clin. 2008; 3: 91–94.

Demiralp M, Oflaz F. Cognitive behavioral therapy techniques and psychiatric nursing practice. Anatolian Journal of Psychiatry 2007; 8: 132–139.

Feeney SL. The relationship between pain and negative affect in older adults: Anxiety as a predictor of pain. J. Anxiety Disord 2004; 18: 733–744.

Granot M, Ferber SG. The roles of pain catastrophizing and anxiety in the prediction of postoperative pain intensity: A prospective study. Clin. J. Pain 2005; 21: 439–445.

Indratula R, Sukonthasarn A, Chanprasit C, Wangsrikhun S. Experiences of Thai individuals awaiting coronary artery bypass grafting: A qualitative study. Nurs. Health Sci. 2013; 15: 474–479. Jamison RN, Taft K, OHara JP, Ferrante FM. Psychosocial and

pharmacologic predictors of satisfaction with intravenous patient-controlled analgesia. Anesth. Analg. 1993; 77: 121–125.

Kain ZN, Sevarino F, Alexander GM, Pincus S, Mayes LC. Preoperative anxiety and postoperative pain in women undergoing hysterectomy. A repeated measures-design. J. Psychosom. Res. 2000a; 49: 417–422.

Kain ZN, Sevarino F, Pincus S et al. Attenuation of the preoperative stress response with midazolam: Effects on postoperative outcomes. Anesthesiology 2000b; 93: 141–147.

Largo-Wight E, O’Hara BK, Chen WW. The efficacy of a brief nature sound intervention on muscle tension, pulse rate, and self-reported stress: Nature contact micro-break in an office or waiting room. HERD 2016; 10: 45–51.

Lembo T, Fitzgerald L, Matin K, Woo K, Mayer EA, Naliboff BD. Audio and visual stimulation reduces patient discomfort during screening flexible sigmoidoscopy. Am. J. Gastroenterol. 1998; 93: 1113–1116.

Li Y, Wang R, Tang J et al. Progressive muscle relaxation improves anxiety and depression of pulmonary arterial hypertension patients. Evid. Based Complement. Alternat. Med. 2015; 2015: 792895. McArthur-Rouse FJ, Collins T. Psychosocial Aspects of Surgery. In:

McArthur-Rouse FJ, Prosser S (eds). Assessing and Managing the Acutely Ill Adult Surgical Patient. Oxford: Blackwell Publishing, 2007; 77–88.

Munafò MR, Stevenson J. Anxiety and surgical recovery:

Reinterpreting the literature. J. Psychosom. Res. 2001; 51: 589–596. Öner N. LeCompte A. Durumluk/Kaygı Envanteri El Kitabı. İstanbul:

Özalp G, Sarıoğlu R, Tuncel G, Aslan K, Kadıoğulları N. Preoperative emotional states in patients with breast cancer and postoperative pain. Acta Anaesthesiol. Scand. 2003; 47: 26–29.

Pan PH, Coghill R, Houle TT et al. Multifactorial preoperative predic-tors for postcesarean section pain and analgesic requirement. Anesthesiology 2006; 104: 417–425.

Pan L, Zhang J, Li L. Effects of progressive muscle relaxation training on anxiety and quality of life of inpatients with ectopic pregnancy re-ceiving methotrexate treatment. Res. Nurs. Health 2012; 35: 376–382. Pelka M, Kölling S, Ferrauti A, Meyer T, Pfeiffer M, Kellmann M. Acute effects of psychological relaxation techniques between two physical tasks. J. Sports Sci. 2017; 35: 216–223.

Pritchard M. Measuring anxiety in surgical patients using a visual analogue scale. Nurs. Stand. 2010; 25: 40–44.

Rasouli MR, Menendez ME, Sayadipour A, Purtill JJ, Parvizi J. Direct cost and complications associated with total joint arthroplasty in patients with preoperative anxiety and depression. J. Arthroplasty 2016; 31: 533–536.

Rejeh N, Heravi-Karimooi M, Vaismoradi M, Jasper M. Effect of sys-tematic relaxation techniques on anxiety and pain in older patients undergoing abdominal surgery. Int. J. Nurs. Pract. 2013; 19: 462–470. Roh YH, Gong HS, Kim JH, Nam KP, Lee YH, Baek GH. Factors associated with postoperative nausea and vomiting in patients undergoing an ambulatory hand surgery. Clin. Orthop. Surg. 2014; 6: 273–278.

Roykulcharoen V, Good M. Systematic relaxation to relieve postoperative pain. J. Adv. Nurs. 2004; 48: 140–148.

Saadatmand V, Rejeh N, Heravi-Karimooi M et al. Effect of nature-based sounds’ intervention on agitation, anxiety, and stress in patients under mechanical ventilator support: A randomised controlled trial. Int. J. Nurs. Stud. 2013; 50: 895–904.

Thompson M, Moe K, Lewis CP. The effects of music on diminishing anxiety among preoperative patients. J. Radiol. Nurs. 2014; 33: 199–202.

Tsuchiya M, Asada A, Ryo K et al. Relaxing intraoperative natural sound blunts haemodynamic change at the emergence from propofol general anaesthesia and increases the acceptability of anaesthesia to the patient. Acta Anaesthesiol. Scand. 2003; 47: 939–943.

Valiee S, Bassampour SS, Nasrabadi AN, Pouresmaeil Z, Mehran A. Effect of acupressure on preoperative anxiety: A clinical trial. J. Perianesth. Nurs. 2012; 27: 259–266.

Van den Bosch JE, Moons KG, Bonsel GJ, Kalkman CJ. Does measurement of preoperative anxiety have added value for predicting postoperative nausea and vomiting? Anesth. Analg. 2005; 100: 1525–1532.

Zhao L, Wu H, Zhou X, Wang Q, Zhu W, Chen J. Effects of progressive muscular relaxation training on anxiety, depression and quality of life of endometriosis patients under gonadotrophin-releasing hormone agonist therapy. Eur. J. Obstet. Gynecol. Reprod. Biol. 2012; 162: 211–215.

Zhou K, Li X, Li J et al. A clinical randomized controlled trial of music therapy and progressive muscle relaxation training in female breast cancer patients after radical mastectomy: Results on depression, anx-iety and length of hospital stay. Eur. J. Oncol. Nurs. 2015; 19: 54–59.