REPRESENTATIONS OF SYRIAN REFUGEES IN TURKISH NEWS MEDIA: CONTENT ANALYSIS OF OPPOSITIONAL NEWSPAPERS

A Master’s Thesis

by

UFUK GÜRBÜZDAL

Department of Communication and Design İhsan Doğramacı Bilkent University

Ankara June 2021

i

REPRESENTATIONS OF SYRIAN REFUGEES IN TURKISH NEWS MEDIA: CONTENT ANALYSIS OF OPPOSITIONAL NEWSPAPERS

The Graduate School of Economics and Social Sciences of

İhsan Doğramacı Bilkent University

by

UFUK GÜRBÜZDAL

In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of MASTER OF ARTS IN MEDIA AND VISUAL STUDIES

THE DEPARTMENT OF COMMUNICATION AND DESIGN İHSAN DOĞRAMACI BİLKENT UNIVERSITY

ANKARA June 2021

I

I certify that I have read this thesis and have found that it is fully

adequate, in scope and in quality, as a thesis for the degree of Master of

Art

��

cJllP

Visual Studies.

--·

-.--

-

-

. .Prof. Dr. Bülent Çaplı

Supervisor

I certify that I have read this thesis and have found that it is fully

adequate, in scope and in quality, as a thesis for the degree of Master of

Arts i11:

_

Medi

_

a and Visual Stqdi.es.

-- - -:'W'.

---Prof.Dr. Mutlu Binark

Examining Committee Member

I certify that I have read this thesis and have found that it is fully

adequate, in scope and in quality, as a thesis for the degree of Master of

Arts in Media and Visual Studies.

A\s

b

ist. Prof. Dr. Emel Özdora Akşak

Examining Committee Member

Approval of the Graduate School ofEconomics and Social Sciences

---�---

-

�

---Prof. Dr. Refet S. Gürkaynak

Director

iii

ABSTRACT

REPRESENTATIONS OF SYRIAN REFUGEES IN TURKISH NEWS

MEDIA: CONTENT ANALYSIS OF OPPOSITIONAL

NEWSPAPERS

Gürbüzdal, Ufuk

M.A., in Media and Visual Studies Supervisor: Prof. Dr. Bülent Çaplı

June 2021

This thesis examines the representations of Syrian refugees in online news articles broadcasted by Turkish oppositional newspapers from different ideological and political orientations. The three oppositional media outlets, Evrensel, Milli Gazete and Sözcü, each with different politico-ideological standpoints, are examined for their news content. In the study, as a reference newspaper for pro-government news media, Sabah’s news content is also scrutinized. The news content of Sabah is analyzed to politically contextualize, first and foremost, the Turkish government’s refugee policy and, then, the examined newspapers’ opposition to this policy. The time scale of content analysis is divided into two central periods. To identify the most prominent representation differences in the news articles disseminated before and after the mass settlement of Syrian refugees in Turkish cities, the reports

broadcasted solely in 2011-2013 and 2016-2018 are included in the content analysis scope. For newspapers where a sufficient number of online news is publicly available and accessible, 30 news articles per newspaper per year are analyzed. In cases where it is not possible to reach 30 reports, only the accessible amount of news is analyzed. Keywords: Framing, Syrian, Refugee, Media, Representation

iv

ÖZET

SURİYELİ SIĞINMACILARIN TÜRKİYE HABER MEDYASINDA

TEMSİLLERİ: MUHALİF GAZETELERİN İÇERİK ANALİZİ

Ufuk Gürbüzdal

Yüksek Lisans, Medya ve Görsel Çalışmalar Tez Danışmanı: Prof. Dr. Bülent Çaplı

Haziran 2021

Bu tez, Suriyeli sığınmacıların farklı ideolojik ve siyasi yönelimlere sahip Türkiye muhalif gazeteleri tarafından yayımlanan çevrim içi haber metinlerindeki temsillerini incelemektedir. Her biri farklı siyasi ve ideolojik bakış açısına sahip üç muhalif medya kuruluşu olan Evrensel, Milli Gazete ve Sözcü’nün haber içerikleri

incelemeye tabi tutulmaktadır. Çalışmada, hükümet yanlısı haber medyası için bir referans gazete olarak Sabah’ın haber içeriği de ele alınmaktadır. Sabah'ın haber içeriği, öncelikle Türkiye hükümetinin sığınmacı politikasını ve ardından incelenen gazetelerin bu politikaya muhalefetini siyasi açıdan bağlamsallaştırmak için analiz edilmektedir. İçerik analizinin zaman ölçeği iki merkezi dilime bölünmüştür. Suriyeli sığınmacıların kitlesel olarak Türkiye şehirlerine yerleşmelerinden önce ve sonra dolaşıma sokulan haber metinlerindeki en belirgin temsil farklılıklarını tespit etmek amacıyla, içerik analizi kapsamına yalnızca 2011-2013 ve 2016-2018 yılları arasında yayımlanan haberler dahil edilmiştir. Yeterli sayıda çevrim içi haberin kamuya açık ve erişilebilir olduğu gazetelerde, gazete başına her yıl için 30 haber incelenmektedir. 30 habere ulaşmanın mümkün olmadığı durumlarda, yalnızca erişilebilen miktarda haber incelenmiştir.

v

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

It is with genuine pleasure that I express my deepest sentiments of gratitude to Prof. Dr. Bülent Çaplı, under whose supervision this thesis came to matter. Without his timely advice and scholarly scrutiny, this thesis would have lacked the systematic structure that it bears now. During times where this study hit a deadlock, his encouraging and inspiring attitude to help me allowed me to overcome many methodological difficulties that would have otherwise prevented me from

accomplishing this task. I thank him profusely for his irreplaceable mentorship and guidance, from which I benefited immensely throughout all the stages of creating this thesis.

It is also my privilege to thank Gökçen Düzkaya, who with her boundless emotional support always lent me the helping hand that I needed during a painful time of my life. Without her presence in my life, it would have been impossible to set the right trajectory for this research when it was still in its core phase.

My dear comrade Ozan Siso unreservedly stood in solidarity with me throughout the making of this thesis. As always, he mobilized his intellectual riches to criticize me and critically review my work. It is most opportune to have his friendship in an era when human relations are captive to selfish personal interests.

My dear colleague Res. Ass. C. Gökçe Elkovan provided the physical conditions that rendered this study possible. When I was most unbearable, she was there to tirelessly

vi

listen to my whining and comfort me about writing up this thesis. I am indebted to her for her kindness and dedicated efforts.

My dear colleague Res. Ass. Emirhan Alan took on some of my workload in the faculty so that I could devote the necessary time to conduct my research. It was always a joy to have him as a colleague and by my side.

Two of my dearest family members, Yasin Aktaş and Onur Çakmak, furnished confidence and trust by their presence back home after I left Ankara. It is fortunate that they exist.

vii

TABLE OF CONTENTS

ABSTRACT ... iii

ÖZET... iv

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS ... v

TABLE OF CONTENTS ... vii

LIST OF TABLES ... ix

LIST OF FIGURES ... xi

CHAPTER I: INTRODUCTION ... 1

CHAPTER II: LITERATURE REVIEW ... 11

2.1. Milestones of Turkey’s Refugee Policy ... 11

2.1.1. Political Position of the Turkish Government towards the Syrian Refugees Until 2013... 11

2.1.2. A Qualitative Change in the Turkish Government's Political Discourse on Syrian Refugees in the Post-2013 Period ... 17

2.2. Construction of Immigrant and Refugee Identity in the News Media ... 20

2.2.1. Politics of Representation ... 20

2.3. Dominant Representations of Syrian Refugees in the Turkish News Media ... 24

2.4. Dominant Representations of Immigrants and Refugees in Western Media ... 27

2.5. Media Framing Theory and Representations of Immigrants and Refugees ... 31

CHAPTER III: METHODOLOGY ... 34

CHAPTER IV: CONTENT ANALYSIS OF SABAH ... 48

4.1. Quantitative Analysis of the News Content in Sabah: 2011-2013 ... 49

viii

4.2. Interpretation of the Quantitative Findings in Sabah:

2011-2013 ... 54

4.3. Quantitative Analysis of the News Content in Sabah: 2016-2018 ... 61

4.4. Interpretation of the Quantitative Findings in Sabah: 2016-2018 ... 67

CHAPTER V: CONTENT ANALYSIS OF OPPOSITIONAL NEWSPAPERS ... 73

5.1. Quantitative Analysis of the News Content in Evrensel: 2011-2013 and 2016-2018 ... 73

5.2. Interpretation of the Quantitative Findings in Evrensel ... 79

5.2.1. 2011-2013 ... 79

5.2.2. 2016-2018 ... 83

5.3. Quantitative Analysis of the News Content in Milli Gazete: 2011-2013 and 2016-2018 ... 87

5.4. Interpretation of the Quantitative Findings in Milli Gazete ... 93

5.4.1. 2011-2013 ... 93

5.4.2. 2016-2018 ... 97

5.5. Quantitative Analysis of the News Content in Sözcü: 2011-2013 and 2016-2018... 100

5.6. Interpretation of the Quantitative Findings in Sözcü ... 107

5.6.1. 2011-2013 ... 107

5.6.2. 2016-2018 ... 110

CHAPTER VI: CONCLUSION AND DISCUSSION ... 116

6.1. Limitations of the Study and Suggestions for Future Research ... 131

REFERENCES ... 132

APPENDICES ... 153

ix

LIST OF TABLES

Table 1. Number of Analyzed News and Total Word Count ... 34

Table 2. (Coding Sheet 1) Frame Categories and Operational Definitions ... 39

Table 3. (Coding Sheet 2) Categories of Socio-Political Context and Operational Definitions ... 40

Table 4. Findings of Sabah, (Frame Categories and Categories of Socio-Political Context) ... 48

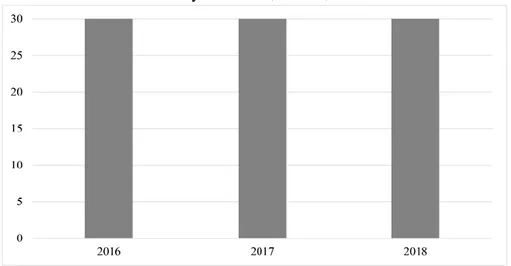

Table 5. Number of Analyzed News, Sabah, 2011-2013 ... 49

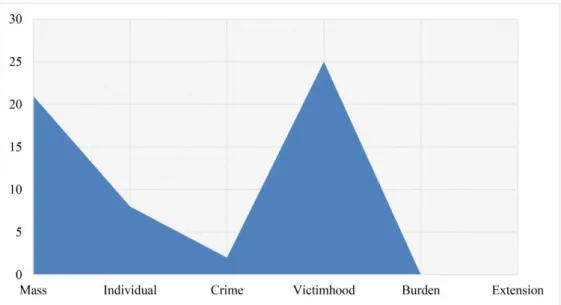

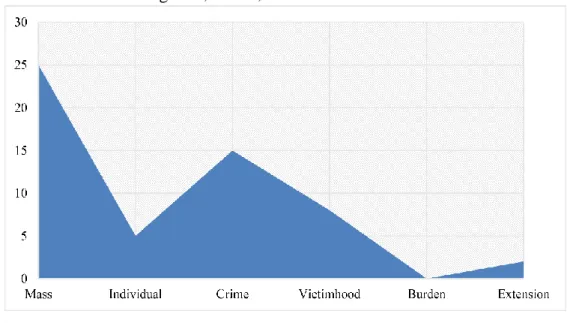

Table 6. Frame Categories, Sabah, 2011 ... 50

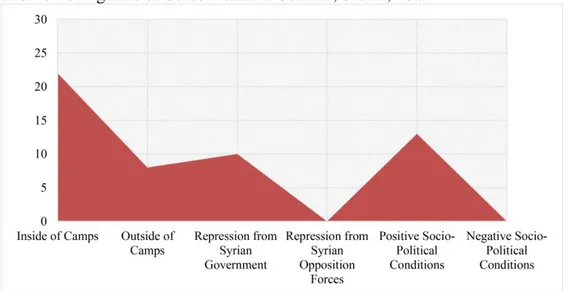

Table 7. Categories of Socio-Political Context, Sabah, 2011 ... 50

Table 8. Frame Categories, Sabah, 2012 ... 51

Table 9. Categories of Socio-Political Context, Sabah, 2012 ... 52

Table 10. Frame Categories, Sabah, 2013 ... 52

Table 11. Categories of Socio-Political Context, Sabah, 2013 ... 53

Table 12. Number of Analyzed News, Sabah, 2016-2018 ... 62

Table 13. Frame Categories, Sabah, 2016 ... 62

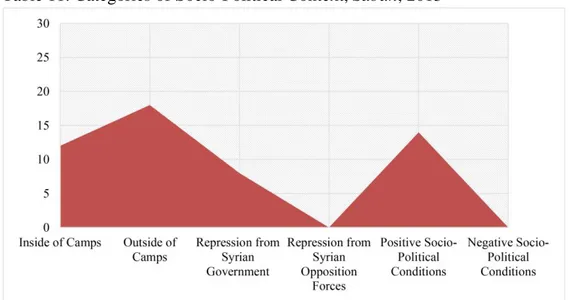

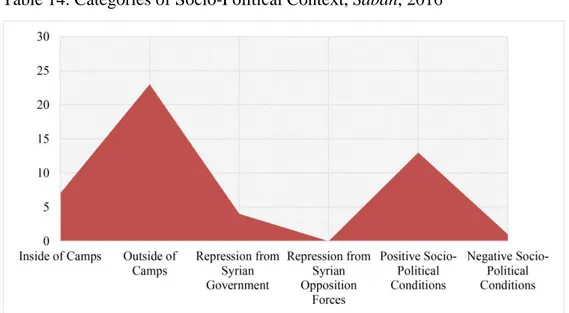

Table 14. Categories of Socio-Political Context, Sabah, 2016 ... 63

Table 15. Frame Categories, Sabah, 2017 ... 64

Table 16. Categories of Socio-Political Context, Sabah, 2017 ... 64

Table 17. Frame Categories, Sabah, 2018 ... 65

x

Table 19. Findings of Evrensel, (Frame Categories and Categories of Socio-Political

Context) ... 73

Table 20. Number of Analyzed News, Evrensel, 2011-2013 / 2016-2018 ... 74

Table 21. Frame Categories, Evrensel, 2011-2013 ... 75

Table 22. Categories of Socio-Political Context, Evrensel, 2011-2013 ... 76

Table 23. Frame Categories, Evrensel, 2016-2018 ... 77

Table 24. Categories of Socio-Political Context, Evrensel, 2016-2018 ... 78

Table 25. Findings of Milli Gazete, (Frame Categories and Categories of Socio-Political Context) ... 87

Table 26. Number of Analyzed News, Milli Gazete, 2011-2013 / 2016-2018 ... 88

Table 27. Frame Categories, Milli Gazete, 2011-2013 ... 88

Table 28. Categories of Socio-Political Context, Milli Gazete, 2011-2013... 89

Table 29. Frame Categories, Milli Gazete, 2016-2018 ... 91

Table 30. Categories of Socio-Political Context, Milli Gazete, 2016-2018... 92

Table 31. Findings of Sözcü, (Frame Categories and Categories of Socio-Political Context) ... 100

Table 32. Number of Analyzed News, Sözcü, 2011-2013 / 2016-2018 ... 101

Table 33. Frame Categories, Sözcü, 2011-2013 ... 102

Table 34. Categories of Socio-Political Context, Sözcü, 2011-2013 ... 102

Table 35. Frame Categories, Sözcü, 2016-2018 ………. 104

xi

LIST OF FIGURES

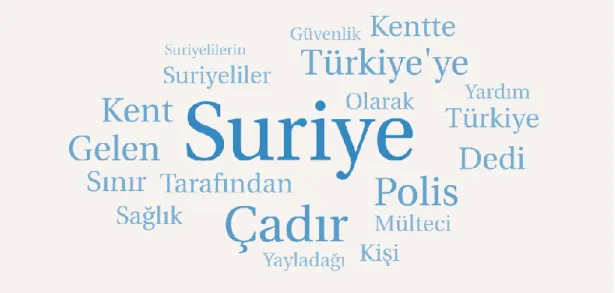

Figure 1. Word Cloud of Sabah (2011-2013) ... 54

Figure 2. Word Cloud of Sabah (2016-2018) ... 67

Figure 3. Word Cloud of Evrensel (2011-2013) ... 77

Figure 4. Word Cloud of Evrensel (2016-2018) ... 79

Figure 5. Word Cloud of Milli Gazete (2011-2013) ... 90

Figure 6. Word Cloud of Milli Gazete (2016-2018) ... 93

Figure 7. Word Cloud of Sözcü (2011-2013) ... 104

1

CHAPTER I

INTRODUCTION

“When I leave, be sure to know that I did everything I could to stay”1 (NaTakallam, 2015).

During the recent turbulent historical period in the Middle East, which is now recognized by many as the Arab Spring, thousands of Middle Eastern people left their countries because of the violent socio-economic conditions that primarily threatened their most basic human right, that is, the right to life. The urgent need for establishing new residences and means of livelihood for these people is still a problem that is yet to be resolved. Turkey is among the leading refugee-hosting countries, where the phenomenon of immigration stirs the political and socio-economic conjuncture by a broad set of impacts. In Turkey, the number of refugees2

1 Graffiti on a wall in Syria.

2 From a conceptual point of view, it is necessary to distinguish the word immigrant from others, such

as asylum-seeker and refugee. While the word immigrant defines a person who voluntarily leaves her country to reach better living conditions, the words asylum-seeker and refugee define an individual who has to leave her country due to adverse conditions (Ünal, 2014, p. 71). In this context, as will be discussed more in detail as this project unfolds, the word refugee is the proper definition that

illustrates the socio-political condition of Syrian citizens in Turkey. While the term immigrant is used more often in scientific studies conducted in the United States of America (USA), asylum-seeker is a word employed more frequently in European-based research (Hickerson & Dunsmore, 2016, p. 2). While all three of these words are commonly used adjectives to denominate Syrian refugees in the Turkish press, asylum-seeker is the most preferred word of all to describe them (Paksoy & Şentöregil, 2018, p. 247). To overcome certain methodological issues that may arise, this study utilizes the words immigrant, asylum-seeker, and refugee synonymously.

2

who are considered as “persons of concern” is approximately 3.6 million people by the year 2020 (Refugee Population Statistics Database, 2020).

Since 2011, because of the unexpected rise in the number of refugees living in Turkey, Turkish news media has been confronted with the unforeseen task of generating news content representing refugees. By concentrating on the case of Syrian refugees who have been placed in Turkey since 2011, this study analyzes how and in which socio-economic context Syrian refugees are represented in Turkish oppositional news media.

Through a detailed content analysis, the study examines online news published by the Turkish newspapers named Evrensel, Milli Gazete, Sözcü and Sabah in the time periods of 2011-2013 and 2016-2018. The content published by Evrensel, Milli Gazete and Sözcü are analyzed as oppositional newspapers known for their political opposition to the Justice and Development Party (AKP) government. Despite their political opposition to the AKP government, these three newspapers differ from one another in terms of their political and ideological orientations.

Evrensel has socialist political leanings nuanced by an internationalist approach. Evrensel follows a journalism practice that coincides with the socialist ideology in the agenda of Turkish political life and builds its editorial policy upon labor politics (Yaylagül & Çiçek, 2011, pp. 96-106). Milli Gazete has an explicitly conservative political attitude. Milli Gazete is a newspaper that was established in advocacy for the National Vision Movement (“Milli Görüş Hareketi” in Turkish) and adopts a

3

conservative Islamist editorial approach (Kaban Kadıoğlu, 2018, p. 104; Kuruluş Hakkında, n.d.). Although Milli Gazete has a conservative ideology similar to that of the AKP government, it stands in opposition to the AKP government within the Turkish political landscape. Milli Gazete is known for its affinity to the Felicity Party (SP). SP is a political party that operates in opposition to the AKP government. Lastly, Sözcü is recognized for its nationalist political orientation with secular nuances. Although Sözcü supports the Republican People’s Party (CHP) in certain political moments (Yaylagül, 2019, p. 332), the newspaper is not directly related to any political party in the Turkish parliament.

The fact that these newspapers have different political and ideological standpoints allows this study to conduct a politico-ideologically comparative research. By

employing an explicitly comparative approach, the research aims to unearth the most evident differences in representations of Syrian refugees by oppositional news media outlets in Turkey, whether be they socialist, conservative or secular nationalist.

From 2011 to 2015, Turkey has implemented an "open-door" policy towards Syrian refugees (İçduygu & Şimşek, 2016, p. 60). Before the enforcement of the 1951 Convention of Refugees, there was no official law about asylum issues of foreigners in Turkey (Kirisci, 2000, p. 10). On the other hand, although Turkey is a signatory of the 1951 Convention, the legislation of the convention has a geographical limitation annotating that Turkey does not provide individuals who settle to Turkey from outside of Europe with official immigrant status (UNHCR, 2007).

4

United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR) achieves a lasting resolution in another territory for the settlement problem of the refugees (UNHCR, 2007). In this context, a legal gap has appeared on the official status of the first wave of Syrian refugees who have settled in Turkey from Syria in 2011-2013. Until 2015, the adjective “guest” was used as an unofficial status to describe the ambiguous political status of Syrian refugees in Turkey (İçduygu & Şimşek, 2016, p. 60). In a sense, the title of guest was echoing the expectation of the Turkish society that the existence of Syrian refugees in Turkey will be a temporary phenomenon. As Boztepe (2017) and Gölcü and Dağlı (2017) state, the initial high acceptance rate of Syrian refugees by Turkish society has been primarily motivated by the common belief in the impermanence of the presence of refugees in Turkish territory. Although the level of acceptance of Syrian refugees by Turkish society was high, in 2014, a significant portion of Turkish citizens were noted to suppose that Syrian refugees would return to their homeland upon the end of the war in Syria (Center, 2014, p. 75).

In the summer of 2015, Turkey was hosting approximately 2 million Syrian refugees, and Turkey and the United Nations (UN) had activated the "Joint Action Plan" aiming to control and reduce the flow of Syrian refugees to Turkey (İçduygu & Şimşek, 2016, p. 61). In the context of Turkish politics, the year 2016 witnessed the implementation of official policies that implied the long-term permanence of Syrian refugees in Turkey, such as conferring citizenship to the refugees and granting them a work permit (İçduygu & Şimşek, 2016, pp. 61-62). In the first week of July 2016, Turkish President Recep Tayyip Erdoğan issued a statement to the press declaring that some Syrian refugees, especially those with qualified working skills, could be granted Turkish nationality (Erdoğan'dan Vatandaşlık Açıklaması, 2016). According

5

to İçduygu (2017), following President Erdoğan’s proclamation, the existence of Syrian refugees in Turkey became a relatively more politicized subject within the Turkish political field.

Immediately after the Joint Action Plan, the radical increase in the number of irregular asylum-seekers through the Eastern Mediterranean region led the

international arena to seek international, regional and local solutions to the refugee issue (Elitok, 2019, pp. 2-3). This quest for a concrete solution eventuated in the emergence of an agreement between the EU and Turkey in 2016. This EU-Turkey deal laid the legal basis of the securitization of Turkish borders neighboring Europe and aimed at providing safer and improved living conditions for Syrian refugees in various fields of social life, particularly in the market (Heck & Hess, 2017, pp. 44-45). It was originally planned in return to make legal arrangements to exempt Turkish citizens from visas in the Schengen area, provide financial support to Turkey, and take new steps to facilitate Turkey's transition to its prospective membership in the EU (Heck & Hess, 2017, pp. 44-45).

With this deal, it was intended to repatriate irregular migrants crossing Europe back in Turkey and so would Turkey send Syrian refugees to European states for

settlement (Rygiel & Baban & Ilcan, 2016, p. 316). In this way, the irregular passage to Europe would be brought under control and the entire process would be rearranged under rather legal terms (Rygiel et al., 2016, p. 315). However, the deal has also received various criticisms on the grounds that it meant European states, which are signatories to the 1951 Geneva Convention Relating to the Status of Refugees,

6

breaking their obligations of sheltering asylum-seekers (Rygiel et al., 2016, pp. 315-316). Along with the strict government practices implemented under the state of emergency that emerged following the July 15 military coup attempt in Turkey, the European Parliament (EP) temporarily suspended Turkey's accession negotiations and, thereby, disrupted the aforesaid process (Çetin & Turan & Çetin & Hamşioğlu, 2017, p. 14). It was around this time that Turkish President Erdoğan announced Turkey would open its borders for asylum-seekers to re-enter Europe in case the EU suspended the membership negotiations (Çetin et al., 2017, p. 14).

When political reactions of leading oppositional parties in the Turkish Parliament towards President Erdoğan’s statement are considered, it is possible to find vital evidence in support of İçduygu’s (2017) argument mentioned above. For example, representatives of Republican People’s Party (CHP) and Peoples’ Democratic Party (HDP) considered Erdoğan’s declaration to be a strategic political move to win new votes for the ruling party before the next elections (Hacaloğlu, 2016; Köylü, 2016). A deputy from HDP remarked that Erdoğan identifies Syrian refugees with the cheap workforce (Hacaloğlu, 2016; Köylü, 2016). Nationalist Movement Party (MHP) leader, Devlet Bahçeli, stated that granting Syrian refugees with Turkish citizenship could lead to ethnic tensions in Turkey (Girit, 2016). Furthermore, as a reaction of Turkish social media users towards the declaration, a Twitter hashtag #Ülkemde Suriyeli İstemiyorum (#I Don't Want Syrians in My Country) entered into the worldwide list of trending topics on Twitter. These socio-political indicators show that the asylum debate in Turkey has changed in qualitative aspects due to the implementation of policies implying the permanency of Syrian refugees in Turkey.

7

The Syrian refugee question has also influenced the state of affairs during the June 2015 Turkish general and presidential election. The 2015 election could be

considered a first in Turkey because the influence of the Syrian refugee question on the Turkish public opinion was measured (Ceylan & Uslu, 2019, p. 98). Before the elections, Turkish political parties had made statements on their political positioning about the Syrian refugees through pamphlets and leaflets (Ceylan & Uslu, 2019, p. 98). As an oppositional political party, CHP had drawn attention to the use of refugees as cheap labor and how the refugees’ existence in Turkey could possibly impact the election results, whereas HDP pointed out the importance of granting the refugees an unconditional right to self-determination (Ceylan & Uslu, 2019, pp. 108-110).

Moreover, during the 2018 elections in Turkey, the Turkish public sought a more precise and detailed answer from the political parties about the future of Syrian refugees, and this public curiosity had marked the course of affairs with the elections (Çiçek & Arslan & Baykan, 2018, p. 150). In this context, the political parties

participating in the elections presented their tentative trajectories regarding the refugee question (Çiçek & Arslan & Baykan, 2018, p. 150). AKP, as the party in government, called attention to the aid provided to refugees by their government and called on Turkish citizens to tolerate asylum-seekers (Çiçek & Arslan & Baykan, 2018, pp. 151-153). The ultranationalist MHP, which was in the same electoral alliance as AKP, emphasized that asylum-seekers posed an economic burden and precipitated a significant increase in crime rates. As the main opposition party, CHP criticized the government’s expansionist policies by linking the issues relevant to the refugee question with foreign policy. HDP, as another opposition party in the

8

parliament, emphasized the right to equal citizenship (Çiçek & Arslan & Baykan, 2018, pp.151-153).

As Erdoğan M (2019) points out, the sudden increase in the number of Syrian refugees settling into Turkish territory may have caused a “social shock” in Turkish society. In 2011, Turkey was hosting only 58 thousand refugees (p. 15). In 2015, only two years after the participation of Syrian refugees in Turkish economic activity, Turkish Confederation of Employer Associations (TISK) reported that the growing number of informal economic activities in Turkey triggered a fear of job loss among Turkish citizens (Erdoğan & Ünver, 2015, p. 9). Within a similar vein, the statistical data from 2014 demonstrate that 70, 8 % of Turkish citizens considered Syrian refugees as harmful to Turkey's economy, and 62, 3 % of them associated the refugees with societal crime (Center, 2014, pp. 26-29). It is possible to claim that the mass placement of Syrian refugees in Turkish cities might have affected not only Turkish public opinion but also shaped the representation of refugees by Turkish oppositional news media outlets. Therefore, it would be a functional and purposive methodological approach to divide the analysis of the representation of the refugees in Turkish media into two main periods, which follow the timeline before and after the mass settlement of refugees in Turkish cities. Indeed, as Boztepe (2017) asserts, the adjective “guest” may expeditiously be replaced with hate speech and hostile expressions in media representations of refugees. Assigning a well-justified time frame for the research would instrumentalize the detection of such sudden changes in media content.

9

By analyzing the representation of Syrian refugees in Turkish oppositional

newspapers within two main periods, this thesis therefore aims to find explanatory answers to two research questions:

1) What are the most distinguishing differences among diverse representations of Syrian refugees by the news published by Turkish oppositional news media?; and 2) how, and to what extent, do editorial practices of the examined newspapers reflect the dynamics of the social and political climate in Turkey that rapidly changed in response to the mass placement of refugees in Turkish cities?

In order to answer these research questions with a systematic research approach, CHAPTER II analyzes the Turkish government's refugee policy’s milestones between 2011 and 2016 to place the refugee issue in the context of Turkish politics. Examining the political practices between 2011 and 2016 gives the study a socio-political context since the study examines the media representations of asylum-seekers in the news disseminated before and after 2016. After addressing the construction of immigrant and refugee identity in the news media and discussing media framing theory, the chapter provides a concise set of references to the scientific studies analyzing the representations of Syrian refugees in the Turkish news media. The chapter concludes with an analysis of stereotypical refugee representations in Western media.

10

CHAPTER III conducts a detailed discussion of the study’s method and introduces to the reader the categories and operational definitions of content analysis operated in this research.

CHAPTER IV analyzes the Syrian refugees’ representations in the time periods of 2011-2013 and 2016-2018 in the news of Sabah, which is politically and

ideologically close to the AKP government. Sabah is examined as a reference media in terms of being a Turkish pro-government newspaper.

CHAPTER V scrutinizes the Syrian refugee representations in the news content of the examined oppositional newspapers. Each newspaper's news content is compared to the news content of Sabah and other oppositional newspapers when applicable.

CHAPTER VI concludes the study by presenting and comparatively discussing the research findings and includes suggestions for future scientific studies.

11

CHAPTER II

LITERATURE REVIEW

This chapter examines predominant refugee policies of the AKP government from 2011 to 2016, questions stereotypical patterns and cliches of refugee and immigrant representations in the media, highlights the importance of the media framing theory in the process of examining the representation of refugees and immigrants,

epitomizes scientific studies on Syrian refugees' representations in Turkish media, and then encapsulates immigrant and refugee representations performed by Western media.

2.1. Milestones of Turkey’s Refugee Policy

2.1.1. Political Position of the Turkish Government towards the Syrian Refugees Until 2013

Migration movements that took place in the 19th century were generally based on individual political decisions. On the other hand, rigorous social events such as the First World War, revolutions, and the disintegration of empires had introduced the world to the phenomenon of mass migration, and prevailing narratives of refugee protection still have their roots in these incidents (Marrus, 1985, pp. 15-20). Modern states have since faced the problem of accepting refugees en masse.

12

Turkey has always been a path of migration due to its unique geographical location. Located at the crossroads of Europe and Asia, Anatolia has been a road for many that led a way out of famine, war and deprivation (Central Intelligence Agency, 2021). Part of the Fertile Crescent and neighboring Mesopotamia to its south-east, to the south of Turkey also lies the Mediterranean which helped sailing from, and to, the African continent (Collon, 2011). Not surprisingly, present-day Turkey was also home to the world’s oldest permanently settled sites, including Göbeklitepe and Çatalhöyük, former of which also hosts the earliest human-made structure (McMahon & Steadman, 2011 pp. 3-11; Scham, 2008, p. 23). From Hittites to Greeks and Persians, from the cosmopolitan Hellenistic Empire to the

ethno-linguistically diverse Roman Empire, the country hosted countless peoples and their cultures (McMahon & Steadman, 2011 pp. 3-11). Turkey was blessed with its geopolitical importance, owing to which the courses of the Royal Road and the Silk Road ran through it, but also was unblessed with many invasions, including the infamous Mongol Invasions (Lane, 2006, p. 442; Kelly, 2005).

With the waves of Turkic migration, which resulted in, first, the rule of the Seljuks and, then, the reign of the Ottoman royal house, the ethno-linguistic and cultural precursors to present-day Turkey had emerged (Köprülü, 1992, p. 33). It was during the demise of the Ottoman Empire that migration was once again on the agenda with those who emigrated from parts of Turkey and the rest of the empire as well as Turks and Muslims who immigrated back to Anatolia, the Turkish core of the empire (Ferguson, 2006, p. 179-181). After the collapse of the Ottoman Empire, it was agreed in Lausanne in 1923 between the Ankara government and the Kingdom of Greece that a major compulsory population exchange would take place between

13

Greece and Turkey (Clogg, 2002, p. 101). In 1983, the Turgut Özal government would in Van settle thousands of Kyrgyz who were exiled (Devlet Karapınar, 2017, p. 110). In 1989, Turkey would again receive a major immigration wave of Bulgarian Turks who were forced to migrate because of the political conditions in Bulgaria at the time (Laber, 1987, pp. 45-47).

As Kirisci (2000) notes, considering migration as a matter of national security helps states to strictly preserve their authority to decide on who can be recognized as an immigrant (p. 3). For modern states, securitization discourse is a crucial instrument steering the dynamics of migration discussion. As Aras and Mencutek (2015) state, both the arguments for “burden-sharing” and the discourse of “securitization” have together been used to legitimize temporary protection status and return policies since 2000 (p. 193).

The September 11 attacks are a turning point concerning the securitization of immigration. In the American context, the public attitude toward immigration was favorable before the September 11 attacks (Esses et al., 2002, p. 72). Moreover, the public manner toward socio-economic integration of Hispanic immigrants and their media portrayals were more positive before the attacks (Hainmueller & Hopkins, 2014, p. 233). After September 11, the immigration phenomenon was securitized in Europe and North America. Migration policies of nations were thereafter considered as an ordinary extension of domestic security policies, and the immigrants were increasingly portrayed in connection with terrorist activities (Mudde, 2012, p. 11; Mandacı & Özerim, 2013, p. 123). Securitization of migration is also a widespread

14

phenomenon in the European media. On the other hand, this does not mean that negative economic narratives on immigration are decreasing in the European media. What is observed is that different narratives co-exist; there is a multi-narrative in implementation (Caviedes, 2015, p. 912).

As a political strategy, radical right-wing parties frequently identify refugees as the culprits behind economic problems and describe them as an invasive subject against the national culture of the receiving country and European culture; immigrants, as depicted by far-right, are a threat to the domestic security of the receiving country (Mandacı & Özerim, 2013, pp. 115-120). This political strategy provides political support to nationalist and conservative parties through explicit populist rhetoric. Moreover, in the time spectrum from the 1980s to the 2000s, the anti-immigrant discourse of the far-right political movements spread to almost all of the mainstream political organizations (Ünal, 2014, p. 67; Caviedes, 2015, p. 899). Scapegoating of immigrants has become a typical phenomenon (Ünal, 2014, p. 67). Conservative AKP, as a right-wing ruling party of Turkey, implemented policies on Syrian refugees that constitute an anomaly within this regard.

In the early phase of the Syrian people’s migration to Turkey, Syrian refugees were not defined by the AKP government as a security flaw or as an economic burden. In contrast, when the influx of Syrian refugees to Turkey began, Turkey avoided using the rhetoric of securitization. Instead, the Turkish government implemented an unconditional open door policy for all Syrian refugees by identifying them as guests

15

(Aras & Mencutek, 2015, pp. 194-201). Initially, the government repudiated

international supports on the refugee issue to prove that Turkey was a strong model country in the Middle East to arbitration (Aras & Mencutek, 2015, p. 202). To better grasp the dynamics of the AKP government's refugee policy in Turkey, it is

necessary to have an insight into AKP’s hopes and expectations in the Middle East region.

As a general trend, Syrian refugees are defined by the prevailing political discourse of the AKP government as oppressed people in need of help. Within this specific discourse, the Turkish state is mainly defined as a political unit that embraces needy refugees. Seemingly, the government statements, which frequently refer to the government’s economic, social, and political assistance to the Syrian refugees, are the fundamental constituents of this discourse. In the AKP rally held in Hatay on May 28, 2011, Recep Tayyip Erdoğan, then-Prime Minister of Turkey, identified Syrian refugees as "brothers." In the same rally, Erdoğan emphasized that the Turkish state had "embraced" Syrian refugees and "lent a helping hand" to them. To him, the Turkish state had a sincere effort for the comprehensive delivery of rights and freedoms in Syria (Erdoğan, 2019, p. 150).

From this point of view, the political discourse of the AKP government defines the Syrian government as an anti-democratic political unit that violates the fundamental rights and freedoms of the Syrian people. In April 2012, Ahmet Davutoğlu, then-Foreign Minister of Turkey, recognized political developments in Syria as part of the Middle Eastern region's political change and revival process. In his speech, he stated

16

that “the walls of the status-quo are being destroyed” (Dışişleri Bakanı Sayın Ahmet Davutoğlu’nun TBMM Genel Kurulu’nda, n.d., 2012). Subsequently, on December 30, 2012, Erdoğan, in another speech he gave in Şanlıurfa, defined the Syrian government as "sanguinary" and "illegitimate” while he also stressed the

"hospitable" and "brotherly" approach of the people of Şanlıurfa to Syrian refugees (Erdoğan, 2019, p. 266). In the broadest sense, the AKP government explicitly questioned the legitimacy of the Syrian government, and the existence of Syrian refugees accommodated in Turkey is grasped within this political context.

In the AKP government's political discourse, defining the Syrian government as an oppressive political subject, seems to be a precondition for describing Syrian

refugees' situation as a matter of humanity. In 2011, Erdoğan defined Syrian refugees as “victimized,” “oppressed” and “vulnerable” people; in the same speech, he

identified the Turkish state’s responsibility on Syrian refugees as a humanitarian and conscientious duty (Erdoğan: "Suriye’deki gelişmelere çok daha fazla seyirci

kalamayız, 2011). In a similar vein, Davutoğlu stated that opposing persecution is a fundamental value of the AKP government. He added that his party's stance on the Syrian issue is based on a reaction to the Bashar al-Assad government’s persecution (Dışişleri Bakanı Sayın Ahmet Davutoğlu’nun TBMM Genel Kurulu’nda, n.d., 2012). Within this context, the AKP government identified “protecting the people of Syria” as “a moral responsibility.” It was declared by the Turkish government that “all Syrian people” would be accepted by Turkey if necessary; this was conceived as a solid messageto the Bashar al-Assad government (48. Münih Güvenlik Konferansı, 2012).

17

In addition to the emphasis on humanitarian and moral responsibility, another emphasis of the AKP government's early political approach on Syrian refugees was the guest theme. In April 2012, Erdoğan stated that asylum-seekers who had to leave Syria had an advantage in comparison with Syrians staying in their country

(Erdoğan: Şam işbirliği yapmazsa, 2012). He further commented that Syrian people would be guests of the Turkish state until they feel safe (Erdoğan başkanlığa yeşil ışık yaktı, 2012; Erdoğan, 2017, p. 49). All in all, the AKP government defined its political approach to Syrian refugees as a willingness to host the victims of a humanitarian crisis with a moral sense of duty. In this early discourse, the refugees were recognized as victims who fleed an authoritarian regime in Syria.

2.1.2. A Qualitative Change in the Turkish Government's Political Discourse on Syrian Refugees in the Post-2013 Period

In August 2012, the number of Syrian refugees in Turkey was approximately measured with a hundred thousand. During this time, Davutoğlu stated that the hundred thousand was an important number with symbolic significance. He also made it public that the Turkish state would continue to accept refugees from Syria (Tarih vermek doğru değil, 2012). In a sense, this statement was the most obvious manifestation of the AKP government's open-door policy towards the Syrian

refugees in Turkey. However, the date Davutoğlu made this statement also marks the beginning of a qualitative change in the AKP government's discourse on Syrian refugees. In the same interview, Davutoğlu expressed that it was not fair that Turkey, Jordan and similar neighboring countries were the only ones to tackle the refugee

18

issue. Subsequently, he asked the UN to take more comprehensive measures about this problem (Tarih vermek doğru değil, 2012).

After August 2012, the Turkish government's press releases and political declarations were beginning to lay stress upon that Western countries and Western-based

international organizations had not fulfilled their responsibilities regarding the refugee issue. These press releases and declarations frequently referred to the

Turkish state’s social assistance to Syrian refugees and financial expenditure put into effect for this assistance. Bashar al-Assad's government had not lost its power in the time period estimated by the AKP government. To add, the number of Syrian

refugees in Turkey by then was increasing exponentially (Aras & Mencutek, 2015, p. 202). The previously declared psychological threshold was already surpassed, and the policy of "zero point delivery" was thereafter initiated in October 2012 to reduce the number of refugees in the country (Aras & Mencutek, 2015, pp. 203-204). In 2014, in parallel with changes in Turkey's foreign policy, an "unofficial close-door policy" was implemented (Aras & Mencutek, 2015, p. 205).

In the World Economic Forum (WEF), which took place in September 2014,

Erdoğan stated that the basic needs of 1.5 million Syrians, such as nutrition, housing, and healthcare, were met by Turkey; he also emphasized that the value of resources used by the Turkish state for asylum-seekers had by then exceeded 3.5 billion dollars (Erdoğan, 2017, p. 25). In the same speech, Erdoğan claimed that prosperous and powerful European countries had only accepted 130,000 Syrians, which to him was a humanitarian and political apathy (Erdoğan, 2017, p. 30). From Erdoğan's point of

19

view, economic support provided by the UNHCR to Turkey was insufficient for the refugee problem (Erdoğan, 2017, p. 30). In this session of WEF, Erdoğan

acknowledged that Turkey was confronting some sociological problems due to accepting a large number of asylum-seekers in its territory (Erdoğan, 2017, p. 30).

In the year 2015, Erdoğan once again emphasized the increasing cost of migration for the Turkish economy. He shamed Western countries and Western-based international organizations such as the UN and United Nations Security Council (UNSC) for their reluctance to take responsibility for the Syrian people's asylum issue (Erdoğan, 2017, p. 143-172-182). There was truth to Erdoğan's statements. In fact, 97 % of millions of Syrian refugees migrated into Lebanon, Turkey, Iraq, and Egypt, largely owing to the closed-door policy followed by European countries (Kap, 2014, pp. 33-35). The amount of economic aid to Syrian refugees made by Turkey had reached 5 million dollars between 2011 and 2014 (Kap, 2014, pp. 33-35). In September 2015, when the number of refugees in Turkey had already reached 2.5 million, Erdoğan declared that Turkey had spent 7.8 million dollars on refugees and he underlined that this situation was "not sustainable" (Erdoğan, 2017, p. 271).

Given these facts, in the early times of the Syrian people’s migration to Turkey, the AKP government considered the case of migration within the context of opposition to the Syrian government. The political statements and declarations of the AKP government, which derived its primary political motivation from this opposition, defined Syrian refugees as oppressed people fleeing an oppressive regime. Moreover, these statements and declarations portrayed the Turkish government as a

20

humanitarian and inclusive political unit that acts with a moral consciousness and responsibility. Within this early political discourse, the only parameters referring to the migration's socio-economic aspects are social and economic aid for Syrian refugees made by the Turkish state.

On the other hand, since 2013, along with the regular increase observed in the number of Syrians who took refuge in Turkey, the AKP government recognizes the migration case as a fundamental social problem. Over time, the AKP government concluded that regular admission of the asylum-seekers was not a sustainable phenomenon. While reaching this inference, the AKP government considered Turkey's sociological issues to be growing with the increasing number of asylum-seekers, economic expenditures made by Turkey for the refugees, and the reluctance of Western countries and organizations to take responsibility for the Syrian people's requests to asylum.

2.2. Construction of Immigrant and Refugee Identity in the News Media

2.2.1. Politics of Representation

Media is a source of information about immigrant groups; it represents immigrant groups through certain representation practices, and these representation practices influence the formation of public opinion about immigration (Bleich et al., 2015, pp. 859-860; Dimitrova et al., p. 2; Esses M et al., 2013, p. 520; Thorbjørnsrud, 2015, p. 772; Van Gorp, 2005, p. 504). By placing the immigrant identity in a negative context on a representative plane, migration news in the media reinforces the

21

"ethnocentric," "nationalist," and "xenophobic" attitudes that gradually become more settled in societies (Gemi et al., 2013, p. 272). Moreover, the media's representation styles of immigrants and the frequency of representations can influence the

qualification of political action on immigration. As Caviedes (2015) highlights, when the media covers an issue frequently and defines it as a social problem, the

probability of defining this issue as a question that requires a political resolution increases in parallel (p. 900). On the other hand, the media’s relationship with public opinion and political action is not one-sided but reciprocal. Media coverage can be influenced by the prevailing public opinion and political actions. The politics of immigration may affect the modes and frequency of refugee representation in the media. As Baker and Gabrielatos (2008) firmly illustrate, it is an observable phenomenon that the refugees are "dehumanized" in the struggle for political

hegemony and reduced to a political discussion topic disseminated through the media (p. 18). Therefore, while examining the refugee representation in the media, it is necessary to consider the media as a vital component of the political structure in which the political parties and the state are other main constituent subjects.

Media portrayal of the refugees as victims may abstract the individual refugee experience from social, political, and historical contexts. One of the classic studies that draw attention to social, political, and historical de-contextualization of the individual refugee experience is Malkki's (1996) cultural anthropological inquiry. Malkki (1996) examines the dynamics of extensive displacement of people and she observes that the media reportage on the refugees have “standardizing discursive and representational forms” (p. 386). Through these forms, the refugees are massively represented in a manner that obscures individual, historical and political

22

circumstances that determine their existing material conditions; they are described as the silenced, speechless and helpless crowd (Malkki, 1996, pp. 386-388). A

generalized depiction of the refugees as people in need of help renders individual experiences of immigration invisible within the mass depiction. Women and children are vital elements of this mass representation since they function as associational elements of femininity and innocence that directly address human sentimentality (Malkki, 1996, p. 388).

In parallel with Malkki, Rajaram (2012) also underlines that such an approach detaches the individual experience of immigration from political, social, and historical contexts. This de-contextualization results in a politicized" and "de-historicized" imagination of the refugee identity, in which the refugee is considered a "mute victim" (Rajaram, 2012, p. 248). According to Rajaram (2012, p. 251), the absence of the political identity of a territorially defined state emphasizes that the refugee is speechless and presupposes the existence of a subject who must speak on behalf of the speechless refugee. The refugee does not have any assigned political subjectivity such as citizenship, and therefore she lacks the "meaningful positive presence" provided by state citizenship (Nyers, 1999, pp. 20-21). Therefore, it becomes difficult to portray the refugee as a mere human being, and the refugee’s presence stands for an "incompleteness" (Nyers, 1999, p. 21).

The stereotypical representations of the refugee as an economic burden, an illegal persona, a threat, or a speechless victim is correlative with the construction of the refugee identity as the other. It is possible to trace to the Christian religious painting

23

the visual patterns of depicting immigrants in the Western imagination (Wright, 2002, p. 54). Due to orientalist assumptions intrinsic to the West, the refugee is usually imagined as an alien subject who enters a given established society from outside. In this context, the refugee identity is constructed as the other by the majority through various representational forms. Therefore, it is not only useful but necessary to address the concept of the other when an analysis of the refugee representations in media is designated as a task.

As Onur (2003) puts it, the other does not fit into the predefined dilemma of “friend and foe” and thus poses a danger to the majority society because it differs from any settled categorization (p. 258). In the process of defining a particular group of people as the other, it is common practice to describe others as members of primitive and pre-modern society, and to set out from the apparent external differences and different behavioral patterns of the others, such as their accent, skin color, religion, and profession (Onur, 2003, p. 259). The majority perceives different life patterns of the other as a threat to the established culture and, since the semantic boundaries of the concept of tolerance are under the monopoly of the majority, the call for

tolerance cannot produce a concrete solution to the perceived threat (Onur, 2003, pp. 260-269).

The media has a decisive role in identifying and defining the differences of the other since it shapes and gives a specific formation to the prevailing public opinion

towards the refugee identity. Through mass disseminated dominant representation practices, the media influences the social context which ultimately dictates how the

24

newcomers will be perceived. In other words, media influences the thoughts, feelings, and behaviors that the majority towards refugees will develop by re-contextualizing the existent social context (Boomgarden & Greussing, 2017, p. 1750). As Uluç (2009) displays, the media identifies who is inside and outside by establishing distinct contrasts between us and the other. Through refugee

representations, the media creates a common sense for the audience that reminds her who she is and she is not (Cottle, 2002). For instance, media content that describes the refugee as a threat can function as a means of reshaping what it means to be American (Fryberg, et al., 2012, p. 11). In this sense, the prevalent refugee representations in the media should be critically re-examined together with the concept of the other.

2.3. Dominant Representations of Syrian Refugees in the Turkish News Media

Several scientific studies analyze the prevalent representations of Syrian refugees in the Turkish news media. The Turkish press's general perspective towards Syrian refugees is mostly non-exclusive; 48.16 % of refugee news published by the Turkish media outlets have a positive approach toward the refugees, and 39.42 % of the news show a balanced attitude (Paksoy & Şentöregil, 2018, p. 246). A comprehensive report by Hacettepe University Migration and Politics Research Center (HUGO) demonstrates under the guidance of statistical data gathered from 21 national and 56 local newspapers in 10 Turkish provinces that Turkish news media have a general tendency to represent Syrian refugees as “vulnerable” people on the one hand, and as “criminals” and “economic burden” on the other (Center, 2014, p. 78).

25

Göker and Keskin (2015, p. 243) observe that the most prevalent representation form of the refugee identity in the Turkish news media is built on the victim theme.

Dimitrova et al. (2018, p. 9) detect the co-presence of "humanitarian frame" and "victim frame" in Hürriyet and Cumhuriyet, but they note that "humanitarian frame" is more frequent than "victim frame." In this parallel, the representation of Syrian refugees in Turkish media oscillates between depicting refugees as the victim, as an economic burden, and as a threat. While this is the case, the views and expectations of Syrian asylum-seekers about their own conditions are barely mentioned in the Turkish press, as the prevailing news practice is based on the objectification of the refugees by the politicians (Paksoy & Şentöregil, 2018, p. 253).

The variable whether newspapers are opposed to, or supportive of, the government's policies towards the Syrian refugees affects the representation of the refugees in the Turkish news media. In contrast with Gölcü and Dağlı’s (2017) argument that both the Turkish mainstream and pro-government newspapers represent Syrian refugees chiefly as illegal figures, it is observed by Pandır, Efe and Paksoy (2015) that the segments of Turkish press that is closer to the government, such as Sabah, represent refugees as destitute and needy people. By representing refugees as needy

individuals, pro-government media praise the government's political actions and humanitarian aid supplied to indigent refugees. For instance, as Boztepe (2017) points out, the news broadcasting of pro-government television channel Kanal 7 aims to legitimize the government’s policies for the case of Syrian refugees by depicting the Turkish government as a political actor that takes responsibility for refugees who are conceived as “our victim brothers.” Similarly, the pro-government newspaper Yeni Şafak contains news justifying the government's policy on Syrian refugees,

26

depicts Syrian refugees as needy, and illustrates the Turkish government as an inclusive political actor (Göker & Keskin, 2015, pp. 245-249). The manner in which Yeni Şafak makes news is most notably marked by an intent to alter public perception in favor of the now long-popular opinion that asylum-seekers have been an

"economic burden" for Turkey (Göker & Keskin, 2015, pp. 249-250).

On the other hand, some media outlets of Turkish oppositional news media

predominantly are apt to represent the Syrian refugees as crime-oriented people and an economic burden on Turkey. The newspapers Sözcü and Zaman exemplify such a tendency (Pandır et al., 2015). As another illustrative example of Turkish

oppositional news media, the news broadcasting of Turkish neo-nationalist television channel Halk TV criticizes the government’s policies on the case of Syrian refugees, and it also usually portrays the refugees as an economic burden on Turkey (Boztepe, 2017). In a like manner, the oppositional Cumhuriyet frequently includes political criticism in refugee news and indirectly criticizes the government by portraying the Syrian refugees as invaders (Göker & Keskin, 2015, pp. 245-249). The news practice of Cumhuriyet follows an opposite direction compared to Yeni Şafak, and it depicts the Syrian refugees as an “economic burden” for Turkey.

This study will make meaningful contributions to the relevant scientific literature from various angles. First, there is no scientific study examining the media representations of Syrian refugees in a socialist newspaper. The examination of Evrensel will be the first example of such an examination. Second, the scientific studies which analyze the refugee representation in the Turkish news media generally

27

choose their sample newspapers according to the daily circulation rates. By selecting sample newspapers according to the political and ideological orientations of the newspapers and analyzing the news content in a politico-ideologically comparative approach, this study provides a unique perspective to the existing literature on refugee representation in Turkish news media. Last but not least, the study

approaches its object of study, i.e., the representation of Syrian refugees in Turkish media, from a particular socio-political viewpoint by dividing the content analysis of the news into two main periods, which are before and after the mass settlement of Syrian refugees in Turkish cities. Such a research approach, which was not

previously applied to analyses concerning the object of this study, will prove crucial to rethinking the object of this study in relation to the socio-political fabric of Turkey.

2.4. Dominant Representations of Immigrants and Refugees in Western Media

In Western media, refugee representations by negative connotations, such as the connotation of threat, have increased over the past fifteen years (Esses M et al., 2013, p. 520). These negative connotations can be described as social actions associated with crime, and they trigger fear within socio-psychological memories of the societies. The lack of expertise in the field of journalism on migration, the limited nature of time allocated for the broadcast process, and the fact that infertile news has more news "value" than well-researched articles channelize journalists and

newspapers alike to highlight more controversial aspects of immigration (Gemi et al., 2013, p. 266). The motivation to sell the news at all costs produces news on

28

immigrants/immigration with shallow and superficial content. Some newspapers even send their reporters to the field with the deliberate intent to make negative and sensational news about immigrants (Gemi et al., 2013, pp. 270-272).

Correspondingly, Western media depicts refugees primarily as vulnerable

individuals, crime-related piles, and a burden on the economic welfare of refugee-receiving countries. In the theme of economic welfare, the emphasis on the exhaustion of public resources -open to the consumption of the host country's citizens- by refugees has an active role (Boomgarden & Greussing, 2017, p. 1751). Insecurity, diseases, drug use, rioting, sexual promiscuity, terrorism, and religious fanaticism are only some of the widespread social phenomena that immigrants are associated with in the mediatic sphere (Balabanova & Balch, 2010, p. 383). For instance, Canadian media associate refugee claimants with terror activities and portray refugees as people who endanger Canadians' health by spreading epidemics (Esses M et al., 2013, pp. 525-528). Similarly, Dutch newspapers prefer to use the adjective "illegal" with a ratio of over 95 % to describe "unauthorized migrants" (Brouwer et al., 2017, p. 108).

On the other hand, depicting immigrants as pure victims is another far-reaching representation practice, which should be considered when the refugee representations existing in the media are examined. This representation practice would present a “personalized” and “emotionalized” perspective on the refugees; however, it would also manifest a “pejorative” approach that delineates the refugees as dependent people in need of help (Boomgarden & Greussing, 2017, p. 1751). Chouliaraki and

29

Zaborowski (2017) examine media representations of refugees in eight different European countries, and they point out that victim and threat are the most prevalent interchangeable adjectives preferred to depict refugee identities in the contemporary European media. In fact, the prevailing tendency in European media is to resort to either a narrative of victimhood, which portrays refugees as vulnerable individuals, or the narrative of threat, which depicts refugees as active agents of societal crime (Chouliaraki & Zaborowski, 2017).

Along these lines, it is apparent that different news framings that contradict each other in terms of content can be simultaneously broadcasted in the national media of countries. For instance, three predominant news framings for the refugee news co-existed in the Australian media during the country's 2001 elections; two of these themes were the humanitarian crisis and border protection (Gale, 2004). The first theme highlighted the "human sufferings" and the misery caused by immigration, and presented Australia as a "compassionate liberal democratic Western nation" that embraced the destitute and disadvantaged people (Gale, 2004, pp. 327-328). The second theme considered border protection as the national right of the country; it associated the migrants trying to cross the Australian border with illegal activities, and considered the open borders of Australia as a danger to the national interests of the country (Gale, 2004, p. 329). Again, 46 % of the news published in the British print media describe migration as a "threat" and immigrants as "villains," while 38 % of the news prefer to follow the “victim” frame (Crawley et al., 2016, p. 5).

30

The political and ideological orientations of the media outlets affect the media representation of refugees and immigrants. For example, even though immigrants are less prone to commit crimes than the native-born in the context of the US (Center I. P., 2007, p. 2), the conservative newspapers represent the immigrants as a threat to the public more frequently than their liberal counterparts (Fryberg, et al., 2012). Moreover, media representation of refugees can be conditioned by period-specific effects of socio-political events. Specific events may have short-term or long-term effects on the prevailing media framings of refugee news. For example, along the Aegean shore, the photo of Syrian baby Alan Kurdi's dead body3 resonated in the world press, and it made the refugee crisis a more burning agenda in the political panorama of the world (Efe et al., 2019, pp. 7-8). During this period, the prevailing theme within the European media coverage was humanitarianism that emphasized the “care of new arrivals.” Notwithstanding, the media then has mainly focused on the measures to be taken against the refugees after the November 2015 Paris attacks (Georgiou & Zaborowski, 2017, p. 8). Although the securitization of immigration was a more explicit phenomenon for the media in France and Italy after the 1990s, British newspapers have a greater tendency than these two countries’ press to frame immigration around the theme of physical danger, and it is possible to argue that this is related to the 7/7 London Bombings of 2005 (Caviedes, 2015, pp. 901-906).

Just as importantly, media representation of refugees is also conditioned by the responses to the questions as to (1) whether refugees have an opportunity to pass

3 Kurdi was a three-year-old Syrian baby who lost his life while trying to reach the Greek territory

with an inflatable boat with his mother and brother. The photograph of the baby's corpse washed up on the shores of Bodrum caused the question of Syrian refugees to become a much more urgent and burning issue in Turkish and international public opinion.

31

through the borders of a given country and (2) whether refugees will be permanent within these borders. As Heidenreich et al. (2019) argue, the dominant media representations of refugees are mostly about refugees’ impact on the economy and welfare of the receiving country if the refugee case is predicted to be a long-term problem. For instance, the prevalent theme of Hungarian media-framing on refugee issue was “international humanitarian aid” before May 2015; however, as refugees moved beyond the borders of Hungary, the humanitarian emphasis was replaced with the frame of “crime and terrorism” (Heidenreich et al., 2019, p. 178). Likewise, the frequency of humanitarian emphasis on refugee issues in the Swedish media decreased from January 2015 to December 2016, the time period during which the European refugee dilemma reached a peak; on the other hand, the humanitarian emphasis began to increase again as soon as the dilemma met a short-term resolution (Heidenreich et al., 2019, p. 178).

2.5. Media Framing Theory and Representations of Immigrants and Refugees

The early cornerstones of framing theory can be traced back to Goffman (1974, pp. 10-21), who argues that people benefit from "schemata of interpretation" to

contextualize information that they perceive as they receive. According to Goffman (1974, pp. 10-21), people need to identify information to make sense of the events in their environment by interpretation; the "schemata" is the essential instrument aiding them throughout this process. As articulated in communication research, the concept of media framing points to how the media influences citizens' interpretation of social occurrences realized by framing certain aspects of social events while omitting several other facets of events. The editorial management and staff of news media

32

have a crucial role in molding political reality by framing peculiar aspects of social events. In this context, framing effect can be defined as an extension of the agenda-setting theory since it leads the public towards interpreting and discussing specific features of the external reality (McCombs & Shaw, p. 176). The context of the frames may be affected by organizational, individual and ideological variables (Scheufele, p. 107).

Gamson (1989, p. 158) elaborated that it is possible to delineate multiple different stories about an individual case. A frame manifests itself as a "central organizing idea" which is intentionally designated by the sender and which determines in a text what is relevant and important (Gamson, 1989, pp. 157-158). On the other hand, detecting media frames at first glance may not be easy even for experienced

journalists who produce news reports, let alone the average reader. Gitlin (1980, p. 7) stresses that what matters for media frames is composed of "tacit theories;" thus, media frames can be perceived as common sense at first glance. By employing "persistent patterns of cognition, interpretation and presentation, of selection, emphasis, and exclusion," journalists produce their reports without challenging the hegemonic values and interests of the sovereign organizations (Gitlin, 1980, p. 7). Since this production process is perceived as a journalistic routine per se, journalists may not be aware of their tendencies in question (Gitlin, 1980, p. 7). In this context, a media researcher should conduct a detailed study to find the frames embedded in the texts.

33

For the process of exploring media frames, Entman (1993, p. 52) classifies four fundamental features of the frames. According to Entman (1993, p. 52), frames outline problems, pronounce causes, conduct moral judgments and recommend solutions. A sentence in a text under the scope of examination may meet all of these features or the whole of the sentences may not meet any of these features at all (Entman, 1993, p. 52). Keywords, stock phrases and sentences may function as elements constructing the frame (Entman, 1993, p. 52). Therefore, it is necessary to reveal these textual elements and the thematic and semantic patterns they establish between themselves while discovering frames. As Odijk, Burscher, Vliegenthart and de Rijke (2013, p. 334) emphasize, content analysis is the most dominant research method when examining the implementation of frames in the news. Researchers can manually add some relevant questions to their coding sheets and note their

34

CHAPTER III

METHODOLOGY

This chapter explains the study's research method in detail and discusses the potentials of and criticism towards the content analysis method on media research.

Content analysis is operated as this study’s research method. A media research process on refugee representations involves discovering which types of affairs obtain the most attention and how the media formulate them (Caviedes, 2015, p. 897). In this parallel, the study aims to determine the media frames constituted by the

newspapers’ news content and explore their socio-political contexts through content analysis of the newspapers.

In total, 595 news articles and 165989 words are included in the content analysis.

Table 1. Number of Analyzed News and Total Word Count

Newspaper / Period Number of Analyzed

News Articles

Word Count

Sabah / 2011-2013 90 22732

Sabah / 2016-2018 90 20657