Retail

development

in

Turkey:

An

account

after

two

decades

of

shopping

malls

in

the

urban

scene

Feyzan

Erkip

a,1,

Burcu

H.

Ozuduru

b,*

a

BilkentUniversity,FacultyofArt,DesignandArchitecture,DepartmentofUrbanDesignandLandscapeArchitecture,Ankara06800,Turkey

b

GaziUniversity,FacultyofArchitecture,DepartmentofCityandRegionalPlanning,CelalBayarBlv.,Maltepe-Ankara06570,Turkey

Abstract

Thesocial,economicandenvironmentalimpactsoflarge-scaleretailoutletsonexistingretailandurbansystemshavebeen extensivelydiscussedintheplanningliterature.ThisarticledocumentsthelasttwodecadesoftransformationinTurkey’sretail sector,whichhavebeencharacterizedbyamoreorganizeddevelopmentofthesectorthantraditionallyexisted.Webeginour analysiswiththelate1980sandearly1990s,whenmore-liberalandoutward-lookingpoliciesbegantoemergeinTurkisheconomic policy. Changes inthe economy and relatedlegislation prepared a base forthe subsequent transformationsof that decade, culminating,especiallyinlargecities,inthedevelopmentofshoppingmallsasalternativeretailspacestotraditionalmarketsand storesonashoppingstreet.WebelievethattheTurkishcaserevealsspecificaspectsofresistance,adaptationandchange,andthus needsadetailedaccount.Afterprovidingageneralpictureofretailingand itstransformationinTurkey,weprovideempirical evidencefromAnkara,thecapitalcity,throughwhichallimportantdynamicsofretailingareexemplified.Tothisend,weaskthe followingquestions:WhataretheevolvingprocessesbehindtheexistinglocationpatternsofshoppingcentresinAnkara?Whatis theextentofthechangeindefinitionofthenewpublicrealm?Howdostreetretailerssurvive?Whoaretheactorsandwhataretheir approachestowardsretailplanninginTurkey?Theanswerstothesequestionsmayprovideimplicationsforurbanpolicyandretail planninginTurkey.Thecasemayalsobeinterestingforcountriesexperiencingsimilarpatternsofchangeanddevelopment,thatis, wheretheglobalizationprocessinretailingandconsumption-relatedsitesbeganlaterthaninothercountriesandobserved fast-paceddevelopment.

#2014ElsevierLtd.Allrightsreserved.

Keywords: Retaildevelopment;Shoppingcenters;Resilience;Urbanpolicy

Contents

1. Introduction ... 2

2. Theoreticalbackground ... 4

2.1. Theplanningperspective ... 4

2.1.1. Impactsontheuseofpublicspaces... 5

www.elsevier.com/locate/pplann

*Correspondingauthor.Tel.:+903125823701;fax:+903122320586.

E-mailaddresses:feyzan@bilkent.edu.tr(F.Erkip),bozuduru@gazi.edu.tr(B.H.Ozuduru).

1Tel.:+903122901592.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.progress.2014.07.001

2.1.2. Urbansprawl... 5

2.1.3. Sustainabilityandtraffic-inducedenvironmentalproblems... 6

2.2. Theresilienceofurbansystems... 6

3. RetaildevelopmentinTurkey:definingperiods... 7

3.1. Thefirstperiod:globalimpactsontheorganizationoftheretailsector,1990–2000... 8

3.2. Thesecondperiod:theinfluxofshoppingcentres,2000–2010... 11

3.3. Thethirdperiod:alaissez-faireapproachbythecentralgovernment,andmarketdominancein2010andbeyond 15 4. Actorsandresiliencestrategies... 16

5. ThecaseofAnkara:empiricalevidences ... 18

6. RetailplanninginEuropeancountries:lessonstobelearned... 26

7. Concludingremarks:implicationsforthefutureofretailplanninginTurkey ... 28

7.1. Regulationoftherelationshipbetweenlarge-scaleandtraditionalretailers... 28

7.2. Provisionofdefinitionsandstandards... 29

7.3. Ruleset-upforsite-selectionfeasibilityanalysesandrelationshipstodevelopmentplans ... 29

7.4. Arrangementoftherolesofpublicandprivateactorsinthedevelopmentprocess... 29

References ... 30

1. Introduction

Thesocial,economicandenvironmentalimpactsof large-scale retail outlets on existing retail and urban systemshavebeenextensivelydiscussedintheplanning literature(Guy,1998; Knox,2008;Ozuduru,Varol, &

Ercoskun, 2014; Southworth, 2005; Teller, 2008).

Despitetherelativelylateinfluenceofglobaleconomic trendsinTurkey(beginninginthelate1990s),foreign investmentpenetrated thecountry’s retailsectorquite quickly. This development attracted the attention of scholarsregardingvariousaspectsofTurkishretailing, andthesubjecthasgeneratedagrowingliterature(see, forexample,Erkip,Kizilgun,&MuganAkinci,2013; Erkip,Kizilgun,&MuganAkinci,2014;Erkip,2003, 2005; Ozuduru & Varol, 2011; Ozuduru et al., 2014; Tokatli&Boyaci,1998).Thisarticledocumentsthelast twodecadesoftransformationinTurkey’sretailsector, which have been characterized by a more organized development of the sector than traditionally existed. Althoughmanyaspectsofthistransformationhavebeen explored,herewepresentamorethoroughanalysisof thespecificperiodsofretaildevelopment,eachofwhich experiencedadifferentkindofchange.Inthisstudy,we explorethistopicusingvarioustheoreticalperspectives onurbanretailing.

Webeginouranalysiswiththelate1980sandearly 1990s, when more liberal and more outward-looking policiesbegantoemergeinTurkisheconomic policy. Changes in the economy and related legislation preparedabasefor the subsequenttransformationsof thatdecade, culminating,especially inlarge cities, in thedevelopmentofshoppingmallsasalternativeretail spacestotraditionalmarketsandstoresonashopping

street. Globalculturalinfluencesandmassmediaalso madeconsumptioninshoppingmallsmoredesirablefor Turkish citizens. Further, improved economic condi-tions andcreditoptions providedTurkishpeoplewith theopportunitytopurchasegloballybrandedproducts. Similar tothe situationinmanyothercountries,these modern and organized retailers threatened the liveli-hoodofsmall-scale,traditionalshopowners.However, some small retailers viewed the changes as an opportunity to modernize and develop strategies to make themselves more resilient. We believe that the Turkish case reveals specific aspects of resistance, adaptation and change, and thus needs a detailed account. The resilience concept in relation to urban systemshasevolvedinmanyways,andinthispaper,we discuss the strategies of both small- and large-scale retailers (i.e. traditional retailers and shopping mall developers)duringthepastdecadesinrelationtourban development. The resiliencelevelof a city’sretailing sectorcanbeincreasedbynewurbanpolicies,andtheir majorobjectivesshouldbespecificallysetoutsoasto integratetraditional retailersinto the urban sceneand increasecitycentres’vitalityandviability.Traditional retailersarethepillarsofurbanlifeincitycentres;with the current influx of new shopping centres, older retailers can become more resilient by adopting new marketing strategies in the ever-changing, dynamic retail market.These mallsshould beabletore-invent themselvesandremaininthemarkets.

Theperiodofshoppingmalldevelopmentthatbegan in the late 1980s in Turkey continues today, with increasing competition between new shopping malls causingthedecayoffirst-generationmalls,asexpected. An unexpectedoutcomeof thistrend,however,is the

insistence of central and local planning bodies and authoritiestoallocateeverypieceofvacantlandinthe urban core, including green areas or public land designated for other uses, to shopping mall develop-ment.Webelievethatthelasttwodecadesofshopping malldevelopmentreflectdifferenteconomicandsocial dynamics, thus we analyze them separately in this paper.

The first period of retail development in Turkey occurredmainlybetween1990and2000,duringwhich shoppingmallsemergedaspartofthesceneanddaily life of large cities. In the second period, between 2000and2010,theyflourishedinquantityandquality, and citizens created a huge demand for them. The reasons behind this demand were not completely economic; the modernity provided by these retail spaces was a major appeal (see Erkip, 2003 for a detailed account of this issue). In the same period, shopping mallinvestments extendedto smallercities. The share of international capital in Turkey also increased, indicating a growing interest from foreign investorsanddevelopersinshoppingmalldevelopment. These two periods also witnessed the resilience strategies of actors in the sector. In the first period, actorsandcitizensadaptedtosectorchanges,andinthe second period they developed resilience strategies to survive and/or thrive under the new competitive conditions. Changes to the retail sector in the first two periods occurred with little comprehensive plan-ning. Now,athirdperiodseemstohavebegun,andit requires a more holistic strategy. We explore the indicators ofthisclaiminthefollowingsections.

From1990to2010threegroupsofshoppingcentres emergedinTurkey. Thoseinthefirstgrouparecalled integrated shopping centres, which are small in size (between2500and5000m2)andlocatedclosetocity centres.Shoppingmallsinthesecondgrouptendtobe locatedinthesuburbsand/orareindividuallystructured centres designed separately from their surroundings. Thethirdgroupiscomposedofvariouslanduses,such as offices,entertainmentvenues, residences andretail stores. Most new shopping malls today comprise the thirdgroup:large-scale‘urbantransformationprojects’ with customers ready to shop there. For this reason, thesestructurescansustainthemselvesmoreeasilythan first-generation shopping centres. Since national and local developers in Turkey are mostly from the constructionsector,thissituationprovidesan opportu-nity to develop construction projects that involve various uses. New subdivisions are being built in various urban areas, both in the core and on the periphery.

The competitionbetween newconsumptionspaces and traditional ones has important impacts on urban publicspaces.Theemergenceofshoppingcentreshas changedtheconceptof thepublic realm,andthusthe designprinciplesofpublicspaces;thesecentresoffera climate-controlled enclosed space where people can more comfortably do the things they used to do in outdoorpublicspaces,i.e.,windowshop,eatanddrink, meetpeople,etc.Consideringthesegregationbetween womenandmen,childrenandadults,richandpoor,and religious andsecular inTurkey’spublic spaces, these new mall spaces seem to offer more-inclusive areas. Citizens’toleranceforeachother,especiallyforthose overlookedbymodernandeducated groups,seemsto increaseinthesepublic, butprivatelyowned environ-ments,which thencreate a newkind of public space

(Erkip, 2003). Women find a more secure place to

browse;childrenareallowed,andevenencouragedby theirparents,tospendtimeinthesecontrolled spaces andreligious andsecular peoplesharethe mallspace more tolerantly because they see it as a territory of consumption only. There is surveillance in all such spaces,andinthe Turkishcase,thisaspectrevealsan interestingdistinction:manypeopledonotmindbeing observedbecause theybelievesuchsurveillanceisnot intended for them, but for others (Mugan & Erkip, 2009). These prevailing characteristics of shopping malls necessitate further discussion on the definition andfeaturesofpublicspacesinTurkey,atopicthatwe discuss in general in this paper, saving a detailed explorationfor afuturestudy.

Urban density and the ratio of young people in Turkey are quite high compared to other European countries. Thesefacts create adynamic use of urban spaces and the potential for the simultaneous use of globally designed consumptionspaces (such as shop-ping malls) and traditional street retailers in urban centres,aswellasforusingopenspaces(suchasparks) forleisureactivitiesandsocializing(Erkipetal.,2014). Turkishurban planninghasbeen controlled bythe central government sincethe beginning of the 2000s, and this includes retail planning. Attempts at special legislation,firstin2004andthenin2006,torestrictthe impact of shopping centres on street retailers was blockedbythepowerbehindthelargecapitalinvested inshoppingcentres,onthegroundsthatitwouldlimit their operations and decrease their profit margins. However, such laws should take into account other planningregulations.Forexample,tomaintainalively central business district (CBD), which research has shown is vital to a healthy urban core, municipal governments should provide larger pedestrian areas,

revisecar-orientedpolicies,increaseparkingandpublic transportationincitycentres,andofferclean, comfor-tableandsecuregreenareaswithamenities(Ercoskun & Ozuduru, 2011). Such policies would increase the attractionlevelofCBDsandcontributetotheresilience oftraditionalretailers.Withouttheseaids,independent retailers are left vulnerable, insecure and usually unorganized; they often develop individual resilience strategiestosurviveinacompetitiveretailenvironment. Retailer strategies in the absence of comprehensive planning, however, are usually reactive instead of proactive, and while successful against slow-burn changes, they are generally not capable of resisting shocks.Aholisticandcentralretailpolicyinvolvingall actors, including citizens, is necessary to maintain a lively retail environment, characteristic of traditional Turkishretailing.Turkishplanners couldbenefitfrom theexperiencesofothercountries,whichareinalater stageofshoppingmalldevelopment.Sucheffortswould makeTurkishcitiesmoresustainableandlivableaswell as making the sector more resilient to global and/or domestic crises and changes. This paper addresses issues raised by other countries’ retail development experiencestoassist theTurkishcase.

AnothersignificantfactorforTurkeyisitsongoing andlengthyprocessofEuropeanUnion(EU) member-ship,whichmakesitdifferentfromothercountriesthat experienced shopping mall development in the same period.AlthoughrelationsbetweentheEUandTurkey areunreliableatthistime,thepotentialofmembership inthefirsttwo periodsforced manysectors, including the retail sector, tomodernize and better organize to satisfyEU requirements (EIU,2009).Somecountries whoenjoymore-comprehensiveretailplanningareEU members,andtheirexperiencesdemonstratetherolethe public sector can play in retail planning and offer a frameworkthatcan helpintegrateretailplanning into urban policy. (For detailed analyses of selected countries’ retail planning schemes, see Cities, 2014, specialissue).

Our premise can be framed with the following questions in relationto the above-mentioned periods: Howdid the retailsector transform in Turkey? What werethemotivesforchangeindifferentperiods?How did actors react and respond to the changes in the sector?Howdidthesechangesinfluenceurbanlanduse patterns?Whatwere theroles ofplanningbodies and legislation in shaping the sector and urban develop-ment?

Afterprovidingageneralpictureofretailingandits transformation in Turkey, we provide empirical evidencefromAnkara,thecapitalcity,throughwhich

allimportantdynamicsofretailingareexemplified.To thisend,weaskthefollowingquestions:Whatarethe evolvingprocessesbehindtheexistinglocationpatterns ofshoppingcentresinAnkara?Whatistheextentofthe change indefinitionofthenewpublicrealm?Howdo streetretailerssurvive?Whoaretheactorsandwhatare theirapproachestowardsretailplanninginTurkey?The answerstothesequestionsmayprovideimplicationsfor urban policyand retail planning inTurkey. The case may also be interesting for countries experiencing similar patterns of change and development, that is, where the globalization process in retailing and consumption-related sites began later than in other countriesandobservedspeedydevelopment.

2. Theoreticalbackground

To evaluate the impacts of shopping malls on traditionalretailformsandurbanlanduseinTurkey,we adoptabroadperspective,composedofcomponentsof differenttheoriesonurbandevelopment.Thefollowing sections outlinethesetheoreticalperspectives,eachof which focuses on different aspects of urban develop-mentinrelationtotransformationsintheretailsector. 2.1. The planningperspective

Development of a shopping centre requires a comprehensive analysis of its impact on the built environmentandurbanliving.Selectingan inappropri-ate site can create traffic congestion, environmental degradationandurbansprawl,aswellasdispositionof employment,independentretailersandotherresources. The retail sector is one of a city’s major economic activities,which(1)createsemployment,(2)isamajor sourceofincomethroughthetaxesitgeneratesand(3) reflectsthecommunity’sviabilityandvitality(Mazza& Rydin,1997).Therefore,retailsalescanberegardedas afunctionofseveralpoliciesinurbanplanning,suchas urbancontainment,thepriceofagriculturallandandthe percentage of government and municipality revenue frompropertytaxesandgeneralsalestaxes.This multi-facetedperspectivemeansthatshoppingcentresshould be a major topic in urban policy-making because of theireffectsonsomanyaspectsof citylife.

As an example of economic impacts, shopping centreschangethequalityof employmentintheretail sector. In many countries, traditional stores cannot surviveduetocompetitionfrommalls;somemoveinto ashopping centre, while othersclosetheirbusinesses and becomean employee of a store inamall selling similarproductsandservices.Someretailersclosetheir

stores and find unrelated (or no) employment. Much retail employment is thus driven to the urban fringe, where the numberof shoppingcentres is higher. The standardization of work through big-box training programmesdiminishestheimportanceofemployees’ personalabilities, andthenature of relationshipswith customers is less personal compared to traditional stores.Neumark,Zhang,andCiccarella(2006)findthat theopeningofaWal-Martstoredecreasesretailwages by 7.5%,with eachWal-Mart workerdisplacing 1.5– 1.75 other retail workers in the region. Similarly,

Bernstein Research (2005) finds that big-box stores

displace up to six local businesses, increase retail employmentbutsubstantiallydecreasewagelevelsand destroyhistoricalcommercial areas.

Inthefollowingsections,weanalyzetheimpactsof shopping centre development within an urban policy perspective. The impacts of shopping centres on (1) public spaces,(2) urbansprawl,(3) sustainabilityand (4) traffic-inducedenvironmentalproblemsareamong themajorissuesweconsider.(Foradetaileddiscussion ofthisperspectivewithafocusontheUScanbefound

inOzuduruandGuldmann(2013).

2.1.1. Impacts ontheuseofpublicspaces

The problem of social exclusion appeared when privatespacesforshoppingweredevelopedandpeople begantospendmoretimeinthesespacesandlesstime intraditional shoppingstreets. Shopping centres have becomethenewpublicspacesofsuburbanareasandof urban cores (Banerjee, 2001; Erkip, 2003; Garreau, 1992;Ghosh&McLafferty,1987).However,theyare owned by private entitiesand are not,in fact, public spaces.Erkip(2005)showsthatthesespacesdoexclude somepeopleinTurkey,notonlyonthebasisofincome but also on the basis of social class. Other scholars emphasizetheimportanceofaccessibleretailfacilities byallsegmentsofsocietyandnotethatanincreasing number of shopping centres discriminate against the mobilityimpaired, theelderlyandlow-income house-holds because the malls are only accessible by car (Barata-Salgueira & Erkip, 2014; Guy, 1998, 2007).

Guy(2007)alsopointsoutthatsuchexclusioncanbe

controlled by enhancing local shopping and public transportation policies and recommends preserving localshoppingintraditionalurbandistricts,improving poor-quality retail facilities and supporting surviving businessesthroughurbanpolicies.

StaeheliandMitchell(2006)showthatmallowners

do not consider their shopping spaces as gathering placesornewkindsofdowntowns,anddonotallowfor thegamutofuserrightsthatatrulypublicsettingoffers.

They suggest that shopping centres are purposefully builttolimitaccessandaredesignedtoattractacertain marketniche,providingafeelingofsafetyandcomfort tothetargetedconsumers.Theyalsosuggestthatyouth access isrestricted becauseof the associated challen-ginganddisruptivebehaviour.Thisaspectisverifiedby

MuganandErkip(2009)intheTurkishcontext.

Southworth’s(2005)findings,basedonfieldsurveys andin-depth interviews, imply thatthe newforms of suburban public spaces share similar attributes with mainstreets.Theauthordefinesvariouselementsofthe suburban public space, including main streets, strip malls,atriummalls,townscapemalls,mainstreetmalls, malled main streets and hybrids, and analyzes their implications for urban design in terms of pedestrian connectedness; comfort;visible andaccessible transit alternatives;placesforsocialactivityservingpeopleof variousages, ethnicitiesandsocialgroups;mixed-use characteristics; streetscale for comfortablepedestrian crossings; controlled or uncontrolled automobile access; parking; scale; design and transparency to engage peoplewiththe place. ShamsuddinandUjang

(2008) attempt to identify place attachment and the

influence of place identity on traditional shopping streets,andtheyspecifytheattributesinfluencingplace attachment as accessibility, vitality, diversity/choice and transaction, among others, and conclude that traditionalstreetsenhanceplaceattachmentand mean-ingincontrasttootherretailspaces.Standardizationin the design of shopping malls leads to a controlled experience,whereaspublicspacescanprovidevarious levels of publicness through different spatial and physical features.Nemeth (2009) suggeststhe impor-tanceofprivatelyownedpublicspacesinthefutureof urban spaces and proposes that management should provide physical features that will help increase the levelofaccessibility anduseinsuchspaces.

2.1.2. Urbansprawl

Developersallovertheworldhavebuiltmore out-of-coreshoppingcentresinrecentyearsthaninthelasttwo decades, predicting thatsuburbs would welcome this newretailspace(Knox,2008;Lang,2003).Incontrast, residents,environmentalists andplannershave argued thatanexcessiveamountofsuchretaildevelopmenthas been accompanied by impervious parking areas that increase (1) storm water runoff, washing nitrogen, heavy metals and sediments into urban streams; (2) localurbanheat-islandeffectsand(3)shoppingtravel, withassociatedincreasedpollutionandgreenhousegas emissions(NOACA,2000),andthatthenumberofsuch developments should be reduced. The reliance of

consumers on cars encourages developers to build larger parking lots, creating stand-alone shopping centres surrounded by adesert of parking (Beyard & O’Mara,2005).Barata-SalgueiraandErkip(2014)also notethatsprawlcausesmanyenvironmentalandsocial problems,withitsimpact,suchasincreasedcaruseand lackof pedestrianaccess toretailspaces. Inaddition, malls’ box-like architecture increases their negative impacts because they are built to be economically efficientandfunctional,notenvironmentally friendly.

Althoughurbansprawlfollowsdifferenttrajectories in different countries, there is evidence thatcompact citiesdecreasethe ecologicalfootprint of urban areas andreduceenergyconsumptionandpollutionbecause theyencourage walking, have improved public trans-port access (Bromley, Tallon, & Thomas, 2005), are developedinsmallerlandparcelsandbuildingsandare accompanied by smaller parking facilities. Similarly, ‘‘new urbanism’’ design offers alternative uses for parkingareas,suchas‘‘liningaparkingdeckwithtiny retailspacesoccupiedbyoffbeatandartsybusinesses’’ (cnu.org,2007),andencourages traditionalmixed-use citycentres,withsmallerretailstores,morelandscaping elementsandfewerparkingspaces.

2.1.3. Sustainabilityand traffic-induced environmentalproblems

The environmental impacts of suburban shopping centresincludeissuesrelatedtothelowcurbappealof retail buildings and the above-noted environmental problemscausedbyparkingareasandincreasedvehicle travel. Notably, the environmental impact of a retail centre extends beyond local jurisdictions (NOACA, 2000).Retailing is oneof the most traffic-generating land uses, andretail centres builton the outskirts of towns and cities on major traffic arterials and transit interchangestoachievehighvisibilityandaccessibility contributetothis problem.Additionally,heavy traffic andtheturningmanoeuversnecessarytoaccessamall generateahighernumberofaccidents.Onceasuburban retail centre is built on a main transportation route, traffic load increases and the transportation network evolvesconsiderably(Evans-Cowley,2005).

The literature extensively discusses the issue of shoppingtravelduetotheincreaseduseofcarsandthe subsequentincreaseofcarbondioxideemissions.Using cars instead of public transport for shopping travel increasesenergyconsumptionandpollutionemissions

(Mazza andRydin, 1997).Banister (1997) pointsout

thattherewasa36%increase incarownershipacross Europe between 1980 and 1990 and that transport accountsforoveraquarterofcarbondioxideemissions

intheUK.Therefore,aneffectiveretailplanningpolicy should be designed to minimize the use of private vehicles and to promote developments at readily accessible locations with alternative means of public transportation, or to develop clustered retail units to encourage multi-purpose trips (Guy, 2007). Ibrahim

(2002) explains that Singapore has adopted an

integrated retail and transport development policy, whichregulatestheuseofprivatecarsandencourages the useofpublic transport.

Theimportanceofshoppinglocallytoreduce traffic-relatedpollutioniswelldocumented.Banister(1997), investigating density, settlement size and location of employmentfacilities,impliesthatlocalshoppingareas shouldbepromoted.Hepointsoutthatahigher-density locationcanreducetriplengthsaswellastheproportion oftripsmadebycar,andthatitisalsoeasiertoprovide publictransportservices tosuch locations.

2.2. The resilienceofurbansystems

Resilience is a concept borrowed from ecological research and developed by researchers in the social sciences,mainlygeographyandeconomics(seeMuller,

2011 andLang, 2011for detailed discussions onthis

topic). Simmie&Martin (2010,p. 28),claimingthat thereisnouniversallyaccepteddefinitionofresilience, propose an ‘‘adaptive model’’ to understand how geographical regions adjust to disturbances through time(seealsoReplacis,2011foradetaileddiscussion of theevolutionof theconceptof resilience).‘‘Inthis context, the resilience of an urban retail system is defined as theability of different typesof retailingto adapt to changes, crises or shocks that challenge the system’s equilibrium without failing to perform their functionsinasustainableway’’(Replacis,2011).Ina sense,resilienceisthenewformofsustainability,andis thus a current topic of discussion (see, for example

Stumpp,2013;Davoudi,2012andBarata-Salgueiraand

Erkip,2014onits meaningandapplicabilitytosocial sciencesandplanning).Shaw(2012)callsitaparadigm shiftwithnewchallenges,asthefocusseemstobeon individuals ratherthaninstitutions. However, depoliti-cizing the concept of resilience without asking questions about the reasons for disturbances or the nature of resilient systems should be approached cautiously(Porter&Davoudi,2012).

According toStumpp(2013, p.2) ‘‘resilience as a concept is more dynamic, it is non-linear and cross-linked,complexsotosay,anditembracesuncertainty.’’ These qualities make it incompatible with current planning methods and invite new and more creative

approaches.Therearetwomaincomponentsthatdefine theresilienceconcept:oneisinherenttothesystemin question, whereas the otherinvolves factors affecting the system. The latter is easytorecognize because it revealsitselfintheformoflargeshocksorcrises(such asnaturaldisasters,warsorbankruptcies),asslow-burn changes from the incremental impacts of global economic factorsor as small-scalecrises thatrequire quick adaptation. Thefirst componentis definedbya system’scapacityforresilienceanddetermineshow it reactstosuchimpactswithoutdisturbingits function-alityinanewbalance.Thiscapacitycanbedefinedby flexibility,adaptability,preparednessorcommunication between agents, amongothercomponents. As Collier etal.(2013,p.1)suggest,‘‘someof[the]socialbarriers include the capacity of a community toadapt andto influenceadaptiveprocesses,localplanningbodies,the degreeofcommunitycapitalandtherelativesizeofan areawithinthelargerentity.’’Thiscomponentisharder toanalyze duetoitsdynamicand complexcharacter, whichisspecifictothecontext.Howmuchthesefactors explain the changes inTurkish retailing isone of the mainquestions exploredinthispaper.

Simmie and Martin (2010) note Foster’s (2007)

distinctionsbetweenactors’spontaneousandprepared responsesintheadaptationprocess.Erkipetal.(2014, p. 113) define spontaneous resilience as ‘‘the typical reactivestrategythatindividualretailersundertake;itis essentially focusedon outlets’retail activity. Planned resilience, however, requires the involvement of associations, municipalities and other public actors andismorecomprehensive.’’Webelievethatinmost cases, spontaneous resilience better explains the Turkishsituation.

Muller(2011,p.5)pointsouttheinherentfeatures that make some cities more resilient than others, including ‘‘human perception, behaviour and interac-tion, as wellas decision-making,governance,andthe ability toanticipate and plan for the future.’’ ‘‘Cities withanefficientnetworkofcentresthatdelivergoods andservicestothevicinityshouldbemoresustainable than the ones without such a network’’ ( Barata-Salgueira & Erkip, 2014, p. 108). However, from a spatial point of view, linkages between retailing and urban development in different countries have not alwaysfollowedsimilartrajectories.Spatialresilience isclosely linkedwiththeidentityoftheurbansystem (Cummings,2011).Stumpp(2013,p.2)indicatesthat ‘‘inthecontextofresilience[adaptation]nowrefersto sudden disturbances, to recovery and renewal and it triestopreparefortheun-projectable, the impossible-to-imagine.’’ There are indications thatTurkish cities

havewelladaptedtothechangesthathaveoccurredin two decades of mall development, because street retailers and other agents survived these transforma-tions, using various innovative resilience strategies (Erkip et al., 2014; Ozuduru et al., 2014). Thus, we believe that the system has exhibited a high level of flexibility andadaptation.Despite the sector’slackof preparation,creativeresiliencestrategiesemerged,but the absence of a cohesive plan may well become a seriousprobleminthecaseof ashock.

3. Retaildevelopmentin Turkey:defining periods

Before starting our analysis, we provide a brief historical contextof Turkish retailing beginningfrom theOttoman period.

During Ottoman times, Istanbul was the main consumer market and the trade link between the OttomanEmpireandtheworldeconomy.Themarket, whichwascompletelycontrolledbythestate,realized itstransactionsinbazaars– themostfamous one,the GrandBazaar,isstillanattractionpointfortouristsand Istanbulcitizens.Othertypesofbazaarsincludedcarsis (markets), bedestens (covered bazaars) and hans (hostels for traders). Ethnic groups traditionally involved in commerce ‘‘became the most dynamic intermediaries between European capital and local markets’’ after a treaty opened the empire toforeign capitalin1838(Tokatli &Boyaci,1999). Westerniza-tionduring thenineteenthcenturyresulted inIstanbul becoming a dual city joined by the Galata Bridge (Toprak,1995).Toprak(1995)relatesthedevelopment ofconsumptionpatternswiththechangeinretailforms intheOttomanperiod,pointingouttheinfluenceofthe West. Louvre, Au Lion, Bon Marche, Au Camelia, BazarAllemand,CarlmannetBlumberg,OrosdiBack, AuPaonandBakerarelargestoresofEuropeanorigin, whichopenedfranchisesinIstanbulinthesecondhalf of the nineteenth century. This period is seen as a consequenceof liberaleconomic policies andinfact,

GeyikdagiandGeyikdagi(2009)claimthatthisisthe

‘‘first globalization’’ in Turkish history. They further pointouttheresemblancebetweenthefirstandsecond globalization: both were fuelled by consumption withoutsufficientlyattractingforeigndirectinvestment (FDI)andresultedinalargetradedeficit.

During the Republican period, small-scale conve-niencestores,butchers,grocersandindependentstores forotherconsumergoods,aswellasbazaarsandstreet vendors, were the dominant retail format until the 1970s.Franz,Appel,andHassler(2013),analyzingthe

changes in grocery retail and the spatial diffusion of supermarkets and hypermarkets in Turkey in four phases, document the country-specific motives of a moremodernretail format.Interestingly,in1953,the Turkish government, in cooperation with Istanbul’s municipality, invited the Swiss Migros to invest in a joint venture in Istanbul, particularly to benefit from theirknow-howinfoodretailing.Thisarrangementwas adifferent modeofforeign investmentbecauseitwas initiatedbythestateratherthanbythepullfactorsfor FDIs(Franzetal.,2013).Startingwith20mobilesales trucks, Migros opened its first self-service store in 1957. Despite financial and organizational problems thatthecompany experienced initsfirst fewyears, it ‘‘started to vertically integrate parts of the supply chain’’ and ‘‘became involved in food processing’’ (Ozcan2008,citedbyFranzetal.,2013).

Following Migros’ example, Turkish supermarket chainsGima(1956),OYAK(1963)andTansas (1973) wereestablishedandbeganbecomingpartoftheurban Turkey: all of these stores were public investments through local institutions. Although Turkey shares similarities with some Central and Eastern European countries in the development of food retailing, the Migroscaseisunique(Franzetal.,2013).The above-notedcountriesalsoexperiencedamuchfasterspatial diffusionof supermarkets,hypermarketsand discoun-tersafter1990thanTurkeydid(Franz etal., 2013).

Beforethe 1980s, Turkey’s retailingand manufac-turingsectorswerecharacterizedbyimport-substituting industrializationandapubliclyorprivatelyowned–but government-dependent– industrialsectorthatshowed little responsiveness to changes in international circumstances(Tokatli&Boyaci,1998).Thebusiness environmentwasprotectedanddirectedtothedomestic market, andFDIs were discouraged. In 1960, Turkey experienced an economic boom, followed by an economiccrisisinthelate1970sthatshowedtheneed foreconomicrestructuring.Inthe1960s,accumulation of agrarian and commercial capital was converted to industrialcapital; importers becameindustrialists and the people investing in import-substituting industries werethesamepeoplewhohadimportedanddistributed thosegoodsinthepreviousera;thustherewasafuzzy boundarybetweenmanufacturersandtraders(Tokatli&

Boyaci-Eldener, 2002). Traditionally, retailers were

smallandindependentandthey selected locations by intuitivejudgement, experience,familiarity and coin-cidence.They hadlimited businessskillsand limited capital,andcash-runretailbusinessesappearedtobea convenient investment area (Ozcan, 2000). However, smallbusinesseshad fewopportunities tocompete in

local markets, accumulate capital or co-operate with eachother(Ozcan,2000).

Beginning in1980, by recognizing andcoming to terms with global competition conditions, Turkey adoptedamoreoutward-orienteddevelopmentstrategy tocultivateits exportpotential.From 1981to1993,a particularly high rate of economic growth occurred (Tokatli &Boyaci, 1998). The late 1980s’shift from manufacturing to consumption (Tokatli & Boyaci, 2001; Tokatli & Erkip, 1998), as well as decreasing government control, increasing privatization and increasingflexibilityinregulatingforeigninvestments, begantochangetheorganizationalstructureoftheretail sector.Inaddition,‘‘thefinancialsector,andespecially mediumtosmall-scalebanks,areattractedtocash-rich retail business in a high-inflation, high-interest rate macro-economicenvironment’’(Ozcan,2000;p.107), especially between1990and2000.

Themaincharacteristicsoftheperiodsinwhichwe analyzeTurkey’sretailsectoranditsdevelopmentcan

be seen in Table 1. We focus on the two decades

between 1990 and 2010 as the point marking the integrationof Turkishretailinginto globalcapitaland changing the sector’s local and traditional character. This change is observed mainly by shopping mall development in Turkey’s urban scene, beginning in metropolises and expanding to the whole country in fewerthan20years.

3.1. The firstperiod:globalimpactsonthe organizationoftheretail sector,1990–2000

Despitetheabove-mentionedchangesintheTurkish economic structure, globalization of the retail sector started quite slowly– over a ten-year period. It took anotherdecadefordomesticandinternationalretailers to become extensively involved in retailing, mainly because of the country’s fragmented retail structure, which makes performing in a large-scale retail environment difficult (Tokatli & Boyaci, 1998). Beginning in the 1990s, domestic and transnational corporations (TNCs), the latter usually jointventures withdomesticpartners,begantochange thenature of the sector,withlargeandorganizedretailinvestments creatingarichconsumermarket(seeTokatliandBoyaci foralistandtheretailactivitiesofthesecorporations). The first period of large-scale organized retail in Turkeybeganwithafewshoppingcentresthatopened in the late 1980s and became citylandmarks. At the beginningofthe1990s,investmentsweredominantlyin large-scale food retailers as the anchors of new shoppingcentres.Initially,suchspacesweredeveloped

byanumberofEuropeancompaniesinpartnershipwith major Turkish companies. Turkey became an invest-mentfocusforthe followingreasons:(1)apopulation greater than that of most European countries, (2) a significantshareofayoungerpopulation,whocouldbe easilydivertedtowardsconsumptionand(3)thequick rate of returns on investment compared to many European countries at the time. Groupe Carrefour of FrancecollaboratedwithSabanciHoldingin1996and openedCarrefourSahypermarkets,ChampionSa super-markets,andDiaSadiscountmarkets.Germany’sMetro Group opened MetroGrossmarket, RealHypermarket, and Praktiker home improvement and do-it-yourself stores. Towardsthe end of the 1990s, anew wave of shopping centres opened, again initiated by interna-tional investments, including Dutch(Corio and ECE) and German (MultiMall) investment companies (Ozuduru &Varol, 2011).

Because of these developments, Turkish society couldnowaccessalargenumberofgoodsandservices in one structure, and ‘going to the mall’ became an increasinglypopularurbanactivity.TheTurkishmarket wasinclinedtoconsumption,andthusbothdemandand supplyexpectationsweremet.

Rapid urbanization, increase in per capita income and levelof education, increasinguse of telecommu-nicationtools,youngdemographics,increasedmobility

by car or public transportation, more contact with foreigncultures,newaspirationsandlifestylechanges paved the way to modern retailing, particularly in IstanbulandAnkara,Turkey’slargestcities.Domestic andforeignbrandssoldinshoppingmallsandonhigh streetsbecameattractivetoanurbanized,better-offand youngerpopulationwithadesiretobeapartofglobal consumptiontrends.Afterafewdecadesof moderniza-tionefforts,thedemandformodernconsumptionspaces seemedanappropriateresponse.Middle-incomegroups were not excluded from this new consumption experience; for various reasons, they constitute the crowdinmostshoppingmalls.‘‘Thegrowingeconomy, favourable consumer demographics, and a relatively fragmentedretail landscapemakeTurkeyattractiveto internationalretailers.Disposableincomehasincreased at a compound annual growth rate (CAGR) of 3.6 percent since 2005, while the percentage of households earning less than $15,000 dropped from 53percentto45percent.Themiddleclass’sexpanding purchasing power is spurring sales growth, while wealthylocalsandinternationaltouristsareincreasing luxurygoodssales’’(Kearney,2013).Itisimportantto note that the increase in income accompanied by culturalchanges provided awell-established basisfor the development of new retail formats, including shoppingmalls.

Table1

DefiningperiodsofretailtransformationinTurkey.

Before1990 1990–2000(firstperiod) 2000–2010(second

period)

2010+(thirdperiod)

Traditionalretailforms Firstgenerationofshopping

malldevelopments

Influxofshopping centredevelopment

Accumulatedimpactof globaleconomiccrises Small-scaleandlocal

investments

Penetrationoflargecapital andforeigninvestmentand partnership

Partnershipofforeign capitalwithnational capital

Increasingpolitical tensionintheregion/ country

Aspirationsforglobal integration(1980s)

Legislationinlinewith economicdevelopment

Increasinginvestments ofnationalandlocal capital

Decayingshoppingmall investments

Transitionfromimport-substitution toexport-orientedand

outward-lookingeconomy (1980s)

-TaxLaw(1992) Increasingboomin

constructionsector

Hesitantforeigncapital

PromiseofEUmembership (1980s)

-LawofCapitalMarket(1994) Furtherlegislation Newshoppingalternatives

-TurkishCompetitionAuthority (1997)

-OwnershipRights forForeigners(2003)

Citiespronetonatural disasters

-Establishmentofrealestate investmenttrusts(REITs)(1998)

-Attemptstocontrol retaildevelopmentby law(2004and2006)

Contestedurbanspace

OptimismaboutEUmembership Economiccrisis(2008) LesseningEUinfluence

OptimismaboutEU membership

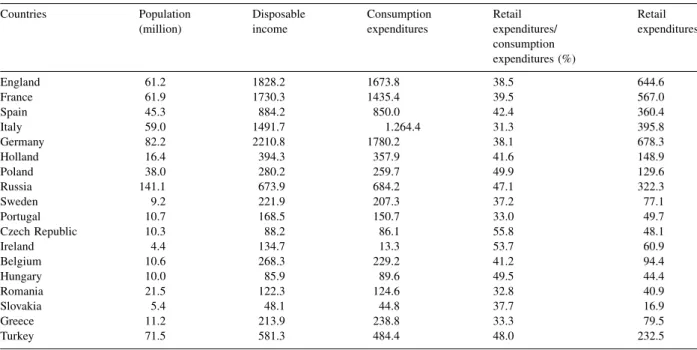

Forthereasonsstatedabove,theTurkishretailmarket stillhasalargerpotentialforinvestmentthanmanyother European countries, given the high ratio of retail expenditures to consumption expenditures (AMPD, 2010;Deloitte & Planet Retail, 2010). Table2 shows theappealoftheTurkishmarkettoforeigninvestors.

Table 3 shows that the share of FDI inflows in

wholesaleandretailtrade,amongothersectors,peaked in 2008. Overall, after 2005, that share decreased significantly. The decrease after 2010 shows that the retailmarket hasbeguntobe dominated bydomestic capital,whichalso supportsthe argumentthatforeign investment in retailing has shifted to other countries (Ozuduru&Varol,2011).

Asinothercountries,large-scaleretailershavehada significant impact on traditional and independent retailers in Turkey, who are morevulnerable because theycannotpredicteconomicchangeasfastasorganized retailers can (who, in fact, often create that change). Large-scaleinternationalretailershavebargainingpower with manufacturers andcan offerthe same quality of goodsandservicesmorecheaplythanlocalretailers.In mostcases,themiddlemaniseliminatedfromtheprocess (Tokatli & Boyaci-Eldener, 2002). When the retail transformationinTurkeybegan,smallretailersdidnot havesufficient fundsor knowledgetodevelop proven copingstrategies.Someorganizedretailersattemptedto help (granted, with their own interests in mind) by

providing small-scale retailers with an organization modelsimilartofranchising.Inreturn,theyaskedfora share of the profits. For example,Swiss-based retailer MigrospartneredwithaTurkishcompany(KocHolding) tochangethebusinessmodelsofindependentretailersby offeringservicestrategiesandknow-how.Thoseretailers have become small-scaleoutlets where customerscan findthesameconveniencegoodsandservicesofferedin hyper/supermarkets. These stores resemble traditional conveniencestores,calledbakkalinTurkish,andeven haveasimilarname(Bakkalim,meaning‘mybakkal’), but are more modern, hygienic and organized. The strengths of these independent retailers are their proximitytocustomersandcustomers’familiaritywith them. People can buy their daily goods from these retailers and their weekly goods from the hyper/ supermarkets.

The central government, on the otherhand, devel-opednewtoolstosupportlarge-scaleinvestorsbecause they could easily collect taxes from them; traditional independentretailersareinfamousfortheirtaxevasion. Legislation such as the Tax Law(1992), the Law of CapitalMarkets(1994)andtheestablishmentofREITs (1998)supportlargecapital,whichprovideseconomic advantages to itsshareholders. The Turkish Competi-tion Authoritywasestablishedin1997toregulate the sectorbyexertingcontrolovercompetitioninit. Small-scale retailers were not effectivelyprotected bythese

Table2

EconomicindicatorsandretailexpendituresforTurkeyandsomeEuropeancountries(2008)(milliondollar).

Countries Population (million) Disposable income Consumption expenditures Retail expenditures/ consumption expenditures(%) Retail expenditures England 61.2 1828.2 1673.8 38.5 644.6 France 61.9 1730.3 1435.4 39.5 567.0 Spain 45.3 884.2 850.0 42.4 360.4 Italy 59.0 1491.7 1.264.4 31.3 395.8 Germany 82.2 2210.8 1780.2 38.1 678.3 Holland 16.4 394.3 357.9 41.6 148.9 Poland 38.0 280.2 259.7 49.9 129.6 Russia 141.1 673.9 684.2 47.1 322.3 Sweden 9.2 221.9 207.3 37.2 77.1 Portugal 10.7 168.5 150.7 33.0 49.7 CzechRepublic 10.3 88.2 86.1 55.8 48.1 Ireland 4.4 134.7 13.3 53.7 60.9 Belgium 10.6 268.3 229.2 41.2 94.4 Hungary 10.0 85.9 89.6 49.5 44.4 Romania 21.5 122.3 124.6 32.8 40.9 Slovakia 5.4 48.1 44.8 37.7 16.9 Greece 11.2 213.9 238.8 33.3 79.5 Turkey 71.5 581.3 484.4 48.0 232.5 Source:GYODER(2008,p.51).

changes, however, because the central government focusedonlargeforeigncapital.

Towards the end of the first period, large Turkish retailcompanies startedtoinvest inothercountriesin theregion,suchasRussia,AzerbaijanandKazakhstan (Ozcan, 2000).Theyfilledthe role ofWestern TNCs, whichdidnotfindthesecountriessufficientlyattractive toinvestin.OnesuchcaseisAlbania,acountrygearing upformodernretailformats(KursunluogluYarimoglu, 2014). ‘‘More than Turkey’s 50 largest companies operate currently in Albania’’ (Kursunluoglu Yarimo-glu, 2014, pp.121–122). Turkish textile products are predominantlyexportedtoAlbania.

3.2. The secondperiod:the influxofshopping centres,2000–2010

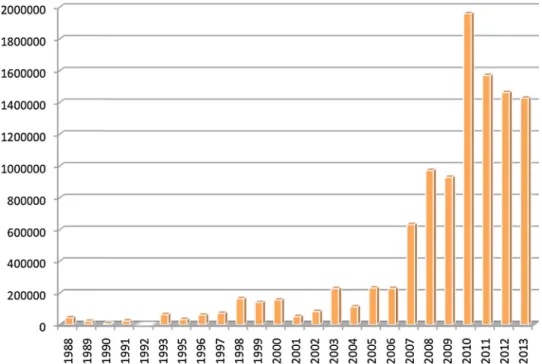

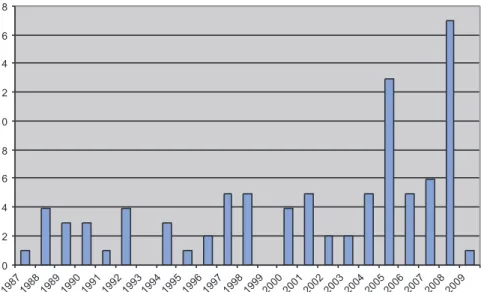

The second period observed ahighgrowth rate of shopping centresin Turkey.Grossleasable area – the primary indicator of shopping centre size – and the numberofshoppingmallsincreasedsteadily(seeFigs. 1 and 2). Shares of foreign investments in shopping malls also increased, with more penetration of large, dominantlyEuropean,capital(seeFig.3).Thisdecade was the most favourable period for shopping centre development in Turkey. Regardless of the global economiccrisesthatsignificantlyaffectedinternational investments globally, between 2008 and 2010, the number of shopping centres increased significantly, revealing thatthe shopping centre investorshadtheir ownequitycapitalthroughinvestmentinothersectors.

As of 2013, the number of shopping centres in Turkey was 368, with a total gross leasable area of 10,679,370m2. In 2006, the number of employees in Turkey’sorganizedretailsectorwas300,000,growing to585,000in2011,anincreaseofapproximately95%. AsobservedfromFigs.1and2,thenumberofcentres increasedmostrapidlyafter2004,two yearsafterthe Justice and Development Party (Adalet ve Kalkınma Partisi or AKP), whose development policy supports consumptionandinvestmentinshoppingcentres,came topower.Franzetal.(2013,p.57)notethat‘‘underthe new leadership, liberalization was takenforward and investors became more confident due to the growing political stability in the country. These political developments, together with the growing purchasing powerofconsumersinTurkey,hadimpactsontheretail sector:TNCsintensifiedtheirinvestments.’’

After2003,theshareoflocalinvestorsalsoincreased significantly;shoppingcentreinvestmentand manage-ment has become a lucrative business for many. The provision of ownership rights for foreigners in 2003acceleratedglobalinvestmentinprofitablesectors in Turkey, especially in shopping malls and office complexes. Although the interest of international investors is persistent (Fig. 3 shows that the number ofinternationalinvestorsconductingbusinessinTurkey was increasing until2010), the share of nationaland localinvestorsinshoppingcentredevelopmenthasalso increased, and now exceeds international investors. Observingthe quickandhighratesof return,national companies insectorssuch as tourism,manufacturing, marinetrade andconstructionalso beganinvesting in Table3

Foreigndirectinvestment(FDI)inflowstoTurkeybyeconomicsectors.

Economicsectors 2005 2006 2007 2008 2009 2010 2011 2012

Agriculture,forestryandfishing 0.1 0.0 0.0 0.3 0.8 1.3 0.2 0.4

Industry 9.7 11.9 26.7 35.0 60.9 46.2 49.6 54.6

Mining 0.5 0.7 1.8 1.0 3.3 2.2 0.9 2.1

Manufacturing 9.2 10.6 22.0 26.7 24.5 14.8 22.3 43.4

Electricitygas,water 0.0 0.6 3.0 7.2 33.2 29.2 26.4 9.1

Services 90.2 88.1 73.2 64.8 38.3 52.5 50.2 45.0

Finance 47.1 39.4 60.9 41.2 10.4 26.0 36.6 14.2

Construction 0.9 1.3 1.5 2.2 3.7 5.0 1.9 14.3

Wholesaleandretailtrade 0.8 6.6 0.9 14.1 6.1 7.0 4.4 2.2

Otherservices 41.4 40.8 9.9 7.2 18.1 14.5 7.3 14.3

Total 100.0 100.0 100.0 100.0 100.0 100.0 100.0 100.0

Source:YASED(2013).

Bold valuesindicatethemajoreconomicsectors(i.e.Theindustrysectoriscomposedofmining,manufacturingandelectricity,gas,water subsectors;servicessectoriscomposedoffinance,construction,wholesaleandretailtradeandotherservicessubsectors.Agriculture,forestryand fishingsectordoesnothaveanysubsectors).ItalicandunderlinedvaluespointoutthesignificanceofthefluctuationsintheshareofFDIflowsinthat particularsubsector(i.e.After2005,theshareofwholesaleandretailtradedecreasedsignificantly;anditpeakedin2008,andthedomesticcapital shiftedtoothercountriesafter2010).

the retail sector. This increase in the share of local investorsmakesthesectormoreresilienttocrisesinthe global economy. Further, that the equity capital of nationalretailinvestorsisfinanciallysupportedbyother

sectors causes retail investors to continue to pursue shoppingcentreconstructionprojects.

In2008,ontheeveoftheeconomiccrisis,thesecond influxofshoppingcentreopeningsinTurkeyoccurred Fig.1.NumberofshoppingcentresinTurkeybyyear.

Source:Authors’search.

Fig.2.Totalgrossleasablearea(m2)ofshoppingcentresinTurkeybyyear. Source:Authors’search.

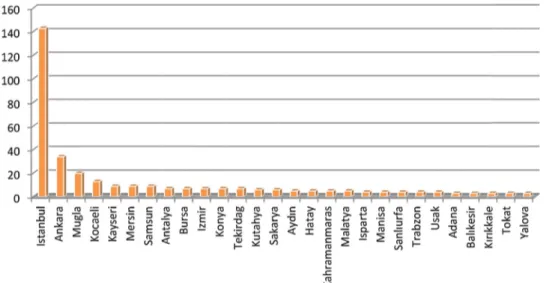

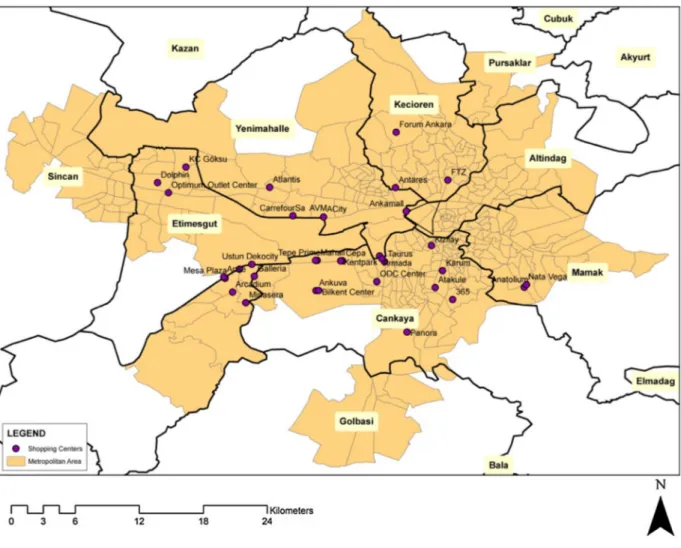

(Ozuduru & Varol, 2011). Although the number of shoppingcentresinIstanbulgreatlyexceedsthoseinall otherTurkishcities,itshouldbenotedthatthereisalso ahighrateofgrowthinshoppingcentreinvestmentsin manyothercitiescomparedtotheirpopulation,making thesespacesan importantcomponentof urbanlifeall over Turkey(Fig.4).

Inthesecondperiod,thepowerofretailcompanies over government institutions also increased. These companieshavebecomesignificantbusinessesandhave been able to negotiate development rights with governmentagencies.Inmanycases,localandcentral government institutions offered flexibility in land

developmentoncetheconstructionofashoppingcentre hadbeenagreedupon.Investorsanddevelopersstarted shaping retail legislation and planning strategies. Government agencies, chambers of commerce and otherrelatedretailorganizationsdiscussedlaterinthis articlehavedeclaredthattheyprefertheretailsectorto beorganizedbytheselarge-scaleretailersbecausethey provideconsistentsourcesoftaxrevenue,providebetter employment opportunities, increase the sector’s pro-ductivity level, offer cheaper, reliable high-quality goods and services to consumers, have increased the paceandamountofFDIandopeneduptheeconomyto global markets(Ozuduru&Varol,2011).

Fig.3. Numberofshoppingcentresbyinvestortype. Source:Authors’search.

Fig.4. NumberofshoppingcentersinTurkishcities. Source:Authors’search.

The resilience process also dominated the second period.Traditionalretailers,whowerecaughtunaware bythechangesinthefirstperiod,developednewskills andstrategiestoadapttomarketchanges.Theyincreased their level of service to generate loyalty among customers, such as ensuring high-quality products, reasonable prices or 24-h service. They clustered to offer comparison shopping for certain goods and services.Forexample,jewellersclusteredinonelocation in a city and retailers selling technological products clusteredinanotherlocation.Weanalyzetheresilience strategies of the traditional and the more organized segmentsofthesectorinthefollowingsections.

In 2004, Turkey’s Ministry of Industry and Commerce initiated a major regulatory effort: ‘‘The aimoftheproposedlawisthree-fold:(a)consideration of consumer rights, (b) the provision of modern urbanization in cities and (c) balancing competition betweenvarioussegmentsof the retailsector’’(Erkip etal.,2013,p.336).However,thislawhasnotyetbeen passed,apparently because it requires locating stores andshoppingmallswithsaleareaslargerthan5000m2 tobeyondthecitycentre.In fact,the lawcitestraffic congestion,insufficient parkingfacilities,unfair com-petitionbetweenlargesuppliersandexclusionof small-scaleretailersfromtheretailmarketasconsequencesof shopping malldevelopment. Although different retail segmentsappeartosupportthelaw,thepowerstructure isstill infavour of large capital, andthis established supportbycentraland localgovernments discourages the progress of the legislative process. This situation also prevents realizing aspects of the lawthat would ensure more holistic retail planning, such as demand analysis, traffic planning, infrastructure development, environmental analysis and sustainability measures. Thelawhasbeen re-draftedseveraltimesbuthasnot passeddue to its monitoringcomponents, which will hurt large-scale retail businesses (The Ministry of CustomsandTrade)(www.gtb.gov.tr).

Critics of the proposed law cite an outdated framework that suggestsno solutions to mitigate the impact of large-scale retailers on traditional retailers, providesnodefinitionsorstandardsforsizeorlocation choice, and neither sets up rules for site-selection feasibility analyses or relationships to development plans nor sets out the roles of public and private organizations in the development process. Retail legislationshouldcontributetothebroaderframework of resilience, which can be arranged by developing strategiestoaddresstheabovecriticisms.Collaborative actionbetweenlocalgovernmentsandotherinterested partiesshouldbetheprimaryaspectsof thisprocess.

The other important project of this period is documented in the 2009 report of Turkey’s Council of Urbanization of the Ministry of Public Worksand Settlement (now the Ministry of Environment and Urbanization)(www.eukn.org).Thisproject,calledthe Integrative Urban Development Strategy and Action PlanforSustainableUrbanDevelopment(KENTGES) aimedtoincreasetheleveloflivabilityinurbanareas and took a holistic approach to all aspects of urban development in Turkey, in accordance with the last (ninth) national development plan, effective between 2007and2013.TheKENTGESinitiativewasproposed as a guide for urbanization, settlement and planning with the collaboration of public institutions, local governments,private investments,NGOs andcitizens. Inotherwords,itattemptedtocoverallpartiesaffected bythe urbandevelopmentprocess.

In the first phase of the project, an Urban Development Consortium was organized; more than 150institutionswithmorethan500expertscontributed tothestrategydocument.Inthesecondphase,anaction planwasdeveloped,coveringproposalsfor transporta-tion, infrastructure, housing, disaster preparedness, protection of natural and cultural heritage, climate change, energy efficiency, renewable resources, ecol-ogy, migrationandsocialpolicies,economic structure and participation. Although retail planning was not listed as aseparate topic,with itslinks tothe above-mentioned issues it was discussed as part of urban sustainability.Urban transportation isoneofthe most importantissuesrelatedtoretaildevelopment.Despite (or perhaps because of) decentralization tendencies, housing andworkplaces in urban corescause serious trafficproblemsinmanyTurkishcities.

Urbantransformationbeganinthe1980sinTurkey to improve the conditions of low-quality settlements, butitsaimchangedinthe1990s.Centralareasofcities withhistoricalandculturalsitesandworkplaceswere boughtupfordevelopment,suchasshoppingmallsand entertainment sites. The KENTGES report criticized suchurbantransformationandcalledforgovernmentto focusonsocial,culturalandhistoricaldevelopmentand sustainability.

AnotherimportantcomponentofKENTGESwasthe ‘sustainable urban form,’ which defined alternative forms of urban development in line with the EU perspective. According to this approach, excessive decentralization and sprawl are not as sustainable as compact, corridor or multi-centred development. The reportmadeheavyuseofinternationaldocumentsand the EU’sapproachestourbanization.Themes,targets, strategies and actions were defined accordingly and

‘urbanmacroform’and‘urbancentre’wereselectedas KENTGES’ main premises. Strategies on developing shopping siteswere considereddirectly relatedto the futureofurbancentres,andtheneedforlegislationon the scale, location and structure of new shopping developments was stressed. The impact of such developments on existing shops and workplaces was alsonoted.

The then-Ministry of PublicWorks andSettlement was tospearhead theproject,withlocalgovernments, universitiesandchambersofcommerceasparticipating constituents. The period between2010 and2012 was devoted to the short-term arrangements (such as limiting working days and hours, establishing tools for price control and promotions) for drafting the legislationonshoppingcentredevelopments,but now the projecthasbeen ‘postponed.’

3.3. The thirdperiod:a laissez-faireapproachby the centralgovernment,andmarketdominancein 2010and beyond

Turkey’sretailmarketisoneofthemostprosperous anddynamicintheEuropearea(Cushman&Wakefield, 2012),althoughthetotalnumberofshoppingcentresis still lower than in many European countries. The average gross leasable area per 1000 people is about 220m2inEuropeand100m2inTurkey.Thispotential forgrowthmakes Turkeythecountrywiththe highest pipelineof shoppingcentre areasafter Russia(

Cush-man & Wakefield, 2013, May). Between the end of

2010andthethirdquarterof2013inTurkey,thetotal number of malls increased by 47.6%. Turkey’s two largestcities(IstanbulandAnkara)hold50.5%,orjust over half,ofthe country’sshoppingcentres. Thetotal grossleasableareaofshoppingcentresinTurkeytoday is 10,700,730m2, with almost half (44.5%) of this property in Istanbul. Kocaeli has the fourth-highest numberofmallsinthecountrybecauseofitsproximity to Istanbul. Mugla, with its proximity to towns that attract many tourists, ranks third in shopping centre investments(see Fig.4).

High streets are also attractive locations for retail stores, especially for luxury brands such as Chanel, which rents space in Istanbul on Bagdat Street, and Armani, which has a space on Nisantasi Street, both upscaleshoppingareas.‘‘However,itisgenerallyvery difficulttofindspace inexisting streetsandshopping centres. New leases and relocations happen very quickly, which is something of an obstacle for international retailers’’(Cushman&Wakefield, 2013/ 2014). Luxury brands also desire spaces in new

shoppingcentres:LouisVuitton, ChristianDior,Fendi and Bulgari are tenants of Istanbul’s newly opened ZorluCentre.According toKearney(2013),Turkeyis growingas ‘‘afashioncapital withaslew of talented local designers.’’ In addition to favourable consumer demographics,thecountry‘‘isalsoinanidealposition as a production andlogistics hub, witha 3.6percent shareinglobal textileandready-wear exports.’’

This third period also observed a nationwide construction boom, with the retail sector the primary economicmotive.Atfourpercent,Turkeyhasoneofthe highest rent-growth rates in shopping centres in the Euro-area (Germany also stands at four percent and Poland’srateissevenpercent)(Cushman&Wakefield, 2012). However, ‘‘the completionrate slowed during thesecondhalfof2012;indeed,only123,000m2GLA (grossleasablearea)wasbroughttothemarket,through theopeningoftwonewschemesinIstanbul,compared withthe250,000m2completedinthefirsthalfof201200

(Cushman & Wakefield, 2013, May). Uncoordinated

site-selectionofshoppingmallshascreatedcompetition betweenoldandnewmalls,andsomeolderoneshave closed.AlthoughIstanbulhasthemostshoppingcentres inthecountryitalsohasthehighestmall-closurerate. About10% oftheshoppingcentres openedinthe last two decades are now closed, and some fear that this negative trend might increase. Vacant spaces in shopping malls from tenants who have not renewed theirleases constitute anotherplanningproblem. It is not surprising that the tenant selection process has startedtobecomemoreopen-minded,astheownersof some specialty clothing firms attest. For example, TesetturGiyim,aclothingchoiceforreligiouswomen, claimsthatshoppingmallsbecamemorewillingtosell their products after economic crises (Zaman Pazar, 2009).

Online shopping is another important dynamic affectingTurkey’sretail sector.Although stillasmall part of total retail sales, this mode of shopping has averageda32.8%annualgrowthrateinTurkeyoverthe last five years (Cushman & Wakefield, 2013, July). Apparently,thereisimportantpotentialine-commerce.

A.T. Kearney (2012) calls the Turkish case a ‘‘quiet

success’’andbelievesthatthereisa‘‘stronglogistical infrastructure’’ for online purchases,noting that‘‘the Turkish government has also aided the e-commerce boom by enacting digital laws that protect online consumersandoversee e-commerce companies.’’The currentcapacityofthemarketis$1.3billion,whichis appealingfor foreignretailers.‘‘In 2011,Naspers,the SouthAfricanmediaconglomerate,acquired70percent of Markafoni, one of Turkey’s largest private online

shopping sites’’ (A.T. Kearney, 2012). It is also predicted that potential online shoppers’ fears of transactions over the internet will be alleviated by companiessuchashepsiburada.comthatprovidesecure paymentmethods.

Macroeconomicdataindicatethattherearesignsofa downwardslopeintheeconomy(Gurkaynak&

Sayek-Boke, 2013) and that the current positive indicators

might not be long-lasting. The AKP’s construction crazecanbetracedinthecountry’surbandevelopment andhasbeencriticizedbyanti-governmentgroups.The 2013protestssparkedbytheGeziParkincident,where thegovernmentwantstoreplacegreenspaceinIstanbul withamall, indicatethat thisunderstandingof urban developmentis notwell acceptedbyall citizens.The demonstrations against Gezi Park’s destruction expandedintoprotestsaboutcitizens’otherfrustrations withthegovernment,suchaseconomicinequalities.A similardemonstrationtookplacerecentlyinasmaller cityofTurkey,Amasya,whereaparkwastobereplaced by a petrol station, and another protest occurred in Istanbul,against itsproposedthirdairport,whichisto bebuiltbydestroyingaforest(BBCNews,2014).There is also evidence that the Gezi Park unrest caused a declineinconsumptionexpenditures,particularlyinthe fewmonths following the protests(EIU,2013). Even though the situation now seems to be stable, further conflicts may occur, and this reflection of citizens’ opinionsshouldbeacknowledged ratherthanstifled. 4. Actors andresiliencestrategies

Lackofeffectiverepresentationofnonprofitretailing andcitizenorganizationsintheurbanplanningprocess may be another source of conflict in future develop-ments. In earlier studies, we discussed the roles of governmental and nongovernmental organizations (NGOs)inshapingthe retailsector,inadditiontothe roles of large and smallretailers (Erkip et al., 2013; Varol&Ozuduru,2010).Ministriesandlocal govern-ments dominate the process of legislation and its implicationsforthesectorundertheinfluenceof large-scale retailers, but professional organizationssuch as theConfederationofTurkishTradesmenandCraftsmen (TESK) and other local NGOs (formed by street retailersandinhabitants)doplayalimitedroleinthis planningenvironment.

Internationalcompanieshaveastructured organiza-tion and their investments rely on various analyses, feasibility studies and scientific knowledge. National andlocal companies, onthe otherhand, usually only belongtoaninformalnetwork andfollowthe leadof

international investors. Turkey’s local and national retail sectordevelopers became moresophisticated in thesecondperiodbecauseoftheincreasingcompetition between shopping centres. Initially, only developers wereinvolvedinmallconstructionatthenationaland locallevels.Astheneedtoimprovetheinstitutionaland organizationalstructureemerged,othersectorsbecame involved. Forexample, inthe 1990s, it was not until afterashoppingcentrewasbuiltthatitsmanagement searched for tenants. By the late 2000s, specialized leasingfirms, suchas JonesLang LaSalle,AVM MFI PartnersandMultiTurkMall,weresearchingfortenants and developing a marketing strategy for shopping centres before their construction. Sometimes these leasing firms also help determine new themes and branding.Today,investors,developersandleasingfirms dominate the sector, which, despite government involvement and legislative attempts, is essentially unregulatedanduncontrolled.Further,theretailmarket is increasingly influenced by national and local investors.Fortheabovereasons,internationalinvestors and developers have become hesitant about doing business in Turkey. Although some companies may considerthisenvironmentanopportunity,othersfindit too risky, especially when the economic situation becomeslessfavourable(foradetailedaccountof the developer’sperspectiveontheTurkishretailstructure, seeErkipetal.,2013).However,recentfiguresindicate thatTurkeyisstillagrowingandattractivemarketthat ismovingupinthe GlobalRetailDevelopmentIndex (GRDI), ‘‘nearing its peak growth state’’ (Kearney, 2013). There are also signs of factors pushing some companies, such as German Praktiker (facing opera-tionalandcompetitivechallenges,accordingtoKearney

(2013) and British Tesco (who has established an

agglomerate with Turkish Kipa) to exit the Turkish market(PlanetRetail,2013)).Transnationalshavethe flexibility, hence the resilience, to leave the market when it is no longer profitable. It is too early to determinewhatkindofdecisionwillbemade,but large-scaleinvestorsshouldbeclosely observedinterms of resiliencestrategies.

Severalnon-profit retailorganizations and associa-tionswereestablishedinTurkeyintheearly2000s,with the aim of improving the sector by providing opportunities for advancement, education and a net-work for exchanging knowledge, ideas and projects. Two major such organizations are the Association of ShoppingCentersandRetailersandtheAssociationof Shopping Center Investors. These groups aim to contribute to the advancement of organized retailers and increase their share in the retail sector, increase

productivitylevelsandeducation,lobbyforprotective legislation, compute and declare the relevant sector indices and indicators and disseminate scientific researchinthesectortoteachretailershowtodecrease their vulnerability to changes in the economy. Other leadingorganizationsincludetheAssociationofRetail Brands andtheAssociationofRealEstateInvestment Trusts. The abovegroupsdemonstrate how organized retailers can cooperate and develop a platform to exchange ideas and knowledge. For example, it is through these organizations and associations that shopping centre developmentmerged with otherland uses(residential,entertainment,office,etc.);thegroups identified thatsuch developmentsare moreprofitable andlastlongerthanstand-aloneshoppingcentres.

Theresilienceprocessdominatedthesecondperiod, when global impacts began to be observed in the economy and retail sector actors needed to adapt to those changes. The main actors in the Turkish retail sector are traditional small-scale and independent retailers, as well as organized large retailers usually associated with international capital. The groups’ resiliencestrategies aredifferent:the former adoptsa reactive strategybecauseit cannotpredict changes as quickly as the latter. Further, the former has neither sufficientfinancialresourcestodevelopbetterstrategies normuchinfluenceover governmentagenciesdealing with retailing. Through various projects and pro-grammes, Confederation of Turkish Tradesmen and Craftsmen purports to help provide solutions to the problemsofsmall-scaleretailers,yetitseffortsremain ineffectiveduetosomeoftherepresentatives’political aspirations(Ercoskun&Ozuduru,2011).

Streetretailers havenotbeenabletogeneratesuch strong alliances. Althoughthey havedeveloped some informalsocialnetworks,the expertisewithin andthe clout of these groups is not comparable to those of organized retailers. Many independent retailers were eagertobecomepartoforganizedchainstoattainmore power. The main impact of the above-noted EU requirements was on street vendors, open markets and bazaars, where the food products did not meet hygiene standards. Some positive changes in the conditionsof such retailers were realizedthrough the municipalities, such as in the case of simit (a round Turkishbread)vendors,whowereprovidedwith semi-closed mobile units to replace their open tables (see Fig. 5).Now, largecapital has becomeinvolvedwith simit, offering it in many franchised cafes in Turkey, some European cities and even in the United States (Fig.6).SimitisbecomingpartoftheTurkishimagein theglobalmarket.

Resilience strategies are applied according to the capacity and power of actors in a sector, and while organizedretailers have manyadvantages over small-scale,traditionalones,theymakelittleuseofinformal methods of connection, which always involve a personal component. For example, small businesses Fig.5. Asimitvendor.

Source:http://applsgr32.deviantart.com/art/Simitci-amca-171132180

(accessed15.01.14).

Fig.6. AFranchisedSimitSarayiCafe´.

Source: http://www.sektorankara.com/firm_detail.php?id=108

usually take phone orders, cultivate neighbourly relations anduphold traditional values and habits. In Turkey,theyhavealsoincreasedthequalityandvariety of their products, partly assisted by the emerging professionalnetworks.

Shoppingcentrescompeteamongthemselves espe-cially when they are located in the urban core. In addition to their general advantages, such as climate control and parking facilities, malls create niches throughcustomer segmentation, attracthigher-quality (mainly global) products and use their leverage in negotiatingwithlocalandcentralgovernments,mostly regarding mall location; zoning and planning regula-tions are often changed to provide a site for a new shoppingcentre.InthefollowingsectiononAnkara,we analyzethisaspect indetail.

Althoughstreetretailingisexpectedtobenegatively influenced by shopping mall development, Turkish retailers seem tobe coping withthe current situation throughinnovative strategies. Location helps – many streetretailersaresitedinpedestrianareas–yettheydo have concerns and complaints about shopping mall development andlocal governments’ attitude towards theretailsituation.Thesefactorsarealsoexemplifiedin theAnkaracase.

5. ThecaseofAnkara:empiricalevidences Withthe establishment of the Turkish Republic in 1923,Ankarabecamethecapital.Asareflectionofthe modernization period, development plans were pre-paredforthecitytocontrol itsgrowthandexpansion. Untilthedecentralizationpoliciesofthe1970sandthe corridor developments of the 1990s, Ankara was a compactcity.Overthelastfewdecades,ithasgrownto the west and southwest, with large subdivisions and residentialareasthathaveattractedmiddle-and higher-income households. Wealthy households are increas-inglychoosing to relocatefrom inner-city neighbour-hoods to the southwest. This housing pattern has affected Ankara’s transportation network as well as people’s trip-mode choice. Although it is a common viewthatshoppingcentresincreaseprivatecaruse,in Ankara, they equally increase the use of public transportation modes. Many government institutions, which are Ankara’s largest employers, are also relocating to the southwest, and the city has become increasingly car-dependent (Ankara Greater Munici-pality,2007; Babalik-Suttcliffe, 2013); the numberof cars per 1000 people has been increasing and as of 2009wasat191,thehighestinTurkey(TUIK,2009).

Ankara’s social, economic and demographic char-acteristics are alsounique inTurkey. The numbersof students and publicofficials are higher than in other cities, and middle-income citizens dominate the population. Squatter settlements in the northern and eastern parts of the city have been transformed into high-riseapartments,mainlyformiddle-income house-holds.

We selected Ankara as a case study for several reasons. First, as the capital city, it has the second-largest population in Turkey, with more than four million people. Second, Ankara ranked second in a nationalstudy(DPT,2003)regardingtheshareofwage earners,levelsofliteracy,universitygraduatesandgross domestic product, which are significant indicators of urban development. These features are among the reasons investors have frequently chosen Ankara for theirdevelopments(Ozuduru&Varol,2009).

Third, Ankara has the country’s highest share of younger people (between 20 and 30) (Ankara

Devel-opmentAgency,2011),mainlybecauseithouses18of

the 179 universities in Turkey. Thus, 8.5% of all universitystudentsinTurkeyareenrolledinuniversities in Ankara (YOK, 2014). Fourth, the variety of recreational activities is relatively low in Ankara, compared to Istanbul and Izmir, which border the AegeanSeaandhaveawarmerclimate.

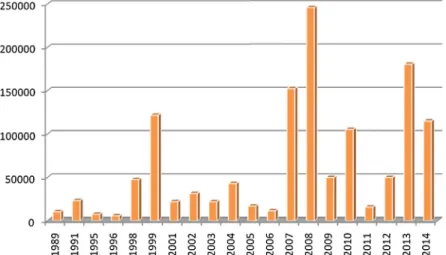

The pace of change in Ankara’s retail supply increased in the 1990s, parallel to the retail changes nationally.Thecity’sfirstshoppingcentre,Atakule,was established in 1989, followed by Karum, Begendik, GalleriaandtheAnkuva/BilkentCenter.By2005,there wereninemallsinAnkara,andthisnumberincreased threetimesinfiveyears,toreach30in2010.Between 2007and2010alone,14newshoppingcentresopened and the total gross leasable area more than doubled (Ozuduru&Varol,2011).Currently,thereare37 shop-ping centres and a total gross leasable area of 1,279,780m2 (see Figs. 7 and 8). The total gross leasableareaofshoppingcentrespercapitainAnkara was the highest in Turkey in 2011 (190m2/1000 people), which led to the construction of even more mallsinthecity.

Despite its growing sprawl, Ankara is a fairly accessible city by public transportation; its vehicle-orientedurbanpolicymeansthemunicipalityconstructs newroadsinsteadofinvestinginpublictransportation. Shopping centresare also often located inthe newly developing and most car-accessible areas of the city, usually onmajorhighways.Forthisreason,themalls attractcustomersfrom almostall ofthe greaterurban area.Thecity’ssouthandsouthwestareashaveahigh

number ofshopping centres, andtheirtradearea also covers almost all districts. Research shows that in Ankara,suburbanresidentsvisitshoppingcentresmore frequently,whereasinner-city residentsvisitshopping streets morefrequently(Ozuduru etal.,2014).

Theexplosioninthenumberofshoppingcentreshas hadasignificantimpactonstreetretailers.Intheearly 2000s,mostretailersinAnkara’sCBDsufferedbecause ofthepopularityofthenewconsumptionspaces.Those stillinbusinessafterthefirstwaveofchangesurvived because they adapted to the market conditions with innovativestrategies.Theirdiversity,brandclustering,

price ranges and selling specific goods and services have helped them remain afloat. The locational advantages ofAnkara’s CBDalsohelp; thereare still asignificantnumberofresidentialunitsinthedistrict, whichincludesamajortransportationhubandacentral area of high pedestrian traffic. The district’s accessi-bility and high level of traffic increases its vitality, includingitseconomicviability.

Ankara’sCBD retailers havealso been assistedby the municipality tosome extent. The city has under-taken small restoration projects and increased the overall aesthetics in selected neighbourhoods. For Fig.7. Totalgrossleasablearea(m2)ofshoppingcentresbyopeningyear(Ankara)(currentfigures).

Source:Authors’survey.

Fig.8. Increaseintotalgrossleasablearea(m2)ofshoppingcentresbyopeningyear(Ankara)(currentfigures). Source:Authors’survey.