Prostatic Diseases and Male Voiding

Dysfunction

Open Prostatectomy Is Still a Valid Option

for Large Prostates: A High-Volume,

Single-Center Experience

Evren Suer, Ilker Gokce, Onder Yaman, Kadri Anafarta, and Orhan Gög

˘üs¸

OBJECTIVES To evaluate, in a retrospective, single-center trial, our open prostatectomy outcomes and complications in the past 12 years to emphasize the feasibility of open prostatectomy for large prostates.

METHODS A total of 1193 patients underwent open prostatectomy from 1995 to 2007. We retrospectively analyzed the data from 664 patients who had preoperative, operative, and postoperative data available.

RESULTS The mean patient age was 67.5 years (range 52– 86). The mean preoperative prostate-specific antigen value was 9.6 ng/mL (range 1.65– 45.6). The mean prostatic weight was 88.7 g (range 45–324) and was significantly different for the 1995–2001 and 2002–2007 groups (73.6 vs 98.2 g, respectively). Of the 664 patients, 208 (31%) had had an indwelling catheter before surgery. The average International Prostate Symptom Score was 21.7 (range 13–32) preoperatively and 10.6 (range 8 –18) postoperatively (P ⬍.005). The average hospitalization was 6.74 days (range 4 –14). Blood transfusion was required in 12.7% of the patients either intraoperatively or postoperatively. Postoperatively, 82 patients (12.3%) had urinary tract infections, 22 (3.2%) had bladder neck obstruction, 5 (0.7%) had urinary incontinence, and 15 (2.3%) had a ureteral meatus stricture.

CONCLUSIONS Open prostatectomy is a feasible treatment option for patients with a large prostate and also for patients with additional bladder pathologic findings such as bladder calculi or diverticula for whom endoscopic treatment modalities are not appropriate. Consequently, open prostatectomy is still the primary option for patients with a prostate greater than 100 cm3and preserves its importance in urology practice, even in the presence of endoscopic innovations. UROLOGY72: 90 –94, 2008. © 2008 Elsevier Inc.

N

umerous improvements, new pharmacologic drugs, and recent surgical treatment options for benign prostatic hyperplasia (BPH) have been developed during the past two decades. At the beginning of the 20th century, open prostatectomy was accepted as the reference standard treatment option for BPH.1 With the emergence of advanced endoscopic techniques and the introduction of new medical management options in the 1990s, the treatment concept for BPH changed.2,3Although open prostatectomy is the oldest treatment for BPH, this method still preserves its place as an alternative option for patients with large pros-tates (greater than 80 cm3).Transurethral resection of the prostate has superseded open prostatectomy as the reference standard treatment option for BPH. Because of the risk of bleeding and possible transurethral resection syndrome after transure-thral resection of the prostate for large prostates, open prostatectomy is considered suitable for these patients. The invasiveness of the procedure and the need for a longer hospitalization time has directed urologists to the less-invasive treatment options. High-power potassium titanyl phosphate (KTP) laser ablation is one of these methods.4,5Although we only have short and

medium-term outcomes, this technique is promising for the future. Holmium laser enucleation of the prostate (HOLEP) is an option.6 – 8Laparoscopic simple prostatectomy, with a

shorter hospital duration and less bleeding, is also an option for the treatment of large prostates.9Open

pros-tatectomy is still one of the major treatment options for patients with a large-volume prostate. As a single center, the aim of our study was to report our long-term experi-From the Department of Urology, University of Ankara School of Medicine; and

Department of Urology, Ufuk University School of Medicine, Ankara, Turkey Reprint requests: Evren Suer, M.D., Department of Urology, University of Ankara School of Medicine, Kelebek Sokak 4/5 GOP Ankara, Turkey. E-mail: evrenos97@ yahoo.com

Submitted: December 12, 2007; accepted (with revisions): March 13, 2008

ence with open prostatectomy in a large patient popula-tion.

MATERIAL AND METHODS

This retrospective study was designed to evaluate the results of 664 patients who had undergone open prostatectomy from 1995 to 2007. During this period, 1193 patients had undergone open prostatectomy, but only 664 of them had had regular follow-up visits and data available for study. The indication for open surgery was determined by the prostate volume and the pres-ence of additional bladder calculi with a diameter of more than 3 cm. The prostate volume threshold for open surgery was dependent on the preference and experience of the surgeons. All patients were evaluated with history, International Prostate Symptom Score (IPSS), physical examination, including digital rectal examination, hemoglobin level, blood urea nitrogen (BUN)/creatinine level, urinalysis, free/total prostate-specific antigen (PSA) ratio, uroflowmetry, and transrectal ultrasonog-raphy. The patient characteristics are listed inTable 1. Trans-rectal ultrasonography-guided prostate biopsy was performed for patients with a total PSA level greater than 4 ng/mL. Patients were also evaluated using the American Society of Anesthesi-ologists (ASA) classification preoperatively. Surgery was per-formed with either a median or Pfannenstiel incision, and a retropubic or suprapubic approach was used, depending on the surgeon’s preference. The catheter was removed 7–9 days after surgery. All patients had their first follow-up visit 1 month after the surgery. The subsequent visits were performed every 6 months for the first 2 years and annually thereafter and included IPSS, hemoglobin measurement, urinalysis, and uroflowmetry. If any infection was detected in the urinalysis, a urine culture was performed and appropriate antibiotic treatment begun. The parameters evaluated in the study included patient age, preop-erative and postoppreop-erative BUN, creatinine, uroflowmetry stud-ies, IPSS, blood transfusion rate, type of operation, preoperative PSA level, additional surgical procedures, complications, ASA status, and hospitalization time. Postoperatively, IPSS and uro-flowmetry were performed at every visit and the lowest mea-surements were taken into account. The data were numeric and normally distributed; therefore, the mean values were compared using a paired-samples t test. P⬍.05 was considered statistically significant.

RESULTS

In our department, 1193 patients underwent open pros-tatectomy from 1995 to 2007. Of these patients, we were

able to include 664 who had data available for this retrospective study. The mean patient age at surgery was 67.5 years (range 52– 86). The mean preoperative PSA value was 9.6 ng/mL (range 1.65– 45.6). The data con-cerning the prostate volume were normally distributed. The average prostate volume of the patients who under-went open prostatectomy from 1995 to 2001 was 73.6 cm3and was 98.2 cm3for those undergoing surgery from

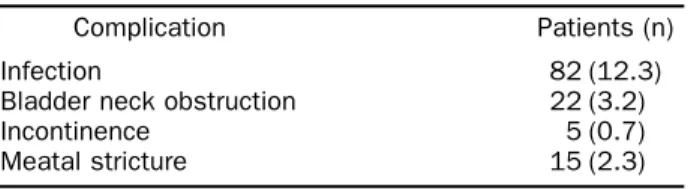

2002 to 2007. This difference was statistically significant (P ⬍.05). We evaluated the patients’ renal function by measuring the serum BUN and creatinine levels. Preop-eratively, the mean BUN was 18.1 mg/dL and the mean creatinine was 1.27 mg/dL. Postoperatively, the corre-sponding values were 17.5 mg/dL and 1.03 mg/dL. The general health status of the patients was evaluated using the ASA classification. The distribution of the patients for ASA 1, ASA 2, ASA 3, ASA 4, and ASA 5 was 13.5%, 58.4%, 26.6%, 1.5%, and 0%, respectively. The lower urinary system function of the patients was evalu-ated with uroflowmetry studies. The measures evaluevalu-ated included the peak flow rate, average flow rate, and postvoid residual volume both preoperatively and post-operatively. The mean values of these parameters are listed inTable 2, and the differences in all the parameters were statistically significant (P ⬍0.0001). Of the 664 patients, 208 (31%) had an indwelling catheter before surgery. The average IPSS of the patients was 21.7 (range 13–32) preoperatively and 10.6 (range 8 –18) postopera-tively (P ⬍.005;Table 2). Suprapubic transvesical pros-tatectomy was performed in 98%, and the retropubic approach was used in 2%. The average hospitalization time was 6.74 days (range 4 –14). A blood transfusion was needed in 12.7% of the patients either intraoperatively or postoperatively. During surgery, additional surgical pro-cedures were performed for concomitant bladder calculi, an inguinal hernia, or bladder diverticula. The postoper-ative complications rates are summarized in Table 3. Bladder neck incision was performed in 18 patients (2.7%), and 14 patients (2.1%) underwent either

meatot-Table 1. Patient characteristics

Parameter Minimum Maximum Mean

Age (y) 52 86 67.5 Total PSA (ng/mL) 1.65 45.6 9.6 Preoperative BUN 10 37 18.1 Preoperative creatinine 0.7 1.8 1.27 Prostate volume* (cm3 ) 1995–2001 45 290 73.6 2002–2007 66 324 98.2 Hospitalization (d) 4 14 6.74 Postoperative BUN 10 37 17.5 Postoperative creatinine 0.6 1.8 1.03

PSA⫽ prostate-specific antigen; BUN ⫽ blood urea nitrogen. * Difference in volume statistically significant.

Table 2. Symptomatic and uroflowmetry measurements Parameter Preoperative Postoperative P Value

Qmax 9.3⫾ 2.3 23.7⫾ 5.8 ⬍.0001 Qavr 4.2⫾ 1.1 13.6⫾ 4.3 ⬍.0001 PVR 116⫾ 27.2 28⫾ 6.1 ⬍.0001 IPSS 21.7⫾ 5.4 10.6⫾ 3.3 ⬍.005

Qmax⫽ peak flow rate; Qavr ⫽ average flow rate; PVR ⫽ postvoid residual urine volume; IPSS⫽ International Prostate Symptom Score.

Table 3. Distribution of complications

Complication Patients (n)

Infection 82 (12.3)

Bladder neck obstruction 22 (3.2) Incontinence 5 (0.7) Meatal stricture 15 (2.3)

omy or meatal dilation. Incidental prostate adenocarci-noma was detected in 2.1% of the patients. Finally, 2 patients died during the first 30 days postoperatively of cardiopulmonary arrest.

COMMENT

The aim of the present study was to report on the clinical data for open prostatectomy from a single center with high patient numbers and experienced surgeons. With the reduction in the number of publications of open prostatectomy and the increased interest in new alterna-tive techniques for large prostates, an impression has arisen that open prostatectomy is a forgotten technique. However, the clinical experience has demonstrated that this is not valid. Even though adequate recent studies are unavailable, some studies have been published that have used open prostatectomy at a considerable rate.10 –12

Bruskewitz et al.13 reported that open prostatectomy

comprises 3% of the prostatectomies performed in the United States. Lukacs14 and Ahlstrand et al.11 reported

that 14% and 12% of prostatectomies in France and Sweden, respectively, were open prostatectomy. Serretta et al.,12 in a study that covered southern Italy,

demon-strated a greater rate of 32%. The open prostatectomy rate was 40% in Israel.15 A greater rate was reported in

Mediterranean countries. In Western countries, large prostates that are not suitable for transurethral proce-dures are the main indication for performing open pros-tatectomy.

The prostate volume is the major indication for open prostatectomy. No cutoff point has been standardized for the prostate volume. However, traditionally, patients with 80 –100-cm3prostates, lower urinary tract symptoms

unresponsive to medical treatment, and the indication for surgical treatment have undergone open prostatec-tomy. In the Italian survey, Tubaro et al.16 reported a

mean prostate volume of 56 cm3. In an early prospective

study,17 the mean prostate volume was 63 cm3. Serretta

et al.,12in a large and provincial study reported a mean

prostate volume of 75 cm3. Recently, Gratzke et al.,18in

a prospective study, reported a mean prostate volume of 96 cm3. The mean prostate volume in the present study

was 88.7 cm3. We stratified our patients into two groups

according to their evaluation and treatment dates (1995– 2001 and 2002–2007). The mean prostate weight was 73.6 g for the first group and 98.2 g for the second. As can be seen, the preference for open prostatectomy has been changing and the threshold prostate volume for endo-scopic procedures has increased in recent years.

Of the 664 patients in our study, 31% were admitted to the clinic with an indwelling urethral catheter. Previous studies from southern Europe reported a frequency of 23%–24%.12,15 The rate reported from North America

has been significantly lower.19This can be explained by

the later diagnosis occurring in countries with a less-developed healthcare infrastructure.

With the threshold for transfusion a hemoglobin value

of 10 g/dL, our transfusion rate was 12.7% postopera-tively. This rate was slightly greater than that in previ-ously published studies.10,12,20 Stratifying the patients

according to a prostate volume less than and greater than 100 cm3, the transfusion rate was 9.4% and 19.2%, re-spectively. The mean length of hospital stay before and after surgery was 3.7 and 8.7 days, respectively. These values are in conformity with those of previous stud-ies.9,17,20Our patients were assessed with urinalysis and

urine culture 1 month after the removal of the urethral catheter. Postoperative urinary infection occurred in 12.3% of the patients. These patients were treated with oral or parenteral antibiotics. Bladder neck stenosis and meatal stenosis occurred in 3.2% and 2.3% of the pa-tients, respectively. Finally, 2 (0.3%) of the 664 patients died early in the postoperative period.

Prostate resection with the holmium:ytrrium-alumi-num-garnet laser was first reported in 1996 on 84 patients with a mean prostate volume of 50 cm3.21 That study

showed that this technique has promise as a safe and effective treatment modality for BPH. HOLEP is one of the most recent innovations for the resection of large prostates. This technique can be used for all prostate sizes, even with simultaneous bladder calculi. The initial and recent studies have revealed this technique to be a safe treatment modality, with superior results compared with open prostatectomy. Gilling et al.6reported on 43

patients with 6 months of follow-up. The mean cathe-terization time was 19.1 hours after surgery, with a mean hospitalization of 28.4 hours. Only 1 patient required recatheterization after surgery. Moody and Lingeman7

compared the outcomes of patients undergoing open prostatectomy and HOLEP. The mean operation time was similar, but the mean hospitalization stay was much longer for those undergoing open prostatectomy than for the HOLEP group (6.1 vs 2.1 days). Kuntz et al.,8in their prospective randomized trial, demonstrated a longer op-erative time and shorter hospital stay and time to cath-eter removal for the HOLEP group. In an ongoing ran-domized trial,22 the outcomes and complications were

evaluated for both open prostatectomy and HOLEP at a 18 months of follow-up. Confirming previous reports, the mean catheterization time (1 vs 6 days, P ⬍.0001) and mean hospitalization time (2 vs 10 days, P⬍.0001) were shorter for the HOLEP group. Both treatment modalities resulted in major improvements in IPSS, urinary flow rate, and postvoid residual urine volume (P⬍.0001). The difference between the HOLEP and open prostatectomy groups was not significant for these parameters. None of the patients in HOLEP group required a blood transfu-sion, although 8 patients did so in the open prostatec-tomy group. Bladder neck stenosis occurred in none of the HOLEP group and in 2 of the open prostatectomy group. Naspro et al.23 reported on their 24-month

fol-low-up data after HOLEP and open prostatectomy in a comparative study of patients with prostates greater than 70 cm3. Predictably, a shorter operation time was

re-ported for the open prostatectomy group (72.09⫾ 21.22 vs 58.31⫾ 11.95 minutes, P ⬍.0001). The mean cath-eterization time (1.5⫾ 1.07 vs 4.1 ⫾ 0.5 days, P ⬍.001) and mean hospital stay (2.7 ⫾ 1.1 vs 5.4 ⫾ 1.05 days, P⬍.001) were shorter for the HOLEP group. The blood loss was less and transfusions were fewer in the HOLEP group (P ⬍.001). The clinical outcomes, urodynamic findings, and late complications were comparable be-tween the two groups.

Although a limited number of studies, without long-term follow-up, have been published on the clinical use of the 80-W KTP laser in large prostates, this technique is a promising modality for these patients. Sandhu et al.4 used the high-power KTP laser for patients with prostates greater than 60 cm3. The mean prostate volume, mean operative time, and mean catheterization time was 101⫾ 40 cm3, 123⫾ 70 minutes, and 23 hours, respectively. The decrease in IPSS and increase in the maximal flow rate was statistically significant at 12 months of follow-up. Rajbabu et al.5in a trial of 54 patients with prostates greater than 100 cm3reported a similar mean catheter-ization time (23 hours) and shorter mean operative time (81 ⫾ 22.9 minutes). Their 24-month follow-up data exhibited excellent outcomes, and only 3 patients (6%) required reoperation. However, the volume of prostatic tissue vaporized with the KTP laser is limited compared with the reduction in tissue with open prostatectomy.

Laparoscopic simple prostatectomy is another alterna-tive treatment for patients with a large prostate. Several studies reporting on different techniques have demon-strated this method as a reasonable modality for large prostates.24 –26 Baumert et al.,9 compared laparoscopic and simple prostatectomy in 60 patients. In the laparos-copy group, the mean IPSS improved from 22.4⫾ 6.9 to 5.7⫾ 3.6 and the mean urinary flow rate improved from 8.1⫾ 2.5 to 24.6 ⫾ 12.1 mL/min (P ⬍.001). The mean operative time was longer for the laparoscopy group (115 vs 54 minutes, P ⬍.01). The mean total blood loss (367⫾ 363 vs 643 ⫾ 647 mL), irrigation time (0.33 ⫾ 0.7 vs 4 ⫾ 3.5 days), and duration of catheterization (4⫾1. 7 vs 6.8 ⫾ 4.7 days) were significantly less in the laparoscopy group than in the open prostatectomy group.

CONCLUSIONS

In this single-center and retrospective study, we evaluated our past 12-year experience for open prostatectomy. The treatment indications are changing for patients with large prostates. Although it depends on the surgeon’s preference, the use of open prostatectomy is limited only to those patients not suitable for endoscopic management. HOLEP is a promising option for patients with a large prostate. Its efficiency has been demonstrated in the treatment of large-volume prostates. Nevertheless, one limitation of this tech-nique is the long learning curve. Another limitation is the high initial cost. The use of the KTP laser is more common than HOLEP or laparoscopy for BPH. However, validation is required for the KTP laser for use with large prostates.

Consequently, open prostatectomy is still a valid option for patients with a prostate greater than 100 cm3, preserving its importance in urology practice, even with the presentation of endoscopic innovations.

References

1. Freyer PJ. One thousand cases of total enucleation of the prostate for radical cure of enlargement of that organ. BMJ. 1912;2:868. 2. Barry MJ, Fowler FJ Jr, Bin L, et al. A nationwide survey of

practicing urologists: current management of benign prostatic hy-perplasia and clinically localized prostate cancer. J Urol. 1997;158: 488-492.

3. McNicholas TA. Management of symptomatic BPH in the UK: who is treated and how? Eur Urol. 1999;36(suppl 3):33-39. 4. Sandhu JS, Ng C, Vanderbrink BA, et al. High-power

potassium-titanyl-phosphate photoselective laser vaporization of prostate for treatment of benign prostatic hyperplasia in men with large pros-tates. Urology. 2004;64:1155-1159.

5. Rajbabu K, Chandrasekara SK, Barber NJ, et al. Photoselective vaporization of the prostate with the potassium-titanyl-phosphate laser in men with prostates of⬎100 mL. BJU Int. 2007;100:593-598. Epub 2007 May 19.

6. Gilling PJ, Kennett KM, Fraundorfer MR. Holmium laser enucle-ation of the prostate for glands larger than 100 g: an endourologic alternative to open prostatectomy. J Endourol. 2000;14:529-531. 7. Moody JA, Lingeman JE. Holmium laser enucleation for prostate

adenoma greater than 100 gm: comparison to open prostatectomy.

J Urol. 2001;165:459-462.

8. Kuntz RM, Fayad A, Lehrich K, et al. Transurethral holmium laser enucleation of the prostate (HOLEP)—a prospective study on 100 patients with one year follow up. Med Laser Appl. 2001;16:15. 9. Baumert H, Ballaro A, Dugardin F, et al. Laparoscopic versus open

simple prostatectomy: a comparative study. J Urol. 2006;175:1691-1694.

10. Meier DE, Tarpley JL, Imediegwu OO, et al. The outcome of suprapubic prostatectomy: a contemporary series in the developing world. Urology. 1995;46:40-44.

11. Ahlstrand C, Carlsson P, Jonsson B. An estimate of the life-time cost of surgical treatment of patients with benign prostatic hyper-plasia in Sweden. Scand J Urol Nephrol. 1996;30:37-43.

12. Serretta V, Morgia G, Fondacaro L, et al. for the Members of the Sicilian-Calabrian Society of Urology. Open prostatectomy for benign prostatic enlargement in southern Europe in the late 1990s: a contemporary series of 1800 interventions. Urology. 2002;60:623-627.

13. Bruskewitz R. Management of symptomatic BPH in the US: who is treated and how? Eur Urol. 1999;36(suppl 3):7-13.

14. Lukacs B. Management of symptomatic BPH in France: who is treated and how? Eur Urol. 1999;36(suppl 3):14-20.

15. Mozes B, Cohen YC, Olmer L, et al. Factors affecting change in quality of life after prostatectomy for benign prostatic hypertrophy: the impact of surgical techniques. J Urol. 1996;155:191-196. 16. Tubaro A, Montanari E. Management of symptomatic BPH in

Italy: who is treated and how? Eur Urol. 1999;36(suppl 3):28-32. 17. Tubaro A, Carter S, Hind A, et al. A prospective study of the safety

and efficacy of suprapubic transvesical prostatectomy in patients with benign prostatic hyperplasia. J Urol. 2001;166:172-176. 18. Gratzke C, Schlenker B, Seitz M, et al. Complications and early

postoperative outcome after open prostatectomy in patients with benign prostatic enlargement: results of a prospective multicenter study. J Urol. 2007;177:1419-1422.

19. Barry MJ, Fowler PJ, Bin L, et al. The natural history of patients with benign prostatic hyperplasia as diagnosed by North American urologists. J Urol. 1997;157:10-15.

20. Varkarakis I, Kyriakakis Z, Delis A, et al. Long-term results of open transvesical prostatectomy from a contemporary series of patients.

21. Gilling PJ, Cass CB, Cresswell MD, et al. The use of the holmium laser in the treatment of benign prostatic hyperplasia. J Endourol. 1996;10:459-461.

22. Kuntz RM, Lehrich K, Ahyai S. Transurethral holmium laser enucleation of the prostate compared with transvesical open pros-tatectomy: 18-month follow-up of a randomized trial. J Endourol. 2004;18:189-191.

23. Naspro R, Suardi N, Salonia A, et al. Holmium laser enucleation of the prostate versus open prostatectomy for prostates⬎70 g:

24-month follow-up. Eur Urol. 2006;50:563-568. Epub 2006 May 2.

24. Nadler RB, Blunt LW Jr, User HM, et al. Preperitoneal laparo-scopic simple prostatectomy. Urology. 2004;63:778-779.

25. Rey D, Ducarme G, Hoepffner JL, et al. Laparoscopic adenectomy: a novel technique for managing benign prostatic hyperplasia. BJU

Int. 2005;95:676-678.

26. Sotelo R, Spaliviero M, Garcia-Segui A, et al. Laparoscopic retro-pubic simple prostatectomy. J Urol. 2005;173:757-760.